“We Just Get Whispers Back”: Perspectives of Primary and Hospital Health Care Providers on Between-Service Communication for Aboriginal People with Cancer in the Northern Territory

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Ethics Approval and Project Background

2.2. Research Team

2.3. Participants and Recruitment

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

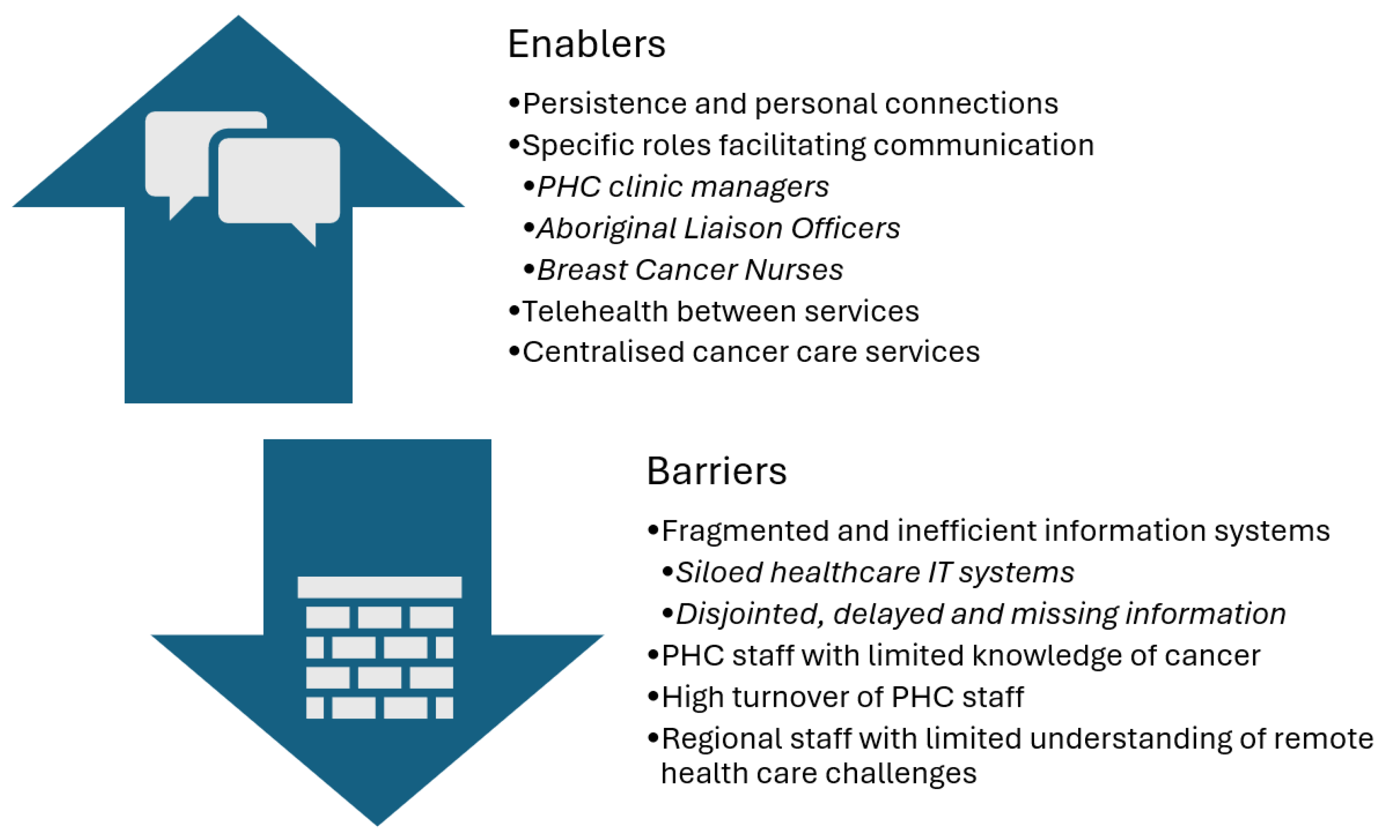

3.1. Communication Barriers

3.1.1. Fragmented and Inefficient Information Systems

“It’s very difficult because we use PCIS [Primary Care Information System] and the hospital doesn’t, we can’t see what’s in the hospital records and they can’t see what’s in ours… everyone uses different systems… we are so close to the border a lot of people here come over from [remote communities] in Queensland, and so it’s all that stuff to deal with too and that’s a whole different system as well”(Very Remote PHC RN HP017).

