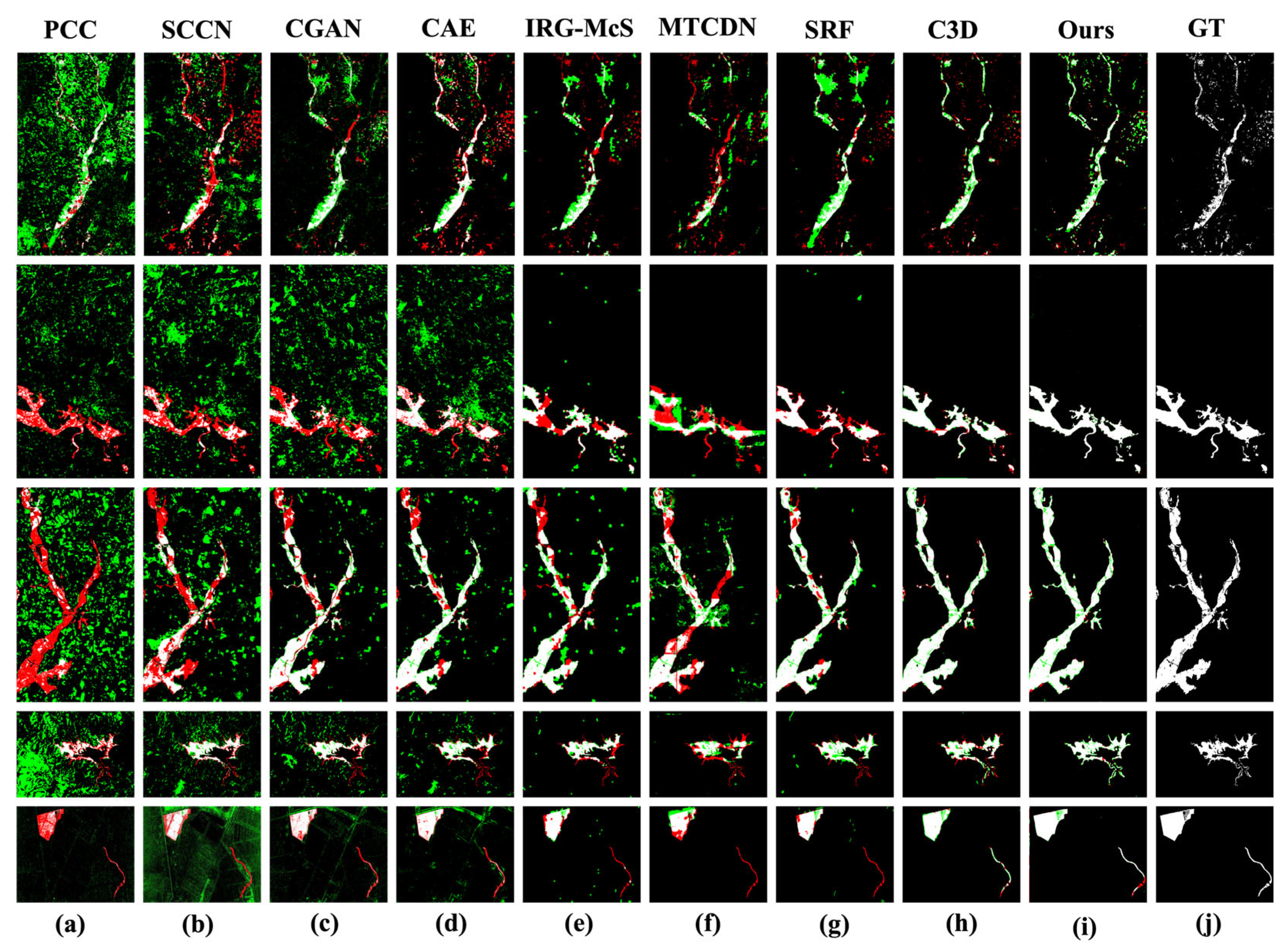

3.2. Differentiable Filter-Based Combination Search Strategy (DFCS)

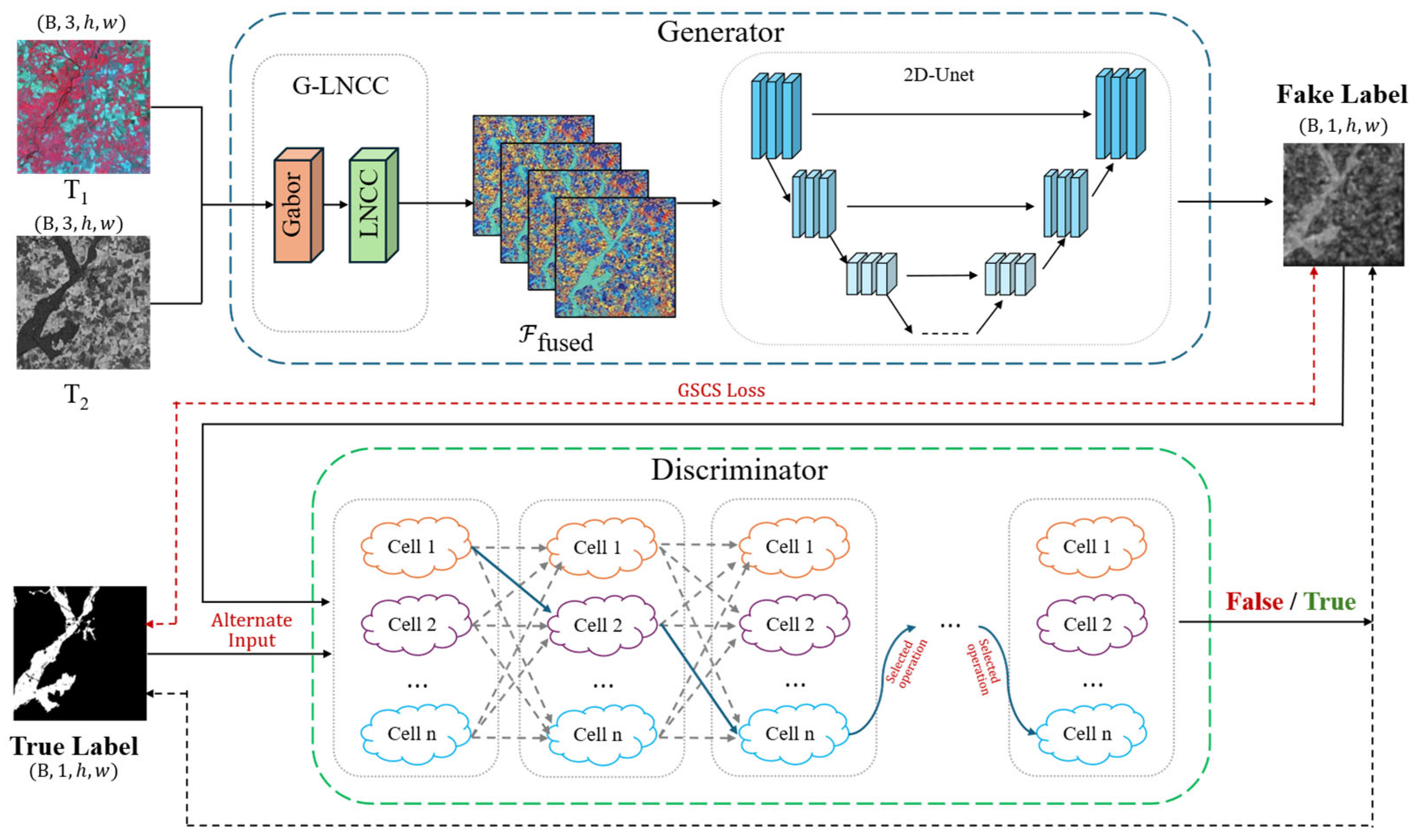

Currently, the field of heterogeneous image change detection faces a core challenge: the existing network models typically employ fixed, manually designed network architectures when processing different types of image pairs (e.g., optical and SAR images). This approach suffers from significant empirical biases and is prone to becoming stuck in local optima. Particularly in frameworks based on generative adversarial networks (GANs), the structure of the discriminator is critical for performing feature alignment and change detection, yet its design is constrained by time-consuming and suboptimal manual parameter tuning processes. In our adversarial learning framework, the effectiveness of the adversarial loss Ladv is highly dependent on a robust discriminator D. However, for complex Hete-CD tasks, a fixed, manually designed discriminator architecture is likely to be suboptimal. To address this issue, we propose the differential filter-based composition search (DFCS) strategy. The core of this strategy lies in abandoning the traditional approach of selecting from a set of predefined macro-operations. Instead, the discriminator learns to dynamically compose convolution kernels for each of its layers during training, thereby constructing a highly task-adaptive supervisory structure.

