Abstract

Aflatoxin B1 (AFB1), a major metabolite of aflatoxin, is a highly toxic carcinogen. It frequently contaminates feed due to improper storage of feed ingredients such as corn and peanut meal, with the contamination risk further escalating alongside the increasing incorporation of plant-based proteins in feed formulations. Upon entering an organism, AFB1 is metabolized into highly reactive derivatives, which trigger an oxidative stress-inflammation vicious cycle by binding to biological macromolecules, damaging cellular structures, activating apoptotic and inflammatory pathways, and inhibiting antioxidant systems. This cascade leads to stunted growth, impaired immunity, and multisystem dysfunction in animals. Long-term accumulation can also compromise reproductive function, induce carcinogenesis, and pose risks to human health through residues in the food chain. Tannins are natural polyphenolic compounds widely distributed in plants which exhibit significant antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities and can effectively mitigate the toxicity of AFB1. They can repair intestinal damage by increasing the activity of antioxidant enzymes and up-regulating the gene expression of intestinal tight junction proteins, regulate the balance of intestinal flora, and improve intestinal structure. Meanwhile, tannins can activate antioxidant signaling pathways, up-regulate the gene expression of antioxidant enzymes to enhance antioxidant capacity, exert anti-inflammatory effects by regulating inflammation-related signaling pathways, further reduce DNA damage, and decrease cell apoptosis and pyroptosis through such means as down-regulating the expression of pro-apoptotic genes. This review summarizes the main harm of AFB1 to animals and the mitigating mechanisms of tannins, aiming to provide references for the resource development of tannins and healthy animal farming.

Key Contribution:

In this paper, the harm of AFB1 to animals and the ways of tannin alleviating toxicity were reviewed, which provided reference for tannin resource development and green and healthy animal breeding.

1. Introduction

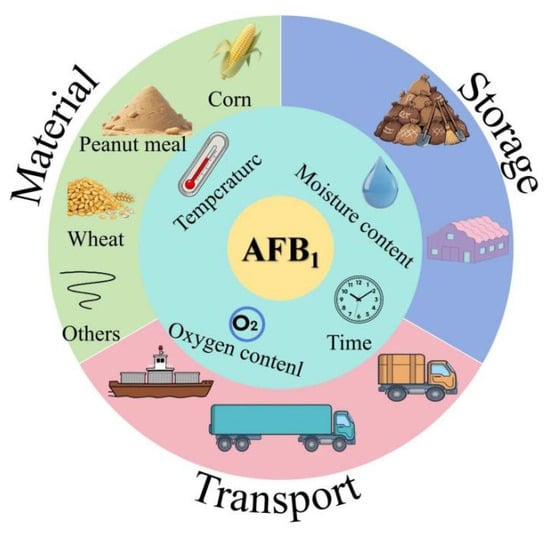

Aflatoxin is a secondary metabolite produced by Aspergillus flavus, which can grow and reproduce on grains under hygrothermal environments, thus polluting agricultural products [1,2], posing a risk to food and feed safety. So far, approximately 20 types of aflatoxins have been identified, among which AFB1 is considered to be the most toxic [3]. It is a class I carcinogen identified by the World Health Organization and the annual losses caused by AFB1 amount to billions of yuan [3,4]. The pollution of AFB1 in feed mainly derived from corn, peanut meal, soybean, rapeseed meal, etc. and these feedstuffs are highly susceptible to mold contamination under improper storage conditions (Figure 1). Due to the growing scarcity and high cost of fish meal, there is an increasing trend towards using plant-based proteins as feed ingredients. However, this shift also increases the risk of feed contamination by AFB1. According to random sampling, the contamination of feed ingredients and compound feed by AFB1 in China is a growing concern [5,6,7]. AFB1 can cause genetic mutations and chromosomal abnormalities in human and animal cells [8]. In addition, AFB1 increases the risk of human and animal visceral injury and suppresses immune function [9]. Currently, the main methods to alleviate the toxicity of AFB1 include adding functional substances and nutritional regulation. For example, smectite powder can be used as an adsorbent for mycotoxins to alleviate the impact of AFB1 on broilers [10], yeast cell wall can alleviate the damage of AFB1 to intestinal epithelial cells of broilers [11], vitamin C and turmeric powder can reduce oxidative damage by reducing oxidative stress caused by AFB1 [12,13], and probiotics alleviate the toxicity of AFB1 by regulating the intestinal flora [14,15]. In addition, regulating glutathione synthesis can reduce the oxidative damage caused by AFB1 [16,17]. Selenium [18], boron [19] and other trace elements can enhance the antioxidant and immune capacity of the body to improve the tolerance of animals to AFB1.

Figure 1.

The sources and generation pathways of AFB1.

Tannins are natural polyphenolic compounds widely existing in the plant kingdom. Generally, common sources of tannins in animal feed include grain, forage legumes or plant-derived feedstuffs. Tannins are mainly classified into condensed tannin (also known as procyanidine), hydrolyzed tannin and phlorotannins [20,21]. Tannins have traditionally been known as “anti-nutritional factor” for monogastric animals with negative effects on feed intake and nutrient digestibility by binding to dietary proteins and digestive enzymes. Our previous studies documented that a high dose (2 g/kg) of condensed tannin and hydrolyzed tannin reduced growth and induced intestinal injury in the Chinese sea bass (Lateolabrax maculatus) [22,23]. However, recent research showed that a low dose of tannins improved intestinal microbial ecosystems, enhanced gut health and hence increased the productive performance of animals [20,24,25,26], owing to their beneficial biological effects.

Tannins exhibit notable biological activities, including strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties both in vitro and in vivo studies [27]. Recent studies have shown that dietary supplementation with 1 g/kg of condensed tannin can reduce the deposition of AFB1 in sea bass (Lateolabrax maculatus), up-regulate the gene expression of tight junction protein gene ZO-1 (zonula occludens-1), Claudin-3 and occludin, and repair the damage of intestinal barrier function induced by AFB1. Additionally, it increases the relative abundance of beneficial bacteria such as Aeromonas and Klebsiella in the intestine, inhibits the proliferation of harmful bacteria, and improves overall intestinal health [28,29]. Condensed tannin can also inhibit the expression of down-regulated apoptosis genes Bax and caspase-3, tumor suppressor gene p53, and alleviate hepatocyte mitochondrial apoptosis [30]. Hydrolyzed tannin can down-regulate the nuclear NF-κB (nuclear factor kappa B) signaling pathway in sheep, thereby alleviating inflammation [31]. Thus, tannins may alleviate the toxicity of AFB1 by alleviating intestinal injury, regulating intestinal flora, increasing immune ability and inhibiting apoptosis. In this review, the harmful effects of AFB1 to animals and the use of tannins as a mitigation strategy are summarized. The findings provide a reference for the development of tannin-based resources and the promotion of animal health in breeding programmes.

