Abstract

Knowledge discovery helps mitigate the shortcomings of classical machine learning, especially those so-called imbalanced, high-dimensional, and noisy data challenges. Adaptive combination of multiple models, voting and other data fusion strategies, and the incorporation of other disparate information fusion methods characterize ensemble learning, which addresses the improvement of a predictive model’s accuracy, stability, and generalization. This paper provides a summary of the important approaches to ensemble learning and their real-world uses, emphasizing challenges and opportunities for future work. This paper also discusses how ensemble learning integrates with emergent areas such as deep learning and reinforcement learning. This paper also describes the most important machine learning methods for predicting heart disease, which include decision trees, support vector machines, artificial neural networks, Naïve Bayes, random forest, and K-nearest neighbors.

1. Introduction

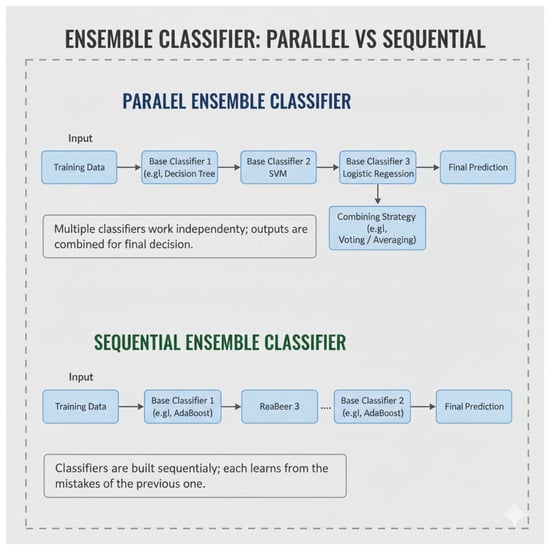

As per the World Health Organization (WHO), cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are now the leading cause of mortality worldwide. Among them, coronary heart disease tends to be a major health issue worldwide, with early detection and intervention crucial to limiting the progression of disease and improving patient outcomes, especially as CVDs are still the highest global contributors to increased mortality [1]. The concept of ensemble learning was first introduced by Hansen in 1990 [2] and has since been an important strength of machine learning. An approach that relies on various classifiers to create stronger classifiers is ensemble learning, which possibly uses techniques such as majority voting or aggregate predictions. Studies have almost uniformly shown that ensemble classifiers outperform single classifiers with respect to accuracy and reliability. All members of the ensemble are the same concerning the base algorithm or learner: structural relations among such members may differ. A heterogeneous–homogeneous ensemble proposes to partition the data into small subsets to develop each subset with one of the algorithms that can be used for classification, regression, etc. The proposed approach uses the mean-based strategy for combined predictions and has been proven to enhance predictive performance [3], as illustrated in Figure 1. There is a large number of innovative fields that machine learning (ML) could be applied to, and there is still room for novel advancements that can further improve effectiveness and accuracy for each of them. For example, ensemble learning might broaden the capabilities of individual models and is, in that sense, a powerful approach for constructing more productive diagnostic systems for complicated health issues. Classifier systems that use ensemble learning and different algorithms have better prediction performance in, and this is especially important in the early diagnosis and detection of heart diseases [4].

Figure 1.

General framework of homogeneous and heterogeneous ensemble (Note: Figure 1 created by the authors based on concepts discussed in [5]).

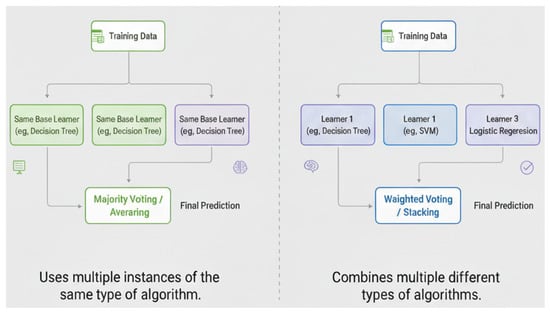

The sequential training of base learners fosters dependency on some of the weak learners. The model’s overall performance is then improved by assigning higher weights to previously misclassified instances (or samples). Parallel ensemble approaches generate base newbies in a parallel style. The difference between sequential and parallel ensemble classifiers is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Parallel and sequential ensemble classifier ensemble. ((left): homogeneous; (right): heterogeneous) (Note: Figure 2 created by the authors based on concepts discussed in [5]).

It is important to note that this article is a survey and does not propose or evaluate any new ML model. All analyses, discussions, and comparative insights are derived entirely from previously published studies. This article aims to provide an up-to-date overview of ensemble learning methods used for detecting heart disease and to outline unanswered questions related to data, model building, and real-world clinical use. The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 describes the literature review; Section 3 presents the search criteria, inclusion and exclusion methodology; Section 4 is the discussion; Section 5 presents the comparative analysis; Section 6 presents the open challenges in ML, DL, and ensemble learning for CVD prediction; Section 7 presents limitations; Section 8 is dedicated to future work; and Section 9 presents the conclusions.

2. Literature Review

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) continues to be the foremost global cause of death; here are some of the ways ML is improving the early detection of cardiovascular diseases. Ensemble learning methods are particularly popular as they are proven to surpass single classifiers in robustness, stability, and accuracy. Recent implementations of stacking, boosting, and bagging as well as hybrid voting combinations of decision trees, random forests, SVMs, and shallow neural networks in ensemble frameworks demonstrate the algorithms’ superiority over individual models across a variety of structured clinical datasets (e.g., UCI Heart, multi-center clinical registries), AUC, accuracy, and other performance metrics, particularly in noisy or imbalanced scenarios [6,7,8]. A growing trend involves the use of explainable AI (XAI) in ensemble models to provide pre-defined transparency around specific metrics and clinical interpretability vital to the decision-making process with the aid of accuracy-preserving SHAP importance aggregation and rule extraction from tree ensembles, thus boosting clinician confidence [6,8,9]. In cardiology, working with multimodal datasets (EHR, ECG, and imaging) has led to the creation of new hybrid models utilizing deep-learning feature extractors and classical ensemble meta-learners. These help psychologize the models, and maintaining performance helps optimize for explainability [6,8,10]. Lastly, the more recent developments on lightly compressed ensemble architectures, as stated [10], allow for deployment with certain eco-diagnostic constraints and for edge or point-of-care use. However, challenges on generalizability, calibration, and fairness remain, particularly with multi-site data. Several reviews called for direct external validation, multi-center testing, and more systematic frameworks on decision-curve and calibration analyses to clinically justify these works [8,11,12]. Additionally, the 2024 literature on ensemble methods that layer cost-sensitive learning, SMOTE-like methods, focal losses, and federated learning for imbalanced and distributed datasets revealed hyperparameter tuning on stacking models for precision and reliability on varying populations [11,13,14]. Other studies showcased multimodal fusion and privacy-aware ensemble frameworks as innovative approaches to resolve data heterogeneity and bias issues in cardiovascular diagnosis [15].

A functional appraisal through many machine-learning algorithms is carried out by different medical institutions across the world. To predict the consequences of hybrid diseases like heart disease, ref. [16] proposed a stacking ensemble-based ML model. Patients of different ages with hybrid disease were studied, and a number of determinants for CVD were evaluated. This was also considered in the context of hybrid diseases with artificial intelligence and ML, where the authors of ref. [17] looked into the viability of machine-learning classifiers and ensemble methods to diagnose Parkinson’s disease. Comparative performance of various algorithms and ensemble methods, including logistic regression, k-nearest neighbors, support vector classifiers, gradient boosting classifiers, and random forest classifiers, was carried out in this investigation. Clinical outcome assessments can thus be predicted reliably by ML for people with Parkinson’s disease. It also stresses the importance of feature selection as well as the relevance of Pearson correlated features in diagnosis. An ensemble framework to apply ML algorithms for predicting CVD is given by ref. [18]. The system is characterized by model selection, parameter configuration, and experimental setup and has yielded significant improvements compared with earlier published works in these areas. Various criteria are used to measure the efficiency of the framework, and the performance is compared against other competing models. The authors propose that it can positively impact healthcare, especially in third-world countries. Further work is needed to study the application of deep learning (DL) paradigms to increasingly larger datasets.

This paper also provides a list of references to consult for more information on the prediction of CVD by ensemble learning and machine learning. In the text identified in reference [19], the authors introduced ensemble learning as a way to improve upon the results of ML by using multiple models simultaneously for decision making. The introduction covers the various ensemble methods and their domain-specific applications, examples of difficulties encountered in their implementation, and areas that could use further research. An interface will be made between ensemble learning and other methods of ML such as DL and reinforcement learning. Ref. [20] discusses the use of ensemble learning techniques to forecast cardiac ailments better.

