A Time-Frequency Fusion Fault Diagnosis Framework for Nuclear Power Plants Oriented to Class-Incremental Learning Under Data Imbalance

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To effectively address sample imbalance and catastrophic forgetting in nuclear fault diagnosis, we propose an improved class-incremental fault diagnosis framework based on SCLIFD. This framework integrates an LSTM–Transformer mechanism to capture long-term dependencies in nuclear fault data, thereby mitigating catastrophic forgetting.

- To resolve feature selection challenges within the time-series nuclear dataset NPPAD, a SHAP-XGBoost-based feature interpretation and evaluation system is constructed, enhancing both accuracy and interpretability in the feature selection process.

- To capture both local and global dependencies in time-series data, we enhance the original feature extractor by integrating an improved ATFNet framework that combines time-domain and frequency-domain modules, thereby further strengthening the model’s feature recognition capability.

2. Experimental Motivation

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Preparation and Preprocessing

3.1.1. NPPAD Dataset

3.1.2. Data Selection and Processing

3.2. Feature Selection Method

3.2.1. Initial Feature Screening

3.2.2. Interpretable Model and SHAP-XGBoost

3.2.3. Feature Evaluation System Based on SHAP-XGBoost

| Algorithm 1 SDG-Shield Two-Stage Feature Selection Algorithm |

| Input: Original feature set (), label y, threshold Output: Final selected feature set

|

- Baseline-ALL: directly uses all 23 original variables;

- Baseline-SDG: trains XGBoost only with the SDG-selected subset ;

- Proposed: further applies SHAP-based screening on and retains the Top-k features with the largest mean absolute SHAP values.

3.3. Model Improvements

3.3.1. Class-Incremental Fault Diagnosis Framework Based on Supervised Contrastive Knowledge Distillation

3.3.2. Improved LSTM-Transformer Fusion Layer

3.3.3. Improved Framework with ATFNet-Based Time–Frequency Fusion

4. Experimental Design

4.1. Experimental Environment Configuration

4.2. Data Preparation

4.3. Model Training

- Multiple residual blocks in the encoder extract the input features, producing an output of (batch size, sequence length, 512).

- The extracted features are fed into an LSTM layer (hidden size 512, unidirectional or bidirectional), yielding (batch size, sequence length, ).

- After reshaping, the features are passed through a Transformer layer, maintaining the same shape. The output is then reshaped back, and the last time step is taken, resulting in (batch size, ).

- If the frequency-domain processing module (F_Block) is enabled, the above features are reshaped into (batch size, feature dimension, 1) and passed into the F_Block. The predicted sequence is generated, and the last time step is taken to obtain frequency-domain features of shape (batch size, output feature dimension).

- The time-domain and frequency-domain features are concatenated to form the fused representation of shape (batch size, .

- The fused features are fed into a fully connected layer to perform classification, producing predictions of shape (batch size, number of classes).

5. Experimental Results and Analysis

5.1. Result Analysis

5.2. Ablation Study and Analysis

5.2.1. Effectiveness of the Feature Selection Strategy

5.2.2. Contribution Analysis of Model Structure Components

5.2.3. Sensitivity Analysis of Memory Buffer and Sample Configuration

5.2.4. Overall Analysis

- Feature level: an appropriate feature selection strategy yields the most significant performance gain (about +20.7%), and serves as the foundation for raising the performance ceiling.

- Model level: the improved hybrid architecture contributes an additional performance gain of about +8.4%, substantially enhancing the representation capacity for complex temporal patterns.

- Strategy level: optimizing the memory buffer and new-class sample configuration further reduces forgetting and improves recognition performance for long-tail classes.

