Abstract

This study investigates the perceptions of Greek sixth-grade students regarding Artificial Intelligence (AI). Understanding students’ pre-instructional conceptions is essential for developing targeted interventions that build on existing knowledge rather than assuming conceptual deficits. A qualitative design was employed with 229 students from seven elementary schools in Athens, Greece. Data were collected through open-ended questions and word association tasks, then analyzed using Walan’s AI perceptions framework as an integrated set of analytical lenses (cognitive, affective, behavioral/use, and ethical considerations). Findings revealed that students hold multifaceted conceptions of AI. Cognitively, they described AI as robots, computational systems, software tools, and autonomous learning programs. Affectively, they expressed ambivalence, balancing appreciation of AI’s usefulness with concerns over potential risks. Behaviorally, they identified interactive question–answer functions, creative applications, and everyday assistance roles. Ethically, students raised issues of responsible use, societal implications, and human–AI relationships. This study contributes to international research, highlighting that primary students’ understandings of AI are more nuanced than is sometimes assumed, and offer empirical insights for designing culturally responsive, ethically informed AI literacy curricula.

1. Introduction

As Artificial Intelligence (AI) systems become increasingly embedded in everyday technologies, children are exposed to them from a young age—often through educational platforms, voice assistants, or algorithm-driven apps—before any formal instruction occurs [1]. Such early, pre-instructional experiences shape intuitive understandings [2], influencing how students later engage with AI-related learning. Understanding students’ conceptions of AI is thus critical for designing meaningful AI literacy education.

Research has shown that, even at the primary level, children form complex representations of AI, often combining factual knowledge with anthropomorphic, fictionalized, or emotionally charged associations [3,4]. Building on these findings, recent studies have explored this phenomenon across diverse contexts and age groups, revealing hybrid views of AI that combine technical understanding with anthropomorphic elements and emotional evaluations [4,5,6]. Students often associate AI with both support and threat [2,7], yet their frequent use of AI tools does not necessarily translate into a coherent conceptual understanding of how these systems function.

However, despite these insights, existing research rarely examines children’s perceptions across cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and ethical dimensions in an integrated way. To address this gap, Walan [1] proposed an integrated framework for analyzing primary students’ AI perceptions, incorporating these four dimensions. Grounded in Mitcham’s [8] philosophy of technology and expanded by Ankiewicz [9], the framework offers a structured yet flexible way to interpret children’s multifaceted understandings of AI. This study responds to that gap by applying Walan’s framework to investigate Greek sixth-grade students’ pre-instructional conceptions of AI.

2. Conceptual Framework

This study is situated within the growing field of human-centered Artificial Intelligence (AI) literacy, which conceptualizes AI not merely as a technical artifact to be mastered, but as a socio-technical phenomenon embedded in learners’ cognitive representations, emotional attitudes, everyday practices, and emerging ethical stances from early school age.

Contemporary AI literacy research emphasizes the need to move beyond narrow computational or coding-oriented approaches and toward holistic pedagogical frameworks integrating epistemic, affective, behavioral, and moral dimensions of human engagement with intelligent technologies [10]. Nevertheless, much of the existing literature remains fragmented, often focusing either on discrete technical knowledge or on patterns of tool use, and therefore rarely applies integrated conceptual lenses in a systematic manner to capture the multidimensional nature of children’s meaning-making around AI. This fragmentation limits cross-study comparability and restricts the development of culturally responsive educational interventions.

In response to this need, the present study adopts Walan’s [1] integrated framework for analyzing primary students’ perceptions of AI. The framework organizes student conceptions across four dimensions—cognitive, affective, behavioral, and ethical—designed to encapsulate how children conceptualize, emotionally evaluate, practically engage with, and morally reflect upon emerging AI technologies. Theoretically grounded in Mitcham’s [8] philosophy of technology and its educational elaboration by Ankiewicz [9], the model approaches technological literacy as a dynamic human–technology relationship. This multidimensional approach aligns with contemporary international research that emphasizes the interplay of these dimensions in understanding AI literacy, including recent studies in diverse contexts such as West Africa [11].

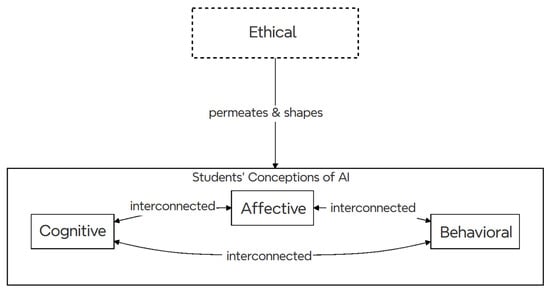

In this study, the four dimensions serve as interconnected and flexible analytical lenses (following Blumer’s [12] notion of sensitizing concepts), not as rigid or hierarchical categories. This is particularly evident in the role of the ethical dimension, which functions as a permeating evaluative layer that shapes and emerges within cognitive understandings, affective responses, and behavioral narratives. Figure 1 provides a visual representation of this integrated logic, where the ethical dimension is depicted as encompassing the other three, reflecting its cross-cutting nature. The bidirectional arrows among the cognitive, affective, and behavioral dimensions illustrate their reciprocal influence: cognitive understanding shapes emotional responses and practical engagement, while experiences and feelings recursively reshape conceptual models.

