Abstract

This systematic review with metanalysis evaluated and analyzed the beneficial effects of certain plants food in type 2 diabetes (T2D) when consumed alone or in combination with chitosan. The main objective of the paper was to examine the relation of chitosan nanogel and mixed food plant (MFP) to control T2D. The databases included Medline, Scopus, PubMed, as well as Cochrane available between the month of January 1990 to January 2021. The eligibility criteria for selecting studies were case-controlled studies that included unripe plantain, bitter yam, okra, and chitosan either used-alone or in combination with non-specified food plants (NSFP). Two-fold autonomous critics retrieved the information required and evaluated the risk of bias of involved studies. Random-effect meta-analyses on blood glucose controls, were performed. Results of 18 studies included: seven that examined unripe plantains, one bitter yam, two okras, and eight chitosan, found regarding the decrease in blood glucose level. Meta-analysis of the results found a large proportion of I2 values for all studies (98%), meaning heterogeneity. As a consequence, the combined effect sizes were not useful. Instead, prediction interval (PI) was used (mean difference 4.4 mg/dL, 95% PI −6.65 to 15.50 and mean difference 3.4 mg/dL, 95% PI −23.65 to 30.50) rather than the estimate of its confidence interval (CI). These studies were at 50% high risk of bias and 50% low risk of bias and there was judged to be an unclear risk of bias due to the insufficient information from the included study protocol (moderately low). The intervention lasted between three and 84 days, indicating potency and effectiveness of the intervention at both short and long durations. Due to the moderately low quality of the studies, the findings were cautiously interpreted. In conclusion, the current evidence available from the study does support the relation of chitosan with mixed unripe plantain, bitter yam and okra for the management of T2D. Further high-quality case-controlled animal studies are required to substantiate if indeed chitosan nanogel should be cross-linked with the specified food plant (SFP) for the management T2D.

1. Introduction

Hyperglycemia that leads to T2D appears to represent a persistent set of life-sustaining chemical conditions which is described by elevated blood sugar which manifests well as the inadequate and ineffective release of pancreatic hormone and affects a set of life-sustaining chemicals, such as glucose amino acids and fatty acids [1]. Data show that in 2015 more than 400 million adults globally were affected by this condition. These people were predominantly among the economically disadvantaged population, and T2D is projected to be the seventh leading cause of death by 2030 [1]. T2D in contrast to type 1 diabetes (T1D) does not completely rely on insulin. T2D is a metabolic condition largely described for its role in licking the cell membrane, low release of the pancreatic hormone-insulin, as well as the upsurge of blood sugar upon directly ingesting food [1,2].

In third world countries and globally, the predominance of T2D is ascribed to the modifications in lifestyle, including the transition from home prepared food high in phytonutrients (i.e., Polyphenols) to a more Westernized type of food which might be considered less nutritionally sound [3]. Such lifestyle changes have resulted in the increase of the prevalence of prolonged and deteriorating diseases.

The therapeutic benefits of customary foods have assumed significant place lately as a result of benefits connected to their phytonutrients [4,5]. Legumes as well as other food plants possess significant benefits in preventing as well as managing prolonged diseases [4]. Table 1 presents the characteristics of the most frequent drugs used for T2D.

Table 1.

Showing characteristics of common antidiabetic drugs used for T2D treatment.

Synthetic medications, e.g., acarbose, viglibose, and miglitol, are alfa-glucosidase inhibitors while others include biguanides, thiazolidinediones, sulphonylureas, and meglitinides, which display discomforting side effects, such as stomach pain, swelling, the release of ammonia gas from digestion, swelling of the stomach caused by dwelling gas, as well as the loss of fluid via the elementary canal [9]. Some of these discomforting symptoms are perhaps triggered by the production of ethanol as a result of the increased presence of bacteria; an end product from non-catabolized carbohydrates in the gastro intestinal (GI) track. Foods from plant sources generally comprise natural antioxidants such as phenolic compounds that can scavenge for ROS also referred to as free radicals [11,12,13,14,15,16,17].

With the use of new oral antidiabetics (OAD), such as gliptines, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analogues, gliflozines were approved for the treatment of T2D, demonstrating improved glycemic control, weight loss, and cardiovascular benefit [7]. The fruit content of plantain (Musa paradisiaca) is considered a major food product in Africa which provides a great source of energy for these people. Plantains are stated as an essential basis for pro-retinoids around continents (Asia, Africa, as well as Latin America).

Musa parasidiaca is rich in fat-soluble retinoids, water soluble B vitamins (thiamin, niacin, riboflavin and pyridoxine), and vitamin C. This food is discovered to be extremely rich in potassium but poor in sodium. Musa parasidiaca is an excellent source for vit A compared to other foods. Fat-soluble vit A (carotenoid) is considered to a safeguard against diabetes, heart disease, and cancer. The fat-soluble vitamin is among the best essential groups of phytonutrients which exhibit a vital role in the nutritious value of the plants. Plantain has been used in Nigeria to decrease blood sugar levels after a carbohydrate (CHO) meal. Plantain fits into the family of flowering plants eaten ripe or unripe using diverse methods of processing techniques, being cooked as well as fried. Additionally, products, such as flour and chips, have been made from plantain [10].