2. Toxicity of AFB1 to Animals

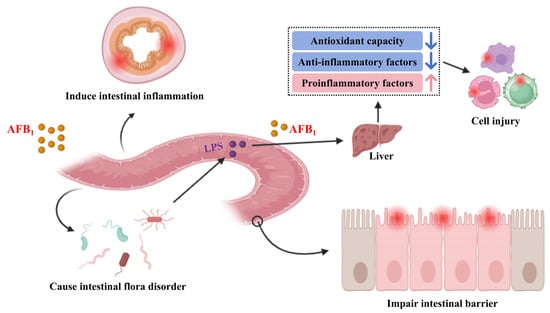

Upon entering the animal organs, AFB1 first impairs intestinal health, induces intestinal microbiota dysbiosis, and triggers intestinal inflammation. This sequence of events leads to intestinal cell damage and increased intestinal permeability, thereby enabling AFB1 and LPS (lipopolysaccharide) to translocate to the liver, where they induce inflammatory responses. Ultimately, such processes result in damage to other cells throughout the animal body (Figure 2). The negative effects of AFB1 to animals are shown in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Potential toxicity of AFB1 to animals.

Table 1.

Negative effects of AFB1 on animals.

2.1. Growth Inhibition

Growth performance is a key and aggregative evaluation indicator for the growth and health of animals. In economically important species, growth performance is directly linked to the profitability of production systems. In aquatic animals, it was reported that the addition of 2230 μg/kg AFB1 in their feed did not affect the growth performance of hybrid grouper (Epinephelus fuscoguttatus ♀ × Epinephelus lanceolatus ♂) [43]. However, AFB1 induces oxidative stress and inflammation, ultimately hindering the growth of the affected individuals. In another study, dietary inclusion of 1.0 mg/kg AFB1 did not affect the survival rate of Lateolabrax maculatus, but reduced feed intake, weight gain rate and specific growth rate, resulting in a decline in growth performance [28]. In livestock and poultry, the addition of 45 μg/kg AFB1 in Chinese yellow chicken feed reduced the weight gain rate and feed utilization rate of broilers aged 1 to 63 days [46], which was attributed to the reduction of energy and protein metabolism efficiency by AFB1, resulting in the decline of growth performance [47,48]. The addition of 2550 μg/kg AFB1 in feed reduces the digestibility of sheep, affecting the digestion and absorption of nutrients, thus inhibiting growth [49].

The reasons for AFB1 inhibiting animal growth may be attributed to several mechanisms. First, AFB1 reduces digestive function. For instance, Pu et al. [35] reported that when the concentration of AFB1 in feed exceeded 280 μg/kg, nutrient digestibility in the digestive tract of pigs decreased significantly. In addition, AFB1 reduces the activities of key digestive enzymes such as ether extract lipase, trypsin and collagenase, thereby impairing nutrient digestion and absorption in the intestine [41,50]. Second, AFB1 inhibits protein synthesis, a critical process in growth. In grouper, AFB1 induces protein metabolism disorder by inhibiting the expression of binding protein 1, fatty acid synthase and mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin), ultimately leading to suppressed growth performance [28,49]. Third, AFB1 causes tissue and organ damage. It was documented that AFB1 exposure led to induced intestinal and gill tissue damage in goldfish (Carassius auratus), increased the metabolic demands for tissue repair and detoxification [51], thus resulting in reduced growth performance due to lack of energy necessary for growth.

2.2. Liver Injury

Liver is the central organ for detoxification in animals. However, it is particularly vulnerable to damage from AFB1 exposure, which can induce liver inflammation, apoptosis and oxidation resistance, thus compromising liver health. It is reported that AFB1 can induce congestion and fat deposition in the liver of laying hens, and the proportion of inflammatory cells, apoptotic cells and lipid droplets in the liver are significantly increased [52]. In rats, dietary AFB1 can lead to an increase of glutathione content, glutathione peroxidase activity and superoxide dismutase activity in liver, increase the expression of proinflammatory factors, and lead to inflammatory cell infiltration and oxidative stress [52]. After infection with AFB1, the gene expression levels of apoptotic factors caspase-1 (cysteine protease caspase-1), IL-1β (inflammatory cytokines interleukin-1β) and IL-18 (interleukin-18) in the liver of mice were significantly increased, which induced liver inflammation [38]. AFB1 can cause necrosis and vacuolation of hepatocytes, vacuolation of mitochondria and swelling of endoplasmic reticulum in snakehead (Channa Argus), thus damaging the liver health [44]. Furthermore, AFB1 can reduce the activities of antioxidant enzymes such as CAT (catalase) and SOD (superoxide dismutase) in the liver of Lateolabrax maculatus, increase the content of MDA (malondialdehyde), and cause liver lipid peroxidation damage [28].

The main causes of AFB1-induced liver injury may include aggravation of oxidative stress and the induction of hepatocyte death. First, oxidative stress in the liver is a key driver for various liver diseases [53]. The liver is the main site for the epoxidation of AFB1 to AFB1-8,9-epoxide, which induces gene mutation by binding with DNA, leading to liver inflammation and cancer [54]. Liu et al. [55] reported that AFB1 can increase the content of ROS (reactive oxygen species), promote the accumulation of bile acids in the liver, aggravate oxidative stress and inflammation, and lead to liver injury by inhibiting the expression of FXR (Farnesoid X Receptor)/fibroblast growth factor 15 signaling pathway in the intestine. Second, AFB1 induces hepatocyte cell death. Pyrolysis of liver cells is considered an important factor in causing liver inflammation, which can activate acute and chronic hepatitis, fibrosis and non-alcoholic hepatitis [56,57]. AFB1 promotes the activity of hepatocyte cyclooxygenase, activates inflammatory body NLRP3 (nod-like receptor thermoprotein domain related protein 3), induces and activates apoptosis factor caspase-1, promotes the gene expression of proinflammatory cytokines IL-18 and IL-1β, and leads to cell membrane damage and cell death [58]. In addition, hepatocyte pyrosis may be induced by AFB1 through intestinal microbiota. The microbiota affected by AFB1 increases intestinal permeability by destroying the mucosal layer and tight junction proteins, leading to the translocation of LPS to the liver. Finally, the focal death signal of hepatocytes is activated [38].

2.3. Intestinal Injury

The intestine is the primary site for the digestion and absorption of nutrients. However, AFB1 exposure can severely compromise intestinal health by damaging the morphology of intestinal villi, reducing the number of epithelial cells and goblet cells. Peng et al. [29] reported that dietary supplementation of AFB1 led to irregular arrangement of intestinal villi of Litopenaeus vannamei, which was manifested by deformation of villi and reduction of villi height. The height, width and area of intestinal villi in broilers infected with AFB1 decreased, and the depth of crypt increased significantly [33]. Similarly in broilers, AFB1 induced the shedding of epithelial cells at the top of intestinal villi, partial loss of the junction complex and terminal network, and a significant reduction in the number of mitochondria and goblet cells [34]. In mice, AFB1 caused damage to both Goblet cells and epithelial cells in the intestinal tract fed AFB1, which was associated with inflammation [39]. In rats, AFB1 aggravates oxidative stress, causes intestinal inflammation and duodenal injury [59]. In addition, AFB1 can also change the composition of intestinal microbiota, induce liver injury and endanger intestinal health through the intestinal microbiota bile acid FXR axis [55].

