Simple Summary

For cancer patients, many different reasons can cause financial burdens and economic threads. Sociodemographic factors, rural/remote location and income are known determinants for these vulnerable groups. This economic vulnerability is related to the reduced utilization of cancer care and the impact on outcome. Financial burden has been reported in many countries throughout the world and needs to be addressed as part of the sufficient quality of cancer care.

Abstract

Within healthcare systems in all countries, vulnerable groups of patients can be identified and are characterized by the reduced utilization of available healthcare. Many different reasons can be attributed to this observation, summarized as implementation barriers involving acceptance, accessibility, affordability, acceptability and quality of care. For many patients, cancer care is specifically associated with the occurrence of vulnerability due to the complex disease, very different target groups and delivery situations (from prevention to palliative care) as well as cost-intensive care. Sociodemographic factors, such as educational level, rural/remote location and income, are known determinants for these vulnerable groups. However, different forms of financial burdens likely influence this vulnerability in cancer care delivery in a distinct manner. In a narrative review, these socioeconomic challenges are summarized regarding their occurrence and consequences to current cancer care. Overall, besides direct costs such as for treatment, many facets of indirect costs including survivorship costs for the cancer patients and their social environment need to be considered regarding the impact on vulnerability, treatment compliance and abundance. In addition, individual cancer-related financial burden might also affect the society due to the loss of productivity and workforce availability. Healthcare providers are requested to address this vulnerability during the treatment of cancer patients.

1. Introduction

Currently, worldwide, 17.5 million cancer cases and 8.7 million deaths occur. During the last decade, their incidence raised by 33%, with population aging contributing 16%, population growth contributing 13% and changes in age-specific rates contributing 4% []. This transitional process in cancer care requirements [] will become even more important during the next two decades, especially in countries facing intensive epidemiological changes []. These effects are not only related to the acquisition of environmental and lifestyle risk factors but are also determined by regional differences in vulnerability, such as those caused by genetic background, race, microbiomes and cultural aspects, among others. In this context, the socioeconomic framework and financial burden of cancer care will likely gain much more importance, especially in vulnerable groups and for infrastructural development [,]. This economic burden of cancer contains expenditures on care in the primary, outpatient, emergency and inpatient settings, along with drugs. In addition, due to the improvements of cancer care, increasing cancer survivorship needs to be included. Furthermore, indirect costs due to lost earnings after premature death or unemployment/cancer-related disabilities, family caregiving and costs associated with individuals who temporarily or permanently left employment because of illness contribute to the overall economic burden of cancer []. Worldwide, these financial consequences vary in a wide range between the countries. For example, across EU countries, the annual cancer-related costs accounted for EUR 102 per citizen, on average, but varied to a large extent between EUR 16 per person in Bulgaria to EUR 184 per person in Luxembourg []. The impact of various cancer entities on these costs also varies considerably, which has been shown for malignant blood disorders [] and bladder cancer []. Interestingly, widely varying healthcare costs were found for countries with similar gross domestic product per capita (GDP). [] These differences are related to a major extent but are not limited to the willingness to pay by either the society or the individual cancer patient—depending on the healthcare system.

In a recent review, Yong et al. [] concluded that the individual willingness is intensively related to the expected outcome of cancer care, such as quality-adjusted life year (QALY), 1-year survival, quality of life (QoL) improvement and pain reduction. Economic development indicators contribute 4% of variation and increase the overall variation in incidence and mortality in breast cancer by approximately 5% []. However, similar empirical analyses investigating the priority of cancer care within the economic framework of national healthcare systems are not yet available. Since the economic burden for individuals is a key determinant of vulnerable groups in healthcare, we summarize the currently available literature on its impact on cancer care. Although vulnerable groups in this regard can be found to be more likely in low and middle income countries (LMIC), they are also present in industrial populations. Universal healthcare coverage criteria (UHC: availability, acceptability, accessibility, affordability, quality of care) were used as references.

Cancer patients can experience financial difficulties even within a publicly funded healthcare system []. These problems faced by cancer patients in Western countries have been widely explored, mostly for the Americas and the Western Pacific WHO regions [], but they may not be applicable in other countries due to sociocultural differences [,]. Especially, evaluations from LMICs have rarely been found yet. In this narrative review, we critically summarize the available analyses regarding the economic perspective of cancer care for vulnerable groups. The current constraints due to the COVID-19 pandemic are out of the scope of this review.

2. Materials and Methods

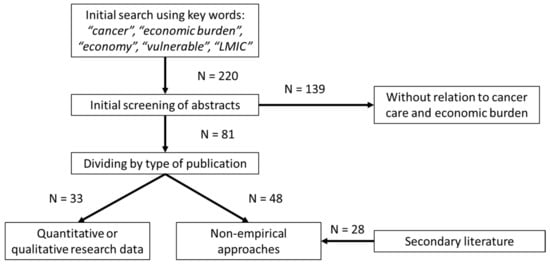

A literature search was conducted using the items “cancer”, “economic burden”, “economy”, “vulnerable” and “LMIC” (220 results). These publications were screened regarding the relationship to the UHC criteria, and papers without relation to cancer care and economic burden were eliminated (N = 139). The remaining papers (N = 81) were divided into a group containing quantitative or qualitative research data (N = 33) and publications focusing on non-empirical approaches (N = 48). In addition, secondary literature (N = 28) was used to supplement specific aspects of financial consequences (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Literature search and evaluation strategy (CONSORT diagram).

Data on financial difficulties or catastrophic health expenditures were extracted if available in the publications. The World Bank separates countries into four income categories by income using GDP per capita [], and this was applied: Low Income (LIC), Lower-Middle Income (LMIC), Upper-Middle Income (UMIC) and High Income (HIC).

