Perceptions of Artificial Intelligence Among Gastroenterologists in Italy: A National Survey

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Development of the Survey Questionnaire

- -

- To identify the level of awareness of gastroenterologists regarding AI

- -

- To identify the level of usage of AI by gastroenterologists

- -

- To identify the concerns of gastroenterologists regarding the usage of AI

- -

- To identify differences by socio-demographic variables.

2.2. Distribution of Questionnaire and Collection of Data

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General Information and Demographic Data

3.2. Awareness, Current Usage, and Perception of AI Tools in Gastroenterology

3.3. Key Concerns and Barriers

3.4. Training and Education

3.5. Future Outlook

3.6. Subgroup Analyses by Socio-Demographic Differences

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Haug, C.J.; Drazen, J.M. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Clinical Medicine, 2023. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 1201–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, R.; Acosta, J.N.; Shakeri, Z.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Topol, E.J.; Rajpurkar, P. Randomised Controlled Trials Evaluating Artificial Intelligence in Clinical Practice: A Scoping Review. Lancet Digit. Health 2024, 6, e367–e373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maida, M.; Marasco, G.; Facciorusso, A.; Shahini, E.; Sinagra, E.; Pallio, S.; Ramai, D.; Murino, A. Effectiveness and Application of Artificial Intelligence for Endoscopic Screening of Colorectal Cancer: The Future Is Now. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2023, 23, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, C.; Spadaccini, M.; Mori, Y.; Foroutan, F.; Facciorusso, A.; Gkolfakis, P.; Tziatzios, G.; Triantafyllou, K.; Antonelli, G.; Khalaf, K.; et al. Real-Time Computer-Aided Detection of Colorectal Neoplasia During Colonoscopy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2023, 176, 1209–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangas-Sanjuan, C.; de-Castro, L.; Cubiella, J.; Díez-Redondo, P.; Suárez, A.; Pellisé, M.; Fernández, N.; Zarraquiños, S.; Núñez-Rodríguez, H.; Álvarez-García, V.; et al. Role of Artificial Intelligence in Colonoscopy Detection of Advanced Neoplasias: A Randomized Trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2023, 176, 1145–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, H.K.; Mori, Y.; Hassan, C.; Rizkala, T.; Radadiya, D.K.; Nathani, P.; Srinivasan, S.; Misawa, M.; Maselli, R.; Antonelli, G.; et al. Lack of Effectiveness of Computer Aided Detection for Colorectal Neoplasia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Nonrandomized Studies. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 22, 971–980.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OpenAI. ChatGPT (Mar 14 Version). 2023. Available online: https://chat.openai.com (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Pugliese, N.; Wai-Sun Wong, V.; Schattenberg, J.M.; Romero-Gomez, M.; Sebastiani, G.; Aghemo, A.; Castera, L.; Hassan, C.; Manousou, P.; Miele, L.; et al. Accuracy, Reliability, and Comprehensibility of ChatGPT-Generated Medical Responses for Patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 22, 886–889.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, R.-C.; Liu, X.; Lai, Y.-K.; Hu, Y.-X.; Deng, H.; Zhou, H.-Q.; Lu, N.-H.; Zhu, Y.; Hu, Y. Exploring the Performance of ChatGPT on Acute Pancreatitis-Related Questions. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Liao, F.; Zhao, J.; Zhu, C.; Hu, Y.; Li, Z. Exploring the Capacities of ChatGPT: A Comprehensive Evaluation of Its Accuracy and Repeatability in Addressing Helicobacter pylori-related Queries. Helicobacter 2024, 29, e13078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.