Highlights

What are the main findings?

- This paper designs a heterogeneous change detection method based on a neural architecture search, which builds an adaptive discriminator via a differential filter-based composition search (DFCS) strategy.

- A Gabor filter and local normalized cross-correlation (G-LNCC)-based module is designed for robust cross-modal feature alignment at the input stage.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- The introduction of the Differentiable Neural Architecture Search (NAS) process offers a novel and adaptive paradigm for the Hete-CD field, overcoming the limitations of fixed deep network architectures.

- The model demonstrates strong generalizability and dynamic learning capabilities in complex Hete-CD tasks.

Abstract

Heterogeneous remote sensing image change detection (Hete-CD) holds significant research value in military and civilian fields. The existing methods often rely on expert experience to design fixed deep network architectures for cross-modal feature alignment and fusion purposes. However, when faced with diverse land cover types, these methods often lead to blurred change boundaries and structural distortions, resulting in significant performance degradations. To address this, we propose an adaptive adversarial learning-based heterogeneous remote sensing image change detection method based on the differentiable filter combination search (DFCS) strategy to provide enhanced generalizability and dynamic learning capabilities for diverse scenarios. First, a fully reconfigurable self-learning discriminator is designed to dynamically synthesize the optimal convolutional architecture from a library of atomic filters containing basic operators. This provides highly adaptive adversarial supervision to the generator, enabling joint dynamic learning between the generator and discriminator. To further mitigate modality differences in the input stage, we integrate a feature fusion module based on the Gabor and local normalized cross-correlation (G-LNCC) to extract modality-invariant texture and structure features. Finally, a geometric structure-based collaborative supervision (GSCS) loss function is constructed to impose fine-grained constraints on the change map from the perspectives of regions, boundaries, and structures, thereby enforcing physical properties. Comparative experimental results obtained on five public Hete-CD datasets show that our method achieves the best F1 values and overall accuracy levels, especially on the Gloucester I and Gloucester II datasets, achieving F1 scores of 93.7% and 95.0%, respectively, demonstrating the strong generalizability of our method in complex scenarios.

1. Introduction

With the rapid development of Earth observation technology, the demand for highly robust solutions in complex environments has become increasingly urgent. Heterogeneous remote sensing image change detection (Hete-CD), as a critical technical approach, has demonstrated significant application potential in various fields, including urban expansion monitoring, disaster assessment, environmental change monitoring, and land use change analysis. It represents a highly challenging and valuable research direction within the field of remote sensing image processing.

Hete-CD can effectively integrate data from different sensors to provide precise analyses of multidimensional geographical information changes, meeting the diverse demands of modern remote sensing technology in complex application scenarios. For instance, in natural disaster assessments, SAR images can provide timely monitoring for affected areas irrespective of the current weather conditions, whereas optical imagery offers high-precision descriptions of surface details after a disaster. In the military and security domains, Hete-CD is widely applied to monitor activity changes in sensitive areas and respond to urban changes during armed conflicts [1]. In agriculture and forest resource management, the combination of optical and hyperspectral imagery can be used to effectively detect dynamic vegetation cover and crop growth status changes. In emergencies triggered by natural disasters, when homogeneous imagery is not readily available, monitoring land cover changes via Hete-CD becomes particularly crucial [2]. By leveraging the complementary advantages of different data sources, Hete-CD can more comprehensively and precisely monitor surface changes. This provides strong support for emergency responses, natural resource management, and the detection of and rapid response to unforeseen events while also laying the foundation for long-term ground condition monitoring.

Compared with Homo-CD, Hete-CD poses greater challenges. First, the images captured by different types of sensors exhibit significant differences in their geometric characteristics, radiometric properties, imaging mechanisms, and imaging results [3], posing significant challenges for image registration and feature matching tasks. Second, heterogeneous images often have different data distributions and feature representations [4], making the traditional pixel-based comparison methods difficult to apply directly. Additionally, owing to the difficulty of obtaining fully matched heterogeneous images, annotated training data are often limited, further complicating the development of effective algorithms. However, Hete-CD also offers unique advantages. Different sensors can provide complementary information; examples include as optical images, which offer rich spectral information, whereas SAR images can penetrate clouds to provide all-weather observation capabilities. By integrating this complementary information, we can potentially obtain more comprehensive and accurate change detection results. With the continuous advancement of remote sensing imaging technology, an increasing amount of multisource remote sensing data, such as geographic information system data, high-resolution satellite images, and drone images, cover the same geographical area [5]. Utilizing these heterogeneous data for change detection can overcome the limitations of a single data source and improve the timeliness and coverage of detection.

In recent years, significant progress has been made in the field of Hete-CD. Researchers have proposed various innovative methods to address issues such as feature representation, image registration, and information fusion involving heterogeneous data. Early methods based on manual features primarily relied on statistical models, similarity metrics, and classification rules for change detection purposes. Although these methods are simple and intuitive, they have limitations when addressing complex scenarios. With the rise of deep learning, methods based on deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs) [6] have attained significantly improved heterogeneous image change detection performance due to their powerful feature extraction and representation capabilities. Through end-to-end learning frameworks, these methods can automatically discover deep features in images and effectively handle modal differences between heterogeneous data. Recently, the application of generative adversarial networks (GANs) [7] has provided new insights for addressing domain adaptation issues in cases with heterogeneous images. Through image transformation and adversarial learning, GANs can achieve feature alignment and style transfer between images belonging to different modalities. However, these methods generally rely on fixed network architectures, which limits their adaptability. Particularly in GAN-based frameworks, a fixed, manually designed discriminator becomes a performance bottleneck. It provides low-quality supervisory signals that fail to capture subtle defects such as blurred boundaries and structural distortions, thereby limiting the final detection accuracy of the constructed model.

To address the above challenges, we incorporate neural architecture search (NAS) and, for the first time, propose a differentiable filter combination search (DFCS) strategy specifically for adaptive discriminator design in GAN-based heterogeneous remote sensing image change detection. This approach provides enhanced generalizability and dynamic learning capabilities for diverse scenarios. The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows.

- We propose a differentiable filter combination search (DFCS) strategy and, for the first time, apply it to the adaptive discriminator design in GAN-based Hete-CD. This builds a fully reconfigurable self-learning discriminator that can dynamically synthesize the optimal convolutional architecture from a library of atomic filters containing basic operators such as edge and texture detectors. This provides highly adaptive adversarial supervision for the generator and enables dynamic learning for the generator and discriminator.

- We design a Gabor and local normalized cross-correlation (G-LNCC)-based feature fusion module to extract modality-invariant texture and local structure features at the front end of the network, effectively reducing the modal discrepancies at the input stage.

- We construct a geometric structure-based collaborative supervision (GSCS) loss, which combines pixel-level, boundary-aware and global structure losses to impose fine-grained constraints on the generated change map from multiple dimensions, significantly improving the ability of the model to clearly depict boundaries and represent structural integrity and enhancing its physical interpretability.

2. Related Works

2.1. Heterogeneous Image Change Detection

According to their learning frameworks, Hete-CD methods can be divided into traditional methods and deep learning methods.

In traditional methods, parameter-based techniques typically use mixed Gaussian distributions or multivariate distributions to model the relationships between different sensor images and quantify changes by solving these parameters. Representative approaches include the Kullback–Leibler distance-based change measure proposed by Mercier et al. [8], the local copula-based model developed by Prendes et al. [9], and the Markov model for multimodal change detection designed by Touati et al. [4]. Similarity-based methods emphasize the similarity between the pixels of heterogeneous images, such as the similarity map estimation technique proposed by Alberga et al. [10] and a method based on patch similarity map matrices proposed by Sun et al. [11], which use self-expressive feature learning and prior sparse knowledge to obtain change images. Later, Sun et al. [12] proposed a heterogeneous change detection (Hete-CD) method based on nonlocal patch-based graphs (NLPGs), and Sun et al. [13] proposed an improved nonlocal patch-based graph method (an improved nonlocal patch-based graph, INLPG). Classification-based methods obtain change detection results by comparing the classification maps of heterogeneous remote sensing images. Representative works include that of Zhou et al. [14], who proposed multitemporal segmentation and compound classification (MS-CC), and that of Mubea and Menz [15] and Wan et al. [16] who adopted postclassification comparison (PC-CC). The core idea of transformation- and projection-based methods is to transfer heterogeneous images to a shared feature space. Luppino et al. [17] used image regression to map images from the source domain to the target image domain by using pseudotraining data generated from a prior affinity matrix; Mignotte [18] used a modified geometric fractal decomposition and contraction mapping method to project images onto any image modality.

