Highlights

What are the main findings?

- The core Adaptive Aware Dynamic Convolution Block (ADCB) enables the dynamic evolution of convolution kernels in accordance with rice scale and morphology, and for the first time realizes the adaptive dynamic evolution of convolution kernel morphology as rice scale varies.

- ADC-YOLO maintains stable full-lifecycle detection, solving the issue of missed detection of small seedling targets and inaccurate detection of overlapping leaves in the mature stage. On the RiceS dataset, ADC-YOLO outperforms state-of-the-art (SOTA) algorithms.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- This paper provides robust technical support for intelligent rice field monitoring: it is applicable to UAV-based seedling distribution tracking (aiding precise transplanting), reduces manual inspection costs, and improves the efficiency of precision agriculture.

- This paper advances the application of computer vision in precision agriculture: it breaks the limitations of traditional fixed-kernel convolution and provides a reusable algorithm paradigm for the full-lifecycle detection of other crops.

Abstract

High-precision detection of rice targets in precision agriculture is crucial for yield assessment and field management. However, existing models still face challenges, such as high rates of missed detections and insufficient localization accuracy, particularly when dealing with small targets and dynamic changes in scale and morphology. This paper proposes an accurate rice detection model for UAV images based on Adaptive Aware Dynamic Convolution, named Adaptive Dynamic Convolution YOLO (ADC-YOLO), and designs the Adaptive Aware Dynamic Convolution Block (ADCB). The ADCB employs a “Morphological Parameterization Subnetwork” to learn pixel-specific kernel shapes and a “Spatial Modulation Subnetwork” to precisely adjust sampling offsets and weights—realizing for the first time the adaptive dynamic evolution of convolution kernel morphology with variations in rice scale. Furthermore, ADCB is embedded into the interaction nodes of the YOLO backbone and neck; combined with depthwise separable convolution in the neck, it synergistically enhances multi-scale feature extraction from rice images. Experiments on public datasets show that ADC-YOLO comprehensively outperforms state-of-the-art algorithms in terms of AP50 and AP75 metrics and maintains stable high performance in scenarios such as small targets at the seedling stage and leaf overlap. This work provides robust technical support for intelligent rice field monitoring and advances the practical application of computer vision in precision agriculture.

1. Introduction

As a staple food crop for more than 50% of the global population, the stable production of rice is directly linked to the stability of the global food security system [1]. Rice cultivation is widely distributed, covering areas from plains to hills, and the variations in planting environments across different regions pose multiple challenges to field management. Throughout the entire rice growth cycle, from controlling the timing of seedling transplantation to monitoring for lodging during maturity, precise management at every stage has a decisive impact on the final yield. However, traditional paddy field monitoring relies on manual inspection. For large-scale planting areas, this approach not only requires significant labor costs but also suffers from low data collection efficiency and high subjectivity, making it difficult to meet the demands of efficient and precise modern agricultural development [2,3,4]. Therefore, the development of automated target detection technology based on UAV imagery has become a core requirement for improving the efficiency of rice field management, and the rise of deep learning technology has provided a feasible technical pathway to address this need [5,6,7].

The rapid development of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) technology offers an efficient monitoring solution for precision agriculture. UAVs can flexibly capture high-resolution images of fields, supporting key tasks such as tracking crop growth, optimizing water and fertilizer application, and identifying field stress factors [6,8]. For instance, during the rice seedling stage, timely understanding of seedling distribution and growth status is crucial for the subsequent selection of transplantation timing; missing the optimal transplantation window may result in a yield reduction of over 10% [9]. In the middle and late stages of rice growth, monitoring issues such as lodging, diseases, and pests via UAV imagery enables the rapid formulation of intervention measures to mitigate losses [1,10,11]. However, during UAV-based paddy field imagery acquisition, the influence of flight parameters and field environments leads to numerous technical bottlenecks in subsequent rice target detection [12,13].

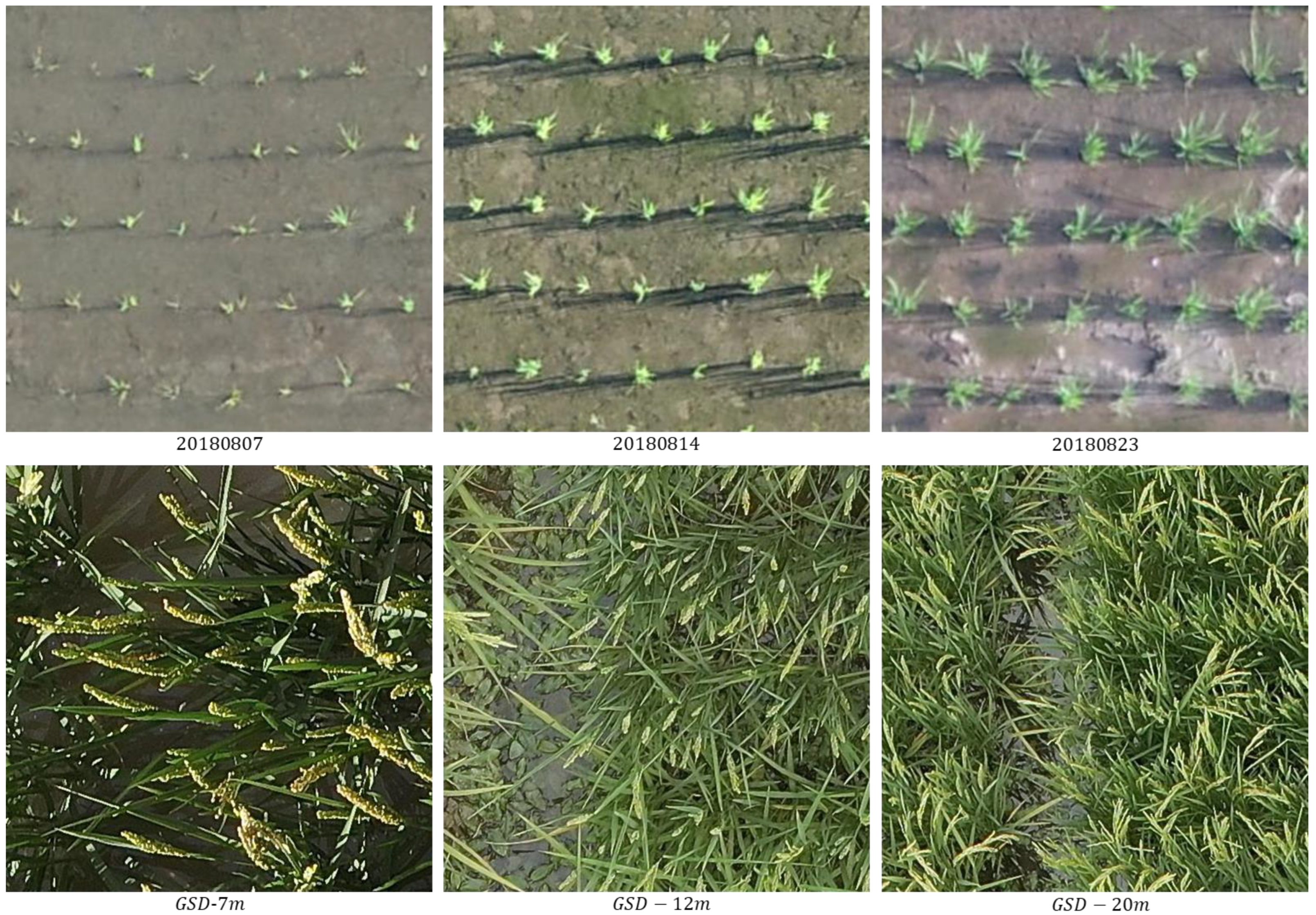

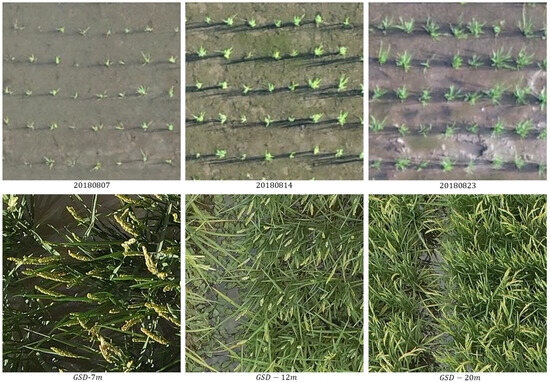

Rice target detection based on UAV imagery primarily faces three core challenges. The first challenge stems from the image variations caused by changes in UAV flight altitude. Adjustments in UAV flight altitude alter the imaging scale of rice targets in the same area within the imagery. While low-altitude flights capture fine details, their coverage is limited. Conversely, high-altitude flights expand the coverage area but make it significantly more difficult to capture features of small targets. Such altitude fluctuations directly affect the stable recognition of targets by detection models. The second challenge is the complexity of scale variations. Rice targets in paddy fields range from a few centimeters at the seedling stage to dozens of centimeters at the maturity stage, resulting in significant scale differences throughout the growth cycle (as shown in Figure 1). Meanwhile, fluctuations in UAV flight attitude (e.g., changes in pitch angle) further exacerbate the instability of target scales, making it difficult for single-scale detection models to adapt to rice targets across the entire growth cycle. The third challenge is small-target detection. Critical monitoring targets such as rice seedlings occupy only a few pixels in UAV imagery, lacking sufficient feature information and easily being confused with background elements like soil and weeds. Particularly under complex lighting conditions, the contrast between small targets and the background is further reduced, hindering improvements in detection accuracy [14].

