Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Hyperspectral data from the future CHIME mission, as well as thermal data from the future LSTM ESA mission, can be simulated from existing spaceborne and airborne sensors’ data sets using either a simple “mimicking” approach or a more complex atmospheric propagation model.

- These CHIME- and LSTM-simulated data sets can be used to characterize urban materials and the thermal properties of the areas inside a city, which are the most important ones with respect to urban heat island effect monitoring.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- Even before launching the CHIME and LTSM missions, it is possible to effectively build synthetic data sets for these sensors on selected test areas and pre-evaluate different algorithms for the exploitation of the data sets from these future missions for urban and/or environmental applications.

- By using a combined set of hyperspectral and thermal data, which are unavailable right now and will become available with the launch of ESA’s CHIME and LSTM missions, it is possible to extract initial information about urban heat island effects and their relationship with urban materials, with the aim to implement a more heat-wise urban planning.

Abstract

The aim of this research is to investigate potential uses of the CHIME and LSTM missions for urban climate research. Therefore, this paper initially introduces two methodologies to obtain synthetic images for these future ESA missions starting from existing airborne or spaceborne data sets. Subsequently, this work shows to what extent these synthetic CHIME and LSTM data sets can be used to characterize urban materials and their thermal properties, with the final aim of better management of the urban heat island effect. Spectral unmixing using database spectra of urban materials or image-driven endmembers is applied to synthetic data for Athens, Greece, obtained from ESA’s THERMOPOLIS-2009 airborne campaign or the PRISMA mission, together with ECOSTRESS data sets. Experimental results on two neighborhoods of the city of Athens show that these synthetic data have the potential to extract urban material maps, but the limitations suffered by these data suggest that using image-driven endmembers is the most effective choice towards more accurate results.

1. Introduction

Since 1950, urban areas have grown rapidly, and in 2007, the urban population surpassed the rural one for the first time [1]. Ongoing urbanization has led to widespread conversion of natural landscapes into impervious surfaces, increased emissions of greenhouse gases and air pollutants, and caused significant disruptions to natural biogeochemical cycles [2,3]. As a result, urban areas face rising temperatures, poor air quality, higher energy demand, and extreme weather events with far-reaching health, economic, and ecological consequences [4,5,6,7]. Today, urban areas contribute about 70% of carbon emissions and face significant climate change impacts [4,8], playing a crucial role in global sustainability. As such, scientific communities across many fields are calling for more science-based insights into urban systems [9,10,11].

Remote sensing is an essential tool in urban research [12,13,14,15,16], providing globally consistent data on land cover, land surface temperature (LST), vegetation, imperviousness, and urban sprawl, all of which support studies on urban planning and sustainability. Existing satellite missions capable of resolving urban features at fine spatial scales (≤100 m) often lack the spectral and temporal resolution as well as the coverage needed to generate advanced products, such as high-resolution maps of urban materials, that are essential for climate adaptation and mitigation and for modeling the urban climate. The upcoming Copernicus Expansion Missions, namely the Land Surface Temperature Monitoring (LSTM) [17] and the Copernicus Hyperspectral Imaging Mission for the Environment (CHIME) [18], are designed to provide data that overcomes some of these limitations. As part of the Sentinel Expansion missions, LSTM and CHIME will enhance the capabilities of Copernicus, the Earth Observation (EO) element of the European Union (EU) space program, to address EU policy and user needs and enable unprecedented high-resolution mapping of urban surface temperatures, evapotranspiration, and material composition in every city across the globe.

The Sentinel Users Preparation (SUP) initiative, which is funded by the European Space Agency (ESA), is a preparatory program for the use of Copernicus Expansion missions and Sentinel Next Generation missions that aims to prepare future downstream services that address high-priority societal challenges and to enable rapid uptake by end-users and stakeholders of the developed products. Specifically, SUP will develop and test methodologies in existing application domains to both consolidate the added value of the Copernicus Sentinel Expansion missions for such applications and to build the relevant experience and expertise within both supply-side and demand-side stakeholders. HEATWISE (High-resolution Enhanced Analysis Tool for Urban Hyperspectral and Infrared Satellite Evaluation), one of the SUP projects focusing on urban resilience, aims to develop three data application products based on the future data that will become available from CHIME and LSTM missions: (i) maps of urban materials; (ii) maps of Local Climate Zones (LCZ) [19]; and (iii) biogeochemical and physical characterizations of urban water bodies. In this paper, we focus on urban material maps.

For the development of these application products, as the LSTM and CHIME missions are still under development, this work introduces first two methodologies to produce a representative dataset fulfilling the spatial, spectral and temporal characteristics of the two satellite instruments, using hyperspectral Visible, Near and Shortwave Infrared (VSWIR) and multispectral Thermal Infrared (TIR) data from existing spaceborne and airborne instruments. Beyond its role in HEATWISE, the produced dataset is also intended to serve as a resource of broader value, supporting the wider community engaged in developing products that will use CHIME and LSTM data.

The HEATWISE representative dataset provides CHIME- and LSTM-like Level 2 products, i.e., surface reflectance and LST that have been generated using two complementary approaches: (i) radiative transfer modeling using the Matrix-Operator Model (MOMO) [20]; and (ii) transformation of existing hyperspectral and multispectral imagery through resampling and filtering. We label the former results as “simulated” and the latter as “mimicked”. The first objective of this paper is to describe the methods used to derive these datasets and the remote sensing data used as a basis. The second part of the paper shows how these data could be used for urban material recognition, one of the products of the project, and its limitations with respect to this task.

The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides an overview of the LSTM and CHIME missions, Section 3 introduces the datasets and methods, Section 4 presents the simulated and mimicked data for two areas in Athens and the results of mapping the most abundant material in these areas using the simulated data sets, while Section 5 and Section 6 discuss the results and our conclusions.

2. The CHIME and LSTM Missions

2.1. The CHIME Mission

CHIME represents a significant step forward in ESA’s ongoing efforts to revolutionize environmental monitoring and resource management. The primary mission of CHIME is to provide high-resolution, hyperspectral data to support critical sectors such as agriculture, forestry, raw materials management, biodiversity conservation, and water resources. This mission aligns with the growing demand for actionable environmental data to address pressing global challenges, including food security, climate change, and ecosystem degradation. The hyperspectral technology onboard CHIME offers unprecedented diagnostic capabilities, enabling detailed observation and analysis of Earth’s surface composition and dynamics.

CHIME’s mission architecture [18] includes a two-satellite constellation in sun-synchronous orbit (~632 km, 10:45 Local Time of the Ascending Node, LTAN, swath width 130 km), CHIME-A planned for launch in 2028, and CHIME-B planned for launch in 2030, with an expected operational life of 8 years. The constellation of hyperspectral satellites is designed to deliver comprehensive global coverage of land surfaces, inland waters, and coastal zones between −56° and +84°.

CHIME’s HyperSpectral Imager (HIS) can measure at a ground resolution of 30 m for a swath width of 130 km with high radiometric accuracy for Level-1B data. It is an advanced hyperspectral imager that can capture images in over 200 bands over a wavelength range of 400–2500 nm in the Visible (VIS), Near Infrared (NIR), and Short-Wave Infrared (SWIR) spectrum with ≤10 nm spectral sampling in over 200 contiguous bands, using three pushbroom spectrometers with passively cooled Mercury Cadmium Telluride (MCT) detectors to ensure high uniformity. With two satellites, the nominal revisit improves from ~22 to ~11 days at the equator.

2.2. The LSTM Mission

The LSTM mission will complement the existing family of Copernicus satellites by providing high-resolution VSWIR and TIR observation capabilities over land and coastal areas. The mission’s primary objective, as defined in [21], is to enable the monitoring of evapotranspiration rates at the field scale by capturing the variability of LST and emissivity, thereby allowing robust estimates of field-scale water productivity but also to support a range of additional services such as Surface Urban Heat Island (SUHI) studies, coastal zone management, and soil composition. The LSTM mission will consist of two satellites: LSTM-A, planned for launch in 2028, and LSTM-B, planned for launch in 2030, with an expected operational lifetime of 7.5 years. The mission will systematically observe land and inland water areas between latitudes −56° and +84°, including major islands, coastal waters, and potentially, exclusive offshore economic zones. Observations are planned at a mean local solar time of 12:30. The mission aims for a revisit time of two days when both satellites are in-orbit and will provide a swath width exceeding 670 km at an altitude of ~650 km, enabling wide-area monitoring in a single pass.

The mission’s main instrument is the Land Surface Temperature Radiometer (LSTR), which is an in-plane whiskbroom scanner that will provide ΤIR data with a spatial resolution of 50 m. LSTR includes five spectral bands in the 8.6–12.0 µm range, with the center wavelengths and bandwidths shown in Table 1. Additionally, six VSWIR spectral bands in the 0.49–1.61 µm range will be included to support the Land Surface Emissivity (LSE) retrieval, water vapor estimation, cloud detection, and accurate geolocation. The dynamic range of the LSTR should be able to cover a wide temperature range, from approximately −20 °C to 30 °C, with a precision of 0.3 °C [17]. The maximum observation zenith angle will be approximately 30°.

Table 1.

LSTM spectral bands with central wavelengths, spectral ranges, nominal full-width-at-half maximum (FWHM), provisional band names, and main uses, as defined in [21].

The LSTM data products are organized into two levels: Level 1c products provide radiometrically and geometrically calibrated TOA radiances and Brightness Temperatures, while the Level 2 products will deliver geophysical parameters such as LST, land surface emissivity per TIR band, BOA surface reflectance, total column water, and a cloud mask.

3. Materials and Methods

The aim of this research is to evaluate how well emulated CHIME and LSTM data can be used for urban material characterization using hyperspectral unmixing. Accordingly, this section will first describe the selected areas and the available data sets that have been used to simulate the representative data sets for the two missions. Moreover, it will summarize the unmixing techniques used to extract urban material maps.

3.1. Pilot Areas

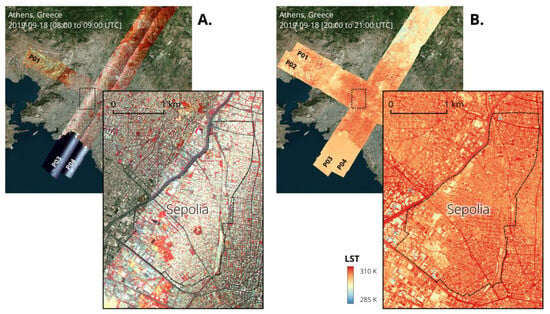

Athens, Greece (37.98°N, 23.72°E), was selected as the main pilot area of HEATWISE. Athens is a coastal Mediterranean city with hot, dry summers and mild winters, and is the second most densely populated area in Europe, with 10,436 people per km2. The cityscape is dominated by compact building structures, extensive concrete and asphalt surfaces, and narrow streets, with very limited green spaces. These features contribute to a pronounced Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect, while the frequency and intensity of heatwaves have increased markedly over the past decades [7,22,23]. In collaboration with local stakeholders, the HEATWISE team focused on two neighborhoods in the Municipality of Athens: Sepolia, a socially vulnerable residential neighborhood with limited green infrastructure; and the Athens City Center, a dense commercial and administrative hub with high daytime population and intense heat exposure.