5.3. Limitations and Directions for Improvement

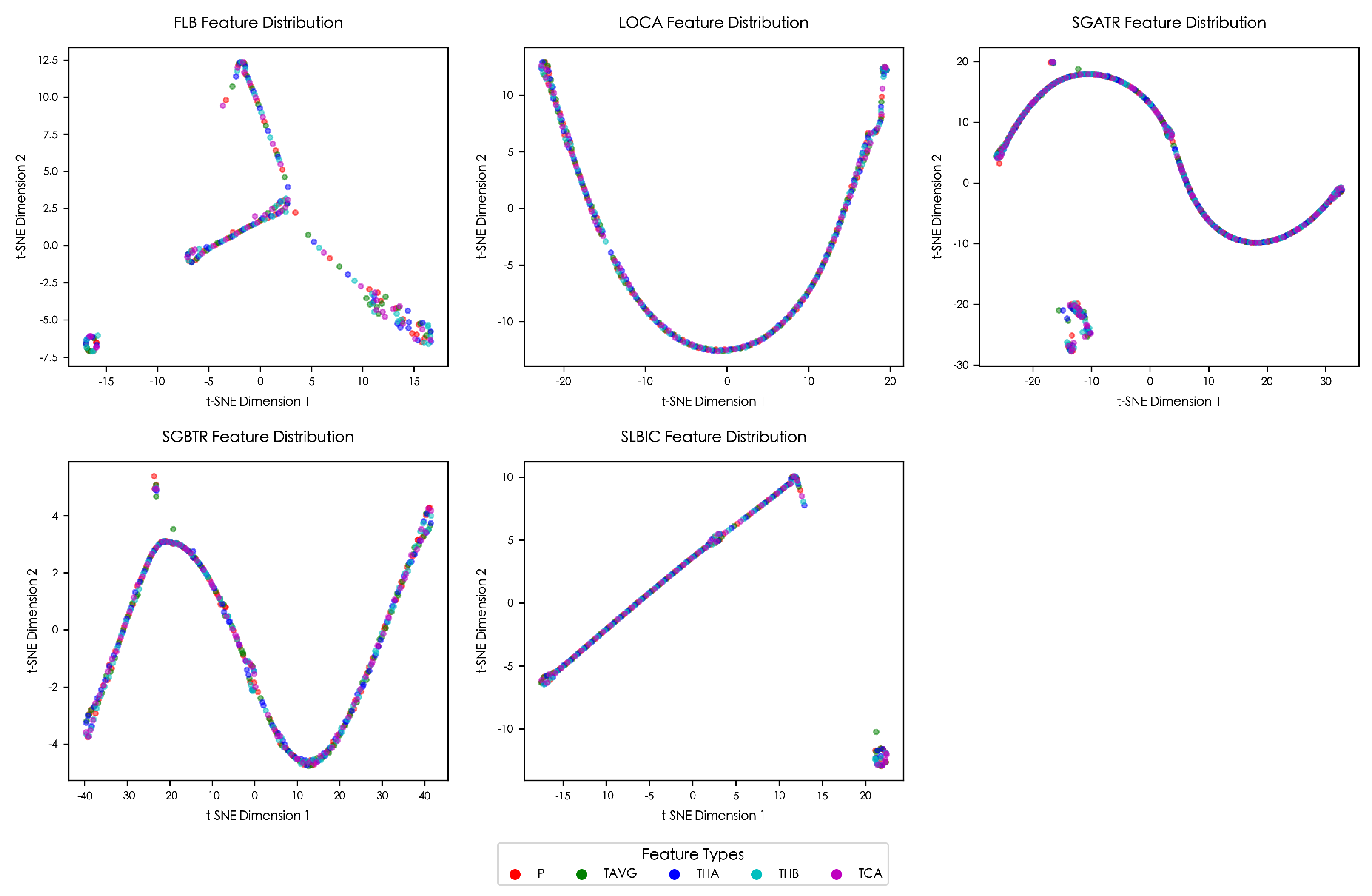

5.3.1. Feature Overlap Between Old and New Classes Causes Cross-Class Misclassification

5.3.2. Insufficient Memory Buffer Size K Leads to Forgetting of Old-Class Knowledge

5.3.3. Insufficient Shot Number Results in Poor Fitting of New Classes

5.3.4. Computational Cost and Deployment Considerations

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hu, G.; Zhou, T.; Liu, Q. Data-driven machine learning for fault detection and diagnosis in nuclear power plants: A review. Front. Energy Res. 2021, 9, 663296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, B.; Liang, J.; Tong, J. Fault diagnosis techniques for nuclear power plants: A review from the artificial intelligence perspective. Energies 2023, 16, 1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y. Research on Fault Diagnosis Technology of Nuclear Power Plants Based on Data Mining. Ph.D. Thesis, Harbin Engineering University, Harbin, China, 2011. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Wei, H.; Tian, R.; Tan, S. A review of data-driven fault diagnosis method for nuclear power plant. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2025, 186, 105785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Xue, X.; Xue, J.; Qu, Y. Fault Detection in Nuclear Power Plants using Deep Leaning based Image Classification with Imaged Time-series Data. Int. J. Comput. Commun. Control 2022, 17, 4714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, K.; Singer, R.; Wegerich, S.; Herzog, J.; VanAlstine, R.; Bockhorst, F. Application of a Model-Based Fault Detection System to Nuclear Plant Signals; Technical Report; Argonne National Lab. (ANL): Argonne, IL, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Geng, S. Dynamic uncertain causality graph applied to dynamic fault diagnoses of large and complex systems. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 2015, 64, 910–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhang, J.; Wan, J.; Wu, S. A fault diagnosis method for small pressurized water reactors based on long short-term memory networks. Energy 2022, 239, 122298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wang, Y.; Sun, X.; Liu, S.; Du, B. Imbalanced data fault diagnosis method for nuclear power plants based on convolutional variational autoencoding Wasserstein generative adversarial network and random forest. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2024, 56, 5055–5067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Peng, L.; Juan, Z.; Liang, Y.; Shen, J.; Wang, S.; Tan, S.; Yu, H.; Sun, M. An intelligent fault diagnosis method for imbalanced nuclear power plant data based on generative adversarial networks. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2023, 18, 3237–3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yongkuo, L.; Zhen, L.; Xiaotian, W. Research on fault diagnosis with SDG method for nuclear power plant. At. Energy Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 1646–1653. [Google Scholar]

