Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Three boundary layer height (BLH) retrieval methods—HWCT, Var, and Parcel—show overall consistency, with DWL_Var and DWL_HWCT being the most correlated (R = 0.62) and MWR_Parcel exhibiting a systematic positive bias of approximately 0.5 km.

- Case analyses under clear-sky, cloudy, and hazy conditions reveal that each method responds differently to aerosol, turbulence, and thermodynamic structures, highlighting their complementary strengths.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- The joint use of lidar and radiometer retrievals provides a more comprehensive depiction of the boundary layer from material, dynamic, and thermodynamic perspectives.

- The results offer guidance for developing adaptive, multi-sensor BLH retrieval frameworks and improving air quality and boundary-layer parameterization in complex meteorological conditions.

Abstract

Understanding the evolution of the atmospheric boundary layer height (BLH) is essential for characterizing air–surface exchange and air pollution processes. This study investigates the consistency and applicability of three BLH retrieval methods based on multi-source remote sensing observations at Beijing Southern Suburb station during autumn–winter 2023. Using Doppler wind lidar (DWL) and microwave radiometer (MWR) data, the Haar wavelet covariance transform (HWCT), vertical velocity variance (Var), and parcel methods were applied, and 10 min averages were used to suppress short-term fluctuations. Statistical analysis shows good overall consistency among the methods, with the strongest correlation between HWCT and Var method (R = 0.62) and average systematic positive bias of 0.4–0.6 km for the parcel method. Case studies under clear-sky, cloudy, and hazy conditions reveal distinct responses: HWCT effectively captures aerosol gradients but fails under cloud contamination, the Var method reflects turbulent dynamics and requires adaptive thresholds, and the Parcel method robustly describes thermodynamic evolution. The results demonstrate that the three methods are complementary in capturing the material, dynamic, and thermodynamic characteristics of the boundary layer, providing a comprehensive framework for evaluating BLH variability and improving multi-sensor retrievals under diverse meteorological conditions.

1. Introduction

The atmospheric boundary layer (ABL) is the transitional interface between the Earth’s surface and the free atmosphere, directly affected by surface friction, turbulent heat flux, and underlying surface properties [1,2]. Within this layer, continuous exchanges of aerosols, momentum, and sensible/latent heat occur between the surface and the free atmosphere, making it the main channel for the transmission of material and energy in the earth–atmosphere system [3]. Among the various parameters describing boundary-layer processes, the boundary layer height (BLH) is particularly important as it characterizes the vertical extent of turbulent mixing and reflects both the intensity of land–atmosphere interactions and the scale of vertical transport. Accurate identification of BLH is essential for improving boundary-layer parameterizations in weather and climate models [4], providing valuable insights into the assessment of air quality and visibility [5,6], assessing wind energy resources [7], and supporting applications such as sustainable urban planning and traffic safety [8,9]. Therefore, understanding and monitoring the temporal and spatial variability of BLH with high resolution is fundamental to exploring land–atmosphere interactions and human-induced effects, carrying significant scientific and societal value in meteorology, climatology, and environmental studies.

Traditionally, BLH measurements have relied primarily on radiosonde (RS) observations. RS balloons, equipped with sensors for temperature, pressure, humidity, and wind, ascend through the atmosphere and provide vertical profiles from which BLH can be retrieved by using classical thermodynamic methods such as the parcel method, bulk Richardson number method, and potential temperature gradient method [10,11,12,13,14,15]. However, their temporal resolution is extremely low, as most operational stations release balloons only twice daily, making them inadequate for capturing the pronounced day–night evolution of BLH, whose variability and detectability can further increase under complex atmospheric conditions. In addition, the horizontal drift of the balloon during ascent can lead to spatial mismatches between the measurement column and the target surface area, introducing representativeness errors, particularly over heterogeneous urban areas or complex terrain [16,17].

With advances in passive remote sensing, the microwave radiometer (MWR) has become an important complementary tool for continuous BLH estimation due to its ability to monitor atmospheric thermodynamic parameters. MWRs receive natural microwave emissions from atmospheric oxygen and water vapor at multiple frequencies to retrieve vertical temperature and humidity profiles. Two main approaches are commonly used: (1) retrieving BLH directly from MWR brightness temperature observations using statistical and neural-network–based retrieval methods [18,19], and (2) thermodynamic determination based on retrieved temperature and humidity profiles. For the convective boundary layer (CBL), the parcel method identifies the height where the virtual potential temperature of an adiabatically lifted surface air parcel equals that of the environment, defining the CBL height [10,11,20,21]. For the stable boundary layer (SBL), the surface-based inversion (SBI) method detects the top of the near-surface inversion layer as the SBL height [10,11,22,23,24]. However, MWRs also have inherent limitations: their vertical resolution decreases with altitude, and precipitation can significantly attenuate microwave radiation, leading to increased uncertainty in BLH detection [25,26,27].

In terms of identifying material boundaries, ground-based aerosol lidars and ceilometers are among the most widely used instruments. These systems emit laser pulses and detect backscattered signals from aerosols, exploiting the strong contrast in aerosol concentration between the ABL and the free troposphere (FT) to locate BLH from the gradient discontinuities of the signal. Based on the backscatter signal profiles, traditional BLH retrieval algorithms can be generally divided into three categories: (1) the gradient method, which determines the BLH at the height of the maximum negative gradient in the signal profile [28,29,30,31]; (2) the threshold method, which identifies the height where the signal decreases to a certain fraction of its maximum value or falls below an empirically defined threshold [32,33,34]; and (3) the wavelet covariance transform (WCT), which detects abrupt variations in the signal by applying multi-scale wavelet transforms [35,36,37,38,39,40]. However, since these methods fundamentally rely on abrupt aerosol optical transitions, they can be severely affected by strong scattering in conditions such as high humidity, low clouds, fog, or multilayer aerosol structures [30,41,42].

Wind profile radar (WPR) determines the BLH from a dynamical perspective by applying the Doppler principle to measure horizontal and vertical wind components, thereby revealing turbulence and wind shear structures within the lower atmosphere. Similar to lidar, BLH can be identified from the radar signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) using gradient or wavelet-based methods [35,43,44,45]. Nevertheless, their low-level measurements are prone to contamination from environmental noise sources such as birds or building reflections, which can distort BLH estimates [46].

With the advancement of active remote sensing technologies, the Doppler wind lidar (DWL) has become a comprehensive tool for ABL studies, enabling BLH retrieval by jointly characterizing aerosol and dynamical structures. The Doppler wind lidar (DWL) derives wind information from the Doppler frequency shift of backscattered laser signals. For BLH retrieval, two types of parameters are particularly relevant: (1) the carrier-to-noise ratio (CNR), which reflects aerosol concentration and thus indicates the material boundary [47,48]; and (2) turbulence-related quantities, such as vertical velocity variance, the turbulent kinetic energy dissipation rate and turbulence spectral power-law exponent, which characterize turbulent mixing intensity and define the dynamical boundary [47,49,50,51,52]. This dual “material–dynamical” observation capability allows the lidar to delineate both the aerosol distribution boundary and the turbulent mixing top, enhancing retrieval reliability under complex atmospheric conditions. However, the reliability of CNR depends on both instrument stability and environmental conditions, the lidar backscattered signal can become anomalous or distorted, introducing uncertainties in BLH detection [47,53]. Moreover, while vertical velocity variance offers a direct measure of turbulent mixing, the threshold selection is highly empirical and varies across weather regimes and locations, lacking a unified standard and complicating inter-study comparisons [54]. Therefore, despite the multi-parameter advantages of DWL, its physical consistency (i.e., the correspondence between material and dynamical boundaries)—often obscured in previous cross-instrument comparisons (e.g., aerosol lidar vs. Doppler wind lidar) by sampling and retrieval differences [50]—and parameter sensitivity under complex weather conditions require systematic evaluation to enhance algorithmic generality. In addition, comparative analyses between DWL and MWR derived retrievals are necessary to further validate and refine the reliability of BLH estimations.

To address these issues, this study integrates observations from a DWL and a MWR at the Beijing Nanjiao Observatory to jointly retrieve and compare three physically distinct types of boundary layer heights. For the lidar, the wavelet transform method based on CNR is used to identify aerosol-layer discontinuities representing the material boundary layer height, while the variance method determines the upper limit of turbulent mixing corresponding to the dynamical boundary layer height. For the MWR, the parcel and inversion methods are applied to derive thermodynamic boundary layer heights, with ERA5 reanalysis and radiosonde data used for comparison. By simultaneously identifying material, dynamical, and thermodynamic BLHs from DWL and MWR, we evaluate each instrument’s retrieval capability, examine their performance under different weather conditions (clear, cloudy, and hazy days), and explore their physical correspondence. The results aim to provide a physically consistent reference framework for future multi-sensor fusion retrievals and model validation of boundary layer processes.

2. Instruments and Data

In this study, three remote-sensing instruments—a Doppler wind lidar (DWL; Shenzhen Dashun Laser Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China), a microwave radiometer (MWR; Hangzhou Qianhai Technology Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China), and a radiosonde (RS; Nanjing Daqiao Machine Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China)—were employed at the Beijing Nanjiao Meteorological Observatory, Beijing, China (station number: 54511; 39.8°N, 116.47°E) to conduct joint observations and retrieval analyses of the atmospheric boundary layer (ABL) structure and its evolution from 16 October to 31 December 2023. After removing data gaps caused by precipitation and instrument maintenance, a total of 50 days of valid simultaneous observations were obtained, providing a reliable basis for the retrieval and validation of BLH. All data processing and statistical analyses were performed using MATLAB (R2021b).

2.1. Doppler Wind Lidar

The Doppler wind lidar used in this study operates at a wavelength of 1.5 μm and employs the Doppler Beam Swinging (DBS) technique. Its fundamental principle is to measure the Doppler frequency shift of the backscattered signal from aerosol particles to obtain radial wind velocities in multiple directions. By combining measurements from four azimuthal beams and one vertical beam, three-dimensional wind field information—including horizontal wind speed, vertical velocity, and wind direction—is retrieved. The system provides a temporal resolution of 7–8 s and a vertical resolution of approximately 30 m, with a maximum detection height of about 4 km under favorable atmospheric conditions. The output data include parameters such as horizontal wind speed, vertical velocity, wind direction, and CNR. The Doppler wind lidar data were screened by the manufacturer using a CNR threshold (CNR < −32 dB) to exclude low-signal measurements.

2.2. Microwave Radiometer

The MWR passively receives natural microwave emissions from the atmosphere at multiple frequencies to retrieve vertical profiles of temperature and humidity. The MWR (Hangzhou Qianhai Technology Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China) is equipped with two receivers: a K-band receiver (22–32 GHz) for detecting water-vapor radiation to derive humidity profiles, and a V-band receiver (51–59 GHz) for detecting oxygen radiation to retrieve temperature profiles. The MWR provides temperature, relative humidity, and absolute humidity profiles every two minutes, covering an altitude range of approximately 10 km. Since the vertical resolution of MWR observations is relatively coarse, the retrieved temperature and humidity profiles were interpolated to 10 m intervals in this study to better capture fine-scale variations in BLH. The retrieved temperature and humidity profiles were quality-controlled by the manufacturer using climatological range checks, logic checks, and internal consistency checks, jointly screening out outliers and nonphysical records and enforcing physical consistency of the profile data.

2.3. Radiosonde

The radiosonde system used at the observation site is the GTS11 digital sounding system, which measures meteorological variables such as temperature, pressure, relative humidity, and horizontal wind components. The wind field parameters are derived from the L-band GFE(L)-1 secondary radar, which continuously tracks the azimuth, elevation, and range of the balloon during its ascent to calculate wind speed and direction. This setup provides horizontal wind profiles with a temporal resolution of 1 s. During the experimental period, radiosondes were launched twice daily at 07:15 and 19:15 local time.

All the above instrument data have undergone strict quality control by the manufacturers. Therefore, no additional screening was applied in this study. The main performance parameters of the instruments are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Main information of all the instruments.