Figure 1.

Comparison images of rice taken at different growth stages and from varying altitudes.

Current mainstream deep learning-based object detection methods can be categorized into two types: two-stage and single-stage methods [15]. Among these, two-stage methods, represented by the R-CNN series, operate by first generating region proposals and then performing classification and localization. While they can achieve high detection accuracy, their complex computational process results in slow inference speed, making it difficult to meet the real-time requirements of UAV edge computing [16,17]. In contrast, single-stage methods (e.g., YOLO, SSD) adopt an end-to-end regression approach, which significantly improves detection speed but exhibits poor accuracy performance in scenarios involving small targets or large-scale variations [18,19]. Existing rice detection models often focus on a single growth stage or a specific environment. For example, some models are optimized solely for detecting lodging in mature rice but fail to consider the need for identifying small targets during the seedling stage. These models lack comprehensive optimization for altitude changes, scale differences, and small targets, leading to poor generalization in the complex conditions of real-world paddy fields [12]. Among the existing adaptive feature extraction methods, deformable convolution (DCN) [20] has a fixed convolution kernel. It can only optimize spatial sampling positions without changing the fixed sampling mechanism, thus struggling to address the key challenges in rice detection.

To address the core contradiction between “morphological heterogeneity across the growth cycle” and “rigid scale adaptation of traditional convolutions” in UAV-based rice remote sensing detection, this study proposes the Adaptive Aware Dynamic Convolution Block (ADCB). This block adopts a collaborative dual-branch subnetwork architecture, including a morphological parameterization subnetwork and a spatial modulation subnetwork. It accurately predicts the offset and sampling weight of the convolution kernel corresponding to each pixel, realizing the deep coupling of “morphology-guided spatial modulation” during feature extraction. Each pixel in the input feature map learns exclusive convolution kernel parameters, enabling the shape and sampling method of the convolution kernel to evolve dynamically with the scale and morphology of rice targets, thereby achieving precise extraction of rice features across multiple growth cycles [21,22].

Meanwhile, depthwise separable convolution is integrated into the neck network. Lightweight modules such as DS_C3K2 are used to reduce computational load, which collaborates with ADCB to enhance the adaptive multi-scale feature extraction capability. After the features output by the backbone network are dynamically reshaped by ADCB, the neck network completes cross-scale fusion. The fused features are finally fed into the detection heads (One-to-Many/One-to-One Head) to achieve accurate classification and regression. This design not only ensures real-time performance but also naturally adapts to the morphological heterogeneity of rice throughout its growth cycle, significantly improving the accuracy and inference efficiency of rice detection across the entire growth cycle in UAV scenarios.

Our concrete contributions are threefold:

- We introduce the Adaptive Aware Dynamic Convolution Block (ADCB). A morphology-parameterization subnet and a spatial-modulation subnet jointly learn pixel-specific kernel shapes and sampling offsets/weights, enabling full-lifecycle multi-scale representation and transcending the rigidity of traditional convolutions.

- Following the YOLO “backbone–neck–head” paradigm, we propose Adaptive Dynamic Convolution YOLO (ADC-YOLO). ADCB is embedded into every backbone–neck junction, while depthwise separable convolutions populate the neck. This pipeline—dynamic feature re-shaping in the backbone, cross-scale fusion in the neck, and precise classification/regression in the head—co-evolves with the morphological heterogeneity of rice across growth stages, lifting both accuracy and efficiency.

- In comparative experiments conducted on a public dataset, our proposed ADC-YOLO model was tested against other advanced methods. ADC-YOLO improved the mean average precision for full-lifecycle rice detection by 2.9%, effectively breaking through the bottleneck of adapting traditional YOLO frameworks to multi-scale targets in agricultural settings.

2. Related Work

2.1. Object Detection

Mainstream deep learning-based object detection algorithms can be categorized into three types: single-stage detection methods, including Single-Shot Multi-box Detector (SSD) [23], You Only Look Once (YOLO) [24], RetinaNet [25], CenterNet [26], and EfficientDet [27]; two-stage detection methods, such as RCNN [28], Fast-RCNN [29], and Mask-RCNN [30]; and vision transformer-based methods such as the DETR series [31,32]. These algorithms differ in principles and architectures, as well as in speed and accuracy. Two-stage detection methods tend to achieve higher accuracy but suffer from slower speed; DETR models have a large computational load and large model size, making them unsuitable for real-time detection on edge devices. In contrast, single-stage detection methods strike a balance between speed and accuracy while maintaining relatively high speed. For agricultural tasks, single-stage detection methods feature well-balanced, real-time detection speed, accuracy, and resource consumption, which makes them suitable for various applications in agriculture [16].

The YOLO framework, first introduced by Redmon et al. [24], is a highly influential achievement. It performs image feature extraction, object localization, and classification in a single forward pass. The method first divides the image into grids and then, based on these grids, simultaneously predicts bounding boxes and class probabilities. Finally, it uses non-maximum suppression (NMS) to refine the detection results. This approach eliminates the redundant processes of traditional two-stage detection algorithms and has led to the development of multiple major versions [33,34,35,36,37,38]. Meanwhile, several improvements and optimization efforts have been made based on these major versions. For instance, an improved algorithm was proposed in YOLOv4-dense [39] (based on YOLOv4) for cherry fruit detection. Additionally, YOLO-FCE [40], built on the YOLOv9 architecture, performs analysis of clustering distances to enhance the model’s feature extraction capability and improve the detection accuracy of animal species. Furthermore, AED-YOLO11 [41], which is based on the YOLO11 architecture, introduces an adaptive frequency-domain aggregation module, providing dedicated enhancement for small object recognition. MFR-YOLOv10 [42], derived from YOLOv10s, combines multi-branch enhanced coordinate attention with a multi-layer feature reconstruction (MFR) mechanism. This integration strengthens the feature extraction capability for remote sensing images and improves the model’s perceptual capability for objects of varying sizes in such images.

2.2. Agricultural Intelligent Detection

Deep learning-based computer vision applications have developed and been applied rapidly in the agricultural field. As low-cost and efficient technical tools in precision agriculture, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) can capture remote sensing images with high spatial and temporal resolution. By extracting key agricultural information through object detection technology in image processing, UAVs effectively optimize field management practices, help reduce production costs and environmental impacts, and enhance the implementation effect of precision agriculture [43,44]. A previous study [45] evaluated 13 deep learning-based object detectors for weed detection. Among them, YOLOv5n achieved the fastest inference speed while maintaining comparable detection accuracy, demonstrating its potential for real-time deployment on resource-constrained devices. Another study [46] conducted a performance analysis of various YOLO models and RT-DETR in crop detection, which showed that YOLO models achieve a balanced trade-off between accuracy and speed, making them suitable for a wide range of applications. In [47], the authors employed YOLOv7 for weed recognition and detection. R-UAV-Net [48], based on YOLOv4, incorporates components such as spatial and channel feature extraction blocks and uses UAV images to recognize, localize, and detect rice leaf diseases. MLAENet [49] was proposed using a multi-scale enhancement network that utilizes multi-column lightweight feature extraction modules. It leverages multiple dilated convolutions to generate density maps, which capture the contextual information of corn ears and enable more accurate counting of their numbers.

Another study [50] explored the detection performance of several one-stage and two-stage object detection models on defective rice seedlings and investigated the impact of transfer learning. SFC2Net [51] adopts multi-column pre-trained networks and multi-layer feature fusion methods to construct a scale-fused counting and classification network. Following the recent patch-based classification paradigm, it improves counting performance. In [52], the authors used UAV multispectral images to establish a linear yield estimation model and explored rice yield estimation approaches. RFF-PC [53] was proposed as a rice panicle counting algorithm with refined feature fusion. It calculates the receptive field size by extracting and fusing object size distributions and fuses features using a feature pyramid. Focusing on rice plant counting, RPNet [54] was designed with a deep learning network consisting of a feature encoder, a density map generator, and an attention map. It also includes an RP-loss function, which enhances counting performance. P2PNet-EFF [55], based on P2PNet, was proposed as a rice plant counting and localization algorithm. It introduces enhanced feature fusion and a multi-scale attention mechanism, which improves the capability of integrating detailed information and alleviates counting errors caused by rice leaf overlap. Li-YOLOv9 [12], built on YOLOv9, involves a rice seedling object detection model designed for detecting rice seedlings from large-scale UAV remote sensing data. RS-P2PNet [56] adopts a ResNet backbone network and incorporates a Mixed Local Channel Attention (MLCA) module and a multi-scale feature fusion module. This enables the model to integrate the shallow and deep semantic information of rice seedlings, thereby improving its localization accuracy. (P2PNet)-Paddy [57], based on P2PNet, combines a density-based sampler and k-nearest neighbor (k-NN) matching for targets. It mitigates the impact of density imbalance and improves the detection accuracy of rice panicles.

