1. Introduction

Malnutrition, hunger, and food insecurity remain among the most significant global challenges, affecting billions of people worldwide [

1,

2,

3]. Despite decades of progress, the issue persists and is now gradually worsening. According to the FAO, as of 2022, between 691 and 783 million people are undernourished, representing approximately 10% of the global population. Asia, Africa, and Latin America have experienced a rising trend in severe food insecurity in recent years. These alarming figures reflect a troubling reversal of long-term improvements in food security [

4]. Malnutrition not only affects physical health but also undermines the immune system, socio-economic equity, and overall development [

5,

6]. The global food insecurity crisis requires urgent and coordinated efforts to address its root causes. International and regional initiatives must prioritise building resilient food systems, enhancing access to nutritious food, and addressing the socio-economic disparities driving hunger in these vulnerable regions. Without decisive action, the number of people facing chronic hunger is likely to continue rising, further undermining global development goals.

Mountain populations face significant challenges, including stress, hazards, and poverty, contributing to heightened food and nutrition insecurity [

7]. In 2024, all eight countries in the Himalayan Mountain Region (HMR), excluding China, were classified as having serious to moderate hunger levels on the Global Hunger Index (GHI). The calculation of GHI includes four components, namely, undernourishment, child stunting, child wasting and child mortality [

8]. An adequate supply of food with sufficient content of nutrients (macronutrients and micronutrients) is the only alternative to improve the existing level of the index (GHI). Alarmingly, India’s standing among undernourished nations has shown little improvement over the past five years [

9,

10]. Malnutrition remains a critical issue, particularly in rural India, where it is more prevalent compared to urban areas [

11]. Its intergenerational consequences are severe, as highlighted by Wells et al. [

6], who emphasised the erosion of socio-economic equity and overall development caused by malnutrition. Currently, 35.70% of Indian children under five years are underweight, 38.40% are stunted, and 21.00% are wasted [

12]. In Arunachal Pradesh, data from 2015–2016 reveal that nearly one-third of children under five years are stunted, 17.00% are wasted, 19.00% are underweight, and 5.00% are overweight [

13]. Vulnerable populations, including children and pregnant women in low-income regions, bear the brunt of these impacts, amplifying existing inequalities and intergenerational cycles of malnutrition. Addressing malnutrition in the face of climate change requires a multi-faceted approach, integrating sustainable agricultural practices, climate-resilient food systems, and targeted nutrition programs to build resilience in affected communities. Although there have been improvements since previous surveys, child malnutrition remains a pressing issue both in the region and across India. Multiple factors contribute to malnutrition, including inadequate access to nutritious food. Tackling this issue requires a holistic approach involving targeted interventions and redefined goals within nutrition programs to meet the diverse needs of affected populations [

14].

Recognising the vital role of vegetables in ensuring food and nutrition security is increasingly important [

15]. Insufficient consumption of fruits and vegetables contributes to malnutrition in developing regions, leading to deficiencies in essential vitamins, minerals, and dietary fiber [

16]. For low-income populations in countries such as Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, and Zimbabwe, purchasing the recommended servings of fruits and vegetables can account for half of their daily income [

17]. Dark green leafy vegetables are particularly costly, being 5–9 times more expensive as a calorie source than staple cereals in Asia [

18]. Homestead gardening, which is a production sub-system designed to produce items primarily for household consumption [

19] offers a sustainable solution, enhancing food security and combating malnutrition by providing diverse, nutrient-rich diets at low costs [

20,

21,

22]. This integrated system of cultivating crops and raising livestock supports families with essential food items and resources like organic manure and draught power while improving their nutritional status and quality of life [

23,

24,

25]. As a long-standing component of food systems in developing countries, homestead gardening plays a critical role in regions such as Arunachal Pradesh under the HMR [

26,

27,

28].