3.2. Athens Airborne and Spaceborne Datasets

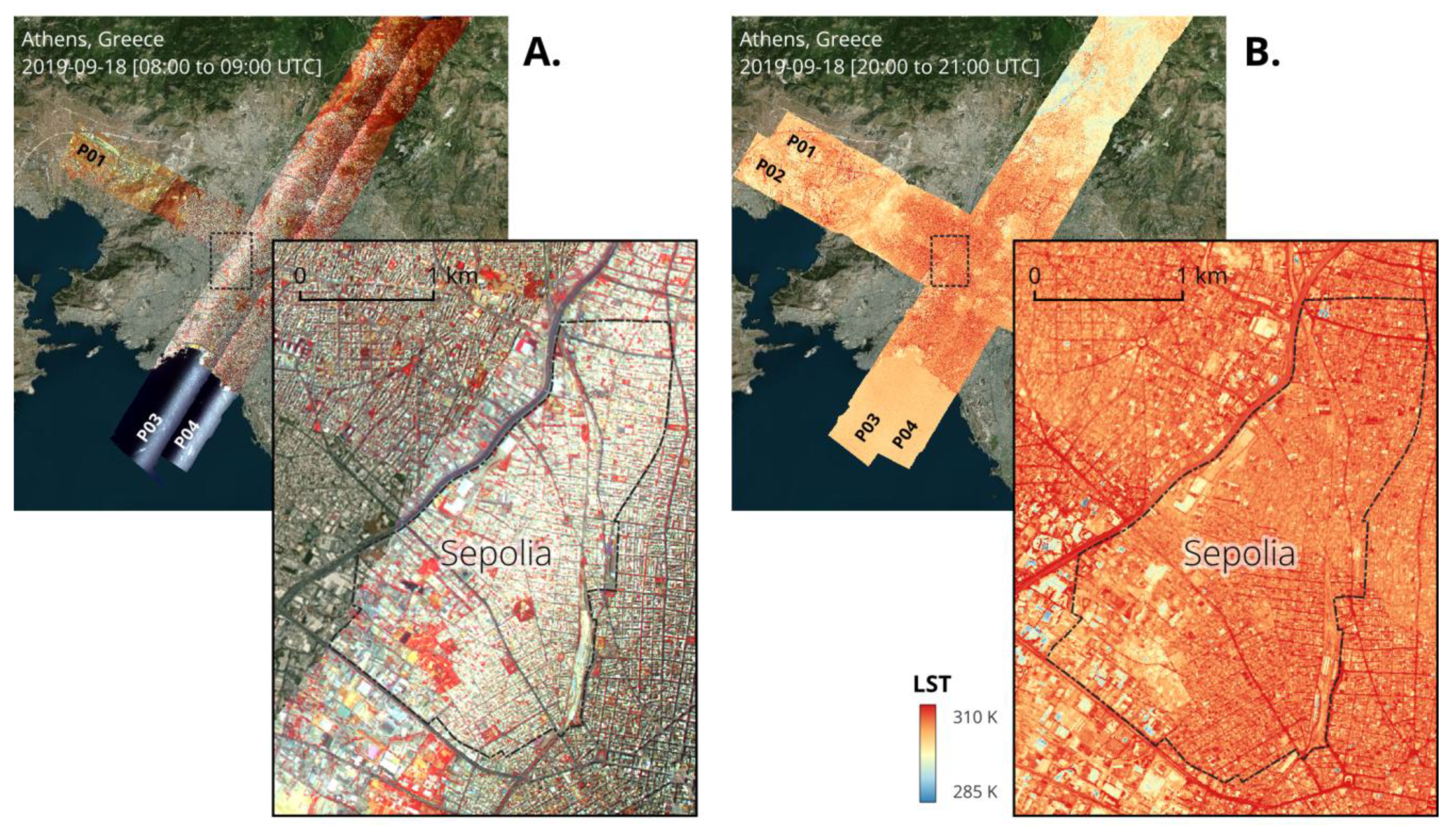

For the Athens pilot areas, the airborne data used to generate the HEATWISE representative datasets were obtained from ESA’s THERMOPOLIS-2009 campaign, conducted between 15 July and 2 August 2009 [24,25]. A few examples of the resulting datasets are shown in Figure 1. During that period, coordinated airborne hyperspectral, spaceborne, and in-situ measurements were collected to generate spectrally, geometrically, and radiometrically representative datasets for sSUHI studies. The airborne remote sensing data were collected using the Airborne Hyperspectral Scanner (AHS), an imaging line-scanner radiometer operated by INTA (Spain’s National Institute of Aerospace Technology). A total of four daytime and three nighttime flights were conducted (Table 2). The AHS instrument developed by SensyTech Inc. (Newington, VA, USA) measures radiances across 80 spectral bands: 20 in the Visible and Near InfraRed (VNIR), 43 on the Short-Wave InfraRed (SWIR), 7 in the Mid InfraRed (MIR), and 10 in the Thermal InfraRed (TIR). The data of the THERMOPOLIS-2009 campaign, recorded from an altitude of 1905 m, were processed into three Level 2 products with a 4 m spatial resolution: the VNIR BOA reflectance, the LST, and the LSE. The VNIR surface reflectance was retrieved by inverting the radiative transfer equation using the MODTRAN-4 radiative transfer code. Validation with in-situ spectra from a GER-1500 spectroradiometer showed a Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of 0.06 reflectance units for AHS bands 9 and 12 over bare soil, green grass, and concrete. The LST and LSE were retrieved from the AHS TIR radiances using the Temperature and Emissivity Separation (TES) algorithm. A noisy signal was detected in AHS band 78, which was therefore excluded from LST and LSE retrievals. Validation of the TES-derived LST indicated an RMSE of 1.6 K.

Figure 1.

THERMOPOLIS-2009 4 m resolution imagery acquired on 18 July 2009, over Athens, Greece. Panel (A) displays a false color composite of daytime VNIR data, while panel (B) presents nighttime land surface temperature (LST) data. The inset highlights Sepolia, a designated focus area within the HEATWISE project.

Table 2.

The THERMOPOLIS-2009 air campaigns in Athens, Greece.

Additional processing was later performed by the HEATWISE team to atmospherically correct the remaining VSWIR radiances using the 6S (Second Simulation of a Satellite Signal in the Solar Spectrum) radiative transfer code over the districts of Sepolia and Athens city center.

The Athens case study is supported by a comprehensive yet carefully curated hyperspectral dataset derived from the Italian Space Agency’s PRISMA mission. PRISMA, launched in 2019, acquires contiguous bands in VNIR and SWIR regions at 30 m spatial resolution, complemented by a 5 m panchromatic band. This combination of broad spectral coverage and relatively fine spatial detail makes PRISMA the closest currently operational analogue to the forthcoming Copernicus CHIME mission and therefore an invaluable source of information for HEATWISE activities.

In detail, between 2021 and 2024, a total of 57 PRISMA acquisitions were identified over the Sepolia district and the broader Athens metropolitan area. A rigorous screening process was applied to retain only products with less than 20% cloud cover, thereby ensuring high spectral integrity for urban applications where shadowing and cloud contamination can severely distort reflectance signals. Each retained image was subsequently catalogued and temporally aligned within a common framework spanning the 2021–2024 period, facilitating seasonal and interannual analyses of urban surface conditions. This temporal organization allows the project to investigate not only static features but also potential changes in spectral signatures associated with vegetation cycles, maintenance or replacement of urban materials, and episodic events such as heatwaves. The Athens PRISMA dataset serves as input for CHIME-like convolution experiments, supporting the calibration of spectral resampling functions and the evaluation of the quality of the most abundant urban materials at 30 m spatial resolution under conditions representative of a densely-populated Mediterranean city.

