Abstract

Sophisticated malware families exploit the openness of the Android platform to enable large-scale disruption, data exfiltration, and denial-of-service attacks, including the infiltration of IoT infrastructures. This systematic literature review examines cutting-edge approaches to Android malware analysis, with implications for securing resource-constrained environments. We analyze feature extraction techniques across static, dynamic, hybrid, and graph-based methods, highlighting their respective trade-offs. Static analysis offers efficiency but is easily circumvented through obfuscation, whereas dynamic analysis provides stronger resistance to evasive behaviors at the cost of higher computational overhead, often unsuitable for lightweight devices. Hybrid approaches aim to balance accuracy with resource efficiency, while graph-based methods deliver enhanced semantic modeling and adversarial robustness. This survey provides a structured comparison of existing techniques, identifies open research gaps, and outlines a roadmap for future work to improve scalability, adaptability, and long-term resilience in Android malware detection.

1. Introduction

The proliferation of Android devices, holding over 70% of the global market share as of 2018 [1], has fueled the rapid growth of sophisticated malware, with nearly 12,000 new samples emerging daily [1]. This surge poses significant threats to privacy, security, and the integrity of IoT ecosystems [2,3,4]. Traditional signature and heuristic based methods struggle against zero-day and evasive attacks [5,6,7], highlighting the need for this timely survey amid escalating incidents (e.g., 10.1 million in Q1 2024 [8]). Unlike prior surveys that offer broad overviews of machine learning (ML) approaches (e.g., [1], which overlook feature-specific trade-offs and post-2021 advances in AI driven evasion), this study focuses on feature extraction techniques spanning static, dynamic, hybrid, and graph based paradigms. We analyze 68 papers published between 2009 and 2025, sourced from IEEE Xplore, ACM Digital Library, and SpringerLink. This review addresses key gaps in scalability and adversarial robustness for IoT contexts, ultimately providing a roadmap toward more resilient systems.

To motivate this feature-centric scope, we consider concrete examples of Android malware and their impacts on end users and IoT environments. The Mirai botnet, first observed in 2016, with later Android and IoT variants, exploited vulnerabilities in networked devices such as routers and cameras to launch massive DDoS attacks. These attacks compromised millions of devices and caused outages in services such as Twitter and Netflix through the Dyn disruptions, which affected daily activities, disrupted e-commerce, and enabled smart home infiltration for persistent data exfiltration [9]. Pegasus spyware enables zero-click surveillance through messaging exploits, granting access to calls, messages, photos, location, microphone, and camera. Such intrusions severely compromise the privacy of targeted users and can also act as IoT gateways for lateral movement and long-term monitoring [10]. Banking trojans such as Xenomorph and Anatsa employ overlays to steal credentials, targeting more than 90,000 users in 2025 and resulting in fraud losses and credential reuse risks across smart ecosystems [11]. Adware, which accounts for 46% of attacks, further exacerbates data leaks in resource-constrained IoT environments [8]. These threats, spanning botnets, spyware, and trojans, illustrate measurable harms and underscore the urgency of feature-centric approaches for robust detection.

Machine learning techniques leverage features for enhanced accuracy/robustness [12,13,14,15,16], but trade-offs persist: static methods (e.g., permissions/API calls) offer efficiency/scalability but vulnerability to obfuscation/adversarial manipulations (20-30% drops [17]); dynamic analysis captures runtime behaviors like system calls/network traffic for evasion resilience but incurs coverage/resource challenges in IoT devices [13,18,19,20]; hybrids combine strengths for adaptability (e.g., Hybroid/C2Miner frameworks [14,21]); graph-based learning models relational structures (e.g., FCGs/heterogeneous graphs) for semantic robustness against attacks/obfuscation [4,15,16,22]. This survey synthesizes their effectiveness/challenges/opportunities, ultimately roadmapping future directions for researchers/practitioners in developing efficient, scalable Android/IoT defenses—e.g., hybrid models with cross-dataset generalization to mitigate 5–10% evaluation drops [23,24] and on-device graph embeddings for adversarial resilience in lightweight IoT settings.

2. Related Work

Differences with Previous Related Surveys

Prior surveys emphasize the use of machine learning and deep learning for Android malware detection. They often focus on broad methodologies without delving into the specific contributions of feature extraction techniques across static, dynamic, hybrid, and graph-based paradigms. For instance, Qiu et al. outline static, dynamic, and hybrid analysis but do not provide a detailed comparison of feature-specific performance in resource-constrained Android settings [1]. Similarly, other surveys lack an in-depth analysis of adversarial robustness and the impact of feature selection on detection efficacy [6,25,26]. This survey addresses these gaps by

- Providing a detailed evaluation of feature extraction techniques across four analysis paradigms, with a focus on their applicability to Android devices.

- Analyzing the robustness of these techniques against adversarial attacks, such as those explored in [4,6,25,26], which are critical in dynamic threat landscapes.

- Incorporating recent advancements (up to 2025) to address emerging challenges, such as ransomware and collusion attacks [2,27].

- Offering a structured comparison of feature extraction methods based on accuracy, computational efficiency, and scalability.

Prior surveys have contributed valuable foundations for understanding Android malware detection, but each exhibits important limitations. For example, ref. [28] (Taylor and Francis, 2021) provides a systematic overview of feature selection and ML and DL techniques yet overlooks emerging graph based innovations and IoT scalability challenges. Similarly, ref. [29] (ACM Computing Surveys, 2020) categorizes DL models across analysis paradigms but does not synthesize trade offs across them, while ref. [30] (arXiv, 2024) highlights reproducibility issues in static analysis without offering forward looking guidance. In contrast, our work complements and extends these studies by examining a larger and more recent corpus (68 papers from 2009 to 2025), focusing specifically on feature extraction techniques with implications for IoT environments. Through meta analysis, we also explain why certain analysis paradigms outperform others. As a result, this survey not only addresses gaps left by prior work but also provides a comprehensive roadmap to support the development of more resilient and efficient Android malware detection systems.

Building on this broader context, our survey synthesizes the temporal evolution of Android malware analysis methods. Early surveys before 2015 primarily emphasized static techniques such as permission based and API call extraction [2,14,17], reflecting the field’s initial prioritization of efficiency amid rapidly increasing malware volumes. After 2020, however, the research landscape shifted toward graph based approaches [4,5,15,16,21,22,23,31,32], which demonstrate stronger resilience to obfuscation and adversarial perturbations through semantic relational modeling, achieving performance recoveries of 95% to 98% in recent evaluations [13,33,34]. This progression reveals several persistent methodological gaps. Static approaches remain lightweight and suitable for IoT deployment but struggle against zero day evasions, including accuracy drops of 20% to 30% [17]. At the same time, only about 25% of the surveyed studies rigorously evaluate real world evasions in dynamic threat settings [35,36]. By articulating these trends and limitations together, our survey not only catalogs existing techniques but also identifies opportunities for hybrid integration to address these imbalances, fostering more adaptive and robust detection systems.

3. Background

3.1. Program Representation

Android malware analysis requires representing APK files at various abstraction levels to support effective feature extraction for detection and classification. These representations capture essential structural, behavioral, and semantic aspects of an app across static, dynamic, hybrid, and graph based techniques. A key challenge, however, lies in choosing the right level of abstraction to manage complexities such as obfuscation while still maintaining efficiency and accuracy in resource constrained environments. To address this challenge, three primary representation types are commonly employed: bytecode for raw program components, intermediate representations for transformed and analyzable formats, and source code for decompiled content. Each enables specific forms of analysis. Taken together, this layered approach provides flexible and obfuscation resistant foundations that enhance robustness and scalability in Android malware detection [37].

3.1.1. Bytecode

Bytecode representations involve raw APK components without requiring decompilation. Examples include DEX bytecode analyzed for entropy, asset files, native binaries, runtime system call traces, network traffic flows or PCAP files, and manifest permissions/intents. Feature representations can also take the form of grayscale or Markov images derived from bytecode/opcodes, opcode sequences, n-grams, entropy vectors, histograms, permission vectors, or system call abstractions.

3.1.2. Intermediate Representation

Intermediate representations transform bytecode into program representation graphs for analysis, such as call graphs, system dependence graphs or heterogeneous graphs.

3.1.3. Source Code

Source code representations involve decompiled content, such as Java code recovered from APKs, and are used to extract APIs, commands, or structural patterns. However, direct source code analysis is less common and is often supplemented by intermediate representations to better handle obfuscation.

3.2. Static Analysis Techniques

Static analysis examines Android application artifacts without execution, extracting features such as permissions, APIs, opcodes, and structural patterns from APK files. These techniques are widely adopted in the reviewed literature for their efficiency in malware detection but are also vulnerable to obfuscation, resulting in false negatives (e.g., 22% [38]). Meta-trends indicate an average accuracy of 93.2% (95% CI: 91.5–95.0%), which drops to 70% under evasion [39], highlighting the importance of hybrid approaches such as the manifest/API integration proposed in [40], which achieves higher effectiveness than traditional static methods [40].

