Abstract

Improvements in Botulinum toxin type-A (BoNT-A) aesthetic treatments have been jeopardized by the simplistic statement: “BoNT-A treats wrinkles”. BoNT-A monotherapy relating to wrinkles is, at least, questionable. The BoNT-A mechanism of action is presynaptic cholinergic nerve terminals blockage, causing paralysis and subsequent muscle atrophy. Understanding the real BoNT-A mechanism of action clarifies misconceptions that impact the way scientific productions on the subject are designed, the way aesthetics treatments are proposed, and how limited the results are when the focus is only on wrinkle softening. We designed a systematic review on BoNT-A and muscle atrophy that could enlighten new approaches for aesthetics purposes. A systematic review, targeting articles investigating BoNT-A injection and its correlation to muscle atrophy in animals or humans, filtered 30 publications released before 15 May 2020 in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Histologic analysis and histochemistry showed muscle atrophy with fibrosis, necrosis, and an increase in the number of perimysial fat cells in animal and human models; this was also confirmed by imaging studies. A significant muscle balance reduction of 18% to 60% after single or seriated BoNT-A injections were observed in 9 out of 10 animal studies. Genetic alterations related to muscle atrophy were analyzed by five studies and showed how much impact a single BoNT-A injection can cause on a molecular basis. Seriated or single BoNT-A muscle injections can cause real muscle atrophy on a short or long-term basis, in animal models and in humans. Theoretically, muscular architecture reprogramming is a possible new approach in aesthetics.

Keywords:

botulinum toxins; type A; botox; muscular atrophy; muscle atrophy; wrinkles; ficial lines; aesthelics; esthetics; muscular architecture reprogramming Key Contribution:

A systematic review of literature on muscle atrophy after BoNT-A injections.

1. Introduction

Botulinum toxin type A (BoNT-A) has been historically used for the aesthetic treatment of facial lines. Although there are an increasing number of on-label uses to treat a variety of disorders using BoNT-A, when it comes to aesthetics, all the on-label approvals refer to facial lines [1]. Currently BoNT-A is approved by the FDA for the aesthetic treatment of forehead, glabellar, and lateral canthal lines, while in some other countries, such as Brazil, the on-label aesthetic approval is more generic and permits BoNT-A injections all over the face to treat facial lines [2,3]. The main point is that all the aesthetic on-label approvals concern facial lines only. Numerous published clinical trials objectify the improvement of facial lines after treatment with BoNT-A [4]. A multitude of articles aimed to compare the main brands of BoNT-A available on the market regarding the durability of the effect of softening wrinkles provided by these toxins [5]. Dose comparisons between BoNT-A brands generate misleading results because they are all different and are not interchangeable substances [6,7,8].

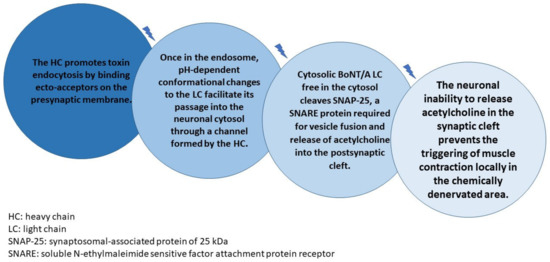

Despite differences in market brands, all currently marketed BoNT-A have one thing in common: a protein complex of 150 kDa composed of a heavy chain (HC, 100 kDa) linked via a disulfide bond to a light chain (LC, 50 kDa) [9,10,11]. After a BoNT-A injection, the simplified mechanism of action cascade can be described based on its biochemical structure [12,13,14,15,16,17] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

BoNT-A injection, the simplified mechanism of action cascade.

The whole cascade takes between 24 to 72 h to be completed after BoNT-A injection, and it is an irreversible process [18]. Once the SNAP-25 (synaptosomal-associated protein of 25 kDa) protein is inactivated, muscle contraction will only be reestablished after neuronal repair that depends on nerve sprouting and/or motor plate regeneration [19]. Although scientific evidence on this statement dates back to the 1970s [20], many still argue today about BoNT-A “durability” in relation to wrinkle control rather than studying the level of tissue damage caused by a BoNT-A injection and the time required for neuronal healing, as concerns aesthetics. The previous sentence is fundamental for the purpose of the new aesthetic approach of BoNT-A use in aesthetics that we intend to propose based on the real BoNT-A mechanism of action.

Many studies have demonstrated nerve terminal and nodal sprouting in the paralyzed nerves as early as two days after botulinum toxin injection [21,22]. Broadening the scope, studies on botulism have already provided a substrate to support the idea that the botulinum toxins durability for practical purposes is approximately 24 to 72 h and that the actual long-term effect of muscle paralysis depends only on nerve and muscle tissue regeneration processes. Treatment with antitoxin for patients with botulism, in order to be effective, should be started within 24 to 48 h of contamination, otherwise the already established neuronal chemical tissue injury is no longer reversible [23]. Once the disease is established by neuronal inability to release acetylcholine in the synaptic cleft of the neuromuscular junction, life support becomes essential, which is normally restricted to clinical care, with special attention to maintaining respiratory capacity, which requires mechanical ventilation for 2 to 6 months, until neuronal and muscular healing processes take place, restoring diaphragmatic and intercostal muscle function [24,25].

