Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Proposes YOLO-CMFM for multimodal remote sensing object detection.

- Designs LEGA, BCA, and CGG for edge-guided and gated cross-attention fusion.

What are the implications of the main finding?

- YOLO-CMFM sets a new SOTA with robust, transferable multimodal detection.

- Robust performance across diverse remote sensing imaging conditions.

Abstract

To address the challenges of cross-modal feature misalignment and ineffective information fusion caused by the inherent differences in imaging mechanisms, noise statistics, and semantic representations between visible and synthetic aperture radar (SAR) imagery, this paper proposes a multimodal remote sensing object detection method, namely YOLO-CMFM. Built upon the Ultralytics YOLOv11 framework, the proposed approach designs a Cross-Modal Fusion Module (CMFM) that systematically enhances detection accuracy and robustness from the perspectives of modality alignment, feature interaction, and adaptive fusion. Specifically, (1) a Learnable Edge-Guided Attention (LEGA) module is constructed, which leverages a learnable Gaussian saliency prior to achieve edge-oriented cross-modal alignment, effectively mitigating edge-structure mismatches across modalities; (2) a Bidirectional Cross-Attention (BCA) module is developed to enable deep semantic interaction and global contextual aggregation; (3) a Context-Guided Gating (CGG) module is designed to dynamically generate complementary weights based on multimodal source features and global contextual information, thereby achieving adaptive fusion across modalities. Extensive experiments conducted on the OGSOD 1.0 dataset demonstrate that the proposed YOLO-CMFM achieves an of 96.2% and an :95 of 75.1%. While maintaining competitive performance comparable to mainstream approaches at lower IoU thresholds, the proposed method significantly outperforms existing counterparts at high IoU thresholds, highlighting its superior capability in precise object localization. Also, the experimental results on the OSPRC dataset demonstrate that the proposed method can consistently achieve stable gains under different kinds of imaging conditions, including diverse SAR polarizations, spatial resolutions, and cloud occlusion conditions. Moreover, the CMFM can be flexibly integrated into different detection frameworks, which further validates its strong generalization and transferability in multimodal remote sensing object detection tasks.

1. Introduction

With the rapid advancement of multi-source remote sensing platforms such as satellites and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), deep learning-based remote sensing object detection has become a key research area in intelligent remote sensing interpretation. It has been extensively applied in fields including maritime surveillance, urban planning, and disaster early-warning systems [1,2]. The traditional visible remote sensing imagery provides abundant spatial and texture details, enabling clear visual representation of the geometric and spectral characteristics of ground objects. However, visible imaging is strongly constrained by external illumination conditions. Under low-light or cloud-covered environments, target features are vulnerable to interference, resulting in decreased detection accuracy and unstable detection performance [3].

In contrast, the synthetic aperture radar (SAR), which operates via active microwave imaging, is capable of penetrating clouds and fog, thus providing stable observation under all-weather, day-and-night conditions. These characteristics make SAR particularly advantageous in complex environments. However, owing to the coherent nature of SAR imaging, it is inherently affected by speckle noise, limited texture representation, and less intuitive semantic information, all of which hinder accurate visual interpretation [4]. Current remote sensing object detection methods predominantly rely on single-modality data, limiting their ability to exploit the complementary relationships among heterogeneous modalities. As a result, these methods struggle to sufficiently characterize target features and generalize well across diverse imaging conditions [5]. Therefore, a critical challenge in multimodal remote sensing object detection is how to effectively fuse the complementary information between visible and SAR modalities to enhance detection accuracy and robustness.

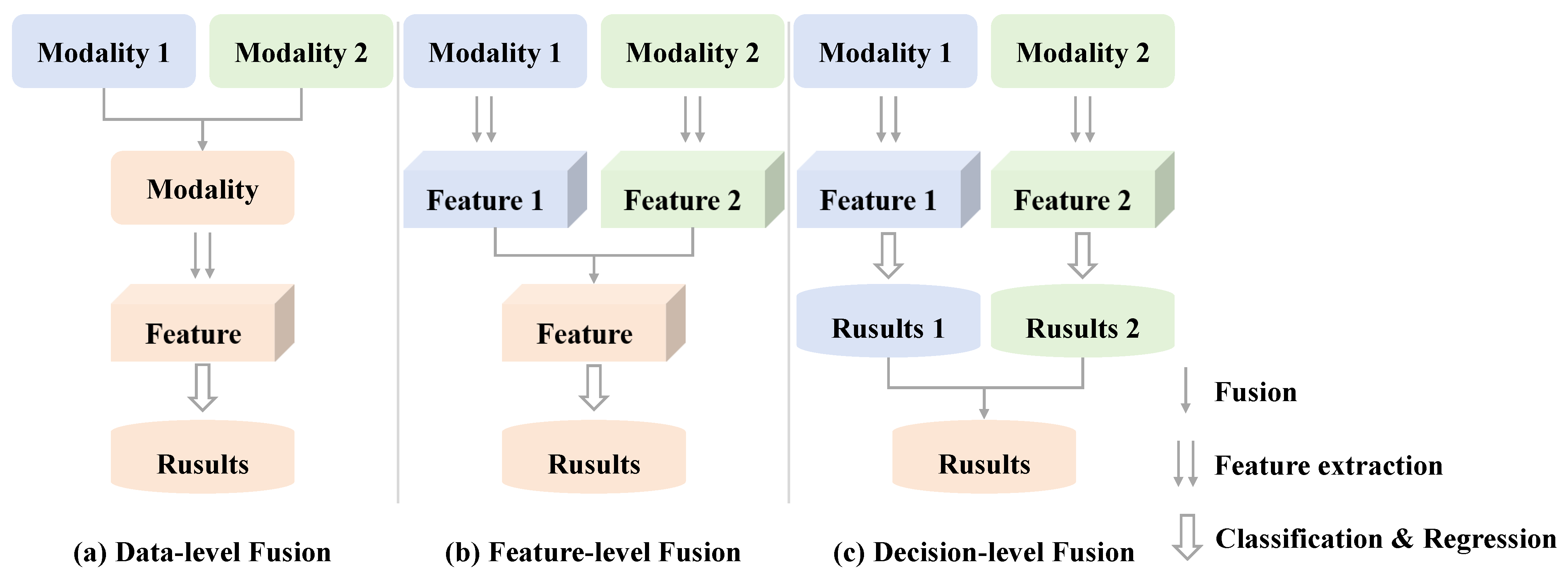

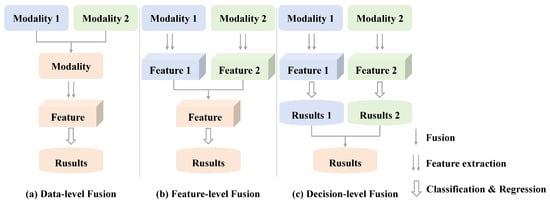

With the rapid advancement of deep learning, multimodal remote sensing object detection has gained increasing attention, giving rise to a variety of fusion strategies. Fundamentally, multimodal fusion is a multi-source data integration process that combines information from different sensors, spectral bands, or imaging mechanisms (such as visible, infrared, SAR, hyperspectral, and LiDAR) to achieve complementary feature representation and robust ground-object recognition [6]. From the perspective of fusion hierarchy, existing methods can generally be classified into data-level fusion, feature-level fusion, and decision-level fusion [7]. Data-level fusion integrates multiple source images at the pixel or band level during the input stage through techniques such as channel stacking, weighted averaging, or principal component transformation. Although this approach maximizes the use of raw information, it is highly sensitive to spatial misalignment and noise interference, which may introduce artifacts or modality inconsistency. Feature-level fusion jointly models multimodal features within the intermediate layers of deep neural networks. By facilitating cross-modal feature interaction, it strengthens semantic representation and enhances complementary information. This has become the mainstream strategy in the current research field of multimodal remote sensing object detection. Decision-level fusion combines the independent outputs of different modalities at the final prediction stage using strategies such as voting, confidence weighting, or multi-branch ensemble learning. While this approach offers flexibility, information exchange occurs only after decision-making, limiting its ability to exploit fine-grained complementary features across modalities. The schematic comparison of these three fusion paradigms is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Illustration of multi-modal fusion strategies.

Existing research on multimodal remote sensing object detection primarily centers on feature-level fusion, where deep neural architectures are employed to enable high-level semantic collaboration across modalities. In recent years, feature-level fusion has advanced substantially, giving rise to various improvement strategies. Early methods typically adopted feature concatenation or weighted fusion, directly stacking or linearly combining features from different modalities. Although such approaches are conceptually simple and can improve detection performance to some extent, the absence of modality alignment and deep semantic interaction mechanisms often amplifies redundant information and propagates noise across modalities. For example, Sharma et al. [8] applied multimodal fusion through feature concatenation and cross-product operations, yet their method still exhibited limited performance in complex scenarios.

To mitigate the degradation of low-quality modalities, several studies have incorporated super-resolution reconstruction into detection frameworks. For example, Zhang et al. [9] introduced auxiliary super-resolution learning to enhance the detailed representation of small objects, which improved detection accuracy but incurred additional training overhead and created a strong dependence on reconstruction quality, ultimately resulting in unstable performance in visible-SAR multimodal scenarios.

With the advent of Transformer architectures [10] and cross-modal attention mechanisms, researchers began to pay attention to global dependency modeling across modalities. Fang et al. [11] were among the first to leverage the long-range modeling capability of Transformers to capture cross-modal contextual associations, thereby enhancing the comprehensiveness of multimodal feature interaction. Shen et al. [12] further improved discriminative representation through query-guided cross-attention. However, the absence of adaptive modulation still resulted in fixed inter-modal weighting, limiting the flexibility of fusion.

Building upon these foundations, several studies have emphasized structural optimization and semantic enhancement at the feature-fusion level. Guo et al. [13] incorporated a cosine-similarity-guided feature decomposition and fusion module into YOLOv8, achieving lightweight cross-modal alignment through common-specific feature decomposition. Fei et al. [14] proposed an attention-guided differential fusion mechanism based on YOLOv5 to strengthen complementary feature modeling and salient-region guidance. Wang et al. [15] designed a dual-branch asymmetric attention backbone and feature fusion pyramid, enabling semantic-detail synergy from backbone to fusion layers.

