Abstract

The high stability of chelated heavy metal complexes like Cu-EDTA renders their effective removal from industrial wastewater a persistent challenge for conventional treatment processes. This study developed a sustainable and high-performance CuO-modified biochar (CuO-BC) from corn straw waste for peroxydisulfate (PDS)-activated degradation of Cu-EDTA. Through systematic optimization, hydrothermal co-precipitation using copper acetate as the precursor followed by secondary pyrolysis at 350 °C was identified as the optimal synthesis strategy, yielding a dandelion-like structure with highly dispersed CuO on the BC surface. It achieved 93.8% decomplexation efficiency and 57.3% TOC removal within 120 min under optimized conditions, with an observed rate constant (Kobs) of 0.0220 min−1—five times higher than BC. Comprehensive characterization revealed that CuO-BC possessed a specific surface area and pore volume of 4.36 and 15.5 times those of BC, along with abundant oxygen-containing functional groups and well-exposed Cu–O active sites. The enhanced performance is attributed to the synergistic effects of hierarchical porosity facilitating mass transfer, uniform dispersion of CuO preventing aggregation, and surface functional groups promoting PDS activation. This work presents a green and scalable approach to transform agricultural waste into an efficient metal oxide-BC composite catalyst, offering dual benefits of environmental remediation and resource valorization.

1. Introduction

The widespread problem of heavy metal pollution, particularly contamination from complex species such as copper-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (Cu-EDTA), poses a severe challenge to environmental remediation worldwide [1]. Cu-EDTA is a typical and highly stable chelate commonly found in industrial wastewaters [2], especially from electroplating and textile processes. The high stability of this complex, which enhances the mobility and bioavailability of heavy metals across a wide pH range, renders conventional treatment technologies, such as chemical precipitation, largely ineffective [3]. Its strong coordination structure makes it resistant to biodegradation and photolysis, leading to persistent environmental presence and potential ecological risks. Therefore, developing advanced technologies—especially novel processes featuring high selectivity, low energy consumption, and environmental friendliness [4]—for the efficient breakage of metal complexes and degradation of organic ligands has become a critical priority in the field of water pollution control.

Peroxydisulfate (PDS)-based advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) have gained increasing attention due to their ability to generate highly reactive sulfate radicals (SO4•−) and reactive oxygen species (ROS), which possess strong oxidation potential and a relatively long lifetime, enabling efficient degradation of recalcitrant pollutants [5]. However, the activation of PDS necessitates the presence of catalysts/activators, with transition metal ions (e.g., Cu2+) being recognized as highly efficient activators [6]. However, homogeneous Cu systems suffer from severe metal leaching and poor reusability, while unsupported CuO nanoparticles tend to aggregate, leading to reduced active surface area and catalytic deactivation. Immobilizing CuO onto carbon supports—particularly biochar (BC) [7,8,9,10]—offers a promising strategy to enhance dispersion, prevent aggregation, and potentially synergize surface functional groups for improved catalytic performance.

Persistent metal leaching remains a critical barrier to the practical application of metal-BC composites. While many studies prioritize achieving high catalytic activity through simple synthesis methods like wet impregnation, these approaches frequently result in poorly dispersed metal species with weak adhesion to the biochar support. Under the oxidative conditions inherent to AOPs, such loosely bound active sites readily leach into the solution. This not only causes rapid catalyst deactivation and a shift toward undesirable homogeneous pathways but also poses risks of secondary contamination. Consequently, the primary challenge extends beyond mere high activity to the development of robust catalysts with firmly anchored active sites. This highlights a crucial research gap: the need for synthetic strategies that fundamentally strengthen the metal-support interface to simultaneously achieve high metal dispersion and minimal leaching.

In this study, a systematic investigation was conducted to evaluate the influence of key synthesis parameters—including CuO loading methods, the pyrolysis temperature of BC, the secondary pyrolysis temperature for CuO deposition, and the CuO loading amount—on the performance and stability. The optimally synthesized CuO-BC catalyst was then comprehensively characterized to unravel the structure-property relationships, with a focus on its surface morphology, elemental distribution, porous structure, crystalline phases, and surface functional groups. By providing fundamental insights into the critical role of synthesis pathways in designing efficient and durable metal oxide-carbon composites, this study provides a fundamental framework for the effective treatment of wastewater containing refractory heavy metal–organic complexes.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Loading Methods

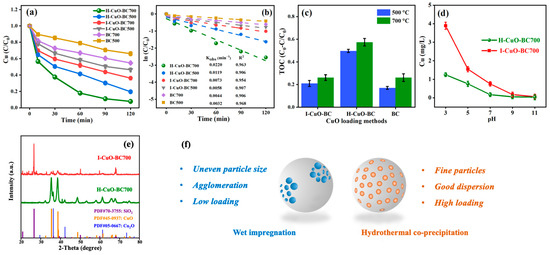

To investigate the influence of different CuO loading methods on the performance of CuO-BC in activating PMS for oxidative degradation of Cu-EDTA, straw-derived BC was first prepared at two commonly used pyrolysis temperatures: 500 °C and 700 °C. Subsequently, CuO was loaded onto the BC via two distinct approaches: traditional wet impregnation and hydrothermal co-precipitation. Materials were denoted as I-CuO-BC500, I-CuO-BC700, H-CuO-BC500, and H-CuO-BC700, respectively. Each synthesized CuO-BC sample was then applied in the PDS activation system for Cu-EDTA degradation. The decomplexation of Cu-EDTA was evaluated based on variations in Cu(II) concentration in solution, while total organic carbon (TOC) removal was used to assess the mineralization efficiency of the organic ligands.

