Simple Summary

Several dietary phenolic compounds isolated from medicinal plants exert significant anticancer effects via several mechanisms. They induce apoptosis, autophagy, telomerase inhibition, and angiogenesis. Certain dietary phenolic compounds increase the effectiveness of drugs used in conventional chemotherapy. Some clinical uses of dietary phenolic compounds for treating certain cancers have shown remarkable therapeutic results, suggesting effective incorporation in anticancer treatments in combination with traditional chemotherapeutic agents.

Abstract

Despite the significant advances and mechanistic understanding of tumor processes, therapeutic agents against different types of cancer still have a high rate of recurrence associated with the development of resistance by tumor cells. This chemoresistance involves several mechanisms, including the programming of glucose metabolism, mitochondrial damage, and lysosome dysfunction. However, combining several anticancer agents can decrease resistance and increase therapeutic efficacy. Furthermore, this treatment can improve the effectiveness of chemotherapy. This work focuses on the recent advances in using natural bioactive molecules derived from phenolic compounds isolated from medicinal plants to sensitize cancer cells towards chemotherapeutic agents and their application in combination with conventional anticancer drugs. Dietary phenolic compounds such as resveratrol, gallic acid, caffeic acid, rosmarinic acid, sinapic acid, and curcumin exhibit remarkable anticancer activities through sub-cellular, cellular, and molecular mechanisms. These compounds have recently revealed their capacity to increase the sensitivity of different human cancers to the used chemotherapeutic drugs. Moreover, they can increase the effectiveness and improve the therapeutic index of some used chemotherapeutic agents. The involved mechanisms are complex and stochastic, and involve different signaling pathways in cancer checkpoints, including reactive oxygen species signaling pathways in mitochondria, autophagy-related pathways, proteasome oncogene degradation, and epigenetic perturbations.

1. Introduction

Cancer is a significant issue for physicians in multidisciplinary health care facilities. It is a complex and multifactorial pathology in which normal cells develop mutations in their genetic structure, resulting in continued cell growth, colonization, and metastasis to other organs such as the liver, prostate, breast, lungs, brain, and colon. The transformation mechanisms range from genetic and hormonal disturbances to environmental inducers and metabolic deregulations. This divergence of risk factors gives rise to various forms of cancer and, sometimes, implies therapeutic specificity even for the same type of cancer [1,2,3]. In this regard, searching for anticancer treatments requires screening several chemical molecules with functional diversity. Among the candidate molecules studied are phenolic compounds. Chemically defined as having a phenolic structure, phenolic compounds are well recognized for their extensive pharmacological properties such as anti-inflammatory, antibiotic, antiseptic, antitumor, antiallergic, cardioprotective, etc. Phenolic compounds are derived from edible plants, particularly medicinal and aromatic plants, in many food products such as vegetables, cereals, legumes, fruits, nuts, and certain beverages. Indeed, this chemical family constitutes a group of substances frequently present in the metabolism of medicinal plants and contains several subclasses, such as acids, flavonoids, and tannins, which are the most abundant molecules [4,5,6]. Various investigations have focused on phenolic compounds as anticancer bioactive compounds. These groups of molecules exert anticancer properties by acting on the multiple checkpoints of cancerous cells and can induce apoptosis, autophagy, and cell cycle arrest with high specificity [7,8].

In addition, phenolic compounds exert other actions such as inhibiting telomeres, blocking their expression and inhibiting angiogenesis and metastases. On the other hand, phenolic compounds have recently been shown to act in combination with other bioactive compounds used in chemotherapy, sometimes with a potent synergistic mechanism. Recent investigations have also highlighted the sensitization action of cancer cells to chemotherapeutic treatments [9,10]. Indeed, dietary phenolic compounds can induce chemosensitivity of human cancers towards used drugs in chemotherapy via different molecular mechanisms, which include reducing the expression of a transcription factor regulating the expression of cytoprotective genes, the down-regulation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Akt protein kinase B (PI3K/Ak) pathway, reducing p53 activation, enhancing the cytotoxicity of used drugs, decreasing Bcl-2 expression and mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) while inhibiting tumor growth, enhancing the cytotoxicity of used drugs, reducing Bcl-2 expression and mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) while inhibiting tumor growth, suppressing the expression of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1α) and P-glycoprotein (P-gp) responsible for multidrug resistance, and increasing cellular apoptosis with down-regulation of p-Akt expression and up-regulation of phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) expression [9,10]. Based on the previous discussion, this study aims to investigate and demonstrate the potential benefits of dietary sources, notably phenolic compounds, in managing and preventing cancer. Additionally, the current review aims to examine combining chemotherapeutic drugs with phenolic compounds and their sensitizing effects on cancer treatments to improve the effectiveness and diminish the harmful effects of anticancer bioactive compounds.

2. Dietary Phenolic Compounds Improving the Chemosensitivity of Anticancer Drugs

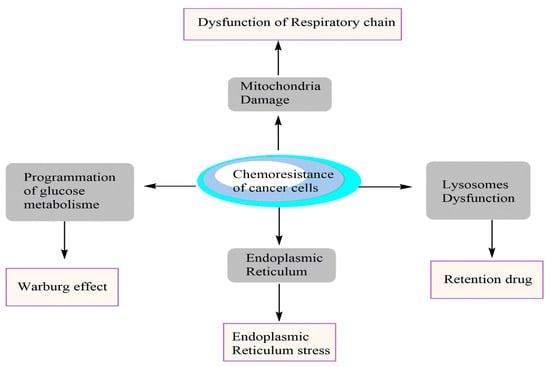

Recent research findings showed that cancer cells could develop resistance to used drugs in chemotherapy. This resistance is related to different molecular mechanisms which give cancer cells a selective advantage in resisting drugs administered during cancer chemotherapy (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of chemoresistance of cancer cells against anticancer drugs.

2.1. Flavonoids

Resistance to various anti-cancer treatments, whether chemotherapy or radiotherapy, remains a significant obstacle in the management of cancer patients. Therefore, the use of chemo- and radio-sensitizers of plant origin has attracted the attention of scientists to replace synthetic drugs to improve tumor sensitivity. One example of these natural compounds is flavonoids. Food products containing high levels of flavonoids include blueberries and other berries, parsley, onions, bananas, green and black tea, citrus fruits, sea buckthorn, Ginkgo biloba, and dark chocolate.

