Highlights

What are the main findings?

- A high-quality dataset was initially constructed and WaveEdgeNet was proposed.

- A novel feature selection framework is proposed in this study.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- We introduced the variables representing the distance to different land use types.

- Investigated the influence of various environmental factors on Mikania micrantha.

Abstract

Mikania micrantha is one of the most detrimental invasive plant species in the southeastern coastal region of China. To accurately predict the invasion pattern of Mikania micrantha and offer guidance for production practices, it is essential to determine its precise location and the driving factors. Therefore, a design of the wavelet convolution and dynamic feature fusion module was studied, and WaveEdgeNet was proposed. This model has the abilities to deeply extract image semantic features, retain features, perform multi-scale segmentation, and conduct fusion. Moreover, to quantify the impact of human and natural factors, we developed a novel proximity factor based on land use data. Additionally, a new feature selection framework was applied to identify driving factors by analyzing the relationships between environmental variables and Mikania micrantha. Finally, the MaxEnt model was utilized to forecast its potential future habitats. The results demonstrate that WaveEdgeNet effectively extracts image features and improves model performance, attaining an MIoU of 85% and an overall accuracy of 98.62%, outperforming existing models. Spatial analysis shows that the invaded area in 2024 was smaller than that in 2023, indicating that human intervention measures have achieved some success. Furthermore, the feature selection framework not only enhances MaxEnt’s accuracy but also cuts down computational time by 82.61%. According to MaxEnt modeling, human disturbance, proximity to forests, distance from roads, and elevation are recognized as the primary factors. In the future, we will concentrate on overcoming the seasonal limitations and attaining the objective of predicting the growth and reproduction of kudzu before they happen, which can offer a foundation for manual intervention. This study lays a solid technical foundation and offers comprehensive data support for comprehending the species’ dispersal patterns and driving factors and for guiding environmental conservation.

1. Introduction

The invasion of alien species represents one of the most severe threats to ecosystem integrity and functionality [1]. Mikania micrantha, a vine species within the genus Mikania of the Asteraceae family and native to Central and South America, demonstrates remarkable adaptability and reproductive capacity. It has been identified by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as one of the world’s 100 most invasive alien species. Mikania micrantha has extensively invaded China, with its distribution primarily concentrated in provinces such as Guangdong, Guangxi, Yunnan, and Hainan [2]. It is currently recognized as one of the most detrimental invasive plant species in South China. In the Pearl River Delta region of China alone, the annual ecological and economic losses caused by the overspread of Mikania micrantha are nearly CNY 1 billion [3]. Therefore, implementing effective prevention and control measures against these species is imperative. The foundation for achieving targeted prevention and control lies in the accurate detection and comprehensive understanding of its spatial distribution patterns.

Traditional methods for monitoring invasive plants, such as on-site surveys, are inefficient and have a limited coverage area. With the advancement of remote sensing technology, a more efficient and scalable approach has emerged for the identification and long-term monitoring of invasive plants. Over the past few decades, satellite-based and aerial remote sensing techniques have become indispensable tools in this field [4]. Notable progress has been made through the integration of multi-source satellite imagery—such as Landsat, MODIS, and Sentinel—enabling enhanced monitoring capabilities [5]. For example, Dai et al. employed Landsat 8 imagery to map Mikania micrantha beneath forest canopies in Chitwan National Park, Nepal. Kandwal et al. applied Landsat 8 data to identify and delineate Lantana camara patches using various spectral indices, achieving high classification accuracy [6,7]. However, for climbing or vine-like species such as Mikania micrantha, medium-resolution satellite imagery often lacks the spatial detail necessary for accurate monitoring. Although high-resolution satellite imagery provides better spatial resolution, its application is limited by high acquisition costs and complex data processing requirements, which hinder its feasibility for large-scale implementation. Under these constraints, drone-based remote sensing presents a cost-effective and efficient alternative, offering relatively high spatial resolution while maintaining scalability [8]. Compared to conventional manual surveying methods, drones can access remote or otherwise inaccessible areas, thereby enabling more comprehensive and detailed ecological monitoring.

Large-scale automated identification of invasive plant species plays a critical role in the effective mapping and management of such flora. Historically, various traditional remote sensing techniques, such as pixel-based classification, object-based image analysis, rule-based systems, and maximum likelihood classification, have been applied to identify and map invasive plants. With recent advances in computational methods, machine learning algorithms have increasingly been adopted in this domain, yielding significant improvements [9]. These algorithms enable accurate plant classification by analyzing diverse data sources, including spectral reflectance, textural features, environmental variables, and vegetation phenological traits. However, when applied to large-scale, unstructured image datasets, conventional machine learning approaches often encounter limitations in terms of processing efficiency and classification accuracy. Recently, deep learning techniques, leveraging their strong capabilities in modeling complex nonlinear relationships, have achieved notable success in the monitoring and detection of invasive plant species [10].

Recently, the methods for drone image segmentation predominantly concentrate on two architectures: convolutional neural networks (CNN) and visual Transformer (ViT). CNN, boasting efficient local feature extraction capabilities, has emerged as the fundamental framework for drone image segmentation. Encoder–decoder structures, such as U-Net, have been extensively utilized in pixel-level segmentation [11]. However, CNN encounters certain limitations when handling global context dependencies in images [12]. In contrast, Transformer, leveraging the self-attention mechanism, can effectively capture long-range global information and has exhibited remarkable performance in benchmark tests on remote sensing datasets like iSAID [12]. Nevertheless, Transformer suffers from the problem of high computational cost and depends on a large quantity of labeled data. To strike a balance between accuracy and efficiency, the current research trend is to construct hybrid architectures, for example, integrating a global–local attention module into the CNN encoder, thus combining the advantages of both [11]. Cruz et al. developed a U-Net architecture utilizing Inception-v3 as the backbone model, incorporating UAV-acquired data to monitor Spartina [13]. Wang QF et al. proposed the DeepSolanum-Net framework based on UAV-collected images to monitor the invasive weed Solanum rostratum Dunal, achieving a pixel accuracy of 89.95% [14]. Ollachica applied the U-Net architecture in conjunction with drone-captured imagery to accurately extract Eichhornia crassipes, attaining an impressive accuracy rate of 96% [15]. Therefore, the integration of deep learning algorithms with UAV images demonstrates considerable potential in the field of invasive plant identification. A key challenge involves accurately distinguishing Mikania micrantha from surrounding vegetation, particularly due to its vine-like growth pattern. In deep learning tasks, especially semantic segmentation, convolutional and pooling operations often lead to the loss of high-frequency information. As network depth increases, contour details may gradually become blurred and eventually disappear. Therefore, maintaining image fidelity while extracting high-level semantic features remains a critical challenge in semantic segmentation.

Additionally, predicting the spread range of invasive plants can provide a scientific basis for management departments to formulate protection and control strategies. Therefore, identifying the main driving factors for the spread of invasive plants is a crucial component of such research. Environmental factors are typically regarded as key drivers that facilitate the expansion of invasive plants into new areas, and numerous studies have documented this phenomenon [16]. For instance, Visztra GV et al. performed a comprehensive analysis of the driving forces behind the spread of three invasive plant species. Their findings indicated that the distribution of these invasive plants is significantly associated with factors such as soil properties, fluctuations in water temperature, and climatic conditions [17]. In recent years, scholars have found that land use types significantly influence ecosystem dynamics and species distributions [18]. However, the specific impact of land use patterns on Mikania micrantha remains insufficiently explored. This study aims to systematically investigate how different land use types affect the distribution and growth of Mikania micrantha by utilizing detailed land use data.

Predicting the potential geographic distribution of invasive species is crucial for assessing their risks to ecosystems and economies. The Maximum Entropy Model (MaxEnt) is widely used to predict the occurrence probability of invasive plants using limited data, and has been proven to be effective and reliable in many studies [19,20,21]. Dakhil MA et al. utilized the maximum entropy model to simulate species distribution and carried out an in-depth analysis of the driving forces behind the invasion of the Prosopis juliflora plant. Their findings indicate that soil pH, soil clay content, and environmental humidity are the primary factors influencing the invasion risk of Prosopis juliflora [22]. Therefore, this study employs MaxEnt to predict the potential geographic distribution of Mikania micrantha in Shenzhen City.

The work content of this study is as follows:

(1) A high-quality dataset for semantic segmentation of Mikania micrantha was initially constructed. Subsequently, a novel Wavelet-Convolution Edge-Refined Segmentation Network (WaveEdgeNet) was proposed. The WaveEdgeNet comprises three key modules: the Wavelet Context Block (WCB), the Dual-level Feature Fusion module (DCF), and the Edge Refinement Subnetwork (ERS). Based on this model, spatial distribution predictions for Mikania micrantha in Shenzhen were generated for the years 2023 and 2024, revealing its expansion trends during this period.

