Modeling and Correction of Underwater Photon-Counting LiDAR Returns Based on a Modified Biexponential Distribution

Highlights

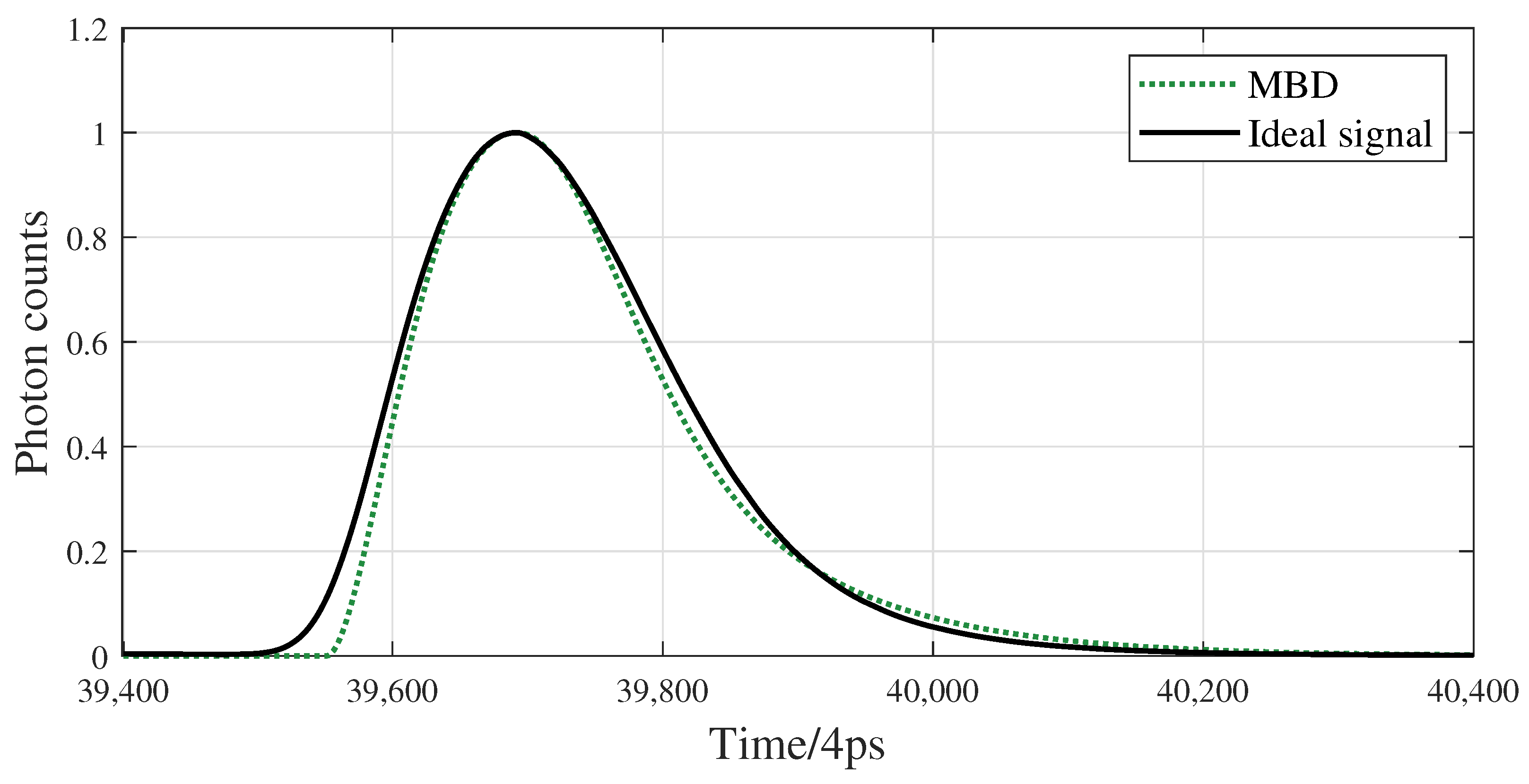

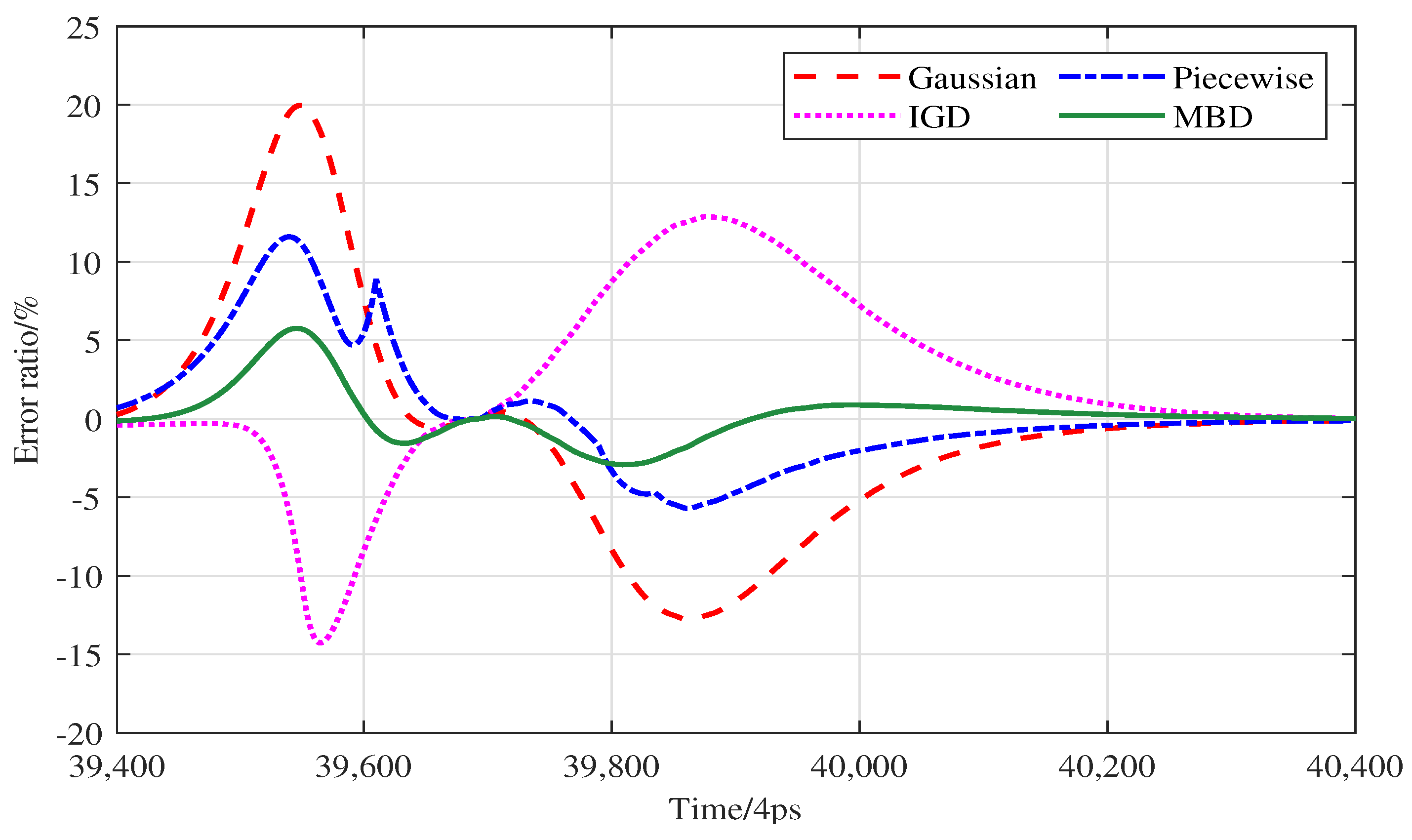

- A Modified Biexponential Distribution (MBD) model is proposed to accurately characterize the asymmetric shape of underwater single-photon LiDAR return pulses, effectively representing both sharp rising and long-tailed decay behaviors.

