Highlights

What are the main findings?

- The proposed TPDTC-Net-DRA architecture demonstrates superior performance in intense precipitation nowcasting. The integration of dynamic region modules and weight control modules within the encoder overcomes the spatial feature extraction limitations of prior methods by focusing on precipitation regions.

- The novel dynamic region attention (DRA) mechanism effectively enhances model accuracy. By dynamically guiding the model’s attention computation to precipitation regions, the DRA mechanism successfully reduces computational redundancy over non-informative regions.

What are the implication of the main findings?

- TPDTC-Net-DRA provides a new architectural paradigm for meteorological forecasting models and offers a design framework for addressing similar spatiotemporal prediction challenges. Explicitly incorporating dynamic region focus and adaptive weight control within the encoder is a practical strategy for enhancing spatial feature extraction in nowcasting tasks.

- The DRA mechanism exhibits strong generalizability and portability. The DRA mechanism is not architecture-specific. Its ability to be seamlessly integrated into other encoder–decoder models suggests it can serve as a plug-and-play module to boost the performance of a wide range of spatiotemporal prediction tasks beyond precipitation nowcasting.

Abstract

Heavy precipitation events are characterized by sudden onset, limited spatiotemporal scales, rapid evolution, and high disaster potential, posing long-standing challenges in weather forecasting. With the development of deep learning, an increasing number of researchers have leveraged its powerful feature representation and non-linear modeling capabilities to address the challenge of precipitation nowcasting. Despite recent advances in deep learning for precipitation nowcasting, most existing methods do not explicitly separate precipitation from non-precipitation regions. This often leads to the extraction of redundant or irrelevant features, thereby causing models to learn misleading patterns and ultimately reducing their predictive capability for heavy precipitation events. To address this issue, we propose a novel dynamic region attention (DRA) mechanism, and an improved model TPDTC-Net-DRA, based on our previously introduced TPDTC-Net. The proposed TPDTC-Net-DRA applies the DRA mechanism and incorporates its two key components: a dynamic region module and a weight control module. The dynamic region module generates a mask matrix that is applied to the feature maps, guiding the attention mechanism to focus only on precipitation areas. Meanwhile, the weight control module produces a location-sensitive weight matrix to direct the model’s attention toward regions with intense precipitation. Extensive experiments demonstrate that TPDTC-Net-DRA achieves superior performance for heavy precipitation, outperforming current state-of-the-art methods, and indicate that the proposed DRA mechanism exhibits strong generalization ability across diverse model architectures.

1. Introduction

Heavy precipitation is typically defined as a precipitation event with an amount of ≥10 mm within 1 h [1,2]. Characterized by rapid onset and dissipation, high spatial locality, and significant destructive potential, this phenomenon represents a major meteorological hazard affecting most regions. Accurate nowcasting of heavy precipitation is critically important for agricultural production [3,4,5], urban drainage systems [6,7,8], transportation networks [9,10,11], etc., causing substantial socioeconomic impacts. However, nowcasting and early warning for heavy precipitation events remain significant challenges for operational meteorological services [12].

Precipitation nowcasting can be primarily categorized into two groups: traditional methods and deep learning-based methods. Traditional methods mainly include numerical weather prediction (NWP) [13] and radar echo extrapolation [14]. NWP employs numerical calculations based on the atmospheric state under specified initial and boundary conditions to forecast weather evolution processes within a specified future time frame [15]. NWP has a robust theoretical foundation, enabling the prediction of future weather conditions through model simulations without relying solely on direct observational data. Currently, numerous national and regional meteorological services operate NWP systems, such as China’s global/regional assimilation and prediction system (GRAPES) [16] and the United States’ weather research and forecasting model (WRF) [17]. However, NWP still faces significant challenges. Firstly, numerical models require substantial computational resources, and the computational load increases dramatically as spatial resolution increases [18]. Secondly, NWP exhibits high sensitivity to initial conditions, particularly for short-term forecasts. Errors in the initial field amplify rapidly, degrading forecast accuracy [19,20]. Furthermore, accurately capturing complex meteorological processes, such as severe convective weather and atmospheric instabilities, remains a challenge within NWP frameworks.

Radar echo extrapolation forecasts future echoes using historical radar data to improve short-term prediction precision. Current methods include three primary techniques: cross-correlation method, monomer centroid method and optical flow method [21,22]. Optical flow methods, the most widely applied approach, originate from computer vision. They estimate motion vectors between consecutive radar frames by analyzing pixel-level temporal variations and inter-frame correlations [23]. Nevertheless, these conventional radar echo extrapolation approaches suffer from severe limitations: predictive skill decays rapidly with longer lead times, overall extrapolation capability is limited, and predicted fields progressively exhibit distortion effects. Consequently, the discrepancy between the predicted and actual precipitation patterns is amplified, making it difficult to satisfy the precision requirements of precipitation nowcasting [24].

Unlike physics-based numerical weather prediction models, deep learning provides a data-driven approach. With its powerful nonlinear fitting capability, it learns underlying physical patterns from massive historical observations, enabling efficient inference of short-term precipitation distributions and demonstrating significant application potential [3,25]. By training on historical radar echo sequences, deep learning models learn spatiotemporal features inherent in echo evolution, generating predictions within shorter time frames [26].

Although deep learning-based methods have significantly promoted heavy precipitation nowcasting, existing approaches often inadequately distinguish precipitation regions from non-precipitation areas during data processing. This leads to the neural network being disturbed by redundant information from irrelevant regions, thereby affecting the prediction effect. Simultaneously, insufficient focus on high-intensity precipitation regions further diminishes the capability for nowcasting heavy precipitation.

To address these issues, this paper proposes a novel dynamic region attention (DRA) mechanism, and temporal predictor and dynamic Transformer-CNN network with DRA (TPDTC-Net-DRA), a deep learning framework for heavy precipitation nowcasting based on our previously introduced temporal predictor and dynamic Transformer–CNN network (TPDTC-Net) [27]. The method incorporates the DRA mechanism and utilizes its two synergistic modules: the dynamic region module (DRM) calculates a mask matrix to selectively weight feature maps, concentrating attention on precipitation-active regions; the weight control module (WCM) generates location-specific weights to amplify focus on high-intensity precipitation regions. The proposed architecture significantly enhances the accuracy of prediction for heavy precipitation scenarios. The major contributions of this work are as follows.

- This paper proposes TPDTC-Net-DRA, an encoder–temporal predictor–decoder architecture that incorporates dynamic region modules and weight control modules within the encoder. This design overcomes the spatial feature extraction limitations of existing methods by focusing on precipitation regions, thereby substantially improving intense precipitation nowcasting performance.

- A dynamic region attention, i.e., DRA mechanism is proposed, which enables the model to focus on precipitation areas during attention computation, effectively reducing redundant operations over non-informative regions and improving prediction accuracy. The proposed DRA mechanism is not only applicable to our proposed TPDTC-Net-DRA, but can also be seamlessly integrated into other encoder–decoder architectures.

- Comprehensive experiments on the standard benchmark dataset demonstrate that TPDTC-Net-DRA outperforms state-of-the-art methods in heavy precipitation nowcasting, with its dynamic region attention mechanism significantly improving nowcasting accuracy.

2. Related Work

2.1. Deep Learning-Based Precipitation Nowcasting

Precipitation nowcasting can be regarded as a radar-echo sequence forecasting task. From a learning perspective, it is a subtask of spatiotemporal sequence prediction (or more broadly, image sequence prediction) [28]. Current deep learning-based models for precipitation nowcasting mainly fall into three categories: convolutional neural network (CNN) architectures represented by UNet [29], recurrent neural network (RNN) architectures represented by convolutional long short-term memory (ConvLSTM) [30], and self-attention-based architectures represented by Transformer models.

UNet has been increasingly adopted for precipitation nowcasting in recent years. This is mainly due to its architectural simplicity, low computational overhead, ease of deployment, and strong ability to preserve spatial resolution compared with many other CNNs. Agrawal et al. [31] introduced UNet into precipitation nowcasting by categorizing precipitation intensity into three classes, enabling probabilistic precipitation forecasts over the continental United States. Building upon UNet, Song et al. [32] incorporated the squeeze-and-excitation (SE) module [33] to enhance the inter-channel feature representation, proposing the SE-ResUNet model (integrating ResNet, squeeze-and-excitation, and an attention mechanism), which has been deployed in operational meteorological services in the Haidian district meteorological bureau of Beijing. Convolution is inherently tailored to capture local spatial dependencies within images, but it is ill-equipped to model temporal evolution. Even when extended to three dimensions, e.g., the spatiotemporal convolutional sequence-to-sequence network (STConvS2S) [34], it still struggles to fully represent the intricate and non-stationary spatiotemporal dynamics of precipitation. This limitation has motivated a shift toward unified learning frameworks that more tightly couple spatial and temporal modeling, thereby continuously advancing both forecast accuracy and operational utility in precipitation nowcasting.

In contrast to convolutional neural networks, which are well suited for extracting spatial features, recurrent neural networks (RNNs) exhibit strong capabilities for modeling sequential data [35]. Building upon the classical LSTM network [36], Shi et al. [30] integrated convolutional operations to propose ConvLSTM, which was applied to precipitation nowcasting over the Hong Kong region. To further enhance the model’s capability in capturing dynamic spatial changes, they later introduced a trajectory-based gating mechanism, leading to the development of the trajectory gated recurrent unit (TrajGRU) [37], which enables the model to learn patterns of spatial displacement. Wang et al. [38] extended ConvLSTM and proposed a predictive recurrent neural network (PredRNN), which incorporates a spatiotemporal memory mechanism that can be passed across layers, effectively overcoming the temporal independence limitation of memory cells in traditional ConvLSTM architectures. This design significantly improves the model’s ability to capture complex spatiotemporal dependencies. Inspired by the classical time series modeling approach autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA), Wang et al. further proposed the memory in memory (MIM) model [39], which introduces both non-stationary and stationary memory units into the PredRNN framework. Additionally, a diagonal differencing tensor flow mechanism was designed to model non-stationary spatiotemporal dynamics, enhancing the model’s ability to learn temporal trends within sequences. Wu et al. [40] found that simultaneously capturing both the transient fluctuations and the evolving trend of motion is crucial for improving a model’s ability to predict spatiotemporal changes. Building on this, they proposed the MotionRNN model, which integrates a MotionGRU module across network layers. Combined with a momentum decay strategy, this approach enables joint modeling of transient memory and trend memory, thereby further improving its ability to characterize complex spatiotemporal evolution.

Transformer [41] and its spatiotemporal extensions, which leverage the strong ability of the self-attention mechanism to model long-range dependencies, have demonstrated superior performance in handling complex nonlinear dynamics and long temporal sequences. Consequently, they have emerged as a key research focus in precipitation nowcasting. Bai et al. [42] proposed a novel nowcasting framework called Rainformer, which enhances prediction accuracy by combining window-based multi-head self-attention with gated fusion units. Park et al. [43] proposed Nowformer, a Transformer-based nowcasting model for short-term precipitation forecasting, which fuses large-kernel global convolutions with local dynamic modeling to accurately capture the spatial trajectory and lifecycle characteristics of precipitation, thereby enhancing the model’s perception of the short-term evolution of precipitation. Zhang et al. [44] proposed NowcastNet, which unifies physical evolution mechanisms with conditional learning into a single end-to-end neural network framework. This model effectively mitigates common challenges in extreme precipitation forecasting, such as blurriness and positional biases, while providing fine-grained representations of varying precipitation intensities. Gao et al. [45] introduced Earthformer, a model designed for forecasting tasks related to the Earth system. It incorporates a cuboid attention mechanism that restricts self-attention computation to local cuboidal regions, reducing complexity while enabling cross-region communication via global tokens. This design further enhances the model’s ability to capture global spatiotemporal dependencies.

2.2. Heavy Precipitation Nowcasting

In the field of precipitation forecasting, most existing deep learning-based studies focus on predicting low- to moderate-intensity precipitation, while forecasting performance for heavy precipitation (i.e., precipitation intensity greater than 10 mm/h) often fails to meet practical requirements [46]. Such forecasting biases may lead to delayed or incorrect warnings for disasters triggered by extreme precipitation, thereby resulting in significant casualties and economic losses. Therefore, the term heavy used in this study is defined by an absolute quantitative threshold, representing a predefined boundary. Specifically, precipitation events with an intensity greater than 10 mm/h are defined as heavy precipitation.