2.4. ERA5

This study employed the ERA5 reanalysis dataset released in 2017 by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF). ERA5 is the fifth-generation global atmospheric reanalysis product developed by ECMWF. It is produced using a four-dimensional variational (4D-Var) data assimilation system that integrates multi-source satellite, surface, and radiosonde observations to provide a globally continuous and physically consistent meteorological field. The ERA5 dataset has a temporal resolution of 1 h, a horizontal resolution of 0.25° × 0.25°, and 137 vertical levels extending from the surface to 0.01 hPa. Because of its high temporal and spatial continuity and the consistency between observations and model simulations, ERA5 has been widely used in regional studies of boundary-layer height (BLH) characteristics [11,55,56]. In this study, as radiosonde observations were available only at 07:15 and 19:15 local time (LST), with no measurements around midday, the hourly BLH data from ERA5 were employed to supplement and validate the results derived from the DWL and MWR. Since ERA5 assimilates global radiosonde observations, including those used in this study, its profiles at 07:15 and 19:15 LST may partially incorporate the corresponding radiosonde information. Nevertheless, owing to its high temporal and spatial continuity, the ERA5 data remains valuable for providing a consistent background for the analysis.

2.5. PM2.5 Data

The PM2.5 concentration data used in this study were obtained from the Beijing Municipal Ecological and Environmental Monitoring Center (BJMEMC). The BJMEMC has established a comprehensive air quality monitoring network across Beijing, consisting of 35 ground-based stations that provide hourly measurements of major pollutants, including PM2.5, PM10, SO2, NO2, O3, and CO. In this study, the Daxing Jiugong station (39.78°N, 116.47°E), which is the closest site to the meteorological observatory, was selected as a representative location for acquiring hourly PM2.5 concentration data. These data were used to supplement information on air pollution conditions and to support the analysis of BLH variations and their environmental responses under different weather types.

3. Methods

3.1. Haar Wavelet Covariance Transform Method

The DWL can be used to obtain aerosol backscatter profiles for ABL studies. Within the ABL, aerosols are well mixed by surface turbulence, resulting in relatively high and uniform concentrations, whereas in the free atmosphere above, aerosol concentrations drop sharply to much lower levels. This contrast leads to a distinct discontinuity in the lidar return signal—either in backscatter intensity or CNR—at the height of the boundary-layer top. The Haar wavelet covariance transform (HWCT) method identifies the BLH based on this vertical discontinuity. By applying mathematical operations to enhance the signal gradient at the layer top, the method highlights the height of the sharp transition in the backscatter profile. The Haar wavelet function is defined as [36]:

where is the scale parameter controlling the degree of smoothing of the wavelet function, and is the translation parameter corresponding to each detection height of the lidar. The covariance transform of the Haar wavelet function is then applied as follows:

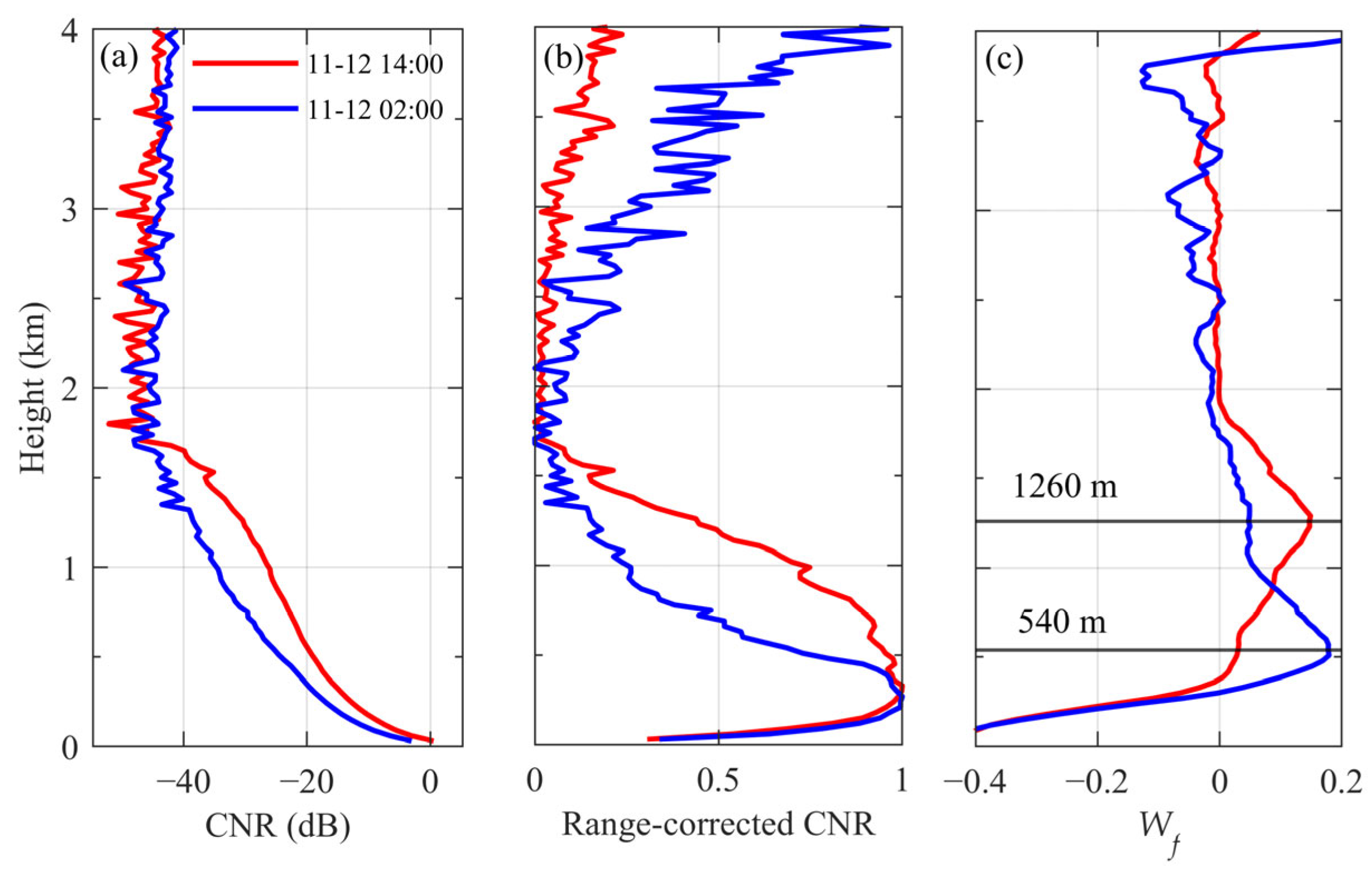

where and denote the selected lower and upper limits of the lidar detection range, respectively. represents the range-squared-corrected and normalized CNR, and is the resulting wavelet covariance coefficient. Based on comparative tests with different values and considering the range resolution of the Doppler wind lidar used in this study, a value of = 450 m was adopted. The height corresponding to the maximum value of is identified as the BLH (Figure 1c).

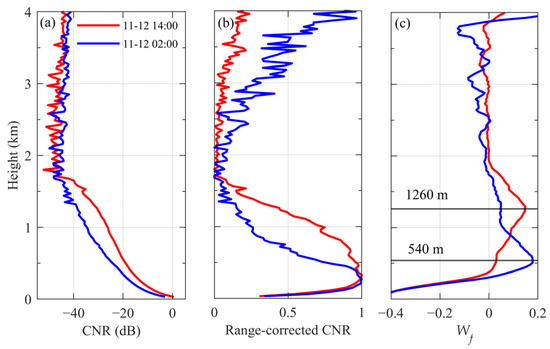

Figure 1.

Doppler wind lidar observations at 14:00 (red) and 02:00 (blue) on 12 November 2023: (a) CNR (dB); (b) range-corrected CNR after normalization; and (c) wavelet covariance coefficient . The black solid lines indicate the height of the local maxima of , corresponding to the retrieved BLHs.

At certain times, the presence of high clouds causes the wavelet covariance coefficient to exhibit pronounced negative minima near the cloud base. Therefore, before determining the BLH, the cloud base height (CBH) must first be identified. When falls below −0.1, the corresponding height is defined as the CBH, and the subsequent search for the BLH maximum is restricted to levels below the CBH.

3.2. Variance Method

In addition to the HWCT approach, the BLH can also be inferred from the vertical velocity variance obtained by the DWL. This method exploits the characteristic vertical structure of turbulence: within the CBL, strong turbulent mixing produces large fluctuations in vertical velocity, leading to high variance values, whereas above the boundary layer, turbulence intensity decreases rapidly and the variance drops sharply. By examining the vertical profile of the variance and applying an appropriate threshold, the upper limit of turbulent mixing, which represents the BLH, can be determined.

Let denote the vertical velocity observed at height z and time t within a 1 min averaging window. The vertical velocity variance at height z is then defined as:

where N is the number of samples within the 1 min averaging window, and denotes the mean vertical velocity. The variance of vertical velocity , represents the turbulent kinetic energy in the vertical direction and reflects the intensity of turbulent motion within the boundary layer. Empirical threshold values commonly range between 0.04 and 0.1 m2 s−2 [49,50,57,58], but the specific threshold depends on local atmospheric conditions and site characteristics. In this study, a threshold of 0.06 m2 s−2 was adopted to determine the BLH for clear-sky conditions, while 0.01 m2 s−2 was used for cloudy and hazy conditions, and the was averaged to a 10 min temporal resolution to reduce short-term fluctuations.

