Abstract

In the past few years, several mushroom poisoning incidents caused by Omphalotus species have occurred in China. In addition to O. guepiniformis and O. olearius, a new white Omphalotus species, O. yunnanensis, was discovered in Southwestern and Southern China based on morphological, molecular and toxin-detection evidence. Omphalotus yunnanensis is characterized by its small, cream to white basidiomata with a hygrophanous pileal surface, non-bioluminescent lamellae, broadly ellipsoid to subglobose basidiospores (8–12.5 × 7–10 μm), fusoid to ventricose cheilocystidia with occasional apical outgrowths, cream to white pileipellis composed of thick-walled, subsoil to solid hyphae, clavate, and fusoid to ventricose caulocystidia with occasional apical outgrowths. The species has been discovered in tropical to subtropical areas in Southwestern and Southern China. Phylogenetic analyses based on ITS and nrLSU showed that the new species clustered with the Australasian species O. nidiformis, but can be easily distinguished by its smaller, white to cream pileus, non-bioluminescent lamellae, larger basidiospores and growing on Fagaceae species. Illudin S was detected in this new species using UPLC-MS/MS, at 6.98 mg/kg of the content (dry weight), while no illudin M was detected.

Key Contribution:

After poisoning incidents, a new poisonous mushroom, Omphalotus yunnanensis, was discovered based on morphological, molecular and toxin-detection evidence from China. Illudin S, which results in gastroenteritis poisoning, was detected.

1. Introduction

The genus Omphalotus Fayod (Omphalotaceae, Agaricales) comprises saprotrophic or weakly parasitic wood-decaying fungi, characterized by distinct morphological characters: funnel-shaped to flabelliform basidiomata; decurrent, luminescent (or not) lamellae; white to pale-colored; ellipsoid; globose to subglobose; thin- to thick-walled; glabrous to finely rough basidiospores; without pleurocystidia; and with cheilocystidia often bearing apical outgrowths and hyphae with clamp connections [1]. The genus includes nearly ten recognized species, four of which have been recorded in China: O. flagelliformis Zhu L. Yang & B. Feng (a new species described in 2013), O. guepiniformis (Berk.) Neda (syn. O. japonicus), O. mangensis (Jian Z. Li & X.W. Hu) Kirchm. & O.K. Mill., and Lampteromyces luminescens M. Zang, which is closely related to O. guepiniformis and has uncertain generic placement [2]. These species are distributed across tropical to subtropical and temperate regions of China, and are predominantly associated with the decaying wood of Fagaceae and other deciduous trees [3]. The genus Omphalotus has a global distribution, with species reported from Europe, North America, Australia, and East Asia [4]. However, tropical and subtropical populations of Omphalotus remain understudied, with limited data on their taxonomic status and toxin profiles.

Mushroom poisoning is a global public health concern, with an estimated 10,000–50,000 cases annually worldwide, and misidentification of toxic species as edible ones is a common global risk factor [5]. Thus, the discovery of O. yunnanensis and its toxin characteristics provide critical data for global fungal diversity databases, inform international taxonomic revisions of Omphalotus, and offer a model for integrating morphology, phylogeny, and toxinology in identifying new toxic fungi—relevant to mycologists, toxicologists, and public health practitioners worldwide [6].

Omphalotus-caused mushroom poisoning has become a notable public health problem in China. According to surveillance data from 2021 to 2024, Omphalotus species (including O. guepiniformis, O. olearius, and the new species described below) were responsible for 2–7 poisoning incidents annually, involving 3–44 patients per year [3]. Geographically, these incidents were concentrated in Southwest China (Yunnan, Guizhou, and Sichuan) and Central-South China (Hunan, Guangxi, and Hainan). Clinical manifestations largely involve acute gastroenteritis, with symptoms including nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, and diarrhea occurring 1–6 h post-ingestion [3,7]. The primary cause of poisoning is the misidentification of Omphalotus species as edible mushrooms, e.g., Pleurotus spp. and Cantharellus spp., due to superficial morphological similarities, especially in rural areas [7].

