Abstract

Knowledge tracing is a methodological framework focused on modeling and predicting learners’ future performance on tasks involving related concepts, while also tracking the dynamic evolution of their knowledge over time. The current study aims to assess the effectiveness of an intelligent learning system (ILS) based on the Knowledge Tracing Model in improving academic passion, self-efficacy, and achievement among 100 students enrolled in a Special Care course. A quasi-experimental design was employed via a single experimental group without a control group. Three instruments—achievement test, self-efficacy, and academic passion—were administered pre- and post-intervention. A statistically significant improvement was observed across all three domains. The findings suggest a positive association between the use of the ILS and gains in academic achievement, self-efficacy, and academic passion. In conclusion, the results support the use of knowledge-tracing-based learning systems for academic performance enhancement and university students’ motivation.

1. Introduction

The advancement of intelligent learning systems (ILSs) is reshaping teaching and learning methodologies by integrating big data, artificial intelligence, and educational practices [1]. These systems support personalized learning, online instruction, and intelligent assessment, thereby enhancing the overall learning experience. Findings suggest that ILSs can increase learning performance by up to 30% compared to traditional methods [2], based largely on their ability to provide instant and personalized assistance.

The ILSs are characterized by a modular architecture, integration of student, expert, and pedagogical models, adaptive and personalized instruction, advanced knowledge representation, and the use of modern technologies to enhance the learning environment [3]. Their design also involves careful consideration of data collection, learner modeling, and automation to provide effective and individualized learning experiences [4].

Within these systems, Knowledge Tracing (KT) plays a crucial role by predicting students’ future performance on concept-related tasks and monitoring their evolving knowledge states [1]. The concept of knowledge tracing was first proposed by Anderson and colleagues in a 1986 technical report on cognitive modeling and intelligent tutoring [5] and was subsequently published in the Artificial Intelligence journal in 1990 [6]. With the rise of massive open online courses and web-based intelligent tutoring systems, students can now receive tailored guidance and acquire knowledge while working through exercises [7]. Each exercise requires the application of one or more underlying concepts. For instance, solving 10 × 20 involves the concept of integer addition, whereas solving 10 × 20 + 5.2 requires both integer addition and decimal addition. A student’s likelihood of answering an exercise correctly depends on their knowledge state—the extent to which they have understood and internalized the relevant concepts [8].

KT refers to the problem of predicting future learner performance given their past performance in educational applications [9]. The objectives of KT are 1. to monitor how a student’s knowledge evolves by analyzing their previous responses to exercises, and 2. to track the progress of a student in terms of the knowledge or skills developed throughout a learning process [10].

This predictive capability enables educators to more effectively identify learners’ needs and deliver individualized instruction accordingly. Moreover, KT provides a scientific foundation for data-informed educational decisions, supporting both educators and policymakers in designing effective, evidence-based strategies that align with learners’ actual progress and requirements [1].

KT tracks learners’ development by analyzing their strengths and weaknesses as inferred from interactions with the educational system. It is widely applied in ILSs, leveraging machine learning algorithms to assess student progress and forecast future performance based on prior learning activities. The core objective of KT is to predict a learner’s next response or performance based on their historical interactions with educational content, such as exercises or quizzes. By accurately modeling a student’s knowledge state, instructors and ILSs can deliver personalized feedback, adapt learning pathways, and enhance educational outcomes [11].

Traditional KT methods, such as those based on Bayesian Knowledge Tracing (BKT) [12], employ Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) to model learners’ cognitive states. BKT is based on the assumption that a learner’s knowledge state can be categorized as known or unknown and then updates the state according to the learner’s performance on different tasks. While BKT has been widely used, it is limited by its inability to capture complex relationships between different knowledge concepts and its dependence on predefined skill labels.

Recent years have seen significant improvement in the field of knowledge tracing (KT) through advances in deep learning models. Recent models like Deep KT (DKT) use neural networks to enhance the precision of knowledge tracking, hence providing more effective and accurate support to learners [13].

Substantial research supports the idea that the application of Knowledge Tracing can significantly improve students’ academic performance. By providing instantaneous feedback and personalized guidance, students can improve their understanding of the subject, increase their rates of achievement, and reduce the time to learn new skills by up to 50% compared to traditional instruction [14]. In addition, ILSs can personalize learning experiences by analyzing student information to identify areas requiring improvement and providing personalized educational materials to address challenges.

ILS helps students improve learning by creating a learning environment that aids in effective management of time and resources. Existing research has shown students who use IESs that support multitasking make improvements in both time management and academic productivity [15].

The connection between learning and Knowledge Tracing is both interesting and intricately related. Knowledge Tracing models play a central role in nurturing students’ capacity to effectively multitask. Through the examination of students’ interactions with the learning platform to gauge their mastery of different skills, the models lead learners towards areas needing improvement. This personalized guidance supports the acquisition of skills by encouraging a strategic distribution of effort across different tasks based on the learners’ mastery levels. Lu et al. [16] state that learning systems that integrate Knowledge Tracing have the potential to enhance the ability of learners to transition between tasks without disruptions, ultimately leading to improved overall academic performance.

In e-learning contexts, students often face difficulties in allocating their time and resources across concurrent tasks. Adaptive learning systems—by tracking learners’ ongoing knowledge acquisition and adapting task sequencing accordingly—can offer personalized guidance to optimize effort allocation [17]. For example, when a system detects mastery in a particular skill, it can redirect the learner to tasks requiring more attention, thus helping manage workload and reduce overwhelm [18]. Such systems have been shown to maximize learning efficiency under constraints of limited time and motivational resources [19], and adaptive task-assignment algorithms have demonstrated effectiveness in recommending tasks tailored to student competence [20]. Moreover, adaptive e-learning environments have been associated with improvements in self-regulated learning, which inherently involves better time and resource management by learners [21].

In addition, Knowledge Tracing can determine the optimal intervals for task switching. For example, if Knowledge Tracing shows that a student becomes distracted after a certain period of task involvement, the system can suggest breaks or task restructuring in order to maintain continuity without compromising concentration. This approach is based on cognitive psychology theories that argue task switching can have positive effects if done in the right way. Ludwig et al. [21] argues that performance can be enhanced via task switching, but only if the switching is carefully designed on the basis of an overall analysis of individual capacity and needs.

In summary, Knowledge Tracing is a key element for the future development of learning owing to its ability to provide accurate measures of student learning and adaptive recommendations based on those measures. It is envisioned that the incorporation of Knowledge Tracing into task management will translate into dramatic improvements in learning outcomes and increase student satisfaction during the learning process. Liu et al. [13] added that there are modern Knowledge Tracing models such as Deep Knowledge Tracing (DKT), which can provide better analysis of students’ interactions with different tasks and thus increase the efficiency of Intelligent Educational Systems (IESs).

Additionally, Knowledge Tracing provides students with a clear view of their strengths and weaknesses, thus making it easier to identify areas of improvement in specific areas. This level of openness enables students to set realistic and achievable goals, thereby increasing their perceived agency in the learning process. Once students realize that they have the capacity to improve performance through objective testing, they develop increased self-efficacy, thus engaging in academic tasks with increased confidence. Schunk and Pajares [22] illustrated that students who receive accurate and specific feedback tend to develop higher levels of self-efficacy, which directly affects their academic performance.

Notably, Self-Determination Theory [23] provides a principled lens to map Knowledge Tracing (KT) personalization features onto the three basic psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Several Intelligent Tutoring System (ITS) studies show that SDT-style designs effectively raise motivation and engagement. Furthermore, SDT-based ITS interventions have been shown to improve academic engagement, motivation, and perceived competence in targeted populations, suggesting clear mechanistic targets for KT personalization. For example, Chen et al. reported improved engagement and motivation from an ITS design focused on enhancing autonomy, competence, and relatedness [24].

Self-efficacy is a core psychological measure that affects accomplishment in educational environments because it refers to an individual’s belief in his or her ability to perform well in learning activities. Knowledge Tracing plays a key role in developing self-efficacy by providing immediate and accurate feedback that truly reflects students’ progress through different skills. The recognition of continuous improvement in their performance, as shown through Knowledge Tracing measures, increases their confidence in their abilities and motivates them to put more effort into achieving their learning goals. Bandura and Wessels [25] posited that positive and accurate feedback is an essential element in the development of self-efficacy.

In addition, Knowledge Tracing helps to reduce frustration exhibited by students when their learning process is hindered. By drawing on insights gained through Knowledge Tracing to create customized learning strategies, the system hopes to help students overcome challenges step by step, thereby enhancing their feelings of achievement and self-efficacy. This approach is based on the principles of educational psychology, which argue that success in smaller tasks can enhance self-efficacy and get learners to work harder on more complex problems. Zimmerman [26] noted that learners who feel they are in charge of their learning situations tend to develop higher levels of self-efficacy.

In conclusion, Knowledge Tracing offers potent strategies for enhancing self-efficacy through the provision of accurate information on students’ performance coupled with customized recommendations based on this information. The connection between Knowledge Tracing and self-efficacy offers an opportunity for significant improvements in academic performance, as well as higher student satisfaction with the learning process. Aleven et al. [27] showed that Intelligent Educational Systems (IESs) based on Knowledge Tracing can support students’ self-efficacy by providing them with effective and adaptive learning experiences.

Knowledge Tracing provides students with a clear insight into their progress in gaining varied skills, enabling them to identify areas of improvement and areas where they have been successful. This openness creates a greater sense of autonomy over their learning process, thus enhancing their motivation and readiness to continue with their studies. To the extent that students see their potential for improvement as presented through unbiased measurements, it enhances their passion for learning and encourages them to face learning challenges with greater determination. Fredricks et al. [28] suggested that students who feel in control of their learning activities are more likely to develop a strong sense of academic passion.

In addition, Knowledge Tracing could also stimulate academic interest by providing challenging and engaging learning experiences. For example, the system can create learning challenges that precisely assess learners based on their current skill levels, thus motivating them to seek more knowledge. This approach conforms to educational psychology theories that advocate for the use of appropriate challenges to foster motivation and interest in learning. As espoused by Deci and Ryan [29], students who face challenges that are commensurate with their levels of competency are likely to develop a higher interest in academic activities.

