Highlights

What are the main findings?

- The study proposes BuildFunc-MoE, an adaptive multimodal Mixture-of-Experts network integrating HR-RS imagery, NTL, DEM, and POI data for fine-grained building function identification, achieving dynamic and hierarchical cross-modal fusion.

- On the self-constructed Wuhan-BF dataset, BuildFunc-MoE achieves state-of-the-art accuracy (mIoU = 87.56%), outperforming existing CNN- and Transformer-based models while maintaining efficient inference through sparse expert activation.

What are the implications of the main finding?

- The adaptive MoE fusion framework offers a scalable and generalizable solution for fine-grained urban function mapping and spatial intelligence tasks.

- The proposed approach can be extended to multi-city applications, supporting data-driven urban planning, infrastructure monitoring, and sustainable governance.

Abstract

Fine-grained building function identification (BFI) is essential for sustainable urban development, land-use analysis, and data-driven spatial planning. Recent progress in fully supervised semantic segmentation has advanced multimodal BFI; however, most approaches still rely on static fusion and lack explicit multi-scale alignment. As a result, they struggle to adaptively integrate heterogeneous inputs and suppress cross-modal interference, which constrains representation learning. To overcome these limitations, we propose BuildFunc-MoE, an adaptive multimodal Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) network built on an effective end-to-end Swin-UNet backbone. The model treats high-resolution remote sensing imagery as the primary input and integrates auxiliary geospatial data such as nighttime light imagery, DEM, and point-of-interest information. An Adaptive Multimodal Fusion Gate (AMMFG) first refines auxiliary features into informative fused representations, which are then combined with the primary modality and passed through multi-scale Swin-MoE blocks that extend standard Swin Transformer blocks with MoE routing. This enables fine-grained, dynamic fusion and alignment between primary and auxiliary modalities across feature scales. BuildFunc-MoE further introduces a Shared Task-Expert Module (STEM), which extends the MoE framework to share experts between the main BFI task and auxiliary tasks (road extraction, green space segmentation, and water body detection), enabling parameter-level transfer. This design enables complementary feature learning, where structural and contextual information jointly enhance the discrimination of building functions, thereby improving identification accuracy while maintaining model compactness. Experiments on the proposed Wuhan-BF multimodal dataset show that, under identical supervision, BuildFunc-MoE outperforms the strongest multimodal baseline by over 2% on average across metrics. Both PyTorch and LuoJiaNET implementations validate its effectiveness, while the latter achieves higher accuracy and faster inference through optimized computation. Overall, BuildFunc-MoE offers a scalable solution for fine-grained BFI with strong potential for urban planning and sustainable governance.

1. Introduction

Fine-grained identification of building functions, which refers to the specific use or purpose of individual structures (e.g., residential, commercial, industrial, educational), has become a critical aspect of urban analysis [1,2]. Detailed information on building usage is essential for city planning, digital twin development, disaster response, and infrastructure provisioning [3,4]. Unlike broad land-use zoning, building-level functional classification captures the heterogeneous socio-economic roles and human activities embedded within urban environments [5,6]. However, traditional approaches have been largely limited to coarse categorization due to data scarcity and reliance on manual mapping, which obscures the nuanced usage patterns of individual buildings [7,8,9]. These limitations have led to growing interest in the past years in leveraging remote sensing (RS) and large-scale geospatial data to enable more detailed and scalable mapping of building functions.

Existing studies on urban function mapping have commonly employed single-modal inputs, particularly high-resolution remote sensing (HR-RS) imagery acquired from satellite or aerial observations [10,11,12]. HR-RS imagery provides rich spatial detail, such as building footprints, roof textures, and contextual surroundings, and has long served as a primary data source for urban land-use classification [13,14]. Deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs) [15,16] and, more recently, vision transformers (ViTs) [17,18] have been applied to classify buildings or land-use categories from overhead imagery alone. These findings suggest that HR-RS data, when combined with advanced deep learning architectures, can effectively capture building-level functional patterns. Recent studies also suggest that hybrid CNN–Transformer architectures with explicit cross-layer interactions can improve urban land-use and functional-zone classification by combining local structural cues with long-range contextual patterns. These hybrid designs have been successfully applied to land-use and land-cover mapping, reporting improved accuracy over single-backbone baselines in complex urban environments [19,20,21,22].

However, despite these advances, HR-RS imagery alone often fails to disambiguate semantically similar structures or capture subtle functional cues, prompting growing interest in multimodal data integration [23,24,25]. Different modalities offer complementary information about building functions. For example, nighttime light (NTL) intensity reflects human activity after dark, helping distinguish visually similar structures (e.g., warehouses vs. residential towers). The Digital Elevation Model (DEM) provides terrain-aware priors that suppress non-structural elements and improve building discrimination in complex urban scenes. Point-of-interest (POI) data and other geospatial semantic sources offer textual or categorical labels for on-site facilities, serving as strong priors for function classification. Recent studies have demonstrated the benefits of integrating such modalities. For instance, Lu et al. [26] proposed a CNN-based multimodal framework that integrates HR-RS imagery, NTL, road networks, and POI data through attention-driven feature fusion. The model jointly learns visual, semantic, and contextual representations to characterize both physical morphology and human activity intensity, enabling robust and transferable building function mapping across multiple metropolitan regions. This unified framework demonstrates strong generalization ability across different urban environments and highlights the necessity of cross-domain feature alignment when handling heterogeneous data sources. Similarly, Lin et al. [27] developed a dual-branch CNN architecture to fuse high-resolution imagery with POI-derived spatial representations, achieving significant improvements in building function classification accuracy compared with single-modality baselines. Their results show that POI density and category distribution provide essential semantic cues for inferring building usage types, while image-based structural features contribute to spatial localization and contextual refinement, together forming a synergistic multimodal representation. Furthermore, Zhou et al. [28] introduced a transformer-based network that aligns visual features from HR-RS imagery with textual POI embeddings through a cross-attention mechanism, allowing the model to capture long-range dependencies between spatial texture patterns and semantic building contexts. This approach enables fine-grained and mixed-use building recognition, effectively addressing the limitations of CNN-based fusion methods in modeling complex multimodal interactions. Moreover, Zhou et al. [29] demonstrated that an enhanced multimodal transformer with hierarchical attention further strengthens the complementarity between HR-RS imagery and POI semantics, substantially improving building function discrimination in dense urban fabrics where visual similarities and overlapping land-use types often lead to confusion.

Despite advances in supervised multimodal semantic segmentation, progress remains constrained by the intrinsic complexity of multimodal data integration and the lack of adaptive fusion mechanisms. First, modality heterogeneity introduces both architectural and learning challenges. RS and geospatial data differ in format, resolution, and spatial coverage, making naive early fusion approaches, such as plain channel stacking or feature concatenation without adaptive weighting or alignment, ineffective or even detrimental due to misaligned representations and cross-modal noise [30,31]. Likewise, feature-level fusion, as well as late fusion at the decision level, often relies on static fusion schemes that lack explicit multiscale alignment and adaptability to modality-specific variations, limiting fine-grained cross-modal interaction and semantic dependency modeling [26,32]. Such rigidity hinders adaptive integration of heterogeneous inputs and suppression of cross-modal interference, ultimately constraining representation learning. Second, modality imbalance may degrade performance when auxiliary inputs dominate or introduce noise [33,34]. For instance, while POI data help distinguish categories with strong socio-economic attributes (e.g., commercial or educational buildings), they are often sparse, noisy, or spatially misaligned for visually distinctive classes such as industrial or mixed-use complexes. In contrast, HR-RS imagery provides dense, spatially aligned, and morphologically rich cues that directly reflect building form and context, making it better suited for fine-grained functional classification and thus a more reliable primary modality [35]. These limitations underscore the need for adaptive, hierarchically aligned fusion frameworks that preserve core visual structures while selectively integrating complementary auxiliary information.

To address the aforementioned limitations in multimodal fusion for fine-grained BFI, we propose BuildFunc-MoE, an adaptive Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) network built upon a Swin-UNet backbone. The model treats HR-RS imagery as the primary modality while integrating auxiliary sources such as NTL, DEM, and POI data. On this basis, BuildFunc-MoE introduces two core fusion components and one auxiliary enhancement module. First, an Adaptive Multimodal Fusion Gate (AMMFG) dynamically refines and weights auxiliary features at the input level, enabling the model to suppress noisy modalities and preserve context-relevant signals. Second, a series of Swin-MoE blocks extend Swin Transformer layers with MoE routing to perform fine-grained, scalable fusion between primary and auxiliary modalities across multiple feature scales, allowing adaptive alignment and selective interaction. In addition, a Shared Task-Expert Module (STEM) serves as a complementary component that facilitates multi-task learning by injecting auxiliary supervision, specifically, road extraction, green space segmentation, and water body detection, into shared expert layers. This module encourages the network to learn spatial and functional priors from related geospatial tasks, thereby improving generalization and alleviating class imbalance. Together, these components enable BuildFunc-MoE to adaptively integrate heterogeneous geospatial sources and jointly optimize auxiliary and main tasks within a unified architecture, achieving high-precision mapping and robust generalization while maintaining scalable performance across diverse urban scenarios.

The contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

- We propose BuildFunc-MoE, a novel multimodal Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) network for fine-grained building function identification (BFI). Built on a Swin-UNet backbone, the model adopts a primary-modality design that centers HR-RS imagery and dynamically routes instances to expert subnetworks for context-aware, flexible fusion with auxiliary modalities (NTL, DEM, POI). Hierarchical, scale-aware expert routing and sparse activation preserve core visual structures while selectively integrating complementary cues, yielding an effective and adaptable end-to-end framework.

- We design an adaptive spatial fusion pipeline that integrates an Adaptive Multimodal Fusion Gate (AMMFG) with Swin-MoE blocks to enable fine-grained, context-aware fusion of multi-source features across scales. This pipeline dynamically aligns heterogeneous modalities and mitigates cross-modal noise, demonstrating superior adaptability and robustness compared with conventional multimodal BFI models.

- We introduce a Shared Task-Expert Module (STEM) to facilitate multi-task learning through shared expert layers across the primary task of building function identification and auxiliary tasks including road extraction, green space segmentation, and water body detection. As a complementary module, STEM enhances shared representation learning, further improving BFI recognition accuracy and enabling effective modeling of complex or mixed-use structures.

- We establish Wuhan-BF, a self-built multimodal benchmark for BFI over Wuhan’s metropolitan area, integrating HR-RS imagery, NTL, DEM, and POI data, with 3000 image patches covering nine building-function categories. On this benchmark, we conduct controlled experiments against representative multimodal BFI models under identical supervision, and BuildFunc-MoE consistently achieves superior accuracy and generalization.

2. Methodology

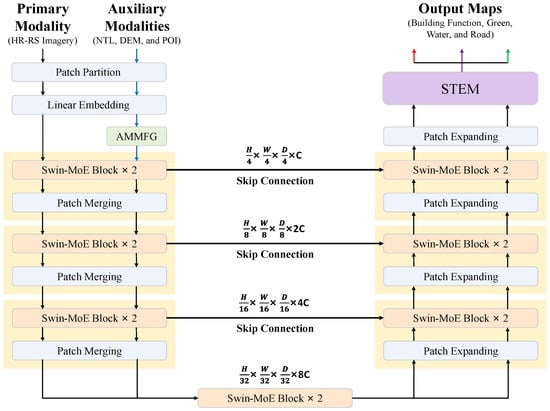

BuildFunc-MoE is an adaptive multimodal network specifically designed for fine-grained BFI. As illustrated in Figure 1, the architecture consists of three core components: an Adaptive Multimodal Fusion Gate (AMMFG), a hierarchical Swin-MoE backbone, and a Shared Task-Expert Module (STEM) for multi-task decoding. Let denote the primary HR-RS image and let denote M auxiliary modalities (NTL, DEM and POI), all resampled to the same spatial resolution. AMMFG converts into a fused auxiliary feature map , which is patch-embedded and injected into each Swin-MoE block as an additional token sequence. The Swin-MoE backbone jointly updates primary and auxiliary tokens through a Mixture Fusion Module, and STEM finally maps the shared representation to dense predictions for building function and auxiliary tasks.

Figure 1.

Overview of the proposed BuildFunc-MoE architecture. HR-RS imagery is used as the primary modality, while NTL, DEM, and POI serve as auxiliary inputs. Features are fused by the AMMFG and encoded by a hierarchical Swin-MoE backbone with skip connections. The STEM decodes multi-scale features to produce building-function maps and ancillary outputs for green, water, and road layers.

At the input stage, HR-RS imagery serves as the primary modality, while auxiliary modalities, including NTL imagery, DEM, and POI data, are adaptively weighted and refined by the AMMFG. This gate dynamically modulates the contribution of each modality according to spatial and contextual relevance, effectively suppressing redundant signals and preserving complementary information.

The fused feature tensors are then processed by a hierarchical Swin-MoE backbone, which extends the Swin-UNet framework with a Mixture-of-Experts routing mechanism. Each Swin-MoE block selectively activates a subset of experts at different feature scales, enabling fine-grained cross-modal fusion while maintaining computational efficiency through sparse activation. Skip connections are employed to preserve spatial details and facilitate gradient flow across encoder–decoder stages.

Finally, the STEM decoder performs multi-task optimization by combining task-specific and shared experts to jointly learn from correlated geospatial tasks. In addition to building function identification, it simultaneously supervises auxiliary outputs for road extraction, green space segmentation, water body detection, and discrete building height classification. These auxiliary predictions are treated as structurally informative supervision signals rather than primary evaluation targets, providing geometric and contextual priors (e.g., transport corridors, open squares, waterfronts, vertical morphology) that are strongly coupled with building function and thereby regularize the shared representation. Overall, the integrated AMMFG-Swin-MoE-STEM pipeline establishes a robust and flexible architecture that achieves high accuracy and strong adaptability across diverse urban morphologies.

2.1. Adaptive Multimodal Fusion Gate

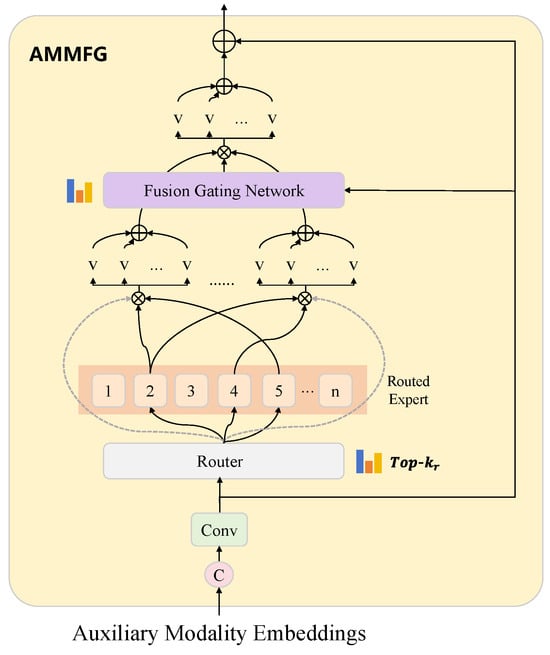

To effectively integrate and manage various auxiliary RS modalities, such as NTL, POI, and DEM, we propose the AMMFG. The AMMFG module is specifically designed to dynamically fuse supplementary modalities in a flexible and adaptive manner, enhancing the model’s capability to capture critical semantic information across diverse data sources.

As illustrated in Figure 2, AMMFG first processes multiple input modalities by concatenating them along the channel dimension. The concatenated features are subsequently projected into a unified embedding space through a convolutional layer. Rather than feeding the concatenated tensor directly into the backbone, AMMFG uses concatenation only to obtain a shared embedding; MoE routing and modality-wise gating then operate on structured logits and modality weights , enabling modality-aware, dynamically weighted fusion instead of static channel stacking. It further uses the MoE router to adaptively select experts and assign modality-specific gates to each branch. Specifically, a routing network first extracts global contextual information through spatial average pooling to compute modality-specific routing logits. Formally, given , the inputs are concatenated as and embedded by a convolution into . We then compute a global context vector via spatial averaging, and feed it to a routing network

where E is the number of experts and stores the normalized routing scores. Here, is a two-layer perceptron with ReLU nonlinearity that maps to logits, and retains the k largest logits for each modality, sets the others to zero and applies a softmax across experts. Formally, and , with the softmax taken along the expert dimension. We denote the gating coefficient for modality m and expert j as , which is taken from . Although the convolution jointly embeds all auxiliary modalities, the routing tensor is explicitly structured with a modality dimension M, so that each still controls the contribution of expert j to the m-th modality before modality-level aggregation. In practice, we keep M separate expert outputs and only merge them through the modality weights in the fusion step below, so the MoE operates on a shared embedding while remaining modality-aware.

Figure 2.

Detailed structure of the AMMFG. The Adaptive Multimodal Fusion Gate (AMMFG) adaptively fuses auxiliary modality features using a Mixture-of-Experts structure and top-k gating, enabling efficient and flexible integration of diverse data sources.

