Abstract

A synergetic computing mechanism is proposed to authenticate the validity of event data in merchandise exchange applications. The events are handled by the proposed synergetic computing system which is composed of edge devices. Asteroid_Node_on_Duty (ANOD) acts like a supernode to take the duty of coordination. The computation performed by nodes in local area can reduce round-trip data propagation delay to distant data centers. Events with different risk levels are processed in parallel through different flows by using Chief chain (CC) and Telstar chain (TC) methods. Low-risk events are computed in edge nodes to form TC, which can be periodically integrated into CC that contains data of high-risk events. New authentication methods are proposed. The difficulty of authentication tasks is adjusted for different scenarios where lower difficulty in low-risk tasks may accelerate the process of validation. Authentication by a certain number of nodes is required so that the system may ensure the consistency of data. Participants in the system may need to register as members. The transaction processing speed on low-risk events may reach 25,000 TPS based on the assumption of certain member classes given that all of ANOD, and Asteroid_Node_of_Backup (ANB), Edge Cloud, and Core Cloud function normally.

1. Introduction

In this paper, we present a new authentication mechanism for a distributed system. The data of events are recorded in a series of blocks by certain specific devices and clouds at the edge side. These data are authenticated and properly stored at several locations in order to keep data consistency. Event data are usually processed locally and do no travel to far away data center. Computation performed at the edge reduces the latency and accelerates the response of service request [1]. Blockchain is considered as one type of distributed ledger technology. Blockchain technology monitors the activities of trading and enhances the immutability, scalability, and security of the supply chain [2]. The scenarios in a system application are described as follows.

This is an example of consumer-to-consumer business model in which people may make use of this platform. It would benefit both parties who exchange an item for another item under urgent demand. Similar to many software applications, the initial target may be set to campus. Students with limited budget may obtain what they need, including books, computers, study supplies, etc., through the exchange bulletin service. Some application software is only compatible with Mac Operating System. For example, the digital audio workstation software of Logic Pro X does not provide a Windows version. A student who would like to use Mac-only software considers purchasing a Mac computer. Thus, she/he may exchange one of his machines or computers for a Mac computer.

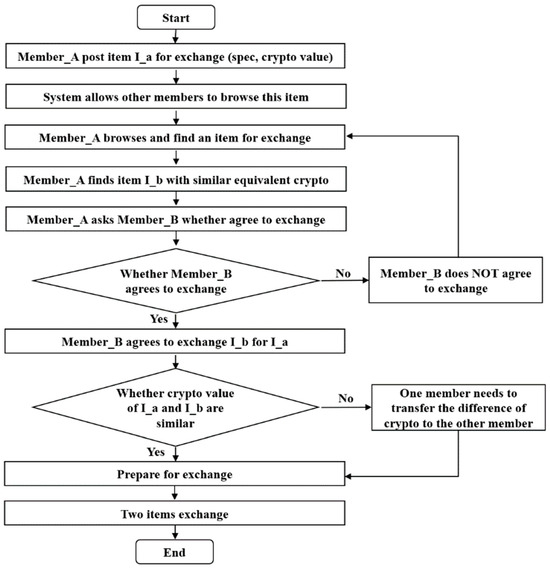

This platform may realize the scenarios. The flow chart of exchange is shown in Figure 1. A member in this platform may place an item such as a smartphone for exchange. Then, other members may browse around and see the item in the platform. At the same time, the member searches for what they need—for example, a pad—in the platform. Later, we asked these members one by one if any were interested in exchanging their items to receive a smartphone. Once a match is found, the exchange process may start. The member who initiates this event informs Edge_Cloud, ANOD, ANB, and some nearby nodes, which will verify/validate the event. This is a C2C model, but it can be used in B2C or even B2B models as well. E-commerce retailers, such as Amazon, allow people to purchase or sell merchandise. Some people post items for exchange on social network software, such as Facebook marketplace. However, it is not easy to detect online shopping scams. The platform that we propose is member-based with deposits and is good for merchandise exchange. If the value of the two items for exchange are about the same, it would be beneficial for two parties without additional cost.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of item exchange.

2. Background and Related Work

These merchandise exchanges are all based on equivalent or similar asking prices. The two parties in the exchange are called Initiator_of_Event and Responder_of_Event. For high price trading or exchange, the price determination can refer to the market value.

The word “token” used in our proposed system has the meaning of “credit”. All registered members are given a certain number of tokens upon registration. If the asking prices of the items from the two parties are not equivalent, the party with the lower-price item may bargain or pay the price difference with tokens of the platform.

There could be a platform with the authentication mechanism that helps these people fulfill their demand to facilitate trading between different parties as well as implement ledger keeping. Additionally, the platform plays the role of middleman/agent in between two parties to ensure the traded items received by the other party safely. In case of any quality issue or lack of satisfaction, the agent must be able to resolve it. The participants of the platform need to provide a certain amount as a deposit before the trade. The amount usually depends on the general trading value so that some issues in a trade may be compensated by a deposit from a member.

There are numerous applications in a distributed system: video streaming, social media applications, telecommunication network, financial services, Internet of Things (IoT), and distributed artificial intelligence. In this paper, we introduce an authentication method used in a distributed system to fulfill the demand in merchandise exchange application. Our distributed system provides collaborative computing capability, where data may be validated and stored across multiple machines. Some blockchain systems are primarily designed for transaction-record-keeping in digital payment, such as Bitcoin. Blockchain, known as a record-keeping technology, was introduced by Satoshi Nakamoto in 2008 [3]. Some people tried to move beyond the basic transaction application and developed Ethereum to perform some additional tasks upon the framework, such as smart contracts [4]. Originally, this distributed ledger was designed as fully decentralized based on proof of work. The generation of a Bitcoin block is designed to be around 10 minutes [5]. Bitcoin handles around seven transactions per second, and it generally requires six confirmations to ensure that the transitions in a block are actually incorporated in the blockchain [6]. If this is used for commercial payment application, one hour of processing time is usually required, and it is not acceptable. There is a constraint in the practical application of Bitcoin, which is not scalable. Additionally, the price of Bitcoin occasionally fluctuates dramatically. If Bitcoin is used for the payment of purchasing an item, the price of the item needs to be changed all the time due to the fluctuation of market value of Bitcoin. There are many factors, including political issues and regulation changes, that affect the value of Bitcoin. Based on the design of Bitcoin, the supply cap of Bitcoin is limited to 21 million. The keys of Bitcoin owned by people may get lost; this also affects the total amount of Bitcoin in the market.

To keep it stable and reduce the fluctuation, the design concept of the token in this proposed system is linking to a weighted value of some major fiat currency, such as USD, EUR, GBP, and JPY. The price of the token in this proposed system would be dynamically adjusted by the system operator.