Nowcasting systems analyze the characteristics, intensity, and dynamic changes of radar echoes to identify and predict the initiation, development, and movement of precipitation at varying intensities, thereby providing accurate precipitation forecasts. For example, Ji et al. [47] proposed the convolutional LSTM GAN (CLGAN) network, which combines the advantage of GAN model sensitivity to component weights with the powerful spatiotemporal feature extraction capabilities of U-Nets and ConvLSTM models to accurately capture heavy precipitation events. Wang et al. [48] introduced a novel heavy precipitation nowcasting model based on an innovative task-segmented architecture, namely, TS-RainGAN. This model incorporates two key modules for heavy precipitation prediction: first, the mask prediction network (MaskPredNet) predicts the spatial coverage of different precipitation categories, providing boundary identification for precipitation of varying intensities; then, the mask-to-intensity translation generative adversarial network (IntensityGAN) uses the generated precipitation coverage to predict precipitation intensity. Another study utilized self-organizing map (SOM) and k-means algorithms to cluster precipitation types (e.g., low-intensity and high-intensity categories) and trained a prediction model based on the clustering results, significantly enhancing the forecasting performance for high-intensity precipitation [49]. Tan et al. [50] proposed a multi-scale feature fusion (MFF) module that employs a discrete probability mechanism to reduce uncertainty and prediction errors, enabling it to forecast heavy precipitation even at longer lead times.

Recent studies have demonstrated that attention mechanisms can significantly improve heavy precipitation forecasting performance [51]. Bai et al. [42] enhanced their model by incorporating a self-attention mechanism to capture global features, which directs the attention features more toward regions with exceptionally high values and small spatial extents associated with intense precipitation, thereby effectively overcoming the locality of convolutional operations. Li et al. [52] integrated Transformer with a causal attention mechanism and proposed the diffusion transformer with causal attention (DTCA), which establishes spatiotemporal queries between conditional information (cause) and predicted outcomes (effect). This design allows the model to effectively capture long-range dependencies, ensuring that predictions maintain strong causality with input conditions across extended temporal and spatial scales. This method increased the critical success index (CSI) for heavy precipitation prediction by approximately 15% and 8%, respectively. Wen et al. [53] introduced a novel quantitative precipitation estimation (QPE) model that incorporates the convolutional block attention module (CBAM) to guide the model to focus on individual cells most likely to produce heavy precipitation. The model achieved CSI and HSS scores of 0.6769 and 0.7910, respectively. Zhang et al. [54] combined CNNs, a bidirectional long short-term memory (BiLSTM) system, and an attention mechanism to propose the CNN-BiLSTM-AM model, which predicts severe convective weather using ERA5 hourly data and observations. The model achieved an RMSE of only 11.11 mm, indicating a significant error reduction compared to conventional nowcasting models. Additionally, it attained a notable correlation coefficient of nearly 97%, reflecting a strong agreement between predicted and observed precipitation.

Similarly, early precipitation-masked attention approaches obtain relatively static or coarse precipitation masks from consecutive radar frames. For instance, GA-SmaAt-GNet [55] and CLGAN [47] exploit the advantages of adversarial learning for binary precipitation prediction and incorporate convolutional block attention modules (CBAM) to emphasize relevant features generated by preceding convolutional layers. NowcastNet [44] enhances the representation of precipitation primarily by increasing the sampling probability of precipitation samples within a batch, rather than applying pixel level weighting. Some studies have also leveraged generic saliency gating mechanisms to achieve heavy precipitation prediction. Wu et al. proposed GA-LSTM [56], which introduces an LSTM-Atten module to selectively extract and weight historical states with respect to the current input, with attention unfolding along the temporal dimension. Liu et al. proposed a multi-scale gated temporal spatial attention network (MGTSA-Net) [57], which computes attention weights by modeling correlations across features at different scales. In most of these methods, the enhancement of heavy precipitation information is either indirect or limited, or lacks explicit spatial focusing constraints on heavy precipitation regions. To address this limitation, we propose a dynamic region attention mechanism. On the one hand, the dynamic region module flexibly extracts multi-scale information from precipitation features by dividing the data into four branches; on the other hand, a weight control module is introduced to impose stronger constraints and reinforcement on key regions, thereby encouraging the network to focus on heavy precipitation more directly and stably.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Overall Structure Diagram

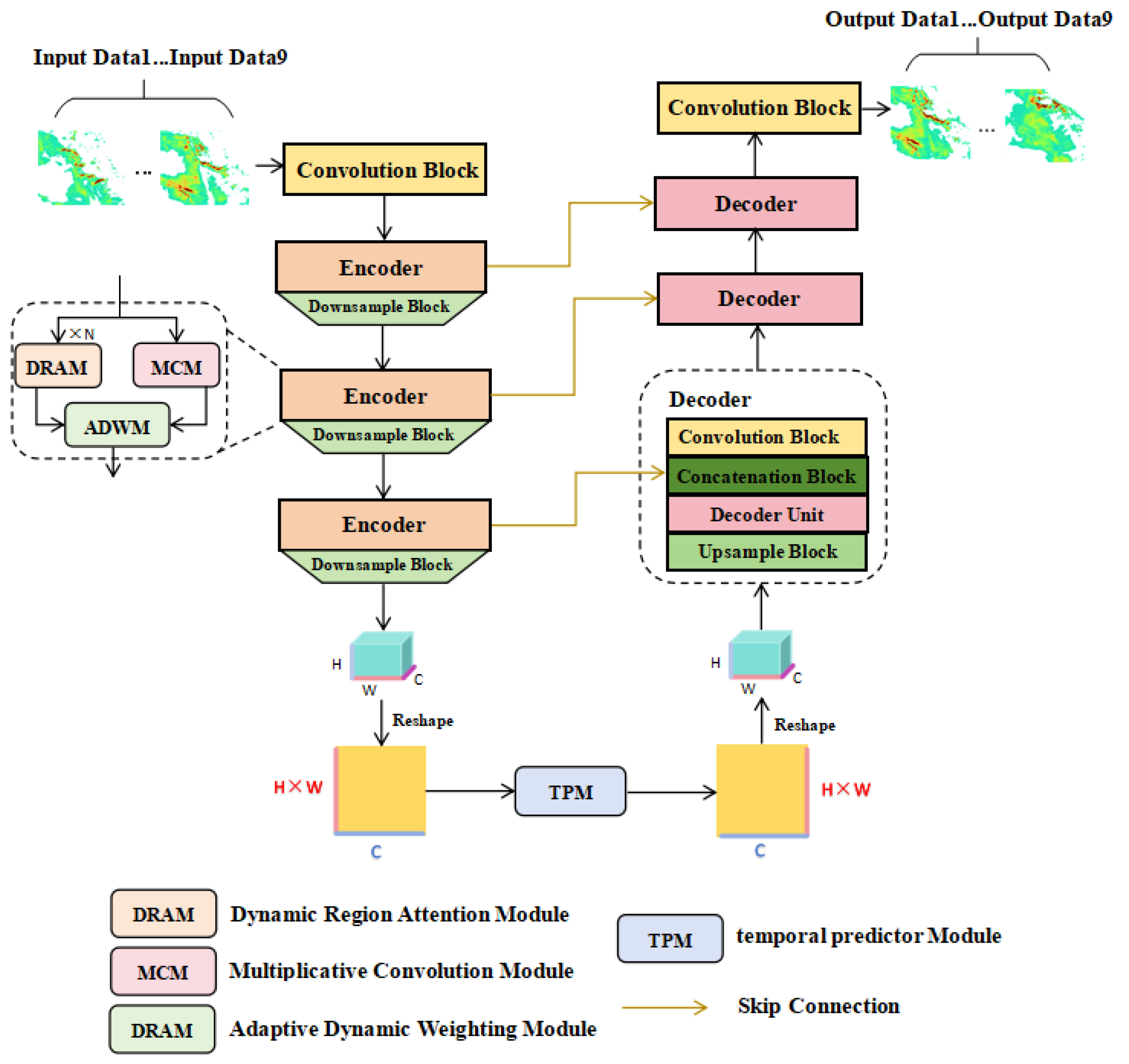

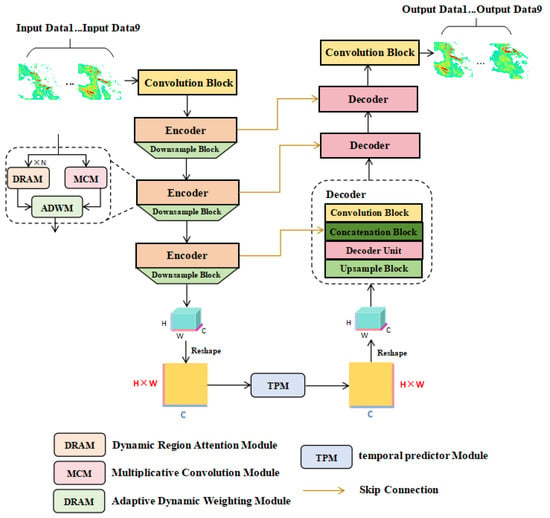

The proposed TPDTC-Net-DRA method is an enhanced version built upon our previously developed TPDTC-Net [27]. Its overall framework is illustrated in Figure 1. Similarly to its predecessor, the network retains an encoder–time predictor–decoder structure. The key distinction lies in the composition of each encoder block: TPDTC-Net-DRA integrates several DRA modules, a multiplicative convolution module, and an adaptive dynamic weighting module (DWM). Specifically, the DRA module is designed to address computational redundancy in TPDTC-Net caused by interference from precipitation-free regions. This module dynamically directs the network’s focus toward regions with higher precipitation intensity, thereby improving both the accuracy and efficiency of precipitation forecasts, while significantly enhancing the predictive performance of the model for heavy precipitation events.

Figure 1.

The TPDTC-Net-DRA consists of three core modules: an encoder, a temporal predictor, and a decoder. The encoder is designed to capture the spatial features of precipitation; the temporal predictor is used to extract temporal information from the feature maps; and the decoder, through skip connections, integrates the features output by the encoder and the temporal predictor to achieve the reconstruction and generation of prediction results. C × W × H denotes the size of the convolutional kernel (matrix), and ×N indicates that one encoder contains N DRA modules.

