Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Proposes LENet, a novel semantic segmentation network for complex landforms.

- Achieves state-of-the-art performance on PKLD and GVLM datasets with high robustness.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- Introduces axial semantic modeling to enhance long-range contextual dependencies.

- Designs a Feature Expert Compensator (FEC) for deformation-aware intra-class fusion.

- Employs Cross Sparse Attention (CSA) to suppress background noise and refine details.

Abstract

Accurate semantic segmentation of complex landforms in remote sensing imagery is hindered by pronounced intra-class heterogeneity, blurred boundaries, and irregular geomorphic structures. To overcome these challenges, this study presents LENet (Landforms Expert Segmentation Net), a novel segmentation network that combines axial semantic modeling with deformation-aware compensation. LENet follows an encoder–decoder framework, where the decoder integrates three key modules: the Expert Enhancement Block (EEBlock) for capturing long-range dependencies along axial directions; the Feature Expert Compensator (FEC) employing deformable convolutions with channel–spatial decoupled weights to emphasize ambiguous intra-class regions; and the Cross-Sparse Attention (CSA) mechanism that suppresses background noise via multi-rate sparsity masks and enhances intra-class consistency through cosine-similarity weighting. Experiments conducted on the PKLD plateau karst and GVLM landslide datasets demonstrate that LENet achieves IoU scores of 70.39% and 80.95% and Recall values of 83.33% and 91.38%, surpassing eight state-of-the-art methods. These results confirm that LENet effectively balances global contextual understanding and local detail refinement, providing a robust and accurate solution for complex landform segmentation in remote sensing imagery.

1. Introduction

Remote sensing imagery plays a critical role in large-scale terrain analysis, natural disaster monitoring, and environmental assessment [1]. As an essential task in the intelligent interpretation of remote sensing imagery, semantic segmentation aims to assign explicit semantic category labels to each pixel, thereby enabling accurate identification of surface objects and landform types as well as modeling their spatial distribution [2]. This technique has been widely applied to land use classification [3], crop yield estimation [4], urban expansion monitoring [5], and ecological environment assessment [1], becoming one of the core approaches driving intelligent geographic information analysis.

Among various application scenarios, the semantic segmentation of complex landforms (e.g., karst terrains, landslide areas, and post-earthquake regions) is increasingly becoming a research hotspot. In China, for instance, the exposed or near-surface soluble rock covers an area of more than 1.3 million km2, and the widely distributed karst landforms play a vital role in geological surveys, water resource protection, and infrastructure site selection [6,7]. At the same time, landslides, as one of the most common and destructive natural hazards worldwide, also exhibit typical characteristics of complex landforms. Their irregular boundaries and intricate formation mechanisms impose greater challenges on semantic segmentation models [8,9]. Therefore, developing a high-precision semantic segmentation method tailored for complex landforms holds significant scientific value and promising application potential for advancing remote sensing-based geoscientific interpretation.

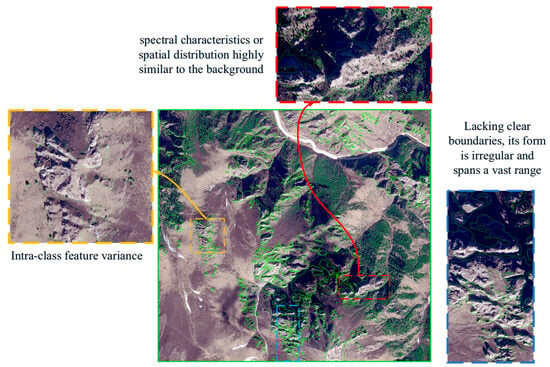

Compared with natural scenes such as forests and farmlands [1,4], or urban scenes such as roads [10] and buildings [3,5], complex landform remote sensing images face significant challenges in semantic segmentation tasks. First, complex landforms exhibit substantial intra-class variations in elevation, scale, spectral reflectance, and texture, which weakens the model’s ability to achieve semantic consistency within the same category. Second, some landform classes share high similarity with the background in terms of spectral characteristics or spatial distribution, making it difficult for traditional feature extraction methods to effectively distinguish landform categories from the background. Finally, complex landform regions often lack clear boundaries, present irregular shapes with vast spatial extents, and may even evolve over time, further aggravating boundary recognition errors and inaccurate regional delineation (as illustrated in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Examples of challenging scenarios in remote sensing image semantic segmentation (selected from the karst dataset PKLD and the public landslide dataset GVLM).

Traditional remote sensing semantic segmentation methods, such as threshold-based approaches [11] and machine learning techniques [12], often rely on fixed parameter settings. Consequently, their performance is usually unsatisfactory when dealing with regions under varying illumination conditions and complex textures. In recent years, deep learning has achieved remarkable progress in remote sensing semantic segmentation, with Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) being widely applied in environmental remote sensing [13], geological remote sensing [14], and urban remote sensing [3,5]. For example, in tasks such as urban building and road extraction [3,5,10,15], small object detection in remote sensing imagery [16], and urban change detection [17], CNN-based models leverage multi-scale receptive fields and spatial pyramid structures to effectively capture spatial context, delivering high segmentation accuracy in structured scenes. However, their receptive fields are inherently constrained by local convolutional kernels, making it difficult to model long-range spatial dependencies. Moreover, CNNs are insufficiently sensitive to features with significant scale variations and blurred boundaries, which can lead to intra-class feature loss and background misclassification in boundary regions. To overcome these limitations, Transformer architectures have been introduced into remote sensing image segmentation owing to their superior global modeling capability [18]. Representative methods, such as Swin Transformer [19], Mix Vision Transformer [20], and DeBifomer [21], employ self-attention mechanisms to enable cross-region information interaction and exhibit strong potential in multi-scale feature aggregation, achieving excellent performance when directly applied to remote sensing semantic segmentation. Nevertheless, for complex landform remote sensing imagery, although attention mechanisms can effectively capture global relationships among target regions, they still fail to address the critical issue of local detail feature loss.

To leverage the complementary advantages of CNNs and Transformers, several studies have explored hybrid architectures that integrate the two. Representative approaches include DC-Swin [22] and ST-Unet [23], which preserve the Transformer’s strength in modeling long-range dependencies while retaining the CNN’s ability to capture local details. However, these methods still pay insufficient attention to indistinguishable intra-class details, and when background and target features exhibit high similarity, they may lead to partial loss of intra-class feature information.

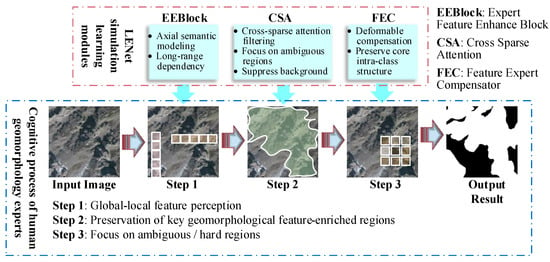

In order to improve the segmentation accuracy of complex terrain remote sensing images while maintaining the integrity of intra-class features, this paper proposes a novel semantic segmentation network, LENet (landforms Expert segmentation Net), based on axial semantic modeling and deformation-aware compensation. Building on previous work integrating CNNS and Transformers. Inspired by the cognitive process of human experts in recognizing complex geomorphic regions, LENet mimics the way experts utilize domain knowledge: they first combine global and local feature distributions to filter most of the background interference, then retain regions rich in geomorphology features, and finally pay special attention to indistinguishable fuzzy intra-class regions. Therefore, in complex landform image segmentation, the key challenge is to quickly eliminate background interference while focusing on complex, fuzzy regions in complex landform classes, which is crucial to improve segmentation performance. Among them, the visualization of the LENet imitating the workflow of human experts and the working principle of each component is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

LENet performs visualizations that simulate the process of human experts identifying features and how each component works, where colored or rectangular areas represent demonstrations of the scope of action.

