Simple Summary

Colorectal cancer is one of the leading causes of cancer-related death worldwide. Prevention remains the most effective strategy to reduce mortality and mitigate its impact, but public participation in screening programs varies significantly. Advances in science and technology have provided new opportunities for action, but navigating the vast amount of information on early detection can be overwhelming for those interested in the topic. This review presents an overview of the current trends in clinical research related to secondary prevention of CRC.

Abstract

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths globally. The risk of disease increases with age, as most CRC patients are over 50 years old. Due to the progressive aging of societies in high-income countries, the problem of CRC will increase. This makes the development of new early detection methods and the implementation of effective screening programs crucial. Key areas of focus include raising population awareness about the importance of screening, educating high-risk populations, and improving and developing early diagnostic methods. The primary goal of this review is to provide a concise overview of recent trends and progress in CRC secondary prevention based on available information from clinical trials.

1. Introduction

1.1. Epidemiology and Risk Factors

The World Health Organization reports that colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer and the second leading cause of death among oncological diseases in the world [1]. It is important to know that the majority of colorectal cancers are sporadic when looking at epidemiological data, but the incidence rate is increasing. Because of this, it is important to take action in the field of early detection and screening.

Risk factors for the disease can be divided into two main categories: modifiable (such as lifestyle) and non-modifiable (such as genetic, family history, and age) risk factors [2]. The risk of developing colorectal cancer increases with age, and it most often occurs in people over 50 years of age. According to research, sex may play a role in the diagnosis of colorectal cancer. In a study by Regula et al., the male sex was identified as a predictive factor for detecting advanced cancer in screening. The remaining variables were an age over 49 and a family history of colorectal cancer [3].

There is an increased risk of developing colorectal cancer in people with a positive familial oncological history. The risk of CRC is much higher in people with a first-degree relative diagnosed with the disease before the age of 60 [4].

Modifiable risk factors related to one’s lifestyle primarily include diet and obesity. Eating a diet rich in saturated fat significantly increases the risk of developing CRC. Among other modifiable risk factors, smoking tobacco products increases the risk of developing the disease by 2–3 fold, and alcohol consumption also play an important role; daily consumption of 2–3 servings of alcohol increases the risk of CRC by 20% [5,6,7].

1.2. Screening Methods and Participation Rate

The American Cancer Society recommends screenings for people over the age of 45 and up to the age of 75. The decision to screen people aged 76–85 should be based on current health and past medical history, and people over the age of 85 should no longer be screened [8]. Adverse events related to colorectal cancer screening are few and result mainly from the use of minimally invasive colonoscopy [8]. One of the basic methods used in the early detection of colorectal cancer is colonoscopy. This method is relatively safe, but it is an invasive method. The incidence of perforation is less than 1/1000 cases, and in most cases, it is caused by polypectomy and results directly from the procedure [9].

In Europe, according to the recommendations of the European Commission, colorectal cancer screenings should cover people between 49 and 69 years of age. The basic recommended test is a quantitative stool immunochemical test (FIT) performed before the patient undergoes a colonoscopy or endoscopy. The FIT is a noninvasive method which can be performed at the patient’s home, which increases comfort and accessibility to tests and reduces the costs of maintaining the system [10].

The age range of those recommended for screening has decreased from previous recommendations. The majority of CRC cases are in the elderly, but there is an apparent increase in early-onset colorectal cancer (EO-CRC) in people under 50. This is particularly evident in high-income countries [11]. In the US, the incidence of CRC in people younger than 50 years has increased by 1.4% annually, and it has also been documented in most European countries; in the time period of 2004–2016, the annual percent changes in EO-CRC incidence were 7.9% in those aged 20–29, 4.9% in those aged 30–39, and 1.6% in those aged 40–49 [12]. In total, 30% of all cases can be attributed to hereditary cancer syndromes and various hamartomatous polyposis conditions [13]. The mechanism of this phenomenon is not known. Some researchers believe that it is caused by a diet high in fat, obesity, and low physical activity, but the exact mechanism is not known. According to the results obtained by Bretthauer et al. in a randomized study conducted in Poland, Sweden, and Norway with a sample of 84,585 people, the risk of CRC was lower in people who took part in colonoscopy screenings compared with people who did not receive invitation to colonoscopies. The risk of developing CRC in the study group after a 10 year follow-up was 0.98% versus 1.20% in the control group [14]. Screening is a cost-effective tool for reducing the burden of colorectal cancer. Most OECD countries have screening programs for select groups of cancers which can be effectively detected and treated at an early stage for targeted high-risk populations. An example of existing solutions for early detection of colorectal cancer is the Early Detection of Colorectal Cancer program conducted in Poland since 2000 as part of the National Cancer Prevention Program (NPZChN), with the current edition covering the years 2016–2024. The program assumed that colonoscopies would be performed on an opportunistic and population basis (by invitation every 10 years), but due to the availability of centers performing colonoscopy screenings and concerns about the examination itself, the assumptions of the program required changes (during the COVID-19 pandemic, only 10% of the eligible population took part). Since 2024, the FIT has been introduced into the screening program. The advantage of the test, apart from its high sensitivity and specificity, is its noninvasiveness and the lack of a need for prior preparation for the test. An invitation to an FIT combined with a reminder was addressed to people aged 50–69. If the patient ignored the invitation or obtained a negative result, then the patient would receive another invitation in 2 years. If the FIT was positive, then a colonoscopy was performed. As part of the program, colonoscopy screening was addressed to people aged 40–65 with a history of familial CRC, with the history taking itself becoming the responsibility of a GP or an occupational medicine physician. The Polish program also includes screening of people aged 25–49 from families with a genetic risk of hereditary CRC (in the case of HNPCC, colonoscopies should be repeated every 2–3 years, and in people with FAP, colonoscopies should be performed every year) [15].