Figure 1.

Visual representation of Walan’s integrated framework for analyzing primary students’ AI perceptions, with the ethical dimension as a permeating layer encompassing the cognitive, affective, and behavioral dimensions.

The operational definitions of the four dimensions as applied in this study are summarized below:

- Cognitive dimension: Students’ conceptual explanations of AI, including representations of AI as machines, robots, computational systems, software platforms, or autonomous learning entities.

- Affective dimension: Emotional evaluations of AI, encompassing expressions of enthusiasm, fear, trust, skepticism, ambivalence, or anxiety regarding its societal role or potential impact.

- Behavioral dimension: Descriptions of actual or imagined interactions with AI systems, including educational use, creative applications, communication, and everyday assistance practices.

- Ethical dimension: Reflections related to responsibility, human agency, social consequences, fairness, misuse, employment displacement, and future human–AI relations.

This study does not treat the application of Walan’s framework as an attempt to replicate prior work; instead, it uses the framework to theoretically situate and guide the analysis in relation to prior research on students’ perceptions of AI while maintaining a non-evaluative stance toward the framework itself.

Guided by this framework, the present study addresses the following research questions:

- RQ1: How do Greek upper primary school students perceive AI in terms of its cognitive dimension?

- RQ2: How do Greek upper primary school students perceive AI in terms of its affective dimension?

- RQ3: How do Greek upper primary school students perceive AI in terms of its behavioral dimension?

- RQ4: How do Greek upper primary school students perceive AI in terms of its ethical dimension?

These questions explore interrelated facets of students’ AI perceptions, consistent with the integrated logic of Figure 1.

3. Methodology

3.1. Triangulation and Mixed-Methods Research Design

This study adopted a qualitative inductive design subsequently theoretically informed by Walan’s [1] four-dimensional framework. The analysis began inductively through open coding and iterative comparison, allowing patterns to emerge directly from the data. The resulting themes were then interpreted abductively, drawing on the framework as a set of sensitizing lens [12] to connect emerging patterns with existing theory [13]. A detailed account of the analytical phases and procedures is presented in Section 3.5.

3.2. Participants

The study involved 229 sixth-grade students (aged 11–12 years) from seven public elementary schools in the greater Athens metropolitan area. The sample, recruited through convenience sampling, consisted of 124 male (54.1%) and 105 female (45.9%) students, all attending mainstream general education classrooms. Prior to data collection, the study received formal institutional approval from the Greek Ministry of Education (Protocol No. 4830, March 2025) and fully adhered to ethical guidelines for research involving minors. School principals were formally informed in writing about the study’s aims and procedures and provided institutional consent. Parents received a written announcement explaining the purpose, voluntary nature, and confidentiality of the research, in line with ethical guidelines for school-based assessment. Verbal consent was obtained from parents, as the activity involved minimal risk and consisted solely of completing an anonymous questionnaire [14].

3.3. Data Collection Procedures

Data collection took place during April 2025, within regular school hours, across seven public elementary schools in Athens. Classroom teachers administered the paper-and-pencil questionnaire using a standardized protocol developed by the research team to ensure consistent procedures across sites. The procedure involved two phases within a single instructional period. In the first phase, students responded to the open-ended question: “What is Artificial Intelligence, in your opinion?”. In the second phase, students completed a word-association task: “What words come to mind when you hear ‘Artificial Intelligence’? (Write at least 3)”.

In line with recent recommendations for child-rights–based and ethically grounded participation in educational research [15], teachers received detailed facilitator guidelines emphasizing procedural neutrality [16]. They were asked to make clear that there were no “right” or “wrong” answers, to encourage students to express their own ideas freely, and to limit any interventions to procedural clarifications only. Teachers were explicitly instructed to avoid providing examples, interpretations, or suggestions that might influence the students’ responses.

Participation was entirely voluntary. Students were informed that they could skip any question or withdraw from the activity at any time, and none chose to discontinue their participation. Upon completion, the anonymous questionnaires were collected by the teachers, sealed in envelopes, and securely delivered to the research team for analysis.