(2) A novel feature selection framework is proposed in this study. By integrating point-biserial correlation, Pearson correlation analysis, and variance inflation factor assessment, environmental variables are systematically screened in conjunction with different environmental variables, leading to the identification of the optimal feature set. This approach effectively reduces the computational burden of the model while maintaining its predictive accuracy.

(3) During the selection of environmental variables, in addition to incorporating climatic and topographic factors such as temperature and slope, we innovatively introduced the variables representing the distance to different land use types. This enhancement allows for a more precise quantification of the dynamic impact of human activities on the invasion process of Mikania micrantha. By reflecting the gradient of anthropogenic disturbance, this variable contributes to a better understanding of the species’ spatial dispersal patterns across ecotones.

(4) This study investigated the influence of various environmental factors on Mikania micrantha, including its probability distribution patterns, the underlying causes of its occurrence, and the likelihood of its future spread. The results offer a scientific foundation for the prevention and management of this invasive species.

2. Study Area and Data

2.1. Research Framework

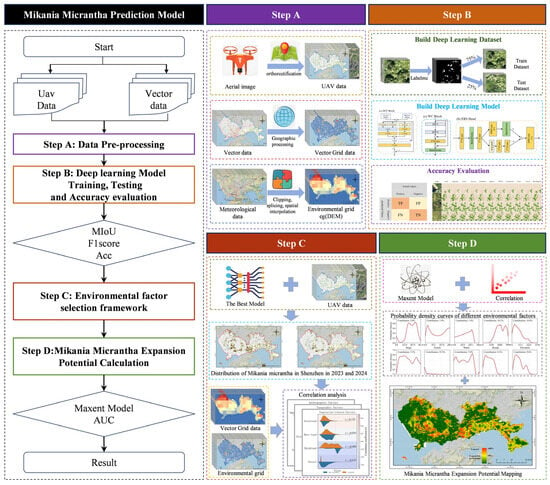

To investigate the spread trends of Mikania micrantha, the proposed WaveEdgeNet models were constructed to detect the species using UAV-based imagery collected over a two-year period. Subsequently, MaxEnt models were employed to predict its potential spread patterns. The overall framework of this study is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Technical roadmap for research.

Data collection and preprocessing (Step 1): Preprocess the data and construct a deep learning dataset. Deep learning Model (Step 2): Build the WaveEdgeNet model and configure parameters, use the dataset to train and test this model, and predict the distribution of licorice vine in Shenzhen in 2023 and 2024. Environmental factor selection framework (Step 3): Develop a new feature selection framework to screen 17 environmental factors. Mikania micrantha Expansion Potential Calculation (Step 4): Use the MaxEnt model to simulate the licorice vine spread potential and obtain the probability density curves of each screened environmental factor.

2.2. Study Area

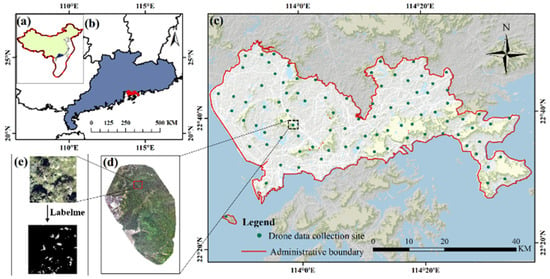

Shenzhen City is situated in the coastal region of southern China, on the eastern shore of the Pearl River Estuary (Figure 2). Situated within the low mountain and hilly terrain of southern China, the city spans a total area of approximately 1997.47 square kilometers, with an average elevation of around 70 m. Geographically, Shenzhen is positioned at the mouth of the Pearl River. The city experiences a subtropical monsoon climate, with an average annual temperature of approximately 23.3 °C and average annual sunshine hours totaling about 1853 h. The region receives abundant rainfall, averaging approximately 1932.9 mm annually. Shenzhen is significantly impacted by Mikania micrantha, with over 2700 hectares affected. In ecologically sensitive areas such as Wutong Mountain, Xianhu Botanical Garden, and near Shenzhen Reservoir, the incidence of damage reaches up to 60%.

Figure 2.

Location map of the study area. (a) Map of China (b) Geographical location of Shenzhen City in Guangdong Province (c) Map of Shenzhen City, the green dots represent the sampling points of the unmanned aerial vehicle (d) Unmanned aerial vehicle data after orthorectification (e) Annotation process of the deep learning dataset.

2.3. Data Collection and Preprocessing

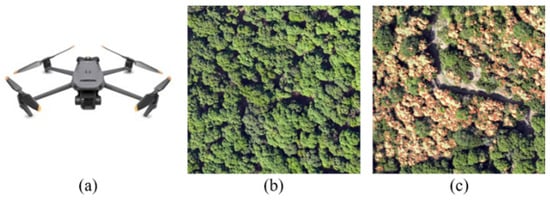

Recently, UAV-based data have shown considerable potential for forest disease identification and disaster observation, primarily due to their high resolution and precision [23]. Consequently, UAV-based data collection was performed in areas potentially harboring Mikania micrantha, encompassing reservoirs, forests, and parks in this study (Figure 3). To optimize data collection for areas infested with Mikania micrantha and other forested regions, it is advisable to conduct sampling during the flowering period of Mikania micrantha, which is the most easily monitored phase for this species. Typically, the flowering period of Mikania micrantha occurs in November. Therefore, our sampling periods were scheduled from October to December 2023 and again from October to December 2024. The drone model employed in this study was the DJI Mavic 3E, which offers a resolution of approximately 0.1 m. During data collection, the flight altitude was set at 180 m above ground level. Data collection times were arranged around 9 a.m. and 4 p.m. to minimize the impact of lighting conditions on the quality of the drone-captured images. Finally, a total of 513 flight routes were conducted in 2023 and 2024, covering an area of 309.18 km2, with 28,582 drone-captured images collected in total.

Figure 3.

(a) Pictures of drones. (b) The uninvaded forest (c). The invaded forest (the red part shows the blooming of Mikania micrantha).

Then, the ENVI5.3 and ArcMap10.8 software packages were utilized to preprocess the data, thereby mitigating deviations caused by both sensor and atmospheric effects. Data preprocessing involves identifying tie points, performing geometric correction and orthorectification, applying radiometric correction, reducing noise, mosaicking, and cropping as required. Subsequently, labeled images were generated using Labelme (Form The Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology) for annotating the data and constructing an image segmentation dataset to train multiple models and evaluate their accuracy. A total of 2018 training samples were collected through annotation, and data augmentation operations such as horizontal or vertical flipping, rotation, random scaling, random cropping, color and luminance transformation were performed on these training samples. Eventually, a total of 16,543 training samples were obtained, with each sample having a resolution of 512 × 512 pixels. Specifically, 75% of the samples were used for training, while 25% of the samples were used for validation and prediction. In addition, to explore the driving factors of Mikania micrantha, we also obtained some data as follows: digital elevation model (DEM) data with a spatial resolution of 30 m and MODIS product data (e.g., vegetation index data such as LAI and NDVI) were obtained from Google Earth Engine (GEE, https://developers.google.com) (accessed on 11 July 2025). The road vector data for Shenzhen were acquired from OpenStreetMap (OSM, https://openstreetmap.org/) (accessed on 11 July 2025), while the annual land cover data of China at a 30 m resolution were sourced from the National Cryosphere Desert Data Center (https://www.ncdc.ac.cn/) (accessed on 11 July 2025), including water bodies, impervious surfaces, etc.

2.4. Identification Algorithm of Mikania micrantha

2.4.1. Structure of WaveEdgeNet

In recent years, various deep learning models have demonstrated exceptional performance in image segmentation tasks. U-Net employs an encoder–decoder architecture with skip connections to effectively integrate multi-scale features [24]. UNet++ enhances feature reuse through nested dense skip connections, although this approach significantly increases computational complexity [25]. Transformer-based variants leverage self-attention mechanisms to overcome the limitations of local receptive fields [26]. Although these algorithms have achieved promising results, they still exhibit certain limitations, which can be summarized in two aspects. First, during the feature extraction phase, the constraint imposed by the local receptive field on the convolution kernel limits its ability to effectively capture multi-scale high-frequency information in images. Second, in the feature fusion stage, the significant disparities in receptive fields between shallow and deep features result in mismatches in encoded semantic-level information, thereby constraining the overall effectiveness of feature fusion.

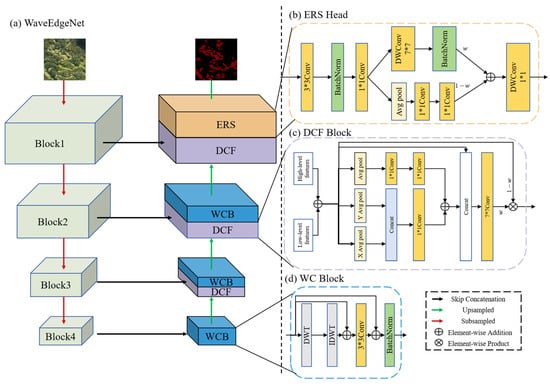

To address the problems, we propose Wavelet-Convolution Edge-Refined Segmentation Network (WaveEdgeNet), a model structurally like Unetformer and consisting of a backbone and four distinct stages (Figure 4). The model realizes its core functionalities through a modular design with hierarchical stacking. Specifically, at each stage, the input features are spatially transformed via the WCB module, generating images enriched with high-order semantic information. These images are then fused with low-level features extracted by the backbone using the DCF module. After progressive layer-by-layer processing, the final segmentation is achieved by the ERS module.

