Simple Summary

This review elucidates the manner in which artificial intelligence (AI) is transforming the diagnosis and staging of squamous cell carcinomas of the oropharynx (OPSCC). The review examines the potential utilization of AI in discerning the status of human papillomavirus (HPV) in OPSCCs. AI is primarily employed in the analysis of imaging data and the interpretation of histological specimens. While the outcomes are encouraging, they require further validation before they can be adopted in clinical practice.

Abstract

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is sexually transmitted and commonly widespread in the head and neck region; however, its role in tumor development and prognosis has only been demonstrated for oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (HPV-OPSCC). The aim of this review is to analyze the results of the most recent literature that has investigated the use of artificial intelligence (AI) as a method for discerning HPV-positive from HPV-negative OPSCC tumors. A review of the literature was performed using PubMed/MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library databases, according to PRISMA for scoping review criteria (from 2017 to July 2024). A total of 15 articles and 4063 patients have been included. Eleven studies analyzed the role of radiomics, and four analyzed the role of AI in determining HPV histological positivity. The results of this scoping review indicate that AI has the potential to play a role in predicting HPV positivity or negativity in OPSCC. Further studies are required to confirm these results.

1. Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is sexually transmitted and is a causal factor in the development of several cancers, including head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) [1].

HNSCC represents the seventh most common cancer globally, with an estimated 300,000 deaths per year [2]. It is expected that the incidence of this condition will increase by approximately 30% on a global scale, with the rise in HPV infection representing the primary driver of this trend [3,4].

HPV status (presence or absence of HPV infection in tumor cells) plays an important role in the prognosis of patients with oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC). Indeed, patients with HPV-positive OPSCC have superior survival rates compared to those with HPV-negative ones. Moreover, patients with HPV-positive OPSCC tend to exhibit distinct clinical and demographic features compared to those with HPV-negative OPSCC [1].

In consideration of the distinctions in oncogenesis and prognosis, the eighth edition of the AJCC (American Joint Committee on Cancer) categorizes OPSCC tumors as HPV-positive or HPV-negative, resulting in disparate staging between the two groups [5].

The treatment of OPSCC is primarily determined by surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy. These modalities may be employed individually or in combination.

Given that patients with HPV-positive OPSCC have a more favorable prognosis, recent studies have focused on de-intensifying treatment strategies for this group of patients, with the aim of reducing the adverse effects of treatment while maintaining high survival rates [1].

In recent years, there has been a marked increase in the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in the medical field, leading to significant modifications and enhancements in healthcare models [6].

The principal objective of AI is to enhance and augment human capabilities, facilitating the analysis of vast quantities of data in a relatively short timeframe for healthcare professionals. AI is a field of study that encompasses a number of sub-fields. Two of the most prominent of these are machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL). ML involves the use of algorithms that allow the program to improve autonomously, while DL learns by using very large numbers of multi-level connected processes and exposing these to a large number of examples [7,8,9].

To date, the primary application of AI in the healthcare sector has been in the analysis of radiological images. Recently, AI, through the utilization of DL and ML models, has also been employed in the domain of head and neck oncology, yielding favorable outcomes. One potential application is the recognition of HPV positivity in patients with OPSCC.

The aim of this review is to analyze the results of recent literature that has investigated the use of AI as a method for discerning HPV-positive from HPV-negative OPSCC tumors.