According to OECD data, the population-based CRC screening program in Europe covers from 13.3% to 73% of the population of a given country [16]. Such a large difference indicates the need for further measures to improve participation and therefore early detection of colorectal cancer. Despite existing well-developed screening tools, only 4 out of 10 CRC cases are detected at an early stage [17]. According to studies, there are many reasons why people do not adhere to screenings. In a study by Gordon and Green, the main reasons for not following a doctor’s recommendations and participating in the FIT were discomfort, disgust, or embarrassment (59.6%); thinking it unnecessary (32.9%); fatalism or fear; and thinking they are too difficult to follow [18]. Richardson et al. provided examples such as low motivation and understanding of the screening procedure itself [19]. The fear of being diagnosed with cancer also plays a role [20]. For this reason, it is important to improve screening methods, mainly to identify people at high risk (e.g., individuals with a history of colorectal polyps, inflammatory bowel disease, familial adenomatous polyposis, or first-degree relatives) and to include them in screening programs.

The increasingly rapid progress of science, work on new diagnostic methods, and a large number of ongoing studies are positive phenomena for people involved in public health, but the amount of available information may be difficult to assimilate. For this reason, we decided to collect in one place the most important information from the point of view of public health, which concisely presents current trends in screening for colorectal cancer, which is one of the dominant cancers in the world.

The aim of this review is to present current trends in research in the area of screening for and early detection of colorectal cancer to provide information for researchers interested in secondary cancer prevention. The knowledge collected in our work can serve as a valuable source of information for people interested in the topic of secondary prevention of colorectal cancer.

2. Materials and Methods

The basis for the review was information collected from the world’s largest clinical trial registry (ClinicalTrial.Gov).

Three main categories were adopted and analyzed:

- (a)

- Population interventions aimed at increasing participation in screenings: All trials aimed at increasing participation in screenings were included in this category;

- (b)

- Educational interventions: We included trials and interventions aimed at increasing knowledge about risk factors, countermeasures, available diagnostic methods, health literacy among patients, and increasing knowledge about CRC, the functioning of existing solutions in an organization, and the operation of a health care system from the perspective of the healthcare provider,

- (c)

- Development, improvement, and application of early detection methods: This study included trials on the development of new diagnostic methods and procedures, improvement of existing methods and procedures, and improving the quality of methods and patient comfort.

The analysis included interventional studies, the main goal of which was early detection of colorectal cancer and in which the study group consisted of healthy people without symptoms. Studies relating to other cancers and studies targeting already-developed cancer were excluded from the analysis. In order to present the current trend in research, the search period was narrowed to 2019–2023. This analysis included studies which had a complete and active status by 31 December 2023.

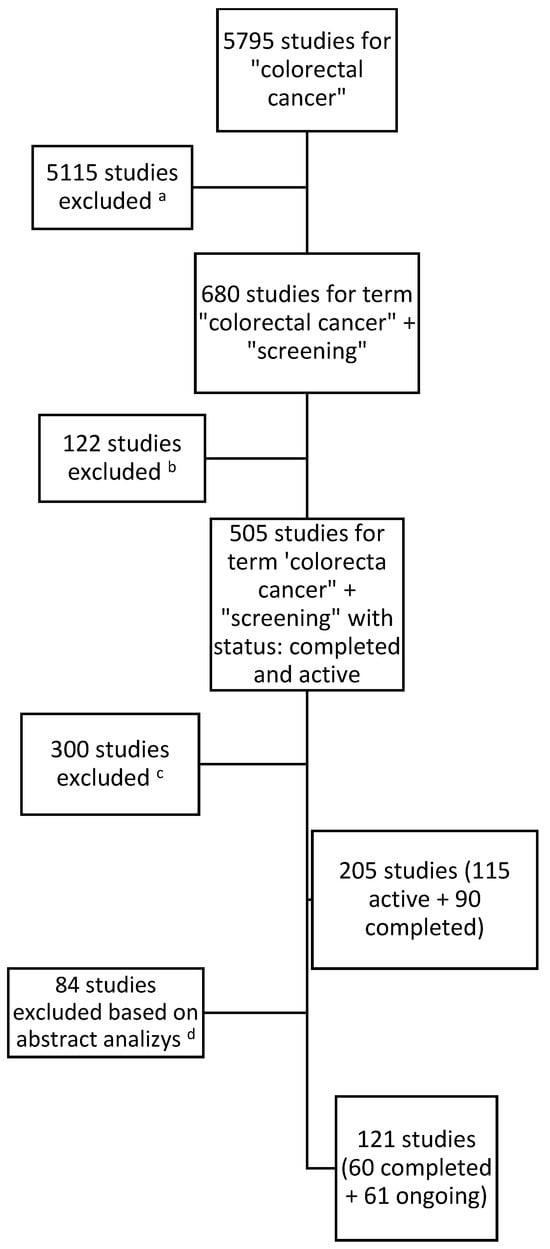

Below (Figure 1) is a process tree for including studies in the analysis:

Figure 1.