“We fax the referral off, and we will let [the patient] know when an appointment comes. And then, so the whole system can fall down because did we fax it off? Did it get received? Often not. Doesn’t seem to get received. If I look up on the computer, I can see if someone’s got an appointment for 10 months in the future but they don’t tell our practice manager until about 3 weeks out. The patient still doesn’t know. And so if we don’t get that notification, or it gets lost in the email trail, or we are busy, then the travel arrangements can’t be made in time”(Very Remote PHC GP HP043).

“They [the patient] go to their outpatient appointment. Do you get something back from the outpatient appointment? Quite often, particularly if it’s a routine following on thing… you don’t get anything back. I’ve rung up and outpatient people have been really helpful and they’ve looked in notes and said ‘Oh doctor has written see in 2 months’ or something like that. You don’t necessarily get a letter back from the outpatient appointment… So another letter comes—so you say, ‘Will you go to that again?’ And they [the patient] say ‘What for? I’ve been.’ And if you don’t really know why they’ve been, then you’ve got to start the whole process again”(Very Remote PHC RN HP032).

“A load of stuff happens [when the patient is in Darwin for diagnosis], and we never ever hear back what happens or and then they get sent back to community and then we go ‘oh crap what are we meant to be doing?’ Our patients… come back and there’s no plan, what’s happening? We don’t get a lot of feedback from town… Even when they get off the plane, when they are in community and we are like “wow are they back?” They were probably back a week ago and we haven’t sort of followed them up because we didn’t know they were back”(Remote PHC RN HP015).

“Do we ever see [the patient] again?… I don’t know, do we keep records of that? How do they go with getting some palliative care? If they need it in the community once they’ve gone back, is their pain well controlled? We let them go and then that’s it and I don’t know”(Regional Cancer Care Coordinator HP006).

3.1.2. PHC Staff with Limited Knowledge of Cancer

“I think probably as GPs [we] don’t understand the process because… like we get a letter. We understand it’s cancer. We understand that they are going to need A, B and C. But how that actually works… that’s not clear… The pathway isn’t clear, even to the doctors… It would be great to have two letters. The letter that says this is the diagnosis and please talk to your patient about this, and then the letter that says here’s the next steps.”(Very Remote PHC GP HP027).

3.1.3. High Turnover of PHC Staff

“Every time I phone a clinic, I’m talking to a different nurse, or a different GP who’s covering and I’ve got to go through the whole history of the patient because they don’t know who they are. Their time is limited. They’re only there for two weeks”(Remote Hospital Cancer Care Coordinator HP049).

“Locums, they are here for a short period of time and they kind of manage what walks through the door and what people bring to them you know. They are probably not in a position to be kind of searching through and actively seeking things…. When I started here there was stuff in the inbox from [2 years ago] and I think what happens, you just don’t know what to do with that. So I’ll leave it there so it doesn’t get lost but I don’t know what to do with it. And the next locum comes and goes, that’s from [2 years ago] that can’t be relevant…. Or you have an agency nurse that takes the recall off [for a routine mammogram or CT scan to monitor a lung lesion] because they didn’t think that the patient attended so the recall gets disappeared. I can’t remember a thousand people’s needs. You know there’s lots of steps along the way where it’s really easy for the non-urgent stuff to disappear.”(Very Remote PHC GP HP027).