Academic passion is characterized by a strong enthusiasm and dedication to the pursuit of knowledge and academic achievement, inspiring students to work towards excellence in academic pursuits. Knowledge Tracing plays a very important role in perpetuating this passion by executing personalized and stimulating learning experiences that always respond to the progress of the students. When students notice performance gains due to Knowledge Tracing feedback, it enhances their feelings of accomplishment and motivates them to put more effort into achieving their academic goals. Vallerand and Houlfort [30] opined that academic passion is nurtured through a series of achievements as well as awareness of progress, which can be made easier using Knowledge Tracing tools.

Overall, Knowledge Tracing offers strong methods for increasing academic motivation through the provision of accurate insights into students’ progress, in addition to recommendations based on this information. This connection between Knowledge Tracing and academic motivation is likely to offer significant improvements in educational achievement, as well as increased student satisfaction with educational experiences. Liu et al. [13] argue that new models of Knowledge Tracing, including Deep Knowledge Tracing, can offer a better picture of how to engage students and increase their academic motivation.

It is evident from the above that IESs play a pivotal role in enhancing learning, self-efficacy, and academic passion among students. By providing immediate and personalized feedback and analyzing student data to offer precise educational recommendations, these systems can improve students’ management of multiple tasks, increase their confidence in their abilities, and boost their enthusiasm and interest in learning. This study aims to explore the impact of an IES based on the Knowledge Tracing model on these three aspects, contributing new insights to improve the learning experience and enhance students’ academic outcomes.

Despite the numerous benefits related to Instructional Evaluation Systems (IESs), various challenges make their implementation difficult, including the need for a whole technological infrastructure and proper training for teachers to effectively use these systems [30]. However, the expected benefits of using such systems outweigh the related disadvantages, particularly regarding improving the quality of education. Heffernan and Heffernan [31] reported that investing in technological infrastructure and teacher training can significantly enhance the effectiveness of IESs.

KT has made significant progress in modeling learners’ cognitive mastery. However, important gaps remain concerning its integration with motivational and emotional factors [32]. Most KT models focus primarily on performance prediction and knowledge-state estimation, giving limited attention to affective–motivational constructs such as self-efficacy and academic passion [33]. Additionally, current models exhibit technical and conceptual limitations, including shallow representations of cognitive processes, difficulties in capturing long-term learning dependencies [34], and reliance on expert-defined mappings between items and knowledge components.

The intelligent learning system proposed in this study addresses these limitations by incorporating emotional, behavioral, and motivational data into KT-driven personalization. This approach enables more adaptive and holistic learner support compared to traditional KT models [35]. The system enhances real-time learning path analysis and extends learner modeling beyond purely cognitive indicators [36].

Despite these advancements, empirical evidence on the direct effects of KT-based interventions on motivational outcomes remains limited [37]. The mechanisms through which personalized KT feedback influences self-efficacy, academic passion, student engagement, and long-term achievement are still insufficiently understood [38]. Addressing this gap represents a central objective of the present study.

1.1. The Current Research

This research aims to investigate the association between the use of an Intelligent Learning System (ILS) based on the BKT model and improvements in academic achievement, self-efficacy, and academic passion. By designing and implementing this system, we hope to provide new insights that contribute to improving the learning experience and enhancing students’ academic outcomes.

1.2. Research Hypotheses

H1.

There is a statistically significant increase in the Cognitive Achievement scores of the experimental group in the Special Care course from pre-test to post-test.

H2.

There is a statistically significant improvement in the self-efficacy scores of the experimental group from pre-test to post-test.

H3.

There is a statistically significant enhancement in the academic passion scores of the experimental group from pre-test to post-test.

H4.

There are no significant differences in post-test achievement, self-efficacy, or academic passion scores between male and female students.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design and Participants

The current study employed a quasi-experimental design with a single experimental group comprising approximately 167 student participants who initially engaged with a smart learning platform. However, only 100 students completed the full experimental process, of which 57 female and 43 males. The group was assessed using a pre-test/post-test approach to measure academic achievement, self-efficacy, and academic passion. The experimental intervention involved the use of an intelligent learning system based on the Knowledge Tracing Model. All participants, aged between 20 and 51, were selected during the first term of the 2024–2025 academic year. Instruction was delivered by the same instructors for Blended Learning students in Level Four, majoring in Digital Educational Technology, enrolled in the course ‘Special Needs Care’. Participation was voluntary, and all students completed an informed consent form before beginning the study. Students were informed about data confidentiality, the academic purpose of the research, and their right to withdraw at any time without academic consequences. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by Fayoum University.

2.2. Research Instruments

The study used three primary measurement instruments.

- Academic Achievement Test:

The study employed three primary measurement instruments. First, the academic achievement test consisted of 116 items designed to assess students’ mastery of course content. Items were reviewed by 5 experts to ensure content validity and balanced coverage across Bloom’s taxonomy levels. Item analysis, including item difficulty and standard deviation, indicated variability in item performance and an appropriate range of difficulty across the test (e.g., item means ranged from 0.11 to 0.88, standard deviations ranged from 0.316 to 0.504). Content validity was further examined through expert judgment by eleven specialists in psychometrics, psychology, and educational technology, who evaluated the relevance, clarity, and suitability of the items for the target population. The content validity index (CVI) exceeded 0.90 for all items. Its reliability was evaluated using the split-half method with a sample of 72 students, yielding a coefficient of 0.94 following the application of the Spearman–Brown correction. These results indicate that the achievement test demonstrates strong validity and high reliability.

- 2.

- Self-Efficacy Scale

The Self-Efficacy Scale used in this study was developed within the theoretical framework of the General Self-Efficacy Scale developed by Schwarzer and Jerusalem [39], which conceptualizes self-efficacy as individuals’ generalized beliefs in their capacity to cope with a wide range of challenging and stressful situations. Drawing on this framework, the present scale was designed to measure students’ self-efficacy in academic, social, and performance contexts, ensuring cultural relevance and contextual appropriateness for Arab populations.

Content validity was established through expert review by eleven specialists in psychology, psychometrics, and educational measurement, who evaluated the relevance, clarity, and cultural appropriateness of the items. Based on their feedback, minor revisions were made to enhance item clarity and contextual suitability. The final version administered in this study consisted of 34 items. Exploratory factor analysis with varimax rotation, conducted on a pilot sample of 134 students, revealed a clear three-factor structure, consistent with the theoretical conceptualization of self-efficacy in academic settings. Factor 1—Academic Self-Efficacy/Task Mastery (17 items, loadings 0.310–0.684) reflects students’ confidence in completing academic tasks, solving problems, managing multiple assignments, and adapting to challenges. Factor 2—Interpersonal Self-Efficacy (13 items, loadings 0.361–0.644) captures students’ perceived ability to interact effectively with peers, build trust, and cope with social challenges. Factor 3—Performance Orientation/Competitive Self-Regulation (4 items, loadings 0.371–0.824) reflects the influence of social comparison and evaluation on academic performance.

All items loaded above the commonly accepted threshold of 0.30, with minimal cross-loadings, supporting the distinctiveness of the three dimensions. Together, the three components accounted for a substantial portion of the variance, providing evidence for the construct validity of the scale. Internal consistency reliability was examined using Cronbach’s alpha, yielding a coefficient of 0.81, which indicates acceptable reliability. Factor analysis was conducted. Overall, the scale demonstrated satisfactory validity and adequate reliability for use with the study population.

- 3.

- Academic Passion Scale

The Academic Passion Scale consisted of 22 items and was developed with reference to the theoretical framework and prior work of Vallerand et al. [40]. The scale was designed to assess students’ levels of academic passion. The Academic Passion Scale employed a five-point Likert-type response format ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Content validity was established through expert evaluation by specialists in psychology, psychometrics, and education, who reviewed the items for relevance, clarity, and alignment with the construct of academic passion within the academic context. Minor modifications were made based on expert feedback to improve item wording and contextual appropriateness. The final version of the scale comprised 22 items. Factor analysis, conducted on a pilot sample of 134 students using varimax rotation, revealed a clear two-component solution. The first component included 12 items (I1–I12) representing harmonious academic passion, and the second component comprised 10 items (I13–I22) reflecting obsessive academic passion. All component loadings exceeded 0.30, with no substantial cross-loadings, supporting the distinctiveness of the two dimensions. The two-component solution accounted for 40.3% of the total variance, meeting the commonly accepted minimum threshold for scales in psychological and educational research. This structure provides evidence for the construct validity of the scale. Reliability analysis yielded a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.78, indicating acceptable internal consistency. Overall, the Academic Passion Scale demonstrated satisfactory validity and adequate reliability for use in the present study.

2.3. Implementation Procedures for the Proposed Learning Environment

2.3.1. Intelligent Learning System and Knowledge Tracing Model

The intelligent learning environment used in this study was developed specifically for research purposes by the Educational Technology Department at [Fayoum University]. The system was hosted on a secure, university-managed server and automatically adapted learning content, sequencing, and feedback based on students’ predicted mastery levels.

The system integrates a Bayesian Knowledge Tracing (BKT) model to estimate learners’ mastery states in real time. BKT was selected due to its interpretability, computational efficiency, and suitability for mastery-learning environments. BKT conceptualizes knowledge as a hidden binary variable that evolves over time, while observed student responses serve as evidence used to update the probability of mastery.

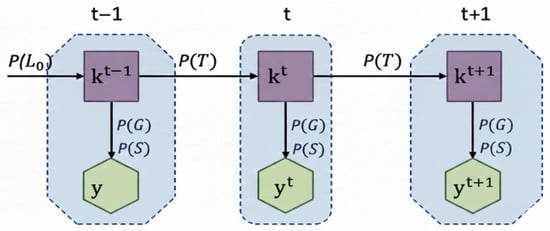

The BKT model applied four standard parameters—initial mastery (p(L0)), learning rate (p(T)), slip (p(S)), and guess probability (p(G))—implemented, where

- -

- Prior probability (P(L0)) represents the learner’s initial likelihood of having mastered a given knowledge concept before engaging with the learning activities.

- -

- Guess probability (P(G)) reflects the chance that a learner provides a correct response despite not actually mastering the concept.

- -

- Slip probability (P(S)) reflects the chance that a learner provides an incorrect response even though the concept has already been mastered.

- -

- Transition probability (P(T)) denotes the likelihood that a learner who has not yet mastered a skill will achieve mastery after the subsequent learning or practice opportunity.

