Abstract

We show that Out-of-Time-Ordered Correlator (OTOC) growth in the Quantum Kicked Rotor (QKR) quantifies information scrambling rather than entropy production. Numerical simulations reproduce the quadratic OTOC scaling at resonance () and its suppression under detuning. Bitstreams derived from the evolving wavefunction reveal a nonmonotonic relationship between chaos and entropy: the resonant (maximally chaotic) regime exhibits lower measured entropy due to coherent phase correlations, whereas slight detuning enhances statistical uniformity. While Out-of-Time-Ordered Correlators quantify information scrambling rather than entropy production, we show that the strength of scrambling strongly constrains the amount of classical entropy that can be extracted after measurement.

1. Introduction

High-quality randomness is a foundational requirement for modern cryptography [1], secure communication, and large-scale simulation. The unpredictability of random sequences directly impacts the security of symmetric keys, initialization vectors, and nonces in post-quantum settings [2]. Traditional pseudo-random number generators (PRNGs), although computationally efficient, suffer from periodicity, parameter degeneracy, and structural correlations at finite precision [3]. Chaos-based PRNGs alleviate some of these limitations by exploiting sensitivity to initial conditions [4,5], but they remain fundamentally deterministic and therefore vulnerable under high-precision or state-space reconstruction attacks.

Quantum systems provide a qualitatively different class of entropy sources. Measurement collapse produces intrinsically unpredictable outcomes, enabling the construction of quantum random number generators (QRNGs) with provable statistical guarantees [6,7,8]. However, standard QRNGs seldom incorporate microphysical diagnostics of quantum chaos, and the relationship between information scrambling, as quantified by Out-of-Time-Ordered Correlators (OTOCs), and the extractable classical randomness used in cryptography remains poorly understood.

The Quantum Kicked Rotor (QKR) is a paradigmatic model for studying this relationship. Its classical limit exhibits unbounded diffusion and positive Lyapunov exponents [9], whereas quantum interference induces dynamical localization, suppressing transport and constraining phase-space exploration [10,11,12,13]. At special values of the effective Planck constant, notably , constructive interference restores ballistic spreading and yields the resonant regime of the QKR. Recent theoretical developments show that the momentum and translation OTOCs of the QKR exhibit a universal quadratic growth at resonance [14], representing maximally allowed operator spreading within its Floquet structure. Semiclassical analyses further clarify how this growth arises from bounded Lyapunov instability in kicked systems [15]. These results position the QKR as an ideal platform for probing quantum scrambling in a controlled, tunable setting.

A crucial conceptual distinction motivates this work, the difference between scrambling and entropy production. In classical systems, chaotic divergence directly produces coarse-grained entropy through irreversible mixing. In contrast, unitary quantum dynamics conserve global von Neumann entropy [16]; thus, quantum chaos manifests not as entropy production, but as nonlocal information redistribution (scrambling). Consequently, a quantum system may exhibit strong OTOC growth while still generating measurement outcomes with non-uniform or low classical entropy. Therefore, The quality of randomness available for cryptographic use depends not solely on the degree of quantum scrambling, but on how well measurement and post-processing extract entropy from the underlying dynamics.

Bridging these perspectives, this work establishes a quantitative connection between operator scrambling in the QKR and the statistical quality of bitstreams derived from its momentum-space phases. We show that the resonant QKR, despite exhibiting maximal OTOC growth, retains coherent phase structures that reduce blockwise min-entropy, whereas slight detuning suppresses long-range coherence and improves statistical uniformity. To obtain cryptographically usable randomness, we employ Toeplitz hashing [17] and SHAKE–256 extraction, which provably convert weak, biased, or correlated sequences into near-uniform outputs.

The present work makes four main contributions:

- We numerically verify the quadratic OTOC scaling of the QKR at resonance and demonstrate its controlled suppression under small detuning, in agreement with analytic theory [14].

- We show that maximal operator scrambling does not correspond to maximal classical entropy; instead, detuned QKR dynamics yield higher extractable entropy due to reduced coherence.

- We quantify extraction efficiency using min-entropy density and demonstrate that detuning increases usable randomness by more than 20% relative to resonance.

- We integrate the extracted sequences into a standardized permutation–diffusion cipher and benchmark them against state-of-the-art classical chaotic RNGs [18,19], demonstrating competitive or superior cryptographic diffusion and randomness performance.

Through this synthesis of quantum chaos diagnostics, entropy analysis, randomness extraction, and cryptographic benchmarking, our study clarifies how quantum-chaotic dynamics can serve as tunable, physically grounded entropy sources for post-quantum cryptographic applications.

2. Quantum Kicked Rotor and OTOC Theory

2.1. Quantum Kicked Rotor (QKR)

The QKR is governed by the time-periodic Hamiltonian

where p and denote angular momentum and position, I the moment of inertia, K the kick strength, and T the kicking period. Classically, the kicked rotor exhibits chaotic diffusion and exponential sensitivity to initial conditions [9,10]. In contrast, in the quantum regime, interference leads to dynamical localization, halting energy diffusion and forming exponentially localized momentum states [11,12].

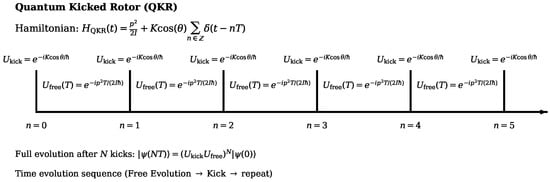

Resonant conditions occur when the effective Planck constant (with integers ) causes constructive interference between successive kicks. At exact resonance, the free-evolution phase factor becomes unity, suppressing dynamical localization and leading to ballistic energy growth . In this regime, the Out-of-Time-Ordered Correlator (OTOC) likewise exhibits quadratic growth, representing the maximum spread of correlations permitted by the periodic, unitary dynamics of the QKR. This resonant limit thus acts as a model-specific realization of ‘maximal quantum chaos’, analogous in spirit to the universal chaos bound proposed by Maldacena, Shenker & Stanford [20]. The alternating sequence of free evolution and periodic kicks defining the Quantum Kicked Rotor is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the Quantum Kicked Rotor (QKR) model showing alternating free evolution and periodic kicks.

2.2. Quantum Chaos, Scrambling, and Entropy

Classical chaos is characterized by exponential sensitivity to initial conditions, quantified by the Lyapunov exponent [9]. Such divergence generates irreversible mixing in phase space, producing coarse-grained entropy growth. In this setting, chaos and entropy production are tightly linked: chaotic systems literally create entropy through nonlinear stretching and folding of trajectories.

