Highlights

What are the main findings?

- The proposed DLANet introduces a dual-level attention relearning mechanism (IF2M + ABFW) that moves beyond simple feature addition, achieving a 9.6–12.7% performance gain by actively suppressing modality-specific noise (such as thermal ghosts) while preserving fine-grained complementary details.

- To address the scarcity of land-based multimodal inspection data, a dedicated OilLeak dataset is constructed, coupled with a novel coarse-to-fine registration strategy that effectively resolves spatial misalignments in coaxial UAV imagery.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- A critical synergistic mechanism is established. While the Implicit Fine-Grained Fusion Module (IF2M) captures deep semantic interactions, the Adaptive Branch Feature Weighting (ABFW) acts as a dynamic gatekeeper, ensuring robustness against environmental extremes (e.g., occlusion, low light), where single-modality methods fail.

- The framework challenges the trend of heavy Transformer-based fusion by achieving state-of-the-art accuracy with the fewest parameters (39.04 M) and a low computational cost of 72.69 GFLOPs among compared methods, demonstrating that lightweight, rotation-aware CNNs are the optimal solution for real-time edge deployment in resource-constrained UAV operations.

Abstract

Effectively leveraging multi-source unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) observations for reliable object recognition is often compromised by environmental extremes (e.g., occlusion and low illumination) and the inherent physical discrepancies between modalities. To overcome these limitations, we propose DLANet, a lightweight, rotation-aware multimodal object detection framework that introduces a dual-level attention relearning strategy to maximize complementary information from visible (RGB) and thermal infrared (TIR) imagery. DLANet integrates two novel components: the Implicit Fine-Grained Fusion Module (IF2M), which facilitates deep cross-modal interaction by jointly modeling channel and spatial dependencies at intermediate stages, and the Adaptive Branch Feature Weighting (ABFW) module, which dynamically recalibrates modality contributions at higher levels to suppress noise and pseudo-targets. This synergistic approach allows the network to relearn feature importance based on real-time scene conditions. To support industrial applications, we construct the OilLeak dataset, a dedicated benchmark for onshore oil-spill detection. The experimental results demonstrate that DLANet achieves state-of-the-art performance, recording an mAP0.5 of 0.858 on the public DroneVehicle dataset while maintaining high efficiency, with 39.04 M parameters and 72.69 GFLOPs, making it suitable for real-time edge deployment.

1. Introduction

Unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV)-based object detection has emerged as a crucial element in modern remote sensing, supporting essential tasks such as environmental monitoring, disaster assessment, and military reconnaissance [1,2]. While early research relied on optical imagery due to its rich texture and spectral data [3,4,5], attention has shifted toward exploiting multimodal payloads, specifically the combination of RGB and thermal infrared (TIR) imagery, to handle challenging conditions like low illumination, haze, and occlusion [6]. However, effectively leveraging these heterogeneous sensors remains challenging due to inherent discrepancies. For example, optical images are susceptible to atmospheric variations, while TIR images suffer from low spatial resolution, weak edges, and noise [7,8]. These inconsistencies often lead to redundant or misleading cues during feature fusion, making the extraction of reliable complementary information a central challenge in the field [9,10,11].

Current detection frameworks can be categorized into single-modality approaches, general multimodal fusion strategies, and attention/Transformer-based mechanisms. Single-modality frameworks include detectors migrated from natural image analysis (YOLO [12], SSD [13]) and rotation-aware models (R3Det [14], Oriented Faster R-CNN [15]) that utilize geometric alignment. They provide efficient solutions and have seen rapid progress through benchmark datasets [16,17,18]. However, they inherently lack thermal cues, leading to struggles in adverse environmental conditions where optical data is insufficient.

Multimodal fusion strategies are divided into early, mid-level, and late fusion [19]. Mid-level fusion is considered the most effective as it retains discriminative semantics [20,21,22]. Specific innovations include uncertainty-aware frameworks to mitigate optimization bias (e.g., UA-CMDet [23]), cross-modal attention for feature enhancement (e.g., YOLOFusion [22]), and entropy-based redundancy suppression (e.g., RISNet [24]). Unlike conventional CNN-based methods, RISNet computes the information entropy of RGB and infrared feature maps during the feature extraction stage and uses this entropy to optimize network parameters. Mid-level fusion allows for modality-specific feature preservation before interaction. However, early fusion is vulnerable to misalignment [19], while late fusion introduces high parameter overhead [25,26]. Furthermore, many mid-level strategies rely on heuristic rules and fail to balance the preservation of semantics with the suppression of degraded modality information.

Recent studies have utilized Transformers and attention models (e.g., CFT [27], M2FNet [28]) to capture long-range dependencies and enhance multi-scale reasoning. Some approaches [29] have integrated super-resolution auxiliary branches to aid small-object detection. These methods effectively strengthen cross-modal interaction and fusion quality. In parallel, efficient sequence modeling architectures, such as Mamba-based frameworks, have been explored as alternatives to Transformers to reduce computational complexity while retaining long-range dependency modeling capability. Representative methods (e.g., DMM [30]) demonstrate promising performance on public UAV benchmarks by leveraging linear-complexity state-space models for cross-modal fusion.

Nevertheless, Transformer- and Mamba-based designs often introduce additional architectural complexity or auxiliary optimization tasks, which may still hinder real-time deployment on lightweight UAV platforms and reduce robustness in dynamically changing scenes.

Despite advancements, current frameworks face persistent limitations: (1) fusion remains sensitive to spatial inconsistency; (2) TIR degradation (noise/blur) often contaminates fused representations; (3) many schemes lack adaptivity, treating unreliable modalities with equal importance; and (4) heavy computational costs hinder real-time utility.

To address these gaps, we propose DLANet, a lightweight and rotation-aware multimodal detection framework designed to maximize complementary semantics while suppressing unreliable data. The key innovations include the following:

- (1)

- The introduction of an Implicit Fine-Grained Fusion Module (IF2M) to model channel–spatial dependencies and an Adaptive Branch Feature Weighting (ABFW) module to dynamically regulate modality contributions based on scene conditions.

- (2)

- An efficient coarse–fine multimodal alignment strategy to ensure reliable feature correspondence.

- (3)

- The construction of the “OilLeak” dataset to support research in UAV-based RGB–TIR detection for petroleum-leak monitoring.

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Data

2.1.1. DroneVehicle Dataset

The DroneVehicle dataset [23] is a publicly available benchmark designed for multimodal remote sensing object detection. It contains 28,439 pairs of RGB–thermal infrared images, all focusing on the “vehicle” category as the primary target class. The dataset was collected using a DJI M200 UAV equipped with a Zenmuse XT2 gimbal camera (Da-Jiang Innovations Science and Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) and includes representative ground scenes, such as urban roads, residential areas, parking lots, and highways. The data were captured under various lighting conditions, including daytime, evening, and nighttime. Flight altitudes were set at 80 m, 100 m, and 120 m, with nadir angles of 0°, 15°, 35°, and 45°. Since the dataset authors performed image preprocessing—such as affine transformation and region cropping—during dataset construction to ensure accurate spatial alignment between the two sensor modalities, no additional registration was required in subsequent tests.

2.1.2. OilLeak Dataset

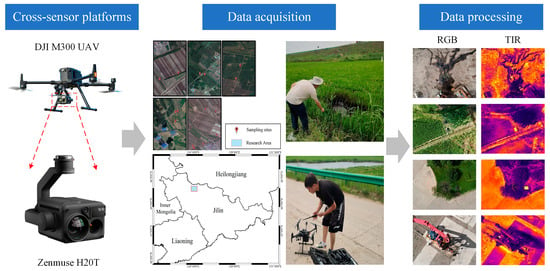

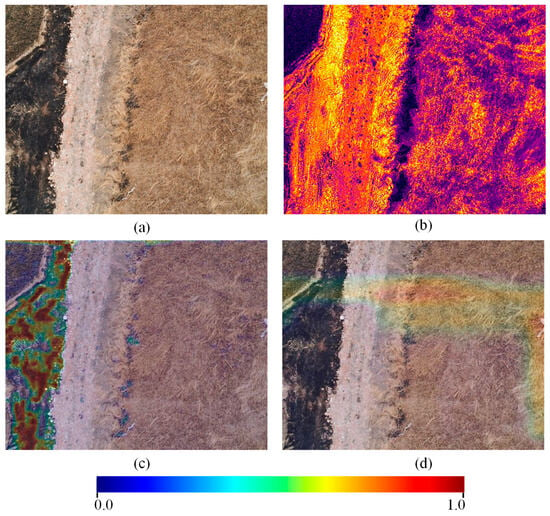

The OilLeak dataset was collected using a UAV platform (Da-Jiang Innovations Science and Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) equipped with a thermal infrared camera operating in the long-wave infrared (LWIR) band, capturing surface temperature characteristics (Figure 1). During daytime, due to oil’s high solar absorption capacity, its surface temperature rises significantly, exhibiting a temperature difference of approximately 3–8 K compared to the surrounding environment [31]. This allows spilled oil to re-radiate thermal energy in the LWIR band, resulting in prominent thermal contrast in infrared imagery. In RGB images, oil spills typically appear as dark brown or black regions. However, the presence of ground elements such as shadows and water bodies with similar visual characteristics can increase the false-alarm rate when detection relies solely on single-modal features. Publicly available UAV-based oil-spill detection datasets remain scarce. Thomas et al. [32] released an RGB single-modal image dataset targeting oil-spill detection in port and marine environments; however, datasets focusing on land-based scenarios with both RGB and thermal infrared modalities are still lacking.

Figure 1.

UAV-based cross-sensor remote sensing photogrammetry for the OilLeak dataset.

