Simple Summary

Around 2.3 million new breast cancer cases arise every year globally. Early diagnosis and targeted therapy are important to developing new therapeutic drugs for breast cancer treatment. This study aims to understand the context-dependent role of ARID1A, a key component of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex that shows frequent alterations across cancers, including breast cancer. Understanding ARID1A’s role is important because loss of ARID1A disrupts DNA repair, cell-cycle control, and chromatin regulation, leading to aggressive tumor progression via enhancing EMT and activating PI3K/AKT oncogenic signaling; conversely, abnormal overexpression of ARID1A may induce oxidative stress by CYP450 and initiate tumor growth. Thus, this study highlights the context-dependent role of ARID1A and supports its potential as a diagnostic biomarker and therapeutic target for the treatment management of breast cancer and other malignancies.

Abstract

ARID1A, a key subunit of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex, plays a context-dependent function in cancer, acting both as a tumor suppressor and, in certain conditions, as an oncogene. ARID1A, as a tumor suppressor, maintains transcriptional regulation, genomic stability, and cellular differentiation. In breast cancer, ARID1A loss-of-function leads to dysregulation of cell cycle checkpoints and impaired DNA repair and promotes epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), jointly accelerating tumor proliferation and increasing therapeutic resistance. Notably, context-dependent ARID1A loss-of-function often concurs with activation of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and corresponds with poor prognosis. On the contrary, aberrant ARID1A overexpression can provoke oxidative stress and agitate the cytochrome P450 system, potentially facilitating early tumorigenesis. Consequently, understanding ARID1A’s dual and context-dependent role highlights its potential as a biomarker and therapeutic target in precision oncology.

1. Introduction

Among malignancies, metastasis remains a major cause, placing a financial and psychological burden on affected individuals. During metastatic progression, genomic alterations underscore the importance of identifying genetic markers to inform therapeutic strategies and improve cancer management. In the early stages, clinically significant genetic mutations in cancers are prevalent and complex [1].

Globally, breast cancer is the second most common cancer and remains the most common cancer in women. WHO reports that about 2.3 million new cases are diagnosed every year [https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/breast-cancer; accessed on 14 August 2025]. In 2022, it was the leading cancer diagnosis in 157 of 185 countries and caused 670,000 deaths. As stated by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), about 1 in 20 women worldwide will develop breast cancer during their lifetime [https://www.iarc.who.int/news-events/breast-cancer-cases-and-deaths-are-projected-to-rise-globally; accessed on 24 February 2025]. The agency projects that if this continues every year, by 2050, the number of new breast cancer cases might increase to 3.2 million, with 1.1 million deaths every year [2,3]. Among all breast cancer cases, TNBC accounts for approximately 10–20% and is more widespread among women [4,5]. In India, breast cancer accounts for 13.5% of all cancers and shows a rising trend among younger women. It is projected to become the leading cause of cancer-related deaths among Indian women by 2030 [6]. The disease continues to rise in occurrence; India bears almost one-third of the worldwide burden, resulting in over 70,000 deaths annually [7]. Over the past four decades, the occurrence of breast cancer has progressively increased, affecting 19 out of every 100,000 Indian women. A large cohort study involving 8654 complex breast malignancy samples revealed that 80.4% of malignancies had genetic alterations in at least one clinically significant pathway [8].

Breast cancer is a major global public health problem for women. The prevalence and incidence rates of breast malignancy have risen significantly over the past several years. Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is a heterogeneous and aggressive subtype of breast cancer that lacks the expression of estrogen receptors (ERs), progesterone receptors (PRs), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). Compared to other breast cancer subtypes, TNBC is associated with a higher incidence of metastasis, poor overall survival rates, and greater treatment complexity. Although several molecular targets, like phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase/protein kinase B/mammalian target of rapamycin (PI3K/AKT/mTOR), have been explored for TNBC therapy, their efficacy remains limited [9].

Recent clinical trials have significantly advanced breast cancer treatment across disease subtypes. The KEYNOTE-522 enrolled 1174 patients with stage II–III triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), demonstrating clear benefit from adding pembrolizumab to standard therapy [10]. In the case study of IMpassion130, which included 902 patients with advanced or metastatic TNBC, improved outcomes were observed with atezolizumab in PD-L1–positive disease [11]. The large TAILORx trial (NCT00310180) followed 10,273 women with early-stage, HR+/HER2- breast cancer, helping refine which patients truly need chemotherapy. Similarly, monarchE studied 5637 women with high-risk HR+/HER2- early breast cancer, supporting the use of adjuvant abemaciclib [12]. In CREATE-X, 910 HER2- patients with residual disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy showed improved survival with adjuvant capecitabine [13,14]. Even though major progress has been made in large clinical trials like KEYNOTE-522, IMpassion130, TAILORx, monarchE, and CREATE-X, breast cancer continues to be a significant health burden. Collectively, these studies have helped to enrich treatment across various subtypes and significantly expanded therapeutic options for many patients. This highlights the need for continued research for better biomarkers, more effective targeted therapies, and treatment strategies that can further improve outcomes for all patients.

Together with this background, our objective is to investigate the crucial role of ARID1A, a key chromatin-remodeling gene whose alterations are increasingly linked to breast cancer and several other malignancies. Understanding its functional impact may provide new insights into tumor development, therapeutic vulnerabilities, and potential targets for precision cancer treatment.

2. SWItch/Sucrose Non-Fermentable (SWI/SNF) Chromatin Remodeling Complex

An epigenetic modification is an important early event in cancer and contributes to frequent changes in the functioning of cancer cells. Multitude evidences indicates that the SWI/SNF (Switch/Sucrose Non-Fermentable) chromatin remodeling complex is important for the regulation of genomic integrity, transcription, and the development of cellular components [15]. Targeting the SWI/SNF complex may provide therapeutic strategies to exploit the vulnerabilities associated with its divergences in malignancies.

The ATPase subunits of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex represent a group of evolutionarily conserved proteins responsible for regulating chromatin accessibility, relocating nucleosomes through ATP hydrolysis. The bromodomain in these ATPase subunits aids in the recognition of acetylated histones [16]. Functionally, these complexes are important for regulating gene expression and maintaining stem cell pluripotency. Three distinct forms of SWI/SNF complex are BRG1/BRM-associated factor (BAF), Polybromo-associated BAF complex (PBAF), and non-canonical BAF (ncBAF) complex. Each of these has unique subunits that assemble in various forms to modulate nucleosome positioning and chromatin accessibility. Via these mechanisms, the SWI/SNF complex plays a crucial role in DNA repair, replication, and transcriptional initiation [17]. The interplay among the SWI/SNF complex and other epigenetic regulators boosts the impact on gene expression. This complex works with histone modifiers, histone acetyltransferases (HATs), and histone deacetylases (HDACs) to produce either a permissive or restrictive chromatin state and interacts with DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) and ten-eleven translocation (TET) enzymes to alter DNA methylation patterns. Thus, the SWI/SNF complex functions as an epigenetic integrator that dynamically regulates chromatin architecture corresponding to various physiological signals [18]. Around 20–25% of all malignancies have mutations in the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex and underscore its important role in tumor proliferation. These genetic alterations reduce the expression of SWI/SNF subunits by interrupting regular chromatin remodeling and transcriptional regulation [19].