Figure 4.

Structure of WaveEdgeNet.

- (1)

- WCB (Wavelet-Convolution Block)

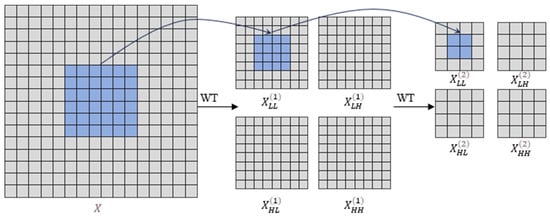

For the training data of size C*H*W, it is initially decomposed into four sub-bands (LL, LH, HL, and HH) using the discrete wavelet transform (DWT), as shown in Figure 4d and Figure 5. The LL sub-band captures the low-frequency component, emphasizing the overall morphology of the plant [27]. In contrast, the LH, HL, and HH sub-bands represent high-frequency detail components in the horizontal, vertical, and diagonal directions, respectively, which are critical for extracting edge and texture features of the plant. Each sub-band undergoes independent grouped convolution to enhance the target’s frequency characteristics. Subsequently, the four extracted sub-band features are fused through the Inverse Discrete Wavelet Transform (IDWT) and then weighed and integrated with the original features. This process improves the boundary segmentation accuracy of invasive plants in complex vegetation backgrounds. The specific expression is as follows:

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of wavelet operation.

Among them, is a low-pass filter, and represent high-pass filters for extracting horizontal, vertical, and diagonal directions, respectively. represents the downsampling operation.

- (2)

- DCF (Dynamic Context Fusion module)

The DCF (Figure 4c) first constructs both the spatial attention unit and the channel attention unit [28]. The spatial attention unit employs horizontal and vertical orthogonal strip pooling to extract the spatial features of Mikania micrantha, thereby constructing a direction-sensitive spatial weight matrix. The channel attention unit incorporates a lightweight squeeze-and-excitation structure, which compresses spatial information via global average pooling and dynamically suppresses channel responses that are spectrally similar to those of background dynamic weighting. Consequently, this allows the model to not only preserve image details more effectively but also simultaneously emphasize critical information within the image. The specific expression is as follows:

Among them, denotes spatial attention, while and denote one-dimensional convolutions. and respectively, refer to the adaptive average pooling in the horizontal and vertical directions. stands for the multi-layer perceptron, stands for the global average pooling layer, and is a learnable weight parameter.

- (3)

- ERS (Edge-Refined Segmentation Head)

The ERS module (Figure 4b) initially conducts bilinear upsampling on deep features and integrates them with shallow, high-resolution features via a residual dual-path structure. In the main path, a 3 × 3 convolution is employed to capture local details, while the residual path utilizes a 1 × 1 convolution to preserve the original feature distribution, thereby preventing information loss. Subsequently, a collaborative attention mechanism is incorporated. Within this mechanism, pixel attention leverages a 7 × 7 depthwise separable convolution to model the local geometric structure and enhance the response to vegetation edges. Channel attention leverages global compression to identify target channels, suppress background interference, and enhance the pixel-level positioning accuracy for Mikania micrantha. The specific expression is as follows:

denotes the features from the deep layer, denotes the features from the shallow layer, stands for the spatial attention mechanism, represents the depthwise separable convolution, stands for the channel attention mechanism, represents the multi-layer perceptron, represents the global average pooling, represents a depthwise separable convolution, and represents the activation function.

2.4.2. Model Training and Evaluation

To evaluate the performance of the proposed WaveEdgeNet model, ablation studies were initially conducted on the three modules of WaveEdgeNet—WCB, DCF, and ERS. Additionally, several state-of-the-art deep learning models used for image segmentation, such as Segformer [29], Dcswin [30], Segnext [31], Swin-Transformer, and LetNet [32], were also trained on the Mikania micrantha dataset. A standardized training strategy was applied to ensure a fair comparison across all models using the same Mikania micrantha dataset.

All experiments were carried out on an identical high-performance computing platform to guarantee the consistency of the experimental results. The hardware configuration of this platform is as follows: it is equipped with an Intel Core i9-13900K processor, 128 GB of DDR5 memory, and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4070 GPU. The software environment is built upon Ubuntu 22.04 LTS, employing the PyTorch 2.1.0 deep learning framework, and integrating CUDA 12.1 and cuDNN 8.9.0. Regarding model parameter optimization, the AdamW optimizer is utilized, with the key parameters set as follows: the initial learning rate is 10−4, the weight decay rate is 0.01, the decay rates for the first and second moment estimations are 0.9 and 0.999, respectively, and the numerical stability constant is 10−8. During the training process, mixed-precision calculation is adopted to enhance the computing speed and reduce memory usage. To address the class imbalance problem in the Melograna segmentation, the loss function employs a linear combination of DiceLoss and FocalLoss, with the weights of both being 0.5.

In this study, mIoU, Acc, IoU, F-score, Precision, and Recall are further employed as evaluation metrics to comprehensively assess the segmentation performance of models. Specifically, true positive (TP) denotes the number of target pixels that are accurately predicted as belonging to the target class. False positive (FP) refers to the number of pixels from non-target classes that are erroneously classified as the target class. False negative (FN) denotes the count of target pixels misclassified as non-targets. True negative (TN) indicates the number of non-target pixels accurately identified as not belonging to the target class. The calculation methods for these evaluation metrics are outlined below:

2.5. Driving Factors and Prediction of the Spread of Mikania micrantha

2.5.1. Driving Factors

Mikania micrantha represents a significant threat to local biodiversity in Shenzhen and has detrimental impacts on the regional ecosystem. Understanding the environmental factors that influence the species–area relationship of Mikania micrantha is crucial for establishing an early warning system for its invasion and for improving local ecosystem conservation strategies [33]. Socioeconomic variables and anthropogenic disturbances are widely recognized as key determinants of the spatial distribution of invasive plant species [34,35].

In this study, we incorporate a novel factor, such as proximity to different land types, to quantify the spatial interaction between human activities and natural habitats. For instance, proximity to impervious surfaces serves as an indicator of urbanization pressure on natural vegetation in peri-urban zones, whereas distance to roads reflects the role of transportation networks as dispersal corridors that facilitate the spread of invasive species through various diffusion mechanisms. In addition, environmental factors, such as topography, climate, and plant species richness, play a crucial role in describing the distribution of invasive plants [36,37,38]. In this study, vegetation indices (NDVI and EVI) were incorporated to assess their effects on Mikania micrantha distribution. Slope and elevation data were derived from DEM, while the distance to water bodies was used as a proxy for hydrological influences on seed dispersal. Daytime Land Surface Temperature (LST) was examined as an indicator of thermal stress, with high temperatures potentially constraining the establishment of invasive species. Ultimately, 17 environmental factors were selected, comprising 7 proximity-related factors, 6 vegetation indices, and 4 additional relevant factors (Table 1).

Table 1.

Information pertaining to driving factors.

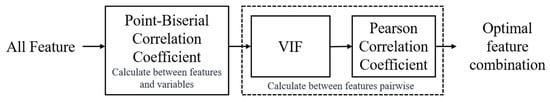

2.5.2. Construction of the Feature Selection Framework

To accurately predict the spread of invasive plants, the selection of an optimal feature subset is of utmost importance. This study employs three indicators—point-biserial correlation, Pearson correlation, and variance inflation factor—to tackle the key challenges in feature selection. Relying solely on correlation-based methods may lead to the oversight of multicollinearity, whereas multicollinearity checks often neglect the relevance of features. To surmount these issues, we put forward a phased framework: initially, screen features by utilizing point-biserial and Pearson correlations to evaluate their relationship with the target; subsequently, apply the variance inflation factor to eliminate multicollinear features. This approach guarantees strong predictive power, model stability, and interpretability. Although each individual method is well-established, their integration for invasive species modeling is still a novel concept. The framework provides a well-balanced solution for efficient and robust feature selection.

- (1)

- The Point-biserial Correlation Coefficient

The point-biserial correlation coefficient is a parametric statistical measure specifically designed to evaluate the linear relationship between a dichotomous variable and a continuous variable [39]. This method involves encoding binary categorical variables as 0/1 dummy variables and computing their Pearson correlation coefficients with continuous variables, thereby revealing the strength and direction of the association between the two types of data. The calculation formula is as follows:

Among them, and denote the means of the continuous variables corresponding to the two levels of the discontinuous variable, respectively. denotes the pooled standard deviation of the continuous variable, and represents the proportion of observations at each level of the discontinuous variable.