3. Methodology

3.1. Adaptive Dynamic Convolution YOLO (ADC-YOLO)

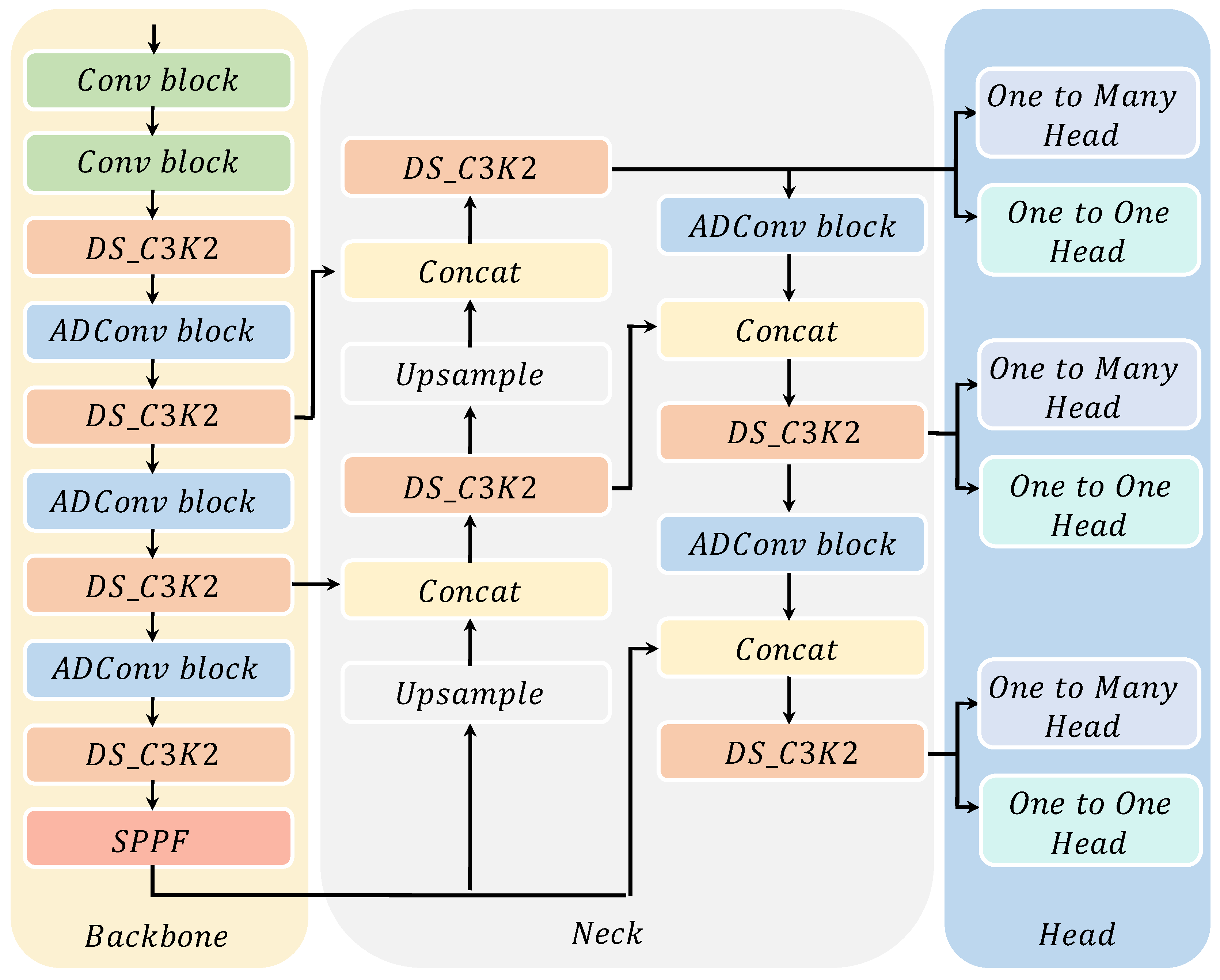

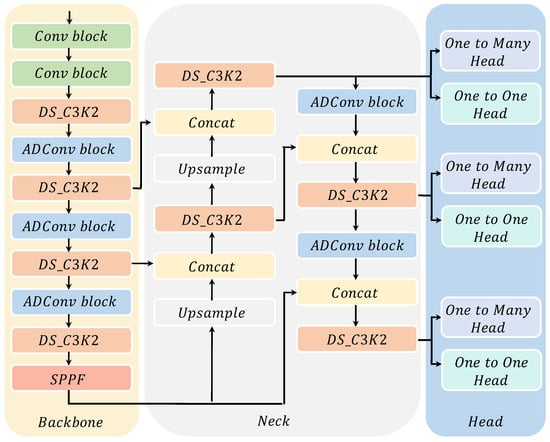

To address the challenges of multi-scale morphological heterogeneity in UAV-based rice detection across the entire growth cycle, this study proposes an accurate UAV image rice detection model based on Adaptive Aware Dynamic Convolution (ADC), which follows the end-to-end paradigm of “backbone feature extraction–dynamic morphological modulation–lightweight cross-scale fusion–detection head precise regression”. The network architecture comprises four core modules, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the ADC-YOLO network architecture.

The backbone network adopts an alternating structure of multi-stage convolution blocks (Conv blocks) and depthwise separable convolutions (DS_C3K2), integrated with Adaptive Aware Dynamic Convolution Blocks (ADCBs) deployed at the interaction nodes between the backbone and neck. Through the SPPF [58] module, it reduces computational load and enhances feature robustness, outputting base feature maps containing multi-scale morphological information of rice. Among them, Conv blocks include Conv + BN + SiLU.