Bitter yam (Dioscorea dumetorum) is a food commonly used in tropical countries. This short (small) tuber fits into Dioscorea family. Collectively, it is referred to as bitter yam trifoliate (three–leaved) yam. It is believed to promote glucose balance for the diabetics and to be a therapeutic remedy for different diseases [18,19] Moreover, in the middle-belt region of Nigeria, the Tiv speaking tribe refers to it as ‘Anube’ used for consumption and medicinal purposes to treat illnesses [19].

Okra is unique as a flowering plant of the mallow family [13]. The okra fruit is eaten as a common plant in several nations (including Nigeria and Cyprus). It is rich in nutrients. Okra is known for its therapeutic importance, particularly in respect to lowering the blood glucose effect. While okra is usually seen as a plant that is beneficial to diabetic patients, a limited number of technical articles have acknowledged the therapeutic function that okra performs. Earlier research of Sabitha showed that okra oil extracts promoted hypoglycemic and low-fat beneficial effects, as well as improved the weight in Streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats. Having a better anti oxidation capability, okra is known to reduce the oxidation of lipids, as well as raise the amount of Superoide Dismutase (SOD), Chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT), as well as Glutathione (GSH). It is worth mentioning that decreased levels of GSH were found in the diabetic rats [9].

A useful food can be defined as food which delivers both nutritional and physiological supports to organisms or decreases the possibility of protracted ailments [16]. Okra fruit [17] has previously been shown to establish lower blood sugar as well as lower lipid actions, becoming a versatile and remarkable substitute to control hyperglycemia.

Nanoparticle production procedures can be easily performed as well as valid amidst wide variable medications. In these systems of delivering medication, polymeric nanoparticles have increased their significance, being eco-friendly, biocompatible, and due to their process of preparation much broadly obtainable. Hence, the variety of uses has been increasing to comprise a multiplicity of chemical medication groups and quantity systems [20,21]. Chitosan-based nanoparticles are mostly suitable and less toxic. Chitosan nanogel has been applied to manage production and the spreading of cell in the body, gastrointestinal tract disorders (GIT) disorder, heart disorder, and channeling medication reaching the central nervous system as well as eye impurities. New investigations in nanogel for oral medication (pills, capsules, syrups) have been centered around premises that increased acceptability of nanogel characteristics as well as techniques involving biochemical changes can be useful in specific nanogel therapeutic production as well as distribution structures. Chitosan is considered as one of the key derived products of chitin, made by eliminating the acetate part from chitin. It is a derivative of crustacean shells, such as those from prawns or crabs, and cell walls of organisms such as fungi. Its occurrence is natural as a polysaccharide. As a cation, extremely basic in nature, Chitin is obtained naturally, linked with peptides as well as elements that require detachment before the preparation of chitosan; hence, the methods of acidifying and alkalizing. After purification, acetyl groups are removed from chitin and substituted with amino group to produce chitosan. Nanogel acts in diffusing the openings of tight junctions of epithelium, enhancing the healing of wounds. Chitosan eases both the transport of therapies between and through cells. Chitosan relates with secretions which are negatively charged to bring about complex hydrophobic (water-hating) interrelationships. The acidic content in the primary amino group of nanogel is 6.5, similar to the amount of acetyl free linked amino group. Likewise, this class of acids aids the dissolving of nanogel hydrogen ion systems as well as the incomplete deactivation of primary amines, which could possibly elucidate the reason why chitosan has been described as concentrating acid from neutral to high hydrogen ion concentration [22]. Therefore, the user of nanoparticles is required to cautiously bring together the preferred chemical and physical characteristics of the chitosan, as well as the expected bio-system, using the chitosan treatment technique.

With this scientific evidence regarding the specified plant food (SFP), unripe plantain, bitter yam, and okra so far, the need to use them for the management of T2D has been limited to combining them alone [3,15,23,24,25] or in combination with NSFP [2,5,26,27,28], and those used separately or in combination are not cross-linked with chitosan [7,10,29]. However, where there is a cross-linkage with chitosan, those linkages are not with the SFP [30,31,32,33] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Food plants and chitosan used for their therapeutic and benefit in T2D.

Chitosan acts by diffusing in the openings of tight junctions of epithelium, thereby enhancing the healing of wounds. The selected food plants (MFP-2 unripe plantain, bitter yam, and okra) acting in conjunction release plant insulin, which ultimately benefits diabetics most especially in complicated states of unhealing wounds on the limbs (the arms and legs). No scientific study so far has identified the combining or mixing effects of SFP with chitosan for the management of T2D. Hence, the present systematic and meta-analysis review aims to examine the relation of chitosan nanogel and MFP in T2D. MFP could improve the blood glucose level in association with antidiabetic drugs [10].

2. Methods

The systematic review was conducted in agreement with the 2009 PRISMA statement [43]. The review procedure was recorded with PROSPERO in March 2019 (CRD 42019129124).