Among deep learning methods, CNNs have become some the mainstream approaches in the Hete-CD domain because of their spatial feature representation and local pattern recognition advantages. These methods typically adopt multibranch architectures, processing data from different modalities through independent feature extraction networks; this is followed by performing a change analysis in the feature space. To address the feature differences in heterogeneous data, Zhang et al. [19] proposed a domain adaptation neural network (a domain adaptation-based multisource change detection network, DA-MSCDNet), Jiang et al. [20] proposed a transfer learning-based semisupervised Siamese network (a multilevel semisupervised Siamese network, MLSSN), and Liu et al. [21] proposed a symmetric deep convolutional coupled network (SCCN). Xu et al. [22] proposed UCDFormer (unsupervised change detection using transformer-driven image translation), which adopts a lightweight transformer-based image translation method. More recently, several innovative unsupervised frameworks have further advanced the field by focusing on structural alignment and invariant representations. For instance, RIEM [23] establishes a reversible image-to-edge mapping to align heterogeneous features in a structural domain, effectively preserving geometric consistency across different sensors. Meanwhile, SDIR [24] leverages similarity-guided deep representations to capture robust invariant features, specifically addressing the challenges of non-linear radiometric distortions without the need for labeled data.

2.2. Applications of GANs in Heterogeneous Change Detection

GANs have demonstrated significant potential in the Hete-CD domain because of their unique adversarial learning mechanism. Their core advantage lies in their ability to achieve domain adaptation between images from different modalities through the competitive learning process conducted between the generator and the discriminator. Specifically, the generator learns to map source-domain images to the distribution space of the target domain, generating images that are highly similar to the real images from both visual and semantic perspectives. The discriminator guides the generator to continuously improve by distinguishing between the real samples and generated samples. This adversarial training mechanism enables GANs to capture the intrinsic correlations between different modal data, effectively reducing feature distribution differences and thus providing a more reliable analytical foundation for performing heterogeneous change detection.

Wang et al. [25] proposed a GAN-based Hete-CD framework (CD-GAN) to achieve image conversion between different modalities through generative adversarial learning, simplifying the change detection task. The core advantage of this method lies in its ability to construct a unified representation of heterogeneous data in the feature space or image space, facilitating the subsequent change detection process. Conditional generative adversarial networks (cGANs) [26], X-Net, and ACE-Net [17] further developed this idea by comparing the converted images in the same feature space to obtain accurate change detection results. Li et al. [27] proposed the deep translation-based convolutional detection network (DTCDN), which first focuses on reducing the differences between optical images and SAR images and then inputs the translation results into a supervised change detection network to complete the change monitoring procedure. Later, Li et al. [28] proposed a multitask convolutional detection network (MTCDN) based on the DTCDN. This network introduces a multitask learning framework to cleverly combine the image translation and change detection tasks, where image translation is responsible for aligning the two given images into the same feature domain, and the joint training and mutual reinforcement of the two tasks improve their overall efficiency while high maintaining accuracy. The two aforementioned methods are both based on supervised learning. To address the problem concerning insufficient labels in Hete-CD, Wu et al. [29] proposed an unsupervised heterogeneous change detection method based on a multidomain-constrained translation network (MDCTNet). This method performs deep translation on images, leveraging contrastive learning and frequency-domain constraints to preserve the content information of the source-domain images, while a multiscale discriminator is used to improve the quality of the generated images. Sghaier et al. [30] proposed an innovative Hete-CD method that uses GANs and autoencoders to enhance the change detection process in cases with multimodal, multitemporal remote sensing data. This method performs particularly well when high-resolution optical and SAR images are processed. Wang et al. [31] proposed a transfer learning-based multilayer convolutional adversarial network (MLCAN) for performing unsupervised change detection on heterogeneous remote sensing images. This method uses GANs to convert optical images into pseudo-SAR images and enhances the similarity between the generated images and real SAR images through adversarial training. Transfer learning is introduced to enhance the learning ability of the image transformation network, thereby improving the detection accuracy attained for change regions, especially in regions with small changes. Lv et al. [32] proposed an enhanced UNet (E-UNet) for conducting LCCD on heterogeneous remote sensing images. This method combines a cGAN with the classic UNet network to perform style conversion on images before and after events while adding multiscale convolutions in the encoding layer to handle regions with different shapes and sizes. Finally, a polarization-based self-attention module is used to focus on the changed regions. This method effectively solves the problem of incommensurability between heterogeneous remote sensing images due to the use of different sensor imaging mechanisms.

2.3. Neural Architecture Search

Neural architecture search (NAS), a cutting-edge subfield of AutoML, is aimed at automating the process of discovering optimal neural network architectures. By algorithmically exploring a predefined search space, NAS replaces the traditional, time-consuming, and expert-dependent manual design process [33,34]. While early NAS methods demonstrated promise, they often incurred extremely high computational costs. To address this bottleneck, differential architecture search (DARTS) [35] was proposed and quickly became the mainstream paradigm in the field. By relaxing the discrete search space to be continuous, DARTS allows for an efficient gradient-based optimization procedure, significantly reducing the incurred search costs and promoting the widespread application of NAS technology. Consequently, NAS has achieved great success across various computer vision domains, demonstrating significant potential in the construction of complex models such as generative adversarial networks (GANs). For example, AutoGAN [36] uses reinforcement learning to search for the architecture of the generator. Subsequent research further integrated efficient differentiable search ideas into the design of GANs, significantly improving their search efficiency by searching on continuous relaxed hypernetworks [37]. AutoGANDSP [38] addresses the instability of performance evaluation in GANAS by introducing deterministic score predictors and a two-phase selection process to balance computational efficiency with model performance. MMDAdversarialNAS [39] leverages NAS to discover optimal image generation architectures while integrating MMD repulsive loss and tensor decomposition to compress the generator for reduced inference time. Additionally, SCGAN [40] proposes a sampling and clustering-based NAS mechanism that employs constraint sampling and hierarchical clustering to significantly improve search efficiency and stability in vast architectural spaces. These advancements collectively demonstrate that adaptive architecture design and task-specific operator optimization have become key trends for enhancing generative models.

In the domain of remote sensing change detection, researchers have begun to apply NAS to address the performance bottlenecks caused by fixed network architectures. For instance, Shi et al. [41] utilized evolutionary algorithms to self-adaptively search the depths and widths of fully connected neural networks for SAR image change detection. Gong et al. [42] further extended this idea by applying NAS to search GAN architectures specifically for M-nary SAR change detection tasks. More recently, Zhang et al. [43] proposed a multiscale spatial-channel transformer architecture search method, which automatically designs effective attention mechanisms and multiscale modules for change detection purposes.

However, while these pioneering works have yielded promising results, they have focused predominantly on homogeneous change detection scenarios (e.g., SAR-to-SAR or optical-to-optical tasks). A review of the literature reveals that applying the automated design capabilities of NAS to the more challenging domain of heterogeneous change detection (Hete-CD) remains a largely unexplored research area. Therefore, this paper aims to fill this gap by being the first to apply NAS to the design of a crucial component—the discriminator—within a generative Hete-CD framework. Unlike existing methods that rely on fixed-architecture discriminators, which often suffer from structural rigidity and training instability when bridging extreme modality gaps, our NAS-driven approach enables the data-driven discovery of optimal architectural topologies. Specifically, it allows the discriminator to dynamically adjust its combination of filters—such as prioritizing denoising operators for SAR data or edge-enhancement filters for urban structures—thereby providing more precise adversarial supervision signals to the generator. This mechanism fundamentally enhances the model’s capacity for cross-modal feature alignment and structural realism, ensuring more robust performance in complex Hete-CD tasks.