It is noteworthy that most existing multimodal detection research has focused on visible-infrared settings, primarily because these modalities share relatively similar imaging mechanisms, which facilitates feature alignment. Moreover, several large-scale multimodal datasets are publicly available, such as M3FD [16], VEDAI [17], and DroneVehicle [18]. In contrast, visible-SAR multimodal detection faces considerably greater challenges. On one hand, visible and SAR modalities exhibit substantial differences in imaging mechanisms, statistical distributions, and semantic representations, where visible imagery emphasizes spectral and texture information, whereas SAR primarily captures geometric structure. These disparities lead to distinct feature-space distributions, making direct alignment and fusion difficult. On the other hand, high-quality and well-registered visible-SAR datasets are difficult to obtain, and publicly available resources remain limited, thereby constraining large-scale empirical research.

Therefore, achieving efficient and adaptive visible-SAR multimodal feature fusion that fully leverages cross-modal complementarity and structural consistency remains a key challenge in multimodal remote sensing object detection. In summary, current approaches still exhibit three major limitations when applied to visible-SAR multimodal detection tasks as follows: (1) The lack of explicit edge and structural modeling weakens spatial detail representation during fusion and degrades boundary discrimination of detected objects. (2) Cross-modal attention mechanisms suffer from insufficient semantic alignment, which limits their ability to distinguish subtle target features. (3) Static fusion strategies without dynamic regulation cannot adjust modality contributions according to scene variations and target characteristics, thereby reducing fusion robustness.

To address the aforementioned challenges, this paper proposes a visible-SAR multimodal remote sensing object detection framework based on the edge-guided and gated cross-attention method, namely YOLO-CMFM. The proposed YOLO-CMFM fully utilizes the complementary characteristics of visible and SAR modalities to enable efficient, adaptive, and robust cross-modal fusion. The main contributions of this study are summarized below.

- A visible-SAR multimodal object detection method, namely YOLO-CMFM, is proposed. This method, built upon the Ultralytics YOLOv11 framework, incorporates a novel Cross-Modal Fusion Module (CMFM), which establishes a progressive fusion mechanism characterized by edge guidance, contextual interaction and gated regulation. While preserving the integrity of feature representation, the proposed method enables hierarchical semantic collaboration and dynamic information balancing from shallow to deep layers, thereby enhancing the effectiveness and stability of multimodal feature fusion. The proposed CMFM consists of the following three key components, i.e., the Learnable Edge-Guided Attention (LEGA) module, the Bidirectional Cross-modal Attention (BCA) module, and the Context-Guided Gate (CGG) module:

- The LEGA module integrated a learnable Gaussian saliency prior to performing joint channel-spatial modulation and edge-constrained modeling of multimodal features, which can effectively suppress SAR speckle noise and mitigate cross-modal edge-structure misalignment.

- The BCA module utilizes a bidirectional cross-attention mechanism to achieve deep semantic interaction and global contextual aggregation across modalities, and meanwhile to reduce computational complexity through channel reduction and reconstruction.

- The CGG module incorporates multimodal source features and global contextual information to dynamically generate complementary gating weights across modalities, which can effectively suppress redundant information and promote adaptive feature fusion.

- Extensive experiments were conducted on the OGSOD 1.0 and OSPRC datasets, which cover diverse spatial resolutions, SAR polarization modes, and cloud occlusion conditions. The results demonstrate that compared with classical single-modal and multimodal detection models, the proposed YOLO-CMFM achieves superior overall performance, attaining a competitive of 96.2% and a substantially improved :95 of 75.1%.Particularly, the model can gain more notable increases at higher IoU thresholds, showing its strengths in precise object localization. Moreover, YOLO-CMFM can still maintain stable performance under diverse imaging conditions, and the proposed CMFM can also be seamlessly integrated into various detection frameworks, which further verifies its robustness, generality and transferability in multimodal object detection.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overall Framework

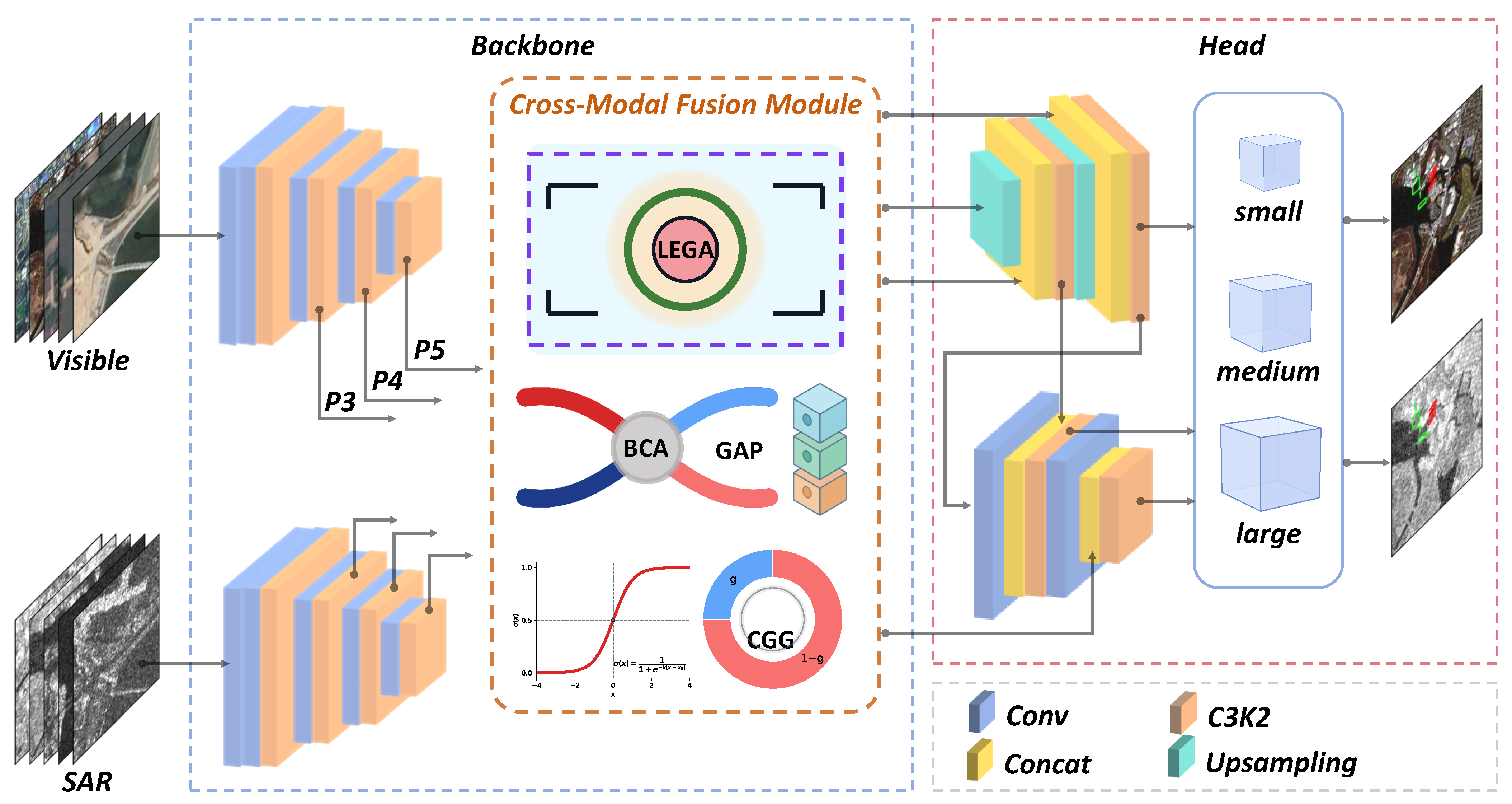

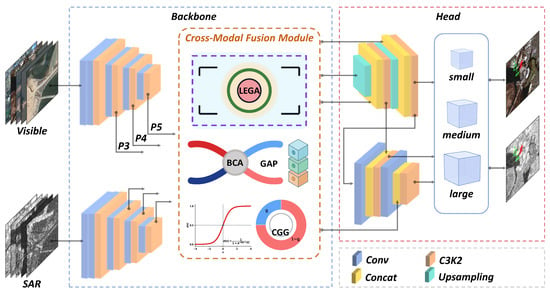

The overall architecture of the proposed YOLO-CMFM is presented in Figure 2. The model is built upon the single-stage object detection framework of Ultralytics YOLOv11 [19], selected for its lightweight and high-efficiency end-to-end design, which provides strong multi-scale feature extraction capability and has been extensively validated across diverse detection tasks [20,21,22].

Figure 2.

Overall architecture of the proposed YOLO-CMFM method. It employs a dual-branch backbone to independently extract multi-scale features from visible and SAR images. A Cross-Modal Fusion Module is integrated into the P3, P4, and P5 layers to enable adaptive semantic interaction and cross-modal feature fusion. The fused representations are subsequently aggregated and upsampled in the detection head to produce multi-scale predictions for small, medium, and large objects.

The proposed YOLO-CMFM fully leverages the complementary properties of visible and SAR modalities. Through cross-modal attention and gated interaction mechanisms, it achieves deep semantic collaboration and adaptive feature fusion across layers, thereby enhancing detection accuracy and robustness under complex imaging conditions.

The overall architecture consists of three major components: (1) a dual-branch feature extraction network (Backbone), (2) a Cross-Modal Fusion Module (CMFM), and (3) a multi-scale feature aggregation and decoupled detection head (Head).

The overall workflow is as follows: First, the dual-branch backbone independently extracts multi-scale features from the visible and SAR images. Then, the CMFM is embedded into the aligned feature layers (P3, P4, P5) to enable deep semantic interaction and adaptive cross-modal fusion. Finally, the fused features are aggregated and upsampled along the detection path to integrate multi-scale semantic information and are subsequently passed to the decoupled detection head for object classification and bounding-box regression.

To comply with the predefined input specifications of YOLOv11, the original images are uniformly resized to pixels using aspect-ratio-preserving bilinear interpolation, thereby ensuring sufficient extraction of multi-scale features. Let the input images be the visible-light modality and the SAR modality , with their corresponding multi-scale feature representations denoted as and , where indicates different feature levels. The functions of each network component are described as follows:

- (1)

- Backbone

To preserve the independence and complementarity of feature representations between the visible and SAR modalities, a parameter-unshared dual-branch feature extraction structure is employed. Each branch is composed of convolutional blocks and C3K2 modules, generating multi-scale features through progressive downsampling. The visible branch focuses on capturing rich texture and spectral details, whereas the SAR branch emphasizes geometric structure and edge modeling, forming complementary semantic-level representations. This establishes a solid foundation for subsequent cross-modal fusion.