3.3. Methods

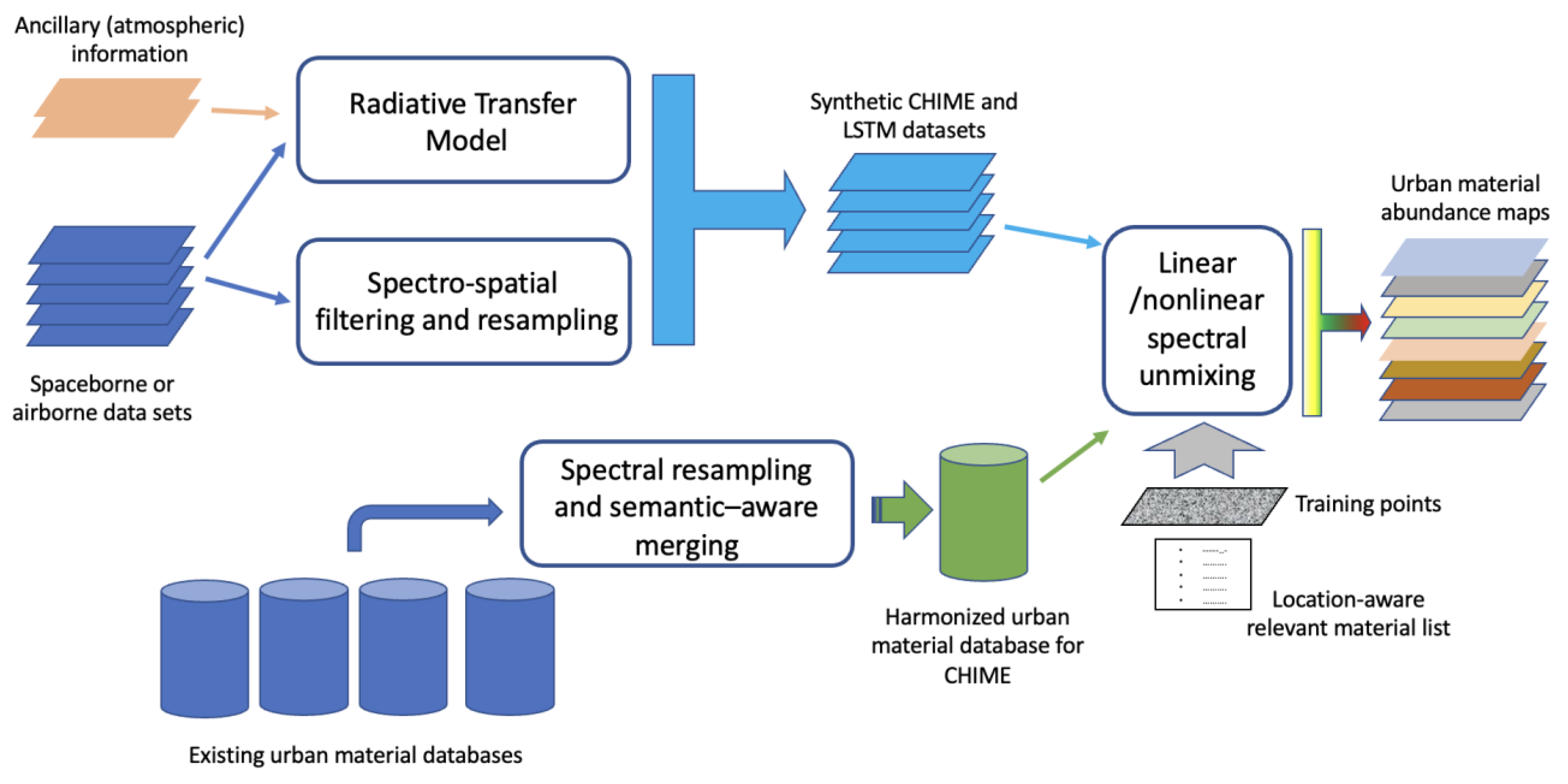

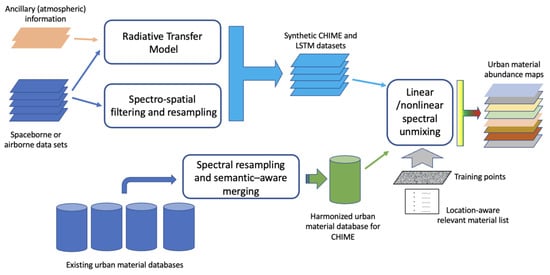

The overall workflow of the methods used in this research is proposed in Figure 2 and includes three main steps. The first portion of the processing chain is devoted to the production of the synthetic CHIME and LSTM data sets by using a radiative transfer model (“simulated” data sets) and a much simpler spectro-spatial resampling approach (“mimicked” data sets), both based on existing data sets for the area of interest. The second part of the chain aims at extracting urban material abundances and features and preparing for several experiments performed to compare simulated and mimicked data sets, initializing the unmixing procedure by using endmember spectra from a harmonized database of urban materials or image-driven spectra from known locations.

Figure 2.

Overall workflow of the methods exploited in this research.

3.3.1. CHIME and LSTM Data Simulation Methodology

Central to the effort of simulating LSTM and CHIME measurements is the radiative transfer model MOMO, which enables detailed simulations of radiances and brightness temperatures under varying atmospheric and surface conditions. These radiative transfer simulations are used to emulate hyperspectral CHIME and LSTM satellite observations.

MOMO has been designed for a coupled atmosphere-ocean system including rough water or anisotropic land surfaces, aerosols, clouds, and water constituents. It simulates the complete Stokes vector for any given spectral and vertical resolution [26]. The latest extension of MOMO also enables us also to simulate hyperspectral radiances and brightness temperatures in the thermal infrared as well [20].

The most important parts in a radiative transfer code, suitable to simulate the radiative transfer processes in a combined atmosphere/water body as required for this study, are the description of the interaction of scattering and absorption as well as emission processes of atmospheric and water constituents, the adequate formulation of the gaseous absorption in the vertical structure of the atmosphere, and the incorporation of the instrumental characteristics.

The absorption due to atmospheric gases is estimated by the line-by-line code MOMO-cgasa, using the latest HITRAN-2020 database. For completeness, we choose a very high spectral resolution for the line-by-line calculations, usually 0.001 cm−1. These calculations are further used to generate the so-called k-binning for different groups of atmospheric gases, which reduces the spectral resolution without compromising the precision of the simulated atmospheric absorption. For each spectral and vertical setup, different line-by-line calculations, estimation of k-binning, as well as spectral properties of the aerosol and water constituents must be computed.

The optical properties of aerosols are estimated from a so-called Mie code, which assumes spheres that interact with radiation. Since the complex refractive index of the different aerosol components, as well as the interaction of particle size and wavelength of the incident radiation, are wavelength dependent, the phase-matrices, extinction, and single scattering albedo are calculated at all chosen wavelengths.

The MOMO simulations enable the users to consider the sun and observation geometries of CHIME and LSTM for the complete orbit. For each observation site and measurement, the solar elevation and observation geometry are calculated from the location of the site and the date of the synthetic data.

3.3.2. CHIME and LSTM Data Mimicking Methodology

The simulation methodology introduced in the previous section provides a way to extract simulated data sets for the full set of CHIME and LSTM bands, even when starting from input data that lacks measurements in some spectral regions. This result is obtained at the expense of a computationally expensive approach. Another possibility is to use the information available in the input data set to obtain, by means of a simpler and less computationally expensive technique, only a subset of the CHIME and LSTM bands. The result of this approach is labeled in this work as “mimicked” to avoid any confusion.

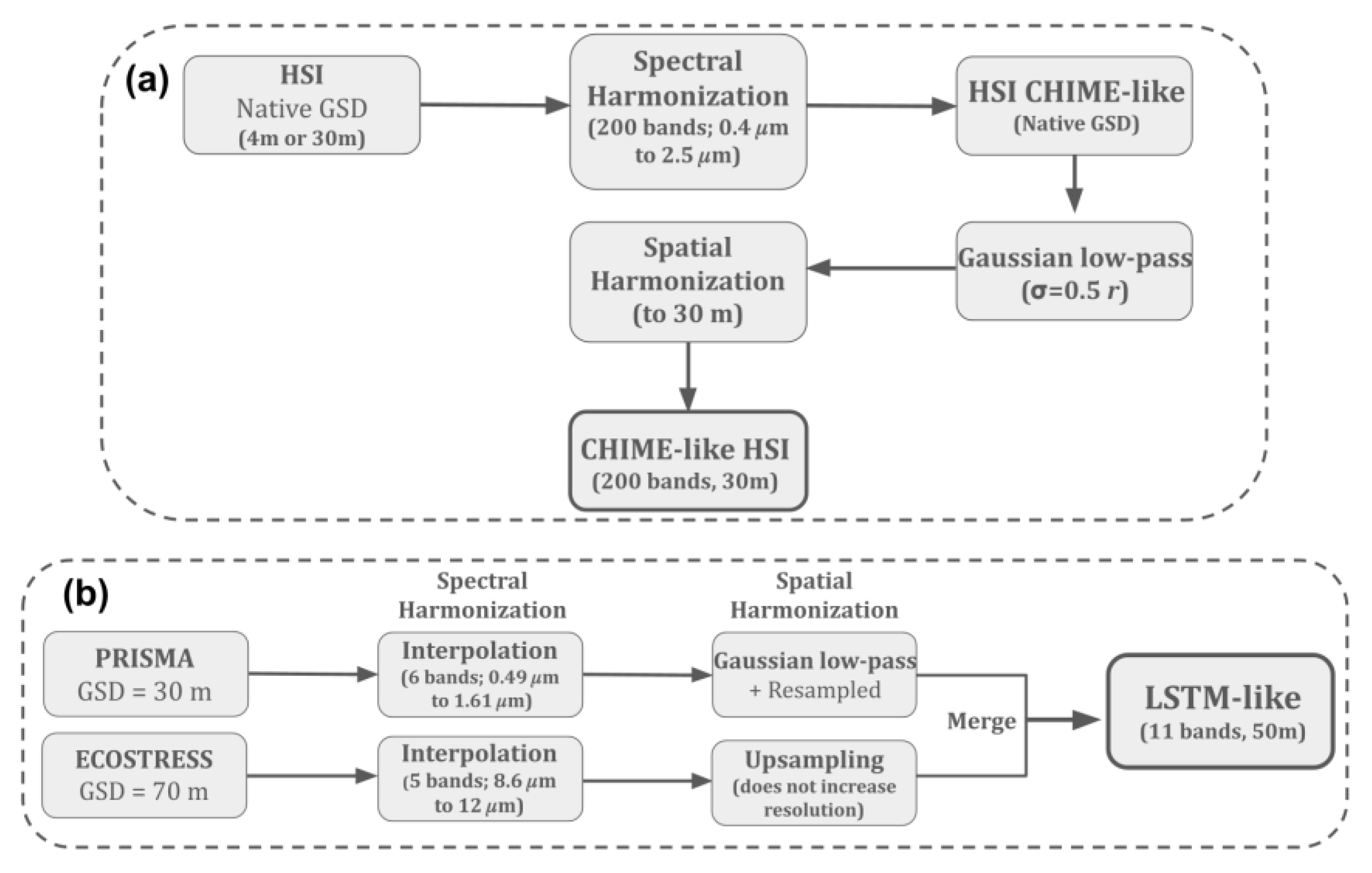

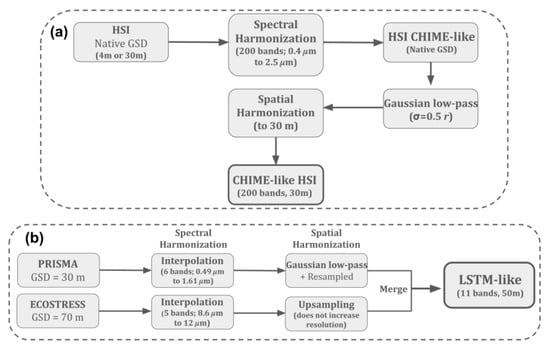

The proposed mimicking approach focuses on harmonizing multispectral Level 2 reflectance data at their native GSD (e.g., 4 m for airborne data sets or 30 m for spaceborne) to a CHIME-like GSD of 30 m. The goal is to obtain a data cube that is spectrally compatible with CHIME (whose only specifications, at the moment of this writing is to have 200 contiguous bands across the 0.40–2.50 µm wavelength range) and spatially representative of a 30 m product, while preserving the geodetic frame of the original scene and avoiding artefacts. The overall workflow is summarized in Figure 3a and includes two main steps: first, a spectral harmonization step and then a spatial harmonization step, preceded by a spatial filtering procedure.

Figure 3.

Mimicking workflows: (a) spectral harmonization to CHIME bands and conditional spatial harmonization to 30 m. (b) LSTM-like stack: PRISMA and ECOSTRESS bands are spectrally resampled, then spatially harmonized and merged into 11 band 50 m resolution.