3.2. Dynamic Region Attention Mechanism

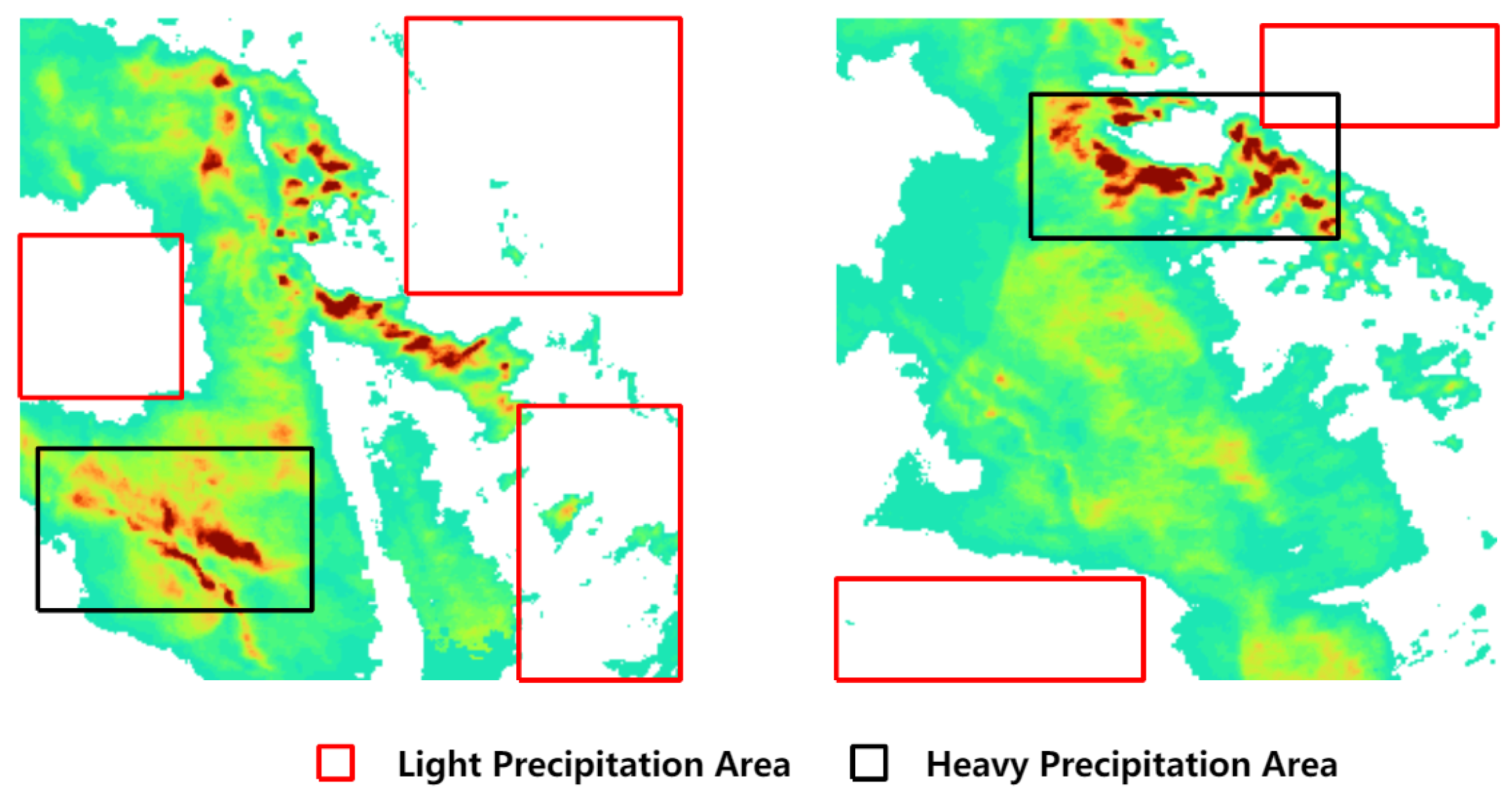

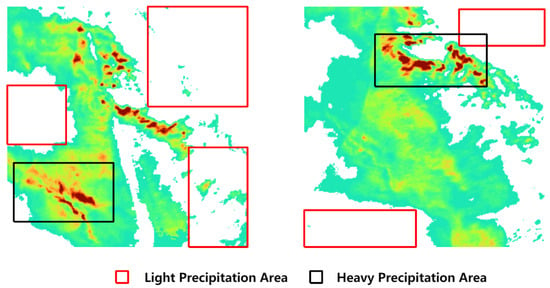

The multi-scale self-attention module in the original TPDTC-Net architecture, while effectively capturing global dependencies through its large receptive field, uniformly processes all feature map regions without adaptive feature selection during information extraction. Although this approach successfully models global relationships, it demonstrates limited effectiveness for precipitation systems characterized by high spatiotemporal heterogeneity. Within a single feature map, meteorological processes typically involve coexisting precipitation-free regions, light precipitation regions, and intense precipitation regions. As demonstrated in Figure 2 illustrates the actual rainfall conditions. To enhance predictive accuracy for high-impact precipitation events, the network should prioritize feature extraction from critical regions (e.g., the black-bounded areas), thereby improving nowcasting accuracy for heavy precipitation scenarios.

Figure 2.

Actual rainfall typically comprises regions of no precipitation, light precipitation, and heavy precipitation concurrently. In the above figure, the red-bounded areas show negligible precipitation activities, whereas the black-bounded areas experience intense precipitation.

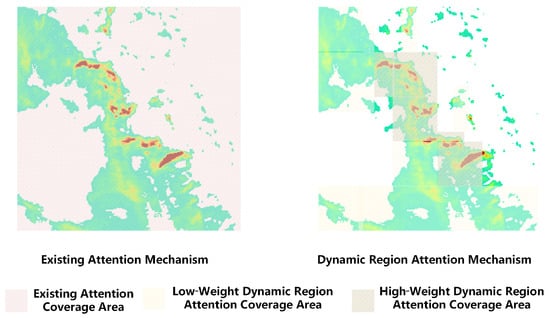

Figure 3 schematically illustrates the dynamic region attention mechanism proposed in this work. The left depicts conventional attention mechanisms that compute pairwise attention values exhaustively across all pixels within the input tensor. While this approach captures global dependencies, it inevitably incurs significant computation on processing non-precipitation regions, resulting in substantial redundancy. The right illustrates our novel dynamic region attention mechanism. This mechanism employs a dynamic region module to generate a mask matrix that is element-wise multiplied with the input feature map. This operation restricts attention computation exclusively to precipitation-containing regions, thereby eliminating computations over non-precipitation regions. Crucially, a weight control module adaptively re-calibrates regional attention weights based on the intensity of precipitation. In the figure, darker colors indicate higher weights assigned to the corresponding regions, guiding the network to focus more on these regions to improve the prediction accuracy of high-intensity precipitation.

Figure 3.

The figure above presents a comparison between the traditional attention mechanism (left) and the dynamic region attention mechanism (right). While the traditional attention spans the entire domain, the dynamic version focuses only on precipitation regions, assigning high weights to areas of intense rainfall during the attention computation.

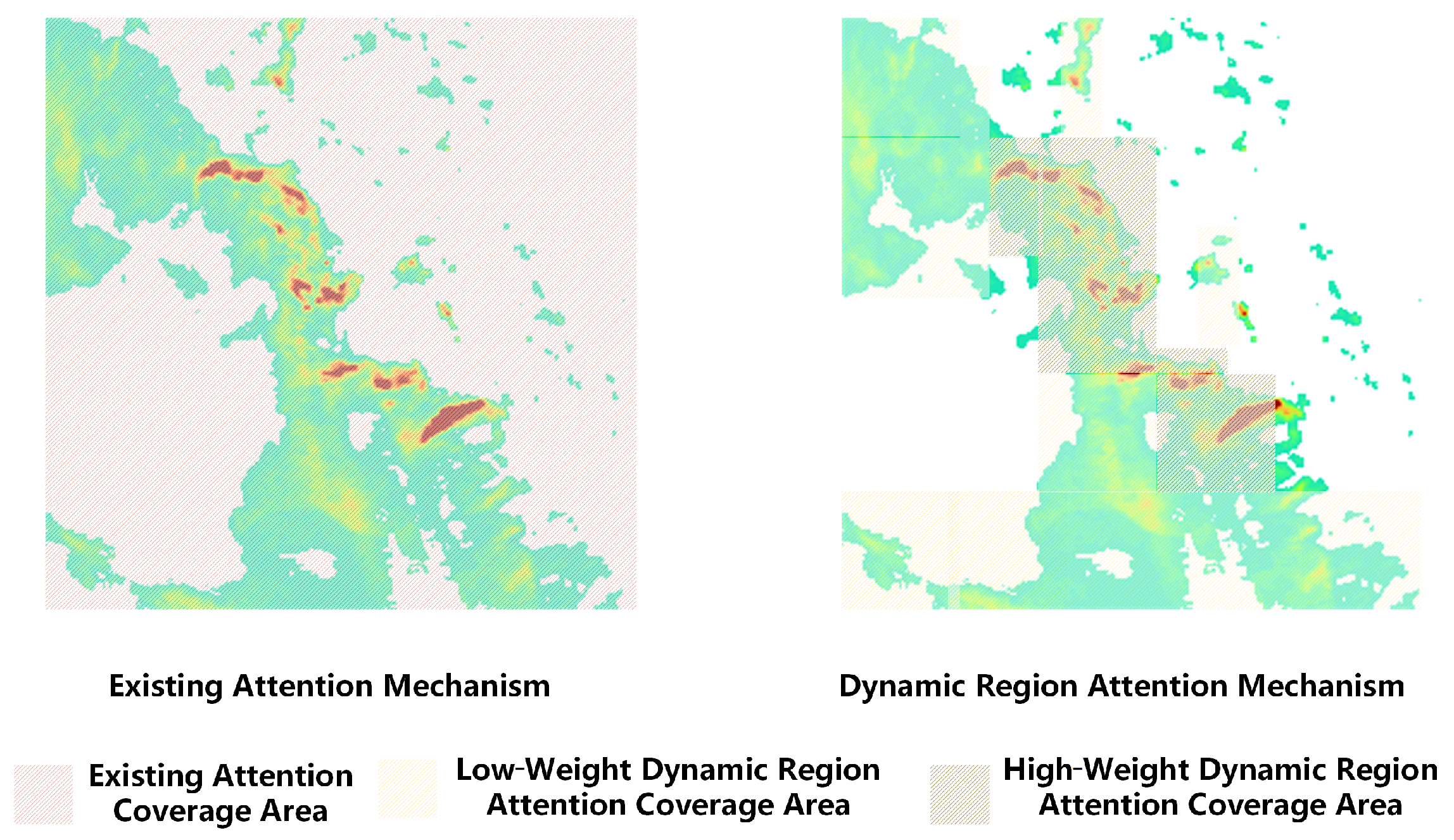

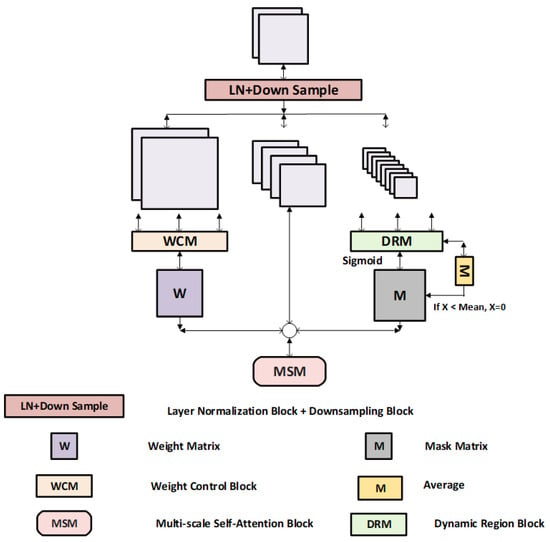

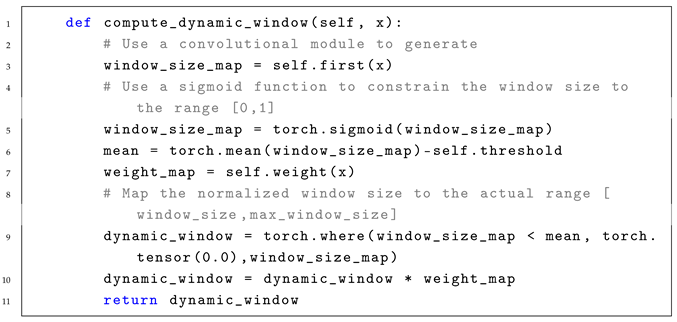

The DRA module proposed in this paper is based on the multi-scale self-attention module in TPDTC-Net, which is further extended by adding the DRM and the WCM, and the structure is shown in Figure 4. The DRM controls the focus of the attention mechanism by generating a mask matrix to ensure that the network can focus on the precipitation region. The WCM automatically adjusts the weights of each region, enabling the model to focus more on the regions with strong precipitation while capturing both global and local features. Specifically, the DRA module divides the feature maps of the three scales into three branches: one without any processing, one for generating the weight matrix, and one for generating the mask matrix. In the leftmost branch, the feature map is input to the weight control module to get the specific weight of each point. In the rightmost branch, the feature map is first fed into the dynamic region module to generate a base mask matrix. This matrix reflects the level of importance of each region. To ensure that the values of the mask matrix are within a reasonable range, it is compressed to the interval [0, 1] using a Sigmoid activation function, yielding matrix Z. Subsequently, the mean value M of the base mask matrix is computed, which serves as a global reference for this matrix. Each element in Z is then compared against M. If the value of a point in Z is less than M, the precipitation at that location is considered to be low and not enough to attract the attention of the network. Therefore, the value of the corresponding location in Z is set to 0, effectively excluding that region from attention computation and suppressing the network’s focus there. Finally, the outputs from all three branches are integrated by element-wise multiplication. This operation weights the original feature map according to the refined mask matrix Z and the weight matrix, producing a weighted dynamic region feature map. Attention computation is then performed specifically on this weighted feature map. The mathematical formulation of DRA module is as follows:

where X denotes the input of the model. Down represents the downsampling layer. LN indicates the layer normalization module. corresponds to the base mask matrix. signifies the mask matrix. denotes the mean value of the base mask matrix. The where operator determines whether attention computation is applied at each spatial position, and the implementation code of this hard threshold is provided in Appendix A. represents the weight matrix. indicates the final weighted dynamic regional feature map. Sigmoid is an activation function, while Average is an operation for calculating the mean.