2.1. Search Strategy

We searched for journal papers indexed in PubMed, Medline, Scopus, as well as Cochrane that were available from January 1990 to January 2021. The search was limited to T2D alone, generally available in the English language using the search terms: “unripe plantain, bitter yam, okra, chitosan with T2D.’’

2.2. Study Selection, Inclusion as Well as Exclusion Criteria

The review included only studies that examined unripe plantain, bitter yam, okra, and chitosan and their relation to type 2DM. Additionally, no human studies were included. Furthermore, we set a 28-year exploration boundary since therapeutic designs of over 30 years-old may change significantly from natural plant therapy to nutraceutical patterns [15]. Articles were searched and adjudicated. All searched articles were screened by titles and abstracts so as to retrieve useful journals deemed to be eligible. We revised journal paper completely according to standards set. Forms of differences were resolved by consensus-oriented discussion; where there was no resolution, a third party was consulted.

2.3. Information Extraction

Information on features involved in the revisions was taken out individually with the help of two critics. The first critic extracted textual data and the other graphical data (Figures). Authors were contacted where necessary through their e-mails or phone numbers published in their articles for additional or missing data. The data extracted were related to the number of experimental groups in the study design (i.e., the group which was induced and the one receiving intervention). Both species and sex of animal related to the characteristics of the animal model were extracted from the data. The intervention of interest, dosage, timing of dosage, and effectiveness of dosage on the animal’s data was extracted [44]. The primary outcome data support a reduction in hyperglycemia and the unit of measurement was milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL) or millimole per litre (mmol/L). All extracted data were in a continuous data pattern.

2.4. Assessing the Risk Bias

The method of assessing bias risk or assessing quality involved individually assessing risk associated with bias as well as studies included, which were evaluated by two external reviewers, one on text data and the other on graphical data (Figures). Disagreement was resolved by consensus-oriented discussions and where resolution was not reached, a third party was consulted. Studies were evaluated with the Systematic Review Centre for Laboratory Animal Experimentation (SYRCLE) tool for assessing bias risk in animal studies [37]. We regarded individual areas to be at ‘low risk’, ‘unclear risk’ or ‘high risk’ of bias. We generally categorized the bias risk to be ‘low’ when the answer to the signaling questions for that domain was “Yes”, ‘high’ when the answer to the signaling questions was “No”, or as ‘unclear’ when there was insufficient information about that domain (Table 3).

Table 3.

Use of SYRCLE’s tool for assessing risk of bias.

2.5. Strategy for Information Investigation

Effects regarding outcome remained stated with statistical difference at 95%CI, considered from both end standards or modifying the starting point. Through studies, effects on blood glucose level remained constantly obtainable as milligram per deciliter or millimole per liter (mg/dL or mmol/L).

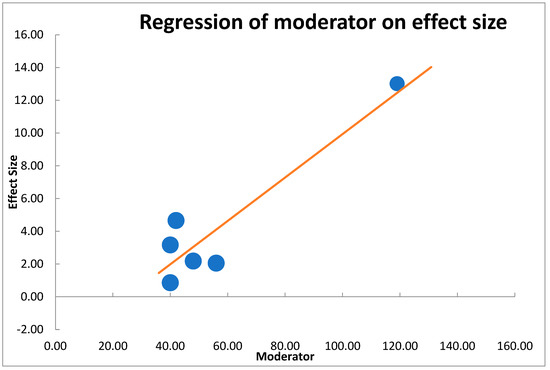

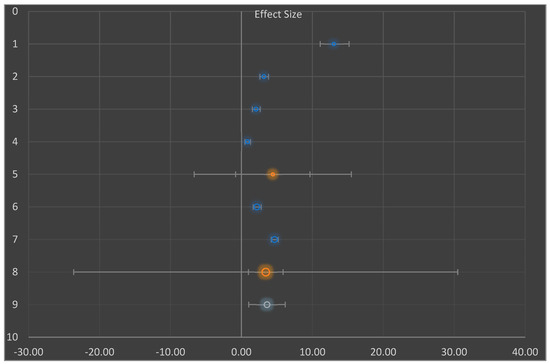

We synthesized approximations in statistical terms, employing prototypical unsystematic effects meta-analysis, founded on the postulation that comparable as well as procedural heterogeneity remained probable to occur as well as have consequence on the outcomes [45,46]. We employed regression on the moderator effect to evaluate differences among studies, as well as considered 95% CI employing moderator analysis (technique of moment estimation) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Moderator analysis showing strong correlation between moderator and effect size for the included studies in meta-analysis.

Table 4.

Subgroup meta-analysis showing effect size, I2 and PI values for AA and BB.

Table 5.

Publication bias analysis confirming effect sizes and I2 values.