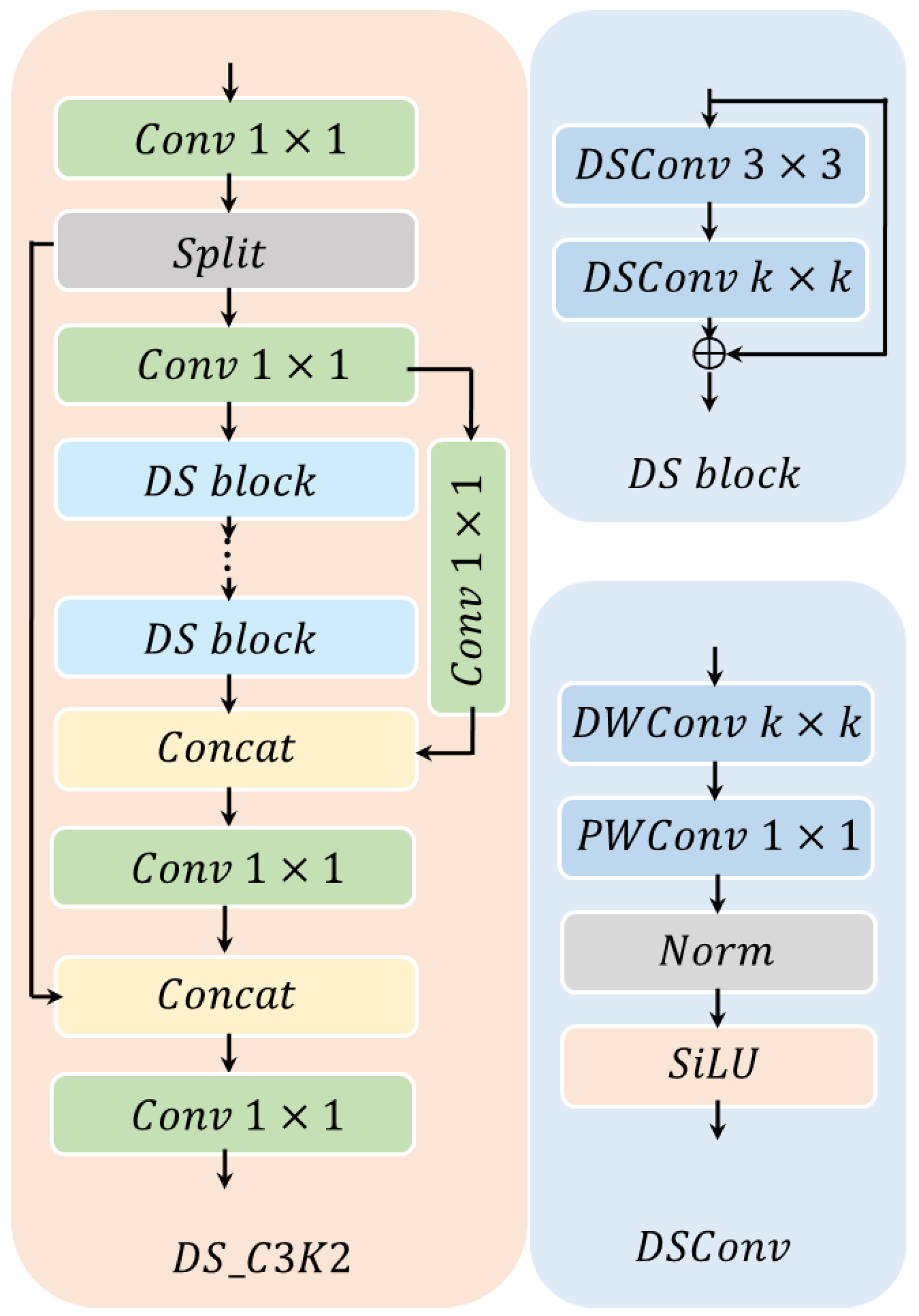

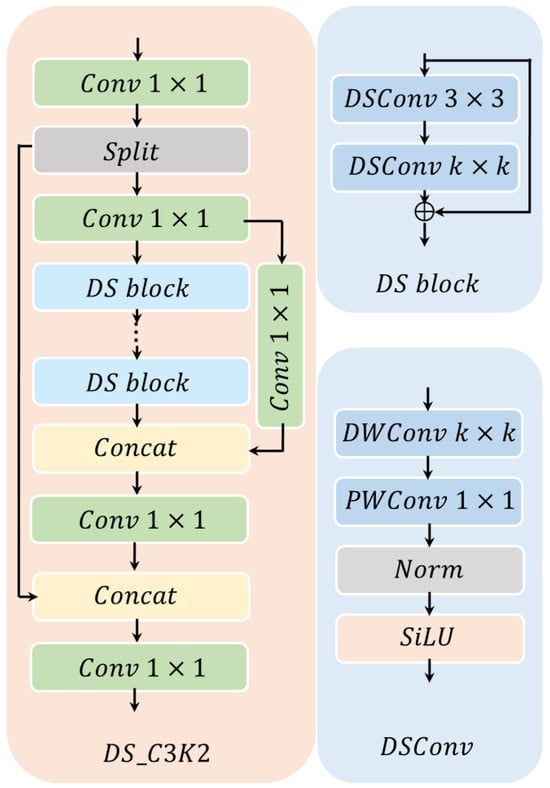

The lightweight neck network (Neck) integrates depthwise separable convolutions (DS_C3K2) with upsampling (Upsample) and feature concatenation (Concat) operations to perform cross-scale fusion on the features modulated by ADCB. As shown in Figure 3, DS_C3K2 utilizes a lightweight mechanism of “depthwise convolution (DWConv) for separating spatial features + pointwise convolution (PWConv) for aggregating channel information.” Its parameters (e.g., kernel size) can be set to different values (e.g., 5, 7) as needed. Using large-kernel depthwise separable convolutions, it reduces the computational load while maintaining the receptive field [59]. Collaborating with ADCB, it enhances multi-scale feature transmission and addresses the issue of feature loss in traditional Neck networks.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of the DS_C3K2 structure.

The detection head (Head), drawing on YOLOv10 [37], adopts a dual-branch design consisting of the “One-to-Many Head” and “One-to-One Head”. Specifically, One-to-Many Head is used during the training phase, while One-to-One Head is employed during the inference phase. This design performs accurate classification and regression on the cross-scale features output by the Neck, thereby improving inference efficiency.

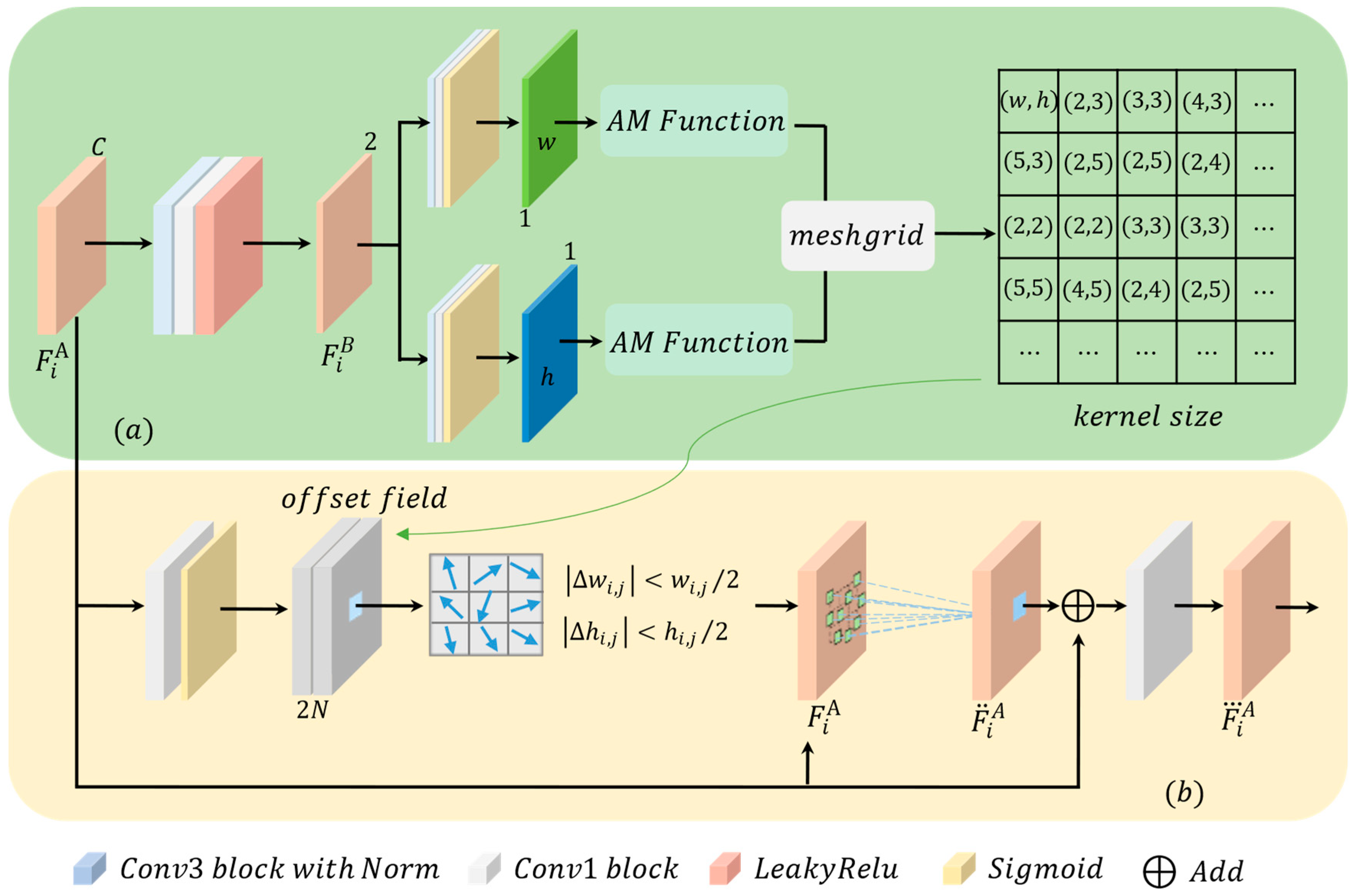

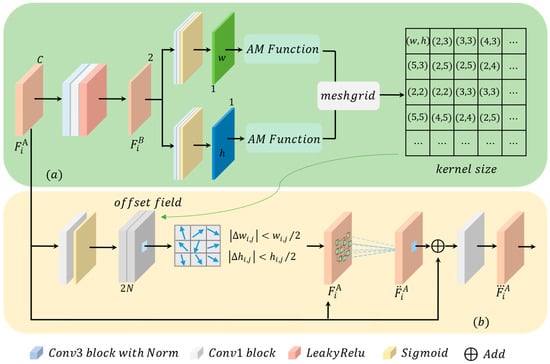

3.2. Adaptive Aware Dynamic Convolution Block (ADCB)

In the scenario of UAV-based rice remote sensing detection, rice exhibits significant morphological heterogeneity throughout its entire growth cycle—ranging from the tiny, slender features at the seedling stage to the broad, complex morphologies at the maturity stage. Traditional fixed-size (e.g., 3 × 3) square convolution kernels struggle to adapt to such dynamic changes, which limits the integrity and accuracy of feature extraction. To address this limitation, the Adaptive Aware Dynamic Convolution Block (ADCB) is designed. It learns exclusive convolution kernel parameters for each pixel in the input feature map, enabling the kernel’s shape and sampling method to evolve dynamically with the scale and morphology of rice targets. This allows for the accurate extraction of rice features across multiple growth cycles. The structure diagram of the ADC block is shown in Figure 4. It consists of a collaborative dual-branch subnetwork architecture, including a morphological parameterization subnetwork and a spatial modulation subnetwork. The overall workflow corresponds to parts (a) and (b) in the figure.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of the Adaptive Aware Dynamic Convolution Block (ADCB). (a) Morphological Parameterization Subnetwork, (b) Spatial Modulation Subnetwork.