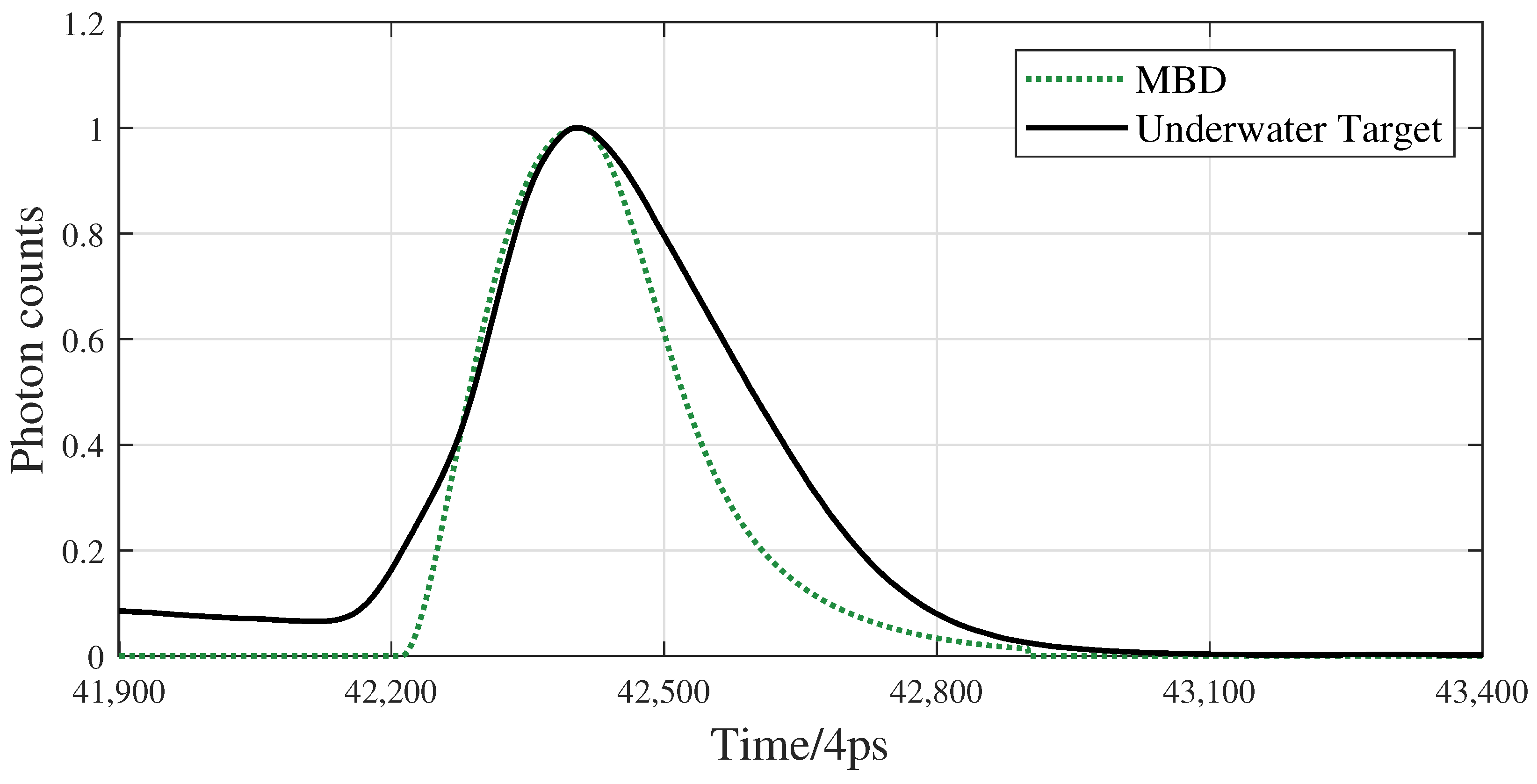

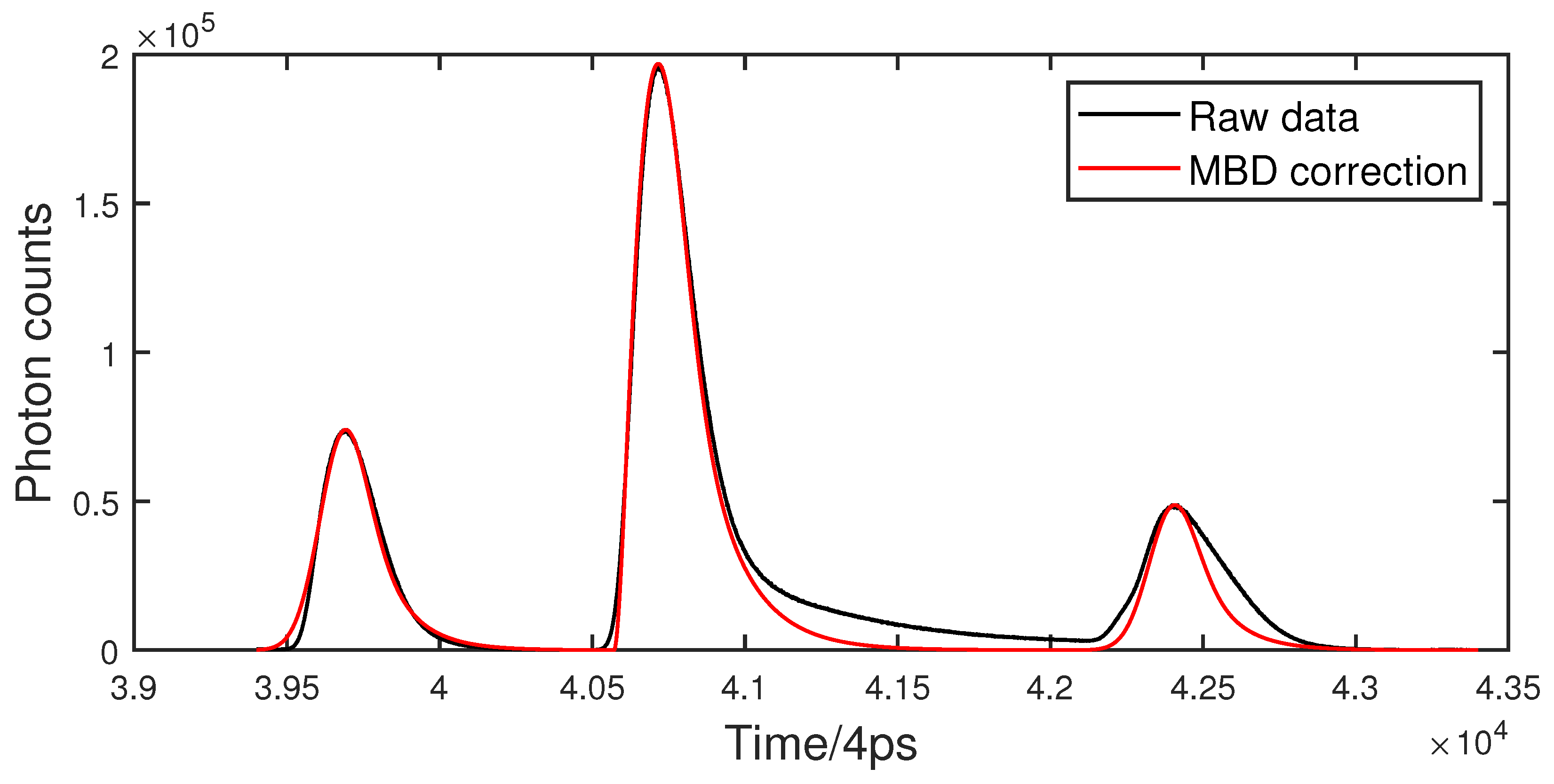

- The proposed model-driven IRF matching framework mitigates underwater pulse broadening effects and improves ranging accuracy without the need for labor-intensive underwater calibration.