In this paper, measures such as accuracy, recall, precision, F-measure, and ROC have been used to assess the performance of various ML algorithms and ensemble learning techniques. The results show that the best performance is obtained using a decision tree in conjunction with the bagging ensemble learning technique. The significance of ML in the prediction of cardiovascular diseases and its potential to better diagnose and treat such diseases in the future is emphasized in this paper. An ensemble model was implemented for predicting cardiovascular disease. Several supervised ML models were involved, and ensemble models were formed through the different techniques of voting and averaging. The result showed a better performance of the ensemble-built models when compared with standalone models. It emphasizes the importance of testing and detection of cardiovascular diseases in the early period. An MPBE (Multiple Parallel Base Estimators) Bagging ensemble technique was suggested by ref. [12] to forecast when an individual might develop heart disease. Multiple base classifiers were combined with preprocessing, feature selection, and cross-validation within the k-fold to maximize precision. The model thus developed achieved a classification accuracy of 95.33%, which was far better than that of other algorithms and ensemble techniques.

A smart system based on an ensemble classifier offered by ref. [13] has been developed for the purpose of predicting cardiovascular disease. This research evaluated several classification algorithms to predict the recurrence of heart disease. Based on the experimental data collected, the ensemble model technique gives very high predictive accuracy and reliability. Thus, early detection of cardiac disease can eventually cut down on treatment costs through this proposed technology. In the current study, authored by ref. [14], cross-domain sentiment analysis using supervised ML and feature stabilization through an ensemble strategy is proposed. Various feature selection techniques are also analyzed by the authors on their performance when applied to three standard datasets available in the industry. Similarly, evaluation metrics were applied to compare the performance of four different classification models built. The results achieved in the proposed method are highly accurate and hence can be compared well with previously conducted studies in the same field. Ref. [15] offered an ensemble approach that was inexpensive for CVD forecasting. This includes five dissimilar classifiers in increasing productivity and avoiding unnecessary costs resulting from misclassification. Its proposed ensemble is a potential model for accurate cardiac disease diagnosis when compared to individual classifiers and other works based on mixing classification methods.

Ref. [21] examined the applicability of the different techniques under ML to the problem of predicting coronary heart disease. It introduces CVD and its risk factors, states present systems of illness prediction and discusses many ML algorithms based on their attributes and accuracy. The final aim is to develop a highly precise algorithm, which can then be used for easy diagnosis purposes for cardiac issues by medical professionals. Ref. [22] proposed various ML techniques of diagnosis in diabetes and also mentions how ensemble learning can be beneficial for improving prediction accuracy. Healthcare methods and illness prevention using IoT and other intelligent systems have also been discussed. Ref. [23] provided a hybrid approach for the diagnosis of cardiovascular diseases, which is based on an ensemble classifier model that uses feature selection. The method is by means of genetic algorithms, with ensemble learning to get the most informative features from the dataset and improve diagnostic accuracy. It is found from the evaluation that the proposed model shows the largest difference from conventional techniques with an accuracy of 97.57 percent on the datasets considered. This paper attests the credibility of ML in contributing to the advancement in the diagnosis and prognosis of heart disease.

Ref. [24] discussed the usage of ML methods in echocardiography for the screening and diagnosis of coronary heart disease. The scheme investigates an innovative ensemble ML method that integrates classifiers in order to improve CHD diagnosis precision by using 2D speckle tracking echocardiography (2D-STE) for extracting relevant characteristics of myocardial function, which in turn is used for conducting principal component analysis (PCA) for dimensionality reduction in the feature space. The proposed method was shown to be more efficient than any other known method for the detection of coronary heart disease (CHD) and presents opportunities for improving CHD screening and diagnosis with the least invasiveness.

An ML model has been designed to predict CVD, with effective data collection, preprocessing, and transformation techniques being carried out. The developed model engages feature selection methods, using various methods, such as decision tree, random forest, support vector machine (SVM), and K-nearest neighbors (KNN), to evaluate performance. The study also looks at ensemble methods and deep neural networks. Ref. [25] examined a machine-learning model that uses ensemble methods and hyperparameter tuning for heart disease prediction. The study emphasizes the ability of the model to predict heart disease, thus enabling early intervention, detection, and management.

Ref. [26] describes an innovative approach incorporating genetic algorithm (GA) and particle swarm optimization (PSO) techniques into the architecture of random forest (RF) to predict cardiac diseases. To realize better classification accuracy, the focus is on further improving the mechanism of the feature selection process. The proposed method was evaluated on the basis of two datasets and found to yield impressive prediction accuracy. The study reported in ref. [27] applied weighted associative rule mining for finding significant feature scores and rules in the diagnosis of heart disease. Investigations carried out on a dataset that is widely used have given a very high confidence score of 98% in respect of heart disease prediction. Thus, this work is important in heart disease prediction in determining the strength scores of major predictors using a computational approach.

In ref. [28], a novel cost-sensitive ensemble approach was proposed for heart disease prediction. This approach integrates five classifier types to make them more effective toward prevailing classifier models and resolving potential challenges arising from misclassification. The combined approach is an improvement over separate models and prior results and opens a promising avenue in the field of heart disease diagnosis. In a remarkable study, Heidari et al. [29] developed an intelligent medical system that employed ML algorithms to identify people suffering from cardiac problems accurately. It is demonstrated in the results that, due to better accuracy, the proposed model is superior to other models in heart disease diagnosis. Their paper also describes the significance of feature selection and how ML could ease the diagnosis of heart disease [30]. They applied ensemble methods, voting and stacking to enhance heart disease prediction. Experiments were performed on several datasets, and both ensemble models were able to outperform standalone models, with stacking providing the best accuracy. Improved performance is attributed to successful model selection, meta learning, cross-validation, and hyper-parameter tuning. These observations point to the ability of the ensemble methods to support clinical deaccessioning [22].

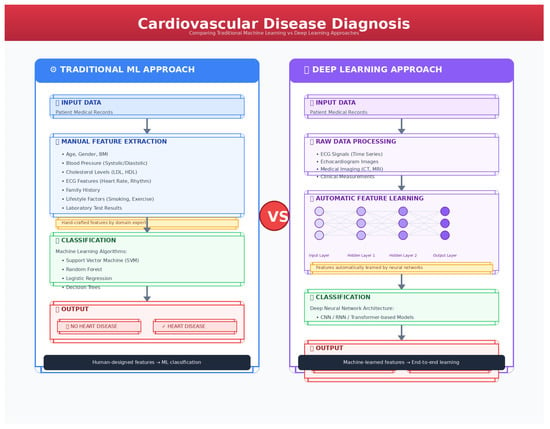

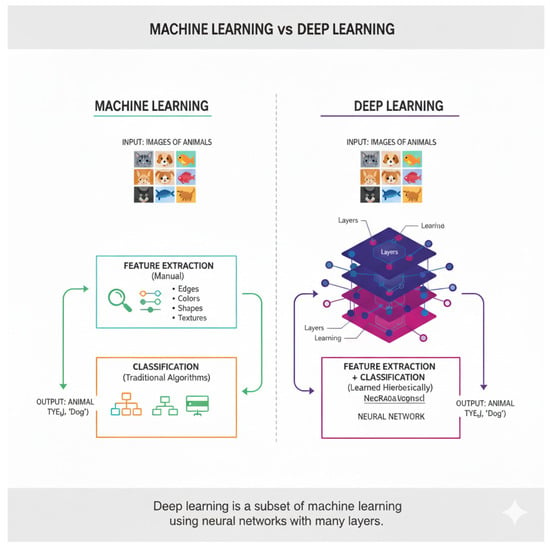

In an actual study, Inception Networks and other applied ML models were used in classifying cardiovascular diseases based on UCI datasets with features indistinctly rated as high as 98.89% accuracy. Age, cholesterol, blood pressure, and gender were discovered to be the most important factors in disease presence. Limitations like using a single dataset and few clinical variables indicate a need for more extended features and a diversity of optimization strategies in future studies. This literature review, by ref. [15], is on ML and DL methods for heart disorders. It is devoted to methods, datasets, pros, and cons of research in this field, as shown in Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5. According to the literature review, ML and DL have promise in enhancing diagnosis and prognosis for heart disorders. The comparison details of some related works are tabulated in Table 1 and Table 2.

Figure 3.

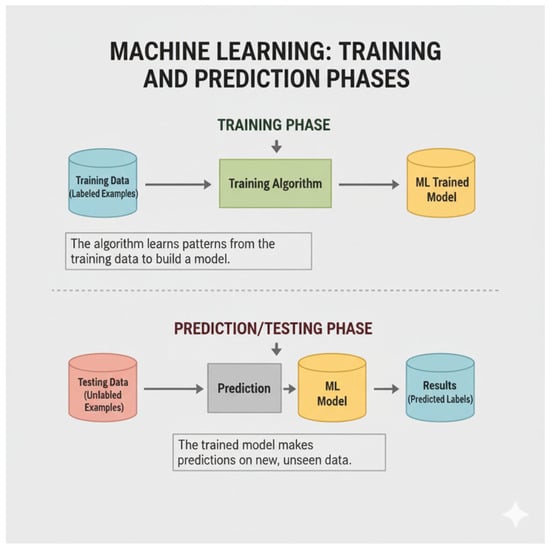

Machine learning vs. deep learning process.