- (2)

- CMFM

At each aligned feature level, a CMFM is embedded to facilitate deep semantic interaction and adaptive fusion between the two modalities. The CMFM consists of three submodules, which together constitute a progressive fusion strategy characterized by sequential edge guidance, context interaction, and gated regulation. These submodules operate in a mutually complementary manner rather than functioning as a simple cascaded pipeline, which substantially enhances the sufficiency and adaptivity of cross-modal feature exchange and semantic integration.

- (3)

- Head

The fused multi-scale features are aggregated and upsampled to further integrate semantic and spatial information before being fed into the decoupled detection head of YOLOv11. The detection head comprises separate classification and regression branches, which operate at small, medium, and large scales to perform object category recognition and bounding-box regression, respectively.

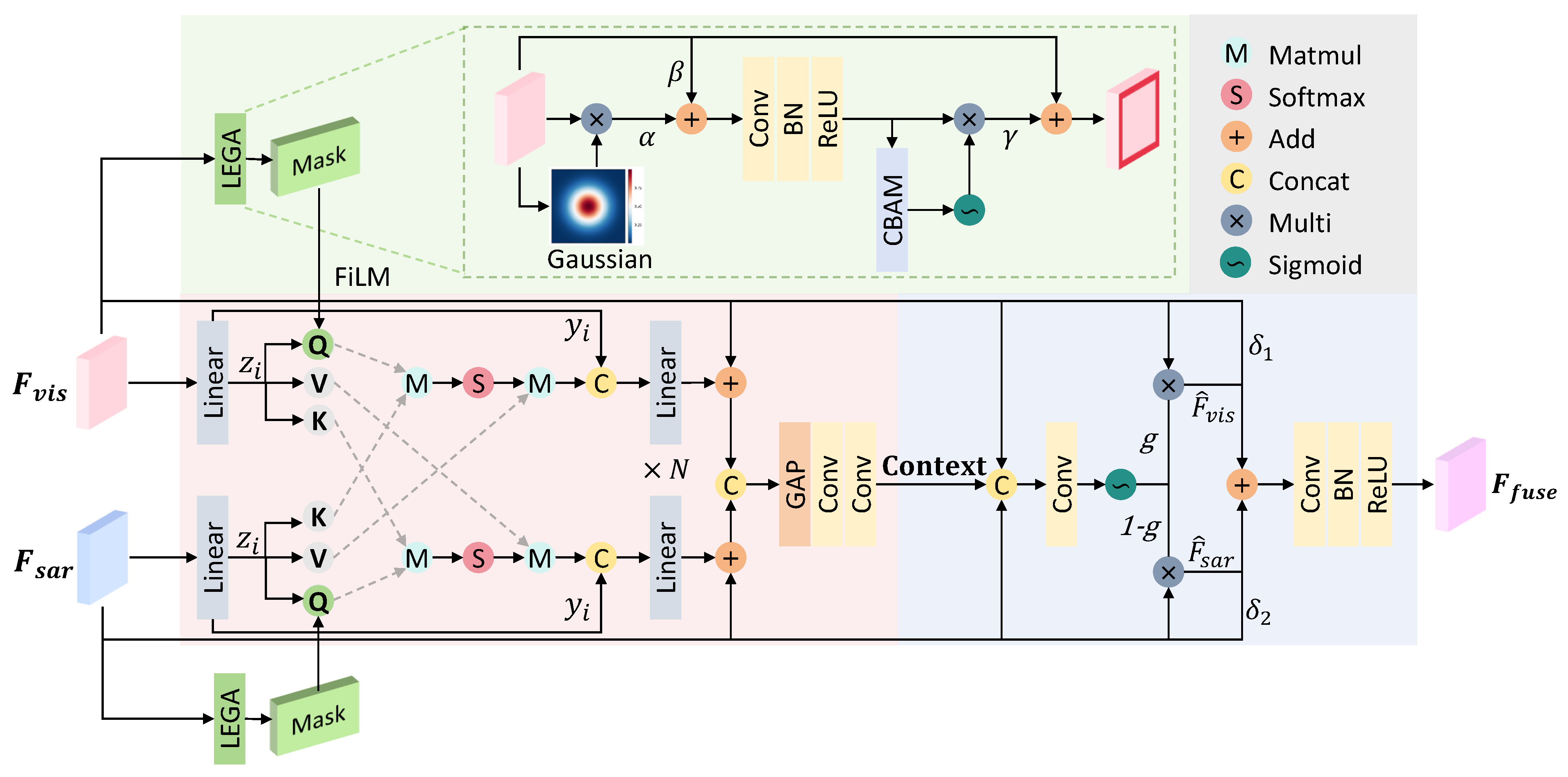

2.2. CMFM

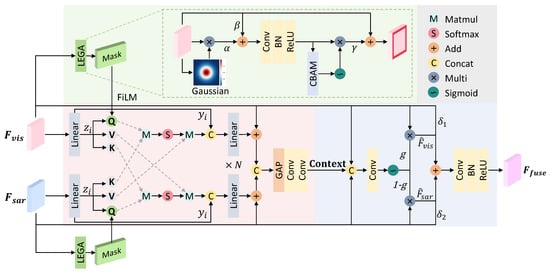

The structure of the proposed CMFM is presented in Figure 3. This module preserves the integrity of feature representation while achieving structural alignment and adaptive fusion between modalities. Given a pair of same-scale features , the fused output feature is denoted as , where B, C, H, and W denote the batch size, channel number, height, and width of the feature maps, respectively. The CMFM adheres to a design philosophy of edge guidance, context interaction, and gated regulation, and is composed of three submodules.

Figure 3.

Detailed structure of the proposed CMFM. It incorporates three coordinated submodules. (1) The LEGA module (green) achieves edge-oriented cross-modal alignment with Gaussian-guided saliency prior and CBAM attention. (2) The BCA module (red) performs deep semantic interaction through bidirectional cross-modal attention and global contextual aggregation, and integrates sequence downsampling, which reduces the standard attention complexity to . (3) The CCG module (blue) adaptively balances visible and SAR contributions through complementary gating.

2.2.1. LEGA

In visible-SAR scenarios, the accuracy of target recognition and the continuity of object boundaries are highly dependent on the quality of edge structures. However, speckle noise in SAR images often obscures salient edge information, thereby weakening boundary distinctiveness [23]. To alleviate the structural discrepancies and noise-induced degradation between visible and SAR modalities, the LEGA module is designed to enhance edge features, as illustrated in the green section of Figure 3.

The core idea is to enhance edge-region responses through a learnable Gaussian saliency prior, which adaptively strengthens local edge structures while preserving background smoothness. The Gaussian prior provides a differentiable saliency-guided mechanism that aligns with the natural spatial diffusion characteristics of edges [24,25]. In addition, the LEGA module maintains a stable residual flow, effectively suppressing gradient oscillations during the early training stage. The computational process is organized into the following two components.

- (1)

- Structural Saliency Mask Generation

Let the input feature be denoted as . The LEGA module generates a refined saliency mask M through a composite Gaussian-guided subnetwork , which operates in three stages.

First, a fixed two-dimensional Gaussian kernel is constructed to serve as a consistent geometric prior. Its weights are initialized according to the standard Gaussian distribution:

where denotes spatial coordinates and controls the smoothing scale. In this study, we set and , and the kernel is normalized such that . Crucially, this layer is set as non-trainable to introduce a deterministic structural bias.

Second, the input feature is processed by a depthwise convolutional layer utilizing the kernel K. This ensures that spatial filtering is applied independently to each channel, effectively suppressing speckle noise while preserving key semantic information. The response is stabilized via Batch Normalization and a ReLU activation function to yield the preliminary saliency feature ,

where ∗ denotes the depthwise convolution operation.

Third, to correct the boundary coarseness inherent in Gaussian smoothing, is fused with the original context and fed into a learnable refinement block . This block employs a bottleneck structure (cascaded , , and convolutions) to align the Gaussian response with precise object contours, producing the final mask M,

- (2)

- Edge-Guided Modulation and Adaptive Enhancement

Subsequently, the feature M is modulated through an affine transformation to obtain the edge-enhanced feature ,

where ⊙ represents element-wise multiplication, and , are learnable scalar coefficients that control the balance between the enhanced and residual components. Subsequently, a convolution-normalization-activation operation is applied to extract locally enhanced structural information,

Given that different channels contribute unequally to semantic representation, a CBAM (Convolutional Block Attention Module) [26] is introduced to generate a joint channel-spatial attention map, thereby enhancing feature discriminability and selectivity,

where denotes the sigmoid function. Finally, the enhanced feature A is fused back into the main branch through a controlled residual connection, producing the output feature ,

where is a learnable scaling factor, initialized to zero and gradually increased during training to enable smooth and stable transition from identity mapping to edge-guided modulation.

2.2.2. BCA

To achieve deep semantic interaction and adaptive feature alignment between the visible and SAR modalities, this study designs the BCA module. As illustrated in the red section of Figure 3, the module consists of three main components.

- (1)

- Channel Decoupling and Feature-wise Linear Modulation (FiLM) [27]

Given the input features of the visible and SAR modalities, , channel-wise separation is first performed to obtain local semantic features and cross-modal query features,

where , represents the local semantic feature that preserves modality-specific semantic information for subsequent fusion; represents the cross-modal query feature for interaction modeling.

In the reduced feature space, edge priors generated by the LEGA module are employed to modulate query features through a FiLM transformation,

where is a learnable modulation coefficient that controls the modulation strength. This design leverages edge-enhanced saliency information to guide cross-modal matching, ensuring that the fusion process focuses more on structurally salient regions.

- (2)

- Bidirectional Cross-Modal Attention

To enable global semantic interaction between visible and SAR modalities, a bidirectional cross-attention structure is constructed based on the classical self-attention mechanism [10]. The computation is defined as:

where denote the query, key, and value vectors, respectively, all generated from the input sequence through linear projection. represents the sequence length, and denotes the feature dimensionality of each attention head.