LENet is built upon a state-of-the-art (SOTA) encoder–decoder architecture, with its key innovation lying in the design of the decoder. As the crucial stage for feature reconstruction, the decoder determines how to effectively restore category information from feature maps rich in semantic representations, which remains a major challenge in complex landform segmentation tasks. To address the wide spatial extent of complex geomorphological regions, we design an expert-enhanced axial semantic modeling module in the decoder to capture both horizontal and vertical contextual information, thereby adapting to large-scale spatial feature distributions. To mitigate noise interference caused by the similarity between background and target features, a cross-sparse attention mechanism is introduced to filter out redundant background information. Furthermore, to handle the rich intra-class scale variations in complex landform categories, a feature expert compensator is proposed to emphasize critical intra-class regions, thereby enhancing semantic consistency within categories. The main contributions of this work can be summarized as follows:

- (1)

- We propose a novel remote sensing semantic segmentation network, LENet, which integrates axial feature modeling with expert-inspired intra-class information identification. By combining an attention-based encoder with strong global modeling capability and a hybrid decoder capable of capturing subtle local features and filtering key information, LENet addresses the challenge of insufficient intra-class recognition integrity in complex landform segmentation.

- (2)

- We design an expert-inspired multi-scale feature learning decoder that mimics the process of expert judgment in distinguishing complex geomorphological features. The decoder incorporates an Expert Feature Enhancement Block (EEBlock), a Feature Expert Compensator (FEC), and a Cross Sparse Attention (CSA) module to improve category integrity and intra-class feature accuracy.

- (3)

- We validate the effectiveness of LENet on a landslide dataset and a karst dataset. Experimental results demonstrate that LENet achieves superior performance across multiple evaluation metrics, confirming its robustness and advancement in complex landform segmentation tasks.

2. Related Works

2.1. Remote Sensing Image Semantic Segmentation

Semantic segmentation can be regarded as a pixel-level extension of image classification, with the goal of assigning a semantic category label to each pixel in the image [3]. Traditional semantic segmentation methods typically rely on manually annotated pixel-level labels and employ deep neural networks to learn the mapping between pixel features and semantic categories. CNN-based approaches have achieved remarkable progress in remote sensing image analysis [22,23,24,25], by constructing multi-layer convolutional architectures to extract and classify local features on a per-pixel basis. With further research, many studies have attempted to enhance contextual modeling capability and enlarge the receptive field to improve semantic understanding among pixels. U-Net introduces skip connections to integrate multi-scale contextual information [24], becoming a classical model for semantic feature enhancement through multi-scale fusion. SegNeXt employs large-kernel strip convolutions to expand the receptive field [26]. BiSeNet proposes a dual-branch structure to balance spatial detail preservation and semantic understanding efficiency [27], while EncNet enhances semantic category-related feature representation through a context encoding module [28].

Since the introduction of Transformer architectures into visual tasks, their reliance on self-attention mechanisms has demonstrated remarkable advantages in modeling long-range dependencies [18,29,30], gradually becoming a pivotal direction in the design of semantic segmentation models. However, Transformers incur substantial computational costs when processing high-resolution images, which limits their practical deployment in remote sensing applications. To address this issue, the researchers proposed a series of lightweight optimization strategies: In addition to the classic moving window mechanism adopted by Swin Transformer [19], Biformer utilizes a novel dynamic sparse attention mechanism achieved through a two-layer routing approach, enabling more flexible and content-aware computational allocation [31]; RMT introduces a spatial decay matrix and designs a spatially constrained attention decomposition structure to enhance long-range modeling efficiency [32]; Zhu et al. integrate CNNs with Transformers to extract high-frequency details and low-frequency semantic features separately, achieving a unified representation of global context and fine-grained structures [33].

Although the aforementioned methods achieve excellent performance in natural image semantic segmentation, they often struggle when directly applied to remote sensing imagery due to the unique challenges of such data, including high intra-class variance, significant scale variations, blurred object boundaries, and complex backgrounds. In addition, remote sensing images typically possess ultra-high resolution, which further increases model parameters and computational costs, thereby limiting the practicality and scalability of these approaches.

To address the unique challenges of remote sensing imagery, numerous scholars have proposed targeted design strategies. For instance, in urban remote sensing scenarios, common issues include high inter-class similarity, large intra-class variation, and dense small objects [5,22,34]. Wang et al. introduced a parallel window attention structure to enhance the spatial modeling capability of Swin Transformer [35], thereby improving urban remote sensing image segmentation performance. Rau et al. incorporated DEM auxiliary information to achieve hierarchical segmentation for multimodal landslide disasters [36]. Cui et al. developed a cross-modal transfer learning framework for semantic segmentation [37], introducing channel and spatial discretization losses to alleviate inter-modal feature conflicts and redundancy, thus enhancing modality-cooperative modeling. He et al. employed prompt learning mechanisms and explicit semantic grouping strategies to adapt frozen pre-trained models to multimodal downstream tasks [38]. Ma et al. combined the strengths of CNNs and Transformers to propose a hybrid architecture that improves multimodal fusion efficiency [15]. In addition, Zhang et al. utilized infrared remote sensing imagery for vehicle detection [39], Zheng et al. designed a foreground-aware relational modeling network to tackle scale variations and foreground class imbalance in remote sensing images [40], and Chen et al. introduced a prompt-driven mechanism based on the SAM architecture for instance segmentation in remote sensing imagery [41].

To enhance the spatial sampling capability of convolutional neural networks, Dai et al. proposed Deformable Convolutional Networks (DCN) [42], which learn unsupervised offsets from target tasks to expand the spatial sampling positions of convolutional layers, demonstrating strong potential in remote sensing semantic segmentation. Yu et al. leveraged deformable convolutions to achieve global and deformation-aware feature extraction [10], improving road extraction performance in remote sensing imagery. Dong et al. introduced a multi-scale deformable attention module [43], utilizing a larger deformable receptive field to adapt to remote sensing targets of diverse shapes and sizes, thereby generating more precise attention maps. Hu et al. proposed a multi-scale deformable self-attention mechanism to reduce the partial loss of linearly intertwined road information in remote sensing images [44], effectively enhancing the saliency of road features relative to the surrounding environment. Although deformable convolutions have been widely applied in remote sensing semantic segmentation, most applications focus on complex object shapes or objects densely intertwined with the background, while their substantial potential for handling intra-class feature variations within target categories remains underexplored.

In summary, although recent advances in CNNs and Transformer architectures have significantly promoted the development of remote sensing semantic segmentation, most existing studies focus on man-made or natural land cover types with regular boundaries and clear structures, such as urban buildings, roads, and agricultural areas. Effective modeling strategies remain lacking for complex landforms, which exhibit irregular textures, atypical features, blurred boundaries, and high intra-class variance. While deformable convolutions have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in road recognition tasks, their potential for learning critical intra-class regions has yet to be fully explored. Consequently, directly applying existing methods to complex landform remote sensing imagery often fails to achieve satisfactory segmentation performance.

2.2. Semantic Segmentation of Complex Landforms

Semantic segmentation of complex landform regions in remote sensing imagery is a highly challenging task, due to the spatial heterogeneity of multiple landform types, blurred boundaries, significant scale variations, and high intra-class variance. Areas exhibiting typical complex landform characteristics, such as landslide-prone zones, plateau karst regions, and desert hilly landscapes, are of particular interest, as accurate semantic understanding and fine-grained segmentation in these regions play a crucial role in disaster monitoring, resource surveying, and ecological assessment.

In geohazard-related complex landforms, remote sensing monitoring and semantic segmentation of landslide-prone areas have become a major research focus. Landslide occurrences are typically accompanied by abrupt changes in surface morphology, posing significant threats to human life and property, making their mapping and dynamic change detection highly practical. Zhang et al. proposed a prototype-guided region-aware progressive learning method based on multi-scale target domain adaptation to address cross-domain modeling of landslide regions in large-scale remote sensing imagery [8]. Lu et al. designed a lightweight network, MS2LandsNet, specifically for landslide landform features [14]; by reducing the number of channels and optimizing the network architecture, combined with multi-scale feature fusion and channel attention mechanisms, the model’s performance in landslide detection tasks was significantly improved. Şener et al. developed LandslideSegNet [45], which integrates an encoder–decoder residual structure with spatial–channel attention mechanisms to enhance early identification of potential landslide regions. Soares et al. evaluated the generalization performance of automated landslide mapping models across three landform types incorporating NDVI and DEM data, demonstrating that NDVI information helps mitigate overfitting and improves prediction balance [46].