-C.; Staller, K.; Botoman, V.; Pathipati, M.P.; Varma, S.; Kuo, B. ChatGPT Answers Common Patient Questions About Colonoscopy. Gastroenterology 2023, 165, 509–511.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leggett, C.L.; Parasa, S.; Repici, A.; Berzin, T.M.; Gross, S.A.; Sharma, P. Physician Perceptions on the Current and Future Impact of Artificial Intelligence to the Field of Gastroenterology. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2024, 99, 483–489.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, W.W.; Chia, K.Y.; Cheung, M.F.; Kee, K.M.; Lwin, M.O.; Schulz, P.J.; Chen, M.; Wu, K.; Ng, S.S.; Lui, R.; et al. Risk Perception, Acceptance, and Trust of Using AI in Gastroenterology Practice in the Asia-Pacific Region: Web-Based Survey Study. JMIR AI 2024, 3, e50525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maida, M.; Alrubaiy, L.; Bokun, T.; Bruns, T.; Castro, V.; China, L.; Conroy, G.; Trabulo, D.; Van Steenkiste, C.; Voermans, R.P.; et al. Current Challenges and Future Needs of Clinical and Endoscopic Training in Gastroenterology: A European Survey. Endosc. Int. Open 2020, 8, E525–E533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Minh Duc, N.T.; Luu Lam Thang, T.; Nam, N.H.; Ng, S.J.; Abbas, K.S.; Huy, N.T.; Marušić, A.; Paul, C.L.; Kwok, J.; et al. A Consensus-Based Checklist for Reporting of Survey Studies (CROSS). J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2021, 36, 3179–3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadhwa, V.; Alagappan, M.; Gonzalez, A.; Gupta, K.; Brown, J.R.G.; Cohen, J.; Sawhney, M.; Pleskow, D.; Berzin, T.M. Physician Sentiment Toward Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Colonoscopic Practice: A Survey of US Gastroenterologists. Endosc. Int. Open 2020, 8, E1379–E1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marano, L.; Verre, L.; Carbone, L.; Poto, G.E.; Fusario, D.; Venezia, D.F.; Calomino, N.; Kaźmierczak-Siedlecka, K.; Polom, K.; Marrelli, D.; et al. Current Trends in Volume and Surgical Outcomes in Gastric Cancer. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kader, R.; Baggaley, R.F.; Hussein, M.; Ahmad, O.F.; Patel, N.; Corbett, G.; Dolwani, S.; Stoyanov, D.; Lovat, L.B. Survey on the Perceptions of UK Gastroenterologists and Endoscopists to Artificial Intelligence. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2022, 13, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, N.; Chan, C.; Tan, J.L.; Chinnaratha, M.A.; Singh, R. Endoscopists’ Knowledge, Perceptions and Attitudes toward the Use of Artificial Intelligence in Endoscopy: A Systematic Review. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, L.H.S.; Ho, J.C.L.; Lai, J.C.T.; Ho, A.H.Y.; Wu, C.W.K.; Lo, V.W.H.; Lai, C.M.S.; Scheppach, M.W.; Sia, F.; Ho, K.H.K.; et al. Effect of Real-Time Computer-Aided Polyp Detection System (ENDO-AID) on Adenoma Detection in Endoscopists-in-Training: A Randomized Trial. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 22, 630–641.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biscaglia, G.; Cocomazzi, F.; Gentile, M.; Loconte, I.; Mileti, A.; Paolillo, R.; Marra, A.; Castellana, S.; Mazza, T.; Di Leo, A.; et al. Real-Time, Computer-Aided, Detection-Assisted Colonoscopy Eliminates Differences in Adenoma Detection Rate between Trainee and Experienced Endoscopists. Endosc. Int. Open 2022, 10, E616–E621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, P.; Wang, Z. Application Value of an Artificial Intelligence-Based Diagnosis and Recognition System in Gastroscopy Training for Graduate Students in Gastroenterology: A Preliminary Study. Wien. Med. Wochenschr. 2024, 174, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| N = 150 | |