To address this gap, we collected multimodal remote sensing imagery in real-world, land-based oil-spill scenarios in the western region of Jilin Province, China, using a DJI M300 UAV equipped with a Zenmuse H20T gimbal system (Da-Jiang Innovations Science and Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China). The UAV operated at flight altitudes ranging from 30 to 100 m, with the camera primarily oriented in a nadir (0°) view. All data were captured during daylight hours. The two RGB imaging sensors are based on CMOS architecture and provide high-resolution visible-light images. The thermal infrared imaging module employs an uncooled vanadium oxide (VOx) microbolometer, capable of producing three-channel, 8-bit RJPEG images [33]. The original RGB images were captured by the wide-angle camera of the Zenmuse H20T gimbal, with a resolution of 4050 × 3040 pixels. The TIR images have a resolution of 640 × 512 pixels. Due to the significant differences in resolution and field of view between the two modalities, thermal infrared images were used as the reference for image registration. Data alignment was performed following the preprocessing procedure described in Section 2.2. In total, the dataset contains 2642 pairs of RGB and TIR images, of which 308 pairs depict oil-spill targets, accounting for 11.6% of the total images.

2.1.3. Data Preparation and Statistical Overview

To ensure the objectivity and fairness of experimental comparisons, this study randomly sampled images from the OilLeak dataset, using a fixed random seed to guarantee the reproducibility of the experiments. For the DroneVehicle dataset [23], the original authors have already divided the data into training, validation, and test sets, with a ratio of 12:1:2. For the OilLeak dataset, the division ratio is set to 4:1:1. Detailed statistics of the datasets used in this study are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Basic statistics of the DroneVehicle and OilLeak datasets used in this study.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Overview

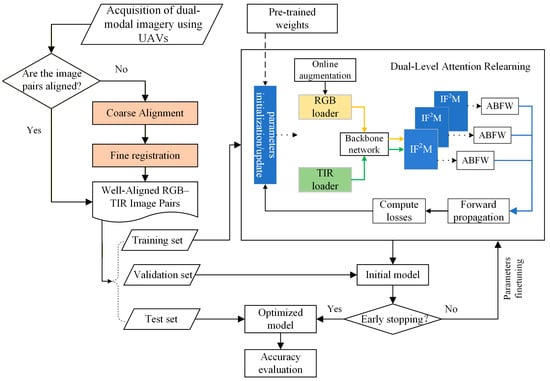

The framework is presented in Figure 2. The pipeline begins with image acquisition and a conditional alignment check; if the sensor data are not pre-aligned, they undergo a multi-stage registration process involving geometric optics-based coarse alignment and fine registration to generate well-aligned RGB–TIR image pairs. These aligned datasets are partitioned into training, validation, and testing subsets to support the core “Dual-Level Attention Relearning” phase. Within this training loop, the architecture utilizes pre-trained weights to initialize a Siamese-style backbone that extracts features from both RGB and TIR loaders. These features are processed through the Implicit Fine-Grained Fusion Module (IF2M) to model channel–spatial dependencies and subsequently fused via the Adaptive Branch Feature Weighting (ABFW) module. The IF2M and ABFW modules are incorporated at three feature scales (R3–R5), allowing the network to adaptively modulate modal contributions with respect to target scale and to perform detection using fused multi-resolution features. The framework employs an iterative optimization strategy where forward propagation and loss computation drive parameter updates, governed by an early stopping mechanism to yield an optimized model for final accuracy evaluation on the test set.

Figure 2.

Methodology for UAV-based RGB–TIR cross-modality rotated object detection via dual-level attention relearning.

2.2.2. Cross-Modality UAV Image Registration

- (1)

- Geometric Optics-Based Coarse Alignment of TIR and RGB Images

Due to the significant differences in resolution and field of view between the TIR and RGB cameras mounted on UAVs, the ground coverage captured by the two sensors often exhibits spatial misalignment. Direct application of traditional feature-based image registration methods typically produces numerous mismatched keypoints, resulting in geometric distortions in the registration outcome and severely degrading the performance of subsequent multimodal fusion.

To overcome this issue, we exploit the fixed relative positions of dual sensors on coaxial multi-payload remote sensing platforms and propose a coarse registration method based on the view transformation relationship between image pairs. This method estimates the geometric transformation between a single image pair to achieve coarse alignment, which effectively reduces the search space for fine registration, mitigates the impact of rotational discrepancies, and substantially improves the accuracy and efficiency of the overall registration process.

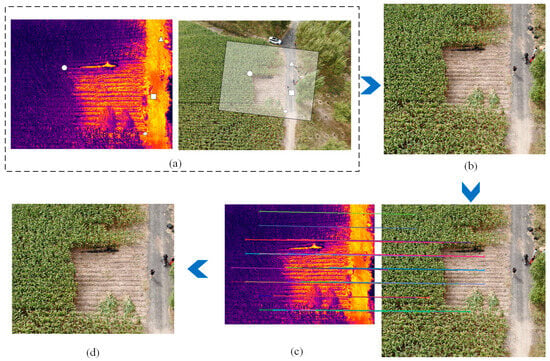

Scale factor estimation between modalities: Because of focal length differences between the TIR and RGB sensors, the same object in a scene appears at different scales in the respective image modalities (Figure 3a). In addition, due to a vertical (Y-axis) optical center offset in the hardware system, the size inconsistency cannot be fully corrected by simply scaling the images with the focal length ratio. To address this, we first compute a scaling factor to unify the high-resolution RGB images to the scale of the TIR images, as follows:

where n denotes the number of the corresponding point pairs in the RGB–TIR image pair and and represent the horizontal pixel coordinates of the i-th corresponding point in the TIR and RGB images, respectively.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of the cross-modal UAV image registration process. (a) Example of a TIR–RGB image pair acquired by UAV. The white circle, triangle, rectangle, and diamond indicate illustrative corresponding points between the two modalities. The large semi-transparent region shows the approximate extent of the TIR within the RGB frame. (b) RGB after coarse alignment. (c) TWMM-based fine registration process, where differently colored lines represent connections between corresponding points during image registration. (d) RGB accurately co-registered with the TIR.

Offset coefficient estimation: After scaling according to Equation (1), the pixel offsets of corresponding points are then calculated in the following form:

where and denote the horizontal pixel coordinates of the i-th corresponding point in the TIR and RGB images after applying the scaling factor, respectively. and denote the vertical pixel coordinates of the i-th corresponding point in the TIR and RGB images after scaling. and represent the average horizontal and vertical offsets between the TIR and RGB images, respectively. Finally, the coarsely registered TIR and RGB images (Figure 3b) are obtained as follows:

where denotes the original RGB image and , , and represent the RGB image and corresponding points after affine transformation, respectively.

- (2)

- Fine registration based on hierarchical feature template matching

The UAV gimbal camera system cannot guarantee strict synchronous triggering between the TIR and RGB sensors during image acquisition. Moreover, the two camera types exhibit varying degrees of geometric distortions, resulting in a slight viewpoint offset between the TIR and RGB images, manifested as a small rotational error θ. Building upon the coarse registration, we employ a hierarchical feature-based template matching method, TWMM [34], for fine registration to achieve pixel-level alignment of TIR–RGB image pairs. As shown in Figure 3c, TWMM utilizes a similarity map aggregation strategy, which enhances the robustness of corresponding point matching between images and significantly improves localization accuracy. It effectively overcomes the low repeatability of keypoints in traditional feature matching methods and the large localization errors common in conventional template matching approaches, thereby ensuring high-precision multimodal registration.

2.3. The Architecture of the Cross-Modality Network

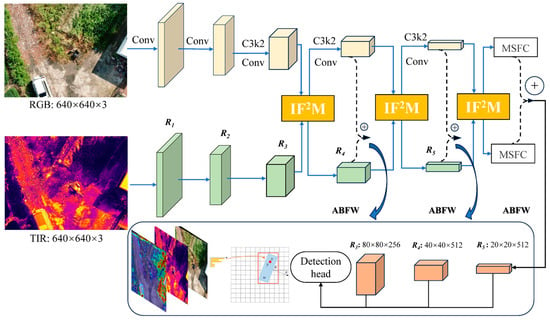

As illustrated in Figure 4, we propose an end-to-end cross-modal rotated object detection network for UAV platforms, referred to as the DLANet architecture (see the Appendix A). The network comprises four main components: an RGB feature extraction backbone, a TIR feature extraction backbone, a dual-level attention relearning module, and a rotated detection head. The design of the rotated detection head is inspired by YOLOv11 [35]. Notably, the TIR feature extraction backbone shares the same architecture as the RGB backbone, forming a Siamese network structure that enables symmetric extraction of multimodal features.

Figure 4.

Overview of the cross-modality network architecture of DLANet. The red boxes in the figure indicate the regression outputs of the detection head, where the final fused multi-scale features are used to predict the target center coordinates and rotation angle. The “+” symbol in the circles denotes feature addition.

Backbone Network: In this study, feature maps at five scales {R1, R2, R3, R4, R5} are employed for cascaded feature extraction, with spatial resolutions of relative to the original input size. The backbone adopts a pyramid-style hierarchical design, which effectively enhances the network’s ability to adapt to objects of varying scales and mitigates the limitation of local perception—commonly described as “seeing the trees but not the forest.” Compared with the HRNet-CFR architecture proposed in previous work [36], the proposed design omits the complex multi-resolution recursive connection strategy, significantly reducing computational cost while maintaining detection performance. This improvement enhances model compactness and deployment efficiency. Similarly, the TIR feature extraction backbone adopts a symmetric structure to ensure consistency in cross-modal feature extraction.

