Hybrid GNN–LSTM Architecture for Probabilistic IoT Botnet Detection with Calibrated Risk Assessment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overall Framework

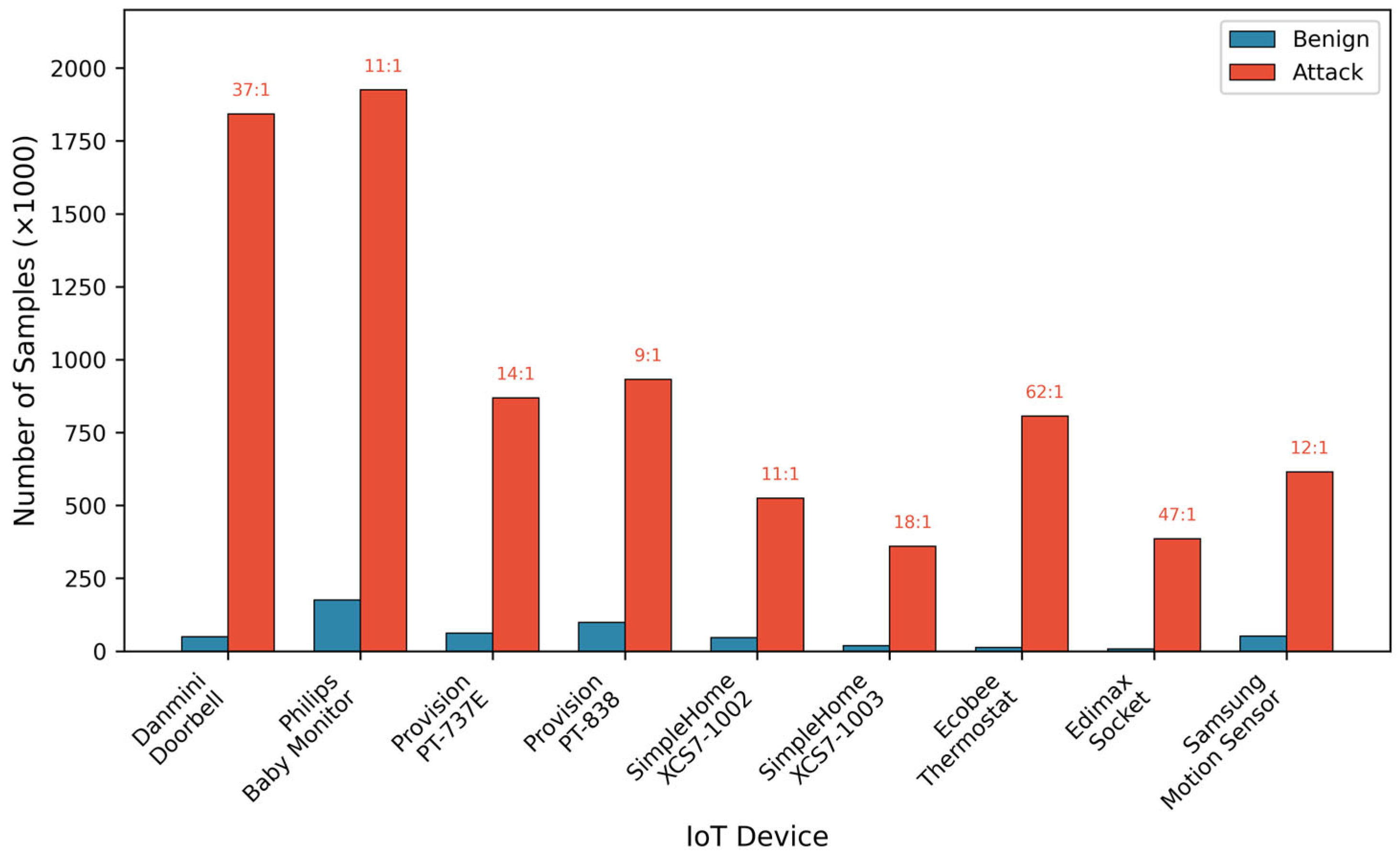

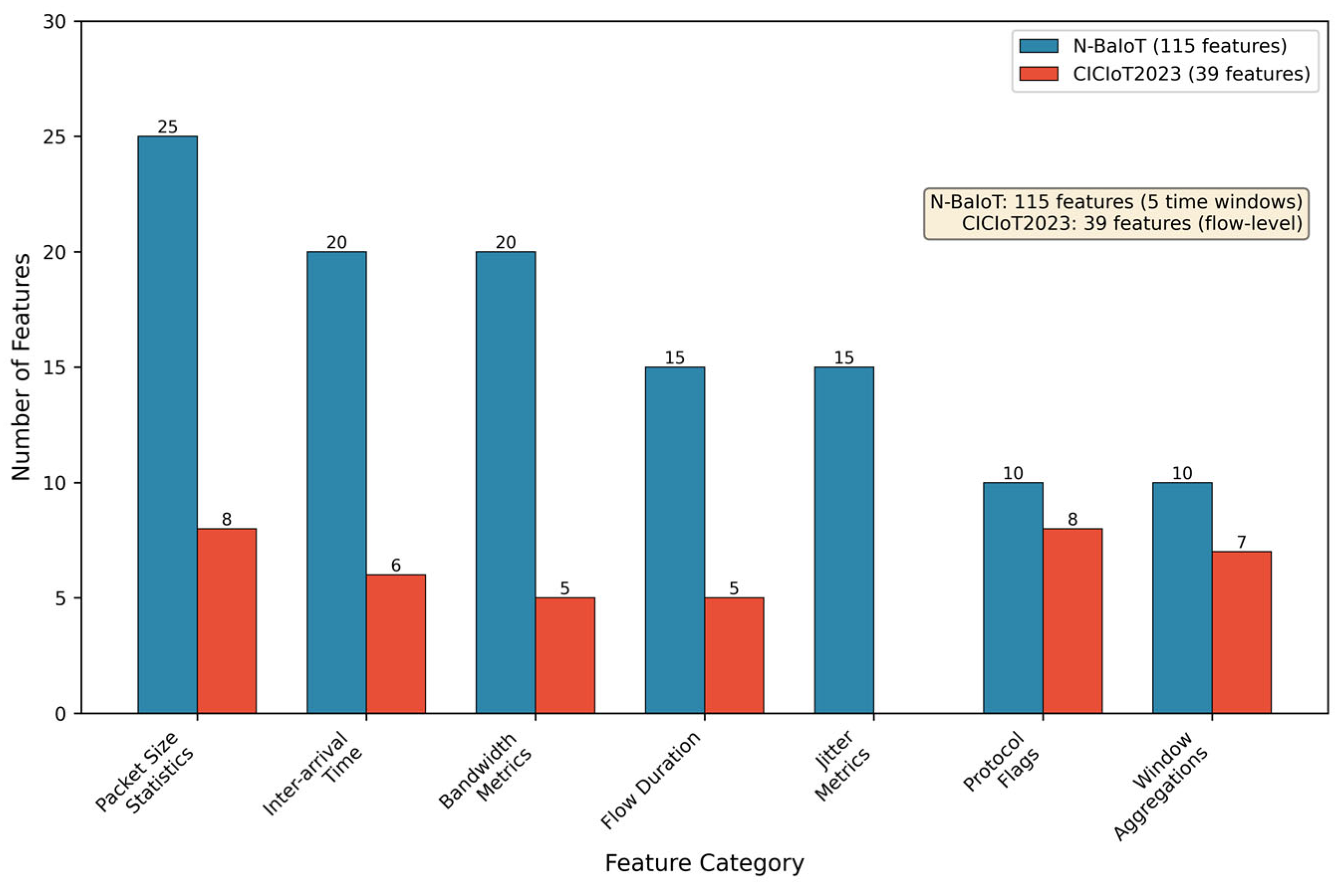

2.2. Dataset Description

2.2.1. N-BaIoT Dataset

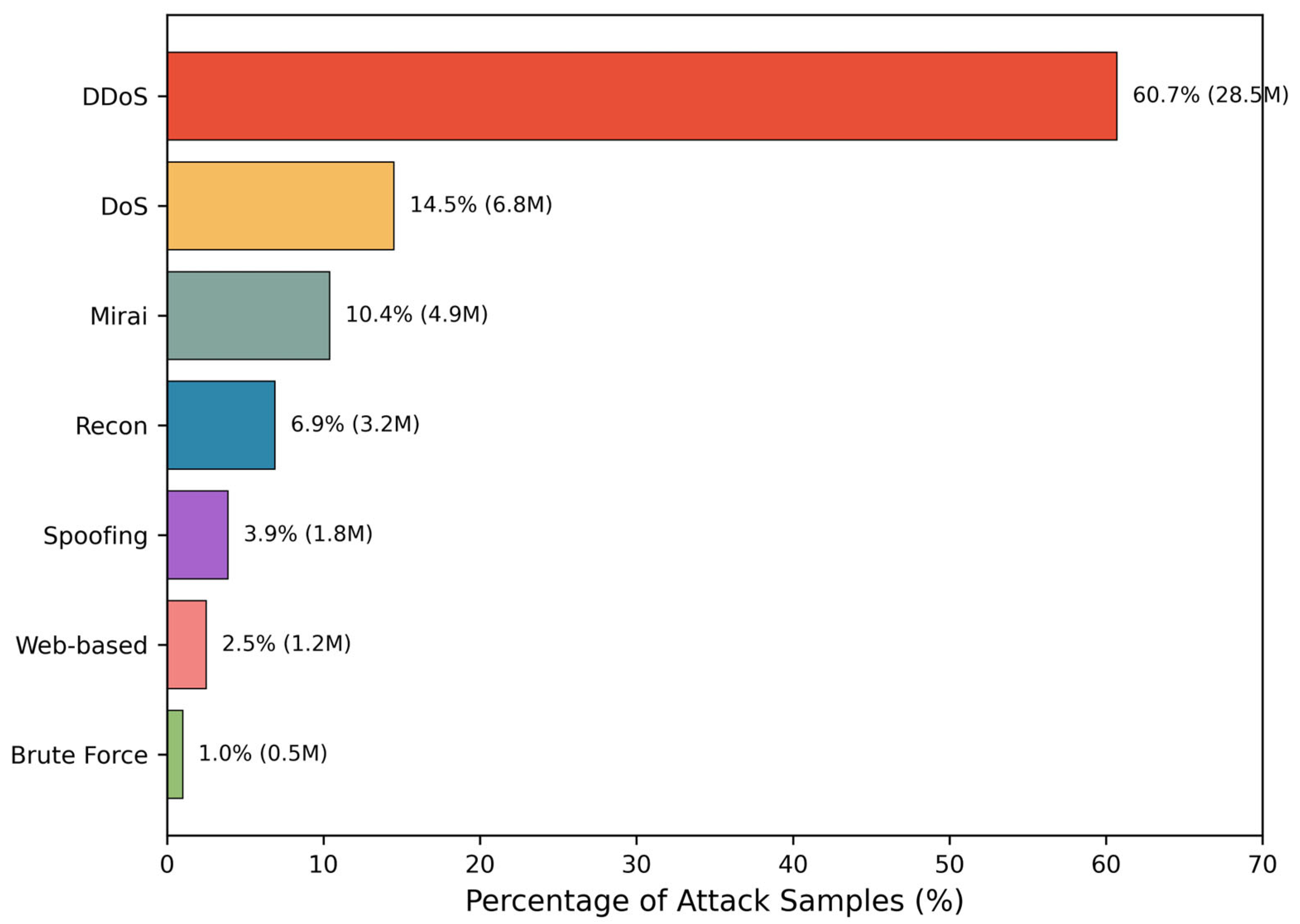

2.2.2. CICIoT2023 Dataset

2.2.3. Data Preprocessing

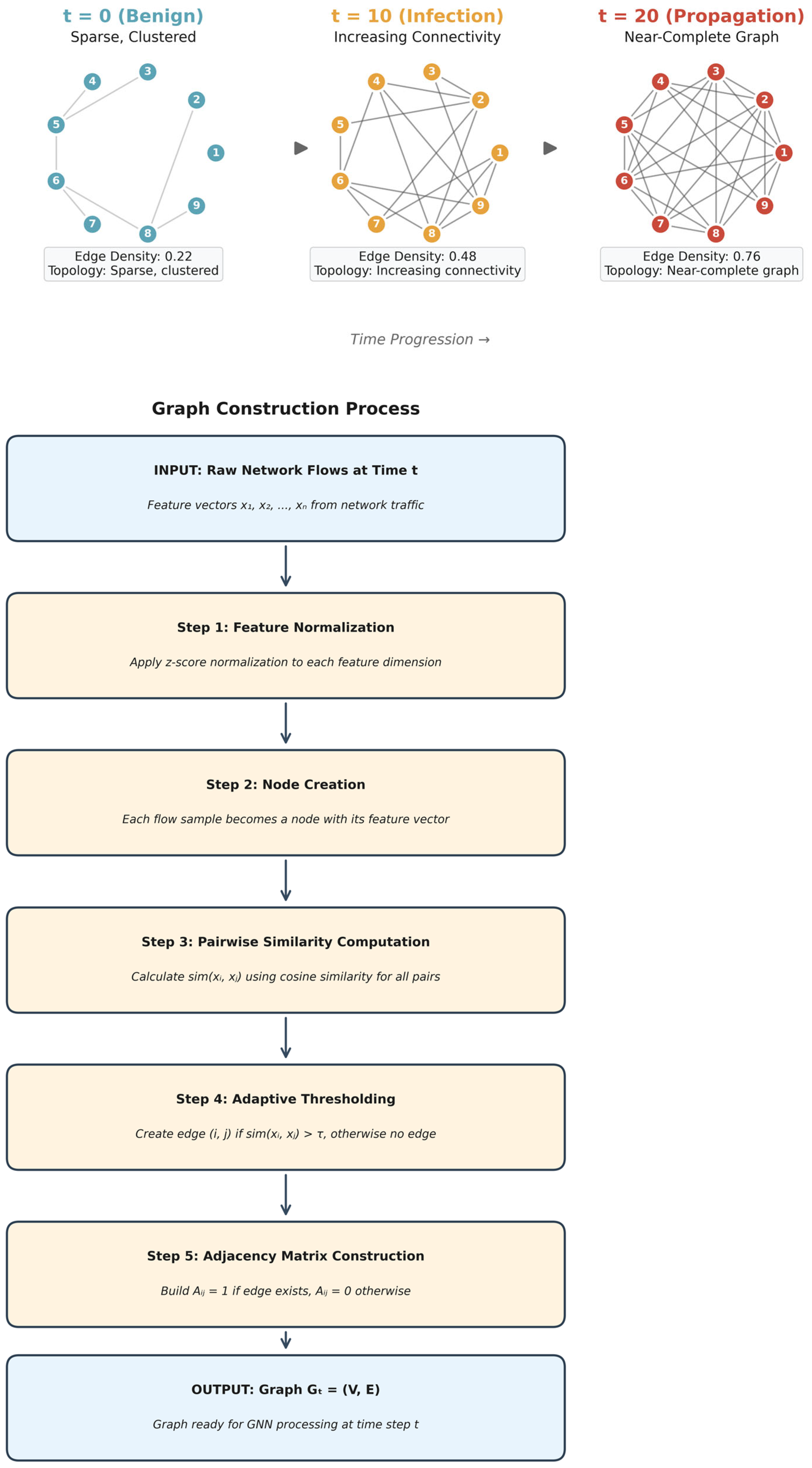

2.3. Graph Construction and Feature Representation

2.4. Hybrid Model Architecture

2.5. Risk Scoring and Calibration

3. Results

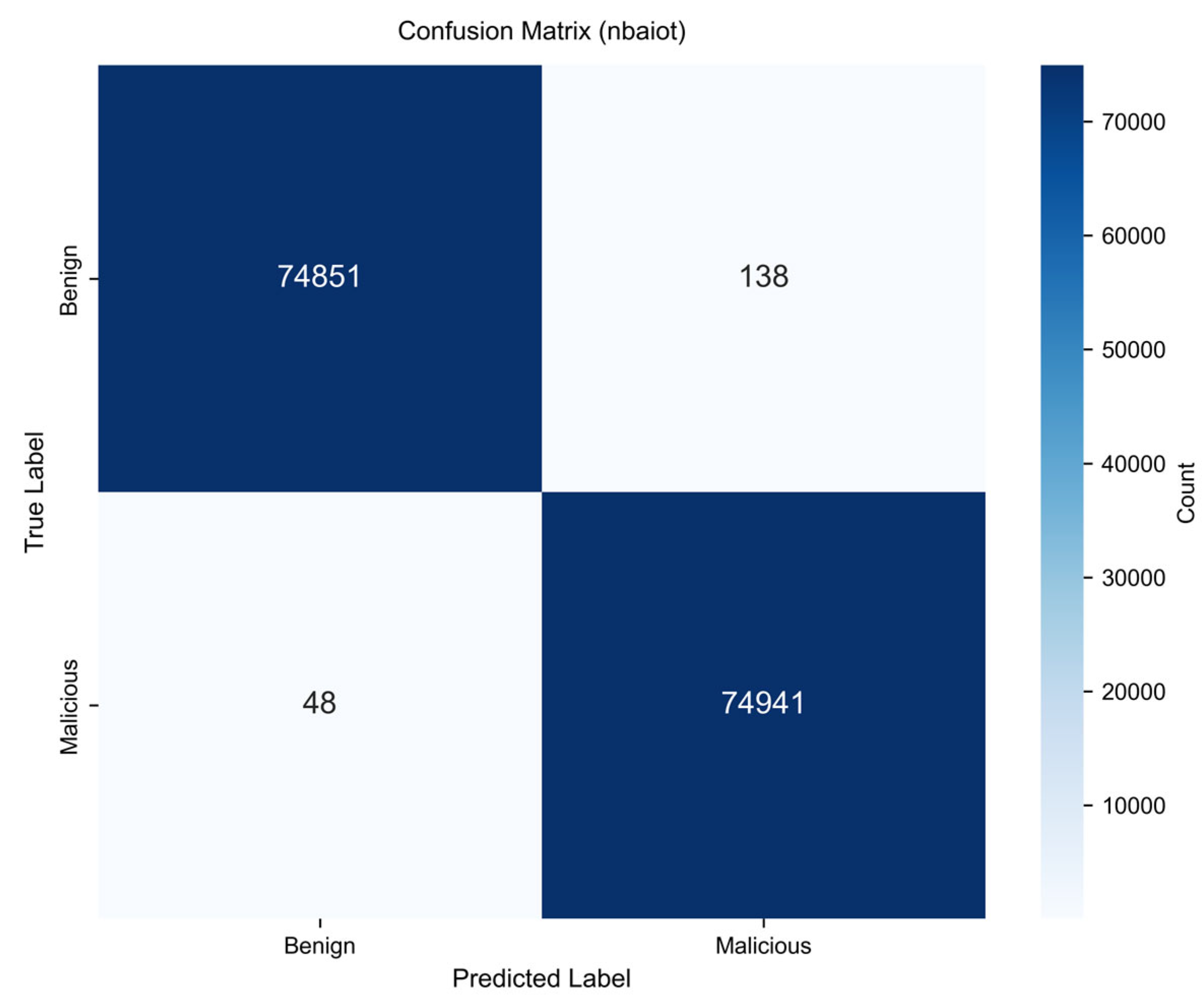

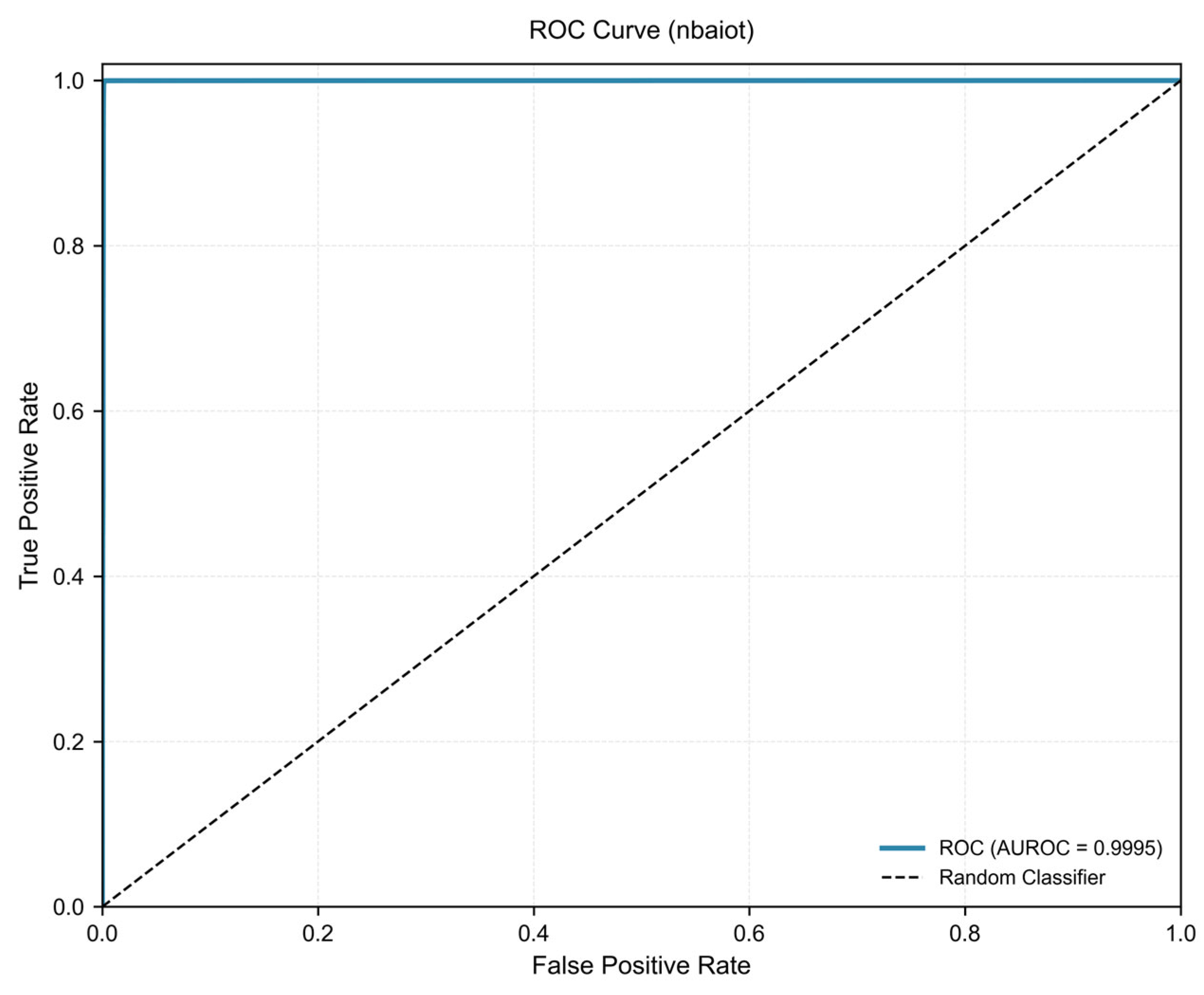