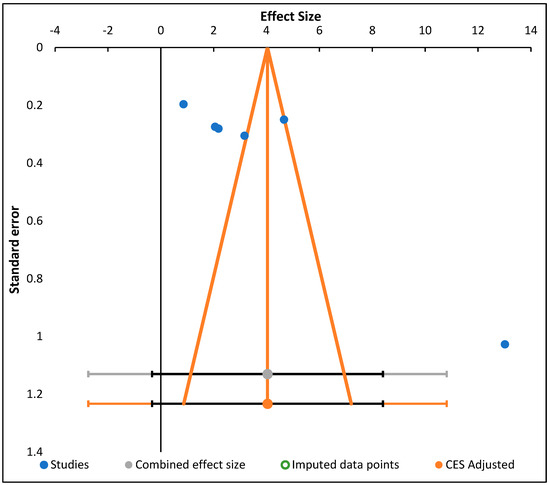

We generated funnel plots (Figure 2) to examine the minor effect-change from studies (affinity about mediation properties projected in lower investigations varies since the ones projected in higher investigations may affect publication preferences, protocol, and comparable differences, among influences). Evaluations were directed employing meta-essentials software intended for meta-analyzing investigations and the result was a change in the statistics among free sets [45].

Figure 2.

Funnel plot showing random effect meta-analysis of mean difference in decrease of blood glucose level (mg/dL) based on diabetic intervention or negative diabetic control.

Hooijmans [37] reported that calculating the instant mark among separate investigations was not a good practice using the SYRCLE’s tool because an instant mark will involve allocating “loads” particular to known areas to tool, which will be problematic when justifying loads allocated. Moreover, loads could vary for every result and for every analysis.

2.6. Patients as Well as General Participation

While the investigation limited the enrollment of human participants, the evaluation was entirely focused on animals only. However, due to the nature of the research question, its result was extrapolated to patients and the public.

3. Outcomes (Results)

3.1. Explored Outcomes

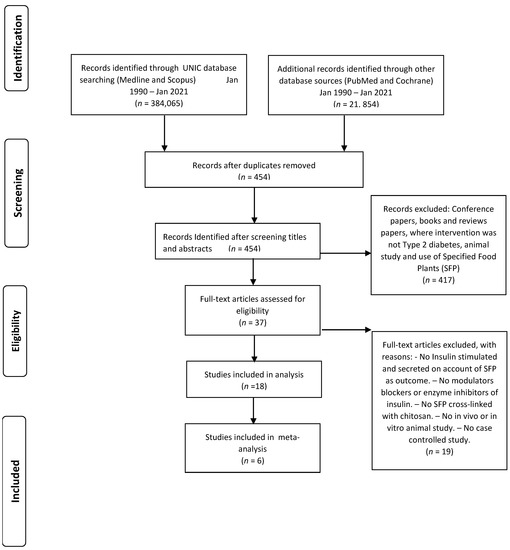

The exploration of four automated records (Medline, Scopus, PubMed, and Cochrane) identified 405,919 collections through 454 journal papers left over once excluding replicas. Out of this number, 417 journal papers were disqualified as the titles and abstract were lacking our criteria, and those journal investigation reports were not of the standards set. Out of 37 selected journal papers, 19 investigational journal report papers were dropped due to not been a precise case investigation, in vivo as well as in vitro animal study, not SFP cross-linked with chitosan, not having modulator blockers or enzyme inhibitors, and not insulin stimulated or secreted on account of SFP as outcome. Thus, 18 studies were identified as eligible for inclusion in the review (Figure 3) [43].

Figure 3.

PRISMA flow diagram of included articles.

3.2. Features of Involved Investigation as Well as Valuation of Intervention: T2D

The features of the involved investigations are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

General characteristics of included studies Baseline characteristics of rats or cell lines.

The invesstigations consisted of seven involving unripe plantain [2,5,11,26,35,36,47], one involving bitter yam [25], two involving okra [15,24], and eight involving chitosan [7,10,29,30,31,32,33,48] respectively. Almost all the included studies were in vivo case-controlled studies which were induced with diabetes using streptozotocin (STZ) and four others with alloxan monohydrate [2,5,30,35]. The major intervention from the studies was Type 2 diabetes with few other interventions in some studies, such as enzyme inhibition, weight change, lipid decrease/insulin resistance, sustained release time, and neuropathy. In all these interventions, SFP were used either in combination with other (NSFP) or used alone without cross-linking them with chitosan. As such, chitosan was used alone to encapsulate either insulin or other active compounds to aid their release over a sustained time. The main outcome measure in all the included studies was a decrease of blood glucose level in the animals.

3.3. The Bias Risk across Investigations

Complete information of the risk bias investigation of animal studies is presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Risk of bias assessment in case-controlled animal studies.

Amongst 18 case precise studies, bias risk was shared among the included studies between high risk of bias and low risk of bias for items present for the SYRCLE tool [44]. This high or great bias risk was due to the allocation concealment, unsystematic housing, blinding, and incomplete outcome data. This is a common practice in animal studies as the current design of protocols and reporting of animal studies are very poor [37].