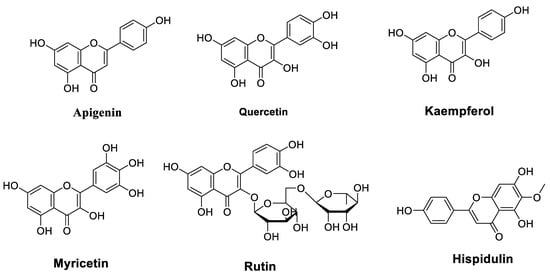

Combinatorial treatment with flavonoids has been suggested in several studies as a potential therapeutic approach to avoid drug resistance and enhance their antitumor properties. Table 1 lists flavonoids (Figure 2) that improve the chemosensitivity of chemotherapeutic drugs in cancer.

Table 1.

Flavonoids improve the chemosensitivity of chemotherapeutic drugs in cancer.

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of flavonoids that improve the chemosensitivity of anticancer drugs.

2.1.1. Flavones

Apigenin is a natural product found in numerous fruits and vegetables, but it is particularly abundant in chamomile tea, parsley, celery, propolis, and garlic oil. It was among the most investigated flavonoids in this field. In 2006, Chan, et al. [11] synthesized a series of apigenin dimers that increased the chemo-sensitivity of leukemic and breast cells, known to be multidrug-resistant (MDR), to numerous anticancer drugs, such as vinblastine (VBL), vincristine (VCR), daunomycin (DM), doxorubicin (DOX), and paclitaxel (PTX) [11]. Seven years later, the chemo-sensitive mechanism by which apigenin acts on DOX has been investigated [12]. The mechanism involves reducing the expression of a transcription factor regulating the expression of cytoprotective genes, called Nrf2, at the levels of proteins and messenger RNA by down-regulating the PI3K/Akt pathway. Compared to DOX treatment alone, the combination treatment of apigenin with DOX showed anticancer effects by inducing apoptosis, reducing cell proliferation, and inhibiting tumor growth.

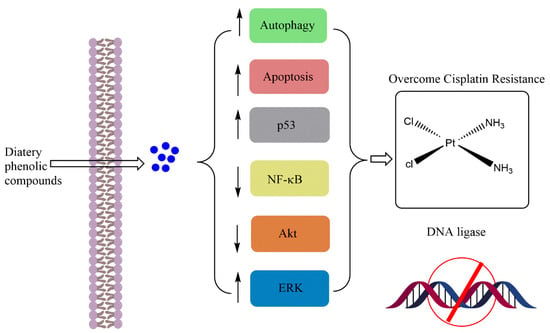

Johnson and Mejia [13] evaluated the interaction effect between this flavonoid and one of the known chemotherapeutic drugs, gemcitabine (GEM), on human pancreatic cancer cells. This interaction inhibited cell proliferation and growth by 59–73%, whereas apigenin alone potentiated the anti-proliferative effect of GEM. This effect was attributed to IKK-β-mediated NF-κB activation [14]. To improve the chemo-sensitivity of another chemotherapeutic agent, called cisplatin (CP), and to overcome the chemo-resistance of laryngeal carcinoma (Hep-2 cells), apigenin was chosen in an in vitro co-targeted therapy [15]. The results showed that CP-induced Hep-2 cell growth suppression was significantly enhanced in a time- and concentration-dependent manner with suppression of p-AKT and glucose transporter-1 (GLUT-1) involved in resistance to cancer treatments. Bao, et al. also tested this a year later against the same type of cancer [16]. In human renal proximal tubular epithelial cells, apigenin ameliorated CP-induced nephrotoxicity by promoting the PI3K/Akt pathway (Figure 3) and reducing p53 activation [18].

Figure 3.

Mechanisms of chemosensitivity of apigenin towards sisplatin.

On the other hand, a promising combined effect was recorded with apigenin and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), a chemotherapeutic drug belonging to the class of antimetabolite drugs [17,19]. In this context, apigenin significantly improved the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) by enhancing the cytotoxicity of 5-FU [17]. The combination of these two elements decreased Bcl-2 expression and mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) while inhibiting tumor growth of HCC xenografts. This was in agreement with the results of Gaballah and collaborators [19], who also observed a reduction in tumor size and Mcl-1 expression, with an increase in Beclin-1 levels and caspase-3 and -9 activities. Furthermore, Gao, et al. [20,21] investigated the chemosensitivity of apigenin using BEL-7402/ADM cells, which are known for their resistance to DOX, a molecule belonging to the anthracycline family. Results showed that apigenin enhanced DOX sensitivity, induced apoptosis, and prevented HCC xenograft growth. Recently, treatment with apigenin was applied to ovarian cancer (OC) using ovarian cancer-sensitive cells (SKOV3) and drug-resistant cells (SKOV3/DDP) [22]. Results showed positive effects on the chemo-sensitivity of both cell types with apoptosis and reversal of drug resistance of these cancer cells through the down-regulation of the Mcl-1 gene.

2.1.2. Flavanols

Quercetin is naturally distributed in many fruits, vegetables, leaves, seeds, and grains; capers, red onions, and kale contain appreciable quantities. Regarding quercetin, several research studies have evaluated the effect of this flavonoid against multidrug resistance by several mechanisms of action in various cancer cells. Research findings indicated that a co-treatment with quercetin combined with temozolomide (TMZ), an active anticancer drug, showed positive results such as inhibition of cell viability, induction of cell apoptosis, an increase of caspase-3 activity, elimination of drug insensitivity, and improvement of TMZ inhibition [23,27]. Some of these effects, such as the decrease in colony formation, inhibition of growth, and the stimulation of apoptosis by decreasing Bcl2 gene expression and increasing p53 and caspase-9 activity in esophageal (EC9706 and Eca109) have also been observed by combining quercetin with 5-FU [24] and breast (MCF-7) [34] cancer cells.