Studies addressing counter-terrorism measures suggest the use of antidotes against BoNT-A in the event of a mass attack using BoNT-A as a chemical weapon. Only 1 g of BoNT-A in natura is capable of decimating 1 million humans, showing that it is a powerful and lethal toxin. All of the antidotes tested, even those capable of neuronal internalization, require concern regarding the therapeutic window, which must precede a chemical neuromuscular junction denervation of 24 to 72 h [24,26].

Understanding BoNT-A’s real mechanism of action makes it possible to identify some semantic misconceptions that have been repeated historically since its first use for aesthetic purposes and that directly impact the way scientific productions on the subject are designed, the way aesthetics treatments are proposed, and how limited the results are when the focus is only on wrinkles softening. Considering the statements above and the questions raised below (Table 1), we designed a systematic review on BoNT-A and muscle atrophy that could enlighten new approaches for aesthetics purposes.

Table 1.

Questions that should be answered, based on the evidence, after reading this paper.

2. Aims

To conduct a systematic review of the literature regarding BoNT-A treatments and muscle atrophy that could support new perspectives in facial aesthetics and to propose a new reading for the aesthetic use of BoNT-A, no longer focusing on simple control of wrinkles and facial lines, but as a drug capable of selectively reprogramming long-term muscle strength and tonus through muscle atrophy. We will discuss the proposition that muscle architecture could be altered by creating areas of real atrophy—hyporesponsive or even irresponsive to acetylcholine stimuli for muscle contraction. The restoration of neuronal and muscular function would be based exclusively on the healing processes of these tissues.

3. Method

The present systematic review, targeting articles that investigate BoNT-A injections and its correlation to muscle atrophy in animals or humans, was conducted in a stepwise process for studies published before 15 May 2020 and in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [27]. The search strategy, the flow diagram of study selection, and the data extraction are detailed below, because the review was not registered. By the time our independent research group tried to register the review at PROSPERO in 2020, we had already started article extraction. After October 2019, PROSPERO only accepted earlier registration.

STEP 1—PubMed/MEDLINE and BVS (Biblioteca Virtual em Saúde) databases were explored using the following Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) entry terms: “Botulinum Toxin Type A” OR “Botulinum A Toxin” OR “Botulinum Neurotoxin A” OR “Botox” AND combined with the MeSH entry terms “Muscle Atrophy” OR “Muscular Atrophy” (Table 2). The overlapping studies were excluded in STEP 1.

Table 2.

PubMed/MEDLINE and BVS (Biblioteca Virtual em Saúde) databases Search strategies.

In STEP 2, the studies obtained in STEP 1 were screened by “title” and “abstract” by two independent researchers (A.D.N. and R.F.B.). Those not satisfying inclusion criteria or with exclusion criteria (Table 3) were excluded. The group of articles selected to proceed to the next step was determined through an interactive consensus process. Discrepancies were judged by a third reviewer (S.E.).

Table 3.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

In STEP 3, the full text of all the potential articles selected in STEP 2 were obtained and carefully read to screen for those whose purposes were in accordance with the aim of the present review.

In STEP 4, the eligible studies in STEP 3 were thoroughly read, and data for each study were extracted and analyzed according to a PICO-like structured reading (Table 4).

Table 4.

PICO-like structured reading of the eligible studies and data collection.

The methodological quality of the articles included in the study was evaluated using a specific scale developed based on STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology) principles [28]. Each item was categorized, and the maximum global score was set to 26 (Table 5).

Table 5.

Quality analysis form used in the systematic review.

4. Reults

4.1. Selection of the Studies

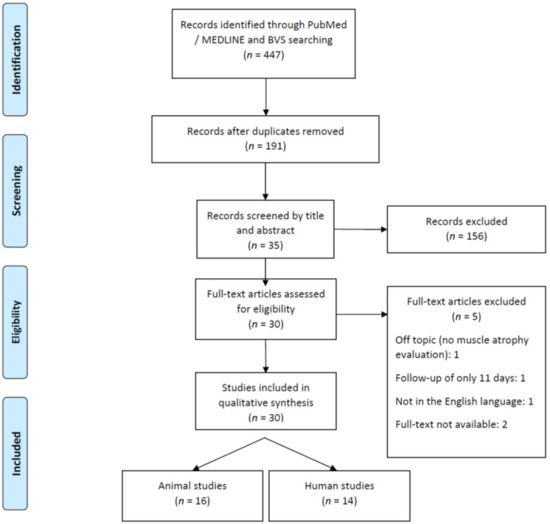

From 191 articles initially identified after removing duplicates, thirty-five were deemed relevant after reading titles and abstracts. Thirty were included in the review (5 were excluded because they did not meet the selection criteria). Sixteen were animal studies and fourteen were human studies. The PRISMA Flow Diagram of Article Selection for Review is summarized in (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

PRISMA—Flow Diagram of Article Selection for Review.