The mechanism by which AFB1 induces intestinal injury may involve several interrelated pathways. First, AFB1 triggers intestinal oxidative stress and inflammation. AFB1 increases the contents of ROS and MDA in the intestine of rabbits, inhibiting the activity of antioxidant enzymes, and inducing intestinal oxidative stress [49]. In mice, AFB1 causes the decrease of bile salt hydrolase activity, causing the accumulation of bile acids in the intestine, thereby inducing intestinal oxidative stress and inflammation [55]. Second, AFB1 impairs intestinal barrier function. In AFB1-exposed mice, alterations to the structure of intestinal flora, along with damage to tight junction proteins and intestinal mucosal layers increases intestinal permeability and causes intestinal injury [38]. AFB1 has also been shown to damage intestinal cell membrane, increase intestinal permeability, and induce intestinal barrier damage through clathrin-mediated endocytosis and tight junction protein transport to the cytoplasm [60]. In broilers, AFB1 causes the disappearance of the junction complex in the small intestine, reduction of the number of small intestinal goblet cells, and reduction of Toll-like receptor gene expression, resulting in the impairment of small intestinal barrier function [34]. Third, AFB1 can induce apoptosis of intestinal cells. It has been shown that AFB1 induces apoptosis of intestinal cells, leading to structural damage of intestinal mucosa [4]. This effect is mediated by the increased intestinal ROS content, which contributes to oxidative stress and cellular injury [49]. Zhang et al. [40] further reported that AFB1 can induce intestinal mucosal structural damage by down-regulating the expression of intestinal mucosa-associated connexin genes and promoting cell apoptosis.

2.4. Damage Reproductive Performance

For male animals, AFB1 exposure has been shown to reduce the size, volume and sperm motility in bird [61]. AFB1 damages the mitochondrial structure of testicular germ cells and stromal cells, tissue lesions, abnormal sperm development, and is accompanied by reduced mitochondrial complex enzyme activity and oxidative stress [62]. In addition, AFB1 increases the proportion of abnormal sperm cell morphology, reduces testicular weight, and lowers testosterone concentration [63]. The serum testosterone, prolactin and luteinizing hormone levels of male birds were significantly decreased due to AFB1 induction, and testicular volume was reduced, even showing necrosis of testicular parenchyma [61]. For female animals, AFB1 negatively affects ovarian function and oocyte development. Exposure to AFB1 reduced both the volume and number of oocytes [32,64], as well as the number of resting follicles and developing follicles [65]. Additionally, AFB1 decreased the elimination rate of the first polar body of oocytes and interfered with the oocyte maturation cycle [66,67].

The adverse effects of AFB1 on reproductive performance may be primarily attributed to its ability to induce cell apoptosis. AFB1 causes DNA strand breaks, DNA cross-linking or DNA and protein cross-linking, which increases the sperm deformity rate [68]. AFB1 also enhances autophagy by aggravating testicular oxidative stress, causing down-regulation of the autophagy signaling pathway PI3K (phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase)/Akt (protein kinase B)/mTOR, ultimately damaging the testis of mice [36]. In addition, AFB1 can also reduce the gene expression of blood–testis barrier-related connexin by regulating the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway mediated by oxidative stress, aggravate the apoptosis of mouse testicular Sertoli cells, trigger testicular mitochondria dependent apoptosis, and lead to the damage of the blood–testis barrier [37]. Beyond inducing apoptosis, AFB1 also impairs organelle function. AFB1 causes the decrease of mitochondrial complex I–IV activity, resulting in ROS accumulation and mitochondrial damage, leading to the death of testicular cells [62]. For female animals, AFB1 disrupts the normal distribution of mitochondria in oocytes, resulting in insufficient energy supply and exacerbating oxidative stress, and oocyte damage [69].

2.5. Weaken Immunity

The immune system is composed of immune organs, immune cells and immune active substances, which has the function of recognizing and eliminating foreign objects, maintaining the stability of the internal environment and physiological balance [70]. In aquatic animals, AFB1 reduces the activity of immunoregulatory proteins, acyl carrier proteins and immunoglobulin M in the skin, spleen, head and kidney of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) [45]. Ottinger et al. [71] reported that the proliferation of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) lymphocytes was inhibited by AFB1 and immunoglobulin decreased. In poultry, AFB1 exposure increases the expression of pro-inflammatory factor interferon γ in the jejunum of broilers and induces a decrease in the expression of anti-inflammatory factor interleukin 10 in the liver, resulting in intestinal and liver damage in broilers [72]. It has been reported that AFB1 can cause inflammatory cell infiltration in the livers of rats [59], increase the number of inflammatory cells in the livers of chickens and induce intestinal inflammation in rabbits [42,52], thus causing varying degrees of damage to the immune system.

The decrease of immune function by AFB1 may be related to the injury of immune organs and immune cells. The gut, liver, spleen, bursa of Fabricius, macrophages, etc. are important defense lines and components of the immune system [45,73,74]. AFB1 can cause cell oxidative damage, lead to liver lipid peroxidation, and ultimately suppress immune function [75,76]. When the NF-κB signaling pathway of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) infected with AFB1 was activated, the gene expression of pro-inflammatory factors in spleen and kidney were increased, the expression of anti-inflammatory factors were decreased, and the immune ability of skin, spleen and kidney were decreased, leading to damage to these organs [45]. AFB1 causes mitochondrial respiratory chain damage and induces oxidative stress in macrophages, which leads to inflammatory response activation and phagocyte damage [77]. Also, AFB1 can induce bursa tissue damage, cell cycle arrest and mitochondrial apoptosis in broilers, thereby damaging the immune system [73,76]. The decline of immune function in broilers is directly related to AFB1-induced DNA damage and increased thymocyte apoptosis mediated by mitochondria and the death receptor pathway [75].

2.6. Remaining in Animal Products

Meat, eggs and milk are all important protein sources for humans, but AFB1 can accumulate in the body and animal products through the food chain, causing pollution and threatening food safety [78,79,80]. In dairy cows, AFB1 can be detected in milk within 12 h after feeding the AFB1-contaminated diet. After continuous feeding for 7 d, the concentration of AFB1 tends to be stable, but it can still be detected in milk [79]. After feeding Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) with 2 μg/kg of AFB1 in the diet for 14 weeks, the content of AFB1 in muscle was 21.18 μg/kg [81]. When fed a diet containing 6400 μg/kg of AFB1, the content of AFB1 in liver and muscle of broilers was 6.97 ng/g and 3.27 ng/g, respectively [82]. Peng et al. [83] added 1 mg/kg of AFB1 to the diet to feed Lateolabrax maculatus for 56 d, and the detected concentration of AFB1 in muscle was 0.02 μg/kg.

The accumulation of AFB1 in the body may be related to its barrier penetration and metabolic transformation. AFB1 destroys the intestinal barrier by compromising intestinal integrity, damaging the mucosal layer or regulating inflammatory factors [82]. AFB1 can also destroy the blood–brain barrier and kill microvascular endothelial cells [83]. Besides, AFB1 can enter the brain tissue of zebrafish through the blood–brain barrier, resulting in nerve regulation injury and lipid metabolism disorder [84]. In addition, after AFB1 enters the body, it can be further activated by phase I drug metabolism enzymes (such as cytochrome P450 system) to form highly toxic products, which can bind with DNA or protein, exist in the organ and cause damage to the body [85].