Ethereum 2.0 is based on the concept of Proof of Stake as a consensus mechanism [7]. The challenges and criticisms about Ethereum 2.0 include wealth concentration, centralization, lack of incentives, security concerns, complexity, and lack of fairness [8]. There is a penalty for validators who have machine downtime or network failure. If the key of a validator is utilized by several machines accidentally, during maintenance, there could be slashing because of double voting. The staking of Ethereum encounters four challenges: wallet configuration, validator key security, stable validator node operation, and profitability [9]. A node needs to stake a certain amount of cryptocurrency in order to become a validator. However, most node owners usually do not have such amounts of cryptocurrency and are unable to connect to the Ethereum network consistently; thus, they take their limited cryptocurrency to some agents, resulting in high possession of Ethereum ETH tokens by these agents. This favors those users who already have considerable amounts of ETH. Therefore, people have concerns about wealth concentration because wealthy users have much higher influence on the network system [8]. Ethereum was initially designed as a fully decentralized system; however, the staking method introduced in Ethereum 2.0 affects the original concept of full decentralization. EOS is based on the delegated proof of stake (DPoS) consensus mechanism [10]. Although EOS features high throughput [11], participants without sufficient stakes of EOS delegate their resources to some representative nodes [12]. The voting delegates of DPoS range from 21 to 101 [13]. There is a similar centralization situation with EOS. Most of the voting powers are possessed by a few voting proxies [14]. More than 55% of total EOS supply were owned by one wallet as of 1 August 2024 [15].

In Table 1 we mention some blockchain technology along with the proposed system for reference. The claimed transaction per second of Ethereum 2.0 is 100,000 [16]. However, it encounters some problems described previously. Although the claimed transactions per second of EOS are quite high, in the range of 5000 to 1,000,000 [17], people believe EOS does not go anywhere. There are many problems with the activities of EOS development. There is conflict between EOS founder and EOS managers, and the crypto price of EOS has continued to decline in recent years. Bitcoin, Ethereum, and EOS are all global peer-to-peer decentralized systems. Our proposal is a balanced distributed system. Because we do not build a blockchain system, it is not our intention to compare our system with some famous blockchain directly. Through providing this table, readers may further understand our proposed method and take a glance at some difference from these blockchain systems.

Table 1.

Comparison of Bitcoin, Ethereum, and the proposed system.

As shown in the security part of the table, the potential security threats of Bitcoin include phishing scam [18]. The potential security threats of Ethereum include phishing scam, reentrancy, and eclipse attack [19,20]. The potential security threats of EOS include transfer error prompt [21]. In our proposed system, it is protected by some features such as risk flow of chief chain (CC) and Telstar chain (TC). The member- and machine-based security mechanism provides enhanced security. Additionally, in case there is any discrepancy, it can be recovered or compensated by deposit and insurance.

As far as other proposals related to proof of something, these proofing methods provide different approach of authentication for reaching consensus. NEM network adopts proof of importance, in which the concept of amount of vested cryptocurrency is the base of importance calculation [22]. The scalability of peer networks using the Byzantine fault tolerance (BFT) algorithm and its variants is low due to significant incensement on messaging overhead [23]. Song, H. et al. proposed a proof of contribution (PoC) mechanism in which the node that contributed most obtains the privilege to write to the ledger [24]. Huang, J. et al. proposed a credit-based PoW mechanism in which malicious Internet of Thing (IoT) nodes would be panelized by deduction in credit value [25]. Hao, Y. et al. indicated that private blockchains such as Hyperledger may provide better flexibility for commercial application [26]. It is true that the effort of broadcasting and being verified by global nodes in a fully decentralized system is very resource consuming. In our proposed system, events are not broadcasted to all nodes in the system for authentication.

Chaudhry, N et al. compared several consensus algorithms and discussed that ELASTICO algorithm, one of the sharding algorithms, divides the network into many committees, in which consensus achieved using the Byzantine method in a probabilistic manner, and the results are merged by the final committee [27]. Kokoris-Kogias, E. et al. presented OmniLedger with ByzCoinX, a BFT-based consensus; this indicated that the approach of sharding by increasing the number of shards reduced the loading of each node and introduced the Byzantine Shard Atomic Commit (Atomix) protocol for handling transactions across shards atomically [28]. Platt, M. et al. found that the energy consumption of several non-permission proofs of stake (PoS) were very dissimilar and that energy consumption may be reduced by the limitation of the number of validators in permissioned blockchain [29]. Andola N. et al. proposed a proof of elapsed work and luck (PoEWAL) consensus method in which cryptographic puzzles are solved by Internet of Thing devices in an assigned time frame. Collisions of nodes with the same highest number of consecutive zeros are resolved by proof of luck [30]. Chen, S. et al. proposed proof of solution (PoSo) to replace the mathematic puzzle of proof of work (PoW) with an optimization problem [31]. Sayeed, S. et al. compared proof of work, proof of stake (PoS), and delegated proof of stake (DPoS) in terms of energy cost, decentralization, security, and processing speed; they mentioned that all three approaches are vulnerable to 51% attack and that the network of DPoS would slow down due to large number of validators [32]. Song R. et al. proposed a competition-based proof of stake (CPoS) method to avoid the nodes with many stakes, easily becoming richer due to the advantage of holding more stakes in the block generation process [33]. Bravo-Marquez, F. et al. proposed a machine-learning-competition-based consensus mechanism and required participants to perform prediction tasks based on the machine learning process [34]. Li C. et al. proposed a method for an improved PBFT reward and punishment consensus mechanism for resource-limited IoT devices [35]. In the proof of activity (PoA) protocol, a hybrid consensus mechanism, a new block is generated through PoW and then the verification process of appending transaction data is based on PoS [36]. Dziembowski, S. et al. proposed a proof of space (PoSP) protocol as an alternative to PoW; the service requestor must provide a certain amount of hardware memory space through graphs with high pebbling complexity and Merkle hash-trees, instead of providing computation [37,38]. All these protocols provide unique techniques which are beneficial from certain perspectives. However, there is always a tradeoff. Every technique faces some challenges.

There are potential problems with proof of stake. Two strategies of malicious attack by validators with less than one-third of stake on Ethereum 2.0 have been discovered. An attack named asdecoy-flip-flop by adversaries may delay the finalization of the LMD GHOST of Ethereum 2.0 [39,40]. Some nodes might not participate in voting actively because it required 24 h a day, 7 days a week non-stop network connection and running the program. Additionally, voting requires certain knowledge and effort. In Ethereum 2.0, there is a penalty if a validator goes offline. How the penalty is executed is fully determined by the developer of the cryptocurrency. This is against the concept of a decentralized system. Fischer mentioned the consensus problem as an agreement on a piece of data among the processes through cooperation [41]. The consensus mechanism of PoS is associated with the amount of stake of a node to be staked. For PoS consensus, there is a situation similar to a bank run; if the price of the target cryptocurrency keeps dropping for some reason, stakeholders should have an urgency to rush to withdraw the stake at the same time. Due to the staking requirement of validators, there will be no sufficient nodes executing the consensus mechanism based on proof of stake and thus, the entire system would breakdown.