Results for searching and including studies in the analysis. a Studies with no connection with the keywords ‘screening’ or ‘early detection’. b Studies with the status terminated, suspended, withdrawn, or unknown in the database on the last day of the analyzed time period. c Studies which did not fit in the period of time from 1 January 2019 to 31 December 2023. d Studies which did not cover the topic of population screening (e.g., focused on patients with diagnosed CRC or methods of treatment and not methods of early detection or screening methods) and studies which, after reading the study information, did not fit into any category.

The first data search identified a total of 205 studies, of which 115 were active and 90 studies had been completed. As a result of the analysis of the study descriptions by two researchers, those studies which did not fall within the scope of the analysis after analyzing the texts were excluded. (The studies which did not fit into any category, did not consist of healthy participants, or focused on patients with cancer were excluded.) The researchers then compared the results and, by consensus, developed a list of studies for inclusion. Ultimately, 121 studies were included in the analysis.

Table 1 presents the results of the analysis of the collected material regarding research on early detection of colorectal cancer in the studied period.

Table 1.

Clinical trials on CRC screening completed and ongoing in the period from 1 January 2019 to 31 December 2023.

In the analyzed period, the number of studies aimed at colorectal cancer screenings has been systematically increasing, although in 2023, there was a slight decrease, perhaps due to the completion of previous studies. This indicates that researchers are actively interested in the growing problem of early detection of colorectal cancer. In the period from 1 January 2019 to 31 December 2023, 121 clinical trials were registered in the database (displayed in the database as of 15 June 2024). This number may vary slightly during other viewings. This is due to the editing of research statuses by their creators. However, this does not affect the overall picture of CRC screening research. The purpose of these trials fell into at least one of the three research categories assumed for the analysis. During the analyzed period, 60 studies were started and completed, obtaining the “completed” status, while 61 studies had the “ongoing” status as of the last day of the analyzed period (31 December 2023).

3. Colorectal Cancer Secondary Prevention

3.1. Population Interventions Aimed at Increasing Participation in Screenings

Research shows that in the case of colorectal cancer, a postal invitation combined with another form of reminder, mainly by telephone, translates into a higher participation rate compared with a postal invitation alone, ranging between 1 and 1.76 times greater. The results of some studies indicate that the inclusion of a face-to-face intervention, compared with an invitation alone, increases patient participation in screenings (RR = 1.29, 95% CI: 1.14–1.45). Two studies compared the use of prior notifications about the possibility of participating in CRC screenings (automatic text message notifications and a telephone call from a treatment facility) versus standard invitations (e.g., letter). Both studies showed similar results, indicating a 14% increase in adherence to screening recommendations in the case of the method with prior notification (RR = 1.14, 95% CI: 1.08–1.19) [23,34]. The clinical trials included in the analysis focused on adapting or modifying existing tools such as postal and telephone invitations and information materials with a proactive attitude (e.g., attaching a self-administered FIT kit (stool immunochemical test) to the invitation to the study) [22,24,42].

Studies fitting into the first category often occurred in combination with the other two groups, most often with the second category. An example of activities in this category is the study ‘Audio and Video Brochures for Increasing Colorectal Cancer Screening Among Adults Living in Appalachia’ (NCT05810714), which was aimed at a geographically excluded community. The basis of the study was information brochures in the form of audiovisual recordings aimed at increasing the percentage of people from the region taking part in colorectal cancer screening using an FIT kit. The audiovisual recordings were intended to be easier to understand for people with a limited level of health literacy, which in the end would translate into a higher return of FIT kits for testing [25]. The results of study NCT05810714 show that the return of FIT kits was higher among patients who were sent the kits in combination with a video brochure than in the group of patients who did not receive additional materials ((OR: 3.1; 95% CI: 1.02, 9.2; p = 0.046). However, the overall rate of recovery still requires further improvement, especially among a health-disadvantaged community [27]. Another ongoing study in 2021–2022 covering CRC and cervical cancer was ‘Multilevel Intervention Based on Colorectal Cancer (CRC) and Cervical Cancer Self-screening in Rural, Segregated Areas’ (NCT04471194), which was also aimed at a geographically excluded group: inhabitants of rural areas and areas inhabited by ethnic people. The study also included increasing the percentage of return of FIT kits [43]. An example of a study aimed at overall improvement in CRC screening uptake was the study ‘Health Service Intervention for the Improvement of Access and Adherence to Colorectal Cancer Screening’ (NCT04607291) [36]. The study used the Witness CARES Services protocol, which is used to optimize clinical services. Patients who are not prepared for a colonoscopy or stool testing receive educational materials, namely messages and videos with information about colon screening tests, electronically or by post and then make an appointment by phone within 2 weeks. Patients who want to undergo a colonoscopy examination receive assistance with the path (e.g., setting an appointment, preparing materials and the process, and transport). Patients who want to take part in a stool test are assisted by a coordinator who facilitates the test. Another study, ‘Optimizing Colorectal Cancer Screening Participation’ (NCT04292366), aimed to demonstrate the effectiveness of a three- and four-step invitation protocol compared with two-step procedures by combining pre-notifications and reminders. The iinitial notifications were sent to one of the groups 10 days before the intervention. Additionally, they received an invitation and one additional reminder. In the case of the second group, the notification interval was different, having an invitation and two reminders: one after 45 days and the other 3 months after the invitation. The third group received an initial notification, an invitation, a reminder 45 days later, and a reminder 3 months after the invitation. The control group received a regular invitation and one reminder 45 days after the invitation. In all cases, the reminders were delivered digitally [35]. The results from the study showed an increase in the overall participation rate of 2.9% (95% CI: 1.8–4.0), rising from 66.9% to 69.8%, and in the group with additional reminder by 2.7% (95% CI: 1.1; 4.2) among men and by 1.1% (95% CI: −0.3; 2.5) among women [44]. People from groups at risk of social inequalities in health resulting from ethnicity, race, or place of residence, which limit access to screenings, are included in the research area particularly often [38,41]. According to studies, the participation rate in CRC screenings was lower in the patients among the youngest age group, people with lower levels of education, and immigrants. Also, living in a rural area was associated with lower use of colonoscopies (ORs from 0.76 (95% CI: 0.56, 0.96) to 0.87 (95% CI: 0.81, 0.93)). Because of this, the communication tools used to improve adherence to screenings should be tailored to the participant group the system is trying to reach [30].

