Simple Summary

Prostate cancer is one of the most common cancers in men and is characterized by substantial intertumoral heterogeneity, which makes diagnosis and treatment challenging. Conventional tests, such as prostate-specific antigen measurement, do not always reliably identify aggressive disease or predict treatment response. Recent research indicates that epigenetic alterations and tumor-derived material detected in blood or urine can provide more accurate information about tumor biology. This review summarizes current knowledge on epigenetic biomarkers and liquid biopsy approaches, including analyses based on DNA, RNA, and circulating tumor cells. The main intention of this review is to present the current status of various biomarkers and to assess whether they are, or have the potential to be, routinely used in clinical practice based on current data and guidelines. We discuss how these tools may help reduce unnecessary biopsies, improve risk stratification, and support more personalized treatment decisions. Integrating these biomarkers into clinical practice in the future could improve prostate cancer management and patient outcomes; however, many still require further validation and optimization, for example, by combining multiple biomarkers with other clinical data.

Abstract

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most common malignancy in men, characterized by significant genetic and epigenetic heterogeneity, which complicates both diagnosis and treatment processes. Epigenetic mechanisms—including DNA methylation, chromatin remodeling, and dysregulated non-coding RNAs (miRNAs, lncRNAs, circRNAs)—contribute to tumor initiation, progression, and therapy resistance, offering promising diagnostic and prognostic biomarker opportunities. Liquid biopsy technologies, such as circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), circulating tumor cells (CTCs), and exosomes, allow minimally invasive, real-time monitoring of tumor evolution and resistance mechanisms, complementing traditional biomarkers like PSA and supporting precision oncology approaches. Clinically implemented assays, including PCA3, ConfirmMDx, and ExoDx Prostate, along with emerging multi-analyte panels, enhance risk stratification, reduce unnecessary biopsies, and guide therapeutic decisions. Integration of epigenetic and liquid biopsy biomarkers into multimodal diagnostic pathways has the potential to support personalized management of prostate cancer; however, many still require further validation and optimization.

Keywords:

prostate cancer; liquid biopsy; ctDNA; non-coding RNA; biomarkers; precision oncology; epigenetics 1. Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most prevalent malignancy in men, accounting for approximately 20% of all detected tumors worldwide [1]. Increasing evidence indicates that an individual’s genetic profile plays a crucial role in prostate cancer susceptibility and clinical course. Beyond inherited and somatic genetic alterations, epigenetic mechanisms play a central role in prostate cancer initiation, progression, therapeutic resistance, and clonal evolution. Aberrant DNA methylation altered chromatin remodeling, and dysregulated expression of non-coding RNAs, including microRNAs (miRNAs) and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), contribute to tumor plasticity and disease progression [2,3].

Despite substantial advances in molecular characterization, effective clinical management of prostate cancer remains challenging due to pronounced inter- and intratumoral heterogeneity. Prostate tumors are frequently multifocal and multiclonal [2], with genetically distinct subclones coexisting within the same patient. This biological complexity complicates precision oncology, promotes resistance to systemic therapies, and limits the predictive value of currently used biomarkers. Consequently, established diagnostic tools such as prostate-specific antigen (PSA), Prostate Health Index (PHI), Prostate Cancer Antigen 3 (PCA3, also referred to as DD3), and the Prostate-Specific Kallikrein, 4Kscore, while clinically useful, often lack sufficient specificity and may not fully capture disease heterogeneity [4].

To address these limitations, current research increasingly focuses on the development of more precise molecular biomarkers. Promising candidates include nucleic acid-based markers, such as microRNAs (miRNAs), long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), circular RNAs (circRNAs), and DNA-derived signatures, which offer deeper insights into tumor biology. In parallel, liquid biopsy approaches—analyzing circulating tumor-derived biomarkers in blood or urine—have emerged as valuable tools to improve PSA specificity, reduce unnecessary tissue biopsies, and enable dynamic monitoring of tumor evolution over time [5].

Precision oncology in prostate cancer enables treatment individualization and supports ongoing assessment of molecular tumor dynamics through repeated tissue or liquid biopsy sampling [6]. This approach is particularly relevant given the limitations of current therapeutic strategies, including treatment-related toxicity, limited long-term efficacy, and frequent development of resistance. Consequently, several innovative treatment strategies are under investigation, including nanotechnology-based therapies, gene therapy, phytochemicals with anticancer properties, and immunotherapeutic approaches targeting the tumor microenvironment [7].

This review provides a comprehensive overview of emerging diagnostic and therapeutic strategies in prostate cancer, extensively studied in the recent years. Its primary aim is to present the current status of various biomarkers and to assess whether they are, or have the potential to be, routinely implemented in clinical practice based on current data and guidelines. We highlight areas where the evidence supports clinical application, discuss key limitations, and outline future directions to enhance the personalized management of prostate cancer.

2. Materials and Methods

For this narrative review, records were identified through PubMed/MEDLINE (last 15 years, 2011–2025, were screened) using the following search terms: prostate cancer, liquid biopsy, non-coding RNA, miRNA, exosomes, ctDNA, CTC, DNA repair pathways, DNA modification, histone methylation, chromatin remodeling, targeted therapy, and personalized therapy. Records excluded were letters to the editor, editorials, research protocols, case reports, brief correspondence, non-English articles, animal studies, studies involving multiple cancer types, and studies with fewer than 20 patients. Additional records were identified through reference screening of included articles.

Following database searching, a total of 335 records met the initial eligibility criteria and were subjected to a stepwise selection process, including title and abstract screening followed by full-text assessment. During manuscript preparation, an additional three relevant articles were identified and included based on reference tracking and content relevance. Study selection prioritized peer-reviewed journals with established editorial standards and relevance to clinical or translational prostate cancer research. Particular emphasis was placed on studies demonstrating practical or potential clinical applicability, especially those addressing diagnostic, prognostic, or therapeutic implications. Articles of borderline relevance or methodological uncertainty were discussed among members of the research team prior to final inclusion. Ultimately, a total of 134 studies were included in the final narrative synthesis.

3. Epigenetic Biomarkers in Prostate Cancer

Epigenetic alterations play a pivotal role in prostate tumorigenesis and offer promising biomarkers for detection and risk stratification. DNA methylation changes are among the earliest and most stable epigenetic events in PCa. For example, GSTP1 (glutathione S-transferase P1) is hypermethylated and silenced in ~90% of PCa, a hallmark not seen in normal prostate tissue. Hypermethylation of other tumor suppressors (e.g., APC, RASSF1, RARB) is also frequent, and these changes can be detected noninvasively. A study of 514 patients found ≥80% of urine samples from PCa patients harbored methylation of GSTP1, RASSF1 or RARB, highlighting the value of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) methylation in urine [8]. In plasma, emerging assays capture methylated cfDNA to distinguish cancer; for instance, genome-wide cfDNA methylome analysis can differentiate PCa from benign disease and even predict outcomes [8,9].

Clinically, the ConfirmMDx tissue test leverages an epigenetic field effect by PCR-detecting GSTP1, APC, and RASSF1 methylation in histologically negative biopsies [10]. This test, included in NCCN and EAU guidelines, helps identify men at risk of occult cancer after a negative biopsy (sensitivity ~74%, specificity ~60% [11]. Chromatin remodeling and histone modifications are also perturbed in PCa. Overexpression of EZH2 (catalyzing H3K27 trimethylation) and global loss of certain histone marks (e.g., H3K27me3) have been associated with aggressive disease [12]. While histone marks are harder to measure clinically, research shows distinctive patterns (e.g., reduced H3K27me3) correlate with higher Gleason grade and progression [13]. Alterations in chromatin modifiers (e.g., CHD1, ARID1A mutations) further underscore the role of chromatin structure in PCa; these changes may become biomarkers or therapeutic targets as our understanding grows [12]. Table 1 provides a summary of the main methylated genes detected as biomarkers, including their current clinical utility, research versus clinical status, and noted limitations.

Table 1.

Summary of the most promising methylated gene biomarkers.

Another major epigenetic layer involves non-coding RNAs, notably microRNAs and long non-coding RNAs, which regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally. These molecules are dysregulated in PCa and can be detected in tissues and liquid biopsy samples.

3.1. MicroRNAs (miRNAs)

MiRNAs are small non-coding RNAs that regulate gene expression at the post-transcriptional level, thereby directly influencing protein levels in human cells. Due to their regulatory role, miRNAs have been extensively investigated as potential biomarkers in PCa. Numerous studies have demonstrated that specific miRNAs are either upregulated or downregulated in this disorder, and that their expression profiles may correlate with disease progression and therapeutic response.

Importantly, miRNA signatures may complement established diagnostic tools such as PSA testing and prostate volume assessment, particularly in patients classified within the diagnostic “grey zone” [28]. For example, increased expression of miR-145 has been observed in patients who respond favorably to neoadjuvant radiotherapy, defined by a PSA increase of less than 2.0 ng/mL per year [29].