3. Methodology

3.1. Overall Structure

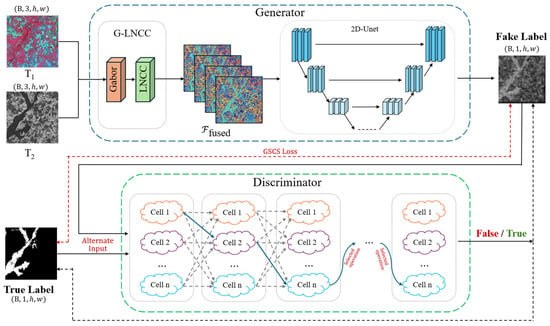

The overall network architecture is shown in Figure 1. It consists of a generator and an adaptive discriminator. The core task of the generator is to input a pair of dual-temporal heterogeneous remote sensing images T1 and T2 and output a detailed change map (fake label). To effectively process heterogeneous data, the front end of the generator integrates a G-LNCC feature fusion module. This module first processes the two input images, extracts their texture and local structure features, and fuses them into a unified and information-rich feature tensor Ffused. The fused features are then fed into a classic 2D-UNet encoder–decoder network, which performs multilevel feature extraction and upsampling to ultimately generate a single-channel change probability map with the same size as that of the input image. The discriminator is responsible for distinguishing between the “fake” change maps (fake labels) generated by the generator and the true annotated change maps (true labels). Unlike traditional fixed-structure discriminators, the designed discriminator is composed of a stack of searchable DFCS units. We design an “atomic filter base” containing multiple basic operators for each layer of the discriminator and dynamically synthesize optimal convolution kernels via learnable weights. By adaptively optimizing the architecture, the discriminator provides more targeted adversarial supervision for the generator. During training, the discriminator alternately receives real or fake variation images as inputs and outputs a scalar value to determine their authenticity. Through this adversarial training scheme, the discrimination ability of the discriminator continuously improves and feeds back effective gradient information to the generator, forcing it to learn the intrinsic data distribution of the real variation images and generate more realistic and accurate detection results.

Figure 1.

The architecture of the proposed approach.

3.2. Differentiable Filter-Based Combination Search Strategy (DFCS)

Currently, the field of heterogeneous image change detection faces a core challenge: the existing network models typically employ fixed, manually designed network architectures when processing different types of image pairs (e.g., optical and SAR images). This approach suffers from significant empirical biases and is prone to becoming stuck in local optima. Particularly in frameworks based on generative adversarial networks (GANs), the structure of the discriminator is critical for performing feature alignment and change detection, yet its design is constrained by time-consuming and suboptimal manual parameter tuning processes. In our adversarial learning framework, the effectiveness of the adversarial loss Ladv is highly dependent on a robust discriminator D. However, for complex Hete-CD tasks, a fixed, manually designed discriminator architecture is likely to be suboptimal. To address this issue, we propose the differential filter-based composition search (DFCS) strategy. The core of this strategy lies in abandoning the traditional approach of selecting from a set of predefined macro-operations. Instead, the discriminator learns to dynamically compose convolution kernels for each of its layers during training, thereby constructing a highly task-adaptive supervisory structure.

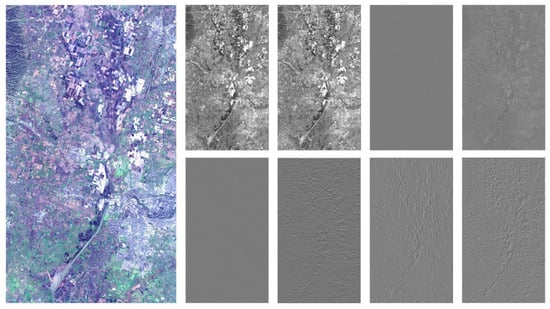

Any complex convolution kernel used for image analysis purposes can be approximated by the linear combination of a set of more basic “atomic filters” (atomic filters) [44]. To specifically address the significant modal discrepancies in Hete-CD, such as speckle noise in SAR and non-linear radiometric distortions, we constructed a curated library B = {K1, …, KM} containing M = 8 fixed, non-trainable atomic filters. Motivated by the specific challenges of heterogeneous data alignment, these filters are categorized into three distinct functional groups. First, for noise suppression, a Gaussian filter (3 × 3) is included to suppress high-frequency noise; this is essential for mitigating the coherent speckle noise prevalent in SAR imagery, preventing the discriminator from overfitting to sensor-specific artifacts. Second, regarding structural alignment, we employ three edge-sensitive operators: two Sobel filters (horizontal and vertical) and one Laplacian of Gaussian filter. Unlike raw pixel intensities which vary drastically across sensors, geometric edges and blob-like structures are modality-invariant, allowing these operators to enforce physical boundary consistency across modalities. Third, for texture representation, four Gabor filters with orientations of 0, 45, 90, and 135 degrees are utilized. These are designed to capture the anisotropic texture patterns and directional structures of man-made objects, which serve as robust indicators of change regardless of spectral appearance. By dynamically synthesizing weights for these primitives, the discriminator can adaptively construct the optimal receptive field for diverse land cover types. The filtering effects of the utilized atomic filters are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of searchable filter effects.

The framework diagram of the differentiable filter-based combination search architecture is shown in Figure 3. For the th searchable convolution layer (DFCS Conv layer) in the discriminator, we define a set of learnable architecture parameters , where represents the number of channels. These parameters are converted into normalized combination weights via a softmax function with a temperature of :

where represents the contribution of the th atomic filter in the th channel of the th layer. Subsequently, the th dynamic convolution kernel of this layer is formed by the linear combination of this set of weights and the base :

Figure 3.

The architecture of the DFCS method.

The entire search process is constructed as a two-level optimization problem [35]. This optimization problem contains two nested layers. The upper-level optimization procedure aims to find the optimal architecture parameters (), while the lower-level optimization procedure aims to find the optimal network weights () through standard training for a given set of architecture parameters α. Specifically, in our research, the search objective is to find a set of optimal filter combination parameters such that the discriminator defined by them , after being fully trained and obtaining the optimal weights , can best distinguish between real and fake variation maps. In the GAN framework, this can be formalized as follows:

where the loss function of the discriminator is the standard adversarial loss. In practice, we adopt an approximate strategy by alternately updating the network weights and architecture parameters in a training batch to solve this problem.

It is worth noting that although a filter bank containing 8 operations is introduced during the search phase, this does not result in parameter redundancy in the final model. The atomic filters in set (e.g., Gabor, Sobel, Gaussian) are initialized with fixed geometric priors and remain frozen (non-trainable) during the search, which significantly reduces the number of learnable parameters compared to standard convolutions. Moreover, once the search concludes, a discrete pruning step is performed where only the atomic filter with the highest importance weight is retained for each layer, while other paths are discarded. This ensures that the final model deployed for inference is compact and efficient. Regarding theoretical stability, the convergence of this bi-level optimization is guaranteed by the continuous relaxation of the search space via Softmax, rendering the loss function differentiable with respect to the architecture parameters [35]. Furthermore, to ensure stability in the adversarial setting, we enforce a Lipschitz continuity constraint implicitly through gradient clipping. By bounding the gradient norms, we prevent the oscillation often observed in dynamic architecture search and theoretically guide the generator and discriminator towards a stable Nash equilibrium.

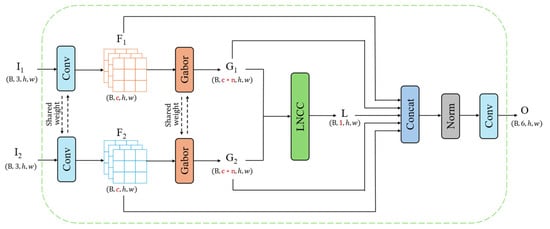

3.3. Feature Fusion Module Based on Gabor and Local Normalized Cross-Correlation (G-LNCC)

In the Hete-CD task, the most fundamental challenge lies in effectively comparing compare two completely different data sources. If the original heterogeneous image pairs are directly input into a standard encoder–decoder network, the network would require significant learning capacity to implicitly align the two modalities, which is not only inefficient but also highly susceptible to noise and imaging differences, leading to inadequate feature extraction results. To proactively bridge this semantic gap before the data enter the main network, we design a plug-and-play G-LNCC feature fusion module (the Gabor and local normalized cross-correlation fusion module) as a critical preprocessing component for the generator network, whose detailed architecture is shown in Figure 4. This module is aimed at transforming unstable raw pixel information into a shared feature space that is more robust to modality differences. The core idea is to extract and compare the more robust common features between the two modalities—texture and local structure features. To this end, we first use Gabor filters to process the two heterogeneous images separately. As excellent multiscale, multidirectional texture analysis tools, Gabor filters can capture underlying patterns that are independent of specific pixel values, such as the arrangement of buildings and the shape of vegetation. The real kernel function of a two-dimensional Gabor filter can be obtained by multiplying a Gaussian function by a cosine plane wave, which is defined as follows:

where , and . The parameters in the formula control the characteristics of the filter: is the wavelength of the cosine function, is the direction of the parallel stripes, is the phase shift, is the standard deviation of the Gaussian envelope, and is the spatial aspect ratio. By constructing a filter bank consisting of multiple Gabor kernels with different values, we can extract a comprehensive set of multidirectional texture feature maps from each input image. To ensure reproducibility, the hyperparameters for the Gabor filter bank were set as follows: the kernel size is , the number of orientations is , the wavelength is , the standard deviation is , the spatial aspect ratio is , and the phase offset is . For the Local Normalized Cross-Correlation (LNCC) calculation, we utilized a local window size of and a stride of 1 to maintain the spatial resolution of the feature maps.