The toxins of Omphalotus species are illudins, a kind of cytotoxic sesquiterpenoid [8,9,10,11,12]. Two major congeners, illudin S and illudin M, were first isolated from O. illudens (Schwein.) Bresinsky et Besl., and later discovered in O. olearius, O. guepiniformis, and O. nidiformis (Berk.) O.K. Mill [9,11,13]. Illudins exert their toxicity by alkylating DNA and inhibiting eukaryotic DNA replication, leading to intestinal epithelial cell damage and subsequent gastroenteritis [10,12]. Analytical studies using liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) and ultra-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) have confirmed illudin S as the primary toxic component in Asian Omphalotus species, while illudin M is either absent or present at undetectable levels in most Chinese isolates [10,11,12]. This toxin profile is consistent across the genus, making illudins a reliable chemotaxonomic marker for Omphalotus [2,10].

Recent poisoning surveillance has uncovered a series of unreported outbreaks caused by a morphologically distinct white Omphalotus species, which was initially recorded as Omphalotus sp. in epidemiological reports [6,7]. According to incident records from 2022 to 2025, this species has caused four confirmed poisoning events in China: (1) Jinping County, Yunnan (September 2022, 1 patient): nausea, violent vomiting, and abdominal cramps 2 h post-ingestion, symptom resolution within 48 h; (2) Hekou County, Yunnan (July 2023, 2 patients): watery diarrhea (6–8 episodes/day), abdominal colic, and mild dehydration 3 h post-ingestion, treated with rehydration therapy and recovered in 72 h; (3) Honghe County, Yunnan (October 2023, 6 patients): collective poisoning after consuming a white Omphalotus species misidentified as Pleurotus spp., presenting with nausea, vomiting, and crampy abdominal pain (latency 1.5–4 h), no hospitalizations required; (4) Wuzhishan City, Hainan (January 2025, 5 patients): severe abdominal spasms, vomiting, and diarrhea lasting 36 h. Illudin S alkylates DNA at N3 of adenine and N7 of guanine, inhibiting eukaryotic DNA replication and inducing apoptosis in intestinal epithelial cells. A multicenter study of Omphalotus poisoning in China reported that an illudin S intake of ≥0.05 mg/kg body weight (corresponding to 3 mg for a 60 kg adult) induces acute gastroenteritis. For the new species, ingestion of 10 g dried mushroom (a typical serving) results in an illudin S intake of 0.0698–0.861 mg, which exceeds the toxicity threshold—consistent with the clinical symptoms observed in the four poisoning incidents. No illudin M was detected, aligning with the toxin profile of Asian Omphalotus species [11,12].

The aims of this study were therefore (1) to determine the taxonomic status of these unique mushrooms through a critical examination of their morphological characteristics, along with a phylogenetic analysis based on internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequences and the nuclear large subunit (nrLSU) of ribosomal DNA, and (2) to conduct a comprehensive toxin profiling using ultra-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) to screen for a wide array of mushroom toxins, with a particular focus on illudins S and M. By integrating morphological, phylogenetic, and chemotaxonomic evidence, we describe a new species, Omphalotus yunnanensis, in detail.