4.2. Quality of the Reviewed Articles

The quality of the reviewed articles was highly variable and is summed up in Table 6 [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58]. Most studies, 28/30, were prospective ones, with 13 well-controlled and randomized, but this subgroup was only of animal studies. The descriptive quality of the experimental protocol results, as well as their interpretations and conclusions, were adequate in most studies. The follow-up ranged from 3 months to 4 years.

Table 6.

Quality assessment. ** maximum global score = 26.

4.3. Literature Analysis

A general overview of the population type of the 30 studies is summarized in Table 7. All Animal studies had good quality control groups. Human studies, on the other hand, lacked control groups or had poor quality control groups.

Table 7.

Systematic review—Summary table of the results (PART 1).

Most animal studies used mature healthy animals. Human studies, on the other hand, used very heterogeneous subjects in relation to age (varying from children to 91-year-old adults) and health status.

Overall, there were very few studies regarding the facial mimetic musculature in humans—only two: Borodic (1992) [29] and Koerte (2013) [47]. The facial masticatory musculature represented mainly by the masseter muscle were studied in three human studies: To (2001) [33], Kim (2005) [34], Lee (2007) [40]; and three animal studies: Kwon (2007) [39], Babuccu (2009) [42], Kocaelli (2016) [54].

Numerical heterogenic population samples (from 1 to 383 subjects) and qualitative heterogenic samples, more specifically in human studies (healthy and subjects with different muscle disorders), were observed.

There was also heterogenic BoNT-A dose, BoNT-A brand types used in the studies and follow-up period, summarized in Table 8.

Table 8.

Systematic review—Summary table of the results (PART 2).

The methodological variability among the small number of studies made it mandatory to conduct an extensive evaluation based on the identification of muscle atrophy after BoNT-A injections registered separately via different tools in animal or human studies. The general findings are summarized in Section 4.3.1. (Animal Studies) and Section 4.3.2. (Human Studies), below.

4.3.1. Animal Studies

Muscle Balance

Muscle balance was measured in 10 out of 16 animal studies to evaluate muscle atrophy. Significant muscle balance reduction after seriated BoNT-A injections and after one single BoNT-A injection were observed in 9 out of 10 studies. The reduction varied from 18%, Fortuna (2013b) [48], to 60%, Fortuna (2011) [44], and there was a BoNT-A dose dependency/interval of injection association identified by Herzog (2007) [37], Frick (2007) [38], Tsai (2010) [43], Fortuna (2011) [44], Fortuna (2013b) [48], and Caron (2015) [51]. The higher the dose, the higher the muscle balance reduction. Long intervals between injections permitted partial muscle balance recovery. Only Fortuna (2015) [50] found no muscle balance alterations after 6 months of injection (Table 9).

Table 9.

Animal studies—Muscle balance.

Optical and Electron Microscopy

Hystologic (optical and electron microscopy) analysis and histochemistry showed profound muscle structure changes in animal models, such as sarcomere distortion, decrease in myofibrillar diameters, and myofibrillolysis/myonecrosis—Babuccu (2009) [42], Tsai (2010) [43], Kocaelli (2016) [54]. Significant reduction of percentage of contractile material—Frick (2007) [38], Fortuna (2011) [44], Fortuna (2013a) [45], Fortuna (2013b) [48], Fortuna (2015) [50]. Replacement of contractile fibers with fat, fatty infiltration, and increased collagen fibers forming perimysium—Herzog (2007) [37], Fortuna (2011) [44], Kocaelli (2016) [54] (Table 10).

Table 10.

Animal studies—Hystologic (optical and electron microscopy) analysis and histochemistry.

Imaging

Kwon (2007) [39] showed a computed tomography (CT) scan rabbit masseter muscle volume reduction of up to 18.41% (±3.15) after 6 months of a BoNT-A injection. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was used in monkeys by Han (2018) [56] and showed significant paraspinal muscles atrophy after BoNT-A injections (Table 11).

Table 11.

Animal studies—Imaging.

Molecular Biology

Direct and indirect muscle atrophy identification via molecular biology was studied and is detailed in Table 12 and Table 13.

Table 12.

Animal studies—Direct and indirect muscle atrophy identification via molecular biology.

Table 13.

Animal studies—Molecular biology.

4.3.2. Human Studies

Optical and Electron Microscopy

Histologic (optical and electron microscopy) analysis and histochemistry showed results in humans similar to those found in animal models. Muscle atrophy (atrophic muscle fibers, myofibrillar disorganization, fibrosis, necrosis, and increase of the number of perimysial fat cells) were well-documented by Kim (2005) [34], Schroeder (2009) [41], Valentine (2016) [52], and Li (2016) [53]. The Orbicularis oculi muscle showed that the morphometric measurements of muscle fibers reduced, with an irregular diameter at 3 months after BoNT-A injections, (p < 0.05). Ansved (1997) [31] showed a mean diameter reduction of type IIB striated muscle fibers (Vastus lateralis) of 19.6% after 2–4 years of BoNT-A treatement (p < 0.05). Partial recovery of the changes described above were seen in some articles (Table 14).

Table 14.