A similar procedure is proposed for LSTM data mimicking (Figure 3b), which is achieved by considering the spectral bands and the spatial resolution of this sensor. The only difference is that, given that LSTM bands encompass VNIR/SWIR and TIR bands, the input to the procedure, in case of spaceborne starting records, must be a joint pair of PRISMA and ECOSTRESS data, which implies, even considering coregistered and very close date data sets, a certain degree of inaccuracy in the spatial and temporal alignment of the two sets of bands.

Spectral Harmonization

The spectral harmonization step is meant to remap each input spectrum to a CHIME-like, uniformly sampled grid spanning 0.40–2.50 µm. The target grid comprises ~200 samples (≈10 nm nominal spacing), which is sufficient to capture principal urban-material features across the VNIR and SWIR bands. A shape-preserving interpolation is employed along the spectral axis to avoid spurious oscillations and to maintain local monotonicity around narrow absorptions. To prevent fabrication of information, spectral regions with no physical support in the input data (e.g., strong atmospheric absorption intervals) are flagged as missing in the harmonized product. This step yields an intermediate CHIME-like spectral representation at the input geometry (see the upper branch in Figure 3).

Similarly, for LSTM, this step remaps the input spectra to the bands in Table 1, using the same shape-preserving interpolation.

Spatial Harmonization

To emulate the effective 30 m spatial resolution of CHIME and avoid aliasing when downscaling from finer grids, we apply a lowpass prefilter prior to decimation. Of course, this spatial branch is used only when the native GSD is finer than 30 m (see the lower branch in Figure 3a).

Specifically, a circularly symmetric Gaussian point-spread function (PSF) proxy approximates the combined smoothing of the instrument PSF and pixel integration. A practical sizing is

with r = (target GSD/native GSD), which delivers an effective blur consistent with a 30 m product and suppresses high-frequency content that would otherwise fold into lower spatial frequencies in the coarser lattice. More precisely, the prefilter is chosen so that the modulation transfer function (MTF) at the 30 m Nyquist frequency is on the order of ≈0.25, consistent with CHIME design; this aligns the contrast roll-off of the mimicked image with that expected for a genuine 30 m system and ensures proper anti-aliasing prior to decimation. After prefiltering, the data are resampled to 30 m on a CHIME-like map geometry using an area-averaging operator, preserving radiometric consistency (energy conservation in reflectance units). All operations preserve the original CRS and tie points; pixels lacking valid support after resampling are retained as missing values.

The mimicking step delivers CHIME-like reflectance cubes at 30 m GSD that are georeferenced and co-registered across bands, while preserving the BOA reflectance provided by the Level 2 inputs. The approach targets spectral sampling and effective spatial resolution consistent with CHIME specifications, without modeling sensor-specific spectral response functions or anisotropic PSFs; where higher instrument fidelity is required, SRF convolution and directional PSF matching can be incorporated as future refinements.

Similarly, for LSTM, the same steps are applied, but with a target GSD of 50 m. If the input is composed of two different data sets with different spatial resolutions (e.g., PRISMA and ECOSTRESS), this implies that different filtering and resampling are applied to each set.

Instantiation on Airborne and Spaceborne Input Data Sets

Applying the above procedure to the THERMOPOLIS-2009 AHS Level 2 data, which have a native spatial resolution of 4 m, requires applying the spectral harmonization module as well as the spatial harmonization module to obtain a CHIME-like data cube at 30 m and an LSTM-like data cube at 50 m.

By contrast, when building CHIME-like products from PRISMA/EnMAP (native 30 m), only the spectral harmonization to the CHIME grid is required because the spatial sampling already matches the 30 m target. For ECOSTRESS, whose native pixel size is 70 m, both spectral and spatial harmonization are needed to emulate LSTM: we first adapt the TIR bands to the LSTM spectral response, and then resample from 70 m to the 50 m LSTM grid via a simple interpolation step (this does not increase resolution, only preserves the desired grid). Likewise, when generating LSTM-like VNIR/SWIR layers from 30 m optical data (PRISMA/EnMAP), we apply both steps: spectral harmonization and spatial degradation to 50 m.

3.3.3. Hyperspectral Unmixing Methodologies

We estimate per-pixel material abundances over the CHIME-like reflectance cubes using a supervised linear mixing formulation [27]. Let denote the harmonized data cube (with L spectral bands and N pixels) and the endmember matrix built from the urban spectral library described in Section 3.3.4 (resampled to the CHIME-like grid and aggregated by class). Abundances are sought under the Linear Mixing Model (LMM),

where N collects residuals. Bands flagged as unsupported or affected by strong atmospheric absorption during spectral harmonization (Section 3.3.2) are excluded from both Y and E prior to unmixing, so the inversion is performed on a consistent set of wavelengths.

Abundances are constrained to be non-negative and to sum to one per pixel. For a single pixel with abundance vector , we enforce

We adopt two complementary estimators implemented within the HySUPP framework [28,29], (a reproducible pipeline for supervised linear spectral unmixing). The first is Fully Constrained Least Squares (FCLS) [30], which solves the constrained quadratic program independently for each pixel. FCLS is a classical, well-posed baseline under the LMM assumptions and provides stable, interpretable abundance maps when the library spans the scene simplex.

The second estimator is UnDIP (Unmixing via Deep Image Prior) [31]. Here, a lightweight convolutional decoder produces a multi-channel abundance field that is mapped through a per-pixel Softmax function, which enforces both non-negativity and sum-to-one by construction. The network parameters are optimized to minimize the reconstruction loss between the observed spectra and their linear reconstructions Ea. Unlike generic supervised deep networks, UnDIP does not require external training data; the image-specific prior acts as a regularizer while preserving the physical linear-mixing structure.

Endmember selection and preparation are described in Section 3.3.4. Briefly, spectra are curated by urban class (e.g., asphalt, concrete, roof types, metals, artificial soils), resampled to the CHIME-like grid, and aggregated by the class median to mitigate outliers and small-scale surface variability. All experiments reported here were run without L2 normalization of spectra or pixels; although HySUPP supports optional normalization and subspace projection, these options were not used in the analyses presented in this paper. Visual consistency checks, comparison across sensors (PRISMA vs. CHIME-mimicked-like), and agreements with expected urban patterns are used to assess plausibility in the Section 4.

Two region-specific endmember libraries were used, one for Sepolia and one for Athens City Centre (Section 3.3.4). Each region was unmixed exclusively with its corresponding library; within region, the same endmember set was kept across sensors and processing branches to enable like-for-like comparisons.

3.3.4. Urban Material Spectra

Since unmixing requires previous knowledge about endmembers, a dedicated urban spectral library was compiled within HEATWISE and adapted to be directly usable with CHIME-simulated hyperspectral data sets. Specifically, the starting point was the Existing Urban Hyperspectral Reference Data database [32] which aggregates material spectra from nine publicly accessible libraries (KLUM, ECOSTRESS, MODIS_UCSB, SBUSL, LUMA_SLUM, SLyRUM, UMSL_v1.0, UW_BNL, WaRM).

For Athens, the endmember set was defined through close interaction with the National Observatory of Athens (NOA). NOA provided expertise on local urban materials and access to atmospherically corrected THERMOPOLIS-2009 data, enabling the selection of endmembers that reflect the characteristic Mediterranean built environment. This process produced a legend of 19 aggregated endmembers encompassing asphalt, concrete, white-painted and tiled roofs.

As final step, all identified signatures were resampled to CHIME’s spectral configuration (0.40–2.50 µm, ≈210 bands) to ensure full compatibility with the CHIME-simulated data used in this project. However, because many urban materials display highly similar reflectance and emissivity patterns—particularly when observed under different surface conditions, roughness states or seasons—the preparation of the HEATWISE spectral library followed a strict sequence of steps to ensure internal consistency.

The derivation of representative endmember spectra is a critical step in spectral unmixing, particularly when dealing with heterogeneous spectral libraries characterized by high intra-class variability. Endmember variability has been widely recognized as a major source of uncertainty in linear spectral mixture analysis, motivating the adoption of strategies that are robust to spectral dispersion and outliers [33].

First, a rigorous screening was applied to retain only spectral signatures expressed in reflectance (%). This restriction eliminated mixed units or incompatible measurement formats that could bias subsequent analyses and ensured that all spectra could be directly compared and convolved to CHIME bands without additional conversions. As a result, the usable library was reduced to spectra drawn from three high-quality sources with well-documented measurement protocols: SLUM, ECOSTRESS, and KLUM. These repositories together provide a diverse but internally consistent set of urban material signatures covering asphalt, concrete, roof tiles, metals, and artificial surfaces.

Second, the selected spectra were grouped under common endmember classes. This grouping was guided by the similarity of their spectral behavior across the 400–2500 nm range and by contextual information such as material type, provenance, and surface state. Grouping avoided treating as separate those endmembers that are the same material measured under slightly different conditions (e.g., different seasons, weathering or roughness).

In this study, representative endmember signatures were obtained by computing the median spectrum (band-wise) across all spectra assigned to the same material class. The median aggregation was preferred over the mean in order to reduce the influence of extreme or atypical spectral responses arising from different sensors, acquisition conditions, and material states.

The use of median spectra to summarize spectral variability within an endmember class has precedents in the literature. For example, Cartwright et al. (2023) [34] derive median spectra from mapped spectral endmembers to characterize representative spectral signatures while mitigating the impact of intra-class variability. In line with these studies, the median aggregation adopted here provides a conservative and physically plausible estimate of representative endmember spectra for harmonized multi-source spectral libraries prior to unmixing.

The resulting library underpins the HEATWISE unmixing experiments and ensures full compatibility with CHIME-like datasets, providing a training base for the unmixing algorithms.

4. Experimental Results

By exploiting the existing data sets and the methodologies described in the previous section, it is possible to simulate CHIME and LSTM data, of course in an approximated way because of the differences in spatial and spectral resolution between the legacy data sets and the future sensors. Moreover, it is possible to check which are the options to characterize urban areas by means of the future data sets, for instance with respect to a map of the materials used and their relevance to the UHI effect. To this aim, in the following sections a first characterization of the simulated and CHIME-mimicked and LSTM datasets is provided for the Sepolia area, and then the urban material mapping using CHIME data and LST retrieval using LSTM data are performed and evaluated for both Sepolia and Athens City Center test areas against a set of available ground truth data.

4.1. Simulated and CHIME-Mimicked and LTSM Data Sets for the Test Area of Sepolia (Athens)

In the following paragraphs, an example for each of the simulated and mimicked data sets for both CHIME and LSTM sensors is introduced and visually analyzed.