|---|---|

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 38.3 ± 11.2 |

| Gender N, (%) | |

| -Male | 83 (55.3%) |

| -Female | 67 (44.7%) |

| Working position N, (%) | |

| -Gastroenterologist | 101 (67.3%) |

| -Trainee in Gastroenterology | 49 (32.7%) |

| Year of practice in Gastroenterology (median, IQR) | 6 (3–13) |

| Practice setting N, (%) | |

| -Academic | 82 (54.7%) |

| -Public non-academic | 56 (37.3%) |

| -Private | 12 (8.0%) |

| Geographic areas N, (%) | |

| -Northern Italy | 64 (42.7%) |

| -Central Italy | 26 (17.3%) |

| -Southern Italy | 60 (40.0%) |

| Awareness and familiarity with AI in Gastroenterology | |

| Have you ever heard of AI in Gastroenterology? N (%) | |

| -Yes | 149 (99.3%) |

| How much is your knowledge about AI in Gastroenterology) | |

| 1 to 10 (median, IQR) | 6 (5–8) |

| Current usage and perception of AI tools in Gastroenterology | |

| Do you currently use AI tools in Endoscopy? N (%) | |

| -Yes | 74 (49.3%) |

| Which AI endoscopic tool? * N (%) | |

| -Lesion detection (CADe) | 39 (52.7%) |

| -Lesion detection and characterization (CADe/CADx) | 43 (58.2%) |

| -AI in capsule endoscopy | 17 (23.0%) |

| -AI in endoscopic assessment in IBD | 1 (1.4%) |

| -AI in EUS | 1 (1.4%) |

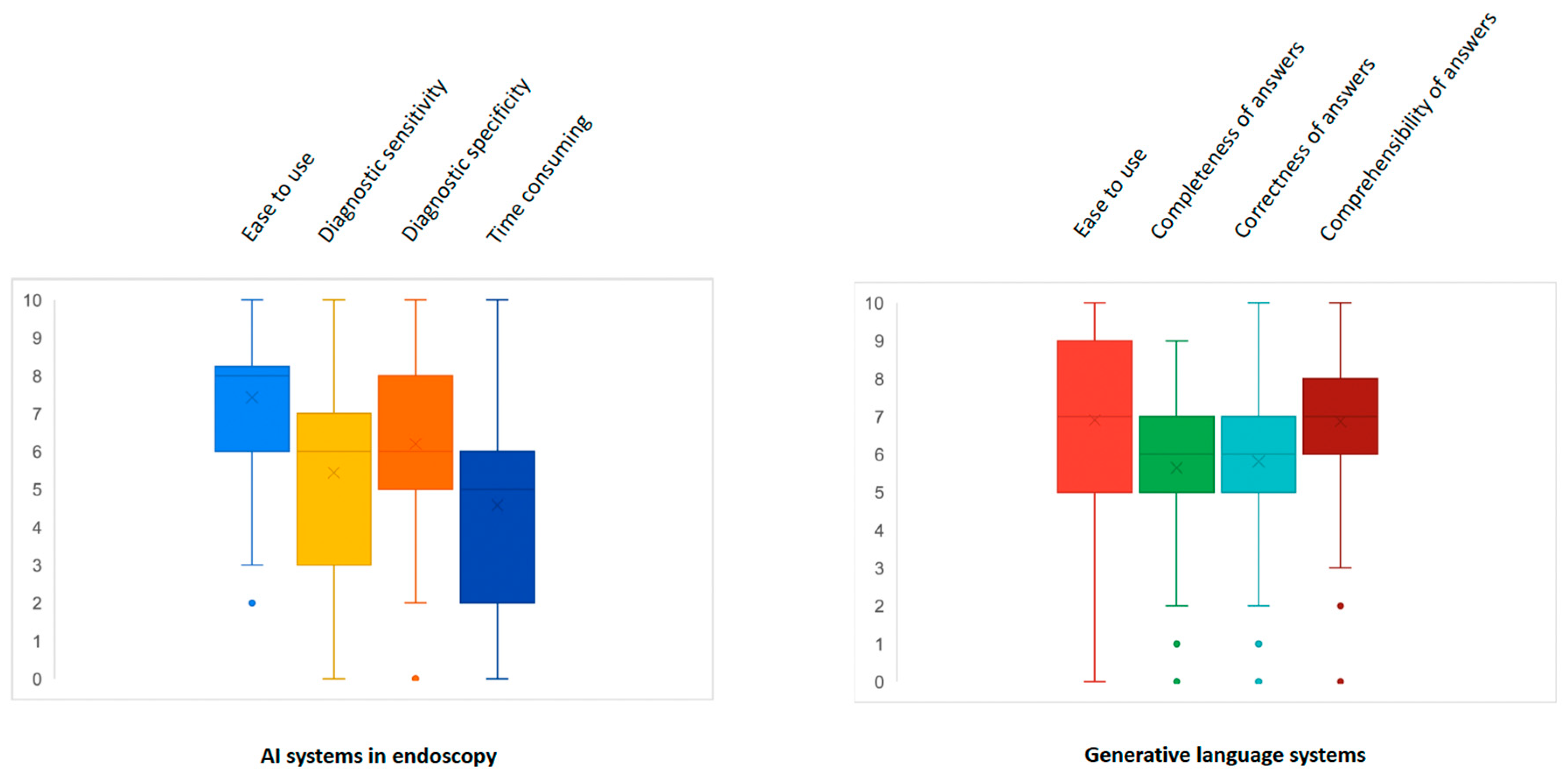

| What is your perception on AI systems in endoscopy? (median, IQR) | |

| -Ease to use (1 to 10) | 8 (6–8) |