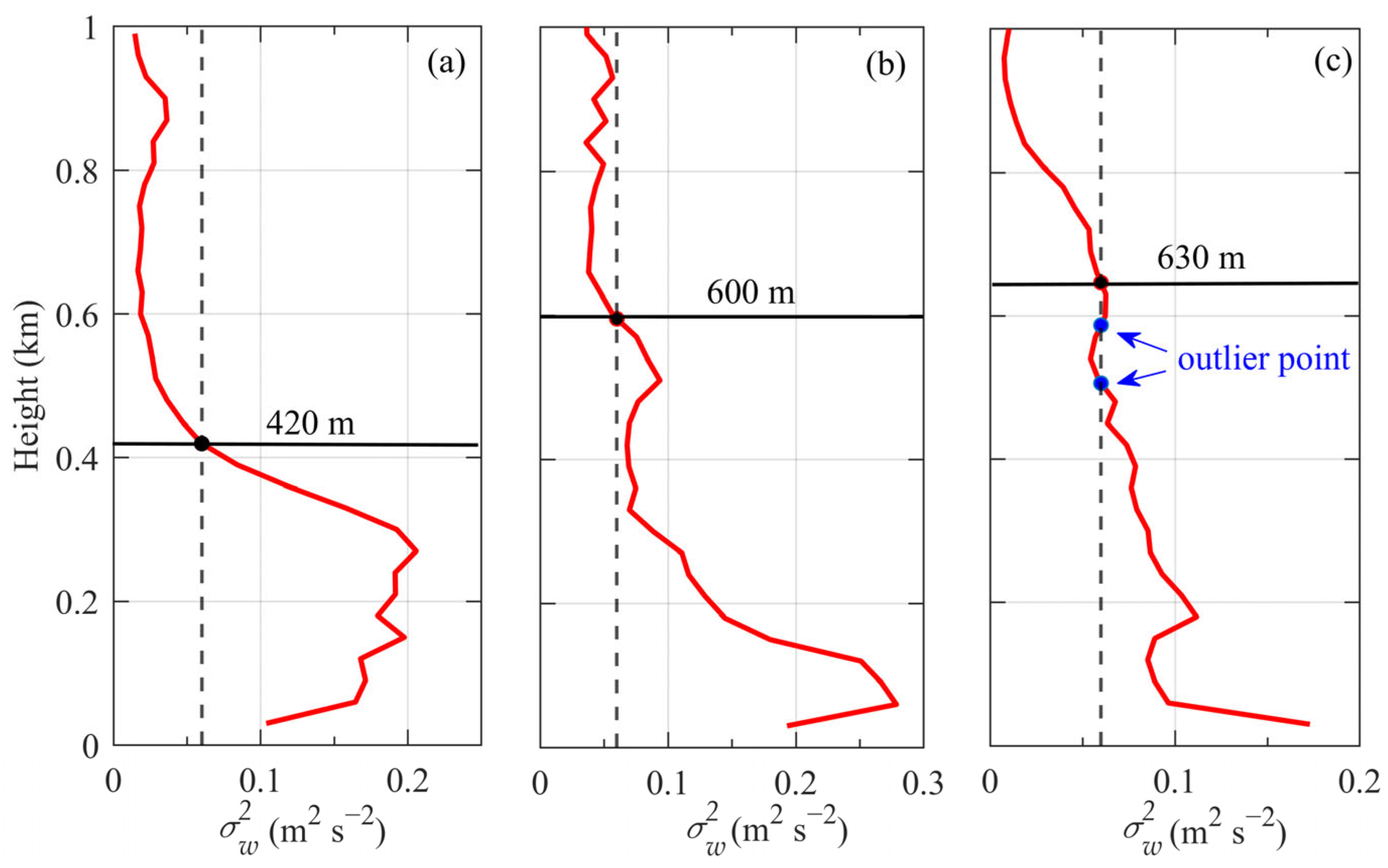

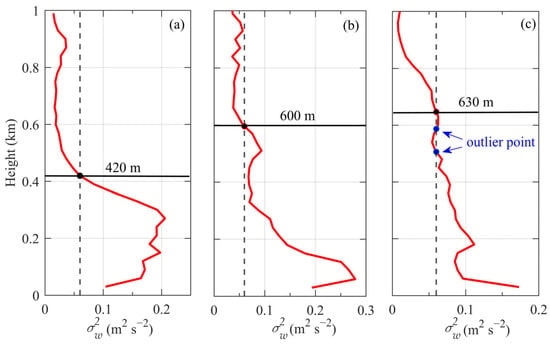

As shown in Figure 2a,b, the generally decreases with height, and the height where it first falls below the threshold is identified as the BLH. However, during certain periods, enhanced turbulent activity near the top of the boundary layer can cause multiple fluctuations of the variance around the threshold, resulting in several intersections with the threshold line (Figure 2c). To avoid misidentification caused by such fluctuations, the median method [47,59] was applied to remove abnormal points. Specifically, (1) all heights where is below the threshold are first selected; (2) then the median among these selected heights is calculated; (3) the final BLH is then determined as the highest level below the median where is greater than or equal to the threshold.

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of BLH retrieval using the variance method at (a) 08:00 on 18 October 2023, (b) 14:00 on 17 December 2023, and (c) 14:00 on 14 November 2023. The red solid lines represent the vertical profiles of vertical velocity variance , and the black dashed lines denote the threshold value (0.06 m2 s−2). Black dots indicate the heights where falls below the threshold, and the black solid lines mark the identified BLHs. Blue dots show the outliers removed by the median method. Panels (a,b) correspond to typical cases with smooth variance profiles and well-defined stratification, while panel (c) illustrates an example affected by local anomalies.

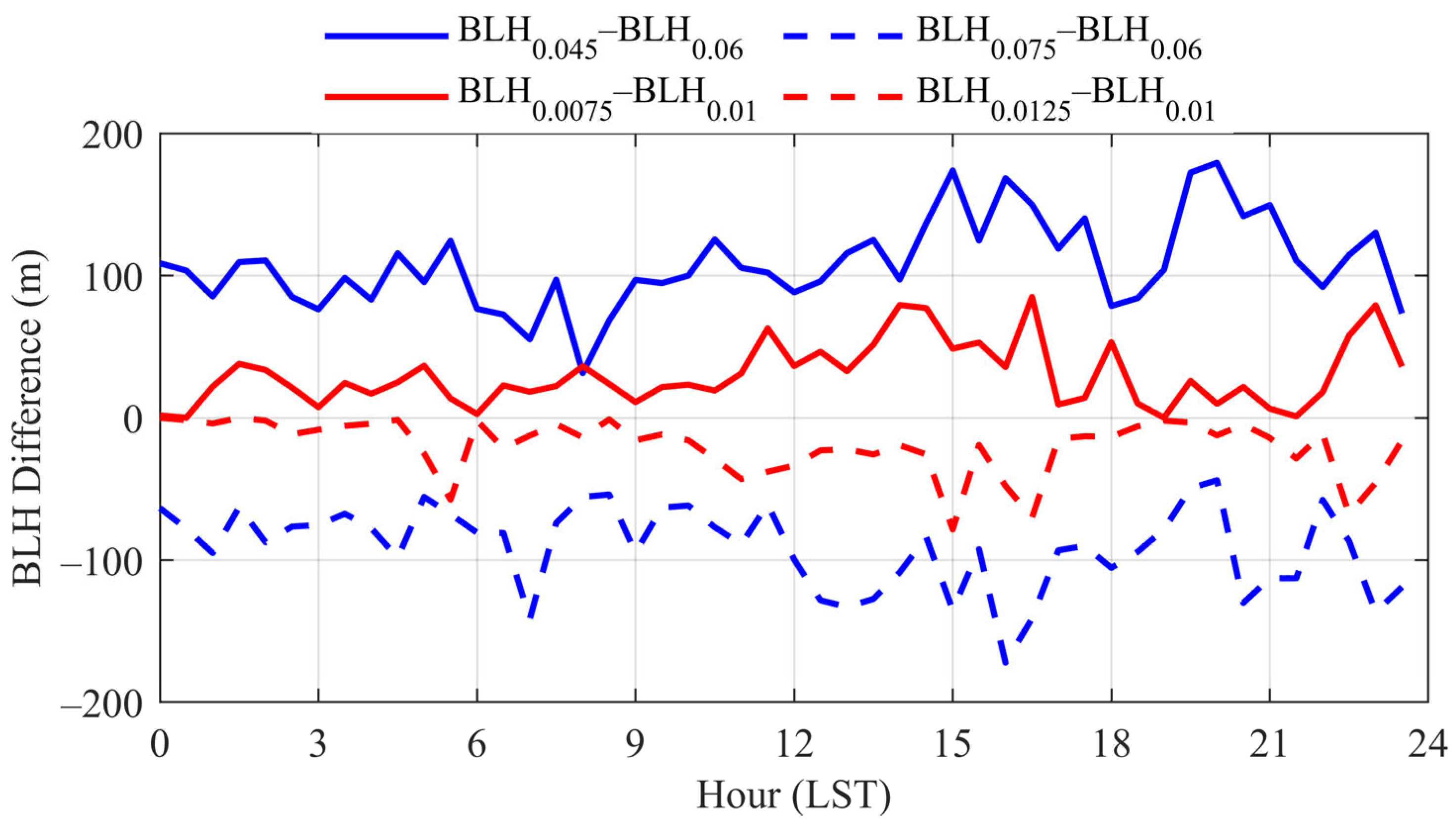

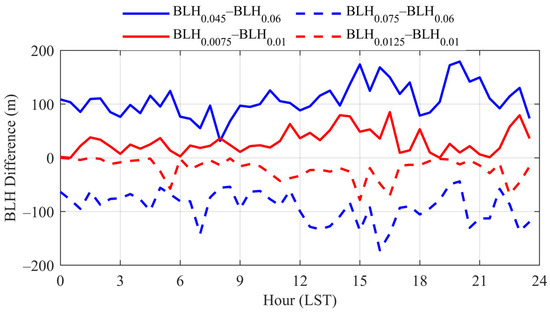

To verify the validity of the selected thresholds, we conducted a threshold sensitivity analysis to assess their impact on BLH retrieval under different weather conditions. We tested the robustness of the thresholds by varying them within a ±25% range for both clear-sky and cloudy/hazy days. Figure 3 shows the BLH differences under these conditions, with the vertical axis representing the average change in PBLH for each half-hour under different threshold settings. The solid and dashed lines in the figure represent the differences between adjacent thresholds, providing a clear comparison of how each threshold affects PBLH retrieval. Under clear-sky conditions, the differences between 0.045 m2 s−2 and 0.06 m2 s−2, as well as between 0.06 m2 s−2 and 0.075 m2 s−2, show a consistent pattern, demonstrating that the 0.06 m2/s2 threshold provides stable BLH retrieval results. Similarly, for cloudy and hazy conditions, the differences between 0.0075 m2/s2 and 0.01 m2 s−2, as well as between 0.01 m2 s−2 and 0.0125 m2 s−2, show relatively smaller fluctuations, with differences ranging from −100 m to 100 m, indicating that the 0.01 m2 s−2 threshold is equally stable and effective. Overall, the minimal variations observed in BLH differences across different weather conditions suggest that the chosen thresholds—0.06 m2 s−2 for clear-sky conditions and 0.01 m2 s−2 for cloudy/hazy conditions—are robust and provide consistent results. The variations in thresholds within the ±25% range did not lead to significant changes in the retrieval results, further confirming the suitability of the selected thresholds for BLH assessment.

Figure 3.

Diurnal sensitivity of BLH to threshold perturbations under clear-sky and cloudy/hazy conditions. BLHx denotes the boundary-layer height retrieved using a variance threshold of x m2 s−2, with thresholds perturbed by ±25% around the baseline values (0.06 m2 s−2 for clear-sky and 0.01 m2 s−2 for cloudy/hazy conditions). Blue (red) curves show clear-sky (cloudy/hazy) differences relative to 0.06 (0.01) m2 s−2.

3.3. Parcel Method

The parcel method determines the BLH based on the principle of buoyancy equilibrium [60,61]. It assumes that a surface air parcel, heated by solar radiation, rises adiabatically within the boundary layer. As the environmental virtual potential temperature increases rapidly near the top of the boundary layer, the height where the parcel’s virtual potential temperature equals the surface value marks the level of neutral buoyancy and is defined as the BLH. This method intuitively reflects the thermal structure and is suitable for identifying the mixing boundary layer.

Under the hydrostatic equilibrium assumption, the air pressure at height z2 can be calculated from the surface reference pressure p1 and height z1 as follows:

where is the gravitational acceleration, taken as 9.8 m·s−2; is the specific gas constant for dry air, taken as 287.15 J·kg−1·K−1; and denotes the mean temperature between heights and . The potential temperature is then calculated as

where p0 is the reference pressure of 1000 hPa, and is the specific heat capacity at constant pressure, taken as 1004 J·kg−1·K−1.

Combining the absolute humidity , the water vapor pressure can then be obtained as

where is the specific gas constant for dry air, taken as 461 J·kg−1·K−1.