Most studies targeted the population. However, a different approach was demonstrated in the study ‘General Practitioners and Participation Rate in ColoRectal Cancer Screening’ (AMDepCCR) (NCT04492215). It focused on primary care physicians, on whom the CRC screening program in France is based. The aim of the study was to create a training program for GPs based on motivational interviewing (MI) techniques for the promotion of colorectal cancer screenings. Motivational interviewing is a directive, patient-centered counseling style for eliciting behavior changes by helping clients explore and resolve ambivalence [37].

3.2. Educational Interventions

The second category included studies aimed at increasing knowledge and education in the field of early detection of colorectal cancer. Health literacy was an issue of particular interest to researchers. The main goal of the activities was to improve the understanding and use of health information in the decision-making process and compliance with medical recommendations. Educational activities were also aimed at reducing patients’ fears and reluctance to undergo screenings, especially colonoscopies, and preparing appropriately for the tests. Research in the second category, including educational interventions, was mainly carried out in two groups: educational activities among patients, particularly those at high risk of developing colorectal cancer, and activities aimed at increasing the knowledge of healthcare providers about early detection and CRC risk factors, especially among primary care physicians [21,31,45,46].

These studies targeted select communities, such as ‘Screen to Save 2: Rural Cancer Screening Educational Intervention’ (NCT04414306), which was aimed at a select group of patients. The basis of the educational program was the Screen to Save 2 protocol implemented in two formats: a traditional form of contact via stationary contact and an online format. Education in both formats was based on a set of key messages including information about colorectal cancer, risk factors, prevention, screening recommendations, and screening options. Key messages from the National Cancer Institute have been adapted to the local NH and VT contexts, including information about local options for colorectal cancer screening [39]. Another study aimed at health education of a selected local community is the study ‘The PRIME-CRC Trial to Promote CRC Screening in Rural Communities’ (NCT04313114), which apart from increasing the level of participation in research also assumes health education and improving the health literacy of local communities with difficult access to health care [24]. The systematic review by Zhang et al. indicates insufficient health education as one of the barriers hindering the use of screenings [29]. Another goal of health education in CRC is to reduce fear of screenings, especially colonoscopies. An example of such a study is NCT05458986, which aimed to use video intervention to alleviate fear of colonoscopies. The results of other studies, such as Shahrbabaki et al., showed that education before a test reduces fear, as in the study group, the values were lower after educational intervention than before it (t = −6.01; p < 0.001) [47].

Some of the studies were aimed at selected ethnic groups, such as the ‘Educate, Assess Risk and Overcoming Barriers to Colorectal Screening Among African Americans’ study (NCT03640208), which was aimed at groups affected by health inequalities. African Americans, according to the data, have a higher mortality rate than all other social groups in the USA. The study involved the use of an educational session supported by visual aids, covering such issues as risk factors, what colorectal cancer is, prevention, and screening instructions [41].

The risk of developing CRC increases in people closely related to the patient. The aim of the ongoing study ‘Comparing the Effectiveness of Written vs. Verbal Advice for First Degree Relatives of Colorectal Cancer Patients’ (NCT06242197) is to evaluate the effectiveness of educating first-degree relatives about the risk of colorectal cancer in written and verbal form [48]. The study ‘Impact of Colorectal Cancer and Nutrition Education Program Among Minority Patients with Type 2 Diabetes’ (NCT05765214) aimed to develop an educational program aimed at increasing knowledge about CRC prevention among patients with type 2 diabetes. The authors wanted to answer questions about the factors related to CRC screening among diabetics and check the impact of patient-oriented health and nutrition education, tailored to the cultural factors in which they live, on the risk of developing CRC [45].