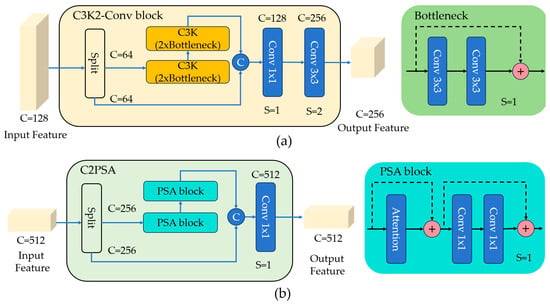

Figure 5 illustrates the key components, C3K2-Conv Block and C2PSA, within the network architecture. The C3K2-Conv Block draws inspiration from the integration of the C3K2 feature extraction unit and convolutional structure of YOLOv11 [35]. It is designed to further refine the extracted features while enabling effective spatial down-sampling. The Multi-Scale Feature Cascade (MSFC) module is constructed by sequentially connecting the Spatial Pyramid Pooling Fast (SPPF) module [37] and the Cross Stage Partial with Spatial Attention (C2PSA) module [38]. The SPPF module introduces contextual information through multi-scale feature map pooling. CSPSA combines cross stage partial connections with position-sensitive self-attention for efficient global context modeling. The attention branch processes 256 hidden channels using two stacked PSA (Partial with Spatial Attention) blocks, each configured with four attention heads, striking a balance between representation capability and computational efficiency.

Figure 5.

The architecture of key components. (a) The C3K2-Conv block with R3 scale. (b) The C2PSA module with R5 scale. C denotes the number of feature-map channels, and S denotes the stride. The “+” symbol in the circles denotes feature addition, while “C” denotes feature concatenation.

2.4. Dual-Level Attention Relearning Mechanism

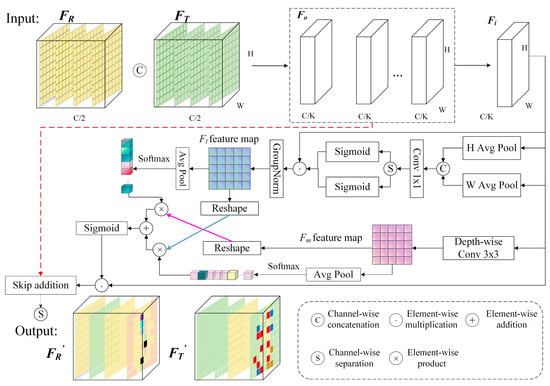

2.4.1. Implicit Fine-Grained Feature Module (IF2M)

Directly modeling cross-modal or cross-channel relationships using simple channel concatenation and feature stacking may overlook complex dependencies between channel dimensions and spatial locations, which can compromise the representation capacity of deep visual features.

Inspired by the CBAM [39] attention mechanism, we designed the IF2M to partition the input features into multiple sub-feature groups, enabling each subgroup to learn independent attention patterns. Going beyond CBAM [39], which applies coarse spatial and channel attention on single-modality features, IF2M encodes spatial dependencies along both vertical and horizontal directions and performs cross-modal fusion. At this interactive fusion stage, each branch has implicitly incorporated contextual information from the other modality: the RGB features embed thermal radiation cues from the TIR modality, while the TIR features acquire texture and structural details from the RGB modality. This implicit cross-modal interaction preserves the representational independence of each modality while effectively reducing the semantic gap between them.

We illustrate the structure of the IF2M in Figure 6, taking the first fusion at scale R3 as an example to explain the details.

Figure 6.

Structure of the IF2M at the first stage of fusion.

- (1)

- Sub-feature Group Partitioning

The features output from the RGB and TIR branches at this scale are denoted as FR and FT, respectively. These features are concatenated along the channel dimension to form the fused feature Fo, which serves as the input to the IF2M. To introduce fine-grained attention mechanisms without significantly increasing the model’s parameters, Fo is divided along the channel dimension into K sub-feature groups:

where C denotes the number of input channels after concatenation and H and W represent the spatial dimensions of the input feature map. The index i corresponds to the i-th sub-feature group. The number of groups, K, is set to be approximately proportional to , which is sufficient to preserve semantic consistency while avoiding excessive cross-channel redundancy. Restricting K to powers of two further ensures channel divisibility. For instance, in the first IF2M operation at the R3 scale, the input feature map has spatial dimensions H = W = 80 and a channel dimension C = 512. K is determined by Equation (6) to be 16.

This grouping strategy not only reduces computational overhead but also enables each subgroup to learn relatively independent attention patterns across different spatial regions, thereby enhancing both the diversity and representational capacity of the cross-modal fused features.

- (2)

- Enhanced Directional Spatial Attention

To capture long-range dependencies along the spatial dimensions, two one-dimensional global average pooling operations are applied to each sub-feature group, encoding the feature maps along the vertical and horizontal directions to generate directional branches. This mechanism effectively captures the latent semantic and structural correlations between spatial locations in the image, particularly those that are far apart, which are often difficult to model using conventional local convolution operations. Specifically, this process can be regarded as global modeling of positional information along the vertical and horizontal directions:

where fc denotes the c-th channel of the input feature Fo, while and represent the spatially pooled features of the c-th channel along the vertical and horizontal directions, respectively.

Subsequently, we concatenate the two directionally encoded feature vectors along the vertical dimension and jointly process them through a shared 1 × 1 convolutional branch, as expressed in Equation (9). It effectively fuses features from different directions and learns the coupling relationship between RGB and TIR across directions through the shared convolution kernel. The output of the 1 × 1 convolution, denoted as , is then decomposed into two one-dimensional vectors, and , along the vertical and horizontal dimensions, respectively. Two independent Sigmoid functions, , are applied to normalize these vectors, yielding the attention weights along the vertical and horizontal directions.

The original feature Fi is sequentially multiplied by the vertical and horizontal attention weights, and , enabling spatially guided enhancement along both directions. This process allows for fine-grained recalibration of inter-channel importance relationships. The enhanced feature is subsequently normalized using group normalization (GN) to produce the local-level fused feature Fl, as described in Equation (11).

- (3)

- Cross-Branch Attention Modeling

Simultaneously, the original grouped feature is fed into a parallel global branch, where global contextual information, Fm, is further extracted using a 3 × 3 depthwise separable convolution. The two resulting spatial attention maps are derived from the respective feature maps of the main and global branches, capturing spatial distributions from different perspectives. Specifically, the first attention map reflects the spatial activation intensity of the backbone feature Fi, whereas the second, derived from the context-enhanced branch Fm, supplements information across broader spatial ranges. Both branches are subjected to 2D global average pooling, followed by Softmax normalization, to generate channel attention vectors as described below:

The feature maps Fl and Fm are then flattened into vector representations , which are thereafter used to compute cross-attention with the corresponding channel attention vectors wl and wm. The final attention weight, , is obtained by applying a Sigmoid activation function, as expressed below:

where FM is obtained from IF2M by performing a residual addition of the cross-attention fused features with the original input feature map Fo. This preserves the backbone features while enhancing their spatial–channel responses and mitigating the risk of overfitting introduced by IF2M.

Finally, a channel-wise split operation is applied to the fused feature FM, generating the updated features and , which are subsequently used for further computation within their respective network branches. By employing a cross-guided mechanism, the model dynamically and selectively integrates multi-scale spatial contextual information, effectively improving the consistency of feature representations across local–global levels and channels.

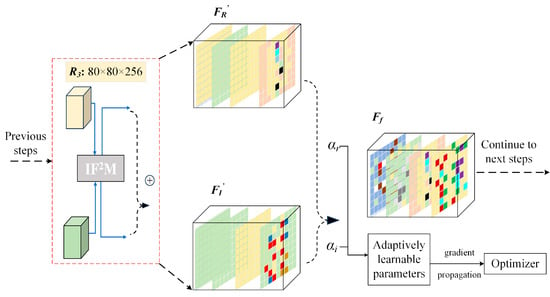

2.4.2. The ABFW Module

The proposed IF2M module facilitates fine-grained interaction between RGB and TIR feature branches, enabling mutual learning and complementary enhancement across modalities. In the final stage, when the fused features from the three scales are fed into the detection head for object recognition, it is necessary to unify the two feature streams.

To this end, we introduce an ABFW module, which employs a learnable weighting mechanism to adaptively fuse features from the two branches, thereby providing precise control over the contribution of cross-modal interactive features. Collectively, the IF2M and ABFW modules form the proposed dual-level attention relearning mechanism, which effectively leverages the complementarity and discriminative power of multimodal features at different levels.

As illustrated in Figure 7, during the training, the inputs for adaptive cross-modal fusion are defined as the feature maps and from the IF2M. A learnable fusion weight vector is introduced. To ensure that the weights remain within a reasonable range and are interpretable, a Softmax function is applied to normalize the raw parameters, yielding the actual fusion coefficients αr and αi, as expressed in Equation (16). These weight parameters are optimized via backpropagation and dynamically adjusted during training to learn the optimal fusion ratio. The final fused feature Ff is obtained through a weighted summation, as defined below:

Figure 7.

Structure of the ABFW module at the first stage of combination. The “+” symbol in the circles denotes feature addition.

This fusion strategy not only enhances the stability of multimodal feature integration but also enables the network to adaptively adjust the contribution of each feature branch based on specific task requirements. Compared with conventional approaches, such as average fusion or fixed-weight fusion, the proposed ABFW module offers greater flexibility in modeling the actual contribution of each modality to the final feature representation.

3. Experimental Results and Analysis

We conduct experiments on the aerial vehicle detection public dataset DroneVehicle [23] as well as our self-constructed UAV-based oil-spill detection dataset OilLeak to comprehensively evaluate the detection performance of the proposed DLANet. We first present the key training parameters and implementation details of the model. Next, we compare the proposed DLANet with nine state-of-the-art methods. Subsequently, ablation studies are conducted to quantify the contribution of each module to overall performance and to assess the network’s sensitivity to alignment deviations. We further evaluate rotation angle errors for targets of different sizes as well as model robustness under varying illumination and occlusion conditions. Finally, to better interpret the sources of performance gains, we visualize the feature heatmaps produced by the dual-level attention relearning modules, IF2M and ABFW, and provide a feature-level interpretability analysis.