In the example of Ethereum 2.0, most people do not have 32 ETH, and most of the staking of ETH is possessed by few pools, such as Lido, Coinbase, Kraken, RocketPool. The change in Ethereum makes it move toward centralization. Many staking pools are located in a single country, such as USA or China. For example, in the USA, it is monitored by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). The change in governmental regulation on cryptocurrency and staking pools may affect the future of these cryptocurrency significantly. A staking pool could be forced to stop running if there is a new regulation that the operation of a staking pool does not fully comply with. In this case, the PoS system would not function normally because the majority of validators cannot provide non-stop operation.

3. Functions and Benefits

The following are functions and benefits in terms of the application described in Section 1.

- Convenience: It is more convenient to find appropriate business for small business entities;

- Data management: Event data are properly recorded and data modification is allowed for refund or error-correction;

- Security: The closed membership-based system lets users have better confidence and trust in the system;

- Privacy: The closed system prevents the data from spreading to other people outside the system;

- Incentive: The authenticators are rewarded for performing authentication tasks.

4. Method and System Model

4.1. Overview

The characteristics of blockchain include a decentralized network and an immutable ledger. We would name our system a distributed system rather than a blockchain to avoid confusion. Although most activities are carried out at the edge of the network, our system is not fully decentralized. The event data are not propagated to the entire network. Additionally, under certain circumstances, event data may be modified at TC. Thus, the data are not entirely immutable. A list of abbreviations of terms in this paper is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

List of abbreviations.

Chief chain (CC) and Telstar chain (TC) are two types of chains proposed in this paper. CC consists of blocks of high-risk events and essence data of low-risk events. TC consists of blocks of low-risk events. These uncommon terms with distinctive functionality seen in this paper are not from published work. Asteroid_Node_on_Duty (ANOD), Asteroid_Node_of_Backup (ANB), Asteroid_Node, and Meteoroid_Nodes are nodes in the distributed system proposed in this paper. ANOD performs the primary duty of tasks of coordination. ANB performs the duty of secondary coordination tasks. Additionally, when there is something wrong with ANOD, ANB immediately takes over all tasks of ANOD.

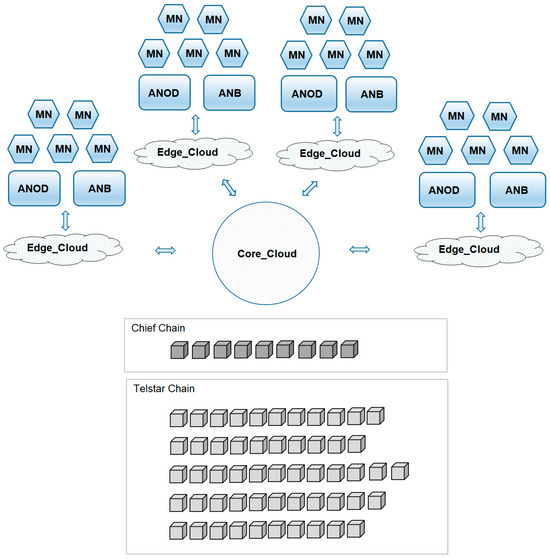

We propose an architecture that is an Edge_Cloud system with the following characteristics. The system diagram is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

System diagram.

- Parallel processing: Events are processed in parallel in all sub-regions simultaneously. Thus, the volume of event data is handled by the proposed system more efficiently. ANOD, ANB, and Edge_Cloud in local area may facilitate local data processing and storage simultaneously in all sub-regions. Additionally, both high-risk and low-risk events are processed through CC and TC simultaneously;

- Proximity for determining the verification and authentication for an event;

- Authentication methods with adjustment in difficulty setting for different situations;

- Risk determinant and risk flow;

- Integration of TC with CC;

- Chief chain (CC) archive.

4.2. User and Machine Identifications

In the applications described in Section 1, users are registered members of service. All users and nodes may be identified and tracked if there is a security concern. Access to the platform may be controlled through combining three factors: knowledge factor (user login verification), possession factor (hardware verification), and inherence factor (biometric factor verification). The protocol to verify whether a machine in the system is authorized to participate in, such as Kerberos protocol, is determined by the system committee for that application.

4.3. Node

In this paper, Asteroid_Node generally refers to Full_Function_Asteroid_Node (FFAN) which are usually enterprise servers. There is another type of Asteroid_Node that performs certain tasks but not all; it is Partial_Function_Asteroid_Node (PFAN). For example, a retail store may act as a PFAN, however, it cannot perform the task of ANOD. The hardware machines of Asteroid_Nodes are servers or workstation in general. Meteoroid_Nodes are usually operated by an individual member in the system. The machines of Meteoroid_Node include personal computers, laptops, tablets, smart phones, etc. The system committee decides the authentication protocol (such as Kerberos), which verifies whether a machine in the system is authorized to participate.

4.4. Consensus and Authentication

Each event needs to be verified and authenticated by a certain number of authenticators. There are two types of nodes: Asteroid_Node and Meteoroid_Node. The consensus of the system relies on the collaboration task of Asteroid_Node and Meteoroid_Node. When a set of event data is sent to some nodes, these nodes perform verification first. The format of event data needs to be verified. Then, these nodes try to authenticate the event. In this paper, authentication of an event is analogous to the validation of transactions of a block in blockchain.

4.5. Proximity

The degree of proximity between an event and the authenticator is determined by following two factors:

- Internet Protocol address

If the headings of IP address are the same, they are considered to be in close proximity;

- 2.

- Physical location

When the authenticator is in the same geographical area (such as the same coverage of satellite wireless system) where the event occurs, it is likely with a high degree of proximity. The choice of nodes that receive event data is related to geographical location where the event is initiated (except for high-risk event).

4.6. Location and Sub-Region

- Location of Asteroid_Node

The registered location of the Asteroid_Node is used in the category of high-risk event data. When an Asteroid_Node is registered to the system, its physical location will be recorded. If the Asteroid_Node changes its location, the new geographical location must be updated.

- 2.

- Location of Meteoroid_Node

The registered location of the Meteoroid_Node is used in the category of high-risk event data. The temporary location of the Meteoroid_Node is used for the category of low-risk event data. The temporary location of the Meteoroid_Node may be determined by either wireline or wireless IP address.