2. Materials and Methods

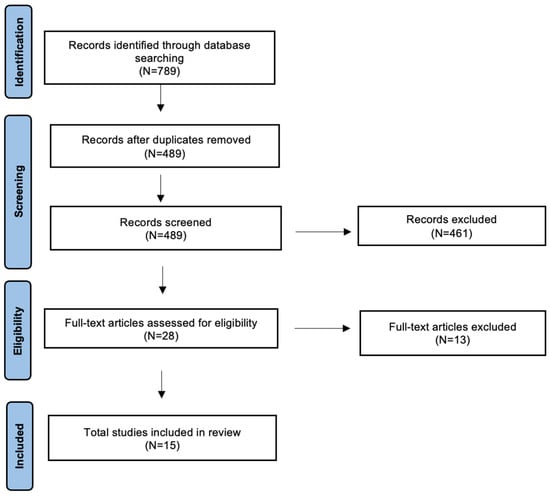

A detailed review of the English-language literature on AI in HPV-related OPSCC was performed using PubMed/MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library databases. The search period was from 2017 to July 2024, with the aim of selecting the most recent studies. The terms used were “oropharyngeal cancer”, “HPV related oropharyngeal cancer” or “HPV-OPSCC” and “Artificial Intelligence”, “AI”, “Deep Learning”, “DL”, “Machine Learning”, “ML” or “Radiomics”. The search yielded 789 candidate articles. The search was performed according to the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses” (PRISMA) for scoping review guidelines (Figure 1) [10]. The inclusion criteria applied were as follows: (i) publication date after 2017; (ii) studies aiming to use artificial intelligence to distinguish HPV-positive from HPV-negative OPSCC; and (iii) English language. Conference abstracts, case reports, retrospective studies, and publications written in a language different from English have been excluded. Two authors (AM and MM) have independently evaluated all titles, and relevant articles have been individuated according to inclusion/exclusion criteria; a senior author (AC) resolved any disagreements. At the end of the full-text review, 15 articles met the inclusion criteria [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25].

Figure 1.

The literature review was performed using PRISMA guidelines for a scoping review.

3. Results

This scoping review has included 15 articles in total, with 4063 patients analyzed overall. The articles were sourced from a range of geographical regions, with a particular prevalence from Europe and North America. The current application of AI to identify HPV positivity in OPSCCs encompasses two principal areas: (i) the utilization of radiomics in combination with various imaging techniques and (ii) histopathological analysis. These two macro-areas will, therefore, be analyzed separately in the following sections.

3.1. HPV and Radiomics

A review of the literature revealed that 11 of the 15 articles addressed the role of radiomics in the identification of HPV-positive OPSCCs [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. The findings of the review of the application of radiomics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Identified papers on radiomics: objective and major results.

Four articles based their analysis on computed tomography (CT) images, four on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-derived images, two on positron emission tomography (PET), and one on PET/CT.

The resulting analysis included 2460 patients with HPV-positive and 1216 patients with HPV-negative cancer. The area under the curve (AUC) values obtained from the various studies ranged between 0.71 and 0.95. The analysis does not identify a single imaging technique as being demonstrably superior to the others.

3.2. HPV and Histopathology

The results of the review process about HPV and histopathology are summarized in Table 2. This scoping review has included four articles analyzing the role of AI in determining HPV histopathological positivity in OPSCC [22,23,24,25]. Three of the articles originate from Europe, while the remaining one is from Japan.

Table 2.

Identified papers on AI and Histopathology.

Klein et al. [22] obtained an AUC of 0.80 from their model at 40× magnification. This result was compared with that obtained by experienced anatomic pathologists and was found to be superior. Furthermore, Fouard and colleagues found an accuracy of 91% in HPV detection [23]. The two further studies also showed an AUC higher than 0.80, reaching values even higher than 0.90 [24,25].

4. Discussion

In this scoping review, we have analyzed the role of AI in predicting HPV positivity in OPSCCs. Our analysis revealed that the primary applications of AI in this field are driven using radiomics and the analysis of histopathological samples.

AI is a technology designed to emulate the cognitive processes of humans, such as learning and problem-solving, using algorithms. The growth in scientific discovery and the integration of computer systems has led to AI becoming a significant tool in healthcare over the past decade [6]. AI has several applications in healthcare, including assisting professionals, educating young doctors, and assisting patients [6,26]. At present, its principal function is to facilitate the analysis of images, whether radiological or histological, by specialists. Its principal strength lies in its capacity for learning and training using DL or machine ML algorithms [6,9]. Furthermore, technological advancement has resulted in the development of language models that acquire their capabilities through the analysis of articles published on the Internet, thereby enabling them to learn from a vast amount of data [27,28]. One of the most extensively researched applications is its role in the field of oncology.