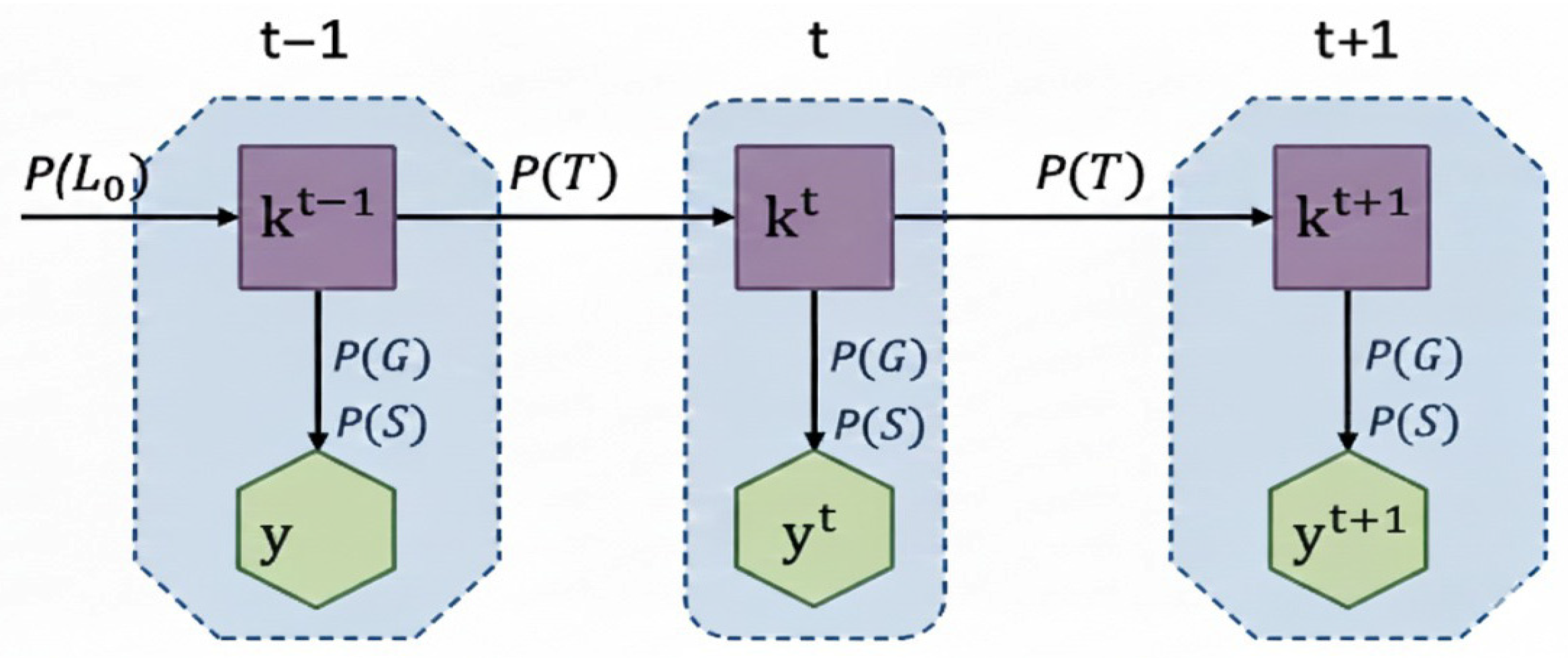

Figure 1 illustrates the temporal structure of the Bayesian Knowledge Tracing (BKT) model across three consecutive opportunities (t − 1, t, t + 1). At each step, the model maintains and updates a probabilistic estimate of the learner’s mastery of a specific skill based on observed performance.

Figure 1.

KBT model.

- Initial Knowledge (P(L0))

The learning process begins with P(L0), the prior probability that the learner has already mastered the target skill before any interaction occurs. This prior initializes the first hidden state and sets the baseline belief from which all subsequent updates are made. In the figure, P(L0) feeds into the earliest latent state (kt−1).

- 2.

- Hidden Mastery State (kt)

At each time step t, the model represents the learner’s true but unobservable mastery state using kt. The probability P(kt) reflects whether the learner is in the mastered or non-mastered state. These latent states form a temporal chain, as shown in the horizontal transitions connecting kt−1, kt, and kt+1.

- 3.

- Learning Transition Probability (P(T))

Transitions between consecutive hidden states are governed by P(T), which denotes the probability that a learner moves from the non-mastered to the mastered state between two opportunities. This parameter represents the acquisition of knowledge and is illustrated by the arrows linking the hidden states across time steps.

- 4.

- Observation Model: Guess and Slip Probabilities (P(G), P(S))

Observable performance at each time step is represented by yt, the learner’s actual response. The model uses the guess (P(G)) and slip (P(S)) probabilities to define the likelihood of correct or incorrect responses given the hidden mastery state. Each observed response updates the posterior estimate of mastery, completing the recursive cycle.

- 5.

- Observable Response (yt)

The variable yt represents the learner’s actual response at time t. Each observed response (correct or incorrect) is generated according to the guess and slip probabilities and is used to update the posterior estimate of the learner’s mastery. This completes the recursive cycle in which observation informs and refines the evolving latent state.

2.3.2. System Origin and Technical Specifications

The platform was developed using Python (version 3.12.7) and integrated with a MySQL database for storing student interaction logs. The algorithmic engine relied on the pyBKT open-source framework (version 1.7) as the core library for the Knowledge Tracing model. The user interface was built on a web-based dashboard enabling students to perform tasks, receive feedback, and view recommended resources. The platform provided real-time analysis of learner input and delivered automated content sequencing based on mastery estimates. The smart learning environment was developed collaboratively by all authors, with clearly defined roles in design, content preparation, data entry, and evaluation. The total production cost was approximately $2000, demonstrating that the system can be deployed cost-efficiently. This practical consideration, alongside instructor involvement in system development and evaluation, underscores the feasibility of integrating such technology in educational settings.

2.3.3. Pedagogical Role of Knowledge Tracing in Personalization

Knowledge Tracing models aim to monitor the development of students’ knowledge throughout the learning process and to predict their performance on future tasks. By more accurately measuring students’ knowledge levels, these models can be used to personalize learning plans, thereby maximizing learning efficiency.

Furthermore, Knowledge Tracing models enable the tracking of changes in students’ knowledge states. Once these states are understood, the intelligent learning system can tailor learning experiences to match individual students’ competencies. This approach not only supports personalized instruction but also helps students better understand their own learning trajectories and focus on improving areas where they exhibit weak mastery.

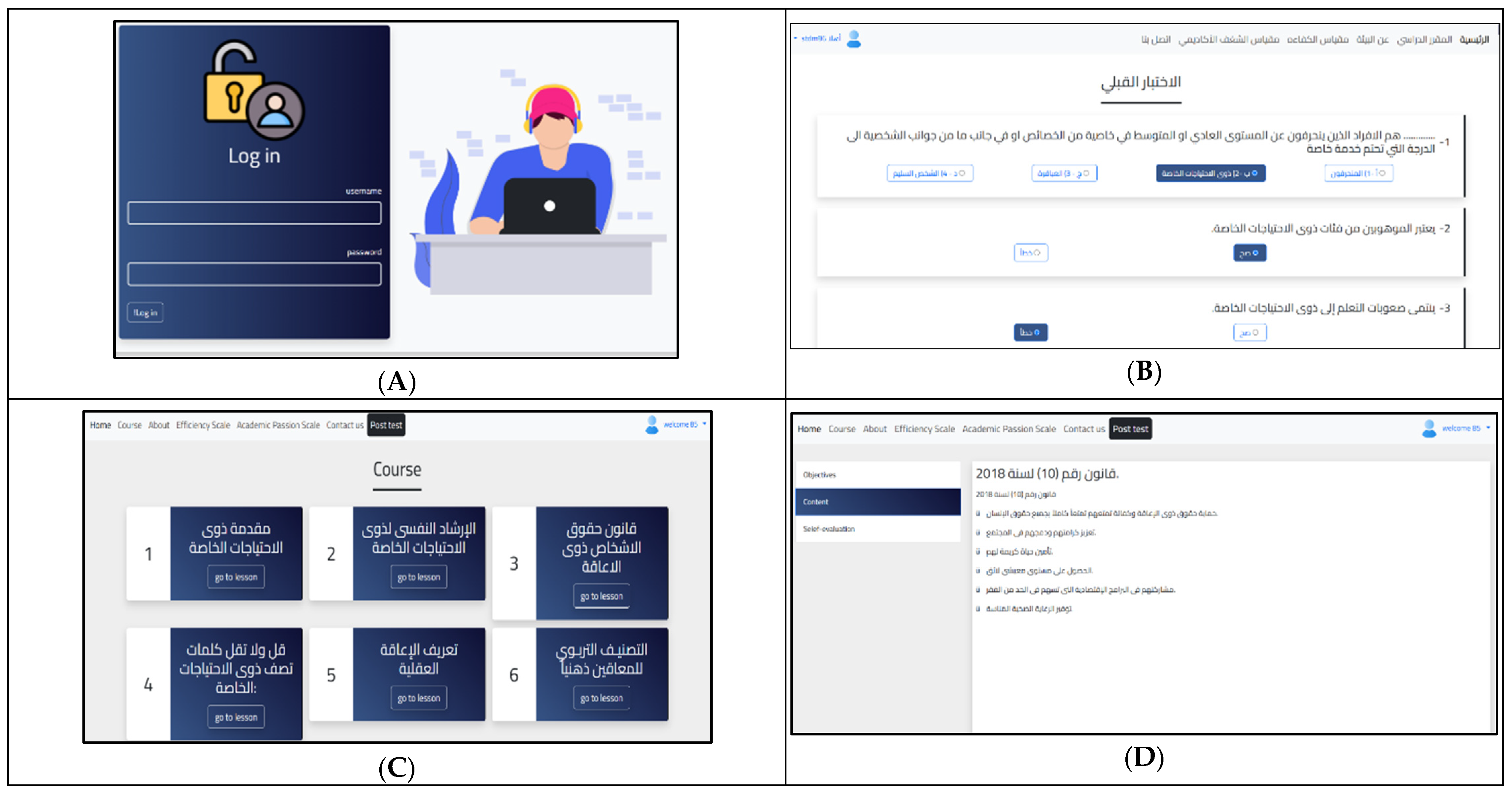

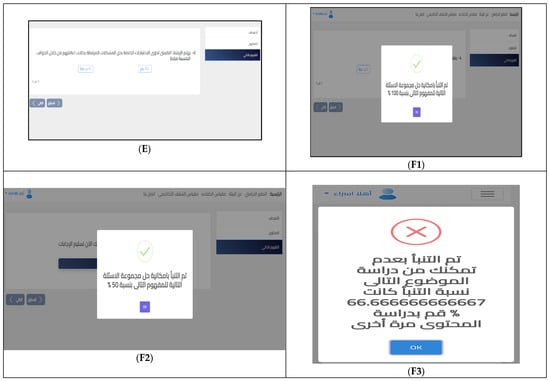

Figure 2 illustrates several screens from the proposed learning environment, including:

Figure 2.