3.4. Decrease in Blood Glucose Level

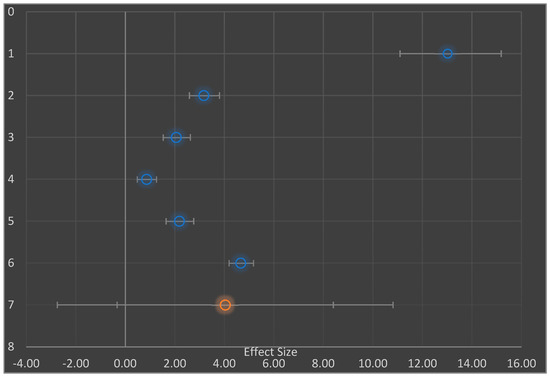

Hypoglycemic measures were examined in six studies [3,5,15,36,40,42]. Each of the studies were further examined by separating them into experimental groups: negative diabetic control at baseline and diabetic intervention group (the former was given no intervention-SFP or NSFP); subgroups were involved in meta-analysis as well as practical statistically significant positive effect on the studies (Figure 4). Therefore, the combined effect sizes of the studies were (mean difference 4.0 mg/dL, 95% CI −0.33–8.40 as well as the difference in mean of 4.4 mg/dL, 95% CI −0.82–9.66) as shown in the Forest plot (Figure 4 and Figure 5 respectively.

Figure 4.

Forest Plot showing random effect meta-analysis of the mean difference in control of blood sugar level (mg/dL), based on diabetic intervention and negative diabetic control. Data for studies 1, 2, 3, and 4 are based primarily on control of blood sugar level whereas data for studies 5 and 6 are based on control of blood sugar level in sustained release-time.

Figure 5.

Showing random effect meta-analysis of the mean different in total subgroup analysis for the decrease in blood sugar level (mg/dL).

Due to the large proportion of I2 value (98%) in the studies (Table 4), we explored both the subgroup (Figure 4) and moderator (Figure 5) analyses, which proved that the investigations for meta-analysis came from a heterogeneous population. Hence, the extent of heterogeneity was examined. The random effect model was used to assume that there was heterogeneity in the subgroups. Consequently, the combined effect sizes in the subgroups (AA and BB) were not used. Instead, the prediction interval was used (mean difference 4.4 mg/dL, 95% prediction interval (PI) −6.65 to 15.50 and mean difference 3.4 mg/dL, 95% prediction interval −23.65 to 30.50) [45,49].

Due to the large proportion of I2 value (98%) in the studies (Table 4), we explored both the subgroup (Figure 4) and moderator (Figure 5) analyses, which proved that the investigations for meta-analysis came from a heterogeneous population. Hence, the extent of heterogeneity was examined [45,49]. The random effect model was used to assume that there was heterogeneity in the subgroups. Consequently, the combined effect sizes in the subgroups (AA and BB) were not used. Instead, the prediction interval (PI) was used (mean difference 4.4 mg/dL, 95% (PI) −6.65 to 15.50 and mean difference 3.4 mg/dL, 95% PI −23.65 to 30.50) rather than the estimate of its confidence interval (best vital result of ‘random outcomes’ representative; once the situation needs to be presumed ‘true’, outcome dimensions differ)

Regarding regression on moderator effect size (Figure 4), there was an observable strong correlation among moderator as well as detected influence dimensions. These were long-established with significant outcomes in the importance test of regression load p < 0.05 (Table 8).

Table 8.

Regression of moderator on effect size showing a model y= −3.31791 + 0.13252x and p < 0.05.

This proved the value effect of the study sizes on the intervention. Furthermore, Figure 5 presents the funnel plot for the random effect meta-analysis on the mean difference in the decrease of blood glucose (mg/dL) based on the intervention or negative diabetic control, indicating asymmetry in the distribution of the effect sizes. Therefore, studies of this effect (X→Y) have been conducted in the following populations. The following weight change and enzyme inhibition population have not been studied. Observed effects range from −0.33 to 8.40. Effects in subgroup A “Diabetic intervention” range from −0.82 to 9.66. (Table 8) [45].

4. Discussion

This systematic review of case-controlled animal studies examining the decrease of blood glucose level in diabetic animals found evidence to support the notion that chitosan nanogel can relate to mixed unripe plantain, bitter yam, and okra in controlling T2D. The results remained similar when subgroup analysis was performed. The review questions the single use of the SFP, the use in combination with NSFP, and without cross-linking them with chitosan controlling T2D.

4.1. Principal Findings

Meta-analysis of the diabetic intervention subgroup demonstrated decreased hyperglycemia against blood sugar negative regulator [11,15,36,40,42,47]. However, studies from subgroup AA (diabetic intervention) influenced much of the bases for the overall decrease in blood glucose level as these studies were studies which had as primary outcome measure the decrease of blood glucose and secondary outcome measures including increase of body weight, inhibition ofα-amylase and α-glucosidase, as well as neuropathy [11,36,47,49].

Studies of the subgroup included in the meta-analysis gave results that agreed with the different analysis proving heterogeneity of the six studies formed the I2 value (Forest plot, subgroup analysis, moderator analysis and publication bias analysis [45]). As a consequence of this development, the overall combined effect sizes from the meta-analysis (Forest plot) were not useful due to the non-homogeneous studies included (not from a single population of population samples) [45,49].