Figure 4.

Machine-learning and DL with many layers.

Figure 5.

Machine-learning process for step-by-step analysis [21].

Table 1.

Comparison of ML, DL and ensemble algorithms.

Table 2.

Comparison of databases used along with accuracy.

Figure 5 shows an image illustrating the concepts of training data, training a model, and then using that model for prediction with testing data:

A comparison of the different ML algorithms used in the prediction of heart disease is shown in Table 3 and Table 4. Important details from pertinent research papers are compiled in Table 3, including the dataset used, the algorithm used, the year of publication, and the author or authors. Table 4 presents a comparison along with findings by focusing on accuracy and other required details.

Table 3.

Comparison of articles with ML algorithm.

Table 4.

Database search strategy and results summary.

3. Methodology

For better results, voting mechanisms and the combinations of various predication algorithms have been used. The combination of various ML algorithms can provide an understanding and comparison of the KNN, ANN < SVM and decision trees. The results and understanding can also help these algorithm’s capability in the prediction of cardiovascular disease. Various studies have presented the potential of these algorithms to predict various problems such as noise, data imbalance and high dimensionality. The paper also analyzes a relationship between ensemble learning and other advanced ML techniques, including DL and reinforcement learning, highlighting some of its major challenges and research objectives with respect to real datasets. The systems of methodology cover the interaction of different models for achieving more robust and accurate predictions. It also covers techniques in preprocessing data to address noisy or incomplete data such that an optimal solution can be achieved over a wide range of conditions. The research emphasizes the importance of data fusion and mining in establishing patterns sometimes not established by single models. Overall, the approach considers the various ensemble learning techniques to arrive at the most suitable method for predicting the complex condition of heart ailments.

What follows are the different databases investigated: IEEE Xplore, PubMed, and Scopus. Also included are search strategy keywords and Boolean operators, as well as a description of the considered time period for the selection of relevant studies, and the inclusion and exclusion criteria that were applied to streamline the selection of sources.

3.1. Search Strategy

A systematic search strategy was adopted to identify relevant studies on CVD prediction using machine learning, deep learning, and ensemble learning techniques. Three major scientific databases were used for this review: IEEE Xplore, PubMed, and Scopus. The search was conducted between January 2018 and January 2025 to ensure inclusion of the most recent advances in medical AI and ensemble modeling.

To retrieve relevant publications, combinations of controlled vocabulary terms and free-text keywords were employed. Boolean operators (AND, OR), phrase matching, and truncation symbols were applied depending on the requirements of each database. The primary search strings included “ensemble learning for CVD detection”, “Heart disease prediction machine learning”, “CVD diagnosis using deep learning”, “hybrid machine learning models for cardiac disease”, “stacking OR bagging OR boosting for heart disease”, “medical diagnosis ensemble classifier”, “machine learning clinical datasets CVD”, “ECG-based deep learning heart disease prediction”, “CVD prediction using multimodal data”.

Boolean combinations used included examples such as “cardiovascular disease” AND “ensemble learning”, “heart disease prediction” AND (“stacking” OR “bagging” OR “boosting”) “ECG” AND “deep learning” AND “classification”, “hybrid model” AND “CVD diagnosis” AND “machine learning”, Search filters were applied to limit results to peer-reviewed journal articles, conference proceedings, full-text English publications, studies involving human cardiovascular datasets, and studies implementing ML, DL, or ensemble techniques.

Duplicate records were removed, and the remaining studies were screened according to predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Titles, abstracts, and full texts were reviewed to ensure alignment with the scope of the study, such as the use of ensemble or advanced ML models, relevance to CVD diagnosis, and availability of performance metrics.

This structured and well-defined search strategy ensured comprehensive coverage of existing CVD prediction research while maintaining methodological transparency and reproducibility.

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The selection of studies for this review followed a structured screening protocol to ensure that only relevant, high-quality research aligned with the aims of the survey was included. The following inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied during the screening process:

3.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

The inclusion of the studies was based on the conditions that the studies focus on cardiovascular disease, detection, diagnosis, prediction, prevention and risk classification. The studies were included if they employed DL, ML and ensemble learning, namely hybrid framework, multi-model AI, boosting, bagging and other related algorithms. The research studies were published between the years of 2018 and 2025, covering the recent advancements of AI in the medical field. The papers were published by reputable scientific venues, as defined in Table 4. Those studies and articles included clinical, ECG, demographic or multimodal medical datasets related to CVD. The performance metrics were also considered for the inclusion, including AUC, accuracy, precision, F1-score, recall and other matching evaluation measures. Only English language articles were included in the study.

3.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

Studies were excluded if they met the various criteria such as articles that were not related to the CVD, or involving ensemble, ML or DL methods. The review articles, short communications, editorials, opinion papers, book chapters and non-peered reviews were also excluded from the current study. Some other studies were also excluded from the study, lacking in experiment validation and conceptual models without empirical evaluations. The papers were also excluded if they were written in a language other than English or the full text was not accessible. These criteria ensured that only methodologically sound and directly relevant studies were included in the final analysis.

3.3. Data Extraction and Screening Process

To ensure the rigor of our methodology and the consistency of our study selection, a well-structured, screening and data extraction process was followed comprising a three-step screening. The first step was the initial search strategy and the removal of duplicate studies that were retrieved from various online sources, such as Scopus, PubMed, IEEE Xplore to reference managers. Duplicate titles and overlapping entries across databases were automatically and manually removed. This produced the initial unique dataset for screening.

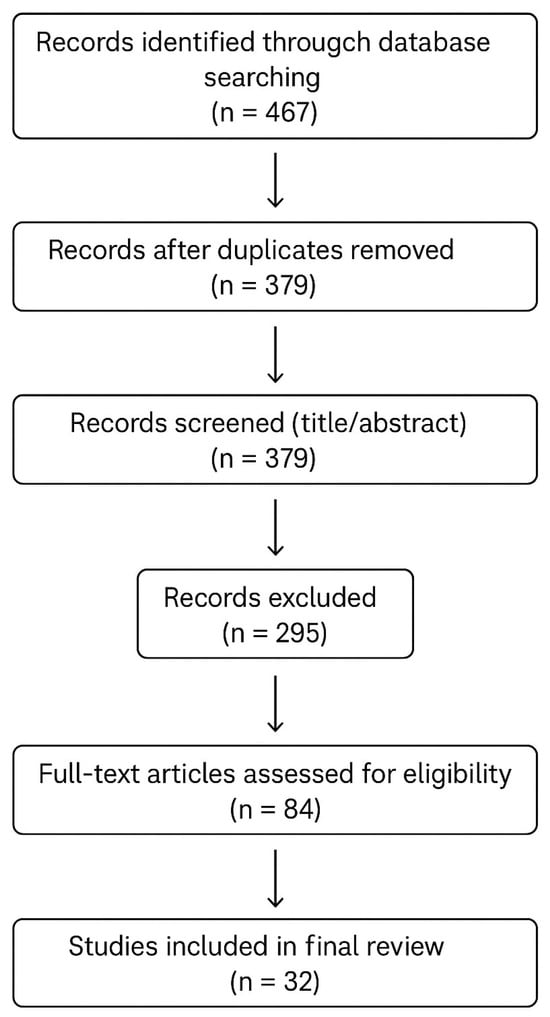

The second step was the title and abstract screening, in which two independent reviewers screened the titles and abstracts to assess relevance according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Papers unrelated to ML-based CVD prediction, ensemble modeling, or medical diagnostic applications were filtered out. Any disagreements between reviewers were resolved through discussion. The third and the last step was the full text review and final selection, in which full texts of potentially eligible studies were read in detail. Articles were evaluated based on clarity of the methodology, description of ensemble or ML models, databases used from imaging ECG and others, and performance metrics reported, and only papers meeting the full criteria were included in the final review. Figure 6 shows the PRISMA flow diagram of this study.

Figure 6.

PRISMA flow diagram of the current study.

Data Extraction

For every selected study some of the key information has been extracted using a structured data form including publication year and the author, ML or DL ensemble approach used, dataset used, and evaluation metrics. This systematic process ensured transparency, minimized reviewer bias, and allowed consistent comparison across studies.