Implementation procedures for the proposed learning environment. (A) Each student logs into the environment; (B) Each student first takes the pre-test for the Special Needs Care course; (C) The content of the Special Needs Care course was divided into a set of lessons and concepts (approximately 16 lessons and 49 concepts). (D) Example for lesson: including the lesson objectives, and the self-assessment questions; (E) Self-assessment questions; (F1) KTM indicated a prediction rate of 100% for this student; (F2) KTM indicated a prediction rate of 100% for this student; (F3) KTM indicated a prediction rate of 100% for this student.

- Each student logs into the environment by entering a unique username and password.

- Each student first completes a pre-test for the Special Needs Care course. The purpose of this test is to measure the student’s initial cognitive level before beginning the learning process.

- The course content is divided into a set of lessons and concepts, comprising approximately 16 lessons and 49 concepts. Notably, students cannot proceed to the next lesson unless they have studied the current lesson and answered its associated questions.

- Upon entering a lesson, a screen appears displaying the lesson objectives, content (i.e., the concepts associated with the lesson, which vary in number), and self-assessment questions.

- After studying the lesson content and concepts, the student proceeds to complete the self-assessment questions.

- The system then predicts student performance on subsequent tasks, which determines whether the student can proceed to the next concept or must review the current lesson. This process includes:

- (a)

- For the first student, the prediction rate is 100%. Based on the intelligent learning system’s analysis using the Knowledge Tracing model, the system predicts that this student can master the next concept with full confidence. This high-rate results from the interconnected nature of the concepts, which require mastery of preceding material before progression.

- (b)

- For the second student, the prediction rate is 50%. The system informs the student that there is a 50% likelihood of correctly answering the questions related to the next concept. This prediction is based on the student’s performance in studying and answering questions on the current concept.

- (c)

- For the third student, the system records a prediction rate of approximately 66.7%. This indicates that the student is not yet ready to study or solve questions for the next concept. Consequently, the student is advised to review the current lesson content and its associated concepts due to insufficient mastery.

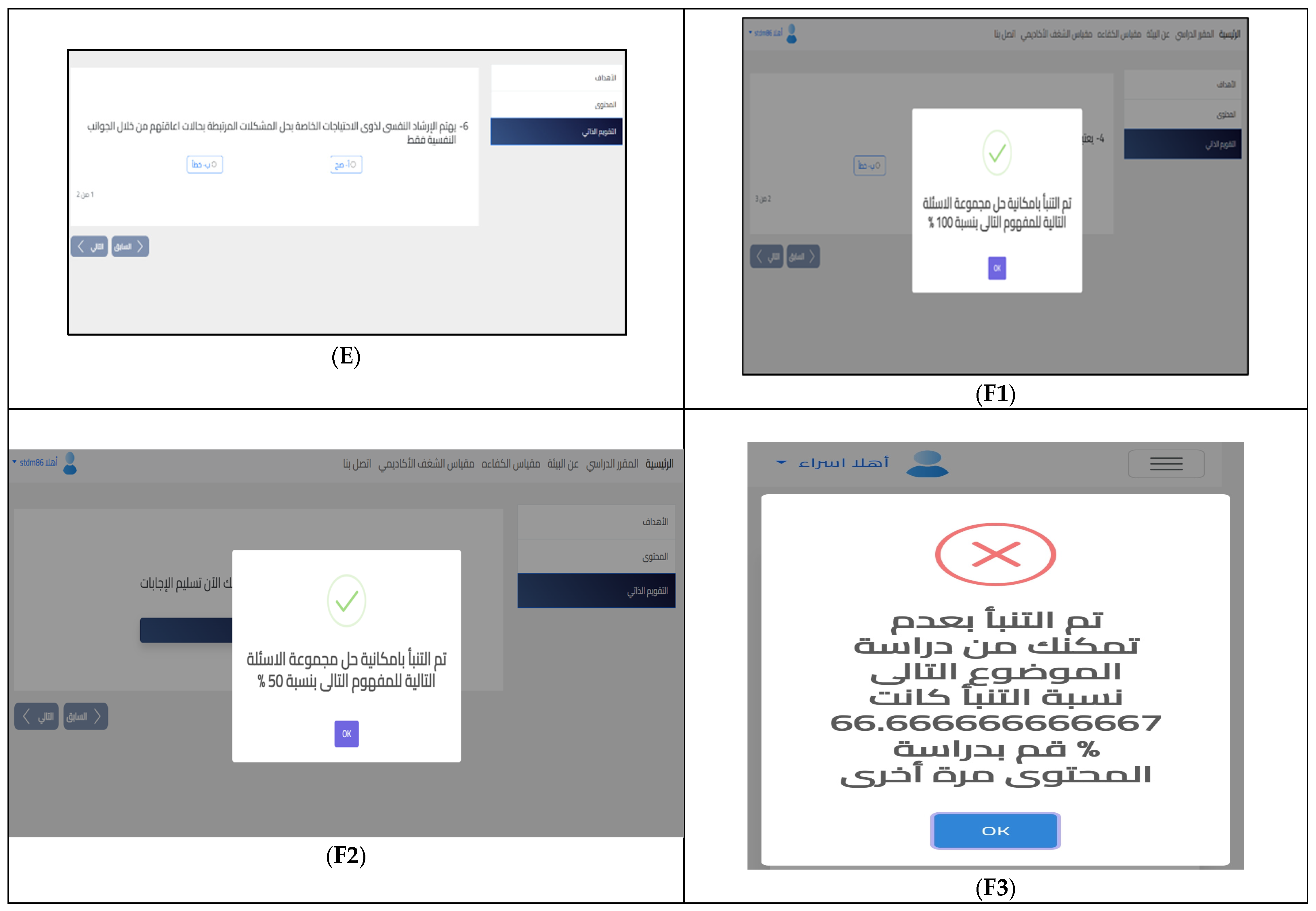

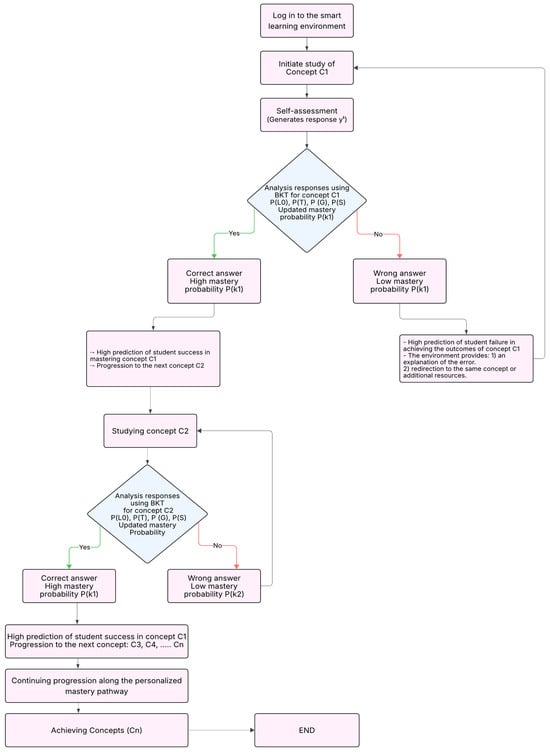

2.3.4. Adaptive Learning Workflow of the Proposed System

Figure 3 illustrates the adaptive learning process implemented in the current study, in which Bayesian Knowledge Tracing (BKT) is employed to personalize instructional pathways within a smart learning environment. This approach is designed to support mastery learning by continuously estimating each learner’s evolving knowledge state and dynamically tailoring the sequence of concepts to individual performance.

Figure 3.

BKT-Driven Adaptive Learning Process Path.

The learning sequence begins when the student logs into the smart environment and initiates study of the first concept (C1). Upon engaging with the instructional material, the student completes a self-assessment activity, generating an observable response (y1). This response is analyzed using the BKT model to update the learner’s mastery probability , based on four core parameters: initial knowledge , transition probability , and the guess and slip probabilities and . This probabilistic update provides a refined estimate of the learner’s current mastery of the concept.

Based on the updated mastery estimate, two outcomes are possible (See Figure 3):

- High Mastery Probability: If the mastery probability exceeds the predefined progression threshold, the system predicts a high likelihood of success for concept C1, allowing the learner to advance to the next concept (C2).

- Low Mastery Probability: If the mastery probability remains below the threshold, the model predicts a higher probability of failure. In this case, the environment delivers targeted remediation, which may include explanations of errors, additional worked examples, redirection to the same concept, or access to supplementary resources to reinforce comprehension.

This cycle is iterative and continues across all subsequent concepts (C2 to Cn). At each step, the learner’s performance generates a new observable response (yt), which triggers a BKT update of the mastery probability . This recursive process ensures progression only when sufficient mastery is demonstrated, thereby minimizing the likelihood of repeated failure and reducing cognitive overload.

As learners progress along their personalized pathways, consistent patterns of success are expected to strengthen self-efficacy and sustain academic passion, both of which are positively associated with higher academic achievement. The final stage reflects the successful attainment of target competencies and completion of the individualized mastery pathway.

Overall, this BKT-driven adaptive learning model exemplifies how data-informed environments can personalize instruction, promote learner autonomy, and enhance educational outcomes by continuously monitoring and responding to each learner’s knowledge state.

2.4. Data Collection and Analysis

A one-group pre-test/post-test quasi-experimental design was employed to examine the impact of the intervention. Data was analyzed using independent-sample t-test, paired-sample t-tests, Bayes Factors, and effect size estimates. To control Type I error across the three outcome variables, a Bonferroni adjustment was applied (α = 0.05/3 = 0.0167). Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 30 [41] and the JASP [42] statistical software (version 0.18.2).

3. Results

This study aimed to examine the effectiveness of an intelligent educational system based on the Knowledge Tracing Model in enhancing achievement, self-efficacy, and academic passion among students enrolled in the Special Care course within the Department of Educational Technology.