Each selected expert in the MoE architecture is realized through depthwise separable convolutions, designed for efficient yet powerful representation learning. The depthwise convolution captures rich spatial patterns independently across channels, while the subsequent pointwise convolution mixes these spatial features across channels. Let denote the j-th expert, implemented as

where is a depthwise convolution, is a pointwise convolution, is ReLU, and is Group Normalization. Group Normalization divides the channels into G groups and normalizes each group with its own mean and variance, which stabilizes training for varying batch sizes; we denote this operation compactly as .

For each modality m, the expert outputs are aggregated as

where is a small two-layer network that produces M modality logits, are the normalized modality weights, and LN denotes Layer Normalization applied over the channel dimension. The scalar is the weight assigned to the m-th modality and M denotes the total number of auxiliary modalities. The resulting tensor is then patch-embedded into tokens and provided to the Swin-MoE backbone as the auxiliary token sequence.

2.2. Swin-MoE Block

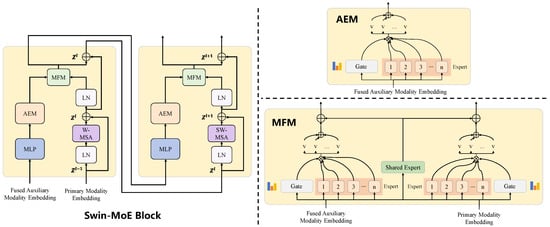

The Swin-MoE backbone is designed for dynamic information exchange and multi-scale feature extraction between the primary HR-RS modality and auxiliary modalities. Based on the Swin-UNet framework, we extend its standard Swin Transformer blocks to incorporate dynamic routing via an MoE architecture (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Detailed structure of the Swin-MoE block. The Swin-MoE block uses Mixture-of-Experts modules and dynamic gating to adaptively fuse auxiliary and primary modality features, enabling efficient cross-modal information exchange.

Initially, fused features from auxiliary modalities undergo preliminary transformation through a multilayer perceptron (MLP), which standardizes and enhances their representational capacity. Subsequently, these transformed features pass through a dedicated MoE module, amplifying crucial representations and improving auxiliary modality fusion quality. This MoE module consists of multiple expert subnetworks whose contributions are dynamically weighted by a gating mechanism. Let denote the token sequence from the primary HR-RS branch and let denote the tokenized auxiliary sequence from AMMFG. Here is the number of image patches for a patch size P, and D is the embedding dimension shared with the Swin-UNet backbone. After window-based self-attention, the Swin-MoE block employs a Mixture Fusion Module (MFM), implemented by the MoE feed-forward network, to jointly update and . MFM first refines the auxiliary tokens by

where is a token-wise MLP, is a linear projection that produces E routing logits for each token, are the expert weights for sample b and token n, and are expert MLPs that act on token-wise representations. The vector is therefore a fused auxiliary token obtained as a weighted sum of expert outputs. In all these expressions, the softmax is applied along the expert index for each sample b and token position n.

The fused auxiliary representation is then used to update both branches through two separate expert banks and a shared expert ,

where and are learned linear projections, and and are expert MLPs for the primary and auxiliary branches, respectively. In practice, these experts are implemented as two-layer MLPs with GELU activation. The updated primary tokens are added back to the residual path, while the updated auxiliary tokens are propagated as the new auxiliary sequence to the next Swin-MoE layer. This explicit formulation clarifies the internal computation of the Mixture Fusion Module and facilitates transparent and reproducible implementation.

Concurrently, primary modality (HR-RS imagery) features are processed by Swin-UNet modules, comprising layer normalization, window-based multi-head self-attention, and another LN layer. This structure leverages the powerful global context modeling capabilities of Transformer architectures, effectively capturing spatial dependencies within the primary modality. The dynamically fused features output by MFM are utilized in subsequent encoding and decoding layers, enabling cross-scale information propagation and reconstruction. Coupled with skip connections, this strategy preserves detailed features crucial for precise building function identification.

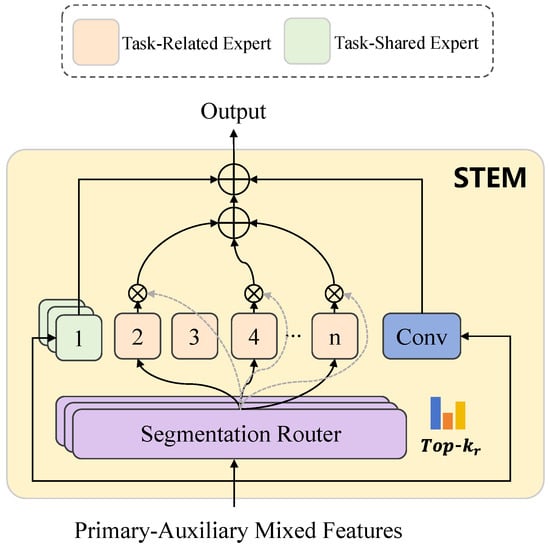

2.3. Shared Task-Expert Module

The Shared Task-Expert Module (STEM) is designed for collaborative optimization between the primary building function identification task and several auxiliary tasks (Figure 4). Specifically, the STEM decoder receives fused features from the encoder, jointly strengthening both task-shared and task-specific representations. Initially, the fused features pass through task-sharing experts, consisting of several low-rank expert subnetworks. These experts, configured with varying ranks, dynamically extract multi-granularity features. A task-specific routing mechanism employs spatial attention to dynamically determine weights for each expert, accurately capturing spatial correlations and differences across tasks.

Figure 4.

Detailed structure of the STEM. The Shared Task-Expert Module (STEM) uses both task-shared and task-specific experts, combined with dynamic routing, to collaboratively optimize multi-task feature representations and improve prediction accuracy for all target tasks.

Let be the fused backbone feature map fed into STEM and let denote the set of tasks, including building function, roads, green space, water and building height. For each task , STEM first applies a convolution to obtain a task-conditioned feature and then uses a spatial-attention-based router to generate routing scores. The router is implemented by the SpatialAtt module, which aggregates spatial information through convolutions, layer normalization and global pooling along . This yields a compact descriptor that is passed through a small linear layer (equivalently, a convolution) to produce logits for E shared low-rank experts and one additional task-specific path. Concretely, for each task t, we compute

where GAP denotes global average pooling over the spatial dimensions. A task-specific linear layer then maps this descriptor to the routing logits,

where is a learnable weight matrix for task t. These logits correspond to the used in the routing equations below. Denoting the resulting logits as , the routing and expert aggregation are

where are shared low-rank LoRA-style experts with different ranks, is a task-specific low-rank expert, is a shared convolutional expert that captures generic context, is a sigmoid function and is a convolutional prediction head producing . TopKSoftmax keeps the most relevant shared experts for task t and normalizes their scores. In practice, we optionally add small Gaussian noise to the shared-expert logits during training to encourage exploration, while the final gating still follows the top-k mechanism above. This formulation explicitly links the task-specific routing mechanism to spatial attention: spatially aware features are globally pooled to obtain routing scores, which assign different weights to shared and task-specific experts for each task.

To further enhance task-specific representations, additional low-rank experts dedicated to individual tasks are incorporated, focusing on capturing unique fine-grained features. Moreover, a generic convolution module is included to enrich global contextual information absent in local features, promoting feature fusion and task collaboration.

Through task-sharing experts, STEM achieves collaborative feature sharing among tasks, significantly enhancing model generalization and reducing overall complexity. Finally, the fused features from STEM are processed through task-specific convolutional heads, translating into distinct task predictions. The flexible multi-task learning framework offered by STEM effectively balances shared and specific learning parameters, substantially improving multi-task performance and accuracy.

2.4. Loss Function Design

To jointly optimize the multi-task objectives in BuildFunc-MoE, we design a composite loss that supervises two outputs: the primary BFI task and an auxiliary land-cover segmentation task (including water, green space, and roads).

For the BFI head, we combine three complementary components, including multi-class cross-entropy, class-wise Intersection over Union (IoU), and focal loss to address class imbalance:

where is the pixel-level cross-entropy loss, is the average IoU over all building-function classes, and follows [36]. We empirically set , , and .

For the auxiliary land-cover head, we adopt a similar structure combining cross-entropy and IoU:

with .

The final training objective aggregates the two branches as

where we set to emphasize the primary BFI task while still benefiting from auxiliary supervision. All loss weights were selected based on preliminary experiments on the validation set to balance the relative contribution and gradient magnitude of each term and to stabilize optimization. We empirically observed that BuildFunc-MoE is reasonably robust to moderate perturbations of these coefficients, and therefore, we fix these values for all experiments reported in this paper.