Figure 4.

Schematic structure of the Dynamic Region Attention Module. Mean denotes the mean value of the base mask matrix.

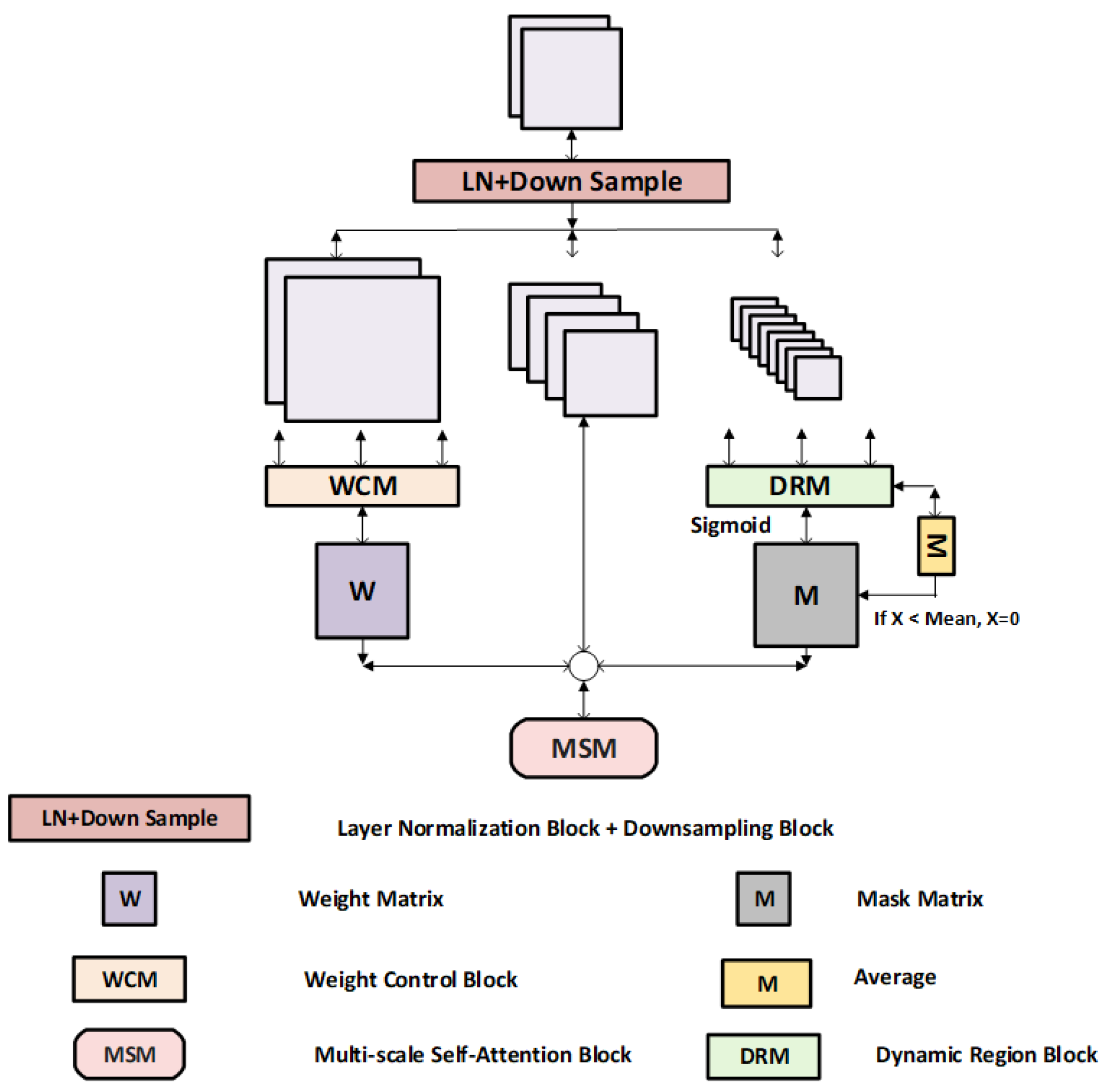

3.3. Dynamic Region Module

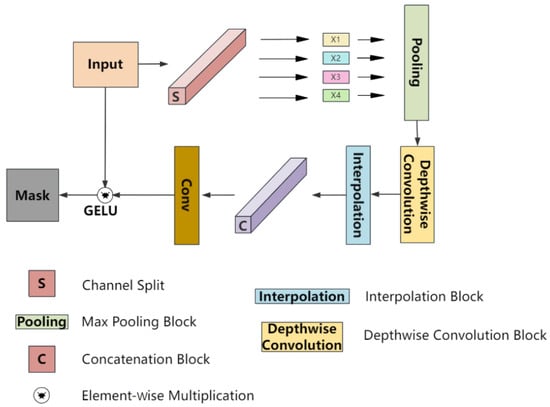

The detailed architecture of the DRM is illustrated in Figure 5. Given precipitation feature maps as input, a channel split operation first divides the data along the channel dimension into four parallel branches, each processing distinct feature information. This branched architecture enables flexible extraction of multi-scale information from precipitation features while adapting to spatial variations in precipitation distribution. Within each split branch, multi-scale max pooling is applied with downsampling ratios of for , for , and for . Given with dimensions , the pooled dimensions become , , and . This multi-scale extraction mechanism enhances the perception of precipitation variations at different resolutions, thereby improving the identification of key learning regions. Subsequently, a separable depthwise convolution is applied to each pooled branch for feature extraction. This operation processes channel features independently, reducing computational load and parameter count while maintaining the feature extraction capability. The processed feature maps are then upsampled to the original spatial resolution via interpolation, enabling cross-scale feature alignment and fusion. Features extracted from different scales are concatenated to integrate multi-scale information. The concatenated feature map preserves both local details and global patterns, ensuring comprehensive coverage of precipitation regions in the generated mask matrix. Finally, the concatenated output is processed through convolutional consolidation to generate a unified multi-scale regional mask matrix.

Figure 5.

Schematic structure of the dynamic area module. The input image is processed by the DRM to generate a regional mask matrix that integrates multi-scale information and comprehensively covers all precipitation areas.

The specific equations for this module are as follows:

where Inp denotes the module input; Split refers to the channel-wise split operation; DWConv stands for depthwise separable convolution; Pooling indicates max pooling; Interpolation denotes the upsampling operation; Concat represents the concatenation step; and Mask is the final output mask matrix.

3.4. Weight Control Module

In addition to the DRM, we propose the WCM to further enhance the network’s sensitivity to high-intensity precipitation regions. This module dynamically adjusts the weights assigned to different precipitation regions, ensuring the model allocates greater attention to heavy precipitation regions during processing, thereby improving prediction accuracy.

Specifically, the WCM automatically adjusts the weights for each region based on the precipitation intensity within the input data. For regions with higher precipitation intensity, the weights are dynamically increased, forcing the network to concentrate its attention on these areas and further improving prediction precision for heavy precipitation events. Conversely, regions with light precipitation are assigned suppressed weights to prevent the network from overemphasizing less critical parts.

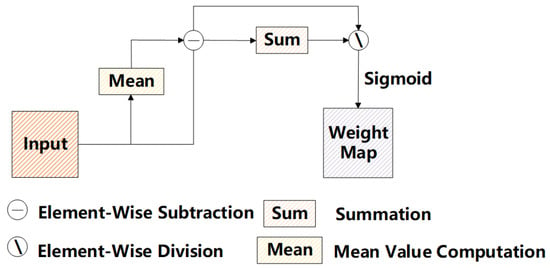

A schematic diagram of the WCM is shown in Figure 6. When processing the input precipitation feature map, the module first calculates the squared difference between each pixel and the mean value of its respective channel (along the height h and width w dimensions). This step aims to quantify the deviation of each pixel from the channel mean, thereby identifying regions exhibiting significant variation within the feature map, which typically correspond to heavy precipitation or other salient features. Subsequently, for each channel, the sum of squared differences across its spatial dimensions (i.e., height and width) is computed. This yields the total squared difference per channel, reflecting the overall variation within that channel. The resulting matrix y is then passed through a Sigmoid activation function, normalizing each value to the range [0, 1]. This ensures the generated weight values are smooth and stable. These weights are applied during the feature map weighting process. The regions corresponding to heavy precipitation receive higher weights, while the regions with less precipitation receive lower weights.

Figure 6.

Schematic structure of the weight control module.

By dynamically generating attention weights based on local variations within the input feature map, the WCM enables the neural network to prioritize regions of heavy precipitation while suppressing attention to regions with lighter precipitation. This enhancement effectively reduces interference from non-precipitating or low-precipitation areas, thus improving the model’s prediction accuracy in regions experiencing heavy precipitation.

3.5. Loss Function

Considering the characteristics of the dataset (as shown in Table 1), this paper adopts a weighted loss function with balanced mean squared error (BMSE). Here, the traditional mean squared error (MSE) serves as the baseline loss function, defined as follows:

where F denotes the total number of image frames, and H and W represent the height and width of the image, respectively. and correspond to the predicted value and observed value at the position .

Table 1.

Probability distribution table for precipitation in the dataset.

As shown in Table 1, the distribution of precipitation intensity in the dataset exhibits significant imbalance. To address this issue, a weighted loss function is adopted in this study. The weights dynamically adapt based on precipitation intensity, defined as follows:

where x represents the cumulative precipitation. The BMSE can be calculated as follows:

where denotes the weight assigned to the pixel at position in frame f. To guarantee fair comparisons across all experiments, BMSE is uniformly adopted as the loss function for all subsequent models.

4. Results

4.1. Datasets

The precipitation data used in this paper for model training and validation were provided by the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI). These data cover precipitation images collected at 5 min intervals over the Netherlands and its surrounding areas from 2016 to 2019. We selected images where at least 50% of the pixels contained precipitation to prevent the network from exhibiting bias toward predictions of zero values. Additionally, the precipitation images were cropped to a uniform size of pixels to reduce computational demands during training. In the precipitation map, each pixel corresponds to a 1 km2 area and represents the accumulated precipitation over the most recent 5 min; the precipitation amount is stored as an integer in units of 0.01 mm. The selected training and validation sets include 5734 sequences, with 80% randomly chosen as the training set and the remaining sequences used as the validation set. The test set contains 1557 sequences. Each sequence consists of 18 image frames.The experiment took 9 frames as input, representing the precipitation pattern over the previous 45 min, and predicted precipitation for the subsequent 45 min.

To normalize the data, the values in both the training and test sets were divided by the maximum value observed in the training set. The calculation is as follows, where x represents the original data and max is the highest value among all data:

4.2. Implementation Details

The proposed TPDTC-Net-DRA model processes a 9-channel input and generates a 9-channel output. Both the encoder and decoder employ a three-level hierarchical architecture, containing 5, 6, and 6 DRA layers at each level, respectively. At the end of each level of the encoder, downsampling operations are performed to progressively increase the dimensions of the feature maps. The temporal predictor integrates 6 layers of Fourier self-attention blocks.

The hardware environment for the experiments in this study was a high-performance server equipped with Intel(R) Xeon(R) Gold 6430 CPU, 120 GB of memory, and an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU. The software environment included the Ubuntu 20.04 operating system, with CUDA 12.1, Python 3.10, and PyTorch 2.1.0 installed. During model training, the optimizer was Adam, with an initial learning rate of 0.0002, and the learning rate decayed to 0.9 of its previous value every 4 epochs. The batch size was set to 2 for the KNMI dataset.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

This experiment employed four metrics to quantitatively evaluate the performance of the precipitation nowcasting network: the critical success index (CSI), the Heidke skill score (HSS), BMSE, and the balanced mean absolute error (BMAE).