In addition, urinary miRNAs such as miR-148a and miR-375 have been identified as biomarkers for PCa [30]. Their clinical relevance lies in two major aspects: first, they enhance the diagnostic accuracy of PSA testing, and second, they enable more precise clinical decision-making for patients within the grey diagnostic zone.

Several studies have also focused on distinguishing benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) from PCa based on miRNA expression profiles. Analyses revealed significant downregulation of miR-221-5p and miR-708-3p in PCa compared with BPH, suggesting their potential utility as discriminatory biomarkers [31].

Furthermore, differences in miRNA expression have been further reported between metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer (mCRPC) and localized PCa. In this context, 63 miRNAs were found to be upregulated and four downregulated in mCRPC. Notable examples include miR-151-3p, miR-423-3p, miR-126, miR-152, miR-21, and miR-16 [32].

Additional miRNAs, such as miR-205 and miR-214, as well as miR-221 and miR-99b, have shown significant downregulation in PCa patients [33]. However, for some of these miRNAs, a clear correlation with clinical parameters has not yet been established, indicating the need for further research and validation.

Moreover, certain miRNAs have also demonstrated other important clinical features. For instance, miR-200c has been shown to improve the predictive accuracy of the Gleason score, while miR-200b expression is associated with bone metastasis, bilateral tumor involvement, and PSA levels exceeding 10.0 ng/mL [34]. Finally, the entire miR-200 family has been linked to disease progression and overall survival in CRPC [35].

Most miRNA biomarkers are still at the research stage and currently lack sufficient evidence to outperform existing diagnostic approaches. It is unlikely that a single miRNA–based test will be clinically useful on its own; rather, a combined approach integrating multiple miRNAs and other clinical parameters is expected to be more effective. Some preliminary efforts in this direction have already been made. For example, one commercial test analyzes a panel of urinary exosome miRNAs. However, it is not included in mainstream clinical guidelines, and to our information, the manufacturer does not disclose which specific miRNAs are detected by the assay [36].

Beyond their value as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers, miRNAs are also being actively explored as therapeutic agents in prostate cancer. A recent study demonstrated ligand-directed delivery of chemically modified miRNAs selectively to prostate cancer cells, significantly improving cellular uptake, endosomal escape, and functional gene silencing efficacy. Importantly, this approach leveraged small-molecule targeting to enhance tumor specificity, directly addressing key translational barriers such as off-target effects and inefficient intracellular delivery. These findings highlight how biomarker-guided targeting strategies can enable epigenetic modulation at the tumor-cell level, offering a concrete example of how miRNA biology may be translated into clinically actionable precision therapeutics in prostate cancer [37]. Table 2 summarizes the key miRNAs identified as biomarkers, highlighting their clinical relevance, stage of research/clinical implementation, and associated limitations.

Table 2.

Summary of key miRNAs identified as biomarkers.

3.2. Long Non-Coding RNAs (lncRNAs)

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) play key regulatory roles in chromatin remodeling, transcriptional control, and cell signaling, and are increasingly recognized as promising biomarkers in PCa. Recent evidence indicates that the tumor microenvironment itself contributes to lncRNA dysregulation: a comparative analysis of cancer-associated fibroblasts and benign prostatic hyperplasia-derived fibroblasts identified 17 differentially expressed lncRNAs, 15 of which demonstrated potential diagnostic relevance, underscoring the importance of stromal–epithelial interactions in PCa biology [63].

The most clinically established lncRNA is PCA3, which is overexpressed approximately 100-fold in more than 90% of prostate cancers and is virtually undetectable in non-prostatic tissues. PCA3 is secreted into urine and forms the basis of the FDA-approved Progensa PCA3 assay, one of the earliest urine-based molecular diagnostics in oncology [64]. Although PCA3 exhibits only moderate sensitivity as a standalone marker, it provides information independent of PSA and is particularly useful in guiding repeat biopsy decisions in men with prior negative biopsies [65].

Beyond PCA3, several oncogenic lncRNAs have emerged as candidate biomarkers of aggressive disease. SChLAP1, which antagonizes the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex, is overexpressed in approximately 25% of high-grade tumors and is associated with metastasis and poor clinical outcomes [66]. While not yet implemented in routine clinical practice, SChLAP1 and other lncRNAs, including members of the PCAT family and MALAT1, show promise as tissue- or urine-based biomarkers for risk stratification and prognosis [67,68].

More recently, lncRNAs linked to cuproptosis—a copper-dependent form of regulated cell death driven by mitochondrial dysfunction—have been described in PCa. A panel including AC005790.1, AC011472.4, AC099791.2, AC144450.1, LIPE-AS1, and STPG3-AS1 demonstrated both diagnostic and prognostic value, highlighting a novel mechanistic axis with potential translational relevance [69]. Table 3. presents an overview of the main lncRNAs proposed as biomarkers, detailing their clinical significance, whether they are still in research or used clinically, and their limitations.

Table 3.

Main lncRNAs proposed as biomarkers.

4. Circular RNAs (circRNAs)

Circular RNAs (circRNAs) are a relatively recently characterized class of endogenous RNAs generated through back-splicing [81]. In prostate cancer (PCa), aberrant circRNA expression has been consistently reported across primary studies, and a 2022 systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that circRNAs demonstrate moderate overall diagnostic accuracy, supporting their potential as diagnostic biomarkers [81]. Early functional investigations further suggest that specific circRNAs may reflect biological aggressiveness; for example, circSLC39A10 has been shown to promote PCa progression via a miR-936/PROX1/β-catenin (Wnt) signaling axis and has been discussed as a candidate biomarker in this context [82].

CircRNAs, including tumor-associated circRNAs, have also been explored in minimally invasive settings such as serum-based studies in men undergoing prostate biopsy; however, findings to date remain inconsistent, and several proposed circRNA candidates have failed to reliably discriminate prostate cancer from biopsy-negative controls [83]. While tissue-based profiling and liquid biopsy approaches hold promise for the identification of circRNA-based diagnostic and progression biomarkers in PCa, substantial challenges remain. In particular, the field requires standardized analytical assays and large, independent prospective validation cohorts before any circRNA can be considered clinically actionable [81,84].

5. Liquid Biopsy

In the last couple of years, significant progress has been made in the diagnosis and monitoring of patients with PCa. As it became clear that PCa is not a homogeneous disease, the assessment of its molecular characteristics has proven highly beneficial. A variety of molecules have shown clinical utility, including non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), exosomes, and numerous metabolomic biomarkers [85].

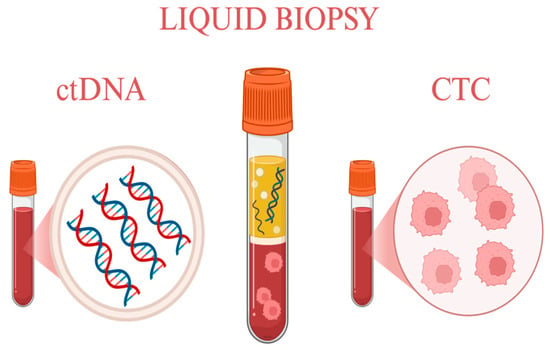

The analysis of these biomarkers has enabled the development of a novel therapeutic approach for men affected by this disease—namely, the evaluation of tumor-derived markers in blood and urine samples through liquid biopsy. This method is particularly valuable for detecting mechanisms of resistance to the most common treatment, androgen receptor inhibitors. PCa frequently progresses to mCRPC, where such an approach offers new therapeutic opportunities [86]. These concepts are illustrated in Figure 1, which provides a schematic overview of the most common liquid biopsy methods used in prostate cancer.

Figure 1.

Most common liquid biopsy methods. Created in https://BioRender.com.

5.1. Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA)

As previously mentioned, liquid biopsy has gained increasing attention in the management of PCa due to its non-invasiveness and its ability to monitor tumor dynamics in real time. One of the most widely implemented approaches is based on circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) analysis [87]. ctDNA enables the assessment of tumor heterogeneity and clonal evolution with greater precision than single-site tissue biopsies or conventional biomarkers such as PSA [88]. This is particularly important given the tendency of PCa to undergo treatment-driven progression [89].

Comprehensive ctDNA profiling provides information on somatic mutations, copy number alterations, and structural rearrangements (e.g., in AR or MYC), as well as disruptions in DNA damage repair genes, including BRCA1/2. Importantly, it also enables the detection of treatment resistance mechanisms. This aspect is of clinical relevance, as ctDNA facilitates the monitoring of resistance to androgen receptor inhibitors, allowing the identification of alterations—such as gene amplifications or activating mutations—that drive therapeutic refractoriness [90,91]. As a result, responders and non-responders can be distinguished early, preventing prolonged use of ineffective therapies and enabling timely adjustment of treatment strategies [92].