Many sub-regions may exist in each region. One ANOD and one ANB work as local processing centers in each sub-region. The ANOD performs the primary tasks of maintaining the operation in the sub-region. The ANB acts as a backup role and takes over the tasks of the ANOD whenever the ANOD does not operate normally.

The definition of region and sub-region and their design depends on the application of the system. Initially, when the system starts operation, there may be several initial regions. As the frequency of events increases, some sub-regions may be formed in each region. The design of sub-region is usually based on a certain number of active nodes running in an area. The coverage and geographical size of the sub-region would be based on the number of users in that region.

4.7. Economic: Gratuity Token

The authentication of a block is processed using the method described in Section 4.9. The authenticators would obtain gratuity tokens for successfully authenticating an event provided by Initiator_of_Event, a node that initiates the event. The amount of gratuity tokens received is a weighted value based on the following criteria:

- Correct computation but not fast enough:

More gratuity tokens are received if the node performs more correct computations, which is a historical accumulated number of correctly computed block authentications. The node completes computation and meets the requirement of authentication, but it is not fast enough. That is, it is completed almost the same time but is not on the top list, which consists of very few nodes. In such cases, the node may claim this correct computation by sending a message to ANB that would check whether the node completes computation correctly and keep a record in the cloud.

- 2.

- Incentive for Meteoroid_Nodes:

Incentive for Meteoroid_Nodes is determined by the system; there more gratuity tokens for Meteoroid_Node and fewer gratuity tokens for Asteroid_Node. The reason for there being more gratuity tokens for Meteoroid_Node is to balance the computing capability of two types of nodes. In other words, the system would encourage Meteoroid_Nodes to contribute to the system so that the system will not be dominated by Asteroid_Nodes.

4.8. Process of Transmission

The event data propagate through the following process. As described above, the event data are generated by the Initiator_of_Event’s device and the Responder_of_Event’s device. Then, event data are sent to ANOD, ANB, some Asteroid_Nodes, and the Meteoroid_Nodes, with proximity listed in the table.

Each node establishes a node table which includes ANOD and ANB. Some adjacent Asteroid_Node and adjacent Meteoroid_Nodes with satisfied condition are also included in the table.

When a node is initiated, it needs to inform ANOD and ANB regarding its IP address and status. If this node does not know ANOD and ANB, it may ask its neighbor nodes for the information. Once it communicates with ANOD and ANB, ANOD will then provide the necessary information, including adjacent Asteroid_Nodes and Meteoroid_Nodes.

Every node needs to keep track of its current IP address and MAC address. If any node changes its IP address or anything is wrong in its MAC address, the node needs to inform ANOD and ANB, which will then inform those related nodes regarding the new IP address of the changed node and its status.

Every node maintains two node tables of IP address: one Asteroid_Nodes table and one Meteoroid_Nodes table. For a table of Asteroid_Nodes, it lists the IP address and status information of some Asteroid_Nodes in a region. For a table of Meteoroid_Nodes, it lists the IP address and status information of some Meteoroid_Nodes in a region. Each node has both Asteroid_Node table and Meteoroid_Node table. The node needs to ping some adjacent Asteroid_Nodes and adjacent Meteoroid_Nodes that are in the tables. Upon receiving the ping, these nodes reply with an ACK.

The risk may be determined by Initiator_of_Event based on the market value of the target commodity for exchange in an event. A high-risk event is transmitted to certain numbers of Asteroid_Nodes and Meteoroid_Nodes based on its registration location. A low-risk event is transmitted to certain numbers of nearby Asteroid_Nodes and Meteoroid_Nodes based on its proximity. All nodes that receive the event data need to perform format verification first. Depending on application, token sufficiency is used to determine whether the remaining token is sufficient for this event at this moment. A token sufficiency check may not be required in some applications—such as industrial Internet of Things, in which there is no need to set up token balance for an IoT device—or when the event is a commodity exchange in which paying is not required.

For an event involving token transfer, the token sufficiency check is performed through cloud computing. A node may send a request to Edge_Cloud, which is usually jointly administered by major ANODs, and will obtain the answer of whether the token is sufficient for this event. Edge_Cloud keeps the token balance of members in the sub-region and updates the token balance from the Core_Cloud periodically. Whenever there is a technical problem with Edge_Cloud or an Edge_Cloud needs help for some reason, the Core_Cloud provides support to Edge_Cloud.

After the format of event data are verified, the nodes try to perform authentication. The node authenticates successfully informs ANOD, ANB, and Edge_Cloud directly. All related nodes will know which node claims the authentication of this event from Edge_Cloud, and the next step is to confirm whether the authentication result is valid. This is called authentication-check which is performed by ANOD, ANB, and all related nodes.

4.9. Methods of Authentication Process

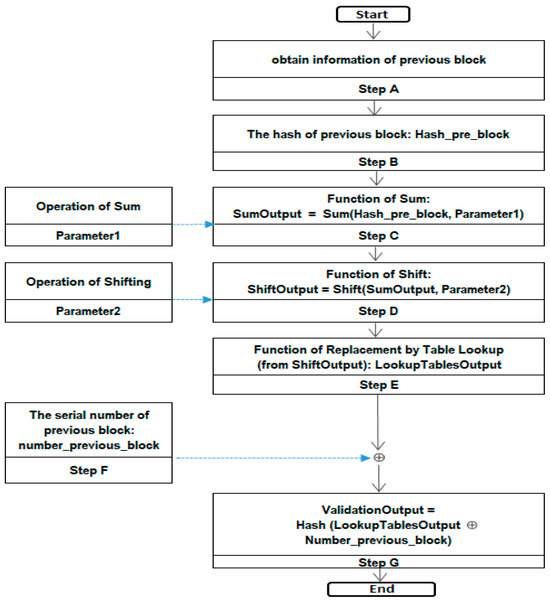

Four authentication methods are introduced here. The system committee of the specific application decides which method is adopted for all machines in the authentication process. After the format of an event is verified, a set of event data may be authenticated by nodes. All nodes start to perform the computing of the authentication process as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Authentication process one. Parameter 1 is an input value for step C. Parameter 2 is an input value for step D. The sign  represents XOR operation.

represents XOR operation.

represents XOR operation.

represents XOR operation.

Parameter1, parameter2, and Tables are variables. The authenticators try different values on the variables parameter1 and parameter2 for authentication. In this case, the input in Step F is the serial number of the previous block. If the event of an application occurs frequently, many events will occur within a certain period of time and the time interval between two adjacent blocks will be small. The information of the previous block and its serial number should be efficiently input to ensure the authentication computation is for the correct block.