The management of breast cancer attracted the attention of Li, et al. [25,28] who performed two experiments to evaluate the combination therapy of quercetin with DOX on MCF-7 cells. Results revealed that this treatment inhibits cell invasion and proliferation by suppressing the expression of HIF-1α and P-glycoprotein (P-gp), responsible for multidrug resistance [25]. In addition, results showed an increase in cellular apoptosis with down-regulation of p-Akt expression and up-regulation of phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) expression [28]. Other effects of this combination, namely increasing cellular sensitivity to DOX and promoting DOX-induced cellular apoptosis via the mitochondrial/ROS pathway, respectively, have been noted in studies conducted by Chen, et al. [30] and by Shu, et al. [31] in the treatment of HCC (BEL-7402 cells) and prostate cancer (PC3 cells). Quercetin alone was able to down-regulate the expression of specific ABC transporters (ABCB1, ABCC1, and ABCC2) [30] with inhibition of the expression of the PI3K/AKT pathway [31].

On the other hand, the synergistic effect of quercetin was examined in vitro and in vivo with PTX, a molecule used in chemotherapy and synthesized by endophytic fungi [26]. Quercetin alone inhibited the proliferation of OC cells and increased their sensitivity to PTX [26]. Meanwhile, the combination of these two molecules showed an inhibition of the migration and proliferation of prostate cancer cells with an increase in apoptosis, and induction of G2/M cell cycle arrest, whereas the in vivo combination showed a synergistic effect in killing cancer cells [26]. Moreover, this flavonol positively affected GEM, a drug with significant cytotoxic activity, such as the improvement of cell death associated with increased caspase-3 and -9 activities in lung cancer cells. It caused considerable suppression of HSP70 chaperone protein expression compared to treatment with GEM alone [29]. This chemo-sensitivity has also been noted in pancreatic cancer cells [32]. In a recent study, Safi, et al. [35] evaluated the synergistic effect of quercetin (95 μM) with docetaxel (7 nM), an alkaloid with anticancer properties. Results revealed a decrease in STAT3, AKT, pERK1/2, and Bcl-2 proteins in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells.

2.1.3. Flavonols

Kaempferol is a flavonol found in numerous fruits and vegetables such as grapes, potatoes, squash, tomatoes, broccoli, onions, brussels sprouts, green beans, green tea, peaches, spinach, blackberries, lettuce, cucumber, apples, and raspberries. It has been studied for its chemo-sensitizing activity. Its association with quercetin has shown promising results, namely growth inhibition of adriamycin-resistant K562/A cells and myeloid leukemia K562 cells, increasing their sensitivity, and induction of apoptosis [36]. Additionally, this ubiquitous flavonoid chemo-sensitized 5-FU resistant colon cancer LS174-R cells and the combination of both substances provided a synergistic effect by inhibiting cell viability and inducing cell cycle arrest [37]. This was explained recently by Wu et al. [38] who attributed these results to the inhibition of PKM2-mediated glycolysis. The combinatorial effect of 5-FU with a flavonol was further evaluated (in vitro and in vivo) with myricetin against esophageal carcinoma [39]. Several favorable outcomes such as suppression of cell proliferation, increase in cell apoptosis and caspase-3 expression, and decrease in Bcl-2 and tumor xenograft growth (in vivo) were observed. In addition, kaempferol increased the PTX cytotoxicity with modulation of anti- and pro-apoptotic markers in OC cells [40].

As previously reported in breast cancer treatment with flavonoids, these secondary metabolites reverse cancer drug resistance and sensitize tumor cells to chemotherapy via several mechanisms. In this respect, Iriti et al. studied the chemo-sensitizing potential of rutin (3′,4′,5,7-Tetrahydroxy-3-[α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1–6)-β-D-glucopyranosyloxy]flavone) against two breast cancer cell lines (MB-MDA-231 and MCF-7 cells) [41]. At a dose of 20 μM, these researchers found that this flavonoid acts as a chemo-sensitizing agent by improving the anti-tumor effect of two chemotherapeutic agents (methotrexate and cyclophosphamide). Furthermore, rutin improved the in vivo efficacy of another anti-cancer drug (sorafenib) in a xenograft model of human HCC [42]. As seen with quercetin and berberine, another natural flavone called hispidulin enhanced cellular chemo-sensitivity by inhibiting the expression of the transcription factor HIF-1α via AMPK signaling in gallbladder cancer [43].

2.1.4. Anthocyanidins

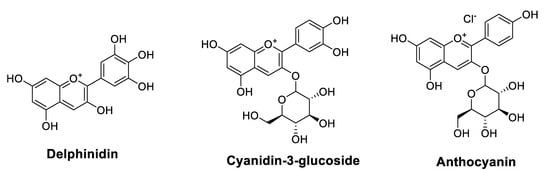

Anthocyanins (ACNs) are the primary color of many leaves (such as purple cabbage), fruits (such as grapes and blueberries), tubers (such as purple radishes and yams), and flowers (such as roses). In a broad sense, anthocyanidins (ACNs) present a subclass of flavonoids that have not been well investigated for their chemo-sensitizing and radio-sensitizing effects. Indeed, black raspberry ACNs improved the efficacy of two chemotherapeutic agents (5-FU and celecoxib); in vitro by inhibiting the proliferation of CRC cells and in vivo by decreasing the number of CRC tumors in animals [44]. Recently, specific molecules of this family, such as delphinidin [45] and cyanidin-3-glucoside (C3G) [46], have been studied. In radiation-exposed A549 human lung adenocarcinoma cells, delphinidin enhanced the radio-therapeutic effects (induction of autophagy and apoptosis) by activating the JNK/MAPK signaling pathway [45]. Similarly, C3G improved the sensitivity to DOX and its cytotoxicity by inhibiting the phosphorylation of Akt and increasing that of p38, mainly by reducing the expression of claudin-2 [46]. Table 2 lists anthocyanidins (Figure 4) that could improve the chemosensitivity of cancer drugs.

Table 2.

Anthocyanidins that could enhance the chemosensitivity of cancer drugs.

Figure 4.

Chemical structures of anthocyanidins that improve chemosensitivity of anticancer drugs.