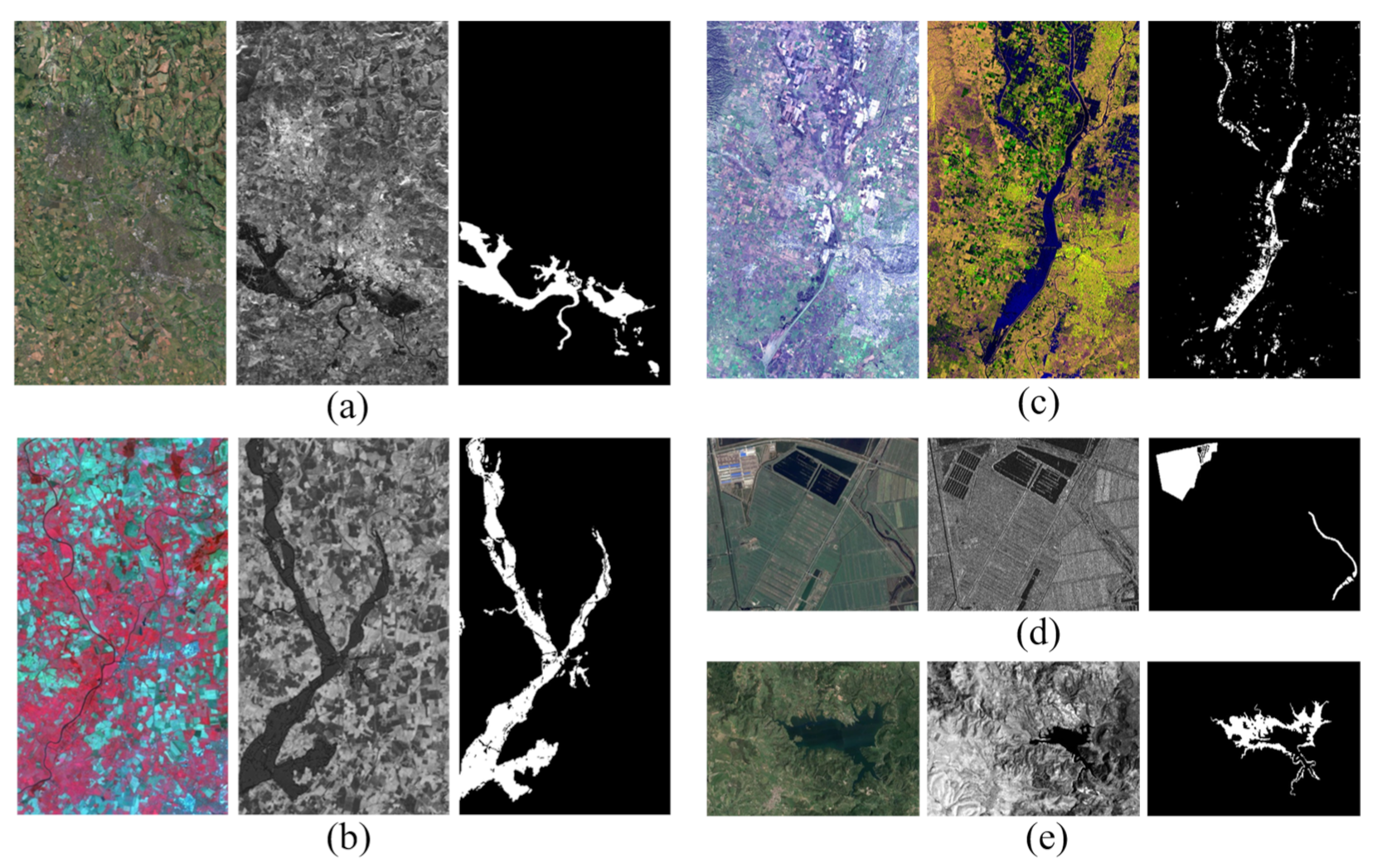

Any complex convolution kernel used for image analysis purposes can be approximated by the linear combination of a set of more basic “atomic filters” (atomic filters) [