3. Study Area and Data

3.1. Study Area

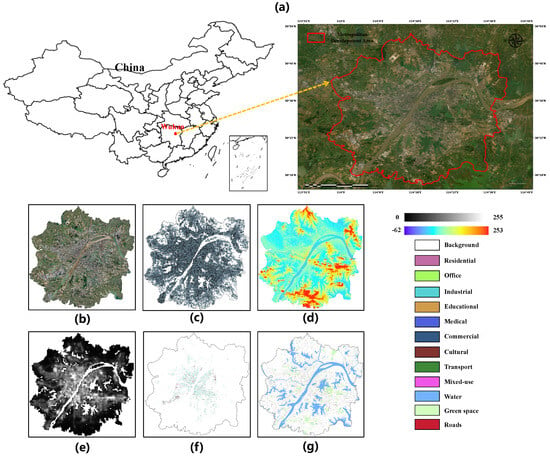

Wuhan, located in central China and serving as the capital of Hubei Province, is a national megacity and a key hub in the Yangtze River Economic Belt. The city covers a total area of approximately and maintains a permanent population of over 11 million. Over the past decades, Wuhan has experienced sustained urban expansion and functional diversification, driven by ongoing infrastructure development, industrial transformation, and spatial policy initiatives. These processes have shaped a highly complex urban landscape characterized by diverse land use categories, vertical urban growth, and spatially heterogeneous building functions. In this study, we focus on Wuhan’s metropolitan development area, encompassing the urban core within and surrounding the Third Ring Road. This area reflects a full spectrum of building functions, including residential, office, industrial, educational, medical, commercial, cultural, transport, and mixed-use types, and exhibits substantial variation in building form, density, and contextual urban fabric. As one of the most intensely developed and functionally diverse urban regions in central China, the selected area offers a representative and challenging setting for evaluating fine-grained building function identification. The spatial extent of the study area is delineated in Figure 5a.

Figure 5.

Study area and multimodal data. The figure depicts (a) the Wuhan Metropolitan Development Area, (b) HR-RS imagery, (c) POI distributions, (d) DEM data, (e) NTL observations, (f) building-function annotations, and (g) auxiliary geospatial layers. The legend conveys spectral, topographic, and semantic information, where grayscale denotes light intensity, color gradients indicate elevation, and categorical hues represent building functions and contextual layers.

3.2. Data

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed model in BFI, we construct Wuhan-BF, a single-year multimodal dataset covering 2024. The dataset offers consistent spatial coverage and co-registered observations from multiple sources and is used for model training, validation, and testing.

HR-RS imagery (Figure 5b) was obtained from Esri World Imagery; cloud-free tiles were selected and resampled to a uniform ground sampling distance of 0.6 m. NTL data (Figure 5e) came from the NPP-VIIRS annual composite at 500 m resolution to capture spatial patterns of human activity. DEM data (Figure 5d) were sourced from ALOS at 12.5 m resolution, providing terrain and morphology cues.

To incorporate semantic context, POI data (Figure 5c) were collected from the Baidu Map API (2023 snapshot). Each POI record includes fields such as name, type, typecode, address, telephone, administrative attributes (province, city, district), and coordinates in both GCJ-02 and WGS-84. We standardized text (normalization and segmentation), harmonized category strings and typecodes with our BFI taxonomy, converted coordinates to WGS-84, removed duplicates, and snapped POIs to the nearest building footprint within a small distance tolerance to reduce geolocation noise. The textual attributes (name, type/typecode and address/business area) were then converted into natural-language “building prompts” and parsed by the Qwen2.5-1.5B large language model to infer building-level functional cues. For each building footprint, all snapped POIs were grouped and formatted as a short instruction plus a bullet-point list of POIs, asking the model to select exactly one label from our nine-category BFI taxonomy (Residential, Office, Industrial, Educational, Medical, Commercial, Cultural, Transport, Mixed-use) and to answer only with that label, without any explanation. For example, a medical building is queried with a prompt such as: “You are an urban planning expert. Based on the following POIs located in and around a single building, determine the dominant building function from Residential, Office, Industrial, Educational, Medical, Commercial, Cultural, Transport, Mixed-use. POIs: (1) ‘Wuhan Third People’s Hospital Outpatient Building’, type: ‘General Hospital’; (2) ‘Emergency Medical Center’, type: ‘Hospital Service’.” The model’s output (e.g., ‘Medical’) is then treated as the building-level functional cue. The resulting semantic cues were rasterized into dense supervision layers using adaptive kernel density estimation (Gaussian kernel with data-driven bandwidth), aligned with the HR-RS grid.

In this study, a building’s function (Figure 5f) is defined as its dominant, relatively stable use within the reference year (2024), rather than short-term or occasional activities. The proposed nine categories are not only aligned with the second-level urban construction-land classes defined in GB/T 21010-2017, but also consistent with widely adopted functional-zone schemes in recent UFZ studies. Prior work typically distinguishes residential, commercial, industrial, public-service and transportation functions, and in many cases further refines them into 8–10 detailed types or explicit mixed-use classes. Following this convention, we adopt nine functional types: residential, office, industrial, educational, medical, commercial, cultural, transport and mixed-use, which provide a balance between semantic interpretability and separability for multimodal RS analyses [1,3,37,38,39]. As additional supervision, auxiliary layers (Figure 5g) including road networks, green spaces, and water bodies were extracted from OpenStreetMap (2023) and rasterized into multi-channel semantic layers.

To generate building-level functional labels, we additionally obtained functional Areas of Interest (AOIs) from the Baidu Map API (e.g., hospital campuses, school grounds, industrial parks, and large commercial complexes). Each AOI represents a spatially coherent functional unit, and all buildings intersecting an AOI were assigned its dominant function. When multiple AOIs overlapped a building, priority was given to specialized functional zones such as hospitals and universities to ensure semantic consistency. To refine these AOI-derived labels, high-resolution optical imagery (0.6 m) was visually inspected to verify building-level functional attributes. Distinctive morphological and contextual features were used to confirm the assigned functions, such as track fields and teaching blocks for schools, multi-wing structures for hospital complexes, long-span sheds and warehouses for industrial facilities, and large flat-roofed structures with surrounding parking areas for commercial centers. Baidu Maps was further consulted as an auxiliary reference to validate ambiguous cases. Through this AOI-driven and imagery-supported workflow, the final labels achieve high spatial coherence and semantic reliability.

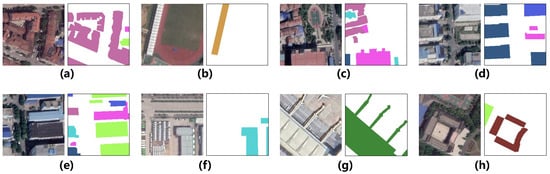

All layers underwent geometric correction, reprojection to a common coordinate reference system, and precise coregistration to the HR-RS grid. From a temporal perspective, all data sources were selected to align around late 2023. The HR-RS mosaic primarily consists of cloud-free Esri World Imagery tiles acquired between late 2023 and early 2024. VIIRS NTL uses the 2023 annual composite, while POI records, building footprints, and AOIs were collected from Baidu Map services during 2023. Road, green, and water layers were extracted from the 2023 OpenStreetMap snapshot, and the ALOS DEM serves as a quasi-static terrain background. We also performed manual inspections to remove patches with clear temporal inconsistencies, such as active construction or demolition areas. Low-resolution modalities (NTL, DEM) were bilinearly upsampled to the HR-RS scale and min-max normalized per modality. The study area was then tiled into non-overlapping -pixel patches, producing a total of 3000 multimodal samples, each paired with a corresponding building-function label mask (Figure 6). To ensure rigorous and unbiased evaluation, we created spatially disjoint training, validation, and testing subsets (approximately 70%/10%/20% by blocks), explicitly preventing geographic leakage across splits. Importantly, each split contains instances of all nine building-function categories, ensuring class coverage for model learning, hyper-parameter tuning, and evaluation.

Figure 6.

Representative samples from the Wuhan-BF Multimodal Dataset, illustrating paired high-resolution optical imagery (a,b,e,f) and corresponding building-function label masks (c,d,g,h). The building function types follow the color legend defined in Figure 5.

Compared with existing urban-function datasets, Wuhan-BF is distinctive in that (i) it provides building-level annotations aligned with the national urban land-use standard GB/T 21010-2017, (ii) each ()-pixel patch is co-registered across four complementary modalities (HR-RS imagery, NTL, DEM and POI-derived semantic layers) together with auxiliary road/green/water masks, and (iii) the nine building-function categories cover a wide spectrum of socio-economic roles within a single metropolitan development area. Public multimodal benchmarks with the same level of building-level detail and modality diversity are still scarce; therefore, in this work we focus on a carefully curated single-city dataset to isolate the effect of the proposed fusion architecture.