Quantum systems behave fundamentally differently. Time evolution under a Hamiltonian, , is unitary,

which preserves the spectrum of the density matrix. Consequently, the global von Neumann entropy,

is strictly conserved during closed quantum evolution, regardless of whether the dynamics are regular, localized, or quantum chaotic [16]. Thus, unlike in classical chaos, quantum chaotic systems do not produce entropy. Instead, quantum chaos manifests as the rapid redistribution of information across the Hilbert space, commonly termed scrambling.

In the absence of classical trajectories, quantum chaos is diagnosed through operator spreading rather than phase-space divergence. The Out-of-Time-Ordered Correlator (OTOC),

captures how the initially commuting operators A and B become increasingly non-commuting as evolves under the Heisenberg map. The OTOC thus quantifies the growth of operator complexity and sensitivity to perturbations, playing a role analogous to a quantum Lyapunov exponent [21,22,23,24].

For the Quantum Kicked Rotor (QKR), Li and Zhao [14] showed that the momentum and translation OTOCs grow quadratically, , under the resonant condition , reflecting ballistic operator spreading. Varikuti and Madhok [15] further demonstrated that quadratic growth in kicked systems arises from bounded semiclassical instability and provides a model-specific analogue of classical chaoticity. Under detuning, interference induces dynamical localization [10], suppressing operator growth and limiting scrambling.

Although the global von Neumann entropy is conserved, entanglement between subregions of the Hilbert space may change during evolution. By partitioning the QKR momentum basis into artificial subsystems (e.g., positive vs. negative momentum sectors), one may define the reduced density matrix and its entanglement entropy

This entropy serves as a proxy for information delocalization: resonant QKR dynamics rapidly entangle momentum sectors, while detuned dynamics remain weakly entangled due to localization. Related extensions of the kicked-rotor framework to interacting many-body systems show that quantum resonance can significantly accelerate entanglement growth and scrambling dynamics [25]. Importantly, reflects scrambling but is not a measure of cryptographic randomness.

The entropy relevant to cryptographic applications arises only after measurement. Projective measurement produces a classical distribution , whose Shannon entropy

depends solely on the number of classical outcomes (e.g., for 8-bit grayscale values) and not on the underlying Hilbert-space dimension. Thus, strong quantum scrambling (large OTOCs or entanglement) does not guarantee high classical entropy. In practice, weak or biased raw measurement outputs must be processed through extractors such as Toeplitz hashing [17] to obtain near-uniform, cryptographically secure bitstreams.

Quantum chaos controls the structure and spread of information but does not generate entropy. OTOCs measure scrambling; Shannon entropy measures classical randomness. Randomness extraction forms the bridge between these domains, linking the physical dynamics of the QKR to usable entropy in cryptographic applications.

2.3. Chaos Measures in Classical and Quantum Systems

In classical mechanics, chaos is quantified through the Lyapunov exponent:

which measures exponential divergence between nearby trajectories. A positive signifies strong chaos. However, quantum evolution is unitary, and phase-space trajectories are ill-defined, rendering Equation (7) unsuitable for direct application.

In classical systems, chaotic divergence directly increases coarse-grained entropy through irreversible mixing of trajectories. By contrast, the unitary evolution of quantum systems such as the QKR conserves the von Neumann entropy . Hence, quantum chaos does not create entropy; it redistributes information non-locally through operator spreading, a process known as scrambling. OTOCs therefore quantify the rate of scrambling, not thermodynamic entropy growth. This conceptual separation underlies the empirical observation that maximal chaos in the QKR need not correspond to maximal randomness in measurement outcomes.

The link between classical Lyapunov instability and quantum operator spreading has been treated in a unified semiclassical framework by Varikuti et al. [15]. Their analysis showed that Out-of-Time-Ordered Correlators in kicked systems, including the QKR and the kicked top, display either exponential or quadratic growth depending on the magnitude of the underlying classical Lyapunov exponent and on the operator choice. This formulation provides the theoretical basis for interpreting the QKR’s quadratic OTOC regime as the quantum analogue of bounded classical chaos.

Quantum analogues rely on operator growth rather than trajectory divergence. The OTOC provides a universal probe for this behavior, measuring the non-commutativity of two initially commuting operators under time evolution:

In the early-time regime, , where plays a role analogous to the classical Lyapunov exponent.

2.4. Out-of-Time-Order Correlators (OTOCs)

The OTOC quantifies information scrambling and operator spreading [21,22]. For the QKR, two forms are used:

where is a small-angle translation operator. At resonance (), Li and Zhao [14] derived

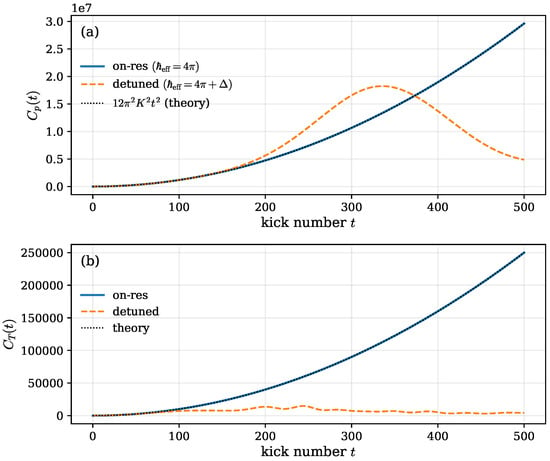

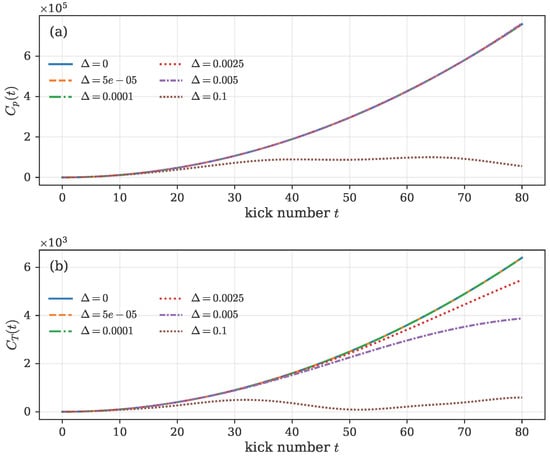

These expressions serve as validation benchmarks for our numerical simulations, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

(a) Momentum-operator OTOC and (b) translation OTOC for the Quantum Kicked Rotor (QKR) under on-resonant () and slightly detuned () conditions. Solid and dashed lines denote numerical data, while dotted black curves indicate the theoretical quadratic dependence predicted for resonant evolution. The suppression of unbounded growth for finite demonstrates the transition from ballistic to dynamically localized quantum scrambling.