2. Results

2.1. Molecular Phylogeny

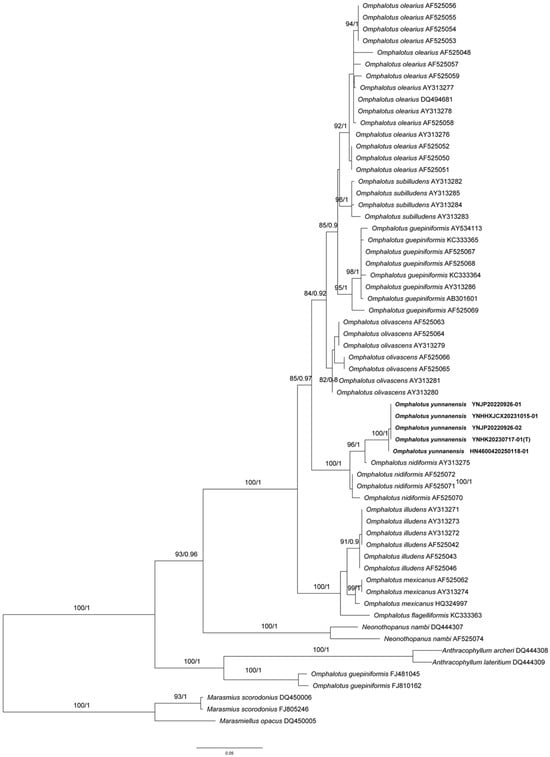

jModelTest (ModelTest-NG v0.1.7) suggested HKY + I + G as the best-fit nucleotide evolution models for the dataset. The average standard deviation of BI split frequencies was 0.002327 at the end of the run. BI analyses resulted in almost identical tree topologies to the ML analysis. The ML tree is provided in Figure 1, with the likelihood bootstrap values (≥50%, first) and Bayesian posterior probabilities (≥0.95, second) labeled along the branches. We conducted phylogenetic analyses of the ITS dataset using Maximum Likelihood (ML) and Bayesian Inference (BI) methods to establish the taxonomic position of the newly collected Omphalotus specimens. Consistent with the findings of Yang & Feng [2] and Kirchmair et al. [13], the genus Omphalotus formed a well-supported monophyletic clade (ML = 100%, BI = 1.00) in both phylogenetic trees [14].

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree of Omphalotus and related genera based on combined ITS sequence data. The tree was constructed using Maximum Likelihood analysis. Bootstrap values (ML, ≥80%) and Bayesian posterior probabilities (≥0.8) are shown at the nodes. Note: T means holotype.

Five specimens collected from Yunnan and Hainan Province formed a distinct monophyletic clade within Omphalotus, with maximum statistical support (ML = 100%, BI = 1.00, Figure 1). This clade was clearly separated from other recognized Omphalotus species.

2.2. Taxonomy and Morphology

Omphalotus yunnanensis Hai J. Li & Zhong-Feng Li, sp. nov. Figure 2 and Figure 3

MycoBank: 861469

Diagnosis: Omphalotus yunnanensis is characterized by its semicircular, flabelliform to infundibuliformis, cream to white basidiomata with a hygrophanous pileal surface, non-bioluminescent lamellae, large, broadly ellipsoid to subglobose basidiospores (8–12.5 × 7–10 μm), fusoid to ventricose cheilocystidia which sometimes with apical outgrowths, cream to white pileipellis composed with thick-walled, subsoil to solid hyphae, clavate, fusoid to ventricose caulocystidia which sometimes with apical outgrowths, and discovered from tropical to subtropical Southwestern and Southern areas of China.

Holotypus: CHINA, Yunnan Province, Honghe Hani and Yi Autonomous Prefecture, Hekou Yao Autonomous County, Lianhuatan Town, Zhonglinggang Village, Yaomaji Group 1, on fallen angiosperm trunk, 17 July 2023, YNHK20230717-01 (BJFC054640, ITS sequence accession number: PX596399, LSU sequence accession number: PX588451).

Etymology: The specific epithet “yunnanensis” refers to Yunnan Province, China, the type locality of the new species.

Macrostructures: Pileus 30–80 mm latus, semicircular, flabelliform to infundibuliformis, convex when young, becoming applanate with a depressed center at maturity; cream to white, hygrophanous when fresh, glabrous; margin entire, slightly incurved when fresh. Lamellae decurrent, crowded, cream to white, not bioluminescent. Stipe 30–70 × 5–15 mm, lateral, eccentric to central, subcylindric, slightly attenuate ·towards the base; surface concolorous with the pileus or paler, upper part glabrous and velutinate near the base. Context solid, cream to white, tough. Odor indistinct; taste not tested.

Figure 2.

Basidiomata of Omphalotus yunnanensis. (a): YNHK20230717-01 (holotype). (b,c): YNJP20220926-01.