HPV is a DNA virus that infects the skin and mucous membranes. To date, more than 100 different subtypes have been classified. The cervix is the most extensively studied anatomical region with regard to the oncological role of HPV. The high-risk HPV subtypes include 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 68, 69, and 73 [29]. In the head and neck region, HPV infection also plays a causative role in the development of OPSCC, with an estimated prevalence of 40–60% [30,31]. Of the various HPV subtypes, HPV16 is responsible for 80–90% of HPV-positive OPSCC cases [32]. The most widely used method for diagnosing HPV-positive OPSCC is immunohistochemistry, which detects high expression of the cellular protein p16INK4a. This method is considered in the eighth edition of the AJCC [5].

According to the data from the present review, the majority of the included studies employ p16 as an HPV positivity marker. Nevertheless, the utility of p16 positivity as a marker for patients’ risk stratification is debated, given that single p16 positivity does not necessarily indicate HPV-driven carcinogenesis. Consequently, some studies implement HPV DNA detection by in situ hybridization to evaluate HPV positivity. Two of the studies analyzed this feature by immunohistochemistry and by in situ hybridization [22,24]. Furthermore, Fouad et al. [23] evaluated tissue microarrays stained by in situ hybridization using high-risk HPV genomic probes and a dedicated enzymatic procedure.

HPV-positive OPSCC most frequently affects males aged 40–55 years, with minimal exposure to tobacco and alcohol [32]. These tumors have a significantly more favorable prognosis than HPV-negative OPSCC. HPV-positive OPSCC is more prevalent in North America and Europe [3,4]. This geographical distribution is also corroborated by the provenance of the studies included in our review, as these areas are more frequently affected, and there is greater interest in the scientific field, resulting in a greater number of publications.

It is, therefore, of the utmost importance to analyze the presence or absence of HPV infection in OPSCCs, as this allows the provision of an appropriate treatment plan and prognosis for the patient. Indeed, numerous studies have assessed the potential benefits of reducing the intensity of treatment in HPV-positive OPSCC patients, with the aim of reducing the side effects of therapy and improving quality of life while maintaining similar survival rates [1].

In this context, where the accurate determination of HPV positivity in OPSCCs is of paramount importance, AI can play a pivotal role in assisting radiologists, anatomic pathologists, and oncologists in the staging of these patients. The first application of AI in medical imaging is in the field of histopathology, where it has been shown to achieve diagnostic accuracy in certain cases that is superior to that of human observers. DL is employed in pathological anatomy to facilitate the detection of tumors, determine grading, and search for biomarkers. Consequently, it is also employed in the search for HPV positivity in OPSCC [25]. Slides stained with hematoxylin and eosin are the most commonly used, with the images extracted and subjected to AI models at various magnifications. One of the principal constraints on the utility of DL models for the evaluation of histopathological images is the heterogeneity of the tissue present within a single slide. It is not uncommon for a slide to contain a substantial quantity of non-tumor tissue in addition to tumor tissue [33]. To address this limitation, two main supervisory approaches have been identified in the literature, namely, fully and weakly supervised. The former approach, in contrast to the latter, necessitates additional input from the pathologist, who is required to manually annotate the tumor area on each slide [34].

In 2021, two studies demonstrated that AI can achieve excellent results in the identification of HPV-positive tumors, with an AUC of 0.8 and an accuracy of over 90% [22,23].

Remarkably, both studies employed in situ hybridization techniques for the assessment of HPV positivity, in addition to p16.

Klein et al. [22] employed a training model based on the use of hematoxylin-eosin staining, which yielded promising results. This approach enabled the stratification of patients with a favorable prognosis more effectively than p16 alone or the p16 positive/HPV DNA positive dichotomy. Instead, Fouad et al. [23] used a mathematical morphology-based segmentation algorithm for in situ hybridization, achieving a level of accuracy of over 90%.

Recently, it was demonstrated that the CLAM (clustering-constrained attention-based multiple-instance learning) model, when incorporated with tumor annotation (Annot-CLAM), exceeded 0.9 at a magnification of 20× [25].