2.2. Non-Flavonoids

2.2.1. Phenolic Acids

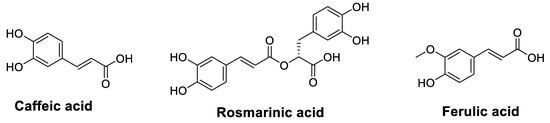

It has been demonstrated that phenolic acids have a chemo-sensitizing activity on several types of cancer cells to different chemotherapeutics (Table 3). Data presented in Table 3 indicate that ellagic acid was the most studied molecule. It is found in large quantities in pecans, chestnuts, raspberries, peaches, cranberries, strawberries, raw grapes, walnuts, and pomegranates. Indeed, its combination with 5-FU in treating colorectal carcinoma (CRC) gave significant effects such as inhibition of apoptotic cell death and cell proliferation. In contrast, treatment alone enhanced 5-FU chemo-sensitivity in CRC cells [47]. Indeed, ellagic acid alone potentiated CP cytotoxicity and prevented the development of CP resistance in epithelial OC cells [48]. Table 3 shows the phenolic acids (Figure 5) that improve the chemosensitivity of cancer drugs.

Table 3.

Phenolic acids that improve the chemosensitivity of cancer drugs.

Figure 5.

Chemical structures of phenolic acids that improve the chemosensitivity of anticancer drugs.

Caffeic acid can be derived from a variety of beverages and is relatively present at high concentrations in lingonberry, thyme, sage, and spearmint as well as in spices such as Ceylon cinnamon and star anise. Caffeic acid is moderately available in sunflower seeds, applesauce, apricots, and prunes. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE), a central component of propolis, has also been investigated for its chemo-sensitizing [51,52] and radio-sensitizing [53] effects against various types of cancer. The radio-sensitizing effect of this substance was evaluated in 2005 by Chen, et al. [49] against CT26 colorectal adenocarcinoma cells and in vivo on BALB/c mice implanted with these cells. These authors noted, in vitro, an improvement in the destruction of CT26 cells by ionizing radiation (IR) and, in vivo, an extension of animal survival and a marked inhibition of tumor growth compared to radiotherapy alone. The mechanism of action explaining this radio-sensitivity was elucidated very recently on prostate cancer cells (DU145 and PC3) by co-treatment using gamma radiation (GR) and CAPE [53]. Results showed that this combined treatment sensitizes the cells to radiotherapy by reducing the RAD50 and RAD51 proteins and the cell migration potential, mainly by inhibiting DNA damage repair. As for the chemo-sensitivity of this phenolic compound, Lin, et al. [50] did not observe any chemo-sensitizing effect of medulloblastoma Daoy cells on the chemotherapeutics studied (DOX or CP). However, in 2018, two similar studies proved otherwise by enhancing the sensitivity of gastric and lung cancer cells to DOX and CP by decreasing proteasome function [51,52].

In contrast, Muthusamy, et al. carried out two studies on the ability of ferulic acid (FA), a phenolic acid present in seeds and leaves of certain plants and found in exceptionally high amounts in popcorn and bamboo shoots, to reverse the resistance of multiresistant cells to anticancer drugs. In the first study, FA-enhanced cell cycle arrest was exerted by PTX and decreased resistance to this drug [54]. In the second study, FA increased VCR and DOX cytotoxicity and synergistically increased DOX-induced apoptotic signaling [55]. In addition, the authors showed that the synergy between FA and DOX reduced tumor xenograft size compared to the treatment with DOX alone. They associated these results with suppressing P-gp expression by inhibiting the PI3K/Akt/NF-κB signaling pathway.

Another phenolic acid constituent, called rosmarinic acid (RA), is found in culinary herbs such as Ocimum tenuiflorum (holy basil), Origanum majorana (marjoram), Melissa officinalis (lemon balm), Ocimum basilicum (basil), Salvia officinalis (sage), Salvia rosmarinus (rosemary), peppermint, and thyme. This natural compound showed remarkable potential as an anti-leukemic agent in acute promyelocytic leukemia cells by potentiating macrophage differentiation induced by all-trans retinoic acid [56]. Furthermore, Yu, et al. [57] evaluated the impact of RA on 5-FU chemo-resistance in the treatment of gastric carcinoma. In SGC7901 gastric carcinoma cells treated with 5-FU, the application of RA increased the chemo-sensitivity of these cells to 5-FU by reducing its IC50 values from 208.6 to 70.43 μg/mL and the expression levels of two miRNAs (miR-642a-3p and miR-6785-5p), with increased expression of FOXO4.

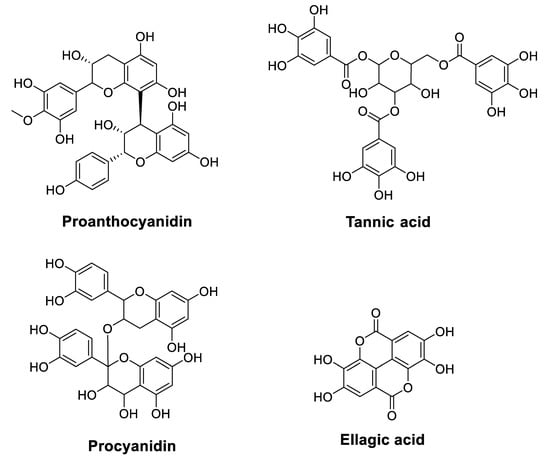

2.2.2. Tannins

Although condensed tannins (also called proanthocyanidins (PCs)), found in plants, such as cranberry, blueberry, and grape seeds, are chemically polymers of flavanols, they have not been widely investigated as anticancer agents compared to flavonoids and phenolic acids. However, they have recently been studied to overcome the problems of cancer cell resistance to chemotherapy [58]. In this context, Zhang, et al. [58] showed that PCs inhibit the growth and characteristics of platinum-resistant OC cells by inducing G1 cell cycle arrest and targeting the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. On the other hand, other researchers indicated that PCs sensitize chemoresistant CC cells (HCT116 and H716) to 5-FU and oxaliplatin (OXP) [59]. In contrast, combining all these substances reduced tumor growth in chemoresistant cells and chemoresistant tumor xenografts. The mechanism suggested to overcome this chemo-resistance involves suppressing the activity of adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette transporters. Furthermore, tannic acid (TA), another plant tannin used as an anticancer agent, has been studied for its synergistic effect with chemotherapeutic drugs (5-FU, GEM, and mitomycin C) against malignant cholangiocytes [60]. Results revealed that TA exhibits a crucial synergistic effect with 5-FU and mitomycin C in modulating drug efflux pathways. The exact synergy was observed by combining TA and CP on HepG2 liver cancer cells through mitochondria-mediated apoptosis [61]. This chemotherapeutic sensitivity to CP was corroborated by co-treatment with procyanidins in TU686 laryngeal cancer cells through the apoptosis and autophagy pathway [62]. Table 4 lists condensed tannins (Figure 6) that could improve the chemosensitivity of cancer drugs.