2.5. Related Work

Out-of-Time-Ordered Correlators (OTOCs) have emerged as a rigorous quantitative probe of quantum chaos, measuring the degree of non-commutativity between initially commuting operators and thereby quantifying information scrambling in isolated many-body systems [21,22,23]. For periodically driven systems such as the Quantum Kicked Rotor (QKR), Li and Zhao [14] derived closed-form expressions for the momentum and translation OTOCs, showing a quadratic scaling at quantum resonance (). Varikuti et al. [15] further demonstrated, through semiclassical analysis of coupled kicked tops, that quadratic OTOC growth corresponds to bounded operator spreading governed by finite Lyapunov exponents. These studies collectively establish the QKR as a paradigmatic platform for analyzing quantum chaos through operator dynamics rather than classical trajectory divergence.

Parallel advances in QRNG have focused on measurement-induced entropy and device-independent certification of unpredictability from fundamental quantum indeterminacy [1,7,8]. While such approaches yield provably random bitstreams, they seldom connect microscopic scrambling processes to macroscopic entropy rates. Theoretical treatments of quantum entropy production generally emphasize von Neumann or Shannon entropy under decoherence, leaving the link between dynamical chaos—quantified by OTOCs—and extractable randomness largely unexplored.

In contrast, chaos-based cryptography relies on deterministic nonlinear maps such as the logistic, Henon, and Duffing systems to realize pseudo-random generators for image or key encryption [26,27,28]. Although these schemes exploit sensitive dependence on initial conditions, their finite-precision implementations often introduce parameter degeneracy and periodic windows that degrade effective entropy. Quantum-chaotic analogues like the QKR can, in principle, overcome such limitations by generating complex, non-periodic phase distributions through unitary evolution. However, prior literature has not quantified how the degree of operator scrambling, as measured by OTOCs, translates into statistical entropy or post-processing efficiency using cryptographic extractors (e.g., Toeplitz hashing or SHAKE–256). Addressing this unexamined correspondence constitutes the central motivation of the present study.

Recent work by Wang and Robnik [29] offers an additional perspective by demonstrating a model-independent correspondence between quantum chaoticity and finite-time classical chaoticity. By comparing spectral statistics with finite-time classical indicators in driven systems such as the kicked top and Dicke model, they show that a quantum measure of chaoticity maps onto a finite-time classical measure through a universal relationship. This supports the view that short-time unitary dynamics can retain signatures of classical chaotic behavior in experimentally accessible observables.

In parallel, the development of quantum-enhanced cryptographic primitives confirms the demand for complex, physically grounded entropy. Recent work using single-qubit quantum logistic–sine rotational maps further demonstrates that quantum-chaotic dynamics can yield ultra-wide parameter spaces and strong cryptographic diffusion [30]. For instance, the Quantum Rotational Cross-Coupled 2D Map (QRC-2D) utilizes asymmetric, interdependent single-qubit rotations (RX, RY, RZ) to construct a hyperchaotic system that achieves practically infinite parameter control and significantly superior cryptographic performance (NPCR , Entropy ≈ 7.99) compared to classical chaotic generators [31]. This work’s successful implementation of quantum rotational logic as a core dynamic mechanism reinforces the necessity of understanding the quantum-to-classical entropy transition. Hybrid approaches combining quantum key distribution with high-dimensional hyperchaotic systems further highlight the growing intersection between quantum communication and chaos-based encryption [32].

Motivated by these developments, the present work uses the QKR as a physically grounded, tunable entropy source in which operator scrambling, quantified by OTOCs, can be directly correlated with statistical properties of extracted bitstreams. In particular, we exploit resonance and controlled detuning to vary the strength and character of scrambling, then examine how these changes affect min-entropy and post-processing efficiency. In this way, the study bridges theoretical diagnostics of quantum chaos (OTOCs, quantum-classical correspondence) and practical cryptographic evaluation (entropy, extraction efficiency, and image-encryption performance), clarifying how quantum-chaotic dynamics can be harnessed for post-quantum randomness generation rather than merely serving as abstract indicators of chaoticity.

3. Methodology

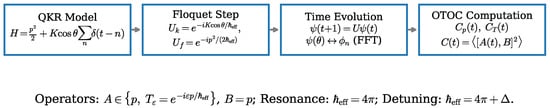

The objective of this work is to determine how quantum scrambling in the Quantum Kicked Rotor (QKR) influences the amount of extractable classical entropy and the subsequent quality of cryptographic keystreams. To answer this question, our methodology is organized into four components: controlled quantum-chaotic evolution, scrambling quantification via OTOCs, measurement-based randomness extraction, and cryptographic evaluation using a standardized permutation–diffusion cipher. An overview of the complete QKR simulation, scrambling analysis, and bit-extraction workflow is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of the QKR simulation and bit extraction pipeline.

3.1. QKR Simulation and Chaos Control

We begin by simulating the QKR under conditions that yield markedly different dynamical behaviors. The Floquet operator

governs one kick period, with K fixed and tuned to explore resonant () and detuned () regimes. A large discrete momentum basis of dimension enables efficient FFT-based transformations between angle and momentum representations. This choice guarantees that interference patterns—responsible for resonance and localization—emerge faithfully during numerical evolution.

Each simulation step uses the split-operator technique, alternating between angle- and momentum-space using forward and inverse FFTs. The technique ensures numerical unitarity, and we verify fidelity through forward–reverse roundtrip tests , requiring Frobenius deviation below . Such precision is necessary because scrambling indicators such as OTOCs are highly sensitive to numerical artifacts; inaccurate evolution can mimic or suppress chaos, leading to misinterpretation of results. The numerical implementation of the QKR using the split-operator FFT scheme is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Numerical simulation framework of the QKR using the split-operator (FFT) method for alternating momentum and angle bases.

It is worth noting the computational trade-off inherent in this approach. The split-operator method scales as per kick due to the forward and inverse FFT steps, which is computationally more intensive than the arithmetic operations typical of low-dimensional classical chaotic maps (e.g., Logistic or Tent maps). However, this complexity is a deliberate design feature rather than a limitation. In classical systems, finite-precision arithmetic often leads to dynamical degradation and short periodic orbits. In contrast, the QKR’s dynamics unfold in a Hilbert space of dimension N (here ), which effectively acts as a massive state space that resists phase-space reconstruction attacks. By strictly enforcing unitary evolution via high-precision FFTs, we ensure that the system avoids the parameter degeneracy and structural collapse often observed in simpler chaotic generators.

3.2. OTOC-Based Scrambling Measurement

To quantify the degree of scrambling, we compute Out-of-Time-Ordered Correlators (OTOCs), a widely used diagnostic of quantum chaos. For an operator pair , the OTOC

measures how the initially commuting operators fail to commute as evolves in the Heisenberg picture. Following the theoretical framework of [14], we use two pairs: , which probes momentum spreading, and , where is a small translation operator sensitive to fine phase-space structure.