The computational complexity of standard attention is , which increases quadratically with the sequence length N. However, for remote sensing images with large spatial resolutions, such complexity becomes prohibitively expensive. To address this issue, inspired by the sequence downsampling strategy proposed by Zhao et al. [28], this study performs sparsified modeling along the sequence-length dimension to obtain reduced query, key, and value representations, which enables efficient modeling of global dependencies while achieving substantial feature compression:

where , and , with R denoting the downsampling factor. In this study, we adopt the efficient design from [28] by setting . This configuration effectively reduces the computational complexity from to .

Next, a bidirectional cross-modal interaction mechanism is constructed. The visible modality first serves as the query , while the SAR modality provides the key and value for one round of cross-attention. The process is then reversed, with the SAR modality querying the visible modality. To further enhance the interaction capability between modalities and better capture complex cross-modal patterns, a multi-head attention mechanism is introduced. Specifically, for each attention head , an independent attention map is computed, and the outputs from all heads are subsequently aggregated. The computation is defined as

The attended features are then concatenated with their respective local semantic features and linearly projected back to the original channel dimension to obtain the cross representations ,

This bidirectional interaction structure preserves modality symmetry while ensuring comprehensive global contextual alignment, significantly improving scene consistency and boundary discriminability of the target features.

- (3)

- Global Context Construction

To further integrate the global semantic relationships between visible and SAR modalities, a global contextual construction module is introduced to aggregate high-level semantic dependencies. The cross features from both branches are concatenated along the channel dimension and globally pooled using GAP (Global Average Pooling) to obtain a unified semantic descriptor. A lightweight MLP is then applied to generate a compact cross-modal global context embedding, where the MLP is implemented with two convolutional layers.

where denotes the fused global contextual vector, and is the dimension of the global semantic embedding. It serves as a global semantic prior for the CGG module, guiding adaptive modality weighting and enforcing semantic consistency during cross-modal fusion.

2.2.3. CGG

During the fusion stage, the contribution of different modality features to target recognition is highly dynamic. To address this issue, the CGG module is proposed to achieve adaptively adjusted modality contributions through joint spatial-channel gating. Inspired by dynamic selection mechanisms [29] and gated fusion strategies [30], this design enables context-conditioned adaptive gating, selectively enhancing complementary and discriminative modality features while effectively suppressing redundant or conflicting information. As illustrated in the blue section of Figure 3, the CGG module takes as input the dual-branch outputs of the visible and SAR modalities together with the global context generated by the BCA module, which can be divided into two parts.

- (1)

- Context-Conditioned Complementary Gating

Let and denote the visible and SAR feature, respectively, and C represent the global contextual embedding obtained from the previous stage. The contextual vector C is first broadcast across the spatial dimensions to generate an expanded context tensor . , , and are then concatenated along the channel dimension to form the joint representation ,

A pointwise convolution followed by a Sigmoid activation is applied to generate a pixel-wise gating map ,

where denotes the sigmoid function. This operation adaptively assigns gating weights across both spatial and channel dimensions, enabling refined feature reweighting between modalities. To prevent instability caused by simultaneous amplifying or suppressing both modalities within the same spatial region, a complementary gating strategy is adopted,

This complementary mechanism, similar to soft attention [29], ensures that at each spatial location only one modality predominates, effectively reducing redundancy and conflict between modalities. The gated features are computed as

where ⊙ denotes element-wise multiplication.

- (2)

- Residual Scaling and Lightweight Refinement

To alleviate feature distribution mismatch and stabilize training, learnable residual scaling factors (initialized to 0.5) are introduced after gating fusion, forming a residual smoothing path that preserves gradient flow.

When and , the operation reduces to additive fusion, , ensuring stable initialization and allowing the model to progressively learn modality-specific weighting differences during training.

To further align modality distributions and enhance feature discriminability, a lightweight refinement head module is applied using convolution and nonlinear activation for channel-domain normalization and mapping.

This operation compresses redundant channels and strengthens semantic responses, producing the final fused feature map , which is subsequently passed to the detection head for multi-scale aggregation, classification, and bounding-box regression.

Overall, the CGG module performs pixel-wise adaptive modality selection in the spatial domain and weighted residual refinement in the channel domain. It effectively suppresses redundancy and modality bias while enhancing fusion stability and robustness, thereby significantly improving the consistency and complementarity of cross-modal feature integration.

2.3. Loss Function

To enable end-to-end optimization of multimodal feature fusion, the proposed CMFM is seamlessly integrated into the Ultralytics YOLOv11 architecture while preserving the original detection head design and loss functions, thereby facilitating joint training from multimodal feature extraction to final detection prediction. The detection head contains two independent branches for object classification and bounding-box regression, and the total loss is formulated as

where denotes the Focal Loss for addressing class imbalance; represents the Complete IoU Loss for bounding-box regression; is the Distribution Focal Loss for refine boundary localization. The weighting coefficients , , are set to 7.5, 0.5, and 1.5, respectively, consistent with the original YOLOv11 configuration.

3. Results

3.1. Datasets

To comprehensively evaluate the detection performance and generalization ability of the proposed YOLO-CMFM, two representative visible-SAR multimodal remote sensing object detection datasets are selected, i.e., OGSOD 1.0 and OSPRC.

- (1)

- OGSOD 1.0 Dataset

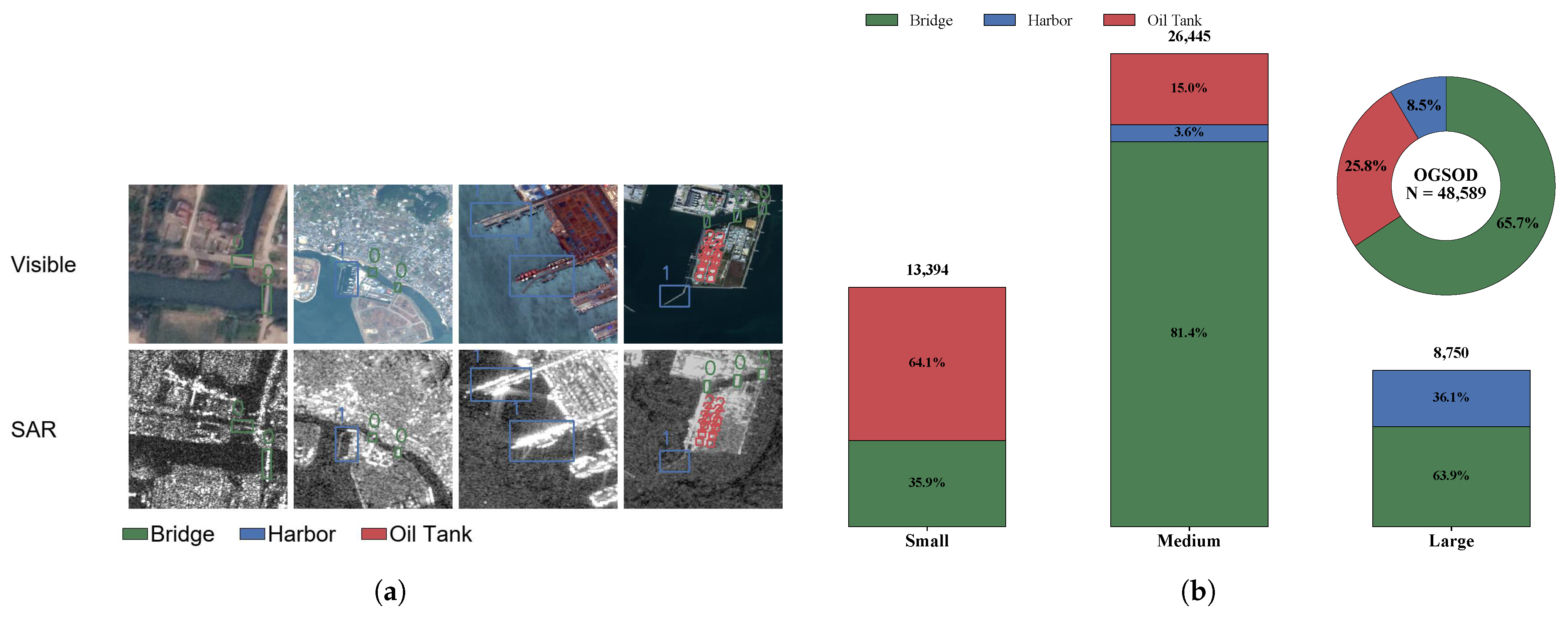

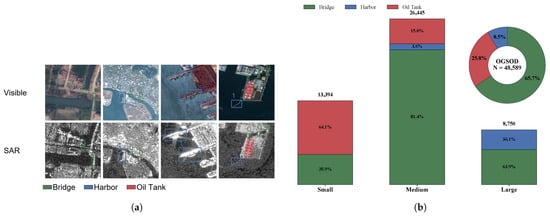

The OGSOD 1.0 dataset [31] is a newly released large-scale benchmark for visible-SAR multimodal remote sensing object detection. It contains 14,665 pairs of training images and 3666 pairs of testing images, with more than 48,000 annotated instances in total. Each sample consists of a co-registered pair of visible and SAR images. The annotated objects cover three representative categories: Bridge, Harbor, and Oil Tank.

The SAR images are collected from the GF-3 satellite (3 m resolution), while the visible images are sourced from Google Earth (10 m resolution). To ensure spatial consistency, the images from both modalities are mapped to the same spatial resolution using ENVI software (version 6.0) and precisely aligned at the pixel level, and the co-registered image pairs are cropped into slices with dimensions of pixels. This dataset provides high-quality co-registered imagery for investigating cross-modal object detection and has become an important benchmark in the visible-SAR domain. Figure 4a presents typical examples of visible-SAR image pairs in the OGSOD 1.0 dataset, and Figure 4b summarizes the statistical characteristics of target categories and scale distributions.

Figure 4.

(a) Visualization of visible and SAR image pairs in OGSOD 1.0, where bridges, harbors, and oil tanks are marked with green, blue, and red boxes, respectively. (b) Statistical characteristics of the OGSOD 1.0 dataset, where the bar chart depicts the number of annotated instances across three scales (small, medium, large), and the donut chart summarizes the overall category proportions, revealing that the dataset is predominantly composed of small- and medium-sized targets.