4. Experiments

4.1. Implementation Details

All experiments were conducted on a single NVIDIA V100 GPU with 32 GB of memory. Unless otherwise stated, the Swin-UNet backbone follows the standard Swin-Tiny configuration with four encoder–decoder stages, feature dimensions of 96, 192, 384, and 768, and a window size of 7. The numbers of self-attention heads in the four stages are 3, 6, 12, and 24, respectively, and each block uses a two-layer MLP with an expansion ratio of 4 and GELU activation. All Swin-MoE blocks inherit this configuration and replace the standard feed-forward network with the proposed expert-based Mixture Fusion Module. We first implemented BuildFunc-MoE in the LuoJiaNET framework [40] and observed faster convergence and slightly higher accuracy than the PyTorch 1.13.1 implementation under matched hyperparameters. To ensure fair and uniform comparisons, all results reported in this paper, including those of our method, were trained and evaluated in PyTorch [41]. Models were initialized with random weights. We used AdamW with , , and a weight decay of 0.05. Differential learning rates were applied to the backbone and to the decoder and expert modules, with initial values of for the backbone and for the decoder and MoE components. A linear warm-up was used for the first ten epochs, followed by cosine annealing down to . Training was performed for 200 epochs with a per-GPU batch size of 1. Mixed-precision training and gradient clipping were enabled, with a maximum gradient norm of 1.0. The Transformer blocks used a DropPath rate of 0.2. An exponential moving average of the model parameters was maintained with a decay of 0.999. To guarantee reproducibility, random seeds were fixed and a spatially de-correlated data split was adopted. All methods shared the same data partition and training pipeline.

Data augmentation followed common practice in semantic segmentation while enforcing strict geometric consistency across modalities. Geometric transformations included horizontal and vertical flips (each applied with probability 0.5), either discrete ninety-degree rotations (0°, 90°, 180°, 270°) or small-angle continuous rotations sampled uniformly from (), and bounded translations of up to 10 pixels with mild perspective distortion. Radiometric perturbations were applied only to the high-resolution remote-sensing imagery and included modest jitter of brightness, contrast, saturation, and hue (adjustment factors sampled from ([0.8, 1.2])), together with gamma correction , low-amplitude Gaussian noise ( in normalized intensity), and Gaussian blurring with a kernel. NTL and DEM data underwent no radiometric augmentation and were only standardized, while sharing exactly the same geometric transformations as the primary imagery. POI-based raster representations were aligned in the same manner. All experiments used image patches as input. Training samples were obtained via fixed-window tiling. No augmentation was used for validation or testing, and inference was performed at a single scale.

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

The evaluation metrics used in our experiments fall into two primary categories: accuracy and efficiency. In terms of accuracy assessment, we adopted three widely used metrics in semantic segmentation: mean Intersection over Union (mIoU), mean F1-Score (mF1), and Overall Accuracy (OA). These metrics jointly provide a comprehensive and balanced evaluation of the model’s performance across all classes, accounting for both pixel-wise correctness and the trade-off between precision and recall.

The mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) measures the average overlap between predicted segmentation and ground truth across all categories. It reflects the model’s capability to accurately delineate class boundaries and resolve spatial details. The mIoU is calculated as:

where C is the number of classes, and , , and denote the true positives, false positives, and false negatives for class c, respectively.

The mean F1-Score (mF1) combines precision and recall into a single harmonic mean, making it particularly effective in handling class imbalance. It reflects the model’s ability to correctly identify positive samples while minimizing false positives and false negatives. The F1-Score is defined as:

The Overall Accuracy (OA) represents the proportion of correctly predicted pixels out of the total number of pixels, offering an intuitive and general overview of the model’s classification performance. It is defined as:

In addition to these global metrics, we also evaluated Category Accuracy (CA) for each semantic class. This metric provides a more fine-grained analysis by quantifying the per-class accuracy, thereby enabling a detailed comparison of how well the model performs across different building function categories.

For efficiency evaluation, three metrics were used: Parameters (Params, million), Floating Point Operations (FLOPs, billion), and Frames Per Second (FPS, images/s). Params indicate the model size and memory usage, FLOPs reflect the computational cost, and FPS measures the inference speed. In general, lower Params and FLOPs together with higher FPS represent a more efficient model.

4.3. Comparative Methods

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed BuildFunc-MoE model for fine-grained building function recognition, we benchmark it against six representative CNN- and ViT-based semantic segmentation models for single- and multimodal building function analysis, namely MAFNet [24], UnifiedDL-UFZ [26], MMBT [28], CTCFNet [11], CSAGFNet [42], and AWIFMNet [34].

MAFNet utilizes a dual-branch CNN architecture to extract visual features from HR-RS imagery and social features from POI and building footprint data. Its input modalities include HR-RS imagery, POI data, and building footprints.

UnifiedDL-UFZ adopts a dual-branch CNN architecture, where a ResNet-50-based encoder extracts visual features from HR-RS imagery and a parallel CNN branch encodes social features from POI distance maps. Its input modalities include HR-RS imagery and POI data.

MMBT employs a dual-branch architecture, where a pre-trained BERT extracts textual features from POI descriptions and a DenseNet backbone encodes visual features from HR-RS imagery. Its input modalities include HR-RS imagery and POI textual data.

CTCFNet integrates CNN and Transformer architectures through a cross-attention fusion module that enhances semantic feature learning and improves classification accuracy in complex urban environments. Its input modality consists exclusively of HR-RS imagery.

CSAGFNet is a cross-modal spatial alignment and gated fusion network. Its encoder independently extracts spatial features from HR-RS and NTL imagery, performs cross-modal alignment using spatial offset estimation, and subsequently decodes fused features through a gating mechanism.

AWIFMNet builds a multimodal architecture that integrates an adaptive weight interactive fusion module and a multi-scale feature focus module to effectively fuse heterogeneous features and emphasize critical information. Its input modalities include HR-RS imagery, NTL imagery, DEM, and POI data.

4.4. Results

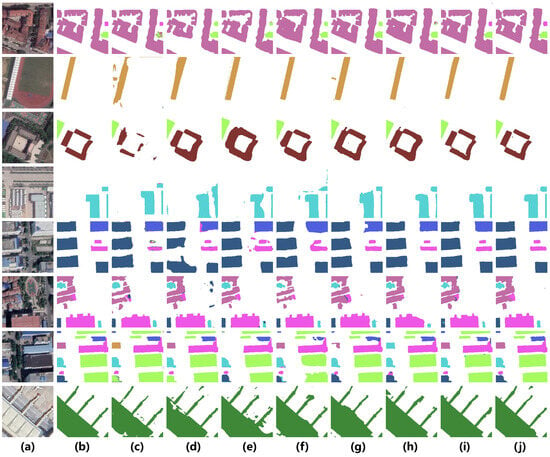

Table 1 presents the quantitative comparison between the proposed BuildFunc-MoE and six representative CNN- and Transformer-based semantic segmentation models for fine-grained building function identification. The evaluation covers both single- and multimodal architectures to comprehensively assess performance under different input modalities. BuildFunc-MoE achieves the highest scores across all evaluation metrics, with an mIoU of 87.56%, mF1 of 93.08%, and OA of 95.70%, clearly surpassing the second-best method, AWIFMNet (mIoU = 85.42%, OA = 95.10%). On average, BuildFunc-MoE improves mIoU by 2.14 percentage points and mF1 by 1.28 points over the strongest multimodal baseline (AWIFMNet), while also yielding a 0.60-point gain in OA, and these gains are consistent across all nine building-function categories. This improvement is not only reflected numerically but also visually in Figure 7, where BuildFunc-MoE produces cleaner and more spatially coherent segmentation maps, with sharper boundaries and fewer class confusions compared to all baselines.

Table 1.

Quantitative comparison of different single- and multimodal semantic segmentation models for fine-grained BFI on the self-constructed Wuhan-BF dataset. The evaluated building function categories include Residential (Res), Office (Off), Industrial (Ind), Educational (Edu), Medical (Med), Commercial (Com), Cultural (Cul), Transport (Tra), and Mixed-use (Mix). BFP stands for building footprint. Bold values denote the best performance in each metric. All models were trained and evaluated under the PyTorch framework for fair comparison, while results marked with * were obtained using the LuoJiaNET framework.

Figure 7.