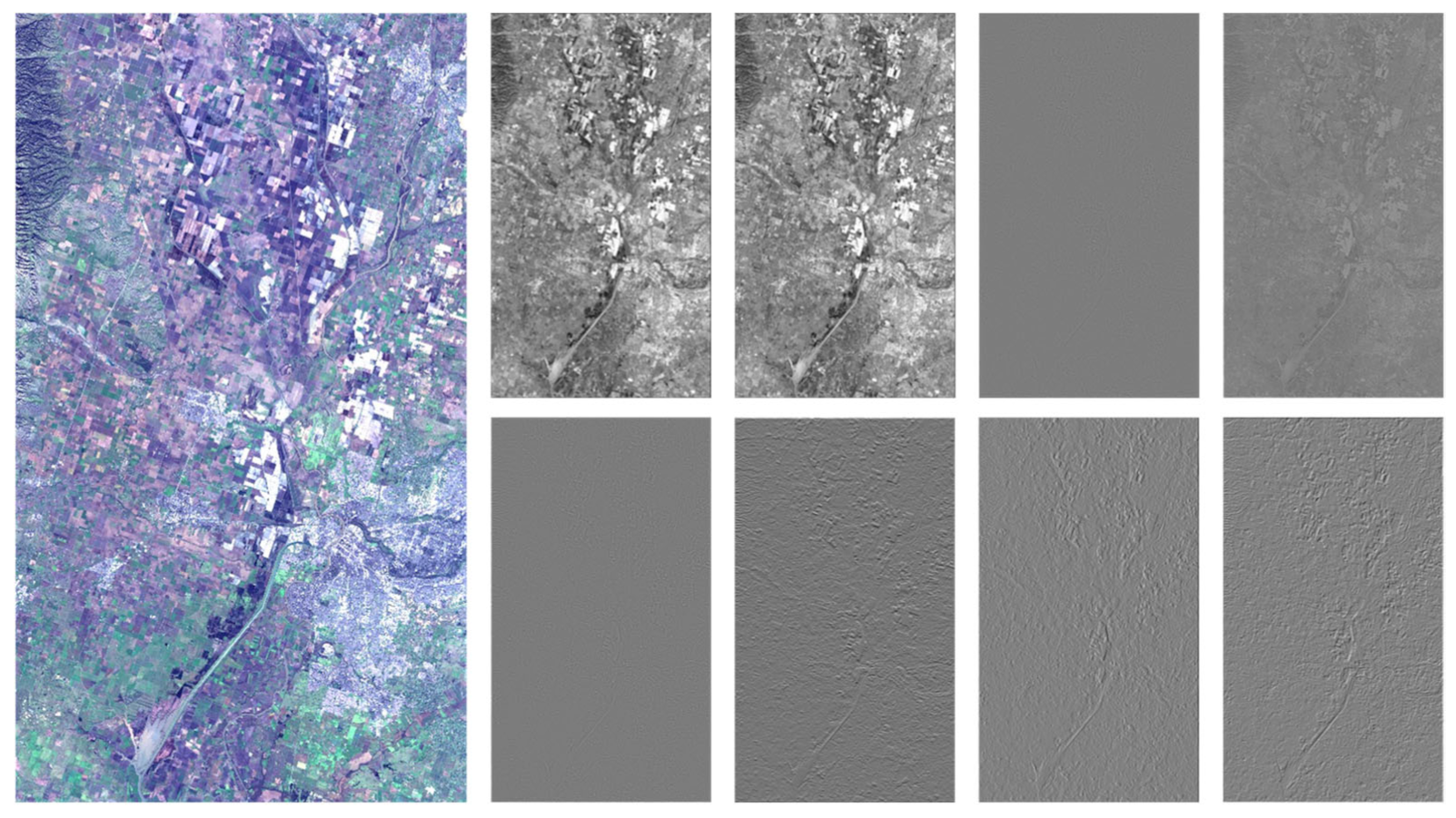

44]. To specifically address the significant modal discrepancies in Hete-CD, such as speckle noise in SAR and non-linear radiometric distortions, we constructed a curated library B = {K

1, …, K

M} containing M = 8 fixed, non-trainable atomic filters. Motivated by the specific challenges of heterogeneous data alignment, these filters are categorized into three distinct functional groups. First, for noise suppression, a Gaussian filter (3 × 3) is included to suppress high-frequency noise; this is essential for mitigating the coherent speckle noise prevalent in SAR imagery, preventing the discriminator from overfitting to sensor-specific artifacts. Second, regarding structural alignment, we employ three edge-sensitive operators: two Sobel filters (horizontal and vertical) and one Laplacian of Gaussian filter. Unlike raw pixel intensities which vary drastically across sensors, geometric edges and blob-like structures are modality-invariant, allowing these operators to enforce physical boundary consistency across modalities. Third, for texture representation, four Gabor filters with orientations of 0, 45, 90, and 135 degrees are utilized. These are designed to capture the anisotropic texture patterns and directional structures of man-made objects, which serve as robust indicators of change regardless of spectral appearance. By dynamically synthesizing weights for these primitives, the discriminator can adaptively construct the optimal receptive field for diverse land cover types. The filtering effects of the utilized atomic filters are shown in

Figure 2.

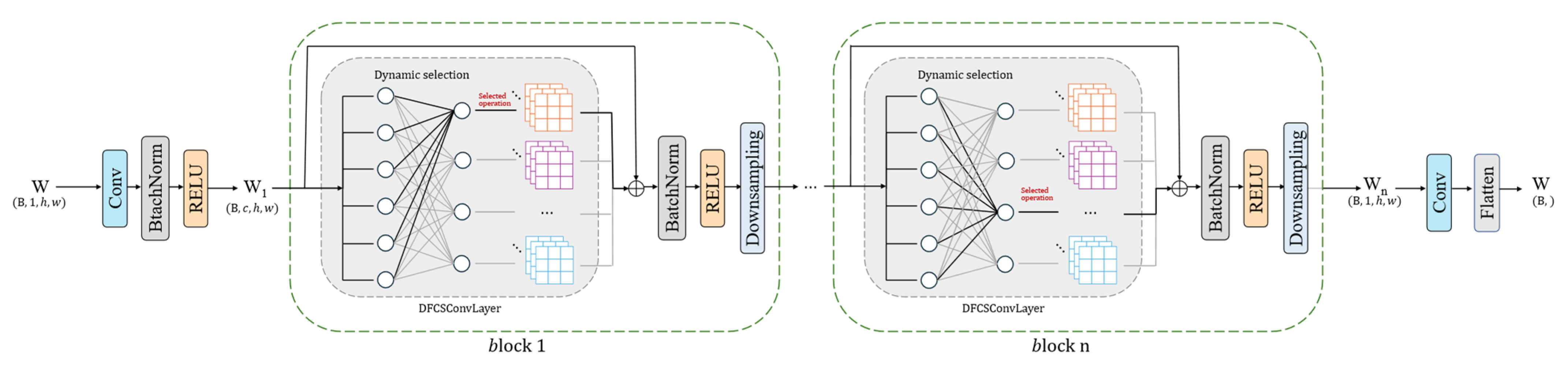

The framework diagram of the differentiable filter-based combination search architecture is shown in