Table 1 presents the descriptive and inferential statistics for the three outcome variables. Before conducting paired t-tests, the Shapiro–Wilk test was used to examine normality of the difference scores for each variable. The results indicated that all variables were approximately normally distributed (see Table 1). Additionally, visual inspection of boxplots revealed no extreme outliers. These findings satisfy the assumptions required for paired t-tests.

Table 1.

Mean Differences, Statistical Significance, and Effect Sizes for Pre- and Post-Test Measures.

The first hypothesis posited a statistically significant increase in students’ achievement following the intervention. The results revealed a mean increase from 67.36 (pre-test) to 86.77 (post-test), yielding a statistically significant difference, t(99) = 9.877, p < 0.001, with a large effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.988, 95% CI [0.747–1.230]; η2 = 0.496, 95% CI [0.355–0.63]). These findings indicate that the intelligent system contributed meaningfully to students’ mastery of course content.

The second hypothesis proposed that the intervention would significantly enhance students’ self-efficacy. As shown in Table 1, the mean self-efficacy score increased from 94.78 to 118.50. This difference was statistically significant, t(99) = 15.02, p < 0.001, with a very large effect size (Cohen’s d = 1.50, 95% CI [1.214–1.789]; η2 = 0.695, 95% CI [0.59–0.79]), supporting the hypothesis that the system positively impacted learners’ academic confidence and perceived competence.

The third hypothesis suggested that the intelligent learning system would foster greater academic passion. Results demonstrated an increase in mean scores from 65.03 to 84.27. The paired t-test was statistically significant, t(99) = 17.16, with a very large effect size (Cohen’s d = 1.83, 95% CI [1.514–2.160]; η2 = 0.748, 95% CI [0.66–0.83]), and a Bayes Factor of 0.000, indicating decisive evidence in favor of the alternative hypothesis. These findings suggest that the system substantially elevated students’ emotional engagement and intrinsic motivation toward learning. Because three outcomes were tested, a Bonferroni adjustment was applied (α = 0.05/3 = 0.0167). All results remained significant after correction.

Taking together, the results offer strong empirical support for all three hypotheses. The intelligent educational system based on the Knowledge Tracing Model demonstrated a significant and positive effect on students’ achievement, motivation, and affective learning outcomes. The consistency of large to very large effect sizes across all variables highlights the pedagogical potential of adaptive, data-driven systems in higher education settings.

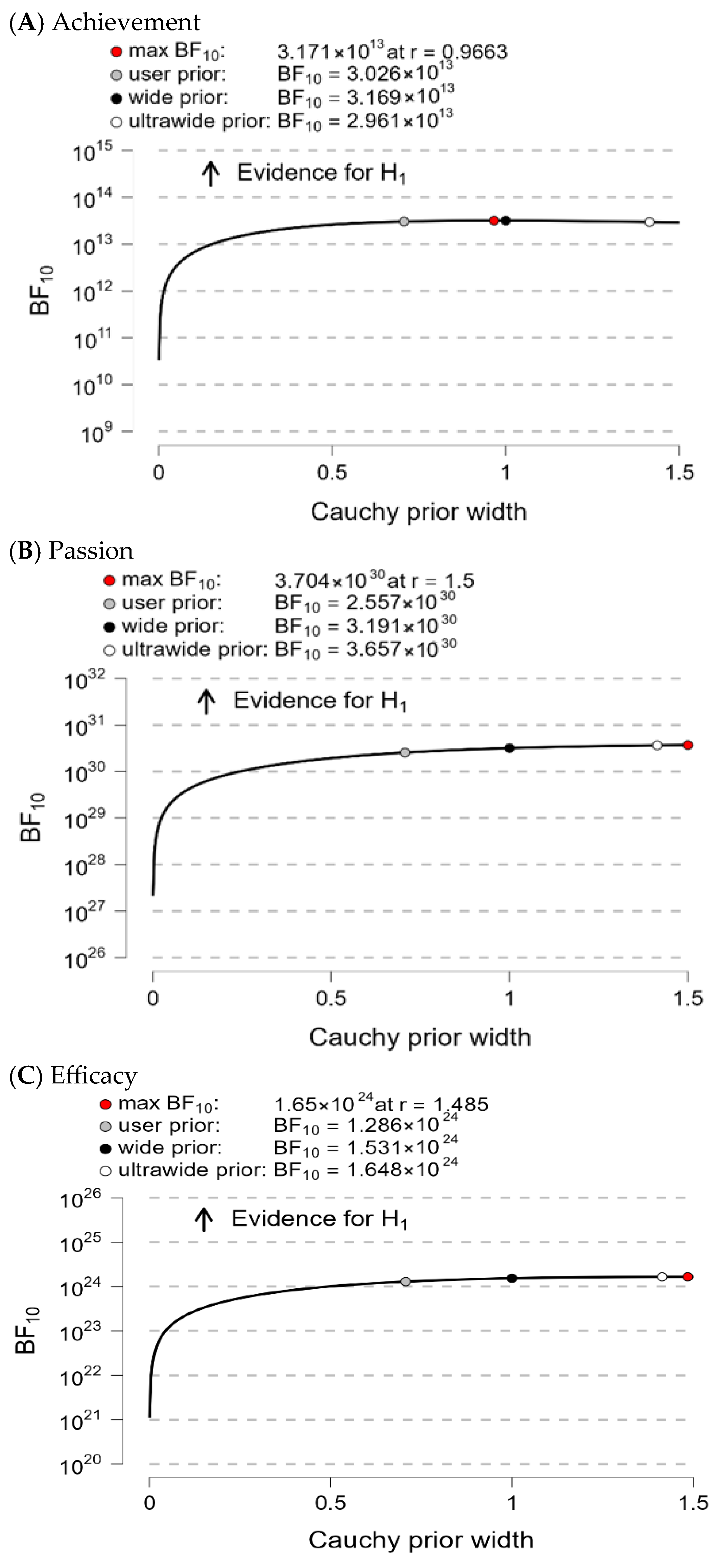

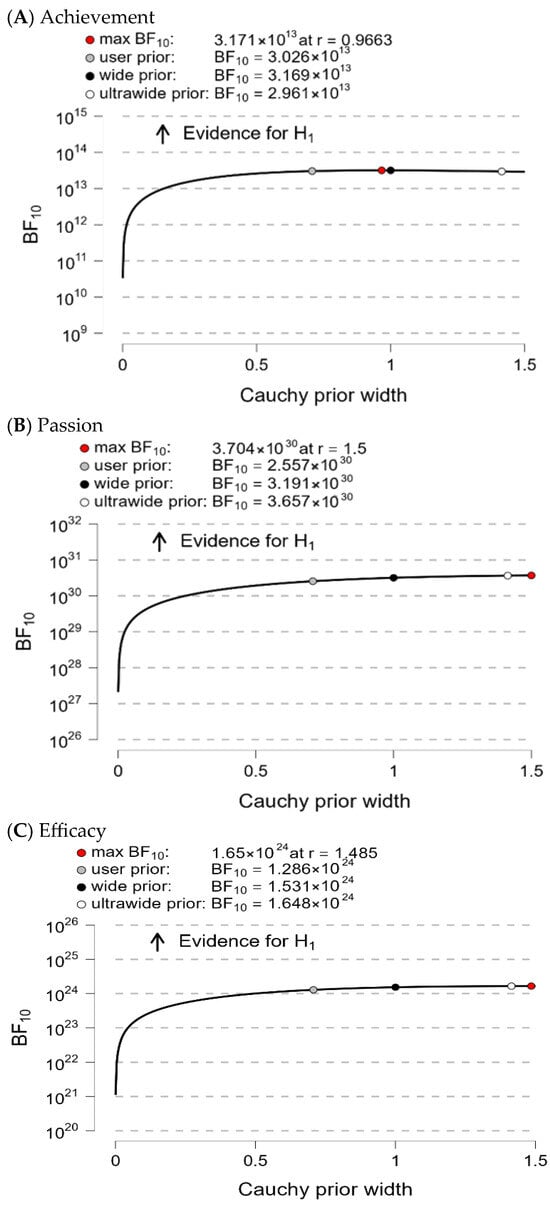

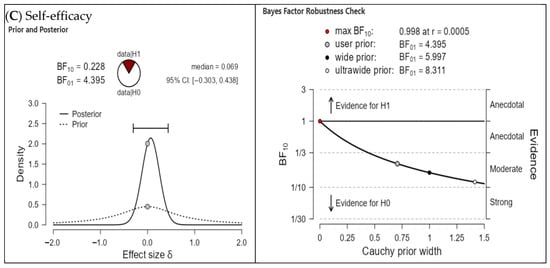

Figure 4 presents Bayes factor robustness check for achievement (A), Academic Passion (B), and Self-Efficacy (C). Bayes factor robustness revealed strong evidence supporting the alternative hypothesis for all three constructs. Achievement showed Bayes factors exceeding (BF10 > 1013), academic passion surpassed (BF10 > 1030), and self-efficacy exceeded (BF10 > 1024), indicating very strong to overwhelming evidence for the presence of effects. These findings remained consistent across user-defined, wide, and ultrawide Cauchy priors, confirming the robustness and reliability of the results.

Figure 4.

Bayes factor robustness check for achievement (A), Academic Passion (B), and Self-Efficacy (C).