Figure 4.

The architecture of the G-LNCC mechanism.

After obtaining the Gabor texture feature map, we further use local normalized cross-correlation (LNCC) to calculate the structural similarity between the spatially corresponding neighborhoods of the two texture maps. LNCC measures the linear correlations of local patterns and is insensitive to absolute brightness differences, making it highly suitable for comparing heterogeneous images. For two windows centered on a pixel , the LNCC values of the Gabor feature blocks and within these windows are calculated as follows:

where and are the mean values of the features within the two windows and is a minimum value that is used to prevent the denominator from being zero. This formula essentially calculates the cosine similarity between two centered feature vectors, with values ranging from , effectively measuring their structural consistency.

Finally, we concatenate the following feature maps: the original features , the multidirectional Gabor texture features , and the LNCC structural similarity map () to form a highly condensed input tensor :

This tensor is then passed through a fusion block consisting of a 1×1 convolution layer followed by Batch Normalization and ReLU activation. This learnable projection layer automatically re-weights the concatenated features and aligns their scales, generating the final fusion features , providing a high-quality, information-rich input for precise change detection in the encoder–decoder network of the main network.

3.4. Geometric Structure-Based Collaborative Supervision Loss (GSCS Loss)

Traditional segmentation tasks often involve the use of a single pixel-level loss function, such as the binary cross-entropy loss (BCE). This loss typically focuses only on pixel-level classification accuracy while ignoring the structural integrity and spatial continuity that change regions should have as a whole. This strategy has obvious shortcomings in complex Hete-CD tasks. 1) Blurred boundaries: The loss function treats all pixels equally, resulting in smooth transitions at the edges of changing regions instead of the clear boundaries expected for geographical entities. 2) Structural distortions: The model may generate a large number of isolated “salt-and-pepper noise” points or fragmented patches that do not conform to geographical spatial patterns and lack structural realism.

To address these issues, we propose a geometric structural collaborative supervision loss (GSCS loss). This loss function ensures that the generator () is subject to comprehensive and complementary constraints during the optimization process. It is defined as the weighted sum of three independent components:

Here, is the pixel-level region loss, is the edge consistency loss, and is the global structural adversarial loss. and are hyperparameters for balancing the various losses. This set of loss functions synergistically constrains the solution space of the model from different geometric and structural levels: focuses on the accuracy of regions, reinforces the contours of boundaries, and ensures the overall structural authenticity of the generated variation images from a global perspective.

: To simultaneously ensure high pixel-level classification accuracy and region-level overlap, we adopt a joint loss function combining the BCE and IoU losses (BCEIoULoss). This combination maintains pixel-wise fidelity while effectively mitigating the severe class imbalance inherent in change detection, thereby preventing the model from producing biased, background-only predictions. It is composed of the binary cross-entropy loss () and the intersection-over-union ratio loss ():

where and represent the true labels and predicted probabilities of pixel , respectively; is the total number of pixels; is the minimum value for preventing the denominator from being zero; and provides a robust segmentation foundation for the model.

: To obtain clear change boundaries, we introduce a gradient consistency loss. Geometric structures, unlike pixel intensities, exhibit modality invariance across heterogeneous sensors. By penalizing gradient discrepancies using the Sobel operator, the model can effectively suppress boundary blurring and ensure sharp edge alignment, which is crucial for enhancing the robustness of Hete-CD. This loss is obtained by calculating the L1 distance between the generated change map and the gradient map (i.e., edge map) of the ground truth. The gradient map is generated using the Sobel operator . The loss is defined as follows:

where is the input image pair, is the output of the generator, is the sigmoid function, and is the ground truth. This loss term acts as an explicit regularization term, specifically penalizing predictions with blurry boundaries, with a focus on boundary accuracy.

: To address the issue of structural realism encountered in the final generated change maps, we introduce an adversarial loss. The standard static losses often lead to over-smoothed results, while dynamic adversarial supervision compels the generator to capture high-frequency details and maintain global structural realism, ensuring the generated maps follow the intrinsic distribution of the ground truth. By training a discriminator to distinguish between the real change maps (from ) and the change maps generated by the generator (), we force to learn the intrinsic data distribution of the real change maps. The adversarial loss of the generator is aimed at maximizing the probability of the discriminator making a mistake and is defined as follows:

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Introduction

4.1.1. Datasets

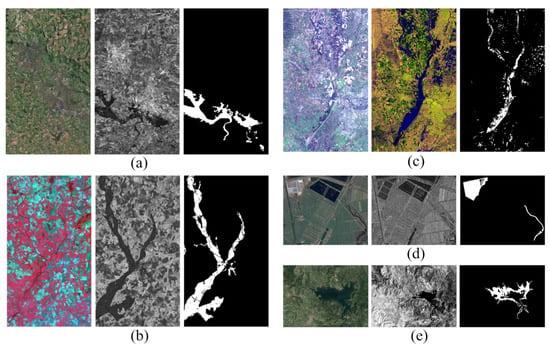

Our experiments utilize five heterogeneous remote sensing image datasets: Gloucester I, Gloucester II, California, Shuguang, and Italy. As shown in Table 1, these datasets cover different sensor types, image sizes, geographical regions, and change types, providing important experimental benchmarks for researchers.

Table 1.

Dataset Summary.

Gloucester I: As shown in Figure 5a, this dataset [18] recorded a flood event in the Gloucester region. Optical images were captured by the QuickBird 2 satellite (DigitalGlobe, Westminster, CO, USA) in July 2006, and SAR images were acquired by the TerraSAR-X satellite (Airbus Defence and Space, Friedrichshafen, Germany) in July 2007. The change area in this dataset was generated through manual annotation and is primarily used for flood disaster-based change detection research.

Figure 5.

All the datasets used in the paper. (a) Gloucester I. (b) Gloucester II. (c) California. (d) Shuguang. (e) Italy.

Gloucester II: As shown in Figure 5b, this dataset also originates from the Gloucester region and describes the floods that occurred between 1999 and 2000. Optical imagery was acquired by the SPOT satellite (CNES/Airbus, Toulouse, France) in September 1999, and SAR imagery was acquired by the ERS-1 satellite (European Space Agency, Paris, France) in November 2000. This dataset was used in the IEEE GRSS Data Fusion Competition [45] and is a classic dataset for Hete-CD.

California: As shown in Figure 5c, this dataset recorded flood events in California [46], including three-band SAR images (VV, VH, and their ratio) acquired by the Sentinel-1A satellite (European Space Agency, Paris, France) and optical images acquired by the Landsat 8 satellite (USGS, Reston, VA, USA). The dataset covers the same area in Sacramento County, Yuba County, and Sutter County, California, where floods caused changes in the region. This dataset provides rich data support for processing the multiband SAR images and serves as an important platform for testing multisource data processing capabilities.

Shuguang: As shown in Figure 5d, this dataset includes optical and SAR images acquired before and after construction activities and river changes occurred. The optical images were acquired by Google Earth(v7.3, Google LLC, Mountain View, CA, USA) in September 2012, and the SAR images were obtained by the Radarsat-2 satellite (MDA, Richmond, BC, Canada) in June 2008. The image dimensions are 419 × 342, making them suitable for studying surface changes caused by anthropogenic activities.