3. Results

Three major areas of cancer care that interfere with the economic aspects of the individual burden creating specific vulnerable groups can be differentiated: acute direct involvement with cancer diagnosis, cancer prevention programs (mainly investigated for cervical cancer) and indirect involvement (esp. families facing childhood cancer, cancer survivorship and family-based caregiving). The qualitative and quantitative research data are summarized in Table 1. In this context, vulnerability refers to financially related limits in the affordability, accessibility, availability and acceptability of cancer care.

Table 1.

Quantitative and qualitative research approaches of the economic burden of cancer care (sorted by country and income status). Investigations that quantified individual financial consequences are highlighted in grey.

Some investigations addressed, in part, economic consequences for the society, such as the loss of the workforce and the costs for outcomes (rehabilitation, long-term complications, survivorship issues, etc.). For example, the costs and cost-effectiveness of treating childhood cancers in LMICs [] in terms of disability-adjusted life years (DALY), survival and country-specific life expectancy were recently compared with GDP products using the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards, although the identified body of evidence for these countries was still low and had high risks of bias, and true treatment costs were likely underestimated, Fung et al. [] and Zabih et al. [] concluded that overall childhood cancer treatment appears to be clinically effective and cost effective in LMICs, making sufficient cancer care achievable for these patients.

3.1. Affordibility

The affordability of cancer care has to be considered from two different perspectives: (A) the individual financial burden of the patients and their families due to cancer diagnosis and (B) the GDP-related affordability of cancer care for the society, which is mainly translated into limited availability of the respective resources. Financial consequences could arise due to the costs of treatment and the consequences of cancer.

Financial burden is a phenomenon that has been reported in many countries, contributing to the affordability of cancer care. For example, in the US, it was identified in about 50% of patients with cancer [], and about half of this could be attributed to direct treatment costs []. In Germany, job incomes dropped more than one forth within one year after cancer diagnosis, whereas in China, belonging to UMICs, this thread can reach an entire year’s worth of GDP per capita []. The highest incidence and relative extent of catastrophic healthcare expenditures appears to involve cancer patients and their families when they already belong to low-income groups [,,].

Table 2 provides an overview about the extent of financial difficulties or catastrophic health expenditures due to cancer diagnosis in directly involved cancer patients and in families affected by childhood cancer. Wide ranges result from investigations of different vulnerable groups and subpopulations, but in all available reports, the importance of financial burdens for cancer patients seems to be enormous. Financial catastrophe due to cancer was seen in many countries, which is in line with other non-communicable diseases (6–84% of the households, depending on the chosen catastrophe threshold) [].

Table 2.

Financial impact of cancer diagnosis on patients and their families in different countries.

Overall, the SES appears to seriously determine the affordability and related consequences for cancer patients. The respective predictors of worse financial burdens were the lack of health insurance, lower income, unemployment and younger age at cancer diagnosis [,]. For example, vulnerable groups in industrial countries, such as African American [] and Latino [] cancer survivors in the US, disproportionately experience financial burden due to their disease. Especially in LMICs, as shown in India, the financial instability of cancer patients is of high importance [].

However, the published evidence targeting the economic perspective of LMICs is biased towards costs incurred by the healthcare sector, and direct nonmedical as well as indirect costs were often not included []. Therefore, transferring results between countries is critical, but a loss of available income due to cancer seems to be a worldwide thread and important disease-related financial risks for these patients [].

3.2. Accessibility

Besides the availability of healthcare resources, the socioeconomic determinants of healthcare usage can vary between regions, such as between African and Latin American LIMCs, due to the limited accessibility of required specialties []. Older and rural populations appear to be specifically endangered by this impaired access to cancer care [,]. The travel costs for treatment likely impact accessibility and affordability in vulnerable populations, such as elderly groups [,]. In addition, financial burden does not arise entirely from access to clinical care, but it also relates to access constraints due to indirect financial consequences and restricted social lives, causing additional travel costs, overnight accommodation or family reunions [,].

3.3. Financial Burden Affects Quality of Care

All stages of cancers, from prevention and early detections up to advanced cancer stages, appear to be at risk for financial burdens []. These burdens usually have an effect early in cancer treatment, independent from cancer sites, and they were associated with worse health-related QoL, nonadherence to cancer medication, shorter survival, poorer prognosis and a greater risk of recurrence [,]. The treatment abandonment of these patients was also impacted by the affordability of effective drugs and the availability of essential monitoring for its timely recognition. Older and rural adults are again particularly vulnerable and more likely to experience financial hazards, worsening their economic lifestyle during cancer survivorship [,]. For example, such an impact can result in twofold rates of disabilities and activity limitations []. Related risk factors include functional impairment, comorbidities, social support, impaired cognitive function and psychological state and financial stress [].

Similarly, higher rates of treatment-related late effects and second primary malignancies [], as well as reduced mental health and additional distress [], are more likely to occur in financially challenged childhood cancer survivors. For example, nutritional factors with the interplay of malnutrition, the interference of one’s diet with drug absorption and the blood levels of cancer drugs seem to depend on financial conditions around the young cancer patients. [] Moreover, the compliance of these patients with cancer appears to be influenced by environmental factors, such as the exposure to viral infections and pesticides, which may also be related to the socioeconomic framework.

The financial framework and the public and clinical facets of global cancer care appear to intensively interfere with the implementation of prevention and the early detection of cancer [] and thus with the potential prognosis and outcome within the vulnerable groups. This area of cancer care is especially related to direct as well as indirect financial burden at the individual and societal level. Cervical cancer is used as an example for this tremendous impact [,], but the general picture can likely be transferred to other areas.