- (2)

- OSPRC Dataset

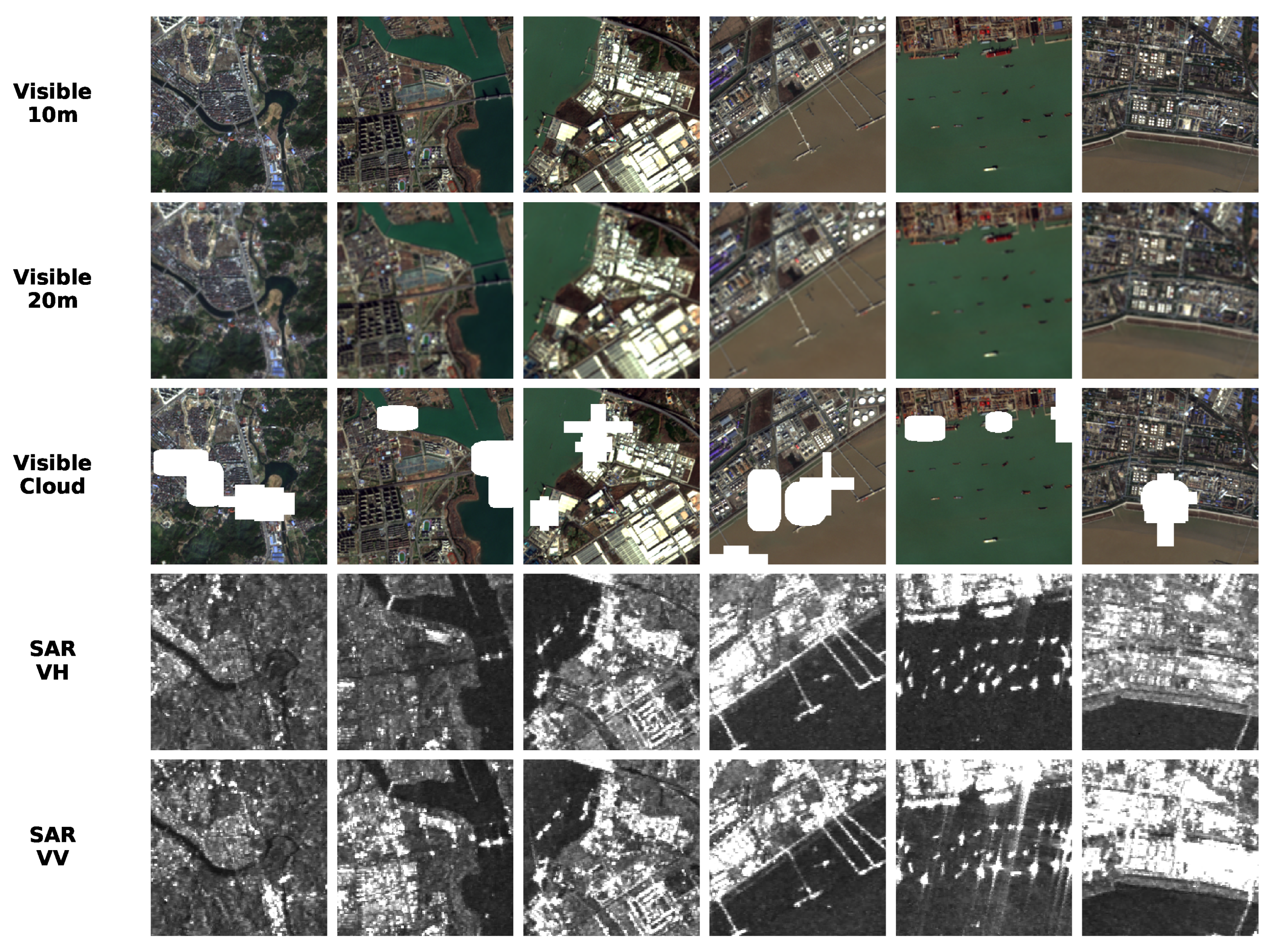

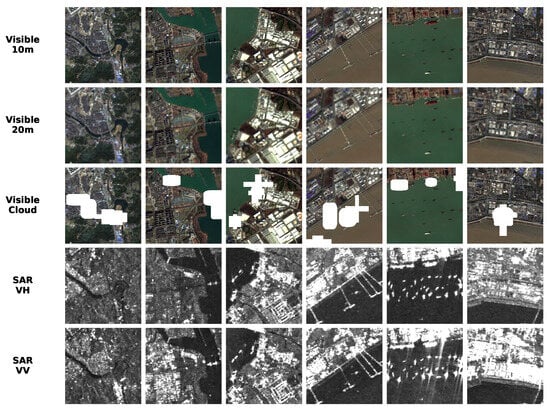

The OSPRC dataset [31] is a smaller-scale paired visible-SAR dataset designed for systematic evaluation of the effects of SAR polarization modes (VV/VH), visible resolutions (10/20 m), and cloud occlusion conditions on detection performance. It consists of five subsets, each containing 3300 paired images. All images are spatially aligned using ENVI software, and the co-registered image pairs are cropped into pixel patches. The training and testing sets are split with an 8:2 ratio. The annotated object categories are consistent with those of OGSOD, namely Bridge, Harbor, and Oil Tank, enabling a robust assessment of model generalization under cross-scene conditions. Representative examples under different imaging scenarios from OSPRC are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Representative examples in the OSPRC dataset. Each row illustrates a different remote-sensing imaging condition, including visible images at 10 m resolution, visible images at 20 m resolution, visible images affected by cloud occlusion, SAR imagery acquired in VH polarization, and SAR imagery acquired in VV polarization.

In summary, the OGSOD 1.0 and OSPRC datasets jointly cover a diverse range of imaging modes and environmental conditions, providing a solid data foundation for evaluating the stability, adaptability, and generalization capability of the proposed YOLO-CMFM across various visible-SAR imaging scenarios.

3.2. Experimental Settings

All experiments in this study were conducted on a workstation equipped with an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 GPU (24 GB) and an Intel Xeon Gold 6530 CPU. The software environment consists of Python 3.9.18, CUDA 11.8, and PyTorch 2.1. Unless otherwise specified, the input image size was set to 640 × 640, with visible images using three channels and SAR images using a single channel. The batch size was fixed at 16, and all models were trained for 400 epochs in an end-to-end manner. Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) was adopted as the optimizer, with an initial learning rate of , a momentum of 0.937, and a weight decay of .

Data augmentation strategies followed those in the default Ultralytics YOLOv11 implementation, including Mosaic and Mixup. To ensure fair comparisons, random seeds were fixed across all experiments, and identical hyperparameter configurations were applied during both training and inference.

3.3. Evaluation Metrics

To quantitatively evaluate the detection performance of different methods, this study adopts mean Average Precision () as the primary evaluation metric and conducts comprehensive evaluations under varying Intersection over Union (IoU) thresholds.

A predicted bounding box is regarded as a True Positive (TP) when its IoU with the ground truth (GT) box exceeds a given threshold t; otherwise, it is classified as a False Positive (FP). Any ground-truth object that is not detected is counted as a False Negative (FN). The IoU is defined as follows:

where and denote the predicted and ground truth bounding boxes, respectively. Precision and Recall at threshold t are computed as

For each object class i, the Average Precision is defined as the integral of the Precision-Recall Curve,

where represents the precision as a function of recall for class i. The is then obtained by averaging over all object classes:

This study employs the following two widely used evaluation metrics:

- : The computed at an IoU threshold of 0.5, reflecting the model’s detection capability under standard overlap conditions.

- :95: The evaluated across IoU thresholds from 0.5 to 0.95 (step size 0.05) offers a comprehensive and rigorous measure of localization accuracy and model robustness. The mathematical formulation is as follows:

Compared with , the :95 metric is more sensitive to localization errors and thus serves as a more rigorous measure for evaluating multimodal object detection performance.

3.4. Experimental Results and Analysis

To systematically validate the effectiveness and generalization capability of the proposed YOLO-CMFM, a comprehensive set of experiments was conducted from four perspectives: (1) performance comparison with mainstream detection methods; (2) robustness verification under different imaging conditions; (3) evaluation of performance gains across different detection frameworks; (4) ablation study of individual submodules.

All experiments were performed on the OGSOD 1.0 and OSPRC multimodal datasets. Model evaluation was performed using the and :95 metrics to comprehensively assess detection accuracy and robustness. In addition, heatmap visualizations were performed to further interpret the model’s feature learning behavior.

3.4.1. Performance Comparison with Mainstream Detection Methods

To evaluate the detection performance of the proposed YOLO-CMFM, extensive experiments were conducted on the OGSOD 1.0 dataset and compared with several mainstream detection approaches. The comparison includes three categories: (1) Classical single-modal models: Faster R-CNN [32], RT-DETR-L [33], RT-DETR-ResNet50 [33], YOLOv11n [19], YOLOv11s [19], and YOLOv11m [19]; (2) Representative multimodal detection methods: TarDAL [16], TINet [34], SuperYOLO [9], ICAFusion [12], and CFT [11]; (3) Simple fusion baselines built upon the YOLOv11s: Add (feature addition) and Multi (element-wise multiplication). The experimental results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Performance comparison of different detection methods on the OGSOD-1.0 dataset.

The results show that among single-modal detection models, the SAR modality consistently yields lower scores than the visible modality. This performance disparity indicates that the intrinsic speckle noise and sparse texture characteristics of SAR imagery hinder effective feature representation, thereby limiting detection accuracy. The overall performance of multimodal detection methods is mostly superior to that of classical single-modal models, underscoring the effectiveness and necessity of cross-modal fusion in visible-SAR remote sensing scenarios. Although the simple fusion baselines provide moderate improvements over single-modal models, their lack of alignment and feature-selection mechanisms constrains their fusion effectiveness and prevents them from fully exploiting inter-modal complementary information.

In contrast, the proposed YOLO-CMFM achieves superior performance, attaining an of 96.2% and an :95 of 75.1%, the highest among all evaluated methods. A detailed analysis of the results further highlights the accuracy and efficiency of our method. Specifically, the n, s, and m versions of YOLO-CMFM consistently exhibit improved accuracy compared to their corresponding single-modal baselines, validating the robustness of the fusion module across different model scales. In terms of parameter efficiency, YOLO-CMFM (s) maintains a parameter count comparable to ICAFusion but improves :95 by 6.7%, while YOLO-CMFM (m) achieves a substantial 12.2% increase in :95 compared to CFT under similar model complexity. Furthermore, regarding the trade-off between accuracy and efficiency, although the introduction of the CMFM incurs additional parameters and computational overhead, it yields significant gains in localization accuracy. Notably, YOLO-CMFM (m) achieves the best results across all accuracy metrics while maintaining an inference speed of 58.6 FPS. This speed is well above the standard real-time threshold of 30 FPS [36], demonstrating that our method successfully strikes an optimal balance between high-precision detection and real-time inference capability.