Italy: As shown in Figure 5e, this dataset is sourced from the work of [4]. Both images were acquired by the Landsat 5 satellite (USGS, Reston, VA, USA), depicting a 412 × 300-pixel area. The near-infrared (NIR)-band image was acquired in September 1995, while the RGB-band image was captured in July 1996 from the same area. The changes observed between the two images reflect the aftermath of a lake flood in Italy.

4.1.2. Implementation Details

All the experiments in this study were conducted using the PyTorch 1.8 deep learning framework on servers equipped with NVIDIA GPUs. All the datasets used included dual-phase RGB images and corresponding single-channel binary labels. For each dataset, the large-scale images were first partitioned into five spatially non-overlapping blocks to ensure strict geographical isolation. To report robust performance, we implemented a 5-fold cross-validation scheme by randomly assigning these blocks to the training, validation, and test sets at a ratio of 3:1:1 for each experimental run. For the training and validation sets, if the widths and heights of the large images were not integer multiples of 256 pixels, they were filled to integer multiples using horizontal flipping and mirroring. Overlapping cropping was subsequently performed using a 256 × 256 sliding window and a sliding stride of 64. All preprocessing operations were executed independently within the boundary of each specific block. For the test set, the same cropping method as that employed for the training and validation sets was used. Specifically, we adopted a Center-crop Evaluation Strategy. Specifically, although the model performs inference on the full patch to preserve context, we strictly extracted only the central 128 × 128 region of the model’s output prediction for calculating quantitative metrics. This strategy is adopted to mitigate boundary artifacts in CNNs caused by zero-padding at the patch edges and to ensure that every pixel is evaluated with sufficient surrounding contextual information. Crucially, this data processing strategy was consistently applied across all comparative experiments to ensure fairness and prevent any potential data leakage from overlapping regions.

To ensure the reproducibility of the experimental results, all the experiments were conducted under a fixed random seed (seed = 42). Crucially, to ensure a strictly fair comparison, we utilized this fixed seed to generate deterministic data partition indices for the 5-fold cross-validation. These identical partition indices were applied across all comparison methods, guaranteeing that every model was trained and evaluated on the exact same data subsets for each fold. This rigorous control eliminates performance variations caused by differences in data distribution. Furthermore, the trade-off hyperparameters in the loss function were set to and . To ensure the statistical stability and reliability of the reported results, we conducted five independent trials for all comparative experiments and ablation studies. All quantitative metrics presented in the subsequent sections are the mean values calculated from these five trials. The generator adopted the UNet architecture, with a G-LNCC fusion module integrated into the front end. The discriminator consisted of five searchable DFCS units stacked together, with its architecture dynamically evolving during the training process. We employed an alternating optimization strategy to train the generator and the adaptive discriminator over 100 epochs with a batch size of 16. To ensure stability, three independent Adam optimizers were configured: one for the generator weights with an initial learning rate of 1 × 10−3, one for the discriminator network weights with a learning rate of 2.5 × 10−4, and one for the discriminator architecture parameters with a learning rate of 3 × 10−4. Unlike traditional two-stage NAS methods that separate search and retraining, we adopted an online evolution strategy. In this one-stage framework, the supernet weights are shared throughout the search process. Within each training iteration, the optimization proceeds in two distinct steps using a first-order approximation. First, the discriminator is updated: the network weights and architecture parameters are optimized simultaneously to minimize the discrimination loss, allowing the architecture to dynamically adapt to the current generator state. Second, the generator parameters are updated to minimize the joint segmentation and adversarial loss. The specific process is shown in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: Optimization Procedure of the Proposed DFCS Framework | |||

| Input: Training dataset D, max epochs Nepochs, learning rates ηG, ηw, ηα. | |||

| Output: Optimized Generator θG* and Discriminator architecture α*. | |||

| 1 | Initialize generator weights θG, discriminator weights w, and architecture parameters α; | ||

| 2 | Initialize temperature T ← 5.0; | ||

| 3 | while epoch < Nepochs do | ||

| 4 | Update temperature T via cosine annealing schedule (Equation (1)); | ||

| 5 | for each mini-batch (xT1, xT2, ygt) in D do | ||

| 6 | // Generate prediction | ||

| 7 | ŷ = G(xT1, xT2; θG); | ||

| 8 | // Phase 1: Update Discriminator (Alternating) | ||

| 9 | Calculate discrimination loss LD using Equation (3); | ||

| 10 | Update weights: w ← w - ηw ∇w LD; | ||

| 11 | Update topology: α ← α - ηα ∇α LD; | ||

| 12 | // Phase 2: Update Generator | ||

| 13 | Calculate joint loss | ||

| 14 | Update generator: θG ← θG - ηG ∇θG LG; | ||

| 15 | end | ||

| 16 | end | ||

| 17 | Pruning: Derive final architecture by selecting filters with argmax(α); | ||

To stabilize the search process of the DFCS and bridge the gap between the continuous search space and the discrete architecture, we introduced a cosine temperature annealing mechanism. The temperature controls the sharpness of the softmax distribution in Equation (13). A higher temperature facilitates exploration by smoothing the distribution, while a lower temperature enforces exploitation by sharpening it towards a one-hot distribution. The temperature is decayed according to the following cosine schedule:

where is the initial temperature set to 5.0, is the final temperature set to 0.5, is the current training epoch, and is the total number of epochs. This strategy allows for broad exploration in the early stages and precise convergence to a definitive filter combination in the later stages.

To mitigate gradient explosion and ensure the stability of the bi-level optimization process, we explicitly applied gradient clipping with a norm threshold of 0.5 during backpropagation. Additionally, to further stabilize the adversarial training dynamics, a warm-up strategy was employed for the generator during the initial training epochs. Experimental observations indicate that the combination of these strategies effectively prevents training collapse, allowing the loss functions of both the generator and discriminator to converge smoothly.

4.1.3. Evaluation Metrics

We use the following metrics to conduct a comprehensive evaluation: precision, recall, the F1 score, the intersection over union (IoU), and overall accuracy. Precision reflects the proportion of pixels that actually changed among all pixels detected as changed, indicating the proportion of correct predictions in the “positive class” (change class). A higher precision level indicates that the algorithm can effectively distinguish between changed pixels and avoid misidentifying unchanged areas as changed areas. Recall measures the proportion of all pixels that actually changed and were detected as changed. A high recall rate means that the model has a low false-negative rate and can detect more changed pixels from real data. The F1 score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, balancing the differences between the two metrics. It comprehensively evaluates the accuracy and comprehensiveness of the model and is particularly suitable when a certain balance is observed between precision and recall. The overall accuracy (OA) is among the most commonly used evaluation metrics and represents the proportion of correctly classified pixels out of the total number of pixels, reflecting the overall performance of the model.

4.2. Comparison Experiments

To verify the effectiveness of our DFCD-Net, we compared it against eight state-of-the-art methods representing diverse technical paradigms. These methods are categorized into four groups in Table 2: (1) Classification-based methods like PCC [16]. The PCC method first classifies the input dual-phase data to obtain category information and detect changes by comparing the classification maps. (2) CNN-based coupled networks such as SCCN [21]. The SCCN converts heterogeneous images into a common latent domain in the coupling layer to obtain difference images. (3) Generative-based frameworks including CGAN [26], CAE [47], MTCDN [28], and C3D [48]. CAE draws inspiration from the cyclic consistency paradigm and aligns the encoder to the encoding space to achieve this goal; the CGAN is a classic image transformation-based change detection task; the MTCDN integrates image translation and change detection modules through an end-to-end framework; and C3D employs bidirectional image translation and dual contrastive learning methods, constructing comparable feature representations and leveraging multiscale contextual feature similarity metrics to effectively address cross-modal information imbalances. (4) Feature description methods such as IRG-McS [49] and SRF [50]. They convert images into the same difference domain, calculate their forward and backward differences, and obtain the same structural information. Detailed classification of comparison methods is shown in Table 2. This selection provides a comprehensive benchmark for evaluating Hete-CD performance under various cross-modal challenges.

Table 2.

Summary of Comparison Methods.

4.2.1. Quantitative Analysis

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of our proposed method (Ours), we compared it with the aforementioned eight state-of-the-art Hete-CD methods on five public datasets. The experimental results are shown in Table 3. As shown in the table, our method achieved the best performance in terms of both the F1 score (F1) and overall accuracy (OA) metrics on all five datasets, fully demonstrating the superiority and generalizability of our proposed framework.