Table 4.

Condensed tannins that could improve the chemosensitivity of cancer drugs.

Figure 6.

Chemical structures of tannins that improve chemosensitivity of anticancer drugs.

To improve the bioavailability and bioactivity of ellagic acid in vivo, Mady, et al. [63] formulated nanoparticles loaded with this acid from a biodegradable polymer [poly(ε-caprolactone)]. This encapsulation improved the oral bioavailability and the anti-tumor effect of ellagic acid. In a glioblastoma model, Cetin, et al. carried out two studies that showed an improvement in the anticancer efficacy of bevacizumab [64] and TMZ [65] by co-treatment with ellagic acid. This treatment reduced the expression of MGMT, affected caspase-3 and p53 proteins, and its combination with the chemotherapeutics reduced cell viability and the expression of MDR1.

Chemo-resistance of bladder cancer has been a serious problem in managing this type of cancer, particularly resistance to GEM. However, the underlying resistance mechanism has not been elucidated. The effect of ellagic acid or its combinatorial effect with GEM on GEM-sensitive bladder cancer cells and GEM-resistant cells was recently evaluated [66]. Results revealed that ellagic acid exerts numerous promising anticancer effects, particularly resensitization of GEM-resistant cells by inhibiting GEM transporters and the epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), responsible for GEM resistance in other types of cancer. Suppression of EMT was also observed by catechol against pancreatic cancer cells, in addition to cellular chemo-sensitivity and radio-sensitivity to GEM via inhibition of the AMPK/Hippo signaling pathway [67].

3. Conclusions and Perspectives

At present, the use of foodstuffs is attracting attention in treating and preventing diseases, including cancer. This is due to the presence of bioactive compounds such as phenolic acids, among others, in our diet. These natural compounds are gaining popularity in cancer treatment due to their lower side effects, cost, and accessibility than conventional drugs. In this review, we have shown through published research that phenolic compounds are an excellent source of natural anticancer substances providing a range of preventive and therapeutic options against several types of cancer. These compounds could be used alone or in combination with other anticancer drugs. Certain phenolic compounds such as quercetin and gallic acid have well-known mechanisms of action. These molecules act specifically on the various checkpoints of cancerous cells. Therefore, exploring these mechanisms of action could further improve the therapeutic efficacy. However, further investigations that could involve human subjects and different pharmacokinetic parameters are required to ensure the safety of these compounds before they can be used as prescription drugs. In addition, the development of a standardized extract or dosage could also be followed in clinical trials. In summary, phenolic compounds present in our food can be useful in complementary medicine for the prevention and treatment of different types of cancers due to their natural origin, safety, and low cost compared to cancer drugs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B. (Abdelhakim Bouyahya), P.W. and M.S.M.; methodology, N.E.O., N.E.H. and S.B.; software, A.B. (Abdelaali Balahbib); validation, A.B. (Abdelhakim Bouyahya); formal analysis, A.B. (Abdelhakim Bouyahya); investigation, A.B. (Abdelhakim Bouyahya), N.E.O., N.E.H. and S.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.B. (Abdelhakim Bouyahya); N.E.O., N.E.H. and S.B.; writing—review and editing, A.B. (Abdelhakim Bouyahya), P.W. and M.S.M.; supervision, A.B. (Abdelhakim Bouyahya) and M.S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| ACNs | Anthocyanidins |

| Akt | Protein Kinase B |

| APG | Apigenin |

| CAPE | Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester |

| CLL | Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia |

| COX-2 | Cyclooxygenase-2 |

| CRC | Colorectal Carcinoma |

| DM | Daunomycin |

| DOX | Doxorubicin |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| EMT | Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition |

| ERK | Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase |

| FA | Ferulic acid |

| GLUT-1 | Glucose Transporter-1 |

| Gem | Gemcitabine |

| GR | Gamma Radiation |

| HCC | Hepatocellular Carcinoma |

| HIF-1α | Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α |

| HO | Heme Oxygenase |

| HPD | Hispidulin |

| HPDE | Human pancreatic ductal epithelium |

| IL | Interleukin |

| IR | Ionizing Radiation |

| JNK | C-Jun N-Terminal Kinase |

| KAE | Kaempferol |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| MDR1 | Multidrug resistance protein 1 |

| MM | Multiple Myeloma |

| mTOR | mammalian Target of Rapamycin |

| MYR | Myricetin |

| NF-ĸB | Nuclear Factor Kappa B |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid-related factor 2 |

| NSCLC | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer |

| OC | Ovarian Cancer |

| OXP | Oxaliplatin |

| P-gp | P-glycoprotein |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and Tensin Homolog |

| PTX | Paclitaxel |

| Que | Quercetin |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| RTN | Rutin |