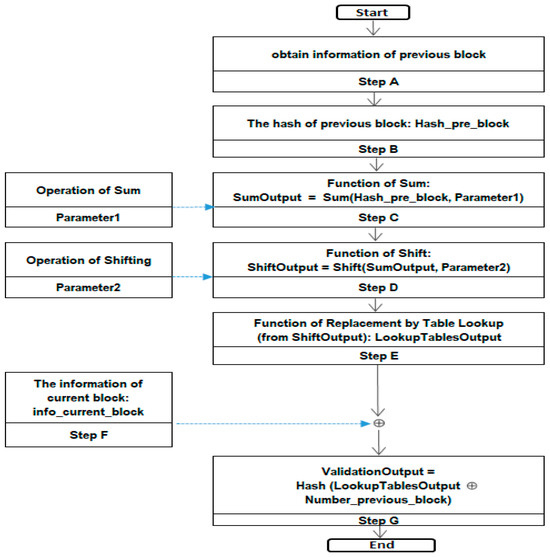

In consideration of other applications, the authentication process is slightly different from the first one, as shown in Figure 4. In this case, the input in Step F is the information of current block. If the event frequency of the application is extremely low, there will be very few events in a certain period of time. Hence, the time interval between two adjacent blocks will be very large. The input of the current block could provide information for the authentication computation.

Figure 4.

Authentication process two. Parameter 1 is an input value for step C. Parameter 2 is an input value for step D. The sign  represents XOR operation.

represents XOR operation.

represents XOR operation.

represents XOR operation.

Four example methods of authentication are described as follows. For the simplicity of illustration, we set the digits of OutputAuthentication as 16 digits.

4.9.1. Method 1

There is only one replacement table provided by the system in Step E. Nodes try different values of parameter2 to obtain the OutputAuthentication. The target is that OutputAuthentication needs at least a number nlead of leading F. For example, if nlead = 4, OutputAuthentication needs to be equal or larger than “FFFF000000000000”, as shown in (1).

OutputAuthentication ≥ FFFF000000000000

4.9.2. Method 2

There are several replacement tables provided by the system in Step E. Nodes obtain these replacement tables whenever there is a software update. Nodes may try to use any one of these replacement tables in the authentication process.

As shown in figures above, nodes try different values of parameter2 in Step D and use one of the replacement tables in Step E. The target is that OutputAuthentication needs at least a number nlead of leading 0. For example, if nlead = 8, it requires that OutputAuthentication be no larger than “00000000FFFFFFFF”, as shown in (2).

OutputAuthentication ≤ 00000000FFFFFFFF

4.9.3. Method 3

The variable Method3_hash is the last nmethod3 digits of the hash of the previous block. OutputAuthentication-partial refers to the partial continuous nmethod3 digits of OutputAuthentication in Step G. The requirement is (3):

Hashpartial-n-previous-block = OutputAuthentification-partial

That is, the partial continuous nmethod3 digits of OutputAuthentication should be exactly the same as the last nmethod3 digits of the hash of previous block. For example, the hash of the previous block is “0123456789ABCDEF”. Therefore, the last five digits of the hash of the previous block is “BCDEF”.

The partial five consecutive digits of OutputAuthentication need to be exactly the same as the last five digits of the hash of previous block. The following are some examples that meet the requirement:

- 01289ABCDEF34567

- 0123BCDEF456789A

- 01BCDEF456789A23

- 2BCDEF45678901A3

4.9.4. Method 4

Method4_hash is the first nmethod4 digits of the hash of previous block. Method4_OutputAuthentication is the remainder of modulus operation of OutputAuthentication based on divisor Divr. The variable divisor Divr is determined by the system.

The requirement is shown in (4):

Hashpartial-n-previous-block = OutputAuthentification % Divr

That is, the remainder of modulus operation of OutputAuthentication should be exactly the same as the first nmethod4 digits of the hash of the previous block.

An example of replacement by table lookup is as follows:

The raw data is in hexadecimal representation: xy.

For instance, the original hex is 9A. Then, by looking up the table, x = 9 (row) and y = A (column), we may find 1E. Thus, the replacement is 9A replaced by 1E.

4.9.5. Almost-There Authentication

Regarding the amount of almost-there authentication, the node computes the result which is very close to the target while the other node obtains the target result at this time.

For example, the target is OutputAuthentication with the number nlead of leading F.

In this example nlead = 6, the requirement is shown in (5).

OutputAuthentification ≥ FFFFFF0000000000

The following results of Node-A are considered as almost-there authentication:

- FFFFFA0000000000

- FFFFFEF5E3253A5B

- FFFFF356E56356E5

- FFFFFC0000000000

- FFFFFE0000000000

The result obtains only five leading digits of F, one digit less than the required six leading digits of F. At this time, the other node (Node-B) obtains the result of FFFFFF0000100001.

Node-B successfully authenticates the block at this run. The result of Node-A is very close to the target—only one digit less than the requirement—and there is partial credit for this effort. Node-A may inform ANOD, ANB, and some adjacent nodes. The number of almost-there authentications is counted and considered in the historical credit of this node, as described in the Section 4.12.

Table 3 shows the columns in block header and transaction of a block. The content of Column 10 hash_block_transaction_data is the hash value of Block Transaction in the current block. The concatenation of Column 1 through Column 10 is used for the input of Step A in Authentication Process One and Authentication Process Two.

Table 3.

Column of block header and block transaction in a block.

4.10. Convergence from TC to CC

There is a variable in data field of conspectus “risk_category”. When an event occurs, Initiator_of_Event and Responder_of_Event needs to categorize the risk level of this event and get agreement from ANOD. Then, which nodes the event data would be sent to and which flow the process would go through are determined based on the value of risk_category.

For the low-risk scenario, the flow of transmission and authentication is based on the process of TC. The event data is transmitted to a certain number of Asteroid_Nodes and Meteoroid_Nodes. After a sufficient number of authentications by Asteroid_Node and Meteoroid_Node, the events are saved to TC. ANOD and ANB in the Responder_of_Event region handle the TC of event data. The authentication for low-risk scenarios is based on the concept of lower difficulty. The difficulty target set for the low-risk process is much less than the difficulty target set for the high-risk process. After accumulating for a certain number of blocks, the essence data of these TC_blocks with low_risk_events will be written to CC. The equivalent market value of each event of the low-risk process is less than that of high-risk process. The advantage of this design is that the reduced difficulty results in less authentication process time. It can be considered a valid event as long as it is authenticated in the low-risk process on TC before it is consolidated in CC. This mechanism may reduce overall event processing time due to lower difficulty and allow the data to be modified in TC before it is consolidated to CC.