4.3.1. CSI

CSI measures the ratio of correctly predicted events (e.g., precipitation) to the total number of predicted events and the total number of actual events, while also accounting for the impact of false alarms. It is used to assess the ability of a forecasting system to capture specific weather events (e.g., the occurrence of precipitation). The formula is as follows:

In this formula, TP represents the number of grid points where both observed and predicted precipitation exceed the threshold. FP represents the number of grid points where observed precipitation is below the threshold but predicted precipitation exceeds it. FN represents the number of grid points where observed precipitation exceeds the threshold but predicted precipitation does not.

4.3.2. HSS

HSS is an indicator for evaluating forecast skill. It considers both correct and incorrect predictions and is typically used to assess whether a forecasting system performs better than a random forecast. Unlike CSI, HSS incorporates a baseline for random forecasts during calculation, i.e., it compares actual forecasts with purely random forecasts. The formula is as follows:

where TN represents the number of grid points where both observed and predicted precipitation are below the threshold.

4.3.3. BMSE

BMSE is used to evaluate the error between predicted and true values. The specific formula is as follows:

where n is the total number of samples, is the weight corresponding to each pixel, represents the absolute value operation, is the predicted value, and is the true value.

4.3.4. BMAE

BMAE is an evaluation metric used to assess the predictive performance of regression models. It is a weighted version of the mean absolute error (MAE), which balances the influence of different samples on model predictions by assigning different weights to the errors of individual samples. The formula is as follows:

4.4. Comparison with State-of-the-Art Methods

Table 2 provides a quantitative comparison of prediction results across different models. In this paper, the model output 5 min accumulated precipitation. For evaluation, the accumulated amounts were converted into an equivalent hourly precipitation intensity r (mm/h) using a unified physical conversion. Heavy precipitation was defined as mm/h. The results demonstrate that TPDTC-Net-DRA outperformes the previous TPDTC-Net model on the two key evaluation metrics, CSI and HSS, achieving notable improvements. This advantage is attributed to the dynamic region attention method proposed in this paper. This method enables the network to focus more effectively on precipitation regions, extract richer precipitation features, and better capture the interactions between precipitation events.

Table 2.

Quantitative Comparison Results of TPDTC-Net-DRA on the KNMI Dataset.

As shown in Table 2, it can be observed that TPDTC-Net-DRA achieves significant performance improvements across all thresholds. The enhanced prediction capability for light precipitation is primarily attributed to the powerful multi-scale feature extraction capability of TPDTC-Net, which enables effective capture of precipitation patterns at various spatial scales. The introduction of the DRA mechanism further enhances the model’s ability to suppress interference from redundant information and focus on key features within precipitation regions, thereby avoiding excessive computation in irrelevant regions. By strengthening the network’s focus on precipitation-related regions, it becomes more capable of accurately extracting global multi-scale features associated with precipitation, which substantially improves its prediction performance under light precipitation scenarios. Moreover, light precipitation is generally characterized by relatively stable and uniform distributions, making it inherently more predictable. As a result, by concentrating on critical regions, the network’s predictive accuracy is significantly enhanced.

The improvement in the prediction capability of TPDTC-Net-DRA under heavy precipitation scenarios stems primarily from the focusing and weighting within the dynamic region attention mechanism. By generating a mask matrix, the DRA mechanism ensures that the attention process is constrained to precipitation regions, effectively avoiding unnecessary computations in non-precipitation regions and allowing the model to concentrate on the most critical areas. During this process, the multi-scale self-attention feature extraction module in TPDTC-Net can capture richer and more fine-grained precipitation features within these targeted regions, thereby enhancing the model’s sensitivity to precipitation variations. Moreover, the introduction of the weight control module further amplifies the model’s focus on heavy precipitation regions. Higher weights assigned to heavy precipitation regions ensure their dominant importance in both feature extraction and prediction processes. This dynamic weighting directs the self-attention mechanism to accurately model relationships within heavy precipitation regions, ultimately improving prediction accuracy in such challenging scenarios.

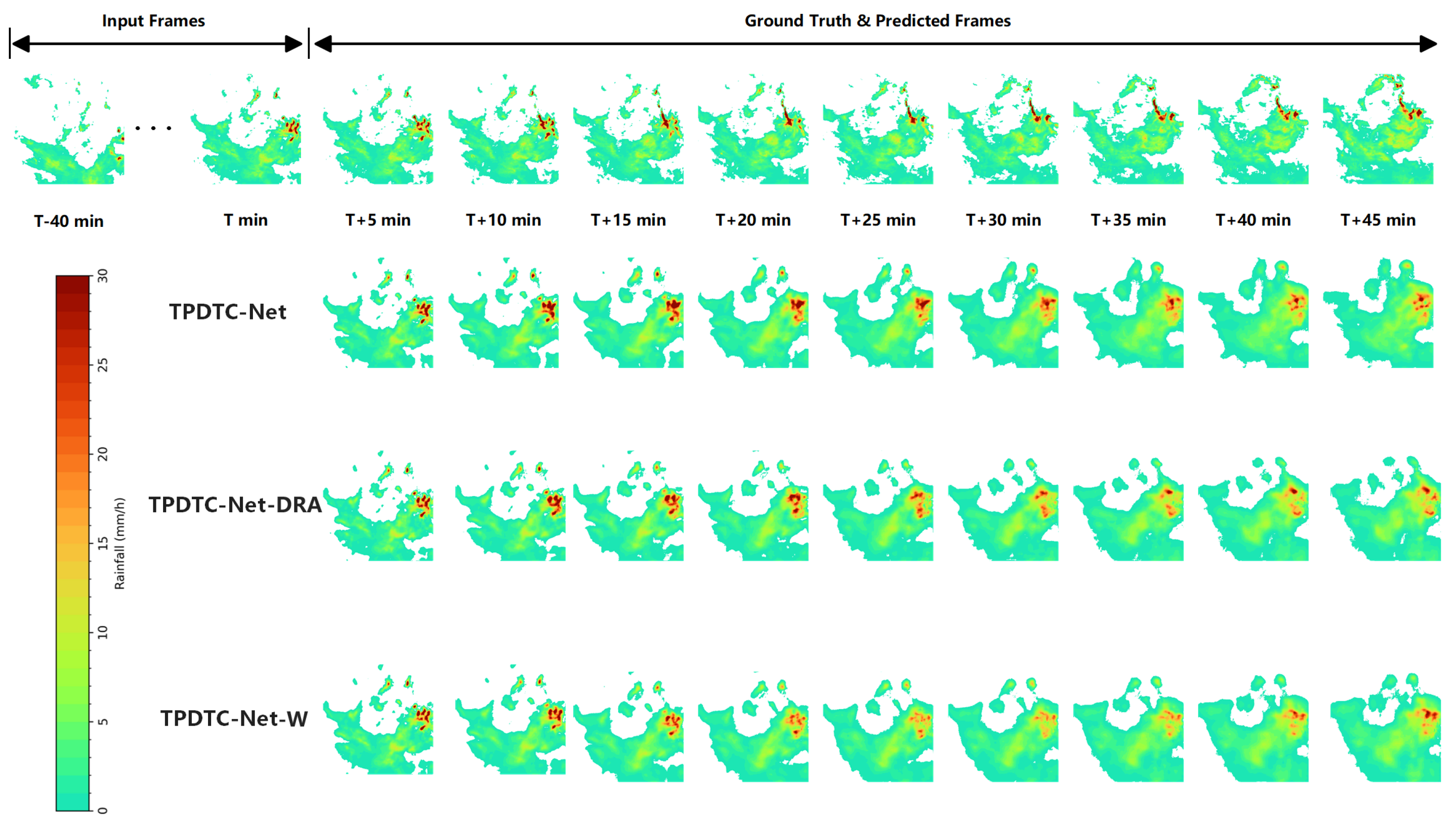

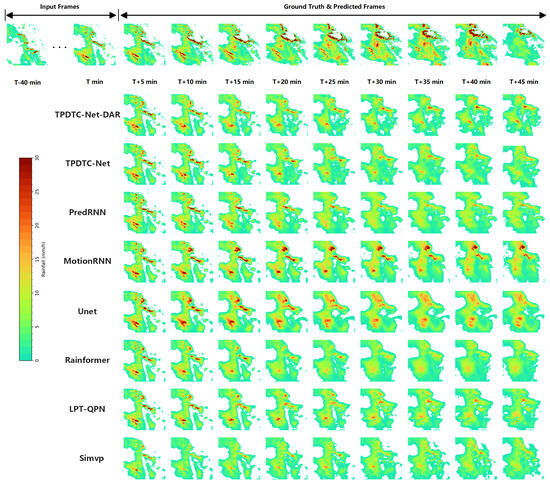

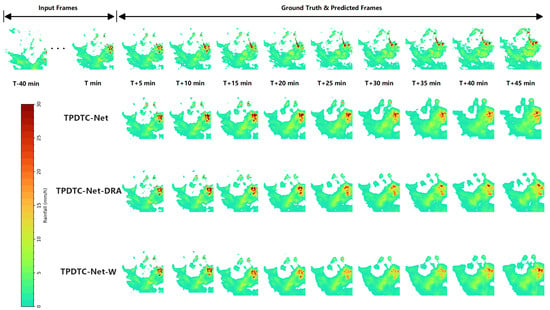

The occurrence of heavy precipitation is typically influenced by multiple factors and is characterized by abrupt and nonlinear changes, which makes it difficult for existing methods to capture its dynamic variations effectively. Despite the high complexity and uncertainty associated with heavy precipitation scenarios, which pose significant challenges for prediction, TPDTC-Net-DRA achieves substantial performance improvements under such extreme weather conditions, outperforming all baseline methods and highlighting its effectiveness and potential. Figure 7 provides a visual comparison of prediction results between TPDTC-Net-DRA and other models on the KNMI dataset. The results indicate that TPDTC-Net-DRA exhibits superior predictive capability for heavy precipitation events, especially in later forecast frames, compared to TPDTC-Net. In particular, TPDTC-Net-DRA more accurately captures the intensity variations during heavy precipitation events, making the predictions more consistent with the ground truth. Additionally, TPDTC-Net-DRA demonstrates superior coverage of precipitation regions. It not only accurately forecasts regions of heavy precipitation but also effectively models moderate to light precipitation in central regions. This leads to a significant reduction in the discrepancy between the predicted results and the actual observations. Compared to the other models, TPDTC-Net-DRA captures precipitation distribution and intensity better, enabling the network to effectively learn regional precipitation characteristics. This capability is especially valuable under complex meteorological conditions, where the model exhibits enhanced prediction accuracy.

Figure 7.

Visual Comparison of TPDTC-Net-DRA and State-of-the-Art Methods. A precipitation sequence is composed of nine consecutive frames captured at 5 min intervals; darker shades in the images denote higher precipitation rates. T represents the current moment. The time from T-40 to T corresponds to the previous nine frames of images, while the time from T + 5 to T + 45 corresponds to the predicted images of the subsequent nine frames.

In summary, TPDTC-Net-DRA significantly enhances the model’s performance by introducing the DRA mechanism. This approach enables the model to demonstrate enhanced predictive capabilities under varying intensities of precipitation, achieving notable progress in both light and heavy precipitation scenarios. For light precipitation, the dynamic attention mechanism helps the network focus on the precipitation regions, thereby improving prediction accuracy. In heavy precipitation scenarios, the combination with the weight control module allows the model to assign higher weights to regions with intense precipitation, further enhancing its ability to predict high-intensity precipitation.

4.5. Plug-and-Play Dynamic Region Attention Mechanism

This subsection designed experiments to validate the effectiveness of the DRA mechanism proposed in this work, especially under heavy precipitation conditions. The experiments investigated whether integrating the DRA mechanism generally enhances model performance and boosts the prediction accuracy of diverse model architectures when applied to other fundamental feature extraction methods (e.g., convolutional operations, self-attention).