This substantial performance improvement is attributed to the edge-guided feature enhancement and context-aware gating mechanisms incorporated into YOLO-CMFM. The former reinforces geometric consistency between visible and SAR features by leveraging edge structures, while the latter adaptively modulates cross-modal feature weights according to semantic context, effectively reducing feature redundancy induced by modality-distribution discrepancies. Together, these mechanisms enable more efficient cross-modal feature interaction and support highly adaptive fusion.

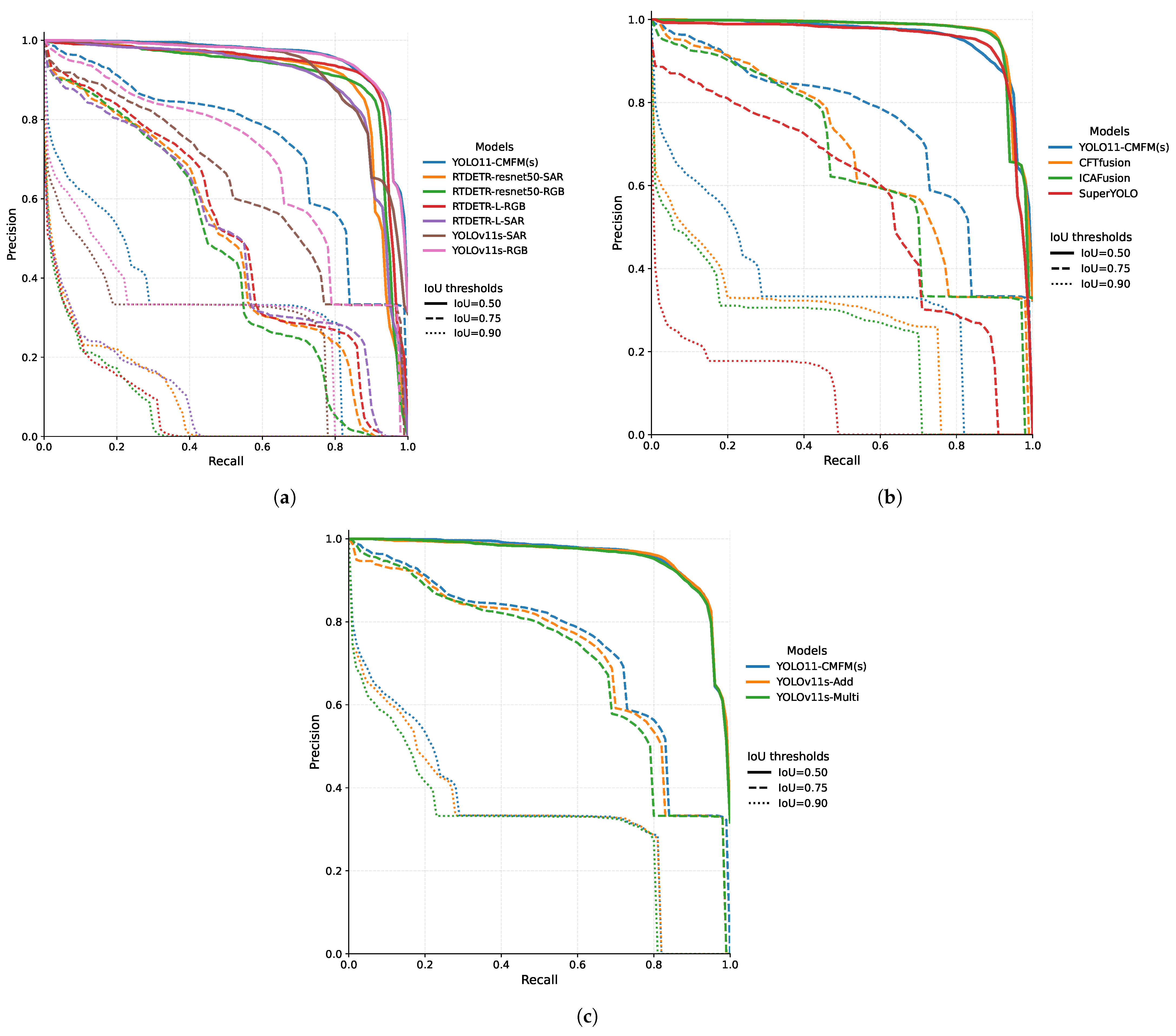

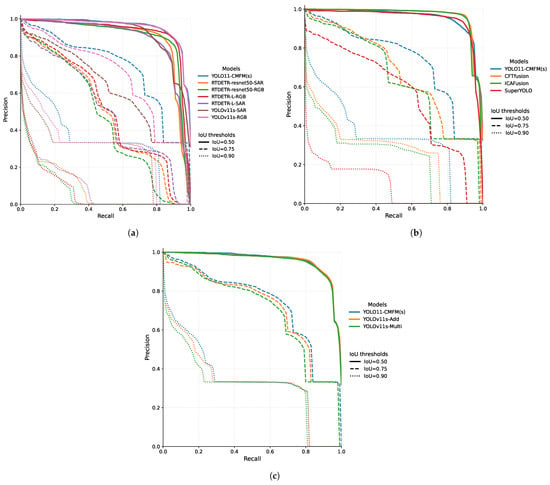

To further validate the effectiveness of YOLO-CMFM, Figure 6 presents a comparison of the Precision-Recall (PR) curves of YOLO-CMFM (s) and different methods under IoU thresholds of 0.5, 0.75, and 0.90. It is evident that under the relatively lenient IoU threshold of 0.5, all methods achieve high precision and recall. However, as the threshold becomes more stringent (IoU = 0.75 and 0.90), the PR curves of YOLO-CMFM remain noticeably smoother, exhibiting a much slower decline in performance than the other methods. Across the full recall spectrum, YOLO-CMFM consistently maintains superior precision and recall, clearly outperforming all competing models. These results suggest that YOLO-CMFM provides stronger feature correspondence and false-positive suppression under high IoU thresholds, underscoring its distinct advantages in precise object localization.

Figure 6.

PR curves of different object detectors on the OGSOD-1.0 dataset under IoU thresholds of 0.5, 0.75, and 0.90. (a) PR curves of classical single-modal detectors. (b) PR curves of representative multimodal detectors. (c) PR curves of simple fusion baselines. Across all settings, the proposed YOLO-CMFM demonstrates consistently higher precision and recall, particularly under stricter IoU thresholds (0.75 and 0.90), highlighting its capability in precise object localization.

3.4.2. Robustness Verification Under Different Imaging Conditions

To further assess the stability and generalization capability of the proposed YOLO-CMFM under varying imaging conditions, experiments were conducted on the OSPRC dataset. In these experiments, YOLOv11s served as the baseline detector for both visible and SAR single-modal inputs, while the proposed YOLO-CMFM was employed for the visible-SAR multimodal configuration. The experimental results for all settings are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Robustness evaluation of the proposed YOLO-CMFM under different imaging conditions on the OSPRC dataset.

From the overall results, YOLO-CMFM delivers substantial performance gains across all imaging conditions, demonstrating strong adaptability and generalization capability when handling multi-source and heterogeneous data. Specifically, YOLO-CMFM improves by approximately 0.8–6.3% and :95 by 2.9–4.6% over the single-modal models, indicating its effectiveness in mitigating feature degradation caused by variations in imaging resolution and polarization.

It is particularly noteworthy that in cloud-occlusion scenarios, the visible single-modal model exhibits a marked performance degradation due to severe interference from cloud layers. Its drops to 51.7%, and :95 decreases to only 23.0%, indicating substantial deterioration of visible-image features under cloudy conditions. In contrast, YOLO-CMFM leverages the structural compensation provided by SAR imagery to effectively recover geometric and textural cues, yielding improvements of 6.3 and 4.6 percentage points in and :95, respectively. These findings demonstrate that YOLO-CMFM can adaptively adjust modality weight distributions based on scene characteristics, dynamically enhancing the contribution of SAR features when the visible modality becomes degraded, thereby achieving robust cross-modal complementarity and maintaining stable detection performance.

3.4.3. Performance Gain Evaluation Across Different Detection Frameworks

To evaluate the generality and transferability of the proposed CMFM, it was integrated into several representative Ultralytics YOLO detection frameworks, including YOLOv5s [37], YOLOv6s [38], YOLOv8s [39], YOLOv9s [40], YOLOv10s [41], YOLOv11s [19], and YOLOv12s [42]. Experiments were conducted on the OGSOD 1.0 dataset. For the single-modal setting, visible and SAR inputs were processed using the original YOLO models, whereas the visible-SAR multimodal setting employed the CMFM-enhanced versions. The detection performance of all models under both single-modal and multimodal configurations is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Performance comparison of CMFM integration across different YOLO frameworks on the OGSOD-1.0 dataset.

From the overall results, the CMFM consistently delivers stable and notable performance gains across different YOLO frameworks. The improvements in range from 0.2% to 1.8%, whereas the gains in the more challenging :95 metric reach 1.6–4.9%, demonstrating the strong architectural compatibility and cross-model transferability of CMFM. Among all models, YOLOv12s-CMFM achieves the highest performance of 96.2%. YOLOv10s-CMFM attains the best :95 score of 71.8%, highlighting its superior high-precision detection capability.

From a modality perspective, the visible single-modal models generally outperform their SAR counterparts, primarily because the OGSOD 1.0 dataset contains numerous scenes rich in textures and spectral details, where visible imagery naturally provides stronger feature representation. When integrated with CMFM, the multimodal models facilitate deep cross-modal feature interaction and adaptive channel-spatial fusion, effectively enhancing complementary information and suppressing redundancy. Across different object categories, Harbor detection is nearly saturated, Bridge shows consistent improvements of 0.4–1.2%, and Oil Tank exhibits the most significant gains (0.1–4.1%), demonstrating the clear advantage of CMFM for small- and medium-sized target detection.