One of the primary reasons for poor nutrition is the lack of knowledge and perception (K&P) about nutrition among people. In this study, awareness means knowing about the existence of an innovation, idea, concept, practice and object, and knowledge means the ability to recall with a preliminary understanding about an innovation, idea, concept, practice, and object, whereas perception denotes the ability of perceiving, understanding, and interpreting an innovation, idea, concept, practice, and object. This issue persists globally, regardless of whether food supplies are abundant or scarce. Undernutrition and deficiencies in vitamins and minerals coexist worldwide. Achieving individuals’ nutritional well-being requires an ample supply of high-quality food and a comprehensive understanding of a healthy diet [

29]. Assessing nutritional knowledge is crucial in nutrition research, as it enables the development of effective policies and programs that promote healthier eating habits [

30]. Consequently, this contributes to enhancing the overall knowledge of nutrition within communities.

According to the existing literature, there is a lack of suitable tools or methodologies for assessing and quantifying the level of K&P among farmers, homestead gardeners, and poultry keepers regarding nutrition, nutrition security, and the correlation between specific livelihood activities and nutrition security. In developing countries, agriculture and allied activities are primarily concentrated in rural areas, playing a vital role in ensuring food and nutrition security at the national level. However, despite this, malnutrition is disproportionately higher in rural areas (with stunting exceeding 50.00% and wasting at 21.00%) compared to urban areas (with stunting at 40.00% and wasting at 17.00%) [

31].

Therefore, growers and farmers must have a deep understanding of the nutritional availability within their farm products and the diverse nutritional needs required for maintaining health. Which will support in addressing the complex relationship between ensuring food and nutrition security at a national level and combating malnutrition. It is assumed that addressing rural and national malnutrition can be more effectively achieved by equipping growers with K&P of nutrition. To this end, a unique research framework has been developed and applied to assess homestead gardeners’ nutrition K&P, which can also be adopted to gauge the nutrition K&P of other crop growers and livestock keepers in any place/country. Further, we have extensively analysed the nutrition security policies and malnutrition eradication initiatives implemented by the Government of India since independence in 1947. Our research outcomes and policy analysis will be pivotal in formulating tailored policymaking for all countries (and their respective states) to address malnutrition and achieve comprehensive nutrition security effectively. The present study has the following objectives: (i) to delve into understanding how homestead gardeners perceive and understand nutrition, as well as how they contribute to ensuring nutrition security, (ii) to explore the correlation between social and economic attributes of individuals and their understanding and perspective as homestead gardeners, and (iii) to review/analyse the government of India’s policies for the up-scaling of K&P of individuals on nutrition security to address the nutritional needs of the population. The following null hypothesis was formulated for the testing: H01 = respondents’ socio-economic characteristics have no association with their nutrition knowledge and perception. Accordingly, relationship studies (correlation and regression analysis) were adopted to evaluate and test the hypothesis.

This study offers fresh and impactful insights to the existing body of literature, addressing important gaps, such as, socio-economic profile and nutrition security of rural and mountain people, how to address and achieve the nutrition security of homestead gardeners and farmers through the up scaling of knowledge and perception of growers about nutrition, sources and importance of nutrition for human health. Further, this study is going to enrich the policy mechanism to achieve nutrition security through the individual and societal contributions in the augmentation of knowledge and perception of individuals and communities. Homestead garden may play a significant role in achieving nutritional security in rural and mountain areas.

For instance, the study developed a new scale to assess the K&P of homestead gardeners regarding nutrition, which was tailored for evaluating macronutrients, micronutrients, vitamins, and minerals. This is not extensively covered in existing tools. The study focused on homestead gardeners in the Himalayan Mountain Region. This region has a significantly underrepresented population, which provided insights specific to this geographically challenging and socio-economically diverse area. These factors make the study a novel contribution to both academic research and practical policymaking in the domain. This paper is structured as follows:

Section 1 introduces the research, while

Section 2 outlines the conceptual framework and methodology employed.

Section 3 presents the results, discussion, and an analysis of India’s nutrition policy. The paper concludes with final remarks and recommendations in the last section.