Research on remote sensing segmentation of non-hazard-related complex landforms has also been continuously expanding. Huang et al. addressed the challenge of multi-scale representation of landscape landform features by proposing the SwinClustering framework based on Swin Transformer [19], enhancing the model’s ability to jointly capture spatial structure and semantic information [47]. Cheng et al. designed an improved semantic segmentation framework that employs statistical preprocessing to remove invalid image patches during training [48], thereby improving the model’s capacity to capture local details of fracture-like features. Yu et al. introduced SegRoadv2 for road segmentation [10], incorporating deformable self-attention and grouped deformable convolution structures to enhance the perception of irregular road boundaries. Goswami et al. utilized a U-Net architecture to construct segmentation models for typical landform types, including deserts, forests, and mountainous regions [49]. Zhou et al. proposed a network based on a dense attention residual pyramid fusion structure for Lithological Unit Classification (LUC) [50], a task of significant relevance in geological resource exploration. While these methods have achieved remarkable results across various complex landform types, they differ from the focus of this study, which aims to develop a generalized segmentation model capable of handling diverse complex landforms. Specifically, this work proposes a semantic segmentation method for complex landform remote sensing imagery that not only improves segmentation accuracy but also preserves intra-class feature integrity.

3. Methodology

3.1. Framework Overview

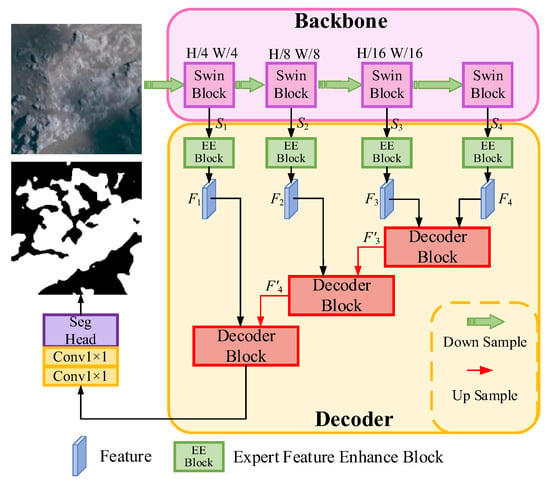

The overall architecture of LENet (as illustrated in Figure 3) adopts the widely used encoder–decoder structure for semantic segmentation tasks [26,50,51]. For the input raw imagery, the encoder progressively downsamples the feature maps to effectively capture multi-scale contextual information, producing abstract semantic features at different scales Si (i = 1, 2, 3, 4). The decoder then progressively upsamples and fuses these features, combining high-level semantic information from the encoding stage with low-level spatial details, thereby gradually restoring the spatial structure of the target. This process achieves a balance between global semantic modeling and local detail preservation. Such characteristics make the encoder–decoder framework particularly suitable for complex landform segmentation, as it maintains high-level semantic abstraction while retaining essential local details.

Figure 3.

The overall flowchart of LENet. LENet adopts an encoder–decoder structure, and the encoder uses Swin Transformer-tiny by default. The decoder part consists of an Expert Feature Enhancement Block (EEBlock) and a Decoder Block. EEBlock is responsible for performing axial semantic enhancement on the features extracted by different-stage encoders, and then inputting them into the Decoder Block to further restore the spatial structure.

To accommodate the need for modeling long-range dependencies in complex landforms, the encoder of LENet adopts Swin Transformer as its backbone. Compared with traditional convolutional neural networks [19], Swin Transformer offers superior global dependency modeling capabilities. Moreover, its shifted window attention mechanism significantly reduces computational and memory costs, achieving a balance between efficient processing and effective global context modeling.

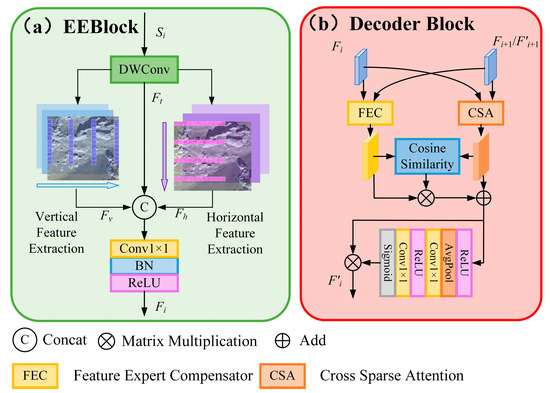

The decoder of LENet consists of two core components: the EEBlock and the Decoder Block (as illustrated in Figure 4). The EEBlock employs axial semantic modeling to extract semantic features along both horizontal and vertical directions, enabling efficient long-range dependency modeling and enhancing the representation of morphologically irregular and spatially extensive landform categories. The Decoder Block comprises two parallel modules: the FEC and CSA. FEC reinforces intra-class feature representation through cross-scale feature fusion and adaptive compensation, mitigating information loss and inconsistencies caused by significant intra-class variations. CSA models the correlations between multi-scale features based on cross-sparse attention, enhancing the discriminability of key regions while suppressing background interference. Finally, a cosine similarity mechanism integrates the compensated intra-class semantic information into the selected features, achieving synergistic intra-class compensation and key region enhancement. This design maintains global modeling capabilities while effectively strengthening local detail representation, thereby improving the semantic segmentation accuracy of complex landform regions.

Figure 4.

The structural details of EEBlock and Decoder Block. (a) The part here represents the structural details of EEBlock, which includes Depthwise Convolution (DWConv) and horizontal and vertical feature extractors. Its structure is designed to enhance the network’s ability to model long distances. (b) Section presents the structural details of the Decoder Block, which consists of a FEC, CSA, and Cosine Similarity Weighted Part. This structure is used to maintain global modeling while enhancing local important details.

3.2. Expert Feature Enhancement Block (EEBlock)

To address the challenges of extensive spatial coverage and irregular category shapes in complex landform remote sensing imagery, we designed an EEBlock to improve the network’s ability to model long-range semantic information, thereby strengthening intra-class long-distance dependencies.

Traditional convolutional networks excel at capturing local features but struggle to model long-range semantic relationships, whereas self-attention mechanisms can achieve long-range modeling but incur significant computational costs as feature map size increases. To leverage the complementary advantages of convolutional networks and self-attention, inspired by MSCAN [26], we designed horizontal and vertical convolutions to simulate self-attention for capturing long-range dependencies along both directions. As illustrated in Figure 4a, the input feature Si is first processed by a Depthwise Convolution (DWConv) to aggregate local information, producing Ft. The DWConv can be expressed by Equation (1):

where the input feature tensor Si is a four-dimensional tensor (b, c, h, w). In Si, h + m − [kh/2] and w + n − [kw/2] denote the actual coordinates in the height and width dimensions of the input feature map when the convolution kernel is centered at (h, w). The convolution kernel parameter represents the weight value at position (m, n) of the kernel with size [kh, kw] in the c-th channel.

Then, Ft will be processed by a series of parallel vertical and horizontal feature extractors, which, respectively, construct long-range dependency models in the vertical and horizontal directions. Each feature extractor is composed of rectangular DWConvs, which can effectively replace large kernel convolutions using the independent channel convolutional kernel structure of DWConvs, with kernel sizes of [1, 11] and [11, 1], respectively. These parameters were determined through testing, aiming to balance the effective receptive field and computational resource consumption. At the same time, this strip-shaped convolutional kernel design can effectively extract long-structured information in both horizontal and vertical directions. If it were just a regular convolution, multiple layers of stacking or the use of an extremely large kernel would be required to achieve a similar receptive field. After the processing by the feature extractors, Ft will generate horizontal and vertical enhanced features Fv and Fh. By connecting Ft, Fv, and Fh along the channel dimension and applying a 1 × 1 convolution, the comprehensive feature Fi (i = 1, 2, 3, 4) can be obtained (it enhances the long-range semantic relationships of complex terrain categories in both directions and alleviates the loss of feature correlation due to significant scale changes). The extraction of axial semantic information in the horizontal and vertical directions can refer to Formulas (2) and (3):