3.1.4. Regional Staff with Limited Understanding of Remote Health Care Challenges

“I need advanced warning if you want a specialised test. I really do, ‘cause I only send bloods out on a Tuesday and a Thursday. And if it has to be frozen or something weird you need time to sort it out. Because I might not even have the tubes to be able to run that test…

We had a gentleman and… he got sent back with a pigtail drain in, with bags attached and having to change them…. we don’t have access to that stuff. You need to send it with him, enough to get him through, because we don’t have it. Or tell us what he needs before you send him back.”(Very Remote PHC RN HP017).

“She [the breast care nurse] thought just ringing someone up and telling someone to do this, it would magically happen. Whereas it actually meant somebody had to actually go out to an outstation and find this women and tell her, she had to come in and have her bloods done in time to catch the airplane. The bloods go on a plane and get results and [patient] has her appointment after that. And [the breast care nurse] didn’t understand”(Very Remote PHC RN HP032).

3.2. Enablers to Communication

3.2.1. Persistence and Personal Connections

“If there’s any paperwork I can forward to the clinic, I will print them off, scan them and email them to the Community Health Clinic… If there’s a discharge summary, or some sort of follow-up letters, or anything I can find that I can have access to, I’ll send it off to them. It’s not my role to do that, but I do it… I feel there’s a need because I think communication between us and the community… I understand the isolation”(Regional Cancer Centre ALO HP007).

3.2.2. Specific Roles Facilitating Communication

3.2.3. Telehealth Between Services

3.2.4. Centralised Cancer Care Service

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACCHS | Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services |

| AHP | Aboriginal Health Practitioner |

| ALO | Aboriginal Liaison Officer |

| ASGS | Australian Statistical Geography Standard |

| AWCCC | Alan Walker Cancer Care Centre |

| BCN | Breast Cancer Nurses |

| GP | General Practitioner |

| IT | Information Technology |

| MDT | Multidisciplinary Team Meeting |

| NT | Northern Territory |

| OCP | Optimal Care Pathway |

| PHC | Primary Health Care |

| RMO | Resident Medical Officer |

| RN | Registered Nurse |

References

- Moore, S.P.; Antoni, S.; Colquhoun, A.; Healy, B.; Ellison-Loschmann, L.; Potter, J.D.; Garvey, G.; Bray, F. Cancer incidence in indigenous people in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the USA: A comparative population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 1483–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, J.; Rumbold, A.; Zhang, X.; Condon, J. Incidence, aetiology, and outcomes of cancer in Indigenous peoples in Australia. Lancet Oncol. 2008, 9, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northern Territory Health. Cancer in the Northern Territory, 1991–2019. Available online: https://health.nt.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/1171875/cancer-in-the-nt-1991-to-2019.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Zhao, Y.; Chondur, R.; Li, S.; Burgess, P. Mortality Burden of Disease and Injury in the Northern Territory 1999–2018. Available online: https://health.nt.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/1149461/Mortality-burden-of-disease-and-injury-in-the-Northern-Territory-1999-2018.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2023).