3. Dysregulation of SWI/SNF in ER+ Cancer

Genetic mutations, deletions, and aberrant expression of the SWI/SNF complex’s subunits often result in its dysfunction in breast cancer. This affects and disturbs chromatin modifications and genome stability by promoting the growth of tumor cells. These changes alter the role of estrogen receptor (ER), which plays a major role in hormone receptor-positive breast cancer [20]. The SWI/SNF complex regulates gene expression by enabling the binding of ER to its target genes in estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) breast cancer. ER binds to estrogen, interacts with specific DNA sequences, and activates genes implicated in cell growth and proliferation. The functional impairment mechanism of the SWI/SNF complex becomes disturbed, which leads to abnormal gene expression and enhanced tumor progression. Moreover, dysregulation of the SWI/SNF complex also provides resistance against endocrine therapies, such as tamoxifen, by inhibiting ER activation. The malfunctioning SWI/SNF complex allows cancer cells to bypass estrogen signaling or activate substitute pathways, thereby decreasing the therapeutic efficacy of treatment [21,22]. Furthermore, SWI/SNF dysfunction disturbs the stimulation of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a critical mechanism in metastasis. EMT is a regulated process in which epithelial cells acquire mesenchymal traits, including increased motility, invasiveness, and resistance to apoptosis. It is largely driven by microenvironmental signals such as TGF-β, Wnt, and Notch. Though genetic alterations might affect cells to undergo EMT, external signals from the tumor microenvironment mostly begin and maintain this process. Thus, this perspective highlights the regulation of EMT transitions [23,24]. This complex activates transcription factors that restrain epithelial markers such as E-cadherin and upregulate mesenchymal markers such as vimentin, thus enhancing cell invasion and motility [25,26]. Therefore, the dysregulation of the SWI/SNF complex has important implications for clinical results and metastatic progression in ER+ breast cancers.

4. ARID1A: Biological Functions and Its Role in Breast Cancer

ARID1A (AT-rich interaction domain 1A) is a subunit of the canonical BAF (cBAF) in the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex that controls where the complex binds regulatory DNA in differentiated cells. Its crucial role is maintain genomic integrity, as shown by its frequent mutations in various cancers, including gastric and ovarian cancers [27,28]. ARID1A is important for targeting SWI/SNF to genomic spots occupied by transcription factors, such as estrogen receptor (ER), GATA3, and FOXA1 in luminal breast epithelial cells. Mutations or deficiency of ARID1A disrupt this mechanism and cause SWI/SNF to fail to reside in cis-regulatory elements [29,30]. The ARID1A protein performs its primary function across different cancers by positioning cBAF at tissue-specific regulatory elements [27,30]. Loss of ARID1A drives a luminal-to-basal lineage modification in ER+ breast cancer, which decreases ER- dependent transcription and resistance to endocrine therapies such as fulvestrant by separating SWI/SNF from ER/GATA3/FOXA1-bound enhancers [28,29,31]. By engaging HDAC1 to suppress histone H4 acetylation, ARID1A acts as a controller; therefore, ARID1A deficiency results in increased H4 acetylation and activates growth-promoting transcriptional programs [27,32]. ARID1A resists ER- driven proliferative signaling and tumor growth in endometrial cancer. This indicates that ARID1A limits ER production in a tissue-specific context [33,34]. Linking of ARID1A to androgen receptors (ARs) has been scarcely examined in recent studies; ARID1A modifies steroid receptor-linked lineage programs, suggesting potential for corresponding interactions [35]. AR shows context-dependent roles in ER breast cancers that loss of ARID1A disrupts chromatin regulators affecting drug sensitivities and self-regulation of ER; thus, future investigation of ARID1A-AR interactions across breast cancer subtypes is necessary [27,32]. ARID1A, since it is a tumor suppressor, experiences weakened functions due to loss of SWI/SNF targeting to lineage-specific enhancers, leading to dedifferentiation and therapy resistance. Reduced HDAC1 binding increases acetylation-dependent transcription of oncogenic programs, and ARID1A mutations yield distinct phenotypes depending on tissue-specific transcriptional changes [27,30,36]. Thus, understanding the role of ARID1A opens a new path for advanced treatment approaches in cancer biology. The restoration of wild-type ARID1A expression shows suppressed cell proliferation and tumor growth, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic target in ARID1A-mutated cancers [33]. This developing understanding of ARID1A’s role in breast cancer not only highlights its implications for treatment but also broadens the landscape of cancer biology. By explaining the mechanisms through which ARID1A mutations influence tumor behavior and immune interactions, researchers can address unique characteristics of both ER+ and ER- breast cancers, enhancing the precision of oncology and improving patient outcomes.

The significant cross-talk between ARID1A and genomic instability in TNBC is due to the loss of ARID1A, which disrupts DNA damage repair and increases the accumulation of genomic alterations. ARID1A is lost or downregulated (mutation, deletion, epigenetic silencing) in a subset of TNBC tumors [37]. In the TNBC context, genomic instability might fuel the aggressive phenotype: high metastatic potential, poor prognosis, and possibly contribute to immune evasion/immunoediting. Indeed, TNBC tumors with low ARID1A show poor outcomes [9,38,39]. Additionally, genomic instability may make such tumors more immunogenic (neoantigens), potentially affecting immune infiltration and response to immunotherapy, which is especially relevant since some TNBCs are treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. The general role of ARID1A loss in activation of the cytosolic DNA-sensing (cGAS–STING) pathway after DNA damage supports this possibility [37,39].

Although extensive research has established that ARID1A regulates DNA double-strand break repair, replication stress responses, and chromatin structure in other tumor models, comparable mechanistic validation in TNBC models is still lacking [37,40].

5. Correlation of ARID1A and PIK3CA in TNBC and Other Cancers

ARID1A (AT-rich interactive domain-containing protein 1A), a critical component of the SWI/SNF remodeling complex, is located on chromosome 1p36.11. It encodes the protein BAF250a, which plays a crucial role in regulating gene expression through chromatin structure modification. Mutations in this regulatory gene have been identified in various human cancers, including breast cancer [41,42]. Co-occurring ARID1A deficiency and PI3KA mutations are observed in ~6% of all cancer cases [43].