Table 3.

Quantitative measures of the CD results obtained on different datasets (Bold values indicate the best performance for each metric).

Specifically, our method performed exceptionally well in the Gloucester I and Gloucester II scenarios, which primarily involved flood-related changes. On the Gloucester I dataset, our method achieved an F1 score of 93.7%, outperforming the second-best C3D method (91.8%) by 1.9 percentage points. Notably, although the SRF method achieved the highest precision (94.9%) on this dataset, its recall rate (69.4%) was significantly lower than that of our method (97.6%), indicating that the SRF method sacrifices a large number of missed detections to achieve high precision. In contrast, our method achieved near-complete change region detection while maintaining high precision, thereby attaining the best F1 score. On the Gloucester II dataset, the advantages of this method were even more comprehensive, with both the F1 score (95.0%) and OA (98.8%) significantly exceeding those of all the comparison methods. In the Shuguang dataset, the scene includes two different types of changes—buildings and rivers—which impose greater demands on the comprehensive recognition capabilities of models. Our method achieved an F1 score of 90.1% on this dataset. Although the recall rate of C3D (91.5%) was slightly higher than that of our method (88.8%), the precision rate of our method (91.3%) far exceeded that of C3D (85.4%), demonstrating stronger false-positive suppression capabilities and thus outperforming C3D in terms of overall performance.

4.2.2. Qualitative Analysis

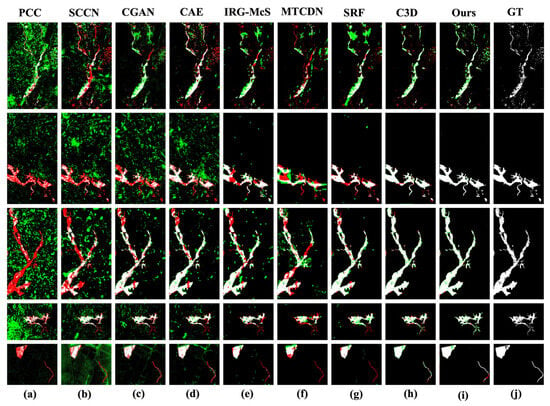

To intuitively evaluate the performance of the proposed method, Figure 6 shows a comparison among the visual results derived from different change detection methods on five representative heterogeneous datasets. These datasets cover various change scenarios, including floods, construction work, and lake inundation, as described previously. In the figure, green pixels represent false negatives, and red pixels represent false alarms.

Figure 6.

Visual comparison among the change maps generated by different methods on five datasets. (a) PCC. (b) SCCN. (c) CGAN. (d) CAE. (e) IRG-McS. (f) MTCDN. (g) SRF. (h) C3D. (i) Ours. (j) Ground truth.

The first three rows show the detection results produced in different flood inundation scenarios. These scenarios share the common characteristics of irregularly shaped change regions and complex boundaries. The traditional PCC method (a) failed to effectively handle the non-linear radiometric differences between the heterogeneous images, resulting in significant salt-and-pepper noise and failing to identify valid change areas. The SCCN (b) and CGAN (c) suppressed noise to some extent but exhibited severe “holes” and discontinuities in their detection results. These fragmentation issues correspond to the structural distortions highlighted in Section 1, where the models fail to preserve the spatial integrity of the flood extent. The CAE (d), MTCDN (f), and C3D (h) methods yielded relatively complete results but still contained significant numbers of red false-positive pixels, particularly in background areas. IRG-McS (e) and SRF (g) performed reasonably well in terms of suppressing false positives but exhibited large-scale false negatives in some scenarios (e.g., the second row). In contrast, our method (i) obtained the best visual results in all flood scenes. It not only accurately delineated the main flooded areas but also preserved fine boundary details, while the background areas remained extremely clean, with false positives and false negatives effectively controlled. This is attributed to our G-LNCC module, which enhanced the robustness of the network to the modal differences between water and land by fusing texture and structural information; simultaneously, the edge consistency constraints contained in the GSCS loss ensured sharp and complete flood boundaries.

The fourth row shows a complex scene with building construction and river channel changes. In such scenes, the performance of most comparison methods significantly deteriorated. They could either detect only one type of change or produce a large number of red false-positive pixels in both change regions, and their ability to preserve both building contours and river channel connectivity were unsatisfactory. C3D(h) performed relatively well, but the building edges it detected were relatively blurry. This exemplifies the blurred change boundaries challenge, where fixed discriminators struggle to enforce sharp geometric contours in complex heterogeneous transitions. Our method once again demonstrated its superiority, not only with the fewest false positives but also by clearly delineating both the geometric contours of buildings and the linear structures of rivers. This fully validates the critical role of our DFCS-based adaptive discriminator in adversarial training tasks, as it dynamically evolves its network structure to provide the generator with more precise and stable supervision signals, enabling it to learn more realistic, multimodal geographical structure distributions.

The fifth row shows the results obtained in a lake flood scenario, which are characterized by large change areas and relatively homogeneous internal structures. In this scenario, all the comparison methods struggled to obtain satisfactory results, with most methods producing dense false positives (red pixels) around the lake. However, our method (i) was the only one that could effectively eliminate background noise while accurately capturing the flooded area of the lake. This further highlights the effectiveness of our overall framework, demonstrating that by combining feature enhancement at the front end, refined loss supervision during the process, and an adaptive discriminator at the back end, our model can systematically improve its change detection capabilities across various complex scenarios.

4.3. Ablation Experiments

4.3.1. DFCS

To validate the effectiveness of our proposed differential filter-based composition search (DFCS) strategy in terms of improving the performance of discriminators, we designed a series of rigorous ablation experiments.

We first compared the discriminator using the DFCS strategy with two baseline architectures: one was 3 × 3conv, where all the searchable layers used standard 3 × 3 convolutions, representing a typical human design; the other was random, where one or more “atomic filters” were randomly replaced with generic 3 × 3 convolution kernels in the final optimal architecture (Ours NAS). As shown in Table 4, the experimental results clearly demonstrate the superiority of the DFCS strategy. On both the Gloucester I and Gloucester II datasets, our method outperformed both baselines across all the core metrics. Compared with the standard 3 × 3conv architecture, our method achieved a 2.0-percentage-point improvement in the F1 score on the Gloucester I dataset and a 10.3-percentage-point improvement on the Gloucester II dataset, demonstrating that the adaptively searched architecture significantly outperforms fixed generic designs.

Table 4.

Ablation results obtained with respect to the DFCS. The best results are highlighted in bold.

Note the performance of the random architecture. After the optimal architecture was randomly perturbed, its performance decreased sharply, with the F1 score even falling far below that of the simpler 3 × 3conv baseline. This phenomenon precisely confirms the notion that the architecture discovered by the DFCS is a highly optimized and precise combination whose high performance does not stem from the simple accumulation of operations but rather from the specific synergistic effects of filters at different levels. Any arbitrary modification would disrupt this balance tailored for the specific task of interest, leading to a significant decline in performance. This fully demonstrates the intelligence and efficiency of the DFCS process, which can find a truly optimal structure for the Hete-CD task.

To further investigate the value of the filter combinations discovered by the DFCS, we conducted replacement experiments. Owing to the random nature of the experiments, the results were averaged over five trials. As shown in Table 5, we replaced some of the “atomic filters” contained in the optimal architecture obtained through the final search with generic 3 × 3 convolution kernels. The experimental results show that even replacing just one or two of the selected dominant filters led to a significant decrease in performance, particularly in terms of precision (Prec) and the F1 score. These results validate the fact that the specific filter combinations learned by the DFCS are highly task-specific and irreplaceable.

Table 5.

Ablation results obtained with respect to the DFCS. The best results are highlighted in bold.

4.3.2. G-LNCC

To systematically evaluate the effectiveness of the G-LNCC feature fusion module proposed in this paper and explore the synergistic effects of its internal components—the Gabor and local normalized cross-correlation (LNCC)—we conducted a series of detailed ablation experiments. The experiments used a baseline model that did not include any front-end fusion modules (i.e., the original images were directly input into UNet) as the baseline and separately tested the performance of the Gabor filter, LNCC, and the complete G-LNCC module when integrated individually or together.