In patients with mCRPC, ctDNA has emerged as one of the most important prognostic and predictive biomarkers. It supports the identification of subgroups likely to benefit from PARP inhibitors (e.g., carriers of pathogenic BRCA1/2 variants) and allows for more accurate monitoring of global molecular tumor burden than standard radiologic methods. Notably, patients with ctDNA-positive mCRPC demonstrate worse survival outcomes compared with those who are ctDNA-negative [91].

From a clinical perspective, ctDNA analysis also offers several practical advantages. It may be cost-effective in the long term, reduces reliance on difficult-to-obtain bone tissue (a frequent metastatic site in mCRPC), and generally exhibits higher analyte abundance than circulating tumor cells (CTCs) in early-stage disease [93]. Nevertheless, the two approaches are complementary: certain biomarkers—particularly AR-V7 and some other indicators of resistance to androgen receptor signaling inhibitors—are more reliably detected in CTCs [94] (Table 4).

Table 4.

Biological and Clinical Distinctions Between ctDNA and CTCs.

Several limitations of ctDNA analysis should also be acknowledged. Clonal hematopoiesis may lead to false-positive variant calls; therefore, the use of matched white blood cell DNA or strict adherence to validated protocols is recommended [95]. Additionally, in cases of minimal residual disease or in tumors with predominantly osseous metastases, the circulating tumor fraction may be insufficient for reliable ctDNA detection [96].

In summary, although ctDNA analysis is not without limitations, it represents one of the most powerful and promising tools currently available for precision monitoring and therapeutic guidance in prostate cancer.

5.2. Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs)

As previously mentioned, another liquid biopsy method is based on CTCs. CTCs are FDA-approved predictive biomarkers in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (mHSPC) as well as mCRPC. Their assessment contributes to improved patient management and enhances current prognostic tools.

The CTC count is highly predictive of overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), and 7-month PSA response. It enables patient stratification before therapy selection, as a high CTC count (>5) predicts poorer OS and PFS [97,98,99].

Moreover, CTC levels correlate with both biological and clinical characteristics of the tumor. Higher CTC counts are associated with increased mutational burden and greater genomic complexity [98]. Additionally, CTC counts have been shown to correlate with white blood cell count (WCC) and platelet cloaking [100].

Because CTCs are an important diagnostic tool, but traditional detection methods were limited to identifying only epithelial/EMT-like CTCs (EpCAM-based), newer approaches have been developed. Single-cell and transcriptomic technologies have expanded the detectable range of CTC subtypes and improved their characterization [101,102].

5.3. Extracellular Vesicles and Exosomes

Exosomes are ultrastructural spherical vesicles enclosed by a lipid bilayer and released as part of the cellular secretory pathway. As products of cellular secretion, they carry a diverse molecular cargo, including nucleic acids, proteins, and lipids. Among their protein components, proteasome subunit alpha type-6 (PSM-E) has recently been proposed as a novel potential biomarker [103].

Of particular importance are exosomal nucleic acids, especially microRNAs and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), which show strong potential as novel biomarkers for PCa [104]. In addition to proteins and lipids, exosomes function within a broader liquid biopsy landscape, interacting with and complementing other circulating components such as CTCs in mediating tumor progression and intercellular communication.

By transporting bioactive molecules, exosomes facilitate tumor dissemination and contribute to disease progression, which is particularly relevant in metastatic PCa. Consequently, exosomal profiling—especially when integrated with CTC analysis—can significantly improve the quality of patient care and offers new opportunities for the development of advanced diagnostic and therapeutic strategies [105]. These relationships are illustrated in Figure 2, which depicts exosomes as carriers of miRNAs and other non-coding RNAs and highlights their interplay with CTCs within the liquid biopsy-driven PCa evaluation.

Figure 2.

Important exosome cargo includes miRNAs and other non-coding RNAs. Circulating tumor cells are another key component of liquid biopsy. Created in https://BioRender.com.

Taken together, miRNAs offer a new approach in scenarios where conventional biomarkers and imaging provide insufficient information. An additional insight into tumor aggressiveness, treatment response, and disease progression supports further clinical decisions, including biopsy triage, treatment escalation, and early identification of systemic disease.

6. Critical Technical and Translational Limitations

Despite rapid technological advances and the growing number of proposed epigenetic and liquid biopsy-based biomarkers, their widespread clinical implementation remains constrained. These constraints reflect fundamental biological, analytical, and organizational barriers. Recent high-impact reviews emphasize that these limitations are not solely attributable to insufficient clinical validation. Instead, they reflect intrinsic properties of the biological material, tumor heterogeneity, and current technological constraints of available assays [106,107,108].

6.1. CTCs Are Not Suitable for Screening

CTCs occur at extremely low frequencies in peripheral blood and exhibit short survival times. Their detection depends on sufficiently high tumor burden and active cellular shedding from primary or metastatic lesions. Consequently, CTC-based assays show very limited sensitivity in early-stage disease and are not suitable for population screening or early cancer detection. This has been consistently shown in multiple reviews [106,109]. Their clinical utility is therefore largely restricted to advanced disease, where they serve as prognostic or predictive biomarkers.

6.2. ctDNA: Low Tumor Fraction and Clonal Hematopoiesis Interference

ctDNA typically represents only a small fraction of total circulating cfDNA, particularly in early-stage disease or after curative-intent treatment, substantially limiting analytical sensitivity. An additional major challenge is clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP), whereby somatic mutations originating from hematopoietic cells may be misclassified as tumor-derived alterations. Reviews in NEJM and Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology show that these factors significantly restrict the use of ctDNA for population screening. They also necessitate rigorous biological and bioinformatic controls for accurate interpretation [107,108,110,111].

6.3. miRNA: Hemolysis Sensitivity and Lack of Normalization Consensus

Circulating miRNA analysis is particularly vulnerable to pre-analytical variability. Hemolysis during sample collection or processing releases miRNAs from erythrocytes and platelets, profoundly altering expression profiles. This issue is compounded by the lack of a universally accepted normalization strategy. miR-16, which is frequently used as a reference control, is itself highly sensitive to hemolysis. This limits reproducibility and cross-study comparability [106,112].

6.4. PCA3: Normalization to PSA mRNA Rather than Creatinine

The PCA3 urine test is based on the ratio of PCA3 to PSA mRNA, which enhances prostate specificity but simultaneously renders the result dependent on the amount of prostate-derived RNA and sampling conditions, such as the effectiveness of DRE. The absence of normalization to urinary creatinine means that urine dilution is not directly controlled, potentially affecting inter-patient and inter-center comparability [113,114].

6.5. Tumor Heterogeneity Versus Increasing Analytical Sensitivity

Tumors exhibit pronounced spatial and clonal heterogeneity. Increasing analytical sensitivity, such as with deep NGS, enables the detection of rare variants. However, it also amplifies biological noise and increases the risk of overrepresenting individual subclones, which complicates clinical decision-making [107,111].

6.6. Cost and Complexity of Multimarker Panels

Multimarker genomic and epigenetic panels may partially address tumor heterogeneity but are associated with high costs, complex bioinformatic workflows, and challenges related to clinical validation and reimbursement. Contemporary reviews indicate that, despite promising translational results, scalability and routine clinical use of such panels remain limited [89,108].

6.7. Clinical Bottlenecks: Pre-Analytical Variability, SOPs, and Logistics

A major translational barrier for liquid biopsy implementation is the lack of standardized procedures for sample collection, processing, and storage. Variations in blood collection tubes, time to plasma separation, transport conditions, and freeze–thaw cycles can introduce variability. In some cases, this variability exceeds the biological signal itself. Both Nature-group reviews and NEJM commentaries emphasize that without harmonized SOPs and stringent quality control, liquid biopsy results remain difficult to compare across centers and studies [106,107].

6.8. Perspective of Clinical Guidelines (ESMO, NCCN)

The cautious stance of contemporary clinical guidelines further reflects the technical and biological limitations outlined above. Both the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) acknowledge the potential value of selected molecular assays in specific clinical contexts; however, they do not recommend routine clinical use of liquid biopsy-based biomarkers for population screening or as part of the standard diagnostic pathway for prostate cancer.

These guidelines emphasize that the available evidence is often heterogeneous and frequently derived from retrospective studies or selected cohorts. Moreover, the impact of many molecular assays on hard clinical endpoints, such as cancer-specific survival, remains insufficiently demonstrated. Consequently, ctDNA, CTCs, and RNA—based panels are currently considered primarily within clinical trials, advanced disease monitoring, or selected decision-making scenarios rather than routine clinical use in primary diagnostics [115,116].

The major technical and translational limitations discussed above are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Key technical and translational limitations of epigenetic and liquid biopsy biomarkers in prostate cancer.