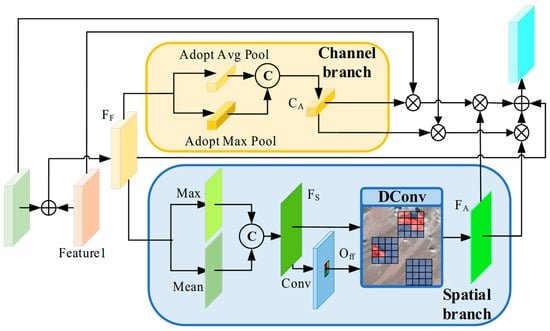

3.3. Feature Expert Compensator (FEC)

In complex landform remote sensing imagery, intra-class information loss and inconsistency—such as in karst regions where surface spectral features exhibit minimal contrast with the background and texture boundaries are ambiguous—pose challenges for models to effectively capture deep semantic correlations among pixels of the same class. Traditional convolutional operations often struggle to focus on fine-grained regions with low intra-class discriminability, leading to insufficient feature representation and loss of spatial details. Furthermore, in remote sensing images, multi-scale landform features can differ significantly in their representation, with the same class exhibiting distinct geometric shapes and texture patterns at different scales. Direct feature fusion in such cases can easily induce semantic misalignment or redundant amplification, further exacerbating semantic information loss across scales. To address these issues, we propose the FEC module, which employs deformable convolutions to emulate the expert identification of hard-to-recognize intra-class regions, thereby enabling more effective cross-scale feature integration and enhancing the model’s ability to capture intra-class structural information in complex landforms.

As illustrated in Figure 5, the FEC employs a parallel mechanism that decouples channel and spatial weights, guiding the network to focus on feature channels with higher semantic discriminability while compensating for spatial information in regions that are difficult to learn. First, the input multi-scale features Feature1 and Feature2 are summed to obtain the fused feature FF. In the channel branch, FF undergoes adaptive average pooling and adaptive max pooling, followed by concatenation and weighting to generate the channel weight CA. In the spatial branch, FF is processed by computing both the maximum and average values, which are then concatenated to obtain FS. FS is further passed through an additional convolution to produce the spatial offset Off, and the concatenated feature together with the spatial offset is input into a Deformable convolution (DConv) to perform weighted learning of intra-class spatial information, resulting in the intra-class spatial feature compensation weight FA. Subsequently, the obtained FA and CA are multiplied by the original inputs Feature1 and Feature2, respectively, and then summed to integrate semantic information. Adding the residual of FF yields the Output, representing the fully compensated intra-class feature. Through this mechanism, the FEC balances the channel relationships after multi-scale feature fusion and mitigates intra-class information loss along the spatial dimension, thereby achieving more accurate recognition of intra-class features.

Figure 5.

Workflow diagram of the FEC. FEC learns the intra-class difficult-to-classify pixel regions by learning channel weights, spatial information and using deformable convolution, thereby reducing intra-class inconsistency and intra-class information loss.

The generation of the spatial offset and the application of deformable convolution are expressed in Equations (4)~(6):

The deformable convolution used to generate the spatial compensation weights differs from traditional convolution in that it learns spatial offsets from the spatial feature information through an additional convolutional layer. The input channel number of this convolutional layer is 2 × K (where K is the kernel size, e.g., K = 9 for a 3 × 3 convolution), and each offset at a given position contains both horizontal and vertical components. These offsets are optimized via backpropagation during training, allowing the convolutional kernel to adaptively adjust its sampling locations based on the input features. For a traditional convolution, the output feature map y at position p0 given an input feature map x is computed as in Equation (7):

here, w represents the convolution kernel weights, and x denotes the weighted sum of the input features within a local neighborhood (pn). This allows the convolution to focus on details within the neighborhood but does not permit weighted sampling of different regions within it. Deformable convolution addresses this limitation by introducing Δpn into the convolution, making the sampling locations p0 + pn + Δpn. This enables the kernel to adaptively focus on specific regions within the neighborhood, as shown in Equation (8):

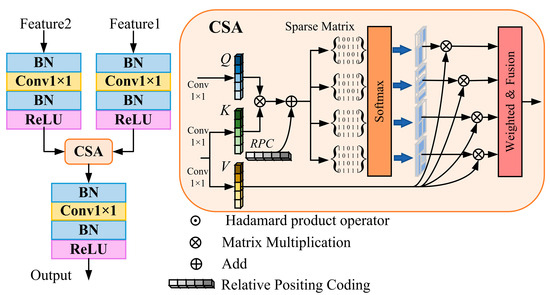

3.4. Cross-Sparse Attention (CSA)

In complex landform remote sensing images, landform regions are often accompanied by numerous background features that are similar to the target class. Most feature fusion methods tend to capture these redundant features during global feature modeling, which introduces noise and weakens the representation of key features. To address this issue, we designed a CSA mechanism to reduce the interference from background noise. Traditional cross-attention computes using the full attention weights and cannot filter out irrelevant background noise. Sparse attention, often used to reduce computational complexity in attention mechanisms [52,53], leverages sparse attention maps and has demonstrated effectiveness in tasks such as image denoising [54,55], helping models remove irrelevant noise. Inspired by Top-K sparse attention [56], we propose CSA to filter out irrelevant noise among multi-scale features processed by the expert feature enhancer, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Flowchart of the CSA. On the left side, it represents the complete process of this module, while on the right side, it shows the specific calculation process of cross-sparse attention. CSA can reduce the interference of useless background information by introducing sparse matrices, and normalization and standard convolution groups help this module enhance the feature expression ability.

Unlike traditional cross-attention, which relies on the full attention mask for computation, CSA introduces multiple sparse-rate masks and applies weighted aggregation. Masks with higher weights, corresponding to relevant class information, are retained, while irrelevant background noise is assigned to masks with lower weights. This approach reduces computational complexity and suppresses interference from unrelated features. Such a design effectively diminishes noise in the attention weights, enhances the model’s selective learning of semantic information, and thereby improves the discriminative capability for complex landform regions.

Specifically, Feature1 and Feature2 represent the input multi-scale features. Each is first processed through normalization and a standard convolution module (Conv-BN-ReLU) for channel integration. Then, a 1 × 1 convolution layer maps the features to generate the Query (Q), Key (K), and Value (V), which serve as the inputs to CSA. Feature1 generates Q, while Feature2 generates K and V. The attention map is obtained by multiplying Q with K, followed by the addition of relative position encoding to establish the spatial relationships between features. Subsequently, four sparse-rate mask matrices are applied to selectively filter elements in the attention map, which are then multiplied with V. Finally, the attention maps from different sparse rates are fused via weighted multiplication to produce the output features, which are again processed through normalization and a standard convolution module for non-linear enhancement, thereby improving the representation of relevant features. The CSA can be formally defined as in Equation (9):

here, Q represents the query token generated from Feature 1, while K and V represent the key and value tokens generated from Feature2. B denotes the relative position encoding. Si corresponds to the i-th (i = 1, 2, 3, 4) sparse-rate mask matrix, and ωi represents the attention weight associated with the i-th sparse-rate mask.

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Datasets

We evaluated LENet on a karst dataset and a landslide dataset. Karst landforms are often associated with faults [57], folds, and other geological structures, exhibiting markedly discontinuous and irregular distributions characteristic of complex landforms. Landslides typically occur in geologically fragile or steep terrain areas, with distributions that are patchy, fragmented, and uneven. Multiple-phase or repeated composite landslides may occur within the same region, resulting in dynamically evolving landform patterns that also exhibit complex landform characteristics.

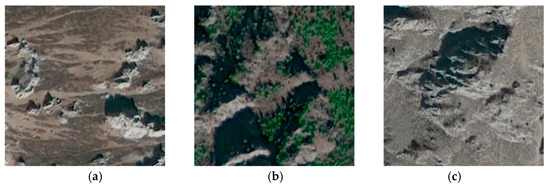

4.1.1. Karst Landform

Exposed karst landform segmentation in remote sensing imagery is a highly challenging task due to its complex characteristics, including large intra-class variance, uncertain boundary information, and a complex surrounding background, making it an excellent subject for studying complex landform segmentation. We extended the PKLD karst dataset originally created by Zhong et al. [57]. The expanded PKLD contains 17,720 karst images of size 256 × 256 pixels, with a training, validation, and test split of 6:2:2, i.e., 10,632 images for training, and 3544 images each for validation and testing. This area is located in Gongjue County, Chamdo, Tibet Autonomous Region, China, where the surface karst landforms are mainly composed of limestone peaks and limestone debris accumulations. To account for the wide distribution of karst landforms, the dataset includes images from diverse mountain backgrounds, as shown in Figure 7, including karst on bare mountains (Figure 7a), karst partially covered by vegetation (Figure 7b), and karst in pronounced stone forest regions (Figure 7c).