ANOD in each region or sub-region needs to perform this task when the last two block serial numbers of CC are “00” by the method of authentication and tourney with priority. There are several ANOD; these nodes need to compete to write to CC. The winner of the tourney may write the data onto the block ending with two zeros in the block serial number.

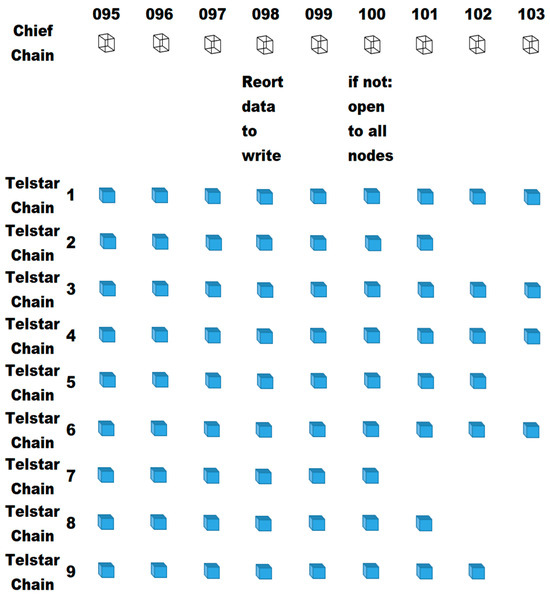

All ANOD need to report to the system two blocks before the block serial number ended with two zeros in CC. As shown in Figure 5, if the last three digits of the block number ended with zero is 100, right upon the last three digits of the block of 098 is formed (before the last three digits of the block of 099 is formed), all ANOD need to report to the system no matter if they have any data to be written to CC or not. If no Asteroid_Nodes have data to be written to CC, the block with zero on both tens digit and units digit of block number is open to all nodes for the tourney.

Figure 5.

TC contest on writing to CC.

There is one ANOD to deal with the TC in a region or sub-region. Each TC competes based on the authentication method described in the Section 4.9. If one TC did not win the tourney 10 times consecutively, it would automatically get priority to write to CC without winning the 11th tourney.

For example, if one TC did not win the tourney successfully on block numbers 100, 200, 300, 400, 500, 600, 700, 800, 900, and 1000, at the time when block 1098 is formed, this ANOD with this TC would inform all ANOD in the system that it has TC to write to CC but failed ten times. There is a priority field with a default value of zero in the data structure of the authentication process. The system would reply this ANOD to agree that this TC should change its priority to 1 if no other TC encounters the same situation. Then, this TC with priority 1 would have higher priority in next tourney.

The priority could be achieved through the settings of authentication. For instance, the standard digit required in Method1 to win the tourney is to reach the target of OutputAuthentication with the nlead of leading Fs.

In the case of priority 1, the digits required in Method1 to win the tourney to reach the target of OutputAuthentication become the number of (nlead −2) of leading Fs. For instance, if the standard nlead is 6, the requirement of OutputAuthentication is equal to or larger than “FFFFFF0000000000”. The TC with priority one only needs to achieve 4 leading Fs—that is, OutputAuthentication is equal to or larger than “FFFF000000000000”.

4.11. Balance Audit

The balance of some members is audited periodically. For example, the balance of event data related to some members is audited thoroughly every two months. The proposed balance on each event is reviewed by auditors to examine whether there is any defect, such as fraud or double-spending.

- Low-risk: It is not necessary to review the balance of some members with only low-risk event data in general. However, random inspection could be performed occasionally.

- High-risk: It is necessary to review the balance of those members with high-risk event data.

Regarding the duration of time that the proposed token has been kept, each week for example, the balance of the proposed token of each member is checked. Every 4 weeks, the average of the weekly balances of each member will be calculated. High average balance infers that the time duration that the proposed token has been kept by this member is long.

Regular review will be held. The way to select an auditor is based on historical credit. Those nodes with higher historical credit are randomly selected to be auditors to review the balance of members.

4.12. Historical Credit

The historical credit of a node is the weighted sum of these four factors:

- The number of successful authentications.

- The number of correct but not fast enough computation that the node claims to ANB.

- The number of almost-there authentications.

- The duration to keep the token.

5. Simulation Result and Analysis

The simulation is performed with ns3/C++, running on Ubuntu 22.04.1 LTS Linux on an Intel Core i7-7700HQ 8 core with the support of a GPU Nvidia GeForce FTX1050. Multi-thread programming is adopted to simulate the authentication process of various nodes. The data transmission rate is set to 10 Mbps. SHA-256 is applied for the algorithm of hashing. The nodes try different parameters in method one to meet the authentication requirement where nlead is 4. Table 4 shows the simulation result of the authentication process. The time unit is seconds. In each round of authentication competition, the time spent by the first two nodes which successfully authenticated with the shortest time among six nodes that performed authentication tasks are shown in the table. The column time_of_authentication is the time in which nodes successfully completed authentication. The column time_finished transmission and responding is set when the ANOD and Edge_Cloud received the message of successful authentication.

Table 4.

Time of authentication and authentication_check.

The column after_add_time_for_authentication_check is set when the nodes complete authentication_check. The time of the first two nodes completing authentication in the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 5th runs are 0.005001815 s and 0.006928820 s, 0.007173124 s and 0.007407925 s, 0.007172958 s and 0.007259180 s, 0.0054323 s and 0.005269173 s, and 0.005471957 s and 0.005415098 s, respectively. The time for a low-risk event to be authenticated successfully is usually less than 10 milliseconds.

The shortest and longest times to complete authentication successfully were 0.002405245 s and 0.837964 s, respectively, among all rounds. Only the first two nodes which claim successful authentication are counted in low-risk events in this example. The two times in which the first two nodes finished authentication were less than 0.01s. Therefore, there could be up to one hundred blocks to be authenticated and generated per second per sub-region, resulting in up to 25,000 blocks to be authenticated and generated if there are 250 sub-regions in this example.

An assumption is made for this example: supposing that the minimum deposit requirement is set to be much higher than the maximum amount of token expense in low-risk events in this type of business. The time for token checking may be neglected in this case since the insufficiency of token is covered by the deposit. The time for node verification may be neglected since the verification is done through hardware information in the nodes before event occurs in most applications.

Instead of requiring large deposits of tokens, another approach is to set up a cut-off-point for token sufficiency. If the number of tokens for a low-risk event is less than the cutoff point, the nodes do not need to ask Edge_Cloud to perform a token sufficiency check. Any discrepancy would be resolved by the deposit of a node. In this example of all low-risk events, the task of risk declaration is not necessary and is thus neglected. Regarding the assumption for low-risk events, the requirement of number of nodes that authenticate successfully is two. Therefore, if there is one event included in a block, the number of transactions per second on low-risk event application could be as high as 25,000 TPS.