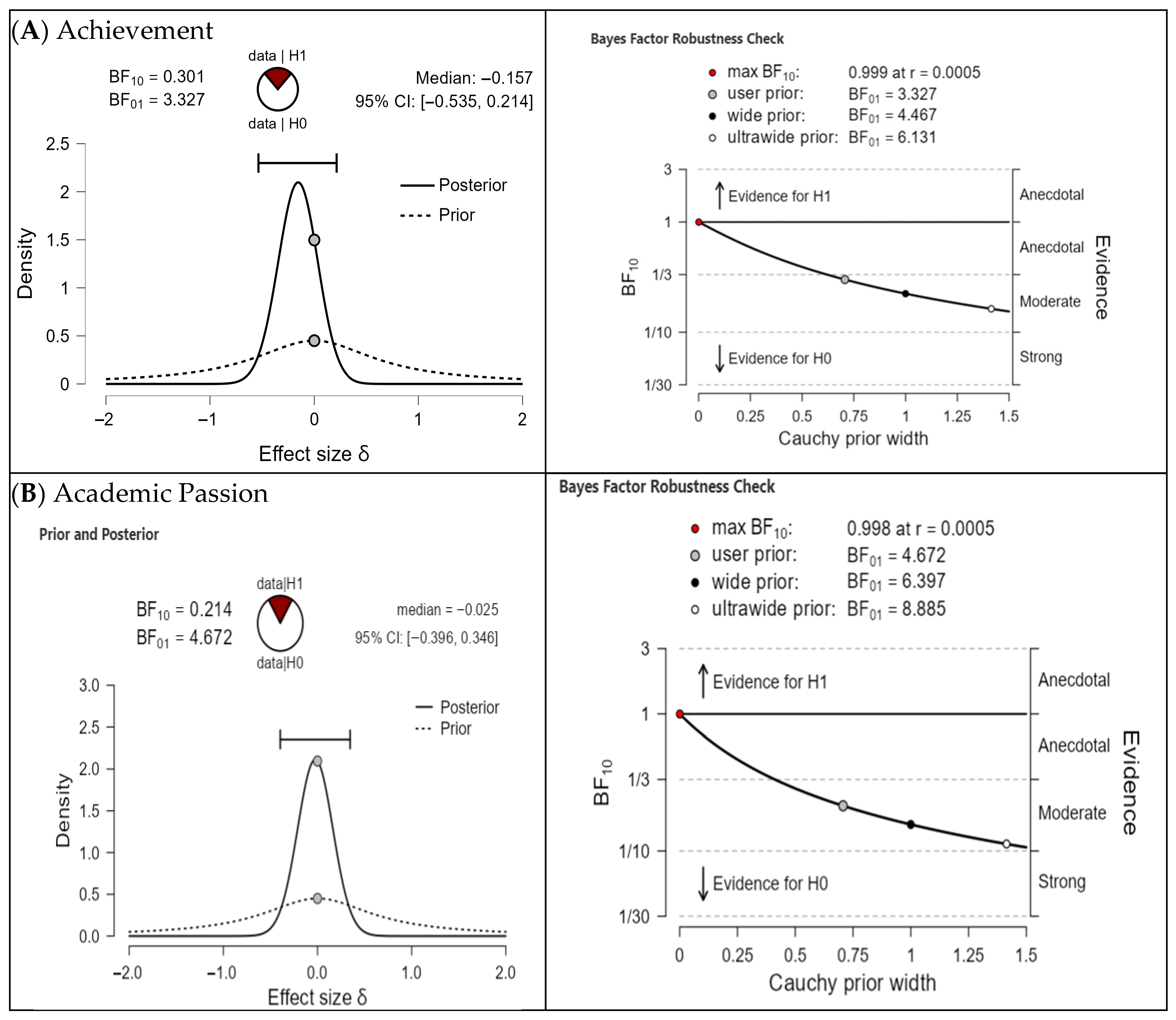

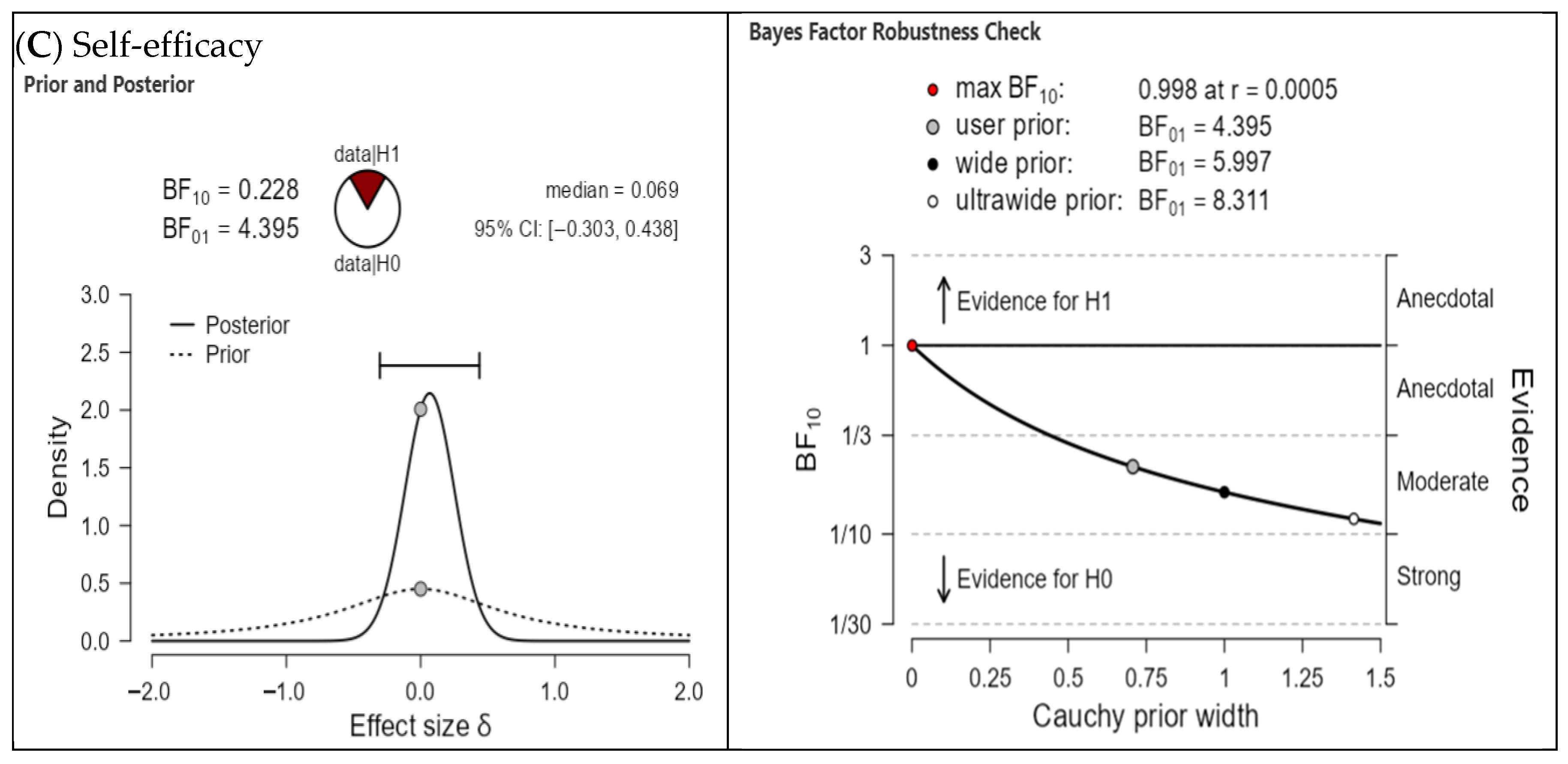

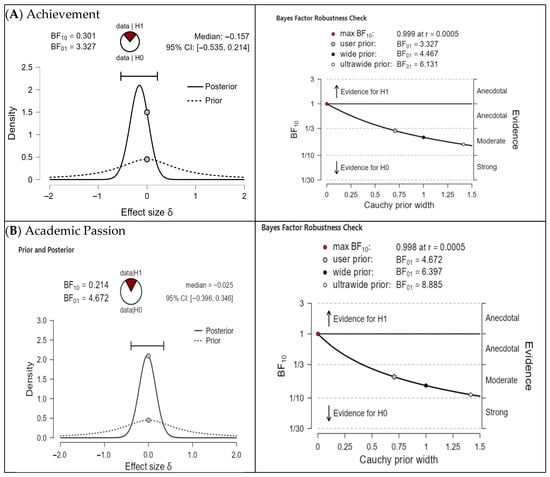

Gender Differences in Post-Test Outcomes

Bayesian independent samples t-tests were conducted to examine potential gender differences in post-test achievement, academic passion, and self-efficacy (H4). As shown in Table 2, the results showed no statistically significant differences between male and female students for any of the outcome variables (Achievement: t(98) = −0.88, p = 0.379; Academic Passion: t(98) = −0.12, p = 0.905; Self-Efficacy: t(98) = 0.39, p = 0.698). Bayes factor analyses (BF10 = 0.214–0.301) provided weak evidence in favor of the null hypothesis, indicating that gender did not significantly influence post-test outcomes. These findings suggest that the intelligent educational system had comparable effects on achievement, motivation, and self-efficacy for both male and female students.

Table 2.

Independent Samples T-Test for Post-Test Achievement, Academic Passion, and Self-Efficacy by Gender.

Furthermore, Prior and Posterior Distributions and Bayes Factor Robustness Checks for Achievement (A), Academic Passion (B), and Self-Efficacy (C) by Gender are presented in Figure 5, illustrating that the Bayesian analyses consistently support the null hypothesis of no gender differences across all outcome measures.

Figure 5.

Prior and Posterior Distributions and Bayes Factor Robustness Checks for Achievement (A), Academic Passion (B), and Self-Efficacy (C) by Gender.

4. Discussion

The present research took into consideration the influence of an intelligent learning system, founded upon the BKT model, on student development in self-efficacy, and enthusiasm for learning in educational technology. The results ascertain substantial correlations between the intelligent learning system and better learner outcomes, as well as the development of adaptive, student-directed learning experiences. The results are aligned with contemporary research on intelligent learning environments [43,44].

The results of the research identified that the BKT model-based intelligent learning environment was instrumental in developing the learning capability of students. With the support of intelligent predictive models, students were able to accomplish several tasks together—such as research, analysis, and project creation. The facility to toggle between tasks with less cognitive interference facilitated more effective development of organizational and time management skills in students. Additionally, the combination of various learning approaches helped learners comprehend their digital competency, hence motivating them to keep developing various types of competencies. The suggested intelligent learning system also enabled learners to handle various tasks at once by constantly modifying the content complexity and teaching pace. The results align with current research quoting that intelligent systems can mitigate cognitive overload in learning situations [45,46,47].

The significant improvement in student skills aligns with existing literature showing that adaptive systems can facilitate higher-order cognitive processes through timely feedback, task segmentation, and navigation across multiple objectives [27,48]. By modeling each student’s knowledge state, the system delivered content tailored to their current level of understanding, reducing cognitive load and enhancing efficiency in performing concurrent tasks. According to Sweller’s Cognitive Load Theory [48], attempting multiple tasks simultaneously can overwhelm novice learners; however, the BKT-based system mitigated this risk by presenting material appropriately aligned with students’ prior knowledge.

The research results also indicated that learners who learned in the intelligent environment modeled after the BKT approach showed a noteworthy improvement in their self-efficacy. This is because the system has the capacity to improve students’ confidence in their learning capacities by offering them learning experiences that match their mastery levels. By providing timely feedback and activities that are most appropriate to the given student’s competence level, students acquired a firm belief in being able to achieve successful learning outcomes.