Figure 3. For the

th searchable convolution layer (DFCS Conv layer) in the discriminator, we define a set of learnable architecture parameters

, where

represents the number of channels. These parameters are converted into normalized combination weights

via a softmax function with a temperature of

:

where

represents the contribution of the

th atomic filter in the

th channel of the

th layer. Subsequently, the

th dynamic convolution kernel

of this layer is formed by the linear combination of this set of weights and the base

:

The entire search process is constructed as a two-level optimization problem [

35]. This optimization problem contains two nested layers. The upper-level optimization procedure aims to find the optimal architecture parameters (

), while the lower-level optimization procedure aims to find the optimal network weights (

) through standard training for a given set of architecture parameters α. Specifically, in our research, the search objective is to find a set of optimal filter combination parameters

such that the discriminator defined by them

, after being fully trained and obtaining the optimal weights

, can best distinguish between real and fake variation maps. In the GAN framework, this can be formalized as follows:

where the loss function of the discriminator

is the standard adversarial loss. In practice, we adopt an approximate strategy by alternately updating the network weights and architecture parameters in a training batch to solve this problem.

It is worth noting that although a filter bank containing 8 operations is introduced during the search phase, this does not result in parameter redundancy in the final model. The atomic filters in set

(e.g., Gabor, Sobel, Gaussian) are initialized with fixed geometric priors and remain frozen (non-trainable) during the search, which significantly reduces the number of learnable parameters compared to standard convolutions. Moreover, once the search concludes, a discrete pruning step is performed where only the atomic filter with the highest importance weight

is retained for each layer, while other paths are discarded. This ensures that the final model deployed for inference is compact and efficient. Regarding theoretical stability, the convergence of this bi-level optimization is guaranteed by the continuous relaxation of the search space via Softmax, rendering the loss function differentiable with respect to the architecture parameters [

35]. Furthermore, to ensure stability in the adversarial setting, we enforce a Lipschitz continuity constraint implicitly through gradient clipping. By bounding the gradient norms, we prevent the oscillation often observed in dynamic architecture search and theoretically guide the generator and discriminator towards a stable Nash equilibrium.