- Rebuffi, S.A.; Kolesnikov, A.; Sperl, G.; Lampert, C.H. icarl: Incremental classifier and representation learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2001–2010. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, B.; Xiao, X.; Liang, J.; Po, L.c.C.; Zhang, L.; Tong, J. An open time-series simulated dataset covering various accidents for nuclear power plants. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricker, N.L. Decentralized control of the Tennessee Eastman challenge process. J. Process Control 1996, 6, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Cárcel, C.; Cao, Y.; Mba, D.; Lao, L.; Samuel, R. Statistical process monitoring of a multiphase flow facility. Control Eng. Pract. 2015, 42, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-K.; Ayodeji, A.; Wen, Z.-B.; Wu, M.-P.; Peng, M.-J.; Yu, W.-F. A cascade intelligent fault diagnostic technique for nuclear power plants. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 254–266. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1603.02754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanaee-T, H.; Gama, J. Event labeling combining ensemble detectors and background knowledge. Prog. Artif. Intell. 2014, 2, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Su, J.; Li, M.; Peng, P.; Wang, H. Class Incremental Fault Diagnosis Under Limited Fault Data via Supervised Contrastive Knowledge Distillation. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2025, 21, 4344–4354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosla, P.; Teterwak, P.; Wang, C.; Sarna, A.; Tian, Y.; Isola, P.; Maschinot, A.; Liu, C.; Krishnan, D. Supervised contrastive learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 18661–18673. [Google Scholar]

- Greff, K.; Srivastava, R.K.; Koutník, J.; Steunebrink, B.R.; Schmidhuber, J. LSTM: A search space odyssey. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2016, 28, 2222–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, I.F.; Zhou, Y.; Chang, L.C.; Chang, F.J. Exploring a Long Short-Term Memory based Encoder-Decoder framework for multi-step-ahead flood forecasting. J. Hydrol. 2020, 583, 124631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoo, K.; Ishida, K.; Ercan, A.; Tu, T.; Nagasato, T.; Kiyama, M.; Amagasaki, M. Capabilities of deep learning models on learning physical relationships: Case of rainfall-runoff modeling with LSTM. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 802, 149876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, F.; Majumdar, S.; Darabi, H.; Harford, S. Multivariate LSTM-FCNs for time series classification. Neural Netw. 2019, 116, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gers, F.A.; Eck, D.; Schmidhuber, J. Applying LSTM to time series predictable through time-window approaches. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks, Vienna, Austria, 21–25 August 2001; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; pp. 669–676. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Chen, S. Non-stationary multivariate time series prediction with selective recurrent neural networks. In Proceedings of the Pacific Rim International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Cuvu, Fiji, 26–30 August 2019; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 636–649. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2017, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Volume 30, pp. 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.; Zhang, S.; Peng, J.; Zhang, S.; Li, J.; Xiong, H.; Zhang, W. Informer: Beyond efficient transformer for long sequence time-series forecasting. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Online, 2–9 February 2021; Volume 35, pp. 11106–11115. [Google Scholar]