3.1. Implementation Details

3.1.1. Training Configurations

We selected nine SOTA object detection methods for comparative evaluation. In addition, we retrained the UA-CMDet [23] and CFT [27] models. Experiments were conducted on an Ubuntu 22.04 system equipped with an Intel® Xeon® Gold 6330 CPU @ 2.00 GHz and an Nvidia GeForce RTX 4090 GPU with 24 GB memory. The CUDA version was 12.1, and PyTorch version was 2.3. Since the original CFT [27] model was designed for horizontal bounding box detection, we replaced its detection head with a rotated bounding box head to support oriented object detection.

DLANet (Ours): The network was trained for 50 epochs, with early stopping triggered if no improvement was observed for 10 consecutive epochs. The batch size was eight. The optimizer used was stochastic gradient descent (SGD), with an initial learning rate of 0.01, momentum of 0.95, and weight decay of 0.0005. To mitigate the risk of overfitting caused by small mini-batches at the early training stage, a learning rate warm-up mechanism was introduced. The warm-up lasted for three epochs, during which the momentum was adjusted to 0.8 and the bias learning rate was set to 0.1. During the training, data augmentation using mosaic was applied, with a probability of 0.5.

UA-CMDet [23]: Each training image was randomly flipped horizontally, with a probability of 0.5 to improve data diversity. The network was trained for 50 epochs using the SGD optimizer, with an initial learning rate of 0.005, batch size of two, momentum of 0.9, and weight decay of 0.0001.

CFT [27]: The network was trained using SGD with an initial learning rate of 0.01 and momentum of 0.937. The total number of training epochs was set to 50, with a batch size of eight. Both training and testing used images resized to 640 × 640.

3.1.2. Evaluation Metrics

To comprehensively assess the performance of the proposed method and facilitate comparison with existing approaches, we employ commonly used evaluation metrics [40], including precision (P), recall (R), AP0.5 (average precision at IoU threshold 0.5), mAP0.5, and mAP0.5:0.95. The calculation formulas are as follows:

where NTP refers to the number of true positives, meaning the predicted bounding box by the detector satisfies the intersection over union (IoU) threshold with the ground truth (GT). Otherwise, it is counted as a false positive (FP). NFN indicates that a ground truth object exists but the detector fails to identify it. Equation (20) defines AP as the integral of the precision–recall curve (PRC) for each category. AP0.5 refers to the average precision when the IoU threshold is set to 0.50. mAP0.5 is calculated in Equation (21) as the mean of all AP values across all categories at IoU = 0.50. mAP0.5:0.95 refers to the mean AP values across IoU thresholds from 0.50 to 0.95, with an interval of 0.05. It is obtained as the mean of all category-wise AP values over these thresholds, providing a more rigorous evaluation of detection performance.

In addition, the rotation angle error is introduced to evaluate orientation estimation accuracy. Since orientation is a circular variable with inherent periodicity, the angular difference is defined as the minimum between the direct angular deviation and its complementary angle within the periodic domain:

where and denote the orientations of the longer sides of the i-th correctly detected target (with IoU > 0.5) and its corresponding ground-truth target, respectively, measured with respect to the x-axis.

3.2. Comparative Evaluation of Detection Performance

We compare the proposed DLANet with nine SOTA methods, including two single-modality detectors based on TIR [41,42], and seven dual-modality RGB–TIR detection methods [10,23,26,27,28,30,43]. In addition, we also evaluate the baseline model without any additional modules.

3.2.1. Evaluation on the DroneVehicle Dataset

Table 2 presents a comparison of detection accuracy among SOTA methods on the DroneVehicle test dataset. Overall, the proposed DLANet achieves an mAP0.5 of 0.858 and an mAP0.5:0.95 of 0.691 across all categories, surpassing one of the most effective multimodal detection methods, MGMF [26], by 5.5% and 13.9%, respectively. The retrained UA-CMDet [23] method achieves higher accuracy than its original implementation, with a 9.2% improvement in mAP0.5. In contrast, performance using RGB alone is limited, largely due to the substantial proportion of nighttime data in the DroneVehicle dataset. Notably, the infrared-oriented DTNet [41] and I2MDet [42] also deliver competitive accuracy, in some categories exceeding that of dual-modal fusion methods. Compared with the representative dual-modal UA-CMDet [23], their mAP0.5 improves by 4.1–5.3%, suggesting that redundant features generated during modal fusion may hinder detection performance.

Table 2.

Results from comparative experiments against various SOTA methods on the DroneVehicle test dataset. Red indicates the best result. Blue indicates the second best.

At the category level, the AP0.5 values for the car category are generally high across all methods, consistently exceeding 90%, primarily because this category constitutes the largest proportion in the dataset. In contrast, the AP0.5 for freight car and van is considerably lower, mainly due to their high morphological similarity, which increases inter-class confusion, as well as their relatively small dataset proportion. The statistical analysis indicates that freight car constitutes 16.82% and 14.62% of the training and test sets, respectively, whereas van accounts for only 2.10% and 2.37%. This combination of class imbalance and feature similarity explains the reduced detection accuracy for these categories. Importantly, for the van category, our DLANet achieves improvements of 6.1%, 3.0%, and 2.2% over DDCINet-Rol-Trans [10], DMM [30], and MGMF [26], respectively. These results further demonstrate the effectiveness of our approach in distinguishing few-shot and easily confusable categories.

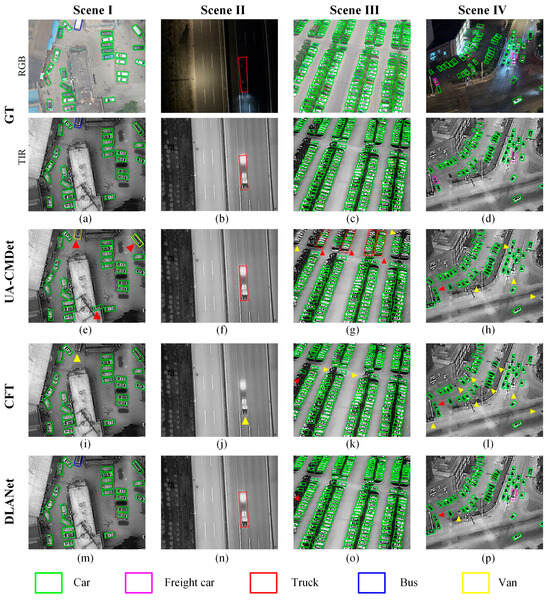

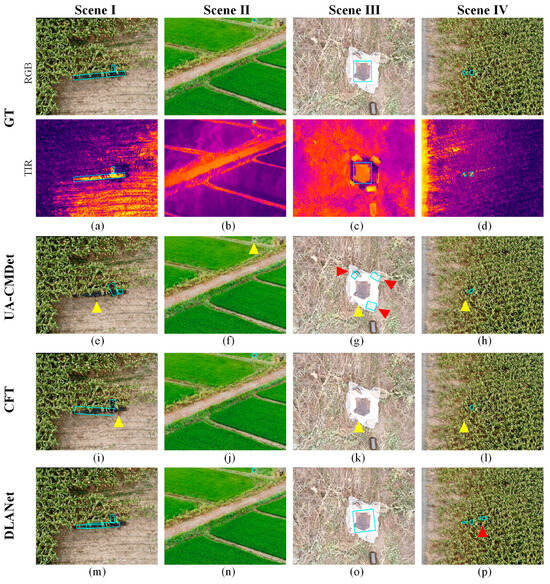

In Figure 8, we overlay the detection results of each method on the TIR images for visualization. Scene I corresponds to a typical residential area environment. As shown in the ground truth (Figure 8a), certain shadow-like regions resembling dark vehicles appear in the TIR images, although no corresponding objects are visible in the RGB images. This phenomenon reflects the sensitivity of TIR imagery to residual thermal traces. When a vehicle remains stationary for a period of time, the ground beneath it either receives less solar radiation or is heated by the vehicle body. After the vehicle departs, the temperature difference between the previously covered area and the surrounding surface produces a distinct “cold” or “hot” residual pattern in the TIR image. Even though the vehicle is no longer present, such traces may still be captured by the TIR camera. A comparison of different methods shows that dual-modality fusion provides complementary advantages in addressing such feature discrepancies. Specifically, the “residual trace” phenomenon in TIR images can be effectively suppressed by incorporating RGB information, thereby reducing false detections.

Figure 8.

Detection results of different methods across four scenarios on the DroneVehicle test dataset. (a–d): Ground truth. (e–h): Detection results of UA-CMDet [23]. (i–l): Detection results of CFT [27]. (m–p): Detection results of DLANet. Yellow triangles indicate missed detections, whereas red triangles indicate false detections.

Scenes II, III, and IV correspond to fast-moving targets, a densely packed parking lot, and a nighttime traffic intersection, respectively. The detection results indicate that identifying targets under dense arrangements and low-illumination conditions remains challenging. All three methods are able to detect vehicles, but DLANet produces more reliable results. In contrast, UA-CMDet [23] tends to misclassify vehicles, while CFT [27] exhibits more missed detections. These findings highlight the effectiveness of our DLANet in enhancing better classification and localization.