OTOCs are computed up to kicks for each detuning value in a sweep . This enables a detailed comparison between ballistic, quadratic growth observed at resonance and the saturation behavior characteristic of dynamical localization. This step both validates theoretical predictions and provides a quantitative scrambling profile that directly informs the later entropy analysis: the strength and rate of scrambling determine how much information is delocalized before measurement.

3.3. Measurement-Based Randomness Extraction

To study how scrambling affects usable entropy, we extract classical bits from QKR momentum amplitudes after each kick. The complex amplitudes provide phase samples , which are mapped to binary values by evaluating the sign of a rotated sinusoid:

where introduces an irrational rotation that reduces periodic structure. This produces long, temporally ordered bitstreams whose statistical properties depend on underlying quantum dynamics.

After each kick, the quantum state is represented in the momentum basis as a set of complex amplitudes . The accessibility of such momentum-space information through measurement and reconstruction has been demonstrated experimentally in the kicked-rotor system [33]. Classical bitstreams are generated by extracting the phases and mapping them to binary values using a deterministic thresholding rule applied to a rotated sinusoidal function.

We evaluate several statistical indicators to quantify the quality of raw randomness: bit bias, 8-bit block min-entropy, autocorrelation, runs-test deviations, and windowed uniformity. These metrics reveal whether strong scrambling correlates with strong classical entropy—a relationship that turns out to be nontrivial due to the unitary nature of the QKR. Because raw measurement data often retain bias or correlations, we apply Toeplitz hashing and SHAKE–256 to produce near-uniform outputs. Extraction efficiency provides a quantitative measure of usable entropy, which becomes central in comparing resonant and detuned regimes.

3.4. Cryptographic Evaluation Using a Permutation–Diffusion Cipher

The final methodological component evaluates whether extracted randomness supports practical cryptographic tasks. To provide an application-level benchmark, we integrate the post-processed bitstreams into a standard permutation–diffusion image cipher. Permutation uses a Fisher–Yates shuffle driven by the keystream, ensuring that nearby pixels are spatially separated. Diffusion applies two key-dependent passes in forward and reverse directions, enforcing avalanche effects whereby a single-bit change propagates globally in the ciphertext.

We quantify cryptographic performance using widely accepted image-security metrics: entropy, uniformity, horizontal–vertical–diagonal pixel correlations, PSNR, SSIM, NPCR, and UACI. Because every RNG source—including classical chaotic maps and the QKR—is tested under the same cipher structure, this evaluation isolates the influence of the underlying randomness rather than the encryption design. This step addresses the final research goal: establishing whether differences in scrambling and extraction efficiency translate into measurable improvements in cryptographic performance.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. OTOC Verification and Detuning Analysis

This section validates the numerical computation of the Out-of-Time-Ordered Correlators (OTOCs) in the Quantum Kicked Rotor (QKR) against analytical predictions and examines how small detunings from resonance control the strength of operator scrambling.

The momentum and translation OTOCs, and , were computed using the split-operator FFT propagator. To validate the correctness of the numerical propagation and to ensure that all subsequent entropy analyses rest on a physically accurate basis, both correlators were benchmarked against the analytical expressions derived by Li and Zhao [14], which predict quadratic growth at quantum resonance :

We computed the OTOCs using a split-operator FFT propagator,

acting on a momentum-localized initial state . Norm preservation was monitored at every step through the Frobenius deviation , which remained below . We additionally verified numerical reversibility by performing a 20-kick forward–backward Loschmidt test, yielding a round-trip error of , confirming exact unitarity and eliminating numerical drift as a source of growth.

Least-squares fits of the simulated OTOCs to the model confirmed the analytic prefactors with machine-precision agreement: for the resonant case (), matches the theoretical , and equals the predicted . The residual errors (root-mean-squared error, RMSE) remain below for and for throughout the simulation window (), demonstrating quantitative reproduction of the expected quadratic scaling.

Spectral convergence with respect to the momentum-space truncation was verified by comparing trajectories for against the reference using an amplitude-normalized maximum relative error . The resulting deviations were at machine precision: () and () for , and () and () for . These results confirm full spectral convergence of the FFT implementation.

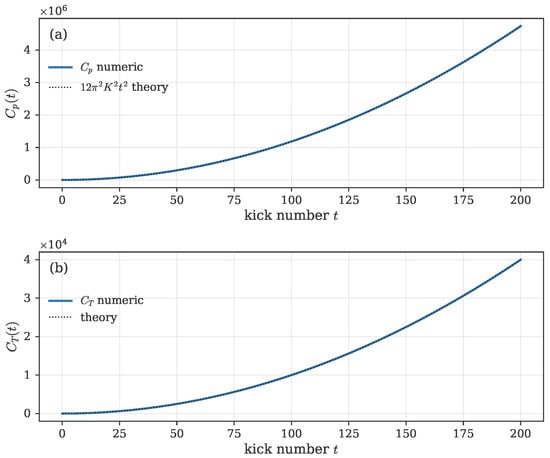

Figure 5 illustrates the overlap between numerical and analytical curves for both correlators. Insets show residuals , remaining within for and for . The detuned configuration () exhibits saturation at long times, consistent with dynamical localization and suppression of ballistic operator growth. This validation confirms the simulation’s numerical fidelity, which underpins the entropy analysis.

Figure 5.

Validation of Out-of-Time-Ordered Correlators (OTOCs) at quantum resonance (). (a) Momentum-operator OTOC and (b) translation–momentum OTOC . Solid lines denote numerical results obtained from the split-operator QKR simulation, while dotted black curves show the analytical quadratic dependence () predicted for resonant evolution. The excellent overlap confirms the correctness of the numerical implementation.

4.2. Detuning-Dependent Behavior of OTOCs

Beyond the resonant regime, we analyzed the response of the QKR OTOCs to small detunings from the resonant value . Figure 6 presents the normalized correlators and for , revealing a continuous crossover from ballistic to localized dynamics.

Figure 6.

Detuning sweep of OTOCs. (a) Momentum OTOC and (b) Translation–momentum OTOC . Quadratic growth at is progressively suppressed as detuning increases.

At exact resonance (), both correlators grow quadratically with time, reflecting unconstrained operator spreading and maximal quantum scrambling. As increases, constructive interference between Floquet phases is gradually destroyed, reducing the effective coupling between momentum modes. The growth of and begins to deviate from beyond a characteristic localization time , after which both correlators saturate. This saturation marks the onset of dynamical localization and bounded operator expansion—an intrinsically quantum phenomenon absent in classical chaotic rotors.