The assumptions are as follows: there is one ANOD and one ANB per sub-region; both Core_Cloud and Edge_Cloud function normally; and all ANOD and ANB work normally. These assumptions must be valid for the estimation.

In our proposed system, there are operators monitored by a system committee to manage the operation of the system. The processing speed of Bitcoin is seven transactions per second. However, our system is not a blockchain system, and we do not intend to compare it to current typical blockchain systems. The information on Bitcoin is only for reference.

Although the processing speed in our proposed system is faster, it is not fair to directly compare the processing speed of two kinds of systems due to the different natures of systems. Our system is for distributed computing, and it is well known that a distributed system may aggregate computing power of different machines from different areas. The nature of Bitcoin is seen on the title of its white paper: “Bitcoin: a peer-to-peer electronic cash system”. The transfer of Bitcoin does not involve any third parties, including financial institutions [42]. It is designed for the purpose of disintermediation. However, Bitcoin is not widely used in retail stores because the price of Bitcoin fluctuates too much and because it usually takes one hour to finally confirm a transaction.

The scenarios of the application in the proposed system are for commercial item exchange. Sometimes, a person received an incorrect item due to a shipping mistake. Based on the basic nature of Bitcoin, it does not provide the function of dealing with refunds because it tries to avoid any trusted third party. Bitcoin does not fulfill the basic need of commercial item exchange in our proposed system. Some people consider that Bitcoin is more like a commodity due to its limited quantity, similar to the nature of gold or silver.

In the case of other types of applications—such as Internet of Things, that is primarily for record keeping—when there is no token involved for the event, the token sufficiency check may be neglected. Then it is not necessary to set the minimum deposit to a large amount for the system.

6. Conclusions

The proposed system may be applied to certain applications, such as merchandise exchange services. The details of the design of the system can be adjusted to fit the application. The function, benefit, and characteristics are shown in Section 3.

We do not try to compare our member-based distributed system to Bitcoin directly. All members are registered through credit checks and with certain amounts of deposit or credit. The security mechanism of the member management of the organization does provide additional support for the security of the proposed system. In particular, most events take place in a situation in which there is no need to receive endorsement from ANOD for the setting of risk level.

In addition, the deposit of each individual node in the proposed system does provide some protection with the sense of the function of purchasing an insurance plan. The other approach is that the system committee may decide to use the interest of deposit to purchase an insurance plan from an insurance company for any discrepancy occurred in the process; the impact of data incorrectness by any reason may be covered by the insurance plan although it is very unlikely to happen.

Moreover, some sagacious designs—such as the parallel processing of CC and TC, events simultaneously processed by all sub-regions, and convergence from TC to CC—reinforce the overall system advantage. The nodes are hardware-intrinsic and pre-registered; thus, the time of identity verification may be minimized. The industrious task performance and excellent teamwork of Edge_Cloud, ANOD, and ANB contribute to the proper functionality of event processing at a fast pace. The tradeoff for fast processing is that each sub-region requires the continuous network-connected duty-performing of Edge_Cloud, ANOD, and ANB. The fast-processing mechanisms are primarily designed for low-risk events. Time of event processing is not the first priority for high-risk events; consequently, it is better to be prudent to deal with high-risk event with strict requirement of a larger number of nodes to accomplish successful authentication.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.-J.W., Y.-C.C. and M.-C.C.; methodology, J.-J.W., Y.-C.C. and M.-C.C.; software, J.-J.W. and Y.-C.C.; validation, J.-J.W., Y.-C.C. and M.-C.C.; investigation, J.-J.W., Y.-C.C. and M.-C.C.; resources, J.-J.W., Y.-C.C. and M.-C.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.-J.W.; writing—review and editing, Y.-C.C. and M.-C.C.; visualization, J.-J.W.; supervision, Y.-C.C. and M.-C.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mishra, K.; Rajareddy, G.N.V.; Ghugar, U.; Chhabra, G.S.; Gandomi, A.H. A Collaborative Computation and Offloading for Compute-Intensive and Latency-Sensitive Dependency-Aware Tasks in Dew-Enabled Vehicular Fog Computing: A Federated Deep Q-Learning Approach. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2023, 20, 4600–4614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, A.; Nor, R.M.; Mansor, H. Amiruzzaman Leveraging Decentralized Internet of Things (IoT) and Blockchain Technology in International Trade. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Cyber Security and Internet of Things (ICSIoT), Paris, France, 15–17 December 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, A.; Gautam, S.; Abidin, S.; Bhushan, B. Blockchain technology-future of IoT: Including structure, limitations and various possible attacks. In Proceedings of the 2019 2nd International Conference on Intelligent Computing, Instrumentation and Control Technologies (ICICICT), Kannur, India, 5–6 July 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; Volume 1, pp. 1100–1104. [Google Scholar]

- Antonopoulos, A.M.; Wood, G. What is Ethereum, in Mastering Ethereum: Building Smart Contracts and DApps; O’Reilly Media: Boston, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum, K. The Blockchain, in Grokking Bitcoin; Manning: Shelter Island, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 163–203. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, K.-Y. Cryptocurrency and double spending history: Transactions with zero confirmation. Econ. Theory 2022, 75, 453–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; Li, S.; Kraner, B.; Zhang, L.; Tessone, C.J. Analyzing Reward Dynamics and Decentralization in Ethereum 2.0: An Advanced Data Engineering Workflow and Comprehensive Datasets for Proof-of-Stake Incentives. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.11170. [Google Scholar]

- Asif, R.; Hassan, S.R. Shaping the future of Ethereum: Exploring energy consumption in Proof-of-Work and Proof-of-Stake consensus. Front. Blockchain 2023, 6, 1151724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takei, Y.; Shudo, K. Effective Ethereum Staking in Cryptocurrency Exchanges. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Blockchain (Blockchain), Copenhagen, Denmark, 19–22 August 2024; pp. 332–339. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, H.; Hironaka, S.; Shudo, K. Quantitative Analysis of the Reward Rate Disparity Among Delega-tors in a DPoS Blockchain. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Big Data and Smart Computing (BigComp), Bangkok, Thailand, 18–21 February 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 136–142. [Google Scholar]

- Haque, E.U.; Baig, M.S.; Ahmed, A.; Ahmad, A.; Alajmi, M.; Ghadi, Y.Y.; Alkahtani, H.K.; Akhmediyarova, A. Scalable EdgeIoT Blockchain Framework Using EOSIO. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 41763–41772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovezik, C.; Karakostas, D.; Kiayias, A. SoK: A stratified approach to blockchain decentralization. In Financial Cryp-Tography and Data Security 2024: Twenty-Eighth International Conference; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Haque, E.U.; Shah, A.; Iqbal, J.; Ullah, S.S.; Alroobaea, R.; Hussain, S. A scalable blockchain based framework for efficient IoT data management using lightweight consensus. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zheng, W.; Lu, D.; Wu, J.; Zheng, Z. Understanding the decentralization of DPoS: Perspectives from da-ta-driven analysis on EOSIO. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.06187. [Google Scholar]