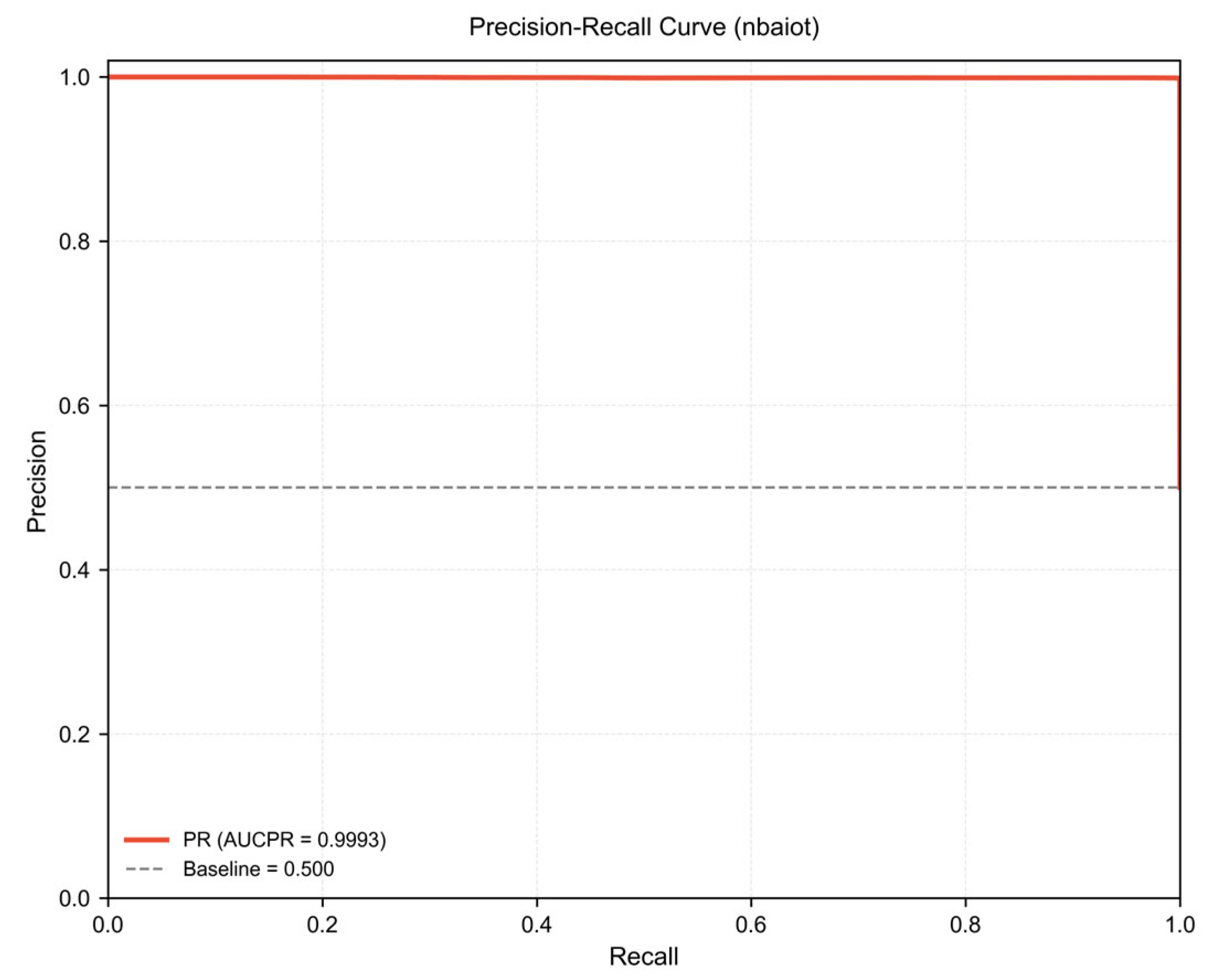

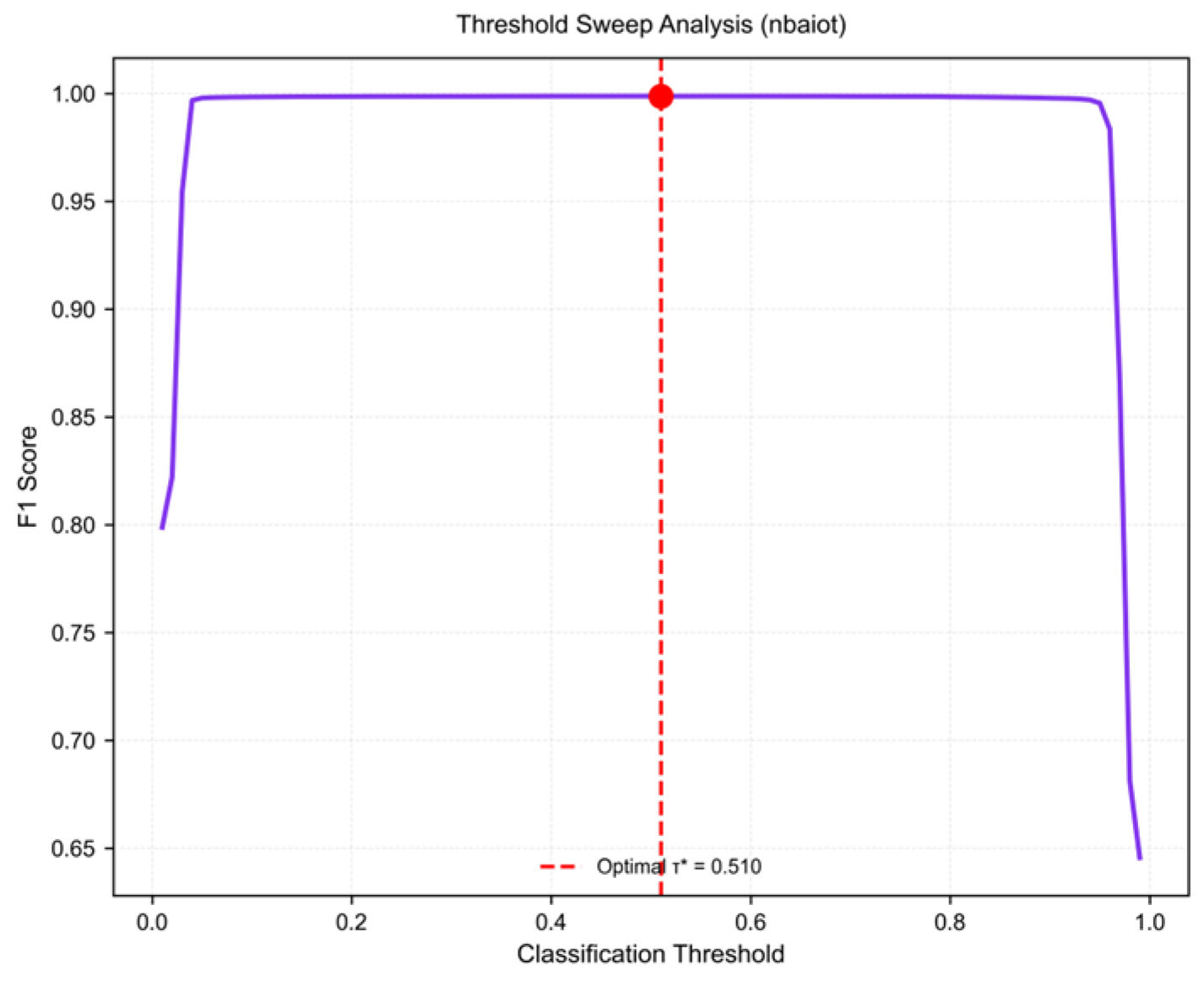

3.1. Classification Performance on N-BaIoT

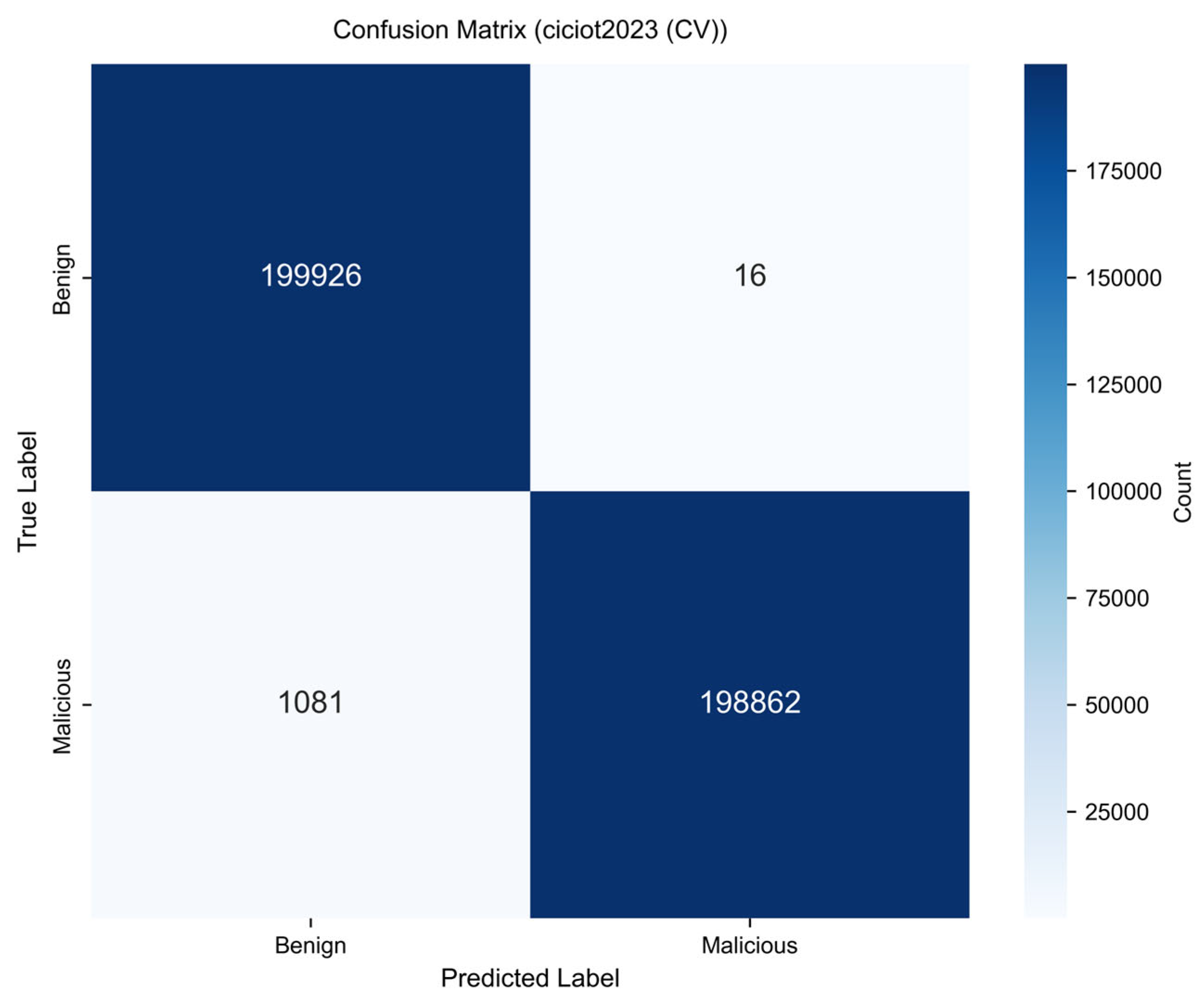

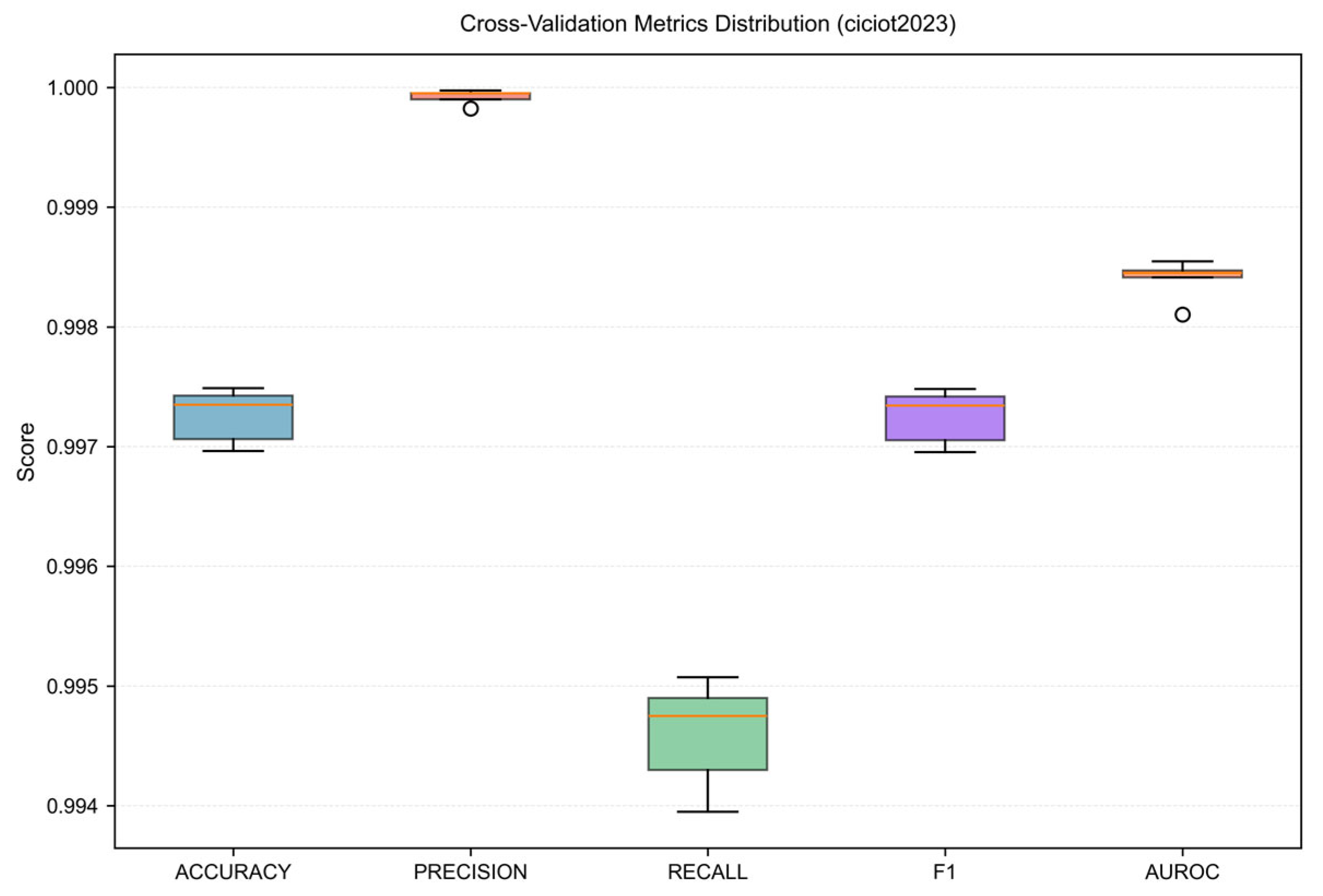

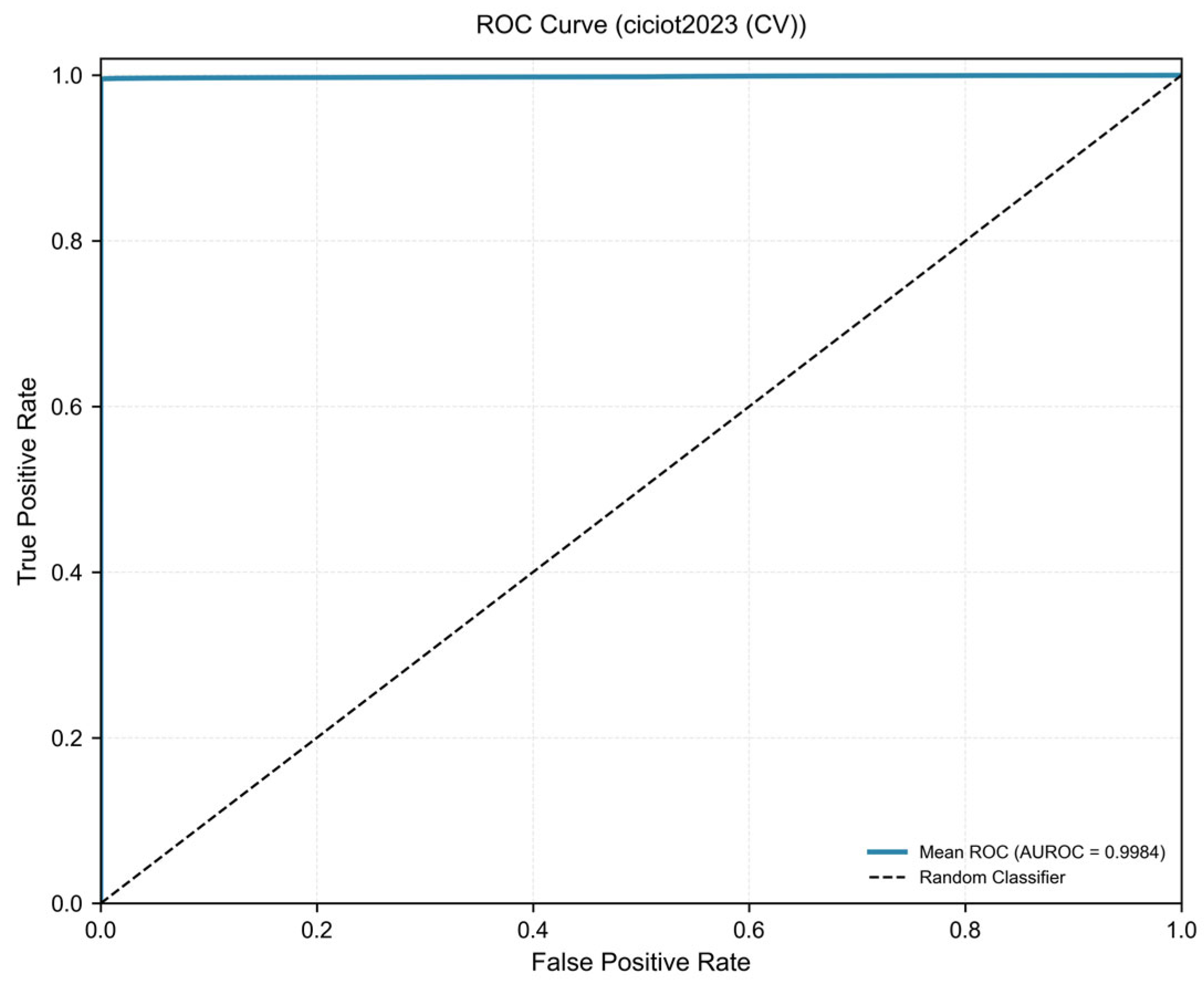

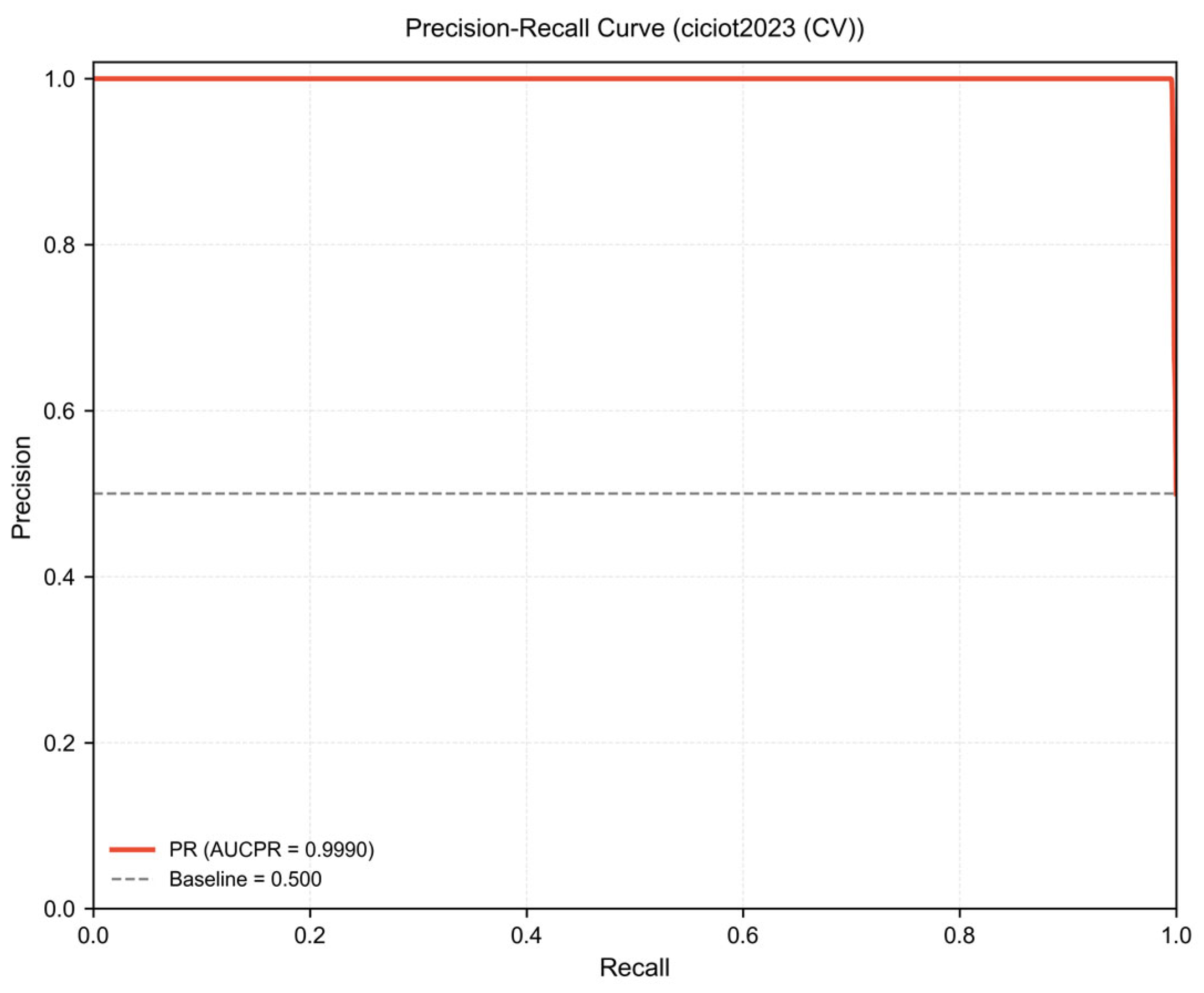

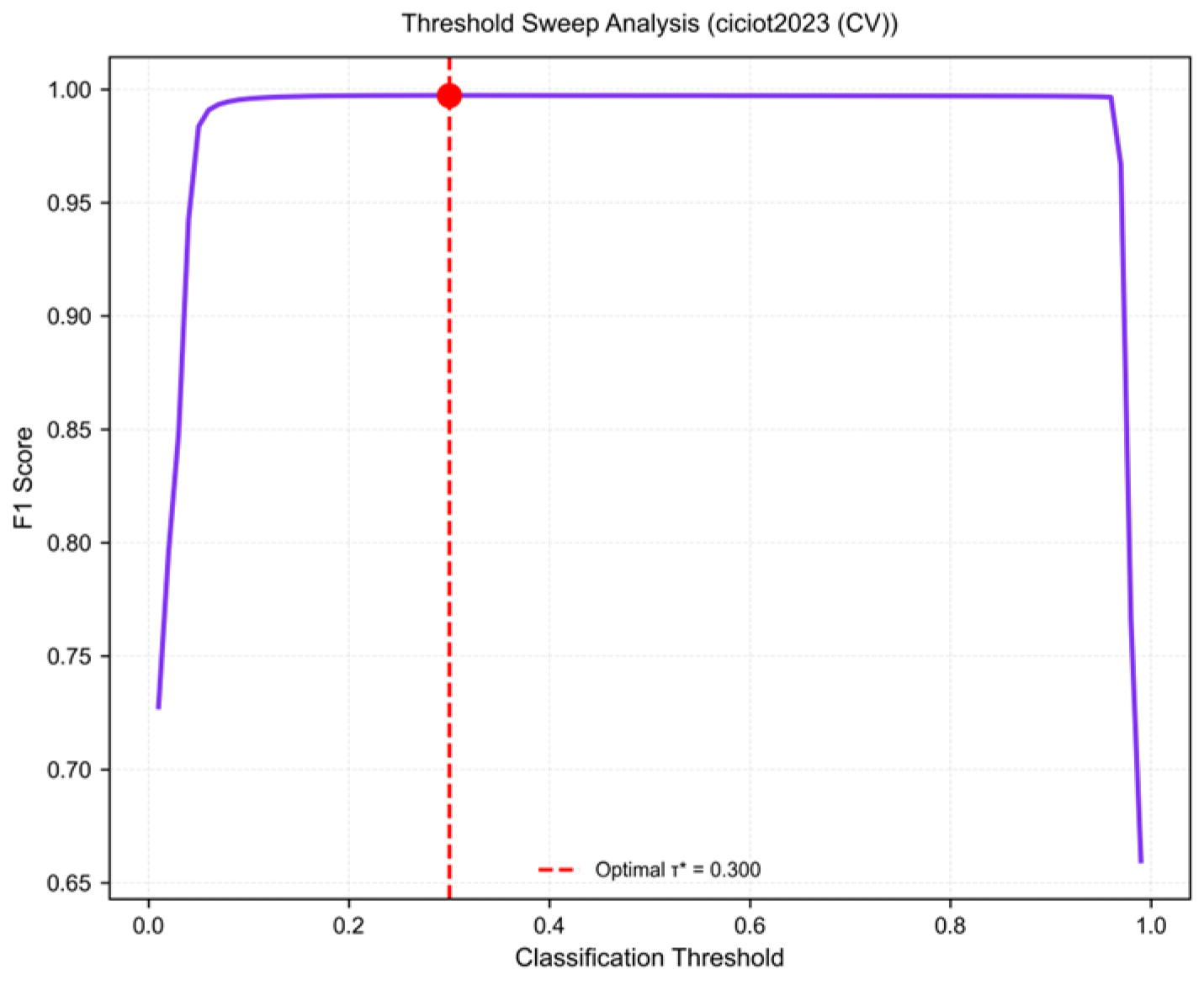

3.2. Cross-Validation Results on CICIoT2023

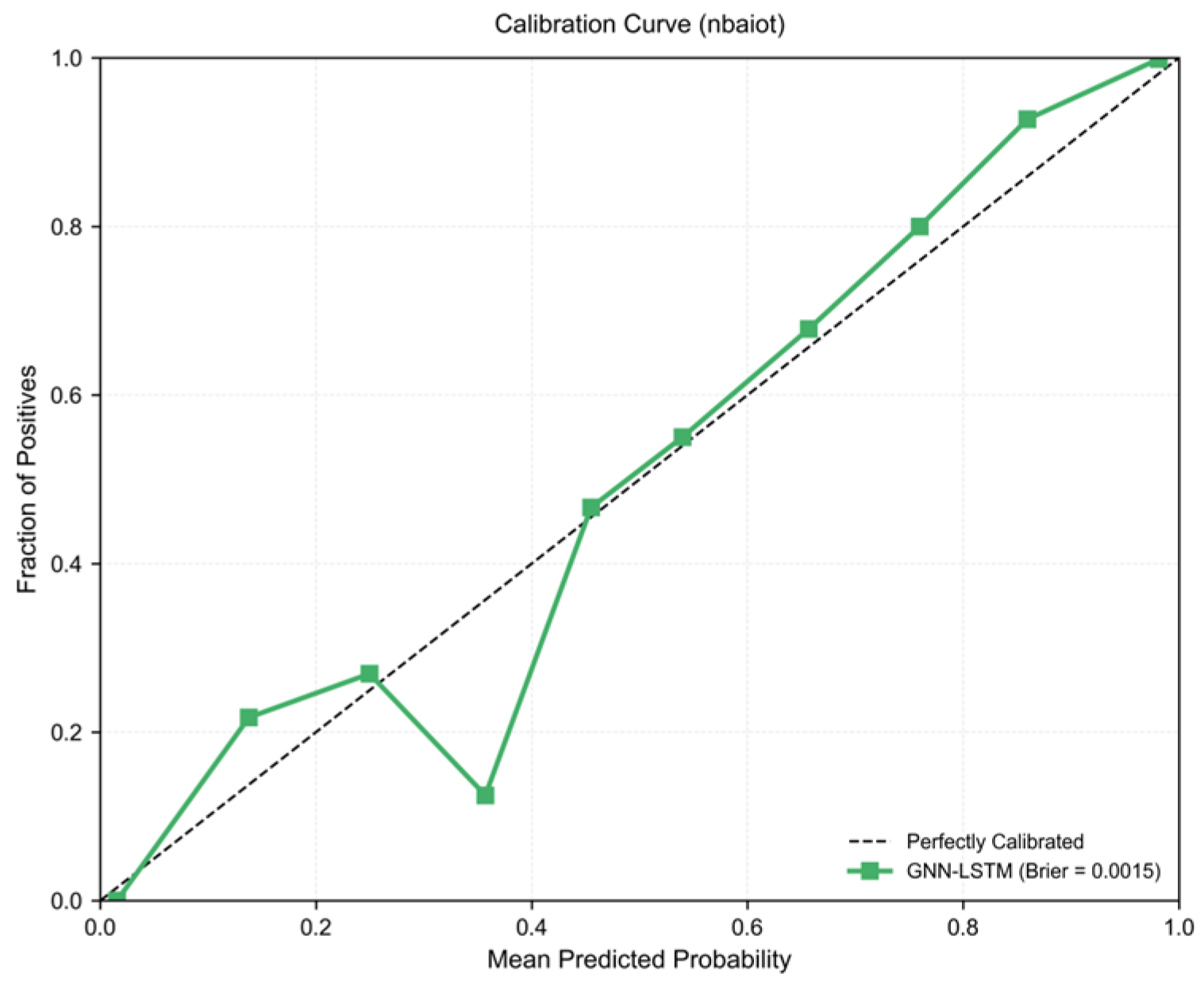

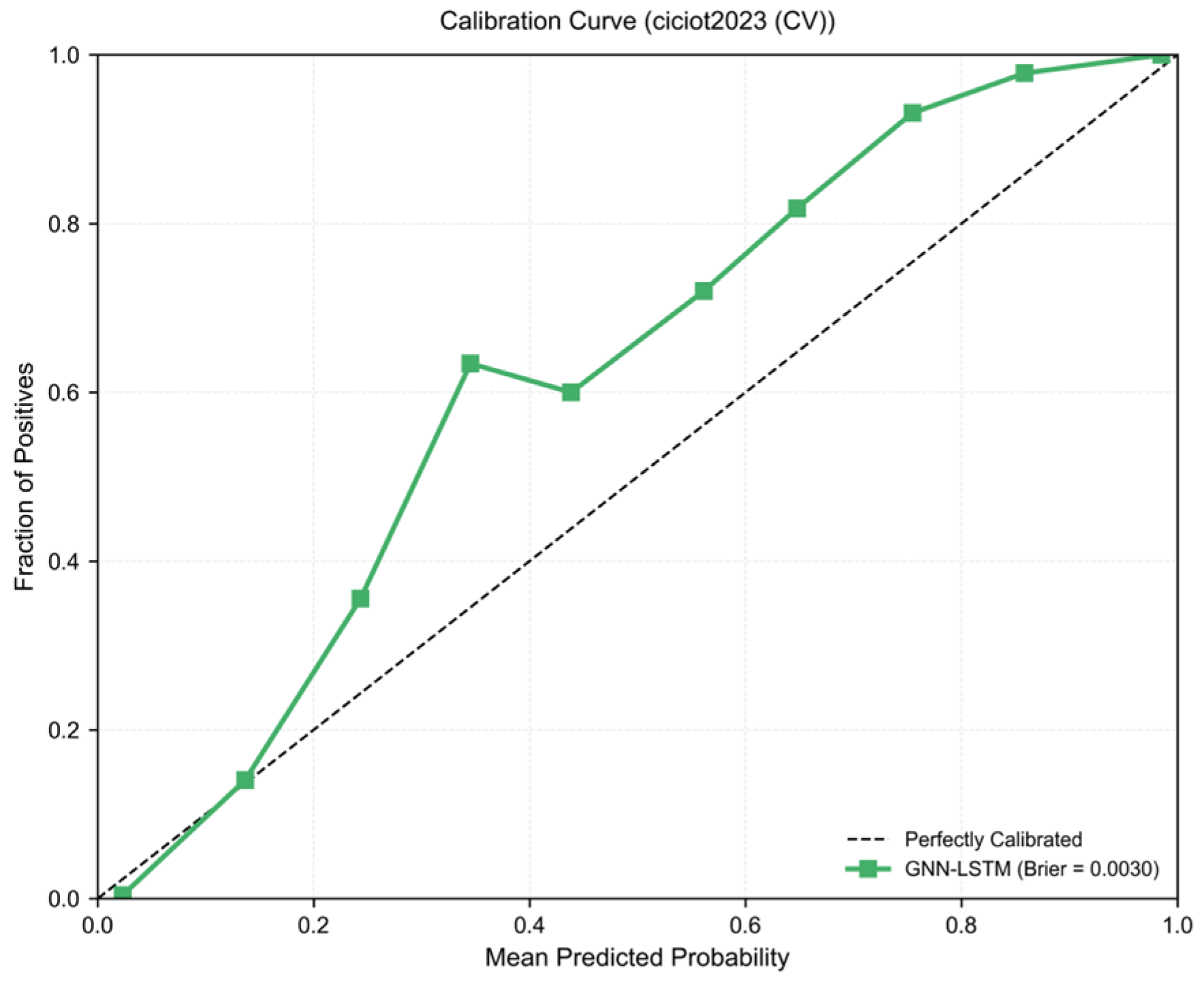

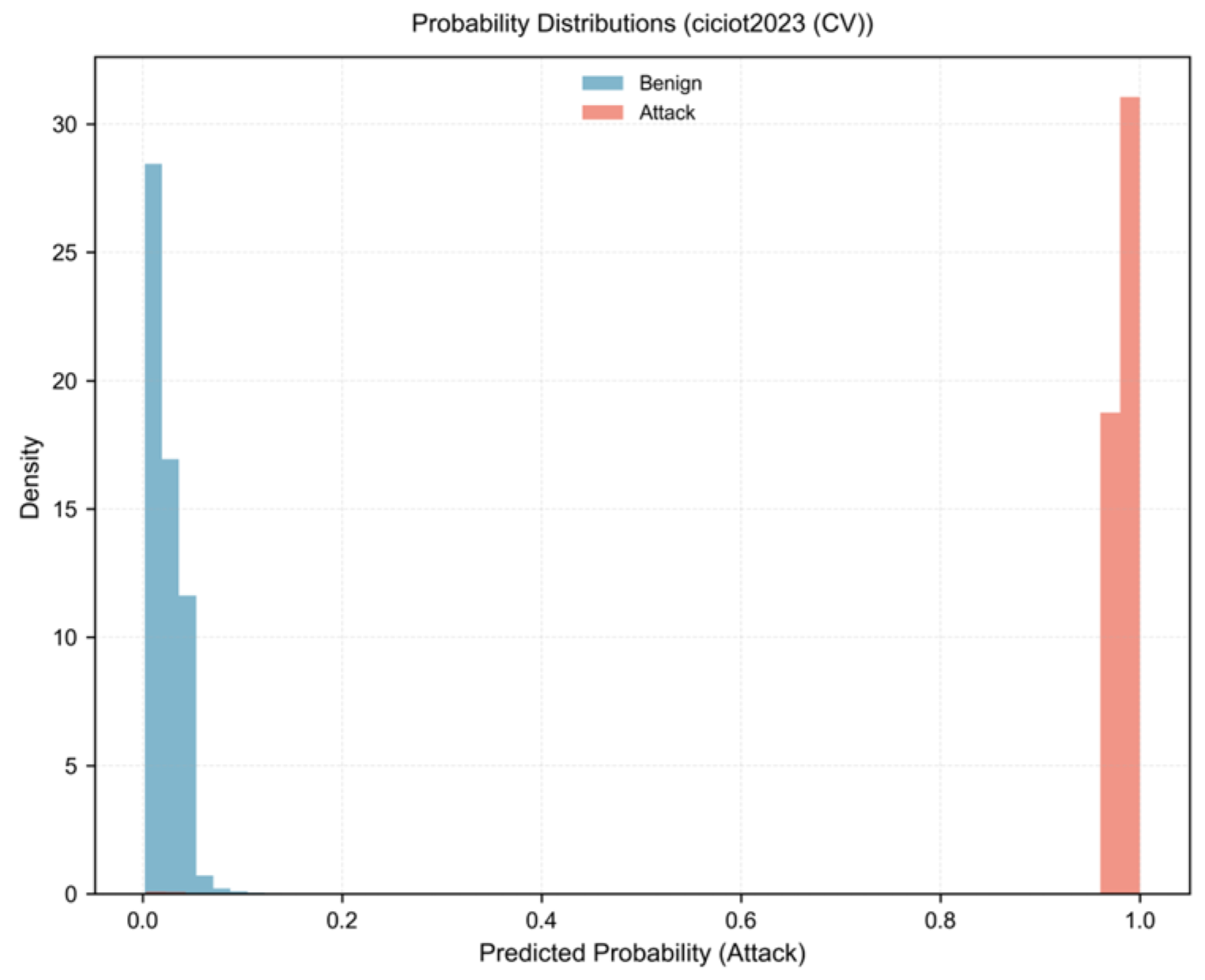

3.3. Probability Calibration Analysis

3.4. Cross-Dataset Comparison and Generalization Assessment