2. Methodology

A conceptual framework and knowledge and perception index (KPI) have been developed to complete the study and rigorously assess the respondents’ K&P levels. A clear and direct relationship has been established between the socio-economic variables and the respondents’ K&P levels. The study’s conceptual framework and methodology are poised to be replicated in all the countries under the HMR and other developing and underdeveloped nations. Additionally, in-depth policy analysis on nutrition security within the country can serve as a valuable resource for nutrition policymakers globally, aiding them in formulating effective policy documents that reflect the community’s nutritional perception and the prevailing policy landscape. The following section provides a detailed description of the study area, outlines the conceptual framework used in the study, and discusses the research methods employed to conduct the research.

2.1. Profile of the Study Area

The Himalayan Mountain Region (HMR) is extended from 15.95° to 39.31° N latitude and 60.85° to 105.04° E longitude across eight South Asian countries: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Myanmar, Nepal, and Pakistan [

32,

33]. It is extended around 3000 km in length and 250–300 km in width, with a geographical area of around 7,550,000 km

2 [

34]. Around 70% of the people continue agriculture-based livelihoods [

35,

36] and the maximum number of people are maintaining homestead gardens. Out of the eight countries, India borders all the other countries. Accordingly, India and one of its states (Arunachal Pradesh) under the HMR were selected for the present study.