3.2.2. Evaluation on the OilLeak Dataset

As shown in Table 3, DLANet achieves the highest detection accuracy on the OilLeak test dataset, with an mAP0.5 of 0.849. Compared with the multimodal object detection methods UA-CMDet [23] and CFT [27], our approach achieves performance improvements of 13.4% and 12.1%, respectively. Relative to single-branch RGB and TIR single-modal methods, DLANet improves the mAP0.5 by 14.0% and 13.9%, respectively. Although TIR data can effectively capture the thermal radiation characteristics of oil-leakage targets, its lack of texture and color information reduces recognition accuracy. Specifically, while the TIR modality improves precision by 9.4% compared with the RGB modality, its recall decreases by approximately 5.0%, leading to only a small overall difference in mAP. These results demonstrate the inherent limitations of single-modal detection and underscore the importance of fully exploiting complementary multimodal information to improve detection accuracy [44].

Table 3.

Detection accuracy comparison of different methods on the OilLeak test dataset. Red indicates the best result. Blue indicates the second best.

As shown in Figure 9, we present visual detection results of different methods across four representative scenarios in the OilLeak test dataset. For clearer visual comparison, the detection outputs are overlaid on the RGB images, with each column corresponding to one scenario. Scene I illustrates a real-world case of oil leakage from an underground pipeline to the surface, representing a large-scale spill. All three methods successfully detect the target; however, only DLANet delineates the leakage boundary with near-complete accuracy (Figure 9m). Scene II represents a small-object detection scenario, with the oil spill located in the upper-right corner. As shown in Figure 9f, UA-CMDet [23] exhibits limited sensitivity to small targets and fails to detect the spill. Scene III simulates a controlled spill event: oil was poured onto a plastic sheet, which was fixed at the corners with bricks to prevent wind disturbance. Visualization results show that UA-CMDet incorrectly detects the bricks as oil spills while missing the actual spill region (Figure 9g). Comparing Figure 9j and Figure 9k, CFT [27] demonstrates good performance in detecting small objects but exhibits clear missed detections for larger targets.

Figure 9.

Detection results of different methods on four representative scenarios from the OilLeak test dataset. (a–d): Ground truth. (e–h): Detection results of UA-CMDet [23]. (i–l): Detection results of CFT [27]. (m–p): Detection results of DLANet. Yellow triangles indicate missed detections, whereas red triangles indicate false detections. The light-blue boxes in the figure denote the locations of the detected oil leaks.

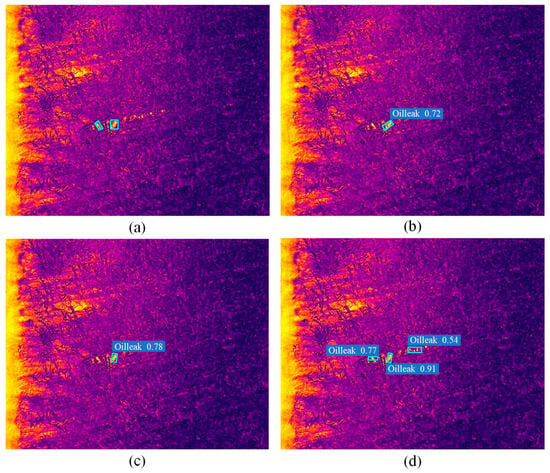

As demonstrated in previous studies, TIR imagery captures radiative differences independent of external illumination, making it well suited for imaging under complex backgrounds or low-light conditions. This advantage is particularly beneficial for detecting small targets with strong thermal signatures [45]. Figure 10 illustrates the detection performance in Scene IV of Figure 9, where the outputs of the three methods are overlaid on the TIR data. In this scenario, partial occlusion occurs as portions of the oil spill are concealed by surrounding maize vegetation. As shown in Figure 10a, two spill regions are present. UA-CMDet [23] (Figure 10b) and CFT [27] (Figure 10c) successfully detect the larger spill but fail to identify the smaller occluded spill on the left. In contrast, the proposed DLANet (Figure 10d) correctly detects both spill locations with higher confidence scores of 0.77 and 0.91, respectively. Although one false positive appears on the right side of the image, the overall performance still surpasses that of the other methods.

Figure 10.

Analysis of oil detection results under occlusion conditions. (a) Ground truth. (b) Detection results of UA-CMDet [23]. (c) Detection results of CFT [27]. (d) Detection results of DLANet. The light-blue boxes in the figure denote the locations of the detected oil leaks.

3.3. Ablation Study of DLANet

3.3.1. Module Contribution Analysis

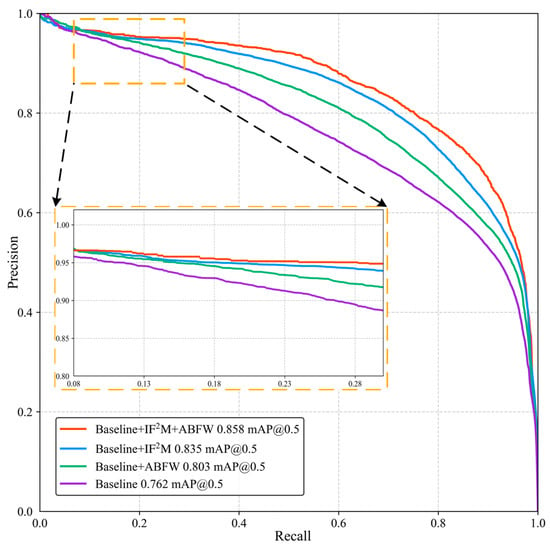

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed dual-level attention relearning mechanism for multimodal object detection, we conducted ablation experiments on the DLANet using the DroneVehicle and OilLeak datasets. These experiments evaluate the contributions of the IF2M and ABFW modules to detection accuracy.

As shown in Table 4, the baseline model achieves the lowest performance across all configurations, with an mAP0.5 of 0.762. Overall, both the IF2M and ABFW modules significantly enhance the detection accuracy of the model, with the most substantial improvement observed when they are combined. The synergy between these two modules plays a crucial role in boosting multimodal detection performance. Compared with configurations using only a single module, the complete model improves performance by an average of 3.9%, confirming a strong synergistic effect between IF2M and ABFW. Specifically, introducing the IF2M alone increases mAP0.5 by 7.3%, while the ABFW module contributes a 5.4% improvement—the former’s gain being approximately 1.35 times that of the latter. This finding suggests that, although ABFW also positively affects performance, IF2M has a more substantial role in enhancing feature interaction and fusion.

Table 4.

Ablation analysis of fusion module in DLANet on the DroneVehicle dataset.

Figure 11 shows the precision–recall (PR) curves of the model under different module configurations on the DroneVehicle dataset. As illustrated, the proposed DLANet (baseline + IF2M + ABFW) consistently outperforms other combinations across the entire recall range, achieving a final mAP0.5 of 0.858 and demonstrating the best overall performance. Except for the baseline, all other configurations maintain precision above 0.9 in the recall range below 0.3, indicating high accuracy for high-confidence samples. Among these, the baseline + IF2M + ABFW configuration exhibits the smoothest and most stable curve with the least fluctuation, thereby demonstrating superior robustness in this region.

Figure 11.

Precision–recall (PR) curve comparison of ablation study on the DroneVehicle dataset.

Table 5 presents the ablation study results on the OilLeak dataset. Without any interaction modules, the baseline network achieves an mAP0.5 of 0.722. Introducing the IF2M module individually increases detection accuracy to 0.808, representing an 8.6% improvement over the baseline. Incorporating only the ABFW module raises the mAP0.5 to 0.776, corresponding to a 5.4% relative improvement. When both modules are used jointly, the model achieves a final mAP0.5 of 0.849, which is 12.7% higher than the baseline. The results in Table 4 and Table 5 demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed dual-layer attention relearning mechanism in enhancing feature fusion and interaction modeling.

Table 5.

Ablation analysis of fusion module in DLANet on the OilLeak dataset.

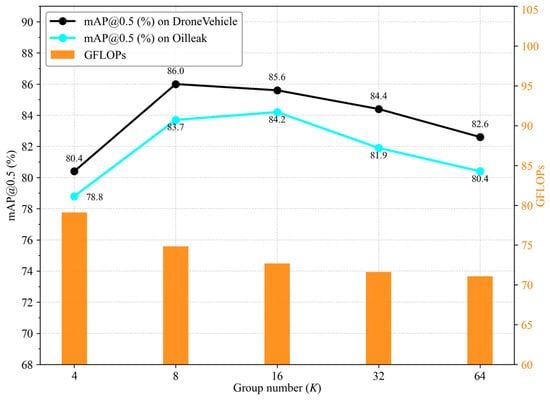

3.3.2. Effect of Different K Values in IF2M

As shown in Figure 12, five different values of K are evaluated in the IF2M fusion module through retraining and testing. As the group number K increases, the computational cost decreases consistently due to reduced inter-channel interactions. In contrast, the mAP follows an inverted-U-shaped trend, reaching its peak at moderate group numbers (K = 8 and 16).

Figure 12.

Accuracy–efficiency trade-off under different group numbers K.

Specifically, increasing K from four to eight leads to a notable improvement in detection accuracy, as a moderate grouping strategy facilitates more discriminative and fine-grained feature modeling. However, further increasing K results in fragmented channel semantics and diminished intra-group representation capacity, which, in turn, degrades detection performance. When K ≥ 32, the GFLOPs decrease only marginally from 71.63 to 71.09, while the mAP drops by approximately 1.5–1.8%. In this regime, the computational savings become negligible relative to the observed performance degradation. These results suggest that a moderate group number (e.g., K = 8 or 16) provides a favorable trade-off between accuracy and efficiency.