The morphological parameterization subnetwork is designed to learn the shape of convolution kernels. For the input feature map , where and represent the height and width of the feature map, respectively, and denotes the number of channels, it first undergoes a series of convolution and activation operations (e.g., Conv3 block with Norm, LeakyReLU) to generate the intermediate feature . This process performs preliminary encoding on the original features, compresses channels, and extracts basic semantic information, whose mathematical expression can be described as follows:

where denotes the learnable parameters of the convolutional layer, and has 2 channels.

is split into two parallel branches along the channel dimension, which are used to predict the width w and height h of the convolution kernel, respectively. Taking the width branch as an example, a convolution block is used for feature extraction, and the Sigmoid activation function (a dynamic range-constrained activation function) is adopted. This avoids the problem of abnormal kernel sizes—excessively large sizes cause computational explosion, while excessively small sizes lead to the loss of morphological information. The branch outputs a width prediction feature map , where each pixel value represents the “relative probability” of the convolution kernel width at the corresponding position. Its mathematical form is expressed as follows:

Similarly, the height branch outputs the height prediction feature map .

where are the learnable parameters of the convolutional layers.

To map the “relative probabilities” to practical width and height values of the convolution kernel that can be used for sampling, an Adaptive Modulation (AM) function is introduced. Different scales correspond to different mapping intervals; the intervals adopted in this study are , , and , which overcomes the limitation of “global fixed intervals”. By performing thresholding, quantization, and other operations on and , the output is ensured to be of reasonable integer sizes. Finally, a global kernel size grid is generated through the meshgrid operation, yielding the convolution kernel size exclusive to each pixel. Through this, the dynamic adaptation of “one kernel shape per pixel” is achieved, i.e.,

This mechanism enables the convolution kernel shape to adjust flexibly with the morphology of rice targets (e.g., the narrow morphology at the seedling stage and the wide, flat morphology at the maturity stage).

The spatial modulation subnetwork takes the transformed features as input and generates an through operations such as convolution blocks, where is related to the number of sampling points. Each pixel in the offset field corresponds to two offset values in the horizontal and vertical directions, denoted as , which are constrained by . This constraint ensures that the sampling points after offset remain within a reasonable range of feature extraction, preventing confusion in feature extraction.

Based on the learned convolution kernel sizes and offset values, dynamic sampling is performed on the input feature map . Unlike traditional fixed-kernel sampling, the sampling point positions of ADCB are adaptively adjusted with the kernel shape and offset value of each pixel, enabling the accurate capture of the local morphological features of rice targets. The sampled features are fused via the Add operation:

This output provides more adaptable features for the subsequent cross-scale fusion of the Neck network and the classification and regression of the detection head.

3.3. Loss Function

To comprehensively and accurately guide the network training process, effectively adapt to the morphological heterogeneity of rice throughout its entire growth cycle in the UAV-based rice remote sensing detection task, and balance detection accuracy and efficiency simultaneously, a three-component loss function was designed:

where , , and are weight coefficients, which are used to balance the contribution of different loss components to the total loss.

For , focal loss is adopted instead of the traditional cross-entropy loss. This alleviates the accuracy degradation caused by the imbalance in the size and category of rice target samples, focuses on hard-to-classify samples, and suppresses the excessive influence of easy-to-classify samples. Its formula is defined as follows:

where is a balance coefficient, which serves to balance the overall weights of positive and negative samples and alleviate the issue where “background samples (negative samples) are far more numerous than target samples (positive samples)”. is a focusing coefficient; it reduces the loss contribution of easy-to-classify samples through an exponential term and focuses on hard-to-classify samples. denotes an indicator function for the presence of a target, taking a value of 1 for target regions and 0 for background regions. represents the predicted probability.

(regression loss) is used to optimize the position and size of predicted bounding boxes, making them as close as possible to the ground-truth bounding boxes. Considering the scale variations of rice targets at different growth stages, the CIoU (Complete Intersection over Union) loss function is adopted. This function calculates the overlapping area and center point distance between the predicted bounding box and the ground-truth bounding box, while also accounting for the consistency of aspect ratios. Its mathematical expression is given by

where denotes the center coordinates , width , and height of the ground-truth target box; represents the parameters of the target box predicted by the model; the calculation formula for CIoU is as follows:

where refers to the intersection over union. represents the squared distance between the center points of the ground-truth box and the predicted box. denotes the diagonal length of the smallest rectangle that simultaneously contains both the ground-truth box and the predicted box. is a balance coefficient, and is used to measure the consistency of the aspect ratios between the predicted box and the ground-truth box.

is the confidence loss, which is used to optimize the probability estimation of “whether the predicted bounding box contains a target”. The higher the IoU between the predicted box and the ground-truth box, the closer the confidence should theoretically be to 1; otherwise, it should be closer to 0. It can be expressed as

where denotes the ground-truth label; it takes a value of 1 when there is a target and 0 when there is no target.

4. Experiments

4.1. Dataset

Rice Seedling Dataset (RiceS) [60]: Established by agricultural research institutions, this dataset is designed for the training and validation of rice object detection models. The data were collected from three consecutive data collection missions at the same location, covering different growth stages of rice seedlings. It consists of 8 subsets, with a total of 600 images and 22,438 rice target samples. The data were split into training and test sets at an 8:2 ratio.

The DRPD dataset [61] comprises 5372 RGB images, which are cropped from aerial images captured by an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) at three different flight altitudes (GSD-7 m, GSD-12 m, and GSD-20 m). The dataset was annotated with a total of 259,498 rice panicle targets from the heading stage and other growth stages.

4.2. Experimental Details

All experiments in this study were conducted on a computer equipped with an NVIDIA RTX A6000 graphics card (48GB VRAM, 1 card), an Intel Xeon Gold 5320 CPU, and 128GB RAM. The operating system is 64-bit Ubuntu 20.04, with PyTorch 2.1 as the deep learning framework, Python 3.9, and CUDA 12.1. The Adam optimization algorithm was used for the model. A warmup strategy was adopted during training (15 epochs), with an initial learning rate of 0.02, and the total training process lasted for 100 epochs.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

Average precision (AP) measures the performance of an object detection model on a specific category. It is calculated as the area under the precision–recall (PR) curve, where the PR curve is composed of points with precision (P) on the vertical axis and recall (R) on the horizontal axis. Calculating AP requires setting a threshold for determining correct target predictions: a prediction is considered correct if the intersection over union (IoU) between the predicted bounding box and the ground-truth box is greater than or equal to a certain threshold. In this study, AP50 and AP75 are used as metrics for rice detection accuracy, which correspond to AP values when the IoU threshold is ≥0.5 and ≥0.75, respectively.

Precision describes the proportion of correctly predicted targets among all targets predicted by the model. Recall describes the proportion of correctly predicted targets among all actual targets in the dataset. The formulas for calculating precision (P) and recall (R) are as follows:

is the number of correctly detected targets, is the number of falsely detected targets, and is the number of missed targets. The value can be obtained by calculating the area under the PR curve, and its calculation formula is as follows:

Here, represents the function of the PR curve.

4.4. Comparative Experimental Results

The rice detection model ADC-YOLO proposed in this study was compared with multiple state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods on several public datasets. These comparative methods include EfficientDet, Fast R-CNN, Faster R-CNN, and a series of models under the YOLO framework [33,34,35,36,37,38] (such as YOLOv5s, YOLOv6s, YOLOv8s, YOLOv9s, YOLOv10s, YOLO11s, and Li-YOLOv9). Additionally, drawing on the approach in Reference [62], comparative experiments were conducted with the YOLO model integrated with DCN (YOLODCN). The quantitative comparison results are shown in Table 1. It can be seen that the proposed ADC-YOLO outperforms the advanced methods in both AP50 and AP75 metrics.

Table 1.

Comparison of detection metrics of different methods on the RiceS dataset.

From the quantitative comparison results, it can be observed that the YOLO series models exhibit better overall performance, with their AP50 values concentrated in the range of 97.90–98.60%—this demonstrates the effectiveness of feature pyramid optimization. However, constrained by the fixed attention mechanism, there remains a bottleneck in the localization accuracy for high-density rice targets. ADC-YOLO achieves comprehensive superiority in both metrics. Its performance advantage does not stem from biases in training parameters or datasets, but rather from the deep adaptation of its core improved modules to the rice target detection task. On the one hand, the ADCB module addresses the issue of insufficient feature capture for small rice targets and targets with imbalanced scales in deep learning networks, thereby enhancing detection accuracy. On the other hand, the high-precision AP75 indicates that ADC-YOLO has optimized the accuracy of bounding box regression, satisfying the requirement for “precision localization” in rice field management.

The detection metrics of ADC-YOLO on data from different rice growth cycles are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Detection metrics of ADC-YOLO on data from different rice growth cycles.

To verify the adaptability of ADC-YOLO for the full-lifecycle detection of rice, independent tests were conducted using three subsets of the Rice Seedling Dataset (RiceS) with different maturity levels, as well as data of varying maturity from the DRPD dataset, as shown as Table 3. Results show that ADC-YOLO exhibits excellent detection performance and strong stability throughout the entire lifecycle of rice: on RiceS, its AP50 values all exceed 99.5%, while it also achieves optimal performance on the DRPD dataset. This demonstrates that the model not only enables efficient capture of small-target features but also addresses leaf overlap and occlusion issues during the maturity stage, proving its ability to dynamically avoid environmental interference and target morphological differences. In conclusion, ADC-YOLO possesses strong generalization ability for adapting to the full-lifecycle detection of rice, providing stable support for field monitoring at all growth stages.