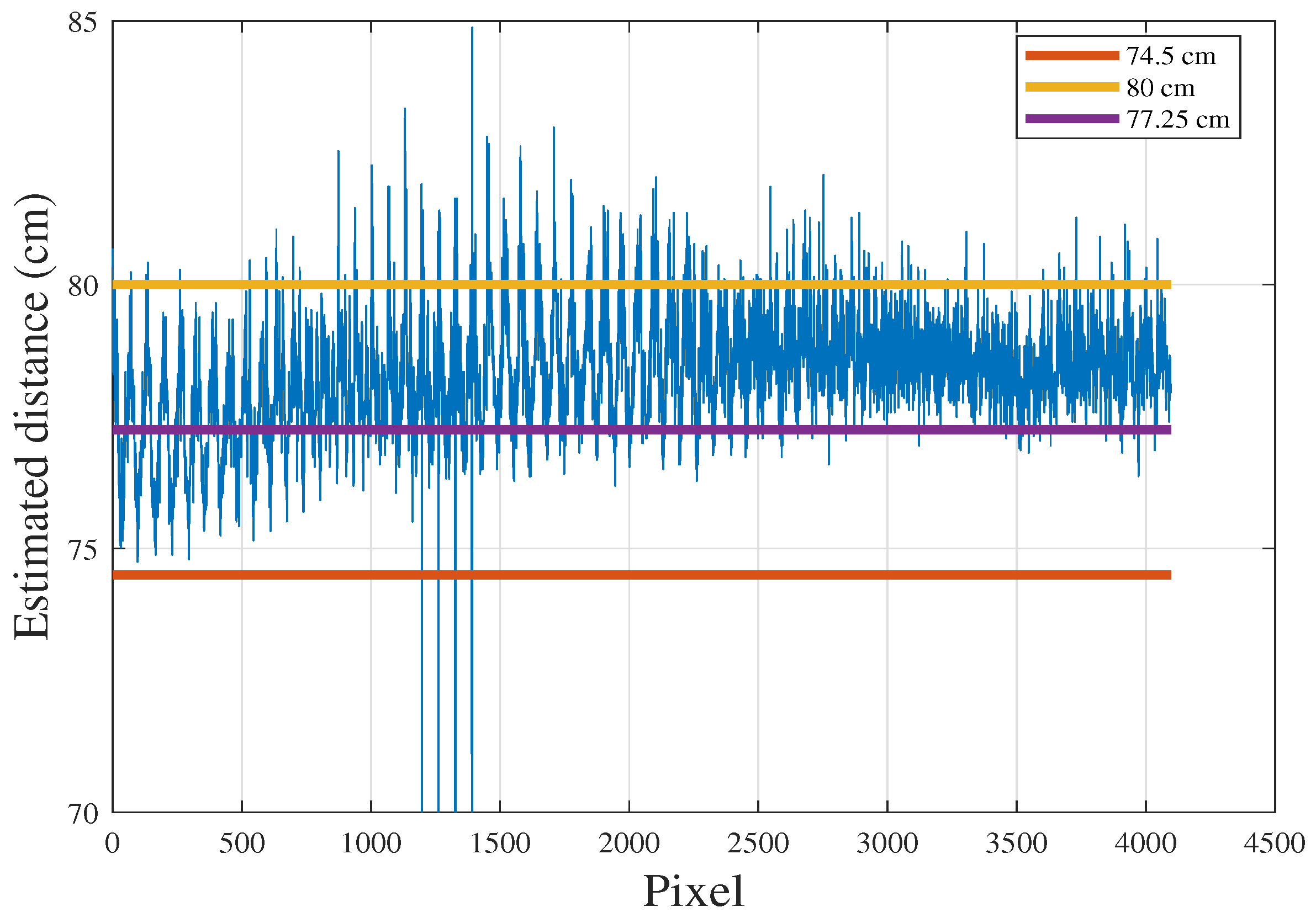

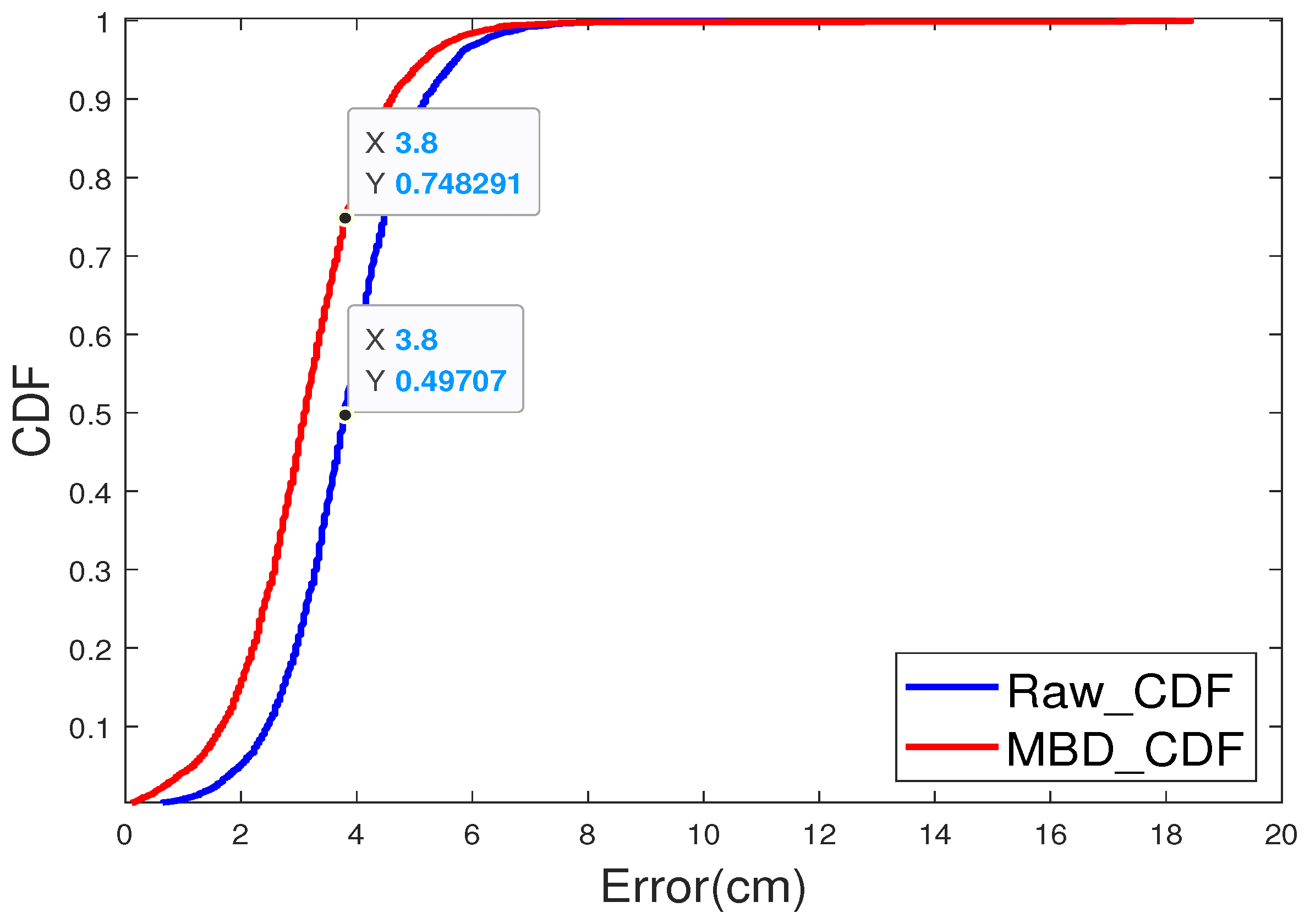

- The MBD model significantly enhances depth estimation accuracy in turbid underwater environments, achieving a 17.54 percentage reduction in Depth Absolute Error and a 50 percentage increase in the probability of precise ranging.