4.2. Quality of Evidence

We reflected on the value of evidence which was reasonably low due to the following explanations: involved investigation remained at 50% high risk of bias and 50% at low risk of bias; with the high-risk bias coming from the designed protocol [44]. We also saw a high level of heterogeneity among the involved investigations (diabetic intervention). This heterogeneity could reflect the different populations being examined. For instance, the populations of the diabetic interventions that also had weight change, enzyme inhibition, and neuropathy were different from the population of diabetic intervention by a sustained release-time [4,31,41,47].

Ten out of the eighteen studies included in the systematic review were studies based on the SFP and NSFP (coco- yam, soya bean cake, cassava fibre and rice bran) [2,5,47,50], while eight studies used only chitosan to encapsulate active bio-compounds [16,30,33,39,40,41,42].

Furthermore, investigation involved in the review lasted between three and 84 days (three days [10,29]; five days [30]; eight days [30]; 10 days [42]; 14 days [3,32,42]; 21 days [36]; 28 days [3,4,5,24,33,35,51]; 31 days [50], and 84 days [15]). This proved the potency and efficacy of the intervention over both short and long durations. This meant that there was strong effect in the intervention given to the animals.

4.3. Limitation

This review had limitations. Our search strategy could have omitted abstracts and full text articles that were published in other languages besides English. This omission could have affected the number of studies included in the meta-analysis and the nature of the result with respect to a more homogeneous population [14,17].

5. Conclusions and Future Implication

As the quality of the included studies was moderately low in percentage (50%), which means that the overall risk of bias was unclear risk (50% low risk of bias and 50% high risk of bias), there was insufficient information provided by the study authors in their protocol, and final outcomes ought to be inferred cautiously. However, current evidence available does support the relation of chitosan to mixed unripe plantain, bitter yam, and okra for the management of T2D. We recommend that high quality case-controlled animal studies are carried out to substantiate whether chitosan nanogel should indeed be cross-linked with the SFP for the management of T2D.

Furthermore, research efforts could be geared towards extracting the phytonutrients contained in these food plants, concentrate and fractionate (partitioned) alike, so that extract fractions obtained can be used to test the efficacy of these food plants either through in vitro or in vivo experimentations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A. and E.A.; methodology, M.A. and E.A.; software, M.A. and E.A.; validation, K.N.F., C.P. and D.P.; formal analysis, MA.; investigation, E.A., K.N.F. and C.P.; resources, M.A. and E.A.; data curation, M.A. and E.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.; writing—review and editing, M.A. and E.A.; visualization, M.A., E.A., K.N.F., C.P. and D.P.; supervision, E.A., K.N.F. and C.P.; project administration, E.A.; funding acquisition, E.A., K.N.F., C.P. and D.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization, Global Report on Diabetes; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- Odebode, F.D.; Ekeleme, O.T.; Ijarotimi, O.S.; Malomo, S.A.; Idowu, A.O.; Badejo, A.A.; Adebayo, I.A.; Fagbemi, T.N. Nutritional composition, antidiabetic and antilipidemic potentials of flour blends made from unripe plantain, soybean cake, and rice bran. J. Food Biochem. 2018, 42, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shodehinde, S.A.; Ademiluyi, A.O.; Oboh, G.; Akindahunsi, A.A. Contribution of Musa paradisiaca in the inhibition of α-amylase, α-glucosidase and Angiotensin-I converting enzyme in streptozotocin induced rats. Life Sci. 2015, 133, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iroaganachi, M.; Eleazu, C.O.; Okafor, P.N.; Nwaohu, N. Effect of Unripe Plantain (Musa paradisiaca) and Ginger (Zingiber officinale) on Blood Glucose, Body Weight and Feed Intake of Streptozotocin-induced Diabetic Rats. Biochem. J. 2015, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Eleazu, C.O.; Okafor, P. Use of unripe plantain (Musa paradisiaca) in the management of diabetes and hepatic dysfunction in streptozotocin induced diabetes in rats. Interv. Med. Appl. Sci. 2015, 7, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adefegha, S.A.; Oboh, G.; Olabiy, A.A. Nutritional, antioxidant and inhibitory properties of cocoa powder enriched wheat-plantain biscuits on key enzymes linked to type 2 diabetes. Int. Food Res. J. 2018, 25, 793–803. [Google Scholar]

- Sarafidis, P.; Ferro, C.J.; Morales, E.; Ortiz, A.; Malyszko, J.; Hojs, R.; Khazim, K.; Ekart, R.; Valdivielso, J.; Fouque, D.; et al. SGLT-2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists for nephroprotection and cardioprotection in patients with diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease. A consensus statement by the EURECA-m and the DIABESITY working groups of the ERA-EDTA. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2019, 34, 208–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabhi, A.S.; Bhatt, N.R.; Shah, M.J. Voglibose: An alpha glucosidase inhibitor. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2013, 7, 3023–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabitha, V.; Panneerselvam, K.; Ramachandran, S. In vitro α–glucosidase and α–amylase enzyme inhibitory effects in aqueous extracts of Abelmoscus esculentus (L.) moench. Asian Pac. Trop. Biomed. 2012, 2, 162–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wang, O.; Liu, J.; Cai, S.; Wang, R.; Zhou, F.; Ji, B. Anti-diabetic effects of the ethanol extract of a functional formula diet in mice fed with a fructose/fat-rich combination diet. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2015, 95, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oboh, G.; Adefegha, S.A.; Ademosun, A.O.; Unu, D. Effects of hot water treatment on the phenolic phytochemicals and antioxidant activities of lemon grass (Cymbopogon citratus). Elec. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 9, 503–513. [Google Scholar]