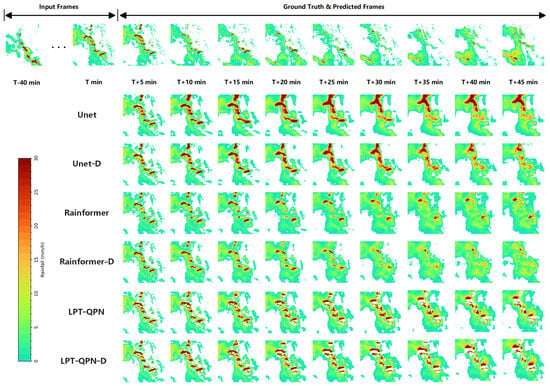

In particular, this subsection applied the DRA mechanism to three typical model architectures: Unet, Rainformer, and LPT-QPN [58]. These models utilize different feature extraction methods: Unet employs traditional convolutional operations for feature extraction; Rainformer uses Swin Transformer operations to extract both global and local features of images; and LPT-QPN [58] uses multi-head square attention for feature extraction. The experiments focused on comparing the performance of these different models in the precipitation nowcasting task, exploring whether the DRA mechanism can universally improve model performance across various feature extraction methods, and further enhance the prediction capability for areas with higher precipitation intensity. Table 3 presents the quantitative evaluation results of all models on the KNMI dataset. The models Unet-D, Rainformer-D, and LPT-QPN-D represent the three models incorporated with the DRA mechanism.

Table 3.

Quantitative Comparison Results on the KNMI Dataset After Adding the DRA module.

Through the comparison between Unet and Unet-D in Table 3, it is evident that adding the DRA mechanism improves the prediction performance of Unet. However, the improvements are more pronounced for high-intensity precipitation than for low-intensity events. This differential improvement primarily stems from two perspectives. Firstly, the DRA mechanism enhances focus on precipitation regions but fails to account for the inherent constraints of convolutional operations. Convolutional layers have limited receptive fields, which are specialized for local feature extraction but fundamentally restrict their ability to capture global dependencies. When the DRA suppresses non-precipitation or light-precipitation regions, the overall features learned through convolution may be adversely affected, thereby limiting significant improvement in predicting low-intensity precipitation. Secondly, Unet-D demonstrates substantial improvement in high precipitation regions. By aggregating features with higher weights in these regions, the DRA mechanism enhances convolutional feature extraction. High precipitation regions typically exhibit more complex and interdependent spatial structure, and the introduction of the DRA mechanism effectively improves the sensitivity of convolutional operations to these regions, thereby enhancing the prediction accuracy for high-intensity precipitation.

By comparing the results of Rainformer and Rainformer-D in Table 3, a similar trend can be observed. After incorporating the DRA mechanism, the performance shows significant improvement in precipitation prediction when r ≥ 2 mm/h, yielding improvements of 2.71%, 9.87%, 24.46%, and 24.64%, respectively. The greater enhancement in the prediction ability for heavy precipitation compared to light precipitation primarily stems from Rainformer’s Swin Transformer backbone. Although Swin Transformer, compared to traditional convolution methods, has a larger receptive field and can capture more extensive spatial dependencies through self-attention, its original block-wise computation principle still appears small in scale for precipitation nowcasting tasks. The DRA mechanism effectively highlights high-intensity precipitation regions within each block, intensifying attention to these critical areas and substantially boosting heavy precipitation prediction capability. The improvement in light precipitation prediction is also greater for Rainformer-D than Unet-D because the Swin Transformer’s sliding window mechanism, unlike convolutional operations, facilitates effective information exchange between blocks. This cross-block interaction strengthens regional relationships, mitigating the limitations of block-based processing in capturing global features.

The comparison results between LPT-QPN and LPT-QPN-D in Table 3 lead to similar conclusions. After adding the DRA mechanism, the performance in heavy precipitation prediction with r ≥ 10 mm/h improves by 2.25%, 7.99%, and 22.06%, respectively, but no improvement has been observed in the prediction for light precipitation. The improvement can be attributed to the fact that LPT-QPN [58] uses a multi-head square attention operation for feature extraction. After the introduction of the DRA mechanism, the weights in the heavy precipitation regions are increased, directing attention toward high-intensity features and effectively boosting prediction capability.

Figure 8 shows the visualization results of the models mentioned above. It can be observed that after adding the DRA mechanism, the network’s prediction ability for heavy precipitation is significantly improved. For instance, UNet-D generates sharper delineation and improved positional accuracy of heavy precipitation regions compared to UNet (as seen in the upper-right corner of the prediction image). Rainformer-D and LPT-QPN-D also achieve more accurate predictions.

Figure 8.

Visualization After Adding Dynamic Region Attention Mechanism. A precipitation sequence is composed of nine consecutive frames captured at 5 min intervals; darker shades in the images denote higher precipitation rates.

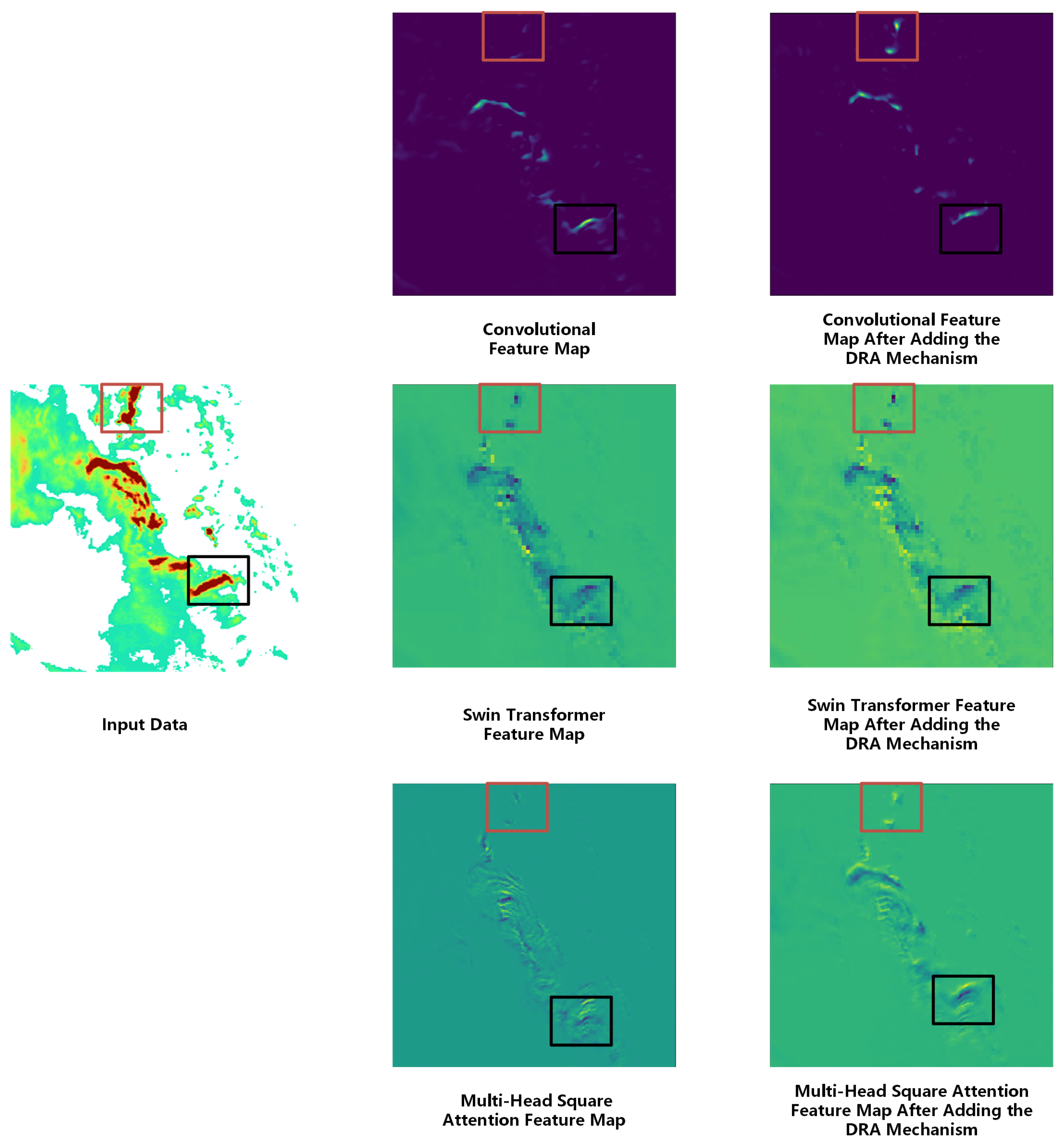

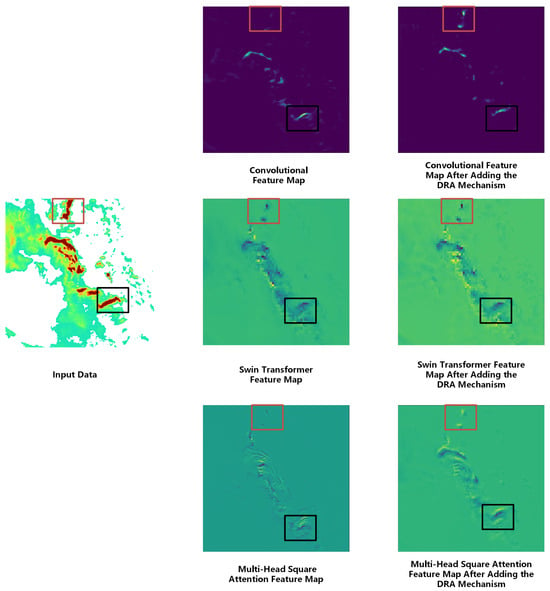

To more intuitively demonstrate the effectiveness of the DRA mechanism proposed in this paper, Figure 9 shows the feature maps generated by different feature extraction methods. In the input data, the two regions marked by red and black boxes represent two heavy precipitation areas. By comparing the highlighted regions in the feature maps on the right, it is evident that after adding the DRA mechanism, each feature extraction method shows more noticeable attention to the heavy precipitation regions in the feature maps through the focusing and weighting operations, extracting richer features of heavy precipitation.

Figure 9.

Feature visualization comparison across three different extraction strategies. The leftmost panel shows the input data, in which the two regions marked by red and black boxes indicate intense precipitation areas. The two rightmost columns correspond to the input, with the first column displaying feature maps obtained by the existing extraction method and the second column showing the maps after the dynamic attention mechanism is added.

4.6. Validation of Weight Control Module

In the previous subsection, the effectiveness of the DRA mechanism proposed in this paper was validated. To further validate the idea of adding weights to the feature maps, this subsection designed the TPDTC-Net-DRA-W (abbreviated as TPDTC-Net-W) model for comparison experiments. In TPDTC-Net-W, the WCM is not employed. Instead, after dividing the dynamic region attentions, the attention values are directly computed.

Table 4 presents the quantitative evaluation results of TPDTC-Net-W. It can be observed that compared to TPDTC-Net-DRA, TPDTC-Net-W exhibits a significant decline in prediction capability under heavy precipitation conditions. This is primarily because, after the feature maps are covered by the mask matrix, only the feature data of precipitation regions are retained, without further enhancing the attention to these areas. Without dynamically adjusting the weights of heavy precipitation regions through the weight control module, the network becomes inadequate in feature extraction for these regions. Heavy precipitation regions typically exhibit highly nonlinear and complex spatial variations. Therefore, merely covering the features of precipitation regions with a mask matrix without strengthening the focus on these critical areas results in insufficient sensitivity of the network in capturing heavy precipitation features. Additionally, heavy precipitation itself, as a meteorological phenomenon characterized by suddenness, rapid changes, and high uncertainty, poses significant challenges for prediction. Without proper weight guidance, the model tends to overlook detailed information in these important regions, which not only reduces prediction accuracy but also makes heavy precipitation forecasting more difficult. Thus, the performance decline of TPDTC-Net-W under heavy precipitation scenarios further demonstrates the critical role of the weight control module in helping the model focus on key precipitation regions and improving prediction accuracy.

Table 4.

The comparative experiment table of TPDTC-Net-DRA on the KNMI dataset.