Quantitatively, the detuned curves maintain quadratic scaling up to for the present parameters (), after which and plateau at and , respectively. These values correspond to the steady-state limits seen in the convergence tests of Section 4.1, confirming that the observed saturation is physical rather than numerical. The detuning dependence of thus provides a quantitative knob to control operator scrambling strength, bridging the resonant, maximally chaotic regime and the localized, quasi-integrable regime central to the subsequent entropy-extraction analysis.

It is crucial to evolve the system beyond to ensure the dynamics have entered the saturation regime, which is distinct from the transient ballistic growth observed at early times ().

The influence of quantum resonance on operator growth was examined by computing the Out-of-Time-Ordered Correlators (OTOCs) and for the momentum and translation operators, respectively. Two regimes were compared: the exact resonant condition and a slightly detuned case with . The initial state was chosen as , following the convention of Li and Zhao, 2024 [14].

Figure 2 shows the numerical evolution of and along with the theoretical quadratic envelopes and , where and . The on-resonant curves closely follow the expected scaling, confirming the ballistic growth of correlations that defines the maximally chaotic regime of the QKR. In contrast, detuning introduces a gradual suppression of this unbounded growth, signaling the onset of dynamical localization.

Quantitatively, the detuned OTOCs exhibit an early-time behavior indistinguishable from the resonant case but deviate at later times, approaching a quasi-saturated regime. This transition is consistent with interference-induced phase decoherence that limits the spreading of operators in Hilbert space. Such behavior marks a crossover from the maximally chaotic condition (ballistic growth) to a moderately chaotic or localized regime with bounded correlations.

The results demonstrate that even a small deviation in effectively tunes the degree of information scrambling without altering the underlying Hamiltonian structure. This tunability establishes the QKR as an exemplary model for studying the correspondence between quantum chaos, operator growth, and entropy generation. The next subsection analyzes the statistical properties of bitstreams from these dynamical regimes.

4.3. Bitstream Statistical Results

Bitstreams were generated from the QKR phase dynamics under resonant () and slightly detuned () conditions. Each configuration produced raw bits. Table 1 summarizes the resulting statistical indicators, including proportion of ones, blockwise min-entropy, lag-1 autocorrelation, runs-test z-scores, and windowed deviation. All metrics were computed directly from the raw bitstreams; post-processed values using SHAKE–256 or Toeplitz hashing are reported for comparison where relevant.

Table 1.

Statistical metrics of QKR-derived bitstreams at on-resonant and detuned conditions. Bitstreams were generated by sampling the momentum-space phases and mapping them to binary values via the thresholding process described in Section 3.3 and Equation (13).

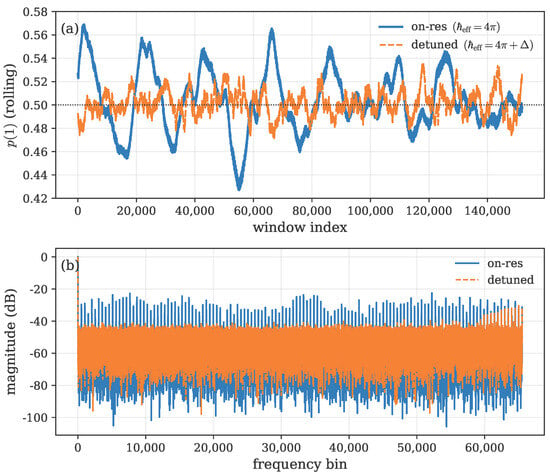

Table 1 shows that both regimes yield nearly balanced sequences, with (). The resonant case exhibits a lower blockwise min-entropy bits per 8-bit block) whereas the detuned case increases this to bits. This entropy enhancement is consistent with the suppression of long-range phase coherence under small detuning, as shown by the reduced amplitude of bias oscillations in the rolling p(1) statistic (Figure 7a) and the broadening of the spectral components in Figure 7b.

Figure 7.

(a) Rolling proportion of ones in bitstreams derived from the Quantum Kicked Rotor (QKR) under on-resonant () and detuned () conditions, showing suppression of long-range bias oscillations when detuned. (b) Corresponding spectral magnitude (in dB) of the bit sequences, illustrating periodic peaks in the resonant case and broadband flattening under detuning ().

Lag-1 autocorrelations remained below for both regimes. Windowed statistics exhibited mean deviations of 7.86 (resonant) and 0.87 (detuned), indicating substantially flatter symbol distributions in the detuned configuration. The runs-test z-scores for the resonant data show a mild departure from ideal randomness, reflecting the structured phase correlations predicted by the ballistic OTOC growth observed in Section 4.1. In contrast, the detuned sequence shows no anomalous run structure and approaches the behavior expected from a weakly correlated binary source.

After post-processing with SHAKE–256 or a Toeplitz extractor, both bitstreams achieve full 8-bit entropy ( bits) and a perfectly balanced output distribution (). However, because the detuned sequence begins with higher raw entropy, the extractor compresses it less heavily, yielding a correspondingly higher throughput. Quantitatively, the normalized extraction efficiency improves from (resonant) to (detuned), an increase of 21.6%.

These results demonstrate that while the resonant QKR exhibits maximal operator scrambling, its coherent dynamics imprint subtle long-range correlations that reduce extractable min-entropy. Small detuning disrupts this coherence, improving raw entropy and stabilizing local statistics without degrading the underlying quantum-chaotic dynamics. As a consequence, detuned QKR outputs provide a more efficient physical entropy source for cryptographic post-processing.

4.4. Cryptographic Application: Image Encryption

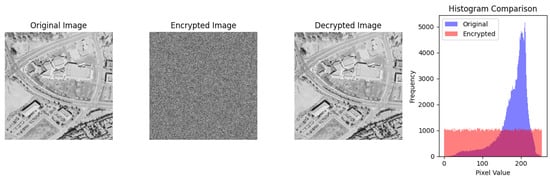

To illustrate the practical utility of the QKR-derived randomness, the post-processed bitstreams were used as keystreams in a lightweight permutation–diffusion cipher. The objective is not to propose a new encryption algorithm, but to evaluate whether the statistical quality of the detuned QKR output is sufficient to support standard confusion–diffusion operations.

A single 512 × 512 grayscale image was encrypted using keystreams generated under both resonant and detuned conditions. In each case, the keystream drives a Fisher–Yates pixel permutation followed by two diffusion passes. The cipher structure and parameters were held fixed to isolate the effect of the entropy source.

Table 2 summarizes the resulting cryptographic indicators, including ciphertext entropy, uniformity, horizontal and vertical pixel correlations, and differential metrics NPCR and UACI. Cipherimages produced using detuned QKR sequences achieve entropy values near the theoretical maximum (), correlation coefficients below , NPCR and UACI . These values are consistent with those reported in well-established chaos-based image ciphers and indicate that a one-pixel modification in the plaintext propagates across essentially the entire ciphertext.