4.1.1. CHIME-Simulated Data Sets

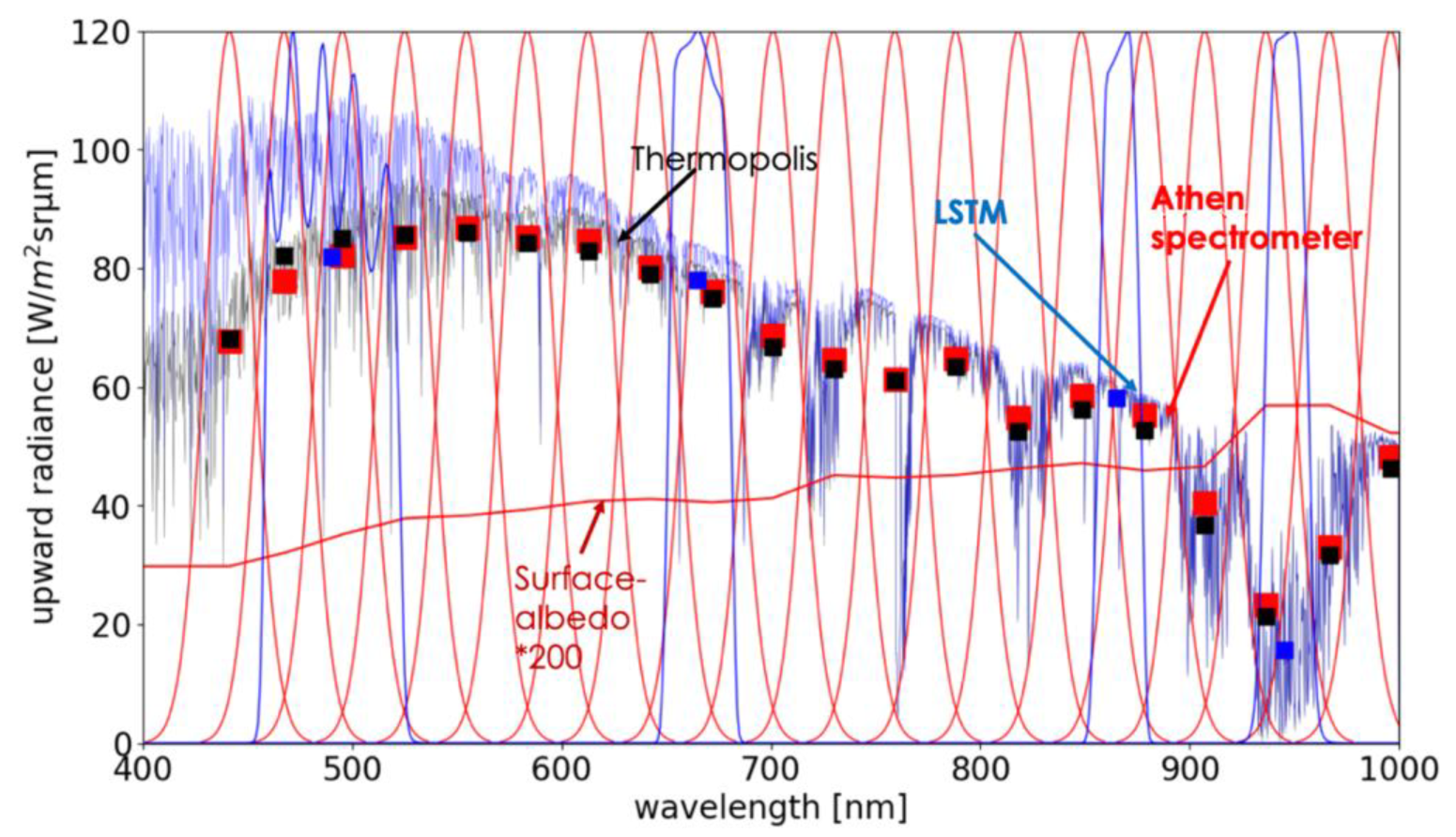

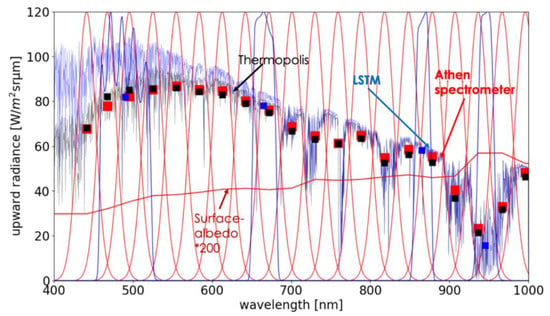

The CHIME-simulated dataset was obtained by means of the previously presented accurate spectral simulation of the BOA radiances and irradiances. Specifically, considering the height of the airborne acquisitions and the atmospheric measurements recorded during the THERMOPOLIS-2009 campaign, the simulations consider measured spectral aerosol optical thickness, the actual water vapor content and estimated spectral surface albedo values. In Figure 4, the simulated hyperspectral upward radiances at 1.6 km height (green) and top of atmosphere TOA (blue) within the spectral range of 400 to 1000 nm are displayed. The measured radiances at 1.6 km (black square) and the simulated Thermopolis radiometer (red square), which is based on given surface albedo (red line), aerosol optical thickness and total column water vapor data, agree well. Simulated LSTM radiances (blue square) as well as the response functions of the AHS spectrometer and LSTM are shown too. This setup for MOMO and the THERMOPOLIS-2009 dataset is used to mimic the full image above Athens.

Figure 4.

Simulated hyperspectral upward radiances at 1.6 km (black) and TOA (blue) for the spectral range of 400 to 1000 nm; the measured radiances at 1.6 km (black square), the simulated Thermopolis radiometer (red square) is based on surface albedo (*200, red line), aerosol optical thickness and total column water vapor data; the simulated LSTM radiance TOA (blue square) as well as the response functions of the channels of the AHS spectrometer (in red) and LSTM (in blue) are displayed.

4.1.2. CHIME-Mimicked Data Sets

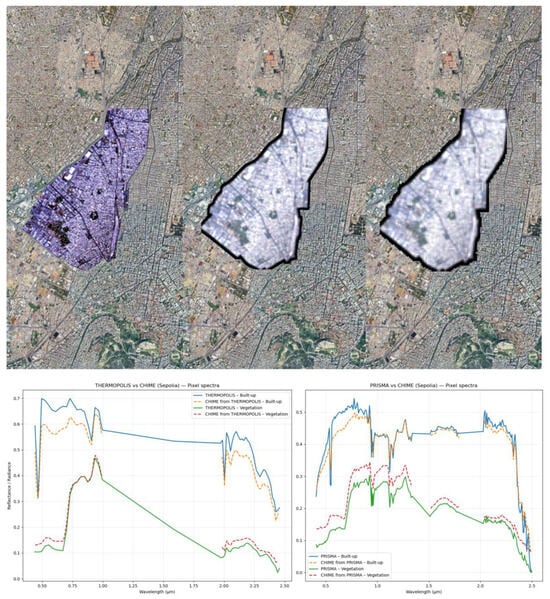

For the mimicked data, the results of the two processing steps’ procedure applied to the original THERMOPOLIS-2009 data set to obtain a CHIME-like data cube are shown in Figure 5, together with the spectral of two points, representative or artificial and natural sources, where the original and the CHIME-like spectra are reported. Since the airborne data set does not contain the whole spectrum of CHIME bands, spectral interpolation has been applied to obtain those values and maintain consistency with the simulated data set, although the values for these bands are not used in the following unmixing procedure.

Figure 5.

Upper row, from left to right: original THERMOPOLIS-2009 false color image with CHIME-mimicked bands but 4 m spatial resolution, the same area after Gaussian filtering, and the final CHIME-like product (filtered and with resampling to 30 m) spatial resolution for the Sepolia neighborhood in Athens. Lower row: THERMOPOLIS-2009 and PRISMA original and CHIME-like spectra for two points, one characterized by artificial urban materials, and one covered by vegetation.