However, the results in Table 4 also show that the prediction capability of TPDTC-Net-W under weak precipitation conditions declines only slightly compared to TPDTC-Net-DRA. This is because weak precipitation regions have lower precipitation intensity and more uniform distribution, so even without the assistance of the weight control module, the model can still capture precipitation features and make predictions relatively accurately. In weak precipitation regions, the variations in precipitation are more gradual, and the precipitation amounts are smaller, making features easier to extract. Moreover, weak precipitation regions typically do not exhibit complex local variations, allowing the network to perform reasonably well without relying on dynamic weight adjustments. Figure 10 shows the visualization results of the comparative experiments, from which it can be observed that TPDTC-Net-W’s prediction capability for heavy precipitation is inferior to that of TPDTC-Net and TPDTC-Net-DRA.

Figure 10.

Visualization of TPDTC-Net-W Results. A precipitation sequence is composed of nine consecutive frames captured at 5 min intervals; darker shades in the images denote higher precipitation rates.

5. Discussion

5.1. The Analysis of Data Preprocessing

Considering the model’s computational cost and convergence efficiency, data preprocessing was applied in this study. As mentioned in Section 4.1, we applied a filtering criterion requiring that at least 50% of pixels in the training samples contain precipitation on the KNMI dataset. This operation indeed alters the natural ratio between precipitation and non-precipitation cases and may affect the model’s adaptability to real operational scenarios dominated by non-precipitation or weak-precipitation conditions. However, the primary motivation for this filtering strategy was to ensure that, under limited computational resources, the model could effectively learn the evolution characteristics of precipitation systems, while avoiding convergence difficulties or an excessive bias toward predicting no precipitation in extremely imbalanced datasets, and at the same time accelerating model convergence. The current experimental results were obtained based on samples with relatively high precipitation coverage. In future work, we will further explore the use of mutual information based reweighting (MIR) [59], sample weighting based on mean accumulated volatility (MAV) [60], or deep generative models (DGMs) [44] to learn the underlying probability distribution of the data and to investigate the effectiveness of the proposed model under scenarios dominated by no-precipitation or weak-precipitation.

5.2. The Applicability of DRA Mechanism

As shown in Section 4.5, the experiments effectively demonstrated the effectiveness and generalizability of the DRA mechanism proposed in this paper. This approach not only enhances the prediction performance of the previously proposed TPDTC-Net but can also be combined with other feature extraction methods to improve the model’s capability for heavy precipitation.

It should be noted that in the ablation experiments in Section 5.2, we deliberately selected representative non-autoregressive backbone networks that already incorporate attention mechanisms. This decision was made to isolate and evaluate the independent contribution of DRA in regional modeling and feature re-calibration. By validating the effectiveness of DRA under relatively strong baseline conditions, we avoid attributing performance gains merely to the introduction of attention mechanisms, thereby enabling a more objective assessment of DRA.

Although the current study primarily considers the application of DRA to non-autoregressive networks, it is worth noting that DRA is composed of a Dynamic Region Module (DRM) and a Weight Control Module (WCM), and operates on intermediate feature tensors through spatial mask and weight generation for point-wise feature modulation and re-calibration. This process takes place in the feature space and is independent of whether the features are produced by convolutional networks, Transformers, or recurrent units. Future work will systematically extend DRA to purely recurrent networks to evaluate its effectiveness and generalization capability in autoregressive temporal modeling.

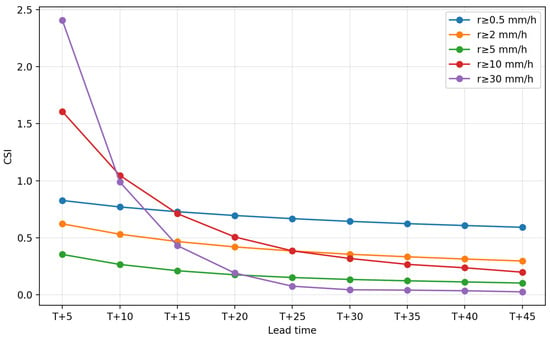

5.3. Error Decomposition: The Temporal Extent of DRA Improvement

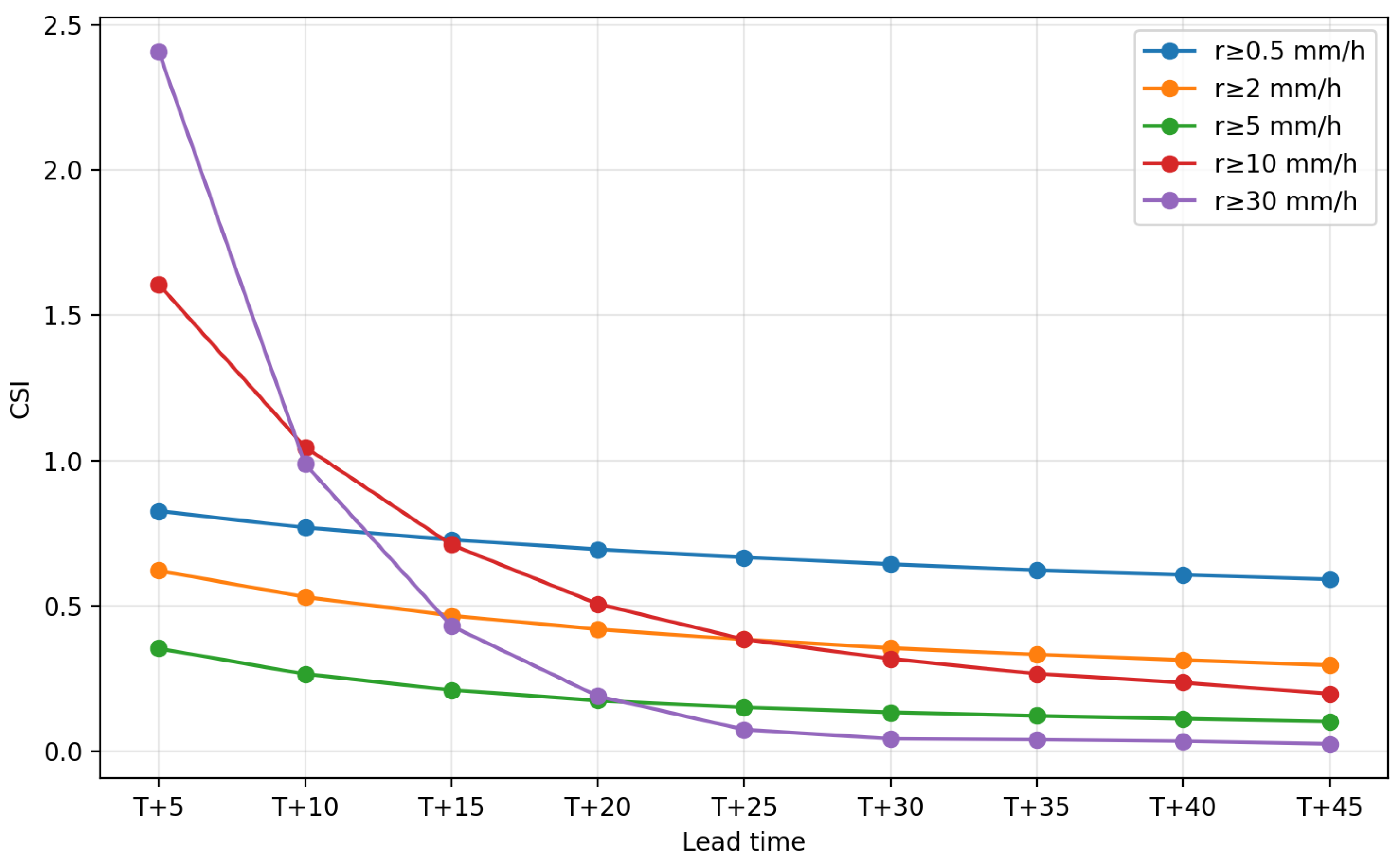

In this paper, we conducted a segmented statistical analysis of CSI at 5 min intervals under different precipitation intensity thresholds, with particular emphasis on heavy precipitation ( mm/h) on the KNMI dataset.

As shown in the Figure 11, the model exhibits relatively stable performance under the overall precipitation forecasting condition ( mm/h) on the test set. Under heavy precipitation conditions ( mm/h), the model achieves strong predictive performance, particularly within a lead-time window of approximately 5–25 min. Although the gains brought by the additional attention mechanism gradually diminish at longer lead times (roughly beyond T + 25), our method still substantially outperforms the baseline approaches [27]. For the more extreme threshold ( mm/h), the effectiveness is mainly concentrated within the short-term forecasting window of approximately 5–25 min, while at longer lead times (around after T + 30), the additional gains brought by attention gradually diminish, this may be related to the greater scarcity of extreme precipitation samples and the accumulated uncertainty resulting from the increased forecast lead time.

Figure 11.

CSI vs. lead time (5 min steps) for precipitation. Similarly, for the sake of easier comparison, the results with mm/h will be multiplied by 10, and the results with mm/h will be multiplied by 100.

5.4. Statistical Significance: Bootstrap Confidence Intervals for CSI/HSS Differences

In this paper, we employed a bootstrap procedure to compute the 95% confidence intervals for the CSI/HSS differences as shown in Table 5, and conducted a detailed analysis across different precipitation intensity thresholds on the KNMI dataset.

Table 5.

Confidence intervals of the CSI and HSS under different precipitation intensity thresholds.

Under the overall precipitation condition ( mm/h), HSS in the original paper did not exhibit a clear improvement, and the corresponding 95% confidence interval of the difference is entirely negative and does not include positive gains. In contrast, under moderate to heavy precipitation thresholds ( mm/h), both CSI and HSS differences show positive mean values, with 95% confidence intervals that do not include zero, indicating statistically significant performance improvements. For extreme heavy precipitation ( mm/h), the HSS result is only second-best, and its 95% confidence interval covers zero, suggesting that the observed performance difference at this threshold may be attributable to sampling noise rather than a stable and statistically significant improvement. This behavior is consistent with the limited number of extreme precipitation samples and the accumulation of predictive uncertainty at longer lead times. From this perspective, the advantages of our method are mainly manifested in the precipitation intensity range of 2, 5, 10 mm/h.

6. Conclusions

This paper presents a novel plug-and-play DRA mechanism, and a precipitation nowcasting method TPDTC-Net-DRA, which integrates the DRA mechanism into our previously introduced spatiotemporal feature decoupling network TPDTC-Net to enhance nowcasting performance, especially under heavy precipitation conditions. The DRA mechanism introduces two new key modules, the DRM and the WCM. The DRA employs a DRM to generate a mask matrix that constrains attention computation to precipitation regions. Additionally, the WCM generates a weight matrix to guide the neural network to focus more on high precipitation regions. Experimental results demonstrate that the DRA mechanism effectively guides TPDTC-Net-DRA and other architectures (e.g., UNet, Rainformer, LPT-QPN) to focus on heavy precipitation regions, significantly enhancing their nowcasting performance, particularly for heavy precipitation events. Deployment requires real-time radar quality control and human-in-the-loop interpretation before civil protection actions.