Then, the specific humidity q is then calculated as

and, finally, the virtual potential temperature profile is obtained:

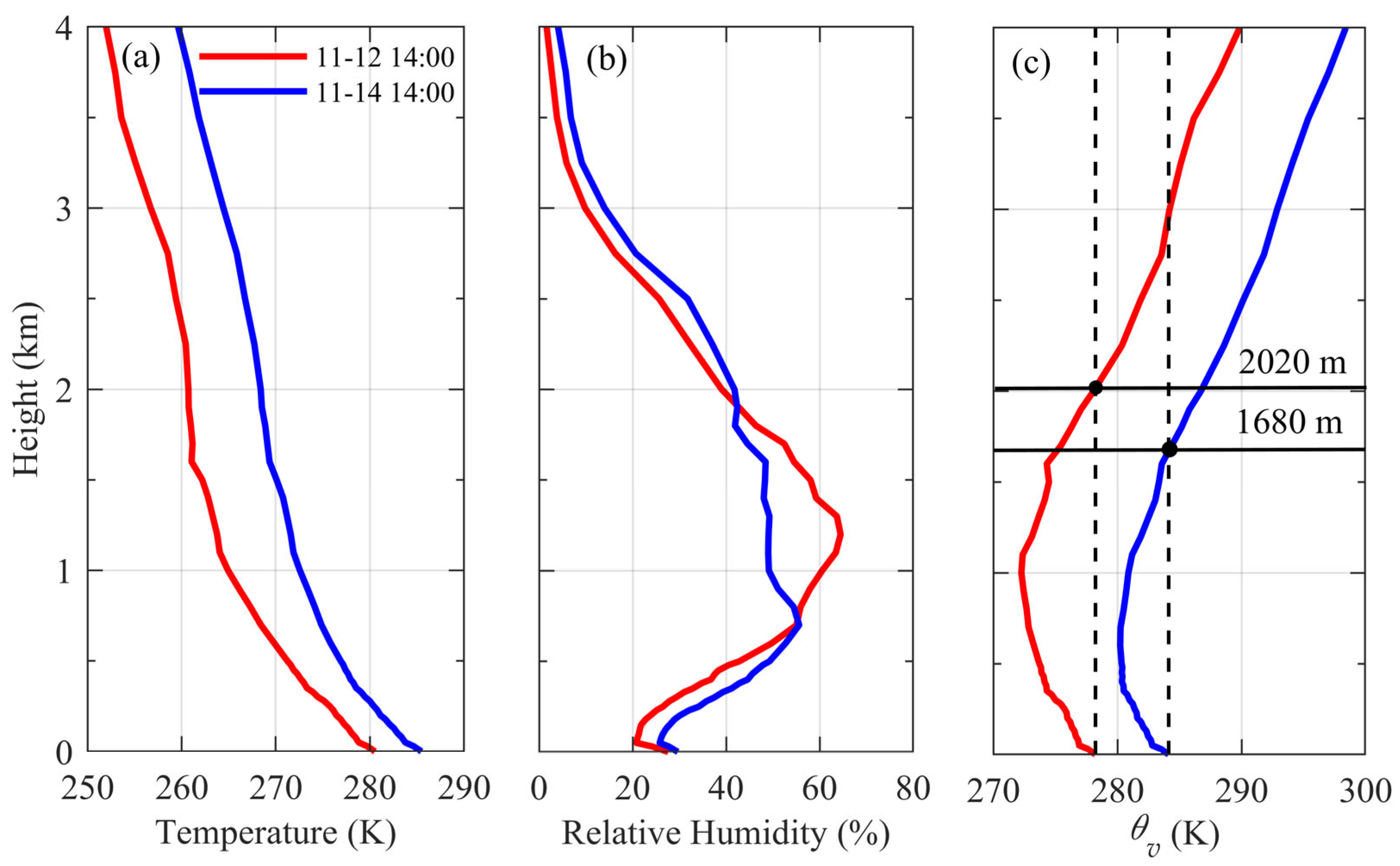

and the height at which the environmental virtual potential temperature first reaches or exceeds the surface virtual potential temperature is identified as the BLH (Figure 4c).

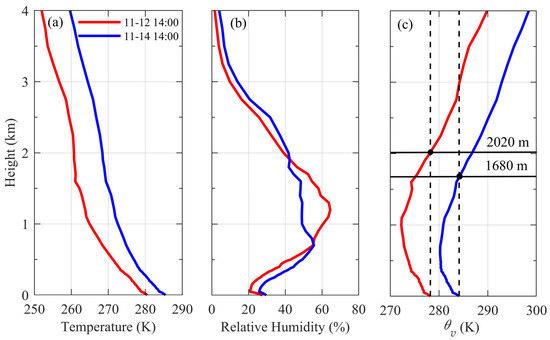

Figure 4.

Schematic illustration of BLH retrieval using the parcel method at 14:00 on 12 November 2023 (red) and 14:00 on 14 November 2023 (blue): (a) temperature profiles; (b) relative humidity profiles; (c) virtual potential temperature profiles. The black dashed line indicates the surface virtual potential temperature , while the red and blue solid lines represent the profiles at the corresponding times. The black dots mark the levels where θv equals θvs, and the black solid lines denote the identified BLHs.

3.4. Surface-Based Inversion Method

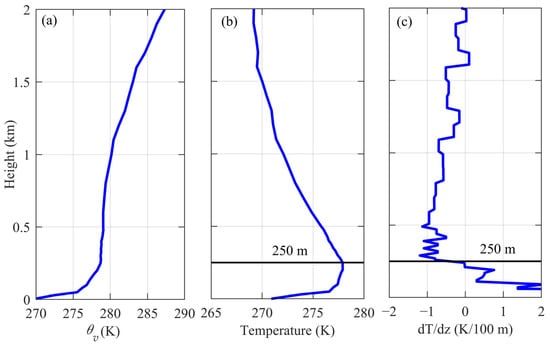

Compared with daytime conditions, the nighttime boundary layer is much shallower—typically only several tens to a few hundred meters—because surface longwave cooling suppresses turbulent mixing, and this leads to the formation of a stable boundary layer (SBL). Under such conditions, the parcel method based on buoyancy equilibrium becomes less applicable (Figure 5a). The resulting temperature inversion, caused by rapid surface cooling, can be clearly captured by the MWR. In the surface-based inversion (SBI) method, a temperature inversion is identified where a continuous positive temperature gradient exists near the surface (dT/dz > 0), and the top of this inversion is defined as the BLH (Figure 5b,c).

Figure 5.

Schematic illustration of BLH retrieval using the Surface-Based Inversion (SBI) method at 04:00 on 14 November 2023: (a) virtual potential temperature profile; (b) temperature profile; (c) temperature-gradient profile. The black solid line indicates the boundary-layer height determined by the SBI method.

3.5. Improved Potential Temperature Gradient Method

The thermal structure of the atmospheric boundary layer determines its turbulent mixing characteristics, and potential temperature is a key thermodynamic variable that reflects atmospheric stability. The improved potential temperature gradient method [12] has been demonstrated to be one of the most accurate approaches for retrieving BLH from radiosonde data [62]. In this study, the potential temperature profile is first calculated from radiosonde observations. Then the data is resampled with respect to pressure, assuming that the first measurement of each sounding corresponds to the surface pressure. Subsequent profiles were interpolated at uniform pressure intervals of −5 hPa to obtain evenly spaced pressure levels. Subsequently, the type of the boundary layer was determined from the potential temperature differences between near-surface pressure levels, which were classified into three categories: the CBL, SBL, and the neutral boundary layer (NBL):

where and denote the potential temperatures at −5 hPa and −20 hPa relative to the surface pressure, respectively.

For the CBL and NBL, the height is first identified as the level that satisfies the following condition:

where is the potential temperature at the surface, and is the potential temperature at height . Above , the BLH is identified where it first satisfies the following condition:

hence, the height is defined as the BLH.

For the SBL, when it satisfies

or

the height is defined as the BLH.

When turbulence is dominated by wind shear, the BLH is determined by the level of the first wind-speed maximum below 1.5 km, where the wind speed exceeds 2 m s−1. By comparing the heights obtained from the potential temperature gradient and the wind speed criteria, the lower of the two is taken as the BLH.

3.6. Richardson Number Method

The Richardson number method is based on the balance of turbulent kinetic energy, where the relative effects of buoyant suppression and shear production determine the upper limit of turbulent mixing. In this study, the bulk Richardson number is adopted, defined as follows [63]:

where is the gravitational acceleration; and are the virtual potential temperatures at height and at the surface, respectively; and denote the horizontal wind components, while and represent their surface values; and is the surface elevation. When increases to the critical value of 0.25, and the corresponding height is identified as the BLH.

4. Results

4.1. Correlation Analysis of BLH Retrieved from DWL and MWR Methods

To ensure the physical comparability of the three BLH retrieval methods, this analysis focuses on the daytime convective period (09:00–17:00 LST), when turbulent mixing is fully developed. Under nocturnal stable conditions, turbulence intensity is considerably reduced, leading to lower reliability of the variance method in identifying the upper limit of turbulent mixing. Meanwhile, the parcel method, which relies on the buoyancy equilibrium assumption, is influenced by the formation of temperature inversions and therefore exhibits limited applicability at night. In addition, in a few cases when the boundary layer was not yet well developed at the nominal start time, the selected time window was slightly adjusted to ensure that the analyzed period corresponded to the convective phase. To minimize uncertainty and highlight method performance under convective conditions, only daytime samples were used for statistical analysis, with 10 min averaging applied to suppress short-term fluctuations. After excluding rainy days and instrument-maintenance periods, a total of 1953 matched samples were used for intercomparison. BLHs were retrieved using the Haar wavelet covariance transform (DWL_HWCT), the variance method (DWL_Var), and the parcel method (MWR_Parcel), followed by pairwise comparison among the three approaches.

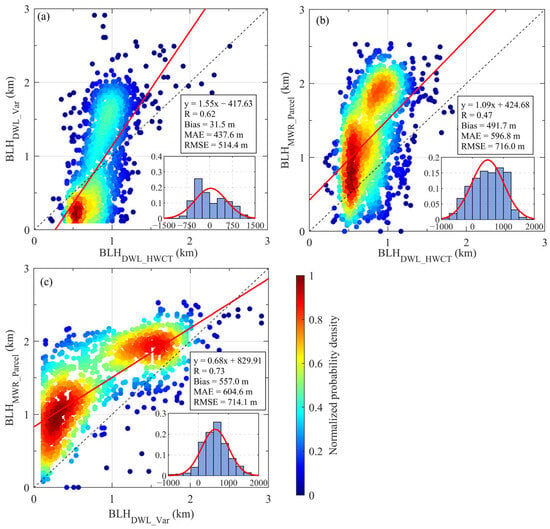

Figure 6a–c present scatterplots of BLHs retrieved from the three method pairs together with the corresponding error frequency histograms. Figure 6a shows the relationship between and , yielding a regression equation of y = 1.55x − 417.63 with a correlation coefficient R = 0.62, a mean bias (Bias) of 31.5 m, a mean absolute error (MAE) of 437.6 m, and a root-mean-square error (RMSE) of 514.4 m. These results indicate a relatively high overall consistency between the two lidar-based methods, particularly during periods of strong convection. Figure 6b compares with , showing a moderate correlation (R = 0.47) and a regression equation of y = 1.09x + 424.68. The results exhibit a systematic positive bias, with Bias = 491.7 m, MAE = 596.8 m, and RMSE = 716.0 m, suggesting that the thermodynamic criterion generally yields higher BLHs than the aerosol-based approach. Figure 6c illustrates the comparison between and , where the strongest correlation is observed (R = 0.73). The regression equation (y = 0.68x + 829.91) and associated statistics (Bias = 557 m, MAE = 604.6 m, RMSE = 714.1 m) suggest that both methods exhibit similar diurnal evolution patterns of the convective boundary layer, although the parcel method tends to overestimate BLH.

Figure 6.

Correlation analysis of three BLH retrieval methods during daytime hours (09:00–17:00 LST): (a) variance method (DWL_Var) vs. Haar wavelet covariance transform (DWL_HWCT); (b) parcel method (MWR_Parcel) vs. DWL_HWCT; (c) MWR_Parcel vs. DWL_Var. The color of the scatter points represents the normalized probability density. The red line denotes the linear regression fit, and the black dashed line indicates the 1:1 reference. The regression equation, correlation coefficient (R), mean bias (Bias), mean absolute error (MAE), and root-mean-square error (RMSE) are also shown in each panel. The inset in the lower right corner of each plot presents the frequency histogram of retrieval differences, with the red line indicating the fitted curve.

Despite the 10 min averaging effectively reducing instantaneous fluctuations, discrepancies remain due to the different physical sensitivities of each method. Overall, BLHs derived from the Doppler lidar (both HWCT and variance methods) are obviously lower than those from the MWR. The HWCT method is highly sensitive to variations in aerosol concentration and humidity, making it most responsive to material discontinuities within the ABL. The variance method directly reflects turbulence intensity and energy exchange, thereby capturing the dynamical boundary. In contrast, the parcel method describes thermodynamic stability and stratification evolution. These three approaches, representing material, dynamical, and thermodynamic perspectives, complement each other and collectively depict the diurnal evolution of the convective boundary layer. This also highlights that relying on a single method may not adequately describe the true BLH. Based on these findings, three representative cases—clear-sky, cloudy, and haze conditions—are analyzed in subsequent sections to further investigate the mechanisms governing boundary-layer structure under different meteorological regimes. Additionally, results from the three retrieval methods are compared with BLHs derived from ERA5 reanalysis and radiosonde observations, with nighttime estimates supplemented by MWR_SBI retrievals.