The utilization of AI can undoubtedly serve as a valuable asset for anatomic pathologists, potentially alleviating the considerable workload they are currently subjected to and enhancing the precision of their diagnostic capabilities.

Furthermore, the use of HPV-DNA testing with molecular techniques may be limited by factors such as poor tissue quality, sample processing, and results interpretation. In contrast, AI has the potential to provide relatively reliable results in a shorter time frame without being affected by DNA degradation, which can occur due to tissue fixation. Nevertheless, further research is required to evaluate the efficacy and feasibility of the clinical applications. These findings, particularly those concerning p16 and HPV DNA positivity, are very promising.

To date, the diagnostic method for HPV-positive OPSCC has entailed a biopsy and immunohistochemical analysis [5]. However, the oropharynx also encompasses regions that are not readily accessible, such as the base of the tongue, necessitating invasive surgical procedures to obtain the biopsy sample. Consequently, the patient is exposed to potential complications associated with the procedure, such as bleeding [35]. Additionally, the presence of coexisting inflammatory reactions may diminish immunohistochemical sensitivity [36].

A multitude of studies have sought to delineate imaging characteristics that may be predictive of HPV status in OPSCC. However, the considerable subjectivity inherent in image interpretation has rendered this approach largely inapplicable and has precluded the attainment of optimal results [37].

To overcome these limitations, radiomics, which aims to convert images into quantitative data that are independent of the operator, has been employed in recent years. Radiomics is a technique that analyzes large amounts of data and features extracted from imaging [38,39,40]. This approach has also been employed with moderate success in the identification of HPV-positive OPSCC. The analysis of the studies in this field reveals that CT and MRI represent the primary imaging techniques employed in radiomics modeling, with PET following as a distant second. In one of the four studies utilizing CT, sensitivity and specificity values of 75% and 72%, respectively, were identified in predicting HPV positivity, with an AUC of 0.95 [15]. The authors achieved excellent results through the analysis of CT images using a DL on a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) derived from the C3D pre-trained classification network on video. Both p16 and HPV DNA searches were performed to assess HPV positivity, obtaining information through the OPC-Radiomics and Head–Neck–Radiomics–HN1 datasets.

In subsequent studies, the predictive value and AUC were found to be lower, yet the results remained satisfactory. A total of 31 models have been created aiming to assess the HPV status by means of CT images. The most accurate model was the ‘ensemble subspace discriminant,’ which achieved a success rate of 78.7% [19]. Moreover, the potential of explicit artificial intelligence (XAI) in predicting HPV status based on CT images was recently assessed by training a CNN from scratch using OPC-Radiomics datasets. Subsequently, an XAI algorithm was employed for the evaluation of specific regions within the pre-treatment CTs ROI by an independent institutional database. The results obtained are still not suitable for routine clinical application. Additionally, HPV-positive tumors demonstrated a greater prevalence of intratumoral involvement, in contrast to HPV-negative tumors, which have mostly peripheral involvement [21].

Additionally, MRI yielded noteworthy outcomes in predicting HPV positivity, attaining an AUC of 0.87 [12]. Manual delineation of primary tumor volume was performed using T1W, T2W, T1W3D post-contrast, perfusion, and diffusion-weighted sequences. The images were analyzed using the open-source package PyRadiomics 2.2.0, which revealed a correlation between radiomic features suggestive of a smaller, rounder, more homogeneous, and more regular consistency and HPV positivity.

In 2023, Li et al. [20] demonstrated that integrating a multi-sequence-based image fusion model of the primary tumor and lymph nodes resulted in an AUC of 0.91 for predicting p16 positivity. The authors observed that the radiomic features analyzed (LHH first-order kurtosis, GLSZM size zone non-uniformity normalized, LHL GLSZM size zone non-uniformity normalized, LHH GLCM Id, LHH GLSZM small area emphasis, and LLH GLDM dependence entropy) revealed a homogeneous and regular distribution in HPV-positive tumors. Moreover, PET demonstrated favorable outcomes, albeit with a comparatively diminished impact compared to the other two techniques. HPV-positive tumors have a lower average SUVmax and a more homogeneous uptake than HPV-negative tumors [13,17].