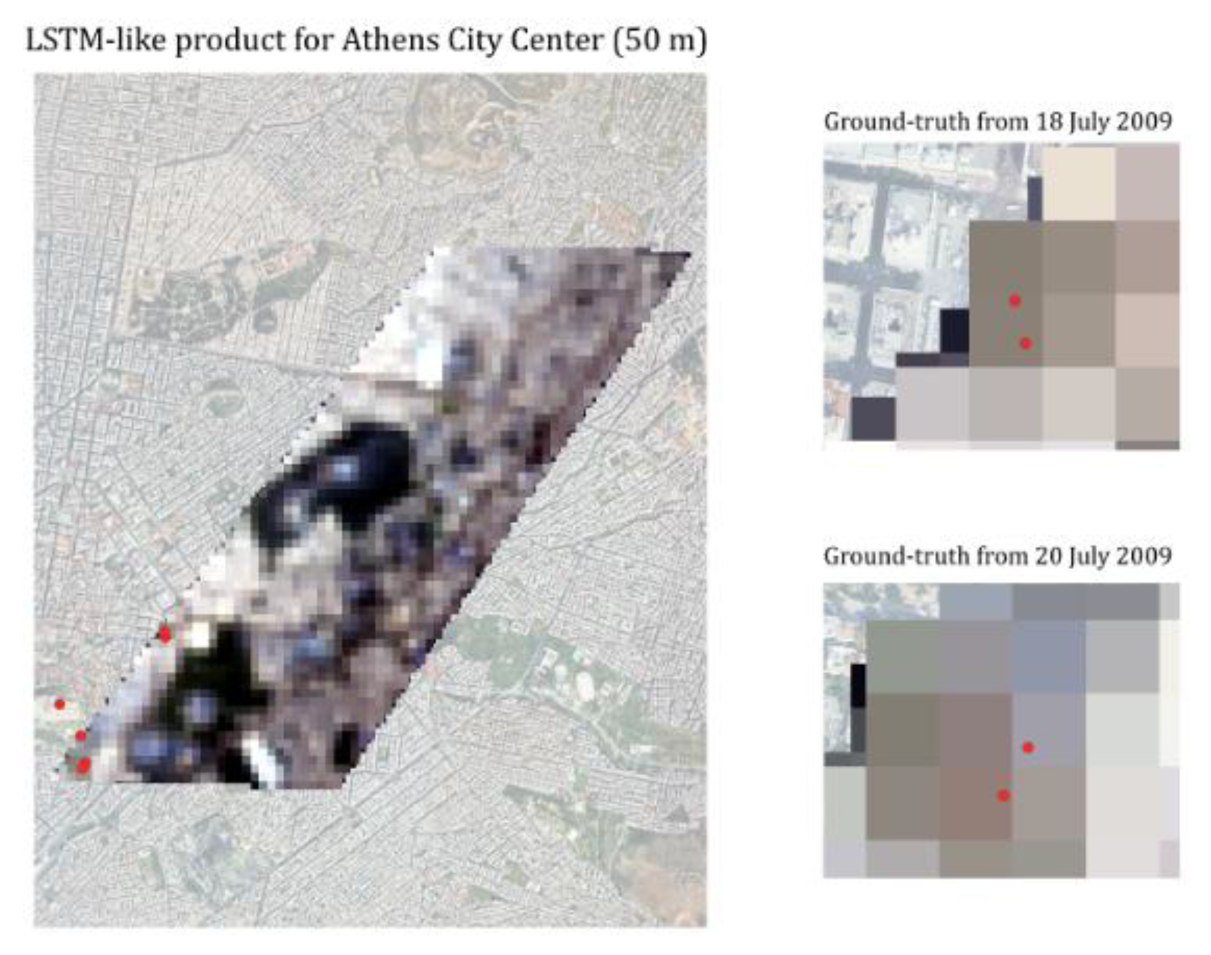

4.1.3. LSTM-Mimicked Data Sets

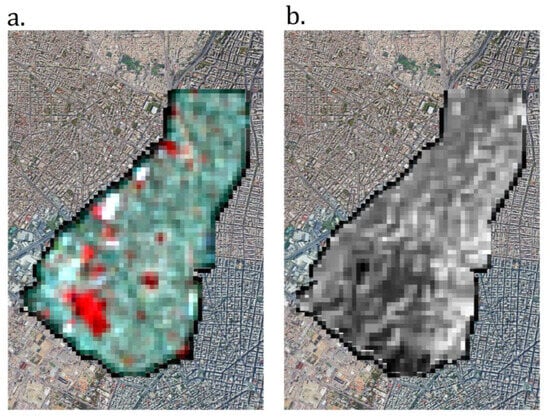

The LSTM-mimicked dataset was obtained using the procedure depicted in Figure 3b by starting from a PRISMA and an ECOSTRESS data set of very close dates, combined to extract the VIS, NIR and TIR bands that are contained in the expected Level 2 product. A visual representation of the area of Sepolia as obtained by combining the NIR, Red, and Green bands is provided in Figure 6a, together with a graphical representation of the LST values in Figure 6b.

Figure 6.

LSTM mimicked data over Sepolia: (a) false color representation using NIR, R, and G bands; (b) gray level representation of the LST values.

4.2. Urban Material Mapping Using CHIME Data

To prove the usefulness of the emulated (both simulated and mimicked) CHIME data sets, the FCLS linear unmixing procedure introduced in Section 3.3.3 was applied to obtain the material abundances in the test areas. Results are first reported with more details for the Sepolia neighborhood, and then, in a summarized version, for the Athens City Center test area.

4.2.1. Urban Material Mapping in the Sepolia Neighborhood Test Area

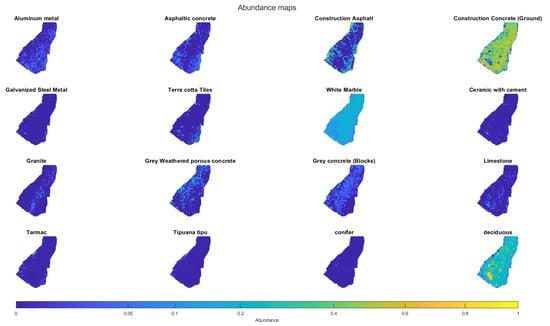

In this area, considering local stakeholders’ opinions, 19 endmembers among those in the overall database were considered. In Sepolia, 17 of them provided non-zero abundances in output to the unmixing approach and were retained for the final assessment. As an example, their abundance maps extracted from the CHIME-mimicked data set extracted from THERMOPOLIS-2009 data are shown in Figure 7. The largest abundance values are obtained for “Construction Concrete”, and “White marble”, and “Deciduous”, which are typical artificial materials used in the urban area of Athens, while locally vegetation classes have large abundances in areas where parks and recreational facilities are located.

Figure 7.

Abundance maps for the Sepolia area extracted from CHIME-mimicked data obtained from the THERMOPOLIS data set. Only maps for endmembers whose maximum abundance in the scene exceeds 1% are shown.

The same unmixing technique, using the same endmember set, has been applied to CHIME-mimicked data obtained from airborne and spaceborne records. Despite their originally very different spatial and spectral resolutions and band coverages, the most abundant materials maps (reported in Figure 8) show a remarkable similarity.

Figure 8.

Visual comparison of the maps of the most abundant material after applying unmixing to CHIME-mimicked data starting from THERMOPOLIS-2009 (left) and PRISMA (right) datasets.

Finally, to quantitatively study the results and test the limitations of the proposed methodology as well as the possibility to use CHIME data for urban material mapping, the most abundant maps for the Sepolia test area have been compared with reference data (Figure 9) that has been selected by creating a 30 × 30 m grid covering the Sepolia region, and manually digitizing the dominant material in selected pixels, using as base maps very high-resolution images from Google Earth and the Greek Cadaster. For the latter, data from 2009 and 2010 were used to ensure that the results are consistent with the THERMOPOLIS-2009 data set. Table 3 summarizes the mapping between the aggregated endmembers and the validation labels used in the Athens case study, providing the basis for assessing the accuracy of the unmixing results.

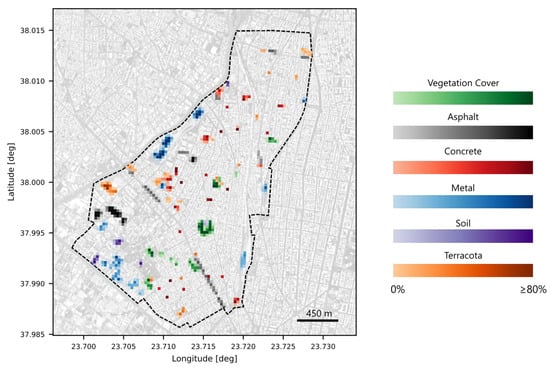

Figure 9.

Spatial distribution of reference data used for validating abundance material maps in the Sepolia neighborhood in Athens, Greece. Colors represent the coverage percentage of each material per pixel.

Table 3.

Correspondence between the aggregated endmembers and the validation labels adopted for the Athens case study. This mapping allows the most abundant materials derived from unmixing to be directly compared with reference polygons.

By comparing the reference points with the maps of the most abundant per-pixel materials, overall accuracy values of 65.9% and 49.4% were obtained for the THERMOPOLIS-2009 and PRISMA-based CHIME-mimicked data, respectively. The omission and commission accuracy for the 5 most frequent classes in the ground truth are reported in Table 4.

Table 4.

Omission and commission errors for the most abundant material for each pixel extracted from Sepolia CHIME-mimicked data, considering urban material database endmembers (i.e., the same endmembers for the two mimicked data sets).

Since these values were not satisfying, a second approach was considered. Specifically, the endmembers were extracted from the images by using the position of pure pixels in the area, and better overall accuracy values for the two data sets, 83% and 75%, respectively, were obtained. The better omission and commission error values for the same classes of Table 4 are reported in Table 5. It is notable that the use of image-extracted endmembers causes a different performance between the two mimicked data sets, due to different data calibration, atmospheric correction, and acquisition geometry, as well as to co-registration errors between the endmember locations extracted from THERMOPOLIS-2009 data and the PRISMA data set.

Table 5.

Omission and commission errors for the most abundant material for each pixel extracted from Sepolia CHIME-mimicked data, considering image-extracted endmembers (i.e., different endmembers for the two mimicked data sets).

As an important comparison step, the same approaches, considering two possible selections for the endmembers and validating the results with the same ground truth, were applied to the CHIME-simulated data sets. The obtained overall accuracy values were 64.9% and 75.3% for the database and image-extracted endmembers, respectively, while the omission and commission errors are reported in Table 6.

Table 6.

Omission and commission errors for the most abundant material for each pixel extracted from the Sepolia CHIME-simulated data set database by considering the database or image-extracted endmembers.

4.2.2. Urban Material Mapping in the Athens City Center Test Area

The same unmixing procedure used for the simulated and CHIME-mimicked data sets in Sepolia was applied to the data sets for the Athens City Center test area. A different set of validation points was extracted in the same way as mentioned earlier for the previous neighborhood. The validation set includes 136 points belonging to the same classes as for Sepolia, except gravel and metal, and with some points belonging to the marble, plastic, water, glass, clay, and bare rock classes. In this test area, the material extraction accuracy values for the THERMOPOLIS-2009-based CHIME-mimicked data range from 47.3% using database endmembers to 81.2% using image-extracted endmembers. Similarly, the accuracy values range from 50.9% to 75.9% under the same circumstances, but starting from the PRISMA CHIME-mimicked data set. The corresponding omissions and commission errors are reported in Table 7 and Table 8.

Table 7.

Omission and commission errors for the most abundant material for each pixel extracted from Athens City Center CHIME-mimicked data, considering urban material database endmembers (i.e., the same endmembers for the two mimicked data sets). The “Nan” value occurs because no validation samples were assigned to this class, so the commission error is undefined.

Table 8.

Omission and commission errors for the most abundant material for each pixel extracted from Athens City Center CHIME-mimicked data, considering image-extracted endmembers (i.e., different endmembers for the two mimicked data sets).

The results show that both THERMOPOLIS-2009- and PRISMA-based CHIME-mimicked data sets can provide reliable enough maps of the most abundant materials in the Athens City Center test area, when using endmembers extracted directly from the image. In this case, the overall accuracy reported above significantly increases, with a clear reduction of both omission and commission errors across most classes. This confirms that scene-specific endmember libraries are preferable for urban material mapping and supports the use of synthetic CHIME products for the characterization of urban fabrics in view of the future mission.

The same results show, however, that there is a need to collect training points on the ground and to know in advance which are the materials of interest for a specific area (for instance, the materials in Sepolia and Athens City Centre, which are two neighboring districts, differ substantially as a function of land use). These are two significant challenges that define the current main limitation to the use of urban material mapping of 30 m spatial resolution CHIME hyperspectral data sets. Moreover, the differences among the results using CHIME mimicked data sets obtained from data by different sensors highlight the crucial role of atmospheric correction to maintain data similarity with respect to the spectra of the materials on the ground. Similarly, an important role is played by geometric correction because a spatial resolution of 30 m is quite coarse in urban areas, and registration error of fractions of a pixel may still prevent the correct selection of its location and train for (or validate the presence of) a specific material.