An example of a study aimed at reducing fear of colonoscopic screenings was the study ‘A Video Intervention to Decrease Patient Fear of Colonoscopy After a Positive Fecal Immunochemical Test’ (NCT05458986). The aim of the study was to compare an educational intervention using a video recording and an intervention without visual support. The starting point for the study was the low incidence of colonoscopy and positive FIT results. The preparation for the colonoscopy examination itself was also the subject of research. Appropriate patient preparation not only affects the course of the examination itself but also reduces concerns about the procedure and increases satisfaction [49]. An example of such a study is ‘An Interactive Video Educational Tool Improves the Quality of Bowel Preparation for Colonoscopy’ (NCT04491565), where one group received instructions in the form of verbal and written instructions and one group additionally had access to an interactive online recording [21].

3.3. Development and Application of Early Detection Methods

The registered clinical trials focused on two factors. (1) Some focused on blood tests based on the detection of circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA), including the circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) of colorectal cancer. According to CMS guidelines, a blood test for CRC, in order to be approved for use, must achieve the thresholds of 90% specificity and 74% sensitivity compared with the accepted standard, which is colonoscopy [40]. According to studies, ctDNA detection using liquid biopsy could be less invasive and safer than tissue biopsy [28,40]. The advantage of liquid biopsy is the short examination time (7–10 days compared with 2–3 weeks needed for classic histopathological examinations). In a case–control study by Brenne et al., based on 106 samples taken from people diagnosed with CRC and 106 control samples in which methylated ctDNA markers were detected, it was found that it is possible to detect ctDNA markers up to 2 years before clinical diagnosis in a population resembling screening conditions. This indicates the possibility of using ctDNA in early CRC detection programs [32]. An example of a study on a new blood cancer detection test which was active in the analyzed period is the prospective, multicenter PREEMPT CRC study (NCT04369053), which is using AI to create a platform that will integrate the signals (peripheral blood material) of tumor DNA, DNA of tumor microenvironment cells, and DNA of immune response cells (multiomics), which would improve detection sensitivity [50]. The starting point of the ‘Identification of New Diagnostic Protein Markers for Colorectal Cancer’ study (EXOSCOL01) (NCT04394572) was the release of extracellular vesicles by cancer cells containing proteins, mRNA, and DNA. These extracellular vesicles are of two types: exosomes (40–100 nm in diameter) formed by the budding of endosomal membranes and microvesicles (100–1000 nm in diameter) formed by budding of the cell membrane. Exosomes contain transmembrane proteins on their surface, called tetraspanins (CD9, CD63, and CD81). The research hypothesis assumed the use of these proteins as diagnostic markers in the detection of CRC [51]. The ‘A Multicenter Clinical Trial of Stool-based DNA Testing for Early Detection of Colon Cancer in China’ study (NCT04722055) focused on the development of a new screening kit which could replace FOBTs: the Human Multigene Methylation Detection Kit (fluorescent PCR). The tool is designed to qualitatively detect the methylation levels of multiple genes in human stool samples in vitro using quantitative methylation-specific PCR (qMSP) [26]. The results of another study, ‘Clinical Validation of An Optimized Multi-Target Stool DNA (Mt-sDNA 2.0) Test, for Colorectal Cancer Screening “BLUE-C”’ (NCT04144738), focused on clinical validation of optimized multi-target stool DNA. The sensitivity for colorectal cancer was 93.9% (95% CI: 87.1–97.7), and the specificity for advanced neoplasia was 90.6% (95% CI: 90.1–91.0). The sensitivities appeared to be higher with the next-generation test than with the FIT for the detection of colorectal cancers from stages I to III (92.7% versus 64.6%), proximal colorectal cancers (88.2% versus 58.8%), and distal colorectal cancers (96.9% versus 71.9%). Studies have indicated an aggregate sensitivity for the test of 65% (95% CI: 57–71%) [33,52,53]. A number of factors can contribute to the sensitivity and specificity of a genetic screening test. These include the DNA quality, molecular technology, and specific genetic changes chosen for analysis. The stool DNA test is based on the collection of a single stool sample, and there are no dietary restrictions, which affects the patient’s comfort. The DNA itself is derived from colon cells in the stool and is independent of the presence of blood in the stool, which is what FOBTs are based on. The potential of tests based on stool DNA lies in the detection of molecular changes occurring over a period of 7–10 years, which allows for earlier detection and better results [54,55]. (2) The other factor is imaging methods, namely MR colonography and CT capsules. The advantage of the first method over CT colonography is the lack of ionizing radiation. The second method uses a dissection-free X-ray imaging capsule which emits low-dose radiation beams using a rotating miniature electric motor. The results of the study by Gluck et al. for CT capsules indicate their potential practical application in the detection of CRC. A significant advantage of the tested method is its low invasiveness, low radiation (total exposure of patients was 0.03 ± 0.0007 mSv), and greater patient consent to the examination than in the case of a colonoscopy [50]. MR colonography has shown promising results in completed clinical trials as a tool helpful for detecting CRC at the level of 98.2%, with an overall sensitivity for detecting large polyps of 82% [56].