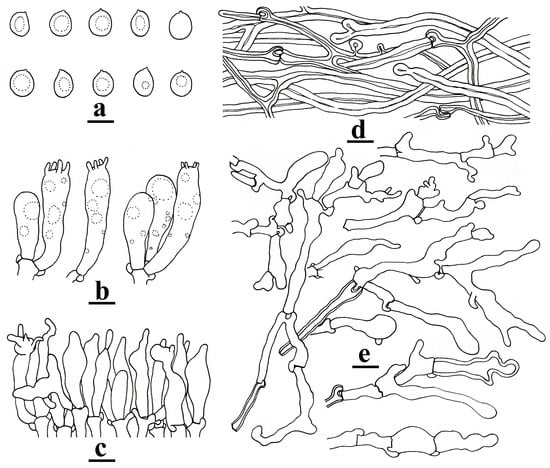

Microstructure: Basidiospores [60/5/3] (7.2–)8–12.5(–13) × (6.7–)7–10(–11.6) μm, averaging 10.37 × 8.65 μm, Q = (1.05–)1.07–1.36(–1.44), Qm = 1.20 ± 0.10, mostly broadly ellipsoid to subglobose, rarely ellipsoid, nearly colorless to hyaline, mostly guttulate, smooth, thin-walled to slightly thick-walled (≤0.5 μm thick), non-amyloid, non-dextrinoid (Figure 3a). Basidia 25–35 × 7–9 μm, clavate, hyaline, 4-spored, with clamp connections at the base (Figure 3b). Cheilocystidia abundant, 20–35 × 6–8 μm, flexuous, mostly fusoid to ventricose, sometimes with rostrate to mucronate apical outgrowths, rarely with secondary septum, colorless and hyaline, thin-walled (Figure 3c). Pleurocystidia absent. Lamellar trama composed of ± regularly arranged thin- to slightly thick-walled (≤0.5 μm thick) filamentous hyphae, 4–10 μm wide. Pileipellis a cutis composed of repent hyphae, 3–8 μm wide, cream to white, thick-walled, subsoil to solid (Figure 3d). Stipitipellis consisting of vertically arranged, branching and sometimes anastomosing hyphae, yellowish to yellowish, thick-walled, 5–9 μm wide; Caulocystidia clavate, fusoid to ventricose, sometimes with rostrate to mucronate apical outgrowths, occasionally with secondary septum, nearly colorless and hyaline, mostly thin-walled, rarely thick-walled, 25–40 × 5–7 μm (Figure 3e).

Additional specimen examined: CHINA, Yunnan Province, Honghe Prefecture, Jinping County, Jinshuihe Township, Pujiao Village, 24 September 2022, YNJP20220926-01 (ITS sequence accession number: PX596400) and YNJP20220926-02 (ITS sequence accession number: PX596398); Jiache Town, Hemo Village, 14 October 2023, YNHHXJCX20231015-01 (ITS sequence accession number: PX588448, LSU sequence accession number: PX588454); Hekou County, Lianhuatan Township, Zhonglinggang Village, Yaomaji Group 1, 17 July 2023, YNHK20230717-01 (ITS sequence accession number: PX596399, LSU sequence accession number: PX588451); Hainan Province, Wuzhishan, Shuiman Township, Xincun Group 1, 18 January 2025, HN4600420250118-01 (ITS sequence accession number: PX588449, LSU sequence accession number: PX588453).

Figure 3.

Microstructures of Omphalotus yunnanensis (YNHK20230717-01, holotype). (a). Basidiospores; (b). basidia; (c). cheilocystidia; (d). pileipellis hyphae; (e). caulocystidia. Bars = 10 μm. Figure drawn by H.-J. Li.

2.3. Toxin Detection Results

Linearity: All target toxins showed good linearity in the range of 0.5–200 μg/L, with correlation coefficients (R2) > 0.995 (e.g., R2 = 0.998 for illudin S) [10,15]. Limits of Detection (LODs) and Quantification (LOQs): LODs ranged from 2.0 to 500.0 mg/kg, and LOQs ranged from 5.0 to 500 mg/kg (LOD = 3.0 mg/kg, LOQ = 5 mg/kg for illudin S). Recovery and Precision: The mean recoveries at three spiking levels (10, 20, 100 μg/kg) were 78.6–109.7%, with relative standard deviations (RSDs) ≤ 9.0% (n = 6), thus meeting the mycotoxin detection requirements [16,17]. Only illudin S was detected in all three O. yunnanensis specimens, with its content ranging from 6.98 to 86.1 mg/kg (dry weight, Table 1); no other target toxins were found.

Table 1.

Omphalotus yunnanensis illudin S content and collection information.