The results are shown in Figure 1; the BCs prepared at both 500 °C and 700 °C were capable of activating PDS and exhibited a certain degree of degradation efficiency toward Cu-EDTA. Notably, BC pyrolyzed at 700 °C (BC700) demonstrated superior performance, achieving a decomplexation efficiency of 45.2% and a TOC removal efficiency of 25.9%. These findings indicated that the pyrolysis temperature of BC significantly influenced the degradation efficiency of the CuO-BC/PDS system for Cu-EDTA. Furthermore, the CuO-BC exhibited enhanced performance in activating PDS for Cu-EDTA removal. Among them, the H-CuO-BC500 and H-CuO-BC700 showed higher decomplexation efficiencies of 80.4% and 93.8%, respectively, along with TOC removal efficiencies of 49.6% and 57.3%. The pseudo-first-order kinetic fitting results for the decomplexation of Cu-EDTA in the CuO-BC/PDS system are presented in Figure 1b. The H-CuO-BC exhibited significantly higher observed rate constants (Kobs), further confirming their enhanced efficiency in Cu-EDTA decomplexation.

Figure 1.

Performance of CuO-BC prepared via different CuO loading methods: (a) variation in Cu(II) concentration, (b) first-order kinetic of Cu(II) removal, (c) TOC removal efficiency, and (d) Cu(II) leaching from CuO-BC under different pH conditions, (e) X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of CuO-BC prepared via different CuO loading methods, (f) schematic diagram of CuO-BC prepared by traditional wet impregnation and hydrothermal co-precipitation process. Reaction conditions: [Cu-EDTA] = 0.2 mmol/L, [PDS] = 8 mmol/L, [CuO-BC] = 0.5 g/L.

To evaluate the stability of I-CuO-BC700 and H-CuO-BC700 under different aqueous pH conditions, leaching experiments were conducted, and the results are shown in Figure 1d. Both materials exhibit good stability over the pH range of 7–11, with Cu(II) leaching concentrations not exceeding 1.00 mg/L. However, under acidic conditions (pH < 7), the Cu(II) leaching from I-CuO-BC700 increased significantly, reaching 3.89 mg/L at pH 3. In contrast, H-CuO-BC700, prepared via the hydrothermal co-precipitation method, demonstrated superior stability, with Cu leaching only 0.32 times that of I-CuO-BC700 under the same acidic conditions. The enhanced stability of H-CuO-BC700 can be attributed to the following factors: (1) During hydrothermal co-precipitation, part of the Cu species was embedded within the carbon matrix, forming more stable structural integrations that are less prone to leaching [11]; (2) The use of urea as a precipitating agent promoted uniform nucleation and deposition of CuO nanoparticles on the BC surface, resulting in stronger interfacial interaction and reduced metal leaching [12]. It is noteworthy that, under acidic or strongly complexing conditions, EDTA possesses a high affinity for Cu2+ and can dissolve loosely bound or surface-exposed Cu species by forming stable [Cu(EDTA)]2− complexes. Such ligand-induced dissolution mainly affects Cu particles that are weakly attached or aggregated on the biochar surface. Therefore, for I-CuO-BC700, partial Cu dissolution by EDTA is possible. In contrast, for H-CuO-BC700, where Cu species are uniformly nucleated and partially embedded into the carbon matrix forming strong Cu-O-C interfacial bonds, the chelation-induced Cu loss is largely suppressed. This structural integration ensures excellent stability of the catalyst even in acidic Cu-EDTA wastewater environments. Given that wastewater containing heavy metal–organic complexes (e.g., Cu-EDTA) is typically acidic (pH < 7), H-CuO-BC700 exhibits a distinct advantage for practical applications in such environments.

In addition, the performance and stability of CuO-BC are closely related to the dispersion, crystallinity, loading amount, and particle size of CuO on the BC support. Compared with I-CuO-BC700, H-CuO-BC700 exhibited stronger diffraction peaks corresponding to CuO and Cu2O, indicating high phase purity of the loaded Cu. This is attributed to the hydrothermal co-precipitation method enabling more uniform and dense deposition of Cu species on the BC surface, which enhances crystallinity and XRD detectability. Whereas the Cu species peaks in I-CuO-BC700 are weaker, and the SiO2 present in the BC support itself shows relatively strong diffraction peaks in the XRD pattern. The higher dispersion and lower loading density of Cu in the impregnated sample result in less shielding of the underlying SiO2, allowing its signal to be clearly observed. The hydrothermal co-precipitation method modulated the chemical states of Cu species, enabling efficient Cu(II)/Cu(I) redox cycling [13], which promoted effective PDS activation and enhanced catalytic oxidation performance. Previous studies have shown that CuO particles prepared via wet impregnation tend to aggregate outside the pores of BC, partially blocking pore channels and resulting in non-uniform distribution, which can impair catalytic performance. The hydrothermal co-precipitation method promoted the formation of small-sized or even amorphous CuO nanoparticles within the porous structure of BC [11]. In summary, the CuO-BC prepared from BC700 using copper acetate as the Cu source via hydrothermal co-precipitation possesses higher dispersion, better crystallinity, higher purity, optimal loading amount, and smaller particle size on the BC surface (Figure 1f), which are essential for achieving superior treatment performance and stability. Therefore, in subsequent experiments, the hydrothermal co-precipitation method was adopted for BC modification and CuO loading. The resulting composite was uniformly denoted as CuO-BC for simplicity.

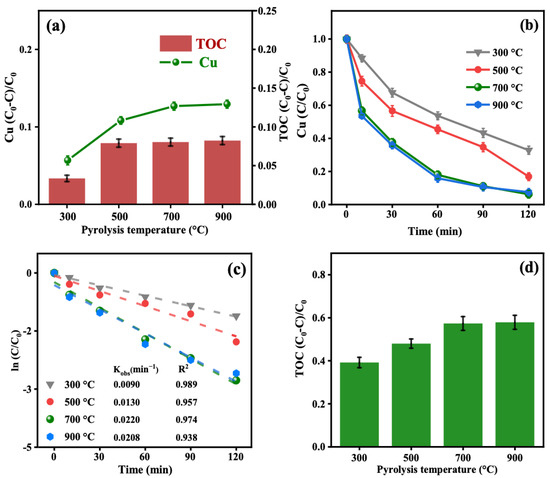

2.2. Pyrolysis Temperature of BC

The BC pyrolysis temperature can significantly influence its structural characteristics, the quantity and type of surface functional groups, thereby affecting its adsorption and properties [7,14]. To investigate the impact of the BC pyrolysis temperature on the performance of the CuO-BC/PDS system in decomplexation of Cu-EDTA, BCs were prepared at 300 °C, 500 °C, 700 °C, and 900 °C. Subsequently, CuO was loaded onto each BC sample via the hydrothermal co-precipitation method to obtain materials, which were denoted as CuO-BC300, CuO-BC500, CuO-BC700, and CuO-BC900, respectively.