| STAT3 | Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 |

| TA | Tannic acid |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor-α |

| TMZ | Temozolomide |

| VBL | Vinblastine |

| VCR | Vincristine |

| 5-FU | 5-Fluorouracil |

References

- Hurson, A.N.; Ahearn, T.U.; Keeman, R.; Abubakar, M.; Jung, A.Y.; Kapoor, P.M.; Koka, H.; Yang, X.R.; Chang-Claude, J.; Martínez, E. Systematic Literature Review of Risk Factor Associations with Breast Cancer Subtypes in Women of African, Asian, Hispanic, and European Descents. Cancer Res. 2022, 82, 3670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stopsack, K.H.; Nandakumar, S.; Arora, K.; Nguyen, B.; Vasselman, S.E.; Nweji, B.; McBride, S.M.; Morris, M.J.; Rathkopf, D.E.; Slovin, S.F. Differences in Prostate Cancer Genomes by Self-Reported Race: Contributions of Genetic Ancestry, Modifiable Cancer Risk Factors, and Clinical FactorsRacial Differences in Prostate Cancer Genomes. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.A.; Dayu, A.R.B. Menopausal Hormone Therapy: Why We Should No Longer Be Afraid of the Breast Cancer Risk. Climacteric 2022, 25, 362–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobroslavić, E.; Repajić, M.; Dragović-Uzelac, V.; Elez Garofulić, I. Isolation of Laurus Nobilis Leaf Polyphenols: A Review on Current Techniques and Future Perspectives. Foods 2022, 11, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.; Tareq, A.M.; Das, R.; Emran, T.B.; Nainu, F.; Chakraborty, A.J.; Ahmad, I.; Tallei, T.E.; Idris, A.M.; Simal-Gandara, J. Polyphenols: A First Evidence in the Synergism and Bioactivities. Food Rev. Int. 2022, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosero, S.; Del Pozo, F.; Simbaña, W.; Álvarez, M.; Quinteros, M.F.; Carrillo, W.; Morales, D. Polyphenols and Flavonoids Composition, Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Properties of Andean Baccharis Macrantha Extracts. Plants 2022, 11, 1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, B.U.; Suhail, M.; Khan, M.K.; Zughaibi, T.A.; Alserihi, R.F.; Zaidi, S.K.; Tabrez, S. Polyphenols as Anticancer Agents: Toxicological Concern to Healthy Cells. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 6063–6079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauf, A.; Shariati, M.A.; Imran, M.; Bashir, K.; Khan, S.A.; Mitra, S.; Emran, T.B.; Badalova, K.; Uddin, M.; Mubarak, M.S. Comprehensive Review on Naringenin and Naringin Polyphenols as a Potent Anticancer Agent. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 31025–31041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottaghi, S.; Abbaszadeh, H. Natural Lignans Honokiol and Magnolol as Potential Anticarcinogenic and Anticancer Agents. A Comprehensive Mechanistic Review. Nutr. Cancer 2022, 74, 761–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoganathan, S.; Alagaratnam, A.; Acharekar, N.; Kong, J. Ellagic Acid and Schisandrins: Natural Biaryl Polyphenols with Therapeutic Potential to Overcome Multidrug Resistance in Cancer. Cells 2021, 10, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.-F.; Zhao, Y.; Burkett, B.A.; Wong, I.L.; Chow, L.M.; Chan, T.H. Flavonoid Dimers as Bivalent Modulators for P-Glycoprotein-Based Multidrug Resistance: Synthetic Apigenin Homodimers Linked with Defined-Length Poly (Ethylene Glycol) Spacers Increase Drug Retention and Enhance Chemosensitivity in Resistant Cancer Cells. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 6742–6759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, A.-M.; Ke, Z.-P.; Wang, J.-N.; Yang, J.-Y.; Chen, S.-Y.; Chen, H. Apigenin Sensitizes Doxorubicin-Resistant Hepatocellular Carcinoma BEL-7402/ADM Cells to Doxorubicin via Inhibiting PI3K/Akt/Nrf2 Pathway. Carcinogenesis 2013, 34, 1806–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.L.; de Mejia, E.G. Interactions between Dietary Flavonoids Apigenin or Luteolin and Chemotherapeutic Drugs to Potentiate Anti-Proliferative Effect on Human Pancreatic Cancer Cells, in Vitro. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 60, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.-G.; Yu, P.; Li, J.-W.; Jiang, P.; Sun, J.; Wang, H.-Z.; Zhang, L.-D.; Wen, M.-B.; Bie, P. Apigenin Potentiates the Growth Inhibitory Effects by IKK-β-Mediated NF-ΚB Activation in Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Toxicol. Lett. 2014, 224, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.-Y.; Wu, T.-T.; Zhou, S.-H.; Bao, Y.-Y.; Wang, Q.-Y.; Fan, J.; Huang, Y.-P. Apigenin Suppresses GLUT-1 and p-AKT Expression to Enhance the Chemosensitivity to Cisplatin of Laryngeal Carcinoma Hep-2 Cells: An in Vitro Study. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2014, 7, 3938. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, Y.-Y.; Zhou, S.-H.; Lu, Z.-J.; Fan, J.; Huang, Y.-P. Inhibiting GLUT-1 Expression and PI3K/Akt Signaling Using Apigenin Improves the Radiosensitivity of Laryngeal Carcinoma in Vivo. Oncol. Rep. 2015, 34, 1805–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.-Y.; Liang, J.-Y.; Guo, X.-J.; Liu, L.; Guo, Y.-B. 5-Fluorouracil Combined with Apigenin Enhances Anticancer Activity through Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (ΔΨm)-Mediated Apoptosis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2015, 42, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, S.M.; Kang, J.G.; Bae, J.S.; Pae, H.O.; Lyu, Y.S.; Jeon, B.H. The Flavonoid Apigenin Ameliorates Cisplatin-Induced Nephrotoxicity through Reduction of P53 Activation and Promotion of PI3K/Akt Pathway in Human Renal Proximal Tubular Epithelial Cells. Evid. -Based Complementary Altern. Med. 2015, 2015, 186436 . [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaballah, H.H.; Gaber, R.A.; Mohamed, D.A. Apigenin Potentiates the Antitumor Activity of 5-FU on Solid Ehrlich Carcinoma: Crosstalk between Apoptotic and JNK-Mediated Autophagic Cell Death Platforms. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2017, 316, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, A.-M.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Ke, Z.-P. Apigenin Sensitizes BEL-7402/ADM Cells to Doxorubicin through Inhibiting MiR-101/Nrf2 Pathway. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 82085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, A.-M.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Hu, J.-N.; Ke, Z.-P. Apigenin Sensitizes Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells to Doxorubic through Regulating MiR-520b/ATG7 Axis. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2018, 280, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, L.; Zhao, X.; Cheng, Z.; Ma, J. Apigenin Induces Apoptosis and Reverses the Drug Resistance of Ovarian Cancer Cells. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2020, 13, 1987–1994. [Google Scholar]