It should be noted that the observation is limited by the small number of studies that have based radiomics on PET images. It is notable that the majority of cases analyzed were HPV-positive, with only a negligible proportion being HPV-negative. This imbalance may potentially represent a limitation for the majority of the studies analyzed.

The technique of radiomics is becoming increasingly prevalent in the staging of OPSCC. It can provide assistance to radiologists or nuclear physicians in the management and interpretation of images. Despite the favorable predictive outcomes of HPV-positive OPSCC, radiomics is not yet a substitute for biopsy and subsequent histopathological analysis.

Major drawbacks of this study are as follows: (i) the limited number of studies currently available in the literature, which has resulted in a restricted scope for this review; and (ii) the heterogeneity of the AI models employed, which has introduced challenges in conducting comparisons.

5. Conclusions

The results of this scoping review indicate that AI has the potential to play a role in predicting HPV positivity or negativity in OPSCC. At present, the utilization of AI models for the analysis of histopathological images yields more compelling outcomes than radiomics.

In the future, the advancement of technology, implementation of models, and standardization of protocols may facilitate the integration of AI in the management of patients with OPSCC. This could assist clinicians in managing vast amounts of data, enhance diagnostic accuracy, and facilitate the accurate staging of tumors, enabling the most appropriate therapeutic strategy to be proposed for these patients. Furthermore, radiomics may potentially supplant biopsy in the prediction of HPV positivity in OPSCCs.