Despite the significant advancements achieved by the DRA mechanism and TPDTC-Net-DRA, there are still several issues that need to be addressed in future research. Firstly, our results are primarily validated on the KNMI dataset, and cross-region/cross-dataset generalization still requires further empirical assessment. In future work, we will prioritize experiments on at least one additional public radar dataset. Secondly, the current design of the loss function has limitations, leading to overly smooth predicted results. To address this issue, future research will focus on improving the loss function to generate clearer and more detailed nowcasting results. Additionally, we plan to explore the possibility of integrating generative models, such as diffusion models. Furthermore, while improving the accuracy and reliability of precipitation nowcasting, quantifying its associated uncertainty will also be a crucial part of our future work. Finally, the construction of DRA relies primarily on instantaneous radar reflectivity fields, and the characterization of the environmental physical information of precipitation systems (e.g., convective available potential energy (CAPE) and wind shear) remains relatively limited. As a result, there is still room for further improvement in learning the underlying physical mechanisms. Future work will extend the mask generation mechanism of DRA from a multi-source meteorological data fusion perspective to obtain dynamic masks with stronger physical constraints and improved robustness.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Q., C.D. and J.L. (Jia Liu); Methodology, X.Q., C.D. and J.L. (Jia Liu); Software, X.Q. and C.D.; Validation, X.Q. and C.D.; Formal analysis, X.Q., C.D. and J.L. (Jia Liu); Investigation, X.Q., C.D. and J.L. (Jia Liu); Resources, J.L.; Data curation, X.Q. and C.D.; Writing—original draft, X.Q., C.D. and J.L. (Jia Liu); Writing—review & editing, X.Q., Y.D., C.D., J.L. (Jiang Liu), J.L. (Jia Liu), K.D. and X.W.; Visualization, C.D.; Supervision, J.L. (Jia Liu); Project administration, J.L. (Jia Liu); Funding acquisition, J.L. (Jia Liu). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 62372460, and in part by the Key Laboratory of Smart Earth under Grant KF2023YB03-09.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Koninklijk Nederlands Meteorologisch Instituut and Tianchi Laboratory, Shenzhen, China for freely providing the precipitation data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Pseudo-Code of the Hard Thresholding

| Listing A1. Hard threshold version. |

|

References

- Gimeno, L.; Sorí, R.; Vazquez, M.; Stojanovic, M.; Algarra, I.; Eiras-Barca, J.; Gimeno-Sotelo, L.; Nieto, R. Extreme precipitation events. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Water 2022, 9, e1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahabi-Abed, S.; Ayugi, B.O.; Selmane, A.N.E.I. Spatiotemporal projections of extreme precipitation over Algeria based on CMIP6 global climate models. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2023, 9, 3011–3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Li, X.; Ye, Y. PFST-LSTM: A spatiotemporal LSTM model with pseudoflow prediction for precipitation nowcasting. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2020, 14, 843–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenzweig, C.; Tubiello, F.N.; Goldberg, R.; Mills, E.; Bloomfield, J. Increased crop damage in the US from excess precipitation under climate change. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2002, 12, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iizumi, T.; Iseki, K.; Ikazaki, K.; Sakai, T.; Shiogama, H.; Imada, Y.; Batieno, B.J. Increasing heavy rainfall events and associated excessive soil water threaten a protein-source legume in dry environments of West Africa. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2024, 344, 109783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xu, L.; Chen, N. A spatiotemporal deep learning model ST-LSTM-SA for hourly rainfall forecasting using radar echo images. J. Hydrol. 2022, 609, 127748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnbjerg-Nielsen, K.; Willems, P.; Olsson, J.; Beecham, S.; Pathirana, A.; Bülow Gregersen, I.; Madsen, H.; Nguyen, V.T.V. Impacts of climate change on rainfall extremes and urban drainage systems: A review. Water Sci. Technol. 2013, 68, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willems, P.; Arnbjerg-Nielsen, K.; Olsson, J.; Nguyen, V.T.V. Climate change impact assessment on urban rainfall extremes and urban drainage: Methods and shortcomings. Atmos. Res. 2012, 103, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.W.; Peng, Z.R.; Wang, D.; Meng, Y.; Wu, T.; Sun, W.; Lu, Q.C. Evaluation and prediction of transportation resilience under extreme weather events: A diffusion graph convolutional approach. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2020, 115, 102619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, D. The mixed effects of precipitation on traffic crashes. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2004, 36, 637–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Yang, S.; Wang, W.; Zhang, X. Impact analysis of highways in China under future extreme precipitation. Nat. Hazards 2022, 110, 1097–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanBuskirk, O.; Ćwik, P.; McPherson, R.A.; Lazrus, H.; Martin, E.; Kuster, C.; Mullens, E. Listening to stakeholders: Initiating research on subseasonal-to-seasonal heavy precipitation events in the contiguous United States by first understanding what stakeholders need. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2021, 102, E1972–E1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Xue, M.; Wilson, J.W.; Zawadzki, I.; Ballard, S.P.; Onvlee-Hooimeyer, J.; Joe, P.; Barker, D.M.; Li, P.W.; Golding, B.; et al. Use of NWP for nowcasting convective precipitation: Recent progress and challenges. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2014, 95, 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayzel, G.; Heistermann, M.; Winterrath, T. Optical flow models as an open benchmark for radar-based precipitation nowcasting (rainymotion v0. 1). Geosci. Model Dev. 2019, 12, 1387–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, R. Numerical weather prediction. J. Wind. Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2002, 90, 1403–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Shen, X. On the development of the GRAPES—A new generation of the national operational NWP system in China. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2008, 53, 3429–3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skamarock, W.C.; Klemp, J.B.; Dudhia, J.; Gill, D.O.; Liu, Z.; Berner, J.; Wang, W.; Powers, J.G.; Duda, M.G.; Barker, D.M.; et al. A description of the advanced research WRF model version 4. Natl. Cent. Atmos. Res. 2019, 145, 550. [Google Scholar]

- Mollick, E. Establishing Moore’s law. IEEE Ann. Hist. Comput. 2006, 28, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, P.; Thorpe, A.; Brunet, G. The quiet revolution of numerical weather prediction. Nature 2015, 525, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, G.; Milton, S.; Senior, C.; Brooks, M.; Ineson, S.; Reichler, T.; Kim, J. Analysis and reduction of systematic errors through a seamless approach to modeling weather and climate. J. Clim. 2010, 23, 5933–5957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Chen, Y.; Liu, D.; Li, C.; Li, H.; He, J. The optical flow method and its application to nowcasting. Acta Meteor. Sin. 2015, 73, 471–480. [Google Scholar]

- Beauchemin, S.S.; Barron, J.L. The computation of optical flow. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 1995, 27, 433–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowler, N.E.; Pierce, C.E.; Seed, A. Development of a precipitation nowcasting algorithm based upon optical flow techniques. J. Hydrol. 2004, 288, 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Li, X.; Ye, Y.; Xie, P.; Li, Y. A generative adversarial gated recurrent unit model for precipitation nowcasting. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2019, 17, 601–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, Q.K.; Song, S.k. Multi-channel weather radar echo extrapolation with convolutional recurrent neural networks. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirigati, F. Accurate short-term precipitation prediction. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2021, 1, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, C.; Liu, J.; Yue, Y.; Ren, K.; Deng, K.; Wang, X.; Sun, Y.; Qi, X. TPDTC-Net: A Decoupled Spatial–Temporal Network for Precipitation Nowcasting. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 4109818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.B.; Lee, I. Bridging the gap between training and inference for spatio-temporal forecasting. In ECAI 2020; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 1316–1323. [Google Scholar]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H.; Yeung, D.Y.; Wong, W.K.; Woo, W.C. Convolutional LSTM network: A machine learning approach for precipitation nowcasting. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1506.04214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S.; Barrington, L.; Bromberg, C.; Burge, J.; Gazen, C.; Hickey, J. Machine learning for precipitation nowcasting from radar images. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.12132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Yang, G.; Wang, Q.; Xu, C.; Liu, J.; Liu, W.; Shi, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Yu, X.; et al. Deep learning prediction of incoming rainfalls: An operational service for the city of Beijing China. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Data Mining Workshops (ICDMW); IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 180–185. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, A.G.; Navab, N.; Wachinger, C. Concurrent spatial and channel ‘squeeze & excitation’in fully convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 421–429. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, R.; Souto, Y.M.; Ogasawara, E.; Porto, F.; Bezerra, E. Stconvs2s: Spatiotemporal convolutional sequence to sequence network for weather forecasting. Neurocomputing 2021, 426, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oprea, S.; Martinez-Gonzalez, P.; Garcia-Garcia, A.; Castro-Vargas, J.A.; Orts-Escolano, S.; Garcia-Rodriguez, J.; Argyros, A. A review on deep learning techniques for video prediction. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2020, 44, 2806–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Gao, Z.; Lausen, L.; Wang, H.; Yeung, D.Y.; Wong, W.K.; Woo, W.C. Deep learning for precipitation nowcasting: A benchmark and a new model. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.03458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Long, M.; Wang, J.; Gao, Z.; Yu, P.S. Predrnn: Recurrent neural networks for predictive learning using spatiotemporal lstms. arXiv 2017, arXiv:2103.09504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, H.; Long, M.; Wang, J.; Yu, P.S. Memory in memory: A predictive neural network for learning higher-order non-stationarity from spatiotemporal dynamics. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 9154–9162. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Yao, Z.; Wang, J.; Long, M. MotionRNN: A flexible model for video prediction with spacetime-varying motions. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 15435–15444. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.03762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, C.; Sun, F.; Zhang, J.; Song, Y.; Chen, S. Rainformer: Features extraction balanced network for radar-based precipitation nowcasting. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 19, 4023305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Lee, I.; Son, M.; Kang, Y.; Woo, S. Nowformer: A Locally Enhanced Temporal Learner for Precipitation Nowcasting. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS 2022 Workshop on Tackling Climate Change with Machine Learning, Online, 9 December 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Long, M.; Chen, K.; Xing, L.; Jin, R.; Jordan, M.I.; Wang, J. Skilful nowcasting of extreme precipitation with NowcastNet. Nature 2023, 619, 526–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Shi, X.; Wang, H.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Cui, C.; Li, D.; Wu, Y.; Chu, X.; Yeung, D.Y. Earthformer: Exploring space-time transformers for earth system forecasting. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 25390–25403. [Google Scholar]

- Ravuri, S.; Lenc, K.; Willson, M.; Kangin, D.; Lam, R.; Mirowski, P.; Fitzsimons, M.; Athanassiadou, M.; Kashem, S.; Madge, S.; et al. Skilful precipitation nowcasting using deep generative models of radar. Nature 2021, 597, 672–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Y.; Gong, B.; Langguth, M.; Mozaffari, A.; Zhi, X. CLGAN: A generative adversarial network (GAN)-based video prediction model for precipitation nowcasting. Geosci. Model Dev. 2023, 16, 2737–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Su, L.; Wong, W.K.; Lau, A.K.H.; Fung, J.C.H. Skillful Radar-Based Heavy Rainfall Nowcasting Using Task-Segmented Generative Adversarial Network. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 4103613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, T.; Seong-Sim, Y.; Shin, H.; Yoon, S. Evaluation of High-Intensity Precipitation Prediction Using Convolutional Long Short-Term Memory with U-Net Structure Based on Clustering. Water 2024, 16, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Huang, Q.; Chen, S. Deep learning model based on multi-scale feature fusion for precipitation nowcasting. Geosci. Model Dev. 2024, 17, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Song, X.; Guo, A.; Liu, K.; Cao, H.; Feng, T. Oceanic Precipitation Nowcasting Using a UNet-Based Residual and Attention Network and Real-Time Himawari-8 Images. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Ling, X.; Xue, Y.; Luo, W.; Zhu, L.; Qin, F.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, Y. Precipitation Nowcasting Using Diffusion Transformer With Causal Attention. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 4709916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, D.; Peng, X.; Wang, P. A Quantitative Precipitation Estimation Method Based on 3D Radar Reflectivity Inputs. Symmetry 2024, 16, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yin, M.; Wang, P.; Gao, Z. A Method Based on Deep Learning for Severe Convective Weather Forecast: CNN-BiLSTM-AM (Version 1.0). Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reulen, E.; Shi, J.; Mehrkanoon, S. GA-SmaAt-GNet: Generative adversarial small attention GNet for extreme precipitation nowcasting. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2024, 305, 112612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Chen, W.; Jung, H. Gated Attention Recurrent Neural Network: A Deeping Learning Approach for Radar-Based Precipitation Nowcasting. Water 2022, 14, 2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Sun, J.; Wei, H.; Shi, J.; Gao, M. Cloud Layer and Precipitation Forecasting via Multi-Scale Gated Temporal and Spatial Attention Network. Expert Syst. 2025, 42, e70099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Deng, K.; Zhang, D.; Liu, Y.; Leng, H.; Yin, F.; Ren, K.; Song, J. LPT-QPN: A Lightweight Physics-Informed Transformer for Quantitative Precipitation Nowcasting. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 4107119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhang, D.; Zheng, X.; Shan, H.; Zhang, J. Mutual Information Boosted Precipitation Nowcasting from Radar Images. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volatility-aware sample re-weighting framework for short-term photovoltaic power forecasting. Inf. Process. Manag. 2026, 63, 104612. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.