- (2)

- The Variance Inflation Factor

The variance inflation factor (VIF) is a statistical measure used to assess the severity of multicollinearity among independent variables in regression analysis. It quantifies how much the variance of an estimated regression coefficient is inflated due to correlations among the independent variables. A higher VIF indicates a greater degree of multicollinearity, which can compromise the stability and reliability of the model estimates. In practice, the following empirical method is frequently employed to evaluate variable collinearity. A VIF of 1 signifies the absence of collinearity. When 1 < VIF < 5, the collinearity is moderate and is generally acceptable for the majority of applications. When 5 < VIF < 10, the collinearity is high, which may potentially impact the stability and interpretability of the model; thus, caution should be exercised. When VIF > 10, the collinearity is severe, significantly inflating the standard deviation of the regression coefficient. As a result, the results become unreliable, and corrective measures are usually necessary.

- (3)

- Pearson Correlation Coefficient

The Pearson correlation coefficient measures both the strength and direction of the linear relationship between two continuous variables. Its value ranges from −1 to 1: a value of 1 indicates a perfect positive linear correlation, −1 indicates a perfect negative linear correlation, and 0 indicates no linear correlation. It quantifies the extent to which one variable changes linearly with respect to the other. The formula for calculating Pearson’s r is defined as the covariance of the two variables divided by the product of their standard deviations.

To reduce computational complexity, a novel feature selection framework was proposed (Figure 6). This framework incorporates the point-biserial correlation coefficient, variance inflation factor analysis, and Pearson correlation coefficient analysis. By integrating these three statistical methods, the framework facilitates the identification of the most effective combination of features, while preserving both model accuracy and computational efficiency.

Figure 6.

Feature selection framework.

2.5.3. Mikania micrantha Expansion Potential Calculation

The Maximum Entropy Model (MaxEnt) is a widely utilized ecological niche modeling technique for predicting the spread trends of invasive plants and simulating their potential distribution areas with high accuracy [40,41]. Its fundamental principle is to choose the probability distribution that maximizes entropy while adhering to known environmental constraints, thereby reducing the bias introduced by prior assumptions. The specific formula of the MaxEnt model is as follows:

Among them, denotes the probability of existence under environmental conditions , represents the characteristic weight associated with the -th environmental variable, and signifies the environmental feature function. The complexity and performance of MaxEnt are primarily determined by the feature combinations (FCs) and regularization multipliers (RMs) within the model. These parameters play a crucial role in shaping the MaxEnt model’s behavior and accuracy. To enhance the accuracy and reliability of the model’s prediction results, six FC combinations—namely H, L, LQ, LQH, LQHP, and LQHPT (where L denotes linear, Q denotes quadratic, H denotes fragmented, P denotes product, and T denotes threshold)—along with RM values (0.1, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3), are utilized to compute the Akaike information criterion corrected (AICc). This evaluation assesses both the goodness-of-fit and the complexity of the model [42]. Finally, the parameter combination of FC = LQHP and RM = 0.1 was selected for modeling.

3. Results

3.1. Evaluation Performance of the WaveEdgeNet Model

3.1.1. Ablation Experiment

To verify the effectiveness of each module, this study incrementally integrated each module into the baseline network and performed ablation experiments. The baseline network of WaveEdgeNet is U-NetFormer, which employs ResNet50 as its backbone.

The results of ablation experiments (Table 2) demonstrated that the WCB module enables WaveEdgeNet to effectively disentangle high-frequency detail features from low-frequency structural features, thereby significantly enhancing the model’s texture extraction capability for Mikania micrantha. As shown in R1 and R3, integrating the WCB module into a basic network improves segmentation performance, with mIoU increasing from 77.66% to 82.23% and F-score rising from 72.98% to 79.72%. These results indicate that the WCB module not only strengthens Mikania micrantha recognition but also enhances background classification accuracy. Additionally, R5 and R9 confirm that incorporating the WCB module into more complex networks similarly boosts segmentation outcomes. R1 and R2 illustrate that the DCF module substantially enhances segmentation performance, as evidenced by improvements across all metrics. Compared to R4, which includes only the ERS module, adding either the DCF or WCB module achieves superior segmentation results. R6 and R8 reveal that removing the DCF module leads to a notable decline in performance, with mIoU dropping from 85% to 83.97% and IoU decreasing from 71.42% to 69.47%. Furthermore, R7 and R8 indicated that while the ERS module slightly improves overall accuracy, its contribution to segmentation performance remains limited.

Table 2.

The results of the ablation studies for the proposed WaveEdgeNet model.

3.1.2. Module Effectiveness Experiment

The DCF module enables cross-level interaction between high-level semantic features and low-level detailed features through a dynamic context-aware mechanism. To validate the advantages of the DCF module in feature fusion, we conducted an experiment by replacing it with alternative modules and assessing the subsequent changes in the model’s segmentation performance (Table 3).

Table 3.

Module Effectiveness Experiment Result Table.

The results illustrated that incorporating the DCF module leads to an increase in mIoU by over 1% and an improvement in IoU by more than 3%. By contrasting C1 and C4, it is evident that despite similar precision metrics, the recall value of C1 is approximately 6% lower than that of C4, indicating the DCF module’s superior effectiveness in addressing missed detections of Mikania micrantha. Additionally, all metrics for C1, C2, and C3 are inferior to those of C4, underscoring the DCF module’s exceptional ability to extract texture features of Mikania micrantha.

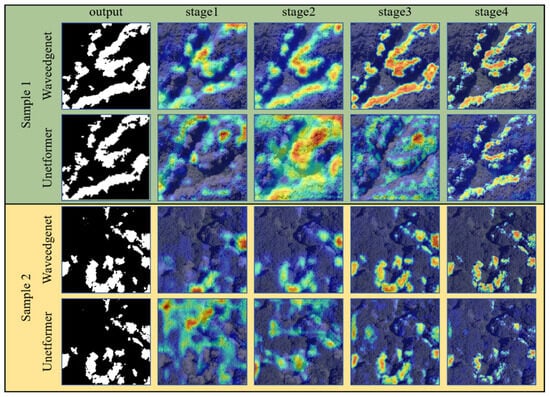

To further investigate the disparities in feature extraction capabilities between WaveEdgeNet and Unetformer, the feature maps from each layer of both models are extracted. The weights of these feature maps can be interpreted as the amount of effective information retained after being processed by successive convolutional kernels. As shown in Figure 7, which displays the features extracted at varying hierarchical levels using WaveEdgeNet and Unetformer, it is evident that WaveEdgeNet outperforms Unetformer in rapidly capturing Mikania micrantha features in the first and second layers of the model.

Figure 7.

Features extracted at varying hierarchical levels using WaveEdgeNet and Unetformer. (The yellow and green backgrounds represent two distinct samples. A higher weight signifies a more significant feature that plays a more critical role in the network’s prediction performance.)

3.2. The Results of Recognized Mikania micrantha

3.2.1. Assessment of the Mikania micrantha Segmentation Model

In this study, the training set and the test set were used to independently train the proposed WaveEdgeNet and the comparative semantic segmentation models. All models adopted ResNet50 as the backbone network and underwent three repeated training sessions. Thereafter, the average of the results from these three trials was calculated and utilized as the segmentation accuracy metric, thereby improving the reliability of the evaluation (Table 4).

Table 4.

The metrics of various segmentation models.

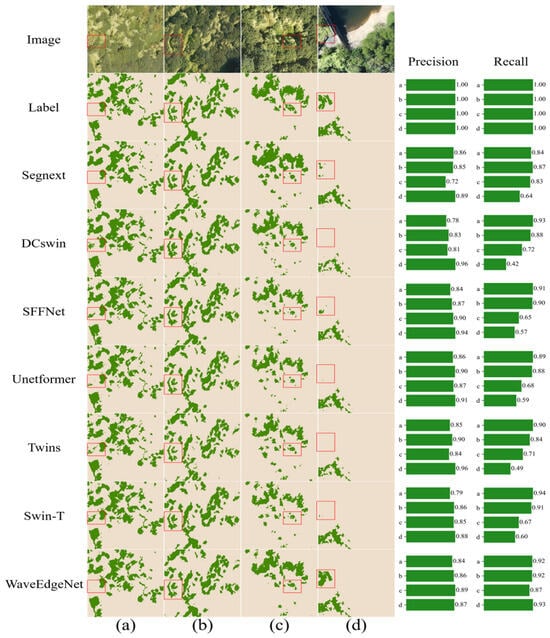

The results illustrated that WaveEdgeNet exhibited the highest segmentation performance on the test set, achieving an ACC of 98.62%, an mIoU of 85.00%, and an F1-score of 83.33%. Comparative models such as Swin-T, Twins, SFFNet, and Unetformer demonstrated relatively lower performance compared to WaveEdgeNet. Notably, Swin-T and Twins ranked second in terms of overall performance across multiple evaluation metrics; however, their performance was still significantly lower than that of WaveEdgeNet. Among these models, Swin-T achieved the lowest miss rate for detecting Mikania micrantha, with the highest Recall score among all networks, but its accuracy was relatively low. Segformer, LetNET, Dcswin, and Segnext performed even worse, failing to achieve an IoU of 68% or an F1-score of 80%, despite extended training. Segformer showed the worst results, with an IoU of 61.01% and an F1-score of 75.79%. WaveEdgeNet demonstrated improvements in segmentation performance, surpassing Swin-T by 0.12% in ACC, 1.00% in F1-score, and 1.46% in IoU. These results indicate that WaveEdgeNet outperforms other networks in Mikania micrantha feature extraction(Table 5).