Table 3.

Comparison of detection metrics of different methods on the DRPD dataset.

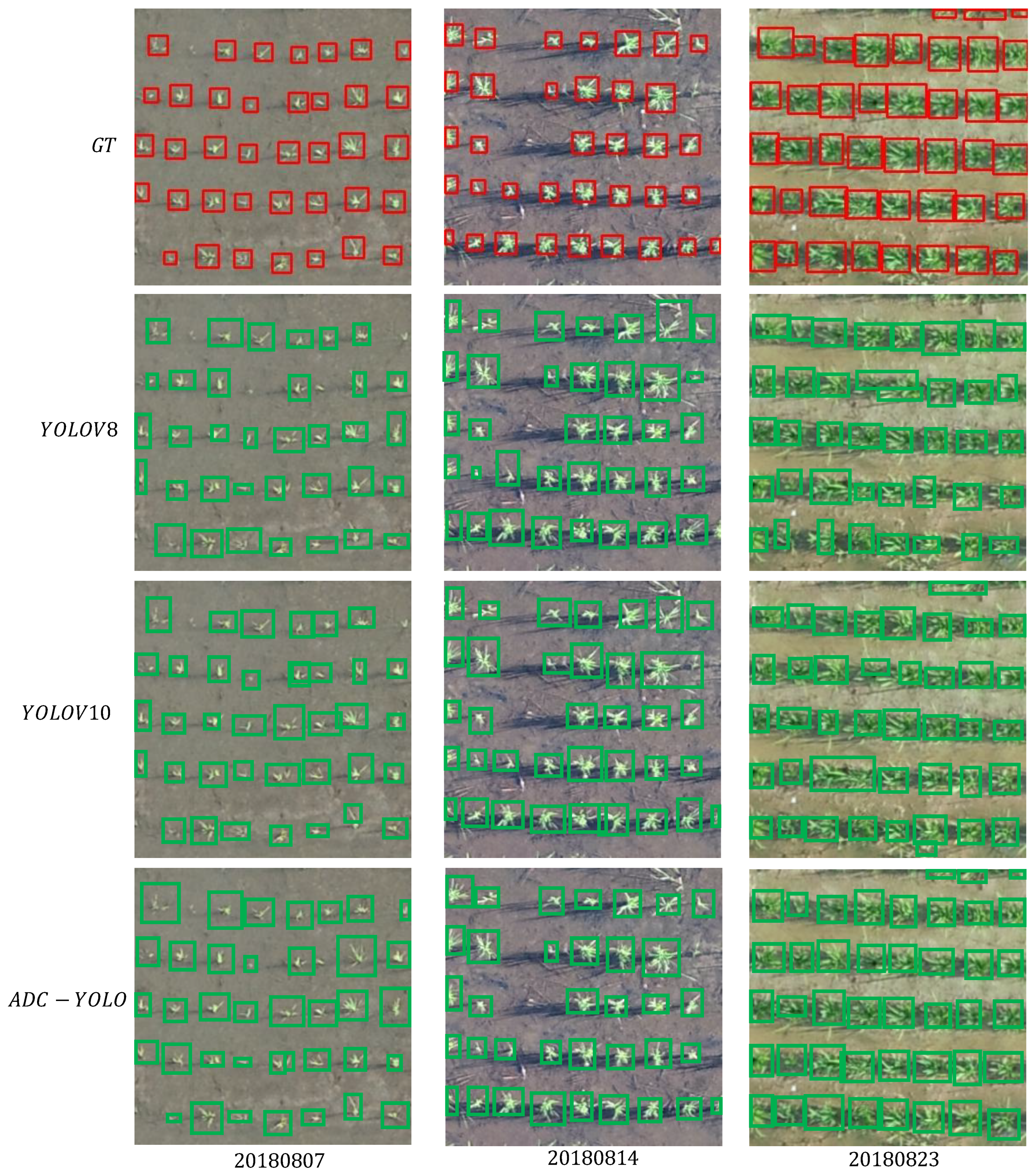

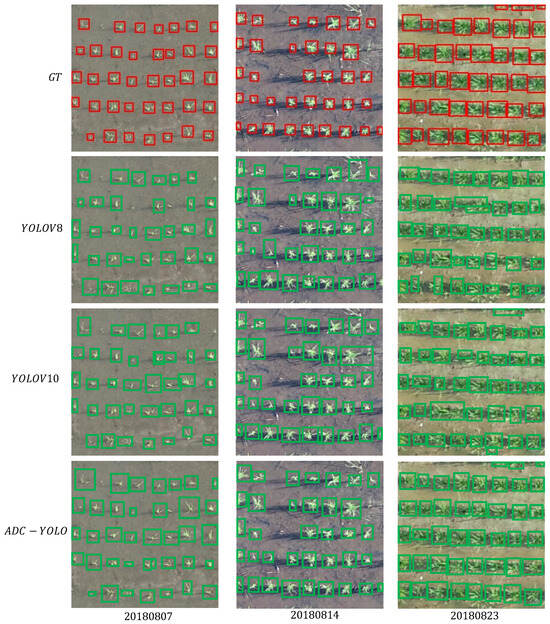

The qualitative comparison results of different methods tested on data with varying maturity levels from different dates are shown in Figure 5. From the visual comparison in the temporal dimension (different collection dates correspond to maturity gradients), it can be inferred that the advantages of ADC-YOLO become more significant as the scene complexity increases. In the seedling stage (1st column), YOLOv8 and YOLOv10 have a high missed detection rate for tiny edge seedlings, while ADC-YOLO strengthens weak features through the adaptive perception dynamic convolution module, achieving complete coverage with bounding boxes. In the second column, the bounding boxes of comparative models tend to deviate from the main veins of stems, whereas ADC-YOLO’s detection boxes are more aligned with the geometric centers of plants. In the third column, YOLOv8 and YOLOv10 exhibit box fusion or fragmentation in leaf overlapping areas, while ADC-YOLO achieves accurate differentiation and independent bounding of overlapping targets. This stable performance across maturity stages verifies the model’s robustness against temporal changes in rice growth.

Figure 5.

Qualitative comparison results of different methods tested on data with varying maturity levels from different dates.