It should be noted that in order to prove that the pathologies detected by all of these methods are cancers, a colonoscopy should be performed with the collection of material for histopathological examination in order to identify the type of lesion detected. The ‘Computer Aided Detection of Polyps in Colonoscopy’ study (NCT04754347) checked the operation of the Skout device, which is a computer-aided tool for detecting polyps during colonoscopies in real time. The assumption of the study was the development of interval CRC as a result of missing polyps during a colonoscopy. The Skout tool was intended to improve the detection of adenomas in the study and thus reduce the number of cases of interval CRC. The system performs automated real-time analysis on endoscopic video data to identify potential polyps and produces an informational visual aid around the appropriate sections of the video frames on a display monitor [57]. Another system developed for polyp detection is the CADx system from the ‘Improving Optical Diagnosis of Colorectal Polyps Using CADx and BA-SIC’ study (NCT04349787), which aims to distinguish between benign and (pre-) malignant CRP by using state-of-the-art machine learning and archiving methods, namely deep learning textures [58].

4. Limitations

The included studies covered a five-year period (2019–2023) during the COVID-19 pandemic. Due to the epidemiological situation, the number of studies carried out during this period may differ from other periods. The need to focus on other research areas and other issues may have affected the current research shape. When looking at the results, readers should be aware that the duration of the research may have influenced its course and results. The second limitation is the lack of information on the financial effectiveness of individual tools. Financial efficiency was often not the subject of research. Additionally, the assessment is complicated by differences in the financing of health care systems around the world. Also, it is important to underline that as ClinicalTrial.Gov is the largest and one of the most-known databases, it does not include all of the research in the area of CRC screening and early detection.

5. Conclusions

The main trends in research on the early detection of colorectal cancer focus on improving tools to encourage participation in screening programs, as well as developing and enhancing tests for early detection. Universal screening remains one of the most effective tools for reducing the mortality and incidence of this disease. Current research is primarily directed at creating new methods based on circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA). However, the results from studies vary, indicating that the use of ctDNA in screening is still being explored. In particular, the high rate of false-positive results remains a significant challenge, warranting further investigation and solutions.

The second key area of research involves new techniques to improve the optical capabilities of endoscopic examinations, which aim to increase the accuracy of these tests. While these methods have shown promising results, their impact on screening costs and potential integration into nationwide screening programs still needs to be evaluated. Further simulations and calculations are required to assess their feasibility in large-scale settings.

It is also important to note that most research on colorectal cancer (CRC) is conducted in high-income countries, even though CRC is a global issue. In low-income countries, the disease burden is particularly high due to challenges in secondary prevention and delayed diagnosis.

Regarding strategies to increase participation in screenings, studies have consistently shown that social engagement strategies, such as multi-stage invitations in various audiovisual formats and tailored reminders, lead to higher patient participation. When combined with education on CRC risks, prevention, and testing, these solutions should be integrated as regular, active elements of the screening process.

Despite the availability of various screening tools and increasing health awareness, participation among individuals from at-risk groups remains low. Therefore, continued research into modern technologies is crucial to improving secondary prevention rates.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.P., M.P. and A.C.; formal analysis, O.P., M.P., A.D., D.M., D.K., E.C. and D.S.-M.; investigation, A.D., M.K., L.G., Z.S., K.M. and E.G.; methodology, O.P. and K.S.; supervision, A.C., A.D., E.B. and R.K.; visualization, O.P. and A.M.C.; writing—original draft, O.P., G.D., T.B. (Tomasz Banaś), T.B. (Tomasz Bandurski) and J.D.; writing—review and editing, O.P., S.G., P.P. and M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request from authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- WHO Colorectal Cancer. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/colorectal-cancer (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Roshandel, G.; Ghasemi-Kebria, F.; Malekzadeh, R. Colorectal Cancer: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Prevention. Cancers 2024, 16, 1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Regula, J.; Rupinski, M.; Kraszewska, E.; Polkowski, M.; Pachlewski, J.; Orlowska, J.; Nowacki, M.P.; Butruk, E. Colonoscopy in colorectal-cancer screening for detection of advanced neoplasia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 1863–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, D.P.; Burt, R.W.; Williams, M.S.; Haug, P.J.; Cannon-Albright, L.A. Population-based family history-specific risks for colorectal cancer: A constellation approach. Gastroenterology 2010, 138, 877–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Murphy, N.; Moreno, V.; Hughes, D.J.; Vodicka, L.; Vodicka, P.; Aglago, E.K.; Gunter, M.J.; Jenab, M. Lifestyle and dietary environmental factors in colorectal cancer susceptibility. Mol. Asp. Med. 2019, 69, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandic, M.; Li, H.; Safizadeh, F.; Niedermaier, T.; Hoffmeister, M.; Brenner, H. Is the association of overweight and obesity with colorectal cancer underestimated? An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2023, 38, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deptala, A. Epidemiologia, wskaźniki przeżycia, środowiskowe uwarunkowania rozwoju raka jelita grubego [Epidemiology, survival rates, environmental determinants of colorectal cancer development]. In Rak Jelita Grubego [Colorectal Cancer]; Deptala, A., Wojtukiewicz, M.Z., Eds.; Termedia: Poznan, Poland, 2017; pp. 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/colon-rectal-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/acs-recommendations.html (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Issa, I.A.; Noureddine, M. Colorectal cancer screening: An updated review of the available options. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 5086–5096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://cancer-screening-and-care.jrc.ec.europa.eu/en/ecicc/european-colorectal-cancer-guidelines?topic=283&usertype=282&updatef2=0 (accessed on 4 October 2024).