3. Discussion

This study integrates morphological observation, phylogenetic analysis, and toxin detection to address two core objectives: delimiting the taxonomic status of a novel Omphalotus species from China and characterizing its toxin profile. The findings enrich our understanding of the fungal diversity of Omphalotus, providing critical data for assessing the public health risks posed by poisonous mushrooms.

ITS sequence-based phylogenetic reconstruction confirmed that the five specimens from Yunnan and Hainan formed a strongly supported monophyletic clade (ML = 100%, BI = 1.00), and one that is clearly distinct from all known Omphalotus species. The new species grouped with the Australasian species O. nidiformis, but can be easily distinguished by its smaller (30–80 mm vs. 50–250 mm in diameter), white to cream pileus, non-bioluminescent lamellae, larger basidiospores (8–12.5 × 7–10 μm vs. 6–8 × 4–5 μm) and its growing on Fagaceae species vs. on Eucalyptus spp. and Acacia spp., as is seen for O. nidiformis [16,17,18].

Morphologically speaking, Omphalotus guepiniformis can be distinguished from the new species by its larger, pleurotoid to fan-shaped basidiomata, red-brown, blue to violet pileus surface, bioluminescent lamellae, larger, nearly colorless and hyaline or yellowish to brownish, thin- to thick-walled basidiospores (10–15.5 × 9.5–14.5 μm), with a smooth surface when thin-walled and finely rough to verrucous when thick-walled [2,11,19].

Omphalotus mangensis, originally described in Hunan, China, also produces white basidiomata, which can be easily differentiated from O. yunnanensis by its pleurotoid to fan-shaped basidiomata, bioluminescent lamellae, larger, globose to subglobose, thin- to thick-walled basidiospores (11–16 × 10–15 μm) [2].

This new species can be distinguished from the widespread O. olearius (distributed in Europe and introduced into East Asia [5]) by its white to cream pileus surface, non-bioluminescent lamellae and larger basidiospores (8–12.5 × 7–10 μm vs. 7–10 × 5–7 μm) [9,11,20].

UPLC-MS/MS detection showed that O. yunnanensis produces illudin S, without illudin M, alongside the well-documented trait that “illudins are characteristic sesquiterpenoid toxins of the Omphalotus genus” [9,10]. This finding reinforces chemotaxonomic consistency within Omphalotus: previous studies have confirmed illudins in O. olearius (Europe), O. guepiniformis (East Asia), and O. nidiformis (Australia) [8,10,11], and the presence of these toxins in O. yunnanensis further validates these compounds as a synapomorphy (shared derived trait) of the genus [21].

Interspecific comparison of illudin S concentrations reveals that O. yunnanensis (6.98–86.1 mg/kg dry weight) falls within the toxic range of other Omphalotus species. For O. guepiniformis, illudin S concentrations were 12.3–78.5 mg/kg dry weight [22]; for O. olearius, concentrations ranged from 8.7–92.4 mg/kg dry weight [23]; and for O. nidiformis, illudin S was 5.6–68.9 mg/kg dry weight [10]. The overlapping concentration ranges explain the consistent acute gastroenteritis symptoms induced by these species, confirming that O. yunnanensis shares the same toxicological profile as its congeners [24].

4. Conclusions

Based on systematic morphological, phylogenetic, and chemotaxonomic investigations, we described a new poisonous mushroom species, Omphalotus yunnanensis.

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Sample Collection and Morphological Observation

All specimens in this study were obtained from epidemiological surveys of mushroom poisoning incidents involving fungi collected from tropical to subtropical evergreen broad-leaved forests. Specimen collection and identification followed the standard methods for taxonomic research [17,25,26,27].

In situ field photographs of the fruiting bodies were taken to record their macroscopic morphological characteristics, including pileus color, lamella arrangement, stipe features, and bioluminescence. The fresh specimens were dried in a 45 °C blast drying oven and then preserved in the Herbarium of the National Institute of Occupational Health and Poison Control, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention.The holotype was also preserved in the herbarium of Beijing Forestry University (BJFC).