- Adefegha, S.A.; Oboh, G. Enhancement of total phenolics and antioxidant properties of some tropical green leafy vegetables by steam cooking. J. Food Process Pres. 2011, 35, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabitha, V.; Ramachandran, S.; Naveen, K.R.; Panneerselvam, K. Antidiabetic and antihyperlipidemic potential of Abelmoschus esculentus (L.) moench. In streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J. Pharm. Bioallied. Sci. 2011, 3, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sabitha, V.; Ramachandran, S.; Naveen, K.R.; Panneerselvam, K. Investigation of in vivo antioxidant property of Abelmoschus esculentus (L.) moench. Fruit seed and peel powders in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J. Ayurveda Integr. Med. 2012, 3, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Wang, C.; Lin, C.; Lin, H.; Peng, C. The nutraceutical benefits of subfractions of Abelmoschus esculentus in treating type 2 diabetes mellitus. PLoS ONE. 2017, 12, e0189065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martirosyan, D.; Singh, J. A new definition of functional food by FFC: What makes a new definition unique? Funct. Food Health Dis. 2015, 5, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathish, K.; Eswar, T.; Praveen, K.; Ashok, K.; Bramha, S.; Ramarao, N. A review on: Abelmoschus esculentus (okra). IRJP 2013, 3, 129–132. [Google Scholar]

- Dike, L.P.; Obembe, O.O.; Adebiyi, E.F. Ethnobotanical survey for potential anti-malarial plants in south-western Nigeria. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 144, 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbuonu, A.C.C.; Nzewi, D.C.; Egbuonu, O.N.C. Functional Properties of Bitter Yam (Dioscorea dumetorum) as Influenced by Soaking Prior to Oven-drying. Am. J. Food Technol. 2014, 9, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagpal, K.; Singh, S.K.; Mishra, D.N. Chitosan Nanoparticles: A Promising System in Novel Drug Delivery. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2010, 58, 1423–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chem, M.C.; Mi, F.L.; Liao, Z.X.; Hsiao, C.W.; Sonaje, K.; Chung, M.F.; Hsu, L.W.; Sung, H.W. Recent advances in chitosan-based nanoparticles for oral delivery of macromolecules. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013, 65, 865–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimenibo-Uadia, R.; Oriakhi, A. Proximate, Mineral and Phytochemical Composition of Dioscorea dumetorum Pax. J. Appl. SCI. Environ. Manag. 2017, 21, 771. [Google Scholar]