4. Discussion

The paper discusses some challenging and unsolved issues related to the application of ML and deep-learning techniques in cardiac-disease diagnosis, including the opportunities with real-time capability analyses, exploring novel advanced feature-selection techniques [50], generating ideas for diagnostic methods and their implementations, developing web and mobile apps with strong evidence of reliability, and increasing the size of the datasets that would impact the accuracy and reliability of predictive outputs. More so, an ocean of opportunities presents itself when it comes to developing ensemble models under a combination of high data complexity together with high-dimensional data patterns. The paper strongly urges that these challenges and avenues for innovations should be prioritized in the future research agenda so as to further provide for the development of reliable and accurate diagnostic tools. The research study lists several unsolved issues in ensemble modelling, and thus, the field needs to advance in several respects. Feature selection is one such issue; it is an area that needs new techniques to increase prediction accuracy and performance [49]. Dynamic streams are typically used for timely decision making and these analyses are optimized by the ensemble learning [51]. In addition, models that address complex data patterns to enhance the performance of ensemble models need to be studied more [52]. The application of ensemble learning methods is present in diverse applications from web and mobile applications to health care, finance, and recommendation systems, among many [44]. Another avenue through which the generalization and robustness of ensemble models may be improved is widening data arrays with more diverse samples [53]. These challenges heighten the importance of conducting further research and innovation in ensemble learning so that it can overcome its existing limitations to become more generally applicable and performant across wide-ranging domains [54].

- A larger, more diverse dataset. Larger datasets improve results [23,24,25]. The method for a large population requires many risk variables. References [26,27,28] state that a study requires API or cloud-based datasets. Cloud computing can handle big patient data sets, and references [29,55] state that IoT devices can collect clinical parameters in real time, improving existing systems. Collaborating with medical practitioners to update patient descriptions and obtain more data to refine the model is difficult. References [56,57] suggest training the model(s) on different hospital data sets for good results. Validating models is difficult; however, laboratory test data helps verify predictions [3]. Medical record data analysis can improve heart CT scan models, according to [58,59], who recommend real-world datasets over simulations and theories.

- More comprehensive and large, diverse dataset: The use of more comprehensive and large, diverse datasets plays a vital role in enhancing the accuracy and robustness of predictive models in healthcare [23,24,25]. In order to effectively model the health risks of a large population, a comprehensive set of risk variables should be incorporated within the modeling structure [26,27]. These studies can utilize API or cloud-based datasets, as cloud computing can manage ample volumes of patient data in a scalable and flexible way [28]. The IoT devices also play an important role in real-time collection of clinical parameters in enhancing existing healthcare systems [29,56]. Nevertheless, updating patient descriptions with medical professionals to continually acquire additional data is very challenging [56,57]. As mentioned by [57], training models on data from different hospitals may be useful for increasing performance and generalization. Though the validation of these models is still complicated, laboratory test data can be very useful for verifying the predictions [23]. Moreover, analysis of medical record data can help improve the heart CT scan models with enhanced diagnostic accuracy [58]. To obtain the maximum possible reliability, it is suggested in [59] to rely more on real-world data sets than simulations and hypothetical models because actual clinical environments best reflect the world’s complexities.

- Electrocardiogram (ECG) Data: The evaluation of ECG data poses significant current challenges, one of the largest of which, in fact, relates to the right segmentation of various waves before assigning a rhythm label and detecting isolated beats [60]. This poses an important requirement for enhancing reliability and accuracy levels of automated analysis of ECG signals since effective segmentation directly reflects classification accuracy. Advances in signal processing techniques and ML models are required to overcome this challenge and provide more robust and precise interpretation of ECG data in real-time clinical settings. Enhanced segmentation algorithms have the potential to significantly improve diagnostic accuracy, particularly in identifying arrhythmias and other cardiac abnormalities.

- Generalized Models: Using different feature selection techniques can improve existing models considerably when dealing with data that has a large amount of missing values [61]. In addition, combining ensemble classifiers with other features can help build more accurate illness severity models for better overall model performance [15], as suggested by ref. [62]. High-dimensional data with a large volume needs an appropriate reduction strategy to efficiently handle it. In addition, to improve the minimization of redundant features, treatment of missing values, and noise removal, ref. [63] proposed a more comprehensive strategy that might be capable of providing even better results that lead to better prediction. The next step should involve developing new techniques of feature selection in order to choose the best characteristics to be input into the dataset with improved predictive performance and robustness [64]. Such innovations will aid in the deployment of ML models on real healthcare data streams toward better healthcare delivery.

- The unavailability of some models, which are not publicly accessible, calls for open-source solutions to make the predictive models more widely adopted and shared [65]. Another significant challenge is the implementation of these systems in real-world clinical settings without continuous medical supervision, making it difficult to assess their efficacy using real-time data [66]. There is, in the absence of open-source solutions, the inefficiency of diagnosis and treatment by healthcare professionals about conditions like CAD because they do not have the correct tools to make an accurate decision [27,67]. In addition, medical diagnostic tools are seldom available in large clinical environments; thereby, their implementation cannot properly improve patient outcomes [68]. Development and dissemination of open-source models addressing these gaps would empower health workers with better diagnostic support at lesser costs and possibly in more accessible ways in resource-limited settings, ultimately leading to quality improvement in healthcare services.

- In an attempt to enhance the precision of prediction, ref. [27] presented a comparison between the linear kernel of SVM with other SVM classifier kernels. The uniqueness and interpretability of the operating properties of the linear kernel made it stand out. Based on this, ref. [67] added other parameters, whereas ref. [69] suggested the DL model for integration with the system in order to make it more enhanced. Such processing is performed so that the feature extraction, data classification and precision can be increased [15]. Another study [70] recommended that probabilistic methods and CAD projections can produce reliable and robust predictions [70]. A model may produce a lower accuracy, and to increase the accuracy, a hybrid framework would be the choice to reduce stress and maximize the prediction outcome.

- The existing diagnosis methods are also used for further purposes including cancer, diabetes, various neurological disorders, and kidney disease, rather than only to be used for the CVD prediction [29,66,71]. The betterment of patients and other management would be possible if earlier detection were possible through these advanced predictive models and if these models were successfully integrated with healthcare.

- The development of new models will necessarily require enhancements in multimodal data integration, real-time analytics and other machine learning algorithms, and this will allow more efficiency and precision to clinicians, so that they can target a wider variety of chronic diseases.

- These techniques, which analyze vast visual datasets, offer great opportunities for improving diagnostic accuracy in cardiovascular health care. As ref. [72] noted, more study has been undertaken to enrich the models, and further machine learning-based refinements might make these prediction systems capable enough, as shown in Table 5, Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8.

Table 5. General surveys and reviews on ML and DL.

Table 5. General surveys and reviews on ML and DL. Table 6. Deep learning applications beyond cardiovascular focus.

Table 6. Deep learning applications beyond cardiovascular focus. Table 7. ML and DL for CVD prediction.

Table 7. ML and DL for CVD prediction. Table 8. Summary of medical diagnosis papers.

Table 8. Summary of medical diagnosis papers.

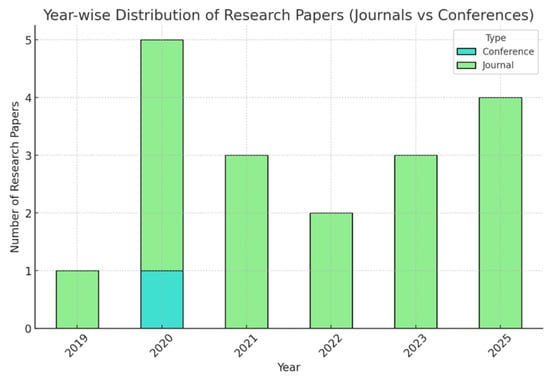

These tables show all scholarly articles concentrated on the deployment of ML and DL models for the task of CVD prediction and detection. These sources span several papers regarding the design, analysis, and utilizations of many forms of datasets: electrocardiogram-based data, genetic datasets, and more general multimodal datasets. Those have been issued over various distinguished journals between the years 2018 to 2024. Figure 7 presents the year-wise distribution of research and journals.

Figure 7.

Year-wise distribution of Research and Journals.