3.4. Data Preparation

All data were digitized and organized into two categories: written definitional responses and word associations. All handwritten responses were transcribed verbatim by two independent researchers. To ensure lexical consistency and analytical validity, a systematic data-cleaning process was carried out prior to analysis [17]. This process involved spelling corrections, grammatical normalization, and the consolidation of semantically equivalent terms. For example, responses with similar or identical meanings (e.g., computer, computers, PC, and laptop) were grouped under the unified term Computer, aiming to reduce redundancy and enhance interpretability. The procedure was conducted independently by the first two researchers experienced in qualitative data analysis [18,19] focusing on the preliminary data preparation stage rather than on the analytical categorization itself. Any differences identified during this stage concerned the harmonization of closely related terms, clarification of overlapping expressions, and standardization of similar conceptual references in students’ responses. These issues were resolved through discussion prior to the analytical phase and did not involve disagreements. The cleaned data thus served as the final corpus used for inductive categorization.

3.5. Analytical Framework

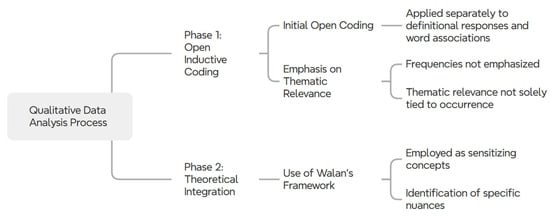

This study employed a systematic two-phase analytical process conducted using Microsoft Excel to examine students’ AI perceptions while maintaining both empirical openness and theoretical grounding. The use of Microsoft Excel was selected as it provided transparency, ease of reproducibility, and efficient organization, filtering, and triangulation of qualitative data [20]. The subsequent sections describe the two analytical phases through which data were organized and theoretically interpreted. An overview of this qualitative data analysis process is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Overview of the Qualitative Data Analysis Process.

3.5.1. Phase 1: Open Inductive Coding

Initial open coding [21] was applied separately to definitional responses and word associations. The former were analyzed to identify conceptual categories and functional meanings, while the latter were grouped into semantic clusters based on similarity. This inductive process involved iterative reading, constant comparison across data segments, and the progressive refinement of codes to capture emerging meanings [22]. Through memoing and reflection, initial codes were reviewed and consolidated into more abstract patterns that informed subsequent thematic integration. Consistent with the study’s approach, frequencies were not emphasized, as thematic relevance is not solely tied to occurrence [23].

3.5.2. Phase 2: Theoretical Integration

Emerging themes then were mapped onto Walan’s [1] four-dimensional framework which was employed as a set of sensitizing concepts rather than fixed categories [12]. This process enabled both alignment with the existing model and identification of specific nuances [24,25]. In line with the Five-Phase Process of Qualitative Data Analysis proposed by Bingham [22], this stage involved interpreting inductively derived themes through theoretical and conceptual lenses to achieve a transparent and theory-informed integration of findings.

3.6. Final Coding Framework

The final coding framework, summarized in Table 1, illustrates the hierarchical organization of dimensions and categories and served as the analytical foundation for the presentation of results. In line with the use of sensitizing concepts, when student responses exhibited characteristics of multiple categories, coders identified the primary or most prominent conceptual dimension emphasized in the response. For example, a response stating “the ability of computers or robots to learn and solve problems” (Student 201) was coded under “Autonomous Learning Systems” because the central emphasis was on learning capability, with computers and robots serving as the medium rather than the defining feature. In contrast, a response describing “a computer that thinks and responds like a human” (Student 3) was coded under “Computational Systems” because the focus was on cognitive processing rather than adaptive learning. This interpretive decision-making was guided by the consensus discussions during the sample joint coding phase, ensuring consistent identification of each response’s dominant thematic focus without treating numerical intercoder coefficients as a primary quality criterion.

Table 1.

Coding Framework with Category Definitions and Key Distinguishing Features.

3.7. Research Quality

Research quality was addressed through procedures ensuring dependability, credibility, and confirmability [26]. Dependability was supported by standardized research protocols across schools and joint coding of 22% of responses (n = 50) by two researchers to ensure procedural consistency. Τhis joint coding functioned as a negotiated-agreement process: disagreements were discussed, code definitions and decision rules were refined, and a shared set of analytic guidelines was documented before proceeding. After establishing shared analytical guidelines through discussion and consensus, the second author conducted the complete coding of the remaining dataset following the agreed criteria [27,28]. In line with contemporary debates in qualitative methodology, the study prioritized transparency of the coding frame and decision rules over reporting a single numerical intercoder reliability coefficient [29]. Credibility was enhanced through data (definitions and word-associations) and investigator triangulation, reducing potential bias and supporting authentic representation of students’ perspectives. Confirmability was established by maintaining systematic analytic memos and preserving students’ original Greek expressions, providing a transparent audit trail. All the aforementioned procedures were consistent with contemporary guidelines for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research [29,30].

4. Results

All 229 sixth-grade students who participated in the study provided valid responses. Response quality varied considerably, ranging from single-word answers to detailed multi-sentence explanations, with single-word responses appearing primarily in word association items and more elaborate descriptions observed in definitional responses. All student answers were translated from Greek into English for publication purposes using Anthropic Claude v3.7, with manual unit-by-unit verification (sentences and single-word responses) of the entire dataset to ensure semantic accuracy and preservation of linguistic nuance.