- Famakin, O.; Fatoyinbo, A.; Ijarotimi, O.S.; Badejo, A.A.; Fagbemi, T.N. Assessment of nutritional quality, glycaemic index, antidiabetic and sensory properties of plantain (Musa paradisiaca)-based functional dough meals. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 53, 3865–3875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguekouo, P.T.; Kuate, D.; Kengne, A.P.N.; Woumbo, C.Y.; Tekou, F.A.; Oben, J.E. Effect of boiling and roasting on the antidiabetic activity of Abelmoschus esculentus (Okra) fruits and seeds in type 2 diabetic rats. J. Food Biochem. 2018, 42, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, H.; Rahman, M.M.; Kim, G.; Na, C.; Song, C.; Kim, J.; Kim, S.; Kang, H. Antidiabetic Effects of Yam (Dioscorea batatas) and Its Active Constituent, Allantoin, in a Rat Model of Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetes. Nutrients 2015, 7, 8532–8544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Chu, Y.; Wu, X.; Liu, R. Antioxidant and anti-proliferative activities of common fruits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 7449–7454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra, S.; Saha, R.; Pal, P. Arsenic Uptake and Accumulation in Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) as Affected by Different Arsenical Speciation. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2016, 96, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thulé, P.M.; Umpierrez, G. Sulfonylureas: A new look at old therapy. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2014, 14, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, S.; Das, D.; Dutta, P.; Kalita, J.; Wann, S.B.; Manna, P. Chitosan: A promising therapeutic agent and effective drug delivery system in managing diabetes mellitus. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 247, 116594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Choi, J.S.; Kim, I.; Byeon, H.J.; Kim, T.H.; Oh, K.T.; Lee, E.S.; Lee, K.C.; Youn, Y.S. Decanoic acid-modified glycol chitosan hydrogels containing tightly adsorbed palmityl-acylated exendin-4 as a long-acting sustained-release anti-diabetic system. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 812–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Zhi, Z.; Pickup, J.C. Nanolayer encapsulation of insulin- chitosan complexes improves efficiency of oral insulin delivery. Int. J. Nanomed. 2014, 9, 2127–2136. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, S.; Ha, K.; Moon, K.; Kim, J.; Oh, C.; Kim, Y.; Apostolidis, E.; Kwon, Y. Molecular Weight Dependent Glucose Lowering Effect of Low Molecular Weight Chitosan Oligosaccharide (GO2KA1) on Postprandial Blood Glucose Level in SD Rats Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 14214–14224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szekalska, M.; Sosnowska, K.; Zakrzeska, A.; Kasacka, I.; Lewandowska, A.; Winnicka, K. The Influence of Chitosan Cross-linking on the Properties of Alginate Microparticles with Metformin Hydrochloride—In Vitro and in Vivo Evaluation. Molecules 2017, 22, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adepoju, O.T.; Sunday, B.E.; Folaranmi, O.A. Nutrient composition and contribution of plantain (Musa paradisiacea) products to dietary diversity of Nigerian consumers. Afi. J. Biotechnol. 2012, 11, 13601–13605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajiboye, B.O.; Oloyede, H.O.B.; Salawu, M.O. Antihyperglycemic and antidyslipidemic activity of Musa paradisiaca-based diet in alloxan- induced diabetic rats. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 6, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleazu, C.O.; Iroaganachi, M.; Eleazu, K.C. Ameliorative Potentials of Cocoyam (Colocasia esculenta L.) and Unripe Plantain (Musa paradisiaca L.) on the Relative Tissue Weights of Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats. J. Diabetes Res. 2013, 2013, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooijmans, C.R.; IntHout, J.; Ritskes-Hoitinga, M.; Rovers, M.M. Meta-Analyses of Animal Studies: An Introduction of a Valuable Instrument to Further Improve Healthcare. ILAR J. 2014, 55, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemede, H.F.; Ratta, N.; Haki, G.D.; Woldegiorgis, A.Z.; Beyene, F. Nutritional quality and health benefits of okra (Abelmoschus esculentus): A review. J. Food Qual. 2014, 33, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, C.; Kim, T.H.; Lee, E.S.; Shin, B.S.; Chi, S.C.; Park, E.; Lee, K.C.; Youn, Y.S. Self-assembled glycol chitosan nanogels containing palmityl-acylated exendin-4 peptide as a long-acting anti-diabetic inhalation system. J. Control. Release 2012, 161, 728–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raafat, K.; Samy, W. Amelioration of Diabetes and Painful Diabetic Neuropathy by Punica granatum L. Extract and Its Spray Dried Biopolymeric Dispersions. Evid. Based Compl. Alt. 2014, 2014, 180495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.; Lee, I.; Lee, E.; Kim, H.; Kim, Y.; Jon, S. Oral delivery of an anti-diabetic peptide drug via conjugation and complexation with low molecular weight chitosan. J. Control. Release 2013, 170, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, M.; Aniceto, D.; Abrantes, M.; Simões, S.; Branco, F.; Vitória, I.; Botelho, M.F.; Seiça, F.; Veiga, F.; Ribeiro, A. In vivo biodistribution of antihyperglycemic biopolymer-based nanoparticles for the treatment of type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharma. 2017, 113, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Modified for use The PRISMA Group; Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement 2009. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar]

- Hooijmans, C.R.; Rovers, M.M.; de Vries, R.B.M.; Leenaars, M.; Ritskes-Hoitinga, M.; Langendam, M.W. SYRCLE’s risk of bias tool for animal studies. BMC. Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hak, T.; Van Rhee, H.J.; Suurmond, R. How to Interpret Results of Meta-Analysis? Version 1.3; Erasmus Rotterdam Institute of Management: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Suurmond, R.; van Rhee, H.; Hak, T. Introduction, comparison and validation of Meta-Essentials: A free and simple tool for meta-analysis. Res. Synth. Methods 2017, 8, 537–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adefegha, S.A.; Oboh, G. Inhibition of Key Enzymes Linked to Type 2 Diabetes and Sodium Nitroprusside-Induced Lipid Peroxidation in Rat Pancreas by Water Extractable Phytochemicals from Some Tropical Spices. Pharm. Biol. 2012, 50, 857–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, A.A.; Khater, S.I.; Hamed Arisha, A.; Metwally, M.M.M.; Mostafa-Hedeab, G.; El-Shetry, E.S. Chitosan-stabilized selenium nanoparticles alleviate cardio-hepatic damage in type 2 diabetes mellitus model via regulation of caspase, Bax/Bcl-2, and Fas/FasL-pathway. Gene 2021, 768, 145288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rhee, H.J.; Suurmond, R.; Hak, T. User Manual for Meta-Essentials: Workbooks for Meta-Analysis; Version 1.4; Erasmus Research Institute of Management: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Adamson, S.S.; Craniyu, O. Aqueous Extracts from Unripe Plantain (Musa paradisiaca) Products Inhibit Key Enzymes Linked with Type 2 Diabetes and Hypertension in vitro. Jordan J. Biol. Sci. 2012, 54, 239–246. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Q.; Spiegelman, D.; Van Dam, R.M.; Holmes, M.D.; Malik, V.S.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. White rice, brown rice, and risk of type 2 diabetes in US men and women. Arch. Intern. Med. 2010, 170, 961–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).