Figure 7.

Schematic diagrams of remote sensing images of karst landforms under different background types. (a) Karst on bare mountains (b) Karst partially covered by vegetation (c) Karst in pronounced stone forest regions.

4.1.2. Landslide Landform

To evaluate the generalization capability of LENet on complex landform segmentation, we selected landslide landforms as an auxiliary test. Landslide areas are widely distributed and also exhibit the challenging characteristics typical of complex landform segmentation. We employed the publicly available GVLM landslide dataset [8], which contains numerous landslide sites across six continents, including Asia, Africa, North America, South America, Europe, and Oceania, covering diverse countries and regions. This dataset is well-suited for segmentation tasks of landslide-related complex landforms under varying background conditions. For our experiments, we curated 2690 images of size 256 × 256 pixels from GVLM and randomly split them into training, validation, and test sets in a 6:2:2 ratio using a fixed random seed, thereby demonstrating LENet’s generalization capability for landslide complex landform segmentation.

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

In this study, we employed four commonly used metrics—Intersection over Union (IoU), Precision, Recall, and F1 score—as the core evaluation criteria to assess the performance of the proposed method.

IoU primarily measures the degree of overlap between the predicted region and the ground truth, serving as an important indicator of overall segmentation accuracy. Its calculation is expressed as follows (Equation (10)):

here, True Positives (TP), False Positives (FP), and False Negatives (FN) represent the number of correctly classified pixels, incorrectly classified pixels, and missed pixels, respectively.

Precision emphasizes the purity of the model’s predictions, that is, its ability to reduce false detections. Its formula is expressed as:

Recall reflects the model’s ability to cover positive samples, that is, the completeness of target detection. Its formula is expressed as:

The F1 score, as the harmonic mean of Precision and Recall, provides a balanced measure that considers both metrics simultaneously. It prevents overemphasis on high Recall at the expense of Precision, and vice versa. Thus, F1 can achieve a balance between Precision and Recall to a certain extent. Its formula is expressed as:

4.3. Loss Function

In this study, we employ the standard cross-entropy (CE) loss to optimize the binary semantic segmentation model. CE loss is one of the most commonly used loss functions in classification and segmentation tasks, and its core idea is to measure the discrepancy between the predicted probability distribution and the true label distribution. Given a training set containing N samples and C = 2 classes, the cross-entropy loss is defined as follows:

here, yi,u denotes the ground truth label of sample i for class u (u = 1, 2), and pi,u represents the probability predicted by the model for sample i belonging to class u after the Softmax function. N is the total number of samples, and C is the total number of classes. This loss function effectively constrains the model’s learning process, guiding the predictions to gradually approach the true distribution, thereby improving segmentation accuracy.

4.4. Implementation Details

All experiments in this study were implemented using the PyTorch 2.9.1 framework and executed on a workstation equipped with an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 5080 GPU with 16 GB of memory. The input images were set to a size of 256 × 256 pixels, with a batch size of 16. After multiple trials, a training schedule of 150 epochs was selected to ensure that the model neither overfits nor underfits. The AdamW optimizer was used with an initial learning rate of 0.00006. During training, data augmentation strategies such as random flipping and photometric distortion were applied to enhance the model’s generalization capability.

4.5. Experimental Results and Analysis

To demonstrate the effectiveness of our method for semantic segmentation of remote sensing images containing complex landforms such as plateau karst and landslide-prone areas, we compared it with several SOTA segmentation models developed in the past five years, as listed below:

- (1)

- SegNeXt [26]: This network employs a multi-scale convolutional encoder to achieve spatial attention. It maintains relatively low computational complexity while effectively capturing object details, enabling efficient image semantic segmentation.

- (2)

- Swin Transformer [19]: This network utilizes a shifted-window attention mechanism, offering flexibility for multi-scale modeling, thereby enabling effective image semantic segmentation.

- (3)

- SegFormer [20]: By combining a Transformer with lightweight Multi-layer Perceptrons (MLPs), this network integrates local and global attention in a simple, lightweight design to achieve efficient semantic segmentation.

- (4)

- Mask2Former [58]: This network employs a mask-based attention mechanism to extract local features, addressing semantic segmentation tasks across diverse domains.

- (5)

- K-Net [59]: This network uses a set of learnable kernels to achieve consistent segmentation across different semantic categories.

- (6)

- Segmenter [60]: The model performs global context modeling at both the first layer and throughout the network, effectively handling semantic segmentation tasks on small image regions.

- (7)

- QSD [61]: This network introduces a dual-optimization strategy to correct the information distribution in quantized pulse-driven self-attention, enabling efficient performance while maintaining high energy efficiency for semantic segmentation tasks.

- (8)

- LOGCAN++ [3]: The network implements a local–global perception strategy, using local class centers as intermediate perception elements to suppress intra-class differences, thereby achieving higher semantic segmentation accuracy.

4.5.1. Quantitative Analysis

Compared with the mainstream semantic segmentation methods, the segmentation efficiency of LEnet is more outstanding. For instance, compared with the Swin Transformer using the UperNet decoder, our floating-point operations (FLOPS) have decreased by 46.541 G, accounting for only about 22.4% of the total FLOPS of Swin Transformer. At the same time, the number of parameters (Params) has decreased by 10.619 M, accounting for approximately 82% of the total parameters of Swin Transformer. However, the inference speed relative to Swin Transformer is not significantly reduced. Its inference speed still ranks third among all the models we compared. Therefore, it proves that using the strip convolution to simulate the attention feature expert enhancer significantly reduces the computational complexity of long-distance feature modeling. Moreover, the CSA with sparse matrices suppresses irrelevant background noise during the multi-scale feature fusion process, thereby achieving more efficient segmentation for complex landform remote sensing images. The detailed comparison results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Compare FLOPs and Params with the models that achieve high performance on our karst dataset. At the same time, we also tested the inference speeds of different models. The input image size is 256 × 256 × 3.

Compared with Swin Transformer (using the UperNet [25] decoder), the LENet model achieves a 1.3% improvement in IoU, a 0.92% increase in F1 score, and a 1.8% gain in recall on the PKLD karst dataset. This improvement is attributed to LENet’s axial semantic modeling mechanism, which captures long-range dependencies overlooked in the UperNet design. Although UperNet leverages multi-scale features through FPN and PPM structures, it does not explicitly focus on key intra-class information during multi-scale feature fusion. LENet addresses this limitation with the Feature Expert Compensator, enabling more complete intra-class feature representation, which is reflected in the notable increase in recall. On the GVLM landslide dataset, LENet achieves a 0.42% improvement in IoU, a 0.26% increase in F1, and a 0.27% gain in recall. Compared with karst geomorphology, landslide regions exhibit more distinct spectral differences; for example, karst areas may contain partial vegetation coverage, whereas landslide regions rarely have obvious vegetation due to their formation mechanism. This results in generally higher performance metrics for landslide segmentation compared with karst segmentation across different models.

Overall comparison with other SOTA semantic segmentation models shows that LENet achieves excellent performance across comprehensive metrics such as F1, IoU, and mIoU, demonstrating its advancements in complex geomorphology segmentation tasks. It is noteworthy that, as shown in Table 2 and Table 3, LENet does not always achieve the highest precision. This is because precision and recall represent a dynamic trade-off, and due to the unique distribution of pixels in complex geomorphological areas, higher recall and F1 scores often correspond to results that more accurately reflect the true complex geomorphological classes. The comparative experiments on the PKLD karst dataset are presented in Table 2, while those on the GVLM landslide dataset are shown in Table 3.

Table 2.

The performance was compared with advanced performance models under the karst dataset we produced, with the core metrics being IoU, Recall and F1 score (Unit: %).

Table 3.

A comparative experiment was conducted on the public dataset of GVLM decline with Iou, Recall and F1 as the core evaluation metrics (Unit: %).