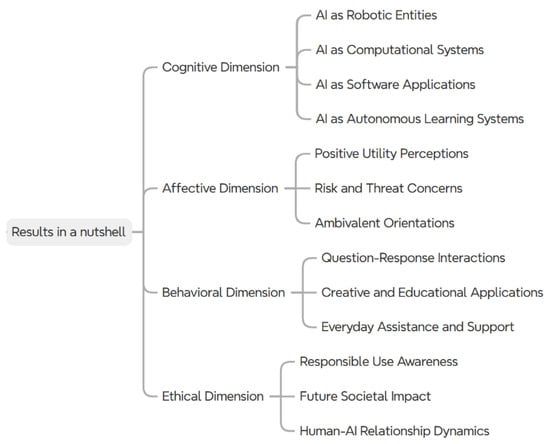

The results are presented according to the four analytical dimensions that guided the study—cognitive, affective, behavioral, and ethical. A summary of all conceptual categories across the four dimensions is presented in Figure 3. This structure reflects the inductive development of categories that were subsequently organized into these theoretical dimensions, allowing for an integrated interpretation of students’ conceptual, emotional, behavioral, and moral understandings of AΙ.

Figure 3.

Summary of the conceptual categories derived from students’ responses across Walan’s [1] four dimensions.

4.1. Cognitive Dimension: Students’ Understanding of AI as Technology

Analysis of definitional responses revealed four primary conceptual categories within the Cognitive Dimension, illustrating how Greek primary students conceptualize AΙ. These categories encompassed perceptions of AI as (1) robotic entities, (2) computational systems, (3) software applications, and (4) autonomous learning systems.

4.1.1. AI as Robotic Entities

Students frequently characterized AI as robotic entities possessing physical embodiment and human-like capabilities. Representative responses included: “I believe that AI is robots that move like humans” (Student 1); “Robots and generally artificial bodies” (Student 94); “A robot made by humans and smarter than humans” (Student 27); “Robots that can do housework and cooking work” (Student 99); “Robots and whatever it can do with its hands” (Student 20).

4.1.2. AI as Computational Systems

Many students conceptualized AI as sophisticated computer systems or machines. Responses included: “A computer that thinks, distinguishes objects and answers questions” (Student 3); “Something like a machine that knows all the answers to our questions” (Student 4); “A gigantic computer that gives us information” (Student 60); “An automatic computer that can do and answer everything” (Student 71).

4.1.3. AI as Software Applications

A substantial number of students referenced specific AI tools and applications reflecting the rapid commercialization of AI tools. Students stated: “An application related to electricity that helps with schoolwork and questions, like ChatGPT” (Student 18); “Various applications like AI which is an artificial friend you can ask various questions” (Student 112); “ChatGPT and Lisari” (Student 155); “All electronic programs like ChatGPT that help us solve daily life problems” (Student 66).

4.1.4. AI as Autonomous Learning Systems

Students described AI as systems capable of independent learning and adaptation, indicating emerging awareness of adaptive capabilities, though not necessarily deep technical understanding. Responses included: “A program that can learn and change appropriately with the information it receives from humans” (Student 21); “The ability of computers or robots to learn, think, and solve problems like human minds” (Student 201); “Programming that has its own thinking” (Student 111); “An artificial brain that is made to help humans in daily life” (Student 134).

Word associations reflected these conceptualizations across all four categories, with frequent references to robots and physical forms, computational systems, branded applications, and adaptive capabilities. Representative associations included: “robot, intelligence, AI” (Student 14), “computer, technology, robot, ChatGPT, AI” (Student 78), “technology, robotics, robot, informatics, programming” (Student 130), and “robot, code, answers, processing, adaptation, algorithm” (Student 189). Notably, word associations revealed stronger brand-specific awareness than definitional responses, with frequent mentions of “Tesla, ChatGPT, Neuralink AI” (Student 44) and “ChatGPT, Microsoft, Siri, Gemini, AI, Apple” (Student 154).

4.2. Affective Dimension: Emotional Responses and Attitudes Toward AI

Student responses included emotional references of varying orientation—positive, negative, and ambivalent—which correspond to Walan’s [1] affective dimension and illustrate the range of students’ emotional positions toward AI technology.

4.2.1. Positive Utility Perceptions

Many students expressed positive attitudes toward AI, emphasizing its helpful nature in educational and daily contexts. Representative responses included: “Entertaining, it can create any image you want and if you have any question it answers and always helps you” (Student 5); “Like an assistant or friend that can help you with support and give you ideas” (Student 33); “A tool that facilitates our daily lives and helps us with many things” (Student 85); “A great help for humans and for a better life” (Student 108).