Despite worldwide efforts for HPV primary screening [], the implementation rates are still not sufficient, and socioeconomic factors, available resources and acceptance issues contribute to this limitation []. Furthermore, vaccine availability enforces industrial countries into a moral dilemma due to the recommendations of extended target groups (boys) on one side and the overall shortage for the entire population in LMICs on the other []. In LMICs, screening programs have struggled with quality issues, and this is, at least in part, related to the economic aspects of healthcare implementation []. Their potential target population also frequently suffers from inadequate coverage [] affected by reduced acceptance due the participants’ knowledge, attitudes and beliefs towards cervical cancer, which are to a large extent linked to individual economic factors and financial burden. For example, a higher age, a low educational status, a refugee/migrant or ethnic minority background, a menopausal status, housing conditions and a lack of insurance coverage appear to be linked with insufficient knowledge on the risk factors for cervical cancer. This results in false attitudes and perceptions on these preventive activities []. However, the empirical data investigating the relationship between individual socioeconomic aspects, the implementation of cancer prevention and subsequent negative effects on the quality of care and outcome, including the identification of special vulnerabilities due to the financial framework within the target groups, are not available yet.

Many countries have limited healthcare resources that can be made available for nationwide prevention programs, contributing to economic, political and societal instabilities. As a result of affordable national screening programs, the individual financial burden due to cancer will not only positively affect the direct costs of the prevention but will also improve indirect economic burdens, as described above [].

3.4. Acceptability and Social Environment

The individual SES of cancer patients is intensively related to their acceptance of care, which is not limited to immediate clinical aspects. For example, perceived financial vulnerability appears as a determinant for insufficient perceptions of environmental and psychosocial cancer risk factors embedded in social and cultural contexts []. Disparities in cancer development and access to care are related to a large extent to those acceptance risks and protective factors that can be directly or indirectly attributed to the economic burden of the respective population, such as on the basis of racial and ethnic minority status, economic disadvantages, disability status, gender, geographic environment and nation of origin [,,,,]. For childhood cancer survivors, important predictors of this vulnerability were female status, poor financial conditions, unemployment and poor education [,]. Furthermore, additional interference between economic burden and the acceptance of cancer care may be determined by varying socioeconomic milieu, such as families’ low SES, the long travel time, impaired family dynamics, the cancer center capacity, public awareness and governmental healthcare financing [].

Besides the direct costs for cancer patients, their social environment also faces financial burdens due to the care for the involved person. Since, in most healthcare systems, this thread is not covered or even systematically addressed by insurance, etc., the extent of resulting consequences for cancer treatment and outcome have rarely been investigated so far. Social and economic deficits due to family-based caregiving for patients with cancer may include lifestyle disruption, less socializing, greater out-of-pocket payment and lost productivity costs []. Female partners are more vulnerable for these consequences, including personal life strain, social relations, financial burden and intrinsic rewards [].

Pediatric cancer-induced financial distress and its adverse effects on parents is well documented []. The economic burden of these family members is not only an affordability barrier, but it also leads to reduced QoL and sickness of the family members, with potential worsening of the economic situation []. Moral distress within the families and reduced cancer care acceptance can result as consequence of the financial thread. The responsibility of healthcare providers to secure cancer care access for structurally vulnerable patients frequently relates to patients’ financial constraints and the resulting acceptability barriers to avoiding these conflicts [].

The financial distress can likely induce cost-coping strategies at the individual level that interfere with treatment acceptance and compliance []. In addition, in industrial countries, supportive strategies, such as cancer care navigators or outreach programs, have been developed for the improvement of cancer care acceptance in these vulnerable patient groups []. Furthermore, social workers involved in the psychosocial treatment of cancer patients are requested to assess and address the financial and logistic aspects of life for comprehensive cancer care []. However, for LMICs, such strategies have not been reported and have likely not been implemented yet.

3.5. Availability

Cancer care usage in LMICs and, at least in part, in vulnerable groups in HIC is unevenly distributed throughout the different clinical specialties. For example, barriers to access, including inequalities in financial protection (mainly out-of-pocket payment), remain a fundamental challenge to providing surgical care or histopathological diagnostics []. Innovations in leapfrog technology and low-cost point-of-care tests may contribute to a reduction of the financial burden in LMICs [].

For countries with limited economic resources for cancer care, various strategies have been recommended to provide the best care under the given conditions considering the existing financial framework (mainly targeting affordability and availability). Low-tech treatment protocols, such as switching from complex surgery to radiotherapy [] or the usage of low-cost diagnostic procedures [,], were discussed. Even this availability in LMICs is very much limited [,,] and correlates with the regional economic situation and outcome []. Additional examples were published for cervical [] and pediatric cancer [,]. Alternatives might be the twinning of LMICs with high income nations [,,], surgical mentorship, companion training programs [] or the implementation of telemedicine [,] for the availability of specialty support.

These differences in diagnostic and treatment options, as determined by the given economic framework, are not limited to clinical availability but are furthermore related to participation in clinical research and access to innovation, respectively, due to financial limitations in these countries [,]. For example, in evaluations of breast cancer care, LMICs (2%) and Sub-Saharan Africa (9%) were grossly underrepresented []. However, access or acceptance bias in clinical research is also an issue in industrial countries, and vulnerable groups are likely disproportionately represented in cancer trials, resulting in severe selection as well as methodological bias. The restricted applicability of the evidence in LMICs provided by those trials that were only performed in certain areas worldwide and do not represent vulnerable groups accordingly leads to a worsening of cancer care, especially in these patient groups.