- This work establishes a robust analytical foundation for improving photon detection and bathymetric performance in underwater LiDAR systems, supporting future applications in marine mapping and underwater exploration.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Traditional LiDAR Return Model

2.1.1. Gaussian-Distributed Return Signal Model

2.1.2. Improved Gaussian-Distributed Return Signal Model

2.1.3. Piecewise Function Models

2.2. Modified Biexponential Distribution Model

2.3. Methods Implementation

3. Experimental System

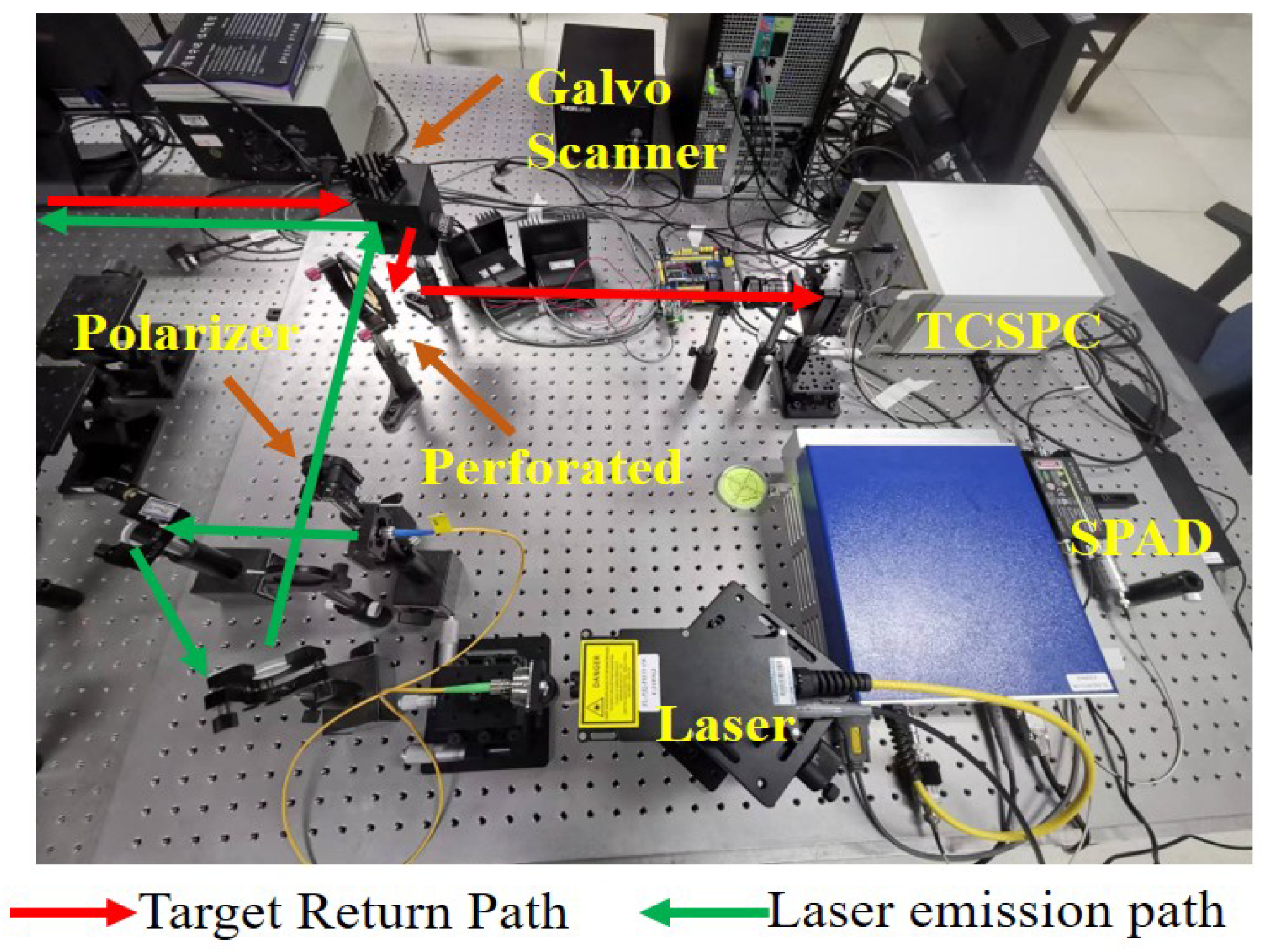

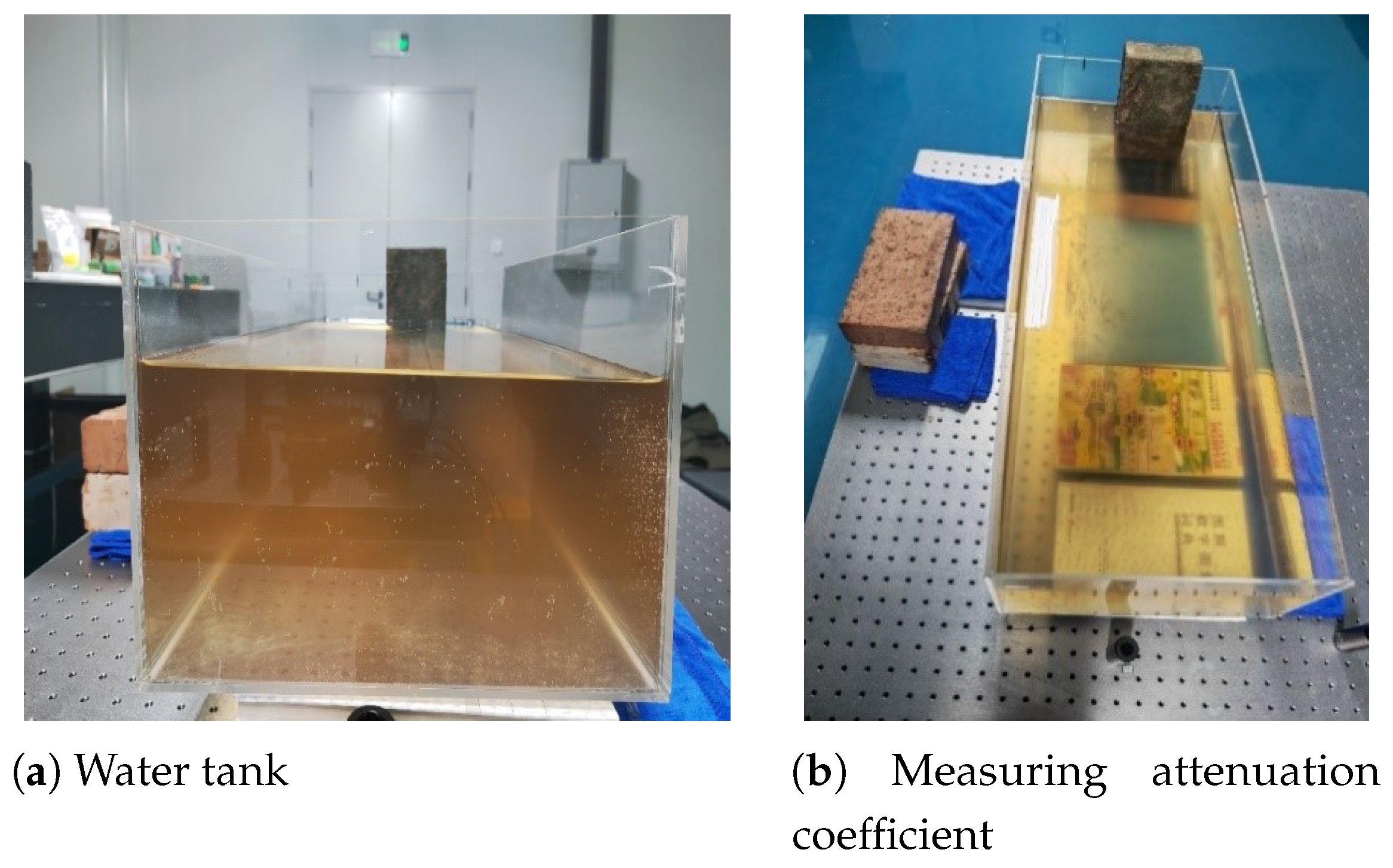

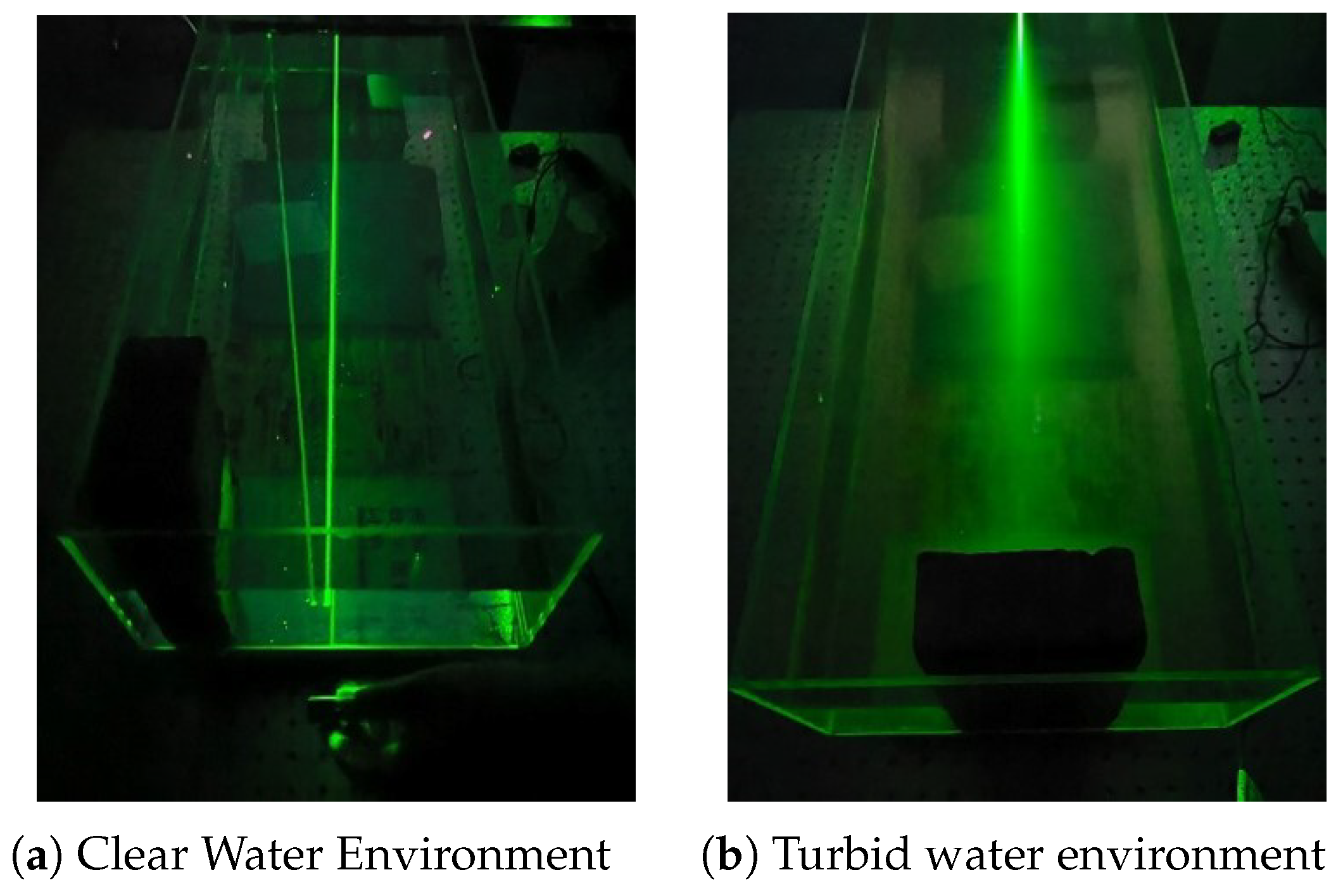

3.1. Experimental Setup and Environment

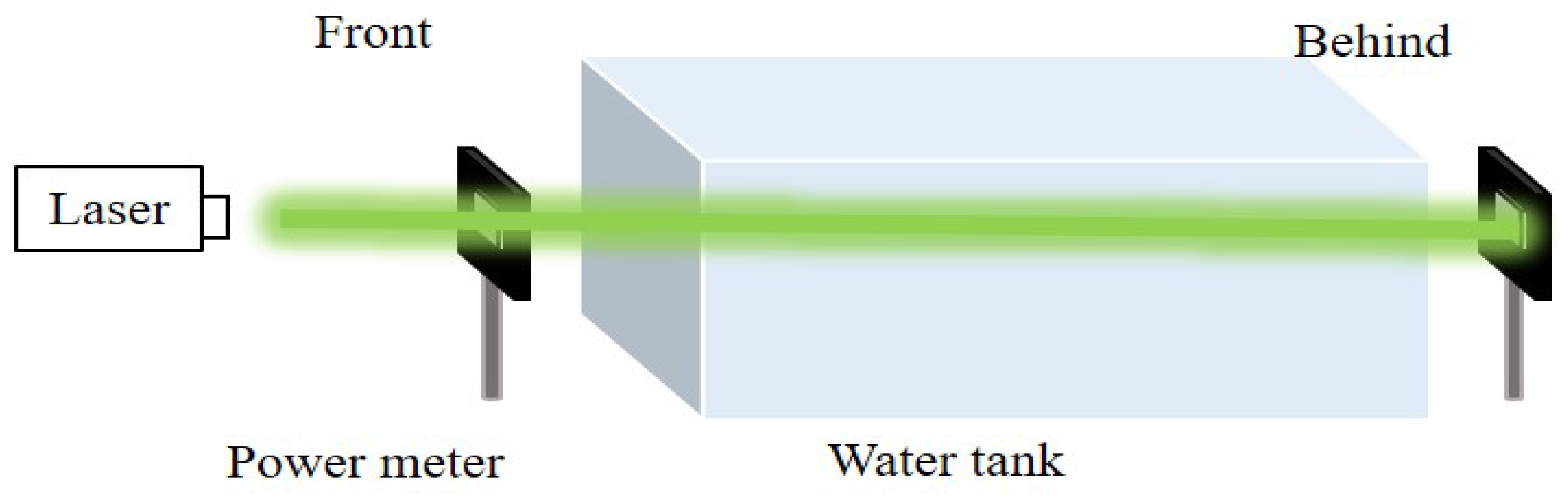

3.2. Attenuation Coefficient Calibration Experiment

4. Results and Discussion

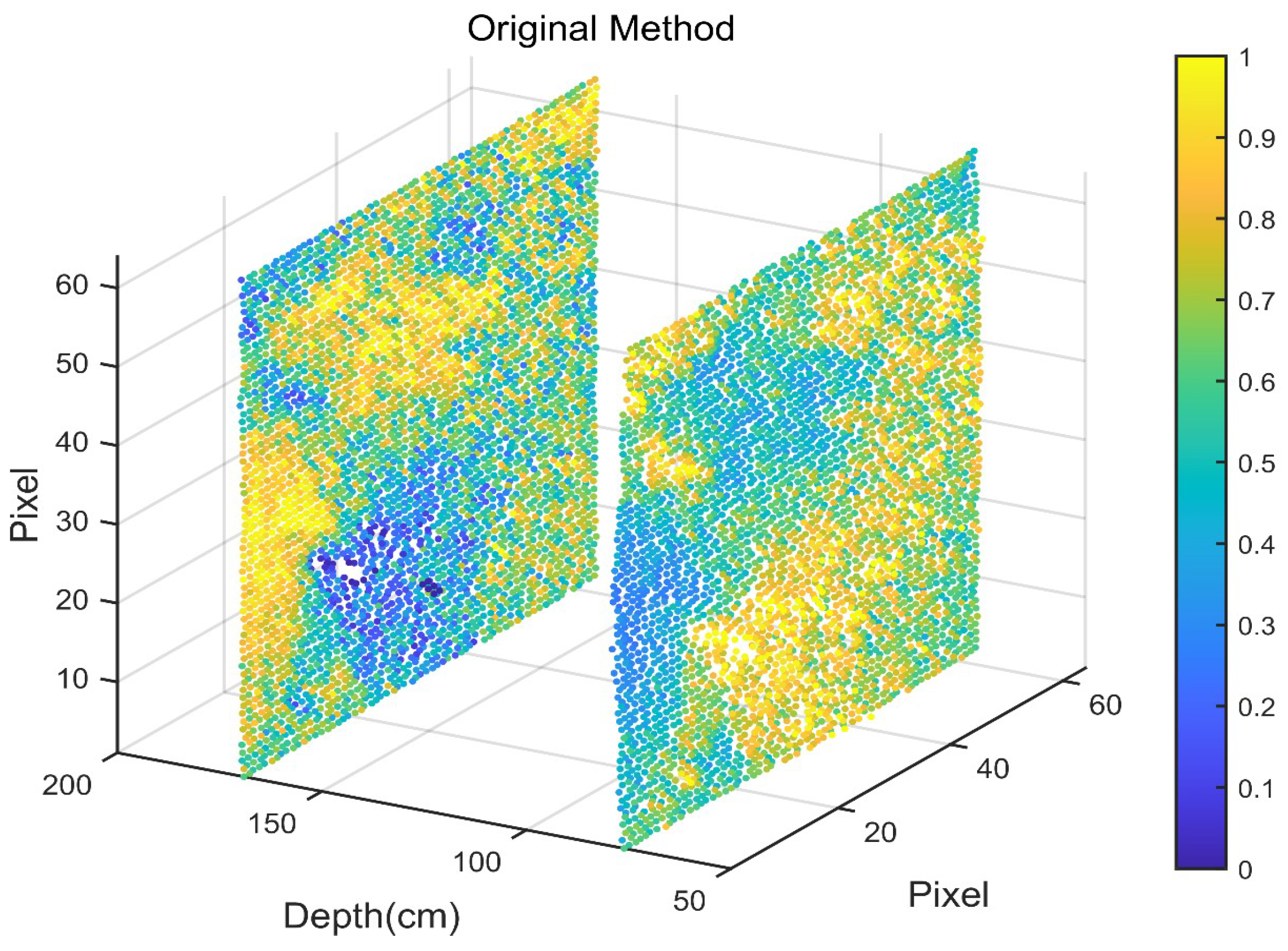

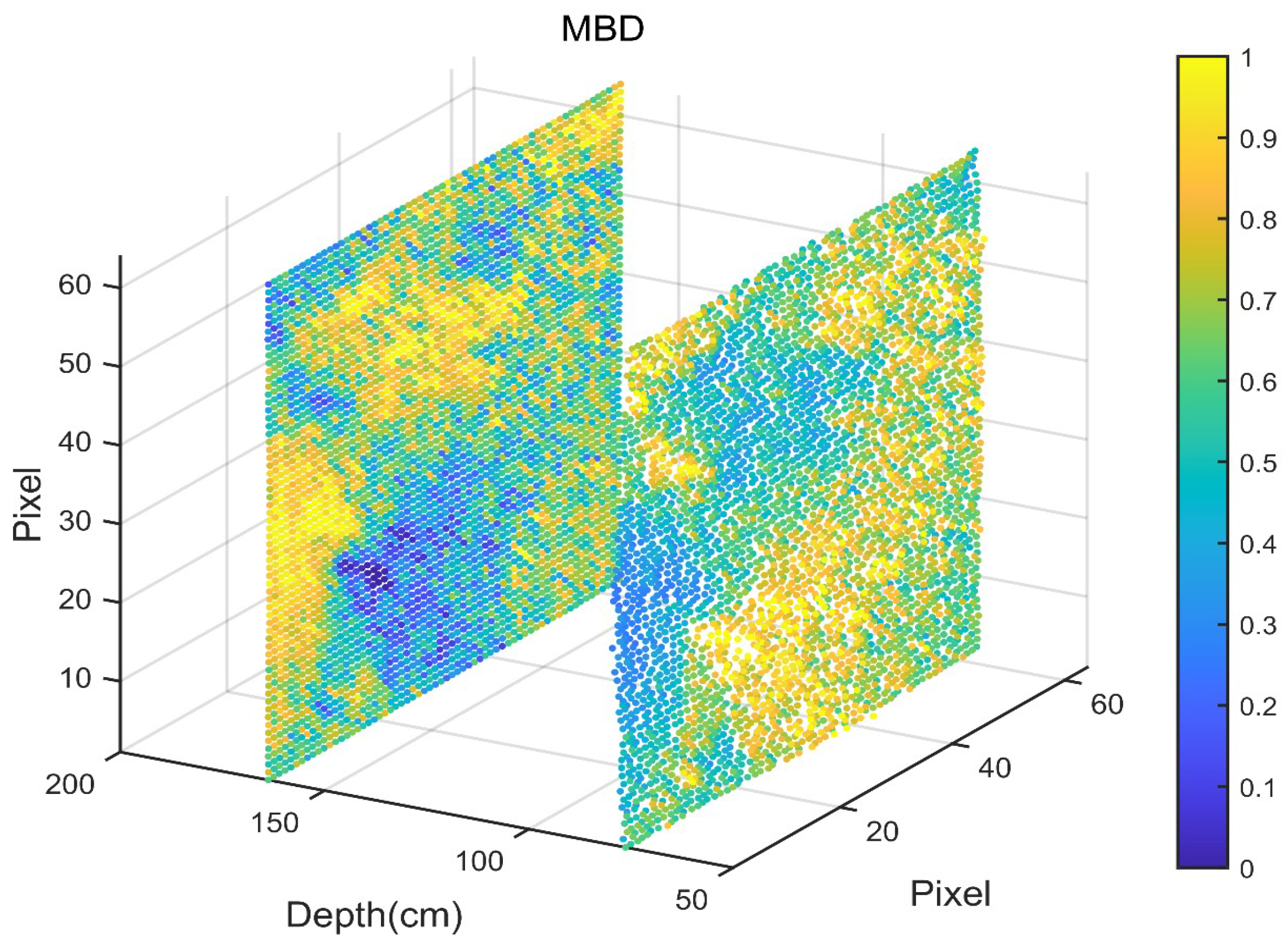

4.1. Experimental Analysis