| -Diagnostic sensitivity (1 to 10) | 6 (3–7) |

| -Diagnostic specificity (1 to 10) | 6 (5–8) |

| -Extension of procedure times (1 to 10) | 5 (2–6) |

| Do you currently use generative language systems? N (%) | |

| -Yes | 60 (40.0%) |

| For what purpose? * N (%) | |

| -Clinical purposes | 23 (35.9%) |

| -Informative purposes | 20 (31.3%) |

| -Scientific purposes | 38 (59.4) |

| -Other | 5 (3.3%) |

| In your opinion, generative language systems can be useful: * N (%) | |

| -To help doctors in managing patients | 63 (52.1%) |

| -To help patients acquire medical information | 39 (32.2%) |

| -To help researchers in writing scientific articles | 85 (70.2%) |

| What is your perception on generative language systems? (median, IQR) | |

| -Ease to use (1 to 10) | 7 (5–9) |

| -Completeness of answers (1 to 10) | 6 (5–7) |

| -Correctness of answers (1 to 10) | 6 (5–7) |

| -Comprehensibility of answers (1 to 10) | 7 (6–8) |

| Do you use AI systems in other areas of gastroenterology? N (%) | |

| -Yes | 23 (15.3%) |

| In which setting? * N (%) | |

| -Hepatology | 12 (50%) |

| -Pancreatology | 7 (29.2%) |

| -IBD | 12 (50%) |

| -Pathophysiology of digestive tract | 4 (16.7%) |

| -Gastrointestinal oncology | 5 (20.8%) |

| -Other | 3 (12.6%) |

| Barriers and concerns | |

| What do you think are the main barriers limiting the spread of AI in gastroenterology? * N (%) | |