- Boyd, R.; Charakidis, M.; Burgess, C.P.; Dugdale, S.; Castillon, C.; Sutandar, D.; Wright, A. Improved cancer survival in the Northern Territory: Identifying progress and disparities for Aboriginal peoples, 1991–2020. Med. J. Aust. 2025, 222, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahid, S.; Teng, T.K.; Bessarab, D.; Aoun, S.; Baxi, S.; Thompson, S.C. Factors contributing to delayed diagnosis of cancer among Aboriginal people in Australia: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.P.; Green, A.C.; Bray, F.; Garvey, G.; Coory, M.; Martin, J.; Valery, P.C. Survival disparities in Australia: An analysis of patterns of care and comorbidities among indigenous and non-indigenous cancer patients. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Indigenous Australians Agency; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Measure 3.04 Early Detection and Early Treatment. Available online: https://www.indigenoushpf.gov.au/Measures/3-04-Early-detection-early-treatment (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Northern Territory Department of Treasury and Finance. Northern Territory Economy. Available online: https://nteconomy.nt.gov.au/population (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Anderson, K.; Diaz, A.; Parikh, D.R.; Garvey, G. Accessibility of cancer treatment services for Indigenous Australians in the Northern Territory: Perspectives of patients and care providers. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ugalde, A.; Blaschke, S.; Boltong, A.; Schofield, P.; Aranda, S.; Phipps-Nelson, J.; Chambers, S.K.; Krishnasamy, M.; Livingston, P.M. Understanding rural caregivers’ experiences of cancer care when accessing metropolitan cancer services: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e028315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimison, P.; Phillips, F.; Butow, P.; White, K.; Yip, D.; Sardelic, F.; Underhill, C.; Tse, R.; Simes, R.; Turley, K.; et al. Are visiting oncologists enough? A qualitative study of the needs of Australian rural and regional cancer patients, carers and health professionals. Asia-Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 9, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horrill, T.; Lavoie, J.; Martin, D.; Schultz, A. Places & spaces: A critical analysis of cancer disparities and access to cancer care among First Nations Peoples in Canada. Witn. Can. J. Crit. Nurs. Discourse 2020, 2, 104–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kripalani, S.; LeFevre, F.; Phillips, C.O.; Williams, M.V.; Basaviah, P.; Baker, D.W. Deficits in Communication and Information Transfer Between Hospital-Based and Primary Care Physicians: Implications for Patient Safety and Continuity of Care. JAMA 2007, 297, 831–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, P.; Vandijck, D.; Degroote, S.; Peleman, R.; Verhaeghe, R.; Mortier, E.; Hallaert, G.; Van Daele, S.; Buylaert, W.; Vogelaers, D. Communication in healthcare: A narrative review of the literature and practical recommendations. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2015, 69, 1257–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valery, P.C.; Bernardes, C.M.; de Witt, A.; Martin, J.; Walpole, E.; Garvey, G.; Williamson, D.; Meiklejohn, J.; Hartel, G.; Ratnasekera, I.U. Are general practitioners getting the information they need from hospitals and specialists to provide quality cancer care for Indigenous Australians? Intern. Med. J. 2020, 50, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.J.; Binz-Scharf, M.; D’Agostino, T.; Blakeney, N.; Weiss, E.; Michaels, M.; Patel, S.; McKee, M.D.; Bylund, C.L. A mixed-methods examination of communication between oncologists and primary care providers among primary care physicians in underserved communities. Cancer 2015, 121, 908–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dossett, L.A.; Hudson, J.N.; Morris, A.M.; Lee, M.C.; Roetzheim, R.G.; Fetters, M.D.; Quinn, G.P. The primary care provider (PCP)-cancer specialist relationship: A systematic review and mixed-methods meta-synthesis. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2017, 67, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivers, B.M.; Rivers, D.A. Enhancing cancer care coordination among rural residents: A model to overcome disparities in treatment. Med. Care 2022, 60, 193–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passwater, C.; Itano, J. Care Coordination: Overcoming barriers to improve outcomes for patients with hematologic malignancies in rural settings. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2018, 22, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Witt, A.; Matthews, V.; Bailie, R.; Valery, P.C.; Adams, J.; Garvey, G.; Martin, J.H.; Cunningham, F.C. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients’ cancer care pathways in Queensland: Insights from health professionals. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2022, 33, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, R.; Micklem, J.; Yerrell, P.; Banham, D.; Morey, K.; Stajic, J.; Eckert, M.; Lawrence, M.; Stewart, H.B.; Brown, A.; et al. Aboriginal experiences of cancer and care coordination: Lessons from the Cancer Data and Aboriginal Disparities (CanDAD) narratives. Health Expect. 2018, 21, 927–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rankin, A.; Baumann, A.; Downey, B.; Valaitis, R.; Montour, A.; Mandy, P. The Role of the Indigenous Patient Navigator: A Scoping Review. Can. J. Nurs. Res. 2022, 54, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, E.V.; Thackrah, R.D.; Thompson, S.C. Improving Access to Cancer Treatment Services in Australia’s Northern Territory—History and Progress. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomino, H.; Peacher, D.; Ko, E.; Woodruff, S.I.; Watson, M. Barriers and Challenges of Cancer Patients and Their Experience with Patient Navigators in the Rural US/Mexico Border Region. J. Cancer Educ. 2017, 32, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crabtree-Ide, C.; Sevdalis, N.; Bellohusen, P.; Constine, L.S.; Fleming, F.; Holub, D.; Rizvi, I.; Rodriguez, J.; Shayne, M.; Termer, N.; et al. Strategies for Improving Access to Cancer Services in Rural Communities: A Pre-implementation Study. Front. Health Serv. 2022, 2, 818519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coombs, N.C.; Campbell, D.G.; Caringi, J. A qualitative study of rural healthcare providers’ views of social, cultural, and programmatic barriers to healthcare access. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varilek, B.M.; Mollman, S. Healthcare professionals’ perspectives of barriers to cancer care delivery for American Indian, rural, and frontier populations. PEC Innov. 2024, 4, 100247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrowes, S.; Seyoum Alemu, H.; Khokhar, N.; McMillian, G.; Hamade, S.; Dmitriyev, R.; Pham, K.; Whitney, S.; Galew, B.; Mahmoud, E.; et al. Coordinating under constraint: A qualitative study of communication and teamwork along Ethiopia’s cervical cancer care continuum. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, L.; Campbell, N.C.; Kiehlmann, P.A. Providing cancer services to remote and rural areas: Consensus study. Br. J. Cancer 2003, 89, 821–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, J.; Cassim, S.; Rolleston, A.; Chepulis, L.; Hokowhitu, B.; Keenan, R.; Wong, J.; Firth, M.; Middleton, K.; Aitken, D.; et al. Hā Ora: Secondary care barriers and enablers to early diagnosis of lung cancer for Māori communities. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Witt, A.; Matthews, V.; Bailie, R.; Garvey, G.; Valery, P.C.; Adams, J.; Martin, J.H.; Cunningham, F.C. Communication, collaboration and care coordination: The three-point guide to cancer care provision for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. Int. J. Integr. Care 2020, 20, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, E.V.; Dugdale, S.; Connors, C.M.; Garvey, G.; Thompson, S.C. “A Huge Gap”: Health Care Provider Perspectives on Cancer Screening for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People in the Northern Territory. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Values and Ethics: Guidelines for Ethical Conduct in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Research; National Health and Medical Research Council: Canberra, Australia, 2003.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Remoteness Areas: Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS) Edition 3. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/standards/australian-statistical-geography-standard-asgs-edition-3/jul2021-jun2026/remoteness-structure/remoteness-areas (accessed on 21 September 2024).