Table 5.

Table of t-test results.

Figure 8 provides a visual comparison of the segmentation results achieved by WaveEdgeNet and other comparative models within a representative Mikania micrantha distribution area from the test dataset. As shown, WaveEdgeNet demonstrates significantly superior performance in Mikania micrantha extraction. Specifically, in areas where Mikania micrantha features are less distinct (column (d) of Figure 8), WaveEdgeNet exhibits enhanced recognition accuracy compared to other models, which typically suffer from missegmentation issues. Additionally, for plants with morphological similarities to Mikania micrantha (column (a) of Figure 8), most comparative models, except for SegNeXt, tend to generate misidentifications. These observations further validate the robust feature discrimination capability of the WaveEdgeNet model in complex scenarios.

Figure 8.

Segmentation results of WaveEdgeNet and other models on the test set (four samples have been extracted to show the extraction results of different models. Image represents the original image, Label represents the true label. (a–d) correspond to the four samples, respectively. The names of models in the left, Precision and Recall of Mikania micrantha extraction in the right).

3.2.2. The Spatial Distribution of Mikania micrantha

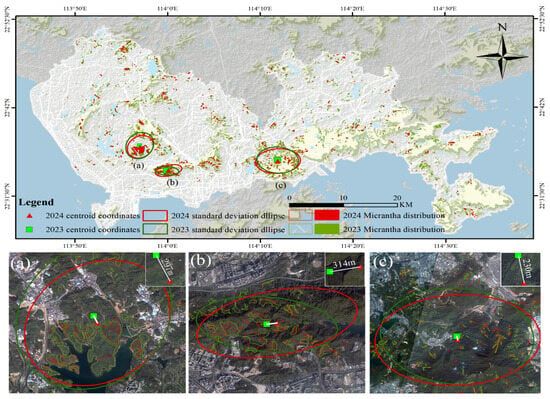

In this study, UAV images acquired in Shenzhen in 2023 and 2024 were preprocessed to generate orthophoto images of areas with potential Mikania micrantha occurrences in Shenzhen. Subsequently, the optimally trained WaveEdgeNet model was employed to recognize Mikania micrantha occurrence from the annual UAV orthophoto images. Ultimately, distribution maps of Mikania micrantha for both 2023 and 2024 were successfully generated (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

The spatial distribution of Mikania micrantha extracted by WaveEdgeNet in 2023 and 2024. (The red color represents the distribution in 2024, and the green color represents the distribution in 2023. (a–c) represent the areas in Shenzhen that the morning glory plant has severely infested. The centroids and standard deviation ellipses within these subplots have been calculated for these areas.)

The centroid shifts and standard deviational ellipse were employed to analyze three areas heavily impacted by Mikania micrantha (Figure 9). The results show that the center of gravity in the Xili Reservoir area (Figure 9a) has shifted 297 m southward, and the standard deviation ellipse has contracted southward. This indicates effective control of Mikania micrantha in the northern part of the region through artificial prevention. However, near the southern edge of the reservoir, the recurrence rate remains high due to limitations in chemical and manual control methods. Additionally, the presence of low-value artificial economic forests creates an ideal environment for Mikania micrantha invasion. The center of gravity of Tanglang Mountain (Figure 9b) has shifted eastward, and the direction of the standard deviation ellipse has changed from “southeast-northwest” to “northeast-southwest,” indicating Mikania micrantha’s eastward spread. Artificial prevention and control measures at the northwest corner of Tanglang Mountain have effectively curbed its spread in this region. However, the central part still shows a high recurrence rate due to the mountainous terrain challenging chemical control operations. WutongMountain’s (Figure 9c) Mikania micrantha spreads southward with extensive distribution. Chemical control near urban streets significantly reduced recurrence; however, the central mountainous regions still have persistently high recurrence rates.

3.3. Feature Selection Results and Analysis

Based on the spatial distribution of Mikania micrantha extracted using the proposed WaveEdgeNet in 2023 and 2024, the dataset from 2023 was utilized as the training set, while the 2024 dataset served as the validation set. Various combinations of feature selection methods were employed to screen relevant environmental variables, followed by training the MaxEnt model to evaluate the performance of each method.

In this study, the threshold value for the Pearson correlation coefficient was set at 0.2, and the threshold value for VIF was set at 15. Additionally, another threshold value for the Pearson correlation coefficient was set at 0.8.

Experimental results show that the benchmark model (Table 6), which incorporated all 17 features, achieved an AUC of 83.24% on the test set. To improve training efficiency, traditional feature selection techniques, including VIF, Pearson correlation, and point-biserial correlation, were assessed, along with their combinations. Although these approaches reduced the number of features and shortened training time, they all led to a drop in AUC and failed to outperform the benchmark model. This underscores the challenge traditional approaches face in preserving critical discriminative information during feature reduction, leading to a trade-off between model accuracy and computational efficiency. In contrast, the proposed feature selection framework exhibits significant advantages in this study. It identifies only eight key features and achieves a test AUC of 83.86%. This approach not only outperforms existing dimensionality reduction techniques but also improves upon the benchmark by 0.62 percentage points, thereby demonstrating its effectiveness in preserving predictive information. Regarding computational efficiency, the proposed framework performs exceptionally well, reducing training time to 17.39% of that required by the benchmark while decreasing the number of features by 52.9%. This improvement in efficiency can be attributed to the streamlined feature space and optimized algorithmic structure.

Table 6.

Feature Selection Framework Result Table.

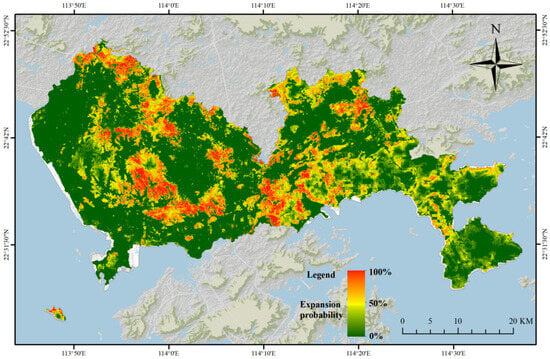

3.4. Results of the Future Occurrence Probability of Mikania micrantha

Based on the MaxEnt model trained using the optimal feature set, we predicted the potential future spread of Mikania micrantha (Figure 10). In this figure, red denotes areas with a relatively high probability of occurrence, whereas green indicates areas with a relatively low probability. In terms of spatial extent, the area with an occurrence probability exceeding 80% is approximately 162 square kilometers, accounting for about 8% of Shenzhen’s total area. The area with an occurrence probability greater than 50% covers approximately 498 square kilometers, or about 24% of the city’s total area. Spatially, the key prevention and control zones largely coincide with the areas where Mikania micrantha was observed in 2023 and 2024. For instance, Xili Reservoir and Wutong Mountain remain high-incidence zones, suggesting that these existing invasion sites have strong ecological colonization potential. In contrast, Pingshan District in the northeast and Guangming District in the northwest had no recorded occurrences of Mikania micrantha in 2023 and 2024; however, numerous high-probability occurrence areas have been identified by the model in these regions. This suggests that Mikania micrantha may expand into these districts in the future, according to the MaxEnt model predictions, which provides valuable insights for the effective planning of future prevention and control strategies in Shenzhen, serving predictive information. Regarding computational efficiency, the proposed framework performs exceptionally well, reducing training time to 17.39% of that required by the benchmark while decreasing the number of features by 52.9%. This improvement in efficiency can be attributed to the streamlined feature space and optimized algorithmic structure.

Figure 10.

The suitable growth areas for Mikania micrantha predicted by MaxEnt.