4.2.2. Risk and Threat Concerns

Students expressed fears about AI’s potential negative impacts. Responses included: “I believe robots should not exist because they are dangerous” (Student 47); “I fear that it might one day conquer the world” (Student 170); “It should not have been created because in the future it might conquer the world” (Student 152); “Something that if it develops too much will cause many disasters” (Student 227).

4.2.3. Ambivalent Orientations

Students demonstrated simultaneous acknowledgment of both positive and negative AI characteristics. Examples included: “AI can do us both good and bad depending on what AI we’re talking about” (Student 7); “Sometimes very useful in our days but sometimes can become very bad” (Student 146); “I think it will help partially but it’s not ruled out that it could prove fatal” (Student 182).

Word association data triangulated these emotional responses across all three affective orientations. Positive utility associations spanned expressions of helpfulness and enthusiasm (“help, fantasy, technology” [Student 5]; “utility, intelligence, tool, ease” [Student 3]; “smart, assistant, fast answers” [Student 17]). Risk and threat concerns were evident in darker associations (“problems, bad, powerful” [Student 6]; “robot, exterminator, apocalypse” [Student 46]; “total destruction” [Student 140]). Ambivalent orientations combined both perspectives (“domination, help, third world war” [Student 146]; “facilitation, help, fear, worry” [Student 97]).

4.3. Behavioral Dimension: AI Usage and Interaction Patterns

Students described various forms of current and anticipated AI engagement behaviors, reflecting both established patterns from previous research and contemporary interaction modalities.

4.3.1. Question-Response Interactions

Students frequently described AI through interactive question-answering capabilities. Representative responses included: “You can ask it anything and it will answer” (Student 31); “A robot you can ask various things” (Student 12); “Something that answers immediately to whatever you ask” (Student 229); “A system that can answer all your questions” (Student 192).

4.3.2. Creative and Educational Applications

Students demonstrated awareness of AI’s creative and educational capabilities. Responses included: “Can create any image you want and help with studies” (Student 5); “Helps with homework and exercises” (Student 132); “Can generate images, solve problems and generally help humans facilitate their daily life” (Student 79); “Programs in robots or computers that help you solve questions or create any image or video” (Student 185).

4.3.3. Everyday Assistance and Support

Students conceptualized AI as providing comprehensive daily life support. Examples included: “A digital assistant that can help you with whatever you want” (Student 119); “A system that facilitates people’s lives” (Student 210); “A tool created by humans to help them with daily and normal problems” (Student 226); “An assistant that knows everything and can help you with whatever you need” (Student 198).

Word associations reflected these behavioral dimensions across all three categories. Interactive capabilities were emphasized through direct communication patterns (“AI, ChatGPT, questions, answers” [Student 70]; “fast answers” [Student 17]; “answers to questions” [Student 87]). Creative and educational applications emerged in references to content generation and learning support (“ChatGPT, lessons, teacher” [Student 18]; “homework solutions, help with questions” [Student 155]; “assignments” [Student 185]). Everyday assistance was evident in utility-focused associations (“utility, intelligence, tool, ease” [Student 3]; “convenience, human life” [Student 35]; “assistant, omniscient, helpful” [Student 171]).

4.4. Ethical Dimension: Moral and Social Considerations

Students incorporated ethical considerations into their definitional responses, indicating an awareness of moral aspects associated with AI that extends beyond mere functional understanding.

4.4.1. Responsible Use Awareness

Students demonstrated awareness of responsible AI use. Representative responses included: “However, it is very important that we use it correctly” (Student 3); “We need to be careful what we do because bad people can use AΙ, for example hackers to harm and deceive people” (Student 30); “Some children use it for cheating but it doesn’t always have correct answers” (Student 112).

4.4.2. Future Societal Impact

Students expressed understanding of AI’s long-term societal implications. Responses included: “In the future will be very important in life and I believe it will be in our daily routine” (Student 77); “They say that in the future it will replace people’s jobs” (Student 85); “A program that in the coming years will dominate the whole world” (Student 178); “The future of humanity and a great ally for now” (Student 145).

4.4.3. Human-AI Relationship Dynamics

Students demonstrated awareness of the constructed nature of AI and human agency in its development. Examples included: “We have created and programmed them” (Student 41); “A creation of humans that helps them in their work and generally in their life” (Student 169); “The intelligence of machines created by humans to serve humans themselves” (Student 206); “A human creation that helps people when they need help sometimes” (Student 217).

Ethical concerns appeared in word associations, predominantly through future societal impact references (“domination, help, third world war” [Student 138]; “world destruction, help, world domination” [Student 71]; “future, robot, destruction, technology” [Student 182]; “robot, future, world upgrade, future destruction” [Student 125]. Human-AI relationship dynamics emerged in creation-oriented associations (“programming, experiments, technology” [Student 169]; “human, intelligence, robot” [Student 19], supporting the spontaneous ethical reasoning identified in definitional responses.