7. Practical Clinical Use of Molecular and Epigenetic Biomarkers

Urinary biomarkers have become an important component in the detection and risk stratification of clinically significant prostate cancer (csPC). Among the most studied markers is PCA3, an FDA-approved non-coding RNA assay primarily used to guide repeat biopsy decisions in men with prior negative biopsies. PCA3 offers higher specificity than PSA and is independent of age, prostate volume, or inflammation, though its role in predicting tumor aggressiveness and progression remains limited [52]. Another extensively studied urinary biomarker is the TMPRSS2–ERG gene fusion, absent in benign prostate tissue and detectable in approximately 49% of European men. When combined with PSA testing and PCA3 in commercial assays such as Mi-Prostate Score/MyProstateScore, it significantly improves detection of csPC, particularly in men considered for biopsy or with PI-RADS 3 lesions [120,121,122]. However, the routine use of TMPRSS2–ERG gene fusion as a biomarker remains limited and is primarily research-oriented.

Extracellular vesicle (EV)-based RNA biomarkers, including the European EPI-CE and FDA-approved ExoDx Prostate (EPI) tests, measure exosomal RNA such as ERG, PCA3, and SPDEF to help reduce unnecessary biopsies in patients with PSA levels of 2–10 ng/mL or those with prior negative biopsies [120,123,124]. Unlike MyProstateScore, EPI testing does not require post-digital rectal examination urine collection. Similarly, the SelectMDx test quantifies urinary mRNA levels of DLX1, HOXC6, and KLK3 and integrates these with clinical factors such as PSA, age, and prostate volume to detect high-grade disease (Gleason ≥ 7), improving biopsy decision-making while reducing overdiagnosis [125,126].

Importantly, multiparametric MRI (mpMRI) of the prostate has transformed the biopsy paradigm, often used alongside or after these biomarker tests. For instance, an elevated PHI or 4Kscore may prompt further imaging with mpMRI, whereas a negative MRI and low biomarker score could safely defer biopsy [127,128,129]. Some advanced algorithms, such as the Stockholm3 model, even combine blood biomarkers, genetic single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), and clinical variables to determine the need for MRI or biopsy, enhancing personalized risk assessment [130,131,132].

Collectively, these urinary biomarkers, when combined with mpMRI, may offer a more precise, less invasive approach to prostate cancer diagnosis and risk stratification. They can help reduce unnecessary biopsies, detect high-grade cancers earlier, and complement serum markers such as PSA, PHI, 4Kscore, and Proclarix, supporting a multimodal diagnostic workflow that balances sensitivity, specificity, and cost-effectiveness [127,133,134]. While broader clinical implementation remains limited by availability, cost, and technical complexity, these approaches represent a significant advance toward more personalized, evidence-based prostate cancer management in the future. An overview of commercially available biomarker tests used prior to prostate biopsy for risk stratification and biopsy decision-making is provided in Table 6, whereas available biomarker assays used after prostate cancer diagnosis, including tools for prognostication, treatment selection, and monitoring in advanced disease, are summarized in Table 7.

Table 6.

Commercially available biomarker tests are used before prostate biopsy (risk stratification and biopsy triage).

Table 7.

Commercially available biomarker tests are used after diagnosis and in metastatic disease.

8. Future Research Directions

Future progress in the field of PCa biomarkers will depend on addressing several key challenges. Prospective, multi-center clinical trials are required to validate emerging epigenetic and liquid biopsy biomarkers within clearly defined clinical contexts, rather than relying on retrospective or heterogeneous cohorts. Demonstrating clinical utility, rather than statistical association, will be crucial for guideline adoption.

There is a growing need for integrative biomarker models that combine molecular data with imaging (mpMRI, PSMA PET), clinical parameters, and longitudinal disease monitoring. Single biomarkers are unlikely to fully capture the biological complexity and temporal evolution of PCa. Therefore, multi-analyte panels and algorithm-based approaches are expected to play an increasing role.

Advances in liquid biopsy technologies offer opportunities for real-time monitoring of clonal evolution, minimal residual disease, and early treatment resistance. Improvements in assay sensitivity, correction for clonal hematopoiesis, and harmonization of pre-analytical workflows will be critical for broader clinical implementation.

Emerging areas such as epigenetic therapeutics, exosome-based diagnostics, and AI-driven biomarker integration represent promising avenues for future research. As costs decrease and technologies mature, these approaches may enable more precise risk stratification and adaptive personalized treatment strategies.

9. Conclusions

PCa represents a biologically heterogeneous disease in which traditional biological parameters and PSA are often not sufficient to support optimal clinical decision-making.

Advances in molecular biology and epigenetics have substantially expanded the repertoire of biomarkers capable of capturing tumor heterogeneity, disease aggressiveness, and therapeutic resistance, providing new opportunities for more precise and individualized patient management.

Epigenetic biomarkers, including DNA methylation patterns and non-coding RNA signatures, offer promise due to their early occurrence in tumorigenesis and relative stability across disease stages. Liquid biopsy technologies—encompassing ctDNA, CTCs, and extracellular vesicles—enable minimally invasive, real-time assessment of tumor evolution and resistance mechanisms, addressing key limitations of single-site tissue biopsies. Several assays based on these principles have already reached clinical implementation and guideline acknowledgment, particularly in biopsy triage, post-diagnostic risk stratification, and treatment selection in advanced disease.

The clinical value of these biomarkers is maximized when they are integrated into multimodal diagnostic and therapeutic pathways that combine molecular data with imaging, clinical variables, and longitudinal monitoring. Rather than replacing established tools such as mpMRI or PSA-based assessment, molecular and liquid biopsy biomarkers function as complementary instruments that refine risk stratification and support more informed, adaptive treatment decisions.

Substantial progress has been made, but most emerging biomarkers remain at an early translational stage. Their clinical implementation will require rigorous prospective validation, standardization of analytical workflows, demonstration of clinical utility, and consideration of cost-effectiveness and accessibility.

In summary, the integration of epigenetic and liquid biopsy biomarkers into prostate cancer management represents a critical step toward precision oncology. Continued multidisciplinary research and thoughtful clinical implementation have the potential to transform prostate cancer care by reducing unnecessary interventions, enabling earlier detection of clinically significant disease, and supporting dynamic, biology-driven treatment adaptation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.R., M.M., M.K. and A.K.; methodology, J.R., M.M., M.K. and A.K.; software, A.K.; validation, J.R., M.M. and M.K.; formal analysis J.R. and M.M.; investigation, J.R., M.M., M.K. and A.K.; resources, J.R.; data curation, J.R., M.M., M.K. and A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, J.R., M.M., M.K. and A.K.; writing—review and editing, J.R. and M.M.; visualization, B.P., E.R. and A.N.; supervision, B.P., E.R. and A.N.; project administration, B.P., E.R. and A.N.; funding acquisition, M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Adam Kiljańczyk and Milena Kiljańczyk were employed by the company Read-Gene. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PCa | prostate cancer |