Qualitative comparison of building function segmentation on representative scenes from the Wuhan-BF dataset. (a) HR-RS imagery; (b) ground truth; (c) CTCFNet; (d) CSAGFNet; (e) UnifiedDL-UFZ; (f) MMBT; (g) MAFNet; (h) AWIFMNet; (i) BuildFunc-MoE (Ours); (j) BuildFunc-MoE * (Ours). The building function types follow the color legend defined in Figure 5. All models were trained and evaluated under the same supervised setting. The PyTorch implementation of BuildFunc-MoE was employed for comparison with other baselines, whereas the LuoJiaNET implementation (denoted by “*” ) exhibited higher accuracy due to optimized computation.

The performance advantage is consistent across all nine building function categories, with particularly strong gains for the more challenging Office (79.25%), Commercial (81.73%), and Transport (91.27%) classes, scenarios that often exhibit high inter-class visual similarity. As shown in dense urban blocks and mixed-use complexes in Figure 7, competing models such as CTCFNet or CSAGFNet tend to generate fragmented predictions or misclassify between Office, Commercial, and Mixed-use buildings, whereas BuildFunc-MoE maintains accurate functional boundaries and correct category assignment. Similarly, in large public facilities and transport regions, our model preserves the geometric integrity of elongated industrial structures and terminal buildings, demonstrating its superior contextual understanding and cross-modal alignment.

From the multimodal perspective, AWIFMNet benefits from the joint utilization of HR-RS, NTL, DEM, and POI data (mIoU = 85.42%), effectively improving overall scene comprehension; however, its static fusion weighting limits adaptability under modality imbalance, occasionally leading to incomplete segmentation in complex scenes. MAFNet (mIoU = 83.10%) and MMBT (mIoU = 82.74%) also leverage complementary information from HR-RS imagery and auxiliary social data (e.g., POI or text), yet their relatively shallow CNN-based fusion strategies restrict their ability to capture long-range dependencies, which is visible in Figure 7 as blurred boundaries and broken small structures. In contrast, UnifiedDL-UFZ (mIoU = 81.33%) achieves moderate results but still shows limited fine-grained feature alignment, while CSAGFNet (mIoU = 79.65%) enhances spatial consistency via cross-modal alignment but lacks additional contextual cues such as DEM and POI. The single-modality CTCFNet (mIoU = 78.23%) performs the weakest overall, its reliance solely on HR-RS imagery fails to distinguish visually similar building types, resulting in mixed labels and spatial discontinuities, as also reflected in Figure 7.

These findings collectively confirm that BuildFunc-MoE achieves both quantitatively superior accuracy and qualitatively more reliable segmentation. The method’s dynamic Mixture-of-Experts fusion adaptively balances heterogeneous modality contributions, leading to robust contextual discrimination across diverse urban morphologies and ensuring stable predictions even under modality imbalance.

In addition, we further implement BuildFunc-MoE using the LuoJiaNET framework to evaluate its cross-framework generalization capability. This implementation achieves overall metrics of mIoU 88.12%, mF1 93.45%, and OA 95.92%, which are slightly higher than those obtained with the PyTorch version (mIoU 87.56%, mF1 93.08%, OA 95.70%). Consistent improvements are also observed for several challenging categories, such as Office (79.84%), Commercial (82.05%), and Transport (91.58%). These results indicate that, compared with the PyTorch implementation, the LuoJiaNET-optimized version achieves more stable convergence and consistently higher accuracy in large-scale remote sensing tasks, thereby enhancing the overall effectiveness of our MoE fusion.

4.5. Ablation Study

4.5.1. Ablation of the BuildFunc-MoE Architecture

To comprehensively evaluate the contribution of each proposed component, we performed an ablation study on the Wuhan-BF dataset, as summarized in Table 2. The baseline Swin-UNet model achieved an mIoU of 83.86% using simple concatenation (SC), original Swin Transformer blocks (OB), and a single-task (ST) setting. Subsequent experiments incrementally incorporated the three core modules of BuildFunc-MoE: the Adaptive Multimodal Fusion Gate (AMMFG), the Swin-MoE block, and the Shared Task-Expert Module (STEM). All experiments were conducted under identical training configurations within the PyTorch framework to ensure fair comparison.

Table 2.

Ablation study on different components of the proposed BuildFunc-MoE model, conducted on the Wuhan-BF dataset introduced in this study. The experiments were implemented using the PyTorch framework. Results are reported in terms of mIoU (%). Bold values indicate the highest performance. SC denotes simple concatenation, OB denotes the original block, and ST denotes the single-task setting.

The results reveal a clear progressive improvement as each component is added. Incorporating AMMFG increases mIoU from 83.86% to 85.12%, confirming its ability to dynamically recalibrate multimodal features and suppress redundant or noisy information from auxiliary inputs such as NTL and POI. By assigning adaptive attention weights, it enables the network to emphasize semantically relevant cues and improves the stability of early fusion. When the Swin-MoE block is further introduced, performance rises to 86.73%, reflecting the benefits of expert routing and sparse activation that promote adaptive multi-scale fusion. This mechanism allows the network to selectively activate modality-specific experts, achieving more accurate alignment between heterogeneous sources and enhancing contextual discrimination. Finally, integrating STEM yields the best result of 87.56%, demonstrating that auxiliary supervision from related spatial tasks, including road, green space, and water segmentation, effectively strengthens high-level representation learning. This shared expert mechanism facilitates parameter-level transfer, helping the model capture broader spatial structures and mitigate confusion among visually similar building classes such as office and commercial areas.

Notably, AMMFG, Swin-MoE, and STEM work synergistically rather than as independent add-ons. AMMFG serves as a modality-aware preprocessing stage that suppresses cross-modal noise and imbalance by refining and reweighting heterogeneous auxiliary inputs into a compact, spatially aligned auxiliary stream, providing stable tokens for subsequent fusion. Built upon this refined auxiliary representation, Swin-MoE performs hierarchical multi-scale expert routing, selectively injecting complementary auxiliary cues into the primary HR-RS features at different encoder–decoder stages, so that coarse scales emphasize global context (e.g., activity intensity and terrain priors) while finer scales preserve local structure and semantic details. STEM further consolidates the fused representation through multi-task supervision on structurally correlated tasks (roads/green/water), whose gradients propagate back to the shared backbone and implicitly regularize the modality gates and scale-wise expert selection, encouraging consistent modality/scale preferences that benefit the main BFI objective. Consequently, AMMFG reduces interference, Swin-MoE exploits the cleaned signals for scale-adaptive fusion, and STEM regularizes the shared features with geometry-aware priors, yielding a synergistic improvement in robustness and discrimination under complex urban scenes and modality imbalance.

The overall performance increases steadily from 83.86% to 87.56%, confirming that the combination of AMMFG, Swin-MoE, and STEM forms a synergistic architecture. Their joint design enables robust multimodal representation learning, fine-grained urban structure understanding, and reliable building function identification across diverse urban morphologies.

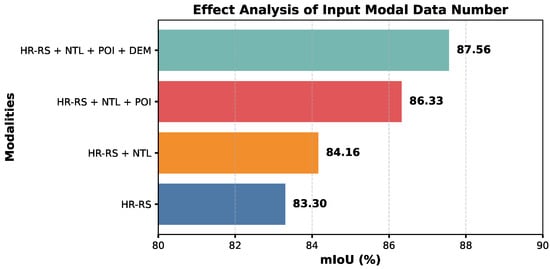

4.5.2. Effect Analysis of Input Modal Data Number

To investigate the influence of input modality composition on the proposed BuildFunc-MoE model, we conducted a controlled experiment by incrementally increasing the number of input data modalities. As shown in Figure 8, the overall segmentation performance consistently improves as more modalities are incorporated, confirming the model’s capacity to effectively integrate heterogeneous geospatial information. Using only HR-RS imagery yields an mIoU of 83.30%, which serves as the unimodal baseline. Adding NTL data increases the mIoU to 84.16%, demonstrating that the additional spatial–contextual signal contributes to better representation of built-up intensity. When POI data are further introduced, the mIoU rises to 86.33%, indicating that semantic and functional context enrich the model’s feature space. Finally, incorporating DEM information leads to the highest mIoU of 87.56%, showing that terrain and elevation cues provide complementary topographic information that further enhances segmentation accuracy.

Figure 8.

Effect analysis of input modal data number on the proposed BuildFunc-MoE model, evaluated on the Wuhan-BF dataset using the PyTorch framework. Results are reported in terms of mIoU (%).

These results confirm that BuildFunc-MoE scales favorably with the diversity of input modalities. The adaptive MoE fusion mechanism enables the network to dynamically balance modality contributions according to spatial and contextual relevance, while suppressing redundant information. Consequently, the model achieves more comprehensive scene understanding and robust building function recognition as the multimodal context becomes richer, illustrating the strong adaptability and fusion capacity of the proposed architecture.