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison of WaveEdgeNet with Other Segmentation Algorithms

In Potsdam and ISPRS Vaihingen segmentation tasks, researchers have shown that Unetformer achieves superior accuracy and efficiency compared to Segformer in terms of MIoU and Flops. This is attributed to Unetformer’s development of an efficient global–local attention mechanism, which enables it to capture both global and local contexts of visual perception. Additionally, Unetformer effectively integrates spatial details and contextual information via a feature optimization head. SegFormer, leveraging the hierarchical architecture of the Pyramid Vision Transformer, directly transmits high-resolution feature maps from the encoder to the decoder network. This leads to the fusion of feature maps with disparate semantics, thereby negatively impacting segmentation performance. Unetformer has shown that a model combining local and global features can achieve superior overall object segmentation performance; however, in the Mikania micrantha task, traditional convolutions are constrained by their local receptive field during spatial feature extraction, which limits their ability to capture high-frequency edge details. As the network deepens, contour details tend to fade. The proposed WaveEdgeNet addresses the problem of deep network by extracting high-frequency edge detail features during the data construction process and integrating the multi-scale design concept with Unetformer architecture.

The outstanding performance of WaveEdgeNet in the Mikania micrantha segmentation task (mIoU 85%, F-score 83.33%) is not merely attributable to the enlargement of the model size. Rather, it reflects the effective integration of frequency-domain and spatial-domain collaborative modeling, as well as its dynamic feature selection mechanism tailored for complex vegetation scenarios. Specifically, WaveEdgeNet employs the DWT to decompose input features into low-frequency (LL) and high-frequency (LH/HL/HH) sub-bands, thereby explicitly amplifying the response of the target frequency band [43]. Unlike Pyramid Vision Transformer (PVT), WaveEdgeNet uses wavelet basis functions like Haar wavelets, which are physically interpretable. Their frequency band separation characteristics enable quantitative analysis of feature contributions [44]. While WaveEdgeNet has a larger number of parameters (56.2 M) and FLOPs (231 G) compared to the lightweight model LetNET (0.9 M), it achieves an effective balance between efficiency and accuracy by leveraging hierarchical frequency domain decomposition and residual connection optimization. WaveEdgeNet attains higher recognition accuracy at the expense of increased computational complexity, which represents a trade-off that we aim to enhance in future work. Since this study solely utilized drone data of Milege virgata from Shenzhen City and lacked cross-regional validation, and considering that the species only flowers in November, the recognition capability of the model is restricted. Future research will concentrate on developing a model that is applicable to earlier flowering stages and wider regions to facilitate practical applications.

4.2. Analysis of Feature Selection Results

In our feature selection framework, correlation analysis is employed to assess the linear association among features. The VIF analysis detects redundant features by measuring the extent of multicollinearity [45]. In contrast, point-biserial correlation is specifically applied to evaluate the linear relationship between a binary target variable and continuous predictor variables. These three methods collectively enhance the robustness of the feature selection process by addressing different aspects of feature interdependence.

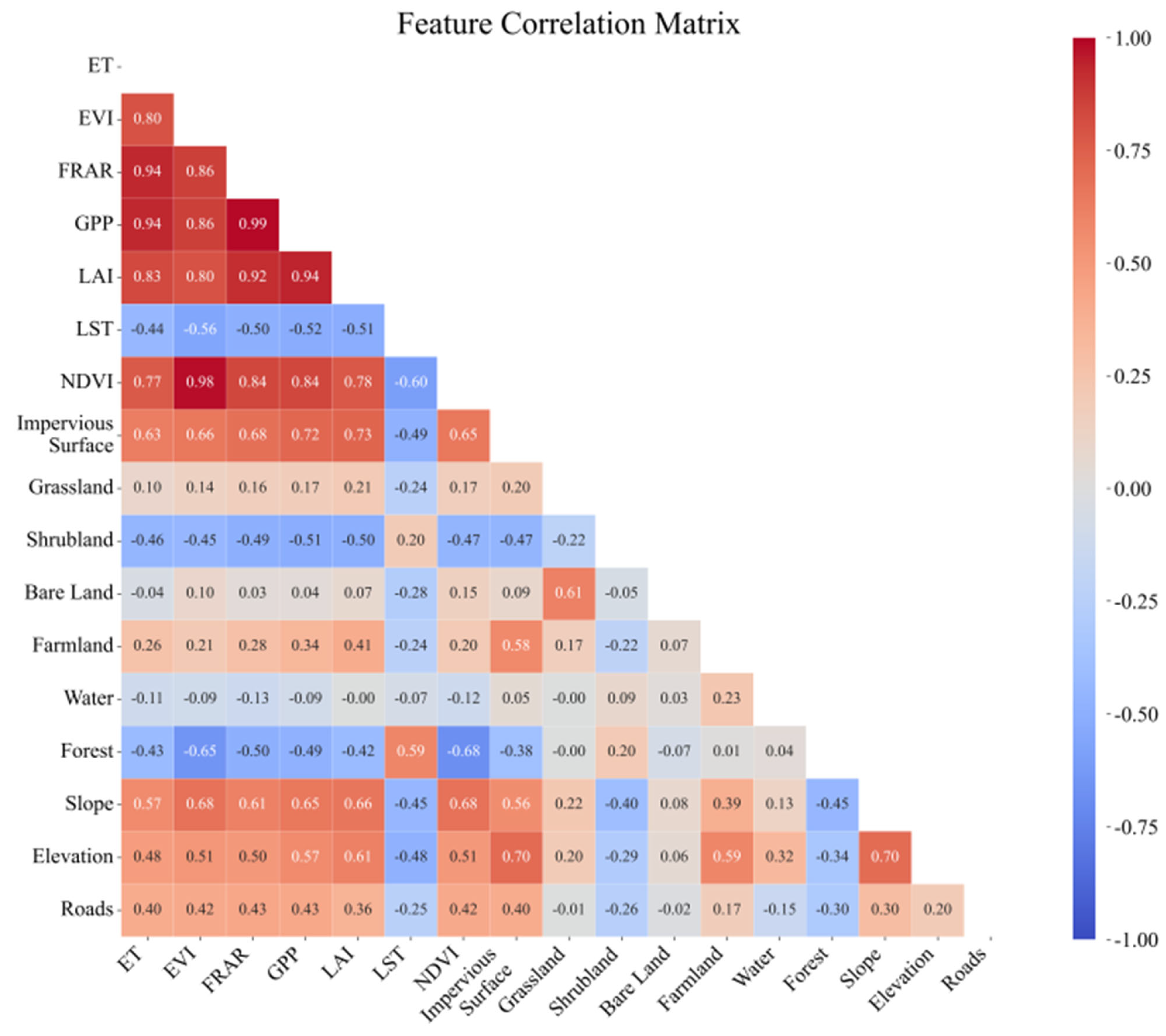

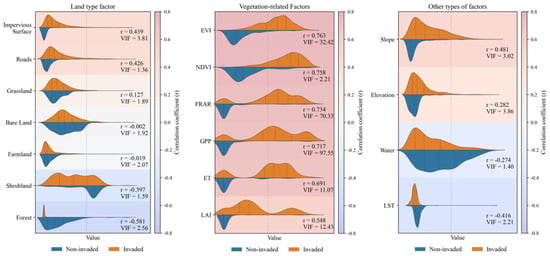

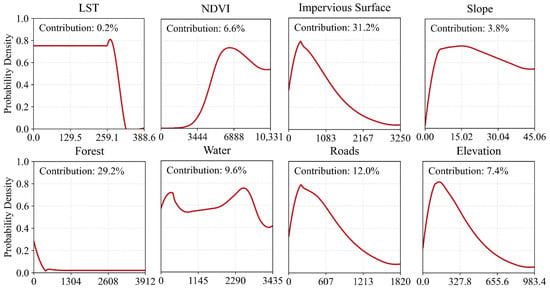

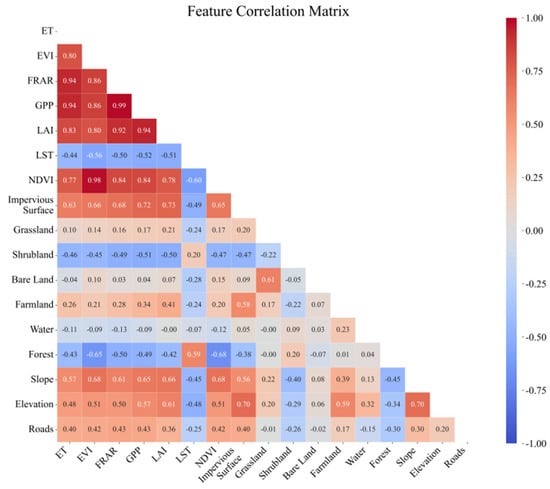

For example, the analysis revealed (Figure 11 and Figure 12) that vegetation index features (e.g., NDVI, EVI, GPP) exhibited significantly positive point-biserial correlations with the target variable. However, both the VIF and Pearson correlation coefficients among these features were notably high, suggesting a substantial degree of multicollinearity and information redundancy. This redundancy may arise from their similar spectral calculation mechanisms and shared physical interpretations, leading to overlapping informational content. Although these features are strongly correlated with the target variable, such redundancy can undermine the model’s generalization performance [46]. In contrast, certain land use type factors demonstrated low multicollinearity (indicated by low VIF and Pearson values), implying they contain distinct and independent information. However, their correlations with the target variable were weak, making them less suitable as predictive features. The low point-biserial correlation of land use factors might be attributed to spatial heterogeneity that does not align well with the spatial pattern of the target variable. Their low multicollinearity, however, suggests their balanced selection of features that maintains both predictive accuracy and model stability through cross-validation.