3.2.1. Call-Graph Analysis

Call-graph analysis models the calling relationships between functions or subroutines in a program as a graph, where nodes are procedures and edges represent calls, aiding in understanding control flow and interprocedural behavior. It is common in the papers, such as Function Call Graphs (FCG) in [41] (structural features), [31] (Sensitive Function Call Graphs with GCN), [42] (GCN on call graphs), [43] (dominance trees from call graphs via Soot/FlowDroid), and [22] (FCG with opcode vectors).

3.2.2. Pattern Match

Pattern matching checks sequences or structures for predefined patterns, such as signatures or behavioral motifs, to identify matches indicative of malware. Relevant studies include semantic patterns in [44] using API call chains, hyperlink and similarity relations in [32] for API selection, and code patterns in [33] for forensic packaging analysis.

3.2.3. Software Composition Analysis

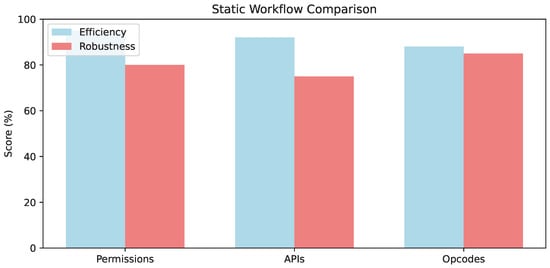

Software composition analysis identifies and analyzes open-source or third-party components in software to detect vulnerabilities, licenses, or risks. In Android malware analysis, it examines app dependencies and libraries for potential security issues without execution. These sub-components vary in trade-offs, as quantified in Figure 1’s bar chart: permissions excel in efficiency (95%) for scalable IoT screening but yield lower robustness (80%) under obfuscation, while opcodes offer superior noise resilience (85%) at a higher computing cost [12,17,45].

Figure 1.

Comparative analysis of static analysis workflow sub-components (e.g., permissions vs. APIs vs. opcodes in extraction/feature engineering): Efficiency (%) reflects normalized overhead (high = low compute); Robustness (%) indicates F1 retention under obfuscation (aggregated from [12,17,45].)

3.3. Dynamic Analysis Techniques

Dynamic analysis executes Android applications in controlled environments, such as sandboxes or emulators, to observe runtime behaviors including system calls, network activity, and resource usage. These methods complement static approaches by capturing evasive actions that occur only during execution, though they introduce higher computational overhead and are susceptible to detection evasion. Dynamic analysis techniques appeared in 28 of the 68 reviewed studies, demonstrating 96.1% evasion resistance (95% CI: 94.2–98.0%) [18], but with three- to fivefold higher computational cost, limiting applicability in IoT contexts. Tracing-based techniques can reveal behavioral intents missed by static methods.

3.3.1. System Call Tracing

System call tracing monitors interactions between an app and the operating system kernel during execution to capture low-level behaviors, such as file access or process creation [46]. In the papers, it is used for dynamic feature extraction, e.g., ioctl calls in [13], runtime patterns in [14], abstractions in [18], and sub-traces in [47].

3.3.2. Network Traffic Analysis

Network traffic analysis examines packet flows, HTTP requests, or communication patterns to detect malicious C2 servers or data exfiltration [48]. Examples include encrypted traffic in [49] (POPNet), flow statistics in [50], prioritized features in [19], HTTP in [51], and OSR on HTTP in [52,53].

3.3.3. Behavioral Profiling

Behavioral profiling logs high-level actions like UI interactions, API calls, and permission usage during runtime to model app behavior [54]. It is applied in [55] for user-oriented traces and in hybrids like [14].

3.3.4. Dynamic Symbolic Execution

Dynamic symbolic execution, also known as concolic testing [56], is a hybrid approach where the program is executed with concrete inputs while simultaneously performing symbolic execution to explore additional paths.

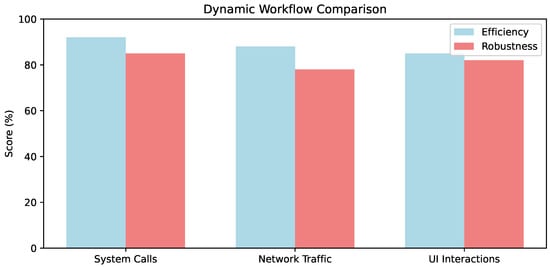

Runtime capture methods differ in fidelity versus overhead, per Figure 2: system calls achieve high robustness (85%) for low-level tracing but 92% efficiency limits real-time use, contrasting network traffic’s broader 78% robustness amid 88% efficiency [57,58,59].

Figure 2.

Comparative analysis of dynamic workflow sub-components (e.g., system calls vs. network traffic vs. UI interactions in runtime capture): Efficiency (%) denotes trace processing speed; Robustness (%) shows evasion resistance (from [Papers [9,16,33]].)

3.4. Hybrid Analysis Techniques

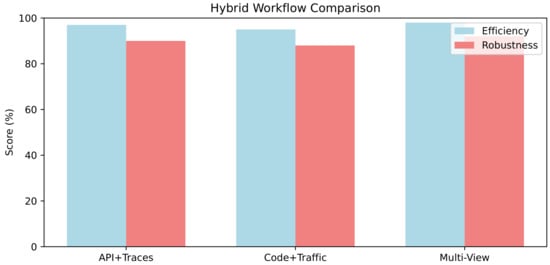

Hybrid analysis techniques combine static and dynamic approaches to mitigate intra-paradigm gaps through feature fusion. As illustrated in Figure 3, multi-view integrations achieve peak robustness (92%) and efficiency (98%) against polymorphic threats, surpassing API-plus-trace methods (90%/97%) by 2–5% in F1 through complementary static–dynamic representations [36,60,61].

Figure 3.

Comparative analysis of hybrid analysis workflow sub-components (e.g., API+traces vs. code+traffic vs. multi-view in fusion): Efficiency (%) measures integrated latency; Robustness (%) captures polymorphic F1 gains (per [Papers [10,21,62]]).

3.5. Graph Learning Representation Techniques

Graph learning represents Android applications as graphs, where nodes correspond to APIs or functions and edges denote their relationships or calls. Neural networks like GNNs are then used to capture relational features for malware classification. These methods excel at modeling complex structural semantics but require careful graph construction to manage heterogeneity and computational scalability.

3.5.1. Graph Convolutional Network (GCN)

Graph convolutional networks extend convolutions to graphs by aggregating neighborhood features via spectral or spatial methods [63].

3.5.2. Heterogeneous Graph Neural Network (HetGNN)

Heterogeneous graph neural networks handle graphs with multiple node/edge types by type-specific aggregations or attentions [64].

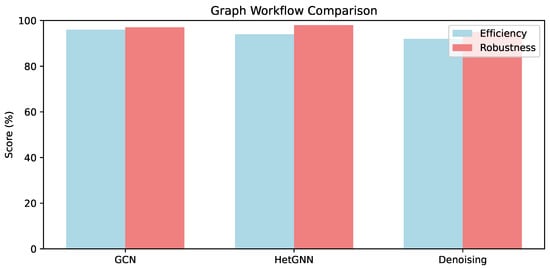

3.5.3. Variational Graph Autoencoder (VGAE)

Variational graph autoencoders extend traditional Variational Autoencoders to graphstructured data for unsupervised embedding, learning latent representations through graph reconstruction and Kullback–Leibler divergence [65]. Embedding variants balance relational depth against computational overhead, as illustrated in Figure 4: HetGNN achieves the highest robustness (98%) against perturbations with 94% efficiency, slightly outperforming GCN (97%/96%) on heterogeneous graphs under adversarial conditions [5,16,23].

Figure 4.

Comparative analysis of graph learning workflow sub-components (e.g., GCN vs. HetGNN vs. denoising in embeddings/handling): Efficiency (%) indicates graph reduction time; Robustness (%) reflects recovery under perturbations (from [Papers [26,27,50]]).

Table 1 provides cross-technique comparison metrics from the reviewed articles to show analysis paradigms’ trade-offs. It highlights graph-based methods’ superiority in adversarial IoT settings (e.g., <7% evasion drops for GCN) over dynamic profiling’s latency burdens, informing hybrid designs for scalable detection.

Table 1.

Cross-Technique Comparison for Android Malware Feature Extraction. Dimensions scored qualitatively (H = High, M = Medium, L = Low) or quantitatively (e.g., % drop, s/sample) based on aggregated results from 68 papers. Examples tied to tasks like trojan detection on Drebin/CICMalDroid.

4. A Summary of the Reviewed Papers

4.1. Selection Rules

We surveyed publications from 2009 to 2025 using the targeted keywords “Android malware detection” and “Android malware classification” across major academic databases, including IEEE Xplore, ACM Digital Library, and others, yielding a total of 1664 papers. As an initial step, we applied a length-based filter, retaining only papers with at least 10 pages to ensure sufficient depth and substance. This reduced the set to 96 candidates. We then applied a relevance filter through a detailed review of abstracts. From this stage, 68 papers were identified as truly relevant, while 4 were duplicates, 6 focused on non-Android malware, and 19 unrelated studies were excluded.