5. Discussion and Implications

The purpose of this study was to explore how Greek sixth-grade students conceptualize AI before receiving any formal instruction, with the broader aim of informing age-appropriate approaches to AI literacy in primary education. Data were collected from written definitional responses and word associations provided by 229 students across seven public schools in Athens. The material was analyzed qualitatively through a two-phase process of open inductive coding followed by theoretical integration using Microsoft Excel. Walan’s [1] four-dimensional framework—cognitive, affective, behavioral, and ethical—served as an interpretive lens to organize and interpret the emergent categories. The following discussion interprets the findings with reference to each research question and compares them with previous international studies, aiming to clarify which aspects of students’ perceptions are shared across contexts and which appear specific to the Greek sample.

Regarding the cognitive dimension, students described AI in terms that combined human-like cognition with computational processes. They viewed AI as capable of thinking, learning, and adapting, and often connected these ideas with specific technologies such as ChatGPT, Tesla, or Neuralink. This pattern aligns with findings from Swedish and Turkish students, who also described AI as “brain-like” or autonomous [1,6]. In contrast with earlier work where references were largely generic [4], these responses included direct naming of contemporary systems, showing that recent generative AI tools have entered students’ linguistic repertoire. Students’ emphasis on functions such as answering, creating, and problem solving reflects functional patterns of understanding that have also been described in other European studies [2,4], where AI was similarly portrayed as both computational and adaptive. Anthropomorphic expressions such as “robots that move like humans” or “an artificial brain” appeared frequently, corresponding to Swedish and Turkish students’ depictions of AI as embodied or human-like [1,6]. Dutch students, however, did not use the term robot in abstract conceptualizations [2], suggesting variation in how embodiment is represented across contexts.

Within the affective dimension, students’ emotional references ranged from curiosity and enjoyment to unease and caution. Positive expressions emphasized AI’s usefulness in learning and daily activities, while negative comments centered on fears of dominance or loss of control. This ambivalence is consistent with findings from Dutch and Swedish studies [1,2], where mixed emotional evaluations were also present. Some responses reflected familiar media narratives, such as robots taking over the world, echoing motifs documented in previous European research [1,6]. The coexistence of enthusiasm and concern indicates that students’ emotional conceptions of AI draw both on everyday interactions and on fictional portrayals circulating through popular culture.

In the behavioral domain, students described using AI mainly through voice assistants, educational platforms, and games, suggesting exploratory rather than systematic interaction, a pattern comparable to Finnish and Dutch data [2,6]. Some participants mentioned using generative tools for creative purposes, such as producing images or solving tasks, reflecting awareness of recent technological developments. Compared with Dutch students who articulated algorithmic manipulation strategies (e.g., “when you press ‘not interested’ you will see those videos less”) [2,6], Greek students focused more on visible outcomes of AI rather than on underlying algorithms. This contrast may reflect contextual differences in students’ exposure to digital recommendation systems or explicit algorithmic language.

Concerning the ethical dimension, students referred to issues such as responsible use, fairness, privacy, and employment. Several mentioned that humans create and can control AI systems, a point also noted in Walan’s [1] Swedish dataset. Ethical meanings appeared not only in definitional responses but also in word associations such as responsibility, rules, respect, and humans, indicating intuitive links between AI and moral or social responsibility. Although brief and largely implicit, these references reveal that ethical reasoning emerges gradually and becomes more articulated during late primary school years, aligning with international findings that children spontaneously mention moral aspects when discussing technology. Comparatively, several cross-national patterns were evident. Anthropomorphic conceptions and notions of AI autonomy recurred across Greek, Swedish, and Turkish contexts [1,6] while Finnish data contained fewer references to learning or adaptation [4]. Educational applications such as AI’s ability to answer questions were commonly mentioned in Greece, Turkey, and Sweden [1,7]. Emotional ambivalence—curiosity mixed with apprehension—was also a shared feature across [1,2].

At the same time, certain context-specific features characterized the Greek sample. Students frequently referred to current generative systems (e.g., ChatGPT, Tesla, Neuralink), a tendency less visible in earlier or contemporaneous European datasets. Robotic imagery remained prominent in Greek data, while explicit algorithmic strategies—described by Dutch participants [2]—were not observed. These differences may stem from variation in media exposure, everyday technological environments, or language use surrounding AI.

Finally, the data hint at temporal shifts in children’s perceptions of AI. Earlier studies focused largely on voice assistants such as Siri and Alexa [4], whereas more recent datasets—including the present one—show references to generative AI (e.g., ChatGPT), consistent with Walan’s [1] observations of similar developments in Sweden. Creative uses (e.g., producing images or videos) also appeared here and in Turkish samples linking AI with art and imagination [7]. Such findings indicate that children’s representations of AI evolve alongside technological advances and shifts in the tools embedded in everyday life.