- Tahiri, V. EOS Price Prediction 2024: EOS Price Analysis: CCN. 1 August 2024. Available online: https://www.ccn.com/analysis/crypto/eos-price-prediction/ (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Rosa-Bilbao, J.; Boubeta-Puig, J. Ethereum blockchain platform. In Distributed Computing to Blockchain; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 267–282. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, B.; Luthra, D.; Cole, Z.; Blakely, N. EOS: An architectural, performance, and economic analysis. Retrieved June 2018, 11, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Conti, M.; Kumar, E.S.; Lal, C.; Ruj, S. A Survey on Security and Privacy Issues of Bitcoin. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2018, 20, 3416–3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dika, A.; Nowostawski, M. Security Vulnerabilities in Ethereum Smart Contracts. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Internet of Things (iThings) and IEEE Green Computing and Communications (GreenCom) and IEEE Cyber, Physical and Social Computing (CPSCom) and IEEE Smart Data (SmartData), Halifax, NS, Canada, 30 July–3 August 2018; pp. 955–962. [Google Scholar]

- Henningsen, S.; Teunis, D.; Florian, M.; Scheuermann, B. Eclipsing Ethereum Peers with False Friends. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1908.10141. [Google Scholar]

- Quan, L.; Wu, L.; Wang, H. EVulHunter: Detecting fake transfer vulnerabilities for EOSIO’s smart contracts at webassembly-level. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.10362. [Google Scholar]

- Belfer, R.; Kashtalian, A.; Nicheporuk, A.; Markowsky, G.; Sachenko, A. Proof-Of-Activity Consensus Protocol based on a Network’s Active Nodes. In CEUR Workshop Proceedings [University Publisher]; Missouri University of Science and Technology: Rolla, MO, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Baliga, A. Understanding blockchain consensus models. Persistent 2017, 4, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H.; Zhu, N.; Xue, R.; He, J.; Zhang, K.; Wang, J. Proof-of-Contribution consensus mechanism for blockchain and its application in intellectual property protection. Inf. Process. Manag. 2021, 58, 102507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Kong, L.; Chen, G.; Wu, M.Y.; Liu, X.; Zeng, P. Towards secure industrial IoT: Blockchain system with cred-it-based consensus mechanism. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2019, 15, 3680–3689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Li, Y.; Dong, X.; Fang, L.; Chen, P. Performance Analysis of Consensus Algorithm in Private Blockchain. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Changshu, China, 26–30 June 2018; pp. 280–285. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhry, N.; Yousaf, M.M. Consensus algorithms in blockchain: Comparative analysis, challenges and opportu-nities. In Proceedings of the 2018 12th International Conference on Open Source Systems and Technologies (ICOSST), Lahore, Pakistan, 19–21 December 2018; pp. 54–63. [Google Scholar]

- Kokoris-Kogias, E.; Jovanovic, P.; Gasser, L.; Gailly, N.; Syta, E.; Ford, B. OmniLedger: A Secure, Scale-Out, Decentralized Ledger via Sharding. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), San Francisco, CA, USA, 20–24 May 2018; pp. 583–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, M.; Sedlmeir, J.; Platt, D.; Xu, J.; Tasca, P.; Vadgama, N.; Ibanez, J.I. The Energy Footprint of Blockchain Consensus Mechanisms Beyond Proof-of-Work. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 21st International Conference on Software Quality, Reliability and Security Companion (QRS-C), Hainan, China, 6–10 December 2021; pp. 1135–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Raghav; Andola, N.; Venkatesan, S.; Verma, S. PoEWAL: A lightweight consensus mechanism for blockchain in IoT. Pervasive Mob. Comput. 2020, 69, 101291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Mi, H.; Ping, J.; Yan, Z.; Shen, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhang, N.; Xia, Q.; Kang, C. A blockchain consensus mechanism that uses Proof of Solution to optimize energy dispatch and trading. Nat. Energy 2022, 7, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayeed, S.; Marco-Gisbert, H. Assessing Blockchain Consensus and Security Mechanisms against the 51% Attack. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Song, Y.; Liu, Z.; Tang, M.; Zhou, K. GaiaWorld: A Novel Blockchain System Based on Competitive PoS Con-sensus Mechanism. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2019, 60, 973–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo-Marquez, F.; Reeves, S.; Ugarte, M. Proof-of-Learning: A Blockchain Consensus Mechanism Based on Machine Learning Competitions. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Decentralized Applications and Infrastructures (DAPPCON), Newark, CA, USA, 4–9 April 2019; pp. 119–124. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Zhang, J.; Yang, X.; Youlong, L. Lightweight blockchain consensus mechanism and storage optimization for re-source-constrained IoT devices. Inf. Process. Manag. 2021, 58, 102602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.T.; Hoang, D.T.; Nguyen, D.N.; Niyato, D.; Nguyen, H.T.; Dutkiewicz, E. Proof-of-stake consensus mecha-nisms for future blockchain networks: Fundamentals, applications and opportunities. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 85727–85745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziembowski, S.; Faust, S.; Kolmogorov, V.; Pietrzak, K. Proofs of space. In Proceedings of the Annual Cryptology Conference, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 16–20 August 2015; pp. 585–605. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Hoang, D.T.; Hu, P.; Xiong, Z.; Niyato, D.; Wang, P.; Wen, Y.; Kim, D.I. A Survey on Consensus Mechanisms and Mining Strategy Management in Blockchain Networks. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 22328–22370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuder, M.; Moroz, D.J.; Rao, R.; Parkes, D.C. Low-cost attacks on Ethereum 2.0 by sub-1/3 stakeholders. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.02247. [Google Scholar]

- Buterin, V.; Hernandez, D.; Kamphefner, T.; Pham, K.; Qiao, Z.; Ryan, D.; Zhang, Y.X. Combining GHOST and casper. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.03052. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, M.J. The consensus problem in unreliable distributed systems (a brief survey). In Proceedings of the International Conference on Fundamentals of Computation Theory, Borgholm, Sweden, 21–27 August 1983; pp. 127–140. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamoto, S. United States Sentencing Commission Website, Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System. 2008. Available online: https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/training/annual-national-training-seminar/2018/Emerging_Tech_Bitcoin_Crypto.pdf (accessed on 19 February 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).