4.5.3. Evaluating Expert Numbers and the Top-k Tradeoff in MoE Modules

To further examine the effect of expert capacity and routing sparsity on the BuildFunc-MoE model, we performed a detailed ablation study by varying the number of experts and top-k selections within the AMMFG, Swin-MoE, and STEM modules. The quantitative results are summarized in Table 3. As shown, the mIoU steadily increases with larger expert counts and more active expert selections, indicating that the model benefits from richer expert diversity and greater routing flexibility. However, the gains gradually saturate when both the number of experts and the top-k ratio become excessive, suggesting diminishing returns relative to computational cost.

Table 3.

Ablation of expert-based components across AMMFG, Swin-MoE, and STEM, with corresponding mIoU, parameter count, and FLOPs. Experiments were conducted on the Wuhan-BF dataset using the PyTorch framework. Results are reported in mIoU (%), Params (M), and FLOPs (G). Arrows indicate metric preference (↑: higher is better, ↓: lower is better), and Bold numbers denote the best value for each metric.

Specifically, when only a small number of experts (e.g., 8) are used across modules, the model achieves moderate performance (85.42–86.74% mIoU) due to limited specialization among expert sub-networks. Increasing the number of experts to 16 and top-k to 6 yields a significant performance improvement, reaching 87.56% mIoU with 231.37 M parameters and 107.4 G FLOPs. This configuration achieves the best trade-off between accuracy and efficiency, demonstrating that moderate expert diversity coupled with sparse activation enables the network to capture complementary modality relationships without excessive redundancy. In contrast, the configuration with 32 experts and top-k = 12 achieves the highest mIoU (87.63%) but incurs substantially higher computational cost (278.6 M parameters, 154.1 G FLOPs), confirming that overly dense routing provides limited accuracy gain relative to efficiency loss.

These observations align with the Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) principle, where sparse expert routing allows the model to dynamically assign specialized sub-networks to different spatial–contextual patterns. In BuildFunc-MoE, the AMMFG module leverages multiple experts to refine cross-modal feature fusion at the input level, Swin-MoE employs hierarchical experts to perform selective multi-scale interaction, and STEM shares expert parameters between primary and auxiliary tasks to encourage high-level feature transfer. As the number of experts increases, these modules jointly enhance the model’s representational capacity while maintaining conditional sparsity that reduces computational overhead. Consequently, BuildFunc-MoE exhibits strong scalability, achieving consistent accuracy improvements under richer expert settings, while preserving practical efficiency for large-scale urban scene understanding.

5. Discussion

5.1. Computational Efficiency

Table 4 compares the computational complexity, inference speed, and segmentation accuracy of the proposed BuildFunc-MoE against representative CNN- and Transformer-based baselines for fine-grained BFI. As expected, traditional CNN architectures such as MAFNet and UnifiedDL-UFZ exhibit lower computational demands, with fewer parameters (69–78 M) and moderate inference speed (≈40 FPS), yet their reliance on static fusion and limited contextual modeling results in suboptimal segmentation accuracy (81–84% mIoU). Transformer-enhanced models such as MMBT and CSAGFNet increase the model capacity and multimodal reasoning ability, but the higher parameter count (≈90–110 M) and attention-driven fusion reduce inference efficiency to below 40 FPS. AWIFMNet, which employs multi-branch adaptive weighting across four modalities (HR-RS, NTL, DEM, and POI), further improves accuracy to 85.67% but incurs notable computational overhead (128 M parameters, 73.6 G FLOPs).

Table 4.

Comparison of model complexity, inference speed, and segmentation accuracy for fine-grained BFI on the self-constructed Wuhan-BF dataset. Results are reported as Params (M), FLOPs (G), FPS (images/s), and mIoU (%). Arrows indicate metric preference (↑: higher is better, ↓: lower is better). Bold numbers denote the best value for each metric. BFP stands for building footprint. All models were trained and evaluated under the PyTorch framework with input images uniformly resized to 224 × 224 for fair comparison, while results marked with * were obtained using the LuoJiaNET framework.

In contrast, BuildFunc-MoE introduces a Mixture-of-Experts architecture that adaptively allocates modality-specific sub-networks via sparse expert routing. Although it has a higher theoretical complexity (231 M parameters, 107 G FLOPs), its expert sparsity ensures that only a subset of experts is activated per instance, leading to efficient utilization of computational resources. This design enables the model to achieve the best segmentation performance (87.56% mIoU) among all compared methods while maintaining competitive inference efficiency (31.6 FPS). The flexible multimodal input design also allows BuildFunc-MoE to handle diverse geospatial data configurations without retraining, demonstrating strong adaptability to heterogeneous urban data sources. Furthermore, when implemented under the LuoJiaNET framework, BuildFunc-MoE achieves an even higher efficiency of 47.4 FPS with reduced complexity (229.85 M parameters and 105.96 G FLOPs), along with improved accuracy (88.12% mIoU). This improvement stems from LuoJiaNET’s optimized graph-level computation, memory scheduling, and mixed-precision acceleration tailored for large-scale RS tasks.

Overall, despite its larger parameter footprint, BuildFunc-MoE delivers the most favorable balance between accuracy, flexibility, and efficiency, making it particularly well-suited for large-scale fine-grained BFI in complex urban environments.

5.2. Limitations and Future Works

Although BuildFunc-MoE demonstrates promising results in fine-grained BFI, several limitations remain and warrant further investigation. Three major aspects are identified concerning its current constraints and directions for future improvement.

(1) Limited auxiliary data diversity: BuildFunc-MoE currently integrates only a few auxiliary sources, including NTL imagery, DEM, and POI data. These inputs offer useful spatial signals but fail to capture real-time human activity. Additional data types, such as population distribution, mobile phone signaling, and traffic flow, can better represent urban intensity and functional dynamics. Incorporating such human-centered modalities may improve performance in complex or mixed-use areas.

(2) Limited generalization across cities and datasets: The current evaluation is conducted solely on the self-constructed Wuhan-BF dataset, which, although comprehensive, represents a single urban morphology and regional planning context. To rigorously assess cross-city generalization, future studies should extend BuildFunc-MoE to additional metropolitan regions such as Beijing, Shenzhen, Chengdu, and Harbin, encompassing diverse climatic, morphological, and socioeconomic characteristics. Moreover, expanding the dataset to include more building samples and multimodal data across cities will enable large-scale benchmarking and more stable training for nationwide BFI applications.

(3) Opportunities for stronger vision–text integration and comparative baselines: While BuildFunc-MoE surpasses conventional baselines, it has not yet been compared with advanced vision foundation models such as SAM [43,44] or the DINO [45,46] series. These models offer strong generalization and may further enhance feature learning. Additionally, the current POI input relies on category-based density maps derived from LLM classification, which omits the intrinsic textual semantics of POI descriptions. Future work could directly encode these text embeddings and employ vision–language fusion strategies to achieve richer multimodal understanding and more discriminative urban function recognition.

6. Conclusions

This paper presents BuildFunc-MoE, an adaptive multimodal Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) framework for fine-grained building function identification (BFI). The model integrates HR-RS, NTL, DEM, and POI data through an Adaptive Multimodal Fusion Gate (AMMFG), Swin-MoE blocks, and a Shared Task-Expert Module (STEM), enabling dynamic cross-modal fusion, adaptive expert routing, and multi-task knowledge transfer. Extensive experiments on the self-constructed Wuhan-BF dataset demonstrate that BuildFunc-MoE achieves the highest accuracy (87.56% mIoU) among existing CNN- and Transformer-based baselines, while maintaining efficient inference (31.6 FPS) through sparsely activated expert modules. The LuoJiaNET implementation further enhances performance (88.12% mIoU, 47.4 FPS) by leveraging graph-level and mixed-precision computation optimized for large-scale remote sensing tasks. Overall, BuildFunc-MoE provides a scalable, generalizable, and efficient multimodal solution for urban function mapping. Its adaptive fusion strategy and flexible architecture enable robust performance across diverse urban morphologies and data modalities. Future work will extend this framework to multi-city datasets and incorporate richer human activity and socioeconomic data, paving the way for more comprehensive and intelligent urban analytics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.W. and Z.Z.; Methodology, R.W., Z.Z. and D.S.; Validation, R.W., D.S. and F.W.; Formal analysis, Z.Z. and N.J.; Investigation, D.S., W.H. and N.J.; Writing—original draft preparation, R.W. and Z.Z.; Writing—review and editing, D.S., F.W. and X.C.; Supervision, Z.P. and X.C.; Project administration, Z.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42271354).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions of this work are fully contained in the article. Requests for additional information may be directed to the co-first authors, who contributed equally to this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liu, B.; Deng, Y.; Li, M.; Yang, J.; Liu, T. Classification schemes and identification methods for urban functional zone: A Review of Recent Papers. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Chen, R.; Yang, J.; Li, Y.; Jiang, H.; Liao, W.; Sun, M. Identify urban building functions with multisource data: A case study in Guangzhou, China. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2022, 36, 2060–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ou, J.; Liu, X. Identifying building function using multisource data: A case study of China’s three major urban agglomerations. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 108, 105498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Ren, L.; Liu, C.; Wang, Y.; Yu, H.; Schmitt, M.; Hänsch, R.; Sun, X.; Huang, H.; Mayer, H. Urban building classification (ubc)-a dataset for individual building detection and classification from satellite imagery. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 1413–1421. [Google Scholar]