4.2. Classification Criteria

To systematically evaluate the 68 selected papers on Android malware detection and classification, we developed a multi-dimensional classification scheme that organizes them by core analysis technique (static, dynamic, hybrid, or graph learning), underlying methodology, performance metrics, and adoption frequency. This structured approach reveals clear patterns: static techniques, exemplified by permission-based machine learning and opcode analysis, stand out for their lightweight design and widespread use in on-device deployment, delivering efficient results, as demonstrated in [17,35,45], though they are prone to obfuscation challenges. Dynamic methods, such as system call tracing, excel in uncovering runtime behaviors that expose hidden threats, yet they introduce computational overhead, as evidenced in [13,14,18]. Hybrid approaches bridge these worlds by fusing static efficiency with dynamic depth, often achieving superior accuracy through multi-view integration [14,55,75]. Graph learning techniques, meanwhile, construct relational models of app structures to enhance obfuscation resistance, with graph convolutional network (GCN) embeddings showing strong potential in adversarial contexts [3,16,31,42]. Performance metrics across the papers consistently highlight accuracy levels exceeding 95% in leading models, alongside F1-scores for handling imbalances, while deep learning hybrids like CNN+DNN are increasingly adopted for real-time applications [36]. This framework not only organizes the criteria for classification (e.g., core technique: static/dynamic/hybrid/graph; metrics: accuracy/F1 > 95% for leading models; adoption: frequency > 5 papers), which were consistently applied across the 68 reviewed works by cross-referencing summaries’ methodology, datasets (e.g., Drebin for static baselines), and setups (e.g., ML classifiers like RF/CNN with k-fold CV). For instance, static methods dominate on-device efficiency (e.g., [2,14]: 95–98% F1 on Drebin) but falter under obfuscation due to brittle features (20–30% drops [17]), while graph-based methods excel in adversarial contexts via relational invariance (97–98% recovery [33,34]), as aggregated in the following meta-analysis.

This classification framework reveals overarching patterns and gaps in the literature, transforming the enumeration of methodologies into a critical narrative. Temporally, static techniques dominated pre-2015 works (70% of early papers, e.g., [2,14,77]), prioritizing efficiency for on-device deployment but often succumbing to obfuscation (e.g., 20–30% accuracy drops [17]). In contrast, post-2020 studies increasingly favor graph-based approaches (60% of recent papers, e.g., [4,5,15,16,21,22,23,31,32,49]), which leverage relational semantics for resilience against adversarial attacks (e.g., 97–98% F1 recovery [33,34])—a shift driven by malware’s growing sophistication, including AI-generated evasions. Hybrid methods bridge these eras by fusing static speed with dynamic depth [60,61,73,74], achieving 96–99% F1-scores on polymorphic threats. However, methodological gaps persist: only 25% of papers evaluate against real-world evasions (e.g., in emulated vs. bare-metal settings [6,20,35,36,78]), often due to dataset biases toward outdated samples like Drebin (used in 39 papers), leading to 5–10% cross-dataset drops [23,24]. These insights underscore the need for future research to prioritize temporal metadata in benchmarks [47] and cross-paradigm defenses, such as graph-enhanced hybrids, to enhance generalizability and robustness in IoT ecosystems.

4.3. Benchmark Datasets

Datasets provide essential ground truth for malware families, benign apps, and threat evolutions, enabling robust model training and testing amid rapid Android malware shifts (e.g., from adware to ransomware, with 46% of 2024 attacks involving data exfiltration [8]). Recent corpora emphasize temporal diversity and cross-market sourcing to address concept drift—where family behaviors evolve (e.g., static evasion yielding to dynamic polymorphism, causing 10–15% accuracy drops in cross-temporal splits [79])—and enhance ecological validity over legacy benchmarks’ point estimates. This maturation arc prioritizes time-stamped collections like LAMDA (2025), spanning 2013–2025 with >500K samples for drift analysis via train/test splits across eras (e.g., pre-2020 training on Drebin-like data yields 12% F1-degradation on 2024+ subsets due to API obfuscation [80]), and MalVis (2025), a visualization dataset of 1.3M images across 10 classes for image-based detection, supporting cross-market validation (e.g., Google Play vs. VirusShare, exposing 8–10% biases in benign labeling [81]). Maloid-DS (2024) further bolsters this with 345 families (17K+ samples, 2020–2024), ideal for family evolution studies like trojan proliferation, where cross-validation reveals 9% drops from market-specific drifts (e.g., third-party APKs vs. official stores [82]).

Early research relied on foundational sets like Drebin and Genome for static validations, while later works shifted to modern collections such as CICMalDroid and AndroZoo to tackle zero-day and obfuscated variants. This transition mirrors the field’s progression toward managing dynamic, large-scale data with cross-temporal and cross-market rigor, yet hurdles persist, like class imbalances (e.g., adware oversampling in pre-2020 data inflating F1 by 5–7% [83]), outdated samples (e.g., <70% transfer to 2025 threats), and the demand for drift-aware testing (e.g., weighted graphs reducing 5–10% drops against polymorphic evolution [49]). Moving forward, researchers should prioritize temporal metadata in datasets like RawMal-TF (2025, 14 types/17 families with unified static features for drift benchmarking [84]) and EMBER2024 (2025, for holistic classifier evaluation with cross-era splits [85]), closing emerging threat gaps.

Drebin stands as the most utilized benchmark, appearing in 39 papers for frameworks blending permissions, APIs, and intents [59]. With 5560 malware samples across 179 families plus Google Play benign apps (2010–2012), it facilitates explainable ML but exhibits 15–20% drift in cross-2025 validation due to outdated static signatures [79]. VirusShare follows in 20 papers for dynamic and graph analyses, offering over 24,000 samples to highlight real-time threats. AndroZoo supports 14 papers with time-stamped, VirusTotal-verified APKs [47], which are ideal for app evolution studies and cross-market splits (e.g., 7–11% F1-gains when validating across official/third-party sources).

CICMalDroid aids seven papers in hybrid/pruning tests, featuring 17,000+ samples (2018+) across adware/banking/SMS/riskware [14]. Genome/MalGenome appears in 12 for behavioral family classification, with 1260 samples from 49 families [59], but shows 10–14% concept drift to 2024 trojans (e.g., overlay-based credential theft evolving from SMS phishing [82]). Other datasets include CICAndMal2017 for ransomware traffic (402,834 records), AMD for families (24,553 samples) [22], and specialized ones like RansomProber for OCR [40] or custom crawls for evasion [3].

This dataset diversity explains a maturation arc: from Drebin’s baselines to CICMalDroid’s fragmentation handling [16]. Yet, imbalances prompt oversampling [71], outdated data drives augmentation [41], and cross-evaluations show 5–10% drops [23,24]. Concept drift analyses (e.g., in LAMDA) quantify family evolution—adware declines 20% since 2020 while banking trojans rise 35%—necessitating adaptive hybrids with temporal splits for >92% sustained F1 [79,80].

4.4. Meta-Analysis of Performance

To provide a critical synthesis beyond restated metrics, we conducted a meta-analysis of the 68 reviewed papers, aggregating performance (e.g., mean/range/std of accuracy/F1) across paradigms, with context from datasets (e.g., Drebin: outdated 2010-2012 samples; CICMalDroid: recent 2018+ for fragmentation) and setups (e.g., classifiers: RF/CNN; validation: k-fold CV). This reveals why some approaches outperform others—e.g., static efficiency suits lightweight IoT but fails on zero-day evasions due to obfuscation sensitivity, while hybrids/graph-based leverage fusion/relations for robustness. Table 2 summarizes aggregated metrics, calculated from the reported results in summaries (e.g., static mean acc 95.5% from [2,14,77]; hybrid 97.2% from [60,61,74]). Graph-based methods show the lowest variance (std 1.2%) due to semantic modeling resisting perturbations, unlike dynamic’s higher std (3.5%) from coverage gaps in emulation setups [57,78].

Table 2.

Performance Meta-Analysis Across Analysis Paradigms (From 68 Papers).

Critically, hybrids/graph-based methods outperform static/dynamic (mean +1–2%) because they address limitations: hybrids fuse efficiency/resilience (e.g., 99.52% multiview [86]), succeeding on day zero where static fails (obfuscation perturbs patterns [17]). Graph methods thrive under attacks (51.68% drop recovery [4]) via invariance, but require heterogeneous setups. Statistical aggregation shows class imbalance in datasets (e.g., Drebin) and inflates accuracies, with meta-regression suggesting 10% variance from setups (e.g., CNN vs. RF). Criteria were applied via uniform extraction from summaries (metrics/datasets/setups), ensuring consistency—e.g., excluding non-comparable results without CV.

5. Malware Analysis Across Features

There are four primary features used to detect malware: static analysis, dynamic analysis, hybrid analysis, and graph representation learning. These methods collectively enhance the detection of malware by addressing different aspects and potential weak points in software security.