| BPH | benign prostatic hyperplasia |

| MiRNA | microRNA |

| ncRNA | non-coding RNA |

| lncRNA | long non-coding RNA |

| circRNA | circular RNA |

| ctDNA | circulating tumor DNA |

| cfDNA | cell-free DNA |

| CTCs | circulating tumor cells |

| PSA | prostate-specific antigen |

| PHI | prostate health index |

| PCA3/DD3 | prostate cancer antigen 3 |

| EPI | ExoDx prostate |

| mCRPC | metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer |

| mHSPC | metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer |

| OS | overall survival |

| PFS | progression-free survival |

| WCC | white blood cell count |

| csPC | clinically significant PC |

| EV | extracellular vesicle |

| PSM-E | proteasome subunit alpha type-6 |

| mpMRI | multiparametric MRI |

| SNPs | single-nucleotide polymorphisms |

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulac, I.; Roudier, M.P.; Haffner, M.C. Molecular Pathology of Prostate Cancer. Clin. Lab. Med. 2024, 44, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skotheim, R.I.; Bogaard, M.; Carm, K.T.; Axcrona, U.; Axcrona, K. Prostate Cancer: Molecular Aspects, Consequences, and Opportunities of the Multifocal Nature. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA-Rev. Cancer 2024, 1879, 189080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boerrigter, E.; Groen, L.N.; Van Erp, N.P.; Verhaegh, G.W.; Schalken, J.A. Clinical Utility of Emerging Biomarkers in Prostate Cancer Liquid Biopsies. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2020, 20, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzalini, E.; Bonin, S. Molecular Diagnostics of Prostate Cancer: Impact of Molecular Tests. Asian J. Androl. 2024, 26, 562–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlajnic, T.; Bubendorf, L. Molecular Pathology of Prostate Cancer: A Practical Approach. Pathology 2021, 53, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekhoacha, M.; Riet, K.; Motloung, P.; Gumenku, L.; Adegoke, A.; Mashele, S. Prostate Cancer Review: Genetics, Diagnosis, Treatment Options, and Alternative Approaches. Molecules 2022, 27, 5730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramarao-Milne, K.P.; Patch, A.-M.; Nones, K.; Koufariotis, R.; Newell, F.; Addala, V.R.; Kondrashova, O.; Mukhopadhyay, P.; Kazakoff, S.H.; Lakis, V.; et al. Detection of Actionable Variants in Various Cancer Types Reveals Value of Whole-Genome Sequencing over in-Silico Whole-Exome and Hotspot Panel Sequencing. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, vii33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfil, R.D.; Al-Eyd, G. Evolving Insights in Blood-Based Liquid Biopsies for Prostate Cancer Interrogation. Oncoscience 2023, 10, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Neste, L.; Bigley, J.; Toll, A.; Otto, G.; Clark, J.; Delrée, P.; Van Criekinge, W.; Epstein, J.I. A Tissue Biopsy-Based Epigenetic Multiplex PCR Assay for Prostate Cancer Detection. BMC Urol. 2012, 12, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matuszczak, M.; Schalken, J.A.; Salagierski, M. Prostate Cancer Liquid Biopsy Biomarkers’ Clinical Utility in Diagnosis and Prognosis. Cancers 2021, 13, 3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlibasa, L.; Nicu, A.-T.; Chifiriuc, M.C.; Medar, C.; Petrescu, A.; Jinga, V.; Stoica, I. H3 Histone Methylation Landscape in Male Urogenital Cancers: From Molecular Mechanisms to Epigenetic Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1181764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.; Shekhar, H.; Sahu, A.; Kaur, D.; Haque, S.; Tuli, H.S.; Sharma, H.; Sharma, U. Epigenetic Insights into Prostate Cancer: Exploring Histone Modifications and Their Therapeutic Implications. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1570193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafikova, G.; Gilyazova, I.; Enikeeva, K.; Pavlov, V.; Kzhyshkowska, J. Prostate Cancer: Genetics, Epigenetics and the Need for Immunological Biomarkers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kral, M.; Kurfurstova, D.; Zemla, P.; Elias, M.; Bouchal, J. New Biomarkers and Multiplex Tests for Diagnosis of Aggressive Prostate Cancer and Therapy Management. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1542511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Wu, M.; He, L.; Chen, P.; Liu, H.; Yang, H. Glutathione-S-Transferase p1 Gene Promoter Methylation in Cell-Free DNA as a Diagnostic and Prognostic Tool for Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2023, 2023, 7279243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachem, S.; Yehya, A.; El Masri, J.; Mavingire, N.; Johnson, J.R.; Dwead, A.M.; Kattour, N.; Bouchi, Y.; Kobeissy, F.; Rais-Bahrami, S.; et al. Contemporary Update on Clinical and Experimental Prostate Cancer Biomarkers: A Multi-Omics-Focused Approach to Detection and Risk Stratification. Biology 2024, 13, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santiago, I.; Rivas, J.G. Re: EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-ISUP-SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2026, 89, 100–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NCCN. Prostate Cancer Early Detection NCCN 1.2026 Guidelines; NCCN: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Visser, W.; de Jong, H.; Melchers, W.; Mulders, P.; Schalken, J. Commercialized Blood-, Urinary- and Tissue-Based Biomarker Tests for Prostate Cancer Diagnosis and Prognosis. Cancers 2020, 12, 3790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Chen, J.; Zhang, B.; Chen, X.; Huang, B.; Zhuang, J.; Mo, C.; Qiu, S. Association between RASSF1A Promoter Methylation and Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e75283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, T.; Diao, Y.; Zeng, X.; Zhou, L.; Wu, G.; Liu, J.; Hao, X. Influential Factors on Urine EV DNA Methylation Detection and Its Diagnostic Potential in Prostate Cancer. Front. Genet. 2024, 15, 1338468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessels, D.; Schalken, J.A. Urinary Biomarkers for Prostate Cancer: A Review. Asian J. Androl. 2013, 15, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakavicius, A.; Daniunaite, K.; Zukauskaite, K.; Barisiene, M.; Jarmalaite, S.; Jankevicius, F. Urinary DNA Methylation Biomarkers for Prediction of Prostate Cancer Upgrading and Upstaging. Clin. Epigenetics 2019, 11, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedemann, M.; Horn, F.; Gutewort, K.; Tautz, L.; Jandeck, C.; Bechmann, N.; Sukocheva, O.; Wirth, M.P.; Fuessel, S.; Menschikowski, M. Increased Sensitivity of Detection of RASSF1A and GSTP1 DNA Fragments in Serum of Prostate Cancer Patients: Optimisation of Diagnostics Using OBBPA-DdPCR. Cancers 2021, 13, 4459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, M.; Zhou, X.; Fan, Z.; Ding, X.; Li, L.; Wang, S.; Xue, W.; Wang, H.; Suo, Z.; Deng, X. Clinical Significance of Retinoic Acid Receptor Beta Promoter Methylation in Prostate Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 45, 2497–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; He, B.; Pan, Y.; Li, R.; Xu, Y.; Chen, L.; Nie, Z.; Gu, L.; Wang, S. The Association of Retinoic Acid Receptor Beta2(RARβ2) Methylation Status and Prostate Cancer Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e62950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, J.; Zhao, L.; Wang, F.; Ji, J.; Cao, Z.; Xu, H.; Shi, X.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Guo, F.; et al. Discovery and Validation of Serum MicroRNAs as Early Diagnostic Biomarkers for Prostate Cancer in Chinese Population. Biomed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 9306803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, P.; Zhang, T.; He, D.; Hsieh, J.-T. MicroRNA-145 Modulates Tumor Sensitivity to Radiation in Prostate Cancer. Radiat. Res. 2015, 184, 630–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuopelyte, K.; Daniunaite, K.; Bakavicius, A.; Lazutka, J.R.; Jankevicius, F.; Jarmalaite, S. The Utility of Urine-Circulating MiRNAs for Detection of Prostate Cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2016, 115, 707–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leidinger, P.; Hart, M.; Backes, C.; Rheinheimer, S.; Keck, B.; Wullich, B.; Keller, A.; Meese, E. Differential Blood-Based Diagnosis between Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia and Prostate Cancer: MiRNA as Source for Biomarkers Independent of PSA Level, Gleason Score, or TNM Status. Tumor Biol. 2016, 37, 10177–10185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watahiki, A.; Macfarlane, R.; Gleave, M.; Crea, F.; Wang, Y.; Helgason, C.; Chi, K. Plasma MiRNAs as Biomarkers to Identify Patients with Castration-Resistant Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 7757–7770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Goldberger, H.; Dimtchev, A.; Ramalinga, M.; Chijioke, J.; Marian, C.; Oermann, E.K.; Uhm, S.; Kim, J.S.; Chen, L.N.; et al. MicroRNA Profiling in Prostate Cancer—The Diagnostic Potential of Urinary MiR-205 and MiR-214. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, M.F.; Kuasne, H.; Barros-Filho, M.d.C.; Cilião, H.L.; Marchi, F.A.; Fuganti, P.E.; Paschoal, A.R.; Rogatto, S.R.; Cólus, I.M.d.S. Circulating MRNAs and MiRNAs as Candidate Markers for the Diagnosis and Prognosis of Prostate Cancer. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-M.; Mahon, K.L.; Spielman, C.; Gurney, H.; Mallesara, G.; Stockler, M.R.; Bastick, P.; Briscoe, K.; Marx, G.; Swarbrick, A.; et al. Phase 2 Study of Circulating MicroRNA Biomarkers in Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2017, 116, 1002–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.-L.W.; Sorokin, I.; Aleksic, I.; Fisher, H.; Kaufman, R.P.; Winer, A.; McNeill, B.; Gupta, R.; Tilki, D.; Fleshner, N.; et al. Expression of Small Noncoding RNAs in Urinary Exosomes Classifies Prostate Cancer into Indolent and Aggressive Disease. J. Urol. 2020, 204, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelaal, A.M.; Sohal, I.S.; Iyer, S.G.; Sudarshan, K.; Orellana, E.A.; Ozcan, K.E.; dos Santos, A.P.; Low, P.S.; Kasinski, A.L. Selective Targeting of Chemically Modified MiR-34a to Prostate Cancer Using a Small Molecule Ligand and an Endosomal Escape Agent. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2024, 35, 102193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avgeris, M.; Stravodimos, K.; Fragoulis, E.G.; Scorilas, A. The Loss of the Tumour-Suppressor MiR-145 Results in the Shorter Disease-Free Survival of Prostate Cancer Patients. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 108, 2573–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, J. Prognostic Role of MicroRNA-145 in Prostate Cancer: A Systems Review and Meta-Analysis. Prostate Int. 2015, 3, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Qin, S.; An, T.; Tang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zheng, L. MiR-145 Detection in Urinary Extracellular Vesicles Increase Diagnostic Efficiency of Prostate Cancer Based on Hydrostatic Filtration Dialysis Method. Prostate 2017, 77, 1167–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghoubi, S.M.; Zare, E.; Jafari Dargahlou, S.; Jafari, M.; Azimi, M.; Khoshnazar, M.; Shirjang, S.; Mansoori, B. MicroRNAs in Prostate Cancer Liquid Biopsies: Early Detection, Prognosis, and Treatment Monitoring. Cells 2026, 15, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osiecki, R.; Popławski, P.; Sys, D.; Bogusławska, J.; Białas, A.; Zawadzki, M.; Piekiełko-Witkowska, A.; Dobruch, J. CIRCULATING MiR-1-3p, MiR-96-5p, MiR-148a-3p, and MiR-375-3p Support Differentiation Between Prostate Cancer and Benign Prostate Lesions. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2025, 23, 102294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramovic, I.; Vrhovec, B.; Skara, L.; Vrtaric, A.; Nikolac Gabaj, N.; Kulis, T.; Stimac, G.; Ljiljak, D.; Ruzic, B.; Kastelan, Z.; et al. MiR-182-5p and MiR-375-3p Have Higher Performance Than PSA in Discriminating Prostate Cancer from Benign Prostate Hyperplasia. Cancers 2021, 13, 2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa-Pinheiro, P.; Ramalho-Carvalho, J.; Vieira, F.Q.; Torres-Ferreira, J.; Oliveira, J.; Gonçalves, C.S.; Costa, B.M.; Henrique, R.; Jerónimo, C. MicroRNA-375 Plays a Dual Role in Prostate Carcinogenesis. Clin. Epigenetics 2015, 7, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Yuan, T.; Liang, M.; Du, M.; Xia, S.; Dittmar, R.; Wang, D.; See, W.; Costello, B.A.; Quevedo, F.; et al. Exosomal MiR-1290 and MiR-375 as Prognostic Markers in Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2015, 67, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casanova-Salas, I.; Rubio-Briones, J.; Calatrava, A.; Mancarella, C.; Masiá, E.; Casanova, J.; Fernández-Serra, A.; Rubio, L.; Ramírez-Backhaus, M.; Armiñán, A.; et al. Identification of MiR-187 and MiR-182 as Biomarkers of Early Diagnosis and Prognosis in Patients with Prostate Cancer Treated with Radical Prostatectomy. J. Urol. 2014, 192, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Pathak, A.K.; Kural, S.; Kumar, L.; Bhardwaj, M.G.; Yadav, M.; Trivedi, S.; Das, P.; Gupta, M.; Jain, G. Integrating MiRNA Profiling and Machine Learning for Improved Prostate Cancer Diagnosis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 30477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Wang, Y.; Jia, J.; Mao, X.; Stankiewicz, E.; Scandura, G.; Burke, E.; Xu, L.; Marzec, J.; Davies, C.R.; et al. The Identification of Plasma Exosomal MiR-423-3p as a Potential Predictive Biomarker for Prostate Cancer Castration-Resistance Development by Plasma Exosomal MiRNA Sequencing. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 8, 602493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SONG, L.; XIE, X.; YU, S.; PENG, F.; PENG, L. MicroRNA-126 Inhibits Proliferation and Metastasis by Targeting Pik3r2 in Prostate Cancer. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 13, 1204–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Hu, C.; Ma, Z.; Huang, Y.; Shelley, G.; Kuczler, M.D.; Kim, C.-J.; Witwer, K.W.; Keller, E.T.; Amend, S.R.; et al. Urinary Extracellular Vesicle-Derived MiR-126-3p Predicts Lymph Node Invasion in Patients with High-Risk Prostate Cancer. Med. Oncol. 2024, 41, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, L.; Meijer, J.; Schubert, S.; Matin, F.; Batra, J. Assessment of MiR-98-5p, MiR-152-3p, MiR-326 and MiR-4289 Expression as Biomarker for Prostate Cancer Diagnosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matin, F.; Jeet, V.; Moya, L.; Selth, L.A.; Chambers, S.; Yeadon, T.; Saunders, P.; Eckert, A.; Heathcote, P.; Wood, G.; et al. A Plasma Biomarker Panel of Four MicroRNAs for the Diagnosis of Prostate Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 6653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joković, S.M.; Dobrijević, Z.; Kotarac, N.; Filipović, L.; Popović, M.; Korać, A.; Vuković, I.; Savić-Pavićević, D.; Brajušković, G. MiR-375 and MiR-21 as Potential Biomarkers of Prostate Cancer: Comparison of Matching Samples of Plasma and Exosomes. Genes 2022, 13, 2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Park, Y.H.; Jung, S.-H.; Jang, S.-H.; Kim, M.Y.; Lee, J.Y.; Chung, Y. Urinary Exosome MicroRNA Signatures as a Noninvasive Prognostic Biomarker for Prostate Cancer. NPJ Genom. Med. 2021, 6, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.T.; Kim, W.-J. MicroRNAs in Prostate Cancer. Prostate Int. 2013, 1, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Li, Q.; Feng, N.-H.; Cheng, G.; Guan, Z.-L.; Wang, Y.; Qin, C.; Yin, C.-J.; Hua, L.-X. MiR-205 Is Frequently Downregulated in Prostate Cancer and Acts as a Tumor Suppressor by Inhibiting Tumor Growth. Asian J. Androl. 2013, 15, 735–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, S.; Valbuena, G.N.; Curry, E.; Bevan, C.L.; Keun, H.C. MicroRNAs as Biomarkers for Prostate Cancer Prognosis: A Systematic Review and a Systematic Reanalysis of Public Data. Br. J. Cancer 2022, 126, 502–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foj, L.; Ferrer, F.; Serra, M.; Arévalo, A.; Gavagnach, M.; Giménez, N.; Filella, X. Exosomal and Non-Exosomal Urinary MiRNAs in Prostate Cancer Detection and Prognosis. Prostate 2017, 77, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, N.H.; Abdellateif, M.S.; Kassem, S.H.; Abd El Salam, M.A.; El Gammal, M.M. Diagnostic Significance of MiR-21, MiR-141, MiR-18a and MiR-221 as Novel Biomarkers in Prostate Cancer among Egyptian Patients. Andrologia 2019, 51, e13384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.Y.; Shin, H.; Moon, H.W.; Park, Y.H.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y. Urinary Exosomal MicroRNA Profiling in Intermediate-Risk Prostate Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waseem, M.; Gujrati, H.; Wang, B.-D. Tumor Suppressive MiR-99b-5p as an Epigenomic Regulator Mediating MTOR/AR/SMARCD1 Signaling Axis in Aggressive Prostate Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1184186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danarto, R.; Astuti, I.; Umbas, R.; Haryana, S.M. Urine MiR-21-5p and MiR-200c-3p as Potential Non-Invasive Biomarkers in Patients with Prostate Cancer. Türk Urol. Derg./Turk. J. Urol. 2020, 46, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abikar, A.; Mustafa, M.M.S.; Athalye, R.R.; Nadig, N.; Tamboli, N.; Babu, V.; Keshavamurthy, R.; Ranganathan, P. Comparative Transcriptome of Normal and Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos, A.E.G.; Matos, A.d.R.; Ferreira, L.B.; Gimba, E.R.P. The Long Non-Coding RNA PCA3: An Update of Its Functions and Clinical Applications as a Biomarker in Prostate Cancer. Oncotarget 2019, 10, 6589–6603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidaway, P. Urinary PCA3 and TMPRSS2:ERG Reduce the Need for Repeat Biopsy. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2015, 12, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, M.; Kadam, R.N.; Charania, Z.S.; Somarowthu, S. LncRNA SChLAP1 Promotes Cancer Cell Proliferation and Invasion Via Its Distinct Structural Domains and Conserved Regions. J. Mol. Biol. 2025, 437, 169350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Chen, S.; Wu, C.; Urabe, F.; Heidegger, I.; Campobasso, D.; Huang, H.; Li, P. SChLAP1 Regulates the Metastasis and Apoptosis of Prostate Cancer Partly via MiR-101. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2025, 14, 1782–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, C.; Wang, I.; Li, X.; Xia, R.; Deng, F. Long Non-Coding RNA in Prostate Cancer. Am. J. Clin. Exp. Urol. 2022, 10, 170–179. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, X.; Zeng, Z.; Yang, H.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, G. Novel Cuproptosis-Related Long Non-Coding RNA Signature to Predict Prognosis in Prostate Carcinoma. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gittelman, M.C.; Hertzman, B.; Bailen, J.; Williams, T.; Koziol, I.; Henderson, R.J.; Efros, M.; Bidair, M.; Ward, J.F. PCA3 Molecular Urine Test as a Predictor of Repeat Prostate Biopsy Outcome in Men with Previous Negative Biopsies: A Prospective Multicenter Clinical Study. J. Urol. 2013, 190, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Cao, W.; Li, Q.; Shen, H.; Liu, C.; Deng, J.; Xu, J.; Shao, Q. Evaluation of Prostate Cancer Antigen 3 for Detecting Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prensner, J.R.; Zhao, S.; Erho, N.; Schipper, M.; Iyer, M.K.; Dhanasekaran, S.M.; Magi-Galluzzi, C.; Mehra, R.; Sahu, A.; Siddiqui, J.; et al. RNA Biomarkers Associated with Metastatic Progression in Prostate Cancer: A Multi-Institutional High-Throughput Analysis of SChLAP1. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, 1469–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehra, R.; Udager, A.M.; Ahearn, T.U.; Cao, X.; Feng, F.Y.; Loda, M.; Petimar, J.S.; Kantoff, P.; Mucci, L.A.; Chinnaiyan, A.M. Overexpression of the Long Non-Coding RNA SChLAP1 Independently Predicts Lethal Prostate Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2016, 70, 549–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Liu, J.; Xu, Z.; Ye, M.; Li, J. LncRNA PCAT14 Is a Diagnostic Marker for Prostate Cancer and Is Associated with Immune Cell Infiltration. Dis. Markers 2021, 2021, 9494619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stella, M.; Russo, G.I.; Leonardi, R.; Carcò, D.; Gattuso, G.; Falzone, L.; Ferrara, C.; Caponnetto, A.; Battaglia, R.; Libra, M.; et al. Extracellular RNAs from Whole Urine to Distinguish Prostate Cancer from Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, J.; Tang, J.; Wang, G.; Zhu, Y.-S. Long Non-Coding RNA as Potential Biomarker for Prostate Cancer: Is It Making a Difference? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prensner, J.R.; Iyer, M.K.; Balbin, O.A.; Dhanasekaran, S.M.; Cao, Q.; Brenner, J.C.; Laxman, B.; Asangani, I.A.; Grasso, C.S.; Kominsky, H.D.; et al. Transcriptome Sequencing across a Prostate Cancer Cohort Identifies PCAT-1, an Unannotated LincRNA Implicated in Disease Progression. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 742–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Ji, J.; Lyu, J.; Jin, X.; He, X.; Mo, S.; Xu, H.; He, J.; Cao, Z.; Chen, X.; et al. A Novel Urine Exosomal LncRNA Assay to Improve the Detection of Prostate Cancer at Initial Biopsy: A Retrospective Multicenter Diagnostic Feasibility Study. Cancers 2021, 13, 4075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badowski, C.; He, B.; Garmire, L.X. Blood-Derived LncRNAs as Biomarkers for Cancer Diagnosis: The Good, the Bad and the Beauty. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 2022, 6, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Li, W.; Weng, Y.; Hua, B.; Gu, X.; Lu, C.; Xu, B.; Xu, H.; Wang, Z. METTL3-Mediated m 6 A Modification of LncRNA MALAT1 Facilitates Prostate Cancer Growth by Activation of PI3K/AKT Signaling. Cell Transplant. 2022, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Jiang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Jin, X.R.; Li, B.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Liu, J. Prognostic and Diagnostic Value of CircRNA Expression in Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 945143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Pan, X.; Zhang, S.; Xu, M.; Chen, X.; Pei, F.; Wu, M.; Meng, F.; Sun, B.; Zhang, M.; et al. Circular RNA CircSLC39A10 Promotes Prostate Cancer Progression by Activating Wnt Signaling via the MiR-936/PROX1/β-Catenin Axis. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2025, 30, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samirae, L.; Krausewitz, P.; Alajati, A.; Kristiansen, G.; Ritter, M.; Ellinger, J. The Relevance of CircRNAs in Serum of Patients Undergoing Prostate Biopsy. Int. J. Urol. 2024, 31, 578–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, D.; Zheng, W.; Zhang, D.-H.; Dong, X. Circular RNA and Its Potential as Prostate Cancer Biomarkers. World J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 11, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahdal, M.; Perera, R.A.; Moschovas, M.C.; Patel, V.; Perera, R.J. Current Advances of Liquid Biopsies in Prostate Cancer: Molecular Biomarkers. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 2023, 30, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giunta, E.F.; Annaratone, L.; Bollito, E.; Porpiglia, F.; Cereda, M.; Banna, G.L.; Mosca, A.; Marchiò, C.; Rescigno, P. Molecular Characterization of Prostate Cancers in the Precision Medicine Era. Cancers 2021, 13, 4771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakari, S.; Niels, N.K.; Olagunju, G.V.; Nnaji, P.C.; Ogunniyi, O.; Tebamifor, M.; Israel, E.N.; Atawodi, S.E.; Ogunlana, O.O. Emerging Biomarkers for Non-Invasive Diagnosis and Treatment of Cancer: A Systematic Review. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1405267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeney, C.J.; Petry, R.; Xu, C.; Childress, M.; He, J.; Fabrizio, D.; Gjoerup, O.; Morley, S.; Catlett, T.; Assaf, Z.J.; et al. Circulating Tumor DNA Assessment for Treatment Monitoring Adds Value to PSA in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 4115–4122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopytov, S.A.; Sagitova, G.R.; Guschin, D.Y.; Egorova, V.S.; Zvyagin, A.V.; Rzhevskiy, A.S. Circulating Tumor DNA in Prostate Cancer: A Dual Perspective on Early Detection and Advanced Disease Management. Cancers 2025, 17, 2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slootbeek, P.H.J.; Tolmeijer, S.H.; Mehra, N.; Schalken, J.A. Therapeutic Biomarkers in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: Does the State Matter? Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2024, 61, 178–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, E.M.; Ng, S.W.S.; Tolmeijer, S.H.; Emmett, L.; Sandhu, S.; Buteau, J.P.; Iravani, A.; Joshua, A.M.; Francis, R.J.; Subhash, V.; et al. Lutetium-177–PSMA-617 or Cabazitaxel in Metastatic Prostate Cancer: Circulating Tumor DNA Analysis of the Randomized Phase 2 TheraP Trial. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 2722–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyatt, A.W.; Litiere, S.; Bidard, F.-C.; Cabel, L.; Dyrskjøt, L.; Karlovich, C.A.; Pantel, K.; Petrie, J.; Philip, R.; Andrews, H.S.; et al. Plasma CtDNA as a Treatment Response Biomarker in Metastatic Cancers: Evaluation by the RECIST Working Group. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 5034–5041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidrich, I.; Ačkar, L.; Mossahebi Mohammadi, P.; Pantel, K. Liquid Biopsies: Potential and Challenges. Int. J. Cancer 2021, 148, 528–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofoli, M.; Maiorano, B.A.; Bruno, G.; Giordano, G.; Falagario, U.G.; Necchi, A.; Carrieri, G.; Landriscina, M.; Conteduca, V. Circulating Tumor DNA: A New Research Frontier in Urological Oncology from Localized to Metastatic Disease. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2025, 8, 805–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonarakis, E.S.; Kuang, Z.; Tukachinsky, H.; Parachoniak, C.; Kelly, A.D.; Gjoerup, O.; Aiyer, A.; Severson, E.A.; Pavlick, D.C.; Frampton, G.M.; et al. Prevalence of Inferred Clonal Hematopoiesis (CH) Detected on Comprehensive Genomic Profiling (CGP) of Solid Tumor Tissue or Circulating Tumor DNA (CtDNA). J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herberts, C.; Wyatt, A.W. Technical and Biological Constraints on CtDNA-Based Genotyping. Trends Cancer 2021, 7, 995–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldkorn, A.; Tangen, C.; Plets, M.; Bsteh, D.; Xu, T.; Pinski, J.K.; Ingles, S.; Triche, T.J.; MacVicar, G.R.; Vaena, D.A.; et al. Circulating Tumor Cell Count and Overall Survival in Patients with Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2437871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swami, U.; Sayegh, N.; Jo, Y.; Haaland, B.; McFarland, T.R.; Nussenzveig, R.H.; Goel, D.; Sirohi, D.; Hahn, A.W.; Maughan, B.L.; et al. External Validation of Association of Baseline Circulating Tumor Cell Counts with Survival Outcomes in Men with Metastatic Castration-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2022, 21, 1857–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldkorn, A.; Tangen, C.; Plets, M.; Morrison, G.J.; Cunha, A.; Xu, T.; Pinski, J.K.; Ingles, S.A.; Triche, T.; Harzstark, A.L.; et al. Baseline Circulating Tumor Cell Count as a Prognostic Marker of PSA Response and Disease Progression in Metastatic Castrate-Sensitive Prostate Cancer (SWOG S1216). Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 1967–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brady, L.; Hayes, B.; Sheill, G.; Baird, A.-M.; Guinan, E.; Stanfill, B.; Vlajnic, T.; Casey, O.; Murphy, V.; Greene, J.; et al. Platelet Cloaking of Circulating Tumour Cells in Patients with Metastatic Prostate Cancer: Results from ExPeCT, a Randomised Controlled Trial. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0243928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Ghali, N.E.; Giannakakou, P. Advances in Metastatic Prostate Cancer Circulating Tumor Cell Enrichment Technologies and Clinical Studies. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2025, 392, 151–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.; Zhu, H.; Ma, X. Liquid Biopsy of Circulating Tumor Cells: From Isolation, Enrichment, and Genome Sequencing to Clinical Applications. Histol. Histopathol. 2025, 40, 1529–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, X.; Niu, R.; Tan, Y.; Huang, Y.; Ren, W.; Zhou, W.; Wu, H.; Zhang, J.; Xu, M.; Zhou, X.; et al. Exosomal PSM-E Inhibits Macrophage M2 Polarization to Suppress Prostate Cancer Metastasis through the RACK1 Signaling Axis. Biomark. Res. 2024, 12, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Wang, J.; Luo, H.; Wang, Y.; Cai, X.; Zhang, T.; Liao, Y.; Wang, D. Role of Exosomes in Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1498733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Yu, C.; Jiang, K.; Yang, G.; Yang, S.; Tan, S.; Li, T.; Liang, H.; He, Q.; Wei, F.; et al. Unveiling Potential: Urinary Exosomal MRNAs as Non-Invasive Biomarkers for Early Prostate Cancer Diagnosis. BMC Urol. 2024, 24, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Guo, H.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, C.; Bu, J.; Sun, T.; Wei, J. Liquid Biopsy in Cancer Current: Status, Challenges and Future Prospects. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.C.M.; Sasieni, P.; Rosenfeld, N. Promises and Pitfalls of Multi-Cancer Early Detection Using Liquid Biopsy Tests. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 22, 566–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parums, D.V. A Review of Circulating Tumor DNA (CtDNA) and the Liquid Biopsy in Cancer Diagnosis, Screening, and Monitoring Treatment Response. Med Sci. Monit. 2025, 31, e949300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alix-Panabières, C.; Pantel, K. Challenges in Circulating Tumour Cell Research. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, S.; Fontanillas, P.; Flannick, J.; Manning, A.; Grauman, P.V.; Mar, B.G.; Lindsley, R.C.; Mermel, C.H.; Burtt, N.; Chavez, A.; et al. Age-Related Clonal Hematopoiesis Associated with Adverse Outcomes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 2488–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tie, J.; Cohen, J.D.; Lahouel, K.; Lo, S.N.; Wang, Y.; Kosmider, S.; Wong, R.; Shapiro, J.; Lee, M.; Harris, S.; et al. Circulating Tumor DNA Analysis Guiding Adjuvant Therapy in Stage II Colon Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 2261–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschner, M.B.; Kao, S.C.; Edelman, J.J.; Armstrong, N.J.; Vallely, M.P.; van Zandwijk, N.; Reid, G. Haemolysis during Sample Preparation Alters MicroRNA Content of Plasma. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e24145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, L.S.; Fradet, Y.; Lim Deras, I.; Blase, A.; Mathis, J.; Aubin, S.M.J.; Cancio, A.T.; Desaulniers, M.; Ellis, W.J.; Rittenhouse, H.; et al. PCA3 Molecular Urine Assay for Prostate Cancer in Men Undergoing Repeat Biopsy. Urology 2007, 69, 532–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlaeminck-Guillem, V.; Devonec, M.; Colombel, M.; Rodriguez-Lafrasse, C.; Decaussin-Petrucci, M.; Ruffion, A. Urinary PCA3 Score Predicts Prostate Cancer Multifocality. J. Urol. 2011, 185, 1234–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiraishi, Y.; Sekino, Y.; Horinouchi, H.; Ohe, Y.; Okamoto, I. High Incidence of Cytokine Release Syndrome in Patients with Advanced NSCLC Treated with Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab. Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, 1064–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, E.M.; Srinivas, S.; Adra, N.; An, Y.; Bitting, R.; Chapin, B.; Cheng, H.H.; D’Amico, A.V.; Desai, N.; Dorff, T.; et al. Prostate Cancer, Version 3.2024. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2024, 22, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciracì, P.; Studiale, V.; Taravella, A.; Antoniotti, C.; Cremolini, C. Late-Line Options for Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Review and Evidence-Based Algorithm. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 22, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellenthal, N.J.; Eandi, J.A.; DeLair, S.M.; DiGrande, A.; Stone, A.R. Umbilical Stomal Stenosis: A Simple Surgical Revision Technique. Urology 2007, 69, 771–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, D.; Hennenlotter, J.; Sotlar, K.; Kuehs, U.; Senger, E.; Nagele, U.; Boekeler, U.; Ulmer, A.; Stenzl, A. Quantification of Tumor Cell Burden by Analysis of Single Cell Lymph Node Disaggregates in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Prostate 2010, 70, 1110–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, M.; Leow, J.J.; Nordström, T.; Mortezavi, A.; Albers, P.; Heer, R.; Rajan, P. Emerging Tools for the Early Detection of Prostate Cancer. BJUI Compass 2025, 6, e70081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlins, S.A.; Day, J.R.; Lonigro, R.J.; Hovelson, D.H.; Siddiqui, J.; Kunju, L.P.; Dunn, R.L.; Meyer, S.; Hodge, P.; Groskopf, J.; et al. Urine TMPRSS2:ERG Plus PCA3 for Individualized Prostate Cancer Risk Assessment. Eur. Urol. 2016, 70, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosoian, J.J.; Singhal, U.; Davenport, M.S.; Wei, J.T.; Montgomery, J.S.; George, A.K.; Salami, S.S.; Mukundi, S.G.; Siddiqui, J.; Kunju, L.P.; et al. Urinary MyProstateScore (MPS) to Rule out Clinically-Significant Cancer in Men with Equivocal (PI-RADS 3) Multiparametric MRI: Addressing an Unmet Clinical Need. Urology 2022, 164, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, H.S.; Lee, S.S.; Barocas, D.A.; Tosoian, J.J. Evaluation of Blood and Urine Based Biomarkers for Detection of Clinically-Significant Prostate Cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2025, 28, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majewska, Z.; Zajkowska, M.; Pączek, S.; Nowiński, A.R.; Sokólska, W.; Gryko, M.; Orywal, K. The Clinical Relevance of Tumor Biomarkers in Prostate Cancer—A Review. Cancers 2025, 17, 3742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amparore, D.; De Cillis, S.; Zamengo, D.; Ortenzi, M.; Alladio, E.; Di Nardo, F.; Serra, T.; Occhipinti, S.; Fiori, C.; Porpiglia, F. A Rapid Urinary Test for Combining PSA and Zinc to Enhance Prostate Cancer Diagnosis: Results from a Prospective Study. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Wu, Y.; He, P.; Liang, J.; Xu, X.; Ji, C. A Meta-Analysis for the Diagnostic Accuracy of SelectMDx in Prostate Cancer. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0285745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AM, S.K.; Rajan, P.; Alkhamees, M.; Holley, M.; Lakshmanan, V.-K. Prostate Cancer Theragnostics Biomarkers: An Update. Investig. Clin. Urol. 2024, 65, 527–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, M.; De Cobelli, O.; Lucarelli, G.; Porreca, A.; Busetto, G.M.; Cantiello, F.; Damiano, R.; Autorino, R.; Musi, G.; Vartolomei, M.D.; et al. Beyond PSA: The Role of Prostate Health Index (Phi). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, G.I.; Regis, F.; Castelli, T.; Favilla, V.; Privitera, S.; Giardina, R.; Cimino, S.; Morgia, G. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Diagnostic Accuracy of Prostate Health Index and 4-Kallikrein Panel Score in Predicting Overall and High-Grade Prostate Cancer. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2017, 15, 429–439.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbetuyi-Tayo, P.; Gbadebo, M.; Rotimi, O.A.; Rotimi, S.O. Advancements in Biomarkers of Prostate Cancer: A Review. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2024, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönberg, H.; Adolfsson, J.; Aly, M.; Nordström, T.; Wiklund, P.; Brandberg, Y.; Thompson, J.; Wiklund, F.; Lindberg, J.; Clements, M.; et al. Prostate Cancer Screening in Men Aged 50–69 Years (STHLM3): A Prospective Population-Based Diagnostic Study. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 1667–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-Y.; Wang, P.-Y.; Liu, M.-Z.; Lyu, F.; Ma, M.-W.; Ren, X.-Y.; Gao, X.-S. Biomarkers for Prostate Cancer: From Diagnosis to Treatment. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 3350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morote, J.; Campistol, M.; Celma, A.; Regis, L.; de Torres, I.; Semidey, M.E.; Roche, S.; Mast, R.; Santamaría, A.; Planas, J.; et al. The Efficacy of Proclarix to Select Appropriate Candidates for Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Derived Prostate Biopsies in Men with Suspected Prostate Cancer. World J. Men’s Health 2022, 40, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morote, J.; Celma, A.; Méndez, O.; Trilla, E. Sequencing the Barcelona-MRI Predictive Model and Proclarix for Improving the Uncertain PI-RADS 3. BJUI Compass 2024, 5, 1252–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.