- Thangasamy, T.; Sittadjody, S.; Mitchell, G.C.; Mendoza, E.E.; Radhakrishnan, V.M.; Limesand, K.H.; Burd, R. Quercetin Abrogates Chemoresistance in Melanoma Cells by Modulating ΔNp73. BMC Cancer 2010, 10, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang-Xin, L.; Wen-Yu, W.; Yao, C.U.I.; Xiao-Yan, L.; Yun, Z. Quercetin Enhances the Effects of 5-Fluorouracil-Mediated Growth Inhibition and Apoptosis of Esophageal Cancer Cells by Inhibiting NF-ΚB. Oncol. Lett. 2012, 4, 775–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, K.; Zhang, J.; Dong, Z. The Effect of Quercetin on Doxorubicin Cytotoxicity in Human Breast Cancer Cells. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. (Former. Curr. Med. Chem. -Anti-Cancer Agents) 2013, 13, 352–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciejczyk, A.; Surowiak, P. Quercetin Inhibits Proliferation and Increases Sensitivity of Ovarian Cancer Cells to Cisplatin and Paclitaxel. Ginekol. Pol. 2013, 84, 590–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, D.; Li, R.; Lan, Q. Quercetin Sensitizes Human Glioblastoma Cells to Temozolomide in Vitro via Inhibition of Hsp27. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2014, 35, 832–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Qiao, S.; Zhang, J.; Li, K. Quercetin Increase the Chemosensitivity of Breast Cancer Cells to Doxorubicin via PTEN/Akt Pathway. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. (Former. Curr. Med. Chem. -Anti-Cancer Agents) 2015, 15, 1185–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Lee, E.J.; Min, K.H.; Hur, G.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Shin, C.; Shim, J.J.; In, K.H. Quercetin Enhances Chemosensitivity to Gemcitabine in Lung Cancer Cells by Inhibiting Heat Shock Protein 70 Expression. Clin. Lung Cancer 2015, 16, e235–e243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Huang, C.; Ma, T.; Jiang, L.; Tang, L.; Shi, T.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, P.; Li, J. Reversal Effect of Quercetin on Multidrug Resistance via FZD7/β-Catenin Pathway in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. Phytomedicine 2018, 43, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y.; Xie, B.; Liang, Z.; Chen, J. Quercetin Reverses the Doxorubicin Resistance of Prostate Cancer Cells by Downregulating the Expression of C-Met. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 15, 2252–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, C.-Y.; Chen, S.-Y.; Kuo, C.-W.; Lu, C.-C.; Yen, G.-C. Quercetin Facilitates Cell Death and Chemosensitivity through RAGE/PI3K/AKT/MTOR Axis in Human Pancreatic Cancer Cells. J. Food Drug Anal. 2019, 27, 887–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Huang, J.; Yu, C.; Xiang, L.; Li, L.; Shi, D.; Lin, F. Quercetin Enhanced Paclitaxel Therapeutic Effects towards PC-3 Prostate Cancer through ER Stress Induction and ROS Production. OncoTargets Ther. 2020, 13, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawalizadeh, F.; Mohammadzadeh, G.; Khedri, A.; Rashidi, M. Quercetin Potentiates the Chemosensitivity of MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cells to 5-Fluorouracil. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 7733–7742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safi, A.; Heidarian, E.; Ahmadi, R. Quercetin Synergistically Enhances the Anticancer Efficacy of Docetaxel through Induction of Apoptosis and Modulation of PI3K/AKT, MAPK/ERK, and JAK/STAT3 Signaling Pathways in MDA-MB-231 Breast Cancer Cell Line. Int. J. Mol. Cell. Med. 2021, 10, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Yanqiu, H.; Linjuan, C.; Jin, W.; Hongjun, H.; Yongjin, S.; Guobin, X.; Hanyun, R. The Effects of Quercetin and Kaempferol on Multidrug Resistance and the Expression of Related Genes in Human Erythroleukemic K562/A Cells. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 10, 13399–13406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riahi-Chebbi, I.; Souid, S.; Othman, H.; Haoues, M.; Karoui, H.; Morel, A.; Srairi-Abid, N.; Essafi, M.; Essafi-Benkhadir, K. The Phenolic Compound Kaempferol Overcomes 5-Fluorouracil Resistance in Human Resistant LS174 Colon Cancer Cells. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Du, J.; Li, C.; Li, H.; Guo, H.; Li, Z. Kaempferol Can Reverse the 5-Fu Resistance of Colorectal Cancer Cells by Inhibiting PKM2-Mediated Glycolysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Feng, J.; Chen, X.; Guo, W.; Du, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zang, W.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, G. Myricetin Enhance Chemosensitivity of 5-Fluorouracil on Esophageal Carcinoma in Vitro and in Vivo. Cancer Cell Int. 2014, 14, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, A.-W.; Chen, Y.-Q.; Zhao, L.-Q.; Feng, J.-G. Myricetin Induces Apoptosis and Enhances Chemosensitivity in Ovarian Cancer Cells. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 13, 4974–4978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iriti, M.; Vitalini, S.; Arnold Apostolides, N.; El Beyrouthy, M. Chemical Composition and Antiradical Capacity of Essential Oils from Lebanese Medicinal Plants. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2014, 26, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Zhang, G.; Hu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Lan, H.; Shen, X.; Lv, Y.; Huang, L. Rutin Attenuates Sorafenib-Induced Chemoresistance and Autophagy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma by Regulating BANCR/MiRNA-590-5P/OLR1 Axis. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 17, 3595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Xie, J.; Peng, J.; Han, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Han, M.; Wang, C. Hispidulin Inhibits Proliferation and Enhances Chemosensitivity of Gallbladder Cancer Cells by Targeting HIF-1α. Exp. Cell Res. 2015, 332, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, L.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Chang, A.K.; Yang, Z.; Bi, X. Black Raspberry Anthocyanins Increased the Antiproliferative Effects of 5-Fluorouracil and Celecoxib in Colorectal Cancer Cells and Mouse Model. J. Funct. Foods 2021, 87, 104801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.H.; Bak, D.-H.; Chung, B.Y.; Bai, H.-W.; Kang, B.S. Delphinidin Enhances Radio-Therapeutic Effects via Autophagy Induction and JNK/MAPK Pathway Activation in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. Off. J. Korean Physiol. Soc. Korean Soc. Pharmacol. 2020, 24, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eguchi, H.; Matsunaga, H.; Onuma, S.; Yoshino, Y.; Matsunaga, T.; Ikari, A. Down-Regulation of Claudin-2 Expression by Cyanidin-3-Glucoside Enhances Sensitivity to Anticancer Drugs in the Spheroid of Human Lung Adenocarcinoma A549 Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, T.-Y.; Chung, Y.-C.; Hou, Y.-C.; Tsai, Y.-W.; Chen, C.-H.; Chang, H.-P.; Chou, J.-L.; Hsu, C.-P. Effects of Ellagic Acid on Chemosensitivity to 5-Fluorouracil in Colorectal Carcinoma Cells. Anticancer Res. 2012, 32, 4413–4418. [Google Scholar]