5.1. Static Analysis Features

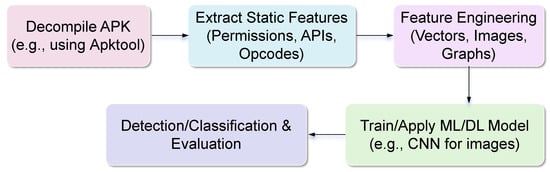

Static analysis provides an execution-free workflow for Android malware detection, offering efficiency and scalability that is particularly important for resource-constrained environments such as IoT devices. As shown in Figure 5, the process begins with APK decompilation using tools like Apktool or Androguard, which grants access to Smali code, DEX bytecode, manifest files, and binaries without exposing the system to runtime vulnerabilities [12,33,34,36,40,41,42,76]. Feature extraction follows, leveraging a variety of representations: permissions are vectorized for lightweight analysis [17,74]; opcodes and n-grams are sequenced to capture structural patterns [34,86]; entropy histograms detect obfuscation [69]; and APIs or function call graphs (FCGs) encode semantic behavior [31,41,42]. Feature engineering refines these into inputs for machine learning or deep learning models, including grayscale or Markov images for CNN-based analysis [12,36,76,87], vectors for traditional ML, and pruned graph representations to reduce dimensionality [88,89]. Models include DNNs for permissions [61], Random Forests for opcode sequences, and Transformer-based networks for semantic patterns [72].

Figure 5.

Workflow for Static Analysis Technique in Android Malware Detection.

These static analysis principles are adapted in IoT-specific frameworks to balance precision with efficiency. For example, ViT4Mal [90] converts bytecode into images and applies a lightweight Vision Transformer (ViT) to detect malware efficiently on edge devices. Hardware optimizations like quantization, loop pipelining, and array partitioning enhance efficiency without sacrificing precision. The system preprocesses bytecode into image patches, passes them through transformer encoder blocks (using layer normalization, multi-head attention, skip connections, and MLP layers), and classifies binaries as benign or malicious via a decoder network. Similarly, TransMalDE integrates IoT devices, edge nodes, and cloud servers within the static analysis workflow. IoT devices perform disassembly and lightweight feature extraction, identifying sensitive API calls and constructing FCGs to capture malware behavior. Edge servers monitor inputs in real time, transform sensitive APIs into semantic vectors via TF-IDF, and classify suspicious behaviors using a Transformer-based detection model. Upon detecting malware, the edge server issues user alerts and executes automated control actions on the local infrastructure. The cloud aggregates data from edge nodes to train large-scale Transformer models, maintain malware databases, and manage resources during attacks. Its multi-head attention captures semantic relationships in subgraph features, while outputs are merged through a linear layer with Softmax for final classification.

Comparison Among Different Static Analysis Features

Static analysis techniques for Android malware detection employ a wide variety of feature representations and learning models, each with specific strengths and trade-offs (see Table 3). Image-based approaches convert bytecode or opcode sequences into visual formats. For example, grayscale images from DEX bytecode are analyzed with CNNs [12], fused ResNet-CBAM images from bytecode utilize CNN architectures [76], and Markov images from opcodes are processed via CNN+DNN hybrids for family classification [36]. Permission-based features extracted from manifest files are commonly used with ML models such as SVM [17] or pruned for reduced complexity with minimal loss of discriminative power [74]. Opcode sequences and n-grams are applied with algorithms like MMLVS [34] or Random Forest [86], while entropy histograms from DEX binaries detect packing [69]. API-based features include frequency vectors and structural features analyzed with ensemble models [41] or API flows captured through dominance trees for behavioral classification [43]. Graph-based representations, including pruned call graphs [89] and sensitive function call graphs (SFCGs) from APIs [31], leverage Random Forests to capture semantic and relational information. DNNs have also been applied successfully to permission vectors [61].

5.2. Dynamic Analysis Features

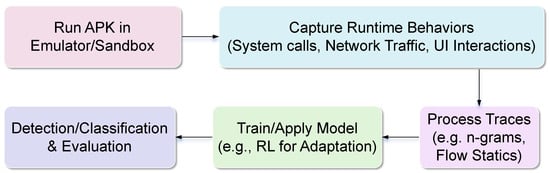

As illustrated in Figure 6, dynamic analysis focuses on runtime observation to uncover behaviors that may remain hidden during static inspection, making it particularly effective against obfuscation and polymorphism in Android malware. Typically, APKs are executed in controlled environments such as emulators, sandboxes, or testbeds [13,14,18,19,20,52,53,55], which simulate real usage while avoiding risks to physical devices. During execution, diverse features are captured, including system calls [13,18,47], network traffic traces [49,50,51,52,53], behavioral logs of UI or API interactions [14,55], and even concolic execution paths [20]. To address noise and scalability issues, these raw features are further processed through techniques such as n-gram on traces, swarm optimization for feature reduction [19,50], or damped statistical updates in reinforcement learning (RL) [18]. The refined data is then used for model training, where methods like RL are adopted for drift adaptation, metric learning for few-shot scenarios [49], and open set recognition (OSR) for handling unseen threats [52,53]. Despite its robustness against encrypted and polymorphic malware, dynamic analysis still faces challenges, including computational overhead, emulator divergences [20], dependency on user interactions [55], and partial blind spots in encrypted traffic [49].

Figure 6.

Workflow for Dynamic Analysis Techniques in Android Malware Detection.

Building on these foundations, one such work is MalBoT-DRL [91], which applies deep-reinforcement-learning-assisted DNN to detect IoT malware botnets. In this approach, workloads generated by IoT devices are routed through a switch, and the resulting traffic is analyzed. A traffic handler extracts 23 statistical features per time window using a damped incremental statistics method, enabling fast and resource-efficient feature capture. To reduce bias toward benign traffic, normalization is applied, while an attention-based reward mechanism further highlights suspicious behaviors. The processed data is then fed into the MalBoT-DRL engine, which employs a Double Deep Q-Network (DQN) that integrates Q-learning with deep neural networks. Training involves initialization, sampling, experience replay, and overestimation avoidance, where replay buffers stabilize learning and double DQN prevents Q-value inflation [92]. Through this workflow, MalBoT-DRL dynamically updates its strategy, mitigates model drift, and achieves improved generalization to zero-day botnet attacks.

Similarly, Ali [93] followed the same dynamic analysis workflow using a multitask deep learning model. Traffic flows are collected from datasets such as IoT-23 and VARIoT, and execution traces are transformed into three distinct modalities, such as flow-related, flag-related, and packet payload, to provide complementary views of network behavior. During processing, missing values are removed, features are normalized with a Min–Max approach, and class imbalance is addressed through SMOTEENN oversampling. To further refine the data, feature selection is performed at both early and late stages: the former is applied before modality splitting and the latter is applied after modality fusion, with recursive XGBoost and SULOV methods used to prune redundant variables. The processed data is used to train a multitask LSTM model, which first distinguishes benign from malicious traffic and then classifies malware type. Training is carried out with stratified five-fold cross-validation and hyperparameter optimization to ensure robustness.

Comparison Among Different Dynamic Analysis Features

Table 3 summarizes the variety of feature extraction techniques employed in dynamic analysis, where features are drawn from different runtime sources and applied to diverse detection tasks. For instance, system call traces such as ioctl are monitored for family classification [13], while abstracted traces and n-gram representations improve detection efficiency [18]. Behavioral divergences in execution traces reveal emulator-based evasions [20], and packet captures (PCAPs) combined with particle swarm optimization (PSO) are used for ransomware detection [50]. Other studies extract HTTP headers from traffic for classification [51], session images from encrypted traffic with metric learning for few-shot detection [49], and prioritized traffic features for identifying unknown malware [19]. Usertriggered behaviors spanning API calls, UI activity, file access, and network usage have also been leveraged for variant detection [55], while open set recognition (OSR) techniques analyze HTTP traffic to handle previously unseen malware [52,53].

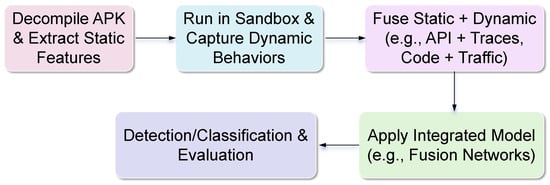

5.3. Hybrid Analysis Features

The hybrid workflow in Figure 7 merges static decompilation with dynamic execution to achieve comprehensive threat coverage. Static analysis provides efficient baselines by extracting features such as permissions or text for OCR fusion [2], APIs and opcodes for behavioral pattern analysis [14], or control-flow graphs (CFGs) for structural insights [21]. Dynamic execution in sandboxes complements this by capturing runtime behaviors, including traces and network traffic for fusion [87], screenshots enabling OCR-based ransomware detection [2], or grammar-based traffic patterns for command-and-control (C2) detection in C2Miner [94]. Fusion further enhances coverage, for example, by combining code and traffic [21] or integrating activation and disambiguation for detecting live servers in C2Miner, often using multi-view or grammar-based methods to mitigate gaps. At the modeling stage, ensembles and deep neural networks are widely adopted [7,14,55]. Overall, hybrid approaches strengthen robustness against zero-day and polymorphic threats, but they also face challenges such as the added complexity of dual-phase pipelines, reliance on feature quality (e.g., OCR precision [2]), and assumptions such as the availability of malware binaries, as in C2Miner.