To evaluate the adsorption performance of the materials, the removal of Cu-EDTA through adsorption was investigated and compared. As shown in Figure 2a, CuO-BC700 exhibited the highest adsorption capacity for Cu-EDTA, while CuO-BC300 showed the lowest. The adsorption capacities of CuO-BC500, CuO-BC900, and CuO-BC700 were relatively similar. However, overall, the adsorption of Cu-EDTA by CuO-BC was negligible. This limited adsorption efficiency may be attributed to the stable speciation of Cu-EDTA, which makes it resistant to removal via adsorption.

Figure 2.

Performance of CuO-BC prepared at different BC pyrolysis temperatures: (a) adsorption capacity of CuO-BC for Cu-EDTA; (b) variation in Cu(II) concentration; (c) first-order kinetics of Cu(II) removal; (d) TOC removal efficiency. Reaction conditions: [Cu-EDTA] = 0.2 mmol/L, [PDS] = 8 mmol/L, [CuO-BC] = 0.5 g/L.

As shown in Figure 2b–d, the CuO-BC/PMS system exhibited effective degradation performance for Cu-EDTA. CuO-BC300, CuO-BC500, CuO-BC700, and CuO-BC900 all exhibited excellent activation performance. This suggested that CuO-BC contains abundant active sites capable of activating PDS to generate reactive species that efficiently degrade Cu-EDTA. Among them, CuO-BC700 has remarkable performance, achieving a decomplexation efficiency of 93.8% and a TOC removal of 57.3%, and with highest Kobs. Gao et al. [7] reported that increasing the pyrolysis temperature within a certain range can regulate and enhance the C-C bonds and sp2 graphitic structure, which is beneficial for reducing oxygen-containing functional groups and increasing the degree of graphitization. Simultaneously, it helps generate more defect structures, thereby enabling more stable loading of subsequent CuO [15].

However, when the pyrolysis temperature was further increased to 900 °C, no significant improvement in Cu(II) removal efficiency, TOC removal, or the Kobs was observed for the CuO-BC900/PDS system. This could be attributed to excessive graphitization at such a high temperature [16,17], which may lead to a significant reduction in surface functional groups and defect sites that are crucial for anchoring CuO nanoparticles. Additionally, the overly developed pore structure might alter the diffusion behavior of reactants or promote non-productive consumption of PDS, ultimately limiting further enhancement in treatment performance. Consequently, this might result in poorer dispersion and weaker interaction between CuO and the BC support, potentially increasing metal leaching and reducing the number of accessible active sites. In the subsequent experiments, CuO-BC700 was uniformly abbreviated as CuO-BC.

2.3. Secondary Pyrolysis Loading CuO Temperature

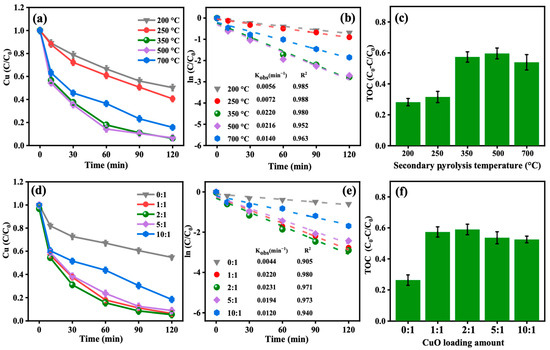

The secondary pyrolysis temperature significantly influences the performance of CuO-BC. Samples were prepared at various secondary pyrolysis temperatures (200, 250, 350, 500, and 700 °C) and tested for their ability to degrade 0.2 mmol/L Cu-EDTA in the presence of PDS. The results are presented in Figure 3a–c.

Figure 3.

Effect of (a–c) secondary pyrolysis temperature and (d–f) CuO loading amount on Cu-EDTA decomplexation and TOC removal.

At relatively low temperatures (200 °C and 250 °C), the CuO-BC samples exhibited limited treatment efficiency, removing only 49.7% and 59.4% of Cu(II) and 28.1% and 31.5% of TOC, respectively, with Kobs of 0.0056 and 0.0072 min−1. This is attributed to insufficient thermal conditions for optimal CuO formation on the surface of BC, which adversely affects both the quantity and crystallinity of CuO, thereby diminishing the catalytic performance [18]. In contrast, under moderate secondary pyrolysis temperatures (350 °C and 500 °C), the removal efficiencies of Cu(II) and TOC stabilized at approximately 93.0% and 57.0%, respectively, with Kobs values of 0.0220 and 0.0216 min−1, indicating these conditions as being near-optimal for catalytic activity. It is speculated that an increase in secondary pyrolysis temperature enhances the opportunity for CuO to be effectively loaded onto the BC surface [11]. However, when the secondary pyrolysis temperature was further increased to 700 °C, a decline in removal efficiencies of Cu(II) and TOC to 84.3% and 53.9%, respectively, was observed, along with a decrease in Kobs. This reduction in treatment performance is likely due to sintering of CuO particles on the BC surface at excessively high temperatures, leading to structural damage and thus compromising the material’s catalytic properties.

In summary, the performance of CuO-BC is strongly influenced by the secondary pyrolysis temperature used during CuO loading. Within an appropriate range, increasing the pyrolysis temperature enhances activity, which can be attributed to improved heat and mass transfer within the material, promoting the formation of CuO with higher crystallinity and increasing its effective loading on the BC surface. However, excessively high pyrolysis temperatures did not further enhance performance and may even impair catalytic efficiency. This decline is likely due to thermal sintering of CuO crystallites, which can disrupt the material’s structure and reduce active site availability. As reported by Alsharif et al. [19], CuO-BC exhibits high thermal stability, maintaining structural integrity up to 660 °C, with optimal stability observed around 315 °C. Taking into account both catalytic performance and energy consumption associated with high-temperature pyrolysis, a secondary pyrolysis temperature of 350 °C was selected as the optimal condition for CuO loading and was adopted in all subsequent experiments.