4. Discussion

More than a decade ago, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) published their Guidance Statement on the Cost of Cancer Care, reflecting the increasing costs and financial burdens of cancer care, with a special focus towards the most vulnerable group, the cancer patients [,]. The addressed needs may currently have an even higher importance—not only for American patients but also for patients in other countries that face the incomplete coverage of cancer care by insurance or other backgrounds:

- Recognition cost of care discussions between the patient and physician as an important component of high-quality care;

- The provision of educational and support tools for cancer care providers promoting effective cost-related communication;

- Resource development to include the cost awareness of cancer care as part of shared decision making.

However, these requests are based on an existing patient–physician relationship and require that cancer patients have already found their way to cancer care. Therefore, the needs should be supplemented by bullet points related to public health challenges, such as for prevention and early detection:

- The identification and active targeting of vulnerable groups for cancer that are still outside the existing cancer care structures but should be addressed for improved prognosis and outcome.

Furthermore, numerous factors related to indirect costs for cancer care and determinants of financial vulnerability need to be considered:

- The recognition of different levels and reasons for financial or socioeconomical vulnerability as part of individual medical history.

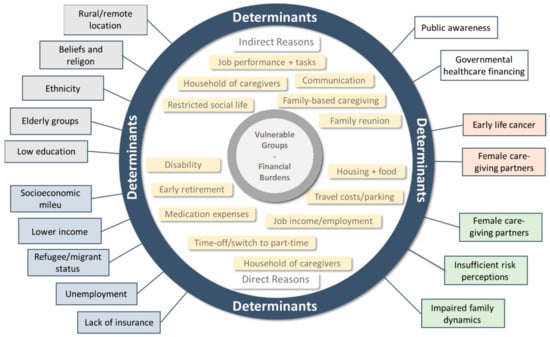

The various aspects of the SES of cancer patients appear to be the most important determinants of their individual vulnerability regarding the affordability, accessibility and acceptability of cancer care. The same factors intensively affect the financial burden of these patient groups, resulting in the worsening of their cancer care coverage. In addition, disease-related reasons and public aspects can influence the financial burden and vulnerability of cancer patients (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Direct and indirect reasons and determinants (grey: demographic; blue: economic; white: public; red: disease-related; green: social) of financial burden in vulnerable groups for cancer care.

Targeting vulnerable groups and their financial burden requires structured and comparable reporting of the entire cancer care processes. Usually, financial burden, economic hazards and related threads are solely investigated and discussed from the individual perspective of the cancer patients and sometimes of their social environment. However, there are additional economic effects on the society which are mainly out of focus when investigating cancer care. Reduced workforce availability, lower employment rates and premature retirement, among others, which are related to the direct cancer patients and their caregivers, may have negative consequences for a nation’s economy.

5. Conclusions

Non-communicable diseases, especially cancer, impose a substantial and growing global impact on families and impoverishment in all continents and at all income levels. The true extent, however, remains difficult to analyze due to the heterogeneity across existing studies in terms of the populations studied, the determinants considered, the outcomes reported and the measures employed. The impact that is exerted on the patients themselves, their families and their perspectives is likely to be underestimated. Important (socio)economic domains, such as indirect financial burden, economic handling and relief strategies and the inclusion of marginalized and vulnerable people who do not seek healthcare due to financial reasons, are underrepresented in the literature. Given the scarcity of information on specific regions, further research is required to estimate the impact of cancer diagnoses on households/families and impoverishment in LMICs, especially the Middle Eastern, African and Latin American regions []. However, the evaluation of financial burden, its determinants and its relationship with other aspects of the UHC criteria is not a phenomenon limited to these countries and has comparable importance for certain populations and patient groups in industrial countries.

The vulnerability of cancer patients due to financial burden and economic impact can be determined by various factors differing in certain subgroups, regions or countries. Similarly, the resulting consequences, such as treatment compliance, abandonment, the acceptance of care, impaired QoL, etc., depend on the specific environment of each cancer patient. This requires setting the right incentives to motivate all participating groups, including patients, healthcare providers, healthcare politicians and the society [,], and should be accompanied by evaluation strategies.

Research on cancer prevention, detection and management with a focus on vulnerable groups should not be limited to their specific risk factors, carcinogens and interactions between genetic and environmental factors, among other clinical and epidemiological topics []; rather, it requires additional efforts regarding implementation and outcome research to understand barriers and economic constraints for improved cancer care. This might require the adaptation of existing research methodologies, such as the consideration of regional distribution in trial recruitment, the potential worldwide transferability of evidence, modified or novel trial endpoints and statistical strategies for handling socioeconomic cofactors [,].

Author Contributions

Both authors (J.H. and J.S.) are fully responsible for the entire manuscript contributions. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