4.2. Case Studies

4.2.1. Case 1: Clear-Sky Days

Surface observations indicate that weather conditions at the site remained clear on 20–21 October 2023, with abundant solar radiation during the day and no significant cloud systems or precipitation at night. The surface temperature ranged from 18 °C to 5 °C on 20 October, and from 22 °C to 6 °C on 21 October., while near-surface winds were generally weak, shifting from northwesterly on the 20th to southerly on the 21st. During this period, PM2.5 concentrations remained below approximately 35 µg m−3 (Figure 7h) and exhibited a clear diurnal variation, with lower concentrations during daytime mixing and higher values after sunset, indicating favorable atmospheric dispersion conditions.

Figure 7.

Multi-source observational profiles under clear-sky conditions at the observation site on 20–21 October 2023: (a) CNR; (b) ; (c) virtual potential temperature ; (d) temperature; (e) horizontal wind speed; (f) vertical wind speed; (g) wind direction; and (h) relative humidity and PM2.5 concentration. The green, pink, and orange lines represent BLHs retrieved from HWCT method, variance method, and parcel method, respectively, while the gray solid line denotes the nighttime stable-layer height obtained from SBI method. The triangles and pentagrams indicate BLHs derived from improved potential temperature gradient method and Richardson number method, respectively. The black dashed line shows the BLH from ERA5 data, the purple solid line indicates PM2.5 concentration (corresponding to the right y-axis in panel (h)), and the red dashed lines mark sunrise and sunset times.

Under such persistent clear-sky conditions, the BLHs retrieved from the three methods (, and ) all exhibited pronounced diurnal variations.

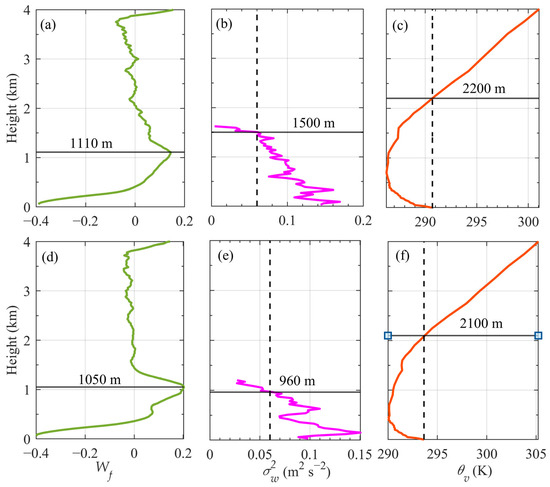

As shown in Figure 7a, began to rise steadily after 08:30 LST on 20 October, reaching a maximum of 1110 m at 14:00 and then decreasing rapidly after sunset, representing the aerosol-defined boundary layer. Figure 7b shows that prior to 08:10, remained low, and could not be identified. As surface heating strengthened after sunrise, turbulent mixing gradually intensified, rose sharply after 08:30, peaking at 1500 m around 14:00 (Figure 7b and Figure 8b). However, between 09:50 and 14:00, noticeable fluctuations occurred, reflecting the short-term variability and instability of the variance-based BLH. Figure 7c indicates that , derived from the virtual potential temperature profiles, was consistently higher than the lidar-based results. This method became effective shortly after sunrise (07:36 LST) and increased rapidly, reaching its peak of 2240 m at 14:04, then gradually declined after 16:00 As illustrated in Figure 7a–c and Figure 8, exceeded and by about 1000 m on average during the afternoon, whereas the two lidar-derived BLHs agreed well with each other. This demonstrates that, under clear-sky midday conditions, the thermodynamic boundary layer retrieved from the MWR was substantially higher than the material and dynamical boundaries derived from the DWL, which showed strong internal consistency.

Figure 8.

Comparison of vertical profiles derived from the DWL and the MWR at 14:00 LST on 20 October 2023 and 12:30 LST on 21 October 2023. (a–c) Profiles on 20 October; (d–f) profiles on 21 October. (a,d) Haar wavelet covariance coefficients ; (b,e) vertical velocity variance , where the black dashed line indicates the threshold of 0.06 m2 s−2; (c,f) virtual potential temperature , where the black dashed line represents the surface virtual potential temperature . The black solid lines denote the BLHs determined from each method.

Between 00:00 and 06:30 LST on 20 October, both the variance and the parcel method still provided BLH estimates (Figure 7b,c). The field (Figure 7b) revealed residual turbulent activity below 1 km, indicating that the nocturnal mixed layer had not completely dissipated. In addition, , and were all distinctly higher than the stable-layer top determined from the inversion depth.

Compared with 20 October, the development of the boundary layer on 21 October was noticeably delayed (Figure 7a–c), and the period of elevated BLH was substantially shorter, followed by a rapid decay before sunset. This indicates that, although 21 October also experienced clear-sky conditions, a stronger morning inversion (approximately 260 m) effectively suppressed the onset of convection (Figure 7c,d), resulting in a delayed boundary-layer growth. During the afternoon, the weakening of solar heating and the associated decay of turbulence led to a subsequent decrease in BLH. Overall, the diurnal evolution of the boundary layer on 21 October was characterized by a delayed onset, rapid growth, and a swift decay, suggesting that even under consecutive clear-sky conditions, minor variations in surface radiative balance or thermal stratification can exert a pronounced influence on boundary-layer evolution.

Moreover, at 07:15 and 19:15 each day, showed good agreement with the BLHs derived from RS methods, i.e., and , with both representing the near-surface stable layer. In contrast, was significantly higher than those derived from the MWR and RS (Table 2), likely because at night the maximum gradient in the wavelet covariance corresponds to the top of the residual aerosol layer rather than the actual stable boundary layer height [36,64]. Moreover, on 20 October, the BLH from ERA5 was considerably higher than those derived from the HWCT and variance methods but was comparable to that from the parcel method. In contrast, on 21 October, showed good agreement with and , while being lower than by more than 1 km at its maximum. The parcel method is mainly applicable to a well-developed daytime convective mixed layer, where a lifted surface parcel becomes neutrally buoyant at the mixed-layer top. In Table 2 (07:15 and 19:15 LST), the boundary layer was typically in a stable regime, and the MWR-derived increased monotonically from the surface. Therefore, the parcel method gives no valid BLH result at these four moments even under clear-sky conditions.

Table 2.

Comparison of BLHs retrieved by different methods at 07:15 and 19:15 LST on 20–21 October 2023 at 54511 Station.

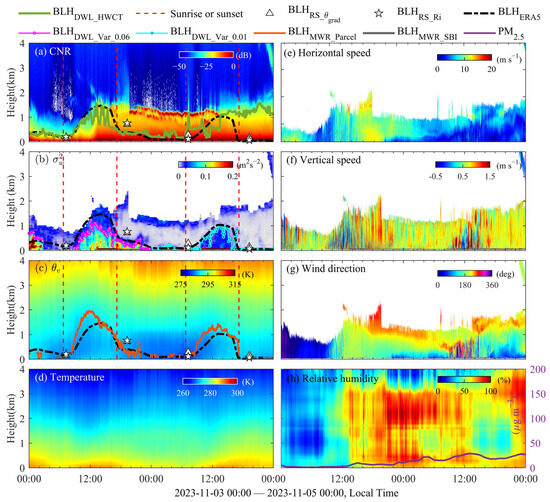

4.2.2. Case 2: Cloudy Days

During 3–4 November 2023, the experimental site experienced mostly cloudy and overcast conditions, with intermittent light rain occurring on the afternoon of 4 November. The surface temperature varied between 6 °C and 17 °C on 3 November and between 10 °C and 16 °C on 4 November, indicating a relatively small diurnal variation. The PM2.5 concentration remained below approximately 30 μg m−3, while the CNR field exhibited a pronounced, continuous high-intensity band (Figure 9a), reflecting the influence of cloud development on all BLH retrieval methods.

Figure 9.

Multi-source observational profiles under cloudy conditions at the observation site on 03–04 November 2023: (a) CNR; (b) ; (c) virtual potential temperature ; (d) temperature; (e) horizontal wind speed; (f) vertical wind speed; (g) wind direction; (h) relative humidity and PM2.5 concentration. The green, pink, blue, and orange solid lines represent BLHs retrieved from HWCT method, variance method with thresholds of 0.06 m2 s−2 and 0.01 m2 s−2, and parcel method, respectively. The gray solid line denotes the nighttime stable-layer height obtained from the SBI method. The triangles and pentagrams indicate BLHs derived from improved potential temperature gradient method and Richardson number method, respectively. The black dashed line shows the BLH from ERA5 data, the purple solid line indicates PM2.5 concentration (corresponding to the right y-axis in panel (h)), and the red dashed lines mark sunrise and sunset times.

On 3 November, during the morning period (09:00–12:00 LST), the sky was mostly clear with strong aerosol backscatter and active turbulence, and the three retrieval methods showed good consistency. After 10:00 LST, turbulence intensified (Figure 9b), with (threshold of 0.06 m2 s−2) and increasing simultaneously, while rose even more rapidly. After 13:00 LST, the increasing cloud cover led to intermittent enhancements in CNR at around 1.2 km height, corresponding to the passage of shallow cumulus clouds (Figure 9a). The then fluctuated strongly between 0.8 and 1.8 km (Figure 9a), as cloud scattering interfered with the CNR signal. Meanwhile, and slightly decreased due to reduced shortwave radiation (Figure 9b,c), indicating that low clouds suppressed both dynamical and thermal boundary-layer development.

Between 20:00 LST on 3 November and 14:00 LST on 4 November, a persistent high-reflectivity layer near 1.6 km was observed (Figure 9a), suggesting the presence of continuous low-level clouds. Because the HWCT method detects the BLH based on abrupt CNR gradients that trace aerosol stratification, the strong backscatter from cloud droplets masked the underlying aerosol signal, leading to multiple false peaks and severe underestimation of the true BLH. In this period, no longer represented the actual boundary-layer height but instead indicated the optical discontinuity caused by cloud droplets.

From sunrise to sunset on 4 November, low-level cloud cover further weakened turbulence (Figure 9b). The variance method with the original threshold of 0.06 m2 s−2 failed to capture the shallow mixing layer. After adjusting the threshold to 0.01 m2 s−2, successfully depicted the diurnal evolution of the shallow dynamical boundary layer (Figure 9b and Figure 10e), reaching a maximum of 990 m at 13:20 LST. The adjusted also exhibited improved agreement with . Meanwhile, remained at relatively low levels, peaking at 1440 m around 13:20 LST. After 14:00 LST, the dissipation of clouds (Figure 9a) caused to rise abruptly above 1 km (Figure 9a and Figure 10d) and remain elevated throughout the night. The CNR field below 1 km stayed near −15 dB, suggesting that the aerosol distribution remained affected by residual cloud droplets.

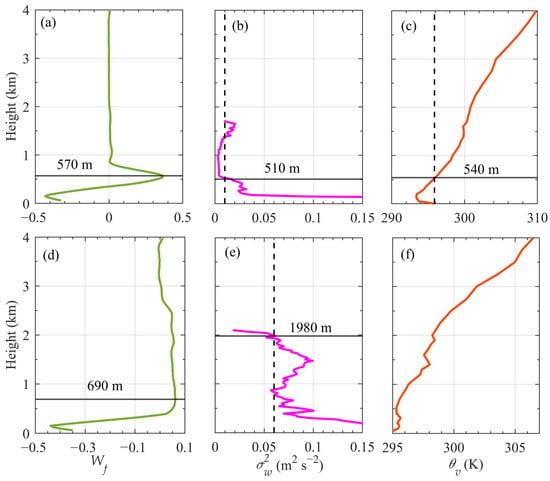

Figure 10.

Comparison of vertical profiles derived from the DWL and the MWR at 11:10 LST on 03 November 2023 and 14:10 LST on 04 November 2023. (a–c) Profiles on 03 November; (d–f) profiles on 04 November. (a,d) Haar wavelet covariance coefficients ; (b,e) vertical velocity variance , where the black dashed line indicates the threshold of 0.06 m2 s−2 (b) and 0.01 m2 s−2 (e); (c,f) virtual potential temperature , where the black dashed line represents the surface virtual potential temperature . The black solid lines denote the BLHs determined from each method.