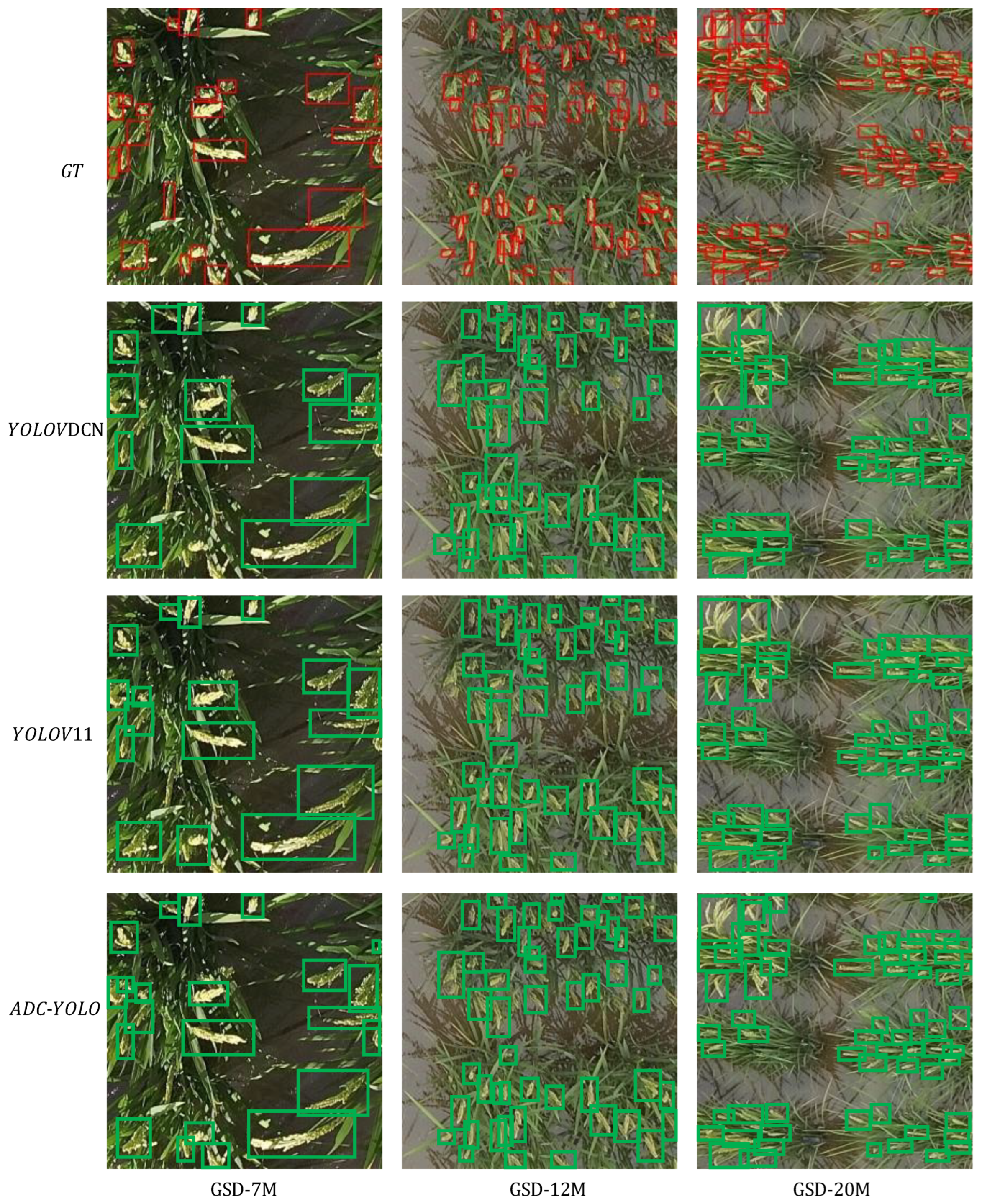

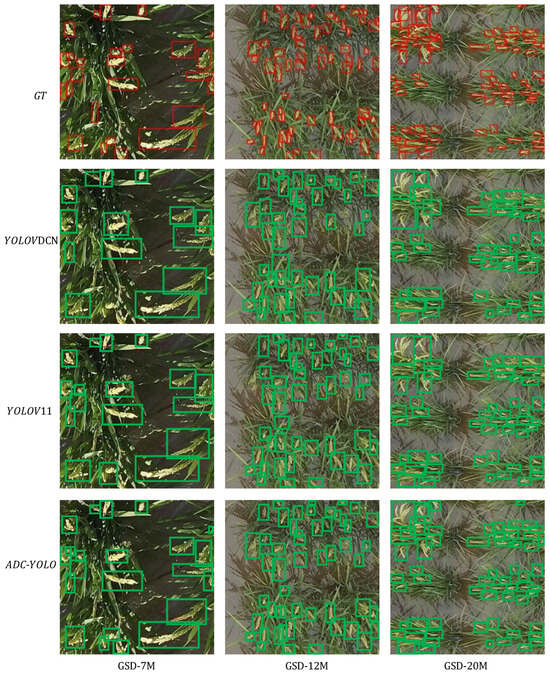

Figure 6 presents the qualitative comparison results of rice panicle detection by different methods under different GSD altitudes (7 m, 12 m, and 20 m) on the DRPD dataset. The detection boxes of YOLODCN and YOLOV11 exhibit missed detections or boundary matching deviations; in contrast, by leveraging the Adaptive Perceptual Dynamic Convolution, ADC-YOLO accurately distinguishes overlapping panicles, and its detection boxes show better consistency with the ground truth.

Figure 6.

Qualitative comparison results of different methods tested on the DRPD dataset.

4.5. Ablation Experiments

Ablation experiments were conducted on the Rice Seedling Dataset (RiceS), and the results are shown in Table 4. “ADC-YOLO without DS_C3K2” refers to the model where the DS_C3K2 module in ADC-YOLO is replaced with ordinary convolutional layers; “ADC-YOLO without ADCB” refers to the model where the ADCB module in ADC-YOLO is replaced with ordinary convolutional layers. The results verify the effectiveness of the modules proposed in this study.

Table 4.

Comparative ablation experiment results on the RiceS dataset.

5. Conclusions

To address the core contradiction between “morphological heterogeneity across growth cycles” and “scale rigidity of traditional convolution” in UAV-based rice remote sensing detection, this study proposes the ADC-YOLO model and its core module ADCB. Through a dual-subnetwork collaborative mechanism, ADCB realizes for the first time the adaptive morphological parameterization and spatial modulation of pixel-specific convolution kernels, breaking the prior constraints of fixed-kernel convolution and enabling the convolution process to naturally adapt to the dynamic morphological changes of rice throughout its entire growth cycle. Experimental validation demonstrates that the proposed model significantly outperforms current mainstream object detection algorithms in the key metrics of AP50 and AP75. Specifically, it achieves an AP50 of 99.72% on the publicly available Rice Seedling Dataset and 89.84% on the DRPD public dataset, addressing the shortcomings of existing models in the robustness of cross-cycle rice detection. This study not only provides an efficient algorithmic paradigm for crop detection but also, through deep adaptation to agricultural scenarios’ requirements, lays a technical foundation for practical applications such as precision rice cultivation. In the future, it can be further optimized by integrating multimodal data fusion to enhance the performance of full-lifecycle crop monitoring tasks.

Limitation: The verification of the model’s scene adaptability in this study is constrained by the industry-wide common bottlenecks of public datasets in the field of rice detection. On the one hand, existing public datasets generally suffer from limited sample sizes and insufficient coverage of planting scenarios and growth environments, which makes it difficult to adequately support the verification of the model’s generalization ability under diverse field conditions. On the other hand, rice images captured under extreme weather conditions—such as leaf adhesion after heavy rainfall, strong light reflection, and dense fog occlusion—are nearly absent in public data resources, resulting in the failure to comprehensively verify the model’s performance under such complex working conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.Z. and Z.T.; methodology, B.Z.; software, B.Z.; investigation, B.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, B.Z. and H.C.; writing—review and editing, B.Z., Y.L. and Z.T.; project administration, Q.L.; funding acquisition, Z.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2023YFB3907705, “Integration and Demonstration Technology of Transparent Earth-Observing”) and the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2022YFB3904800).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in Rice Seedling Dataset at https://github.com/aipal-nchu/RiceSeedlingDataset (accessed on 14 January 2026).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yang, M.-D.; Tseng, H.-H. Rule-Based Multi-Task Deep Learning for Highly Efficient Rice Lodging Segmentation. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Tan, F.; Hou, Z.; Li, X.; Feng, A.; Li, J.; Bi, F. UAV-Based Automatic Detection of Missing Rice Seedlings Using the PCERT-DETR Model. Plants 2025, 14, 2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuan, Y.N.; Goh, K.M.; Lim, L.L. Systematic Review on Machine Learning and Computer Vision in Precision Agriculture: Applications, Trends, and Emerging Techniques. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 148, 110401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.; Zhang, D.; Wang, S.; Hu, X. Progress and Challenges in Research on Key Technologies for Laser Weed Control Robot-to-Target System. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.-D.; Hsu, Y.-C.; Tseng, W.-C.; Tseng, H.-H.; Lai, M.-H. Precision Assessment of Rice Grain Moisture Content Using UAV Multispectral Imagery and Machine Learning. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 230, 109813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokool, S.; Mahomed, M.; Kunz, R.; Clulow, A.; Sibanda, M.; Naiken, V.; Chetty, K.; Mabhaudhi, T. Crop Monitoring in Smallholder Farms Using Unmanned Aerial Vehicles to Facilitate Precision Agriculture Practices: A Scoping Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Trautman, D.; Liu, Y.; Bi, C.; Chen, W.; Ou, L.; Goebel, R. Achieving the Rewards of Smart Agriculture. Agronomy 2024, 14, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, T.H.; Cao, H.-L.; Ngo, Q.H.; Nguyen, T.T.; Makrini, I.E.; Vanderborght, B. RiGaD: An Aerial Dataset of Rice Seedlings for Assessing Germination Rates and Density. Data Brief 2024, 57, 111118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Hossen, K.; Afroge, M.; Hosen, A.; Masum, K.A.M.; Osman, M.; Joy, M.I.H.; Chowdhury, F. Effect of Different Age of Seedlings on the Growth and Yield Performance of Transplanted Aus Rice Variety. Innov. Agric. 2021, 4, e32836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, H.-H.; Yang, M.-D.; Saminathan, R.; Hsu, Y.-C.; Yang, C.-Y.; Wu, D.-H. Rice Seedling Detection in UAV Images Using Transfer Learning and Machine Learning. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; He, J.; Liu, G.; Li, D.; Hu, R.; Hu, X.; Bian, D. YOLO-EP: A Detection Algorithm to Detect Eggs of Pomacea Canaliculata in Rice Fields. Ecol. Inform. 2023, 77, 102211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandakrishnan, J.; Sangaiah, A.K.; Darmawan, H.; Son, N.K.; Lin, Y.-B.; Alenazi, M.J.F. Precise Spatial Prediction of Rice Seedlings From Large-Scale Airborne Remote Sensing Data Using Optimized Li-YOLOv9. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 2226–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hieu Luu, T.; Nguyen, T.T.; Ngo, Q.H.; Nguyen, H.C.; Phuc, P.N.K. UAV-Based Estimation of Post-Sowing Rice Plant Density Using RGB Imagery and Deep Learning across Multiple Altitudes. Front. Comput. Sci. 2025, 7, 1551326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Xu, T.; Xin, Y.; Li, J. FBRT-YOLO: Faster and Better for Real-Time Aerial Image Detection. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Ninth Aaai Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Aaai-25; Walsh, T., Shah, J., Kolter, Z., Eds.; The Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2025; Volume 39, pp. 8673–8681. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, W.; Cheng, Y.; He, J.; Zhu, X. A Review of Small Object Detection Based on Deep Learning. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 6283–6303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badgujar, C.M.; Poulose, A.; Gan, H. Agricultural Object Detection with You Only Look Once (YOLO) Algorithm: A Bibliometric and Systematic Literature Review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 223, 109090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.L.; Zhang, Z. The YOLO Framework: A Comprehensive Review of Evolution, Applications, and Benchmarks in Object Detection. Computers 2024, 13, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalingam, K.; Pazhanivelan, P.; Jagadeeswaran, R.; Prabu, P.C. YOLO Deep Learning Algorithm for Object Detection in Agriculture: A Review. J. Agric. Eng. 2024, 55, 1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzammul, M.; Li, X. Comprehensive Review of Deep Learning-Based Tiny Object Detection: Challenges, Strategies, and Future Directions. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2025, 67, 3825–3913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Dai, J.; Chen, Z.; Huang, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhu, X.; Hu, X.; Lu, T.; Lu, L.; Li, H.; et al. InternImage: Exploring Large-Scale Vision Foundation Models with Deformable Convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 14408–14419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, S.K.; Brinkhoff, J.; Robson, A.J.; Dunn, B.W. Integrating Remote Sensing and Weather Time Series for Australian Irrigated Rice Phenology Prediction. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Liu, B.; Zhu, B.; Zhen, Z.; Song, K.; Ren, J. Combining Vegetation Indices to Identify the Maize Phenological Information Based on the Shape Model. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.-Y.; Berg, A.C. SSD: Single Shot MultiBox Detector. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2016; Leibe, B., Matas, J., Sebe, N., Welling, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollar, P. Focal Loss for Dense Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2980–2988. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, K.; Bai, S.; Xie, L.; Qi, H.; Huang, Q.; Tian, Q. CenterNet: Keypoint Triplets for Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 6569–6578. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Pang, R.; Le, Q.V. EfficientDet: Scalable and Efficient Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 10781–10790. [Google Scholar]