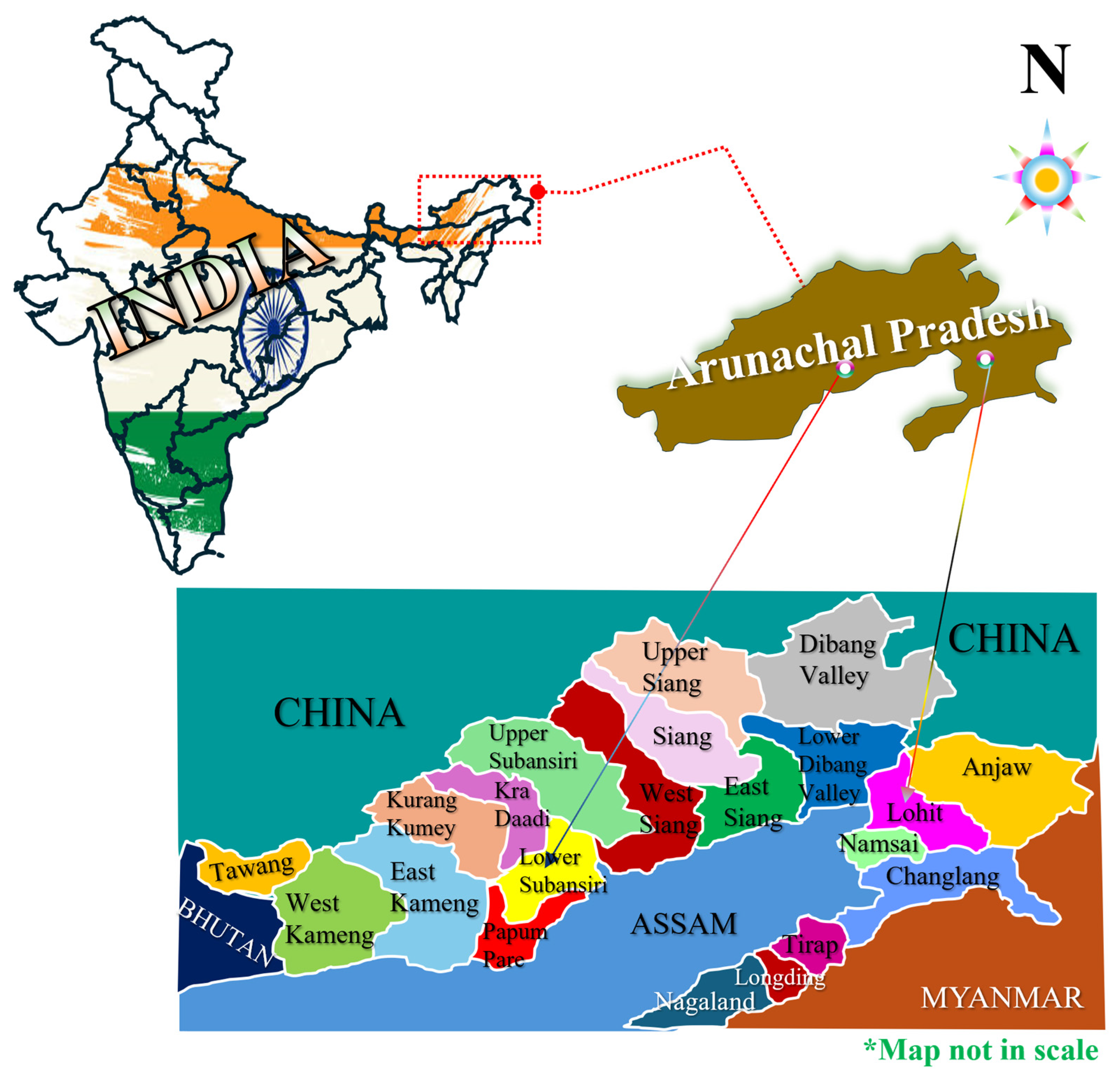

The study took place in Arunachal Pradesh, India, located between 26.28° N and 29.30° N latitude and 91.20° E and 97.30° E longitude. It shares a border with three HMR countries (China, Myanmar, and Bhutan). Hence, the state has been deliberately chosen for the study. A significant portion (29.00%) of the children under the age of five years are stunted in growth [

13]. The study focused on the Lower Subansiri district, located at 27.61° N latitude and 93.50° E longitude, and Lohit district, situated at 27.84° N latitude and 96.19° E longitude (

Figure 1). These two districts were chosen due to their significant prevalence of malnourished children under five years of age, as indicated by three anthropometric indices of nutritional status: height-for-age, weight-for-height, and weight-for-age [

13]. Furthermore, in this study, six villages were purposively selected from two blocks, with one block chosen from each district.

2.2. Conceptual Framework

Homestead gardens (HGs) offer a sustainable solution to malnutrition, undernutrition, and micronutrient deficiencies by providing the opportunity to grow diverse and nutrient-rich crops right at home [

27,

28]. In this study, we adopt Ninez’s definition of an HG [

18] as a production sub-system designed to produce items primarily for household consumption. We acknowledged the potential for improving the quality of life for farmers by bolstering local food and nutrition security at a modest cost. One of the leading causes of malnutrition in the population is an insufficient understanding of nutrition and its perception, and addressing this understanding gap will help to reduce malnutrition [

29] (please consult the graphical abstract for a schematic view of the conceptual framework).

Based on the literature review, it appears that there are currently no appropriate tools or methods available to measure and quantify the K&P level of the homestead gardeners, fruit growers, crop growers, and livestock keepers regarding nutrition and nutrition security, as well as the interaction between the specific aspects of livelihood components (such as homestead gardening, fruit growing, crop growing, and livestock keeping) and nutrition security. Most existing tools and scales focus on nutrients and their impact on human health. In the HMR’s countries, agriculture and related activities are mainly concentrated in rural areas, where all food items are produced to ensure food and nutrition security. However, malnutrition is more severe in rural areas (stunting: >50.00%; wasting: 21.00%) than in urban areas (stunting: 40.00% and wasting: 17.00%) [

13,

31]. This poses a paradox: those responsible for ensuring the country’s food and nutrition security suffer from malnutrition and hidden hunger.

Among various reasons, a lack of nutrition K&P is the primary reason for this situation [

29]. This is further exacerbated by lower literacy rates in rural (66.77%) compared to urban (84.11%) areas [

37]. Regarding the previously mentioned paradox of simultaneously being responsible for ensuring a nation’s food and nutrition security while also contending with malnutrition, we hypothesised that addressing rural and national malnutrition could be straightforward if growers and farmers possessed K&P of the nutritional availability in their farms and the specific nutrient requirements for good health. As a result, we have formulated a research concept and designed a research framework (please consult the graphical abstract) to assess the K&P of homestead gardeners.