Functional Consequences of ARID1A in Tumor Progression

Previous studies have shown that loss of ARID1A leads to the activation of several oncogenic pathways, including the PI3K/AKT pathway, nuclear localization of YAP (Yes-Associated Protein), and Hippo pathway, thereby enhancing cell proliferation and metastatic potential in TNBC cells. Recent studies further demonstrate that the loss of ARID1A expression increases EMT (epithelial–mesenchymal transition) markers’ expression, which are associated with enhanced migration and tumor cell aggression [9,44]. Under normal circumstances, ARID1A-proficient cells sustain proliferation homeostasis, as ARID1A negatively regulates the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. However, loss-of-function or mutation of ARID1A disturbs this balance, resulting in abnormal activation of PI3K/AKT signaling. This dysregulation has been implicated in various malignancies, including TNBC, and is frequently associated with poor diagnosis and violent tumor behavior [45,46,47,48]. The interplay between ARID1A and the PI3K/AKT pathway plays a significant role in tumor development. In TNBC, the PI3K/AKT pathway is often dysregulated, and signaling pathways are activated through genetic mutations or loss of PTEN, thus promoting tumorigenesis and therapeutic resistance [49]. Around 60% of TNBC patients show PTEN alterations, which activate the PI3K/AKT pathway and increase tumor cell growth and survival.

Targeting of the PI3K/AKT pathway, therefore, has received significant therapeutic interest. However, the development of resistance to inhibitors such as buparlisib and MK-2206 has compromised their clinical effectiveness. Preclinical studies suggested a dual therapeutic strategy inhibiting the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway while restoring ARID1A and PTEN expression, which may be used to overcome and conquer resistance and develop treatment outcomes [50]. Drugs able to reactivate ARID1A and PTEN expression, by inhibiting PI3K/AKT and YAP signaling, are likely to suppress tumor growth and increase survival in TNBC patients [51]. Additionally, re-expression of ARID1A reduces cell proliferation, confirming its role as a tumor suppressor and ability to inhibit PI3K/AKT pathway activation [52].

6. Clinical and Preclinical Evidence for Targeting ARID1A and PIK3CA

Approximately 33% of ovarian clear cell carcinoma cases exhibit co-mutations of ARID1A and PIK3CA, which activate pro-inflammatory cytokine genes via the NF-kB pathway, thereby promoting tumor growth. In an in vivo experiment using engineered mice harboring ARID1A loss and PIK3CA mutations, treatment with the PIK3 inhibitor buparlisib led to a dose-dependent reduction in AKT levels and tumor viability, highlighting the therapeutic potential of buparlisib in OCCC with these co-mutations [32]. Similarly, a clinical trial with PI3K inhibitor copanlisib in PIK3CA- and ARID1A-mutant cancers demonstrated a significant decrease in tumor growth. The inhibition mechanism was attributed to PUMA induction mediated by FOXO3a, which was aberrantly expressed following p53/p21 pathway dysregulation caused by ARID1A loss [53]. Similarly, a high frequency of cholangiocarcinoma cases also harbor ARID1A and PI3K mutations. Studies evaluating AKT inhibitors (MK-2206) in ARID1A-deficient cholangiocarcinoma cell lines revealed increased sensitivity to the drug, suggesting that targeting the PI3K/AKT pathway could improve therapeutic outcomes in these tumors [54].

Using ARID1A knockdown in cell-based assay and mutant PIK3CA human ovarian epithelial cell lines, the grouping of mutations induced cell transformation and cytokine gene induction. Systematically, ARID1A loss-of-function enables the recruitment of the Sin3A-HDAC complex, while PIK3CA mutations promote the release of RelA from IkB, both of which are most important for cytokine gene activation. These findings suggest that NF-kB inhibition may represent a viable therapeutic strategy for tumors harboring these co-mutations [55].

Furthermore, when using in vivo models of ARID1A- and PIK3CA-mutated ovarian clear cell carcinoma, treatment with an HDAC6 inhibitor reduced tumor growth and improved survival rates by promoting the activation of IFN gamma-positive CD8 T cells. For both in vitro and in vivo studies using patient-derived xenografts from ARID1A-deficient bladder cancer cell lines, treatment with the EZH2 inhibitor GSK-126 exhibited synergistic effects in reducing cell viability, highlighting the potential of PI3K pathway inhibitors in ARID1A-deficient bladder cancer therapy [56].

Additionally, inhibition of the PI3K pathway using LY294002 in ARID1A-deficient, radioresistant pancreatic cancer cells increased apoptosis and impaired DNA damage repair, further supporting the therapeutic relevance of this approach [57,58]. A large-scale screening of 551 kinase inhibitors in ARID1A isogenic gastric cancer cells identified the AKT inhibitor AD5363 (capivasertib) as particularly effective, significantly reducing cell viability by activating the Caspace-3/GSDME pathway. Collectively, these studies underline the importance of PI3K/AKT signaling in cancers with ARID1A deficiency and PIK3CA co-mutations [59]. A study of the molecular mechanism underlying ARID1A’s role in cancer development, with prognostic implications and pathological uniqueness, remains unexplored [48]. Ongoing research focusing on ARID1A and PI3K/AKT for the treatment of TNBC, by restoring ARID1A expression and inhibiting PI3K/AKT signaling, could successfully reduce tumor aggressiveness and improve the clinical outcomes in TNBC.

7. Context-Dependent Role of ARID1A

By enabling DNA repair, regulating cell cycle checkpoints, and maintaining epigenetic stability, ARID1A acts as a tumor suppressor. Loss of function of ARID1A results in genomic instability, accumulation of mutations, and tumor initiation with uncontrolled cell proliferation [30]. In later stages of tumorigenesis, haploinsufficiency or complete loss-of-function ARID1A is linked to enhanced tumor development, particularly by promoting cell migration and metastasis. This is mediated by the downregulation of tumor-suppressor genes such as E-cadherin, along with transcriptional reprogramming toward metastasis-related gene expression profiles [60,61,62]. E-cadherin, encoded by the CDH1 gene, is a traditional tumor suppressor that upholds epithelial integrity by promoting robust calcium-dependent cell–cell adhesion. The epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a critical stage in tumor invasion and metastasis, disturbing tissue construction and cell polarity by promoting loss of E-cadherin. Loss of E-cadherin is associated with the development of human cancers. In many epithelial cancers, inactivation of CDH1 occurs via mutations, promoter hypermethylation, transcriptional repression, or proteolytic cleavage [63,64,65]. This finding underscores the crucial role of ARID1A deficiency in chromatin architecture and gene regulation in facilitating metastatic activity.

8. Underlying Mechanisms of ARID1A in Oncogenic Functions

Current studies and findings show that the role of ARID1A is highly context-dependent, acting as both a tumor suppressor and a tumor promoter depending on the cancer stage, tissue type, and mutational background [30,62,66]. Depending on the environment and ecological factors, a gene can play a role in cancer cells, either promoting or suppressing tumors. This point of view is reinforced by current findings that the role of ARID1A is highly context-dependent, varying with cancer stage and mutations. As a result, this study seeks to accept the tumor system view and tumor ecology and to make a fundamental break from the theoretical constraints of the existing somatic mutation paradigm. The researchers expect that cancer research will move toward ecological landscapes, forming a new system different from genetic molecular maps [67]. In various mouse models of liver cancer, ARID1A has been shown to exhibit tumor-promoting activity by promoting early transformation, potentially through regulation of oxidative stress pathways mediated by the cytochrome P450 (CYP450) system, which generates reactive oxygen species (ROS). High ROS levels provoke DNA damage, promote mutagenesis, and create a tumor-permissive background that accelerates both initiation and progression in liver cancer.