2.4. CuO Loading Amount

Another critical factor influencing the performance of CuO-BC is the loading amount of CuO. To optimize the CuO content, a series of composites were prepared with varying mass ratios of CuO to BC (m:m = 0:1, 1:1, 2:1, 5:1, and 10:1). The performance was evaluated based on the degradation efficiency of Cu-EDTA in the CuO-BC/PDS oxidation system. This systematic investigation aims to identify the optimal CuO loading that maximizes catalytic activity while maintaining material stability and cost-effectiveness.

As shown in Figure 3, the degradation performance of Cu-EDTA by CuO-BC/PDS varies significantly with the CuO loading ratio. BC without CuO loading exhibits moderate activity, achieving 45.2% Cu(II) removal, 25.9% TOC removal, and a Kobs of 0.0044 min−1, indicating that BC can activate PDS to some extent. When the CuO/BC mass ratio is increased to 1:1, treatment performance improved dramatically: Cu(II) and TOC removal reach 2.07 and 2.21 times higher than those of the BC/PDS system, respectively, with Kobs increasing fivefold to 0.0220 min−1. This enhancement is primarily attributed to CuO acting as a critical active site on the BC surface, facilitating more efficient PDS activation and generating a higher concentration of ROS, thereby promoting the oxidative degradation of Cu-EDTA.

Further increasing the loading ratio to 2:1 results in only marginal improvement, after 120 min of reaction, Cu(II) and TOC removal increased slightly from 93.8% and 57.3% to 94.6% and 58.9%, respectively, with no significant increase in Kobs (Figure 3e). However, when the ratio is raised to 5:1 and 10:1, both removal efficiencies and Kobs begin to decline (Figure 3f). This deterioration is likely due to excessive CuO loading causing nanoparticle aggregation on the BC surface, which disrupts the porous structure of the support and impedes mass transfer of PDS and Cu-EDTA to active sites. Additionally, high loading may reduce the dispersion and crystallinity of CuO particles, negatively affecting catalytic activity. Previous studies have suggested that surface electron transfer plays a crucial role in the CuO-BC/PDS system, and both insufficient and excessive CuO loading can hinder electron conduction pathways [20,21]. Overall, the use of a 1:1 mass ratio of CuO to BC for activating PDS to degrade Cu-EDTA offered an optimal balance between economy and performance. As summarized in Table S1, the CuO-BC/PDS exhibits superior EDTA-Cu degradation performance compared to previously reported systems [4,22,23,24,25,26].

2.5. Characterization Analysis of CuO-BC After Optimization

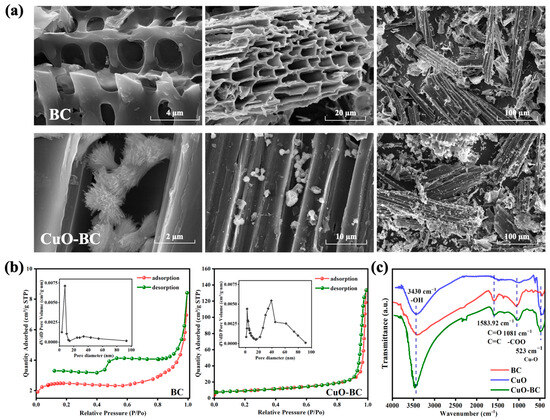

2.5.1. Surface Morphology and Elemental Distribution

SEM was employed to examine the surface morphology, as shown in Figure 4. After pyrolysis, BC exhibits a well-developed porous structure with a smooth surface primarily composed of carbon and minimal impurities. This porous architecture typically possesses excellent electrochemical properties, providing abundant active sites conducive to molecular interactions and electron transfer, thereby enhancing catalytic performance [27]. Moreover, the cross-sectional view of BC reveals a relatively intact tubular layered structure without any noticeable structural collapse, which is favorable for subsequent CuO modification and loading. The surface of CuO-BC loses its original smoothness and displays distinct small particle-like features, indicating the uniform deposition of CuO on the BC surface. These modified surfaces are essential components for activating the oxidant PDS. At higher magnifications, CuO appears as dandelion-like clusters of needle-like structures on the BC surface; most of the CuO is loaded within the layers of BC without causing significant pore blockage. These observations confirm the successful loading of CuO onto BC, and the presence of BC effectively prevents substantial CuO aggregation, thus enhancing the catalytic activity [15].

Figure 4.

Characterization of BC and CuO-BC: (a) SEM morphology, and (b) N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms, (c) FTIR spectra of BC, CuO, and CuO-BC.

The elemental composition of BC before and after CuO loading was analyzed using SEM-EDS. The BC is predominantly composed of C, with a content of 88.36 wt%, along with a minor amount of O (8.58 wt%) (Figure S1). In contrast, in CuO-BC, the C content decreases significantly to 56.95 wt%, while the contents of O and Cu increase markedly. This reduction in the relative carbon content was attributed to the successful deposition of CuO on the BC surface. The observed changes in elemental composition further confirm the successful synthesis of the CuO-BC composite.

2.5.2. Porous Structure and Textural Properties

The pore structure of BC before and after CuO loading was investigated through N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms and pore size distribution analysis, with results shown in Figure 4b and Table 1. The pristine BC exhibits a relatively low specific surface area of 7.552 m2/g and a small pore volume of only 0.013 cm3/g, indicating limited available pore space for catalytic processes. Notably, the average pore diameter of BC is 6 nm, classifying it as a mesoporous material. Such mesoporosity facilitates the mass transfer and interaction between the oxidant PDS and the pollutant Cu-EDTA, thereby contributing to the observed catalytic activity of pristine BC in PDS activation and partial degradation of Cu-EDTA.