The framework (as illustrated in the graphical abstract) outlines the method for assessing K&P levels of homestead gardeners on nutrition and nutrition security, as well as the perceived role of HGs in nutrition security through its components. The study aims to support and influence policy decisions to address malnutrition and achieve nutrition security at both local and national levels.

2.3. Respondents

We intentionally selected skilled and experienced homestead gardeners (mean experience: 14.12 years) hailing from specific districts of Arunachal Pradesh, India, to serve as key informants. The respondents demonstrated a high level of proficiency in establishing and caring for HGs. Notably, these individuals were meticulously chosen based on their outstanding maintenance of HGs during the data collection period. To ensure diversity, 120 (60 from each district) homestead gardeners were purposively chosen.

2.4. Nutrition K&P Assessment

After a thorough review, 134 specific items/statements were carefully selected and incorporated into the preliminary interview schedule. These items covered three main dimensions: macronutrients, micronutrients (vitamins and minerals), and nutrient contents in food items, aiming to assess the K&P of the respondents. Each item/statement/question was evaluated on a three-point continuum: highly relevant, relevant, and not relevant. The draft interview schedule, including all the items, was then sent to 20 judges for their assessment. These judges included Agricultural University professors, scientists, and faculties, each holding a Ph.D. in agricultural and allied disciplines. Subsequently, the judges’ evaluations were used to finalise the items, with all items judged as highly relevant or relevant being retained. In contrast, those receiving a judgment that was not relevant were excluded from the final schedule.

Following the assessment by the judges, a set of 134 items/statements/questions were retained to evaluate the K&P of individuals regarding nutrition. Additionally, a comprehensive evaluation was conducted, encompassing 35 aspects, including macronutrients, micronutrients, and the availability of nutrients from various commonly consumed food sources. Each aspect was thoroughly addressed, with a minimum of three associated issues. For analysis, the items/statements were assigned a score of 1 or 0 for “yes/aware” or “no/not aware,” respectively. This approach resulted in formulating a knowledge and perception index (KPI) to quantify the respondents’ comprehension of nutrition. With 134 items considered, the potential score ranged from 0 to 134. The resulting index value provided valuable insight into each respondent’s understanding and perception of nutrition’s significance in human health. The methodology utilised to establish the KPI is both intricate and thorough, as follows:

2.5. Policy Review/Analysis

Policy review/analysis involves using various methods of inquiry to produce information-based analysis aimed at addressing policy inadequacies or improving policymaking. It is also an initiative used to contribute remedial measures to protect or rectify flawed policies. Policy analysis as a process of scientific evaluation of the impact of past public policies [

38]. Further, policy analysis provides methods and tools for assessing whether a policy is appropriate and suitable [

39]. In this study, we employed retrospective policy review/analysis to address malnutrition and achieve nutrition security in India. We considered all the major policy initiatives by the Government of India since the country’s independence in 1947, focusing on analysing K&P enhancement interventions in policy initiatives to encourage participation from every citizen in the eradication of malnutrition and achieve nutrition security.

2.6. Data Collection

Both primary and secondary sources were utilised. The primary data were gathered through personal interviews using a structured interview schedule to obtain information from the respondents about their understanding and perception of nutrition and its role in human health. The secondary data were obtained from various sources, such as books, journals, magazines, websites, and other relevant materials.