Figure 11.

Point-biserial correlation and variance inflation factor (blue indicates no Mikania micrantha invasion, orange indicates presence of invasion, and the background shows the magnitude of the point-biserial correlation).

Figure 12.

Pearson correlation among various environmental factors.

The Pearson correlation, point-biserial correlation, and variance inflation factor employed in our feature selection framework are based on linear assumptions. These statistical measures enable the efficient identification of predictors that exhibit a strong linear relationship with the response variable and are mutually independent. Nevertheless, they might overlook nonlinear relationships. To more effectively capture such patterns, model- or permutation-based methods, including random forest or gradient boosting feature importance, recursive feature elimination, and permutation tests, can strengthen the framework by detecting complex dependencies. We intend to integrate these methods into our future research.

4.3. The Key Environmental Factors Obtained Based on the MaxEnt Model

In this study, road proximity, impervious surface proximity, and forest proximity were identified as the main factors influencing Mikania micrantha’s distribution (Figure 13). Together, these variables contributed 72.4% in the MaxEnt model, suggesting a strong relationship between human activity and forest cover in shaping its spread. Proximity to impervious surfaces and roads reflects human presence and mobility, which facilitate the dispersal of invasive species [36,47]. Conversely, Mikania micrantha is less likely to occur farther from forests, partly due to its dependence on trees for support as a climbing vine. Its rapid growth can overwhelm host trees, leading to their decline. Without sufficient host trees, Mikania micrantha may diminish over time. Based on the response curves of the dominant environmental factors, Mikania micrantha is more likely to thrive in areas near impervious surfaces (200–600 m), close to arbor forests (0–200 m), at low altitudes (50–300 m), and adjacent to roads (0–800 m). Its distribution does not exhibit a clear association with water sources such as lakes and rivers.

Figure 13.

The spatial distribution of Mikania micrantha extracted by WaveEdgeNet in 2023 and 2024.

The potential distribution of Mikania micrantha in Shenzhen is influenced by human activities and topography, reflecting the species’ ecological adaptation to local environmental conditions. Previous studies have shown that temperature is a key factor affecting its distribution [48,49,50]. However, this study found no significant correlation between land surface temperature (LST) and species’ distribution. LST contributed only 0.2% to the model, which differs from earlier findings. This inconsistency may be due to Shenzhen’s small north–south span—only 68 km—and its location entirely within a subtropical monsoon climate zone, where temperature variation has less influence compared to other environmental factors. In addition, Rameshprabu, N. reported that in the assessment of Mikania micrantha distribution, altitude gradient was identified as the factor showing the most significant difference in occurrence frequency. Specifically, as altitude increases, the frequency of Mikania micrantha occurrence tends to decrease [51]. This finding aligns with the results of this study, indicating that altitude plays a dominant role in the geographical distribution of Mikania micrantha and exhibits a negative correlation. This could be attributed to altitude indirectly influencing the spread of Mikania micrantha via light intensity, temperature, and precipitation. In high-altitude regions, although light intensity is higher, precipitation tends to be lower. Conversely, in low-altitude areas, light intensity is relatively weaker, but precipitation is more abundant. Consequently, as altitude increases, the suitability for Mikania micrantha growth decreases. When altitude exceeds 600 m, the suitability for Mikania micrantha growth approaches zero.

Under current climate conditions, Mikania micrantha in Shenzhen has a much larger potential habitat than its current range, indicating strong invasiveness. Introduced as an ornamental plant through trade, it later spread via vehicles, humans, or animals into forested areas. Future expansion is likely in highly suitable regions such as Wutong Mountain and Xili Reservoir, increasing invasion risks. Human activity significantly contributes to its spread and should be considered in control strategies. Field observations show that its pollen and flowers can attach to clothing and shoes, enabling long-distance dispersal. Therefore, priority management should focus on highly suitable northern and eastern areas of Shenzhen, with increased monitoring in places of high human activity to prevent further spread. While this study examined natural and land use factors influencing Mikania micrantha distribution, many studies highlight precipitation as a key factor [51]. Precipitation data was unavailable, so it was not included. Socioeconomic factors may also play a role and should be explored in future research.

5. Conclusions

This study focuses on the area in Shenzhen that is severely affected by the vine weed. A recognition model based on unmanned aerial vehicles was developed using RGB images and deep learning segmentation technology. During the period from 2023 to 2024, the temporal and spatial dynamics of the spread of the vine weed and its key environmental driving factors were studied, with a focus on predicting possible expansion areas in the future. The main contributions of this study are summarized as follows: A new image segmentation model named WaveEdgeNet was proposed. This study innovatively incorporated land use distance into the analysis and constructed a framework for selecting driving factors. The final experimental results are as follows: The mIoU of the WaveEdgeNet model on the test dataset is 85.00%, and the accuracy rate is 98.62%. Compared with existing methods, it performs better in species detection. The driving factor selection framework effectively reduces the computational load by 82.6% while improving the accuracy of the MaxEnt model. Additionally, after feature selection and model training using the maximum entropy algorithm, human activity interference and proximity to forest areas were identified as the most important factors affecting the distribution of the vine weed, contributing 60.2% to the model. Altitude and distance from roads were also recognized as key driving factors. Finally, the prediction of future spread based on current climate conditions indicates that the potential habitat of the vine weed in Shenzhen is significantly larger than its current distribution range. The species may expand to ecologically suitable areas such as Wutong Mountain and Xili Reservoir, thereby increasing the risk of invasion. This study provides a scientific basis for the management of the vine weed in Shenzhen. Future research should enhance the generalization ability and robustness of the model to enable accurate monitoring in larger and more complex areas. Additionally, the influence of social and cultural factors on the spread of the vine weed should also be studied.

Author Contributions

Methodology, Y.Y.; Investigation, Y.Y. and X.H.; Writing—original draft, Y.Y.; Writing—review & editing, H.L., J.L., T.Z., Z.Y. and X.D.; Visualization, Y.Y.; Funding acquisition, X.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author (the data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions).

Acknowledgments

We would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their useful comments and constructive suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Xiaofen He was employed by the company Changsha Changchang Forestry Technology Consulting Co., Ltd. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nota, A.; Bertolino, S.; Tiralongo, F.; Santovito, A. Adaptation to bioinvasions: When does it occur? Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e17362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, D.R.; Kato-Noguchi, H. Defensive mechanisms of Mikania micrantha likely enhance its invasiveness as one of the world’s worst alien species. Plants 2025, 14, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, B.; Liao, W.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Zan, Q. Progress in studies on an exotic vicious weed mikania micrantha. Ying Yong Sheng Tai Xue Bao J. Appl. Ecol. 2002, 13, 1684–1688. [Google Scholar]