4.2. Discussion and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shen, Y.; Zhao, C.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Huang, F. Underwater optical imaging: Key technologies and applications review. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 85500–85514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Cui, W.; Chen, C. Review of underwater sensing technologies and applications. Sensors 2021, 21, 7849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaffe, J.S. Underwater optical imaging: The past, the present, and the prospects. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2014, 40, 683–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.P.; Ye, J.T.; Huang, X.; Jiang, P.Y.; Cao, Y.; Hong, Y.; Yu, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Peng, C.Z.; et al. Single-photon imaging over 200 km. Optica 2021, 8, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.P.; Huang, X.; Cao, Y.; Wang, B.; Li, Y.H.; Jin, W.; Yu, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Peng, C.Z.; et al. Single-photon computational 3D imaging at 45 km. Photonics Res. 2020, 8, 1532–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Chen, C.; Zhang, E.; Li, H.; Yu, C.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Xue, B.; Zhuang, Q.; et al. 3D imaging of underwater scanning photon counting lidar based on multiscale spatio-temporal resolution. Opt. Express 2025, 33, 4463–4473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccarone, A.; Acconcia, G.; Steinlehner, U.; Labanca, I.; Rech, I.; Buller, G.S. Underwater time of flight depth imaging using an asynchronous linear single photon avalanche diode detector array. In Proceedings of the Emerging Imaging and Sensing Technologies for Security and Defence V; and Advanced Manufacturing Technologies for Micro-and Nanosystems in Security and Defence III; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2020; Volume 11540, pp. 102–108. [Google Scholar]