Microscopic structural observation followed the established technical protocols [2,26]. After rehydrating the dried specimens, free-hand sections were prepared. Tissues from the pileipellis, lamellae, and stipe context were mounted in 5% potassium hydroxide (KOH) solution, and all microscopic characteristics were observed and measured using a Nikon E 80I microscope (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). In the basidiospore descriptions, the abbreviation [n/m/p] means n basidiospores measured from m basidiomata of p collections; Q is used to mean “length/width ratio” of a spore in side view, while Qm means average Q of all basidiospores ± sample standard deviation.

5.2. DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification and Phylogenetic Analysis

The Phire® Plant Direct PCR Kit (Finnzymes Oy, Espoo, Finland) was used to obtain PCR products from dried specimens, according to the manufacturer’s instructions with some modifications [28]. ITS5/ITS4 was used to amplify the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions [29], while LR0R/LR5 was used to amplify the nuclear large subunit rDNA (LSU) regions [30]. For the PCR procedures, we followed the method presented by Tang et al. [28]. All newly generated sequences in this study were deposited in GenBank (PX588448-PX588449, PX596398-PX596400, PX588451, PX588453-PX588454).

Reference sequences of Omphalotaceae and related taxa were downloaded from GenBank. Maximum likelihood (ML) analyses and Bayesian inference (BI) were carried out using RAxML v.8.2.10 [31] and MrBayes 3.2.6 [15]. In ML analysis, statistical support values were obtained using rapid bootstrapping with 1000 replicates, with default settings used for other parameters. For BI, the best-fit substitution model was estimated with jModeltest v.2.17. Four Markov chains were run 4,000,000 times for the dataset until the split deviation frequency value was lower than 0.01. Trees were sampled every 100th generation. The first quarter of these, representing the analysis burn-in phase, were discarded, and the remaining trees were used to calculate posterior probabilities (BPP) in the majority rule consensus tree [27]. Marasmius scorodonius and Marasmiellus opacus were selected as outgroups [1].

5.3. Toxin Analysis

5.3.1. Sample Preparation

Sample preparation was performed according to established protocols with minor modifications [10,12]. Dried basidiomata were finely homogenized using a laboratory mill. Approximately 10 mg of the homogenized sample was accurately weighed into a 15 mL polypropylene centrifuge tube. Extraction was carried out with 2 mL of methanol–water (70:30, v/v) by vortexing for 1 min followed by ultrasonic extraction for 60 min at room temperature. The extract was then centrifuged at 15,000× g for 5 min at 4 °C. For purification, 1 mL of the supernatant was processed using a QuEChERS-PP purification column containing multi-walled carbon nanotubes during the stationary phase [25]. Finally, 10 μL of the purified extract was diluted with methanol–water (5:95, v/v) to a final volume of 1 mL. The solution was centrifuged at 21,000× g for 2 min prior to UPLC-MS/MS analysis.

5.3.2. Instrumental Analysis

Ultra-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) was used to detect toxins in dried specimens of O. yunnanensis. Target toxins included: (1) Omphalotus-specific toxins (illudin S and M); and (2) common mushroom toxins with gastroenteritis-causing potential (amatoxins: α-amanitin, β-amanitin; muscimol; ibotenic acid; orellanine), based on the clinical symptoms of poisoning incidents. Non-targeted screening was also performed to detect unknown toxins using full-scan MS mode (m/z 50–500).

The analysis was performed using a Waters ACQUITY I-Class UPLC system (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA) coupled with a Waters Xevo TQ-S triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). Chromatographic separation was achieved on an ACQUITY UPLC HSS T3 column (100 mm × 2.1 mm, 1.8 μm; Waters) maintained at 40 °C. The mobile phase consisted of (A) 10 mmol/L ammonium acetate in water and (B) acetonitrile, delivered at a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min using the following gradient program: 0–1 min, 10% B; 1–8 min, 10–95% B; 8–9 min, 95% B; 9–9.1 min, 95–10% B; 9.1–12 min, 10% B for column re-equilibration. The injection volume was 2 μL.

Mass spectrometric detection was performed in positive electrospray ionization (ESI+) mode with multiple reaction monitoring (MRM). The optimized MS parameters were as follows: capillary voltage, 2.0 kV; source temperature, 150 °C; desolvation temperature, 500 °C; desolvation gas flow, 900 L/h; and cone gas flow, 150 L/h. The MRM parameters for the target toxins, including illudins S and M, are summarized in Table 2 [30].