Table 1.

The structural characteristics of BC and CuO-BC.

In contrast, the CuO-BC composite showed significantly enhanced textural properties, with a specific surface area and pore volume 4.36 and 15.5 times higher than those of BC, respectively. The marked increase in porosity is likely due to combined effects of ash reduction [28] during hydrothermal treatment and pore generation from gas release during copper precursor decomposition. This increase provided more accessible adsorption sites for both Cu-EDTA and PDS, promoting their concentration and interaction on the catalyst surface, ultimately leading to improved degradation efficiency. Previous studies have indicated that micropores are beneficial for the dense distribution of active sites, mesopores facilitate electron transfer and mass transport, while macropores serve as transport channels that expose internal micropores and mesopores to the bulk solution [29]. Pore size distribution analysis revealed that pristine BC is primarily composed of micropores and mesopores, which support efficient PDS activation. After CuO modification, CuO-BC exhibits a well-developed hierarchical pore structure, integrating micropores, mesopores, and macropores. This multi-scale porosity synergistically enhances mass diffusion, active site accessibility, and electron transfer, thereby accelerating the removal of Cu-EDTA.

2.5.3. Surface Functional Groups

FTIR was employed to further evaluate the structural features and surface functional groups of BC and CuO-BC, as shown in Figure 4c. The prominent peak at 3430 cm−1 is attributed to the O-H stretching vibration. After CuO loading, the intensity of this band significantly increased, indicating a higher concentration of hydroxyl groups (-OH) on the CuO-BC surface, possibly due to surface hydroxylation of CuO or enhanced hydrogen bonding. Peaks at 1583 cm−1 and 1081 cm−1 are assigned to C=C, C=O, and -COO- functional groups, which are characteristic of oxygen-containing groups in BC [30]. These bands are clearly observed in both BC and CuO-BC, suggesting that the primary functional framework of BC is preserved after CuO modification. Additionally, three weak peaks near 874, 814, and 760 cm−1 are associated with bending vibrations of aromatic C-H bonds. In CuO-BC, these peaks exhibit reduced intensity and slight shifts compared to pristine BC, implying that CuO loading may perturb the electronic environment of aromatic structures or partially cover aromatic domains, thereby altering their vibrational behavior. Notably, a distinct and intense peak appears at 523 cm−1 in both CuO and CuO-BC, which is absent in pristine BC. This band is assigned to the Cu-O stretching vibration. The intensity follows the order: CuO > CuO-BC, where the slightly lower intensity in CuO-BC is likely due to signal dilution by the carbon matrix. This observation provides direct spectroscopic evidence for the successful incorporation of CuO onto the BC surface, enriching the surface functional group architecture and enhancing the material’s potential for interaction with PDS and Cu-EDTA [31].

The Boehm titration method was utilized to quantitatively analyze the surface functional groups of the modified material CuO-BC, with detailed results presented in Table 2. After simple washing, pristine BC primarily contains carboxyl, lactone, phenolic hydroxyl, and carbonyl groups. Upon loading CuO, significant changes in the functional groups of the modified material CuO-BC were observed, notably a marked decrease in carboxyl content. This reduction is likely due to partial conversion of carboxyl groups into lactone groups, possibly resulting from the alkaline environment created during the introduction of copper precursors. Moreover, there is an increase in the content of lactones, carbonyls, and phenolic hydroxyls to varying degrees, which may play critical catalytic roles in PDS activation and the oxidative degradation of Cu-EDTA [32]. The introduction of CuO could induce reactions with surface groups on BC, generating highly reactive intermediates such as semiquinone radicals [33], thereby enhancing the total content of oxygen-containing functional groups. Our findings also confirmed that the total content of oxygen-containing functional groups on the surface of CuO-BC is higher compared to BC. In summary, through both qualitative and quantitative analysis of the functional group structures before and after CuO loading on BC, it can be concluded that the excellent performance of CuO-BC is not solely attributed to the presence of Cu–O bonds but also closely related to the abundance of oxygen-containing functional groups on its surface. These functional groups serve as critical active sites during the catalytic process, further promoting electron transfer and enhancing reaction kinetics, thus contributing significantly to the overall efficiency and stability of the catalyst in AOPs.

Table 2.

Surface oxygen-containing functional groups of BC and CuO-BC.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals and Solutions

Copper sulfate pentahydrate (CuSO4·5H2O), ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid tetrasodium salt dihydrate (EDTA, C10H14N2O8Na2·2H2O), copper acetate hydrate (Cu (CH3COO)2·H2O), urea (CH4N2O), copper nitrate trihydrate (Cu(NO3)2·3H2O), sodium persulfate (Na2S2O8), sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3), Sodium carbonate (Na2CO3), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), sodium ethylate (C2H5ONa), hydrochloric acid (HCl), and phenolphthalein (C20H14O4) were obtained from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China).

A 0.05 mol/L Cu2+ stock solution was prepared by dissolving 1.2485 g of CuSO4·5H2O in 100 mL of deionized water. Similarly, a 0.05 mol/L EDTA stock solution was obtained by dissolving 1.8612 g of C10H14N2O8Na2·2H2O in 100 mL of deionized water. An equimolar mixture of the Cu2+ and EDTA stock solutions was then combined to prepare the Cu-EDTA complex solution, followed by continuous stirring for 12 h. The complete complexation was confirmed by ultraviolet-visible (UV–vis) spectroscopy.