J.H. is the CEO of the Institute for Public Health and Health Sciences, Muenster, Germany. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Global Burden of Disease Cancer Collaboration. Global, Regional, and National Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Years of Life Lost, Years Lived With Disability, and Disability-Adjusted Life-years for 32 Cancer Groups, 1990 to 2015: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. JAMA Oncol. 2017, 3, 524–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaccarella, S.; Bray, F. Are U.S. trends a barometer of future cancer transitions in emerging economies? Int. J. Cancer 2020, 146, 1499–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, M.; Kalra, S. Epidemiological transition in South-East Asia and its Public Health Implications. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2020, 70, 1661–1663. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Haier, J.; Sleeman, J.; Schäfers, J. Cancer care in low- and middle-income countries. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2019, 36, 477–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khera, N.; Holland, J.C.; Griffin, J.M. Setting the stage for universal financial distress screening in routine cancer care. Cancer 2017, 123, 4092–4096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luengo-Fernandez, R.; Leal, J.; Gray, A.; Sullivan, R. Economic burden of cancer across the European Union: A population-based cost analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013, 14, 1165–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, R.; Leal, J.; Sullivan, R.; Luengo-Fernandez, R. Economic burden of malignant blood disorders across Europe: A population-based cost analysis. Lancet Haematol. 2016, 3, e362–e370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, J.; Luengo-Fernandez, R.; Sullivan, R.; Witjes, J.A. Economic Burden of Bladder Cancer Across the European Union. Eur. Urol. 2016, 69, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, R.H.; French, D.; Maughan, T.; Adams, R.; Allemani, C.; Minicozzi, P.; Coleman, M.P.; McFerran, E.; Sullivan, R.; Lawler, M. The economic burden of colorectal cancer across Europe: A population-based cost-of-illness study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 6, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, A.S.J.; Lim, Y.H.; Cheong, M.W.L.; Hamzah, E.; Teoh, S.L. Willingness-to-pay for cancer treatment and outcome: A systematic review. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellanger, M.; Zeinomar, N.; Tehranifar, P.; Terry, M.B. Are Global Breast Cancer Incidence and Mortality Patterns Related to Country-Specific Economic Development and Prevention Strategies? J. Glob. Oncol. 2018, 4, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, C.; Berkovic, D.; Wei, A.; Zomer, E.; Liew, D.; Ayton, D. ‘If I don’t work, I don’t get paid’: An Australian qualitative exploration of the financial impacts of acute myeloid leukaemia. Health Soc. Care Community 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaspers, L.; Colpani, V.; Chaker, L.; Van Der Lee, S.J.; Muka, T.; Imo, D.; Mendis, S.; Chowdhury, R.; Bramer, W.M.; Falla, A.; et al. The global impact of non-communicable diseases on households and impoverishment: A systematic review. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2015, 30, 163–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wajid, M.; Rajkumar, E.; Romate, J.; George, A.J.; Lakshmi, R. Exploring the problems faced by patients living with advanced cancer in Bengaluru, India. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haier, J.; Sleeman, J.; Schäfers, J. Sociocultural incentives for cancer care implementation. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2020, 37, 561–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank: Country Classification. Available online: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519 (accessed on 4 April 2022).