The experimental results are shown in Table 6. The performance of the baseline model initially improved when the Gabor filter was introduced alone. For example, on the Gloucester II dataset, the F1 score improved from 0.923 to 0.928. This finding indicates that the multiscale, multidirectional texture features extracted by the Gabor filter provided the model with underlying pattern information that was more robust to modal differences, effectively reducing the difficulty of conducting a direct comparison between heterogeneous data. When LNCC was introduced alone, the performance of the model also improved significantly, with the F1 score increasing to 0.925 on the Gloucester I dataset. This phenomenon is attributed to the ability of LNCC to measure local structural similarity, which is insensitive to the common non-linear radiation differences between optical and SAR images, thereby enabling structural information contained in varying regions to be more accurately matched. When Gabor and LNCC worked together to form a complete G-LNCC module, the performance of the model reached its optimal state, with F1 scores of 0.937 and 0.950 on the two datasets, respectively, which were significantly higher than those of any single component or baseline model. These results fully prove the important synergistic effect between the Gabor filter and LNCC.

Table 6.

Ablation results obtained with respect to G-LNCC. The best results are highlighted in bold.

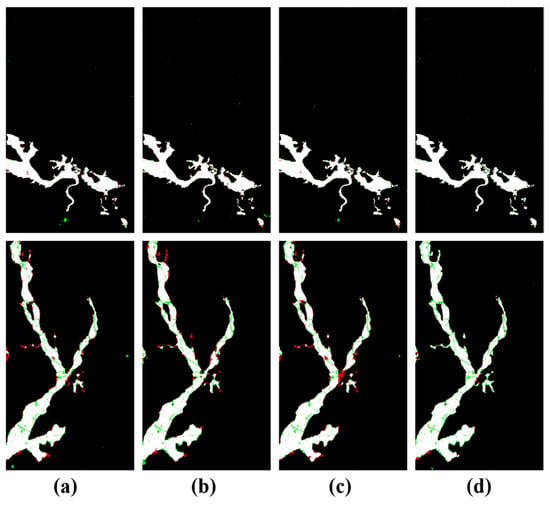

As shown in the visualization results presented in Figure 7, when conducting change detection in complex scenes, the monitoring results of the model using the proposed Gabor + LNCC module exhibited significantly reduced missed detections (red regions in the figure) and yielded similar or fewer “false detection areas” (green regions in the figure). This finding indicates that the proposed Gabor + LNCC module can help the model better identify and extract the same information from heterogeneous images, thereby improving the ability of the model to handle change detection tasks in complex scenes and reducing the false-negative rate.

Figure 7.

The results of an ablation experiment conducted with different modules on Gloucester I and Gloucester II. (a) Baseline (without Gabor and LNCC). (b) Only Gabor. (c) Only LNCC. (d) Proposed G-LNCC (BothGabor and LNCC). FP (red); FN (green).

4.3.3. GSCS Loss

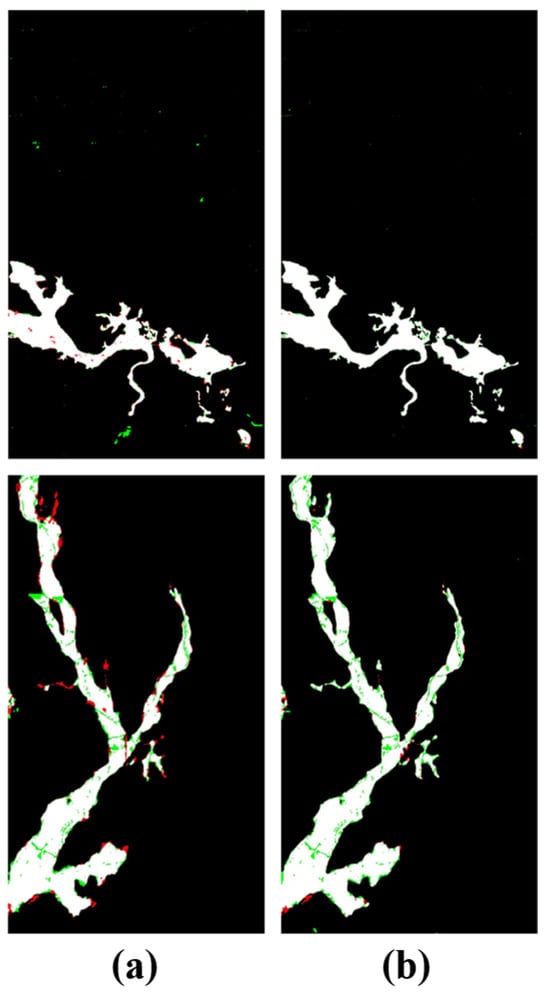

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed geometric structure-based collaborative supervision loss (GSCS loss), we conducted an ablation analysis on its key component—the edge consistency loss (Lbound, implemented using the Sobel operator).

The experiments first involved comparing the baseline model using only the pixel-level region loss (Lpixel, composed of the BCE and IoU losses) with the complete model incorporating the edge consistency loss. As shown in Table 7, adding the edge consistency loss (No. 2) to the baseline model (No. 1) significantly improved its performance on both datasets. Specifically, on the Gloucester I dataset, the F1 score improved from 0.921 to 0.937; on the Gloucester II dataset, the F1 score improved from 0.944 to 0.950. This performance gain is more intuitively demonstrated in the qualitative results. The detection results produced by the two models on the Gloucester II dataset are shown in Figure 8. (a) corresponds to the model using only the pixel-level loss, which contains a large number of false alarms (indicated by red pixels), especially at the edges of change areas and small features in the background. The data in (b) correspond to the model with the edge consistency loss, which significantly reduces the number of false alarms, makes the boundaries of change areas clearer and smoother, and keeps the background cleaner.

Table 7.

Ablation results obtained with respect to the GSCS loss. The best results are highlighted in bold.

Figure 8.

The results of an ablation experiment conducted with different loss functions on Gloucester I and Gloucester II. (a) Baseline (Only the BCE and IOU losses). (b) Proposed GSCS loss (Both Lpixel and Lbound). FP (red); FN (green).

We further investigated the sensitivity of the model performance to the structural weight hyperparameter . As summarized in Table 8, we evaluated within the range of . The experimental results reveal a consistent upward trend in all evaluation metrics as the weight increases, reaching peak performance at . From a dynamic optimization perspective, when is set to a lower value (e.g., ), the structural constraint is too weak to effectively guide the generator in aligning geometric edges across modalities, leading to blurred change boundaries. By increasing the weight to , the model achieves an optimal trade-off between pixel-level semantic accuracy and structure-level fidelity. At this scale, the gradient consistency loss provides sufficient supervision to sharpen edges without overwhelming the primary segmentation losses (BCE and IOU). Therefore, was selected as the optimal value to ensure robust geometric regularization throughout the training process.

Table 8.

Ablation results obtained with respect to the weight of the GSCS loss. The best results are highlighted in bold.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we address the critical challenges stemming from the significant modal differences and blurred change boundaries that are observed in heterogeneous remote sensing image change detection (Hete-CD) scenarios. We propose DFCD-Net, an adaptive adversarial learning framework built upon three core components: a G-LNCC module for robust cross-modal feature alignment, a DFCS strategy enabling the architecture of the discriminator to dynamically adapt, and a GSCS loss function to impose multidimensional, fine-grained supervision. Extensive experiments conducted on five public datasets validate the notion that our method outperforms various state-of-the-art models in terms of key metrics such as the F1 score, demonstrating a particular strength in generating change maps with structurally complete and sharply defined boundaries.