Human studies—Histologic (optical and electron microscopy) analysis and histochemistry.

Imaging

All the 10 human studies that evaluated images to measure muscle atrophy after BoNT-A treatments showed signs of muscle atrophy, irrespective of the technology used: ultrasound, MRI, CT scan, or cephalometry. Muscle atrophy was registered in the short term (42 days to 3 months) and in the long term (up to 2 years). No full recovery was identified (Table 15).

Table 15.

Human studies—Imaging.

5. Discussion

The use of BoNT-A for cosmetic purposes is a fast-growing procedure, with more than six million treatments performed by plastic surgeons in the year 2018 alone [59]. Despite this significant number, we believe that improvements in BoNT-A aesthetic treatments have been jeopardized by the famous, but simplistic, statement used by the media, patients, and doctors: “BoNT-A treats wrinkles”. BoNT-A monotherapy relating to wrinkles is, at least, questionable. The BoNT-A mechanism of action is presynaptic cholinergic nerve terminals blockage by inhibition of the release of acetylcholine, causing paralysis and subsequent functional denervated muscle atrophy to some degree [60]. It is important to keep in mind that wrinkles have a multitude of causes, besides muscle contraction, and that treatments of wrinkles based only on the use of BTX-A have poor quality results in the long term [61]. Rohrich (2007) [62] brilliantly demonstrated modern topographic anatomic studies proving the relationship between wrinkles and underlying structures other than muscles, such as arteries, veins, nerves, and septa of fat compartments [62].

The use of BTX-A was first studied by Scott (1973) [63] for the treatment of strabismus by pharmacologic weakening the extraocular muscles [33]. The first described use of the toxin in aesthetic circumstances was by Clark and Berris (1989) [64], but it still carried out the essence of the BoNT-A mechanism of action based on muscle paralysis and atrophy [64]. At some point during the 1990s, Carruthers and Carruthers [65] began to use botulinum toxin type A in full-scale treatments for aesthetic purposes. Since then, the aesthetic focus regarding the use of BoNT-A moved towards removing wrinkles only [65]—a shift in the medical literature on BoTN-A for aesthetics purposes that has persisted until today. We are not underestimating the importance of Carruthers and many other authors that previously studied the use of BoNT-A in aesthetics but, as mentioned above, we intend to provide the aesthetic use of BoNT-A a new perspective. The real mechanism of actions of BoNT-A for aesthetic purposes have been forgotten, to a level where recent publications still focus on the fact that muscle paralysis and muscle atrophy is a complication of the “wrinkle treatment” capacity of BoNT-A instead of its expected effect [66,67,68].

This systematic review can shed new light on aesthetic BoNT-A treatments basing itself on old, but scientifically correct, concepts of striated muscle contraction physiology, muscle hypertrophy, and muscle atrophy—basic concepts of muscle physiology from reference physiology medical books such as the Guyton and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology [69].

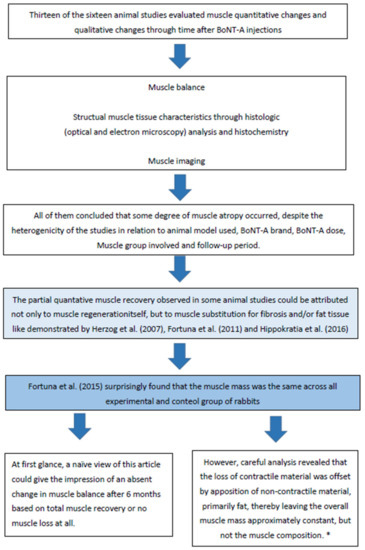

The results of this systematic review showed evidence that seriated or single BoNT-A muscle injections can cause real atrophy on a short or long-term basis, in animal models and in humans, in skeletal striated muscles of the limbs, facial masticatory muscles, and facial mimetic muscles. Due to only limited good quality data being available, we included animal model studies and human studies, but we know that data extrapolation from animal model studies to humans are, at least, naïve. The sensitivity of animals to BoNT-A has been known for many years to be less than that perceived in humans [70]. There are even differences in sensitivity between rats and mice [71]. On this basis, animal studies must be carefully designed and carefully analyzed, or they cannot be interpreted with respect to human effects [72]. Here we will discuss the results of this systematic review, making clear distinguishment between animal model studies and human studies (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Animal model studies results—Discussion overview. * This finding might be of clinical relevance, because muscle volume measured using non-invasive imaging techniques (MRI, ultrasound) are sometimes used to approximate muscle mass in patient populations to determine progression of a disease or success of a treatment intervention—Damiano and Moreau (2008) [73]. Structural integrity and functional properties of muscles, rather than muscle mass or volume, might be more appropriate outcome measures to determine disease progression or aesthetics intervention effects.

Increasing the number of injections did not produce additional loss in muscle strength and contractile material, as one might have suspected, suggesting that most of the muscle damage effects of BTX-A injection into muscles are caused by the first injection, or that the recovery period between injections was sufficient for partial recovery, thereby offsetting the potential damage induced by each injection.