| -Costs | 78 (52.0%) |

| -Difficulties in supply by hospitals | 75 (50.0%) |

| -Lack of knowledge or awareness of doctors | 75 (50.0%) |

| -Absence of guidelines on their use | 84 (56.0%) |

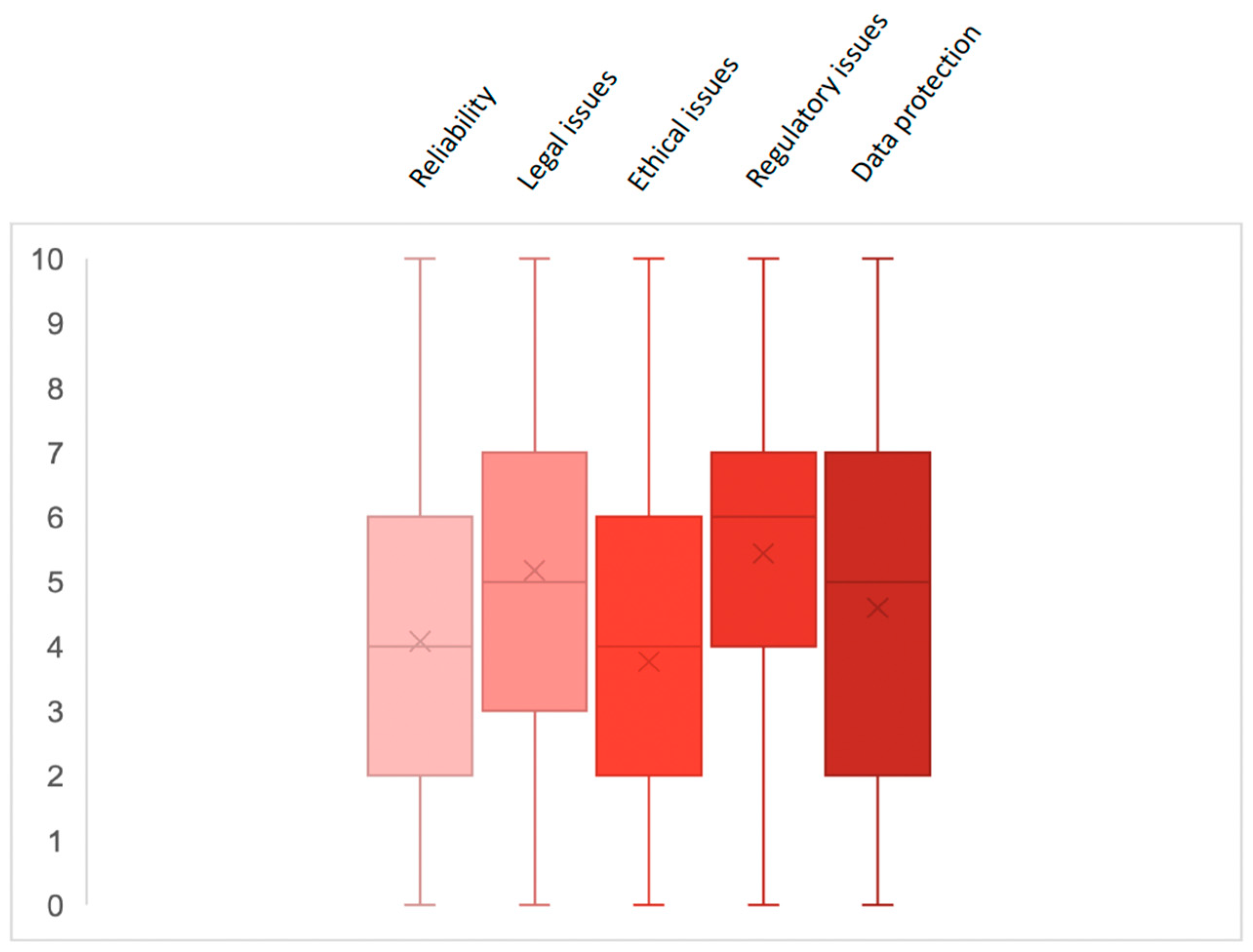

| How concerned are you about using AI systems in gastroenterology? Years (median, IQR) | |

| -Reliability (1 to 10) | 4 (2–6) |

| -Legal issues (1 to 10) | 5 (3–7) |

| -Ethical issues (1 to 10) | 4 (2–6) |

| -Regulatory issues (1 to 10) | 6 (4–7) |

| -Data protection (1 to 10) | 5 (2–7) |

| Training and education | |

| Do you think AI should be used in the training of young gastroenterologists? N (%) | |

| -Yes, I think it can facilitate and increase learning and training | 119 (79.3%) |

| -No, I think it could represent a handicap in the training processes | 24 (16.0%) |

| -I think its use is irrelevant for training purposes | 7 (4.7%) |

| What do you think are the most appropriate modalities to train young gastroenterologists on AI? * N (%) | |

| -Clinical practice in the room | 121 (80.7%) |

| -Hands-on courses | 97 (64.7%) |

| -Online courses | 49 (32.7%) |

| Future outlook | |

| How do you predict AI integration will impact endoscopic practice in the future? N (%) | |

| -Positive impact | 137 (91.3%) |

| -Negative impact | 2 (1.3%) |

| -Neutral impact | 11 (7.3%) |

| Are you optimistic about the potential of AI to improve endoscopic procedures? N (%) | |