During this two-day cloudy period, four RS launches were conducted. and showed good consistency (Table 3). Because temperature inversions were intermittent, only discontinuous BLH points could be identified with SBI method (Figure 9d). Nonetheless, closely matched the RS-derived heights when the SBI method was applicable. Additionally, under clear-sky conditions at 07:15 on 3 November, agreed well with the RS results (Table 3). However, after sunset, cloud shielding and signal attenuation led to underestimation of and relative to the RS results.

Table 3.

Comparison of BLHs retrieved by different methods at 07:15 and 19:15 LST on 03–04 November 2023 at 54511 Station.

Overall, during 3–4 November, intermittent clouds during daytime weakened surface heating and suppressed turbulence, while nighttime cloud scattering obscured aerosol gradients, rendering the HWCT method ineffective. As turbulence weakened on 4 November, the threshold of the variance method required adjustment to 0.01 m2 s−2 to capture shallow mixing-layer evolution. In contrast, the method was less affected and continued to depict a coherent thermodynamic structure. The differences among the three methods in this case study indicate that under cloudy conditions, the HWCT method suffers from severe CNR contamination, The variance method requires adjustment of the threshold to account for changes in turbulence intensity, and the parcel method exhibits the strongest robustness to environmental variability.

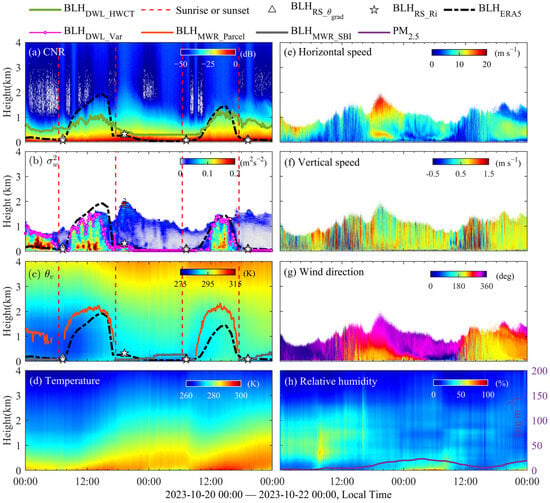

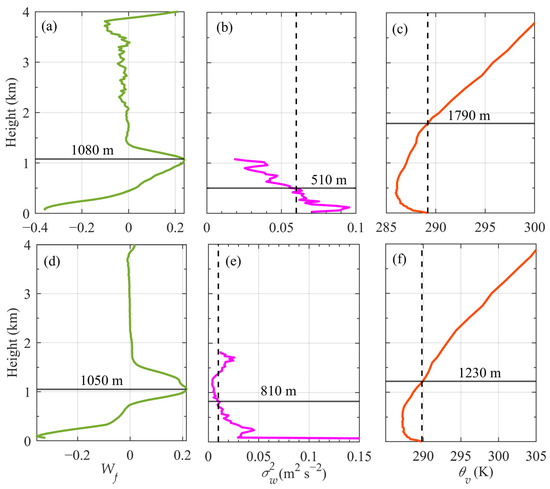

4.2.3. Case 2: Hazy Days

During 1–2 November 2023, a typical haze episode occurred over the experimental site. The surface temperature ranged from 12 °C to 22 °C on 1 November and from 9 °C to 20 °C on 2 November. The PM2.5 concentration remained above 100 μg m−3 during daytime, peaking at 174 μg m−3 at noon on 1 November, indicating a moderate pollution level. Surface relative humidity exceeded 85% during both nights and reached 100% in the early morning of 1 November. Under these humid and polluted conditions, strong aerosol–droplet interactions caused severe signal extinction and multiple scattering below 300 m, resulting in pronounced speckle noise and degraded data quality in the DWL observations (Figure 11e–g). This constitutes a key instrumental limitation during this case study.

Figure 11.

Multi-source observational profiles under cloudy conditions at the observation site on 01–02 November 2023: (a) CNR; (b) ; (c) virtual potential temperature ; (d) temperature; (e) horizontal wind speed; (f) vertical wind speed; (g) wind direction; (h) relative humidity and PM2.5 concentration. The green, pink, blue, and orange solid lines represent BLHs retrieved from HWCT method, variance method with thresholds of 0.06 m2 s−2 and 0.01 m2 s−2, and parcel method, respectively. The gray solid line denotes the nighttime stable-layer height obtained from the SBI method. The triangles and pentagrams indicate BLHs derived from improved potential temperature gradient method and Richardson number method, respectively. The black dashed line shows the BLH from ERA5 data, the purple solid line indicates PM2.5 concentration (corresponding to the right y-axis in panel (h)), and the red dashed lines mark sunrise and sunset times.

Between 00:00 and 08:00 LST on 1 November, fog and haze began to develop. Radiative cooling and near-surface moisture accumulation led to the formation of a shallow fog layer. The steadily detected a layer top near 420 m, corresponding to the high-humidity region (Figure 11h), representing the upper boundary of the haze layer. Due to poor data quality below 180 m, the corresponding values were excluded, and the remaining profile showed extremely low turbulence (<0.02 m2 s−2). The presence of a near-surface inversion (Figure 11d) allowed the SBI method to continuously identify a shallow boundary layer around 120 m before sunrise.

During 10:00–17:00 LST on 1 November, PM2.5 remained at its daily maximum. Despite increasing surface heating after sunrise, the convective mixing remained too weak to effectively disperse pollutants, resulting in suppressed turbulence (Figure 11b). Following the same adjustment strategy as for the cloudy case, the threshold of variance method was reduced to 0.01 m2 s−2 to capture weak turbulence (Figure 11b and Figure 12b). The retrieved remained below 600 m, peaking at 570 m around 14:40 LST. The rose gradually, reaching 610 m at 13:26 LST, while stayed near 650 m. As shown in Figure 11a–c, except for , which was strongly affected by haze and thus underestimated, and exhibited good consistency with , jointly capturing the daytime boundary-layer evolution during the haze period.

Figure 12.

Comparison of vertical profiles derived from the DWL and the MWR at 13:00 LST on 01 November 2023 and 19:10 LST on 02 November 2023. (a–c) Profiles on 01 November; (d–f) profiles on 02 November. (a,d) Haar wavelet covariance coefficients ; (b,e) vertical velocity variance , where the black dashed line indicates the threshold of 0.01 m2 s−2 (b) and 0.06 m2 s−2 (e); (c,f) virtual potential temperature , where the black dashed line represents the surface virtual potential temperature . The black solid lines denote the BLHs determined from each method.

Around 00:00 LST on 2 November, relative humidity below 1 km increased markedly (Figure 11h), and the lidar CNR field exhibited a persistent high-intensity layer beneath 500 m (Figure 11a). The effectively captured the upper edge of this layer, corresponding to the top of the material boundary (Figure 11a). After 09:00 LST, increased steadily, reaching a maximum of 750 m at 13:20 LST. Around 13:00 LST, winds turned abruptly to northwesterly, marking a distinct transition in the boundary-layer flow (Figure 11g), with horizontal wind speed exceeding 15 m s−1 (Figure 11e). The strengthened mechanical mixing triggered vigorous vertical motions (Figure 11f), causing to rapidly ascend (Figure 11b). Under the higher threshold of 0.06 m2 s−2, abruptly jumped to about 2.6 km at 18:20 LST, clearly marking the strong convective process induced by the wind surge. In contrast, remained below 1 km, limited by the rapid dilution of aerosols after haze clearance. As shown in Figure 12d, during this wind-cleaning phase, profiles still exhibited identifiable local maxima, but the peaks became broad and less distinct, reflecting smoother gradients compared to earlier convective conditions. The attenuation of the peak signatures suggests that the boundary layer underwent re-mixing and structural reorganization during ventilation by strong winds. After 20:00 LST, PM2.5 concentrations dropped sharply below 50 μg m−3, and relative humidity fell below 10%, signaling the dissipation of haze. For the variance method, the threshold of 0.01 m2 s−2 effectively captured the shallow dynamical boundary layer under weak-turbulence haze conditions on 1 November, while the higher threshold of 0.06 m2 s−2 on 2 November successfully depicted the deep convective boundary layer triggered by strong winds.

In summary, during 1–2 November 2023, the southern suburb of Beijing experienced a typical late-autumn haze episode characterized by a shallow, stable boundary layer and inhibited daytime growth. At night, combined radiative cooling and high humidity produced a shallow inversion and haze layer, which was well captured by the SBI method, yielding BLHs of 100–200 m consistent with RS retrievals (Table 4). During daytime, the high aerosol concentration suppressed turbulence by attenuating solar radiation [65], limiting boundary layer development. Both and reflected a gradual increase to 600–700 m, a similar trend also observed in ERA5 estimates. Notably, during the night of 2 November, the onset of strong northwesterly winds reactivated turbulence, leading to rapid dilution and removal of pollutants. The field showed a pronounced near-surface increase, and the CNR field displayed enhanced backscatter lifting upward, indicating a transition from a stable to a re-mixed boundary layer. Overall, multi-instrument retrievals in this case clearly captured the generation, maintenance, and dissipation stages of the haze boundary layer, highlighting the complementarity and limitations of different retrieval methods under varying meteorological conditions.

Table 4.

Comparison of BLHs retrieved by different methods at 07:15 and 19:15 LST on 01–02 November 2023 at 54511 Station.

5. Discussion

In this study, three complementary approaches were used to retrieve BLH from a single Doppler wind lidar and a collocated MWR, namely an aerosol--CNR-based HWCT, a turbulence-based vertical velocity variance method, and a parcel method applied to virtual potential temperature profiles. The statistical comparison over all non-precipitating days (09:00–17:00 LST, 10 min averages) shows that the two Doppler-lidar-based heights are moderately correlated (R ≈ 0.6). Previous Doppler lidar intercomparison work has shown that BLH retrieved from aerosol backscatter and from vertical velocity variance can be highly correlated but still exhibit point-by-point differences of the order of 500 m, with aerosol-based heights tending to reflect the history of mixing while variance-based heights represent the current extent of active turbulent convection [54]. The parcel-based BLH from the MWR is typically higher than both lidar-based estimates by about 0.5–0.6 km, and the difference is even greater on clear-sky days. This differs markedly from previous studies, where BLH estimates from ceilometers or micro-pulse lidars were found to agree more closely with those from MWR [11,66]. In theory, this suggests that the parcel method is defining the upper limit of buoyant ascent, whereas the methods from DWL are constrained by the depth of effective turbulent mixing and by the actual aerosol distribution. From another perspective, it is also possible that the DWL intrinsically underestimates the BLH.

These overall patterns are consistent with the conceptual separation between a material boundary (aerosol distribution layer), a dynamical boundary (turbulent mixing layer), and a thermodynamical boundary (stability-controlled inversion), as well as with the method-dependent biases summarized in previous reviews [30,61,67]. Early studies emphasized that BLH derived from aerosol gradients, temperature profiles or turbulence metrics can differ by several hundred meters because they respond to different aspects of boundary-layer structure, rather than to a single, uniquely defined true height.

Compared with previous works, an important difference in our approach is that both the aerosol-based and turbulence-based BLHs are retrieved from the same Doppler wind lidar, using CNR and as two tracers. Many earlier intercomparison studies used different instruments to represent aerosol and turbulence (e.g., ceilometer or micro-pulse lidar vs. Doppler wind lidar), so part of the discrepancy could be attributed to instrumental differences or sampling mismatch. Our comparison avoids this cross-instrument issue and therefore isolates the impact of the physical tracer itself: even when CNR and are derived from the same beams and sampling volumes, the resulting BLHs still exhibit systematic offsets that reflect the different response of aerosols and turbulence to changes in different conditions.