Genetic alterations related to muscle atrophy/recovery through molecular biology were analyzed by five studies and showed how much impact a single BoNT-A injection can cause on a molecular basis. Mukund (2014) [49] realized that the direct action of BTX-A in skeletal muscle is relatively rapid, inducing dramatic transcriptional adaptation at one week and activating genes in competing pathways of repair and atrophy by gene-related impaired mitochondrial biogenesis.

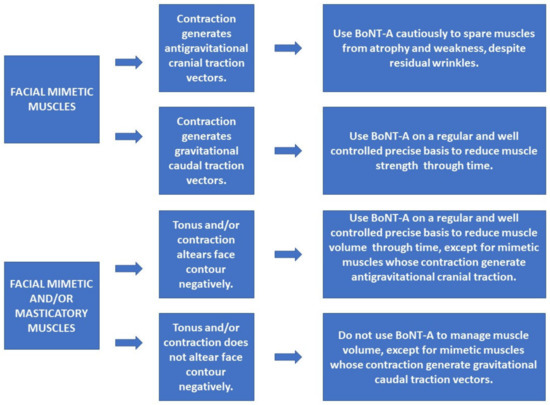

Much like the findings of animal studies, human studies have also clearly shown atrophy in different muscle types after BTX-A injections. All six human studies that evaluated muscle histology showed atrophy, and when muscle recovery was assessed, there was no full recovery—Borodic (1992) [29] and Schroeder (2009) [41]. Bringing this idea into the context of facial aesthetics, the treatment of the Orbicularis oculi muscle, for example, with BTX-A sporadic injections could atrophy this muscle, but serial and controlled treatments could really maintain a certain degree of atrophy capable of allowing a smile with more open eyes, less caudal traction vector in the cranial part of this muscle postponing gravitational aging, and even give less contribution to the formation of the famous periorbital wrinkles, this time, as a secondary effect. Extrapolations of the powerful tool of muscle atrophy control through time using BTX-A injections could change completely the way BTX-A is used for aesthetic purposes. Dosages, injection intervals, and target muscles would be different from the patterns used nowadays. Instead of planning BTX-A injections to treat wrinkles, a modern anatomy understanding of the facial mimetic muscles as described by Boggio (2017) [74] would be of unparallel importance for aesthetic treatment planning [74]. New approaches for facial aesthetic treatments using BoNT-A could be completely based on mimetic facial muscle interactions and focused on reducing the activity of muscles that enhance gravitational aging (facial depressor muscles), such as the platysma muscle, for example, and preserving antigravitational muscles (elevator facial muscles), such as the frontalis (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

New approaches for facial aesthetic treatments using BoNT-A. The human imaging studies, similar to the animal studies, also show muscle atrophy and volume reduction. Koerte (2013) [47] showed a sustained atrophy and volume loss of approximately 50% in the procerus muscle. New perspectives on aesthetics BoNT-A treatments should consider not only facial mimetic muscles and their strength in relation to gravitational or antigravitational contraction vectors, but also their volume. Muscle volume control is also of aesthetic importance. The understanding that some degree of muscle volume reduction would bring positive aesthetic aspects for some mimetic muscles, such as the procerus and corrugators and some masticatory muscles such as the masseter, would also change the current BoNT-A injections patterns. On the other hand, some muscles should be spared from volume loss, such as the frontalis and the lateral aspect of the orbicularis oculi, to avoid facial skeletonization.

After analyzing the results of this paper, we can attempt to answer the questions raised in the introduction (Table 16).

Table 16.

Possible and plausible evidence-based answers for the questions raised in the introduction.

6. Conclusions

This systematic review showed evidence that seriated or single BoNT-A muscle injections can cause real muscle atrophy on a short or long-term basis, in animal models and in humans, in skeletal striated muscles of the limbs, facial masticatory muscles, and facial mimetic muscles. Theoretically, muscular architecture reprogramming is a possible new approach in aesthetics. Depressor facial muscles could be targeted to have some degree of atrophy with BoNT-A injections, while elevator facial muscles could be spared to some degree to maintain antigravitational traction forces and facilitate a lift effect.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D.N.; methodology, A.D.N.; validation, A.D.N.; formal analysis, A.D.N.; investigation, A.D.N.; data curation, A.D.N.; writing—original draft preparation, A.D.N.; writing—review and editing, R.F.B., S.E. and G.E.L.F.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gart, M.S.; Gutowski, K.A. Overview of Botulinum Toxins for Aesthetic Uses. Clin. Plast. Surg. 2016, 43, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallini, M.; Cirillo, P.; Fundarò, S.P.; Quartucci, S.; Sciuto, C.; Sito, G.; Tonini, D.; Trocchi, G.; Signorini, M. Safety of botulinum toxin A in aesthetic treatments: A systematic review of clinical studies. Dermatol. Surg. 2014, 40, 525–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministério da Saúde Consultoria Jurídica/Advocacia Geral da União 1 Nota Técnica N° Nota Técnica N°342/2014. Available online: https://portalarquivos2.saude.gov.br/images/pdf/2014/setembro/17/Toxina-botul--nica-tipo-A.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2019).