- Kow, P.Y.; Liou, J.Y.; Yang, M.T.; Lee, M.H.; Chang, L.C.; Chang, F.J. Advancing climate-resilient flood mitigation: Utilizing transformer-LSTM for water level forecasting at pumping stations. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 927, 172246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Chen, J.; Gong, S.; Jiang, F.; Zhang, T.; Chen, J.; Gao, X. Atfnet: Adaptive time-frequency ensembled network for long-term time series forecasting. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.05192. [Google Scholar]

| ID | Labels | Operation Conditions | Training Set | Testing Set |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | NORMAL | Normal Operation | 200 | 200 |

| 1 | LOCA | Loss of Coolant Accident (Hot Leg) | 5 | 200 |

| 2 | SGATR | Steam Generator A Tube Rupture | 5 | 200 |

| 3 | SGBTR | Steam Generator B Tube Rupture | 5 | 200 |

| 4 | FLB | Feedwater Line Break | 5 | 200 |

| 5 | SLBIC | Steam Line Break Inside Containment | 5 | 200 |

| K | Shot | Average Metrics (All Sessions) | Final Session | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy (%) | Macro-F1 (%) | Bal-Acc (%) | Macro-F1 (%) | ||

| 10 | 1 | 82.10 | 80.45 | 80.98 | 76.20 |

| 40 | 1 | 89.36 | 88.75 | 89.10 | 85.40 |

| 100 | 1 | 91.05 | 90.80 | 90.52 | 88.30 |

| 40 | 2 | 92.25 | 91.83 | 91.50 | 89.75 |

| 40 | 5 | 94.10 | 93.65 | 93.25 | 92.30 |

| Dataset | Total Classes | Incremental Sessions | Shot | Training Set (Normal/Fault) | Testing Set (Normal/Fault) | Memory Buffer K |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TEP | 10 | 5 | 2 | 525/248 | 1600 | 40/100 |

| NPPAD | 5 | 5 | 1 | 225 | 400 | 5/10 |

| ID | Node Label | ID | Node Label | ID | Node Label |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | WLR | 9 | MCRT | 17 | QMGA |

| 2 | CNH2 | 10 | MGAS | 18 | QMGB |

| 3 | RHRD | 11 | TDBR | 19 | NSGA |

| 4 | RBLK | 12 | TSLP | 20 | NSGB |

| 5 | SGLK | 13 | TCRT | 21 | FRCL |

| 6 | MBK | 14 | QMWT | 22 | PRB |

| 7 | EBK | 15 | LSGA | 23 | TRB |

| 8 | MDBR | 16 | LSGB |

| ID | Node Label | ID | Node Label | ID | Node Label |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | HUP | 9 | WTRA | 17 | LSGB |

| 2 | TAVG | 10 | SCMA | 18 | SCMB |

| 3 | WFWA | 11 | WTRB | 19 | WHPI |

| 4 | VOL | 12 | WECS | 20 | LSGA |

| 5 | WRCA | 13 | WRCB | 21 | QMWT |

| 6 | TSAT | 14 | STRB | 22 | PSGB |

| 7 | THB | 15 | PSGA | 23 | WFWB |

| 8 | LVPZ | 16 | WSTA |

| Module | Hyperparameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| LSTM-Transformer | LSTM layers/hidden size | 1/512 |

| Transformer layers/heads | 2/4 | |

| /dropout | 512/0.1 | |

| ATFNet | FFT window length L | 50 |

| Max harmonic order M | 5 | |

| EMA decay/ | 0.9/ | |

| SCKD | Contrastive weight | 0.5 |

| Temperature | 0.1 | |

| Training | Optimizer/learning rate | Adam/0.001 |

| Batch size/iterations | 32/100 | |

| Random seeds | {0, 1, 2} |

| Dataset | Feature Selection Method | Model Method | Accuracy in Incremental Sessions | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSTM | Transformer | ATFNet | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | Average | ||

| TEP | Initial Feature Selection | 98.20% | 91.50% | 85.30% | 83.10% | 79.40% | 87.50% | |||

| ✓ | 98.50% | 93.40% | 87.20% | 85.10% | 81.00% | 89.04% | ||||

| ✓ | ✓ | 98.60% | 94.00% | 88.10% | 86.40% | 82.70% | 89.96% | |||

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 98.70% | 95.20% | 89.50% | 87.10% | 85.30% | 91.16% | ||