- Du, S.; Du, S.; Liu, B.; Zhang, X. Mapping large-scale and fine-grained urban functional zones from VHR images using a multi-scale semantic segmentation network and object based approach. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 261, 112480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandam, A.; Busari, E.; Syranidou, C.; Linssen, J.; Stolten, D. Classification of building types in germany: A data-driven modeling approach. Data 2022, 7, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabove, P.; Daud, M.; Olivotto, L. Revolutionizing urban mapping: Deep learning and data fusion strategies for accurate building footprint segmentation. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chen, B.; Wu, S.; Su, M.; Chen, J.M.; Xu, B. Deep learning for urban land use category classification: A review and experimental assessment. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 311, 114290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, A.; Warth, G.; Bachofer, F.; Schultz, M.; Hochschild, V. Mapping urban structure types based on remote sensing data—A universal and adaptable framework for spatial analyses of cities. Land 2023, 12, 1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; He, Z.; Xie, X.; Xie, Z.; Luo, J.; Xie, H. Building function classification in Nanjing, China, using deep learning. Trans. GIS 2022, 26, 2145–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, M.; Lou, K. Building Type Classification Using Dual-Encoder Interaction Network from Very-High-Resolution Remote Sensing Images. In Proceedings of the 2024 8th Asian Conference on Artificial Intelligence Technology (ACAIT), Fuzhou, China, 8–10 November 2024; pp. 496–500. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Deng, M.; Luo, G. Recognizing building group patterns in topographic maps by integrating building functional and geometric information. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuypers, S.; Nascetti, A.; Vergauwen, M. Land Use and Land Cover Mapping with VHR and Multi-Temporal Sentinel-2 Imagery. Remote. Sens. 2023, 15, 2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killeen, J.; Jaupi, L.; Barrett, B. Impact assessment of humanitarian demining using object-based peri-urban land cover classification and morphological building detection from VHR Worldview imagery. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2022, 27, 100766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Han, F.; Ghazali, K.H.; Mohamed, I.I.; Zhao, Y. A review of convolutional neural networks in remote sensing image. In Proceedings of the 2019 8th International Conference on Software and Computer Applications, Penang, Malaysia, 19–21 February 2019; pp. 263–267. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, M.; Wang, J.F.; Cong, G.; Lv, Y.; Chen, Y. Convolutional neural network for the semantic segmentation of remote sensing images. Mob. Netw. Appl. 2021, 26, 200–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleissaee, A.A.; Kumar, A.; Anwer, R.M.; Khan, S.; Cholakkal, H.; Xia, G.S.; Khan, F.S. Transformers in remote sensing: A survey. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, T.; Yang, Z.; Li, J. Efficient transformer for remote sensing image segmentation. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, M.Z.U.; Islam, S.M.S.; Ul-Haq, A.; Blake, D.; Janjua, N. Effective land use classification through hybrid transformer using remote sensing imagery. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 18, 2252–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Y.; Gang, S.; Guan, C. FCIHMRT: Feature cross-layer interaction hybrid method based on Res2Net and transformer for remote sensing scene classification. Electronics 2023, 12, 4362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Chen, J.; Pan, D. GOFENet: A Hybrid Transformer–CNN Network Integrating GEOBIA-Based Object Priors for Semantic Segmentation of Remote Sensing Images. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Du, S.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, W. Multiscale geoscene segmentation for extracting urban functional zones from VHR satellite images. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Hu, X.; Meng, Q.; Zhang, L.; Shi, W.; Zhao, M. A multimodal fusion framework for urban scene understanding and functional identification using geospatial data. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 127, 103696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Feng, X.; Zhang, C.; Dong, Y.; Huang, J.; Liu, K. Identification of urban functional areas based on the multimodal deep learning fusion of high-resolution remote sensing images and Social Perception Data. Buildings 2022, 12, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Tan, Y.; Wen, Q.; Wang, W.; Li, L.; Li, Z. Deep Multimodal Fusion Model for Building Structural Type Recognition Using Multisource Remote Sensing Images and Building-Related Knowledge. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2023, 16, 9646–9660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Tao, C.; Li, H.; Qi, J.; Li, Y. A unified deep learning framework for urban functional zone extraction based on multi-source heterogeneous data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 270, 112830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, A.; Sun, X.; Wu, H.; Luo, W.; Wang, D.; Zhong, D.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, L.; Zhu, J. Identifying urban building function by integrating remote sensing imagery and POI data. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 8864–8875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Persello, C.; Li, M.; Stein, A. Building use and mixed-use classification with a transformer-based network fusing satellite images and geospatial textual information. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 297, 113767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Persello, C.; Stein, A. Building usage classification using a transformer-based multimodal deep learning method. In Proceedings of the 2023 Joint Urban Remote Sensing Event (JURSE), Heraklion, Greece, 17–19 May 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R.; Ling, J.; Zhang, H. SoftFormer: SAR-optical fusion transformer for urban land use and land cover classification. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 218, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Xu, R.; Feng, C.C.; Zeng, Z. PIF-Net: A Deep Point-Image Fusion Network for Multimodality Semantic Segmentation of Very High-Resolution Imagery and Aerial Point Cloud. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 62, 5700615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, G.; Samadzadegan, F.; Reinartz, P. Deep learning decision fusion for the classification of urban remote sensing data. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 2018, 12, 016038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Xu, H.; Zhou, F.; Xu, S.; Yin, H. A deep-learning-based multimodal data fusion framework for urban region function recognition. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2023, 12, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, H.; Jiang, H.; Yang, G.; Jing, F.; Sun, W.; Lu, C.; Meng, X. A Multi-Source Dynamic Fusion Network for Urban Functional Zone Identification on Remote Sensing, POI, and Building Footprint. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 10583–10599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; He, W.; Li, J.; Zhang, H. Identifying Every Building’s Function in Large-Scale Urban areas with Multi-Modality Remote-Sensing Data. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2024—2024 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Athens, Greece, 7–12 July 2024; pp. 310–314. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal loss for dense object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2980–2988. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, S. Identification of surface thermal environment differentiation and driving factors in urban functional zones based on multisource data: A case study of Lanzhou, China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1466542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Ye, J.; Wang, J.; Wei, Y. Urban functional zone classification based on POI data and machine learning. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Wang, H.; Shang, Y.; Zheng, X. Identification and prediction of mixed-use functional areas supported by POI data in Jinan City of China. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Gong, J.; Hu, X.; Xiong, H.; Zhou, H.; Cao, Z. LuoJiaAI: A cloud-based artificial intelligence platform for remote sensing image interpretation. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2023, 26, 218–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. Pytorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2019, 32, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Ling, Z.; Meng, X.; Kuang, J.; Shi, X.; Yang, Y.; Chen, W.; Wu, Z. Urban Functional Zone Classification Based on High-Resolution Remote Sensing Imagery and Nighttime Light Imagery. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirillov, A.; Mintun, E.; Ravi, N.; Mao, H.; Rolland, C.; Gustafson, L.; Xiao, T.; Whitehead, S.; Berg, A.C.; Lo, W.Y.; et al. Segment anything. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 2–6 October 2023; pp. 4015–4026. [Google Scholar]

- Ravi, N.; Gabeur, V.; Hu, Y.T.; Hu, R.; Ryali, C.; Ma, T.; Khedr, H.; Rädle, R.; Rolland, C.; Gustafson, L.; et al. Sam 2: Segment anything in images and videos. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.00714. [Google Scholar]

- Caron, M.; Touvron, H.; Misra, I.; Jégou, H.; Mairal, J.; Bojanowski, P.; Joulin, A. Emerging properties in self-supervised vision transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 9650–9660. [Google Scholar]

- Oquab, M.; Darcet, T.; Moutakanni, T.; Vo, H.; Szafraniec, M.; Khalidov, V.; Fernandez, P.; Haziza, D.; Massa, F.; El-Nouby, A.; et al. Dinov2: Learning robust visual features without supervision. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.07193. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.