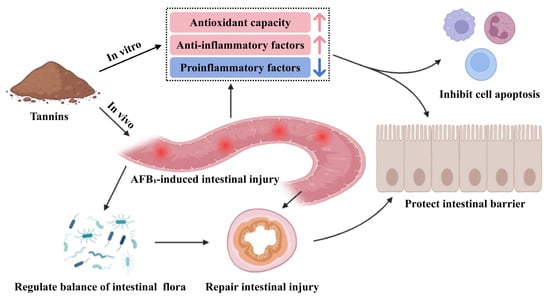

3. Potential Mechanism of Tannins in Alleviating the Toxicity of AFB1

Tannins mitigate AFB1 toxicity probably by alleviating AFB1-induced intestinal inflammation and cellular damage, which is achieved through restoring the stability of intestinal flora, activating antioxidant and anti-inflammatory factors as well as cell signaling pathways (Figure 3). The positive effects of tannins in alleviating AFB1 toxicity are shown in Table 2.

Figure 3.

Tannins alleviate the toxicity of AFB1.

Table 2.

Positive effects of tannins in alleviating AFB1 toxicity.

3.1. Regulating Intestinal Health

Intestinal barrier function and intestinal flora balance are essential to maintain animal intestinal health. Tannic acid can increase the activity of glutathione peroxidase in the jejunum of piglets and up-regulate the gene expression of intestinal tight junction proteins ZO-1, Claudin-3 and occludin, and repair intestinal damage [90]. Procyanidins can increase the relative abundance of beneficial bacteria Bacillus in the intestine of juvenile American eel (Anguilla rostrata), reduce the relative abundance of harmful bacteria Pseudomonas and Aeromonas, and maintain the balance of intestinal flora [91]. Gallnut tannic acid can reduce the relative abundance of harmful bacteria in the intestine of largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides), such as Aeromonas and Achromobacter, and optimize the structure of intestinal flora [92]. The addition of 500 mg/kg tannic acid in feed increased the height of intestinal villi and the depth of crypt in broilers, and increased the activities of intestinal superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase, thereby alleviating the intestinal injury caused by AFB1 [89]. Adding 1 g/kg of condensed tannin to the diet of Lateolabrax maculatus can up-regulate the gene expression of intestinal tight junction proteins (i.e., ZO-1, Claudin-3 and occludin), and repair the intestinal barrier function damage induced by AFB1 [78]. Peng et al. [87] reported that the addition of 1 mg/kg of AFB1 to the diet increased the relative abundance of Aeromonas and Klebsiella in the intestinal tract of Lateolabrax maculatus, while the addition of 1 g/kg of condensed tannin could inhibit the proliferation of harmful bacteria. The addition of tannic acid in feed can increase the relative abundance of lactic acid bacteria in the intestinal tract of broilers, protect the host intestinal tract from pathogenic bacteria by synthesizing bacteriocin, and alleviate the toxicity of AFB1 [89,93].

3.2. Activating Antioxidant and Immune Signaling Pathways

Antioxidation and immunity constitute an important part of defense, which are interrelated and play a major role in maintaining body health and preventing diseases [93]. Peng et al. [29] reported that condensed tannin can activate the Nrf2 (nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2) signaling pathway in the hepatopancreas of Litopenaeus vannamei, and up-regulate the gene expression of SOD and GPX4 (glutathione peroxidase 4) to improve the antioxidant capacity of shrimp. Similar studies have also been carried out in the spleen of Ctenopharyngodon idella and in the liver of Lateolabrax japonicus. For instance, condensed tannin up-regulated the gene expression of antioxidant enzymes by activating the Nrf2 antioxidant signaling pathway and alleviated the oxidative damage caused by AFB1 [94,95]. In the jejunum of lambs, condensed tannin induced a decrease in the gene expression levels of antioxidant factors glutathione peroxidase 1 and GPX4, and increased the gene expression levels of CAT and glutathione peroxidase 2 in the ileum, thereby alleviating oxidative damage in the small intestine of lamb [31]. Proanthocyanins reduce AFB1-induced DNA damage, decrease the frequency of micronuclei and DNA strand breaks in the bone marrow cells of rat, and restore the expression levels of tumor proteins, thus alleviating AFB1-induced DNA oxidative damage in rats [88]. Hydrolyzed tannins exhibit effective anti-inflammatory effects by down-regulating the gene expression levels of the NF-κB signaling pathway and mitogen-activated protein kinase in RAW 264.7 cells, thereby enhancing cellular immunity [96]. Related studies have shown that grape seed anthocyanins reduce the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines by inhibiting inflammation and the NF-κB signaling pathway, while activating the Nrf2 pathway and up-regulating the gene expression levels of heme oxygenase-1, quinone oxidoreductase 1, and glutamate cysteine ligase, enhancing the antioxidant capacity of broiler chickens and alleviating oxidative stress and immune damage induced by AFB1 [47,86].

3.3. Inhibiting Cell Apoptosis

Apoptosis is a fundamental biological phenomenon of cells, which is a programmed cell death phenomenon that occurs in multicellular organisms. It has been shown that supplementation of hydrolyzed tannin in diet can reduce mitosis and cell apoptosis in the cecum and colon of pigs [97]. Proanthocyanins alleviate liver cell pyroptosis by clearing ROS and inhibiting the activation of inflammasome NLRP3 in the liver [98]. Tannic acid inhibits the phosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein kinase in SH-SY5Y (human neuroblastoma cells) through the PI3K/Akt/Ntf2 signaling axis, thereby suppressing cell apoptosis [99]. Tannic acid can bind to TNF-α (tumor necrosis factor alpha) in the liver of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella), and inhibit apoptosis of liver cells by suppressing the TNF-α signaling pathway [100]. Yulak et al. [101] reported that tannic acid inhibits H2O2-induced oxidative damage in SH-SY5Y cells, thereby alleviating cell apoptosis. AFB1 induces mitochondrial apoptosis in broiler liver cells by up-regulating the gene expression levels of Bax, caspase-3, and tumor suppressor gene p53. When anthocyanins are added to broiler feed, these gene expression levels are significantly down-regulated, indicating that anthocyanins inhibit liver cell apoptosis caused by AFB1 [30]. It is worth noting that these studies are based on specific animal models and specific tannin types; further study should be more precise in distinguishing between species-specific or compound-specific effects versus general phenomena when clarifying the exact mechanism of tannins.

4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

AFB1 is a globally recognized Class I carcinogen that can transmit pollution to feedstuffs through crops or the environment, thereby endangering farmed animals. The harm of AFB1 to animals includes growth inhibition, liver and intestinal injury, reproductive performance and immune function reduction, and its accumulation in animal products, thereby threatening animal health and food safety. Tannins are natural polyphenolic compounds widely existing in the plant kingdom, with significant biological activities such as antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, and stress resistance. In recent years, it has been found that tannins can repair the damage caused by AFB1 in animals, demonstrating good detoxification effects. Their pathways of action include regulating animal intestinal health, activating cellular antioxidant and immune signaling pathways, and inhibiting cell apoptosis. However, the molecular mechanisms by which tannins alleviate AFB1 toxicity need further in-depth research. This article summarizes the harm of AFB1 to animals and the mitigating mechanisms of tannins, providing reference for the development of tannin resources and healthful farming.