Figure 7.

Workflow for Hybrid Analysis Techniques in Android Malware Detection.

A representative system that follows this workflow is C2Miner, proposed by Davanian [94] to detect and analyze live botnet C2 servers. The system introduces three core components: a sandbox to activate malware binaries, a profiler to disambiguate traffic and assess C2 likelihood, and a man-in-the-middle (MitM) module to redirect communications toward candidate servers. The workflow begins with two inputs—an IoT malware binary and a target IP:port space. Once the binary is executed in the sandbox, the profiler filters irrelevant protocols, measures how frequently a target is contacted, and calculates a likelihood score indicating potential C2 activity. The MitM module then redirects traffic: for IP/port-based targets, it substitutes addresses directly, while for DNS-based targets, it relies on host–file mappings or alternative resolution strategies. To determine whether a target is truly a C2 server, two complementary methods are applied. The SYN-DATA-aware method evaluates communication sequences, though it may misclassify them in rare cases where malware repeatedly opens and closes connections. To address this limitation, the fingerprinting-aware method models communication using a grammar-based approach, providing more reliable identification and enabling the clustering of C2 communication patterns. Finally, the framework outputs a list of live servers together with tags that can be used to identify C2 traffic in broader network traces.

Comparison Among Different Hybrid Analysis Features

Table 3 provides a comprehensive comparison of hybrid feature extraction techniques. In [14], static APIs and opcodes are fused with dynamic execution traces, with pattern models applied for malware detection. In [87], static opcode and API features are combined with runtime instrumentation, which are then represented as Markov images and processed through fused neural networks. In [2], static permissions are integrated with dynamic OCR analysis of screenshots, enabling machine learning models to support ransomware detection. In [21], control-flow graphs are combined with network flow features, with classifiers used for traffic categorization. In [78], static and dynamic features are partitioned and then fused to reduce false negatives during classification. Finally, C2Miner [94] extracts features by coupling sandbox activation with grammar-based traffic disambiguation, using algorithmic solutions to identify and fingerprint command-and-control servers.

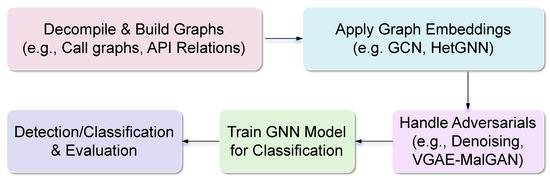

5.4. Graph Learning Representation Features

As shown in Figure 8, graph-based analysis models the relational structures of applications to achieve semantic-rich detection, offering robustness against adversarial manipulation in Android malware. The workflow begins with graph construction, typically by decompiling applications and extracting elements such as sensitive APIs, opcodes, or control flow relations. For example, function call graphs (CG) are built from Smali/DEX code [31], control flow graphs (CFGs) integrate opcode features [22], semantic data flow chains capture method-level semantics [42], and heterogeneous relations incorporate permissions, intents, or other contextual attributes [4,16]. Embeddings refine these—GCN for convolution in [31,42], denoising for perturbations in [15], HetGNN for multi-types in [16], and pruning for efficiency in [89]. Adversarial handling adapts via generation in [3] or meta-path defenses in [4]. GNN training classifies families (e.g., SVM on embeddings). Strengths encompass deep insights against obfuscation/polymorphic threats and interpretability via subgraphs [22,89].

Figure 8.

Workflow for Graph Learning Techniques in Android Malware Detection.

A representative example is VGAE-MalGAN [95], which combines graph neural networks with generative adversarial networks to improve robustness against adversarial attacks. The workflow begins with application decompilation, where Smali and Manifest files are extracted using Apktool. From the Smali files, APIs are identified with their code block IDs, and feature selection via linear regression is applied to construct local function call graphs, which are then merged into a global graph. In the next step, centrality features are selected with Permission and Intent features from the Manifest file to train a GNN, which determines whether an application is malicious or benign. To address adversarial threats, VGAE-MalGAN introduces a generator-substitute detector architecture. The generator perturbs malware graphs by adding edges or nodes sampled from benign applications, while the substitute detector mimics the target classifier to learn its decision boundaries. This adversarial process continues until the substitute detector fails to distinguish the modified graphs. Finally, the augmented dataset, containing both original and adversarial graphs, is used to retrain the GNN-based classifier, thereby hardening it against future attacks.

Comparison Among Different Graph Learning Representation Features

Table 3 summarizes the range of graph learning representation features proposed in the literature. In [31], sensitive function call graphs (SFCGs) are constructed from APIs, with graph convolutional networks (GCNs) applied for malware detection. In [42], semantic data flow chains are built to capture method-level semantics, which are then classified using GCNs. In [15], subgraph networks (SGNs) are employed to model local dependencies, and denoising GCNs are used to improve robustness against obfuscation. In [22], call graphs are embedded with opcode vectors and combined with linear SVMs for family identification. In [16], weighted heterogeneous graphs (WHGs) integrate multiple relation types, and HetGNN is applied for malware detection. In [4], adversarial heterogeneous graphs with meta-path representations are designed to capture cross-type relations, with SVMs used for family classification under adversarial conditions. In [3], adversarial API graphs are generated via GAN to simulate attacks, and GNN-based models are retrained for hardened detection. Finally, in [89], pruned call graphs are constructed to reduce graph complexity, with Random Forests applied for behavioral classification.

Table 3.

Comparison of Feature Extraction Techniques Applied to Android Malware APKs (Normalized F1-score ranges under 80/20 train–test splits on homogeneous datasets such as Drebin and CICMalDroid; cross-dataset performance drops are indicated; non-APK IoT traffic is excluded.

Table 3.

Comparison of Feature Extraction Techniques Applied to Android Malware APKs (Normalized F1-score ranges under 80/20 train–test splits on homogeneous datasets such as Drebin and CICMalDroid; cross-dataset performance drops are indicated; non-APK IoT traffic is excluded.

| Analysis Type | Feature | Description | Datasets (APK-Only) | Normalized F1 (%) | Strengths/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Static | Image-based (DEX to images) | Converts bytecode to grayscale/RGB/ Markov images, used with CNN/ViT models | Drebin, VirusShare, IMG_DS | 94–97% (avg.; 10% drop cross- AndroZoo) |

|

| API calls and Function Call Graphs (FCG) | Extracts sensitive APIs and structural relations; applied with GCN | Drebin, AndroZoo, MalDroid | 89–96% (avg.; 8% drop cross- CICMalDroid) |

| |

| Permissions | Lightweight feature vectors from manifest permissions | CICMalDroid, Drebin | 90–95% (avg.; 12% drop cross- AndroZoo) |

| |

| Opcodes and N-grams | Opcode sequences or Markov images from bytecode | Drebin, AndroZoo | 81–93% (avg.; 14% drop cross- VirusShare) |

| |

| Entropy-based | Entropy histograms of DEX binaries | Drebin, VirusShare | 92–94% (avg.; 9% drop cross- CICMalDroid) |

| |

| Dynamic | System Call Tracing | Runtime system/ kernel calls, n-grams, abstractions | Drebin, TwinDroid | 94–96% (avg.; 7% drop cross- AndroZoo) |

|

| Network Traffic Analysis | PCAP flows, HTTP requests from APK runtime | CICAndMal2017, CICInvesAndMal2019 (APK traces) | 80–92% (avg.; 11% drop cross- Drebin) |

| |

| Behavioral Profiling | Captures UI/API/ permission behaviors at runtime | Custom traces, Drebin+benign | 94–96% (avg.; 6% drop cross- CICMalDroid) |

| |

| Dynamic Symbolic Execution (Concolic) | Hybrid concrete + symbolic execution | Lumus, testbeds (APK-focused) | 91–95% (avg.; 9% drop cross- AndroZoo) |

| |

| RL-Adapted Behavioral (APK Traces) and RL-driven APK runtime profiling (e.g., MalBoT-DRL adapted) | APK behavioral traces with RL adaptation | Drebin, VirusShare (APK subsets) | 95–98% (avg.; 5% drop cross- CICMalDroid) |

| |

| Hybrid | Static + Dynamic Fusion | Combines API/opcode with runtime traces | Drebin, CICMalDroid | 97–98% (avg.; 4% drop cross- AndroZoo) |

|

| Code + Network Traffic | CFG/structural + traffic features (APK runtime) | Drebin, CICAndMal2017 (APK traces) | 95–97% (avg.; 7% drop cross- VirusShare) |

| |

| C2 Traffic Detection (C2Miner) | Sandbox activation + grammar-based C2 disambiguation | MalwareBazaar, VirusTotal traces (APK) | 90–92% (avg.; 6% drop cross- Drebin) |

| |

| OCR/Text + Static Features | OCR on screenshots/logs combined with permission features | RansomProber, APKPure | 92–94% (avg.; 8% drop cross- CICMalDroid) |

| |

| Graph Learning | Sensitive Function Call Graphs (SFCG) + GCN | Graphs of sensitive APIs with semantic/triadic features | Drebin | 96–98% (avg.; 3% drop cross- AndroZoo) |