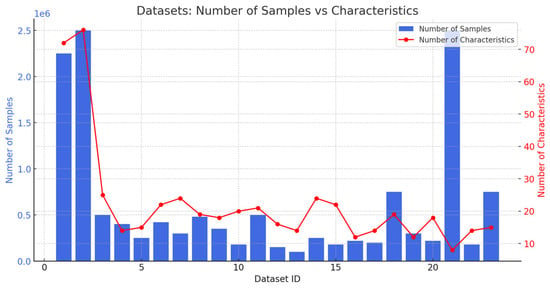

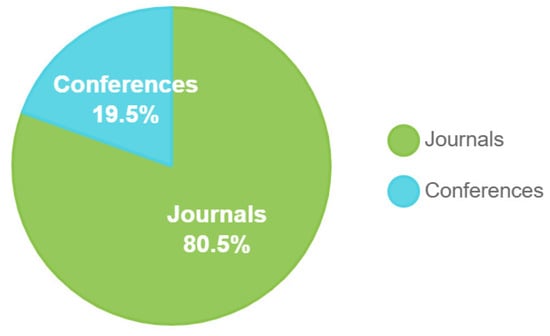

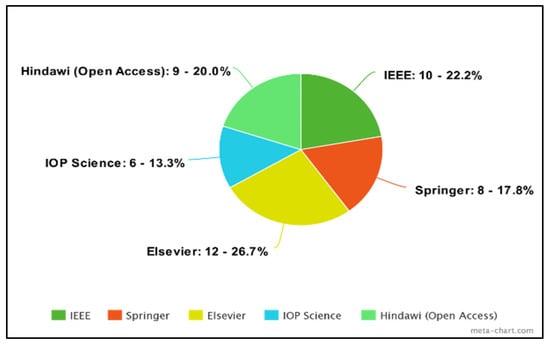

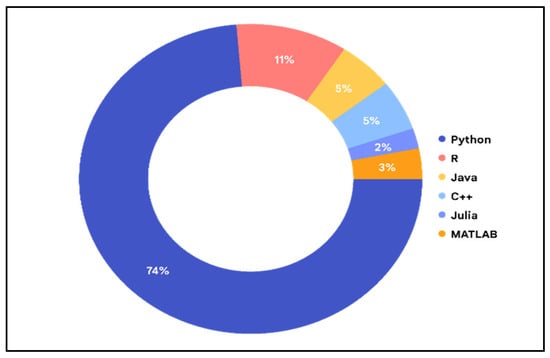

There was one journal with no conferences in 2019. In 2020, the number of journals reached five, with one conference hosted. In 2021, the journal count dropped slightly to three, and there were no conferences. The same went for 2022, which had two journals and no conferences. In 2023, three journals were recorded with no conferences. Significant growth was recorded in 2025, with four journals and no conferences. In total, there are 18 journals and 1 conference over the 7 years within this time frame. Figure 8 presents the samples and characteristics of the dataset. Figure 8 illustrates the proportion of scholarly papers derived from academic journals and conference proceedings. Figure 9 and Figure 10 show the percentage of publications, and Figure 11 shows the proportion of languages employed by the various researchers.

Figure 8.

Number of samples and characteristics.

Figure 9.

Journals and conference papers.

Figure 10.

Percentage of publications.

Figure 11.

The proportion of languages employed by the various researchers.

This study aims to compare the number of samples, and the number of characteristics present in various existing datasets.

5. Comparative Analysis of Ensemble Learning Approaches for CVD Prediction

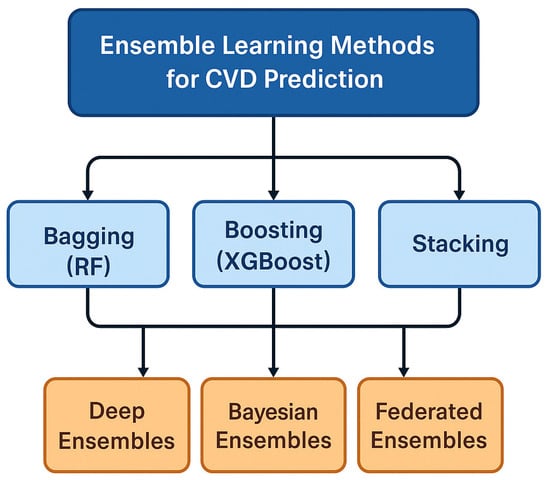

Ensemble learning methods play a central role in CVD prediction due to their ability to enhance accuracy, reduce variance, and improve robustness compared to single-model classifiers. However, different ensemble strategies offer distinct advantages and limitations, especially when evaluated in the context of clinical deployment. This subsection critically examines major ensemble categories, e.g., bagging, boosting, and stacking, as well as emerging ensemble paradigms such as deep ensembles, Bayesian ensembles, and federated ensemble learning. Figure 12 shows the illustration of the ensemble learning.

Figure 12.

Ensemble learning methods for CVD prediction.

5.1. Bagging-Based Ensembles

Random forest remains significant in the CVD context and the most widely applied ensemble in CVD diagnosis, especially for clinical-feature datasets such as Cleveland [13,38,106], Statlog [13,106], and Framingham [107]. Its popularity stems from high robustness to noise and missing values, which are common in clinical health records, low computational cost, allowing fast inference in hospital systems, built-in interpretability, via feature importance and decision-path visualization, and strong generalization performance, even for small datasets. The limitations of the random forest are less effective for sequential ECG signals compared to deep models; interpretability is still limited for clinicians who require waveform-level explanations and performance plateaus when dealing with highly nonlinear, high-dimensional data. The clinical bagging ensembles are ideal for risk-factor based CVD prediction, clinical decision-support systems, and low-resource settings.

5.2. Boosting-Based Ensembles

The significance of the boosting-based ensembles such as XGBoost [108], LightGBM, and CatBoost [41] consistently outperforms scenarios involving non-linear interactions among clinical features, moderate dataset sizes and noisy but structured medical data. Boosting models have achieved accuracy ranges of 0.91 (91%) to 0.96 (96%) in many CVD studies. The limitations of these algorithms are higher training cost, more sensitive to hyperparameter tuning and risk of overfitting in extremely small datasets. The clinical suitability of boosting is well-suited for EHR-based or tabular CVD datasets where interpretability can be balanced using feature importance plots and SHAP explanations.

5.3. Stacking and Hybrid Ensembles

The significance of the stacking ensembles combines predictions from multiple models such as RF [26,42], SVM [14,46] and Boost [9], producing the highest predictive power across many studies. In several reviewed works, stacked ensembles achieved AUC values between 0.92 (92%) and 0.98 (98%), outperforming any standalone classifier. The limitations of stacking and hybrid ensembles are increased model complexity and computational demand, difficult to interpret clinically and require careful validation to avoid data leakage. The suitability of these algorithms is best suited for specialized diagnostic tools where accuracy is critical, especially in acute CVD screening, but interpretability challenges limit routine clinical adoption.

5.4. Deep Ensembles

Deep ensembles are significant due to multiple CNN/LSTM/Transformer models trained independently and aggregated, resulting in improved uncertainty estimation, better robustness to ECG noise and reduced false positives in arrhythmia and ischemia detection. The limitations of the deep ensembles can be stated as very high computational cost, requires large ECG datasets, and deployment is challenging in real-time hospital settings. Clinical suitability can be inferred from promising for ECG-based diagnosis, emergency triage, and long-term monitoring, especially where uncertainty estimation is critical.

5.5. Bayesian Ensembles

Bayesian ensembles provide probabilistic predictive distributions, enabling confidence-aware diagnosis, risk stratification and uncertainty quantification for high-risk CVD decisions. Computational expensiveness, methodological complexity and rare implementation in clinical practice due to model size and inference overhead are the limitations for the Bayesian ensembles. Clinical suitability can be considered when used for high-stakes diagnosis, such as myocardial infarction or arrhythmia detection, where confidence estimates matter.

5.6. Federated Ensemble Learning

The significance of federated ensemble learning is that it addresses data privacy constraints by enabling hospitals to collaboratively train models without sharing patient data. Multiple limitations are reported for these algorithms such as model inversion and security concerns and the hospital distribution data, which is heterogeneous. These algorithms are best suited for the multi-institutional CVD prediction and in such conditions, and various other priorities are set such as scalability, data diversity and the privacy.

5.7. XAI for Ensemble Models in CVD Prediction

Although ensemble methods such as random forest [26,42], XGBoost [108], and stacking models provide strong predictive performance for CVD prediction, their clinical adoption requires transparency and interpretability. Recent studies demonstrate that explainable AI techniques such as SHAP, LIME, feature-importance analysis, surrogate models, and attention mechanisms for hybrid deep ensembles play a key role in revealing how ensemble models reach their decisions. The risk factors, multimodal features or ECG segments can be well understood by the clinicians and allows them to verify clinical guidelines and medical knowledge. In this case, the clinicians are helped during the process of identification and classification of potential biases, support safer deployment and can enhance trust. The gap of the real-world clinical decision making and algorithmic accuracy can be bridged when CVD prediction models are integrated with the XAI.

5.8. Summary of Ensemble Trade-Offs

The findings across the reviewed studies demonstrate that each ensemble strategy offers distinct strengths and limitations depending on the nature of cardiovascular data, the computational environment, and the clinical requirements. Bagging methods such as random forest provide strong robustness and interpretability for structured clinical datasets, whereas boosting techniques deliver superior predictive accuracy when dealing with nonlinear feature interactions. Stacking and hybrid ensembles achieve the highest performance overall but often introduce considerable complexity that may hinder clinical deployment. More advanced paradigms including deep ensembles, Bayesian ensembles, and federated ensemble frameworks offer enhanced uncertainty estimation, privacy preservation, and improved generalizability, yet they demand significantly higher computational resources and mature infrastructural support. The following Table 9 summarizes these trade-offs to assist researchers and practitioners in selecting the most suitable ensemble method for CVD prediction.

Table 9.

Summary of medical diagnosis papers.

In terms of reliability and ease of interpretation for the tabular datasets, especially for the clinical datasets, random forest has remained dominant. Boosting models offer best-in-class accuracy for structured clinical data. Deep ensembles excel in ECG waveform analysis, especially for arrhythmia detection. Stacking ensembles, though powerful, face clinical deployment barriers due to complexity. Federated ensembles address data scarcity and privacy limitations in cardiology. Bayesian and uncertainty-aware ensembles are critical for safety-critical medical decisions.