- Monheit, G. Neurotoxins: Current Concepts in Cosmetic Use on the Face and Neck–Upper Face (Glabella, Forehead, and Crow’s Feet). Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2015, 136, 72S–75S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonaparte, J.P.; Ellis, D.; Quinn, J.G.; Rabski, J.; Hutton, B. A Comparative Assessment of Three Formulations of Botulinum Toxin Type A for Facial Rhytides: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analyses. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2016, 137, 1125–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brin, M.F.; James, C.; Maltman, J. Botulinum toxin type A products are not interchangeable: A review of the evidence. Biologics 2014, 8, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Albanese, A. Terminology for preparations of botulinum neurotoxins: What a difference a name makes. JAMA 2011, 305, 89–90, Erratum in JAMA 2011, 305, 1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, A.J.; Chang, B.; Taglienti, A.J.; Chin, B.C.; Chang, C.S.; Folsom, N.; Percec, I. A Quantitative Analysis of OnabotulinumtoxinA, AbobotulinumtoxinA, and IncobotulinumtoxinA: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Prospective Clinical Trial of Comparative Dynamic Strain Reduction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2016, 137, 1424–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burgen, A.S.; Dickens, F.; Zatman, L.J. The action of botulinum toxin on the neuro-muscular junction. J. Physiol. 1949, 109, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, L.L. The origin, structure, and pharmacological activity of botulinum toxin. Pharmacol. Rev. 1981, 33, 155–188. [Google Scholar]