- Maccarone, A.; Drummond, K.; McCarthy, A.; Steinlehner, U.K.; Petillot, Y.R.; Henderson, R.K.; Altmann, Y.; Buller, G.S. Real-time underwater single-photon three-dimensional imaging. In Proceedings of the Emerging Imaging and Sensing Technologies for Security and Defence VII; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2022; Volume 12274, p. 1227403. [Google Scholar]

- Shangguan, M.; Li, Y.; Mo, Y.; Wang, J.; Huang, T. Compact underwater single-photon imaging lidar. Opt. Lett. 2025, 50, 1957–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhou, Z.; Luo, Q. Sequential Multimodal Underwater Single-Photon Lidar Adaptive Target Reconstruction Algorithm Based on Spatiotemporal Sequence Fusion. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Dios Carbajal, A.; Buller, G.S.; Maccarone, A. Single-photon depth imaging for underwater target discrimination. In Proceedings of the Advanced Photon Counting Techniques XIX; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2025; Volume 13448, p. 134480H. [Google Scholar]

- Adeoluwa, O.; Schnier, K.; Coldwell, C.; Swakshar, A.; Kung, P.; Gurbuz, S.; Kim, M. End-to-end underwater object recognition using multipolarization image fusion with single-photon LiDAR. In Proceedings of the Signal Processing, Sensor/Information Fusion, and Target Recognition XXXIV; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2025; Volume 13479, pp. 269–280. [Google Scholar]

- Maccarone, A.; Drummond, K.; McCarthy, A.; Steinlehner, U.K.; Tachella, J.; Garcia, D.A.; Pawlikowska, A.; Lamb, R.A.; Henderson, R.K.; McLaughlin, S.; et al. Submerged single-photon LiDAR imaging sensor used for real-time 3D scene reconstruction in scattering underwater environments. Opt. Express 2023, 31, 16690–16708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccarone, A.; Della Rocca, F.M.; McCarthy, A.; Henderson, R.; Buller, G.S. Three-dimensional imaging of stationary and moving targets in turbid underwater environments using a single-photon detector array. Opt. Express 2019, 27, 28437–28456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hao, W.; Chen, S.; Xie, M.; Li, X.; Shi, H.; Feng, X.; Su, X. Underwater single photon profiling under turbulence and high attenuation environment. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hao, W.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, W.; Xie, M.; Zhu, W.; Su, X. Underwater single photon 3D imaging with millimeter depth accuracy and reduced blind range. Opt. Express 2023, 31, 30588–30603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, M.A. Fundamentals of Radar Signal Processing; McGraw-Hill Education: Columbus, OH, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lindell, D.B.; O’Toole, M.; Wetzstein, G. Single-photon 3D imaging with deep sensor fusion. ACM Trans. Graph. 2018, 37, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, S.; Wang, J.; Ma, C.; Su, X. Precision Improvement of Underwater Single Photon Imaging Based on Model Matching. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 2023, 35, 253–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, K.; Liu, B.; Fang, L.; Wang, H.; Chen, Z.; Luo, J. Correction of range walk error for underwater photon-counting imaging. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 36260–36273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinvall, O.K.; Carlsson, T. Three-dimensional laser radar modeling. In Proceedings of the Laser Radar Technology and Applications VI; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2001; Volume 4377, pp. 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Marin, S.; Wallace, A.M.; Gibson, G.J. Bayesian analysis of lidar signals with multiple returns. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2007, 29, 2170–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellegrini, S.; Buller, G.S.; Smith, J.M.; Wallace, A.M.; Cova, S. Laser-based distance measurement using picosecond resolutiontime-correlated single-photon counting. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2000, 11, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greeley, A.P.; Neumann, T.A.; Kurtz, N.T.; Markus, T.; Martino, A.J. Characterizing the system impulse response function from photon-counting LiDAR data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2019, 57, 6542–6551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapp, J.; Dawson, R.M.; Goyal, V.K. Dithered depth imaging. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 35143–35157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Ying, Y.L.; Yan, B.Y.; Wang, H.F.; He, P.G.; Long, Y.T. Exponentially modified Gaussian relevance to the distributions of translocation events in nanopore-based single molecule detection. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2014, 25, 1029–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.C.; Su, X.Q.; Zhu, W.H.; Chen, S.M.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Xu, W.H.; Wang, D.J. A time-correlated single photon counting signal denoising method based on elastic variational mode extraction. ACTA Phys. Sin. 2021, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Liu, S.; Li, Z.P.; Huang, X.; Jiang, P.; Xu, Y.; Wu, C.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, Y.C.; Ren, H.L.; et al. Airborne single-photon LiDAR towards a small-sized and low-power payload. Optica 2024, 11, 612–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicco, D.; Warrens, M.J.; Jurman, G. The coefficient of determination R-squared is more informative than SMAPE, MAE, MAPE, MSE and RMSE in regression analysis evaluation. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2021, 7, e623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, T.P.; Chen, W.J. Using Pearson correlation coefficient as a performance indicator in the compensation algorithm of asynchronous temperature-humidity sensor pair. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 53, 103924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, B.; Wang, X. A new filter feature selection algorithm for classification task by ensembling pearson correlation coefficient and mutual information. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 131, 107865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Hutson, A.D. Inferential procedures based on the weighted Pearson correlation coefficient test statistic. J. Appl. Stat. 2024, 51, 481–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, R.; Altmann, Y.; Ren, X.; McCarthy, A.; Lamb, R.A.; McLaughlin, S.; Buller, G.S. Comparative study of sampling strategies for sparse photon multispectral lidar imaging: Towards mosaic filter arrays. J. Opt. 2017, 19, 094006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Altmann, Y.; Tobin, R.; Mccarthy, A.; Mclaughlin, S.; Buller, G.S. Wavelength-time coding for multispectral 3D imaging using single-photon LiDAR. Opt. Express 2018, 26, 30146–30161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Wavelength | 532 nm |