Table 6 reports the number of parameters and computational cost for each method. Model complexity is evaluated in terms of GFLOPs, which are computed using the ptflops tool with an input resolution of 640 × 640. The proposed DLANet demonstrates strong lightweight characteristics, containing the fewest parameters among all compared methods—only 39.04 M parameters and a computational cost of 72.69 GFLOPs. Compared to the baseline model, the parameter count increases by just 0.09 M, a marginal growth of less than 0.23%. As shown in Table 4, this slight increase yields a 9.6% improvement in mAP0.5, while the average inference time increases by only 4.2 ms, highlighting the proposed method’s effective balance between accuracy and efficiency. The lightweight model architecture facilitates the practical deployment of UAV platforms.

Table 6.

Comparison of interpretation efficiency among multimodal object detection methods on the DroneVehicle dataset.

3.3.3. Sensitivity Analysis of Detection Accuracy to Simulated Registration Offsets

To quantitatively assess the impact of spatial misalignment, we simulate registration errors between RGB and TIR images by introducing fixed random offsets in four directions (up, down, left, and right) during the inference stage on the test data and conduct a sensitivity analysis of detection accuracy.

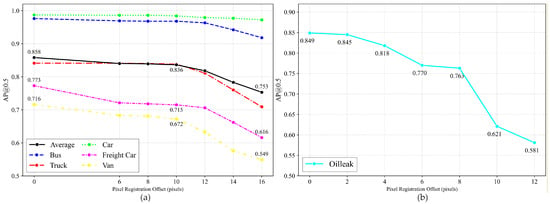

As shown in Figure 13, the mAP decreases monotonically with increasing pixel offset in both datasets. Notably, at small offsets (≤8 pixels for the DroneVehicle dataset and ≤4 pixels for the OilLeak dataset), DLANet maintains relatively stable performance, indicating robustness to minor registration errors.

Figure 13.

Impact of simulated registration offsets on detection performance: (a) DroneVehicle dataset; (b) OilLeak dataset.

In the DroneVehicle dataset, the Van category exhibits the highest sensitivity to pixel offsets. When the offset increases from 10 to 16 pixels, the detection accuracy drops by 12.3%. This observation indicates that offset-induced misalignment between modal features can adversely affect the detection of classes with limited training samples, such as Van. Compared with the DroneVehicle dataset, oil-leak targets show greater sensitivity to registration offsets. This can be attributed to their stronger reliance on color texture and thermal radiation cues, which are more susceptible to spatial misalignment between RGB and TIR modalities.

3.4. Detection Accuracy and Rotation Angle Error Across Different Target Sizes

Targets are categorized according to their area, and detection accuracy is averaged across different size groups. Following recent studies on UAV dataset construction [11], we adopt the COCO protocol to define small, medium, and large objects. Specifically, small objects have an area smaller than pixels, medium objects have an area between and pixels, and large objects have an area of at least pixels.

The detection results for targets of different sizes (Table 7) indicate that DLANet consistently outperforms the other methods across small, medium, and large targets. It achieves the highest precision and recall in all size categories, demonstrating strong capability in modeling multi-scale targets. In particular, for small targets, DLANet attains a precision of 0.797 and a recall of 0.836. By contrast, the baseline model exhibits relatively stable performance on medium and large targets, but its detection capability for small targets remains limited. UA-CMDet [23] shows a certain advantage in recall for medium and large targets; however, its precision is notably lower, suggesting a higher false-positive rate. The CFT [27] method improves recall for small and medium targets, but the gain in precision is marginal, resulting in constrained overall performance.

Table 7.

Accuracy evaluation of different models on targets of varying sizes in the DroneVehicle dataset. Red indicates the best result. Blue indicates the second best.

Furthermore, orientation estimation quality is assessed using the rotation angular error and Acc@θ metrics, with . The rotation angle is defined by the direction of the long side of the oriented bounding box and is evaluated under a 180° periodicity constraint.

Table 8 indicates that rotation angle estimation performance consistently improves with increasing target size. For medium and large targets, the accuracy at Acc@5° exceeds 94%, while the average angle error (AAE) decreases to 1.85° and 1.54°, respectively, indicating more stable and accurate orientation regression for larger targets. By contrast, small targets exhibit slightly larger angular errors due to limited spatial information. Nevertheless, Acc@10° and Acc@15° still reach 96.46% and 97.50%, respectively, suggesting that DLANet maintains acceptable orientation prediction performance even for small targets.

Table 8.

Evaluation of rotation angle error for targets of different sizes in the DroneVehicle dataset.

3.5. Robustness Assessment to Varying Illumination and Occlusion

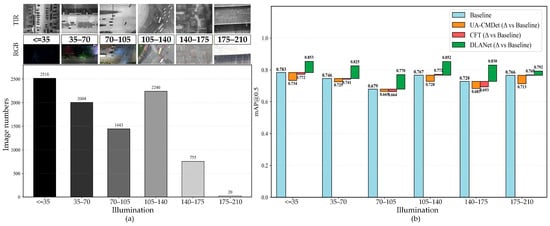

In practical UAV monitoring scenarios, objects often appear under extreme illumination conditions or partial occlusion, which pose significant challenges to detection algorithms. To investigate the robustness of DLANet in such scenarios, we conducted a detailed analysis across different lighting and occlusion levels.

As shown in Figure 14a, the RGB images in the test set were converted to grayscale, and their mean gray values were used to quantify illumination brightness. The overall brightness in the test set ranges from 0 to 206, which we further divided into six levels representing complete darkness, dusk, daytime, and overexposed conditions. Across these illumination levels, DLANet exhibited only minor performance fluctuations. Compared with the baseline, it achieved an improvement of 2.6–10.2%, demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed dual-branch fusion strategy. As illumination conditions varied, the mAP0.5 metric exhibited a decreasing–increasing pattern. In the brightness range of 70–105, corresponding to evening conditions, insufficient visible-light illumination reduced the contribution of TIR features during the fusion process. All four models followed this trend, with the most pronounced performance degradation observed in the van and freight car categories.

Figure 14.

Assessment of detection performance across different illumination conditions. (a) Six illumination levels and the corresponding RGB and TIR images. The bars in varying shades of gray indicate the illumination brightness of the corresponding range, and the numbers above them show the number of images. (b) mAP0.5 of different models across illumination conditions on the DroneVehicle test dataset.

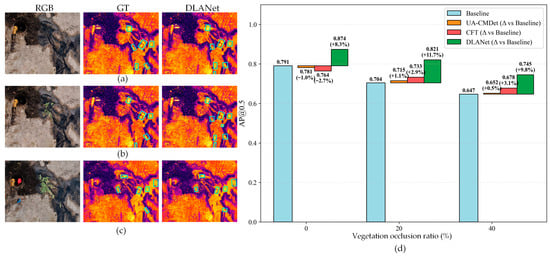

In practical oil-spill scenarios, we simulated farmland conditions during the crop growing season by placing corn leaves with different coverage areas over the spill region and acquiring imagery using a UAV. Figure 15a–c present a representative case from the test set. As the vegetation occlusion area increases, both the thermal infrared and RGB images experience a loss of discriminative information, leading to a reduced detectable region and lower leak-detection accuracy. As shown in Figure 15d, when the occlusion ratios are 20% and 40%, the UA-CMDet [23] and CFT [27] models exhibit modest improvements of 0.5–3.1% over the baseline. Notably, even under 40% occlusion, DLANet maintains an AP exceeding 0.7.

Figure 15.

Assessment of detection performance across different vegetation occlusion conditions. (a–c) RGB images, GT, and DLANet detection results under no occlusion, 20% occlusion, and 40% occlusion, respectively. (d) mAP0.5 scores of different models under the corresponding vegetation occlusion conditions on the OilLeak test dataset. The light-blue boxes in the figure denote the locations of the detected oil leaks.

To quantitatively analyze the dynamic behavior of ABFW, we statistically examined variations in the modal weights αr (RGB) and αi (TIR) across different scene conditions and feature scales. As summarized in Table 9, the learned weights exhibit adaptive and scene-dependent variations, particularly under varying illumination conditions, indicating the effectiveness of the proposed dynamic adjustment mechanism.

Table 9.

ABFW weight adjustment for RGB and TIR modalities under different scenarios.

In completely dark scenes, the contribution of RGB features at all levels is nearly negligible (αr = 0.05−0.11), which is consistent with physical imaging principles. As illumination increases, the contributions of the two modalities become more balanced. In daytime scenes, RGB features tend to receive higher weights at high-resolution levels (R3) due to richer spatial details, with αr = 0.65 ± 0.15. By contrast, in overexposed scenes, visible-light features are suppressed across all three feature scales, while TIR features become dominant.

For practical oil-spill scenarios, which are consistently acquired under daytime conditions, performance gains arise primarily from the coordinated contribution of both modalities, reflecting implicit adaptation to scene characteristics. Overall, these observations align well with the properties of multimodal UAV imagery and validate the rationality of the proposed adaptive weighting strategy.

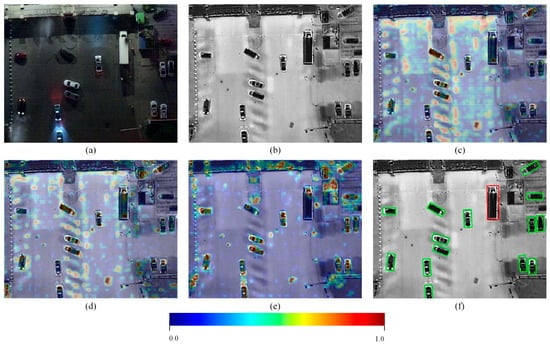

3.6. Feature-Level Interpretability and Visualization Analysis

Figure 16 and Figure 17 visualize the feature extraction process of the DLANet model on RGB and TIR images using the Grad-CAM [46] method, examining the model’s interpretability across different scenarios. In the nighttime scene (Figure 16), the TIR branch exhibits strong attention to certain “residual thermal traces,” despite some background noise. In contrast, due to insufficient illumination, vehicle targets in the RGB branch show low saliency, making it difficult for the model to extract discriminative features. With progressive feature fusion, Figure 16d shows that, after the first fusion via the IF2M module, complementary features from both modalities are effectively enhanced, allowing the model to focus more precisely on true targets, although some residual heat traces remain partially suppressed. After further introducing the ABFW module at the R3 scale (Figure 16e), the model’s response to false targets is substantially reduced, producing clearer feature maps concentrated on vehicle targets. Consequently, all vehicle targets are correctly classified (Figure 16f).