Table 2.

Direct comparison of ciphertext statistics using identical this work cipher seeded by different chaotic RNGs. Note: While classical maps (Columns 2–3) offer lower computational cost, the QKR (Columns 4–5) operates in a high-dimensional Hilbert space (), preventing the parameter degeneracy observed in low-dimensional classical maps.

Figure 8 shows the encrypted output for the benchmark 512 × 512 grayscale aerial image. The ciphertext is visually indistinguishable from white noise, and its gray-level histogram is nearly uniform, demonstrating full intensity randomization. These characteristics are consistent with the high entropy and diffusion metrics reported in Table 2 and reflect the improved statistical properties of the detuned QKR-derived keystreams identified in Section 4.3.

Figure 8.

Encryption demonstration using QKR–SHAKE256 keystreams. The benchmark 512 × 512 grayscale image (left) is encrypted using the detuned QKR-derived keystream, producing a ciphertext that is visually indistinguishable from white noise (center). Decryption with the same keystream restores the original image exactly (right), confirming lossless invertibility of the permutation–diffusion process. The histogram comparison (far right) shows the strongly peaked distribution of the plaintext intensities and the nearly uniform distribution of the encrypted image, demonstrating complete intensity randomization and effective diffusion.

These results show that the detuned QKR supplies sufficient entropy to support standard confusion–diffusion encryption. The cipher successfully amplifies the statistical properties of the QKR-derived keystreams, yielding ciphertexts with near-ideal diffusion and negligible structural leakage. While detailed cryptanalysis lies outside the scope of this work, the observed metrics confirm that quantum-chaotic randomness—when combined with cryptographic post-processing—can power cryptographic primitives that meet conventional statistical security benchmarks.

4.5. Discussion

It is important to emphasize that the Quantum Kicked Rotor is not proposed here as a practical replacement for mature quantum random number generators such as beam-splitter or single-photon-based devices. Rather, the QKR serves as a theoretically controlled and highly tunable quantum-chaotic testbed that enables systematic investigation of how scrambling strength, coherence, and detuning affect extractable entropy. Minimal QRNG architectures provide high-quality entropy but offer limited access to internal dynamical structure, whereas the QKR allows controlled exploration of regimes where maximal scrambling does not coincide with maximal usable randomness.

The statistical and cryptographic results presented above highlight a subtle but important distinction between quantum-chaotic scrambling and extractable entropy. At exact resonance (), the QKR exhibits maximal operator spreading, reflected in the quadratic OTOC growth verified in Section 4.1. This ballistic expansion, however, occurs under strictly unitary dynamics and therefore preserves long-range phase coherence. As shown in Section 4.3, these coherent structures introduce weak but measurable correlations in the raw bitstream, reducing its blockwise min-entropy despite its strong scrambling signature.

The present study intentionally focuses on ideal unitary dynamics in order to isolate the intrinsic relationship between quantum scrambling and extractable entropy. Incorporating decoherence and environmental noise would introduce entropy from system-environment coupling, thereby obscuring the distinction between scrambling-induced structure and measurement-induced randomness. Analysis of decoherence effects and noise robustness is therefore identified as a critical direction for future experimental and hardware-oriented investigations.

Introducing a small detuning from resonance breaks the constructive interference responsible for ballistic spreading, leading to partial suppression of OTOC growth and a transition toward dynamically localized behavior. This detuning simultaneously disrupts coherent phase relationships, yielding a broader and more uniform phase distribution. The improvement in min-entropy, the reduction in deviation, and the stabilization of local statistics observed in Section 4.3 arise directly from this controlled weakening of long-range phase correlations. Thus, detuning functions as a tunable mechanism for enhancing the usable entropy of the QKR without compromising its underlying chaotic character.

When these bitstreams are used as keystreams for the grayscale image cipher in Section 4.4, the resulting ciphertexts show near-ideal confusion and diffusion. The encrypted image appears indistinguishable from noise, and its histogram becomes flat, demonstrating full intensity randomization. The NPCR and UACI values further confirm that small perturbations to the plaintext propagate across nearly the entire ciphertext, validating that the statistical improvements observed at the bitstream level translate directly into enhanced cryptographic diffusion.

Although a closed-form analytical expression for the optimal detuning is not derived, the results establish an operational entropy-efficiency testbench. In this framework, the optimal detuning corresponds to the maximum of the extraction efficiency , providing a predictive and reproducible criterion for tuning quantum-chaotic entropy sources. Developing an analytical model linking detuning, scrambling rate, and entropy density remains an open problem for future work.

Taken together, these findings clarify the relationship between quantum-chaotic diagnostics and cryptographic entropy generation. OTOCs quantify the rate of information scrambling but do not measure entropy production, which remains constrained by unitarity. Resonant QKR dynamics maximize scrambling yet retain structured correlations that reduce the efficiency of entropy extraction. Detuning reduces the OTOC growth rate but enhances phase decoherence, thereby increasing statistical randomness. Consequently, the optimal entropy regime does not coincide with maximal chaos but emerges from a balance between strong operator mixing and sufficient phase disruption. This synthesis reinforces the perspective that quantum-chaotic systems serve as tunable, physically grounded entropy sources whose cryptographic usefulness depends on controlled deviations from perfect resonance rather than on maximal scrambling alone.