ARID1A overexpression impacts long-range chromatin modifications that enable transcription factors, such as SOX6, to reinforce the expression of oncogenic genes. This collaboration enhances gene expression and promotes cell propagation and migration while repressing tumor suppressor genes involved in cell adhesion, like E-cadherin, thereby facilitating invasiveness and metastasis [68,69]. ARID1A overexpression and increased oxidative stress align with established studies indicates that antioxidants can suppress tumor initiation but might, in contradiction, promote tumor progression when redox balance is disrupted [70,71]. Moreover, ARID1A alters the activity of transcription factors like HNF4A that regulate hepatocyte differentiation, leading to dedifferentiation and a more stem-like, aggressive phenotype. ARID1A overexpression can alter epigenetic regulation, favoring a pro-oncogenic state by upregulating cell cycle regulators through activation of E2F target pathways.

In fact, loss of ARID1A might enhance oncogenic signaling, such as PI3K/AKT activation, leading to tumor growth. The absence of ARID1A compromises DNA repair pathways, especially homologous recombination, leading to genomic instability. The instability that promotes or inhibits tumor development appears to depend on the stage of malignancy. A comprehensive study indicates that in the early stages of carcinogenesis, ARID1A acts as an impediment to transformation, maintaining chromatin integrity and genomic stability. As tumors develop, mutational inactivation of ARID1A enables cancer cells to bypass growth limitations and adjust to an active tumor microenvironment.

9. Therapeutic Strategies and Resistance Mechanisms

9.1. EZH2 Inhibitors

ARID1A-mutant cancers are particularly sensitive to EZH2 inhibition (e.g., GSK126), an effect linked to the suppression of PI3K/AKT signaling. This has led to clinical evaluation of EZH2 inhibitors, such as tazemetostat, in tumors harboring ARID1A alterations. However, resistance to EZH2 inhibitors can arise through mechanisms such as switching from SMARCA4 to SMARCA2 or upregulation of BCL2, both of which represent potential targets to overcome therapeutic resistance [31].

9.2. PARP Inhibitors

ARID1A deficiency compromises double-strand break repair and impairs DNA damage checkpoint signaling, providing a mechanistic rationale for the sensitivity of these tumors to PARP inhibitors (PARPi) in preclinical models. However, responses to PARPi are heterogeneous and can be limited by established resistance mechanisms, including restoration of homologous recombination, PARP1 downregulation, and enhanced replication fork protection [40].

9.3. PI3K/AKT/mTOR Inhibitors

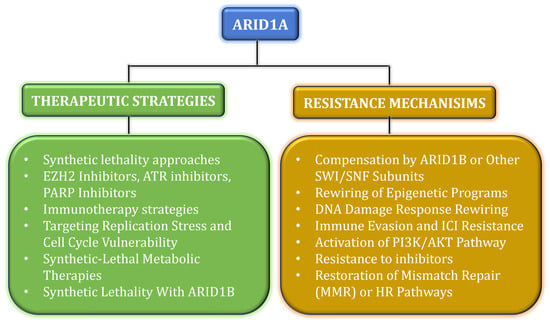

ARID1A-deficient tumors can become PI3K/AKT-dependent via upregulation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase regulatory subunit (PIK3R3). These tumors are particularly sensitive to PI3K inhibitors, such as alpelisib and pictilisib, especially when used in combination with EZH2 inhibitors. These findings provide a strong rationale for evaluating PI3K pathway inhibitors in preclinical and clinical studies targeting ARID1A-altered tumors [57]. Table 1 shows the mechanism of drugs that target ARID1A; Figure 1 displays the therapeutic approaches and resistant mechanisms of ARID1A.

Table 1.

Therapeutic drugs targeting ARID1A showing drug mechanisms, resistance, and current status of drugs in clinical development.

Figure 1.

The schematic representation shows the therapeutic approaches in green and the resistant mechanisms in mustard for ARID1A.

9.4. Other Strategies

Several therapeutic strategies exploit synthetic lethality in ARID1A-deficient tumors, including ATR inhibitors, HDAC inhibitors, PLK1 inhibitors, BCL2 inhibitors, and other targeted agents. Additionally, immune-modulating strategies are under investigation, as ARID1A loss can increase neoantigen load and induce DNA mismatch repair (MMR) deficiencies in certain tumors, potentially enhancing responsiveness to immunotherapy [43,85].

Current multi-omics studies indicate that ARID1A loss-of-function drives adaptive transcriptional reprogramming that grants resistance to targeted therapies. For instance, ARID1A-deficient cells maintain MAPK1/3 and JNK activity, enabling evasion of BRAF/MAPK inhibition, and improved PI3K/AKT signaling can bypass the effects of overcoming targeted treatments, highlighting the need for combination or context-specific therapeutic approaches [86,87]. Weakened PARP inhibitor effectiveness includes the restoration of HR [88]. Efflux resistance enhances the expression of drug efflux pumps, modifies drug metabolism through CYP450 modulation [43], and creates changes in histone modification patterns that alter transcriptional accessibility [79].

9.5. Combination with PARP Inhibitors—Included Therapies

Preclinical and translational studies support combining PARP inhibitors with DNA-damaging agents and other pathway inhibitors to exploit ARID1A deficiency, as tumors lacking ARID1A exhibit enhanced PARPi sensitivity. Loss of ARID1A disturbs homologous recombination and cell cycle checkpoints, increasing reliance on PARP-mediated DNA repair and enabling synthetic lethality with PARP inhibitors either as monotherapy or in combination with other agents [74,76].

PI3K pathway inhibition can suppress HR repair, thereby sensitizing HR-proficient or ARID1A-altered tumors to PARP inhibitors. Preclinical models and clinical reports support the combination of olaparib with PI3K inhibitors, such as alpelisib, as an effective strategy in tumors devoid of canonical HR defects. This underscores the potential therapeutic applicability of PARPi [75,80].

Additionally, Ataxia-Telangiectasia and Rad3-related protein (ATR) inhibitors have been recognized as synthetic lethal partners for ARID1A-deficient tumors and represent rational combinations with PARPi. Preclinical reports of BRCA-related models indicate that ATR and PARPi co-treatment can overcome homologous recombination restoration and PARPi resistance, making this approach promising for targeting ARID1A-deficient cancers [75,77,82].

10. Stage-Specific Impact of Tumor Development

The bidirectional function of ARID1A highlights its complex role in tumorigenesis, which is influenced by factors such as timing, expression levels, and cellular context. Understanding its role is important for identifying therapeutic treatments to restore ARID1A expression [30,89]. The molecular mechanisms indicate that ARID1A overexpression can act as a vital driver of tumor initiation and progression by altering chromatin remodeling, metabolic regulation, and transcriptional reprogramming.