Figure 16.

Visualization of feature maps at different fusion stages of the DLANet model under nighttime conditions in the DroneVehicle dataset. (a) RGB image. (b) TIR image. (c) Feature maps overlaid on the TIR image from the baseline model. (d) Feature maps overlaid on the TIR image after the first IF2M fusion. (e) Feature maps overlaid on the TIR image after the first IF2M + ABFW fusion. (f) Detection results overlaid on TIR image. All feature maps were normalized to the range [0, 1]. Redder colors indicate stronger responses of the target of interest, whereas bluer colors correspond to weaker feature responses.

Figure 17.

Visualization of feature maps at different stages of the DLANet model under false-target conditions in the OilLeak dataset. (a) RGB image. (b) TIR image. (c) Feature maps overlaid on the RGB image from the baseline model. (d) Feature maps overlaid on the RGB image after the third IF2M + ABFW fusion. All feature maps were normalized to the range [0, 1]. Redder colors indicate stronger responses of the target of interest, whereas bluer colors correspond to weaker feature responses.

The scene in Figure 17 involves a false target formed by straw burning in farmland, which visually resembles an oil-leak target and is prone to causing false detections. As illustrated on the left side of Figure 17c, during the simple fusion process, the TIR branch network primarily focuses on targets with strong thermal radiation, such as road regions and patches formed after straw burning, yielding pronounced responses. Figure 17d demonstrates that, after integrating the IF2M and ABFW modules at the R5 scale, more texture features from the RGB branch are taken into account, and most false-target regions are assigned low-confidence responses. This indicates a significant enhancement in the model’s ability to suppress interference from such false targets, highlighting the synergistic benefits of multi-scale feature fusion and dual-level attention mechanisms in learning.

4. Discussions

4.1. Synergistic Effects of Dual-Level Attention Relearning

The experimental results on both the DroneVehicle and OilLeak datasets reveal that the superior performance of DLANet stems from the complementary hierarchy of the proposed modules. The ablation analysis (Table 4 and Table 5) highlights a distinct functional division: the IF2M module acts as the primary engine for fine-grained feature interaction, while the ABFW module acts as a selector. However, their combination yields a performance gain greater than the sum of their parts (improving mAP0.5 by an additional 3.2–6.4% when combined).

This finding corroborates the “mid-level fusion” hypothesis supported by Fang et al. [22], who demonstrated that interaction at intermediate feature levels retains the most discriminative semantics. However, unlike UA-CMDet [23], which relies on heuristic summation that treats features statically, our results suggest that feature interaction alone is insufficient. The “relearning” aspect (i.e., enforced by the ABFW) is critical. This aligns with the motivation of Wang et al. [24], who utilized mutual information to reduce redundancy. Yet, while RISNet focuses on suppressing “mutual” redundancy to avoid calculation waste, DLANet’s ABFW focuses on “dynamic weighting” to maximize scene adaptability (Table 9). This distinction suggests that high-quality feature fusion (IF2M) must be coupled with a decision-level gating mechanism (ABFW) to fully exploit cross-modal complementarity.

4.2. Robustness Under Challenging Environmental Conditions

A critical challenge in UAV remote sensing is the instability of imaging conditions [47,48]. Our illumination sensitivity analysis (Figure 14) demonstrates that DLANet maintains consistent detection accuracy across broad brightness ranges. The “U-shaped” performance curve typically observed in single-modality baselines, where performance dips at the extremes of darkness (RGB failure) or thermal crossover (TIR failure), is effectively flattened by our strategy.

This contradicts the premise of DTNet [41] and I2MDet [42], which prioritize enhancing the TIR modality as the primary solution for adverse conditions. Our results indicate that, even in low-light scenarios (e.g., Scene IV, Figure 8), the RGB modality contributes essential contextual cues that purely TIR-focused methods miss. Furthermore, our occlusion experiments (Figure 15) show that DLANet maintains an AP > 0.7 under 40% occlusion, whereas competitors like CFT [27] drop below 0.65. While Fang et al. [27] utilize Transformers in CFT to capture global context for occlusion handling, our results suggest that the local cross-modality alignment in DLANet is more effective for small, partially occluded objects.

4.3. Mitigation of Modality-Specific False Positives

One of the most significant findings from the visual analysis is the reduction in false alarms caused by modality-specific “pseudo-targets.” In the DroneVehicle dataset, static vehicles often leave “residual thermal traces” (ghost targets) in TIR images after departing [23,49]. Single-modal TIR detectors frequently misclassify these. Similarly, in the OilLeak dataset (Figure 17), straw burning generates high-intensity hotspots mimicking oil leaks.

Existing methods like UA-CMDet [23] often struggle with this because they employ additive fusion strategies; if a target is salient in one modality, it is often propagated to the final prediction. In contrast, DLANet effectively implements a “cross-modal veto” mechanism. As seen in the visualizations (Figure 16 and Figure 17), the RGB branch (which sees no vehicle or distinct straw texture) suppresses the high-confidence false positives from the TIR branch. The statistical analysis indicates that false positives account for approximately 20.1% of all predicted detections in the oil-spill scenario. Compared with baseline single-modal and dual-modal methods, this corresponds to an absolute reduction of 7.7–17.0 percentage points. This capability to distinguish between “hot but irrelevant” (fire/ghosts) and “hot and relevant” (vehicles/oil) represents a semantic alignment advantage over heuristic fusion methods, validating the efficient aggregation approaches discussed by Zhang et al. [11].

4.4. Efficiency Paradox: Challenging the Transformer Trend

Finally, the trade-off between detection accuracy and computational cost is a pivotal factor for UAV platforms. Recent literature, such as DDCINet-Rol-Trans [10], M2FNet [28], and DMM [30], has heavily favored Transformer- and Mamba-based architectures to capture long-range dependencies, accepting a trade-off of high computational cost (often >80 GFLOPs).

DLANet challenges this trend by achieving state-of-the-art performance with only 39.04 M parameters and 72.69 GFLOPs (Table 6), which is a negligible increase (+0.23%) over the baseline and significantly lighter than DMM [30] (87.97 M parameters and 137 GFLOPs). This supports the perspective of Redmon et al. [12] that efficiency does not strictly require sacrificing accuracy if the architecture is optimized. Our results indicate that the heavy computational burden of global self-attention mechanisms in Transformers may be redundant for UAV object detection, where targets are often small and local. By replacing heavy attention with the grouped channel interactions of IF2M, DLANet proves that lightweight, rotation-aware CNNs can outperform heavier Transformer models, making it far more suitable for the practical constraints of edge deployment discussed in recent comprehensive reviews [1,50].

4.5. Potential and Limitations

DLANet demonstrates strong performance on both the DroneVehicle and OilLeak datasets, yet several opportunities for further improvement remain. The proposed dual-level attention relearning mechanism significantly enhances cross-modal interactions and improves robustness under low-illumination, occlusion, and cluttered conditions. In addition, DLANet maintains relatively stable performance in the presence of minor registration errors, indicating robustness to modest alignment inaccuracies. These advantages indicate substantial potential for broader multimodal remote sensing applications, including UAV-based disaster assessment, security inspection, and nighttime surveillance. Moreover, the adaptive modality weighting strategy suggests promising extensibility to additional sensing modalities, such as SAR, multispectral, or LiDAR, where heterogeneous information must be dynamically balanced according to scene characteristics [51].

Nevertheless, several limitations merit attention. Although a registration preprocessing step was applied prior to fusion to improve cross-modal correspondence, residual misalignment caused by parallax, altitude variations, or calibration errors remains unavoidable [50] and may degrade fusion quality, particularly for small targets whose features are highly sensitive to spatial shifts.

Furthermore, visible imagery is inherently restricted to three spectral channels, limiting its ability to distinguish targets with subtle spectral differences. Our experiments show that, in onshore oilfield environments, pseudo-targets may be falsely detected when both RGB and TIR cues present characteristics similar to true oil-spill signatures. For example, illegally discharged heated wastewater may manifest as a false alarm. This issue underscores the importance of hyperspectral imagery for capturing fine spectral variations, consistent with recent advances in camouflaged target detection that leverage spectral contrast enhancement and paired-pixel representations [52].

Finally, although the current experiments span representative daytime, nighttime, and complex background conditions, validation is limited to two UAV datasets. Broader evaluation across diverse environments, such as extreme weather, maritime settings, or multi-altitude flight scenarios, would better assess the generalizability of DLANet. Future research could also explore self-supervised pre-training [53], open-set detection [54], and domain adaptation strategies [55] to further improve robustness under unseen or distribution-shifted scenarios.

5. Conclusions

DLANet bridges the gap between high-accuracy multimodal fusion and real-time UAV deployment by employing a dual-level attention relearning strategy that dynamically reconciles feature discrepancies to suppress modality-specific noise (e.g., thermal ghosts) without incurring the heavy computational costs of Transformer-based architectures. The framework enhances feature representation and cross-modal interactions at two complementary levels: (1) the IF2M facilitates deep, multi-scale complementary learning by jointly modeling channel and spatial dependencies, and (2) the ABFW dynamically modulates the contributions of RGB and TIR branches according to scene conditions, thereby improving detection robustness under challenging environments.