- Fung, A.; Horton, S.; Zabih, V.; Denburg, A.; Gupta, S. Cost and cost-effectiveness of childhood cancer treatment in low-income and middle-income countries: A systematic review. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 4, e001825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabih, W.; Thota, A.B.; Mbah, G.; Freccero, P.; Gupta, S.; Denburg, A.E. Interventions to improve early detection of childhood cancer in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2020, 67, e28761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.K.; Yoon, S.Y.; Taib, N.A.M.; Shabaruddin, F.H.; Dahlui, M.; Woo, Y.L.; Thong, M.K.; Teo, S.H.; Chaiyakunapruk, N. Is BRCA Mutation Testing Cost Effective for Early Stage Breast Cancer Patients Compared to Routine Clinical Surveillance? The Case of an Upper Middle-Income Country in Asia. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 2018, 16, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, D.; Schlander, M. Income loss after a cancer diagnosis in Germany: An analysis based on the socio-economic panel survey. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 3726–3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riza, E.; Karakosta, A.; Tsiampalis, T.; Lazarou, D.; Karachaliou, A.; Ntelis, S.; Karageorgiou, V.; Psaltopoulou, T. Knowledge, Attitudes and Perceptions about Cervical Cancer Risk, Prevention and Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) in Vulnerable Women in Greece. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balfe, M.; Butow, P.; O’Sullivan, E.; Gooberman-Hill, R.; Timmons, A.; Sharp, L. The financial impact of head and neck cancer caregiving: A qualitative study. Psychooncology 2016, 25, 1441–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baanders, A.N.; Heijmans, M.J.W.M. The impact of chronic diseases: The partner’s perspective. Fam. Community Health 2007, 30, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahão, R.; Huynh, J.C.; Benjamin, D.J.; Li, Q.W.; Winestone, L.E.; Muffly, L.; Keegan, T.H.M. Chronic medical conditions and late effects after acute myeloid leukaemia in adolescents and young adults: A population-based study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 50, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuero, A.; Benz, R.; McNees, P.; Meneses, K. Co-morbidity and predictors of health status in older rural breast cancer survivors. Springerplus 2014, 3, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, C.; BrintzenhofeSzoc, K. Financial Quality of Life for Patients With Cancer: An Exploratory Study. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2015, 33, 377–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastert, T.A.; Kirchhoff, A.C.; Banegas, M.P.; Morales, J.F.; Nair, M.; Beebe-Dimmer, J.L.; Pandolfi, S.S.; Baird, T.E.; Schwartz, A.G. Work changes and individual, cancer-related, and work-related predictors of decreased work participation among African American cancer survivors. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 9168–9177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, N.Y.; Battaglia, T.A.; Gupta-Lawrence, R.; Schiller, J.; Gunn, C.; Festa, K.; Nelson, K.; Flacks, J.; Morton, S.J.; Rosen, J.E. Burden of socio-legal concerns among vulnerable patients seeking cancer care services at an urban safety-net hospital: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.K.; Xiong, X.; Brown, J.; Horras, A.; Yuan, J.; Li, M. Impact of Cost-Related Medication Nonadherence on Economic Burdens, Productivity Loss, and Functional Abilities: Management of Cancer Survivors in Medicare. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 706289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedjat-Haiem, F.R.; Cadet, T.; Parada, H., Jr.; Jones, T.; Jimenez, E.E.; Thompson, B.; Wells, K.J.; Mishra, S.I. Financial Hardship and Health Related Quality of Life Among Older Latinos With Chronic Diseases. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2021, 38, 938–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, G.K.; Kirchhoff, A.C.; Recklitis, C.; Krull, K.R.; Kuhlthau, K.A.; Nathan, P.C.; Rabin, J.; Armstrong, G.T.; Leisenring, W.; Robison, L.L.; et al. Mental health insurance access and utilization among childhood cancer survivors: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J. Cancer Surviv. 2018, 12, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santacroce, S.J.; Killela, M.K.; Kerr, G.; Leckey, J.A.; Kneipp, S.M. Fathers’ psychological responses to pediatric cancer-induced financial distress. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2020, 67, e28281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangka, F.K.; Subramanian, S.; Jones, M.; Edwards, P.; Flanigan, T.; Kaganova, Y.; Smith, K.W.; Thomas, C.C.; Hawkins, N.A.; Rodriguez, J.; et al. Insurance Coverage, Employment Status, and Financial Well-Being of Young Women Diagnosed with Breast Cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2020, 29, 616–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Cai, H.; Wang, C.; Guo, C.; He, Z.; Ke, Y. Economic burden of gastrointestinal cancer under the protection of the New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme in a region of rural China with high incidence of oesophageal cancer: Cross-sectional survey. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2016, 21, 907–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sui, M.; Zeng, X.; Tan, W.J.; Tao, S.; Liu, R.; Liu, B.; Ma, W.; Huang, W.; Yu, H. Catastrophic health expenditures of households living with pediatric leukemia in China. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 6802–6812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.-Y.; Shi, J.-F.; Fu, W.-Q.; Zhang, X.; Liu, G.-X.; Chen, W.-Q.; He, J. Catastrophic health expenditure and its determinants in households with lung cancer patients in China: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.-Y.; Shi, J.-F.; Fu, W.-Q.; Zhang, X.; Liu, G.-X.; Chen, W.-Q.; He, J. Catastrophic Health Expenditure and Its Determinants Among Households With Breast Cancer Patients in China: A Multicentre, Cross-Sectional Survey. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 704700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastor, A.; Mohanty, S.K. Disease-specific out-of-pocket and catastrophic health expenditure on hospitalization in India: Do Indian households face distress health financing? PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, C.; Harding, R.; Teo, I.; Ozdemir, S.; Koh, G.C.H.; Neo, P.; Lee, L.H.; Kanesvaran, R.; Finkelstein, E.; COMPASS Study Team. Financial difficulties are associated with greater total pain and suffering among patients with advanced cancer: Results from the COMPASS study. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 3781–3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhakta, N.; Martiniuk, A.L.C.; Gupta, S.; Howard, S.C. The cost effectiveness of treating paediatric cancer in low-income and middle-income countries: A case-study approach using acute lymphocytic leukaemia in Brazil and Burkitt lymphoma in Malawi. Arch. Dis. Child. 2013, 98, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velandia, M.R.; De Aprendizaje, S.N.; Moreno, S.P.C.; De Colombia, U.N. Family Economic Burden Associated to Caring for Children with Cancer. Investig. Educ. Enferm. 