Table 2.

Optimized MRM parameters for mushroom toxin detection.

5.3.3. Method Validation and Quantification

The method was rigorously validated according to recognized guidelines for analytical method validation [11,25]. The analytical standards of illudin S (purity ≥ 98%, CAS: 28276-28-0) and illudin M (purity ≥ 97%, CAS: 28276-27-9) used for calibration and validation were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Sigma-Aldrich Corporation, St. Louis, MO, USA) with product numbers 16458 and 16459, respectively. Matrix-matched calibration curves were established using blank Lentinula edodes samples spiked with standard solutions of the two toxins at seven concentration levels (0.5–200 μg/L for most analytes). The authenticity and purity of the standards were verified by comparing their retention times, mass spectra, and fragmentation patterns with those reported in previous studies [9,11,14] and the manufacturer’s certification. Linear regression analysis demonstrated excellent linearity with correlation coefficients (R2) greater than 0.995 for all target toxins. The limits of detection (LOD) and quantification (LOQ) were determined as signal-to-noise ratios of 3 and 10, respectively. Recovery experiments were performed by spiking blank samples at three concentration levels (10, 20, and 100 mg/kg) with six replicates at each level. The mean recoveries ranged from 85.2% to 106.3%, with relative standard deviations (RSDs) less than 12.5%. Quantification was performed using the external standard method with matrix-matched calibration curves to compensate for matrix effects.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Conceptualization, H.-J.L.; Data curation, Z.-F.L., J.Z. and X.-D.M.; Formal analysis, Z.-F.L., H.-S.Z. and L.C.; Funding acquisition, H.-J.L.; Investigation, Z.-F.L., D.-N.L., Y.-Z.Z., M.-X.Y. and Z.-Y.L.; Methodology, J.Z.; Project administration, J.-J.Z. and M.-H.R.; Resources, J.-J.Z.; Software, H.-S.Z. and Z.-F.L.; Writing—original draft, Z.-F.L.; Writing—review and editing, H.-J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Independent Research Fund of State Key Laboratory of Trauma and Chemical Poisoning (2025SKLCDC-02), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32570009).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks are due to Qing Li (Hekou CDC), Tao Zhong (Jinping CDC), Yu-Ting Pan (Honghe CDC) and Lian-Yu Wang (Wuzhishan CDC) for help in field collection. We express our gratitude to Zhu L. Yang (KIB, China) for species identification.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kirchmair, M.; Pöder, R.; Huber, C.G.; Miller, O.K. Chemotaxonomical and morphological observations in the genus Omphalotus (Omphalotaceae). Persoonia 2002, 14, 583–600. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.L.; Feng, B. The genus Omphalotus (Omphalotaceae) in China. Mycosystema 2013, 32, 545–556. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.J.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Zhang, H.S.; Zhou, J.; Zhong, F.L.; Yin, Y.; He, Q.; Jiang, S.F.; Zhang, Y.T.; Yuan, Y.; et al. Mushroom Poisoning Outbreaks—China, 2024. China CDC Wkly. 2025, 7, 645–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaura, Y. Recent trends of mushroom poisoning in Japan. J. Toxicol. Jpn. 2013, 26, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz, J.H. Evolving global epidemiology, syndromic classification, general management, and prevention of unknown mushroom poisoning. Crit. Care Med. 2005, 33, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenburg, W.; Ward, K. Mushroom poisoning epidemiology in the United States. Mycologia 2018, 110, 637–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.H.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, Z.G. Investigation and analysis of 102 mushroom poisoning cases in Southern China from 1994 to 2012. Fungal Divers. 2014, 64, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anchel, M.; Hervey, A.; Robbins, W.J. Production of Illudin M and of a fourth crystalline compound by Clitocybe illudens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1952, 38, 927–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMorris, T.C.; Anchel, M. Fungal metabolites. The structures of the novel sesquiterpenoids illudin-S and -M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965, 87, 1594–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchmair, M.; Pöder, R.; Huber, C.G. Identification of illudins in Omphalotus nidiformis and Omphalotus olivascens var. indigo by column liquid chromatography-atmospheric pressure chemical ionization tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 1999, 832, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, S.; Aboshi, T.; Shiono, Y.; Kimura, K.I.; Murata, T.; Arai, D.; Iizuka, Y.; Murayama, T. Constituents of the Fruiting Body of Poisonous Mushroom Omphalotus japonicus. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2020, 68, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, M.L.; Zhang, Y.L.; Barrow, K.D. Characterization of new illudanes, illudins F, G, and H from the basidiomycete omphalotus nidiformis. J. Nat. Prod. 1999, 62, 1542–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchmair, M.; Morandell, S.; Stolz, D.; Pöder, R.; Sturmbauer, C. Phylogeny of the genus Omphalotus based on nuclear ribosomal DNA-sequences. Mycologia 2004, 96, 1253–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonmori, K.; Hasegawa, K.; Fujita, H.; Kamijo, Y.; Nozawa, H.; Yamagishi, I.; Minakata, K.; Watanabe, K.; Suzuki, O. Analysis of ibotenic acid and muscimol in Amanita mushrooms by hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Forensic Toxicol. 2012, 30, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronquist, F.; Teslenko, M.; Van der Mark, P.; Ayres, D.L.; Darling, A.; Höhna, S.; Larget, B.; Liu, L.; Suchard, M.A.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012, 61, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Z.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, K.P.; Liang, J.Q.; Zhong, J.J.; Li, Z.F.; Li, H.J.; Xu, F. Toxin Profiling of Amanita citrina and A. sinocitrina: First Report of Buiotenine Detection. Toxins 2025, 17, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Sun, C. Simultaneous Determination of Multi-Class Mushroom Toxins in Mushroom and Biological Liquid Samples Using LC-MS/MS. Separations 2024, 11, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, O.K.; Kirchmair, M. Omphalotus nidiformis: A Australasian species with bioluminescent basidiomata. Mycologia 1999, 91, 521–528. [Google Scholar]