To support practical applications, we constructed the OilLeak dataset for onshore oil-spill detection and developed a pre-registration preprocessing pipeline tailored to coaxial UAV RGB–TIR imagery, ensuring accurate cross-modal alignment. The experimental results on the DroneVehicle dataset demonstrate that DLANet achieves mAP0.5 improvements of 14.4% and 11.1% over RGB-only and TIR-only baselines, respectively, while surpassing state-of-the-art multimodal detection methods such as MGMF [26] by 5.5%. On the OilLeak dataset, DLANet achieves mAP0.5 gains of 13.4% and 12.1% over UA-CMDet [23] and CFT [27], respectively, confirming its effectiveness across diverse UAV monitoring scenarios. Moreover, the proposed network exhibits a lightweight design and high inference efficiency, achieving an average speed of 28.2 FPS, making it suitable for real-time deployment on UAV platforms. This study demonstrates that adaptive multimodal fusion, guided by dual-level attention mechanisms, can effectively maximize complementary information while suppressing degraded modality features, addressing the fundamental challenges highlighted in prior research.

In future work, we plan to extend DLANet to tri-modal and multispectral fusion scenarios, such as combining optical, infrared, and synthetic aperture radar data. To prevent structural redundancy and excessive computational cost as modalities increase, we aim to integrate frequency-domain attention via Fourier transform mechanisms [56] and explore feature pruning strategies, enhancing cross-modal feature learning while maintaining lightweight and efficient inference. Such advancements are expected to further strengthen UAV-based monitoring capabilities in complex and dynamic environments, with broad applications in ecology, transportation, and disaster management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.L., Z.Z., and S.C.; Methodology, Z.L.; Software, Z.L.; Validation, Z.L., Z.Z., and L.C.; Formal Analysis, Z.L.; Investigation, Z.L., L.Z., Z.Z., S.C., and L.C.; Resources, Z.L. and S.C.; Data Curation, Z.L. and L.C.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Z.L.; Writing—Review and Editing, Z.L., Z.Z., and L.Z.; Visualization, Z.L., S.C., and L.C.; Supervision, S.C.; Project Administration, S.C.; Funding Acquisition, S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2020YFA0714103) and in part by the Changchun Science and Technology Development Plan Project, the Major Science and Technology Special Project of the Changchun Satellite and Application Industry (No. 2024WX06).

Data Availability Statement

The OilLeak dataset and implementation code are publicly available at https://github.com/qingchengboy/OilleakDataset (accessed on 25 August 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UAV | Unmanned aerial vehicle |

| DLANet | Dual-level attention network |

| TIR | Thermal infrared |

| IF2M | Implicit fine-grained fusion module |

| ABFW | Adaptive branch feature weighting |

| YOLO | You only look once |

| SSD | Single-shot multiBox detector |

| CMAFF | Cross-modal attention feature fusion |

| RISNet | Redundant information suppression network |

| NMS | Non-maximum suppression |

| CFT | Cross-modal feature Transformer |

| UMA | Unified modality attention |

| CMA | Cross-modality attention |

| HRNet | High resolution network |

| CFR | Context feature representation |

| C2PSA | Cross stage partial with spatial attention |

| SPPF | Spatial pyramid pooling fast |

| MSFC | Multi-scale feature cascade |

| AAP | Adaptive average pooling |

Appendix A. The Architecture of the DLANet

Table A1 presents the four main components of the DLANet network. The feature extraction structures of the RGB and TIR subnetworks are consistent with the backbone. The network inputs are RGB and TIR images of identical size, 640 × 640 × 3. Here, k denotes the convolution kernel size, s represents the stride, and p indicates the padding size applied prior to convolution.

Table A1.

The structure table of the DLANet.

Table A1.

The structure table of the DLANet.

| Module | Scale | Unit | Kernels’ Number | Parameters | Input | Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Backbone (RGB/TIR) | R1 | Conv | 64 | k:3 × 3, s:2, p:1 | 640 × 640 × 3 | 320 × 320 × 64 |

| R2 | Conv | 128 | k:3 × 3, s:2, p:1 | 320 × 320 × 64 | 160 × 160 × 128 | |

| C3K2 | 32, 64, 128, 256 | k:3 × 3/1 × 1, s:1, p:1 | 160 × 160 × 128 | 160 × 160 × 256 | ||

| R3 | Conv | 256 | k:3 × 3, s:2, p:1 | 160 × 160 × 256 | 80 × 80 × 256 | |

| C3K2 | 64, 128, 256, 512 | k:3 × 3/1 × 1, s:1, p:1 | 80 × 80 × 256 | 80 × 80 × 512 | ||

| R4 | Conv | 512 | k:3 × 3, s:2, p:1 | 80 × 80 × 512 | 40 × 40 × 512 | |

| C3K2 | 128, 256, 512, 1024 | k:3 × 3/1 × 1, s:1, p:1 | 40 × 40 × 512 | 40 × 40 × 512 | ||

| R5 | Conv | 512 | k:3 × 3, s:2, p:1 | 40 × 40 × 512 | 20 × 20 × 512 | |

| C3K2 | 128, 256, 512, 1024 | k:3 × 3/1 × 1, s:1, p:1 | 20 × 20 × 512 | 20 × 20 × 512 | ||

| SPPF | 256, 512, 1024 | k:5 × 5/1 × 1, s:1, p:1,2 | 20 × 20 × 512 | 20 × 20 × 512 | ||

| C2PSA | 256, 512 | k:3 × 3/1 × 1, s:1, p:1 | 20 × 20 × 512 | 20 × 20 × 512 | ||

| IF2M | R3 | Softmax AAP Conv | 32 | k:3 × 3/1 × 1, s:1, p:1 | 80 × 80 × 256 80 × 80 × 256 | 80 × 80 × 256 80 × 80 × 256 |

| R4 | 64 | k:3 × 3/1 × 1, s:1, p:1 | 40 × 40 × 512 40 × 40 × 512 | 40 × 40 × 512 40 × 40 × 512 | ||

| R5 | 64 | k:3 × 3/1 × 1, s:1, p:1 | 20 × 20 × 512 20 × 20 × 512 | 20 × 20 × 512 20 × 20 × 512 | ||

| ABFW | R3 | Add | 512 | αr, αi | 80 × 80 × 512 80 × 80 × 512 | 80 × 80 × 512 |

| R4 | 512 | αr, αi | 40 × 40 × 512 40 × 40 × 512 | 40 × 40 × 512 | ||

| R5 | 512 | αr, αi | 20 × 20 × 512 20 × 20 × 512 | 20 × 20 × 512 | ||

| Detection head | R3 | Conv | 64, 256 | k:3 × 3/1 × 1, s:1, p:1 | 80 × 80 × 256 | 80 × 80 × (5 + L) |

| R4 | 64, 512 | k:3 × 3/1 × 1, s:1, p:1 | 40 × 40 × 512 | 40 × 40 × (5 + L) | ||

| R5 | 64, 512 | k:3 × 3/1 × 1, s:1, p:1 | 20 × 20 × 512 | 20 × 20 × (5 + L) |

AAP denotes adaptive average pooling (AdaptiveAvgPool2d); L denotes the number of classes.

References

- Han, W.; Chen, J.; Wang, L.; Feng, R.; Li, F.; Wu, L.; Tian, T.; Yan, J. Methods for Small, Weak Object Detection in Optical High-Resolution Remote Sensing Images: A Survey of Advances and Challenges. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2021, 9, 8–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, J.; Ma, A.; Zhang, L. Building Damage Assessment for Rapid Disaster Response with a Deep Object-Based Semantic Change Detection Framework: From Natural Disasters to Man-Made Disasters. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 265, 112636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Ma, A.; Lu, X.; Zhang, L. COLOR: Cycling, Offline Learning, and Online Representation Framework for Airport and Airplane Detection Using GF-2 Satellite Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 58, 8438–8449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Zhi, X.; Shi, T.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Sun, X. Dataset and Benchmark for Ship Detection in Complex Optical Remote Sensing Image. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5642611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, K.; Bai, S.; Xie, L.; Qi, H.; Huang, Q.; Tian, Q. CenterNet++ for Object Detection. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 46, 3509–3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Wang, P.; Diao, W.; Rong, X.; Li, X.; Fu, K.; Sun, X. MoCG: Modality Characteristics-Guided Semantic Segmentation in Multimodal Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5625818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.; Zhang, H.; Shu, X.; Liu, Q.; Chang, X.; He, Z.; Shi, G. Thermal Infrared Target Tracking: A Comprehensive Review. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 73, 5000419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.; Su, J. RGBT Tracking: A Comprehensive Review. Inf. Fusion 2024, 110, 102492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Haase-Schutz, C.; Rosenbaum, L.; Hertlein, H.; Glaser, C.; Timm, F.; Wiesbeck, W.; Dietmayer, K. Deep Multi-Modal Object Detection and Semantic Segmentation for Autonomous Driving: Datasets, Methods, and Challenges. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 22, 1341–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, W.; Huang, M.; Hu, J.; Xiang, X. Dual-Dynamic Cross-Modal Interaction Network for Multimodal Remote Sensing Object Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5401013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Chai, B.; Song, J.; Tian, T.; Zhu, P.; Ma, J.; Tian, J. Omni-Scene Infrared Vehicle Detection: An Efficient Selective Aggregation Approach and a Unified Benchmark. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2025, 223, 244–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.-Y.; Berg, A.C. Ssd: Single Shot Multibox Detector. In Proceedings of the 14th European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Yan, J.; Feng, Z.; He, T. R3det: Refined Single-Stage Detector with Feature Refinement for Rotating Object. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2021, 35, 3163–3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Cheng, G.; Wang, J.; Yao, X.; Han, J. Oriented R-CNN for Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 3520–3529. [Google Scholar]