2018, 36, e07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger-Saldaña, K.; Ventosa-Santaulària, D.; Miranda, A.; Verduzco-Bustos, G. Barriers and Explanatory Mechanisms of Delays in the Patient and Diagnosis Intervals of Care for Breast Cancer in Mexico. Oncologist 2018, 23, 440–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agulnik, A.; Antillon-Klussmann, F.; Vasquez, D.J.S.; Arango, R.; Moran, E.; Lopez, V.; Rodriguez-Galindo, C.; Bhakta, N. Cost-benefit analysis of implementing a pediatric early warning system at a pediatric oncology hospital in a low-middle income country. Cancer 2019, 125, 4052–4058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denburg, A.E.; Laher, N.; Mutyaba, I.; McGoldrick, S.; Kambugu, J.; Sessle, E.; Orem, J.; Casper, C. The cost effectiveness of treating Burkitt lymphoma in Uganda. Cancer 2019, 125, 1918–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACTION Study Group. Policy and priorities for national cancer control planning in low- and middle-income countries: Lessons from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Costs in Oncology prospective cohort study. Eur. J. Cancer 2017, 74, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, P.; Lam, C.; Kaur, G.; Itriago, E.; Ribeiro, R.C.; Arora, R. Determinants of Treatment Abandonment in Childhood Cancer: Results from a Global Survey. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchanda, R.; Sun, L.; Patel, S.; Evans, O.; Wilschut, J.; De Freitas Lopes, A.C.; Gaba, F.; Brentnall, A.; Duffy, S.; Cui, B.; et al. Economic Evaluation of Population-Based BRCA1/BRCA2 Mutation Testing across Multiple Countries and Health Systems. Cancers 2020, 12, 1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, N.; Hayes, L.; Basta, N.; McNally, R.J. International trends in the incidence of brain tumours in children and young-adults and their association with indicators of economic development. Cancer Epidemiol. 2021, 74, 102006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangka, F.K.; Subramanian, S.; Edwards, P.; Cole-Beebe, M.; Parkin, D.M.; Bray, F.; Joseph, R.; Mery, L.; Saraiya, M.; Cancer Registration Economic Evaluation Participants. Resource requirements for cancer registration in areas with limited resources: Analysis of cost data from four low- and middle-income countries. Cancer Epidemiol. 2016, 45 (Suppl. S1), S50–S58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.L.; Lopez-Olivo, M.; Advani, P.G.; Ning, M.S.; Geng, Y.; Giordano, S.H.; Volk, R.J. Financial Burdens of Cancer Treatment: A Systematic Review of Risk Factors and Outcomes. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2019, 17, 1184–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedjat-Haiem, F.R.; Carrion, I.; Lorenz, K.A.; Ell, K.; Palinkas, L. Psychosocial concerns among Latinas with life-limiting advanced cancers. Omega-J. Death Dying 2013, 67, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erfani, P.; Bhangdia, K.; Stauber, C.; Mugunga, J.C.; Pace, L.E.; Fadelu, T. Economic Evaluations of Breast Cancer Care in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Scoping Review. Oncologist 2021, 26, e1406–e1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishr, M.K.; Zaghloul, M.S. Radiation Therapy Availability in Africa and Latin America: Two Models of Low and Middle Income Countries. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2018, 102, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clipp, E.C.; Carver, E.H.; Pollak, K.I.; Puleo, E.; Emmons, K.M.; Onken, J.; Farraye, F.A.; McBride, C.M. Age-related vulnerabilities of older adults with colon adenomas: Evidence from Project Prevent. Cancer 2004, 100, 1085–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, J.M.; Bensink, M.; Bowers, C.; Hollenbeak, C.S. Travel burden associated with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor administration in a Medicare aged population: A geospatial analysis. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2018, 34, 1351–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeder-Hayes, K.E.; Anderson, B.O. Breast Cancer Disparities at Home and Abroad: A Review of the Challenges and Opportunities for System-Level Change. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 2655–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.E.; Fugett, S. Financial Toxicity: Limitations and Challenges When Caring for Older Adult Patients with Cancer. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2018, 22, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klepin, H.; Mohile, S.; Hurria, A. Geriatric assessment in older patients with breast cancer. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2009, 7, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Malhotra, H.; Radich, J.; Garcia-Gonzalez, P. Meeting the needs of CML patients in resource-poor countries. Hematol. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program 2019, 2019, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soi, C.; Gimbel, S.; Chilundo, B.; Muchanga, V.; Matsinhe, L.; Sherr, K. Human papillomavirus vaccine delivery in Mozambique: Identification of implementation performance drivers using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR). Implement. Sci. 2018, 13, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steben, M.; Jeronimo, J.; Wittet, S.; Lamontagne, D.S.; Ogilvie, G.; Jensen, C.; Smith, J.; Franceschi, S. Upgrading public health programs for human papillomavirus prevention and control is possible in low- and middle-income countries. Vaccine 2012, 30 (Suppl. S5), F183–F191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allanson, E.R.; Powell, A.; Bulsara, M.; Lee, H.L.; Denny, L.; Leung, Y.; Cohen, P. Morbidity after surgical management of cervical cancer in low and middle income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chargari, C.; Arbyn, M.; Leary, A.; Abu-Rustum, N.; Basu, P.; Bray, F.; Chopra, S.; Nout, R.; Tanderup, K.; Viswanathan, A.; et al. Increasing global accessibility to high-level treatments for cervical cancers. Gynecol. Oncol. 2021, 164, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fesenfeld, M.; Hutubessy, R.; Jit, M. Cost-effectiveness of human papillomavirus vaccination in low and middle income countries: A systematic review. Vaccine 2013, 31, 3786–3804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colzani, E.; Johansen, K.; Johnson, H.; Celentano, L.P. Human papillomavirus vaccination in the European Union/European Economic Area and globally: A moral dilemma. Eurosurveillance 2021, 26, 2001659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahasrabuddhe, V.V.; Parham, G.P.; Mwanahamuntu, M.H.; Vermund, S.H. Cervical cancer prevention in low- and middle-income countries: Feasible, affordable, essential. Cancer Prev. Res. 2012, 5, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimple, S.A.; Mishra, G.A. Global strategies for cervical cancer prevention and screening. Minerva Ginecol. 2019, 71, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maza, M.; Gage, J.C. Considerations for HPV primary screening in lower-middle income countries. Prev. Med. 2017, 98, 39–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peretti-Watel, P.; Fressard, L.; Bocquier, A.; Verger, P. Perceptions of cancer risk factors and socioeconomic status. A French study. Prev. Med. Rep. 2016, 3, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Massetti, G.M.; Thomas, C.C.; Ragan, K.R. Disparities in the Context of Opportunities for Cancer Prevention in Early Life. Pediatrics 2016, 138 (Suppl. S1), S65–S77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Yeh, S.; Martiniuk, A.; Lam, C.; Chen, H.-Y.; Liu, Y.-L.; Tsimicalis, A.; Arora, R.; Ribeiro, R.C. The magnitude and predictors of abandonment of therapy in paediatric acute leukaemia in middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Cancer 2013, 49, 2555–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seah, T.; Zhang, C.; Halbert, J.; Prabha, S.; Gupta, S. The magnitude and predictors of therapy abandonment in pediatric central nervous system tumors in low- and middle-income countries: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2019, 66, e27692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massimo, L.; Zarri, D.; Caprino, D. Psychosocial aspects of survivors of childhood cancer or leukemia. Minerva Pediatr. 2005, 57, 389–397. [Google Scholar]