2.7. Statistical Tools and Analysis

This study used a statistical analysis framework to examine the K&P of homestead gardeners regarding nutrition. Initially, Cronbach’s alpha test was adopted to assess the reliability and internal consistency of data collection tools. Accordingly, three separate Cronbach’s alpha tests were adopted for the three tools. The Cronbach’s alpha values were 0.929, 0.972 and 0.896. A high Cronbach’s alpha value (>0.80) indicates greater reliability and internal consistency of the tool. After data collection, all information was cleaned, scored, tabulated, and analysed using a combination of descriptive and inferential statistical tools. Descriptive statistics, including frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation, were utilised to summarise respondents’ K&P levels across different dimensions, such as macronutrients, micronutrients, and nutrient content in food items. Correlation analysis was conducted to identify the relationships between socio-economic variables (e.g., education, media exposure, income) and respondents’ K&P scores. Regression analysis further explored the impact of these socio-economic factors on KPI. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 16, a robust software package widely recognised for its capabilities in managing and analysing complex data sets. For hypothesis testing linear regression analysis was used to evaluate relationships among variables with emphasis on R2 and p-value of the respective variables of the regression model. Careful attention was paid to ensure data integrity throughout the process, including the appropriate handling of missing values and assumption testing.

4. Conclusions

It is evident that huge inadequacies in the nutrition awareness and importance of nutrition for the proper mental and physical health of human beings are persisting in the rural and mountain communities. Further, policy-level deficiency with reference to nutrition awareness creation to achieve self-nutrition security by individual citizens is also recognized. The lack of K&P about nutrition and its significance for human health has several implications for addressing malnutrition. K&P about nutrition is crucial for implementing nutrition-sensitive policies in the country. The limited available literature emphasises the importance of raising public K&P about nutrition security in developing countries under the HMR. It is obvious that the public sector of developing countries is unable to bring nutrition security for the vast population due to various institutional and organisational constraints; it is difficult for the government to reach or directly serve all the citizens. Therefore, the policy process of the developing countries under HMRs may take the initiative to ensure that the self, family, and community level contribution in nutrition security drive through the creation of K&P of the community on nutrition issues.

Therefore, all the concerned departments may take the initiative for the analysis of existing policies and to explore the opportunity to incorporate different activities on the K&P creation of citizens on nutrition security, or may propose new policies. All the departments involved in welfare, health and family welfare, and food and nutrition security programmes may augment the capacity of individuals to achieve self and family nutrition security instead of offering items or subsidised inputs. It is crucial for the Department of Health and Family Welfare to take the initiative to bring the individual’s and family’s nutrition security by involving all citizens. Capacity development of their extension workers is urgently needed to up-scale the K&P of the community and mothers of young children. Basic nutrition education should be incorporated into the primary, higher secondary, and college syllabi. The undergraduate (UG) and postgraduate (PG) syllabus of agriculture, horticulture, and livestock education may be restructured, with an emphasis on mechanisms to accelerate and achieve nutrition security. The Department of Agriculture, The Department of Horticulture, and other allied departments at national and state levels are responsible for promoting the cultivation and consumption of nutrition-rich crops. Accordingly, they may analyse their functionaries’ competency for nutrition extension, and the required capacity strengthening of functionaries needs to be initiated. Also, there is a need to analyse existing policies and modify them, emphasising up-scaling the K&P of farmers, female farmers, and villagers on nutrition security, nutrition-rich crops, and the importance of nutrition to human health. Further, all the concerned departments may emphasise a group approach through women self-help groups (SHGs), male SHGs, Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs), and growers’ associations, which accelerate the achievement of the target of nutrition security.

However, based on the research findings, it can be concluded that a multi-faced initiative is needed to involve all stakeholders, along with a special emphasis on up-scaling the awareness and perception of individual citizens, which will support addressing the community’s malnutrition. Despite several positive outcomes from the study, it has some limitations, including that it is based on perceived data, which relies on the recall and perception abilities of respondents, and the possibility of bias and error exists. Furthermore, the findings are based on a small sample, which may limit the generalisability of the study outcomes. Accordingly, to overcome the limitations and to augment the robustness of the study outcomes, we are continuing a similar type of research in different areas with a bigger sample size. Similar types of study initiatives from other researchers may accelerate the achievement of nobility in the genre of research. For instance, a study on marginal and small farmers’ ability to address nutrition security through their farming components. It may also be related to the level of nutrition security of different categories of farmers through their farming. Also, assessing the influence of socio-economic factors on the adoption of nutrition-rich farming components in their farming. Or, the influence of socio-economic factors and the degree of achieving nutritional security.