| SHAP-XGBoost Framework | 99.20% | 95.60% | 90.10% | 88.00% | 87.20% | 92.02% | ||||

| ✓ | 99.30% | 95.80% | 90.40% | 88.30% | 87.50% | 92.26% | ||||

| ✓ | ✓ | 99.40% | 96.10% | 90.80% | 88.60% | 88.10% | 92.60% | |||

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 99.40% | 96.40% | 91.30% | 89.20% | 89.50% | 93.16% | ||

| Dataset | Feature Selection Method | Model Method | Accuracy in Incremental Sessions | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSTM | Transformer | ATFNet | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | Average | ||

| NPPAD | Initial Feature Selection | 100.00% | 96.50% | 82.83% | 88.12% | 69.00% | 87.29% | |||

| ✓ | 100.00% | 95.75% | 89.17% | 85.88% | 71.70% | 88.50% | ||||

| ✓ | ✓ | 100.00% | 95.25% | 88.00% | 91.88% | 73.80% | 89.78% | |||

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 100.00% | 93.25% | 87.50% | 90.25% | 82.20% | 90.64% | ||

| SHAP-XGBoost Framework | 100.00% | 92.00% | 85.33% | 86.75% | 90.10% | 90.84% | ||||

| ✓ | 100.00% | 92.25% | 84.50% | 87.625% | 91.20% | 91.11% | ||||

| ✓ | ✓ | 100.00% | 92.25% | 86.17% | 87.50% | 88.60% | 90.90% | |||

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 100% | 91.75% | 86.33% | 89.00% | 89.70% | 91.36% | ||

| Method | Avg. Acc (%) | Last Acc (%) | Avg. Macro-F1 (%) | Forgetting F (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fine-tuning | 78.5 | 65.2 | 76.8 | 22.3 |

| LwF | 82.4 | 72.1 | 81.5 | 17.8 |

| iCaRL | 84.1 | 76.3 | 83.6 | 15.2 |

| SCLIFD | 88.9 | 84.0 | 88.1 | 9.7 |

| Proposed | 91.4 | 89.7 | 90.9 | 6.3 |

| Noise Std (%) | Method | Avg. Acc (%) | Avg. Macro-F1 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | SCLIFD | 88.9 | 88.1 |

| 0 | Proposed | 91.4 | 90.9 |

| 5 | SCLIFD | 87.1 | 86.5 |

| 5 | Proposed | 90.2 | 89.3 |

| 10 | SCLIFD | 84.0 | 83.1 |

| 10 | Proposed | 88.3 | 87.4 |

| 20 | SCLIFD | 79.5 | 78.2 |

| 20 | Proposed | 84.7 | 83.5 |

| Feature Selection Strategy | Accuracy (%) | Macro-F1 (%) | Bal-Acc (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| All-23 (Baseline) | 69.00 | 68.33 | 68.25 |

| SDG-Shield | 82.00 | 81.56 | 81.78 |

| SDG-Shield + SHAP | 89.70 | 89.12 | 89.45 |

| Model | Params (M) | Model Size (MB) | Latency (ms/Sample) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCLIFD (baseline) | 1.3 | 5.2 | 7.4 |

| Ours w/o ATFNet | 3.1 | 12.4 | 14.8 |

| Ours w/o Transformer | 3.4 | 13.6 | 16.2 |

| Ours (full model) | 4.9 | 19.6 | 24.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, H. A Time-Frequency Fusion Fault Diagnosis Framework for Nuclear Power Plants Oriented to Class-Incremental Learning Under Data Imbalance. Computers 2026, 15, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers15010022

Liu Z, Zhou Q, Liu H. A Time-Frequency Fusion Fault Diagnosis Framework for Nuclear Power Plants Oriented to Class-Incremental Learning Under Data Imbalance. Computers. 2026; 15(1):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers15010022

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Zhaohui, Qihao Zhou, and Hua Liu. 2026. "A Time-Frequency Fusion Fault Diagnosis Framework for Nuclear Power Plants Oriented to Class-Incremental Learning Under Data Imbalance" Computers 15, no. 1: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers15010022

APA StyleLiu, Z., Zhou, Q., & Liu, H. (2026). A Time-Frequency Fusion Fault Diagnosis Framework for Nuclear Power Plants Oriented to Class-Incremental Learning Under Data Imbalance. Computers, 15(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers15010022