Although significant progress has been made in research on the mitigation of AFB1 toxicity by tannins, several key areas require further in-depth exploration. Specifically, the structure–activity relationships of different types of tannins, their interaction mechanisms with AFB1, as well as their metabolic processes and active forms in various animal species remain unclear. At the molecular level, the precise regulatory targets of pathways such as Nrf2 and NF-κB need further investigation, while studies on the synergistic effects and compatibility with probiotics, minerals, and other substances are insufficient. Additionally, it is necessary to determine the safe dosage thresholds for different animal species and further explore the impacts of feed processing, storage, and environmental factors on the stability of tannins. Comprehensive research across multiple dimensions will facilitate the standardized application of tannins in healthy animal farming.

Author Contributions

Writing-original draft, W.S.; Supervision, Visualization, Project administration, R.D.; G.W.; B.C. and X.Z.; Writing-review & editing, Z.W.J.P. and J.-Y.L.; Supervision, Project administration J.C.; Writing-original draft, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Validation, Writing-review & editing, K.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Special Fund for Scientific Innovation Strategy-Construction of High-Level Academy of Agriculture Science (R2021PY-QY001), and the Scientific Innovation Strategy-Construction of Construction of Main Force of Agricultural Scientific Research (R2023PY-QN003).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not involve human or animal subjects; therefore, no approvals for human or animal research were necessary.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No research data is used in this article, and all sources of information are linked with Digital Object Identifiers (DOIs) and URLs in the reference list.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AFB1 | aflatoxin B1 |

| Akt | protein kinase B |

| FXR | Farnesoid X Receptor |

| GPX4 | glutathione peroxidase 4 |

| IL-18 | interleukin-18 |

| CAT | catalase |

| IL-1β | inflammatory cytokines interleukin-1β |

| LPS | lipopolysaccharide |

| caspase-1 | cysteine protease caspase-1 |

| mTOR | mammalian target of rapamycin |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor kappa B |

| NLRP3 | nod-like receptor thermoprotein domain related protein 3 |

| Nrf2 | nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| PI3K | phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| SH-SY5Y | human neuroblastoma cells |

| SOD | superoxide dismutase |

| MDA | malondialdehyde |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| ZO-1 | zonula occludens-1 |