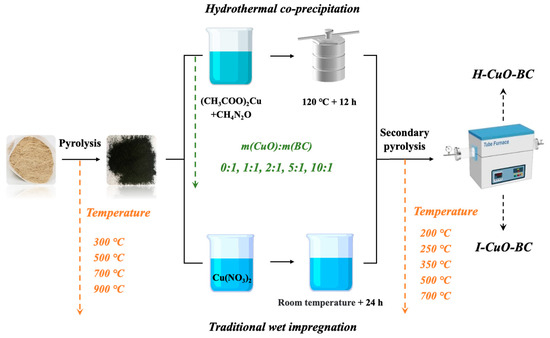

3.2. Catalyst Preparation

The modification of BC was carried out in two steps: first, the preparation of straw-derived BC, followed by Cu loading and a secondary pyrolysis to obtain CuO-BC. Corn straw was ground to pass through a 60-mesh sieve and thoroughly washed with deionized water to remove impurities. After drying, the cleaned straw powder was placed in a quartz boat and subjected to pyrolysis in a tube furnace under a nitrogen atmosphere. The pyrolysis conditions were as follows: the furnace was heated from 20 °C to target temperatures of 300, 500, 700, and 900 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C/min, and each temperature was maintained for 2 h. After pyrolysis, the samples were naturally cooled to room temperature, ground, and sieved to below 100 mesh. The resulting BCs were labeled as BC300, BC500, BC700, and BC900, respectively (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

CuO loading strategies on straw-based BC.

Two copper-loading methods were employed to deposit Cu species onto the as-prepared biochar: wet impregnation and hydrothermal co-precipitation. Following loading, all samples were subjected to a secondary pyrolysis at 350 °C to obtain the final CuO-BC. The samples prepared via hydrothermal co-precipitation and wet impregnation were denoted as H-CuO-BC and I-CuO-BC, respectively. The detailed procedures for each method are as follows: (1) Hydrothermal co-precipitation: Dissolve a certain amount of copper acetate monohydrate Cu(CH3COO)2·H2O (containing 0, 1, 2, 5, 10 g of CuO, respectively) and 1.25 g of urea in an appropriate volume of deionized water to ensure complete dissolution of the reagents. Subsequently, 1 g of pre-prepared BC was added to the solution, followed by thorough mixing. The suspension was transferred into a Teflon-lined autoclave and sealed, after which hydrothermal treatment was carried out at 120 °C for 12 h. Upon completion of the reaction, the system was naturally cooled to room temperature. The solid product was collected and washed repeatedly (>3 times) with absolute ethanol and deionized water to remove residual organics, inorganics, and intermediate byproducts. The washed sample was then dried in an oven. Finally, the dried material was calcined in a nitrogen atmosphere at 350 °C for 2 h with a heating rate of 5 °C/min, and subsequently allowed to cool naturally to room temperature, yielding the H-CuO-BC. (2) Wet impregnation: To achieve a mass ratio of 1:5 between BC and CuO, an appropriate amount of Cu(NO3)2·3H2O was calculated and dissolved in deionized water to prepare the loading solution. The pre-prepared BC was then added to the Cu(NO3)2 solution and let it stand for 24 h to ensure sufficient adsorption of the copper salt onto the BC surface. Afterward, the loaded sample was dried in an oven. Subsequently, the dried material was placed in a tube furnace under a nitrogen atmosphere and calcined at 350 °C for 2 h with a heating rate of 5 °C/min. The sample was then naturally cooled to room temperature, yielding the final I-CuO-BC.

In addition to optimizing key preparation parameters, including the CuO loading method, the pyrolysis temperature of the BC, the secondary pyrolysis temperature for CuO deposition, and the CuO loading amount (Table 3), the treatment performance of the resulting CuO-BC materials was evaluated based on their degradation efficiency toward Cu-EDTA in a PDS activation system. The optimal CuO-BC catalyst was thus identified. Notably, in selecting the most suitable CuO loading approach, the stability of the materials was further assessed by measuring metal leaching, in addition to catalytic activity. The CuO loading level was optimized based on the mass-to-mass ratio (m:m) of CuO to BC.

Table 3.

Experimental design.

3.3. Experimental Design

In a typical degradation experiment, 100 mL of Cu-EDTA solution (0.2 mmol/L) was placed into a 250 mL conical flask at room temperature. A predetermined amount of CuO-BC and 1.0 mol/L Na2S2O8 solution were then added to the flask. The mixture was subsequently subjected to magnetic stirring or shaken at 200 rpm in a thermostatic shaker. At preset time intervals, aliquots of the reaction mixture were withdrawn, filtered through a 0.45 μm polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) membrane to remove solid particles, and analyzed for Cu(II) concentration and TOC. The pH of the filtrate obtained after membrane filtration was adjusted to 11 using 0.1 mol/L NaOH solution [34]. After precipitation for 2 h [35], the solution was filtered to effectively remove the Cu(II) released from the decomplexation of Cu-EDTA. The filtrate was then acidified to pH 1–2 with 5% HNO3 solution, and the residual Cu(II) concentration was measured. Based on this, the Cu(II) removal efficiency was calculated, which represents the decomplexation efficiency of Cu-EDTA in the reaction system.

3.4. Analytical Method

The Cu(II)-EDTA solution was spectrally measured using a UV–vis spectrophotometer (CARY60, Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA), with a scanning wavelength range of 200 to 800 nm and a scanning speed of 100 nm/min. The concentration of Cu(II) in the solution was quantified by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES, Optima 8000, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). The changes in TOC concentration before and after the reaction were determined by a TOC analyzer (Jena 3100, Analytik Jena AG, Jena, Germany) to evaluate the mineralization efficiency of organic ligands. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Apreo 2C, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was employed to observe and analyze the surface morphology of BC and CuO-BC samples, which were mounted on conductive carbon tape without sputter coating. The specific surface area and pore structure characteristics (pore size distribution and pore volume) of BC and CuO-BC were measured using an automatic physical adsorption instrument (ASAP 2460, Micromeritics, Norcross, GA, USA) with N2 as the adsorbate gas. BC, as well as CuO-BC before and after the reaction, were, respectively, mixed with KBr and ground into finer powder samples (<200 mesh), and subsequently pressed into pellets. Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy (Tensor 27, Bruker, Ettlingen, Germany) was then conducted to characterize the material structure, surface properties, purity, and functional groups in the range of 400–4000 cm−1. X-ray diffraction (XRD, Rigaku Ultima IV, Rigaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) measurements were conducted using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å) in wide-angle mode.