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich Feature Hierarchies for Accurate Object Detection and Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 580–587. [Google Scholar]

- Girshick, R. Fast R-CNN. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 1440–1448. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollar, P.; Girshick, R. Mask R-CNN. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2961–2969. [Google Scholar]

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-End Object Detection with Transformers. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2020; Vedaldi, A., Bischof, H., Brox, T., Frahm, J.-M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Wei, H.; Lin, M.; Deng, Y.; Sheng, K.; Zhang, M.; Tang, F.; Dong, W.; Huang, F.; Xu, C. Transformers in Computational Visual Media: A Survey. Comput. Vis. Media 2022, 8, 33–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jocher, G.; Chaurasia, A.; Stoken, A.; Borovec, J.; NanoCode012; Kwon, Y.; Michael, K.; Xie, T.; Fang, J.; Imyhxy; et al. Ultralytics/Yolov5, V7.0. YOLOv5 SOTA Realtime Instance Segmentation. Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z.; Liu, S.; Wang, F.; Li, Z.; Sun, J. YOLOX: Exceeding YOLO Series in 2021. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.08430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.-Y.M. YOLOv7: Trainable Bag-of-Freebies Sets New State-of-the-Art for Real-Time Object Detectors. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 7464–7475. [Google Scholar]

- Sohan, M.; Sai Ram, T.; Reddy, C.V.R. A Review on YOLOv8 and Its Advancements. In Proceedings of the Data Intelligence and Cognitive Informatics; Jacob, I.J., Piramuthu, S., Falkowski-Gilski, P., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 529–545. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, K.; Lin, Z.; Han, J.; Ding, G. YOLOv10: Real-Time End-to-End Object Detection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.14458. [Google Scholar]

- YOLOv11: An Overview of the Key Architectural Enhancements-All Databases. Available online: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/alldb/full-record/PPRN:118788157 (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Jiang, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, J.; Li, F.; Wu, Z. YOLOv4-Dense: A Smaller and Faster YOLOv4 for Real-Time Edge-Device Based Object Detection in Traffic Scene. IET Image Process. 2023, 17, 570–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ahmed, K.; Khan, M.I.; Wang, H.; Qu, Y. YOLO-FCE: A Feature and Clustering Enhanced Object Detection Model for Species Classification. Pattern Recognit. 2026, 171, 112218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Yu, J.; Zhang, H.; Dong, X. AED-YOLO11: A Small Object Detection Model Based on YOLO11. Digit. Signal Prog. 2025, 166, 105411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Cui, M.; Chen, Z.; Ma, Y.; Yu, S. MFR-YOLOv10:Object Detection in UAV-Taken Images Based on Multilayer Feature Reconstruction Network. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2025, 38, 103456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xiang, J.; Jin, Y.; Liu, R.; Yan, J.; Wang, L. Boost Precision Agriculture with Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Remote Sensing and Edge Intelligence: A Survey. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.A.O.S.; Siqueira, V.S.d.; Mesquita, M.; Vale, L.S.R.; Marques, T.d.N.B.; Silva, J.L.B.d.; Silva, M.V.d.; Lacerda, L.N.; Oliveira-Júnior, J.F.d.; Lima, J.L.M.P.d.; et al. Deep Learning for Weed Detection and Segmentation in Agricultural Crops Using Images Captured by an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Lu, Y.; Wang, H. Performance Evaluation of Deep Learning Object Detectors for Weed Detection for Cotton. Smart Agric. Technol. 2023, 3, 100126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltık, A.O.; Allmendinger, A.; Stein, A. Comparative Analysis of YOLOv9, YOLOv10 and RT-DETR for Real-Time Weed Detection. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2024 Workshops; Del Bue, A., Canton, C., Pont-Tuset, J., Tommasi, T., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 177–193. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo, I.; Rehman, A.U.; Dehkordi, R.H.; Landro, N.; La Grassa, R.; Boschetti, M. Deep Object Detection of Crop Weeds: Performance of YOLOv7 on a Real Case Dataset from UAV Images. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangaiah, A.K.; Anandakrishnan, J.; Devarapelly, A.R.; Mohamad, M.L.A.B.; Bian, G.-B.; Alenazi, M.J.F.; AlQahtani, S.A. R-UAV-Net: Enhanced YOLOv4 With Graph-Semantic Compression for Transformative UAV Sensing in Paddy Agronomy. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Commun. Netw. 2025, 11, 1197–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Fan, X.; Bo, W.; Yang, X.; Tjahjadi, T.; Jin, S. A Multiscale Point-Supervised Network for Counting Maize Tassels in the Wild. Plant Phenomics 2023, 5, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anuar, M.M.; Halin, A.A.; Perumal, T.; Kalantar, B. Aerial Imagery Paddy Seedlings Inspection Using Deep Learning. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Lu, H.; Li, Y.; Cao, Z. High-Throughput Rice Density Estimation from Transplantation to Tillering Stages Using Deep Networks. Plant Phenomics 2020, 2020, 1375957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, N.; Gong, Y.; Fang, S.; Liu, Y.; Duan, B.; Yang, K.; Wu, X.; Zhu, R. UAV Remote Sensing Estimation of Rice Yield Based on Adaptive Spectral Endmembers and Bilinear Mixing Model. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xin, R.; Jiang, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yu, J. Refined Feature Fusion for In-Field High-Density and Multi-Scale Rice Panicle Counting in UAV Images. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 211, 108032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Gu, S.; Liu, P.; Yang, A.; Cai, Z.; Wang, J.; Yao, J. RPNet: Rice Plant Counting after Tillering Stage Based on Plant Attention and Multiple Supervision Network. Crop J. 2023, 11, 1586–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.; Li, W.; Chen, L.; Zou, H.; Zhang, R.; Qiu, Z.; Yang, S.; Shen, Y. Rice Counting and Localization in Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Imagery Using Enhanced Feature Fusion. Agronomy 2024, 14, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Deng, N.; Mi, S.; Zhou, R.; Chen, Y.; Deng, Y.; Fang, K. Automatic Counting and Location of Rice Seedlings in Low Altitude UAV Images Based on Point Supervision. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejasri, N.; Li, T.; Guo, W.; Rajalaksmi, P.; Balram, M.; Desai, U.B. Improved Panicle Counting With Density-Aware Sampling and Enhanced Matching. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2025, 22, 2504205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertical/YOLOv8: YOLOv8 🚀 in PyTorch > ONNX > CoreML > TFLite. Available online: https://github.com/Pertical/YOLOv8/tree/main (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.-C. Mobilenetv2: Inverted Residuals and Linear Bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 4510–4520. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.-D.; Tseng, H.-H.; Hsu, Y.-C.; Yang, C.-Y.; Lai, M.-H.; Wu, D.-H. A UAV Open Dataset of Rice Paddies for Deep Learning Practice. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhan, W.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, H. FRPNet: A Lightweight Multi-Altitude Field Rice Panicle Detection and Counting Network Based on Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Images. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Dong, N.; Gu, J.; Cheng, H.; Meng, Z.; Du, X. STRAW-YOLO: A Detection Method for Strawberry Fruits Targets and Key Points. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 230, 109853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.