- Aoki, K.R. Pharmacology and immunology of botulinum toxin type A. Clin. Dermatol. 2003, 21, 476–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellizzari, R.; Rossetto, O.; Schiavo, G.; Montecucco, C. Tetanus and botulinum neurotoxins: Mechanism of action and therapeutic uses. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 1999, 354, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schiavo, G.; Matteoli, M.; Montecucco, C. Neurotoxins affecting neuroexocytosis. Physiol. Rev. 2000, 80, 717–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacy, D.B.; Tepp, W.; Cohen, A.C.; DasGupta, B.R.; Stevens, R.C. Crystal structure of botulinum neurotoxin type A and implications for toxicity. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1998, 5, 898–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koriazova, L.K.; Montal, M. Translocation of botulinum neurotoxin light chain protease through the heavy chain channel. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2003, 10, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizo, J.; Südhof, T.C. Snares and Munc18 in synaptic vesicle fusion. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002, 3, 641–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pingel, J.; Nielsen, M.S.; Lauridsen, T.; Rix, K.; Bech, M.; Alkjaer, T.; Andersen, I.T.; Nielsen, J.B.; Feidenhansl, R. Injection of high dose botulinum-toxin A leads to impaired skeletal muscle function and damage of the fibrilar and non-fibrilar structures. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 14746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nigam, P.K.; Nigam, A. Botulinum toxin. Indian J. Dermatol. 2010, 55, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Paiva, A.; Meunier, F.A.; Molgó, J.; Aoki, K.R.; Dolly, J.O. Functional repair of motor endplates after botulinum neurotoxin type A poisoning: Biphasic switch of synaptic activity between nerve sprouts and their parent terminals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 3200–3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holland, R.L.; Brown, M.C. Nerve growth in botulinum toxin poisoned muscles. Neuroscience 1981, 6, 1167–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, W.G.; Brown, M.C. The distribution of nodal sprouts in a paralysed or partly denervated mouse muscle. Neuroscience 1982, 7, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamphlett, R. Early terminal and nodal sprouting of motor axons after botulinum toxin. J. Neurol. Sci. 1989, 92, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.M.; Kumar, V.R.; Arper, D.L.; Kruger, E.; Bilir, S.P.; Richardson, J.S. Cost savings associated with timely treatment of botulism with botulism antitoxin heptavalent product. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0224700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Arnon, S.S.; Schechter, R.; Inglesby, T.V.; Henderson, D.A.; Bartlett, J.G.; Ascher, M.S.; Eitzen, E.; Fine, A.D.; Hauer, J.; Layton, M.; et al. Working Group on Civilian Biodefense. Botulinum toxin as a biological weapon: Medical and public health management. JAMA 2001, 285, 1059–1070, Erratum in JAMA 2001, 285, 2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalk, C.H.; Benstead, T.J.; Pound, J.D.; Keezer, M.R. Medical treatment for botulism. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 4, CD008123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Olson, M.E.; Eubanks, L.M.; Janda, K.D. Strategies to Counteract Botulinum Neurotoxin A: Nature’s Deadliest Biomolecule. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 2322–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Version 2. BMJ 2009, 339, b2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vandenbroucke, J.P.; von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Pocock, S.J.; Poole, C.; Schlesselman, J.J.; Egger, M. STROBE Initiative. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and elaboration. Int. J. Surg. 2014, 12, 1500–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Borodic, G.E.; Ferrante, R. Effects of repeated botulinum toxin injections on orbicularis oculi muscle. J Clin Neuroophthalmol. 1992, 12, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamjian, J.A.; Walker, F.O. Serial neurophysiological studies of intramuscular botulinum-A toxin in humans. Muscle Nerve. 1994, 17, 1385–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansved, T.; Odergren, T.; Borg, K. Muscle fiber atrophy in leg muscles after botulinum toxin type A treatment of cervical dystonia. Neurology 1997, 48, 1440–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanucci, E.; Masala, S.; Sodani, G.; Varrucciu, V.; Romagnoli, A.; Squillaci, E.; Simonetti, G. CT-guided injection of botulinic toxin for percutaneous therapy of piriformis muscle syndrome with preliminary MRI results about denervative process. Eur. Radiol. 2001, 11, 2543–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, E.W.; Ahuja, A.T.; Ho, W.S.; King, W.W.; Wong, W.K.; Pang, P.C.; Hui, A.C. A prospective study of the effect of botulinum toxin A on masseteric muscle hypertrophy with ultrasonographic and electromyographic measurement. Br. J. Plast Surg. 2001, 54, 197–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.H.; Chung, J.H.; Park, R.H.; Park, J.B. The use of botulinum toxin type A in aesthetic mandibular contouring. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2005, 115, 919–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Ma, J.; Lee, C.; Smith, B.P.; Smith, T.L.; Tan, K.H.; Koman, L.A. How muscles recover from paresis and atrophy after intramuscular injection of botulinum toxin A: Study in juvenile rats. J. Orthop. Res. 2006, 24, 1128–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, B.J.; Silbert, P.L.; Dunne, J.W.; Song, S.; Singer, K.P. An open label pilot investigation of the efficacy of Botulinum toxin type A [Dysport] injection in the rehabilitation of chronic anterior knee pain. Disabil. Rehabil. 2006, 28, 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, W.; Longino, D. The role of muscles in joint degeneration and osteoarthritis. J. Biomech. 2007, 40 (Suppl. 1), S54–S63, Erratum in J. Biomech. 2008, 41, 2332–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frick, C.G.; Richtsfeld, M.; Sahani, N.D.; Kaneki, M.; Blobner, M.; Martyn, J.A. Long-term effects of botulinum toxin on neuromuscular function. Anesthesiology 2007, 106, 1139–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kwon, T.G.; Park, H.S.; Lee, S.H.; Park, I.S.; An, C.H. Influence of unilateral masseter muscle atrophy on craniofacial morphology in growing rabbits. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2007, 65, 1530–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.J.; Kim, S.G.; Kim, Y.J.; Han, J.Y.; Choi, S.H.; Lee, S.I. Electrophysiologic change and facial contour following botulinum toxin A injection in square faces. Plast Reconstr. Surg. 2007, 120, 769–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroeder, A.S.; Ertl-Wagner, B.; Britsch, S.; Schröder, J.M.; Nikolin, S.; Weis, J.; Müller-Felber, W.; Koerte, I.; Stehr, M.; Berweck, S.; et al. Muscle biopsy substantiates long-term MRI alterations one year after a single dose of botulinum toxin injected into the lateral gastrocnemius muscle of healthy volunteers. Mov. Disord. 2009, 24, 1494–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babuccu, B.; Babuccu, O.; Yurdakan, G.; Ankarali, H. The effect of the Botulinum toxin-A on craniofacial development: An experimental study. Ann. Plast Surg. 2009, 63, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, F.C.; Hsieh, M.S.; Chou, C.M. Comparison between neurectomy and botulinum toxin A injection for denervated skeletal muscle. J. Neurotrauma. 2010, 27, 1509–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortuna, R.; Vaz, M.A.; Youssef, A.R.; Longino, D.; Herzog, W. Changes in contractile properties of muscles receiving repeat injections of botulinum toxin (Botox). J. Biomech. 2011, 44, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortuna, R.; Horisberger, M.; Vaz, M.A.; Van der Marel, R.; Herzog, W. The effects of electrical stimulation exercise on muscles injected with botulinum toxin type-A (botox). J. Biomech. 2013, 46, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Campenhout, A.; Verhaegen, A.; Pans, S.; Molenaers, G. Botulinum toxin type A injections in the psoas muscle of children with cerebral palsy: Muscle atrophy after motor end plate-targeted injections. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2013, 34, 1052–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koerte, I.K.; Schroeder, A.S.; Fietzek, U.M.; Borggraefe, I.; Kerscher, M.; Berweck, S.; Reiser, M.; Ertl-Wagner, B.; Heinen, F. Muscle atrophy beyond the clinical effect after a single dose of OnabotulinumtoxinA injected in the procerus muscle: A study with magnetic resonance imaging. Dermatol. Surg. 2013, 39, 761–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortuna, R.; Horisberger, M.; Vaz, M.A.; Herzog, W. Do skeletal muscle properties recover following repeat onabotulinum toxin A injections? J. Biomech. 2013, 46, 2426–2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukund, K.; Mathewson, M.; Minamoto, V.; Ward, S.R.; Subramaniam, S.; Lieber, R.L. Systems analysis of transcriptional data provides insights into muscle’s biological response to botulinum toxin. Muscle Nerve. 2014, 50, 744–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortuna, R.; Vaz, M.A.; Sawatsky, A.; Hart, D.A.; Herzog, W. A clinically relevant BTX-A injection protocol leads to persistent weakness, contractile material loss, and an altered mRNA expression phenotype in rabbit quadriceps muscles. J. Biomech. 2015, 48, 1700–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Caron, G.; Marqueste, T.; Decherchi, P. Long-Term Effects of Botulinum Toxin Complex Type A Injection on Mechano- and Metabo-Sensitive Afferent Fibers Originating from Gastrocnemius Muscle. PLoS ONE. 2015, 10, e0140439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Valentine, J.; Stannage, K.; Fabian, V.; Ellis, K.; Reid, S.; Pitcher, C.; Elliott, C. Muscle histopathology in children with spastic cerebral palsy receiving botulinum toxin type A. Muscle Nerve 2016, 53, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Allende, A.; Martin, F.; Fraser, C.L. Histopathological changes of fibrosis in human extra-ocular muscle caused by botulinum toxin A. J. AAPOS 2016, 20, 544–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocaelli, H.; Yaltirik, M.; Ayhan, M.; Aktar, F.; Atalay, B.; Yalcin, S. Ultrastructural evaluation of intramuscular applied botulinum toxin type A in striated muscles of rats. Hippokratia 2016, 20, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hart, D.A.; Fortuna, R.; Herzog, W. Messenger RNA profiling of rabbit quadriceps femoris after repeat injections of botulinum toxin: Evidence for a dynamic pattern without further structural alterations. Muscle Nerve 2018, 57, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.K.; Lee, Y.; Hong, J.J.; Yeo, H.G.; Seo, J.; Jeon, C.Y.; Jeong, K.J.; Jin, Y.B.; Kang, P.; Lee, S.; et al. In vivo study of paraspinal muscle weakness using botulinum toxin in one primate model. Clin. Biomech. 2018, 53, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, C.; Elliott, C.; Valentine, J.; Stannage, K.; Bear, N.; Donnelly, C.J.; Shipman, P.; Reid, S. Muscle volume alterations after first botulinum neurotoxin A treatment in children with cerebral palsy: A 6-month prospective cohort study. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2018, 60, 1165–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, W.; Salles, A.G.; Faria, J.C.M.; Nepomuceno, A.C.; Salomone, R.; Krunn, P.; Gemperli, R. Contralateral Botulinum Toxin Improved Functional Recovery after Tibial Nerve Repair in Rats. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2018, 142, 1511–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. The International Study on Aesthetic/Cosmetic Procedures Performed in 2018. International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. 2018. Available online: https://www.isaps.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/ISAPS-Global-Survey-Results-2018-new.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Hastings-Ison, T.; Graham, H.K. Atrophy and hypertrophy following injections of botulinum toxin in children with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2013, 55, 778–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manríquez, J.J.; Cataldo, K.; Vera-Kellet, C.; Harz-Fresno, I. Wrinkles. BMJ Clin. Evid. 2014, 2014, 1711. [Google Scholar]