11. Conclusions

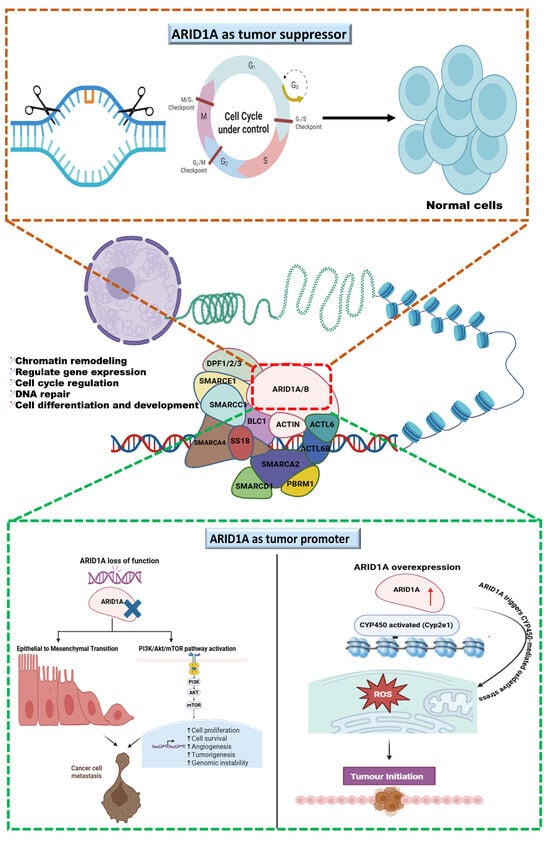

ARID1A is an ambiguous regulator in cancer biology, as its role in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is context-dependent. Usually, it functions as a tumor suppressor by maintaining chromatin structure, regulating genomic stability, and supporting DNA repair. However, ARID1A exhibits oncogenic features under specific cellular circumstances. In TNBC, loss-of-function mutations or downregulation of ARID1A disturb cell cycle regulation and DNA repair, increase EMT, and activate the PI3K/AKT pathway, forcing aggressive tumor proliferation and resistance to treatments. Conversely, overexpression of ARID1A deregulates oxidative stress and promotes early tumorigenesis and metastasis by altering transcriptional programs (Figure 2). The frequent co-occurrence of ARID1A loss with PIK3CA mutations in various cancers, including TNBC, ovarian clear cell carcinoma, and cholangiocarcinoma, highlights the vital role of ARID1A and PI3K/AKT in tumorigenesis. This provides a strong rationale for targeting ARID1A in combination with PI3K/AKT signaling.

Figure 2.

The graphical illustration represents ARID1A as a tumor suppressor, a key subunit of SWI/SNF remodeling complex that maintains DNA repair, and ARID1A’s role in genome regulation and context-dependent consequences. ARID1A as a tumor suppressor controls cell cycle and maintains genome stability, whereas at the bottom, featuring ARID1A as a tumor promoter, the left panel shows that ARID1A’s divergent dysregulation loss of function promotes oncogenesis through EMT and PI3K/AKT/mTOR activation, leading to cancer cell metastasis; the right panel shows that ARID1A’s overexpression promotes oncogenesis via CYP450-mediated ROS generation and initiates the tumor.