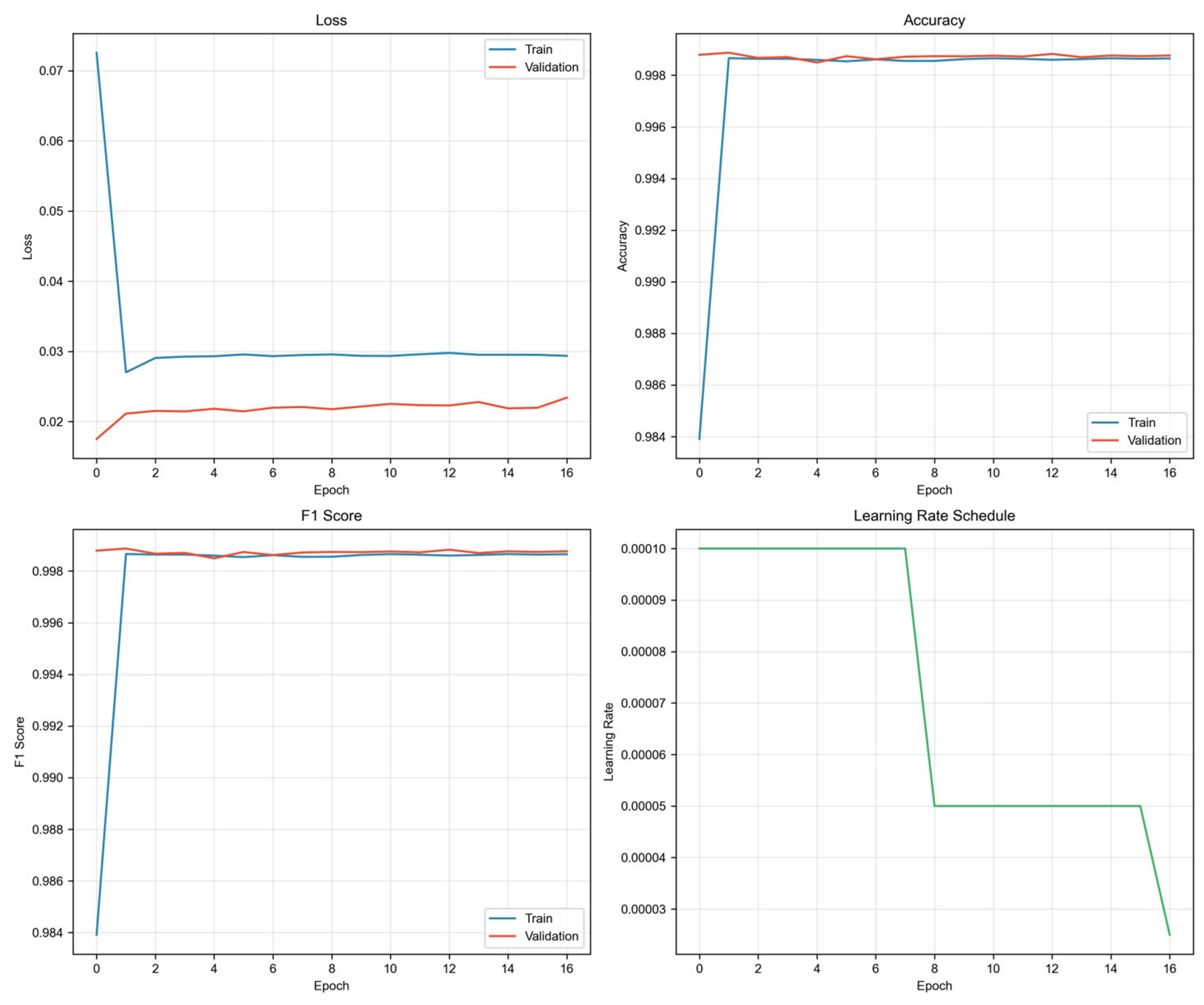

3.5. Training Dynamics and Convergence Analysis

3.6. Summary of Experimental Findings

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Primary Findings

4.2. Comparison with Prior Approaches

4.3. Calibration and Operational Implications

4.4. Generalization and the Dataset Shift Problem

4.5. Limitations

4.6. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| FN | False Negative |

| FP | False Positive |

| GNN | Graph Neural Network |

| IDS | Intrusion Detection System |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| MCC | Matthews Correlation Coefficient |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| PR | Precision–Recall |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| TN | True Negative |

| TP | True Positive |

| TPR | True Positive Rate |

References

- Weber, R.H. Internet of Things—New Security and Privacy Challenges. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2010, 26, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaba, F.A.; Othman, M.; Hashem, I.A.T.; Alotaibi, F. Internet of Things security: A survey. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2017, 88, 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertino, E.; Islam, N. Botnets and Internet of Things Security. Computer 2017, 50, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonakakis, M.; April, T.; Bailey, M.; Bernhard, M.; Burber, E.; Cochran, J.; Durumeric, Z.; Halderman, J.A.; Invernizzi, L.; Kallitsis, M.; et al. Understanding the Mirai Botnet. In Proceedings of the 26th USENIX Security Symposium, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 16–18 August 2017; pp. 1093–1110. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/220a7eed5c859f596a0d9dbc194034d170a6af51 (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Kolias, C.; Kambourakis, G.; Stavrou, A.; Voas, J. DDoS in the IoT: Mirai and Other Botnets. Computer 2017, 50, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miettinen, M.; Marchal, S.; Hafeez, I.; Asokan, N.; Sadeghi, A.R.; Tarkoma, S. IoT SENTINEL: Automated Device-Type Identification for Security Enforcement in IoT. In Proceedings of the IEEE 37th International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems (ICDCS), Atlanta, GA, USA, 5–8 June 2017; pp. 2177–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roesch, M. Snort: Lightweight Intrusion Detection for Networks. In Proceedings of the 13th USENIX Conference on System Administration (LISA), Seattle, WA, USA, 7–12 November 1999; pp. 229–238. [Google Scholar]