- Akimoto, N.; Ugai, T.; Zhong, R.; Hamada, T.; Fujiyoshi, K.; Giannakis, M.; Wu, K.; Cao, Y.; Ng, K.; Ogino, S. Rising incidence of early-onset colorectal cancer—A call to action. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 18, 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.; Pillai, A.B.; Omar, N.; Dima, D.; Harichand, S. Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer: Current Insights. Cancers 2023, 15, 3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, H.; Betel, D.; Abelson, J.S.; Zheng, X.E.; Yantiss, R.; Shah, M.A. Early-onset Colorectal Cancer is Distinct From Traditional Colorectal Cancer. Clin. Color. Cancer 2017, 16, 293–299.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretthauer, M.; Løberg, M.; Wieszczy, P.; Kalager, M.; Emilsson, L.; Garborg, K.; Rupinski, M.; Dekker, E.; Spaander, M.; Bugajski, M.; et al. Effect of Colonoscopy Screening on Risks of Colorectal Cancer and Related Death. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 1547–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deptala, A. Nowotwory dolnego odcinka przewodu pokarmowego [Cancers of the lower digestive tract]. In Onkologia. Podręcznik dla Studentów Medycyny. Pomoc Dydaktyczna dla Lekarzy Specjalizujących się w Onkologii [Oncology. Textbook for Medical Students. Teaching Aid for Doctors Specializing in Oncology]; Deptala, A., Stec, R., Smoter, M., Mackiewicz, J., Eds.; AsteriaMed: Gdansk, Poland, 2024; ISBN 9788366801547. [Google Scholar]

- Health at Glance: Europe 2020: State of Health in the EU Cycle. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/429ff2a5-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/429ff2a5-en (accessed on 6 March 2024).

- Colorectal Cancer Early Detection, Diagnosis, and Staging. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/colon-rectal-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging.html (accessed on 4 March 2024).

- Gordon, N.P.; Green, B.B. Factors associated with use and non-use of the Fecal Immunochemical Test (FIT) kit for Colorectal Cancer Screening in Response to a 2012 outreach screening program: A survey study. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Richardson, L.C.; King, J.B.; Thomas, C.C.; Richards, T.B.; Dowling, N.F.; Coleman King, S. Adults Who Have Never Been Screened for Colorectal Cancer, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2012 and 2020. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2022, 19, 220001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, B.B.; BlueSpruce, J.; Tuzzio, L.; Vernon, S.W.; Aubree Shay, L.; Catz, S.L. Reasons for never and intermittent completion of colorectal cancer screening after receiving multiple rounds of mailed fecal tests. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An Interactive Video Educational Tool Improves the Quality of Bowel Preparation for Colonoscopy. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04491565 (accessed on 27 June 2024).

- Colorectal Cancer Screening Based on Predicted Risk (PRESENT). Available online: https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05357508 (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Flatbush FHC Proactive Colorectal Cancer Screening and Navigation. Available online: https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05646355 (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- The PRIME-CRC Trial to Promote CRC Screening in Rural Communities. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04313114?cond=Colorectal%20Cancer&term=Screening&viewType=Table&aggFilters=status:act%20rec%20not&start=2019-01-01_2023-12-31&limit=100&rank=22 (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- Audio and Video Brochures for Increasing Colorectal Cancer Screening Among Adults Living in Appalachia. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05810714 (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- A Multicenter Clinical Trial of Stool-based DNA Testing for Early Detection of Colon Cancer in China. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04722055?cond=Colorectal%20Cancer&term=Screening&viewType=Table&aggFilters=status:com&start=2019-01-01_2023-12-31&limit=100&rank=86 (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Katz, M.L.; Shoben, A.B.; Newell, S.; Hall, C.; Emerson, B.; Gray, D.M.; Chakraborty, S.; Reiter, P.L. Video brochures in a mailed fecal immunochemical test outreach program provide cancer screening information in a user-friendly format for rural Appalachian community members. J. Rural Health 2024, 40, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, F.; Su, L.; Qian, C. Circulating tumor DNA: A promising biomarker in the liquidbiopsy of cancer. Oncotarget. 2016, 7, 48832–48841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Effect of Bowel Preparation Training Given to Patients Undergoing Colonoscopy (Training). Available online: https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT06159855 (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Ola, I.; Cardoso, R.; Hoffmeister, M.; Brenner, H. Utilization of colorectal cancer screening tests across European countries: A cross-sectional analysis of the European health interview survey 2018–2020. Lancet Reg. Health–Eur. 2024, 41, 100920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Direct Information to At-Risk Relatives (DIRECT). Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04197856 (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Brenne, S.S.; Madsen, P.H.; Pedersen, I.S.; Hveem, K.; Skorpen, F.; Krarup, H.; Giskeødegård, G.; Laugsand, E. Colorectal cancer detected by liquid biopsy 2 years prior to clinical diagnosis in the HUNT study. Br. J. Cancer 2023, 129, 861–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itzkowitz, S.H.; Jandorf, L.; Brand, R.; Rabeneck, L.; Schroy, P.C., III; Sontag, S.; Johnson, D.; Skoletsky, J.; Durkee, K.; Markowitz, S.; et al. Improved fecal DNA test for colorectal cancer screening. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2007, 5, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camilloni, L.; Ferroni, E.; Cendales, B.J.; Pezzarossi, A.; Furnari, G.; Borgia, P.; Guasticchi, G.; Rossi, P.G.; the Methods to increase participation Working Group. Methods to increase participation in organised screening programs: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Optimising Colorectal Cancer Screening Participation. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04292366?cond=Colorectal%20Cancer&term=Screening&viewType=Table&aggFilters=status:com&start=2019-01-01_2023-12-31&limit=100&rank=12 (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Health Service Intervention for the Improvement of Access and Adherence to Colorectal Cancer Screening. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04607291 (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- General Practitioners and Participation Rate in ColoRectal Cancer Screening (AMDepCCR). Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04492215?cond=Colorectal%20Cancer&term=Screening&viewType=Table&aggFilters=status:act%20rec%20not&start=2019-01-01_2023-12-31&limit=100&page=1&rank=36 (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Screening More Patients for Colorectal Cancer Through Adapting and Refining Targeted Evidence-Based Interventions in Rural Settings, SMARTER CRC (SMARTER CRC). Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04890054 (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Screen to Save 2: Rural Cancer Screening Educational Intervention. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04414306 (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Jensen, T.S.; Chin, J.; Evans, M.; Ashby, L.; Li, C.; Long, K. Decision Memo for Screening for Colorectal Cancer—Blood-Based Biomarker Tests (CAG-00454N), CMS 2021. Available online: https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/view/ncacal-decision-memo.aspx?proposed=N&NCAId=299 (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- Educate, Assess Risk and Overcoming Barriers to Colorectal Screening Among African Americans. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03640208 (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Test Up Now Education Program (TUNE-UP). Available online: https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04304001 (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Multilevel Intervention Based on Colorectal Cancer (CRC) and Cervical Cancer Self-Screening in Rural, Segregated Areas. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04471194?cond=Colorectal%20Cancer&term=Screening&viewType=Table&aggFilters=results:with,status:com&start=2019-01-01_2023-12-31&limit=100&rank=3 (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Larsen, M.B.; Hedelund, M.; Flander, L.; Andersen, B. The impact of pre-notifications and reminders on participation in colorectal cancer screening—A randomised controlled trial. Prev. Med. 2022, 164, 107229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Impact of Colorectal Cancer and Nutrition Education Program Among Minority Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05765214?cond=Colorectal%20Cancer&term=Screening&viewType=Table&aggFilters=status:act%20rec%20not&start=2019-01-01_2023-12-31&limit=100&rank=87 (accessed on 27 June 2024).