Thus, ARID1A’s dualistic function highlights the need for context-specific treatment approaches. Continuous research, along with precision oncology and biomarker-driven clinical trials, makes ARID1A a promising therapeutic biomarker in all malignancies and also improves TNBC treatment management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.R.; Resources, S.R. and D.P.; Data Curation, G.S., D.P., M.S., and S.R.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, G.S., D.P., M.S., and S.R.; Writing—Review and Editing, G.S., D.P., M.S., J.J., and S.R.; Supervision, S.R. and D.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Shankari Gopalakrishnan gratefully acknowledges the Karpagam Academy of Higher Education for the research fellowship.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kimbung, S.; Loman, N.; Hedenfalk, I. Clinical and Molecular Complexity of Breast Cancer Metastases. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2015, 35, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Harper, A.; McCormack, V.; Sung, H.; Houssami, N.; Morgan, E.; Mutebi, M.; Garvey, G.; Soerjomataram, I.; Fidler-Benaoudia, M.M. Global Patterns and Trends in Breast Cancer Incidence and Mortality across 185 Countries. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 1154–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedeta, E.T.; Jobre, B.; Avezbakiyev, B. Breast Cancer: Global Patterns of Incidence, Mortality, and Trends. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 10528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burstein, M.D.; Tsimelzon, A.; Poage, G.M.; Covington, K.R.; Contreras, A.; Fuqua, S.A.W.; Savage, M.I.; Osborne, C.K.; Hilsenbeck, S.G.; Chang, J.C.; et al. Comprehensive Genomic Analysis Identifies Novel Subtypes and Targets of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 1688–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, J.; Gray, W.H.; Lehmann, B.D.; Bauer, J.A.; Shyr, Y.; Pietenpol, J.A. TNBCtype: A Subtyping Tool for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancer Inform. 2012, 11, CIN.S9983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panchaware, P.S.; Shekokar, S.S. A Review on Ayurvedic and Modern Aspects of Breast Cancer. World J. Biol. Pharm. Health Sci. 2023, 14, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaitonde, R.U.; Gajbhiye, N. EPIDEMIOLOGY OF BREAST CANCER IN INDIA. Asian J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Environ. Sci. 2022, 24, 204–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.S.; Gay, L.M. Comprehensive Genomic Sequencing and the Molecular Profiles of Clinically Advanced Breast Cancer. Pathology 2017, 49, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Qiao, X.; Xie, Y.; Guo, D.; Li, B.; Cao, J.; Tao, Z.; Hu, X. Chromatin Remodelling Molecule ARID1A Determines Metastatic Heterogeneity in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer by Competitively Binding to YAP. Cancers 2023, 15, 2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, P.; Cortes, J.; Dent, R.; McArthur, H.; Pusztai, L.; Kümmel, S.; Denkert, C.; Park, Y.H.; Hui, R.; Harbeck, N.; et al. Overall Survival with Pembrolizumab in Early-Stage Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 1981–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, P.; Rugo, H.S.; Adams, S.; Schneeweiss, A.; Barrios, C.H.; Iwata, H.; Diéras, V.; Henschel, V.; Molinero, L.; Chui, S.Y.; et al. Atezolizumab plus Nab-Paclitaxel as First-Line Treatment for Unresectable, Locally Advanced or Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (IMpassion130): Updated Efficacy Results from a Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, S.R.D.; Toi, M.; O’Shaughnessy, J.; Rastogi, P.; Campone, M.; Neven, P.; Huang, C.-S.; Huober, J.; Jaliffe, G.G.; Cicin, I.; et al. Abemaciclib plus Endocrine Therapy for Hormone Receptor-Positive, HER2-Negative, Node-Positive, High-Risk Early Breast Cancer (MonarchE): Results from a Preplanned Interim Analysis of a Randomised, Open-Label, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2023, 24, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, N.; Lee, S.-J.; Ohtani, S.; Im, Y.-H.; Lee, E.-S.; Yokota, I.; Kuroi, K.; Im, S.-A.; Park, B.-W.; Kim, S.-B.; et al. Adjuvant Capecitabine for Breast Cancer after Preoperative Chemotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 2147–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bischoff, H.; Espié, M.; Petit, T. Neoadjuvant Therapy: Current Landscape and Future Horizons for ER-Positive/HER2-Negative and Triple-Negative Early Breast Cancer. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2024, 25, 1210–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakravarty, T. UNDERSTANDING THE ROLES OF HETEROGENOUS SWI/SNF COMPLEXES IN REGULATION OF DIFFERENTIAL GENE EXPRESSION. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Rhode Island, Kingston, RI, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Phelan, M.L.; Sif, S.; Narlikar, G.J.; Kingston, R.E. Reconstitution of a Core Chromatin Remodeling Complex from SWI/SNF Subunits. Mol. Cell 1999, 3, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Wang, B.; Hu, H. Research Progress of SWI/SNF Complex in Breast Cancer. Epigenetics Chromatin 2024, 17, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, K.D. REGULATION OF COMPOSITION AND FUNCTIONS OF SWI/SNF CHROMATIN REMODELING COMPLEX. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Rhode Island, Kingston, RI, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Shain, A.H.; Pollack, J.R. The Spectrum of SWI/SNF Mutations, Ubiquitous in Human Cancers. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e55119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristofaro, M.F.D.; Betz, B.L.; Rorie, C.J.; Reisman, D.N.; Wang, W.; Weissman, B.E. Characterization of SWI/SNF Protein Expression in Human Breast Cancer Cell Lines and Other Malignancies. J. Cell Physiol. 2001, 186, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belandia, B. Targeting of SWI/SNF Chromatin Remodelling Complexes to Estrogen-Responsive Genes. EMBO J. 2002, 21, 4094–4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Chambers, K.J.; Faller, D.V.; Wang, S. Reprogramming of the SWI/SNF Complex for Co-Activation or Co-Repression in Prohibitin-Mediated Estrogen Receptor Regulation. Oncogene 2007, 26, 7153–7157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, A.M.; Gayam, P.K.R.; Baby, B.T.; Aranjani, J.M. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Cancer: A Focus on Itraconazole, a Hedgehog Inhibitor. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA) Rev. Cancer 2025, 1880, 189279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafelski, S.M.; Theriot, J.A. Establishing a Conceptual Framework for Holistic Cell States and State Transitions. Cell 2024, 187, 2633–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, V.S.; Rogers, C.; Reisman, D. Alteration to the SWI/SNF Complex in Human Cancers. Oncol. Rev. 2010, 4, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.J.; Xiao, Y.; Parsan, N.; Medwig-Kinney, T.N.; Martinez, M.A.Q.; Moore, F.E.Q.; Palmisano, N.J.; Kohrman, A.Q.; Chandhok Delos Reyes, M.; Adikes, R.C.; et al. The SWI/SNF Chromatin Remodeling Assemblies BAF and PBAF Differentially Regulate Cell Cycle Exit and Cellular Invasion in Vivo. PLoS Genet. 2022, 18, e1009981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trizzino, M.; Barbieri, E.; Petracovici, A.; Wu, S.; Welsh, S.A.; Owens, T.A.; Licciulli, S.; Zhang, R.; Gardini, A. The Tumor Suppressor ARID1A Controls Global Transcription via Pausing of RNA Polymerase II. Cell Rep. 2018, 23, 3933–3945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagarajan, S.; Rao, S.V.; Sutton, J.; Cheeseman, D.; Dunn, S.; Papachristou, E.K.; Prada, J.-E.G.; Couturier, D.-L.; Kumar, S.; Kishore, K.; et al. ARID1A Influences HDAC1/BRD4 Activity, Intrinsic Proliferative Capacity and Breast Cancer Treatment Response. Nat. Genet. 2020, 52, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, R.; Alver, B.H.; San Roman, A.K.; Wilson, B.G.; Wang, X.; Agoston, A.T.; Park, P.J.; Shivdasani, R.A.; Roberts, C.W.M. ARID1A Loss Impairs Enhancer-Mediated Gene Regulation and Drives Colon Cancer in Mice. Nat. Genet. 