- Kuyper, T.W. Omphalotus Fayod. In Flora Agaricina Neerlandica; Bas, C., Kuyper, T.W., Noordeloos, M.E., Vellinga, E.C., Eds.; A.A. Balkema: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 1995; Volume 3, pp. 88–99. [Google Scholar]

- Horak, E. Synopsis generum agaricalium (die Gattungstypen der Agaricales). Beitr. Kryptogamenfl. Schweiz 1968, 13, 1–741. [Google Scholar]

- Corner, E.J.H. The agaric genera Lentinus, Panus and Pleurotus with particular reference to Malaysian species. Beih. Nova Hedwigia 1981, 69, 1–169. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.J. Study on Genome and Toxin Distribution of Omphalotus guepiniformis. Ph.D. Thesis, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Schobert, R.; Biersack, B.; Knauer, S.; Ocker, M. Conjugates of the fungal cytotoxin illudin M with improved tumour specificity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008, 16, 8592–8597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelot, D.; Melendez-Howell, L.M. Toxic mushrooms in China: A review of species, toxicity, and clinical management. Mycologia 2020, 112, 345–360. [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrer, B.A.; Lepp, H. Fungi of Australia: Agarics and Boletes; CSIRO Publishing: Collingwood, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.X.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Liang, J.Q.; Li, Y.; Zhao, H.; Shang, Z.R.; Si, J.; Li, H.J. Neocotylidia gen. nov. (Hymenochaetales, Basidiomycota) Segregated from Cotylidia Based on Morphological, Phylogenetic, and Ecological Evidence. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kout, J.; Zibarova, L. Revision of the genus Cotylidia (Basidiomycota, Hymenochaetales) in the Czech Republic. Czech Mycol. 2013, 65, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.X.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Liang, J.Q.; Jiang, S.F.; Si, J.; Li, H.J. Pyrofomes lagerstroemiae (Polyporaceae, Basidiomycota), a new species from Hubei Province, Central China. Phytotaxa 2023, 583, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Vilgalys, R.; Hester, M. Rapid genetic identification and mapping of enzymatically amplified ribosomal DNA from several Cryptococcus species. J. Bacteriol. 1990, 172, 4238–4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamatakis, A. RAxML Version 8: A tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1312–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.