Despite its strong overall performance, the method exhibits slightly lower precision on certain datasets, such as Gloucester I, which is likely attributable not only to complex background textures but also to inherent data quality issues, specifically geometric distortions and annotation inconsistencies common in historical map data. These factors introduce label noise that challenges the model’s fine-grained boundary detection capabilities. Furthermore, we recognize the method’s limitations when applied to extreme modal differences, such as Optical–Infrared scenarios. While our G-LNCC module effectively aligns geometric structures, the fundamental physical disparity between thermal footprints and visual textures poses unique challenges that may require specialized thermal feature extraction. Future research will focus directly on these challenges. We plan to enhance the discriminative power of the model in the presence of label noise and extreme modal gaps by optimizing the weight distribution within the GSCS loss function and by incorporating modality-specific operators into the DFCS-based atomic filter library. Additionally, while the framework is highly effective, its operational efficiency can potentially be optimized. Therefore, exploring more streamlined search strategies and designing lighter-weight network architectures will be another key direction for future work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.L. and J.C. (Jie Chen 1); methodology, H.L.; software, H.L.; data curation, H.L.; writing—original draft preparation, H.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z., J.L., J.C. (Jie Chen 2), H.Z., W.Y. and L.S.; supervision, W.Y., J.C. (Jie Chen 2) and Z.H.; funding acquisition, J.C. (Jie Chen 1) and Z.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant U23B2007, National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 62471006, Anhui Provincial Science and Technology Tackling Key Problems Project, Low-Altitude Intelligent Connected Safety Technology Research and Development and Industrialization 202423h08050007 and National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grants 62201004.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Long Sun was employed by the company The Sun Create Electronics Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Huang, Q.; Jin, G.; Xiong, X.; Ye, H.; Xie, Y. Monitoring Urban Change in Conflict from the Perspective of Optical and SAR Satellites: The Case of Mariupol, a City in the Conflict between RUS and UKR. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Huang, H.; Li, X.; Zhao, M.; Benediktsson, J.A.; Sun, W.; Falco, N. Land Cover Change Detection With Heterogeneous Remote Sensing Images: Review, Progress, and Perspective. Proc. IEEE 2022, 110, 1976–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luppino, L.T.; Bianchi, F.M.; Moser, G.; Anfinsen, S.N. Remote sensing image regression for heterogeneous change detection 2018. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 28th International Workshop on Machine Learning for Signal Processing (MLSP), Aalborg, Denmark, 17–20 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Touati, R.; Mignotte, M.; Dahmane, M. Multimodal Change Detection in Remote Sensing Images Using an Unsupervised Pixel Pairwise-Based Markov Random Field Model. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2020, 29, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, R.; Du, C.; Chen, H.; Li, J. SUNet: Change Detection for Heterogeneous Remote Sensing Images from Satellite and UAV Using a Dual-Channel Fully Convolution Network. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, F.; Yang, W.; Peng, S.; Zhou, J. A Survey of Convolutional Neural Networks: Analysis, Applications, and Prospects. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 33, 6999–7019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial networks. Commun. ACM 2020, 63, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercier, G.; Moser, G.; Serpico, S.B. Conditional Copulas for Change Detection in Heterogeneous Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2008, 46, 1428–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prendes, J.; Chabert, M.; Pascal, F.; Giros, A.; Tourneret, J.-Y. A New Multivariate Statistical Model for Change Detection in Images Acquired by Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Sensors. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2015, 24, 799–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberga, V. Similarity Measures of Remotely Sensed Multi-Sensor Images for Change Detection Applications. Remote Sens. 2009, 1, 122–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Lei, L.; Li, X.; Tan, X.; Kuang, G. Patch Similarity Graph Matrix-Based Unsupervised Remote Sensing Change Detection with Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Sensors. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 59, 4841–4861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Lei, L.; Li, X.; Sun, H.; Kuang, G. Nonlocal patch similarity based heterogeneous remote sensing change detection. Pattern Recognit. 2021, 109, 107598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Lei, L.; Li, X.; Tan, X.; Kuang, G. Structure Consistency-Based Graph for Unsupervised Change Detection with Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 4700221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Troy, A.; Grove, M. Object-based Land Cover Classification and Change Analysis in the Baltimore Metropolitan Area Using Multitemporal High Resolution Remote Sensing Data. Sensors 2008, 8, 1613–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubea, K.; Menz, G. Monitoring Land-Use Change in Nakuru (Kenya) Using Multi-Sensor Satellite Data. ARS 2012, 1, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, L.; Xiang, Y.; You, H. A Post-Classification Comparison Method for SAR and Optical Images Change Detection. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2019, 16, 1026–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luppino, L.T.; Kampffmeyer, M.; Bianchi, F.M.; Moser, G.; Serpico, S.B.; Jenssen, R.; Anfinsen, S.N. Deep Image Translation with an Affinity-Based Change Prior for Unsupervised Multimodal Change Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 4700422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignotte, M. A Fractal Projection and Markovian Segmentation-Based Approach for Multimodal Change Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 58, 8046–8058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Feng, Y.; Hu, L.; Tapete, D.; Pan, L.; Liang, Z.; Cigna, F.; Yue, P. A domain adaptation neural network for change detection with heterogeneous optical and SAR remote sensing images. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 109, 102769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Li, G.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.-P.; He, Y. Change Detection in Heterogeneous Optical and SAR Remote Sensing Images Via Deep Homogeneous Feature Fusion. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2020, 13, 1551–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Gong, M.; Qin, K.; Zhang, P. A Deep Convolutional Coupling Network for Change Detection Based on Heterogeneous Optical and Radar Images. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2018, 29, 545–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Q.; Shi, Y.; Guo, J.; Ouyang, C.; Zhu, X.X. UCDFormer: Unsupervised Change Detection Using a Transformer-Driven Image Translation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5619917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Lei, L.; Li, Z.; Kuang, G.; Yu, Q. Detecting changes without comparing images: Rules induced change detection in heterogeneous remote sensing images. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2025, 230, 241–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Lei, L.; Li, Z.; Kuang, G. Similarity and dissimilarity relationships based graphs for multimodal change detection. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 208, 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-J.; Dobigeon, N.; Chabert, M.; Wang, D.-C.; Huang, T.-Z.; Huang, J. CD-GAN: A robust fusion-based generative adversarial network for unsupervised remote sensing change detection with heterogeneous sensors. Inf. Fusion 2024, 107, 102313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Gong, M.; Zhan, T.; Yang, Y. A Conditional Adversarial Network for Change Detection in Heterogeneous Images. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2019, 16, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Du, Z.; Huang, Y.; Tan, Z. A deep translation (GAN) based change detection network for optical and SAR remote sensing images. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 179, 14–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Li, X.; Miao, J.; Huang, Y.; Shen, H.; Zhang, L. Concatenated Deep-Learning Framework for Multitask Change Detection of Optical and SAR Images. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 719–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Geng, J.; Jiang, W. Multidomain Constrained Translation Network for Change Detection in Heterogeneous Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5616916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sghaier, M.O.; Hadzagic, M.; Yu, J.Y.; Shton, S.; Shahbazian, E. Leveraging Generative Deep Learning Models for Enhanced Change Detection in Heterogeneous Remote Sensing Data. In Proceedings of the 2024 27th International Conference on Information Fusion (FUSION), Venice, Italy, 8–11 July 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, H.; Ouyang, M.; Zhao, C.; Mathiopoulos, P.T. Heterogeneous Image Change Detection with Transfer Learning-Based Multi-Layer Convolutional Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2024—2024 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Athens, Greece, 7–12 July 2024; pp. 8840–8843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Huang, H.; Sun, W.; Lei, T.; Benediktsson, J.A.; Li, J. Novel Enhanced UNet for Change Detection Using Multimodal Remote Sensing Image. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2023, 20, 2505405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsken, T.; Metzen, J.H.; Metzen, J.; Hutter, F. Neural Architecture Search: A Survey. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1808.05377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoph, B.; Le, Q.V. Neural Architecture Search with Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1611.01578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Simonyan, K.; Yang, Y. DARTS: Differentiable Architecture Search. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1806.09055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Chang, S.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Z. AutoGAN: Neural Architecture Search for Generative Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 3223–3233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Chen, Y.; Liu, S.; Tan, Z.; Yan, S. AdversarialNAS: Adversarial Neural Architecture Search for GANs. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 5679–5688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.; Joo, C. AutoGAN-DSP: Stabilizing GAN architecture search with deterministic score predictors. Neurocomputing 2024, 573, 127187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulakurthi, P.R.; Mozaffari, M.; Dianat, S.A.; Rabbani, M.; Heard, J.; Rao, R. Enhancing GAN Performance Through Neural Architecture Search and Tensor Decomposition. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2024—2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 14–19 April 2024; pp. 7280–7284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Yang, Y.; Liu, S.; Lin, Q.; Tan, K.C. SCGAN: Sampling and Clustering-Based Neural Architecture Search for GANs. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. Intell. 2025, 9, 3626–3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Liu, X.; Lei, Y. SAR Images Change Detection Based on Self-Adaptive Network Architecture. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2021, 18, 1204–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]