| -Yes | 140 (93.3%) |

| Do you think AI will be easily integrated into clinical practice? N (%) | |

| -Yes | 121 (80.7%) |

| In how many years do you think AI will be integrated into clinical practice? Years (median, IQR) | 5 (5–10) |

| Men (N = 83) | Women (N = 67) | p | Age < 40 (N = 100) | Age ≥ 40 (N = 50) | p | Gastroenterologists (N = 101) | Trainees (N = 49) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Have you ever heard of AI in Gastroenterology? | |||||||||

| -Yes | 83 (100.0%) | 66 (98.5%) | 0.264 | 99 (99.0%) | 50 (100.0%) | 0.478 | 101 (100.0%) | 48 (98.0%) | 0.150 |

| How much is your knowledge about AI in Gastroenterology? | |||||||||

| 1 to 10 (median, IQR) | 7 (6–8) | 6 (5–7) | 0.036 | 6 (5–7) | 7 (6–8) | 0.005 | 7 (6–8) | 6 (4–7) | <0.001 |

| Do you currently use AI tools in Endoscopy? | |||||||||

| -Yes | 43 (51.8%) | 31 (46.3%) | 0.500 | 48 (48.0%) | 26 (52.0%) | 0.644 | 51 (50.5%) | 23 (46.9%) | 0.683 |

| What is your perception on AI systems in endoscopy? (median, IQR) | |||||||||

| -Ease to use (1 to 10) | 8 (7–9) | 7 (6–8) | 0.149 | 7 (6–8) | 8 (7–9) | 0.040 | 8 (7–9) | 7 (6–8) | 0.003 |

| -Diagnostic sensitivity (1 to 10) | 6 (3–7) | 6 (4–7) | 0.334 | 5.5 (4–7) | 7 (3–8) | 0.231 | 6 (3–7) | 5 (4–7) | 0.529 |

| -Diagnostic specificity (1 to 10) | 6 (5–8) | 6 (5–7) | 0.240 | 6 (5–8) | 6 (5–7) | 0.460 | 6 (5–8) | 6 (5–8) | 0.396 |

| -Extension of procedure times (1 to 10) | 5 (2–6) | 5 (3–7) | 0.060 | 5 (3–6) | 5 (2–6) | 0.847 | 5 (2–6) | 5 (3–6) | 0.960 |

| Do you currently use generative language systems? | |||||||||

| -Yes | 35 (42.2%) | 25 (37.3%) | 0.546 | 43 (43.0%) | 17 (34.0%) | 0.289 | 36 (35.6%) | 24 (49.0%) | 0.118 |

| What is your perception on generative language systems? (median, IQR) | |||||||||

| -Ease to use (1 to 10) | 7 (6–8) | 6 (5–9) | 0.301 | 7 (5–8) | 8 (5–9) | 0.682 | 7 (5–9) | 7 (5–8) | 0.661 |

| -Completeness of answers (1 to 10) | 6 (5–7) | 5 (5–7) | 0.773 | 6 (5–7) | 6 (5–8) | 0.059 | 6 (5–7) | 6 (5–7) | 0.665 |

| -Correctness of answers (1 to 10) | 6 (5–7) | 6 (5–7) | 0.553 | 5 (5–7) | 7 (5–8) | 0.013 | 6 (5–7) | 6 (5–7) | 0.403 |

| -Comprehensibility of answers (1 to 10) | 7 (6–8) | 7 (5–8) | 0.952 | 7 (6–8) | 8 (6–8) | 0.091 | 7 (6–8) | 7 (6–8) | 0.763 |

| How concerned are you about using AI systems in gastroenterology in terms of: | |||||||||

| -Reliability (1 to 10) | 4 (2–6) | 4 (3–5) | 0.759 | 4 (3–6) | 4 (2–5) | 0.301 | 4 (2–5) | 5 (3–6) | 0.063 |

| -Legal issues (1 to 10) | 5 (3–7) | 5 (3–7) | 0.842 | 5 (3–7) | 7 (3–8) | 0.064 | 6 (3–8) | 5 (3–7) | 0.305 |

| -Ethical issues (1 to 10) | 4 (2–6) | 4 (1–6) | 0.760 | 3 (1–5) | 5 (2–7) | 0.070 | 4 (2–7) | 3 (0–5) | 0.072 |