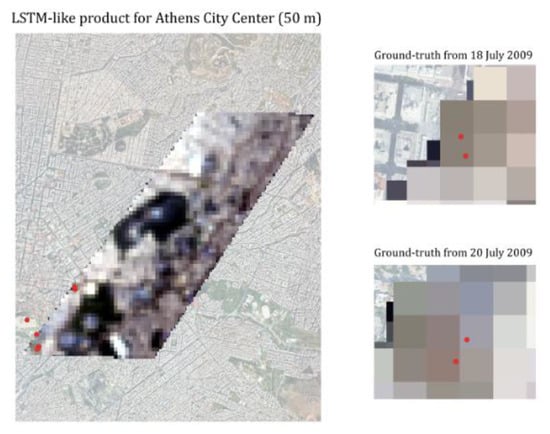

4.3. Land Surface Temperature Mapping Using LSTM Data

As an additional quality check, we compared the 50 m LSTM-mimicked LST with ground-truth measurements collected during the THERMOPOLIS-2009 campaign in Athens City Center. Figure 10 shows the location of the AHS validation sites and the temporal sequence of the values recorded on the ground, superimposed on the values extracted from the LSTM-mimicked image in the same 50 × 50 m pixels. Given the very limited number of points, the results cannot be considered a validation exercise. This comparison serves instead as a consistency check of the processing workflow used to generate the mimicked data. The results show adequate agreement between the mimicked and ground-truth LST (r = 0.65, r2 ≈ 0.43, N = 4), suggesting that the processing workflow of Figure 3b performed as intended. It is important to note that the employed ground-truth measurements were collected at sites that can be assumed homogeneous and isothermal at the 4 m spatial scale of the original AHS data, but not at the coarse 50 m scale of the mimicked data; this heavily impacts the comparison and explains the statistics reported here. A real and comprehensive validation of the THERMOPOLIS-2009 AHS LST used for generating the LSTM-mimicked data was provided in [24], based on a larger validation set including measurements collected outside our pilot areas.

Figure 10.

The location of the LST measuring station in Athens City Center and the locations of the sequence of LST values acquired on the ground (red dots).

5. Discussion

The first point to stress from the presented results is the strong similarity between the results obtained using the CHIME-mimicked and CHIME-simulated data sets in the Sepolia area. The main outcome of this first test is therefore that the simpler mimicking approach may be used instead of the more complex and time-consuming simulating technique for urban material mapping. It is very likely that in other applications for the same data sets, where single spectral features are crucial, the simulated data may perform better. However, when performing unmixing to detect urban materials’ abundance, since the whole spectrum is exploited, the minor differences between the simulated and the mimicked data sets do not play a major role.

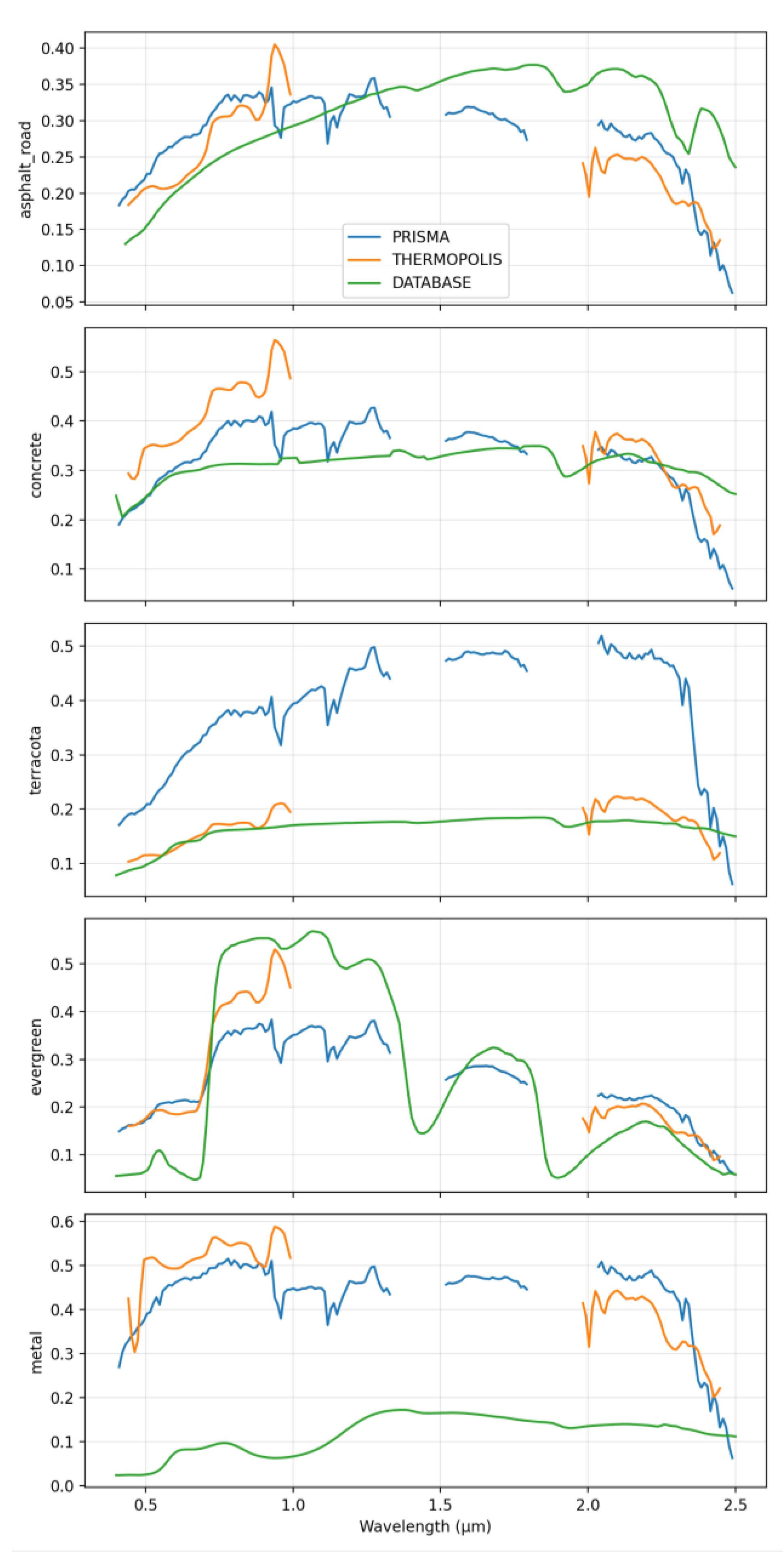

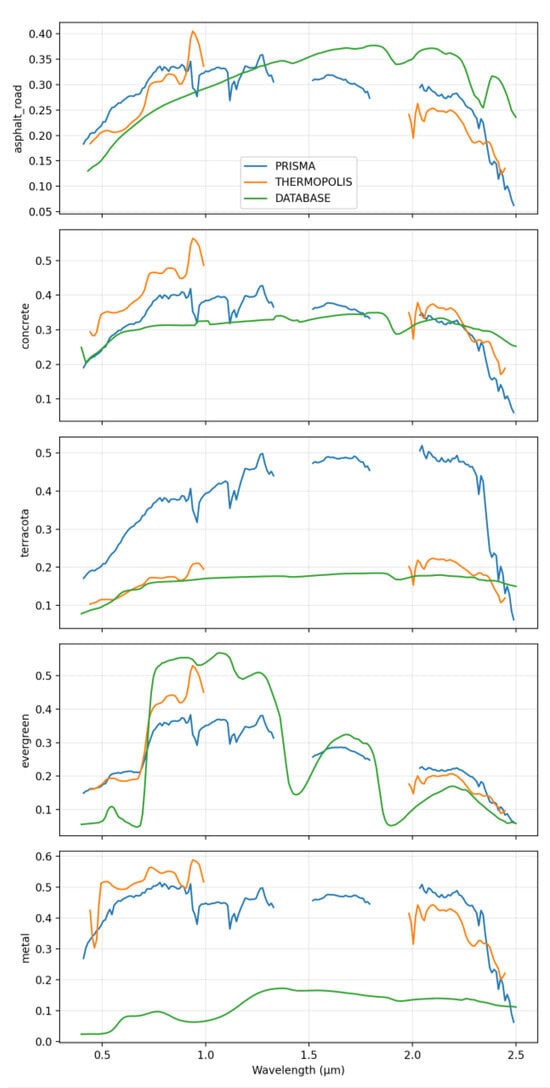

Moreover, the results on Sepolia show two important points that relate to the calibration of the data sets used to obtain the mimicked data and the quality of the urban material spectra in existing databases. Indeed, when using the endmembers from the homogenized urban database, the accuracy values are quite low, which is justified by a comparison of the database spectra and those obtained from the mimicked data sets for points with a high (>70%) abundance of the same materials (Figure 9). The differences are twofold: on the one hand, there are materials (e.g., metal) whose spectra are very different in the database and in the data, showing that there may not be enough information in the database to deal with the inherently extreme variability of urban material (and their spectra). On the other hand, even in the case of similar materials (e.g., asphalt), the better calibration of the dedicated THERMOPOLIS-2009 airborne campaign processing chain with respect to the PRISMA results in a better match and more accurate results (see Figure 11).

Figure 11.

A comparison among endmember spectra obtained from the urban material database (in green) and extracted from CHIME-mimicked data obtained from THERMOPOLIS-2009 (orange) and PRISMA (blue) data sets in the test areas of Athens, Greece.

It should also be mentioned that endmember variability theory, scale effects, and material aging must be considered as other very likely drivers of the difference between results using endmember database spectra as opposed to image-driven ones. Approaches such as [35] would be evaluated in the future to reduce dependency on these factors.

The final comment about urban material extraction comes from the comparison of the results in the two different test sites in Athens: Sepolia and the City Center. The overall behavior is remarkably consistent across the two neighborhoods: in both cases, CHIME-mimicked data derived from either THERMOPOLIS-2009 or PRISMA allow one to retrieve urban material fractions with comparable accuracy, provided that scene-specific endmembers are used. Some differences in omission and commission errors among individual classes are observed between the two sites, but the general performance levels and the relative improvements obtained when switching from database to image-extracted endmembers are very similar. This confirms that the proposed approach can be robustly applied to different types of urban environments, in view of future CHIME acquisitions.

As a final note, it is true that, according to our tests, there is no need for fully simulated data sets for mapping the most urban material, but we need to note that it may be completely different for other applications, such as water quality mapping, and, more in general, in the case of biophysical quantity extractions that require very accurate information about one or more specific wavelengths.

6. Conclusions

The aim of this work was to provide a tailored simulated data set for the CHIME and LSTM sensors that could be useful to test environmental applications in urban areas. By introducing two different methodologies, a significant data set over Athens has been completed. Using these data set maps of urban materials, and LST temporal sequences were obtained on their locations, showing that the use of CHIME and LSTM can provide relevant information for the study of urban material and SUHI effects, with the more general aim to provide the stakeholders with novel tools to select options to improve urban resilience to climate change and monitor their effects in time.