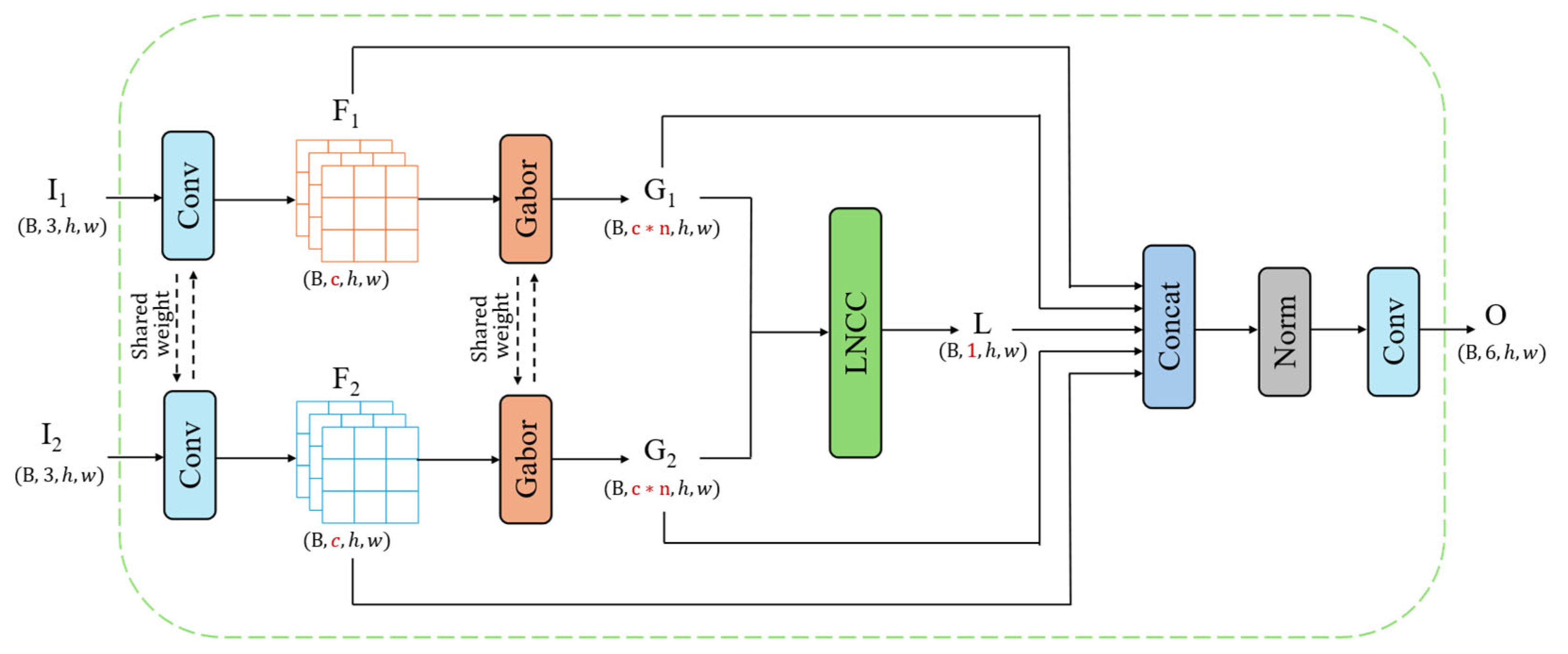

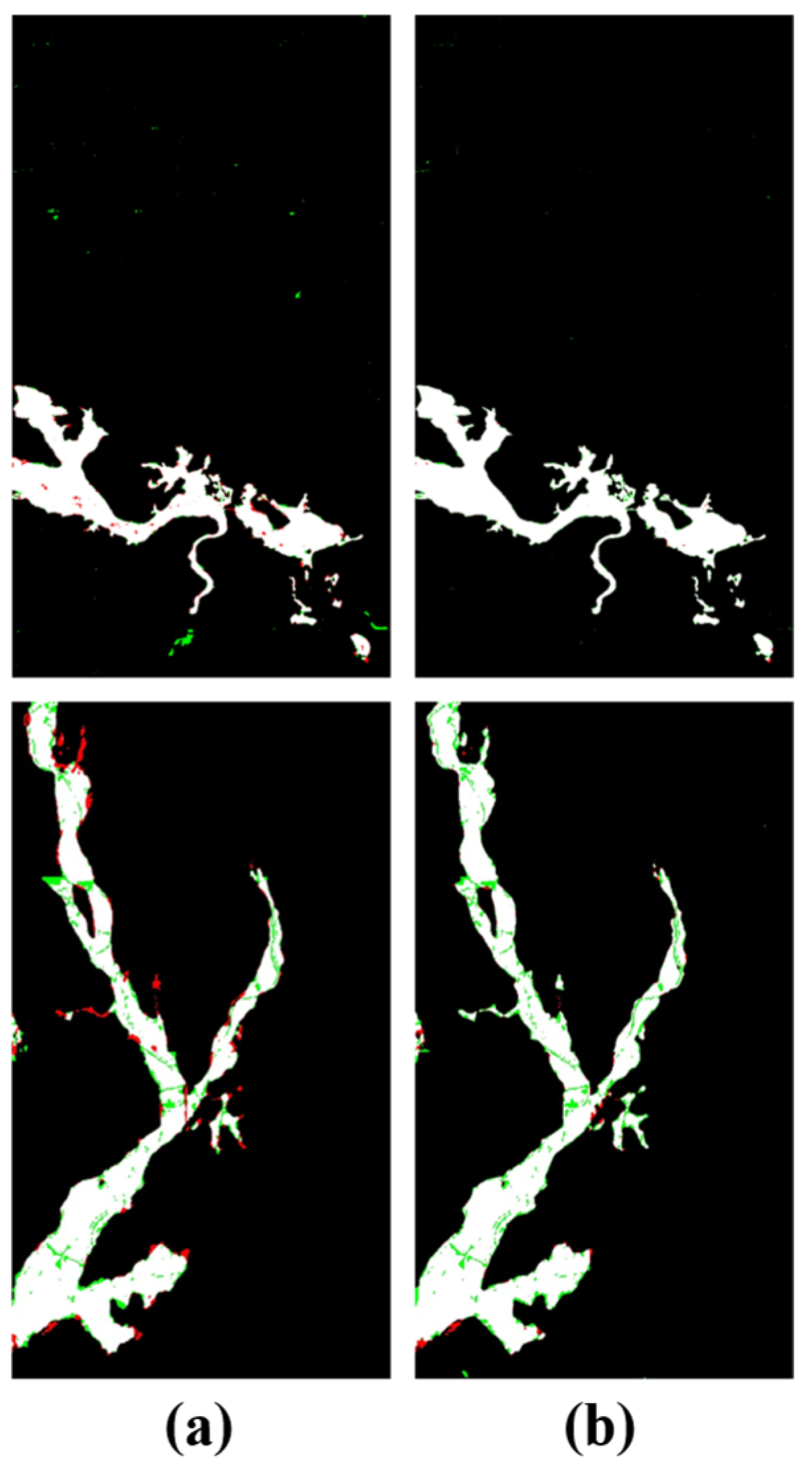

3.3. Feature Fusion Module Based on Gabor and Local Normalized Cross-Correlation (G-LNCC)

In the Hete-CD task, the most fundamental challenge lies in effectively comparing compare two completely different data sources. If the original heterogeneous image pairs are directly input into a standard encoder–decoder network, the network would require significant learning capacity to implicitly align the two modalities, which is not only inefficient but also highly susceptible to noise and imaging differences, leading to inadequate feature extraction results. To proactively bridge this semantic gap before the data enter the main network, we design a plug-and-play G-LNCC feature fusion module (the Gabor and local normalized cross-correlation fusion module) as a critical preprocessing component for the generator network, whose detailed architecture is shown in