The goal of AI in predicting HPV positivity in OPSCCs is (i) to facilitate a precise stratification of patients and (ii) to personalize treatments by minimizing potential side effects and enhancing patients’ quality of life.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M., M.M., A.C. and C.B.; methodology, A.M., M.M. and A.C.; formal analysis, A.M., M.M. and A.C.; investigation and data curation, A.M., M.M. and A.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M., M.M. and A.C.; writing—review and editing, F.S., S.P. and C.B.; supervision, A.C. and C.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Migliorelli, A.; Manuelli, M.; Ciorba, A.; Pelucchi, S.; Bianchini, C. The Role of HPV in Head and Neck Cancer. In Handbook of Cancer and Immunology; Rezaei, N., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.E.; Burtness, B.; Leemans, C.R.; Lui, V.W.Y.; Bauman, J.E.; Grandis, J.R. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2020, 6, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, C.-I.; Francoeur, A.A.; Kapp, D.S.; Caesar, M.A.P.; Huh, W.K.; Chan, J.K. Trends in Human Papillomavirus–Associated Cancers, Demographic Characteristics, and Vaccinations in the US, 2001–2017. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e222530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaturvedi, A.K.; Engels, E.A.; Pfeiffer, R.M.; Hernandez, B.Y.; Xiao, W.; Kim, E.; Jiang, B.; Goodman, M.T.; Sibug-Saber, M.; Cozen, W.; et al. Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 4294–4301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanoni, D.K.; Patel, S.G.; Shah, J.P. Changes in the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging of head and neck cancer: Rationale and implications. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2019, 21, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajwa, J.; Munir, U.; Nori, A.; Williams, B. Artificial intelligence in healthcare: Transforming the practice of medicine. Future Healthc. J. 2021, 8, e188–e194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.S.; Jaiswal, V. Applicability of artificial intelligence in different fields of life. IJSR 2013, 1, 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, T.P.; Senadeera, M.; Jacobs, S.; Coghlan, S.; Le, V. Trust and Medical AI: The Challenges We Face and the Expertise Needed to Overcome Them. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2021, 28, 890–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Royal Society. Machine Learning: The Power and Promise of Computers That Learn by Example; The Royal Society: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, C.H.; Lee, K.H.; Choi, Y.J.; Kim, S.H.; Choi, H.; Oh, J.; Lee, J.; Jeong, J.; Lee, Y.; Kim, H.J.; et al. Oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: Radiomic machine-learning classifiers from multiparametric MR images for determination of HPV infection status. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, P.; van den Brekel, M.W.M.; Gouw, Z.A.R.; Hoebers, F.; van der Heijden, H.F.M.; van den Berg, R.; de Bree, R.; van der Laan, B.F.; Willems, S.M.; Rinkel, J.; et al. Clinical variables and magnetic resonance imaging-based radiomics predict human papillomavirus status of oropharyngeal cancer. Head Neck 2021, 43, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujima, N.; Nakamura, T.; Yoshida, T.; Miura, T.; Suzuki, T.; Tanaka, T.; Shiraishi, T.; Fukui, T.; Sakata, M.; Takahashi, T.; et al. Prediction of the human papillomavirus status in patients with oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma by FDG-PET imaging dataset using deep learning analysis: A hypothesis-generating study. Eur. J. Radiol. 2021, 126, 108943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, B.; Lee, S.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, S.; Kim, S.Y.; Lee, H.; Park, S.; Choi, Y.S.; Hwang, S.; Nam, S.Y.; et al. Machine learning-based radiomic HPV phenotyping of oropharyngeal SCC: A feasibility study using MRI. Laryngoscope 2021, 131, E851–E856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, D.M.; van Dijk, L.; van der Heijden, H.F.M.; Cramer, L.; Leemans, C.R.; Willems, S.M.; Langen, M.; van den Brekel, M.W.M.; Gouw, Z.A.R.; Bos, P.; et al. Deep learning based HPV status prediction for oropharyngeal cancer patients. Cancers 2021, 13, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiazi, R.; Zanjirband, M.; Ganjgahi, H.; Fazeli, M.; Fattahi, M.; Amiri, M.; Fadaei, F.; Sarrafzadeh, M.; Sadeghi, N.; Pourghassem, H.; et al. Prediction of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) association of oropharyngeal cancer (OPC) using radiomics: The impact of the variation of CT scanner. Cancers 2021, 13, 2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, C.; Lee, Y.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, S.Y.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Hwang, J.; Kim, J.; Yoon, H.J.; Lee, J.; et al. Development and testing of a machine learning model using 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT-derived metabolic parameters to classify human papillomavirus status in oropharyngeal squamous carcinoma. Korean J. Radiol. 2021, 24, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, M.J.; Sahu, S.K.; Garg, S.; Das, M.; Soni, A.; Gupta, D.; Singh, M.; Rawat, D.; Kumar, P.; Deka, P.; et al. Multi-modal ensemble deep learning in head and neck cancer HPV sub-typing. Bioengineering 2023, 11, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazelpour, S.; Sadeghi, N.; Ganjgahi, H.; Amiri, M.; Zarei, S.; Hosseinzadeh, R.; Zanjirband, M.; Fattahi, M.; Karami, H.; Hashemi, S.; et al. Multiparametric machine learning algorithm for human papillomavirus status and survival prediction in oropharyngeal cancer patients. Head Neck 2023, 45, 2882–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Wei, J.; Wang, Y.; Lu, H.; Chen, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; et al. Applying multisequence MRI radiomics of the primary tumor and lymph node to predict HPV-related p16 status in patients with oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2023, 13, 2234–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanizzi, A.; De Blasi, R.; Fracasso, G.; Abis, M.; Crivellaro, S.; Sgarella, A.; De Masi, F.; Sannino, G.; Fumarola, D.; Mossa, L.; et al. Explainable prediction model for the human papillomavirus status in patients with oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma using CNN on CT images. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 14276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.; Galle, F.; Pallasch, L.; Steffens, J.; Bär, C.; Thelen, M.; Klingenberg, R.; Lipka, D.; Behrendt, V.; Luedde, T.; et al. Deep learning predicts HPV association in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas and identifies patients with a favorable prognosis using regular H&E stains. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 1131–1138. [Google Scholar]