- Engelke, L.H.; Hamacher, A.; Proksch, P.; Kassack, M.U. Ellagic Acid and Resveratrol Prevent the Development of Cisplatin Resistance in the Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Cell Line A2780. J. Cancer 2016, 7, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-J.; Liao, H.-F.; Tsai, T.-H.; Wang, S.-Y.; Shiao, M.-S. Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester Preferentially Sensitizes CT26 Colorectal Adenocarcinoma to Ionizing Radiation without Affecting Bone Marrow Radioresponse. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2005, 63, 1252–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-H.; Chiu, J.-H.; Tseng, W.-S.; Wong, T.-T.; Chiou, S.-H.; Yen, S.-H. Antiproliferation and Radiosensitization of Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester on Human Medulloblastoma Cells. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2006, 57, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsunaga, T.; Tsuchimura, S.; Azuma, N.; Endo, S.; Ichihara, K.; Ikari, A. Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester Potentiates Gastric Cancer Cell Sensitivity to Doxorubicin and Cisplatin by Decreasing Proteasome Function. Anti-Cancer Drugs 2019, 30, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonoki, H.; Tanimae, A.; Furuta, T.; Endo, S.; Matsunaga, T.; Ichihara, K.; Ikari, A. Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester Down-Regulates Claudin-2 Expression at the Transcriptional and Post-Translational Levels and Enhances Chemosensitivity to Doxorubicin in Lung Adenocarcinoma A549 Cells. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2018, 56, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjaly, K.; Tiku, A.B. Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester Induces Radiosensitization via Inhibition of DNA Damage Repair in Androgen-Independent Prostate Cancer Cells. Environ. Toxicol. 2022, 37, 995–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthusamy, G.; Balupillai, A.; Ramasamy, K.; Shanmugam, M.; Gunaseelan, S.; Mary, B.; Prasad, N.R. Ferulic Acid Reverses ABCB1-Mediated Paclitaxel Resistance in MDR Cell Lines. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 786, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthusamy, G.; Gunaseelan, S.; Prasad, N.R. Ferulic Acid Reverses P-Glycoprotein-Mediated Multidrug Resistance via Inhibition of PI3K/Akt/NF-ΚB Signaling Pathway. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2019, 63, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, S.-K.; Noh, E.-K.; Yoon, D.-J.; Jo, J.-C.; Koh, S.; Baek, J.H.; Park, J.-H.; Min, Y.J.; Kim, H. Rosmarinic Acid Potentiates ATRA-Induced Macrophage Differentiation in Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia NB4 Cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 747, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Chen, D.; Liu, H.; Li, W.; Lu, J.; Feng, J. Rosmarinic Acid Reduces the Resistance of Gastric Carcinoma Cells to 5-Fluorouracil by Downregulating FOXO4-Targeting MiR-6785-5p. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 109, 2327–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, S.; Wei, C.; Rankin, G.O.; Rojanasakul, Y.; Ren, N.; Ye, X.; Chen, Y.C. Dietary Compound Proanthocyanidins from Chinese Bayberry (Myrica Rubra Sieb. et Zucc.) Leaves Inhibit Angiogenesis and Regulate Cell Cycle of Cisplatin-Resistant Ovarian Cancer Cells via Targeting Akt Pathway. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 40, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindranathan, P.; Pasham, D.; Goel, A. Oligomeric Proanthocyanidins (OPCs) from Grape Seed Extract Suppress the Activity of ABC Transporters in Overcoming Chemoresistance in Colorectal Cancer Cells. Carcinogenesis 2019, 40, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naus, P.J.; Henson, R.; Bleeker, G.; Wehbe, H.; Meng, F.; Patel, T. Tannic Acid Synergizes the Cytotoxicity of Chemotherapeutic Drugs in Human Cholangiocarcinoma by Modulating Drug Efflux Pathways. J. Hepatol. 2007, 46, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, N.; Zheng, X.; Wu, M.; Yang, L.; Li, X.; Chen, J. Tannic Acid Synergistically Enhances the Anticancer Efficacy of Cisplatin on Liver Cancer Cells through Mitochondria-Mediated Apoptosis. Oncol. Rep. 2019, 42, 2108–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Liu, W.; Gong, X.R.; Zhou, Y.B.; Lin, Y. Procyanidins Enhance the Chemotherapeutic Sensitivity of Laryngeal Carcinoma Cells to Cisplatin through Autophagy Pathway. Lin Chuang Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi J. Clin. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2018, 32, 447–456. [Google Scholar]

- Mady, F.M.; Shaker, M.A. Enhanced Anticancer Activity and Oral Bioavailability of Ellagic Acid through Encapsulation in Biodegradable Polymeric Nanoparticles. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017, 12, 7405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetin, A.; Biltekin, B.; Degirmencioglu, S. Ellagic Acid Enhances the Antitumor Efficacy of Bevacizumab in an in Vitro Glioblastoma Model. World Neurosurg. 2019, 132, e59–e65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetin, A.; Biltekin, B. Ellagic Acid Enhances Antitumor Efficacy of Temozolomide in an in Vitro Glioblastoma Model. Turk Neurosurg 2020, 30, 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-S.; Ho, J.-Y.; Yu, C.-P.; Cho, C.-J.; Wu, C.-L.; Huang, C.-S.; Gao, H.-W.; Yu, D.-S. Ellagic Acid Resensitizes Gemcitabine-Resistant Bladder Cancer Cells by Inhibiting Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Gemcitabine Transporters. Cancers 2021, 13, 2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.Y.; Ediriweera, M.K.; Ryu, J.Y.; Kim, H.Y.; Cho, S.K. Catechol Enhances Chemo-and Radio-Sensitivity by Targeting AMPK/Hippo Signaling in Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Oncol. Rep. 2021, 45, 1133–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).