- Northern Territory (NT) Primary Health Network (PHN) Map—Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS) Remoteness area. Department of Health Disability and Ageing: Canberra, Australia, 2025. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2021/03/northern-territory-nt-primary-health-network-phn-map-australian-statistical-geography-standard-asgs-remoteness-area.png (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Green, J.; Willis, K.; Hughes, E.; Small, R.; Welch, N.; Gibbs, L.; Daly, J. Generating best evidence from qualitative research: The role of data analysis. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2007, 31, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinero de Plaza, M.A.; Gebremichael, L.; Brown, S.; Wu, C.J.; Clark, R.A.; McBride, K.; Hines, S.; Pearson, O.; Morey, K. Health System Enablers and Barriers to Continuity of Care for First Nations Peoples Living with Chronic Disease. Int. J. Integr. Care 2023, 23, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, T.P.; King, W.D.; Thibodeau, S.; Jalink, M.; Paulin, G.A.; Harvey-Jones, E.; O’Sullivan, D.E.; Booth, C.M.; Sullivan, R.; Aggarwal, A. Mortality due to cancer treatment delay: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2020, 371, m4087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.; Harrison, J.D.; Young, J.M.; Butow, P.N.; Solomon, M.J.; Masya, L. What are the current barriers to effective cancer care coordination? A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2010, 10, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farquhar, M.; Barclay, S.; Earl, H.; Grande, G.; Emery, J.; Crawford, R. Barriers to effective communication across the primary/secondary interface: Examples from the ovarian cancer patient journey (a qualitative study). Eur. J. Cancer Care 2005, 14, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Easley, J.; Miedema, B.; Carroll, J.C.; Manca, D.P.; O’Brien, M.A.; Webster, F.; Grunfeld, E. Coordination of cancer care between family physicians and cancer specialists. Importance Commun. 2016, 62, e608–e615. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasone, J.; Vukmirovic, M.; Brouwers, M.; Grunfeld, E.; Urquhart, R.; O’Brien, M.; Walker, M.; Webster, F.; Fitch, M. Challenges and insights in implementing coordinated care between oncology and primary care providers: A Canadian perspective. Curr. Oncol. 2017, 24, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Northern Territory Government. Acacia Digital Health System Progressing. Available online: https://digitalterritory.nt.gov.au/digital-stories/digital-story/acacia-digital-health-system-progressing (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Hislop, J. The Acacia ‘Shemozzle’: How an NT Health Software Upgrade Went So Wrong. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-02-01/nt-acacia-software-patients-rdh-ed-health-dcdd-/104879194 (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Jiwa, M.; Saunders, C.M.; Thompson, S.C.; Rosenwax, L.K.; Sargant, S.; Khong, E.L.; Halkett, G.; Sutherland, G.; Ee, H.C.; Packer, T.L. Timely cancer diagnosis and management as a chronic condition: Opportunities for primary care. Med. J. Aust. 2008, 189, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, G.; Berendsen, A.; Crawford, S.M.; Dommett, R.; Earle, C.; Emery, J.; Fahey, T.; Grassi, L.; Grunfeld, E.; Gupta, S.; et al. The expanding role of primary care in cancer control. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 1231–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancer Council. Optimal Care Pathways. Available online: https://www.cancer.org.au/health-professionals/optimal-cancer-care-pathways (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Deakin University. ECORRA OCP. Available online: https://ecorra.deakin.edu.au/project/ecorra-ocp/ (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Russell, D.J.; Zhao, Y.; Guthridge, S.; Ramjan, M.; Jones, M.P.; Humphreys, J.S.; Wakerman, J. Patterns of resident health workforce turnover and retention in remote communities of the Northern Territory of Australia, 2013–2015. Hum. Resour. Health 2017, 15, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.; Young, J.M.; Harrison, J.D.; Butow, P.N.; Solomon, M.J.; Masya, L.; White, K. What is important in cancer care coordination? A qualitative investigation. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2011, 20, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, E.V.; Lyford, M.; Parsons, L.; Mason, T.; Sabesan, S.; Thompson, S.C. “We’re very much part of the team here”: A culture of respect for Indigenous health workforce transforms Indigenous health care. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moffatt, J.J.; Eley, D.S. The reported benefits of telehealth for rural Australians. Aust. Health Rev. 2010, 34, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabesan, S.; Simcox, K.; Marr, I. Medical oncology clinics through videoconferencing: An acceptable telehealth model for rural patients and health workers. Intern. Med. J. 2012, 42, 780–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, A.; Caffery, L.J.; Gesesew, H.A.; King, A.; Bassal, A.-r.; Ford, K.; Kealey, J.; Maeder, A.; McGuirk, M.; Parkes, D. How Australian health care services adapted to telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic: A survey of telehealth professionals. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 648009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndwabe, H.; Basu, A.; Mohammed, J. Post pandemic analysis on comprehensive utilization of telehealth and telemedicine. Clin. eHealth 2024, 7, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, S.; Fitts, M.S.; Liddle, Z.; Bourke, L.; Campbell, N.; Murakami-Gold, L.; Russell, D.J.; Humphreys, J.S.; Mullholand, E.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Telehealth in remote Australia: A supplementary tool or an alternative model of care replacing face-to-face consultations? BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, S.; Durey, A.; Bessarab, D.; Aoun, S.M.; Thompson, S.C. Identifying barriers and improving communication between cancer service providers and Aboriginal patients and their families: The perspective of service providers. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2013, 13, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Zilva, S.; Walker, T.; Palermo, C.; Brimblecombe, J. Culturally safe health care practice for Indigenous Peoples in Australia: A systematic meta-ethnographic review. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2022, 27, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, I.; Green, C.; Bessarab, D. ‘Yarn with me’: Applying clinical yarning to improve clinician–patient communication in Aboriginal health care. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2016, 22, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.; Anderson, K.; Griffiths, K.; Garvey, G.; Cunningham, J. Understanding Indigenous Australians’ experiences of cancer care: Stakeholders’ views on what to measure and how to measure it. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, W.; Bond, C.; Hill, P.S. The power of talk and power in talk: A systematic review of Indigenous narratives of culturally safe healthcare communication. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2018, 24, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, E.V.; Lyford, M.; Holloway, M.; Parsons, L.; Mason, T.; Sabesan, S.; Thompson, S.C. “The support has been brilliant”: Experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients attending two high performing cancer services. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcusson-Rababi, B.; Anderson, K.; Whop, L.J.; Butler, T.; Whitson, N.; Garvey, G. Does gynaecological cancer care meet the needs of Indigenous Australian women? Qualitative interviews with patients and care providers. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Number of Staff (n = 50) | Proportion |