- Saranya, K.R.L.; Satish, K.V.; Reddy, C.S. Remote sensing enabled essential biodiversity variables for invasive alien species management: Towards the development of spatial decision support system. Biol. Invasions 2024, 26, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müllerová, J.; Brundu, G.; Grosse-Stoltenberg, A.; Kattenborn, T.; Richardson, D.M. Pattern to process, research to practice: Remote sensing of plant invasions. Biol. Invasions 2023, 25, 3651–3676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Roberts, D.A.; Stow, D.A.; An, L.; Hall, S.J.; Yabiku, S.T.; Kyriakidis, P.C. Mapping understory invasive plant species with field and remotely sensed data in chitwan, nepal. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 250, 112037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandwal, R.; Jeganathan, C.; Tolpekin, V.; Kushwaha, S.P.S. Discriminating the invasive species, ‘lantana’ using vegetation indices. J. Indian Soc. Remote 2009, 37, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, J.P.; Watt, M.S.; Paul, T.S.H.; Morgenroth, J.; Hartley, R. Taking a closer look at invasive alien plant research: A review of the current state, opportunities, and future directions for uavs. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2019, 10, 2020–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaka, M.M.; Samat, A. Advances in remote sensing and machine learning methods for invasive plants study: A comprehensive review. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakgoale, P.B.; Ngetar, S.N. Detecting invasive alien plant species using remote sensing, machine learning and deep learning. J. Sens. 2024, 2024, 8854675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, G. Uav imagery real-time semantic segmentation with global–local information attention. Sensors 2025, 25, 1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahal, A.; Murad, S.A.; Rahimi, N. Heuristical comparison of vision transformers against convolutional neural networks for semantic segmentation on remote sensing imagery. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 17364–17373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, C.; McGuinness, K.; Perrin, P.M.; O’Connell, J.; Martin, J.R.; Connolly, J. Improving the mapping of coastal invasive species using uav imagery and deep learning. Int. J. Remote. Sens. 2023, 44, 5713–5735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.F.; Cheng, M.; Xiao, X.P.; Yuan, H.B.; Zhu, J.J.; Fan, C.H.; Zhang, J.L. An image segmentation method based on deep learning for damage assessment of the invasive weed solanum rostratum dunal. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 188, 106320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollachica, D.A.H.; Asante, B.K.A.; Imamura, H. Advancing water hyacinth recognition: Integration of deep learning and multispectral imaging for precise identification. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Tang, Q.H.; Zong, D.L.; Hu, X.K.; Wang, B.R.; Wang, T. Drivers of species distribution and niche dynamics for ornamental plants originating at different latitudes. Diversity 2023, 15, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visztra, G.V.; Frei, K.; Hábenczyus, A.A.; Soóky, A.; Bátori, Z.; Laborczi, A.; Csikós, N.; Szatmári, G.; Szilassi, P. Applicability of point- and polygon-based vegetation monitoring data to identify soil, hydrological and climatic driving forces of biological invasions-a case study of Ailanthus altissima, Elaeagnus angustifolia and Robinia pseudoacacia. Plants 2023, 12, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, E.F.; Wang, Y.H. Identifying driving factors of ecosystem service trade-offs in mountainous region of southwestern china across geomorphic and climatic types. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Li, L.; Yu, H.N.; Zhu, W.H.; Hou, M.Z.; Yu, J.T.; Yuan, M.; Yu, Z.Q. Modeling current and future distributions of invasive Asteraceae species in northeast china. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuddington, K.; Sobek-Swant, S.; Drake, J.; Lee, W.; Brook, M. Risks of giant hogweed (Heracleum mantegazzianum) range increase in north america. Biol. Invasions 2022, 24, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorbe, F.; Gränzig, T.; Förster, M. Evaluating sampling bias correction methods for invasive species distribution modeling in maxent. Ecol. Inform. 2023, 76, 102124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakhil, M.A.; El-Keblawy, A.; El-Sheikh, M.A.; Halmy, M.W.A.; Ksiksi, T.; Hassan, W.A. Global invasion risk assessment of Prosopis juliflora at biome level: Does soil matter? Biology 2021, 10, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.X.; Zhu, L.X. A review on unmanned aerial vehicle remote sensing: Platforms, sensors, data processing methods, and applications. Drones 2023, 7, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2015; Navab, N., Hornegger, J., Wells, W.M., Frangi, A.F., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Rahman Siddiquee, M.M.; Tajbakhsh, N.; Liang, J. Unet++: A nested u-net architecture for medical image segmentation. In Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis and Multimodal Learning for Clinical Decision Support; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Li, R.; Zhang, C.; Fang, S.; Duan, C.; Meng, X.; Atkinson, P.M. Unetformer: A unet-like transformer for efficient semantic segmentation of remote sensing urban scene imagery. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2022, 190, 196–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finder, S.E.; Amoyal, R.; Treister, E.; Freifeld, O. Wavelet convolutions for large receptive fields. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2024; Leonardis, A., Ricci, E., Roth, S., Russakovsky, O., Sattler, T., Varol, G., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 363–380. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.X.; He, Z.W.; Lu, Z.M. Dea-net: Single image dehazing based on detail-enhanced convolution and content-guided attention. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2024, 33, 1002–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, E.; Wang, W.; Yu, Z.; Anandkumar, A.; Alvarez, J.M.; Luo, P. Segformer: Simple and efficient design for semantic segmentation with transformers. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 12077–12090. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Li, R.; Duan, C.; Zhang, C.; Meng, X.; Fang, S. A novel transformer based semantic segmentation scheme for fine-resolution remote sensing images. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 19, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.-H.; Lu, C.-Z.; Hou, Q.; Liu, Z.; Cheng, M.-M.; Hu, S.-M. Segnext: Rethinking convolutional attention design for semantic segmentation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 1140–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, G.; Li, J.; Gao, G.; Lu, H.; Yang, J.; Yue, D. Lightweight real-time semantic segmentation network with efficient transformer and cnn. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 15897–15906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Wang, M.; Yuan, L.L.; Chen, H.; Yan, L.Y.; Yao, S.T.; Zhang, B.P. Local grasses for the control of the invasive vine Mikania micrantha. J. Plant Ecol. 2022, 15, 844–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffa, G.; Gaetan, C.; Piccoli, S.; Del Vecchio, S.; Fantinato, E. Using fine-scale field data modelling for planning the management of invasions of Oenothera stucchii in coastal dune systems. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 125, 107564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Lillo, E.; Lembrechts, J.J.; Cavieres, L.A.; Jiménez, A.; Haider, S.; Barros, A.; Pauchard, A. Anthropogenic factors overrule local abiotic variables in determining non-native plant invasions in mountains. Biol. Invasions 2021, 23, 3671–3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.P.; Zhao, J.; Chen, Y.B.; Chen, H.; Lin, N.; Qiu, R.Z. Spatial variation and driving factors of invasive plants in fujian province, china. Ying Yong Sheng Tai Xue Bao J. Appl. Ecol. 2019, 30, 2682–2690. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y.Q.; Xie, X.R.; Weng, F.F.; Nong, L.B.; Lin, M.N.; Ou, J.Y.; Wang, Y.X.; Mao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Qian, Z.J.; et al. Distribution patterns and environmental determinants of invasive alien plants on subtropical islands (fujian, china). Forests 2024, 15, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.Q.; Huang, H.; Xie, X.R.; Ou, J.Y.; Chen, Z.; Lu, X.X.; Kong, D.Y.; Nong, L.B.; Lin, M.N.; Qian, Z.J.; et al. Landscape, human disturbance, and climate factors drive the species richness of alien invasive plants on subtropical islands. Plants 2024, 13, 2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Liu, H.Y. A short note on the maximal point-biserial correlation under non-normality. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 2016, 69, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saranya, K.R.L.; Lakshmi, T.V.; Reddy, C.S. Predicting the potential sites of chromolaena odorata and lantana camara in forest landscape of eastern ghats using habitat suitability models. Ecol. Inform. 2021, 66, 101455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.L.; Li, S.F.; Huang, W.Y.; Jin, J.H.; Oskolski, A.A. Late pleistocene glacial expansion of a low-latitude species Magnolia insignis: Megafossil evidence and species distribution modeling. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kass, J.M.; Muscarella, R.; Galante, P.J.; Bohl, C.L.; Pinilla-Buitrago, G.E.; Boria, R.A.; Soley-Guardia, M.; Anderson, R.P. Enmeval 2.0: Redesigned for customizable and reproducible modeling of species’ niches and distributions. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2021, 12, 1602–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, B.; Chaudhuri, S.; Biswas, S.; Dey, D.; Munshi, S.; Chatterjee, B.; Dalai, S.; Chakravorti, S. Wavelet kernel-based convolutional neural network for localization of partial discharge sources within a power apparatus. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2021, 17, 1831–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xie, E.; Li, X.; Fan, D.-P.; Song, K.; Liang, D.; Lu, T.; Luo, P.; Shao, L. Pyramid vision transformer: A versatile backbone for dense prediction without convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 568–578. [Google Scholar]

- Mukaka, M.M. Statistics corner: A guide to appropriate use of correlation coefficient in medical research. Malawi Med. J. 2012, 24, 69–71. [Google Scholar]

- Salmerón, R.; García, C.B.; García, J. Variance inflation factor and condition number in multiple linear regression. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 2018, 88, 2365–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilà, M.; Espinar, J.L.; Hejda, M.; Hulme, P.E.; Jarošík, V.; Maron, J.L.; Pergl, J.; Schaffner, U.; Sun, Y.; Pyšek, P. Ecological impacts of invasive alien plants: A meta-analysis of their effects on species, communities and ecosystems. Ecol. Lett. 2011, 14, 702–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Huang, Q.; Kuang, Y.Z.; Clements, D.R.; Xu, G.F.; Zhang, F.D.; Shen, S.C.; Yin, L.; Day, M.D. Predicting the potential distribution of the invasive weed Mikania micrantha and its biological control agent Puccinia spegazzinii under climate change scenarios in china. Biol. Control 2025, 204, 105754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, M.R.; Deb, P.; Singha, H.; Chakdar, B.; Medhi, M. Predicting the probable distribution and threat of invasive Mimosa diplotricha suavalle and Mikania micrantha kunth in a protected tropical grassland. Ecol. Eng. 2016, 97, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.Q.; Zhang, X.H.; Wei, H.Y.; Wang, D.J.; Chen, R.D.; Wang, L.K.; Gu, W. Predicting the invasive trend of exotic plants in china based on the ensemble model under climate change: A case for three invasive plants of asteraceae. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 756, 143841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rameshprabu, N.; Swamy, P.S. Prediction of environmental suitability for invasion of Mikania micrantha in india by species distribution modelling. J. Environ. Biol. 2015, 36, 565–570. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.