Furthermore, the findings indicated that the integration of the BKT model within the learning pathways model had a significant influence on the development of students’ self-efficacy. The intelligent environment provided a well-sequenced set of learning obstacles, difficult enough to stimulate improvement yet not so hard that motivation was undermined. This deliberate balance allowed students to develop positive beliefs about their capacities in learning, which eventually led to heightened self-confidence and a better capacity to tackle learning obstacles.

Students also indicated a higher belief in becoming proficient, which they explained through the instant feedback and encouragement offered by the system. These findings support Bandura’s self-efficacy theory [25], as the intelligent learning system facilitated mastery experiences—a key factor in establishing efficacy beliefs [26].

Yet, the enduring sustainability of these self-efficacy gains is an open question. Dabbagh and Kitsantas [49] mention that self-efficacy gains, which are established via technology, may need continuous support and occasional tweaking to maintain cognitive skill enhancement over a prolonged timeframe. The findings also showed a positive effect on academic interest, which implies that the BKT model-based intelligent learning system could have fostered learners’ intrinsic motivation and interest in course content.

Vallerand and Houlfort’s [30] dualistic model of passion would predict harmonious passion to result when students willingly participate in activities that they find meaningful and enjoyable—affect which could have been encouraged by adaptive personalization and the autonomy that it granted. Our findings are consistent with research emphasizing the significance of knowledge tracing in facilitating learning. When students are acquiring multiple objectives, BKT models allow the intelligent system to assess respective competency levels along different learning trajectories and hence make task switches at the appropriate moment and remain cognitively manageable [50,51]. By adjusting task difficulty and pacing according to individual student needs, the system provided cognitive scaffolding that enhanced learning efficiency, consistent with design principles shown to support working memory and learning outcomes [51].

Within the framework of self-efficacy, previous studies have established that knowledge tracing-supported systems deliver precise and timely feedback and therefore reinforce students’ faith in their own abilities [52,53]. As they monitor their own development along stringently defined learning pathways, students develop a sense of confidence in being able to manage and guide their own learning processes—a critical element of self-efficacy as conceptualized by Bandura and Wessels [25].

Computing system experiments—especially in Deep Knowledge Tracing and Bayesian Knowledge Tracing—demonstrate that the models successfully monitor the evolution of knowledge states while facilitating adaptive task sequencing to minimize cognitive load and enhance transitions among learning objectives [54]. This is consistent with our research because the Knowledge Tracing model-based intelligent learning system facilitated learning capacity by adjusting task difficulty and timing.

Knowledge Tracing models give precise estimates of mastery levels, thereby facilitating focused feedback and illuminating student progress [55]. Our findings confirm this observation: students showed increased confidence (self-efficacy) due to identification with personal progress, thereby reiterating key principles from Social Cognitive Theory [25].

Also, passion for learning—particularly consonant passion—is enhanced when students perceive the learning environment as supportive and respectful of their autonomy [30]. Knowledge Tracing makes this possible by promoting a sense of individualized learning advancement, in which students are neither alienated by overly simplistic exercises nor discouraged by overly demanding ones. Such “optimal challenge” promotes continuous participation and enjoyment in the learning process [56].

Despite these positive findings, some studies offer a more intricate—and sometimes even critical—perspective on Knowledge Tracing models. Critics suggest that most Knowledge Tracing models, especially early ones like BKT, rely on a binary division of mastery states (learned or not learned) and exclude the intricate aspects of the learning process, such as motivational and affective components [48,57]. Such a shortage can result in inaccurate modeling of student behavior, particularly in complicated tasks involving advanced cognitive abilities and multiple simultaneous operations. Additionally, students’ socioeconomic and personal backgrounds, such as family support, pre-entry skills, and residential context, can further influence learning outcomes, suggesting that adaptive learning systems may interact differently with learners depending on these factors [58,59].

Poor interpretability: Despite being very predictive, deep learning-based Knowledge Tracing models such as Deep Knowledge Tracing (DKT) are frequently criticized for poor interpretability. This may make it difficult for teachers and learners to discern the reasoning behind specific feedback or recommendations given [60]. Such a lack of transparency can decrease learners’ trust in the system, potentially lowering their motivation and sense of control.

While Knowledge Tracing models are demonstrated to work well for modeling cognitive mastery, they do not incorporate aspects such as academic passion, which is shaped by social interactions, personal values, and affective experiences [61]. Purely Knowledge Tracing-based models can neglect to comprehensively address these multifaceted motivational determinants.

Empirical research on the effectiveness of Knowledge Tracing model-based intelligent learning systems is sparse and presents a mixed set of findings. Whereas on the one hand, Wu et al. [62] established that advanced e-learning technologies can have a positive impact on the learning and development of students, the findings’ implications are that intelligent learning systems are an effective pedagogy since they possess the potential to seek the attention of learners and increase their participation in learning processes [63].

However, a significant shortage of studies is noticeable since the majority of existing research has focused on particular cultural settings, whereas investigations into the generalizability of Knowledge Tracing model-based intelligent learning systems across different cultural settings remain insufficient [64].

This gap in research is partly attributed to differing notions of education and varied learning approaches between cultures, where more research is needed to examine the effectiveness of these systems in multicultural learning contexts. In conclusion, the implementation of Knowledge Tracing models in intelligent tutoring systems is strongly correlated with research in favor of individualized learning, sophisticated learning capability, and high learner confidence levels. But the inability to model emotional and motivational variables and system decision-making transparency are areas of concern that future research must focus on for the sake of holistic student development.

Overall, the findings suggest a robust and positive association between the use of intelligent learning systems and improvements in academic achievement, self-efficacy, and academic passion. The integration of AI-driven adaptive technologies in education demonstrates promise not only for improving academic outcomes but also for supporting psychological and motivational factors critical for sustained learning [65,66,67,68].

5. Limitations

This study employed a quasi-experimental, single-group pre-test/post-test design, which precludes causal conclusions. However, the observed improvements in academic achievement, self-efficacy, and academic passion should be interpreted cautiously, as they may be affected by factors such as instructional quality, natural learning progression, expectancy bias, or the Hawthorne effect—particularly in technology-enhanced learning environments where novelty and increased attention may temporarily enhance engagement. Additionally, the 40% sample attrition (from 167 to 100 participants) may have introduced selection bias, potentially affecting internal validity. In addition, as all participants were enrolled in a single course taught by the same instructor, multilevel modeling was not required. However, this may limit the generalizability of findings to other courses or instructors.

A further limitation is the relatively small sample size, restricted to a specific group of Educational Technology students. Nevertheless, these findings provide preliminary evidence of a potential positive association between the use of the IES and student outcomes. Future research should involve larger and more diverse samples, as well as randomized controlled trials, to enhance generalizability and more rigorously evaluate the effects of the Intelligent Learning System on academic achievement, self-efficacy, and academic passion. While the statistical analysis includes Bonferroni correction and robust reporting of effect sizes (eta and Cohen’s d with confidence intervals), the study size limits advanced mediation analyses. Additionally, the lack of variability in KT feedback restricts some interpretations. Future research should employ randomized designs, larger and more diverse samples, and variation in intervention dosage to better isolate causal effects. Although the adaptations of the instruments are detailed, future research could incorporate measurement invariance testing pre- and post-intervention to further strengthen the psychometric evaluation. Furthermore, future studies should incorporate advanced item-scaling methods, such as Mokken Scale Analysis and network analysis, to better assess mastery levels [69].

6. Conclusions

This research illustrates that the incorporation of an intelligent learning system derived from the Knowledge Tracing model greatly improves the intellectual achievement, self-efficacy, and academic motivation of students through adaptive and personalized learning experiences that are consistent with their individual knowledge levels.

The predictive capacity of the system enabled efficient task handling, developed learners’ self-efficacy, and maintained motivation by providing immediate feedback and adaptively challenging experiences. These results are consistent with current literature on the cognitive and motivational advantages of intelligent environments, but certain limitations—such as unrealistically naïve assumptions of mastery and reduced model interpretability—also point to those areas in need of development. Although results foster the pedagogical potential of these systems, future research ought to analyze their cultural suitability and consider the emotional and relational dimensions of learning for a more comprehensive educational effect.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R.A. and S.Y.S.; methodology, M.R.A. and G.S.M.A.; software, M.R.A.; validation, G.S.M.A.; formal analysis, G.S.M.A.; investigation, M.R.A. and G.S.M.A.; resources, M.R.A., S.Y.S. and R.M.K.; data curation, S.Y.S. and R.M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R.A. and G.S.M.A.; writing—review and editing, S.Y.S., R.M.K., M.R.A. and G.S.M.A.; visualization, G.S.M.A. and M.R.A.; supervision, M.R.A.; project administration, M.R.A.; funding acquisition, S.Y.S. and R.M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Fayoum and complied with its guidelines.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all students involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, H.; Wu, Q.; Bao, C.; Ji, W.; Zhou, G. Research on knowledge tracing based on learner fatigue state. Complex Intell. Syst. 2025, 11, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanLehn, K. The relative effectiveness of human tutoring, intelligent tutoring systems, and other tutoring systems. Educ. Psychol. 2011, 46, 197–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerimbayev, N.; Adamova, K.; Shadiev, R.; Altinay, Z. Intelligent educational technologies in individual learning: A systematic literature review. Smart Learn. Environ. 2025, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troussas, C.; Krouska, A.; Sgouropoulou, C. Learner Modeling and Analysis. In Human-Computer Interaction and Augmented Intelligence: The Paradigm of Interactive Machine Learning in Educational Software; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 305–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.R. Cognitive Modelling and Intelligent Tutoring; National Science Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 1986.