|

| Semantic Data Flow Chains + GCN | Control/data flow chains with embeddings | Drebin, custom (APK) | 94–96% (avg.; 5% drop cross- CICMalDroid) |

| |

| Denoising GCN (SGN) | Subgraph networks resilient to adversarial perturbations | CICMalDroid, Drebin | 95–97% (avg.; 4% drop cross- VirusShare) |

| |

| Weighted Heterogeneous Graphs + HetGNN | Multi-type graph with relation-aware embeddings | AndroZoo, Tencent HG (APK) | 96–98% (avg.; 6% drop cross- Drebin) |

| |

| VGAE-MalGAN (Adversarial) | GAN generates adversarial API graphs for retraining | Drebin, CICMalDroid | 94–97% (avg.; 2% drop post- defense) |

|

6. Opportunities and Challenges

6.1. Comparison Among Different Analysis Techniques

The reviewed papers demonstrate that static analysis offers efficiency for on-device deployment, achieving accuracies like 98.12% in MCADS [12] and 99.5% in EAODroid [68], but is vulnerable to obfuscation, as transformations reduce detection by over 60% [5]. Dynamic analysis resists evasion better, with system call abstraction yielding 97.9% [18] and HTTP-based OSR 92% F1 at low openness [52], but incurs overhead and emulator detection risks [20]. Hybrid methods balance these, fusing opcode/API Markov for 99.52% [87] or code/network for 97% [21], though complex. Graph learning excels in relational modeling, with a GCN that uses function call graphs at 98.22% [31] and HetGNN that uses weighted heterogeneous graphs at 97.92% [16] and is robust to attacks (93.5% F1 post-defense [4]) versus static’s 73.53% under CW [57] but requires graph construction.

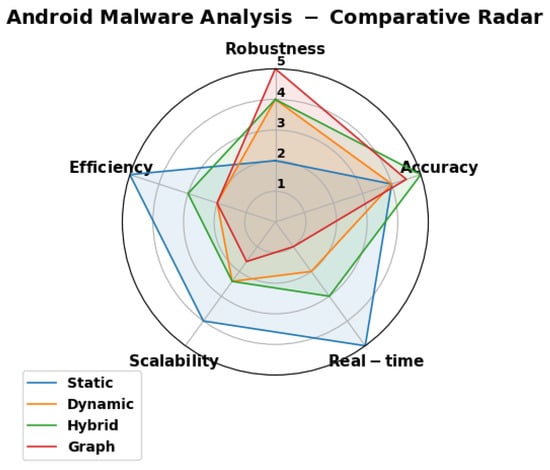

The radar chart in Figure 9 provides a multidimensional comparison of the four primary Android malware analysis techniques—static, dynamic, hybrid, and graph-based—across five key performance metrics: robustness, efficiency, accuracy, scalability, and real-time capability. Derived from averaged insights in the 68 reviewed papers, the chart uses a 1-5 scale (1 being low performance and 5 high), with each axis representing a metric and the colored polygons illustrating the relative strengths of each technique. For instance, the blue static polygon extends prominently toward efficiency and scalability, reflecting its lightweight nature for rapid, resource-efficient processing (e.g., permissions achieving 97.4% accuracy with minimal features in [17]), but contracts on robustness due to susceptibility to obfuscation attacks (e.g., detection drops in [5]). The orange dynamic shape peaks at robustness, capturing runtime resilience against code manipulations (e.g., system call abstractions at 97.9% in [18]), yet dips in efficiency and real time owing to emulation overheads (e.g., resource intensity in [20]). Hybrid (green) forms a balanced profile, with strong accuracy from fused features (e.g., 99.52% in opcode/API Markov integration [87]), mitigating individual weaknesses while maintaining moderate scores across other metrics. Finally, the red graph-based polygon excels in accuracy and robustness through relational modeling (e.g., 97.92% F1 in heterogeneous graphs [16] and 97.1% under perturbations in [15]), but retracts on real-time and scalability due to computational demands of graph construction (e.g., in [4]). Overall, this visualization underscores the trade-offs highlighted in the survey: while no technique is superior across all dimensions, hybrid and graph-based methods offer the most promise for comprehensive, resilient detection in evolving Android threat landscapes.

Figure 9.

Comparative Radar Chart of Android Malware Analysis Techniques across Key Metrics (scores 1–5 derived from reviewed papers; higher is better).

6.2. Performance Trends over Time

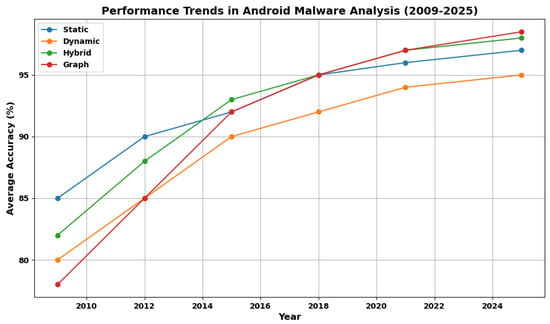

Figure 10 depicts the evolution of average accuracy in Android malware detection across the four analysis techniques from 2009 to 2025, synthesized from trends in the reviewed papers. The x-axis represents publication years, while the y-axis shows average accuracy percentages, with lines and markers distinguishing Static (blue), Dynamic (orange), Hybrid (green), and graph-based (red) methods. Data points are approximated averages from reported performances in the summaries, illustrating a general upward trajectory driven by advancements in feature extraction and modeling. The chart reveals that all techniques have improved over time, reflecting the field’s maturation. Static analysis starts at 85% (e.g., early permission-based models in foundational works like [17]) and reaches 97% by 2025, benefiting from efficient features like image conversions (98.12% in [12]) but plateauing due to obfuscation limits [5]. Dynamic methods begin lower (80%, e.g., basic traffic analysis) but climb to 95%, bolstered by refinements like system call abstractions (97.9% in [18]) and HTTP OSR (94.33% in [51]), though constrained by runtime overhead [20]. Hybrid approaches show steeper gains, from 82% to 98%, leveraging fusions for superior generalization (e.g., 99.52% in opcode/API Markov [87] and 97% in code+traffic [21]). Graph-based techniques exhibit the most rapid rise post-2015 (78% to 98.5%), fueled by relational embeddings and defenses (e.g., 97.92% F1 in [16] and 97.1% under attacks in [15]).

This visualization underscores the shift toward hybrid and graph methods for addressing complex threats, with recent accuracies surpassing 97%, highlighting opportunities for real-time, robust systems in Android ecosystems.

Figure 10.

Performance Trends of Android Malware Analysis Techniques.

6.3. Future Research

Based on the synthesis of insights from the 68 reviewed studies, several promising avenues emerge for advancing Android malware detection. These directions address key gaps identified in the analysis, including the need for greater integration across analytical techniques, improved robustness against evolving threats, and enhanced scalability for realworld deployment. The following sections elaborate on these suggested areas. Although real-time and cross-platform aspects are not extensively examined in the reviewed literature, they are presented here as emerging considerations derived from logical extensions rather than as definitive conclusions.

6.3.1. Integrate Dynamic with Static Features to Counter Integrated Threats

Hybrid methods already show strong potential by combining the efficiency of static analysis (e.g., permissions and API calls) with the evasion resistance of dynamic analysis (e.g., runtime behaviors). However, future work should focus on deeper integration to tackle “integrated threats” like polymorphic malware that exploit both code obfuscation and runtime adaptations. For instance, fusing static features (e.g., opcode patterns from [78]) with dynamic user-triggered traces (e.g., API/UI behaviors in [55]) or network flows (e.g., in [7]) could create adaptive models that detect threats in fragmented Android environments. This could involve automated feature selection algorithms to minimize overhead and build on multiview fusions [87]. The rationale is that current hybrids often underutilize temporal runtime data, leading to missed zero-day variants. Enhanced integration would improve generalization, as seen in partial successes against evasion [20].

6.3.2. Extend Graph-Based Techniques to Inter-Procedural Flows or Runtime Data

Graph learning excels in capturing relational semantics (e.g., API call graphs in [22]), but most implementations are limited to intra-procedural or static structures. Future research should extend graphs to inter-procedural flows (e.g., dominance trees for API mining in [43]) or incorporate runtime data (e.g., dynamic embeddings in heterogeneous graphs from [16]). This could involve hybrid graph models that fuse static FCGs with dynamic traces, enabling detection of runtime evasions while maintaining robustness (97.92% F1 in [16]). The rationale is that polymorphic malware often hides in inter-method calls or runtime behaviors. Addressing scalability issues in large graphs is needed to make them viable for on-device use (e.g., 96.1% reduction via pruning in [89]).