- Chandola, V.; Banerjee, A.; Kumar, V. Anomaly Detection: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2009, 41, 1–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buczak, A.L.; Guven, E. A Survey of Data Mining and Machine Learning Methods for Cyber Security Intrusion Detection. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2016, 18, 1153–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khraisat, A.; Gondal, I.; Vamplew, P.; Kamruzzaman, J. Survey of Intrusion Detection Systems: Techniques, Datasets and Challenges. Cybersecurity 2019, 2, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipf, T.N.; Welling, M. Semi-Supervised Classification with Graph Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Toulon, France, 24–26 April 2017; Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1609.02907 (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Hamilton, W.L.; Ying, R.; Leskovec, J. Inductive Representation Learning on Large Graphs. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 1025–1035. Available online: https://papers.nips.cc/paper/6703-inductive-representation-learning-on-large-graphs (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J. Deep Graph Embedding for IoT Botnet Traffic Detection. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2023, 2023, 9796912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibi, I.; Özçelebi, T.; Meratnia, N. An IoT Attack Detection Framework Leveraging Graph Neural Networks. In Intelligence of Things: Technologies and Applications; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, A.M.S.E. Leveraging Graph Neural Networks for Botnet Detection. In Advanced Engineering, Technology and Applications; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Xu, Z.; Rush, A.M.; Yu, M. Efficient Large-Scale IoT Botnet Detection through GraphSAINT-Based Subgraph Sampling and Graph Isomorphism Network. Mathematics 2024, 12, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Thu, H.L.T.; Kim, H. Long Short Term Memory Recurrent Neural Network Classifier for Intrusion Detection. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Platform Technology and Service (PlatCon), Jeju, Republic of Korea, 15–17 February 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkahtani, H.; Aldhyani, T.H.H. An Intrusion Detection System to Advance Internet of Things Infrastructure Based on Deep Learning Algorithms. Complexity 2021, 2021, 5579851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, P.; Sahu, D.; Prakash, S.; Yang, T.; Rathore, R.S.; Pandey, V.K. A High Performance Hybrid LSTM-CNN Secure Architecture for IoT Environments Using Deep Learning. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayegh, H.R.; Dong, W.; Al-madani, A.M. Enhanced Intrusion Detection with LSTM-Based Model, Feature Selection, and SMOTE for Imbalanced Data. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, B.; Azmoodeh, A.; Dehghantanha, A.; Srivastava, G.; Karimipour, H.; Lin, J.C.W. A GNN-Based Adversarial Internet of Things Malware Detection Framework for Critical Infrastructure: Studying Gafgyt, Mirai and Tsunami Campaigns. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 8468–8479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, G.; Lv, H.; Wang, H.; Feng, G. Application of a Dynamic Line Graph Neural Network for Intrusion Detection with Semi-Supervised Learning. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2023, 18, 699–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitulyova, Y.; Babenko, T.; Kolesnikova, K.; Kiktev, N.; Abramkina, O. A Hybrid Approach Using Graph Neural Networks and LSTM for Attack Vector Reconstruction. Computers 2025, 14, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friji, H.; Mavromatis, I.; Sanchez-Mompo, A.; Carnelli, P.; Olivereau, A.; Khan, A. Multi-Stage Attack Detection and Prediction Using Graph Neural Networks: An IoT Feasibility Study. In Proceedings of the IEEE 22nd International Conference on Trust, Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications (TrustCom), Exeter, UK, 1–3 November 2023; pp. 1584–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meidan, Y.; Bohadana, M.; Mathov, Y.; Mirsky, Y.; Shabtai, A.; Breitenbacher, D.; Elovici, Y. N-BaIoT: Network-Based Detection of IoT Botnet Attacks Using Deep Autoencoders. IEEE Pervasive Comput. 2018, 17, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Akhras, M.; Alshunaybir, A.; Omar, H.; Alhazmi, S. Botnet attacks detection in IoT environment using machine learning techniques. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2023, 7, 1683–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nour, M.; Atya, A.O.; Ghali, N.I.; El-Gazar, S.M. Intelligent Detection of IoT Botnets Using Machine Learning and Deep Learning. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Shorman, A.; Faris, H.; Aljarah, I. Unsupervised Intelligent System Based on One Class Support Vector Machine and Grey Wolf Optimization for IoT Botnet Detection. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2020, 11, 2809–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasongo, S.M.; Sun, Y. Performance Analysis of Intrusion Detection Systems Using a Feature Selection Method on the UNSW-NB15 Dataset. J. Big Data 2020, 7, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Pleiss, G.; Sun, Y.; Weinberger, K.Q. On Calibration of Modern Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Sydney, Australia, 6–11 August 2017; pp. 1321–1330. Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.5555/3305381.3305518 (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Brier, G.W. Verification of Forecasts Expressed in Terms of Probability. Mon. Weather Rev. 1950, 78, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babenko, T.; Kolesnikova, K.; Abramkina, O.; Vitulyova, Y. Automated OSINT Techniques for Digital Asset Discovery and Cyber Risk Assessment. Computers 2025, 14, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olekh, H.; Kolesnikova, K.; Olekh, T.; Mezenceva, O. Environmental impact assessment procedure as the implementation of the value approach in environmental projects. In CEUR Workshop Proceedings; CEUR-WS.org: Aachen, Germany, 2021; Volume 2870, pp. 1–10. Available online: https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2870/ (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Neto, E.C.P.; Dadkhah, S.; Ferber, R.; Zohourian, A.; Lu, R.; Ghorbani, A.A. CICIoT2023: A Real-Time Dataset and Benchmark for Large-Scale Attacks in IoT Environment. Sensors 2023, 23, 5941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadkhah, S.; Mahdikhani, H.; Danber, P.K.; Ghorbani, A.A. Towards the Development of a Realistic Multidimensional IoT Profiling Dataset. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Privacy, Security and Trust (PST), Fredericton, NB, Canada, 22–24 August 2022; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babenko, T.; Toliupa, S.; Kovalova, Y. LVQ models of DDOS attacks identification. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Advanced Trends in Radioelectronics, Telecommunications and Computer Engineering (TCSET), Lviv-Slavske, Ukraine, 20–24 February 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hnatiienko, H.; Hnatiienko, V.; Zulunov, R.; Babenko, T.; Myrutenko, L. Method for determining the level of criticality elements when ensuring the functional stability of the system based on role analysis of elements. In CEUR Workshop Proceedings; CEUR-WS.org: Aachen, Germany, 2024; Available online: https://ceur-ws.org/ (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Grechko, V.; Babenko, T.; Myrutenko, L. Secure software developing recommendations. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Scientific-Practical Conference: Problems of Infocommunications Science and Technology (PIC S&T), Kyiv, Ukraine, 8–11 October 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babenko, T.; Kolesnikova, K.; Panchenko, M.; Meish, Y.; Mazurchuk, P. Risk assessment of cryptojacking attacks on endpoint systems: Threats to sustainable digital agriculture. Sustainability 2025, 17, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. PyTorch: An Imperative Style, High-Performance Deep Learning Library. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; Volume 32, pp. 8024–8035. Available online: https://papers.neurips.cc/paper/9015-pytorch-an-imperative-style-high-performance-deep-learning-library.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), San Diego, CA, USA, 7–9 May 2015; Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1412.6980.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Raschka, S. Model Evaluation, Model Selection, and Algorithm Selection in Machine Learning. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1811.12808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Pan, S.; Chen, F.; Long, G.; Zhang, C.; Yu, P.S. A Comprehensive Survey on Graph Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 32, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelsson, S. The Base-Rate Fallacy and the Difficulty of Intrusion Detection. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. Secur. 2000, 3, 186–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.M.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. Survey on Deep Learning with Class Imbalance. J. Big Data 2019, 6, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, R.; Paxson, V. Outside the Closed World: On Using Machine Learning for Network Intrusion Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (S&P), Oakland, CA, USA, 16–19 May 2010; pp. 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanley, J.A.; McNeil, B.J. The Meaning and Use of the Area under a Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curve. Radiology 1982, 143, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Wu, M.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, Y. Network Intrusion Detection Based on Graph Neural Network and Ensemble Learning. In Proceedings of the 2023 CAA Symposium on Fault Detection, Supervision and Safety for Technical Processes (SAFEPROCESS), Yibin, China, 22–24 September 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.; Goadrich, M. The Relationship between Precision-Recall and ROC Curves. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 25–29 June 2006; pp. 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiñonero-Candela, J.; Sugiyama, M.; Schwaighofer, A.; Lawrence, N.D. (Eds.) Dataset Shift in Machine Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-262-17005-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, C.; Taylor, C. Challenging the Anomaly Detection Paradigm: A Provocative Discussion. In Proceedings of the 15th New Security Paradigms Workshop (NSPW), Schloss Dagstuhl, Germany, 19–22 September 2006; pp. 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Hu, W.; Leskovec, J.; Jegelka, S. How Powerful Are Graph Neural Networks? In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 6–9 May 2019; Available online: https://cs.stanford.edu/people/jure/pubs/gin-iclr19.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Flach, P. Performance Evaluation in Machine Learning: The Good, the Bad, the Ugly, and the Way Forward. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI), Honolulu, HI, USA, 27 January–1 February 2019; Volume 33, pp. 9808–9814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niculescu-Mizil, A.; Caruana, R. Predicting Good Probabilities with Supervised Learning. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Bonn, Germany, 7–11 August 2005; pp. 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, C.M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-387-31073-2. [Google Scholar]

- Pearl, J. Probabilistic Reasoning in Intelligent Systems: Networks of Plausible Inference; Morgan Kaufmann: San Mateo, CA, USA, 1988; ISBN 978-1-55860-479-7. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, G.; Calderwood, R.; Clinton-Cirocco, A. Rapid Decision Making on the Fire Ground. Proc. Hum. Factors Soc. Annu. Meet. 1986, 30, 576–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchins, E.M.; Cloppert, M.J.; Amin, R.M. Intelligence-Driven Computer Network Defense Informed by Analysis of Adversary Campaigns and Intrusion Kill Chains. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Information Warfare and Security (ICIW), Washington, DC, USA, 17–18 March 2011; pp. 113–125. Available online: https://www.lockheedmartin.com/content/dam/lockheed-martin/rms/documents/cyber/LM-White-Paper-Intel-Driven-Defense.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep Learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staniford, S.; Paxson, V.; Weaver, N. How to Own the Internet in Your Spare Time. In Proceedings of the 11th USENIX Security Symposium, San Francisco, CA, USA, 5–9 August 2002; pp. 149–167. Available online: https://www.usenix.org/conference/11th-usenix-security-symposium/how-own-internet-your-spare-time (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Plohmann, D.; Yakdan, K.; Klatt, M.; Bader, J.; Gerhards-Padilla, E. A Comprehensive Measurement Study of Domain Generating Malware. In Proceedings of the 25th USENIX Security Symposium, Austin, TX, USA, 10–12 August 2016; pp. 263–278. Available online: https://www.usenix.org/conference/usenixsecurity16/technical-sessions/presentation/plohmann (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD), San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masters, D.; Luschi, C. Revisiting Small Batch Training for Deep Neural Networks. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.07612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gal, Y.; Ghahramani, Z. Dropout as a Bayesian Approximation: Representing Model Uncertainty in Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), New York, NY, USA, 19–24 June 2016; pp. 1050–1059. Available online: https://proceedings.mlr.press/v48/gal16.html (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Bottou, L.; Bousquet, O. The Tradeoffs of Large Scale Learning. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 3–6 December 2007; Volume 20, pp. 161–168. Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2007/hash/0d3180d672e08b4c5312dcdafdf6ef36-Abstract.html (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Gordon, L.A.; Loeb, M.P. The Economics of Information Security Investment. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. Secur. 2002, 5, 438–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R. Why Information Security Is Hard: An Economic Perspective. In Proceedings of the 17th Annual Computer Security Applications Conference (ACSAC), New Orleans, LA, USA, 10–14 December 2001; pp. 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohaisen, A.; Alrawi, O. AMAL: High-Fidelity, Behavior-Based Automated Malware Analysis and Classification. In Information Security Applications (WISA 2014); Rhee, K.-H., Yi, J.H., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 9503, pp. 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.J.; Yang, Q. A Survey on Transfer Learning. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2010, 22, 1345–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, K.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M.; Wang, D. A Survey of Transfer Learning. J. Big Data 2016, 3, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zügner, D.; Akbarnejad, A.; Günnemann, S. Adversarial Attacks on Neural Networks for Graph Data. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining (KDD), London, UK, 19–23 August 2018; pp. 2847–2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlini, N.; Wagner, D. Towards Evaluating the Robustness of Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (S&P), San Jose, CA, USA, 22–24 May 2017; pp. 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, R.; Bourgeois, D.; You, J.; Zitnik, M.; Leskovec, J. GNNExplainer: Generating Explanations for Graph Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; Volume 32, pp. 9240–9251. Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2019/hash/d80b7040b773199015de6d3b4293c8ff-Abstract.html (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Chen, J.; Ma, T.; Xiao, C. FastGCN: Fast Learning with Graph Convolutional Networks via Importance Sampling. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 April–3 May 2018; Available online: https://openreview.net/forum?id=rytstxWAW (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Kerschbaumer, C.; Braun, F.; Friedberger, S.; Jürgens, M. The State of HTTPS Adoption on the Web. In Proceedings of the 2025 Workshop on Measurements, Attacks, and Defenses for the Web (MADWeb), San Francisco, CA, USA, 27 February 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherry, J.; Lan, C.; Popa, R.A.; Ratnasamy, S. BlindBox: Deep Packet Inspection over Encrypted Traffic. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGCOMM Conference, London, UK, 17–21 August 2015; Volume 45, pp. 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggio, B.; Roli, F. Wild Patterns: Ten Years After the Rise of Adversarial Machine Learning. Pattern Recognit. 2018, 84, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudin, C. Stop Explaining Black Box Machine Learning Models for High Stakes Decisions and Use Interpretable Models Instead. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2019, 1, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Device Type | Model | Benign Samples | Attack Samples | Traffic Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doorbell | Danmini | 49,548 | 1,842,674 | Event-driven bursts |

| Baby monitor | Philips B120N/10 | 175,240 | 1,925,150 | Continuous low-latency stream |

| Security camera | Provision PT-737E | 62,154 | 869,306 | Periodic heartbeat, motion-triggered |

| Security camera | Provision PT-838 | 98,514 | 932,446 | HD streaming, bandwidth-intensive |

| Webcam | SimpleHome XCS7-100 | 246,585 | 524,656 | Variable bitrate, adaptive quality |

| Webcam | SimpleHome XCS7-100 | 319,528 | 359,872 | Fixed intervals, predictable pattern |

| Thermostat | Ecobee | 13,113 | 806,886 | Sparse status updates |

| Socket | Edimax SP-2101W | 8135 | 385,949 | Command-response, binary states |

| Motion sensor | Samsung SNH-1011N | 52,150 | 615,028 | Event detection, alert propagation |

| Attack Category | Attack Types Included | Sample Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| DDoS | ACK Fragmentation, UDP Flood, SYN Flood, ICMP Flood, HTTP Flood, SlowLoris, TCP Flood, PSHACK Flood, RSTFIN Flood, UDP Fragmentation, ICMP Fragmentation, Synonymous IP Flood | 28,534,126 | 60.7% |

| DoS | TCP Flood, UDP Flood, HTTP Flood | 6,823,417 | 14.5% |

| Mirai | Greip Flood, Greeth Flood, UDPPlain | 4,912,553 | 10.4% |

| Reconnaissance | Host Discovery, Port Scanning, OS Fingerprinting, Vulnerability Scanning | 3,245,891 | 6.9% |

| Spoofing | ARP Spoofing, DNS Spoofing | 1,823,445 | 3.9% |

| Web-based | SQL Injection, Command Injection, XSS, Browser Hijacking, Backdoor Malware | 1,156,234 | 2.5% |

| Brute Force | Dictionary Attack | 478,923 | 1.0% |

| Total attack | — | 46,974,589 | 100% |

| Benign | Normal traffic from 105 devices | 1,035,721 | — |

| Parameter | N-BaIoT | CICIoT2023 |

|---|---|---|

| Total samples used | 1,000,000 | 400,000 |

| Samples per class | 500,000 | 200,000 |

| Number of features | 115 | 39 |

| Number of devices | 9 | 105 |

| Number of attack types | 10 | 33 |

| Collection year | 2018 | 2023 |

| Training samples | 700,000 | 272,000 per fold |

| Validation samples | 150,000 | 48,000 per fold |

| Test samples | 150,000 | 80,000 per fold |

| Evaluation method | Single stratified split | 5-fold stratified CV |

| Sequence length (T) | 24 | 24 |

| Batch size | 128 | 128 |

| Component | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| GNN Layer 1 | Input/Output Dimensions | 115 → 64 |

| GNN Layer 1 | Activation Function | ReLU + Batch Norm |

| GNN Layer 2 | Input/Output Dimensions | 64 → 64 |

| GNN Layer 2 | Dropout Rate | 0.4 |

| Graph Pooling | Aggregation Method | Global Mean Pool |

| LSTM | Hidden Units | 64 |

| LSTM | Number of Layers | 1 |

| LSTM | Sequence Length | 24 |

| Output Layer | Architecture | Linear (64 → 2) |

| Training | Optimizer | Adam (lr = 0.0001, weight_decay = 0.01) |

| Metric | Before Calibration | After Calibration | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expected Calibration Error | 0.038 | 0.012 | 68.4% |

| Brier Score | 0.0032 | 0.0015 | 53.1% |

| Log Loss | 0.0120 | 0.0058 | 51.7% |

| AUC-ROC | 0.9990 | 0.9995 | 0.05% |

| Mean Confidence Error | 0.042 | 0.018 | 57.1% |

| Metric | Value | Metric | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 99.88% | Specificity | 99.82% |

| Precision | 99.82% | False Positive Rate | 0.18% |

| Recall | 99.94% | False Negative Rate | 0.06% |

| F1-Score | 0.9988 | MCC | 0.9975 |

| AUROC | 0.9995 | Cohen’s Kappa | 0.9975 |

| Metric | Mean ± Std | 95% CI | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 99.73% ± 0.02% | 99.71–99.75% | 99.70–99.75% |

| Precision | 99.99% ± 0.01% | 99.98–100.00% | 99.98–100.00% |

| Recall | 99.46% ± 0.04% | 99.42–99.50% | 99.39–99.51% |

| Specificity | 99.99% ± 0.01% | 99.98–100.00% | 99.97–100.00% |

| F1-Score | 0.9972 ± 0.0002 | 0.9970–0.9974 | 0.9970–0.9975 |

| AUROC | 0.9984 ± 0.0002 | 0.9982–0.9986 | 0.9981–0.9985 |

| MCC | 0.9945 ± 0.0004 | 0.9941–0.9949 | 0.9939–0.9950 |

| Brier Score | 0.0030 ± 0.0002 | 0.0028–0.0032 | 0.0027–0.0032 |

| Fold | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 | AUROC | Brier |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 99.71% | 99.98% | 99.43% | 0.9971 | 0.9985 | 0.0031 |

| 2 | 99.75% | 99.99% | 99.51% | 0.9975 | 0.9985 | 0.0027 |

| 3 | 99.74% | 99.99% | 99.49% | 0.9974 | 0.9984 | 0.0029 |

| 4 | 99.70% | 100.00% | 99.39% | 0.9970 | 0.9981 | 0.0032 |

| 5 | 99.73% | 99.99% | 99.47% | 0.9973 | 0.9985 | 0.0029 |

| Metric | N-BaIoT | CICIoT2023 |

|---|---|---|

| Brier Score | 0.0015 | 0.0030 ± 0.0002 |

| AUROC | 0.9995 | 0.9984 ± 0.0002 |

| AUCPR | 0.9993 | 0.9990 ± 0.0001 |

| Expected Calibration Error | 0.012 | 0.018 ± 0.003 |

| Log Loss | 0.0058 | 0.0112 ± 0.0008 |

| Metric | N-BaIoT | CICIoT2023 | Δ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 99.88% | 99.73% | −0.15% |

| Precision | 99.82% | 99.99% | +0.17% |

| Recall | 99.94% | 99.46% | −0.48% |

| F1-Score | 0.9988 | 0.9972 | −0.0016 |

| AUROC | 0.9995 | 0.9984 | −0.0011 |

| Brier Score | 0.0015 | 0.0030 | +0.0015 |

| MCC | 0.9975 | 0.9945 | −0.0030 |

| Features | 115 | 39 | −66% |

| Device count | 9 | 105 | +1067% |

| Attack types | 10 | 33 | +230% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Babenko, T.; Kolesnikova, K.; Bakhtiyarova, Y.; Yeskendirova, D.; Sansyzbay, K.; Sysoyev, A.; Kruchinin, O. Hybrid GNN–LSTM Architecture for Probabilistic IoT Botnet Detection with Calibrated Risk Assessment. Computers 2026, 15, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers15010026

Babenko T, Kolesnikova K, Bakhtiyarova Y, Yeskendirova D, Sansyzbay K, Sysoyev A, Kruchinin O. Hybrid GNN–LSTM Architecture for Probabilistic IoT Botnet Detection with Calibrated Risk Assessment. Computers. 2026; 15(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers15010026

Chicago/Turabian StyleBabenko, Tetiana, Kateryna Kolesnikova, Yelena Bakhtiyarova, Damelya Yeskendirova, Kanibek Sansyzbay, Askar Sysoyev, and Oleksandr Kruchinin. 2026. "Hybrid GNN–LSTM Architecture for Probabilistic IoT Botnet Detection with Calibrated Risk Assessment" Computers 15, no. 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers15010026

APA StyleBabenko, T., Kolesnikova, K., Bakhtiyarova, Y., Yeskendirova, D., Sansyzbay, K., Sysoyev, A., & Kruchinin, O. (2026). Hybrid GNN–LSTM Architecture for Probabilistic IoT Botnet Detection with Calibrated Risk Assessment. Computers, 15(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers15010026