The types and quantities of oxygen-containing functional groups on the material surface were determined using the Boehm titration method [36]. Specifically, NaHCO3 primarily reacts with carboxylic groups; Na2CO3 neutralizes both carboxylic and lactonic groups; NaOH reacts with carboxylic, lactonic, and phenolic groups; while C2H5ONa can additionally interact with carbonyl groups, in addition to the aforementioned three functional groups. The content of each functional group was calculated based on the differences in consumption of the various alkali solutions, using the following equation:

While A represents the consumption of alkali (mmol/g), and V represents the volume of NaOH solution consumed in titrating the excess HCl solution (mL). CNaOH indicates the concentration of the NaOH solution (0.05 mol/L). V0 represents the volume of the alkaline solution used, which is 25 mL. C0 indicates the concentration of the alkaline solution used (0.05 mol/L). VHCl represents the volume of hydrochloric acid used (25 mL). CHCl represents the concentration of the hydrochloric acid solution used (0.05 mol/L). M represents the sample weight of BC and CuO-BC (0.05 g).

4. Conclusions

This study presents a sustainable strategy for valorizing corn straw waste into a high-performance CuO-modified BC for the PDS-based oxidative degradation of Cu-EDTA. Through systematic optimization, hydrothermal co-precipitation emerged as the superior CuO loading method over conventional impregnation, with optimal synthesis parameters identified as: pyrolysis of raw biomass at 700 °C, followed by CuO deposition via copper acetate (1:1 mass and mass ratio to BC) and secondary calcination at 350 °C. The resulting CuO-BC achieved 93.8% decomplexation and 57.3% TOC removal within 120 min under optimized reaction conditions (0.5 g/L catalyst, 8 mmol/L PDS), with a reaction rate constant (Kobs) of 0.0220 min−1—5 times higher than that of pristine BC. Comprehensive characterization revealed that CuO was uniformly loaded on the BC surface in a dandelion-like structure, with BC effectively preventing nanoparticle aggregation. The composite exhibited enhanced specific surface area and pore volume (4.36 and 15.5 times that of BC, respectively), along with abundant oxygen-containing functional groups and well-dispersed Cu–O active sites. These structural and chemical features synergistically contribute to the superior treatment performance in PDS activation and Cu-EDTA demetallation. This work demonstrates a promising pathway for converting agricultural waste into an efficient metal oxide-carbon composite catalyst, offering both environmental remediation potential and resource recovery implications.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/catal15111027/s1: Figure S1: SEM-EDX analysis of BC and CuO-BC; Table S1: Comparison of Cu(II)-EDTA complex degradation performance between the present study and previously reported catalytic systems.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, visualization, funding acquisition, W.A.; conceptualization, methodology, data curation, Y.Z.; validation, visualization, J.H.; conceptualization, methodology, W.S.; formal analysis, investigation, Q.L.; resources, writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition, H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 52470049 and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation, grant number 2025M771200.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, M.; Cheng, N.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Li, G.; Liang, H. Mechanism and Efficiency of Cu-EDTA Wastewater Treatment and Cu Recovery by Cation Exchange Membrane Electrolysis Reactor. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 116775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, R.; Hu, K.; Kan, H.; Yan, L.; Chen, R.; Zhao, X. Self-Catalytic Enhancement of Cu-EDTA Decomplexation and Simultaneous Cu Recovery Via a Dual-Cathode Electrochemical Process. Water Res. 2025, 268, 122775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Gao, G.; Pan, B.; Zhang, W.; Lv, L. A New Combined Process for Efficient Removal of Cu(II) Organic Complexes from Wastewater: Fe(III) Displacement/UV Degradation/Alkaline Precipitation. Water Res. 2015, 87, 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Chen, Z.; Yao, J.; Wu, J.; Gao, N.; Zhang, Z. Visible Light for Enhancing the Reusability of MOF-Derived Fe2O3@MoS2 Heterojunction in the Rapid Degradation of Cu-EDTA by Activated Peroxymonosulfate: Performance and Mechanism. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 494, 138669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.H.; Wang, W.L.; Li, B.; Liu, C. MoS2-Assisted in Situ Anodic Peroxydisulfate Activation for Low-cost and Sustainable Water Purification. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 379, 134937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yuan, D.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, T.; Tang, S.; Wang, D. Promoting Cu2+/Cu+ Redox Cycling Via Molybdenum Carbide toward Peroxydisulfate-Based Advanced Oxidation Process. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2025, 318, 122210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Weng, N.; Huo, S. Inactivation of Harmful Cyanobacteria Microcystis Aeruginosa by Cu2+ Doped Corn Stalk Biochar Treated with Different Pyrolysis Temperatures. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 394, 130259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Yan, L.; Qi, H.; Song, W.; Li, Y.; Li, X. Enhanced Activation of Peroxymonosulfate by CuO Modified Biochar through Mechanochemical Synthesis: Insights into the Roles of Active Sites and Electron Density Redistribution. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 115180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Li, J.; Fei, C.; Fan, Z.; Wang, B. Removal of Sulfadiazine from Water by a Three-Dimensional Electrochemical System Coupled with Persulfate: Enhancement Effect of Ball-Milled CuO-Fe3O4@Biochar. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 190, 631–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essa, R.A.; Amin, S.; Sedky, A.; Zeid, E.F.A.; Abd El-Aal, M. Efficient Water Purification: CuO-Enhanced Biochar from Banana Peels for Removing Congo Red Dye. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 58889–58904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Lin, Q.; Zhang, X.; Huang, Z.; Fu, H.; Xiao, R.; Liu, S.-S. Determining the Key Factors of Nonradical Pathway in Activation of Persulfate by Metal-Biochar Nanocomposites for Bisphenol A Degradation. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 391, 123555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, A.; Cho, S.; Cho, W.J.; Lee, K.H. Morphology-Controlled Synthesis of CuO Nano- and Microparticles using Microwave Irradiation. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2011, 29, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, X.; Zhong, H.; Zhang, H.; Xu, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhan, S.; Crittenden, J.C. Facilitating Redox Cycles of Copper Species by Pollutants in Peroxymonosulfate Activation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 2637–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Yu, J.; Li, N.; Wang, S. Cu/CuO-Decorated Peanut-Shell-Derived Biochar for the Efficient Degradation of Tetracycline Via Peroxymonosulfate Activation. Catalysts 2023, 13, 1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cheng, X.; Li, P.; Fan, Q.; Wu, D.; Liang, H. Activation of Peroxymonosulfate with Biochar-Supported CuO (CuO@BC) for Natural Organic Matter Removal and Membrane Fouling Control. Chemosphere 2023, 341, 140044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makowska, M.; Dziosa, K. Influence of Different Pyrolysis Temperatures on Chemical Composition and Graphite-Like Structure of Biochar Produced from Biomass of Green Microalgae Chlorella sp. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2024, 35, 103667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Sun, L.; Pei, Z.; Li, H.; Wang, L.; Ma, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, R.; Zhang, Q. New Insight into the Adsorption of Sulfadiazine on Graphite-Like Biochars Prepared at Different Pyrolytic Temperatures. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 413, 137468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Yu, L.; Song, C.; Chen, Z.; Meng, F.; Song, M. Selective Degradation of Electron-Rich Organic Pollutants Induced by CuO@Biochar: The Key Role of Outer-Sphere Interaction and Singlet Oxygen. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 10710–10720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed Alsharif, M.; Alatawi, A.; Hamdalla, T.A.; Alfadhli, S.; Darwish, A.A.A. CuO Nanoparticles Mixed with Activated BC Extracted from Algae as Promising Material for Supercapacitor Electrodes. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveen Kumar, D.; Shankar, M.V.; Kumari, M.M.; Sadanandam, G.; Srinivas, B.; Durgakumari, V. Nano-Size Effects on CuO/TiO2 Catalysts for Highly Efficient H2 Production under Solar Light Irradiation. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 9443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Wan, Y.; Zhou, H.; Cai, Y.; Zhu, M.; Dang, Z.; Yin, H. Mechanisms and Influencing Factors for Electron Transfer Complex in Metal-Biochar Nanocomposites Activated Peroxydisulfate. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 438, 129461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Qu, G.; Sun, Q.; Jia, H.; Wang, T.; Zhu, L. Endogenously Activated Persulfate by Non-Thermal Plasma for Cu(II)-EDTA Decomplexation: Synergistic Effect and Mechanisms. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 406, 126774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wang, Q.; Soklun, H.; Qu, G.; Xia, T.; Guo, X.; Jia, H.; Zhu, L. A Green Strategy for Simultaneous Cu(II)-EDTA Decomplexation and Cu Precipitation from Water by Bicarbonate-Activated Hydrogen Peroxide/Chemical Precipitation. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 370, 1298–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Guo, L.; Zhang, B.; Liu, H.; Qu, J. Photoelectrocatalytic Oxidation of Cu(II)-EDTA at the TiO2 Electrode and Simultaneous Recovery of Cu(II) by Electrodeposition. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 4480–4488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; He, S.; Kou, L.; Peng, J.; Liu, H.; Zou, W.; Cao, Z.; Wang, T. Highly Efficient Cu-EDTA Decomplexation by Ag/AgCl Modified MIL-53(Fe) under Xe Lamp: Z-Scheme Configuration. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 306, 122588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Li, T.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Jia, H.; Wang, T.; Zhu, L. Highly Effective Photocatalytic Decomplexation of Cu-EDTA by MIL-53(Fe): Highlight the Important Roles of Fe. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 424, 130515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Ding, Y. Application of Sodium Alginate/Iron Sulfide/Biochar Beads as Electron Donors to Enhance Nitrate Removal from Carbon-Limited Wastewater. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 477, 147079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Xie, Q.; Sha, Y.; Qian, S.; Liu, J.; Liang, D. Hydrothermal Pretreatment for Controlling Bamboo Biomass Composition and Regulating Pore Structure of Bamboo-Based Activated Carbon for CO2 Adsorption. J. Energy Inst. 2026, 124, 102341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Ni, J.; Gao, Y. Correlation Between Biochar Pore Structure-Nitrogen Defects and Tetracycline Hydrochloride Degradation. China Environ. Sci. 2022, 42, 3370–3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.B.; Shan, J.H.; Chen, Z.B.; Lichtfouse, E. Efficient Recovery of Phosphate from Simulated Urine by Mg/Fe Bimetallic Oxide Modified Biochar as a Potential Resource. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 784, 147546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.; Haderlein, S.B.; Lutze, H.V.; Sun, C.; Fink, F.; Paul, A.; Spahr, S. Persulfate Activation by Biochar for Trace Organic Contaminant Removal from Urban Stormwater. Water Res. 2025, 284, 123921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, R. Removal of Cr(VI) from Aqueous Solution by Rice-Husk-Based Activated Carbon Prepared by Dual-Mode Heating Method. Carbon Resour. Convers. 2023, 6, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, G.; Liu, C.; Gao, J.; Dionysiou, D.D.; Zhou, D. Manipulation of Persistent Free Radicals in Biochar to Activate Persulfate for Contaminant Degradation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 5645–5653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Sánchez-Montes, I.; Luo, H.; Qu, L.; Wang, J.; Chelme-Ayala, P.; Luo, Z.; Gamal El-Din, M. Activation of Persulfate by Visible-Light-Driven Fe(II)/Fe(III) Cycle of Ferric Citrate for Decomplexation of Cu(II)-EDTA. J. Water Process. Eng. 2024, 63, 105484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, B.; Rui, M.; Liu, J.; Lu, G. Comparison of Toxicity Induced by EDTA-Cu after UV/H2O2 and UV/Persulfate Treatment: Species-Specific and Technology-Dependent Toxicity. Chemosphere 2020, 240, 124942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Othmani, A.; Selatnia, A.; Hamitouche, A.; Bachari, K. Sustainable Biosorption of Cationic Textile Dyes (BY28, BB41, BR46) from Aqueous Solutions Using Pharmaceutical Waste Biomass (Streptomyces Rimosus): Comparative Study in Single, Binary, and Ternary Systems. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 76, 108103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).