2017, 49, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.N.; Roberts, C.W.M. ARID1A Mutations in Cancer: Another Epigenetic Tumor Suppressor? Cancer Discov. 2013, 3, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitler, B.G.; Aird, K.M.; Garipov, A.; Li, H.; Amatangelo, M.; Kossenkov, A.V.; Schultz, D.C.; Liu, Q.; Shih, I.-M.; Conejo-Garcia, J.R.; et al. Synthetic Lethality by Targeting EZH2 Methyltransferase Activity in ARID1A-Mutated Cancers. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, R.L.; Damrauer, J.S.; Raab, J.R.; Schisler, J.C.; Wilkerson, M.D.; Didion, J.P.; Starmer, J.; Serber, D.; Yee, D.; Xiong, J.; et al. Coexistent ARID1A–PIK3CA Mutations Promote Ovarian Clear-Cell Tumorigenesis through pro-Tumorigenic Inflammatory Cytokine Signalling. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, B.; Wang, T.-L.; Shih, I.-M. ARID1A, a Factor That Promotes Formation of SWI/SNF-Mediated Chromatin Remodeling, Is a Tumor Suppressor in Gynecologic Cancers. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 6718–6727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegand, K.C.; Shah, S.P.; Al-Agha, O.M.; Zhao, Y.; Tse, K.; Zeng, T.; Senz, J.; McConechy, M.K.; Anglesio, M.S.; Kalloger, S.E.; et al. ARID1A Mutations in Endometriosis-Associated Ovarian Carcinomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 1532–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, T.; Banno, K.; Okawa, R.; Yanokura, M.; Iijima, M.; Irie-Kunitomi, H.; Nakamura, K.; Iida, M.; Adachi, M.; Umene, K.; et al. ARID1A Gene Mutation in Ovarian and Endometrial Cancers (Review). Oncol. Rep. 2016, 35, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Ju, Z.; Zhao, W.; Wang, L.; Peng, Y.; Ge, Z.; Nagel, Z.D.; Zou, J.; Wang, C.; Kapoor, P.; et al. ARID1A Deficiency Promotes Mutability and Potentiates Therapeutic Antitumor Immunity Unleashed by Immune Checkpoint Blockade. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 556–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wu, J.; Yan, H.; Wang, Y.; He, J. The Mutation and Low Expression of ARID1A Are Predictive of a Poor Prognosis and High Immune Infiltration in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2024, 24, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, X.; Zhao, J.-X.; Dong, F.; Cao, X.-C. ARID1A Mutation in Metastatic Breast Cancer: A Potential Therapeutic Target. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 759577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakr, A.; Della Corte, G.; Veselinov, O.; Kelekçi, S.; Chen, M.-J.M.; Lin, Y.-Y.; Sigismondo, G.; Iacovone, M.; Cross, A.; Syed, R.; et al. ARID1A Regulates DNA Repair through Chromatin Organization and Its Deficiency Triggers DNA Damage-Mediated Anti-Tumor Immune Response. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, 5698–5719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Peng, Y.; Wei, L.; Zhang, W.; Yang, L.; Lan, L.; Kapoor, P.; Ju, Z.; Mo, Q.; Shih, I.-M.; et al. ARID1A Deficiency Impairs the DNA Damage Checkpoint and Sensitizes Cells to PARP Inhibitors. Cancer Discov. 2015, 5, 752–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solzak, J.P.; Atale, R.V.; Hancock, B.A.; Sinn, A.L.; Pollok, K.E.; Jones, D.R.; Radovich, M. Dual PI3K and Wnt Pathway Inhibition Is a Synergistic Combination against Triple Negative Breast Cancer. npj Breast Cancer 2017, 3, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weisman, P.S.; Ng, C.K.Y.; Brogi, E.; Eisenberg, R.E.; Won, H.H.; Piscuoglio, S.; De Filippo, M.R.; Ioris, R.; Akram, M.; Norton, L.; et al. Genetic Alterations of Triple Negative Breast Cancer by Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing and Correlation with Tumor Morphology. Mod. Pathol. 2016, 29, 476–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, J.; Mandal, P.; Wang, T.-L.; Shih, I.-M. Treating ARID1A Mutated Cancers by Harnessing Synthetic Lethality and DNA Damage Response. J. Biomed. Sci. 2022, 29, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Castro, A.C.; Saura, C.; Barroso-Sousa, R.; Guo, H.; Ciruelos, E.; Bermejo, B.; Gavilá, J.; Serra, V.; Prat, A.; Paré, L.; et al. Phase 2 Study of Buparlisib (BKM120), a Pan-Class I PI3K Inhibitor, in Patients with Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2020, 22, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, T.; Saito, M.; Nakajima, S.; Saito, K.; Katagata, M.; Fukai, S.; Okayama, H.; Sakamoto, W.; Saze, Z.; Momma, T.; et al. ARID1A Deficiency Is Targetable by AKT Inhibitors in HER2-Negative Gastric Cancer. Gastric Cancer 2023, 26, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanafy, S.M.; Fayad, E.E.; Alabiad, M. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition Axis Lin 28, ARID1A, And ELF3 As A Novel Prognostic Triad in Invasive Ductal Breast Carcinoma. Egypt. J. Hosp. Med. 2023, 91, 5018–5029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onder, S.; Fayda, M.; Karanlık, H.; Bayram, A.; Şen, F.; Cabioglu, N.; Tuzlalı, S.; İlhan, R.; Yavuz, E. Loss of ARID1A Expression Is Associated with Poor Prognosis in Invasive Micropapillary Carcinomas of the Breast: A Clinicopathologic and Immunohistochemical Study with Long-Term Survival Analysis. Breast J. 2017, 23, 638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.D.; Lee, J.E.; Jung, H.Y.; Oh, M.-H.; Lee, J.-H.; Jang, S.-H.; Kim, K.-J.; Han, S.W.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, H.J.; et al. Loss of Tumor Suppressor ARID1A Protein Expression Correlates with Poor Prognosis in Patients with Primary Breast Cancer. J. Breast Cancer 2015, 18, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Z.; Hu, Y.; Raizada, D.; Bassal, M.A.; Tenen, D.G.; Karnoub, A.E. Long Noncoding RNA–Mediated Activation of PROTOR1/PRR5-AKT Signaling Shunt Downstream of PI3K in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2203180119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estévez, L.G.; García, E.; Hidalgo, M. Inhibiting the PI3K Signaling Pathway: Buparlisib as a New Targeted Option in Breast Carcinoma. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2016, 18, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Wei, J.; Liu, P. Attacking the PI3K/Akt/MTOR Signaling Pathway for Targeted Therapeutic Treatment in Human Cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 85, 69–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, J.E.; Jaferi, N.; Shonibare, Z.; Huang, G.S. ARID1A in Gynecologic Precancers and Cancers. Reprod. Sci. 2024, 31, 2150–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udgata, S.; Stoecker, J.N.; Shen, X.; Pasch, C.A.; Deming, D.A. Abstract 371: Co-Existent PIK3CA and ARID1A Mutations Lead to Enhanced Sensitivity to PI3K Inhibition through PUMA Induction by FOXO3a and P53/P21. Cancer Res. 2025, 85, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessiri, S.; Techasen, A.; Kongpetch, S.; Namjan, A.; Loilome, W.; Chan-on, W.; Thanan, R.; Jusakul, A. Therapeutic Targeting of ARID1A and PI3K/AKT Pathway Alterations in Cholangiocarcinoma. PeerJ 2022, 10, e12750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Lu, F.; Zhang, Y. Loss of HDAC-Mediated Repression and Gain of NF-ΚB Activation Underlie Cytokine Induction in ARID1A- and PIK3CA-Mutation-Driven Ovarian Cancer. Cell Rep. 2016, 17, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukumoto, T.; Fatkhutdinov, N.; Zundell, J.A.; Tcyganov, E.N.; Nacarelli, T.; Karakashev, S.; Wu, S.; Liu, Q.; Gabrilovich, D.I.; Zhang, R. HDAC6 Inhibition Synergizes with Anti-PD-L1 Therapy in ARID1A-Inactivated Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, 5482–5489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, H.; Chandrashekar, D.S.; Balabhadrapatruni, C.; Nepal, S.; Balasubramanya, S.A.H.; Shelton, A.K.; Skinner, K.R.; Ma, A.