- Fouad, S.; Othman, H.; Elhamalawy, M.; Fahmy, M.; Kassem, M.; Elbeltagy, M.; Sabry, M.; Sayed, A.; El-Khouly, A.; Fawzy, M.; et al. Human papillomavirus detection in oropharyngeal carcinomas with in situ hybridization using handcrafted morphological features and deep central attention residual networks. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 2021, 88, 101853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, H.; Xu, X.; Zhou, Z.; Huang, X.; Chen, S.; et al. A novel deep learning algorithm for human papillomavirus infection prediction in head and neck cancers using routine histology images. Mod. Pathol. 2023, 36, 100320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adachi, M.; Yamaguchi, M.; Kawai, T.; Suzuki, H.; Nakamura, K.; Takahashi, M.; Miyamoto, K.; Okada, H.; Tanaka, Y.; Nakatani, Y.; et al. Extracting interpretable features for pathologists using weakly supervised learning to predict p16 expression in oropharyngeal cancer. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karako, K.; Song, P.; Chen, Y.; Tang, W. New possibilities for medical support systems utilizing artificial intelligence (AI) and data platforms. Biosci. Trends 2023, 17, 186–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.M.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is All You Need. NeurIPS. 2017. Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2017/file/3f5ee243547dee91fbd053c1c4a845aa-Paper.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Radford, A.; Narasimhan, K.; Salimans, T.; Sutskever, I. Improving Language Understanding by Generative Pre-Training. Available online: https://cdn.openai.com/research-covers/language-unsupervised/language_understanding_paper.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Roman, B.R.; Aragones, A. Epidemiology and incidence of HPV-related cancers of the head and neck. J. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 124, 920–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkin, D.M.; Bray, F. Chapter 2: The burden of HPV-related cancers. Vaccine 2006, 24 (Suppl. S3), S11–S25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economopoulou, P.; Kotsantis, I.; Psyrri, A. Special issue about head and neck cancers: HPV positive cancers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, K.; Matsuo, K.; Sano, D.; Tominari, T.; Inoue, T.; Miyamoto, Y.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Nakamura, K.; Toh, S.; Uchida, Y.; et al. A review of HPV-related head and neck cancer. J. Clin. Med. 2018, 7, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echle, A.; Fuchs, T.J.; Razi, M.; Hoeg, P.; Beck, A.; Chlebus, G.; Reicherzer, T.; Marschner, J.; Bieg, M.; Elkin, E.; et al. Deep learning in cancer pathology: A new generation of clinical biomarkers. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 124, 686–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brendel, M.; Reisser, C.; Hester, J.; Fiedler, S.; Kaiser, N.; Mangold, C.; Fiebrandt, J.; Dörr, D.; Weyer, G.; Lücke, C.; et al. Weakly-supervised tumor purity prediction from frozen H&E stained slides. EBioMedicine 2022, 80, 104067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevens, D.; Nuyts, S. HPV-positive head and neck tumours, a distinct clinical entity. B-ENT 2015, 11, 81–87. [Google Scholar]

- Schache, A.G.; Liloglou, T.; Risk, J.M.; Duvvuri, U.; Jones, A.; Eisele, D.W.; Eason, J.; McElroy, J.; Coussens, L.M.; McCaffrey, T.V.; et al. Evaluation of human papillomavirus diagnostic testing in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: Sensitivity, specificity, and prognostic discrimination. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 6262–6271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mungai, F.; Verrone, G.B.; Pietragalla, M.; Bimbi, G.; Marchionni, P.; Castaldi, P.; Lupi, M.; Mazzella, A.; Fuso, L.; Cavallo, G.; et al. CT assessment of tumor heterogeneity and the potential for the prediction of human papillomavirus status in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Radiol. Med. 2019, 124, 804–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillies, R.J.; Kinahan, P.E.; Hricak, H. Radiomics: Images Are More than Pictures, They Are Data. Radiology 2016, 278, 563–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambin, P.; Leijenaar, R.T.H.; Deist, T.M.; Peerlings, J.; van Timmeren, J.; Vanneste, B.G.; de Jong, E.E.; Velec, M.; Dekker, A.; Candelaria, R.P.; et al. Radiomics: The bridge between medical imaging and personalized medicine. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 14, 749–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shur, J.D.; Doran, S.J.; Kumar, S.; Beasley, M.; Schmitz, C.; Grist, S.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Ng, M.; Chen, L.; et al. Radiomics in Oncology: A Practical Guide. Radiographics 2021, 41, 1717–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).