5.9. Interpretation and Implications

It is evident from the table that not a single method from the ensemble approaches is able to outperform others, especially the scenarios for all CVD prediction. Instead, the optimal choice depends on dataset size, feature modality like clinical, ECG, and multimodal, computational constraints, and the degree of interpretability required by clinicians. Traditional ensembles such as random forest and boosting models remain highly practical for feature-based clinical datasets due to their stability, ease of deployment, and explainability. In contrast, deep ensembles and Bayesian ensembles offer superior uncertainty modeling and robust capabilities essential for high-risk diagnostic decisions, though at the cost of computational efficiency and implementation complexity. Federated ensembles highlight a promising direction for multi-institutional collaboration by preserving patient privacy while improving model generalization. These differences underscore the importance of strategically aligning ensemble model selection with clinical needs, available infrastructure, and regulatory considerations.

In connection with open challenges, the comparative insights drawn from ensemble learning methods directly inform and reinforce the broader set of open challenges in applying ML to CVD prediction. Many of the limitations observed including the computational burden of deep ensembles, the interpretability gaps in stacking models, the data requirements for advanced boosting techniques, and the infrastructure demands of federated methods must align closely with ongoing challenges related to data quality, algorithmic transparency, clinical integration, and regulatory compliance. These trade-offs illustrate that performance alone cannot determine the suitability of an ensemble method for clinical deployment; rather, successful adoption depends on addressing the systemic barriers outlined in the subsequent section. The following discussion expands on these unresolved issues, offering a structured taxonomy of challenges that must be overcome to achieve reliable, equitable, and clinically meaningful CVD prediction systems.

6. Open Challenges in ML, DL, and Ensemble Learning for CVD Prediction

Many of the unresolved challenges are still pending, especially in clinical practice and prototype development even though significant work has been done in machine learning CVD prediction. Based on an integrated synthesis of the reviewed studies, we organize these challenges into four major categories: (1) Data Challenges, (2) Algorithmic Challenges, (3) Clinical Integration Challenges, and (4) Regulatory and Ethical Challenges. Each challenge is discussed in terms of the underlying difficulty, existing solutions, their shortcomings, and opportunities for future research.

6.1. Data-Related Challenges

6.1.1. Scarcity and Imbalance of High-Quality CVD Data

Most publicly available CVD datasets including Cleveland [13,42,44,106], Statlog [13,106], PTB-ECG are small, outdated, or not diverse enough to train modern ML/DL models. Typically, CVD prediction requires large, heterogeneous datasets capturing diverse demographic, physiological, and comorbidity profiles. Clinical data collection is expensive, privacy-restricted, and often fragmented across institutions. Techniques such as oversampling (SMOTE), class reweighting, and data augmentation are commonly used but often fail to generalize across patient cohorts. Synthetic ECG generation using GANs has shown promise but can distort subtle clinical signals. Promising research directions are federated learning for privacy-preserving multi-hospital data collaboration, generative models specifically tailored for ECG and multimodal signal synthesis, large-scale CVD biobanks and open-access repositories and standardized annotation protocols for consistent labeling.

6.1.2. Multimodal Data Integration Challenges

Accurate CVD prediction often requires combining ECG signals, lab values, imaging, demographic data, and clinical histories. Different modalities have incompatible formats, sampling rates, and noise characteristics, creating barriers for unified ML/DL pipelines. Most existing studies use either ECG-only or clinical data-only models, while true multimodal fusion remains rare due to the lack of aligned datasets. Promising research directions include cross-modal transformers and attention-based fusion architectures, graph neural networks modeling interactions between risk factors, creation of multimodal benchmark datasets for CVD prediction and unified feature-learning frameworks for heterogeneous medical data.

6.2. Algorithmic Challenges

6.2.1. Lack of Model Interpretability and Clinical Explainability

Deep models, namely CNNs, LSTMs, and Transformers achieve high performance but operate as “black boxes,” limiting trust and clinical adoption. ECG waveforms and risk-factor interactions are highly nonlinear and complex, making transparent feature attribution difficult. Methods such as Grad-CAM, SHAP, and LIME provide partial explanations but are unreliable or inconsistent across patients. Promising research directions include clinically meaningful interpretability frameworks aligned with cardiology guidelines, causal ML to identify true risk pathways, rule-based hybrid models integrating domain knowledge, and ECG-specific explainability models that highlight clinically validated waveform segments.

6.2.2. Generalization and Robustness Across Populations

Models trained in one population often fail when applied to different ethnic, geographic, or hospital settings. Differences in device types, sampling noise, comorbidities, and labeling standards degrade model robustness. Cross-validation and domain adaptation techniques partially address distribution shifts but still exhibit performance drops. Promising research directions are domain generalization techniques for unseen population shifts, continual learning with incremental patient data, and robust training using noise-invariant and device-specific adaptation techniques.

6.3. Challenges in Clinical Integration

6.3.1. Workflow Compatibility and Real-World Deployment

Most ML/DL models are developed in research settings and do not align with hospital workflows, clinician routines, or decision-making systems. Clinical systems require reliability, low latency, clear interpretability, and integration with electronic health records. Current approaches and limitations are prototype ML models and are often not validated in real-time settings or tested in clinical pilot trials. Promising research directions are deployable decision-support systems integrated into EHRs, real-time ECG analysis platforms, clinician-centered interface designs and human-in-the-loop validation workflows.

6.3.2. Lack of External Validation and Prospective Studies

Most reported models rely solely on retrospective datasets. Prospective clinical trials require regulatory approval, ethical review, and long-term data collection. Current approaches and limitations are that cross-dataset testing is used but remains insufficient as a substitute for real-world validation. Promising research directions are prospective cohort studies evaluating ML/DL models, multi-site external validation involving diverse demographics, and longitudinal model monitoring to detect performance drift.

6.4. Regulatory, Ethical, and Governance Challenges

6.4.1. Data Privacy, Security, and Compliance

Medical data is among the most sensitive and heavily regulated, affecting data sharing and model development. It is difficult to balance clinical utility with HIPAA/GDPR restrictions, which are technically and legally complex. Current approaches and limitations are de-identification and anonymization, which are often insufficient and may reduce dataset utility. Promising research directions are differential privacy methods for medical datasets, federated and split learning architectures, and secure multi-party computation for inter-hospital collaboration.

6.4.2. Fairness, Bias, and Ethical Decision-Making

ML/DL models may reflect or amplify disparities across gender, ethnicity, age, or socioeconomic groups. It is difficult because bias is deeply embedded in data collection, annotation, and clinical practice. Current approaches and limitations are that fairness metrics exist but are rarely applied in CVD-focused ML literature. Medical datasets and training algorithms based on fairness and the guidelines for the AI evaluation are the potential research directions and the application development in this area.

6.5. Summary of Open Challenges

The analysis shows that open challenges in ML-based CVD prediction are multi-dimensional, spanning data quality, algorithmic limitations, clinical applicability, and regulatory constraints. Addressing these interdependent issues will require interdisciplinary collaboration across AI researchers, clinicians, health policymakers, and regulatory bodies.

7. Limitations

Acknowledgment of the limitations regarding the current study are presented here, which illustrates the scope of this systematic survey.

7.1. Variability in Reporting Standards Across Studies

The reviewed literature exhibits substantial heterogeneity in evaluation protocols, dataset preprocessing, and reported performance metrics. Many studies rely solely on accuracy, without reporting complementary indicators such as recall, sensitivity, specificity, F1-score, calibration, or uncertainty measures. This inconsistency limits direct comparability and may obscure methodological weaknesses or overfitting.

7.2. Limited Reliability of High Accuracy Claims

The various research has presented more than 95% accuracy, and such accuracy is limited to the single-center datasets, imbalance and small size of the datasets. The reported values are not suitable for the performance of real-world scenarios due to the impact of the optimistic validation scheme, overfitting of values and lack of external testing. These algorithms are very difficult to generalize, as cross-institutional validation, independent datasets, and prospective clinical evaluation are required to validate such algorithms.

7.3. Dataset Bias and Restricted Demographic Representation

Most publicly available CVD datasets such as Cleveland [13,38,42,106], Statlog [13,106], and PTB-ECG have limited demographic diversity, with underrepresentation of older adults, women, and certain ethnic groups. These biases hinder the generalizability of ML/DL models and may contribute to unfair or unreliable predictions in clinical settings. The scarcity of large multimodal datasets also restricts the evaluation of advanced models such as deep ensembles and hybrid fusion architectures.

7.4. Methodological Inconsistencies and Lack of Reproducibility

Many studies fail to provide complete methodological details including hyperparameters, sampling strategies, and preprocessing pipelines, making reproducibility difficult. Some works omit clear descriptions of train–test splits, cross-validation procedures, or data augmentation strategies, which further complicate comparison across models.