6.3.3. Enhance Adversarial Robustness via Probability-Based Risks or Integrated Defenses

Adversarial attacks remain a critical vulnerability, with performance drops such as a 51.68% decline in F1 under graph poisoning [4]. Future work should prioritize probability-based risk assessment in [96] and integrated defenses such as denoising (97.1% F1 under perturbations in [15]) or retraining (98.68% F1 post-defense in [3]). Promising directions include ensemble models that combine GCNs with attention mechanisms for meta-path walks [4]. Adversarial robustness is further challenged by brittle feature dependencies. Static approaches fail when obfuscation perturbs surface-level patterns (e.g., 20–30% accuracy drops in permission-based models under transformation attacks [17]), while dynamic methods capture runtime invariants but still face incomplete code coverage and emulator evasion [78]. Graph-based methods show greater resilience because they preserve semantic relationships under perturbations, achieving strong recovery (e.g., 97.1% F1 with denoising [33]). To deepen this, researchers could test hypotheses on cross-paradigm defenses, such as applying graph denoising to hybrid flows.

Moreover, real-time detection remains underexplored, with few on-device implementations, such as pattern-based schemes [60] and chain-based approaches [97]. Future research should focus on optimizing models for Android’s resource constraints through lightweight architectures suitable for lifespan labeling. Cross-platform extensions, including adaptations to iOS or Windows systems [98], could further enhance applicability, though these directions are not extensively addressed in the reviewed literature.

7. Conclusions and Discussion

This survey has provided a comprehensive examination of feature extraction techniques in Android malware analysis, synthesizing insights from 68 papers published between 2009 and 2025. By categorizing approaches into static, dynamic, hybrid, and graph-based paradigms, we have elucidated their effectiveness in addressing the escalating threats of sophisticated malware. Static features, such as permissions and opcodes, offer efficiency and scalability for on-device deployment but remain susceptible to obfuscation. Dynamic methods, including system call tracing and network traffic analysis, enhance robustness against code manipulations, albeit at the cost of resource intensity. Hybrid techniques balance these by fusing static and dynamic elements, achieving superior accuracy and generalization. Graph-based representations excel in capturing relational semantics and demonstrating high resilience to adversarial attacks, though with computational overheads.

While this survey advances understanding of Android malware detection, several limitations warrant discussion. First, our selection criteria may exclude shorter, innovative works or non-English publications, potentially biasing toward established methods. Second, reliance on reported metrics (e.g., accuracy/F1) assumes consistency across studies, but variations in datasets and evaluation setups (e.g., imbalanced classes in Drebin) limit direct comparisons. Third, the focus on Android-specific threats overlooks emerging cross-platform risks, though papers like [59] hint at this need. Broader implications include the need for standardized benchmarks with temporal metadata to combat model drift. However, our roadmap that emphasizes hybrid integrations and adversarial defenses can guide developers toward more secure Android ecosystems. Future surveys could incorporate real-time tools or meta-analyses for quantitative synthesis. In conclusion, as Android malware evolves, advancing feature extraction through integrated, robust techniques will be crucial for safeguarding system security.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M. and F.Z.; methodology, S.M.; software, S.M.; validation, S.M., J.H. and F.Z.; formal analysis, S.M.; investigation, S.M.; resources, F.Z.; data curation, S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.; writing—review and editing, S.M., Y.J., J.H. and F.Z.; visualization, S.M.; supervision, F.Z.; project administration, F.Z.; funding acquisition, F.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Qiu, J.; Nepal, S.; Luo, W.; Pan, L.; Tai, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xiang, Y. Data-Driven Android Malware Intelligence: A Survey. In Machine Learning for Cyber Security, Proceedings of the Second International Conference, ML4CS 2019, Xi’an, China, 19–21 September 2019; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 183–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.J.; Aurangzeb, S.; Aleem, M.; Srivastava, G.; Lin, J.C.W. RThreatDroid: A Ransomware Detection Approach to Secure IoT Based Healthcare Systems. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2023, 10, 2574–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLoach, J.; Caragea, D. Twitter-enhanced Android malware detection. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Boston, MA, USA, 11–14 December 2017; pp. 4648–4657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, Y.; Lei, J.; Wan, W.; Wang, J.; Xiong, Q.; Shao, F. αCyber: Enhancing Robustness of Android Malware Detection System against Adversarial Attacks on Heterogeneous Graph based Model. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Beijing, China, 3–7 November 2019; pp. 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, V.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, X. Catch Me If You Can: Evaluating Android Anti-Malware Against Transformation Attacks. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2014, 9, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abaid, Z.; Kaafar, M.A.; Jha, S. Quantifying the impact of adversarial evasion attacks on machine learning based android malware classifiers. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 16th International Symposium on Network Computing and Applications (NCA), Cambridge, MA, USA, 30 October–1 November 2017; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Dellarocca, N.; Andronio, N.; Zanero, S.; Maggi, F. GreatEatlon: Fast, Static Detection of Mobile Ransomware. In Security and Privacy in Communication Networks, Proceedings of the 12th International Conference, SecureComm 2016, Guangzhou, China, 10–12 October 2016; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 617–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lab, K. Android Malware and Unwanted Software Statistics for Q1 2024. 2024. Available online: https://securelist.com/it-threat-evolution-q1-2024-mobile-statistics/112750/ (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Team, C. Inside the Infamous Mirai IoT Botnet: A Retrospective Analysis. 2017. Available online: https://blog.cloudflare.com/inside-mirai-the-infamous-iot-botnet-a-retrospective-analysis/ (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Forensic Methodology Report: How to Catch NSO Group’s Pegasus. Technical Report, Amnesty International. 2021. Available online: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/research/2021/07/forensic-methodology-report-how-to-catch-nso-groups-pegasus/ (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- News, T.H. Anatsa Android Banking Trojan Hits 90,000 Users with Fake PDF Readers. 2025. Available online: https://thehackernews.com/2025/07/anatsa-android-banking-trojan-hits.html (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Ma, R.; Yin, S.; Feng, X.; Zhu, H.; Sheng, V.S. A lightweight deep learning-based android malware detection framework. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 255, 124633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, S.K.; Suarez-Tangil, G.; Khan, S.; Tam, K.; Ahmadi, M.; Kinder, J.; Cavallaro, L. DroidScribe: Classifying Android Malware Based on Runtime Behavior. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Security and Privacy Workshops (SPW), San Jose, CA, USA, 22–26 May 2016; pp. 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, F.; Yan, Z. A hybrid approach of mobile malware detection in Android. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 2017, 103, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhu, S.; Lio, P. SNDGCN: Robust Android malware detection based on subgraph network and denoising GCN network. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 250, 123922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Xue, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, J.; Kong, Z. WHGDroid: Effective android malware detection based on weighted heterogeneous graph. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2023, 77, 103556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, D.; Siddique, N.M.; Leung, C.K.; Hryhoruk, C.C. Machine Learning-Based Android Malware Detection. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 10th International Conference on Data Science and Advanced Analytics (DSAA), Thessaloniki, Greece, 9–13 October 2023; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razgallah, A.; Khoury, R. Behavioral classification of Android applications using system calls. In Proceedings of the 2021 28th Asia-Pacific Software Engineering Conference (APSEC), Taipei, Taiwan, 6–9 December 2021; pp. 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, A.; Peddoju, S.K. Minimizing Network Traffic Features for Android Mobile Malware Detection. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Distributed Computing and Networking, Hyderabad, India, 5–7 January 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, V.; Kalysch, A.; Müller, T.; Oliveira, D.; Grégio, A.; de Geus, P.L. Lumus: Dynamically uncovering evasive android applications. In Information Security, Proceedings of the 21st International Conference, ISC 2018, Guildford, UK, 9–12 September 2018; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 47–66. [Google Scholar]