- Rohrich, R.J.; Pessa, J.E. The fat compartments of the face: Anatomy and clinical implications for cosmetic surgery. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2007, 119, 2219–2227, discussion 2228–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scott, A.B.; Rosenbaum, A.; Collins, C.C. Pharmacologic weakening of extraocular muscles. Invest. Ophthalmol. 1973, 12, 924–927. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Clark, R.P.; Berris, C.E. Botulinum toxin: A treatment for facial asymmetry caused by facial nerve paralysis. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1989, 84, 353–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carruthers, A.; Carruthers, J. History of the cosmetic use of Botulinum A exotoxin. Dermatol. Surg. 1998, 24, 1168–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salari, M.; Sharma, S.; Jog, M.S. Botulinum Toxin Induced Atrophy: An Uncharted Territory. Toxins 2018, 10, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yiannakopoulou, E. Serious and long-term adverse events associated with the therapeutic and cosmetic use of botulinum toxin. Pharmacology 2015, 95, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, P.D.; Couto, R.A.; Isakov, R.; Yoo, D.B.; Azizzadeh, B.; Guyuron, B.; Zins, J.E. Botulinum Toxin and Muscle Atrophy: A Wanted or Unwanted Effect. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2016, 36, 482–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khonsary, S.A. Guyton and Hall: Textbook of Medical Physiology. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2017, 8, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirazzini, M.; Rossetto, O.; Eleopra, R.; Montecucco, C. Botulinum Neurotoxins: Biology, Pharmacology, and Toxicology. Pharmacol. Rev. 2017, 69, 200–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosales, R.L.; Bigalke, H.; Dressler, D. Pharmacology of botulinum toxin: Differences between type A preparations. Eur. J. Neurol. 2006, 13, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett, A. Animal studies with botulinum toxins may produce misleading results. Anesth. Analg. 2012, 115, 736–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damiano, D.L.; Moreau, N. Muscle thickness reflects activity in CP but how well does it represent strength? Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2008, 50, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boggio, R.F. Dynamic Model of Applied Facial Anatomy with Emphasis on Teaching of Botulinum Toxin A. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2017, 5, e1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).