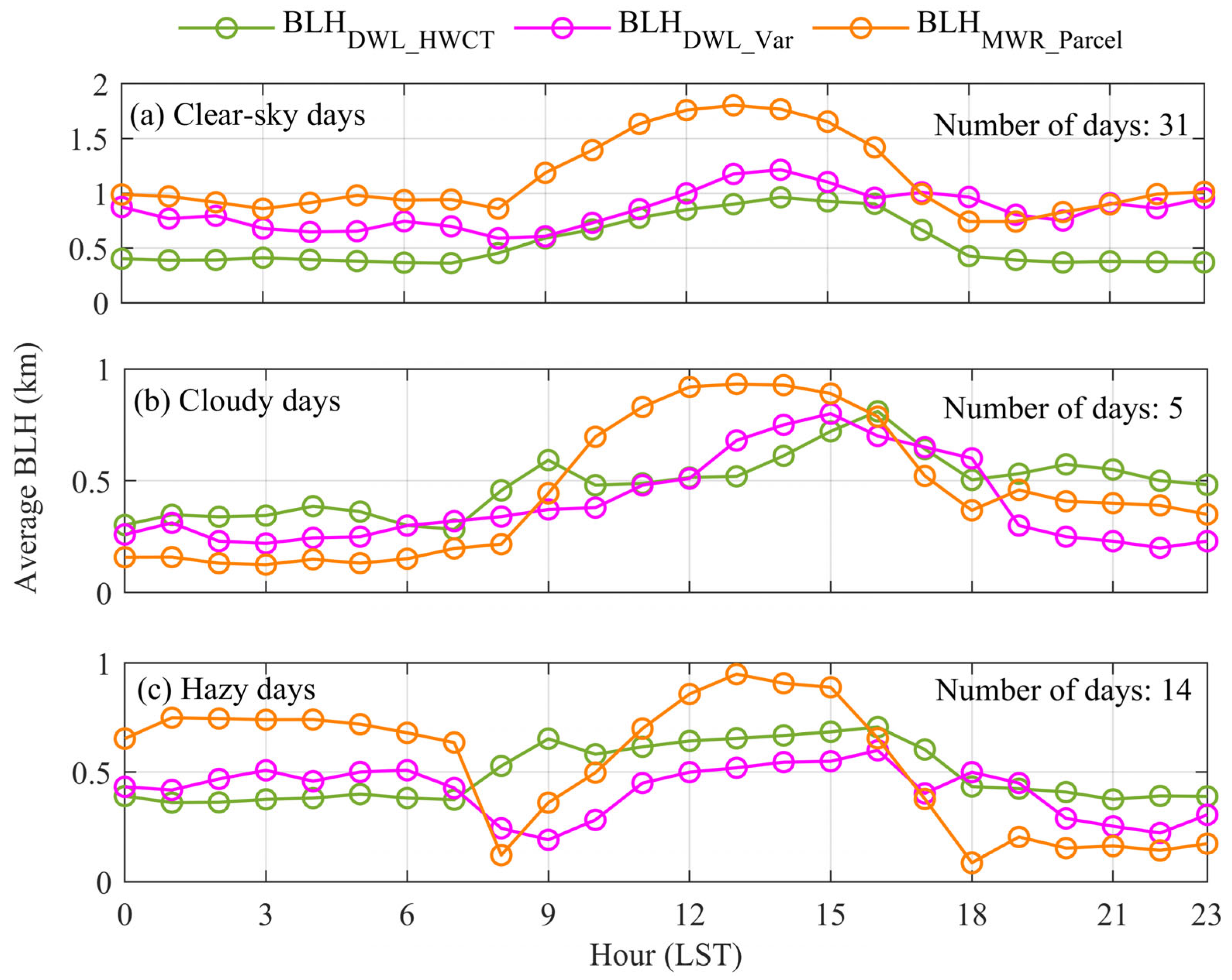

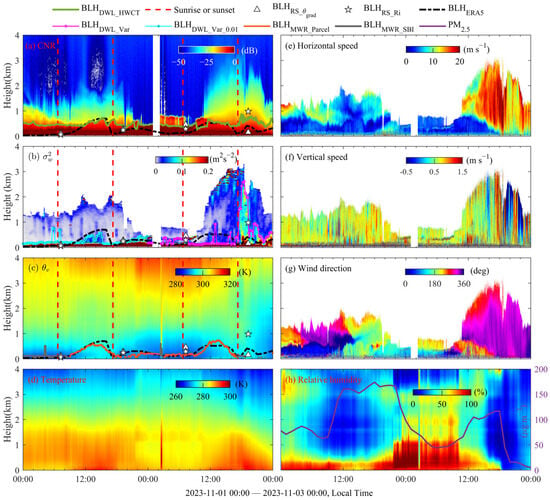

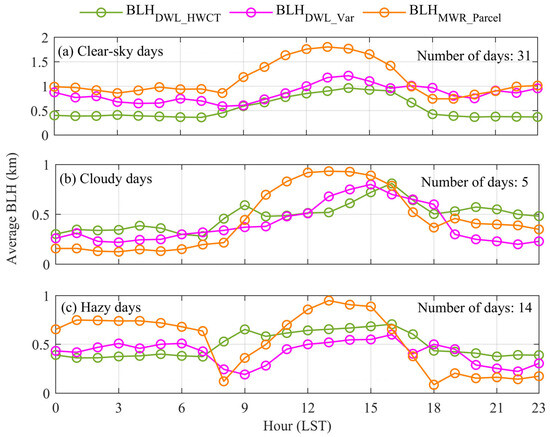

The weather-type case studies provide additional physical insight into how these three diagnostics respond under different regimes. In the two selected clear-sky days, the three methods show broadly consistent diurnal cycles. Although their temporal variations are similar, the BLH retrieved from the MWR parcel method is generally higher than that from the two DWL-based methods. In contrast, under multi-layer cloud or hazy conditions, the differences between the three definitions become much more pronounced. The CNR-based HWCT is highly sensitive to cloud droplets and humid aerosol layers, which can mask the true aerosol mixing layer and lead to spurious or elevated layer detection. The turbulence-based σw2 method becomes less reliable when convection weakens or stratification strengthens, making its results highly dependent on the chosen threshold. In this study, a lower threshold is used to capture the shallow dynamical layer. The parcel method, by comparison, remains the most stable and directly reflects thermal stratification. Figure 13 summarizes the composite diurnal evolution of BLH for the three weather regimes (clear-sky, cloudy, and hazy), obtained by averaging all hourly estimates over the days in each category (sample size shown in each panel). Under clear-sky conditions, the three diagnostics exhibit a coherent daytime growth and evening decay, while the MWR parcel method systematically yields higher BLH than the two DWL-based methods. For cloudy and hazy days, the three BLH estimates remain closer to each other than in the clear-sky composite. Moreover, because the variance and parcel methods often fail to retrieve BLH during SBL periods, the effective sample size is reduced, which can lead to fluctuations in the mean curves.

Figure 13.

Diurnal variations of the averaged BLH derived from the HWCT method, the variance method, and the Parcel method under different weather conditions. (a–c) panels represent the composite mean for clear-sky, cloudy, and hazy days, respectively. The numbers in each subplot indicate the total number of days included in the averaging.

The MWR used in this study has vertical resolutions of 25 m (0–500 m), 50 m (500 m to 2 km), and 250 m (2 km to 10 km) in different height ranges. To improve spatial resolution, we interpolated the MWR data to a 10 m height interval. Although this interpolation increases the apparent resolution, it may also introduce excessively vertical smoothing, especially above 2 km, potentially weakening sharp temperature gradients or inversions. Such smoothing could bias the parcel and SBI method retrievals by slightly altering the identified intersection height or reducing the gradient strength at the capping inversion. However, since the selected period for this study falls in autumn and winter, with retrieval heights generally below 2 km, the parcel method is expected to be weakly affected by the interpolation. Moreover, the MWR provides relatively fine native vertical resolution in the low levels, so the SBI method detection in this layer is not substantially biased by the interpolation-induced smoothing. The Doppler lidar provides high-precision wind speed and direction data, but its data quality may be influenced by weather conditions, particularly under cloudy and high-humidity conditions, where the accuracy of wind speed retrieval may decrease, which could affect the quality of BLH retrieval.

Overall, these results demonstrate that no single method provides a universally valid BLH under all weather conditions. Instead, each method reflects a different physical boundary—material, dynamical or thermal—and their degree of agreement depends strongly on cloudiness, humidity, stability and wind conditions. The joint use of DWL and MWR therefore provides complementary and physically interpretable diagnostics of boundary layer structure across varying weather regimes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.L. and Z.S.; Data curation, C.L. and Z.S.; Formal analysis, C.L.; Funding acquisition, Z.S.; Investigation, C.L., L.Y., H.W., Y.H. and S.W.; Methodology, C.L. and Z.S.; Project administration, Z.S.; Resources, Z.S. and S.W.; Software, C.L.; Supervision, Z.S.; Visualization, C.L.; Writing—original draft, C.L.; Writing—review and editing, C.L., C.C. and Z.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 42205003, the Ecological Environment Research Project of Jiangsu Province, grant number 2022007, and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province, grant number BK20230434.

Data Availability Statement

The Doppler wind lidar, microwave radiometer and radiosonde data used in this work are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The PM2.5 data can be applied for through this link: https://www.bjmemc.com.cn/ (accessed on 1 September 2025). The reanalysis data (ERA5) can be applied for through this link: https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/reanalysis-era5-single-levels?tab=download (accessed on 2 September 2025).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge our colleagues at the Beijing Meteorological Observation Centre for their kind assistance and technical support during our field campaign. We thank Shenzhen Dashun Laser Technology Co., Ltd. and Hangzhou Qianhai Technology Co., Ltd. for providing the instrument data used in this study. We also express our sincere gratitude to all anonymous reviewers for their insightful and valuable comments.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Shenghuan Wen was employed by the company Puda (Beijing) Technology Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Stull, R.B. An Introduction to Boundary Layer Meteorology; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Garratt, J.R. The atmospheric boundary layer. Earth Sci. Rev. 1994, 37, 89–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmén, E.H.; Newton, C.W. Atmospheric Circulation Systems: Their Structure and Physical Interpretation; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1969; Volume 13. [Google Scholar]

- Holtslag, A. Atmospheric boundary layers: Modeling and parameterization. In Encyclopedia of Atmospheric Sciences, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 265–273. [Google Scholar]