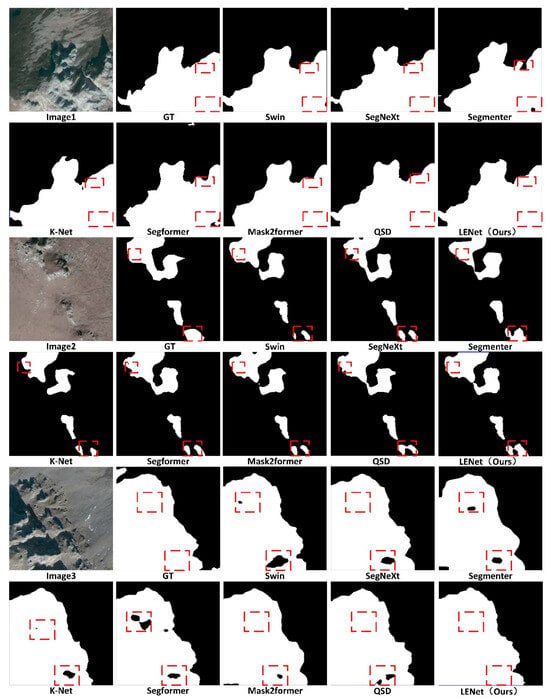

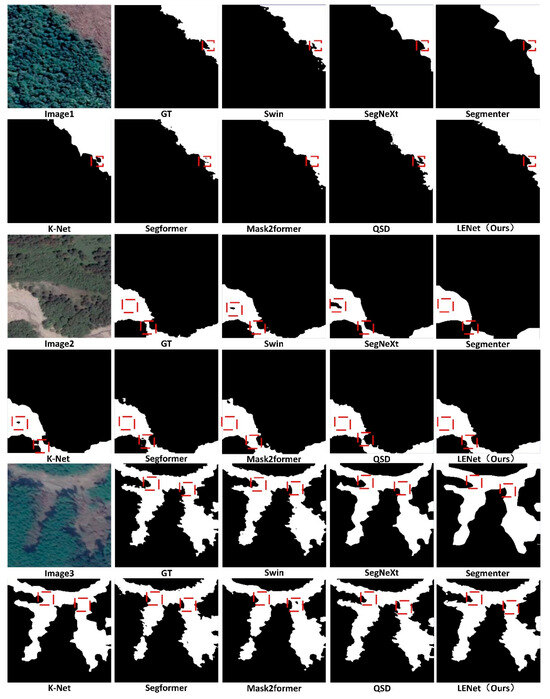

4.5.2. Qualitative Analysis

As shown in Figure 8 and Figure 9, we selected three representative images from each dataset to compare the segmentation performance of LENet with other models for karst and landslide complex geomorphologies, where GT denotes the Ground Truth. Figure 8 corresponds to the karst dataset, and Figure 9 corresponds to the landslide dataset.

Figure 8.

Visualization effect of semantic segmentation results of kast landforms using different models on the validation set (the white part represents the karst area, the black part represents the background, and the red box line represents the key area).

Figure 9.

Visualization effect of semantic segmentation results of landslide landforms using different models on the validation set (the white part represents the landslide area, the black part is the background area, and the red box lines are the key areas).

For the first image in Figure 8, there are significant intra-class feature differences, and some boundary information overlaps with shadows, increasing the difficulty of boundary segmentation. Segmenter and K-Net encounter boundary confusion and intra-class inconsistency, respectively. LENet, in contrast, maintains better intra-class integrity and avoids background misclassification issues seen in SegNeXt. In the second image, the spectral difference between the karst region and its background is small, and the karst regions are distributed sparsely, making it harder for models to learn long-range semantic relationships, which can lead to intra-class information loss. Swin Transformer, Segformer, Mask2former, and QSD all show intra-class misclassification, splitting a single continuous karst region into disconnected parts. LENet, while showing minor intra-class loss in the bottom-right area, successfully preserves most intra-class information and achieves the best intra-class completeness in the larger karst region in the upper-left. In the third image with a complex background, karst regions display noticeable intra-class spectral and texture variations and interference from similar background features. Most segmentation models suffer from some degree of intra-class information loss, whereas LENet produces the most accurate intra-class information consistent with the ground truth.

Regarding the landslide segmentation results in Figure 9, the first image shows a landslide region adjacent to vegetated areas. While spectral differences are clear, regions near the connecting boundaries are prone to intra-class misclassification; K-Net and Segformer misclassify parts of the boundary-adjacent areas, whereas LENet preserves intra-class integrity and yields segmentation results closer to the true boundaries. In the second image, the landslide morphology is irregular and connected regions are prone to misclassification, with intra-class spectral variations resembling background ground features. Swin Transformer and SegNeXt misclassify parts of the intra-class regions, and Segmenter shows severe feature loss at the landslide connections. LENet, however, maintains intra-class completeness while retaining local detail at connections. In the third image, some intra-class regions are shadowed, which increases the likelihood of intra-class information loss, and boundary shapes are highly irregular. Mask2former shows significant intra-class feature loss, resulting in fragmented landslide regions, while SegNeXt, Segmenter, and K-Net produce overly coarse boundaries. LENet, by contrast, preserves intra-class features and produces boundary segmentation results closer to the ground truth.

Overall, these comparative analyses demonstrate that LENet excels in segmenting complex geomorphologies in diverse and complex remote sensing backgrounds, providing superior semantic recognition and visualization performance.

5. Discussion

In this chapter, we will discuss the ablation experiments of the model and the overall discussion of the final results.

5.1. Ablation Study

To further demonstrate the contributions of each component in the LENet to its performance in recognizing complex landscapes, we conducted a series of ablation experiments on the Karst validation dataset. These experiments involved ablation treatments of the entire network architecture, the FEC, the CSA module parameters, and the effective receptive field of the EEBlock. The experimental results are helpful in determining the most effective model design. This section will detail the settings and results of the ablation experiments.

5.1.1. Ablation of the Model Structure

We first conducted ablation experiments on the network architecture to demonstrate the contributions of the FEC, the EEBlock, and the CSA module to the task of complex geomorphology segmentation. Five ablation configurations were designed to evaluate the effectiveness of each component, using IoU, F1, and Recall as evaluation metrics: (1) Using both the FEC and CSA. (2) Using only the Feature Expert Compensator. (3) Using the EEBlock and CSA. (4) Using only the EEBlock (5) Using only the CSA module. The results of these ablation experiments are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Ablation experiments on the overall structure of the model (where √ is used and × is not used).

Analysis of the above ablation results indicates the following: when only the FEC is retained, the model can still fuse multi-scale features via the intra-class information compensation mechanism, resulting in an IoU higher than that achieved by retaining only the EEBlock or only the CSA module. This improvement arises because the intra-class feature compensation ensures semantic consistency within each category. However, F1 and Recall scores are lower than when either EEBlock or CSA is used alone, due to insufficient global modeling capability and incomplete global feature representation.

When both FEC and CSA are used simultaneously, all evaluation metrics surpass those of the other ablation configurations, demonstrating that the intra-class information compensation and background noise suppression mechanisms are complementary and constitute the core of LENet. Meanwhile, EEBlock, when working together with FEC and CSA, further enhances axial long-range semantic information, enabling more complete intra-class feature modeling.

5.1.2. Ablation of the Feature Expert Compensator

For complex remote sensing images of geomorphologies with large intra-class differences at different scales, sampling stages often encounter significant spectral and texture variations. These variations can lead to abstracted semantic features and difficulty in intra-class recognition, causing intra-class feature information loss, such as inconsistency within classes or misclassification with the background.

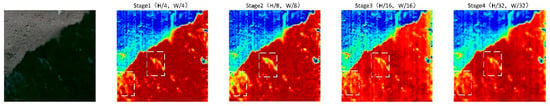

We visualized the semantic feature maps learned at the four stages of the backbone network, as shown in Figure 10. As network depth increases, the lost intra-class information fails to receive sufficiently high semantic weight, reducing its correlation with other regions of the same class and resulting in intra-class inconsistency.

Figure 10.

Visualization of feature maps at different stages, where the white box lines represent the key boundary displacement areas, the red part is the part with high class probability, and the blue part is the part with low probability.