References

- Girolami, F.; Barbarossa, A.; Badino, P.; Ghadiri, S.; Cavallini, D.; Zaghini, A.; Nebbia, C. Effects of turmeric powder on aflatoxin M1 and aflatoxicol excretion in milk from dairy cows exposed to aflatoxin B1 at the EU maximum tolerable levels. Toxins 2022, 14, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellafiora, L.; Galaverna, G.; Reverberi, M.; Dall’Asta, C. Degradation of aflatoxins by means of laccases from trametes versicolor: An in silico insight. Toxins 2017, 9, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawal, S.; Kim, J.; Coulomb, J. Aflatoxin B1 in poultry: Toxicology, metabolism and prevention. Res. Vet. Sci. 2010, 89, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarker, M.; Wan, X.; Yang, H.; Wang, Z. Dietary lycopene supplementation could alleviate aflatoxin B1 induced intestinal damage through improving immune function and anti-oxidant capacity in broilers. Animals 2021, 11, 3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zheng, W.; Zhao, L.; Ji, C. A survey report on the mycotoxin contamination of compound feed and its raw materials of China in 2019–2020. Feed. Ind. 2022, 43, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Qisha, R.; Zhou, J.; Wang, C.; Zheng, W.; Lei, Y.; Ji, C. A survey on the mycotoxin contamination of domestic feed and raw materials in 2021. Feed. Ind. 2022, 43, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Qisha, R.; Lei, Y.; Zheng, W.; Lei, L. A survey report on the mycotoxin contamination of Chinese Raw materials and feed in 2022. Feed. Ind. 2024, 45, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottenger, L.; Andrews, L.; Bachman, A.; Boogaard, P.; Cadet, J.; Embry, M.; Farmer, P.; Himmelstein, M.; Jarabek, A.; Martin, E.; et al. An organizational approach for the assessment of DNA adduct data in risk assessment: Case studies for aflatoxin B1, tamoxifen and vinyl chloride. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2014, 44, 348–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efsa Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM); Schrenk, D.; Bignami, M.; Bodin, L.; Chipman, J.; Mazo, J.; Grasl-Kraupp, B.; Hogstrand, C.; Hoogenboom, L.; Leblanc, J.; et al. Risk assessment of aflatoxins in food. Efsa J. 2020, 18, e06040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabiulla, I.; Malathi, V.; Swamy, H.; Naik, J.; Pineda, L.; Han, Y. The efficacy of a smectite-based mycotoxin binder in reducing aflatoxin B1 toxicity on performance, health and histopathology of broiler chickens. Toxins 2021, 13, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Ramírez, J.; Merino-Guzmán, R.; Téllez-Isaías, G.; Vázquez-Durán, A.; Méndez-Albores, A. Mitigation of AFB1-related toxic damage to the intestinal epithelium in broiler chickens consumed a yeast cell wall fraction. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 677965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olarotimi, O.; Gbore, F.; Adu, O.; Oloruntola, O.; Jimoh, O. Ameliorative effects of Sida acuta and vitamin C on serum DNA damage, pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in roosters fed aflatoxin B1 contaminated diets. Toxicon 2023, 236, 107330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amminikutty, N.; Spalenza, V.; Jarriyawattanachaikul, W.; Badino, P.; Capucchio, M.; Colombino, E.; Schiavone, A.; Greco, D.; D’Ascanio, V.; Avantaggiato, G.; et al. Turmeric powder counteracts oxidative stress and reduces AFB1 content in the liver of broilers exposed to the EU maximum levels of the mycotoxin. Toxins 2023, 15, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.; Wang, T.; Wang, P.; Yin, Q.; Liu, C.; Zhu, Q.; Lu, F.; Gao, T. Compound probiotics alleviating aflatoxin B1 and zearalenone toxic effects on broiler production performance and gut microbiota. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 194, 110420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar, P.; Shokrzadeh, M.; Raeisi, S.; HasanSaraei, A.; Nasiraii, L. Aflatoxins biodetoxification strategies based on probiotic bacteria. Toxicon 2020, 178, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kövesi, B.; Pelyhe, C.; Zándoki, E.; Mézes, M.; Balogh, K. Combined effects of aflatoxin B1 and deoxynivalenol on the expression of glutathione redox system regulatory genes in common carp. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2020, 104, 1531–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murcia, H.; Diaz, G. Protective effect of glutathione S-transferase enzyme activity against aflatoxin B1 in poultry species: Relationship between glutathione S-transferase enzyme kinetic parameters, and resistance to aflatoxin B1. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 101235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Deng, J.; Ma, L.; Zhang, W.; Khalil, M.; Karrow, N.; Qi, D.; Sun, L. Dietary Se deficiency dysregulates metabolic and cell death signaling in aggravating the AFB1 hepatotoxicity of chicks. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2021, 149, 111938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatekeli, S.; Demirel, H.; Zemheri-Navruz, F.; Ince, S. Boron exhibits hepatoprotective effect together with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic pathways in rats exposed to aflatoxin B1. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2023, 77, 127127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Liu, X.; Zhao, G.; Hu, T.; Wang, Y. Potential and challenges of tannins as an alternative to in-feed antibiotics for farm animal production. Anim. Nutr. 2018, 4, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Huang, W.; Wang, Y.; Peng, K. Research progress in regulation of tannins on intestinal microbiota of animals. Chin. J. Anim. Nutr. 2023, 35, 772–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Qiu, J.; Wang, Y.; Huang, W.; Zhao, H.; Zhu, X.; Peng, K. Condensed tannins increased intestinal permeability of Chinese seabass (Lateolabrax maculatus) based on microbiome-metabolomics analysis. Aquaculture 2022, 560, 738615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Chen, B.; Huang, W.; Zhao, H.; Hu, J.; Loh, J.; Peng, K. Dietary condensed tannin exhibits stronger growth-inhibiting effect on Chinese sea bass than hydrolysable tannin. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2024, 308, 115880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalle, Z.; Elena, C. Dietary inclusion of tannin extract from red quebracho trees (Schinopsis spp.) in the rabbit meat production. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 8 (Suppl. 2), 784–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagi, G.; Cipollini, I.; Paulicks, B.; Roth, F. Effect of tannins on growth performance and intestinal ecosystem in weaned piglets. Arch. Anim. Nutr. 2010, 64, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starcevic, K.; Krstulovic, L.; Brozic, D.; Mauric, M.; Stojevic, Z.; Mikulec, Z.; Bajic, M.; Masek, T. Production performance, meat composition and oxidative susceptibility in broiler chicken fed with different phenolic compounds. J. Environ. Sci. 2015, 95, 1172–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.; He, W.; Fan, X.; Guo, A. Biological function of plant tannin and its application in animal health. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 8, 803657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, K.; Chen, B.; Zhao, H.; Huang, W. Toxic effects of aflatoxin B1 in Chinese sea bass (Lateolabrax maculatus). Toxins 2021, 13, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, K.; Huang, W.; Zhao, H.; Sun, Y.; Chen, B. Dietary condensed tannins improved growth performance and antioxidant function but impaired intestinal morphology of Litopenaeus vannamei. Aquac. Res. 2021, 21, 100853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, S.; Zhang, C.; Feng, Y.; Wei, X.; Khalil, M.; Rajput, I.; Baloch, D.; Shaukat, A.; Rajput, N.; Qamar, H.; et al. Proanthocyanidins alleviates aflatoxinB1-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis through mitochondrial pathway in the bursa of fabricius of broilers. Toxins 2019, 11, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelegrin-Valls, J.; Álvarez-Rodríguez, J.; Martín-Alonso, M.; Ramírez, G.; Baila, C.; Lobon, S.; Joy, M.; Serrano-Pérez, B. Effect of maternal dietary condensed tannins from sainfoin (Onobrychis viciifolia) on gut health and antioxidant-immune crosstalk in suckling lambs. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, I.; Chauhan, S. Studies on production performance and toxin residues in tissues and eggs of layer chickens fed on diets with various concentrations of aflatoxin AFB1. Br. Poult. Sci. 2007, 48, 713–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanian, E.; Mahdavi, A.; Asgary, S.; Jahanian, R. Effect of dietary supplementation of mannanoligosaccharides on growth performance, ileal microbial counts, and jejunal morphology in broiler chicks exposed to aflatoxins. Livest. Sci. 2016, 190, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zuo, Z.; Chen, K.; Gao, C.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, S.; Li, J.; Song, H.; Peng, X.; Fang, J.; et al. Histopathological injuries, ultrastructural changes, and depressed TLR expression in the small intestine of broiler chickens with aflatoxin B1. Toxins 2018, 10, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, J.; Yuan, Q.; Yan, H.; Tian, G.; Chen, D.; He, J.; Zheng, P.; Yu, J.; Mao, X.; Huang, Z.; et al. Effects of chronic exposure to low levels of dietary aflatoxin B1 on growth performance, apparent total tract digestibility and intestinal health in pigs. Animals 2021, 11, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, J.; Ji, Q.; Li, Y. Aflatoxin B1 promotes autophagy associated with oxidative stress-related PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in mice testis. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 255, 113317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Liu, M.; Xiao, B.; Zhang, J.; Song, M.; Li, Y.; Cao, Z. Aflatoxin B1 disrupts blood-testis barrier integrity by reducing junction protein and promoting apoptosis in mice testes. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2021, 148, 111972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, L.; Chen, H.; Tsim, K.; Shen, X.; Li, X.; Lei, H.; Liu, Y. Aflatoxin B1 induces inflammatory liver injury via gut microbiota in mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 10787–10797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Cheng, D.; Zhang, J.; Tang, H.; Li, F.; Peng, Y.; Duan, X.; Meng, E.; Zhang, C.; Zeng, T.; et al. Role of macrophage AHR/TLR4/STAT3 signaling axis in the colitis induced by non-canonical AHR ligand aflatoxin B1. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 452, 131262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Jiao, P.; Wang, X.; Sun, Y.; Liang, G.; Xie, X.; Zhang, Y. Evaluation of growth performance, nitrogen balance and blood metabolites of mutton sheep fed an ammonia-treated aflatoxin B1-contaminated diet. Toxins 2022, 14, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Peng, J.; Hao, J.; Wang, X.; Xu, M.; Li, S. Growth performance, digestibility, and plasma metabolomic profiles of Saanen goats exposed to different doses of aflatoxin B1. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 9552–9563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Li, M.; Xu, J.; Wang, J.; Li, M.; Wei, L.; Lv, Q.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; et al. SeMet attenuates AFB1-induced intestinal injury in rabbits by activating the Nrf2 pathway. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 239, 113640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Xie, R.; Huang, W.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, M.; Lu, B.; Li, B.; Tan, B.; Dong, X. Negative effects of aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) in the diet on growth performance, protein and lipid metabolism, and liver health of juvenile hybrid grouper (Epinephelus fuscoguttatus ♀ × Epinephelus lanceolatus ♂). Aquac. Rep. 2023, 33, 101779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Kong, Y.; Zou, J.; Wu, X.; Yin, Z.; Niu, X.; Wang, G. Transcriptome and physiological analyses reveal the mechanism of the liver injury and pathological alterations in northern snakehead (Channa argus) after dietary exposure to aflatoxin B1. Aquaculture 2022, 561, 738727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zeng, Z.; Wu, P.; Jiang, W.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, J.; Kuang, S.; Tang, L.; Feng, L.; Zhou, X. Dietary Aflatoxin B1 attenuates immune function of immune organs in grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) by modulating NF-κB and the TOR signaling pathway. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1027064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Q.; Tan, H. Effects of aflatoxin B1 on growth performance, carcass traits, organ index, blood biochemistry and oxidative status in Chinese yellow chickens. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2023, 85, 1015–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajput, S.; Sun, L.; Zhang, N.; Khalil, M.; Ling, Z.; Chong, L.; Wang, S.; Rajput, I.; Bloch, D.; Khan, F.; et al. Ameliorative effects of grape seed proanthocyanidin extract on growth performance, immune function, antioxidant capacity, biochemical constituents, liver histopathology and aflatoxin residues in broilers exposed to aflatoxin B1. Toxins 2017, 9, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denli, M.; Blandon, J.; Guynot, M.; Salado, S.; Perez, J. Effects of dietary AflaDetox on performance, serum biochemistry, histopathological changes, and aflatoxin residues in broilers exposed to aflatoxin B1. Poult. Sci. 2009, 88, 1444–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, Q.; Wang, J.; Sun, J.; Xiang, Y.; Jin, X. Aflatoxin B1 disrupts the intestinal barrier integrity by reducing junction protein and promoting apoptosis in pigs and mice. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 247, 114250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos-Hernández, A.; Farias, S.; Torres-Arreola, W.; Ezquerra-Brauer, J. In vitro studies of the effects of aflatoxin B1 and fumonisin B1 on trypsin-like and collagenase-like activity from the hepatopancreas of white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Aquaculture 2005, 250, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoseyni, S.; Imani, A.; Vazirzadeh, A.; Sarvi Moghanlou, K.; Farhadi, A.; Razi, M. Dietary aflatoxin B1 and zearalenone contamination affected growth performance, intestinal and hepatopancreas gene expression profiles and histology of the intestine and gill in goldfish, Carassius auratus. Aquac. Rep. 2024, 34, 101887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Mishra, S.; Wang, T.; Xu, Z.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Yin, H.; Fan, X.; Zeng, B.; Yang, M.; et al. AFB1 induced transcriptional regulation related to apoptosis and lipid metabolism in liver of chicken. Toxins 2020, 12, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinrinde, A.; Ogunbunmi, T.; Akinrinmade, F. Acute aflatoxin B1-induced gastro-duodenal and hepatic oxidative damage is preceded by time-dependent hyperlactatemia in rats. Mycotoxin Res. 2020, 36, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, P.; Gaddam, N.; Chandler, V.; Chakraborty, S. Oxidative stress-induced liver damage and remodeling of the liver vasculature. Am. J. Pathol. 2023, 193, 1400–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, T.; Lichtfouse, E.; Mochiwa, Z.; Wang, J.; Han, B.; Gao, L. Detection of aflatoxin B1 using DNA sensors: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2025, 23, 1425–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Kang, W.; Liu, S.; Liu, J.; Shi, M.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, X.; Huang, K. Aflatoxin B1 induces liver injury by disturbing gut microbiota-bile acid-FXR axis in mice. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2023, 176, 113751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Lin, S.; Wan, B.; Velani, B.; Zhu, Y. Pyroptosis in liver disease: New insights into disease mechanisms. Aging Dis. 2019, 10, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaul, S.; Leszczynska, A.; Alegre, F.; Kaufmann, B.; Johnson, C.; Adams, L.; Wree, A.; Damm, G.; Seehofer, D.; Calvente, C.; et al. Hepatocyte pyroptosis and release of inflammasome particles induce stellate cell activation and liver fibrosis. J. Hepatol. 2021, 74, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Zhan, D.; Chen, Y.; Wang, W.; He, C.; Lin, Y.; Lin, Y.; Lin, Z. Aflatoxin B1 enhances pyroptosis of hepatocytes and activation of kupffer cells to promote liver inflammatory injury via dephosphorylation of cyclooxygenase-2: An in vitro, ex vivo and in vivo study. Arch. Toxicol. 2019, 93, 3305–3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Bao, X.; Meng, L.; Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Zheng, N. Aflatoxin B1 and aflatoxin M1 induce compromised intestinal integrity through clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Toxins 2021, 13, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, A.; Saleemi, M.; Mohsin, M.; Gul, S.; Zubair, M.; Muhammad, F.; Bhatti, S.; Hameed, M.; Imran, M.; Irshad, H.; et al. Pathological effects of graded doses of aflatoxin B1 on the development of the testes in juvenile white leghorn males. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 53158–53167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Cao, Z.; Yao, Q.; Ji, Q.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y. Mitochondrial damage are involved in Aflatoxin B1-induced testicular damage and spermatogenesis disorder in mice. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 701, 135077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Dong, G.; Liao, M.; Tao, L.; Lv, J. The effects of low levels of aflatoxin B1 on health, growth performance and reproductivity in male rabbits. World Rabbit Sci. 2018, 26, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Han, D.; Xiao, X.; Zhu, X.; Yang, Y.; Jin, J.; Chen, Y.; Xie, S. Effect of dietary aflatoxin B1 on growth, fecundity and tissue accumulation in gibel carp during the stage of gonad development. Aquaculture 2014, 428, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanzadeh, S.; Amani, S. Aflatoxin B1 effects on ovarian follicular growth and atresia in the rat. Comp. Clin. Pathol. 2013, 22, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, Q.; Han, J.; Xiong, B.; Sun, S. Aflatoxin B1 is toxic to porcine oocyte maturation. Mutagenesis 2015, 30, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zou, P.; Jia, L.; Su, T.; Sun, Y.; Sun, C. Comparison of the toxic effects of different mycotoxins on porcine and mouse oocyte meiosis. PeerJ 2018, 6, e5111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Wang, J.; Ma, L.; Chen, L.; Guo, T.