The findings indicate that many students already possess an emerging conceptual understanding of AI, providing a valuable foundation for the design of age-appropriate educational initiatives. Early engagement with AI-related topics can help clarify distinctions between concepts that students often conflate—such as robotics and AI—while illustrating their points of intersection [31]. Schools play a pivotal role in shaping students’ AI literacy and in addressing misconceptions before they become entrenched [32]. Students’ misunderstandings tend to be superficial rather than fundamental [4], suggesting that accessible explanations of how AI functions, supported by concrete and relatable examples, can enhance comprehension and interest.

Educational programs should therefore emphasize the functional diversity and societal relevance of AI applications, linking them with familiar contexts such as communication, creativity, and learning support. Introducing AI literacy at an early stage can also promote awareness of the human characteristics often attributed to AI, fostering informed reflection rather than uncritical anthropomorphism [33].

The coexistence of positive and negative associations in students’ perceptions provides a natural entry point for ethical discussion in the classroom. Encouraging students to examine both the opportunities and limitations of AI aligns with current frameworks of AI literacy [34,35,36]. The educational objective is not to cultivate uniformly positive views but to develop realistic and critically informed conceptions of AI that enable learners to participate thoughtfully in societal and ethical discussions about its use [37].

6. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Research

This study provides a qualitative account of how Greek upper primary students conceptualize Artificial Intelligence across cognitive, affective, behavioral, and ethical dimensions prior to any formal instruction. The study contributes new cross-cultural evidence to the international AI literacy literature by examining these four dimensions in a previously underexplored national context. The findings demonstrate that students’ perceptions of AI are multifaceted, blending functional understandings of technology with emotional ambivalence, everyday usage narratives, and spontaneous ethical reflections. This complexity underscores the importance of approaching AI literacy not as a corrective response to misconceptions, but as an educational opportunity to build upon children’s already emerging conceptual frameworks.

From an educational perspective, the study highlights the need for human-centered, developmentally appropriate AI curricula that address cognition, emotion, action, and ethics in integrated ways. Students’ intuitive references to responsibility, societal impact, and human agency indicate early readiness for critical technological engagement, even at the primary level. AI literacy initiatives should therefore extend beyond technical familiarity to include reflective discussion of the values, limitations, and social consequences of AI technologies. Such holistic approaches can contribute to the cultivation of informed, ethically grounded digital citizens capable of meaningful participation in an AI-shaped society.

As a qualitative exploration, this study aimed to generate context-rich, transferable insights rather than broad generalizations. The sample—comprising students from urban schools in Athens—reflects a specific sociocultural environment that may differ from those in other regions or educational systems. Consequently, future research could adopt comparative or mixed-method designs that include rural, multilingual, or socioeconomically diverse contexts to better understand the variability of students’ perceptions. Given the rapid evolution of generative AI tools, it would also be valuable to examine how students’ conceptions change over time as they encounter new technologies both inside and outside the classroom.

Methodologically, further work could extend beyond short written responses to incorporate multimodal techniques such as drawings, interviews, and classroom observations. These approaches could provide deeper insight into how children’s ideas and emotional responses develop in relation to AI. Additionally, investigating teachers’ perceptions and instructional practices would complement student-centered findings, offering a fuller picture of how AI literacy can be meaningfully integrated into primary education.

Taken together, such future studies could inform the design of AI literacy curricula that holistically address the cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and ethical dimensions of students’ engagement with AI, fostering balanced, informed, and responsible interaction with intelligent technologies from an early age.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.K., G.C. and P.A.; methodology, G.C.; validation, G.C., K.K. and P.A.; formal analysis, G.C. and K.K.; investigation K.K. and G.C.; resources G.C. and K.K.; writing—original draft preparation, G.C. and K.K.; writing—review and editing, G.C., K.K. and P.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the research protocol was approved by the Directorate of Primary Education of D’ Athens (D.P.E. D’ Athens), Ministry of Education, Religious Affairs and Sports (Project identification code: 4830), on 2 May 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation in the study was obtained from all subjects involved.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participating teachers for their valuable contributions to this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