7.5. Limited Consideration of Clinical Integration

While the surveyed methods achieve promising results, very few studies evaluate deployment feasibility, clinical workflow integration, or real-time constraints. Important aspects such as interpretability, clinician acceptance, inference latency, hardware availability, and regulatory approvals remain underexplored. Thus, practical adoption of these models in real-world cardiology environments is still an open challenge.

7.6. Lack of External Validation and Prospective Trials

Only a small fraction of studies conduct external validation across multiple hospitals or devices, and almost none are assessed in prospective clinical trials. This gap limits confidence in model robustness and reliability. Without evaluation under real-world conditions such as variable noise levels, missing data, and diverse clinical presentations, current models cannot be assumed to perform safely in practice.

7.7. Constraints of the Survey Itself

Although this survey followed systematic procedures, the completeness of the review is limited by the available literature, inconsistent reporting, and the lack of standardized datasets in the field. While PRISMA methodology was adopted, some relevant studies may remain unidentified due to database indexing variations or insufficient metadata.

Taken together, these limitations highlight the need for standardized reporting practices, larger multimodal datasets, rigorous validation pipelines, interpretable models, and deeper collaboration between data scientists and clinicians. Addressing these constraints is essential for transitioning ML/DL-based cardiovascular prediction models from research prototypes to clinically trustworthy tools.

8. Future Work

Building on the limitations identified in this survey, several promising research directions can enhance the development, reliability, and clinical relevance of ML and ensemble-based CVD prediction models.

8.1. Development of Large, Diverse, and Multimodal CVD Datasets

Future work should prioritize the creation of large-scale, demographically diverse datasets that combine clinical variables, ECG signals, imaging modalities, wearable-sensor data, and electronic health records. Such multimodal datasets will enable comprehensive model development, reduce demographic bias, and support generalizable ML pipelines.

8.2. Standardization of Evaluation Protocols

The field would benefit from standardized benchmarking frameworks that mandate reporting multiple performance metrics including AUC, sensitivity, specificity, and F1-score and clearly defined train–test splits. Establishing unified evaluation procedures will significantly improve reproducibility and enable robust model comparison across studies and institutions.

8.3. Advancing Interpretability and Clinician-in-the-Loop Modeling

Interpretability remains a key barrier to clinical adoption. Future research should explore human-centered AI approaches that integrate clinician feedback, domain knowledge, and transparent decision pathways. New explainability mechanisms tailored to ECG waveforms, risk factors, and multimodal inputs can further increase trust and usability in clinical workflows.

8.4. Exploration of Uncertainty-Aware and Safety-Critical AI Models

Deep ensembles, Bayesian methods, and calibrated uncertainty estimation provide meaningful confidence scores essential for high-stakes medical decisions. Future investigations should evaluate how uncertainty-aware models can reduce diagnostic errors, flag ambiguous predictions, and guide clinicians in real-time triage scenarios.

8.5. External Validation and Prospective Clinical Trials

To ensure real-world applicability, future studies must prioritize external validation across institutions, geographic regions, and patient subgroups. Prospective clinical studies including pilot deployments in cardiology departments are needed to examine practical constraints such as latency, reliability, device variability, and clinician acceptance.

8.6. Federated and Privacy-Preserving Learning Frameworks

Privacy regulations often limit the availability of patient-level CVD data. Federated learning, secure multi-party computation, and privacy-enhancing technologies offer pathways for collaborative model development without direct data sharing. Future research should explore federated ensemble architectures to enhance generalizability while maintaining regulatory compliance.

8.7. Integration of Models into Clinical Information Systems

Real-world implementation requires compatibility with electronic health records, medical devices, and hospital workflow infrastructure. Future work should examine deployment strategies, system integration challenges, and operational scalability, including lightweight model architectures for bedside and remote monitoring environments.

8.8. Addressing Bias, Fairness, and Ethical Considerations

Future studies should systematically assess and mitigate model bias related to age, gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic factors, and comorbidities. Ethical frameworks must be developed to guide safe deployment, model updates, automated decision support, and accountability within healthcare institutions.

The advancement of CVD prediction using ML relies not only on technical innovation but also on rigorous validation, fairness, interpretability, and seamless integration into real-world clinical environments. Addressing these areas will pave the way for AI systems that are accurate, trustworthy, and clinically transformative.

9. Conclusions

A comprehensive survey has been presented for the use of ML approaches for the detection of CVD disease. The authors suggest that ML and ensemble learning techniques have potential utility for the background detection and diagnosis of CVDs. The risk of CVDs is reflected in global mortality statistics. The study reviewed different types of classifiers: decision and support vector machines, neural and Naive Bayes, random forest, K-nearest neighbors and others. It showed that all of these classifiers integrated with different ensemble techniques (bagging, boosting, stacking, etc.) provided better predictive accuracy, robustness, and reliability, and were therefore more useful than the individual classifiers. The authors point out several promising challenges that remain: the availability of large, heterogeneous datasets, efficient feature selection, real-time analyses, and robust segmentation of ECGs, as well as the development of other open-source tools. It is suggested that future efforts focus on ensemble and DL and possibly incorporate reinforcement learning for more sophisticated applications in complex environments in the healthcare sector. The combination of cloud technologies and IoT devices has great potential for integrating diagnostic systems and facilitating real-time analyses, which could help expedite the initial assessments in a clinical environment. Explainable AI will help generate straightforward reports demonstrating compliance with the clinical system regulatory obligations.