-H.; Rao, T.; Agarwal, S.; et al. ARID1A-Deficient Bladder Cancer Is Dependent on PI3K Signaling and Sensitive to EZH2 and PI3K Inhibitors. JCI Insight 2022, 7, e155899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Yang, G.; Ding, Y.; Dai, Y.; Xu, S.; Guo, Q.; Xie, A.; Hu, G. Inhibition of PI3K/AKT Signaling Pathway Radiosensitizes Pancreatic Cancer Cells with ARID1A Deficiency in Vitro. J. Cancer 2018, 9, 890–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, M.; Lin, Y.; Xue, C.; Sheng, K.; Guo, Z.; Han, Y.; Lin, H.; Wu, Y.; Sang, Y.; Chen, X.; et al. The AKT Inhibitor AZD5363 Elicits Synthetic Lethality in ARID1A-Deficient Gastric Cancer Cells via Induction of Pyroptosis. Br. J. Cancer 2024, 131, 1080–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Li, J.; Xu, J.; Zhang, S.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, W.; Yin, Z.; Wang, X. Decreased Expression of ARID1A Associates with Poor Prognosis and Promotes Metastases of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 34, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Deng, Q.; Wang, Q.; Li, K.-Y.; Dai, J.-H.; Li, N.; Zhu, Z.-D.; Zhou, B.; Liu, X.-Y.; Liu, R.-F.; et al. Exome Sequencing of Hepatitis B Virus–Associated Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 1117–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, H.-B.; Wang, X.-F.; Zhang, Q.; Tang, Z.-Q.; Jiang, Y.-H.; Fan, H.-Z.; Sun, Y.; Yang, P.-Y.; Liu, F. Reduced Expression of the Chromatin Remodeling Gene ARID1A Enhances Gastric Cancer Cell Migration and Invasion via Downregulation of E-Cadherin Transcription. Carcinogenesis 2014, 35, 867–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berx, G.; Roy, F. Van The E-Cadherin/Catenin Complex: An Important Gatekeeper in Breast Cancer Tumorigenesis and Malignant Progression. Breast Cancer Res. 2001, 3, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bücker, L.; Lehmann, U. CDH1 (E-Cadherin) Gene Methylation in Human Breast Cancer: Critical Appraisal of a Long and Twisted Story. Cancers 2022, 14, 4377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semb, H.; Christofori, G. The Tumor-Suppressor Function of E-Cadherin. Am. J. Human Genet. 1998, 63, 1588–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Tang, C. The Role of ARID1A in Tumors: Tumor Initiation or Tumor Suppression? Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 745187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, W.R. Rethinking Cancer. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi 2025, 47, 463–467. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Wang, S.C.; Wei, Y.; Luo, X.; Jia, Y.; Li, L.; Gopal, P.; Zhu, M.; Nassour, I.; Chuang, J.-C.; et al. Arid1a Has Context-Dependent Oncogenic and Tumor Suppressor Functions in Liver Cancer. Cancer Cell 2017, 32, 574–589.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Chuang, J.-C.; Kanchwala, M.; Wu, L.; Celen, C.; Li, L.; Liang, H.; Zhang, S.; Maples, T.; Nguyen, L.H.; et al. Suppression of the SWI/SNF Component Arid1a Promotes Mammalian Regeneration. Cell Stem Cell 2016, 18, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Liu, X.; Yu, J.; Hua, F.; Hu, Z. Antioxidant N-Acetylcysteine Attenuates Hepatocarcinogenesis by Inhibiting ROS/ER Stress in TLR2 Deficient Mouse. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e74130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piskounova, E.; Agathocleous, M.; Murphy, M.M.; Hu, Z.; Huddlestun, S.E.; Zhao, Z.; Leitch, A.M.; Johnson, T.M.; DeBerardinis, R.J.; Morrison, S.J. Oxidative Stress Inhibits Distant Metastasis by Human Melanoma Cells. Nature 2015, 527, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giudice, E.; Gentile, M.; Salutari, V.; Ricci, C.; Musacchio, L.; Carbone, M.V.; Ghizzoni, V.; Camarda, F.; Tronconi, F.; Nero, C.; et al. PARP Inhibitors Resistance: Mechanisms and Perspectives. Cancers 2022, 14, 1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Wang, L.; Xing, Z.; Wang, F.; Cheng, X. Update on Combination Strategies of PARP Inhibitors. Cancer Control 2024, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, R.; Zhou, P.; Qin, S.; Li, J.; Xu, S.; Kang, M.; Zhang, Y. Evaluating the Efficacy of PARP Inhibitor in ARID1A-Deficient Colorectal Cancer: A Ex Vivo Study. Cancer Biomark. 2025, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stiegeler, N.; Garsed, D.W.; Au-Yeung, G.; Bowtell, D.D.L.; Heinzelmann-Schwarz, V.; Zwimpfer, T.A. Homologous Recombination Proficient Subtypes of High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer: Treatment Options for a Poor Prognosis Group. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1387281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.-C.; Li, T.; Tully, E.; Huang, P.; Chen, C.-N.; Oberdoerffer, P.; Gaillard, S.; Shih, I.-M.; Wang, T.-L. Temozolomide Sensitizes ARID1A -Mutated Cancers to PARP Inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2023, 83, 2750–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athar, A.; Ahmad, E.; Bera, P.; Nasar, M.A.; Imtiyaz, K.; Rizvi, M.M.A.; Saluja, S.S. Molecular Interplay of ARID1A in Gastrointestinal Cancers. Med. Oncol. 2025, 42, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alldredge, J.K.; Eskander, R.N. EZH2 Inhibition in ARID1A Mutated Clear Cell and Endometrioid Ovarian and Endometrioid Endometrial Cancers. Gynecol. Oncol. Res. Pract. 2017, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natu, A.; Verma, T.; Khade, B.; Thorat, R.; Gera, P.; Dhara, S.; Gupta, S. Histone Acetylation: A Key Determinant of Acquired Cisplatin Resistance in Cancer. Clin. Epigenet. 2024, 16, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Barge, A.; Parris, C.N. Combination Strategies with PARP Inhibitors in BRCA-Mutated Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Overcoming Resistance Mechanisms. Oncogene 2025, 44, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Sak, A.; Niedermaier, B.; Erol, Y.B.; Groneberg, M.; Mladenov, E.; Kang, M.; Iliakis, G.; Stuschke, M. Selective Vulnerability of ARID1A Deficient Colon Cancer Cells to Combined Radiation and ATR-Inhibitor Therapy. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 999626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irving, E.; Morcavallo, A.; Vohhodina-Tretjakova, J.; Beckett, A.L.; Jacques, M.P.; Evans, R.S.; Moss, J.I.; Staniszewska, A.D.; Forment, J.V. An Inducible BRCA1 Expression System with in Vivo Applicability Uncovers Activity of the Combination of ATR and PARP Inhibitors to Overcome Therapy Resistance. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.K.; Reckamp, K.; Yu, H.; Figlin, R.A. Akt Inhibitors in Clinical Development for the Treatment of Cancer. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2010, 19, 1355–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, C.; Wang, Z.; Yu, Y.; Han, Z.; Lu, J.; Pan, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; He, Y.; Wang, K.; et al. ARID1A Loss Sensitizes Colorectal Cancer Cells to Floxuridine. Neoplasia 2024, 58, 101069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hein, K.Z.; Stephen, B.; Fu, S. Therapeutic Role of Synthetic Lethality in ARID1A -Deficient Malignancies. J. Immunother. Precis. Oncol 2024, 7, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, C.G.; Sharma, S.; Santos, A.M.; Nikolakopoulos, K.-S.; Velentzas, A.D.; Völlmy, F.I.; Minia, A.; Pliaka, V.; Altelaar, M.; Wright, G.J.; et al. ARID1A-Induced Transcriptional Reprogramming Rewires Signalling Responses to Drug Treatment in Melanoma. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, I.; Naghi, L.; Yost, S.E.; Mortimer, J. Clinical Actionability of Molecular Targets in Multi-Ethnic Breast Cancer Patients: A Retrospective Single-Institutional Study. Mol. Diagn. Ther. 2025, 29, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneses Rêgo, A.C.; Araújo-Filho, I. Decoding PARP Inhibitor Resistance in Ovarian Cancer: Molecular Insights and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies. Int. J. Innov. Res. Med. Sci. 2024, 9, 652–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, N.; Malik, S.; Villanueva, K.E.; Urano, A.; Lu, X.; Von Figura, G.; Seeley, E.S.; Dawson, D.W.; Collisson, E.A.; Hebrok, M. Brg1 Promotes Both Tumor-Suppressive and Oncogenic Activities at Distinct Stages of Pancreatic Cancer Formation. Genes Dev. 2015, 29, 658–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.