References

- Walan, S. Primary School Students’ Perceptions of Artificial Intelligence–for Good or Bad. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2025, 35, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeg, D.M.; Avraamidou, L. Young Children’s Understanding of AI. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2025, 30, 10207–10230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewersdorff, A.; Zhai, X.; Roberts, J.; Nerdel, C. Myths, Mis- and Preconceptions of Artificial Intelligence: A Review of the Literature. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2023, 4, 100143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertala, P.; Fagerlund, J.; Calderon, O. Finnish 5th and 6th Grade Students’ Pre-Instructional Conceptions of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Their Implications for AI Literacy Education. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2022, 3, 100095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Kwon, K.; Ottenbreit-Leftwich, A.; Bae, H.; Glazewski, K. Exploring Middle School Students’ Common Naive Conceptions of Artificial Intelligence Concepts, and the Evolution of These Ideas. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 9827–9854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalemkuş, J.; Kalemkuş, F. Primary School Students’ Perceptions of Artificial Intelligence: Metaphor and Drawing Analysis. Eur. J. Educ. 2025, 60, e70007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oruc, T.; Korkmaz, O.; Kurt, M. Primary School Students’ Views on Artificial Intelligence. Int. J. Technol. Educ. Sci. 2024, 8, 583–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitcham, C. Thinking Through Technology: The Path Between Engineering and Philosophy; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ankiewicz, P. Alignment of the traditional approach to perceptions and attitudes with Mitcham’s philosophical framework of technology. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2018, 29, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, W.; Bialik, M.; Fadel, C. Artificial Intelligence in Education Promises and Implications for Teaching and Learning; Center for Curriculum Redesign: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Asghar, M.Z.; Duah, K.A.; Iqbal, J.; Järvenoja, H. Evidence from West Africa on the Interplay of Affective Behavioral Cognitive and Ethical Dimensions of AI Literacy in Ghanaian and Nigerian Universities. Discov. Comput. 2025, 28, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumer, H. What Is Wrong with Social Theory? Am. Sociol. Rev. 1954, 19, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, I. Qualitative Data Analysis: A User Friendly Guide for Social Scientists; Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cadime, I.; Mendes, S.A. Psychological Assessment in School Contexts: Ethical Issues and Practical Guidelines. Psicol. Reflexão Crít. 2024, 37, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelöw, A.; Psouni, E. Participatory Research With Children: From Child-Rights Based Principles to Practical Guidelines for Meaningful and Ethical Participation. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2025, 24, 16094069251315391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraenkel, J.R.; Wallen, N.E. How to Design and Evaluate Research in Education; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Henrich, M.; Formella-Zimmermann, S.; Schneider, S.; Dierkes, P.W. Free Word Association Analysis of Students’ Perception of Artificial Intelligence. Front. Educ. 2025, 10, 1543746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Moncada, M. Should We Use NVivo or Excel for Qualitative Data Analysis? BMS Bull. Sociol. Methodol. Bull. Methodol. Sociol. 2025, 165–166, 186–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bingham, A.J. From Data Management to Actionable Findings: A Five-Phase Process of Qualitative Data Analysis. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2023, 22, 16094069231183620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandelowski, M. Focus on Research Methods Real Qualitative Researchers Do Not Count: The Use of Numbers in Qualitative Research. Res. Nurs. Heal. 2001, 24, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drisko, J.W. Transferability and Generalization in Qualitative Research. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2025, 35, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, S.B. Situating Sensitizing Concepts in the Constructivist-Critical Grounded Theory Method. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2022, 21, 16094069211061957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. Research Methods in Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, C.; Joffe, H. Intercoder Reliability in Qualitative Research: Debates and Practical Guidelines. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2020, 19, 1609406919899220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M. What Is Quantitative Research? An Overview and Guidelines. Australas. Mark. J. 2025, 33, 325–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, A.M.; Jen, E. The Editorial Word: Trustworthiness. J. Adv. Acad. 2024, 35, 718–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cave, S.; Coughlan, K.; Dihal, K. “Scary Robots” Examining Public Responses to AI. In Proceedings of theAIES 2019-Proceedings of the 2019 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, Honolulu, HI, USA, 27–29 January 2019; pp. 331–337. Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/proceedings/10.1145/3306618 (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Sperling, K.; Stenliden, L.; Mannila, L.; Hallström, J.; Nordlöf, C.; Heintz, F. Perspectives on AI Literacy in Middle School Classrooms: An Integrative Review. Postdigital Sci. Educ. 2025, 7, 719–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, G.; Nuñez Castellar, E.; IJsselsteijn, W. An Exploratory Study Into the Impact of AI Literacy Training on Anthropomorphism and Trust in Conversational AI. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 2025, 15820 LNAI, 301–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsidis, K.; Dima, A. Integrating AI Tools and Drama Pedagogy in Digital Classrooms to Foster Critical Thinking and Inclusion in Primary Education. Adv. Mob. Learn. Educ. Res. 2025, 5, 1524–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chee, H.; Ahn, S.; Lee, J. A Competency Framework for AI Literacy: Variations by Different Learner Groups and an Implied Learning Pathway. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2025, 56, 2146–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsidis, K.; Anastasiades, P. E-Learning Open Seminar on “Human–Centered Artificial Intelligence in Education: From Theory to Practice”. Int. J. Educ. Technol. Learn. 2025, 18, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, M.; Jong, M.S.Y.; Dai, Y.; Lau, W.W.F. Students as AI Literate Designers: A Pedagogical Framework for Learning and Teaching AI Literacy in Elementary Education. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 2025, 1, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.