Figure 4. This module is aimed at transforming unstable raw pixel information into a shared feature space that is more robust to modality differences. The core idea is to extract and compare the more robust common features between the two modalities—texture and local structure features. To this end, we first use Gabor filters to process the two heterogeneous images separately. As excellent multiscale, multidirectional texture analysis tools, Gabor filters can capture underlying patterns that are independent of specific pixel values, such as the arrangement of buildings and the shape of vegetation. The real kernel function of a two-dimensional Gabor filter can be obtained by multiplying a Gaussian function by a cosine plane wave, which is defined as follows:

where

, and

. The parameters in the formula control the characteristics of the filter:

is the wavelength of the cosine function,

is the direction of the parallel stripes,

is the phase shift,

is the standard deviation of the Gaussian envelope, and

is the spatial aspect ratio. By constructing a filter bank consisting of multiple Gabor kernels with different

values, we can extract a comprehensive set of multidirectional texture feature maps from each input image. To ensure reproducibility, the hyperparameters for the Gabor filter bank were set as follows: the kernel size is

, the number of orientations is

, the wavelength is

, the standard deviation is

, the spatial aspect ratio is

, and the phase offset is

. For the Local Normalized Cross-Correlation (LNCC) calculation, we utilized a local window size of

and a stride of 1 to maintain the spatial resolution of the feature maps.

After obtaining the Gabor texture feature map, we further use local normalized cross-correlation (LNCC) to calculate the structural similarity between the spatially corresponding neighborhoods of the two texture maps. LNCC measures the linear correlations of local patterns and is insensitive to absolute brightness differences, making it highly suitable for comparing heterogeneous images. For two windows centered on a pixel

, the LNCC values of the Gabor feature blocks

and

within these windows are calculated as follows:

where

and

are the mean values of the features within the two windows and

is a minimum value that is used to prevent the denominator from being zero. This formula essentially calculates the cosine similarity between two centered feature vectors, with values ranging from

, effectively measuring their structural consistency.

Finally, we concatenate the following feature maps: the original features

, the multidirectional Gabor texture features

, and the LNCC structural similarity map (

) to form a highly condensed input tensor

:

This tensor is then passed through a fusion block consisting of a 1×1 convolution layer followed by Batch Normalization and ReLU activation. This learnable projection layer automatically re-weights the concatenated features and aligns their scales, generating the final fusion features , providing a high-quality, information-rich input for precise change detection in the encoder–decoder network of the main network.