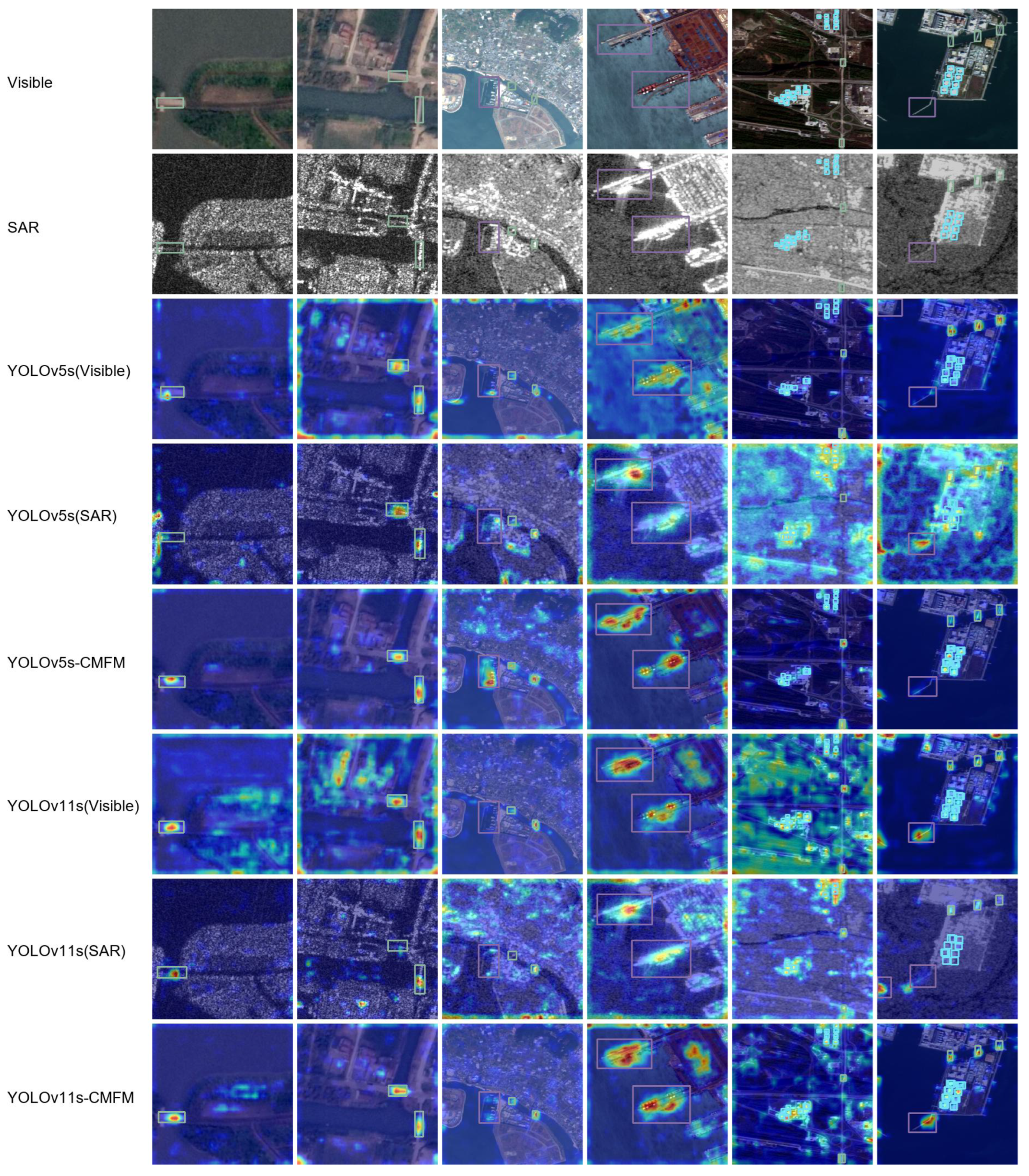

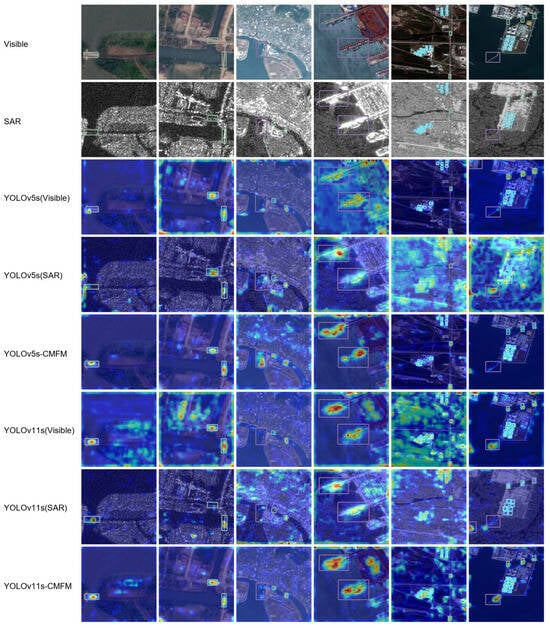

To further validate the enhanced feature representation capability provided by the CMFM, Grad-CAM-based visualizations [43] were generated to examine the attention distributions of different models. Representative examples are shown in Figure 7. The resulting heatmaps highlight the regions that the models attend to during inference, providing an intuitive assessment of their target-focus capability and background suppression performance [44].

Figure 7.

Grad-CAM visualizations of attention responses for different models, where red regions denote strong activation responses and blue regions correspond to weak responses. The visible-only models tend to exhibit diffused attention in texture-rich backgrounds, while SAR-only models produce edge-enhanced but noisy and spatially inconsistent activations. In contrast, the CMFM-enhanced multimodal models generate more concentrated and accurately aligned high-response regions around true targets, with significantly suppressed activation in irrelevant background areas. The colored bounding boxes represent the detection results of the models, with green, red, and blue boxes corresponding to the categories bridge, harbor, and oil tank, respectively.

The visible single-modal model can capture the primary region of the target. However, its attention frequently diffuses into texture-rich background regions, and noticeable attention drifts occur in certain areas. The SAR single-modal model exhibits strong responses along structural edges, but the presence of random noise and speckle results in blurred salient regions and poor boundary consistency. In contrast, the CMFM-enhanced multimodal models demonstrate markedly improved target localization. The activation responses are more concentrated, the high-response areas align closely with the actual target regions, and irrelevant background activation is substantially reduced.

Overall, the CMFM strengthens multimodal feature representation by enabling discriminative feature enhancement and semantically adaptive aggregation. These advancements substantially improve the model’s capability to identify key objects and achieve more precise spatial focus. Moreover, the consistent performance gains observed across various YOLO frameworks underscore the CMFM’s transferability and practical potential as a versatile cross-modal fusion component.

3.4.4. Ablation Study of Individual Submodules

To evaluate the independent contributions and synergistic effects of each submodule within the overall fusion mechanism, comprehensive ablation experiments were conducted on the OGSOD1.0 dataset. Using YOLOv11s-Add as the baseline model, LEGA, BCA, and CGG were incrementally introduced. The results are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Ablation study of the submodules on the OGSOD-1.0 dataset.

Overall, the major performance improvement is concentrated in the stricter :95 metric, with a gain of 1.3%, whereas the improvement in is relatively small at only 0.3%. This suggests that the baseline model is already close to saturation under the more lenient IoU threshold, while the proposed fusion mechanism primarily enhances precise object localization, thereby yielding more substantial gains under stricter matching conditions.

Regarding the individual contributions of each module, incorporating the BCA module improves :95 by approximately 0.3 percentage points, indicating that the bidirectional cross-modal interaction effectively facilitates complementary fusion between visible and SAR features at the global semantic level. Introducing the gating mechanism alone also yields a slight improvement, but when combined with contextual information, the gain expands to 1.3 percentage points. This demonstrates that global contextual cues play a critical role in modality-weight allocation, enabling the model to adaptively adjust the contributions of visible and SAR modalities based on scene semantics, thereby effectively suppressing redundant features and mitigating interference.

When the LEGA and BCA modules are jointly applied through the FiLM mechanism, the :95 improves by approximately 1.1 percentage points. This result confirms the effectiveness of edge-saliency guidance for cross-modal alignment, enabling the model to more perceive structural boundaries and salient target regions, thereby enhancing geometric consistency and discriminative feature accuracy.

When all three modules operate together, the model achieves its best overall performance, with improvements of 0.3 and 1.3 percentage points in and :95, respectively, compared with the baseline. The progressive performance gains observed with the addition of each module indicate that they collectively form a complementary hierarchy across different semantic levels. Collectively, these components constitute a progressive fusion architecture that substantially enhances detection accuracy and robustness, demonstrating that the design of the proposed YOLO-CMFM provides structural interpretability.

4. Discussion

The proposed YOLO-CMFM delivers consistent and significant performance improvements across diverse imaging conditions and various detection frameworks, underscoring its effectiveness in deep cross-modal semantic interaction and robust feature modeling.

Notably, in visually degraded scenarios such as cloud occlusion, where visible single-modal performance deteriorates sharply, YOLO-CMFM maintains high detection accuracy by leveraging SAR information, highlighting its ability to adaptively regulate modality contributions according to scene characteristics.

Moreover, the proposed YOLO-CMFM achieves superior performance under high-IoU threshold conditions compared with other detection models, demonstrating its significant advantages in precise object localization, and false-positive suppression. Grad-CAM visualizations reveal that YOLO-CMFM concentrates its attention more accurately on meaningful structural regions while effectively suppressing background clutter and SAR speckle noise, providing strong evidence for the validity of the proposed fusion mechanism.

From a mechanistic perspective, the performance gains of YOLO-CMFM arise from the synergistic interaction of its three core components. Specifically, the following apply:

- The LEGA module leverages a learnable edge-saliency prior to achieve edge-oriented cross-modal structural alignment, effectively mitigating SAR noise interference and visible boundary inconsistencies;

- The BCA module establishes deep interactions and global contextual associations within the joint semantic space of the two modalities, thereby enhancing cross-modal semantic consistency and complementarity;

- The CGG module employs global contextual cues to dynamically weight modality contributions, enabling the model to adaptively balance visible texture details and SAR structural information under varying scene conditions.

Together, these modules unify cross-modal structural alignment, deep semantic fusion, and adaptive regulation without modifying the original detection head or training paradigm, thereby providing an interpretable and transferable fusion framework for visible-SAR multimodal object detection.