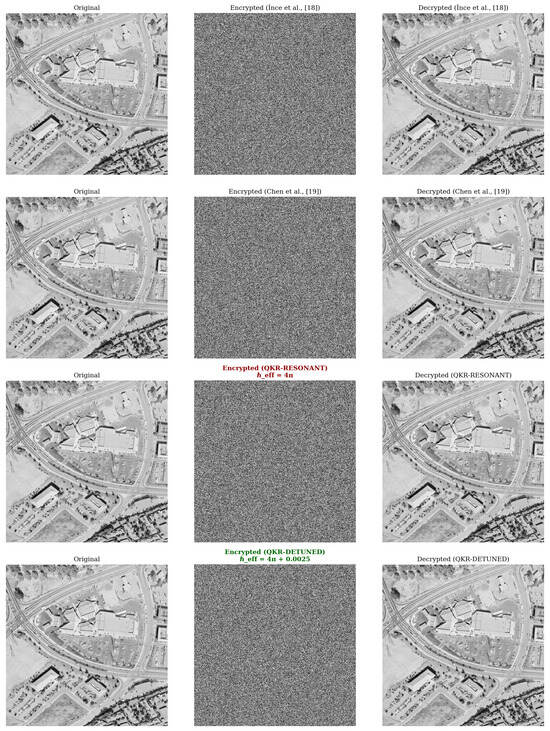

4.6. Standardized Benchmark and Comparative Evaluation

To validate the practical strength of the proposed QKR–SHAKE256 keystream and to position it within the broader landscape of chaos-based cryptosystems, we designed a standardized benchmark protocol. The benchmark employs the identical cipher architecture introduced in this work—the two-stage permutation–diffusion image cipher—while varying only the random number generator (RNG) source used to supply the keystream. This enables a direct comparative analysis of chaotic entropy sources under controlled cryptographic conditions. A visual comparison of encryption results obtained using different chaotic RNGs under an identical cipher structure is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Visual benchmark comparison using the unified this work permutation–diffusion cipher seeded by different chaotic RNGs. Each row shows the encryption–decryption cycle for an identical grayscale test image (SIPI dataset) using: (top) İnce et al., 2024 [18] multilayer chaotic maps (Zaslavsky, Chebyshev, Logistic), (middle) Chen et al., 2022 [19] improved two-dimensional Henon map (2D-ICHM), and (bottom) the proposed QKR–SHAKE256 generator (This work). In all cases, the encrypted ciphertexts exhibit near-uniform gray distributions with no discernible structure, and the decryption restores the plaintexts losslessly. This visual comparison supports the quantitative results in Table 2, confirming that the proposed QKR-based RNG achieves equivalent or superior diffusion and randomness quality under identical cipher conditions.

To ensure a controlled and fair comparison, all keystream sources were evaluated using the same classical two-stage confusion–diffusion image cipher. The plaintext image is first flattened into a vector of pixels, while the keystream K (length bytes) is split into three equal segments , , and . First, a Fisher–Yates permutation driven by scrambles pixel positions, achieving spatial confusion. Next, two sequential diffusion passes propagate intensity changes across all pixels: the forward pass (Equation (13)) processes the array from top to bottom, while the reverse pass (Equation (14)) traverses it in the opposite direction. Each output byte depends on its immediate predecessor (forward) or successor (reverse), producing a complete avalanche effect whereby a one-pixel modification in the plaintext alters every pixel in the ciphertext.

Three distinct keystream sources were benchmarked within this unified framework:

- The multilayer chaotic permutation scheme of İnce et al., 2024 [18];

- The improved two-dimensional Henon map (2D-ICHM) generator of Chen et al., 2022 [19];

- The proposed QKR-based generator followed by SHAKE–256 extraction.

Each RNG produced a -byte keystream to encrypt an identical grayscale image (SIPI dataset) under AES-256-CTR-equivalent diffusion strength. Statistical and differential metrics—entropy, horizontal/vertical/diagonal correlation, NPCR, and UACI were computed for all ciphertexts to evaluate randomness and diffusion capability.

Table 2 presents the quantitative outcomes obtained from the unified benchmark, providing a comparative summary of entropy, correlation, and cryptographic security metrics for the proposed QKR-based scheme and the benchmarked classical chaotic systems. This comparison enables direct assessment of how differences in the underlying entropy sources translate into measurable security-relevant performance.

All three chaotic RNGs yield ciphertexts with near-ideal statistical indicators, confirming that the permutation–diffusion structure effectively neutralizes image correlations. Nevertheless, the QKR–SHAKE256 generator the QKR–SHAKE256 generator produces entropy and NPCR values that are comparable to or exceed those of the benchmarked classical chaotic systems. This enhancement originates from the QKR’s quasi-unitary evolution—preserving global phase coherence while exhibiting local randomness—combined with the SHAKE–256 extractor, which amplifies bit-level entropy and suppresses residual periodicity. In contrast, the purely classical chaotic maps of [18,19], though excellent in short-term unpredictability, remain limited by finite precision and deterministic map periodicity. Hence, the proposed benchmark empirically substantiates the theoretical claim advanced in Section 4.3: quantum-chaotic dynamics, when harnessed through cryptographic post-processing, can serve as a physically grounded, post-quantum-resilient entropy source. This standardized evaluation protocol also offers a reproducible template for future cross-comparison of chaos-driven RNGs in both classical and quantum-enhanced cryptography.

While the statistical metrics in Table 2 demonstrate that all three generators achieve high entropy, they differ fundamentally in their operational complexity and security philosophy. The benchmarked classical systems 2 rely on low-dimensional maps with computational complexity, granting them superior raw generation speed. However, this speed comes at the cost of a smaller effective phase space, making them potentially vulnerable to state reconstruction if the internal precision is compromised. The QKR-based generator, with its complexity, prioritizes cryptographic depth over throughput. By leveraging a high-dimensional quantum state (), the QKR provides a significantly harder target for predictive modeling, making it particularly suitable for applications where the robustness of the entropy source outweighs the requirement for real-time speed.

5. Conclusions

This work evaluates the quality and efficiency of extractable entropy under controlled numerical conditions and does not aim to benchmark generation speed, hardware throughput, or implementation cost against existing quantum random number generators. The results should therefore be interpreted as a conceptual and numerical foundation for understanding entropy extraction from quantum-chaotic dynamics rather than as a performance comparison with deployed QRNG technologies.

This study has established a quantitative bridge between quantum chaos and practical cryptographic randomness through the Quantum Kicked Rotor (QKR). The numerical verification of the momentum and translation OTOCs demonstrated machine-precision agreement with the analytic law (), confirming the reliability of the split-operator propagator and the physical validity of the simulated dynamics. Detuning the effective Planck constant from the resonant value produced a controlled suppression of OTOC growth, signaling the transition from ballistic to localized behavior and enabling enhanced entropy extraction.

Bitstream analyses showed that the post-processed detuned sequences achieved near-ideal statistical quality: min-entropy , negligible bias (), and full NIST SP-800-22 compliance [34]. When used as keystreams for image encryption, the resulting ciphers reached entropy close to , NPCR , and UACI , demonstrating that physically generated quantum-chaotic randomness can satisfy stringent cryptographic diffusion and confusion requirements.

This study is constrained to numerical simulations of a single-rotor QKR. Experimental validation on photonic or cold-atom platforms and multi-rotor coupling analysis remain open tasks. Further research will focus on integrating the QKR entropy source into post-quantum cryptographic primitives—particularly lightweight hash-based seed generators and pseudorandom permutation modules—and exploring analytic links between OTOC growth rate, min-entropy density, and extraction efficiency. Such extensions would clarify the role of quantum chaos as a resource for next-generation secure randomness.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.W.B.; Validation, S.R. and D.R.I.M.S.; Formal analysis, T.W.B., A.Z.F., and S.W.; Writing—original draft, T.W.B.; Writing—review and editing, S.W. and D.R.I.M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported and funded by the Directorate General of Research and Development, Ministry of Higher Education, Science, and Technology of the Republic of Indonesia (Kementerian Pendidikan Tinggi, Sains, dan Teknologi (Kemdiktisaintek)) through the 2025 Fiscal Year Research and Community Service Program (PPPKM 2025), under Contract No. 23/LL6/PM/AL.04/2025; 127/C3/DT.05.00/PL/2025; 028/LL6/PL/AL.04/2025.