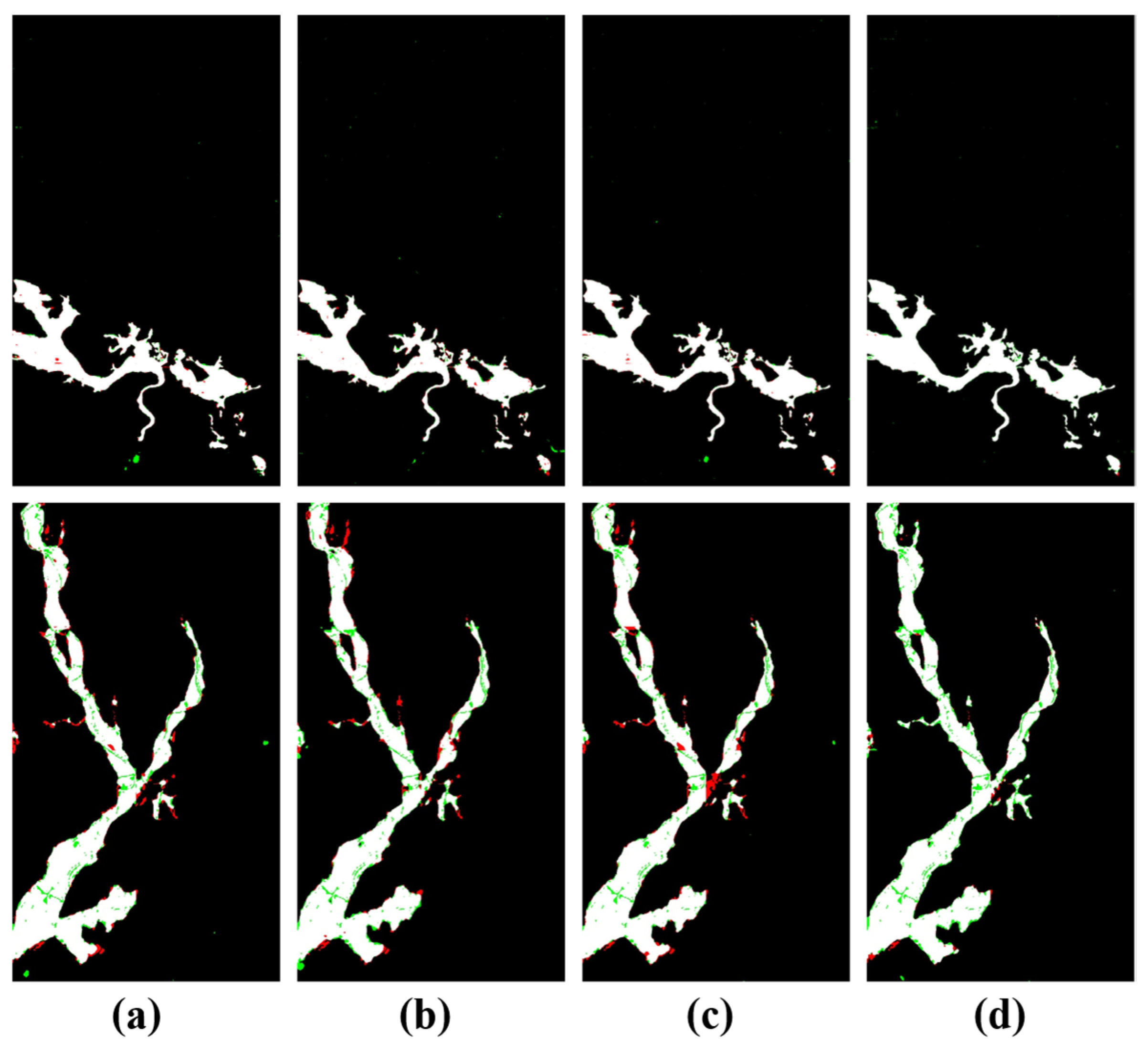

3.4. Geometric Structure-Based Collaborative Supervision Loss (GSCS Loss)

Traditional segmentation tasks often involve the use of a single pixel-level loss function, such as the binary cross-entropy loss (BCE). This loss typically focuses only on pixel-level classification accuracy while ignoring the structural integrity and spatial continuity that change regions should have as a whole. This strategy has obvious shortcomings in complex Hete-CD tasks. 1) Blurred boundaries: The loss function treats all pixels equally, resulting in smooth transitions at the edges of changing regions instead of the clear boundaries expected for geographical entities. 2) Structural distortions: The model may generate a large number of isolated “salt-and-pepper noise” points or fragmented patches that do not conform to geographical spatial patterns and lack structural realism.

To address these issues, we propose a geometric structural collaborative supervision loss (GSCS loss). This loss function ensures that the generator (

) is subject to comprehensive and complementary constraints during the optimization process. It is defined as the weighted sum of three independent components:

Here, is the pixel-level region loss, is the edge consistency loss, and is the global structural adversarial loss. and are hyperparameters for balancing the various losses. This set of loss functions synergistically constrains the solution space of the model from different geometric and structural levels: focuses on the accuracy of regions, reinforces the contours of boundaries, and ensures the overall structural authenticity of the generated variation images from a global perspective.

: To simultaneously ensure high pixel-level classification accuracy and region-level overlap, we adopt a joint loss function combining the BCE and IoU losses (BCEIoULoss). This combination maintains pixel-wise fidelity while effectively mitigating the severe class imbalance inherent in change detection, thereby preventing the model from producing biased, background-only predictions. It is composed of the binary cross-entropy loss (

) and the intersection-over-union ratio loss (

):

where

and

represent the true labels and predicted probabilities of pixel

, respectively;

is the total number of pixels;

is the minimum value for preventing the denominator from being zero; and

provides a robust segmentation foundation for the model.

: To obtain clear change boundaries, we introduce a gradient consistency loss. Geometric structures, unlike pixel intensities, exhibit modality invariance across heterogeneous sensors. By penalizing gradient discrepancies using the Sobel operator, the model can effectively suppress boundary blurring and ensure sharp edge alignment, which is crucial for enhancing the robustness of Hete-CD. This loss is obtained by calculating the L1 distance between the generated change map and the gradient map (i.e., edge map) of the ground truth. The gradient map is generated using the Sobel operator

. The loss is defined as follows:

where

is the input image pair,

is the output of the generator,

is the sigmoid function, and

is the ground truth. This loss term acts as an explicit regularization term, specifically penalizing predictions with blurry boundaries, with a focus on boundary accuracy.

: To address the issue of structural realism encountered in the final generated change maps, we introduce an adversarial loss. The standard static losses often lead to over-smoothed results, while dynamic adversarial supervision compels the generator to capture high-frequency details and maintain global structural realism, ensuring the generated maps follow the intrinsic distribution of the ground truth. By training a discriminator

to distinguish between the real change maps (from

) and the change maps generated by the generator

(

), we force

to learn the intrinsic data distribution of the real change maps. The adversarial loss of the generator

is aimed at maximizing the probability of the discriminator making a mistake and is defined as follows: