Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Modern UAV-based geodetic and remote sensing methods significantly improve the monitoring of landfill deformation and associated risks.

- Climatic changes are clearly visible in long-term datasets of precipitation and temperature trends.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- Improved monitoring accuracy supports early detection of settlement, erosion, and slope instability.

- Identified climatic trends should be taken into account when planning and designing landfill reclamation and post-closure management strategies.

Abstract

Remediated landfills require long-term monitoring due to ongoing processes such as settlement, water infiltration, leachate migration, and biogas emissions, which may lead to cover degradation and environmental risks. Traditional ground-based inspections are often time-consuming, costly, and limited in terms of spatial coverage. This study presents the application of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV)-based remote sensing methods for the structural assessment of a remediated landfill. A multi-sensor approach was employed, combining geometric data (Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) and photogrammetry), hydrological modeling (surface water accumulation and runoff), multispectral imaging, and thermal data. The results showed that subsidence-induced depressions modified surface drainage, leading to water accumulation, concentrated runoff, and vegetation stress. Multispectral imaging successfully identified zones of persistent instability, while UAV thermal imaging detected a distinct leachate-related anomaly that was not visible in red–green–blue (RGB) or multispectral data. By integrating geometric, hydrological, spectral, and thermal information, this paper demonstrates practical applications of remote sensing data in detecting cover degradation on remediated landfills. Compared to traditional methods, UAV-based monitoring is a low-cost and repeatable approach that can cover large areas with high spatial and temporal resolution. The proposed approach provides an effective tool for post-closure landfill management and can be applied to other engineered earth structures.

1. Introduction

Landfills remain a fundamental component of modern waste management systems, serving as the final destination for the continuously increasing volumes of waste generated by human activities [1]. As these sites reach the end of their operational lifespan, remediation becomes essential to mitigate their environmental and social impacts, including soil and groundwater contamination, emissions of landfill gases, and the release of hazardous substances [2]. Effective remediation not only reduces these risks but also enables the transformation of former landfill areas into functional spaces such as recreational facilities, renewable energy installations, or zones of ecological restoration. Despite these efforts, the long-term structural stability of remediated landfills presents significant engineering challenges. Differential settlement of the waste body, erosion of the final cover, slope instability driven by increased pore-water pressure, and localized failures caused by wildlife activity may compromise the containment integrity of the landfill, creating environmental hazards and constraining future redevelopment potential [3,4,5]. Ensuring stability is therefore a prerequisite for any secondary use of the site, including conversion into sports facilities, photovoltaic farms, wind farms, or biogas installations. The feasibility of such redevelopment depends on the results of geotechnical investigations and sanitary assessments, which determine whether the planned structures can safely be founded on the reclaimed ground [6,7,8]. In Poland, the requirements governing landfill monitoring—both during operation and after closure—are defined in the Regulation of the Minister of the Environment of 30 April 2013 on landfills [9]. The regulation specifies the scope, frequency, and methods of monitoring activities, including the mandatory assessment of landfill surface settlement. In accordance with the stipulations set out in the legal act, the control of landfill surface subsidence is to be carried out based on established benchmarks. This means that surface settlement is to be determined based on geodetic measurements of displacements at stabilized points located on the landfill surface. These measurements are required on an annual basis throughout both the operational and post-operational phases to ensure long-term safety and compliance with regulatory standards.

Recent advances in geodetic and remote sensing techniques, especially those based on Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) use, have provided new opportunities for comprehensive, efficient, and highly detailed monitoring of landfill conditions. UAV-based surveys using photogrammetry, Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR), and multispectral and thermal sensors allows for the detection of surface deformations, erosion gullies, ponding, vegetation stress, and gas-related anomalies with much higher precision and efficiency than classical methods [6,7,8,9].

Despite the dynamic development observed in recent years, several technical gaps remain and continue to limit the reliability, comparability, and operational usefulness of UAV-based monitoring on landfills. A persistent issue is the fragmented character of multi-sensor data fusion. Many studies employ heterogeneous sensor sets and bespoke fusion pipelines, resulting in limited reproducibility. Efforts that combine multispectral, LiDAR, thermal, and gas sensors show promise but are often case-specific and lack general processing standards for data alignment, weighting, and uncertainty propagation [10,11,12]. Another recurring challenge involves georeferencing accuracy. UAV photogrammetry provides dense surface models, yet its vertical accuracy depends heavily on the distribution of ground control points, Real-Time Kinematic (RTK) positioning performance, and processing parameters. LiDAR offers better classification and penetration through vegetation but is sensitive to flight geometry and surface conditions. These limitations complicate the detection of robust volumetric changes and subsidence monitoring over time [13]. Other issues that need to be addressed concern the limited robustness of UAV-based gas emission detection and the persistent difficulties in multi-sensor point cloud registration on complex landfill surfaces [10,14]. The present study contributes to closing these gaps by providing a detailed, well-documented case study of UAV-based monitoring on a reclaimed landfill. The results offer new empirical evidence and high-quality datasets that expand the currently limited body of comparable observations. Such case-specific insights are essential for developing stronger multi-site syntheses, improving the calibration and validation of emerging methods, and supporting future research efforts, including the training of machine learning models that require diverse and reliable ground truth inputs. In this way, the study adds an incremental but important step toward addressing the technical challenges outlined above and strengthens the foundation for more comprehensive methodological advances in the field. Recent developments in UAV-based thermal, multispectral, and geometric sensing have also demonstrated strong potential for detecting subtle surface changes and environmental degradation processes in complex anthropogenic sites. These approaches have been successfully applied in heritage monitoring and environmental assessment, further confirming the value of high-resolution UAV data for identifying deformation, moisture-related damage and material deterioration [15,16].

The aim of this study is to demonstrate the capability of UAV-based geodetic and remote sensing methods for the comprehensive assessment of structural integrity in remediated landfills. Specifically, the study focuses on identifying and characterizing damage caused by settlements and surface water runoff. It was aimed to demonstrate that UAV-based remote sensing (encompassing utilizing red–green–blue (RGB), LiDAR, and multispectral spatial data) offers an efficient and cost-effective methodology for identifying and characterizing various forms of damage that can compromise the structural integrity of remediated landfill covers. Ultimately, this research aims to contribute to the development of improved long-term monitoring strategies for remediated landfills, thereby enhancing environmental protection and safeguarding public safety.

2. State of the Art

2.1. Geodetic Measurements Techniques and Their Role in Landfill Monitoring

Geodetic monitoring of landfills is conducted through the utilization of conventional methods and modern measurement techniques. Conventional methods employed in this field include tacheometry (with total station), geometric leveling, and Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) measurements. Among more advanced techniques are Structure-from-Motion (SfM) photogrammetry, laser scanning, and multispectral and thermal imaging. Such measurements are conducted either from the ground or using UAV platforms. Nevertheless, conventional landfill monitoring methods are subject to certain limitations, thus necessitating the employment of more advanced and modern techniques to enhance data resolution and operational efficiency.

2.1.1. Overview of Traditional and Modern Geodetic Measurement Methods

Conducting geodetic measurements using traditional methods such as geometric leveling, total station, or GNSS inevitably involves a degree of generalization already at the data acquisition stage. When performing these discrete, point-based surveys, the surveyor must decide at each location where to place the survey rod and how to select measurement points so that they accurately represent and characterize the surveyed terrain features (i.e., the morphology of the landfill). It is also essential that the selection of these points complies with general principles of detailed geodetic surveying and ensures an unambiguous and accurate representation of features on a map or in a 3D visualization. Choosing and positioning measurement points requires experience and practical geodetic knowledge. In contrast, modern techniques such as photogrammetry and laser scanning enable near-continuous data acquisition, no longer limited to a few dozen or hundreds of selected points. UAV-based surveys can generate multi-million-point clouds that capture the terrain in high detail, making them more efficient and less time-consuming compared to traditional measurement methods. As a result, photogrammetric imagery or laser scans eliminate generalization during data collection, thereby reducing subjectivity and the risk of error in point selection.

The use of UAV in geodetic landfill monitoring eliminates the need for manual field sketches. Typically, conducting any geodetic measurements using traditional methods, such as geometric leveling, tacheometry, or GNSS, requires the preparation of a sketch representing the surveyed terrain features. This sketch must comply with the principles of geodetic drawing and applicable regulations. It is often a demanding task that requires concentration, knowledge of cartographic symbols, and a certain degree of drawing skill. Moreover, sketching inherently involves content generalization, as it is a hand-drawn representation created in the field without a uniform scale. This generalization, through simplification and omission of features, introduces subjectivity. UAV-based imaging eliminates the need for manual sketching, as the content of the measurement is automatically recorded in the form of images or scans. The flight plan is typically prepared electronically, often automatically or semi-automatically using a controller. As a result, surveyors who find sketching challenging may view UAV as an attractive alternative to traditional surveying methods. Finally, sketching introduces the risk of errors. During sketching, spatial relationships between objects may be misrepresented, and errors may occur in the number or labeling of measurement points. Such mistakes can be critical and may require a return to the field and repetition of the measurements. The automatic, objective image acquisition provided by UAV platforms eliminates this risk.

The SfM photogrammetry can provide highly accurate terrain surface models, with centimeter-level precision, under favorable conditions, such as low vegetation cover, windless weather, a ground sampling distance (GSD) below 3 cm, and adequate daylight [13]. However, when vegetation is dense or tall, accurate terrain modeling using photogrammetry becomes unfeasible. In such cases, laser scanning, also referred to as Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR), may serve as a viable alternative. This technique enables data acquisition at any time of day, including nighttime, and allows for terrain measurement even in areas covered by tall vegetation, as laser pulses can penetrate foliage and reach the ground surface, capturing features that would otherwise be obscured. Between the two methods, the SfM photogrammetry generally offers higher accuracy, but it is subject to the aforementioned limitations.

The use of airborne laser scanning in landfill monitoring also has a certain advantage over terrestrial laser scanning, as it provides a better angle of incidence of the laser beam, resulting in a more uniform point cloud. Scanning landfills using terrestrial methods produces point clouds that are very dense near the instrument station and significantly sparser in areas located farther away.

2.1.2. Applications of Surveying and Remote Sensing Techniques in Landfill Monitoring

Photogrammetric and remote sensing imagery acquired from UAV platforms enables not only the measurement of landfill subsidence, but also the detection and assessment of (other) related adverse phenomena, such as erosion, leachate, water ponding and wildlife activity [10]. High-resolution RGB imagery acquired from UAV can effectively identify visual indicators of landfill cover damage, including the presence of cracks, erosion gullies, and animal activity. RGB cameras act as an aerial perspective, capturing detailed images that can reveal the tell-tale signs of structural compromise [5,17]. An orthophoto map, as a photogrammetric product generated from UAV imagery, enables the quantitative assessment of the aforementioned processes due to its georeferencing and uniform scale.

LiDAR data obtained from UAVs can generate accurate Digital Elevation Models (DEMs), enabling the detection of settlements and identification of areas that are prone to water ponding. However, the LiDAR-based DEM should be generated during the relatively dry season, because the laser pulse from the common airborne LiDAR sensors can only be reflected from solid material and cannot penetrate water [10]. DEMs can also be generated from point clouds obtained by SfM airborne photogrammetry, but high vegetation can significantly impair the accuracy of such measurements.

Multispectral imagery acquired from UAV can reveal valuable information about the health and stress levels of vegetation growing on the landfill cover, which may indirectly indicate underlying issues such as methane leaks or alterations in soil moisture content resulting from cover damage or animal activity. Healthy vegetation requires specific subsurface conditions. Changes in vegetation health, often not visible to the naked eye, can be detected by multispectral cameras, which capture data across different wavelengths of light. These changes can serve as proxies for underlying problems affecting the landfill’s structural integrity [18].

Thermal imagery captured by UAV can identify thermal anomalies associated with landfill gas emissions that may arise from breaches in the cover caused by settlement, erosion, or animal activity. The generation of landfill gas, together with subsurface exothermic reactions, leads to localized heat production. Owing to their high sensitivity to surface temperature variations, thermal cameras enable the identification of these anomalies, thereby allowing the precise delineation of areas where the integrity of the landfill cover is compromised or where subsurface processes may indicate emerging stability or environmental risks [19].

It is therefore evident that modern measurement techniques carried out from UAV platforms represent a valuable solution that offers many advantages over traditional methods. The rapid technological progress, the emergence of new surveying instruments on the market, and the evolving geographic environment, which also affects the accuracy of geodetic measurements, are all factors that make the study and testing of modern methods and instruments inherently innovative and a pursuit well worth the effort.

Accurate measurement of surface displacements, settlements, and deformations provides key data to identify zones of increased risk, such as areas affected by differential settlements, cracks in the final cover, or slope instabilities triggered by excess pore water pressures. Geodetic methods offer the advantage of continuous, non-invasive, and spatially extensive monitoring, which is essential for capturing both gradual changes (e.g., settlement due to long-term infiltration) and sudden events (e.g., deformation after extreme storms). Therefore, integrating hydrological assessments with geodetic monitoring constitutes an effective approach to ensure the structural stability and environmental safety of landfills under climate change. The integration of geodetic measurements with geotechnical modeling enhances the predictive capacity of monitoring programs, supporting timely remediation and adaptation strategies.

2.2. Landfill Risks in the Context of Climate Change

Landfills remain one of the most sensitive geotechnical systems to climatic drivers, especially precipitation, surface runoff, and fluctuations in groundwater level. Climate change, characterized by more frequent extreme rainfall, prolonged wet seasons, and increasing variability in water balance, amplifies the risk of structural and functional failures in landfill cover systems and slopes. Excess water infiltration can accelerate waste settlement, generate higher volumes of leachate, and weaken the shear resistance of cover layers and liner interfaces. These processes lead to erosion of the protective soil cover, cracking of geomembranes, instability of side slopes, and potential release of contaminants into groundwater and surface water. Table 1 presents selected examples of how climate change affects engineering structures, based on recent studies.

Table 1.

Examples of risks of landfill damage under climate change.

Climate change represents a significant driver of geotechnical risk for landfills, primarily through altered hydrological regimes [36]. Water in its multiple aspects (precipitation, surface runoff, infiltration, groundwater fluctuations) constitutes a significant factor affecting landfill integrity. Intensification of rainfall and storm events has been shown to accelerate cover erosion, enhance infiltration and leachate generation, and promote differential settlements that compromise the functionality of capping systems [37]. Extreme flood events may further result in the washout of cover soils, the detachment and transport of fine particles during surface runoff, and, in severe cases, the release of contaminants and waste material into adjacent environments [38].

In addition to hydrological stressors, temperature extremes and wetting–drying cycles exacerbate the development of desiccation cracks, thereby increasing the susceptibility of covers to infiltration [39,40]. Rising ambient temperatures may also alter landfill gas dynamics and reduce the performance of sealing systems [41]. The combined effect of these processes is a measurable increase in both the frequency and severity of structural damage, ranging from surface erosion [42] to large-scale instability [43,44].

To mitigate these risks, adaptive engineering strategies are required [7]. These include the design of drainage systems, the application of reinforced and geosynthetic sealing layers, and the implementation of continuous geotechnical and geodetic monitoring. Furthermore, nature-based solutions, such as the use of vegetation with high erosion control capacity, provide an additional protective function [45].

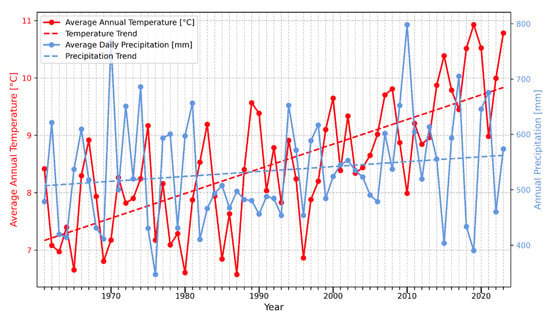

To confirm the general trends in climate variability, an analysis was conducted of changes in total annual precipitation (Figure 1), precipitation intensity (Figure 2), and mean annual temperature (Figure 1 and Figure 2) for the period 1961–2023. Both graphs were prepared using open data provided by the Institute of Meteorology and Water Management—National Research Institute (IMGW-PIB) [46].

Figure 1.

Annual precipitation per year for Warsaw in 1961–2023.

Figure 2.

Average daily precipitation intensity per year for Warsaw in 1961–2023.

Both mean annual temperature and annual precipitation totals exhibit an upward trend, as confirmed by least squares regression lines. The results indicate that the mean temperature is increasing at a rate of approximately 0.5 °C per decade, while annual precipitation totals are rising by about 8.3 mm per decade. Over the 62-year period, the mean annual temperature has increased by nearly 3 °C. A notable inverse relationship can be observed between temperature and precipitation in several years: periods with precipitation peaks tend to coincide with relatively low mean temperatures (e.g., 1962, 1970, 1978, 2010), while the opposite situation—high temperature with low precipitation—occurred in 2019 and 2023. Precipitation events have become more concentrated and intense over time, as shown in the precipitation intensity graph (Figure 2), which presents mean annual temperature together with precipitation intensity, expressed as the annual precipitation total divided by the number of days with precipitation. The blue trend line representing precipitation intensity shows a clear upward trend, confirming an increase in the average intensity of rainfall events throughout the analyzed period.

The observed climatic trends may have important implications for the stability and hydrological behavior of reclaimed landfills. Higher temperatures can intensify evapotranspiration and accelerate the drying of topsoil layers, potentially affecting vegetation cover used for surface stabilization. On the other hand, an increase in total annual precipitation, combined with more frequent extreme rainfall events, can enhance leachate generation and lead to changes in pore water pressures within the landfill body. These factors should be considered in long-term monitoring programs and in the design of drainage and sealing systems for reclaimed waste disposal sites.

3. Materials and Methods

This section presents the characteristics of the study area (Section 3.1) and the measurement equipment used (Section 3.2). It also describes the proposed method for detection damages caused by rainwater based on measurements made by the UAVs by the photogrammetric method, LiDAR method, multispectral method and thermal method (Section 3.2).

3.1. Study Area

The Słabomierz-Krzyżówka landfill is located in Poland, near Warsaw City. The landfill was built in 1970 on the site of an old sand and gravel quarry. From 1970 to 1992, unsorted municipal and industrial waste was deposited at the landfill. From 2016, the landfill site only collected construction waste such as concrete waste and concrete rubble from demolition and renovation works, mixed waste from concrete, brick rubble, waste ceramic materials, compost that did not meet the requirements, as well as soil, earth and stones. In 2022, the landfill was closed and reclaimed. A degassing and drainage network was built, as well as a vertical barrier to prevent pollutants from escaping into adjacent areas. The final reclamation of the landfill was determined to be for a photovoltaic farm. Currently, the landfill and its technical facilities cover an area of approximately 14 hectares, with the landfill itself covering an area of approximately 9 hectares. The current height of the landfill is approximately 27 m, measured from its base to its top. There are 15 control points (benchmarks) on the site to monitor the settlement of the landfill body. The current appearance of the landfill is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

View of the Słabomierz-Krzyżówka landfill site from (a) the south-east and (b) the north-east.

3.2. Methodology

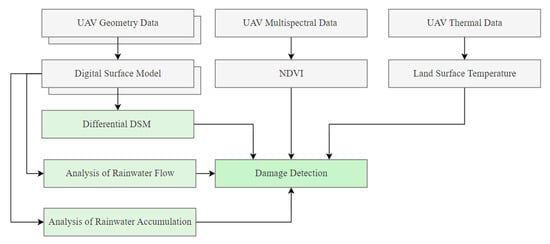

A series of measurements was taken at the Słabomierz-Krzyżówka landfill site using a LiDAR sensor, an RGB camera, a multispectral camera, and a thermal camera. These measurements made it possible to inventory the facility and identify damage caused mainly by the settling of the landfill and the effects of rain, which washes away the top layer of the landfill’s mineral cover. Four UAV sets were used for the research: a Phantom 4 RTK (DJI, Shenzhen, China) equipped with an RGB camera, a DJI Matrice M600 (DJI, Shenzhen, China) with a LiDAR sensor, a DJI Mavic 3 thermal (DJI, Shenzhen, China) with a thermal camera, and a DJI Matrice M600 with a Parrot Sequoia (Parrot, Paris, France) multispectral camera. These instruments enabled the collection of data on the landfill’s geometry and a visual assessment of the technical condition of the infrastructure elements located on its premises. An analysis of the landfill geometry was performed to determine the paths of rainwater runoff and its accumulation in the upper part of the landfill. As part of the work, an orthophoto map of the landfill and a Digital Surface Model (DSM) were created. Moreover, thermal and multispectral images of areas of interest at the landfill were captured in locations where potential damage was observed. The multispectral images allowed the landfill site to be mapped in four spectral channels: red (R), green (G), blue (B), and near-infrared (NIR). Next, based on the photos, the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) was calculated, which allowed for an inventory of the vegetation cover at the landfill site. Thermal images, on the other hand, allowed for the detection of thermal anomalies that may indicate potential damage caused by water seepage or surface water runoff down slopes. The integration of all the data obtained made it possible to reveal defects and damage that would have been impossible to detect using conventional methods, or changes that would have been detected too late, which could have led to more serious damage later on. The research methodology flowchart is presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Flowchart of research methodology.

Geometric data was acquired using: a DJI Phantom 4 RTK equipped with an RGB camera and a DJI Matrice M600 with a LiAir S50 (GreenValley International, Beijing, China) LiDAR sensor. All flights were conducted at a constant altitude of 50 m above ground level to ensure consistent spatial resolution. In the photogrammetric missions performed with the RGB sensor, a forward overlap of 80% and a side overlap of 70% were applied to guarantee sufficient image redundancy for accurate 3D surface reconstruction. The internal camera calibration parameters were estimated automatically during the Pix4D photogrammetric processing using a self-calibration workflow based on bundle adjustment. LiDAR data were collected using the same platform and altitude to maintain geometric consistency across datasets. The collected data were processed in Pix4D mapper version 4.7.5 software (Pix4D, Lausanne, Switzerland) to generate a high-resolution DSM. Subsequently, Differential DSM (dDSM) were derived by subtracting DSM obtained at annual periods. This procedure enabled the detection of subtle elevation changes and terrain deformation. The geometric information was used to analyze potential rainwater flow paths and to identify areas of rainwater accumulation. Additionally, the geometric features served as a crucial input for the damage detection stage.

To further investigate the hydrological implications of surface deformation, the DSM of the landfill crown was used to perform terrain-based water modeling in QGIS using the SAGA Processing tools (version 9.5.1). First, an analysis of surface water accumulation areas was conducted to identify depressions where rainfall may be retained. The “Fill Sinks (Wang & Liu)” algorithm [47] was applied to remove artificial sinks while preserving natural depressions. This analysis used a 2023 DSM from the SfM method with a resolution of 10 cm. A minimum slope of 0.01 degrees was used in the parameters. The result was a DSM with filled local depressions. Then, using the raster calculator tool, the differences in height between the two DSMs were calculated. This enabled the calculation of the depth of local depressions and their presentation of location. These depressions were interpreted as potential water retention zones, particularly in areas characterized by low slope gradients. Such locations are prone to prolonged moisture accumulation, which can negatively impact the stability of the landfill cover.

Second, surface water runoff pathways were extracted using the hydrological tools available in SAGA GIS. After hydrological conditioning with the Fill Sinks algorithm [47], the “Channel Network and Drainage Basins” tool was applied to delineate drainage structures on the landfill crown. A flow-accumulation threshold value of 5 cells was used to initiate channel formation, ensuring that only persistent and hydrologically meaningful flow paths were extracted while avoiding noise-driven artifacts typical for high-resolution DSMs. The resulting channel network was then automatically ordered by stream hierarchy, allowing identification of primary and secondary runoff paths and their connectivity. These drainage lines were subsequently compared with previously detected depressions, revealing several intersections where accumulated flow converged into subsidence-induced retention zones. This workflow, based entirely on the DSM, enabled the delineation of preferential drainage patterns on the landfill crown and demonstrated that even subtle micro-topographic variations can significantly influence runoff routing and localized water pooling. The derived drainage network provided a spatial basis for interpreting moisture-related anomalies observed in the thermal and multispectral analyses.

Multispectral data were captured using a DJI Matrice M600 equipped with a Parrot Sequoia multispectral camera. All flights were performed at an altitude of 50 m above ground level, with 80% forward overlap and 70% side overlap to ensure radiometric consistency and sufficient surface coverage. These parameters were selected to align with the photogrammetric geometric data and facilitate accurate spatial co-registration across datasets. The multispectral imagery was processed in Pix4Dmapper version 4.7.5 to generate reflectance maps in the red (RED) and near-infrared (NIR) spectral bands. Based on these maps, the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) was calculated to assess vegetation health. NDVI is defined as:

where NIR represents the near-infrared band reflectance and RED represents the red band reflectance. NDVI values range from −1 to 1, with higher values indicating dense and healthy vegetation, and lower values corresponding to sparse, stressed, or absent vegetation [48]. NDVI was used to identify vegetation stress conditions that may be related to soil moisture variations, surface deformation, or structural damage. The spectral information was later integrated with geometric (DSM, dDSM) and thermal (LST) indicators to improve the reliability of the damage detection analysis.

The multispectral data were not validated against ground reflectance measurements. Instead, radiometric consistency was ensured using the manufacturer’s calibration workflow (Parrot Sequoia), including the use of the standard reflectance calibration panel and the incident light sensor. Since the purpose of the multispectral analysis in this study was to identify relative vegetation stress patterns rather than retrieve absolute reflectance values, full radiometric validation was not required. The interpretation of NDVI anomalies is therefore limited to relative spatial patterns, as noted in the Discussion.

Thermal data was acquired using a DJI Mavic 3 Thermal UAV equipped with an integrated thermal infrared camera. The thermal flights were performed at an altitude of 50 m, consistent with the geometric survey to facilitate data integration. Due to the lower spatial resolution of thermal sensors, a higher forward overlap of 90% and side overlap of 80% were applied to minimize geometric distortions and radiometric noise. All flights were conducted under stable atmospheric conditions to reduce temperature fluctuation effects. The thermal images were processed in Pix4D mapper version 4.7.5 software to generate Land Surface Temperature (LST) map. This map allowed the identification of thermal anomalies, potentially associated with moisture infiltration, material degradation, or heat retention caused by structural damage. The thermal dataset was subsequently integrated with geometric and spectral data to support the damage detection and interpretation process.

Thermal data acquired with the DJI Mavic 3T were processed using the sensor’s internal radiometric calibration workflow. The camera applies factory calibration, emissivity correction (default ε = 0.95), and onboard temperature compensation, which convert raw sensor counts into radiometric temperature values. No atmospheric correction or ground-based temperature validation was performed. Since the objective of the thermal analysis was to detect relative temperature anomalies rather than to retrieve absolute land surface temperatures (LST), the internal calibration provided by the sensor was considered sufficient. The resulting thermal interpretation is therefore qualitative and focuses on spatial contrasts rather than absolute temperature values.

4. Results

Damage detection at the landfill site involved two aspects: predicting potential damage locations by analyzing the geometry of the landfill site (Section 4.1) and direct detection of damage at the landfill site using orthophoto maps, land surface temperature (Section 4.2), NDVI (Section 4.3), and geometry changes (Section 4.1). We can distinguish two main types of damage at the landfill site: damage caused by subsidence of the structure and damage caused by water.

4.1. UAV Geometric Results

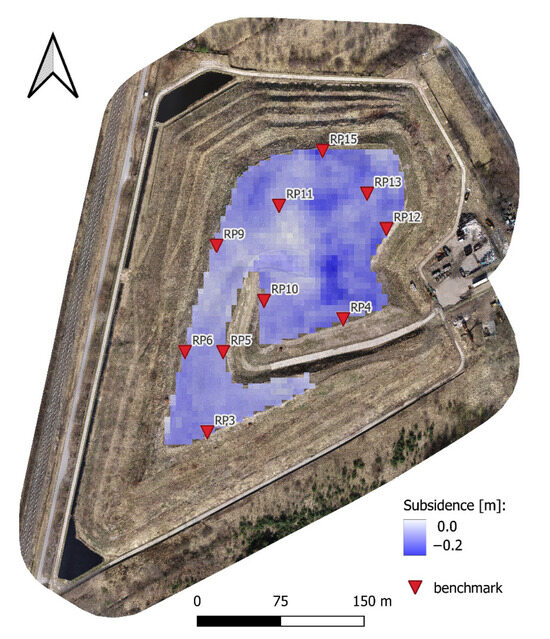

The processing of UAV LiDAR and UAV photogrammetric data resulted in the generation of high-resolution DSMs for two datasets acquired one year apart. Although DSMs were generated using both methods, the photogrammetric DSMs were utilized for deformation analysis in this study, as they provided higher spatial resolution and achieved accuracy comparable to that of the LiDAR dataset. The photogrammetric method works very well in areas with little to no vegetation. This type of area can be found on the top surface (crown) of the landfill. As demonstrated in our previous work [13], UAV LiDAR delivers a vertical accuracy of approximately 4–5 cm, while the photogrammetric workflow used here achieved RMSE_Z values of 1.6–1.7 cm. The mean vertical deformation error using the photogrammetric workflow was ±2.3 cm [17]. Both UAV LiDAR and photogrammetric DSMs meet the accuracy requirements for the deformation and surface process analyses performed in this study, and therefore, both datasets are suitable for these applications. Since both LiDAR- and SfM-derived DSMs showed nearly identical surface representations on the landfill crown, the photogrammetric models were selected for the dDSM computation. The two annual DSMs were spatially aligned using the same ground control network and resampled to a common resolution, enabling direct comparison. Visual inspection revealed local variations in surface elevation across the landfill, particularly in zones with heterogeneous waste composition. The geometric analysis focused on the top surface (crown), as this area is the most susceptible to structural changes and vertical deformation. A Differential DSM (dDSM) was then generated by subtracting the DSM from the earlier survey from the DSM of the later survey. The resolution was resampled to 5 m using bilinear interpolation in QGIS (GDAL-based resampling) to reduce noise and highlight the main settlement trends (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Results of the analysis of annual subsidence of the top of the landfill.

Figure 5 shows the spatial distribution of benchmarks on the landfill crown used in the accuracy assessment. Annual displacements derived from UAV photogrammetry were validated against trigonometric leveling measurements obtained at the same benchmark locations, with the comparative results summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of annual subsidence derived from UAV SfM photogrammetry and leveling measurements used for DSM co-registration.

The co-registration accuracy of the DSMs was evaluated using the difference be-tween the photogrammetric heights and the leveling measurements at the benchmark points. The error was quantified using the standard RMSE formula:

where Δh represents the vertical difference between the DSM from UAV SfM Photogrammetry and leveling measurements at stable benchmarks located on the landfill crown. The analysis produced RMSE = 2.11 cm and mean error of 1.45 cm, demonstrating that the applied photogrammetric workflow provides sufficient accuracy to detect the subsidence magnitudes observed in this study.

The dDSM enabled the detection of negative elevation changes within the crown area. The results revealed non-uniform settlement patterns, with several zones exhibiting noticeable surface lowering. In Figure 5, surface subsidence is marked in blue. The maximum subsidence values are 20 cm. Areas without changes are marked in white. These negative elevation values were interpreted as landfill settlement and compaction, driven by the internal degradation of waste material and consolidation processes. Importantly, the spatial distribution of subsidence indicates the formation of localized depressions on the landfill crown. These depressions represent potential rainwater accumulation zones, which may alter surface runoff patterns and increase the risk of water infiltration or damage to the landfill cover. Excessive standing water adds additional load to the landfill surface and increases moisture penetration, which can intensify waste compaction and lead to further deformation of the landfill crown. Therefore, the geometric results not only quantified the deformation of the landfill crown but also provided critical information about areas prone to water retention, serving as a foundation for subsequent thermal and multispectral analyses.

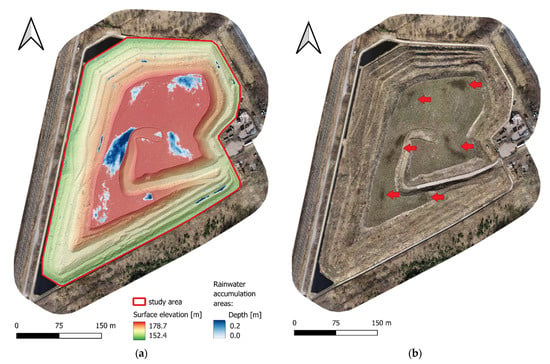

The geometric data were further used to analyze potential surface water accumulation areas and surface water runoff patterns on the landfill crown. The zones characterized by low slopes and concave surface morphology were identified as potential areas of rainwater accumulation. These depressions, derived from the DSM, represent locations where precipitation water may collect due to insufficient surface drainage. Such areas are particularly prone to moisture retention, which may weaken the landfill cover and increase the risk of local structural instability. Subsequently, a surface water runoff analysis was performed to simulate the direction and intensity of potential flow paths. Using the DSM-based flow accumulation model, several preferential drainage directions were identified. These flow paths were consistent with the general terrain slope and the structural configuration of the landfill surface. In some cases, runoff pathways converged toward previously identified accumulation zones, suggesting an increased likelihood of localized water pooling. The geometric results therefore provided a comprehensive spatial basis for understanding the hydrological behavior of the landfill crown and served as a foundation for the subsequent thermal and multispectral analyses. The results of the analysis of surface water accumulation areas are presented in Figure 6, and the results of the analysis of surface water runoff are presented in Figure 7.

Figure 6.

Results of the analysis of surface water accumulation areas (a) and orthophoto map captured after the heavy rainfall (b) showing the locations where water accumulated on the landfill crown.

Figure 7.

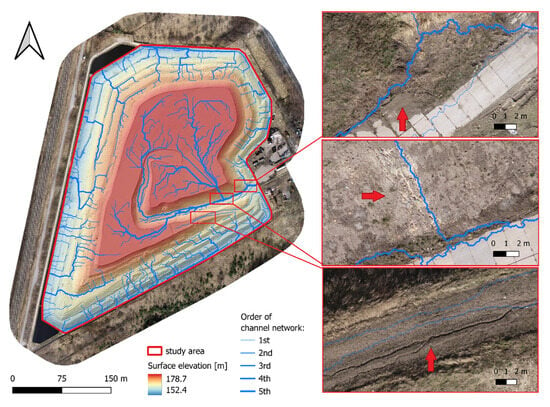

Result of the surface water runoff analysis.

The analysis of surface water accumulation areas (Figure 6) revealed that, despite the overall sloped geometry of the landfill surface, several local depressions were present within the study area. The modeled water depth reached values of up to 0.2 m, indicating that these depressions may retain a significant amount of water after rainfall events. The largest accumulation zones were observed both on the central landfill crown and along the northern and western benches, where the surface gradient was locally reduced. This demonstrates that even minor terrain irregularities can impede surface runoff and promote ponding. Importantly, several of the identified depressions spatially correspond with the areas of negative elevation change previously detected in the dDSM-based subsidence analysis. This suggests that landfill subsidence contributes directly to the formation of water retention zones, particularly in the central crown region, where internal waste consolidation is most active. Additional accumulation areas detected along the landfill perimeter may be related to differential settlement or insufficient drainage near the slopes. The concentration of standing water in these zones increases the likelihood of prolonged moisture retention and elevated pore-water pressure, which can weaken the landfill cover and potentially trigger further deformation. The spatial distribution of accumulation zones indicates that the landfill crown does not drain uniformly, and localized depressions may act as initiation points for surface instability or progressive settlement. These findings provided a hydrological basis for the subsequent surface water runoff analysis and were later integrated with thermal and multispectral indicators of moisture and degradation to strengthen the damage detection process.

The surface water runoff analysis (Figure 7) revealed a well-developed and hierarchically organized drainage network across the landfill surface. Numerous first-order channels originated on the landfill crown, confirming that the highest part of the landfill functions as the primary source area for surface runoff. As water flowed downslope, these initial channels progressively merged into higher-order streams, forming a dendritic drainage pattern.

To classify the extracted runoff pathways into hydrologically meaningful groups, the channel network was ordered using the Strahler stream-ordering system, as implemented in the SAGA GIS “Channel Network and Drainage Basins” tool. In this approach, first-order channels represent the initial flow paths generated above the applied flow-accumulation threshold, while higher-order channels emerge when two channels of the same order merge. Consequently, 4th- and 5th-order channels correspond to the main drainage routes, concentrating the majority of surface runoff on the landfill crown. This hierarchical classification enabled the distinction between minor, locally confined flow lines and the dominant runoff pathways that govern the redistribution of surface water across the landfill. The plausibility of the extracted high-order pathways was evaluated using both field observations and selected examples visible on the high-resolution RGB orthophoto map (Figure 7). Although vegetation cover obscured many micro-topographic features, several primary runoff paths coincided with visible indicators on the orthophoto—such as zones of reduced vegetation, darker moist soil patches, and subtle linear surface features formed by shallow runoff. These orthophoto interpretations aligned with in situ observations of wet-soil areas and small erosional grooves recorded during site visits, supporting the validity of the delineated drainage network.

The main runoff pathways (4th- and 5th-order channels) were predominantly directed toward the eastern and south-eastern slopes, where the highest flow accumulation values were recorded. This indicates that these parts of the landfill are subjected to the greatest runoff intensity and may be more vulnerable to surface erosion or cover layer degradation. In contrast, the western side exhibited a lower density of flow paths, suggesting more uniform slopes or more efficient drainage in that area. Several of the major flow paths intersected or terminated within previously identified surface water accumulation zones (Figure 6), particularly on the central crown and along the south-eastern bench. This hydrological connectivity implies that runoff from higher areas may feed into existing depressions, promoting prolonged water retention and potentially accelerating subsidence-related deformation. Overall, the runoff modeling demonstrated that water is not evenly distributed across the landfill surface. Instead, specific sectors act as preferential flow corridors (east and southeast), while others serve as potential retention zones, intensifying the risk of moisture accumulation and structural instability. These results provide essential spatial input for the integration with thermal and multispectral indicators in the damage detection stage.

4.2. UAV Multispectral Results

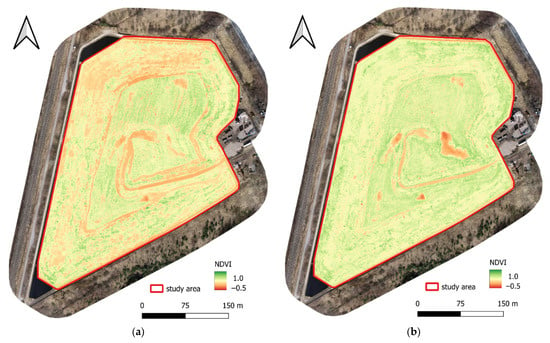

The NDVI maps derived from UAV multispectral imagery provided valuable insight into the spatial variability of vegetation health across the landfill surface. Since the technical reclamation of the landfill was completed in autumn 2022, the NDVI map from March 2023 (Figure 8a) represents the first post-reclamation vegetation season, whereas the map from March 2024 (Figure 8b) illustrates vegetation conditions after one year of surface stabilization.

Figure 8.

NDVI maps of the landfill surface derived from UAV multispectral imagery showing vegetation condition in (a) March 2023 and (b) March 2024.

Overall, the 2024 NDVI map shows a higher proportion of medium to high NDVI values compared to 2023, indicating an overall improvement in vegetation cover and a successful establishment of the reclamation layer. This suggests that the landfill surface is generally stabilizing and supporting vegetation growth under normal conditions. However, several localized zones with persistently low NDVI values were identified in both years. The stability of these low-NDVI patches indicates that vegetation stress in these areas is not temporary or seasonal, but rather linked to underlying environmental or structural issues. These zones may correspond to areas with shallow soil cover, poor substrate quality, subsurface compaction, or limited water availability. In some cases, they coincide with previously detected subsidence depressions (dDSM) or surface water accumulation areas (Figure 6), suggesting that deformation and moisture retention may prevent proper vegetation development.

To further formalize the assessment of vegetation condition and to enable a reproducible comparison between the two survey years, the NDVI values were classified into three threshold-based categories representing stressed (NDVI < 0.25), moderate (0.25–0.45) and healthy vegetation (NDVI > 0.45). These thresholds were applied to quantify how vegetation cover changed over time and to distinguish broad trends from localized anomalies. The resulting classification is summarized in Table 3. The quantitative analysis confirms a substantial shift in vegetation condition between 2023 and 2024, with a marked reduction in stressed vegetation and a corresponding increase in the moderate and healthy vegetation classes. This numerical assessment reinforces the interpretation that vegetation cover improved significantly over the study period, while also highlighting the persistence of localized low-NDVI zones associated with structural or hydrological constraints.

Table 3.

Proportion of NDVI classes on the landfill surface in 2023 and 2024.

Furthermore, new areas with reduced NDVI were observed in 2024, primarily along selected slope segments. These locations may be associated with surface runoff pathways (Figure 7), where concentrated flow could lead to erosion of the reclamation layer or damage to the cover system. Vegetation degradation (Figure 9) in these areas may therefore serve as an early bio-indicator of potential cover instability or structural damage.

Figure 9.

Examples of landfill cover damage detected using multispectral analysis: (a–c) surface water runoff erosion, (d–f) potential biogas leakage, and (g–i) water infiltration through the landfill slope.

Figure 9 presents three examples of landfill cover damage detected through the integration of high-resolution orthophotos and NDVI maps from March 2023 and March 2024. Each row corresponds to a different degradation process affecting the landfill surface, while the columns show the visual appearance (orthophoto) and the corresponding vegetation condition (NDVI) in two consecutive years. In the first row (Figure 9a–c), areas affected by surface water runoff erosion are shown. The orthophoto reveals linear rills and subtle surface disturbances, consistent with concentrated flow paths identified in the hydrological runoff analysis. These features correspond to elongated low-NDVI zones in both 2023 and 2024, indicating persistent vegetation stress. The stability of these features over time suggests that runoff-driven erosion may gradually remove the reclamation layer and inhibit vegetation establishment. The second row (Figure 9d–f) illustrates a location influenced by potential biogas leakage. The orthophoto shows patches of bare or sparsely vegetated soil, while both NDVI maps display circular or irregular zones of very low NDVI, which remain visible in both years. Since biogas emissions can lead to oxygen depletion and root damage, vegetation cannot develop in these areas despite overall improvement in surrounding zones. The persistence of these anomalies suggests ongoing gas migration through the cover layer and highlights a potential risk to the integrity of the landfill sealing system. The third row (Figure 9g–i) shows an example of water infiltration through the landfill slope. The orthophoto reveals discoloration and moisture traces on the slope surface, while the NDVI maps show consistent low NDVI values along the slope toe. These areas correspond to previously identified surface water accumulation zones (Figure 6) and may also be related to subsidence-induced depressions. Prolonged waterlogging likely limits oxygen availability in the root zone, leading to vegetation dieback and progressive cover deterioration. In addition, surface runoff may cause erosion of the slope, further exposing the mineral cover layer. Overall, the comparison between 2023 and 2024 demonstrates that, while general vegetation conditions improved during the second year after reclamation, specific problem areas continued to exhibit low NDVI values, indicating chronic structural issues such as erosion, gas leakage or infiltration-induced weakening of the cover layer. These findings confirm that NDVI is an effective bio-indicator for monitoring landfill surface integrity and identifying high-risk zones that require further inspection or remediation.

The results confirm that NDVI is an effective tool for monitoring the long-term performance of landfill reclamation. Persistent or emerging low-NDVI zones highlight areas where additional inspection or maintenance may be required. These spectral observations provided crucial input for the subsequent integrated damage detection analysis by combining vegetation stress signals with geometric and thermal indicators.

4.3. UAV Thermal Results

The thermal data provided additional insight into subsurface and surface processes affecting the landfill cover. While geometric and multispectral analyses primarily identified deformation and vegetation stress, thermal imaging made it possible to detect temperature anomalies associated with leachate migration, intensified biological activity, and functional degradation of the cover layer. Temperature anomalies were identified by analyzing positive deviations from the background Land Surface Temperature (LST) pattern. Leachate migrating through the cover typically appears warmer due to the elevated temperature of percolating liquids and the heat generated by microbial processes within the waste mass. Similarly, zones of increased biological activity or reduced cover insulation may also exhibit higher surface temperatures.

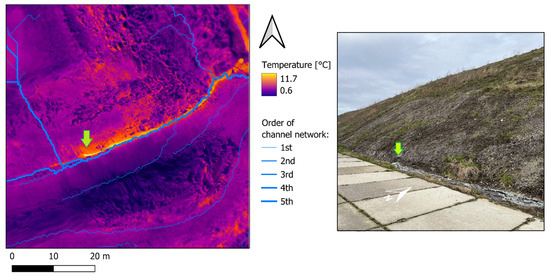

The LST map generated from UAV thermal imagery therefore enabled the detection of localized hotspots that deviated from the expected thermal behavior of the reclaimed surface. Most of the landfill surface showed uniform temperatures consistent with stable vegetation and proper functioning of the cover layer. However, one distinct linear thermal anomaly was significantly warmer than its surroundings, indicating a localized disturbance in the thermal balance of the cover. Field inspection confirmed the presence of moist and softened ground in this location, supporting the interpretation that the anomaly was caused by leachate seepage. This example of surface cover damage is presented in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Land Surface Temperature (LST) map overlaid with the surface water runoff network, showing a thermal anomaly on the landfill slope (left) and a field photograph confirming the anomaly location (right).

Figure 10 presents a detailed view of the Land Surface Temperature (LST) distribution over a selected section of the landfill cover, overlaid with the drainage network derived from the surface water runoff analysis. The thermal map reveals a clear linear zone of elevated temperature (yellow–orange), which is distinctly warmer than the surrounding surface. This thermal anomaly follows the slope break/bench transition zone, and its most pronounced section is indicated by the green arrow. Field observations confirmed that this anomaly corresponds to leachate seeping through the landfill cover. Leachate typically exhibits higher temperatures than the surrounding soil, especially during early spring when subsurface decomposition processes are active. As the leachate migrates toward the surface, it increases local LST, producing a distinct thermal signature.

5. Discussion

The results of this study confirm that geometric deformation is a primary driver of landfill surface instability and initiates a cascade of secondary processes. Differential set-subsidence of the landfill crown led to the formation of local depressions, which functioned as surface water accumulation zones. This finding is consistent with previous research indicating that landfill subsidence is a common and long-lasting phenomenon caused by waste compaction, biodegradation, and heterogeneous material composition [7,10,17,18]. DSM-based modeling revealed that these depressions not only retained water but also redirected run-off into preferential flow paths, increasing the concentration of surface water and the risk of erosion. This agrees with the findings of Li et al. [28] and Hassan et al. [10], who emphasized that rainfall-driven runoff and limited drainage capacity are critical contributors to cover degradation. Results of this study clearly demonstrate that even small-scale deformation, when combined with rainfall, can lead to localized weakening of the cover, enhanced pore-water pressures, and progressive instability—processes also highlighted in studies on landfill slopes and geotechnical failures under intensified hydrological stress [37,43].

Multispectral data further enhanced the understanding of surface conditions by revealing patterns in vegetation health as a proxy for underlying structural issues. NDVI analysis showed an overall increase in vegetation cover between 2023 and 2024, confirming the general effectiveness of the reclamation process. However, several zones consistently maintained low NDVI values, despite favorable climatic conditions and overall vegetation improvement. This persistence indicates chronic stress rather than seasonal variability. These areas frequently coincided with subsidence depressions and water accumulation zones, confirming that vegetation decline reflects unfavorable subsurface conditions such as excessive moisture, compaction, or lack of rooting depth. This is consistent with previous studies that identified vegetation as an effective bio-indicator of landfill cover performance [18,19,48,49]. Similar relationships between vegetation stress and gas leakage or cover failure were reported by Bruch et al. [18] and Wang et al. [48]. In this study, NDVI also detected new zones of vegetation degradation along slope segments in 2024, likely caused by runoff-induced erosion. These results align with findings that surface runoff can gradually remove the reclamation layer and expose the mineral cover beneath [20,28,42]. Therefore, NDVI is not only useful for mapping vegetation health but also for identifying processes that compromise landfill surface integrity.

Thermal data provided additional insights into subsurface processes that could not be detected by geometric or multispectral analyses alone. While most of the landfill surface displayed uniform LST values consistent with stable vegetation and proper cover function, one distinct linear thermal anomaly was identified. Field verification confirmed that this anomaly corresponded to leachate seeping through the cover. Leachate often has higher temperature than surrounding soil due to internal heat generated by biological activity and exothermic reactions within the waste mass [4,19]. Similar thermal anomalies linked to gas or leachate migration were also reported by Tanda et al. [19], Hassan et al. [10], and Sedano-Cibrián et al. [50], who demonstrated that UAV-based thermal monitoring can effectively detect internal landfill processes and support early-stage damage assessment. The spatial alignment of the thermal anomaly confirms leachate seeping through the cover anomaly with higher-order runoff paths suggests that erosion or surface flow may have weakened the cover, creating pathways for leachate migration. Field inspection confirmed the presence of moist, softened ground in this location, supporting the interpretation that the anomaly is associated with leachate seepage. This observation supports the findings of Koda et al. [7] and Sinnathamby et al. [20], who emphasized that hydrological processes, cover degradation, and internal fluid movement are strongly interconnected. The combination of dDSM, hydrological modeling, NDVI, and LST data in our study confirmed that landfill degradation is rarely the result of a single process, but instead arises from interactions between deformation, water dynamics, vegetation stress, and subsurface fluid migration. This holistic view is consistent with recent literature advocating multi-sensor UAV-based monitoring for landfill assessment [10,18,23].

It should be noted that neither multispectral nor thermal datasets underwent full ground-based radiometric validation. While this does not affect the identification of relative anomalies (vegetation stress zones or thermal hotspots), the results should be interpreted in terms of spatial patterns rather than absolute values. The thermal and NDVI analyses therefore provide qualitative, pattern-based insights. Future work may include in situ temperature logging and surface or leaf reflectance measurements to strengthen the quantitative interpretation and reduce radiometric uncertainty. Although no quantitative ground measurements (e.g., soil moisture, gas flux) were collected, several NDVI and LST anomalies were qualitatively verified through comparison with RGB orthophotos and visual inspection during field visits. The agreement between UAV-derived anomalies and observed surface features confirms their diagnostic value, although the interpretation remains pattern-based rather than fully quantitative.

The climatic analysis in Section 2.2 shows that rainfall events have become more in-tense over time, with more precipitation falling during shorter periods. These changing conditions help explain several of the hydrological features observed on the landfill sur-face. Local subsidence areas create small depressions that fill quickly during intense rain-fall, which is consistent with the modeled water depths of up to 0.2 m (Figure 6). Such water accumulation increases the load on the cover system and may accelerate settlement. The identified runoff pathways on the eastern and south-eastern slopes also match the expected behavior under heavy rainfall, where concentrated flow can lead to erosion or weakening of the reclamation layer. The presence of persistent and newly formed low-NDVI zones supports this interpretation, indicating that vegetation stress is likely related to increased moisture and surface runoff in these locations Taken together, the climatic trends and UAV observations suggest that increasingly intense rainfall plays a key role in shaping the detected deformation, water accumulation, and vegetation changes on the landfill.

Overall, the integration of geometric, hydrological, spectral and thermal data proved highly effective for identifying early-stage damage and understanding its root causes. Unlike traditional monitoring methods based on discrete survey points or visual inspection, UAV-based remote sensing enabled continuous, high-resolution, and multi-dimensional analysis of the landfill surface. This approach allowed us to detect high-risk areas that may not yet be visible but exhibit early symptoms of instability across multiple indicators. Similar conclusions were drawn by Pasternak et al. [13], Hassan et al. [10] and de Sousa Mello [51], who demonstrated that combining UAV photogrammetry, LiDAR, multispectral and thermal imagery significantly enhances early detection of settlement, erosion, gas or leachate-related damage. Our results reinforce these findings and further demonstrate that integrating multiple types of UAV data not only improves diagnostic accuracy but also enables causal interpretation of degradation processes. This multi-sensor approach provides valuable support for post-closure landfill management, offering a cost-effective, repeatable and highly informative monitoring solution that addresses both geotechnical and environmental risks.

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that the integration of UAV-based geometric, hydrological, multispectral, and thermal data provides an effective and comprehensive framework for detecting early-stage landfill cover degradation. The results showed that subsidence-driven surface depressions modify hydrological conditions, leading to water accumulation and concentrated runoff, which in turn cause vegetation stress and facilitate leachate emergence. NDVI proved to be a reliable bio-indicator of persistent instability, while LST enabled the detection of leachate seepage that was not visible in RGB or NDVI imagery. The combined analysis of dDSM, water flow modeling, NDVI and LST allowed for a holistic understanding of the interactions between deformation, moisture, vegetation condition, and subsurface processes. Although UAV-based monitoring is subject to operational restrictions such as airspace regulations, weather limitations and flight altitude constraints, it offers substantial advantages over traditional ground-based inspections. In particular, UAVs provide high-resolution spatial data, enable rapid and repeatable surveys, and significantly improve operator safety by eliminating direct exposure to hazardous landfill conditions such as leachate, biogas emissions, or unstable surfaces. In addition, UAV-based remote sensing is relatively low-cost compared to manned aerial surveys or satellite imagery, allows for efficient data acquisition over large and difficult-to-access areas such as landfills, and can be carried out at high temporal frequency to monitor dynamic changes and detect emerging damage at an early stage. Moreover, increasing climate variability, including more intense rainfall events and longer dry periods, is likely to amplify deformation, runoff and leachate-related processes, further highlighting the need for continuous and high-resolution monitoring. As many remediated landfills are being considered for redevelopment into public or recreational spaces, ensuring the long-term stability and integrity of the cover is essential for safe post-closure land reuse. UAV-based monitoring can support this process by providing detailed spatial information on deformation, drainage, vegetation health and leachate migration, enabling informed decisions before converting landfills into public-use areas. Therefore, the proposed multi-sensor UAV approach represents a valuable tool for post-closure landfill management and has strong potential for broader application to other engineered earth structures. Future research should focus on multi-seasonal or multi-year monitoring and the integration of UAV data with in situ measurements to further enhance diagnostic capability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.P.; methodology, G.P.; software, G.P. and Ł.W.; validation, E.K., J.Z.-P., and A.P.; investigation, G.P.; resources, G.P. and J.J.; data curation, G.P. and J.J.; writing—original draft preparation, G.P., Ł.W., and A.P.; writing—review and editing, E.K., J.Z.-P., and A.P.; visualization, G.P. and Ł.W.; supervision, E.K. and J.Z.-P.; funding acquisition, A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the co-author Grzegorz Pasternak, e-mail: grzegorz_pasternak@sggw.edu.pl.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Waste Management Landfills: An Insight. Available online: https://www.actenviro.com/waste-management-landfill/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Landfill Remediation: Transforming Polluted Sites into Assets. Available online: https://vertasefli.co.uk/landfill-remediation-transforming-polluted-sites-into-assets/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Koda, E.; Grzyb, M.; Osiński, P.; Vaverková, M.D. Analysis of Failure in Landfill Construction Elements. MATEC Web Conf. 2019, 284, 03002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjeldsen, P.; Barlaz, M.A.; Rooker, A.P.; Baun, A.; Ledin, A.; Christensen, T.H. Present and Long-Term Composition of MSW Landfill Leachate: A Review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2002, 32, 297–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasternak, G.; Koda, E.; Zaczek-Peplinska, J. Application of Remote Sensing Methods in Monitoring Changes at Reclaimed Landfills. In Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koda, E.; Miszkowska, A.; Sieczka, A.; Osiński, P. Heavy Metals Contamination within Restored Landfill Site. Environ. Geotech. 2018, 7, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koda, E.; Osiński, P.; Podlasek, A.; Markiewicz, A.; Winkler, J.; Vaverková, M.D. Geoenvironmental Approaches in an Old Municipal Waste Landfill Reclamation Process: Expectations vs. Reality. Soils Found. 2023, 63, 101273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podlasek, A.; Vaverková, M.D.; Koda, E.; Jakimiuk, A.; Martínez Barroso, P. Characteristics and Pollution Potential of Leachate from Municipal Solid Waste Landfills: Practical Examples from Poland and the Czech Republic and a Comprehensive Evaluation in a Global Context. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 332, 117328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation of the Minister of the Environment of 30 April 2013 on Landfills (Journal of Laws 2022, Item 1902). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20220001902 (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Hassan, S.Z.; Sun, P.; Gokgoz, M.; Chen, J.; Reinhart, D.R.; Gustitus-Graham, S. UAV-Based Approach for Municipal Solid Waste Landfill Monitoring and Water Ponding Issue Detection Using Sensor Fusion. J. Hydroinformatics 2023, 25, 2107–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Qin, R.; Chen, X. Unmanned Aerial Vehicle for Remote Sensing Applications—A Review. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyard, C.; Beaumont, B.; Grippa, T.; Hallot, E. UAV-Based Landfill Land Cover Mapping: Optimizing Data Acquisition and Open-Source Processing Protocols. Drones 2022, 6, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasternak, G.; Zaczek-Peplinska, J.; Pasternak, K.; Jóźwiak, J.; Pasik, M.; Koda, E.; Vaverková, M.D. Surface Monitoring of an MSW Landfill Based on Linear and Angular Measurements, TLS, and LiDAR UAV. Sensors 2023, 23, 1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Bao, H.; Zhang, J.; Lan, H.; Adriano, B.; Koshimura, S.; Yuan, W. Accurate Digital Reconstruction of High-Steep Rock Slope via Transformer-Based Multi-Sensor Data Fusion. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, H.; Lv, H.; Lan, H.; Liu, C.; Li, L.; Chen, W.; Liu, S. Evaluation Method of Grotto Rock Mass Deterioration Based on Infrared Thermography. J. Cult. Herit. 2024, 70, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Peng, Z.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, J.; Lu, Z.; Baumann, A.; Du, Y. Real-Time Detection of Ground Objects Based on Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Remote Sensing with Deep Learning: Application in Excavator Detection for Pipeline Safety. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasternak, G.; Pasternak, K.; Koda, E.; Ogrodnik, P. Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Photogrammetry for Monitoring the Geometric Changes of Reclaimed Landfills. Sensors 2024, 24, 7247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruch, A.F.; Camargo, K.R.; Carneiro, M.; Fragali, G.; Klumb, V.; de Britto Monte, T.L.; Borges, I.C. Vegetation Density Mapping of Urban Solid Waste Landfill Coverage Using Vegetation Indexes Obtained with UAV. Rev. Gestão Soc. Ambient. 2024, 18, e09730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanda, G.; Balsi, M.; Fallavollita, P.; Chiarabini, V. A UAV-Based Thermal-Imaging Approach for the Monitoring of Urban Landfills. Inventions 2020, 5, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinnathamby, G.; Phillips, D.H.; Sivakumar, V.; Paksy, A. Landfill cap models under simulated climate change precipitation: Assessing long-term infiltration using the HELP model. Environ. Earth Sci. 2024, 83, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, C.A. Climate Change Impacts on Geotechnical Infrastructure. In Geotechnical Engineering Challenges to Meet Current and Emerging Needs of Society; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 2838–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apriyono, A.; Yuliana, Y.; Kamchoom, V.; Leung, A.K.; Jotisankasa, A.; Liangtong, Z. The Effect of Desiccation Cracks on Water Infiltration in Landfill Cover under Extreme Climate Scenarios. Waste Manag. 2025, 196, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandalai, S.; John, N.J.; Patel, A. Effects of climate change on geotechnical infrastructures—State of the art. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 16878–16904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, S.; Hollaender, H.; Yuan, Q. Impact of heat and contaminants transfer from landfills to permafrost subgrade in arctic climate: A review. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2023, 206, 103737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.R.; Muthukkumaran, K.; Sharma, C.; Shukla, A.K.; Sharma, S.K. Rainfall-Induced Slope Instability in Tropical Regions Under Climate Change Scenarios. Water 2025, 17, 1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arifuzzaman; Rahman, M.M.; Karim, M.R.; Hewa, G.A.; Rawlings, R.; Iqbal, A. Phytocapping for Municipal Solid Waste Landfills: A Sustainable Approach. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Zhang, J.; Tang, C.S.; Jiang, G.; Bogaard, T. Impact of dynamic desiccation cracks on hydrological processes and stability in expansive clay slopes: A coupled dual-permeability modeling approach. Eng. Geol. 2025, 357, 108377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lv, G.; Wang, D.; Su, W.; Wei, Z. Erosion Failure of Slope in a Dump with Ground Fissure under Heavy Rain. Water 2022, 14, 3425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, J.H.; Spencer, K.L. Will flooding or erosion of historic landfills result in a significant release of soluble contaminants to the coastal zone? Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 724, 138150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, R.J.; Beaven, R.P.; Stringfellow, A.; Monfort, D.; Le Cozannet, G.; Wahl, T.; Gebert, J.; Wadey, M.; Arns, A.; Spencer, K.L.; et al. Coastal landfills and rising sea levels: A challenge for the 21st century. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 710342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, A.; Daigavane, P.B. Analysis and modelling of slope failures in municipal solid waste dumps and landfills: A review. Nat. Environ. Pollut. Technol. 2021, 20, 825–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, X.; Fang, M.; Wang, Y. Climate change affects land-disposed waste. Nat. Clim. Change 2021, 11, 1004–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Fang, Y.; Pan, X.; Zhang, J.; Xu, H. Global study on slope instability modes based on 62 municipal solid waste landfills. Waste Manag. Res. 2020, 38, 1389–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Shu, S.; Ai, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Li, Y.; Xu, G. Effect of elevated temperature on solid waste shear strength and landfill slope stability. Waste Manag. Res. 2021, 39, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, L.T.; Guo, X.G.; Sun, Q.Q.; Chen, Y.M.; Chen, Z.Y. The 2015 Shenzhen catastrophic landslide in a construction waste dump: Analyses of undrained strength and slope stability. Acta Geotech. 2021, 16, 1247–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, J.H.; Spencer, K.L. Potential pollution risks of historic landfills in England: Further analysis of climate change impacts. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Water 2024, 11, e1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetri, J.K.; Reddy, K.R. Advancements in municipal solid waste landfill cover system: A review. J. Indian Inst. Sci. 2021, 101, 557–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alao, J.O. The factors influencing the landfill leachate plume contaminants in soils, surface and groundwater and associated health risks: A geophysical and geochemical view. Public Health Environ. 2025, 1, 20–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lu, H.; Liu, M.; Dong, Y. Evolution of solidified municipal sludge used as landfill cover material under wet–dry cycles: Mechanical characteristics, microstructural, and seepage properties. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Zhang, Q.; Lu, Z.; Wei, W.; Lu, H.; Chen, H. Investigation on the Hydraulic Response of a Bioengineered Landfill Cover System Subjected to Extreme Drying–Wetting Cycles. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2024, 83, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schupp, S.; De la Cruz, F.B.; Cheng, Q.; Call, D.F.; Barlaz, M.A. Evaluation of the temperature range for biological activity in landfills experiencing elevated temperatures. ACS EST Eng. 2020, 1, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinci, E.; Arslankaya, E. Factors Affecting Stability and Slope Failure of Landfill Sites: A Review. In Proceedings of the EurAsia Waste Management Symposium, Istanbul, Türkiye, 24–26 October 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hoy, M.; Doan, C.B.; Horpibulsuk, S.; Suddeepong, A.; Udomchai, A.; Buritatum, A.; Chaiwan, A.; Doncommul, P.; Arulrajah, A. Investigation of a large-scale waste dump failure at the Mae Moh mine in Thailand. Eng. Geol. 2024, 329, 107400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.W.; Liu, L.; Yang, Z.X.; Fu, X.Y. Toward a sound understanding of a large-scale landslide at a mine waste dump, Anshan, China. Landslides 2023, 20, 2583–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, K.; Kumar, H.; Singh, L.; Sawarkar, A.D.; Kumar, M.; Kumar, S. Phytocapping Technology for Sustainable Management of Contaminated Sites: Case Studies, Challenges, and Future Prospects. In Phytoremediation Technology for the Removal of Heavy Metals and Other Contaminants from Soil and Water; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 601–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Meteorology and Water Management—National Research Institute (IMGW-PIB). Meteorological Data Portal. Available online: https://danepubliczne.imgw.pl (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Wang, L.; Liu, H. An efficient method for identifying and filling surface depressions in digital elevation models for hydrologic analysis. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2006, 20, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Rich, P.M.; Price, K.P.; Kettle, W.D. Relations between NDVI and tree productivity in the central Great Plains. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2004, 25, 3127–3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koda, E.; Winkler, J.; Wowkonowicz, P.; Černý, M.; Kiersnowska, A.; Pasternak, G.; Vaverková, M.D. Vegetation changes as indicators of landfill leachate seepage locations: Case study. Ecol. Eng. 2022, 174, 106448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedano-Cibrián, J.; de Luis-Ruiz, J.M.; Pérez-Álvarez, R.; Pereda-García, R.; Tapia-Espinoza, J.D. 4D models generated with UAV photogrammetry for landfill monitoring: Thermal control of Municipal Solid Waste (MSW) landfills. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 13164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa Mello, C.C.; Salim, D.H.C.; Simões, G.F. UAV-based landfill operation monitoring: A year of volume and topographic measurements. Waste Manag. 2022, 137, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.