In conclusion, ML and ensemble methods foregrounded this study, and health experts are yet to solve several crucial aspects through further study and analysis, but more grounds remain open. Models could be developed to deal with big data heterogeneity and added dimensions found in clinical and demographic details in order to make them more generalizable and less inclined to prejudice or subject stats. Before allowing scalability and entering the day-to-day matter of clinically sophisticated clinical diagnostics, we recommend the potential use of IoT or cloud networks to give this clinical framework time to be built. In the health field, however, the practical implementation of these models and the inclusion of explicable AI frameworks are mandatory, and it is necessary to adhere to clearer and more easily introduced trust-building principles, which are founded, above all, on the use of it in clinical guideline AI or disease.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work. G.G. and D.N.H. conducted the data collection and data finetuning, and O.A.R. and M.B. performed partial experiments along with D.N.H., G.G. and I.A.K., who wrote the main paper, and N.I.A., H.A. and A.A. wrote other information. All authors discussed the results and implications and commented on the manuscript at all stages. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Software applications and customized code will be made available upon request for research purposes.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jindal, H.; Agrawal, S.; Khera, R.; Jain, R.; Nagrath, P. Heart disease prediction using machine learning algorithms. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1022, 012072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhushan, M.; Pandit, A.; Garg, A. Machine Learning and Deep Learning Techniques for the Analysis of Heart Disease: A Systematic Literature Review, Open Challenges and Future Directions; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgendy, M.S.; Moustafa, H.E.-D.; Nafea, H.B.; Shaban, W.M. Utilizing voting classifiers for enhanced analysis and diagnosis of cardiac conditions. Results Eng. 2025, 26, 104636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukhatem, C.; Youssef, H.Y.; Nassif, A.B. Heart Disease Prediction Using Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2022 Advances in Science and Engineering Technology International Conferences (ASET), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 21–24 February 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, A.; Dowlatshahi, M.B.; Nezamabadi-Pour, H. Ensemble of feature selection algorithms: A multi-criteria decision-making approach. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern. 2022, 13, 49–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Y.; Kaur, G.K.; Singh, R. Comprehensive review of machine learning applications in heart disease prediction. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Technol. 2024, 9, 2805–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganie, S.M.; Pramanik, P.K.D.; Zhao, Z. Ensemble learning with explainable AI for improved heart disease prediction based on multiple datasets. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eini, P.; Rezayee, M.; Kassulke, M.; Tremblay, J. Efficacy and Comparative Performance of Machine Learning Models for Stroke Risk Prediction in Hypertensive Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Cardiol. Cardiovasc. Risk Prev. 2025, 200564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.; Bilal, A.; Aslam, M.A.; Mustafa, H. Heart Disease Detection: A Comprehensive Analysis of Machine Learning, Ensemble Learning, and Deep Learning Algorithms. Nano Biomed. Eng. 2024, 16, 677–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Krentz, A.; Lu, L.; Curcin, V. Machine learning based prediction models for cardiovascular disease risk using electronic health records data: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Heart J. Digit. Health 2024, 6, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Deng, L.; He, X. Development and validation of an ultrasound-based AI-radiomics model for diagnosing and risk-stratifying gastrointestional stromal tumors: A retrospective diagnostic study. BMC Med. Imaging 2025, 25, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sharma, D.; Aujla, G.S.; Bajaj, R. Deep neuro-fuzzy approach for risk and severity prediction using recommendation systems in connected health care. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 2021, 32, e4159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjit, S.; Bhattacharyya, T.; Chatterjee, B.; Sarkar, R. Simulated annealing aided genetic algorithm for gene selection from microarray data. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 158, 106854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sodhar, I.N.; Jalbani, A.H.; Buller, A.H.; Channa, M.I.; Hakro, D.N. Sentiment analysis of Romanized Sindhi text. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2020, 38, 5877–5883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, H.; Chen, Y.; Yang, C.; Cheng, H.; Li, Y.; Zhong, W.; Wang, F. Ensemble machine learning approach for screening of coronary heart disease based on echocardiography and risk factors. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2021, 21, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bihri, H.; Charaf, L.A.; Azzouzi, S.; Charaf, M.E.H. A Robust Stacking-Based Ensemble Model for Predicting Cardiovascular Diseases. AI 2025, 6, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, P.; Rani, R. Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning, Ensemble Learning and Deep Learning Classifiers for Parkinson’s Disease Detection. SN Comput. Sci. 2024, 5, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.; Chugh, A.; Sharma, A. Ensemble framework for cardiovascular disease prediction. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 146, 105624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babar, M. A hybrid approach to financial big data analysis using extended ensemble learning and optimized spark streaming. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2025, 11, 100602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganie, S.M.; Pramanik, P.K.D.; Malik, M.B.; Nayyar, A.; Kwak, K.S. An Improved Ensemble Learning Approach for Heart Disease Prediction Using Boosting Algorithms. Comput. Syst. Sci. Eng. 2023, 46, 3993–4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.F. Radiation Oncology in the Era of Big Data and Machine Learning for Precision Medicine. In Artificial Intelligence—Applications in Medicine and Biology; Books on Demand: Norderstedt, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navita; Mittal, P.; Sharma, Y.K.; Lilhore, U.K.; Simaiya, S.; Saleem, K.; Ghith, E.S. Advanced Hybrid Machine Learning Model for Accurate Detection of Cardiovascular Disease. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2025, 18, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, J.; Nouri-Moghaddam, B. A hybrid method for heart disease diagnosis utilizing feature selection based ensemble classifier model generation. Iran J. Comput. Sci. 2022, 5, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Gao, L. Machine learning-based myocardial infarction bibliometric analysis. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1477351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maulani, A.A.; Winarno, S.; Zeniarja, J.; Putri, R.T.E.; Cahyani, A.N. Comparison of Hyperparameter Optimization Techniques in Hybrid CNN-LSTM Model for Heart Disease Classification. Sink. J. Dan Penelit. Tek. Inform. 2024, 8, 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torthi, R.; Marapatla, A.D.K.; Mande, S.; Gadiraju, H.K.V.; Kanumuri, C. Heart Disease Prediction Using Random Forest Based Hybrid Optimization Algorithms. Int. J. Intell. Eng. Syst. 2024, 17, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreekumari, S.; Bhalla, R.; Singh, G. Feature Selection and Model Evaluation for Heart Disease Prediction Using Ensemble Methods. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2025, 259, 1282–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, A.C.S.R.; Sengan, S. Edge computing-based ensemble learning model for health care decision systems. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, Y.A.; Khanan, A.; Bashir, M.; Hakro, D.N.; Babar, M. A survey on health spending and comprehensive eGuide for healthcare: Challenges, implementation and future directions. Sustain. Futures 2026, 11, 101584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teja, M.D.; Rayalu, G.M. Optimizing heart disease diagnosis with advanced machine learning models: A comparison of predictive performance. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2025, 25, 4627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Lv, H.; Chen, N. A survey on ensemble learning under the era of deep learning. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2023, 56, 5545–5589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mienye, I.D.; Sun, Y. A survey of ensemble learning: Concepts, algorithms, applications, and prospects. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 99129–99149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akella, A.; Akella, S. Machine learning algorithms for predicting coronary artery disease: Efforts toward an open-source solution. Future Sci. OA 2021, 7, FSO698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganaie, M.A.; Hu, M.; Malik, A.K.; Tanveer, M.; Suganthan, P.N. Ensemble deep learning: A review. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 115, 105151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalvi, J.J.; Khole, S.M.; Kudale, B. A Survey on Heart Disease Prediction Using Machine Learning Techniques. Algorithms 2018, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ramalingam, V.V.; Dandapath, A.; Raja, M.K. Heart disease prediction using machine learning techniques: A survey. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 7, 684–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieu, S.T.H.; Bade, A.; Hijazi, M.H.A.; Kolivand, H. A survey of deep learning for lung disease detection on medical images: State-of-the-art, taxonomy, issues and future directions. J. Imaging 2020, 6, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, P.; Azam, S.; Jonkman, M.; Karim, A.; Shamrat, F.M.J.; Ignatious, E.; Shultana, S.; Beeravolu, A.R.; De Boer, F. Efficient prediction of cardiovascular disease using machine learning algorithms with relief and lasso feature selection techniques. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 19304–19326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, M.; Awan, A.A.; Khalid, M.S.; Nisar, S. Ensemble approach for developing a smart heart disease prediction system using classification algorithms. Res. Rep. Clin. Cardiol. 2018, 9, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Ghosh, R.; Das, D. An ensemble approach to stabilize the features for multi-domain sentiment analysis using supervised machine learning. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2017, 32, 3543–3554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, D.; Bibi, M.; Arif, M.S.; Mukheimer, A. Enhancing heart disease prediction through ensemble learning techniques with hyperparameter optimization. Algorithms 2023, 16, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shafiey, M.G.; Hagag, A.; El-Dahshan, E.S.A.; Ismail, M.A. A hybrid GA and PSO optimized approach for heart-disease prediction based on Random Forest. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2022, 81, 18155–18179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Yu, Z.; Cao, W.; Shi, Y.; Ma, Q. A survey on ensemble learning. Front. Comput. Sci. 2020, 14, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.Y.; Ali, A.A.; Hassan, H.S.; Anwar, E.M. Improving the accuracy for analyzing heart disease prediction based on the ensemble method. Complexity 2021, 2021, 6663455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, A.; Alsubai, S.; Sha, M.; Vilcekova, L.; Javed, T. Cardiovascular disease detection using ensemble learning. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 5267498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, P.; Seth, D. Comparative analysis and feature importance of machine learning and deep learning for heart disease prediction. Indones. J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 2022, 29, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limbitote, T.W.; Lavanya, D.; Vetrivel, S. A survey on prediction techniques of heart disease using machine learning. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2020, 9, 2083–2088. [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan, P.; Uddin, S.; Hajati, F.; Moni, M.A. Ensemble learning for disease prediction: A review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, K.; Kumar, V.V.; Mahesh, T.R.; Abbas, M.; Kathamuthu, N.; Mohan, E.; Annand, J.R. Efficient Heart Disease Classification Through Stacked Ensemble with Optimized Firefly Feature Selection. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2024, 17, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Fatlawi, A.; Al-Shammaa, S.S.; Taha, Z.A. Prediction and classification models of heart disease using machine learning algorithms: A review. J. Inf. Sci. Eng. 2020, 36, 595–614. [Google Scholar]

- Fitriyani, N.L.; Syafrudin, M.; Alfian, G.; Rhee, J. Development of disease prediction model based on ensemble learning approach for diabetes and hypertension. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 144777–144789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sayed, A.; Khayyat, M.M.; Zamzami, N. Predicting Heart Disease Using Collaborative Clustering and Ensemble Learning Techniques. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 13278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Yue, X.; Mane, H.; Seelman, K.; Mullaputi, P.S.P.; Dennard, E.; Alibilli, A.S.; Merchant, J.S.; Criss, S.; Hswen, Y.; et al. Decoding Digital Discourse Through Multimodal Text and Image Machine Learning Models to Classify Sentiment and Detect Hate Speech in Race- and Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, and Asexual Community–Related Posts on Social Media: Quantitative Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e72822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, P.; Srivastava, S.; Xu, X.; Mehta, J.L. Artificial intelligence, machine learning, and cardiovascular disease. Clin. Med. Insights: Cardiol. 2020, 14, 1179546820927404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamad, A.; Jasim, A. Heart disease diagnosis based on deep learning network. Open J. Sci. Technol. 2021, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Hu, Y.; Liu, Z.-P. Prediction of cardiovascular diseases by integrating multi-modal features with machine learning methods. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2021, 66, 102474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, R.; Beeravolu, A.R.; Karim, A.; Azam, S.; Hasan, T.; Alam, M.; Ghosh, P. A robust deep learning-based prediction system of heart disease using a combination of five datasets. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Computer Theory and Applications (ICCTA), Alexandria, Egypt, 11–13 December 2021; pp. 223–228. [Google Scholar]

- Tomov, S.; Tomov, S. A novel deep learning approach to improving heart disease diagnosis. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2021, 66, 10274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajdhan, A.; Agarwal, A.; Sai, M.; Ravi, D.; Ghuli, P. Heart disease prediction using machine learning. Int. J. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 659–662. [Google Scholar]