- Triantafillidis, J.K.; Vagianos, C.; Gikas, A.; Korontzi, M.; Papalois, A. Screening for colorectal cancer: The role of the primary care physician. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 29, e1–e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrbabaki, P.M.; Asadi, N.B.; Dehesh, T.; Nouhi, E. The Effect of a Pre-Colonoscopy Education Program on Fear and Anxiety of Patients: A Randomized Clinical Trial Study. Iran J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2022, 27, 554–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comparing the Effectiveness of Written vs Verbal Advice for First Degree Relatives of Colorectal Cancer Patients. Available online: https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT06242197 (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- A Video Intervention to Decrease Patient Fear of Colonoscopy After a Positive Fecal Immunochemical Test. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05458986?cond=Colorectal%20Cancer&term=Screening&viewType=Table&aggFilters=status:com&start=2019-01-01_2023-12-31&limit=100&rank=68 (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- Prevention of Colorectal Cancer Through Multiomics Blood Testing (PREEMPT CRC). Available online: https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04369053 (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- Identification of New Diagnostic Protein Markers for Colorectal Cancer (EXOSCOL01). Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04394572?cond=Colorectal%20Cancer&term=Screening&viewType=Table&aggFilters=status:com&start=2019-01-01_2023-12-31&limit=100&rank=84 (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- Imperiale, T.F.; Ransohoff, D.F.; Itzkowitz, S.H.; Turnbull, B.A.; Ross, M.E. Colorectal Cancer Study Group Fecal DNA versus fecal occult blood for colorectal-cancer screening in an average-risk population. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 2704–2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.; Wang, Y.M.; Yen, A.M.; Wong, J.M.; Lai, H.C.; Warwick, J.; Chen, T.H. Cost-effectiveness analysis of colorectal cancer screening with stool DNA testing in intermediate-incidence countries. BMC Cancer 2006, 6, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Richter, S. Fecal DNA screening in colorectal cancer. Can. J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 22, 631–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, E.A.; Richards, D.; Cohn, A.; Tummala, M.; Lapham, R.; Cosgrave, D.; Ghung, G.; Clement, J.; Goa, J.; Hunkapiller, N.; et al. Clinical validation of a targeted methylation-based multi-cancer early detection test using an independent validation set. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 1167–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medical Advisory Secretariat. Magnetic Resonance (MR) Colonography for Colorectal Cancer Screening: An Evidence-Based Analysis. Ont. Health Technol. Assess. Ser. 2009, 9, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Computer Aided Detection of Polyps in Colonoscopy. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04754347?cond=Colorectal%20Cancer&term=Screening&viewType=Table&aggFilters=status:com&start=2019-01-01_2023-12-31&limit=100&rank=95 (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Improving Optical Diagnosis of Colorectal Polyps Using CADx and BASIC. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04349787?cond=Colorectal%20Cancer&term=Screening&viewType=Table&aggFilters=status:com&start=2019-01-01_2023-12-31&limit=100&rank=83 (accessed on 20 August 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).