- Massimo, L.M.; Caprino, D. The truly healthy adult survivor of childhood cancer: Inside feelings and behaviors. Minerva Pediatr. 2007, 59, 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Haley, W.E. Family caregivers of elderly patients with cancer: Understanding and minimizing the burden of care. J. Support. Oncol. 2003, 1 (Suppl. S2), 25–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ardy, K.K.; Bonner, M.J.; Masi, R.; Hutchinson, K.C.; Willard, V.W.; Rosoff, P.M. Psychosocial functioning in parents of adult survivors of childhood cancer. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2008, 30, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armin, J.S. Administrative (in) Visibility of Patient Structural Vulnerability and the Hierarchy of Moral Distress among Healthcare Staff. Med. Anthropol Q. 2019, 33, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bestvina, C.M.; Zullig, L.L.; Zafar, S.Y. The implications of out-of-pocket cost of cancer treatment in the USA: A critical appraisal of the literature. Future Oncol. 2014, 10, 2189–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moy, B.; Chabner, B.A. Patient navigator programs, cancer disparities, and the patient protection and affordable care act. Oncologist 2011, 16, 926–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoroh, J.S.; Chia, V.; Oliver, E.A.; Dharmawardene, M.; Riviello, R. Strengthening Health Systems of Developing Countries: Inclusion of Surgery in Universal Health Coverage. World J. Surg. 2015, 39, 1867–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martei, Y.M.; Pace, L.E.; Brock, J.E.; Shulman, L.N. Breast Cancer in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Why We Need Pathology Capability to Solve This Challenge. Clin. Lab. Med. 2018, 38, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskar, R.; Itahana, K. Radiation therapy and cancer control in developing countries: Can we save more lives? Int. J. Med. Sci. 2017, 14, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, R.; Obstein, K.L.; Scozzarro, G.; Di Natali, C.; Beccani, M.; Morgan, D.R.; Valdastri, P. A platform for gastric cancer screening in low- and middle-income countries. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2015, 62, 1324–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, S.M.; Berg, W.A.; Podilchuk, C.; Aldrete, A.L.L.; Mascareño, A.P.G.; Pathicherikollamparambil, K.; Sankarasubramanian, A.; Eshraghi, L.; Mammone, R. Palpable Breast Lump Triage by Minimally Trained Operators in Mexico Using Computer-Assisted Diagnosis and Low-Cost Ultrasound. J. Glob. Oncol. 2018, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, S.; Xu, M.J.; Yeager, A.; Rosman, L.; Groen, R.S.; Chackungal, S.; Rodin, D.; Mangaali, M.; Nurkic, S.; Fernandes, A.; et al. A systematic review of radiotherapy capacity in low- and middle-income countries. Front. Oncol. 2015, 4, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, M.B.; Zubizarreta, E.H.; Rubio, J.A.P. Radiotherapy in small countries. Cancer Epidemiol. 2017, 50, 257–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.V.; Bhasker, S. Development of protocol for the management of cervical cancer symptoms in resource-constrained developing countries. Support. Care Cancer 2015, 23, 581–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.; Hans, R.; Totadri, S.; Trehan, A.; Sharma, R.R.; Menon, P.; Kapoor, R.; Saxena, A.K.; Mittal, B.R.; Bhatia, P.; et al. Autologous stem cell transplant for high-risk neuroblastoma: Achieving cure with low-cost adaptations. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2020, 67, e28273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkes, J.; Hendricks, M.; Ssenyonga, P.; Mugamba, J.; Molyneux, E.; Meeteren, A.S.; Qaddoumi, I.; Fieggen, G.; Luna-Fineman, S.; Howard, S.; et al. SIOP PODC adapted treatment recommendations for standard-risk medulloblastoma in low and middle income settings. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2015, 62, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Lamki, Z. Improving Cancer Care for Children in the Developing World: Challenges and Strategies. Curr. Pediatr. Rev. 2017, 13, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingham, T.P.; Alatise, O.I. Establishing translational and clinical cancer research collaborations between high- and low-income countries. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 22, 741–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwar, V.S.; Schwartz, K.R.; Salifu, N.; Abdelfattah, A.M.; Anim, B.; Cayrol, J.; Sniderman, E.; Eden, T. The role of twinning in sustainable care for children with cancer: A TIPPing point? SIOP PODC Working Group on Twinning, Collaboration, and Support. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2020, 67, e28667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascha, V.A.M.; Sun, L.; Gilardino, R.; Legood, R. Telemammography for breast cancer screening: A cost-effective approach in Argentina. BMJ Healthc. Inform. 2021, 28, e100351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pesec, M.; Sherertz, T. Global health from a cancer care perspective. Future Oncol. 2015, 11, 2235–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, J.C.; Sharma, S.; Del Paggio, J.C.; Hopman, W.M.; Gyawali, B.; Mukherji, D.; Hammad, N.; Pramesh, C.S.; Aggarwal, A.; Sullivan, R.; et al. An Analysis of Contemporary Oncology Randomized Clinical Trials From Low/Middle-Income vs. High-Income Countries. JAMA Oncol. 2021, 7, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magrath, I.; Epelman, S. Cancer in adolescents and young adults in countries with limited resources. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2013, 15, 332–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meropol, N.J.; Schrag, D.; Smith, T.; Mulvey, T.M.; Langdon, R.M., Jr.; Blum, D.; Ubel, P.A.; Schnipper, L.E. American Society of Clinical Oncology guidance statement: The cost of cancer care. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 3868–3874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moy, B.; Polite, B.N.; Halpern, M.T.; Stranne, S.K.; Winer, E.P.; Wollins, D.S.; Newman, L.A. American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement: Opportunities in the patient protection and affordable care act to reduce cancer care disparities. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 3816–3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haier, J.; Sleeman, J.; Schäfers, J. Guidance of healthcare development for metastatic cancer patients as an example for setting incentives. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2020, 37, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haier, J.; Sleeman, J.; Schäfers, J. Assessment of incentivizing effects for cancer care frameworks. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2020, 37, 447–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankaranarayanan, R.; Boffetta, P. Research on cancer prevention, detection and management in low- and medium-income countries. Ann. Oncol. 2010, 21, 1935–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Means, A.R.; Kemp, C.G.; Gwayi-Chore, M.-C.; Gimbel, S.; Soi, C.; Sherr, K.; Wagenaar, B.H.; Wasserheit, J.N.; Weiner, B. Evaluating and optimizing the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR) for use in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Implement. Sci. 2020, 15, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kularatna, S.; Whitty, J.A.; Johnson, N.W.; Scuffham, P.A. Study protocol for valuing EQ-5D-3L and EORTC-8D health states in a representative population sample in Sri Lanka. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2013, 11, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).