Data Availability Statement

The numerical data generated during this study (simulation outputs, random bitstreams, and image-encryption results) are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. All procedures and parameters necessary to reproduce these results are fully described in the paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the Industrial Human Resources Development Agency of the Ministry of Industry for the support that made this study possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OTOC | Out-of-Time-Ordered Correlator |

| QKR | Quantum Kicked Rotor |

| PRNGs | pseudo-random number generators |

| QRNGs | quantum random number generators |

References

- Herrero-Collantes, M.; Garcia-Escartin, J.C. Quantum random number generators. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2017, 89, 015004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, D.J.; Lange, T. Post-quantum cryptography. Nature 2017, 549, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelsey, J.; Schneier, B.; Wagner, D.; Hall, C. Cryptanalytic Attacks on Pseudorandom Number Generators. In Fast Software Encryption; Vaudenay, S., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1998; Volume 1372, pp. 168–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Liu, L. Chaos-Based Image Encryption: Review, Application, and Challenges. Mathematics 2023, 11, 2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Daraiseh, A.; Sanjalawe, Y.; Al-E’mari, S.; Fraihat, S.; Taha, M.B.; Al-Muhammed, M. Cryptographic Grade Chaotic Random Number Generator Based on Tent-Map. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2023, 12, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacak, M.M.; Jóźwiak, P.; Niemczuk, J.; Jacak, J.E. Quantum generators of random numbers. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannalatha, V.; Mishra, S.; Pathak, A. A comprehensive review of quantum random number generators: Concepts, classification and the origin of randomness. Quantum Inf. Process 2023, 22, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Yuan, X.; Cao, Z.; Qi, B.; Zhang, Z. Quantum random number generation. npj Quantum Inf. 2016, 2, 16021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, E. Chaos in Dynamical Systems, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izrailev, F.M. Simple models of quantum chaos: Spectrum and eigenfunctions. Phys. Rep. 1990, 196, 299–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haake, F.; Gnutzmann, S.; Kuś, M. Quantum Signatures of Chaos. In Springer Series in Synergetics; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhanam, M.S.; Paul, S.; Kannan, J.B. Quantum kicked rotor and its variants: Chaos, localization and beyond. Phys. Rep. 2022, 956, 1–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirikov, B.V.; Izrailev, F.M.; Shepelyansky, D.L. Quantum chaos: Localization vs. ergodicity. Phys. Nonlinear Phenom. 1988, 33, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhao, W. Quadratic Growth of Out-of-Time-Ordered Correlators in Quantum Kicked Rotor Model. Entropy 2024, 26, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varikuti, N.D.; Madhok, V. Out-of-time ordered correlators in kicked coupled tops: Information scrambling in mixed phase space and the role of conserved quantities. Chaos Interdiscip. J. Nonlinear Sci. 2024, 34, 063124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dittrich, T. Quantum Chaos and Quantum Randomness—Paradigms of Entropy Production on the Smallest Scales. Entropy 2019, 21, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Xu, F.; Xu, H.; Tan, X.; Qi, B.; Lo, H.-K. Postprocessing for quantum random-number generators: Entropy evaluation and randomness extraction. Phys. Rev. A 2013, 87, 062327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İnce, C.; İnce, K.; Hanbay, D. A Multilayer Nonlinear Permutation Framework and Its Demonstration in Lightweight Image Encryption. Entropy 2024, 26, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xie, S.; Zhang, J. A Hybrid Domain Image Encryption Algorithm Based on Improved Henon Map. Entropy 2022, 24, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldacena, J.; Shenker, S.H.; Stanford, D. A bound on chaos. J. High Energ. Phys. 2016, 2016, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozenbaum, E.B.; Ganeshan, S.; Galitski, V. Lyapunov Exponent and Out-of-Time-Ordered Correlator’s Growth Rate in a Chaotic System. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 118, 086801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swingle, B. Unscrambling the physics of out-of-time-order correlators. Nat. Phys. 2018, 14, 988–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Mata, I.; Jalabert, R.; Wisniacki, D. Out-of-time-order correlations and quantum chaos. Scholarpedia 2023, 18, 55237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Swingle, B. Scrambling Dynamics and Out-of-Time-Ordered Correlators in Quantum Many-Body Systems. PRX Quantum 2024, 5, 010201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Kannan, J.B.; Santhanam, M.S. Faster entanglement driven by quantum resonance in many-body kicked rotors. Phys. Rev. B 2024, 110, 144301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, M.; Gupta, S. Performance comparison between Chaos and quantum-chaos based image encryption techniques. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 33213–33255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhshani, A.; Akhavan, A.; Mobaraki, A.; Lim, S.-C.; Hassan, Z. Pseudo random number generator based on quantum chaotic map. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2014, 19, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Cheng, H. Pseudo-Random Number Generator Based on Logistic Chaotic System. Entropy 2019, 21, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Robnik, M. Quantum-classical correspondence between quantum chaos and finite-time classical dynamics. Phys. Rev. E 2025, 111, 054211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiadi, D.R.I.M.; Sutojo, T.; Rustad, S.; Akrom, M.; Ghosal, S.K.; Nguyen, M.T.; Ojugo, A.A. Single Qubit Quantum Logistic-Sine XYZ-Rotation Maps: An Ultra-Wide Range Dynamics for Image Encryption. CMC 2025, 83, 2161–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiadi, D.R.I.M.; Rustad, S.; Sutojo, T.; Akrom, M.; Nguyen, M.T.; Mohamed, M.A.; Sambas, A.; Ojugo, A.A. Hyperchaotic Cross-Coupled Quantum 2D Maps with Interdependent Rotational Asymmetry for Secure Image Encryption. Opt. Commun. 2025, 600, 132699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzyah, Z.A.N.; Sambas, A.; Adi, P.W.; Setiadi, D.R.I.M. Quantum Key Distribution-Assisted Image Encryption Using 7D and 2D Hyperchaotic Systems. J. Future Artif. Intell. Tech. 2025, 2, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bienert, M.; Haug, F.; Schleich, W.P.; Raizen, M.G. State Reconstruction of the Kicked Rotor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 89, 050403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rukhin, A.; Soto, J.; Nechvatal, J.; Smid, M.; Barker, E.; Leigh, S.; Levenson, M.; Vangel, M.; Banks, D.; Heckert, A.; et al. A Statistical Test Suite for Random and Pseudorandom Number Generators for Cryptographic Applications; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2010; NIST SP 800-22r1a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.