| Laser pulse width | 501 ps@532 nm |

| Average output power of the laser | 2.85 mW |

| Pulse repetition frequency | 1 MHz |

| Single-point cumulative time | 120 s |

| Photon detection efficiency | 50% |

| Dead time | 22 ns |

| Bin width | 4 ps |

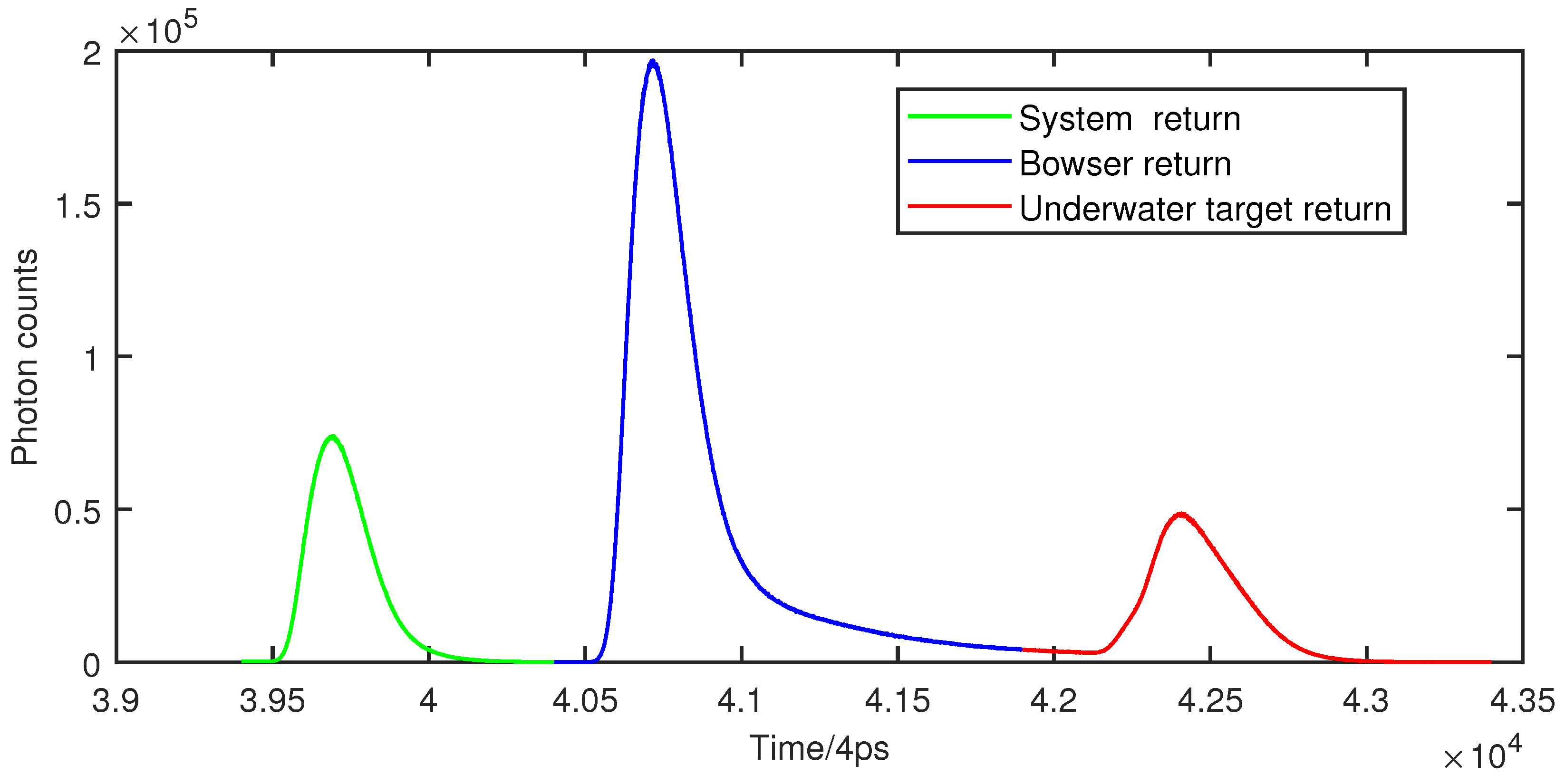

| System Return | Bowser Return | Underwater Target Return | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peak position | 293 | 1317 | 3007 |

| FWHM | 218 | 225 | 302 |

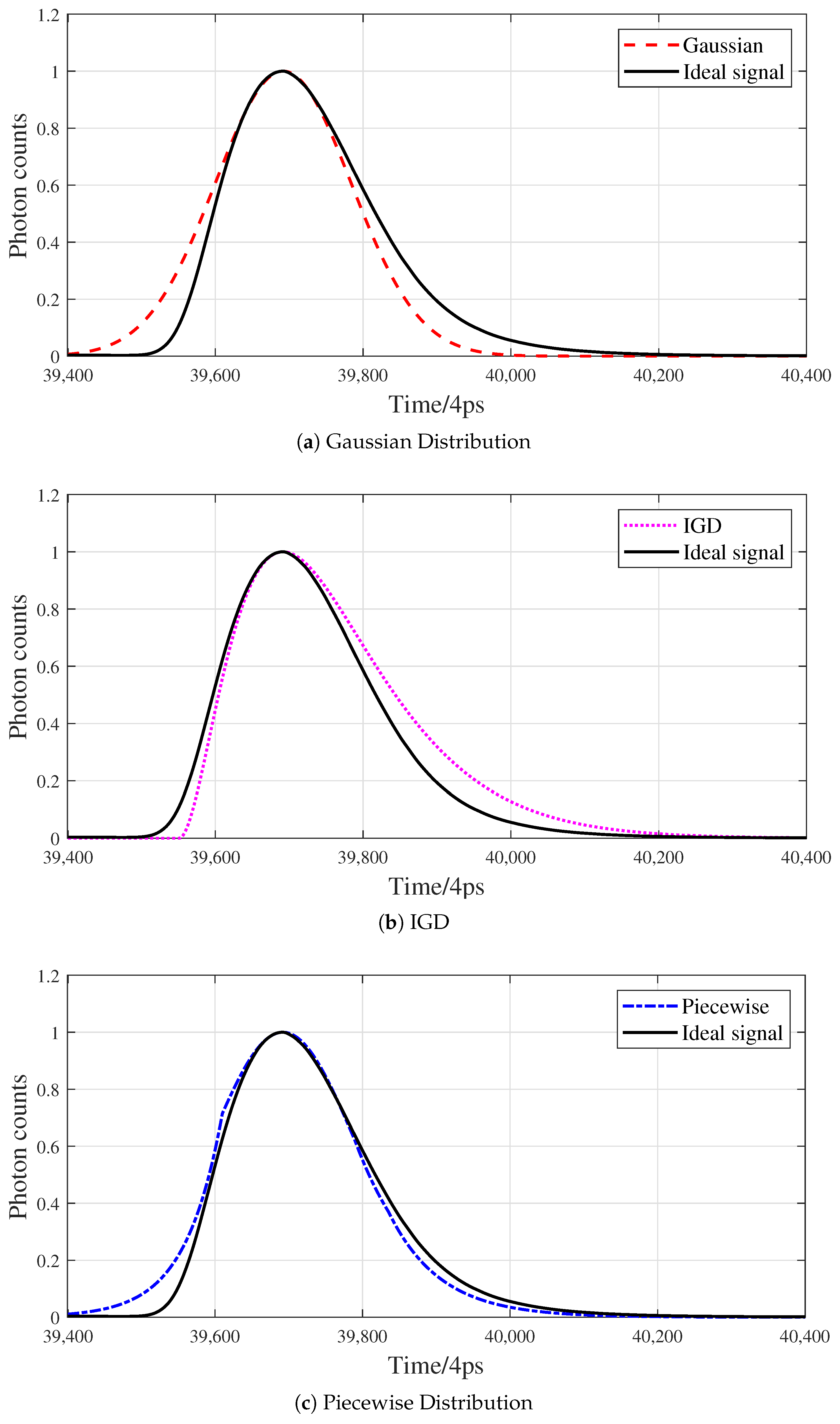

| Model | RMSPE/% | MAPE/% | R-Squared | Pearson Correlation Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian | 7.26 | 4.83 | 0.9530 | 0.9762 |

| IGD | 6.26 | 4.34 | 0.9698 | 0.9848 |

| Piecewise | 3.86 | 2.58 | 0.9867 | 0.9933 |

| MBD | 1.62 | 1.04 | 0.9919 | 0.9955 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Average power | 2.85 mW |

| Pulse repetition frequency | 1 MHz |

| Single-point cumulative time | 0.5 s |

| Image size |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Hao, W.; Chen, S.; Xie, M.; Shi, H.; Li, X.; Lian, X.; Su, X.; Xing, R.; Ding, L. Modeling and Correction of Underwater Photon-Counting LiDAR Returns Based on a Modified Biexponential Distribution. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 489. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18030489

Wang J, Hao W, Chen S, Xie M, Shi H, Li X, Lian X, Su X, Xing R, Ding L. Modeling and Correction of Underwater Photon-Counting LiDAR Returns Based on a Modified Biexponential Distribution. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(3):489. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18030489

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jie, Wei Hao, Songmao Chen, Meilin Xie, Heng Shi, Xiangyu Li, Xuezheng Lian, Xiuqin Su, Runqiang Xing, and Lu Ding. 2026. "Modeling and Correction of Underwater Photon-Counting LiDAR Returns Based on a Modified Biexponential Distribution" Remote Sensing 18, no. 3: 489. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18030489

APA StyleWang, J., Hao, W., Chen, S., Xie, M., Shi, H., Li, X., Lian, X., Su, X., Xing, R., & Ding, L. (2026). Modeling and Correction of Underwater Photon-Counting LiDAR Returns Based on a Modified Biexponential Distribution. Remote Sensing, 18(3), 489. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18030489