|---|---|---|

| Remoteness | ||

| Outer regional | 14 | 28% |

| Remote | 13 | 26% |

| Very Remote | 23 | 46% |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 38 | 76% |

| Male | 12 | 24% |

| Indigeneity | ||

| Aboriginal | 14 | 28% |

| Non-Aboriginal | 36 | 72% |

| Employer | ||

| Aged care | 1 | 2% |

| Cancer centre | 6 | 12% |

| Cancer support service | 1 | 2% |

| Hospital | 7 | 14% |

| Palliative care | 2 | 4% |

| Primary health care clinic | 33 | 66% |

| Finding | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Siloed Health Care IT Systems |

|

| Disjointed, delayed and missing information |

|

| PHC staff with limited knowledge of cancer |

|

| High turnover of PHC staff |

|

| Regional staff with limited understanding of remote health care challenges |

|

| Specific roles to enhance communication |

|

| Telehealth between services |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Taylor, E.V.; Elson, A.; Avishai, B.; Mayo, P.; Sanderson, C.; Thompson, S.C. “We Just Get Whispers Back”: Perspectives of Primary and Hospital Health Care Providers on Between-Service Communication for Aboriginal People with Cancer in the Northern Territory. Cancers 2025, 17, 3155. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193155

Taylor EV, Elson A, Avishai B, Mayo P, Sanderson C, Thompson SC. “We Just Get Whispers Back”: Perspectives of Primary and Hospital Health Care Providers on Between-Service Communication for Aboriginal People with Cancer in the Northern Territory. Cancers. 2025; 17(19):3155. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193155

Chicago/Turabian StyleTaylor, Emma V., Amy Elson, Bronte Avishai, Philip Mayo, Christine Sanderson, and Sandra C. Thompson. 2025. "“We Just Get Whispers Back”: Perspectives of Primary and Hospital Health Care Providers on Between-Service Communication for Aboriginal People with Cancer in the Northern Territory" Cancers 17, no. 19: 3155. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193155

APA StyleTaylor, E. V., Elson, A., Avishai, B., Mayo, P., Sanderson, C., & Thompson, S. C. (2025). “We Just Get Whispers Back”: Perspectives of Primary and Hospital Health Care Providers on Between-Service Communication for Aboriginal People with Cancer in the Northern Territory. Cancers, 17(19), 3155. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193155