Many studies address the loss of fine-grained information by employing residual structures and feature addition to retain detail. While effective for preserving shallow feature details, this approach is insufficient for complex geomorphological remote sensing images where boundary information is intricate and uncertain, and intra-class spectral, texture, and scale variations are pronounced. In such cases, it cannot focus on regions prone to semantic information loss.

To address this, we designed ablation experiments comparing residual addition and feature summation with the FEC that uses learned displacement offsets via DConv. These experiments aim to demonstrate that FEC’s ability to learn spatial offsets better compensates for information loss during sampling. We also designed an ablation removing DConv to verify that weighted attention to intra-class information improves segmentation performance. The specific experimental variants are: (1) replacing the FEC with residual addition, and (2) replacing the DConv in FEC with a single-channel summation of max-pooled and average-pooled spatial information. The experimental results are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Ablation experiment of FEC (where √ is used and × is not used).

Analysis of the ablation experiments on the FEC indicates that its channel–spatial weight separation strategy effectively improves the utilization of multi-scale features, yielding segmentation results closer to the ground truth. Moreover, the deformable convolution in the spatial weight branch, which learns spatial offsets to adaptively weight the convolution kernel, significantly enhances intra-class completeness, as reflected by the noticeable improvement in recall.

5.1.3. Parameter Ablation of Cross-Sparse Attention

In the CSA module, we investigated the impact of different numbers of sparse matrices on modeling and learning the contextual information of spatial offsets. In the experiments, the number of sparse matrix groups was set to 1~5, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Ablation experiments of cross sparse attention (Unit: %).

The analysis of the above ablation experiments shows that as the number of groups increases, the model’s performance first improves and then declines. This is because using too many sparse matrices may cause some relevant features near the weight threshold to be filtered out, and the loss of these features negatively affects the model’s segmentation results.

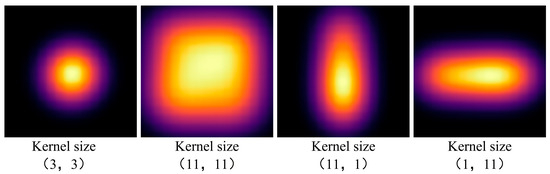

5.1.4. Kernel Size Parameter Effective Receptive Field Ablation Experiments for EEBlock

In EEBlock, we use two banded convolutions to replace the effective receptive field of the large kernel convolution. To demonstrate its effectiveness, the effective receptive fields of standard DWconv, large kernel DWconv, and horizontal and vertical feature extraction strip convolutions are visualized, as shown in Figure 11. And the FLOPs, the number of parameters, and the replacement effect are calculated in Table 7, respectively.

Figure 11.

Visualization of effective receptive fields for DWConv with different kernels.

Table 7.

Ablation experiments with different kernel parameters and effects of EEBlock.

Ablation experimental results and visualization on EEBlock show that the parallel use structure of horizontal and vertical feature extractors can simulate the effective receptive field of a large kernel convolution, and its FLOPs and parameters are significantly lower than those of a large kernel convolution, while achieving the effect of a large kernel convolution. Therefore, the strip convolution feature extraction scheme designed for complex landforms by EEBlock can effectively achieve excellent results while ensuring lightweight.

5.2. Discussion of Final Results

Through the ablation experiments on the model structure and the ablation experiments inside different modules, we can find that LENet is not a single module, but through the overall structure to help LENet for complex landform recognition tasks, which is also the potential advantage of LENet. It is a network with strong internal structure correlation. This strong correlation can help LENet maintain the internal integrity of the categories, which enables it to achieve the best results in the segmentation results.

6. Conclusions

This study explores the challenges faced in the semantic segmentation of complex landform features in remote sensing images, such as significant intra-class scale variations, extremely complex and dynamic information, and difficult-to-model atypical features. To address these issues, a novel semantic segmentation network—LENet—was proposed. This method enhances semantic dependence by performing long-range modeling in both horizontal and vertical directions, introduces a spatial displacement compensation mechanism to strengthen the representation of complex intra-class regions, and combines multi-scale feature fusion to improve the learning of atypical features. Experimental results on the self-built karst landform dataset and the public landslide dataset demonstrate that LENet effectively improves segmentation accuracy, exhibits strong adaptability and robustness. In the future, we will further explore the potential of LENet in other complex landform types and geological disaster scenarios, such as the segmentation task of wind erosion landforms or intelligent identification after earthquakes. We believe that this is a very valuable research method with significant application value, which can expand the depth of research on the intelligent interpretation of remote sensing images.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L. and R.Y.; methodology, Y.L. and J.R.; software, Y.L.; validation, J.R., J.W. and S.L.; formal analysis, J.R.; investigation, R.C.; resources, J.R.; data curation, D.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L.; writing—review and editing, R.Y.; visualization, W.Z. and A.Y.; supervision, J.R.; project administration, J.R.; funding acquisition, J.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Special Project of the Sichuan Bureau of Geology & Mineral Resources, grant number SCDZ-DH202508 and the Academic Degree and Postgraduate Education Reform Project of Sichuan Province, grant number YJGXM24-C073.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yuan, Q.; Shen, H.; Li, T.; Li, Z.; Li, S.; Jiang, Y.; Xu, H.; Tan, W.; Yang, Q.; Wang, J.; et al. Deep Learning in Environmental Remote Sensing: Achievements and Challenges. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 241, 111716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Georgiou, T.; Lew, M.S. A Review of Semantic Segmentation Using Deep Neural Networks. Int. J. Multimed. Inf. Retr. 2018, 7, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Lian, R.; Wu, Z.; Guo, H.; Ma, M.; Wu, S.; Du, Z.; Song, S.; Zhang, W. LOGCAN++: Adaptive Local-Global Class-Aware Network for Semantic Segmentation of Remote Sensing Imagery. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2406.16502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Yang, J.; Ou, C.; Zhang, T. Smallholder Crop Area Mapped with a Semantic Segmentation Deep Learning Method. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Lian, R.; Wu, Z.; Guan, R.; Hong, T.; Zhao, M.; Ma, M.; Nie, J.; Du, Z.; Song, S.; et al. A Novel Scene Coupling Semantic Mask Network for Remote Sensing Image Segmentation. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2025, 221, 44–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veress, M. Karst Types and Their Karstification. J. Earth Sci. 2020, 31, 621–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi Gan, Z. Karst Types in China. GeoJournal 1980, 4, 541–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yu, W.; Pun, M.O.; Shi, W. Cross-Domain Landslide Mapping from Large-Scale Remote Sensing Images Using Prototype-Guided Domain-Aware Progressive Representation Learning. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2023, 197, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhao, T.; Guo, Y.; Yin, J. RS5M and GeoRSCLIP: A Large-Scale Vision- Language Dataset and a Large Vision-Language Model for Remote Sensing. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5642123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Chen, Z.; Xiao, K.; Lei, X.; Tang, R.; He, Q.; Sun, Z.; Guo, H. SegRoadv2: A Hybrid Deformable Self-Attention and Convolutional Network for Road Extraction with Connectivity Structure. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2025, 18, 2480267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semantic Segmentation of Remote Sensing Images: Definition, Methods, Datasets and Applications. In Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 127–140. ISBN 978-3-031-54320-3.

- Maulik, U.; Chakraborty, D. Remote Sensing Image Classification: A Survey of Support-Vector-Machine-Based Advanced Techniques. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2017, 5, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattenborn, T.; Leitloff, J.; Schiefer, F.; Hinz, S. Review on Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) in Vegetation Remote Sensing. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 173, 24–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Hu, Y.; Shao, W.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, M. A Multiscale Feature Fusion Enhanced CNN with the Multiscale Channel Attention Mechanism for Efficient Landslide Detection (MS2LandsNet) Using Medium-Resolution Remote Sensing Data. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2024, 17, 2300731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhang, X.; Pun, M.-O.; Liu, M. A Multilevel Multimodal Fusion Transformer for Remote Sensing Semantic Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5403215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ye, M.; Zhu, G.; Liu, Y.; Guo, P.; Yan, J. FFCA-YOLO for Small Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5611215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Ma, G.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y. Refined Change Detection in Heterogeneous Low-Resolution Remote Sensing Images for Disaster Emergency Response. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2025, 220, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin Transformer: Hierarchical Vision Transformer Using Shifted Windows. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; IEEE: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2021; pp. 9992–10002. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, E.; Wang, W.; Yu, Z.; Anandkumar, A.; Alvarez, J.M.; Luo, P. SegFormer: Simple and Efficient Design for Semantic Segmentation with Transformers. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 12077–12090. [Google Scholar]

- BaoLong, N.; Zhang, C.; Shi, Y.; Hirakawa, T.; Yamashita, T.; Matsui, T.; Fujiyoshi, H. DeBiFormer: Vision Transformer with Deformable Agent Bi-Level Routing Attention. In Computer Vision—ACCV 2024; Cho, M., Laptev, I., Tran, D., Yao, A., Zha, H., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; Volume 15481, pp. 445–462. ISBN 978-981-96-0971-0. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, C.; Meng, X.; Fang, S. A Novel Transformer Based Semantic Segmentation Scheme for Fine-Resolution Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 19, 6506105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, D.; Yao, R.; Xue, Y. Swin Transformer Embedding UNet for Remote Sensing Image Semantic Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 4408715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2015; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, B.; Jiang, Y.; Sun, J. Unified Perceptual Parsing for Scene Understanding. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2018; Ferrari, V., Hebert, M., Sminchisescu, C., Weiss, Y., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 11209, pp. 432–448. ISBN 978-3-030-01227-4. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, M.-H.; Lu, C.-Z.; Hou, Q.; Liu, Z.-N.; Cheng, M.-M.; Hu, S.-M. SegNeXt: Rethinking Convolutional Attention Design for Semantic Segmentation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 1140–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.; Wang, J.; Peng, C.; Gao, C.; Yu, G.; Sang, N. BiSeNet: Bilateral Segmentation Network for Real-Time Semantic Segmentation. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2018; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Dana, K.; Shi, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Tyagi, A.; Agrawal, A. Context Encoding for Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Ding, T.; Lu, Y.; Pai, D.; Zhang, J.; Wang, W.; Yu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Haeffele, B.D. Token Statistics Transformer: Linear-Time Attention via Variational Rate Reduction. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.17810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An Image Is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Wang, X.; Ke, Z.; Zhang, W.; Lau, R.W.H. BiFormer: Vision Transformer With Bi-Level Routing Attention. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; IEEE/CVF: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2023; pp. 10323–10333. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Q.; Huang, H.; Chen, M.; Liu, H.; He, R. RMT: Retentive Networks Meet Vision Transformers. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; IEEE: Seattle, WA, USA, 2024; pp. 5641–5651. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Ma, X.; Su, L.; Jiang, Z.; Du, B.; Wang, X.; Lei, Z.; Feng, W.; Pun, C.-M.; Zhou, J. Mesoscopic Insights: Orchestrating Multi-Scale & Hybrid Architecture for Image Manipulation Localization. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 25 February–4 March 2025; Volume 39, pp. 11022–11030. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Fu, Y.; Gu, L.; Yan, C.; Harada, T.; Huang, G. Frequency-Aware Feature Fusion for Dense Image Prediction. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 46, 10763–10780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Yang, R.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, H.; Tan, J.; Li, S.; Yang, X.; Wang, X.; Tang, K.; Qiao, Y.; et al. P-Swin: Parallel Swin Transformer Multi-Scale Semantic Segmentation Network for Land Cover Classification. Comput. Geosci. 2023, 175, 105340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rau, J.-Y.; Jhan, J.-P.; Rau, R.-J. Semiautomatic Object-Oriented Landslide Recognition Scheme from Multisensor Optical Imagery and DEM. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2014, 52, 1336–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Liu, J.; Ni, Y.; Sun, Y.; Guo, M. MCKTNet: Multiscale Cross-Modal Knowledge Transfer Network for Semantic Segmentation of Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 4406015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q. Prompting Multi-Modal Image Segmentation with Semantic Grouping. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 20–27 February 2024; Volume 38, pp. 2094–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Chai, B.; Song, J.; Tian, T.; Zhu, P.; Ma, J.; Tian, J. Omni-Scene Infrared Vehicle Detection: An Efficient Selective Aggregation Approach and a Unified Benchmark. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2025, 223, 244–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, J.; Ma, A.; Zhang, L. FarSeg++: Foreground-Aware Relation Network for Geospatial Object Segmentation in High Spatial Resolution Remote Sensing Imagery. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 13715–13729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Liu, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, H.; Li, W.; Zou, Z.; Shi, Z. RSPrompter: Learning to Prompt for Remote Sensing Instance Segmentation Based on Visual Foundation Model. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 4701117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Qi, H.; Xiong, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, G.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y. Deformable Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, X.; Qin, Y.; Fu, R.; Gao, Y.; Liu, S.; Ye, Y.; Li, B. Multiscale Deformable Attention and Multilevel Features Aggregation for Remote Sensing Object Detection. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 19, 6510405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.-C.; Chen, S.-B.; Huang, L.-L.; Wang, G.-Z.; Tang, J.; Luo, B. Road Extraction by Multiscale Deformable Transformer from Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2023, 20, 2503905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şener, A.; Ergen, B. LandslideSegNet: An Effective Deep Learning Network for Landslide Segmentation Using Remote Sensing Imagery. Earth Sci. Inf. 2024, 17, 3963–3977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, L.P.; Dias, H.C.; Garcia, G.P.B.; Grohmann, C.H. Landslide Segmentation with Deep Learning: Evaluating Model Generalization in Rainfall-Induced Landslides in Brazil. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Huang, B.; Li, S.; Zhao, H.; Yang, X.; Zhu, J. SwinClustering: A New Paradigm for Landscape Character Assessment through Visual Segmentation. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1509113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Ye, L.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, J.; An, H. Ground Crack Recognition Based on Fully Convolutional Network with Multi-Scale Input. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 53034–53048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, M.; Dey, S.; Mukherjee, A.; Mohanty, S.; Pattnaik, P.K. Convolutional Neural Network Segmentation for Satellite Imagery Data to Identify Landforms Using U-Net Architecture. In Computational Intelligence in Pattern Recognition; Springer: Singapore, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, G.; Chen, W.; Qin, X.; Li, J.; Wang, L. Lithological Unit Classification Based on Geological Knowledge-Guided Deep Learning Framework for Optical Stereo Mapping Satellite Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5624916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-C.; Papandreou, G.; Kokkinos, I.; Murphy, K.; Yuille, A.L. DeepLab: Semantic Image Segmentation with Deep Convolutional Nets, Atrous Convolution, and Fully Connected CRFs. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2018, 40, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Chen, D.; Pan, J.; Shi, J.; Yang, J. Adapt or Perish: Adaptive Sparse Transformer with Attentive Feature Refinement for Image Restoration. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; IEEE: Seattle, WA, USA, 2024; pp. 2952–2963. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Li, B.Z.; Khabsa, M.; Fang, H.; Ma, H. Linformer: Self-Attention with Linear Complexity. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.04768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, S.; Li, H. Depth Information Assisted Collaborative Mutual Promotion Network for Single Image Dehazing. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; IEEE: Seattle, WA, USA, 2024; pp. 2846–2855. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Chen, X.; Lu, J.; Li, Y. Rethinking Multi-Scale Representations in Deep Deraining Transformer. AAAI 2024, 38, 1046–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, H.; Li, M.; Pan, J. Learning A Sparse Transformer Network for Effective Image Deraining. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; IEEE: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2023; pp. 5896–5905. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, D.; Cai, L.; Li, S.; Wang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yang, R. RAP-Net: A Region Affinity Propagation-Guided Semantic Segmentation Network for Plateau Karst Landform Remote Sensing Imagery. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Misra, I.; Schwing, A.G.; Kirillov, A.; Girdhar, R. Masked-Attention Mask Transformer for Universal Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Pang, J.; Chen, K.; Loy, C.C. K-Net: Towards Unified Image Segmentation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 10326–10338. [Google Scholar]

- Strudel, R.; Garcia, R.; Laptev, I.; Schmid, C. Segmenter: Transformer for Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; IEEE: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2021; pp. 7242–7252. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, J.; Wei, W.; Cao, H.; Guo, J.; Zhu, R.-J.; Shan, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, H. Quantized Spike-Driven Transformer. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.13492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.