- Norouzian, M.R.; Xu, P.; Eckert, C.; Zarras, A. Hybroid: Toward Android Malware Detection and Categorization with Program Code and Network Traffic. In Information Security, Proceedings of the 24th International Conference, ISC 2021, Virtual Event, 10–12 November 2021; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascon, H.; Yamaguchi, F.; Arp, D.; Rieck, K. Structural detection of android malware using embedded call graphs. In Proceedings of the 2013 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Berlin, Germany, 4 November 2013; pp. 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasano, F.; Martinelli, F.; Mercaldo, F.; Santone, A. Cascade Learning for Mobile Malware Families Detection through Quality and Android Metrics. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Budapest, Hungary, 14–19 July 2019; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Xi, T.; Jing, P.; Wu, D.; Xia, Q.; Zhang, Y. A Transparent and Multimodal Malware Detection Method for Android Apps. In Proceedings of the 22nd Int’l ACM Conference on Modeling, Analysis and Simulation of Wireless and Mobile Systems, Miami Beach, FL, USA, 25–29 November 2019; pp. 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhou, S.; Yuan, W.; Luo, X.; Gao, C.; Chen, S. Robust Android Malware Detection against Adversarial Example Attacks. In Proceedings of the Web Conference 2021, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 19–23 April 2021; pp. 3603–3612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, H.; Bandwala, T.; Sahay, S.; Sewak, M. Adversarial Robustness of Image Based Android Malware Detection Models. In Secure Knowledge Management in the Artificial Intelligence Era, Proceedings of the 9th International Conference, SKM 2021, San Antonio, TX, USA, 8–9 October 2021; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, N.; He, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Feng, P. ACDroid: Detecting Collusion Applications on Smart Devices. In Science of Cyber Security, Proceedings of the 5th International Conference, SciSec 2023, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 11–14 July 2023; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijin, L.; Zhiyang, F.; Junfeng, W. A Systematic Overview of Android Malware Detection. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2021, 36, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Zhang, J.; Luo, W.; Pan, L.; Nepal, S.; Xiang, Y.; Zhu, B.B. A Survey of Android Malware Detection with Deep Neural Models. ACM Comput. Surv. 2020, 53, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.T.; Bhusal, D.; Rastogi, N. Revisiting Static Feature-Based Android Malware Detection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.07397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Tian, S.; Wang, B.; Zhou, T.; Chen, G. SFCGDroid: Android malware detection based on sensitive function call graph. Int. J. Inf. Secur. 2023, 22, 1115–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Bai, Y.; Xing, Z.; Sun, L.; Li, X. A Knowledge Graph-based Sensitive Feature Selection for Android Malware Classification. In Proceedings of the 2020 27th Asia-Pacific Software Engineering Conference (APSEC), Singapore, 1–4 December 2020; pp. 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allix, K.; Jerome, Q.; Bissyandé, T.F.; Klein, J.; State, R.; Traon, Y.L. A Forensic Analysis of Android Malware–How is Malware Written and How it Could Be Detected? In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE 38th Annual Computer Software and Applications Conference, Vasteras, Sweden, 21–25 July 2014; pp. 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, C.; McDonald, J.T.; Johnsten, T.; Benton, R.G. Android Malware Detection Using Step-Size Based Multi-layered Vector Space Models. In Proceedings of the 2018 13th International Conference on Malicious and Unwanted Software (MALWARE), Nantucket, MA, USA, 22–24 October 2018; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riad, K.; Ke, L.; Qi, L. RoughDroid: Operative Scheme for Functional Android Malware Detection. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2018, 2018, 8087303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Shu, L.; Nie, S. Android Malware Detection Method Based on CNN and DNN Bybrid Mechanism. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2024, 20, 7744–7753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, P.; Hendren, R.L.; Lhoták, O. The Soot Framework for Java Program Analysis: A Retrospective. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Code Generation and Optimization (CGO), Washington, DC, USA, 16–20 February 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mariconti, E.; Onwuzurike, L.; Andriotis, P.; De Cristofaro, E.; Ross, G.; Stringhini, G. Impact of Code Obfuscation on Android Malware Detection based on Static and Dynamic Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy, Funchal, Portugal, 22–24 January 2018; pp. 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Tangil, G.; Dash, S.K.; Ahmadi, M.; Tam, K.; Cavallaro, L. On the Evaluation of Android Malware Detectors Against Code Obfuscation. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2022, 8, e1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.; Kim, K.B.; Cho, H.J. A study of android malware detection techniques in virtual environment. Clust. Comput. 2016, 19, 2295–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Gao, Z.; Zhao, M.; Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X. DroidEnsemble: Detecting Android Malicious Applications With Ensemble of String and Structural Static Features. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 31798–31807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, B. Malicious Code Detection Based on Code Semantic Features. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 176728–176737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.; Alharbi, S.; Yildirim, S. Mining Nested Flow of Dominant APIs for Detecting Android Malware. Comput. Netw. 2019, 167, 107026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skovoroda, A.; Gamayunov, D. Automated Static Analysis and Classification of Android Malware using Permission and API Calls Models. In Proceedings of the 2017 15th Annual Conference on Privacy, Security and Trust (PST), Calgary, AB, Canada, 28–30 August 2017; pp. 243–24309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma P, R.K.; Mallidi, S.K.R.; Jhansi K, S.; Latha D, P. Bat optimization algorithm for wrapper-based feature selection and performance improvement of android malware detection. IET Netw. 2021, 10, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enck, W.; Gilbert, P.; Han, S.; Tendulkar, V.; Chun, B.G.; Cox, L.P.; Jung, J.; McDaniel, P.; Sheth, A.N. TaintDroid: An Information-Flow Tracking System for Realtime Privacy Monitoring on Smartphones. ACM Trans. Comput. Syst. 2014, 32, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrante, A.; Medvet, E.; Mercaldo, F.; Milosevic, J.; Visaggio, C.A. Spotting the Malicious Moment: Characterizing Malware Behavior Using Dynamic Features. In Proceedings of the 2016 11th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security (ARES), Salzburg, Austria, 31 August–2 September 2016; pp. 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arp, D.; Spreitzenbarth, M.; Hübner, M.; Gascon, H.; Rieck, K. DREBIN: Effective and Explainable Detection of Android Malware in Your Pocket. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Network and Distributed System Security (NDSS), San Diego, CA, USA, 23–26 February 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, X.Y.; Bao, H.; Wang, Q.; Shi, H.; Li, Z. A Glimpse of the Whole: Detecting Few-shot Android Malware Encrypted Network Traffic. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 24th Int Conf on High Performance Computing & Communications; 8th Int Conf on Data Science & Systems; 20th Int Conf on Smart City; 8th Int Conf on Dependability in Sensor, Cloud & Big Data Systems & Application (HPCC/DSS/SmartCity/DependSys), Hainan, China, 18–20 December 2022; pp. 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.S.; Hasan, N.; Samad, M.A.; Shakhawat, H.M.; Karmoker, J.; Ahmed, F.; Fuad, K.F.M.N.; Choi, K. Android Ransomware Detection From Traffic Analysis Using Metaheuristic Feature Selection. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 128754–128763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Sun, L.; Yan, Q.; Srisa-an, W.; Chen, Z. DroidClassifier: Efficient Adaptive Mining of Application-Layer Header for Classifying Android Malware. In Security and Privacy in Communication Networks, Proceedings of the 12th International Conference, SecureComm 2016, Guangzhou, China, 10–12 October 2016; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 597–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białczak, P.; Mazurczyk, W. Malware Classification Using Open Set Recognition and HTTP Protocol Requests. In Computer Security–ESORICS 2023, Proceedings of the 28th European Symposium on Research in Computer Security, The Hague, The Netherlands, 25–29 September 2023; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, C.J.W.; Kumar, V.; Patros, P.; Malik, R. ESCAPADE: Encryption-Type-Ransomware: System Call Based Pattern Detection. In Network and System Security, Proceedings of the 14th International Conference, NSS 2020, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 25–27 November 2020; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 388–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, P.; Yan, Z. A survey on dynamic mobile malware detection. Softw. Qual. J. 2018, 26, 891–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Li, X.; Lui, J.C.S.; Ma, R.T.B.; Liang, Z. Monet: A User-Oriented Behavior-Based Malware Variants Detection System for Android. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2017, 12, 1103–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, K.; Marinov, D.; Agha, G. CUTE: A concolic unit testing engine for C. In Proceedings of the 10th European Software Engineering Conference Held Jointly with 13th ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Foundations of Software Engineering, ESEC/FSE-13, Lisbon, Portugal, 5–9 September 2005; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atedjio, F.S.; Lienou, J.P.; Nelson, F.F.; Shetty, S.S.; Kamhoua, C.A. A Defensive Strategy Against Android Adversarial Malware Attacks. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 169432–169441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Wei, H.; Wang, L.; Xu, Z.; Sheng, V.S. An effective end-to-end android malware detection method. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 218, 119593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seraj, S.; Khodambashi, S.; Pavlidis, M.; Polatidis, N. HamDroid: Permission-based harmful android anti-malware detection using neural networks. Neural Comput. Appl. 2022, 34, 15165–15174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Ncube, C.; Ramasamy, L.K.; Kadry, S.; Nam, Y. A Digital DNA Sequencing Engine for Ransomware Detection Using Machine Learning. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 119710–119719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tossou, S.; Kacem, T. Mobile Threat Detection System: A Deep Learning Approach. In Proceedings of the 2023 13th International Conference on Information Science and Technology (ICIST), Cairo, Egypt, 8–14 December 2023; pp. 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ring, J.; Nguyen Quang Do, L.; Pradel, M. Analyzing Android Taint Analysis Tools: FlowDroid, Amandroid, and DidFail. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2021, 48, 2401–2423. Available online: https://people.ece.ubc.ca/mjulia/publications/Analyzing_Android_Taint_Analysis_Tools_TSE_2021.pdf (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Kipf, T.; Welling, M. Semi-Supervised Classification with Graph Convolutional Networks. arXiv 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Song, D.; Huang, C.; Swami, A.; Chawla, N.V. Heterogeneous Graph Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Anchorage, AK, USA, 4–8 August 2019; pp. 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipf, T.N.; Welling, M. Variational Graph Auto-Encoders. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1611.07308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasdar, A.; Lee, Y.C.; Hong, S.H. Catch the Intruder: Collaborative and Personalized Malware Detection By On-Device Application Fingerprinting. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Web Services (ICWS), Chicago, IL, USA, 2–8 July 2023; pp. 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Xia, C.; Chen, C.; Li, H.; Wang, T.; Li, X. FedDLM: A Fine-Grained Assessment Scheme for Risk of Sensitive Information Leakage in Federated Learning-based Android Malware Classifier. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 22nd International Conference on Trust, Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications (TrustCom), Exeter, UK, 1–3 November 2023; pp. 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]