- Huo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Paasonen, P.; Liu, Q.; Tang, G.; Ma, Y.; Petaja, T.; Kerminen, V.-M.; Kulmala, M. Trends of planetary boundary layer height over urban cities of China from 1980–2018. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 744255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Wang, X.; Ning, G.; Yuan, L.; Jiang, M.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S. Factors influencing the boundary layer height and their relationship with air quality in the Sichuan Basin, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 727, 138584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peña, A.; Floors, R.; Sathe, A.; Gryning, S.-E.; Wagner, R.; Courtney, M.S.; Larsén, X.G.; Hahmann, A.N.; Hasager, C.B. Ten years of boundary-layer and wind-power meteorology at Høvsøre, Denmark. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 2016, 158, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vajda, A.; Tuomenvirta, H.; Jokinen, P.; Luomaranta, A.; Makkonen, L.; Tikanmäki, M.; Groenemeijer, P.; Saarikivi, P.; Michaelides, S.; Papadakis, M. Probabilities of Adverse Weather Affecting Transport in Europe: Climatology and Scenarios up to the 2050s; Ilmatieteen Laitos: Helsinki, Finland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Halios, C.H.; Barlow, J.F. Observations of the morning development of the urban boundary layer over London, UK, taken during the ACTUAL project. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 2018, 166, 395–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, D.J.; Ao, C.O.; Li, K. Estimating climatological planetary boundary layer heights from radiosonde observations: Comparison of methods and uncertainty analysis. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2010, 115, D16113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collaud Coen, M.; Praz, C.; Haefele, A.; Ruffieux, D.; Kaufmann, P.; Calpini, B. Determination and climatology of the planetary boundary layer height above the Swiss plateau by in situ and remote sensing measurements as well as by the COSMO-2 model. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2014, 14, 13205–13221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liang, X.-Z. Observed diurnal cycle climatology of planetary boundary layer height. J. Clim. 2010, 23, 5790–5809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zhang, J.; Shao, J.; Chen, T.; Bai, K.; Sun, Y.; Li, N.; Wu, J.; Li, R.; Li, J.; et al. A merged continental planetary boundary layer height dataset based on high-resolution radiosonde measurements, ERA5 reanalysis, and GLDAS. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2024, 16, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Arruda Moreira, G.; Pérez Herrera, M.J.; Garnés Morales, G.; Costa, M.J.; Cacheffo, A.; Carbone, S.; Lopes, F.J.d.S.; Abril-Gago, J.; Andújar-Maqueda, J.; de Souza Fernandes Duarte, E. Monthly Convective Boundary Layer Height Study over Brazil Using Radiosonde, ERA5, and COSMIC-2 Data. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Li, M.; Ning, G.; Wei, T.; Yuan, J.; Xia, H. Estimating the full-day planetary boundary height from lidar, AMDAR, and radiosonde observations over Beijing, China. Atmos. Res. 2025, 332, 108701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, X.; Song, T.; Münkel, C.; Hu, B.; Schäfer, K.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L. Mixing layer height and its implications for air pollution over Beijing, China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2016, 16, 2459–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Grimmond, C.S.B.; Fu, X.; Chang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Guo, J.; Tang, C.; Gao, J.; Xu, X.; Tan, J. Ceilometer-based analysis of Shanghai’s boundary layer height (under rain-and fog-free conditions). J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2017, 34, 749–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimini, D.; De Angelis, F.; Dupont, J.-C.; Pal, S.; Haeffelin, M. Mixing layer height retrievals by multichannel microwave radiometer observations. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2013, 6, 2941–2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; He, W.; Liu, H.; Chen, H. Retrieval of atmospheric boundary layer height from ground-based microwave radiometer measurements. J. Appl. Meteor. Sci. 2015, 26, 626–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Liu, S.; Yu, X.; Li, X.; Chen, C.; Peng, Y.; Dong, Y.; Dong, Z.; Wang, F. Urban boundary layer height characteristics and relationship with particulate matter mass concentrations in Xi’an, central China. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2013, 13, 1598–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Han, Y.; Hu, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, Y.; Dong, L.; Xiao, P. Characteristics of Planetary Boundary Layer Height (PBLH) over Shenzhen, China: Retrieval Methods and Air Pollution Conditions. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, R.S.; Keimig, F.T.; Diaz, H.F. Recent changes in the North American Arctic boundary layer in winter. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1993, 98, 8851–8858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caicedo, V.; Delgado, R.; Sakai, R.; Knepp, T.; Williams, D.; Cavender, K.; Lefer, B.; Szykman, J. An automated common algorithm for planetary boundary layer retrievals using aerosol lidars in support of the US EPA Photochemical Assessment Monitoring Stations Program. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2020, 37, 1847–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, W.; Ren, X.; Peng, K.; Ahmad, M.; Jia, D.; Zhao, D.; Kong, L.; Ma, Y. High-resolution remote sensing of the gradient Richardson number in a megacity boundary layer. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimini, D.; Campos, E.; Ware, R.; Albers, S.; Giuliani, G.; Oreamuno, J.; Joe, P.; Koch, S.E.; Cober, S.; Westwater, E. Thermodynamic atmospheric profiling during the 2010 Winter Olympics using ground-based microwave radiometry. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2011, 49, 4959–4969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, L.; Friedrich, K.; Wilczak, J.M.; Hazen, D.; Wolfe, D.; Delgado, R.; Oncley, S.P.; Lundquist, J.K. Assessing the accuracy of microwave radiometers and radio acoustic sounding systems for wind energy applications. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2017, 10, 1707–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Shi, Y.; Ren, Y.; Li, Q.; Qiao, Z.; Cao, J.; Ayantobo, O.O.; Yin, J.; Wang, G. Application of ground-based microwave radiometer in retrieving meteorological characteristics of Tibet Plateau. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flamant, C.; Pelon, J.; Flamant, P.H.; Durand, P. Lidar determination of the entrainment zone thickness at the top of the unstable marine atmospheric boundary layer. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 1997, 83, 247–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicard, M.; Pérez, C.; Rocadenbosch, F.; Baldasano, J.; García-Vizcaino, D. Mixed-layer depth determination in the Barcelona coastal area from regular lidar measurements: Methods, results and limitations. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 2006, 119, 135–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emeis, S.; Schafer, K.; Munkel, C. Surface-based remote sensing of the mixing-layer height-a review. Meteorol. Z. 2008, 17, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Gao, Z.; Kalogiros, J.; Li, Y.; Yin, J.; Li, X. Estimate of boundary-layer depth in Nanjing city using aerosol lidar data during 2016–2017 winter. Atmos. Environ. 2019, 205, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, E.; Pelon, J.; Flamant, C. Study of the moist convective boundary layer structure by backscattering lidar. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 1994, 69, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strawbridge, K.; Snyder, B. Planetary boundary layer height determination during Pacific 2001 using the advantage of a scanning lidar instrument. Atmos. Environ. 2004, 38, 5861–5871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melfi, S.; Spinhirne, J.; Chou, S.-H.; Palm, S. Lidar observations of vertically organized convection in the planetary boundary layer over the ocean. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 1985, 24, 806–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, S.A.; Angevine, W.M. Boundary layer height and entrainment zone thickness measured by lidars and wind-profiling radars. J. Appl. Meteorol. 2000, 39, 1233–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, I.M. Finding boundary layer top: Application of a wavelet covariance transform to lidar backscatter profiles. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2003, 20, 1092–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morille, Y.; Haeffelin, M.; Drobinski, P.; Pelon, J. STRAT: An automated algorithm to retrieve the vertical structure of the atmosphere from single-channel lidar data. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2007, 24, 761–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Shang, Y.; Li, Z.; Lu, C.; Zhan, P.; Song, X.; Lv, M.; Yang, Y. Assessment of Multiple Planetary Boundary Layer Height Retrieval Methods and Their Impact on PM2.5 and Its Chemical Compositions throughout a Year in Nanjing. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopoulos, J.; Saide, P.; Ferrare, R.; Collister, B.; Barton-Grimley, R.; Scarino, A.; Collins, J.; Hair, J.; Nehrir, A. Improving planetary boundary layer height estimation from airborne lidar instruments. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2025, 130, e2024JD042538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.G.; Eckert, C.; Kelaher, B.P.; Harrison, D.P.; Schofield, R. Boundary layer height above the Great Barrier Reef studied using drone and Mini-Micropulse LiDAR measurements. J. South. Hemisph. Earth Syst. Sci. 2024, 74, ES24008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.; Haeffelin, M.; Batchvarova, E. Exploring a geophysical process-based attribution technique for the determination of the atmospheric boundary layer depth using aerosol lidar and near-surface meteorological measurements. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2013, 118, 9277–9295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haeffelin, M.; Angelini, F.; Morille, Y.; Martucci, G.; Frey, S.; Gobbi, G.; Lolli, S.; O’dowd, C.; Sauvage, L.; Xueref-Remy, I. Evaluation of mixing-height retrievals from automatic profiling lidars and ceilometers in view of future integrated networks in Europe. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 2012, 143, 49–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angevine, W.M.; White, A.B.; Avery, S.K. Boundary-layer depth and entrainment zone characterization with a boundary-layer profiler. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 1994, 68, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, A.; Senff, C.; Banta, R. A comparison of mixing depths observed by ground-based wind profilers and an airborne lidar. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 1999, 16, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compton, J.C.; Delgado, R.; Berkoff, T.A.; Hoff, R.M. Determination of planetary boundary layer height on short spatial and temporal scales: A demonstration of the covariance wavelet transform in ground-based wind profiler and lidar measurements. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2013, 30, 1566–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, V.; Teschke, G. Advanced intermittent clutter filtering for radar wind profiler: Signal separation through a Gabor frame expansion and its statistics. Ann. Geophys. 2008, 26, 759–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wang, L.; Qiang, W.; Xia, H.; Wei, T.; Yuan, J.; Jiang, P. Robust Solution for Boundary Layer Height Detections with Coherent Doppler Wind Lidar. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2021, 38, 1920–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, A.; Gryning, S.E.; Hahmann, A.N. Observations of the atmospheric boundary layer height under marine upstream flow conditions at a coastal site. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2013, 118, 1924–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, S.C.; Senff, C.J.; Weickmann, A.M.; Brewer, W.A.; Banta, R.M.; Sandberg, S.P.; Law, D.C.; Hardesty, R.M. Doppler lidar estimation of mixing height using turbulence, shear, and aerosol profiles. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2009, 26, 673–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, J.F.; Dunbar, T.; Nemitz, E.; Wood, C.R.; Gallagher, M.; Davies, F.; O’Connor, E.; Harrison, R. Boundary layer dynamics over London, UK, as observed using Doppler lidar during REPARTEE-II. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2011, 11, 2111–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Xia, H.; Yuan, J.; Wang, Y.; Maituerdi, A.; He, Q. Study on daytime atmospheric mixing layer height based on 2-Year coherent doppler wind lidar observations at the southern edge of the Taklimakan Desert. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, J.; Luo, H.; Lu, C.; Lin, X.; Yang, H.; Zhang, N. Characteristics of the atmospheric boundary layer height: A perspective on turbulent motion. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 919, 170895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirsikko, A.; O’Connor, E.; Komppula, M.; Korhonen, K.; Pfüller, A.; Giannakaki, E.; Wood, C.; Bauer-Pfundstein, M.; Poikonen, A.; Karppinen, T. Observing wind, aerosol particles, cloud and precipitation: Finland’s new ground-based remote-sensing network. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2014, 7, 1351–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schween, J.; Hirsikko, A.; Löhnert, U.; Crewell, S. Mixing-layer height retrieval with ceilometer and Doppler lidar: From case studies to long-term assessment. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2014, 7, 3685–3704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, D.J.; Zhang, Y.; Beljaars, A.; Golaz, J.C.; Jacobson, A.R.; Medeiros, B. Climatology of the planetary boundary layer over the continental United States and Europe. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2012, 117, D17106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zhang, J.; Yang, K.; Liao, H.; Zhang, S.; Huang, K.; Lv, Y.; Shao, J.; Yu, T.; Tong, B. Investigation of near-global daytime boundary layer height using high-resolution radiosondes: First results and comparison with ERA-5, MERRA-2, JRA-55, and NCEP-2 reanalyses. Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss. 2021, 21, 17079–17097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, G.; Davies, F.; Collier, C. Remote sensing of the tropical rain forest boundary layer using pulsed Doppler lidar. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2010, 10, 5891–5901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Träumner, K.; Kottmeier, C.; Corsmeier, U.; Wieser, A. Convective boundary-layer entrainment: Short review and progress using Doppler lidar. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 2011, 141, 369–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Jia, M.; Xia, H.; Wu, Y.; Wei, T.; Shang, X.; Yang, C.; Xue, X.; Dou, X. Relationship analysis of PM 2.5 and boundary layer height using an aerosol and turbulence detection lidar. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2019, 12, 3303–3315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzworth, G.C. Estimates of mean maximum mixing depths in the contiguous United States. Mon. Weather Rev. 1964, 92, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibert, P.; Beyrich, F.; Gryning, S.-E.; Joffre, S.; Rasmussen, A.; Tercier, P. Review and intercomparison of operational methods for the determination of the mixing height. Atmos. Environ. 2000, 34, 1001–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Chen, H.; Guo, J.; Zhang, W. Contrasting effect of soil moisture on the daytime boundary layer under different thermodynamic conditions in summer over China. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2020GL090989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, J.; Rasmussen, A.; Svensmark, H. Forecast of atmospheric boundary-layer height utilised for ETEX real-time dispersion modelling. Phys. Chem. Earth 1996, 21, 435–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Haij, M.; Wauben, W.; Baltink, H.K. Continuous Mixing Layer Height Determination Using the LD-40 Ceilometer: A Feasibility Study; Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI): De Bilt, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Gao, Z.; Li, Y.; Huang, M.; Fan, S.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Y.; Miao, S.; Zou, H. Vertical observations of the atmospheric boundary layer structure over Beijing urban area during air pollution episodes. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2019, 19, 6949–6967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Cao, X.; Zhang, L.; Notholt, J.; Zhou, B.; Liu, R.; Zhang, B. Lidar measurement of planetary boundary layer height and comparison with microwave profiling radiometer observation. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2012, 5, 1965–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]