- Anderson, J.R.; Boyle, C.F.; Corbett, A.T.; Lewis, M.W. Cognitive modeling and intelligent tutoring. Artif. Intell. 1990, 42, 7–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Yu, D. Towards intelligent E-learning systems. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 7845–7876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Shi, X.; King, I.; Yeung, D.Y. Dynamic key-value memory networks for knowledge tracing. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on World Wide Web, Perth, Australia, 3–7 April 2017; pp. 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Heffernan, N.; Lan, A.S. Context-aware attentive knowledge tracing. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, San Diego, CA, USA, 23–27 August 2020; pp. 2330–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labra, C.; Santos, O.C. Exploring cognitive models to augment explainability in Deep Knowledge Tracing. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM Conference on User Modeling, Adaptation and Personalization, Limassol, Cyprus, 26–29 June 2023; pp. 220–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Liu, Q.; Huang, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Yin, M.; Wang, M.; Chen, E. A survey of knowledge tracing: Models, variants, and applications. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol. 2024, 17, 1858–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, A.T.; Anderson, J.R. Knowledge tracing: Modeling the acquisition of procedural knowledge. User Model. User-Adapt. Interact. 1994, 4, 253–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piech, C.; Bassen, J.; Huang, J.; Ganguli, S.; Sahami, M.; Guibas, L.J.; Sohl-Dickstein, J. Deep Knowledge Tracing. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 28; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 505–513. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Tong, L.; Cheng, Y. Advanced Knowledge Tracing: Incorporating Process Data and Curricula Information via an Attention-Based Framework for Accuracy and Interpretability. J. Educ. Data Min. 2024, 16, 58–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junco, R.; Cotten, S.R. No A 4 U: The relationship between multitasking and academic performance. Comput. Educ. 2012, 59, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouelenein, Y.A.M.; Selim, S.A.S.; Aldosemani, T.I. Impact of an adaptive environment based on learning analytics on pre-service science teacher behavior and self-regulation. Smart Learn. Environ. 2025, 12, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Mohd Rum, S.N.; Kasmiran, K.A.; Aris, T.N.M.; Mohamed, R. Artificial intelligence in adaptive and intelligent educational systems: A review. Future Internet 2022, 14, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-Y.; Saeedvand, S.; Lai, I.-W. Adaptive learning path navigation based on knowledge tracing and reinforcement learning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.04475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, I.; Warren, S.; Norris, C.; Soloway, E. Leveraging opportunities for self-regulated learning in smart learning environments. Smart Learn. Environ. 2025, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sabagh, H.A. Adaptive e-learning environment based on learning styles and its impact on students’ engagement. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2021, 18, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, J.; Dignath, D.; Lukas, S. Positive and negative action-effects improve task-switching performance. Acta Psychol. 2021, 221, 103440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D.H.; Pajares, F. Self-Efficacy Theory. In Handbook of Motivation at School; Routledge: Milton Park, UK, 2009; pp. 49–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Liu, Z.; Huang, S.; Liu, Q.; Luo, W. Self-determination theory and the influence of social support, self-regulated learning, and flow experience on student learning engagement in self-directed e-learning. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1545980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Wessels, S. Self-Efficacy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997; pp. 4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, B.J. Self-efficacy: An essential motive to learn. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleven, V.; McLaughlin, E.A.; Glenn, R.A.; Koedinger, K.R. Instruction based on adaptive learning technologies. In Handbook of Research on Learning and Instruction, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 522–560. [Google Scholar]

- Fredricks, J.A.; Blumenfeld, P.C.; Paris, A.H. School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Rev. Educ. Res. 2004, 74, 59–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerand, R.J.; Houlfort, N. Passion at work: Toward a new conceptualization. In Emerging Perspectives on Values in Organizations; Emerald Group Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2003; pp. 175–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffernan, N.T.; Heffernan, C.L. The ASSISTments ecosystem: Building a platform that brings scientists and teachers together for minimally invasive research on human learning and teaching. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2014, 24, 470–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lu, B. Intelligent educational systems based on adaptive learning algorithms and multimodal behavior modeling. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2025, 11, e3157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Guo, T.; Liang, Q.; Hou, M.; Zhan, B.; Tang, J.; Luo, W.; Weng, J. Deep learning based knowledge tracing: A review, a tool and empirical studies. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2025, 37, 4512–4536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.; Hung, J.; Du, X.; Tang, H.; Li, H. Knowledge Tracing: A Review of Available Techniques. J. Educ. Technol. Dev. Exch. 2021, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z. Integrating Reinforcement Learning with Dynamic Knowledge Tracing for personalized learning path optimization. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 40202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.; Shaalan, K.; Saeed, A.Q.; Elnekiti, A.; Alhyari, O.; Yousuf, H.; Ghazal, T.M. Emotion-Aware Course Personalization in Virtual Classrooms via Multi-Modal Fusion Learning Systems. In Proceedings of the 2025 3rd International Conference on Cyber Resilience (ICCR); IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Tian, M.; Luo, W. Rethinking and Improving Student Learning and Forgetting Processes for Attention based Knowledge Tracing Models. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2025, 39, 27822–27830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Xu, L. Deep Graph Knowledge Tracing with Multi-head Self-attention and Forgetting Mechanism. In Neural Information Processing. ICONIP 2025; Taniguchi, T., Leung, C.S.A., Kozuno, T., Yoshimoto, J., Mahmud, M., Doborjeh, M., Doya, K., Eds.; Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer: Singapore, 2026; Volume 2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R.; Jerusalem, M. Generalized Self-Efficacy scale. In Measures in Health Psychology: A User’s Portfolio. CAUSAL and Control Beliefs; Weinman, J., Wright, S., Johnston, M., Eds.; NFER-NELSON: Slough, UK, 1995; pp. 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Vallerand, R.J.; Blanchard, C.; Mageau, G.A.; Koestner, R.; Ratelle, C.; Léonard, M.; Gagné, M.; Marsolais, J. Les passions de l’âme: On obsessive and harmonious passion. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 756–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 30.0. [Computer software]. IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2023.

- JASP Team. JASP, version 0.18.2. [Computer software]. JASP Team: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2023. Available online: https://jasp-stats.org/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Tuo, P.; Bicakci, M.; Ziegler, A.; Zhang, B. Measuring Personalized Learning in the Smart Classroom Learning Environment: Development and Validation of an Instrument. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, I.; Semenov, A.L.; Gorsky, M. Smart Learning in the 21st Century: Advancing Constructionism Across Three Digital Epochs. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Li, X.; Wang, P.; Tang, J.; Wang, T. Integrating fine-grained attention into multi-task learning for knowledge tracing. World Wide Web 2023, 26, 3347–3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.; Kim, J.; Kim, M.; Park, J. No task left behind: Multi-task learning of knowledge tracing and option tracing for better student assessment. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Online, 22 February–1 March 2022; Volume 36, pp. 4424–4431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumsvik, R.J. Smartphones, media multitasking and cognitive overload. Nord. J. Digit. Lit. 2025, 20, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koedinger, K.R.; Booth, J.L.; Klahr, D. Instructional complexity and the science to constrain it. Science 2013, 342, 935–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J. Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cogn. Sci. 1988, 12, 257–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabbagh, N.; Kitsantas, A. Personal Learning Environments, social media, and self-regulated learning: A natural formula for connecting formal and informal learning. Internet High. Educ. 2012, 15, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaban, A.; Chang, V.; Amodu, O.D.; Attia, M.R.; Abdelhamid, G.S.M. A Systematic Review of Working Memory Applications for Children with Learning Difficulties: Transfer Outcomes and Design Principles. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Zhao, S.; Van Inwegen, E.; Beck, J. Going deeper with deep knowledge tracing. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Educational Data Mining (EDM), Raleigh, CA, USA, 29 June–2 July 2016; pp. 545–550. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED592679 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Gutierrez, R.; Villegas-Ch, W.; Navarro, A.M.; Luján-Mora, S. Optimizing Problem-Solving in Technical Education: An Adaptive Learning System Based on Artificial Intelligence. IEEE Access 2025, 3, 61350–61367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsey, R.V.; Shroyer, J.D.; Pashler, H.; Mozer, M.C. Improving students’ long-term knowledge retention through personalized review. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 25, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thai-Nghe, N.; Drumond, L.; Horváth, T.; Krohn-Grimberghe, A.; Nanopoulos, A.; Schmidt-Thieme, L. Factorization techniques for predicting student performance. In Educational Recommender Systems and Technologies: Practices and Challenges; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2012; pp. 129–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Hou, Y.; Zeng, C.; Zhang, S.; Ye, R. Multiple learning features–enhanced knowledge tracing based on learner–resource response channels. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, T. Intelligent Tutoring Systems in Mathematics Education: A Systematic Literature Review Using the Substitution, Augmentation, Modification, Redefinition Model. Computers 2024, 13, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatiry, A.R.; Abdallah, S.E. The successful transition to university: Socioeconomic and personal determinants affecting first-year undergraduates. J. Soc. Stud. Educ. Res. 2023, 14, 132–156. Available online: https://jsser.org/index.php/jsser/article/view/5382 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Alkathiri, M.S.; Alrayes, N.S.; Khatiry, A.R. Examining leadership competencies of first-year undergraduates: The mediation and moderation effects of gender and academic disciplines. J. Soc. Stud. Educ. Res. 2024, 15, 146–172. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Brunskill, E. The impact on individualizing student models on necessary practice opportunities. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Educational Data Mining (EDM), Chania, Greece, 19– 21 June 2012; pp. 118–125. [Google Scholar]

- Yudelson, M.V.; Koedinger, K.R.; Gordon, G.J. Individualized Bayesian knowledge tracing models. In Artificial Intelligence in Education, Proceedings of the 16th International Conference, AIED 2013, Memphis, TN, USA, 9–13 July 2013; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Li, J.; Cai, T.; Yang, S.; Yang, T.; Liu, C. A survey on deep learning based knowledge tracing. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 258, 110036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Liao, W.; Wang, X. Collaborative Learning Groupings Incorporating Deep Knowledge Tracing Optimization Strategies. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.H.; Chen, Y.S.; Chen, T.G. An adaptive e-learning system for enhancing learning performance: Based on dynamic scaffolding theory. EURASIA J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2017, 14, 903–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Halim, H.B.A.; Saad, M.R.B.M. Leveraging AI-enabled mobile learning platforms to enhance the effectiveness of English teaching in universities. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Xu, W.; Liu, R. Effects of intelligent tutoring systems on educational outcomes: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Distance Educ. Technol. 2025, 23, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hamid, H.A.; Bao, X. Motivation and achievement in EFL: The power of instructional approach. Front. Educ. 2025, 10, 1614388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, M.; Ewees, H.; Khatiry, A. Using artificial intelligence in educational research: The competencies of researchers. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhamid, G.S.M.; Hidalgo, M.D.; French, B.F.; Gómez-Benito, J. Partitioning Dichotomous Items Using Mokken Scale Analysis, Exploratory Graph Analysis and Parallel Analysis: A Monte Carlo Simulation. Methodology 2024, 20, e12503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.