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, H.; Yu, Y. Oxidative DNA damage and multi-organ pathologies in male mice subchronically treated with aflatoxin B1. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 186, 109697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Duan, H.; Zou, Y.; Sun, S.; Hu, L. Aflatoxin B1 exposure disrupts organelle distribution in mouse oocytes. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y. Advances in drug development based on immunoregulation. China Pharm. Univ. 2024, 55, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottinger, C.; Kaattari, S. Sensitivity of rainbow trout leucocytes to aflatoxin B1. Fish Shellfish Immun. 1998, 8, 515–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, W.; Wang, X.; Han, M.; Muhammad, I.; Zhang, X.; Sun, X.; Cui, X. Water-soluble substances of wheat: A potential preventer of aflatoxin B1-induced liver damage in broilers. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Ma, Q.; Ji, C.; Zhao, L. Transcriptional profiling of aflatoxin B1-induced oxidative stress and inflammatory response in macrophages. Toxins 2021, 13, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, P.; Zuo, Z.; Li, H.; Wang, F.; Peng, X.; Fang, J.; Cui, H.; Gao, C.; Song, H.; Zhou, Y.; et al. The molecular mechanism of cell cycle arrest in the Bursa of Fabricius in chick exposed to Aflatoxin B1. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, X.; Yu, Z.; Liang, N.; Chi, X.; Li, X.; Jiang, M.; Fang, J.; Cui, H.; Lai, W.; Zhou, Y.; et al. The mitochondrial and death receptor pathways involved in the thymocytes apoptosis induced by aflatoxin B1. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 12222–12234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Wu, B.; Yu, Z.; Fang, J.; Liang, N.; Zhou, M.; Huang, C.; Peng, X. The mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum pathways involved in the apoptosis of bursa of Fabricius cells in broilers exposed to dietary aflatoxin B1. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 65295–65306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, K.; Chen, B.; Zhao, H.; Zheng, C.; Wang, Y.; Luo, C.; Huang, W. Condensed tannins alleviate aflatoxin B1-induced injury in Chinese sea bass (Lateolabrax maculatus). Aquaculture 2022, 552, 738029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, M.; Wang, E.; Hao, Y.; Ji, S.; Huang, S.; Zhao, L.; Wang, W.; Shao, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, S. Adsorbents reduce aflatoxin M1 residue in milk of healthy dairy cow exposed to moderate level aflatoxin B1 in diet and its exposure risk for humans. Toxins 2021, 13, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Z.; Khan, M.; Khan, A.; Javed, I.; Saleemi, M.; Mahmood, S.; Asi, M. Residues of aflatoxin B1 in broiler meat: Effect of age and dietary aflatoxin B1 levels. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2010, 48, 3304–3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyat, M.; Ayyat, A.; Al-Sagheer, A.; El-Hais, A. Effect of some safe feed additives on growth performance, blood biochemistry, and bioaccumulation of aflatoxin residues of Nile tilapia fed aflatoxin-B1 contaminated diet. Aquaculture 2018, 495, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Meng, L.; Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Zheng, N. The compromised intestinal barrier induced by mycotoxins. Toxins 2020, 12, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qureshi, H.; Hamid, S.; Ali, S.; Anwar, J.; Siddiqui, A.; Khan, N. Cytotoxic effects of aflatoxin B1 on human brain microvascular endothelial cells of the blood-brain barrier. Med. Mycol. 2015, 53, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Wang, T.; Liao, G.; Gu, J.; Hou, R.; Qiu, J. Lipidomic profiling study on neurobehavior toxicity in zebrafish treated with aflatoxin B1. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 898, 165553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, P.; Lootens, O.; Kabeta, T.; Reckelbus, D.; Furman, N.; Cao, X.; Zhang, S.; Antonissen, G.; Croubels, S.; Boevre, M.; et al. Exploration of Cytochrome P450-Related Interactions between Aflatoxin B1 and Tiamulin in Broiler Chickens. Toxins 2024, 16, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, S.; Sun, L.; Zhang, N.; Khalil, M.; Ling, Z.; Chong, L.; Wang, S.; Rajput, I.; Bloch, D.; Khan, F.; et al. Grape seed proanthocyanidin extract alleviates aflatoxinB1-induced immunotoxicity and oxidative stress via modulation of NF-κB and Nrf2 signaling pathways in broilers. Toxins 2019, 11, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, K.; Chen, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Zheng, C.; Chen, X.; Huang, W. Condensed tannins protect against aflatoxin B1-induced toxicity in Lateolabrax maculatus by restoring intestinal integrity and regulating bacterial microbiota. Aquaculture 2022, 555, 738255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakheet, S.; Alhuraishi, A.; Al-Harbi, N.; Al-Hosaini, K.; Al-Sharary, S.; Attia, M.; Alhoshani, A.; Al-Shabanah, O.; Al-Harbi, M.; Imam, F.; et al. Alleviation of aflatoxin B1-induced genomic damage by proanthocyanidins via modulation of DNA repair. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2016, 30, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xi, Y.; Wang, S.; Zheng, L.; Qi, T.; Gou, S.; Ding, B. Effects of Chinese gallnut tannic acid on growth performance, blood parameters, antioxidative status, intestinal histomorphology, and cecal microbial shedding in broilers challenged with aflatoxin B1. J. Anim. Sci. 2022, 100, skac099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Huang, H.; Wang, L.; Yin, L.; Yang, H.; Chen, C.; Zheng, Q.; He, S. Tannic acid attenuates intestinal oxidative damage by improving antioxidant capacity and intestinal barrier in weaned piglets and IPEC-J2 cells. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1012207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; He, Y.; Xi, F.; Liang, Y.; Zhai, S. Oligomeric proanthocyanidins alleviate the detrimental effects of dietary histamine on intestinal health of juvenile American eels (Anguilla rostrata). Fishes 2023, 8, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Q.; Yuan, Q.; Zhou, X.; Wang, X.; Li, H.; Long, X. Effects of gallnut tannin acid on growth performance and intestinal health of Largemouth bass. Chin. J. Anim. Nutr. 2024, 36, 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Yang, Q. Antifungal properties and AFB1 detoxification activity of a new strain of Lactobacillus plantarum. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 414, 125569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, K.; Jia, X.; Fu, C.; Yu, H.; Wang, Y. Antioxidant peptides, the guardian of life from oxidative stress. Med. Res. Rev. 2024, 44, 275–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, K.; Chen, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Zheng, C.; Chen, X.; Huang, W. Condensed tannins enhanced antioxidant capacity and hypoxic stress survivability but not growth performance and fatty acid profile of juvenile Japanese seabass (Lateolabrax japonicus). Anim. Feed Sci. Tech. 2020, 269, 114671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Jiang, W.; Wu, P.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Jiang, J.; Kuang, S.; Tang, L.; Zhou, X.; Feng, L. Dietary aflatoxin B1 decreases growth performance and damages the structural integrity of immune organs in juvenile grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella). Aquaculture 2019, 500, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekambaram, S.; Aruldhas, J.; Srinivasan, A.; Erusappan, T. Modulation of NF-κB and MAPK signalling pathways by hydrolysable tannin fraction from Terminalia chebula fruits contributes to its anti-inflammatory action in RAW 264.7 cells. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2022, 74, 718–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilić-Šobot, D.; Kubale, V.; Škrlep, M.; Čandek-Potokar, M.; Prevolnik Povše, M.; Fazarinc, G.; Škorjanc, D. Effect of hydrolysable tannins on intestinal morphology, proliferation and apoptosis in entire male pigs. Arch. Anim. Nutr. 2016, 70, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Wang, C.; Meng, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Meng, D.; Liu, J.; Yuan, M.; Guan, S. Proanthocyanidins alleviate acute alcohol liver injury by inhibiting pyroptosis via inhibiting the ROS-MLKL-CTSB-NLRP3 pathway. Phytomedicine 2025, 136, 156268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, M.; Ko, R.; Goshima, H.; Koike, A.; Shibano, M.; Fujimori, K. Formononetin attenuates H2O2-induced cell death through decreasing ROS level by PI3K/Akt-Nrf2-activated antioxidant gene expression and suppressing MAPK-regulated apoptosis in neuronal SH-SY5Y cells. Neurotoxicology 2021, 85, 186–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Zhu, H.; Guo, J.; Lei, Y.; Sun, W.; Lin, H. Tannic acid through ROS/TNF-α/TNFR 1 antagonizes atrazine induced apoptosis, programmed necrosis and immune dysfunction of grass carp hepatocytes. Fish Shellfish Immun. 2022, 131, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yulak, F.; Ergul, M. Tannic acid protects neuroblastoma cells against hydrogen peroxide-triggered oxidative stress by suppressing oxidative stress and apoptosis. Brain Res. 2024, 1844, 149175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.