| -Regulatory issues (1 to 10) | 6 (5–7) | 6 (3–7) | 0.064 | 6 (4–7) | 7 (4–8) | 0.036 | 6 (4–7) | 5 (5–7) | 0.505 |

| -Data protection (1 to 10) | 5 (2–7) | 5 (2–7) | 0.584 | 5 (2–7) | 5 (2–7) | 0.520 | 5 (2–7) | 5 (2–7) | 0.488 |

| Do you think AI should be used in the training of young gastroenterologists? | |||||||||

| -Yes, I think it can facilitate and increase learning and training | 64 (77.1%) | 55 (82.1%) | 0.626 | 76 (76.0%) | 43 (86.0%) | 0.336 | 80 (79.2%) | 39 (79.6%) | 0.280 |

| -No, I think it could represent a handicap in the training processes | 14 (16.9%) | 10 (14.9%) | 19 (19.0%) | 5 (10.0%) | 18 (17.8%) | 6 (12.2%) | |||

| -I think its use is irrelevant for training purposes | 5 (6.0%) | 2 (3.0%) | 5 (5.0%) | 2 (4.0%) | 3 (3.0%) | 4 (8.2%) | |||

| How do you predict AI integration will impact endoscopic practice in the future? | |||||||||

| -Positive impact | 74 (89.2%) | 63 (94.0%) | 0.365 | 90 (90.0%) | 47 (94.0%) | 0.486 | 93 (92.1%) | 44 (89.8%) | 0.835 |

| -Negative impact | 2 (2.4%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.0%) | 1 (2.0%) | 1 (1.0%) | 1 (2.0%) | |||

| -Neutral impact | 7 (8.4%) | 4 (6.0%) | 9 (9.0%) | 2 (4.0%) | 7 (6.9%) | 4 (8.2%) | |||

| Are you optimistic about the potential of AI to improve endoscopic procedures? | |||||||||

| -Yes | 76 (91.6%) | 64 (95.5%) | 0.334 | 93 (93.0%) | 47 (94.0%) | 0.817 | 94 (93.1%) | 46 (93.9%) | 0.852 |

| Do you think AI will be easily integrated into clinical practice? | |||||||||

| -Yes | 70 (84.3%) | 51 (76.1%) | 0.205 | 77 (77.0%) | 44 (88.0%) | 0.108 | 81 (80.2%) | 40 (81.6%) | 0.835 |

| In how many years do you think AI will be integrated into clinical practice? Years (median, IQR) | 5 (5–8) | 5 (5–10) | 0.286 | 5 (5–10) | 5 (5–8) | 0.863 | 5 (5–10) | 5 (5–10) | 0.901 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maida, M.; Sferrazza, S.; Calabrese, G.; Marasco, G.; Vitello, A.; Furnari, M.; Boskoski, I.; Sinagra, E.; Facciorusso, A. Perceptions of Artificial Intelligence Among Gastroenterologists in Italy: A National Survey. Cancers 2025, 17, 1353. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17081353

Maida M, Sferrazza S, Calabrese G, Marasco G, Vitello A, Furnari M, Boskoski I, Sinagra E, Facciorusso A. Perceptions of Artificial Intelligence Among Gastroenterologists in Italy: A National Survey. Cancers. 2025; 17(8):1353. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17081353

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaida, Marcello, Sandro Sferrazza, Giulio Calabrese, Giovanni Marasco, Alessandro Vitello, Manuele Furnari, Ivo Boskoski, Emanuele Sinagra, and Antonio Facciorusso. 2025. "Perceptions of Artificial Intelligence Among Gastroenterologists in Italy: A National Survey" Cancers 17, no. 8: 1353. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17081353

APA StyleMaida, M., Sferrazza, S., Calabrese, G., Marasco, G., Vitello, A., Furnari, M., Boskoski, I., Sinagra, E., & Facciorusso, A. (2025). Perceptions of Artificial Intelligence Among Gastroenterologists in Italy: A National Survey. Cancers, 17(8), 1353. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17081353