Despite these advantages, we acknowledge the trade-off between accuracy and model complexity. As analyzed in Section 3.4, the proposed YOLO-CMFM increases the parameter count and computational overhead compared to the single-modal baseline. Although a larger single-modal model (e.g., YOLOv11m) may achieve comparable performance in favorable visible conditions due to increased parameters, it lacks the inherent robustness required for complex multimodal scenarios (e.g., night-time or cloud-occluded scenes). Therefore, the proposed YOLO-CMFM successfully strikes a balance, providing significant gains in localization accuracy and environmental adaptability while maintaining real-time inference capability.

In future work, further studies will be conducted to validate the effectiveness of YOLO-CMFM across different modality combinations (e.g., infrared, LiDAR, and hyperspectral data) and to investigate its scalability with an increased number of input modalities, assessing its generalization capability in more complex multimodal remote sensing scenarios. Furthermore, addressing the parameter overhead discussed above, we aim to explore lightweight design strategies to further reduce the computational cost of multimodal detectors, enabling a stricter comparison with baselines at the same parameter scale.

5. Conclusions

Due to the substantial differences in imaging mechanisms, noise statistics, and semantic representations between visible and SAR imagery, cross-modal feature alignment becomes challenging and information fusion is often suboptimal. To address these challenges, this paper proposes a multimodal remote sensing object detection method, namely YOLO-CMFM.

Built upon the Ultralytics YOLOv11 framework, the proposed YOLO-CMFM constructs a novel CMFM to accomplish multimodal feature fusion, which comprises an LEGA module, a BCA module, and a CGG module. It adopts a progressive fusion strategy of edge perception, contextual interaction and gated modulation, which greatly helps to enhance the detection performance with respect to structural consistency, semantic complementarity and fusion adaptivity.

Experimental results on multimodal remote sensing datasets, including OGSOD 1.0 and OSPRC, demonstrate that while the proposed YOLO-CMFM maintains competitive detection accuracy comparable to mainstream methods at lower IoU thresholds, it yields substantial performance gains at higher IoU thresholds, highlighting its superior capability in precise object localization. Moreover, despite the additional complexity introduced by the fusion module, the proposed method strikes a balance between high-precision detection and real-time inference capability.

Furthermore, the proposed CMFM can be flexibly embedded into various object detection frameworks, and YOLO-CMFM consistently delivers stable performance gains across varying resolutions, polarization modes, and cloud-occlusion conditions, which also validates its strong transferability, robustness and environmental adaptability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Z. and X.Z.; methodology, X.Z.; software, X.Z.; validation, L.Z., K.S. and R.R.; formal analysis, X.Z.; investigation, L.Z. and X.Z.; resources, L.Z.; data curation, X.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, X.Z.; writing—review and editing, L.Z.; visualization, X.Z.; supervision, L.Z. and Z.Z.; project administration, L.Z. and Z.Z.; funding acquisition, L.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Civil Aerospace Technology Pre-research Project with grant number D040404.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used in this study include the OGSOD 1.0 dataset and the OSPRC dataset. Both datasets are publicly available and can be accessed at https://github.com/mmic-lcl/Datasets-and-benchmark-code. All datasets were accessed on 20 February 2025.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, K.; Wan, G.; Cheng, G.; Meng, L.; Han, J. Object detection in optical remote sensing images: A survey and a new benchmark. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 159, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Yang, J.; Zhu, D.; Liu, J.; Guo, H.; Bayartungalag, B.; Li, B. Integrating multitemporal Sentinel-1/2 data for coastal land cover classification using a multibranch convolutional neural network: A case of the Yellow River Delta. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Shen, H.; Weng, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Dou, P.; Zhang, L. Cloud and cloud shadow detection for optical satellite imagery: Features, algorithms, validation, and prospects. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2022, 188, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alparone, L.; Arienzo, A.; Lombardini, F. Improved Coherent Processing of Synthetic Aperture Radar Data through Speckle Whitening of Single-Look Complex Images. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Xu, Y.; Qian, L.; Shi, W.; Zhang, Y.; Bao, W.; Wang, N.; Liu, X.; Xiang, X. A bridge neural network-based optical-SAR image joint intelligent interpretation framework. Space Sci. Technol. 2021, 2021, 9841456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hong, D.; Gao, L.; Yao, J.; Zheng, K.; Zhang, B.; Chanussot, J. Deep learning in multimodal remote sensing data fusion: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 112, 102926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Tian, Y.; Lu, W.; Wang, P.; Niu, R.; Yu, H.; Fu, K. From single-to multi-modal remote sensing imagery interpretation: A survey and taxonomy. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2023, 66, 140301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Dhanaraj, M.; Karnam, S.; Chachlakis, D.G.; Ptucha, R.; Markopoulos, P.P.; Saber, E. YOLOrs: Object detection in multimodal remote sensing imagery. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2020, 14, 1497–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lei, J.; Xie, W.; Fang, Z.; Li, Y.; Du, Q. SuperYOLO: Super resolution assisted object detection in multimodal remote sensing imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Qingyun, F.; Dapeng, H.; Zhaokui, W. Cross-modality fusion transformer for multispectral object detection. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.00273. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zuo, X.; Fan, H.; Yang, W. ICAFusion: Iterative cross-attention guided feature fusion for multispectral object detection. Pattern Recognit. 2024, 145, 109913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Sun, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, N. Mmyfnet: Multi-modality yolo fusion network for object detection in remote sensing images. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, X.; Guo, M.; Li, Y.; Yu, R.; Sun, L. ACDF-YOLO: Attentive and cross-differential fusion network for multimodal remote sensing object detection. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Su, N.; Zhao, C.; Yan, Y.; Feng, S. Multi-modal object detection method based on dual-branch asymmetric attention backbone and feature fusion pyramid network. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Fan, X.; Huang, Z.; Wu, G.; Liu, R.; Zhong, W.; Luo, Z. Target-aware dual adversarial learning and a multi-scenario multi-modality benchmark to fuse infrared and visible for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 5802–5811. [Google Scholar]

- Razakarivony, S.; Jurie, F. Vehicle detection in aerial imagery: A small target detection benchmark. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2016, 34, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Cao, B.; Zhu, P.; Hu, Q. Drone-based RGB-infrared cross-modality vehicle detection via uncertainty-aware learning. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2022, 32, 6700–6713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanam, R.; Hussain, M. Yolov11: An overview of the key architectural enhancements. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.17725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, D.; Lu, R.; Fang, Y.; Lang, X.; Shu, S.; Chen, J.; Shen, S.; Xu, T.; Ye, Z. YOLOv11-RGBT: Towards a Comprehensive Single-Stage Multispectral Object Detection Framework. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.14696. [Google Scholar]

- He, L.H.; Zhou, Y.Z.; Liu, L.; Cao, W.; Ma, J.H. Research on object detection and recognition in remote sensing images based on YOLOv11. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Ye, S.; Zhao, S.; Wang, W.; Xie, C. Pear object detection in complex orchard environment based on improved YOLO11. Symmetry 2025, 17, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Chen, S.B.; Li, H.D.; Shu, Q.L.; Ding, C.H.; Tang, J.; Luo, B. Legnet: Lightweight edge-Gaussian driven network for low-quality remote sensing image object detection. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.14012. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Q.; Cheng, M.M.; Hu, X.; Borji, A.; Tu, Z.; Torr, P.H. Deeply supervised salient object detection with short connections. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 3203–3212. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.X.; Liu, J.J.; Fan, D.P.; Cao, Y.; Yang, J.; Cheng, M.M. EGNet: Edge guidance network for salient object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 8779–8788. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Perez, E.; Strub, F.; De Vries, H.; Dumoulin, V.; Courville, A. Film: Visual reasoning with a general conditioning layer. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–7 February 2018; pp. 3942–3951. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, Z.; Lang, F.; Shi, H.; Zheng, N. CFFormer: A Cross-Fusion Transformer Framework for the Semantic Segmentation of Multi-Source Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Li, Y.; Bengio, S.; Si, S. Gaternet: Dynamic filter selection in convolutional neural network via a dedicated global gating network. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1811.112. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, J.H.; Kim, Y.; Kim, J.; Choi, J.W. 3D-CVF: Generating joint camera and lidar features using cross-view spatial feature fusion for 3D object detection. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2020; pp. 720–736. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Ruan, R.; Zhao, Z.; Li, C.; Tang, J. Category-oriented localization distillation for sar object detection and a unified benchmark. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2016, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Lv, W.; Xu, S.; Wei, J.; Wang, G.; Dang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J. Detrs beat yolos on real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024; pp. 16965–16974. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, H.; He, Y.; Wang, X.; Yang, W. Illumination-guided RGBT object detection with inter-and intra-modality fusion. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, R.; Yang, K.; Zhao, Z.; Li, C.; Tang, J. OGSOD-2.0: A challenging multimodal benchmark for optical-SAR object detection. In Proceedings of the Sixteenth International Conference on Graphics and Image Processing (ICGIP 2024), Nanjing, China, 8–10 November 2024; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2025; Volume 13539, pp. 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Jocher, G.; Stoken, A.; Borovec, J.; Changyu, L.; Hogan, A.; Diaconu, L.; Poznanski, J.; Yu, L.; Rai, P.; Ferriday, R.; et al. ultralytics/yolov5. v3.0. Available online: https://github.com/ultralytics/yolov5/releases/tag/v3.0 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Li, C.; Li, L.; Jiang, H.; Weng, K.; Geng, Y.; Li, L.; Ke, Z.; Li, Q.; Cheng, M.; Nie, W.; et al. YOLOv6: A single-stage object detection framework for industrial applications. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.02976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohan, M.; Sai Ram, T.; Rami Reddy, C.V. A review on yolov8 and its advancements. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Data Intelligence and Cognitive Informatics, Tirunelveli, India, 18–20 November 2024; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2024; pp. 529–545. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.Y.; Yeh, I.H.; Liao, H.Y.M. Yolov9: Learning what you want to learn using programmable gradient information. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2024; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, K.; Lin, Z.; Han, J.; Ding, G. Yolov10: Real-time end-to-end object detection. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 107984–108011. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Ye, Q.; Doermann, D. Yolov12: Attention-centric real-time object detectors. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.12524. [Google Scholar]

- Selvaraju, R.R.; Cogswell, M.; Das, A.; Vedantam, R.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Grad-cam: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 618–626. [Google Scholar]

- Hassanin, M.; Anwar, S.; Radwan, I.; Khan, F.S.; Mian, A. Visual attention methods in deep learning: An in-depth survey. Inf. Fusion 2024, 108, 102417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.