Indeed, the reported results show that CHIME-mimicked products generated from both airborne THERMOPOLIS-2009 and spaceborne PRISMA data can achieve material fraction accuracies comparable to those obtained from fully simulated CHIME data, especially when scene-specific endmembers are used. At the same time, the LSTM-mimicked products, despite a bias in absolute LST, are useful to reproduce relative spatial and temporal temperature patterns at 50 m resolution, which are in turn essential for analyzing intra-urban heat contrasts. Overall, these findings confirm that the proposed synthetic CHIME and LSTM data sets are good enough proxies for the forthcoming missions and can already be exploited to preliminarily design and test workflows for urban material characterization and UHI assessments.

It is true, however, that there are remaining uncertainties mostly related to the calibration of spaceborne data and the selection of the endmembers for the materials to be extracted in any specific location. Future research could address these challenges by designing an image-driven endmember selection method based on spectral similarity with existing urban material spectra and applying sparse unmixing techniques [35] to strengthen the applicability of CHIME and LSTM data in urban studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.G., L.G.L., A.S., I.K. and P.S.; methodology, P.G., L.G.L., A.S., I.K., J.F. and P.S.; software, L.G.L., A.S., J.F. and P.S.; validation, L.G.L. and P.S.; formal analysis, P.G., L.G.L., A.S., I.K. and P.S.; investigation, P.G., L.G.L., A.S., I.K. and P.S.; resources, P.G., C.T.K. and I.K.; data curation, L.G.L., A.S. and P.S.; writing—original draft preparation, P.G., L.G.L., A.S., J.F. and P.S.; writing—review and editing, P.G., L.G.L., A.S., I.K., C.T.K., J.F. and P.S.; visualization, L.G.L. and P.S.; supervision, P.G.; funding acquisition, P.G. and I.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by ESA, grant number 4000145882/24/I-DT-bgh.

Data Availability Statement

The CHIME-mimicked and CHIME-simulated data sets, as well as the LSTM-mimicked data sets, for the two test sites in Athens will be made available at the APEx PRR (Project Results Repository).

Conflicts of Interest

Author Jürgen Fischer is employed by the company Spectral Earth GmbH. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 6S | Second Simulation of a Satellite Signal in the Solar Spectrum |

| AHS | Airborne Hyperspectral Scanner |

| BOA | Bottom-of-Atmosphere |

| CHIME | Copernicus Hyperspectral Imaging Mission for the Environment |

| ECOSTRESS | Ecosystem Spaceborne Thermal Radiometer Experiment on Space Station |

| ESA | European Space Agency |

| FWHM | Full-Width-Half-Maximum |

| HEATWISE | High-resolution Enhanced Analysis Tool for Urban Hyperspectral and Infrared Satellite Evaluation |

| GSD | Ground Sampling Distance |

| LCZ | Local Climate Zones |

| LST | Land Surface Temperature |

| LSTM | Land Surface Temperature Monitoring |

| LSTR | Land Surface Temperature Radiometer |

| MOMO | Matrix-Operator Model |

| MRD | Mission Requirements Document |

| PRISMA | PRecursore IperSpettrale della Missione Applicativa |

| RMSE | Root-Mean-Square-Error |

| SUP | Sentinel Users Preparation |

| UHI | Urban Heat Island |

| VNIR | Visible and Near-Infrared |

| VSWIR | Visible, Near- and Shortwave Infrared Radiation |

References

- United Nations. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Oke, T.R.; Mills, G.; Christen, A.; Voogt, J.A. Urban Climates, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seto, K.C.; Fragkias, M.; Güneralp, B.; Reilly, M.K. A Meta-Analysis of Global Urban Land Expansion. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamouris, M. On the energy impact of urban heat island and global warming on buildings. Energy Build. 2014, 82, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimmond, S. Urbanization and global environmental change: Local effects of urban warming. Geogr. J. 2007, 173, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, A.; GBD 2021 Europe Life Expectancy Collaborators. Changing life expectancy in European countries 1990–2021: A subanalysis of causes and risk factors from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Public Health 2025, 10, e172–e188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Founda, D.; Giannakopoulos, C. The exceptionally hot summer of 2007 in Athens, Greece—A typical summer in the future climate? Glob. Planet. Change 2009, 67, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luqman, M.; Rayner, P.J.; Gurney, K.R. On the impact of urbanisation on CO2 emissions. Npj Urban Sustain. 2023, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Dawson, R.J.; Ürge-Vorsatz, D.; Delgado, G.C.; Barau, A.S.; Dhakal, S.; Dodman, D.; Leonardsen, L.; Masson-Delmotte, V.; Roberts, D.C.; et al. Six research priorities for cities and climate change. Nature 2018, 555, 23–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ching, J.; Mills, G.; Bechtel, B.; See, L.; Feddema, J.; Wang, X.; Ren, C.; Brousse, O.; Martilli, A.; Neophytou, M.; et al. WUDAPT: An Urban Weather, Climate, and Environmental Modeling Infrastructure for the Anthropocene. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2018, 99, 1907–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallotti, R.; Sacco, P.; De Domenico, M. Complex Urban Systems: Challenges and Integrated Solutions for the Sustainability and Resilience of Cities. Complexity 2021, 2021, 1782354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysoulakis, N.; Grimmond, S.; Feigenwinter, C.; Lindberg, F.; Gastellu-Etchegorry, J.-P.; Marconcini, M.; Mitraka, Z.; Stagakis, S.; Crawford, B.; Olofson, F.; et al. Urban energy exchanges monitoring from space. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X. Make the upcoming IPCC Cities Special Report count. Science 2023, 382, eadl1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sismanidis, P.; Bechtel, B.; Perry, M.; Ghent, D. The Seasonality of Surface Urban Heat Islands across Climates. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taubenböck, H.; Weigand, M.; Esch, T.; Staab, J.; Wurm, M.; Mast, J.; Dech, S. A new ranking of the world’s largest cities—Do administrative units obscure morphological realities? Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 232, 111353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demuzere, M.; Bechtel, B.; Middel, A.; Mills, G. Mapping Europe into local climate zones. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Space Agency. LSTM—Land Surface Temperature Monitoring Mission. Copernicus SentiWiki. Available online: https://sentiwiki.copernicus.eu/web/lstm (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Nieke, J.; Despoisse, L.; Gabriele, A.; Weber, H.; Strese, H.; Ghasemi, N.; Gascon, F.; Alonso, K.; Boccia, V.; Tsonevska, B.; et al. The copernicus hyperspectral imaging mission for the environment (CHIME): An overview of its mission, system and planning status. In Sensors, Systems, and Next-Generation Satellites XXVII; Society of Photographic Instrumentation Engineers: Seattle, WA, USA, 2023; pp. 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, I.D.; Oke, T.R. Local Climate Zones for Urban Temperature Studies. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 2012, 93, 1879–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doppler, L.; Carbajal-Henken, C.; Pelon, J.; Ravetta, F.; Fischer, J. Extension of radiative transfer code MOMO, matrix-operator model to the thermal infrared—Clear air validation by comparison to RTTOV and application to CALIPSO-IIR. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2014, 144, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koetz, B.; Baschek, B.; Bastiaanssen, W.; Berger, M.; Blommaert, J.; Alamanac, A.B.; Barat, I.; Buongiorno, M.F.; D’Andrimont, F.; Del Bello, U.; et al. Copernicus High Spatio-Temporal Resolution Land Surface Temperature Mission: Mission Requirements Document (MRD); Mission Requirements Document (MRD) ESA-EOPSM-HSTR-MRD-3276; European Space Agency (ESA): Noordwijk, The Netherlands, 2021; Available online: https://sentiwiki.copernicus.eu/__attachments/1678167/ESA-EOPSM-HSTR-MRD-3276%20-%20Copernicus%20High%20Spatio-Temporal%20Resolution%20Land%20Surface%20Temperature%20Mission%202021%20-%203.0.pdf?inst-v=1c525dd3-ec3a-461c-8cf3-b856170221ed (accessed on 21 January 2026).

- Keramitsoglou, I.; Sismanidis, P.; Analitis, A.; Butler, T.; Founda, D.; Giannakopoulos, C.; Giannatou, E.; Karali, A.; Katsouyanni, K.; Kendrovski, V.; et al. Urban thermal risk reduction: Developing and implementing spatially explicit services for resilient cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 34, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Founda, D.; Santamouris, M. Synergies between Urban Heat Island and Heat Waves in Athens (Greece), during an extremely hot summer (2012). Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- THERMOPOLIS 2009 Campaign—Final Report. 2010. Available online: https://earth.esa.int/eogateway/documents/20142/37627/THERMOPOLIS-2009-Final%20Report.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- THERMOPOLIS—Earth Online. Available online: https://earth.esa.int/eogateway/campaigns/thermopolis (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Hollstein, A.; Fischer, J. Radiative transfer solutions for coupled atmosphere ocean systems using the matrix operator technique. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2012, 113, 536–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshava, N.; Mustard, J.F. Spectral Unmixing. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2002, 19, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasti, B.; Zouaoui, A.; Mairal, J.; Chanussot, J. Image Processing and Machine Learning for Hyperspectral Unmixing: An Overview and the HySUPP Python Package. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.09375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HySUPP—HyperSpectral Unmixing Python Package (Open-Source Toolbox). Available online: https://github.com/inria-thoth/HySUPP (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Heinz, D.C.; Chang, C.-I. Fully Constrained Least Squares Linear Spectral Mixture Analysis Method for Material Quantification in Hyperspectral Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2001, 39, 529–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasti, B.; Koirala, B.; Scheunders, P.; Ghamisi, P. UnDIP: Hyperspectral Unmixing Using Deep Image Prior. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote. Sens. 2022, 60, 5500115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salcido, J.; Laefer, D. Existing Urban Hyperspectral Reference Data. Zenodo 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somers, B.; Asner, G.P.; Tits, L.; Coppin, P. Endmember variability in spectral mixture analysis: A review. Remote Sens. Environ. 2011, 115, 1603–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, S.F.A.; Calvin, W.M.; Seelos, F.P.; Seelos, K.D. Spatial and temporal variation of Mars south polar ice composition from spectral endmember classification of CRISM mapping data. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2023, 128, e2023JE008044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasti, B.; Zouaoui, A.; Mairal, J.; Chanussot, J. SUnAA: Sparse Unmixing Using Archetypal Analysis. IEEE Geosci. Remote. Sens. Lett. 2023, 20, 5505505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.