MSMCD: A Multi-Stage Mamba Network for Geohazard Change Detection

Highlights

- A novel multi-stage Mamba network (MSMCD) for change detection is proposed, which integrates global dependency modeling, local difference enhancement, edge constraints, and frequency-domain fusion strategies, achieving precise perception of geohazard change areas.

- Experimental results on three remote sensing benchmark datasets for landslide, post-earthquake building, and unstable rock mass change detection demonstrate that MSMCD achieves state-of-the-art performance across all tests, confirming its strong multi-scene application capability.

- This study provides an effective solution for robust and accurate remote sensing change detection in complex geohazard scenarios. The proposed global–local–edge–frequency collaborative processing framework significantly improves model performance under complex backgrounds and interference.

- The research outcomes can advance the application of remote sensing technology in geohazard monitoring, providing reliable technical support for the full-cycle management of geological disasters and promoting practical application in remote sensing-based change detection research.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

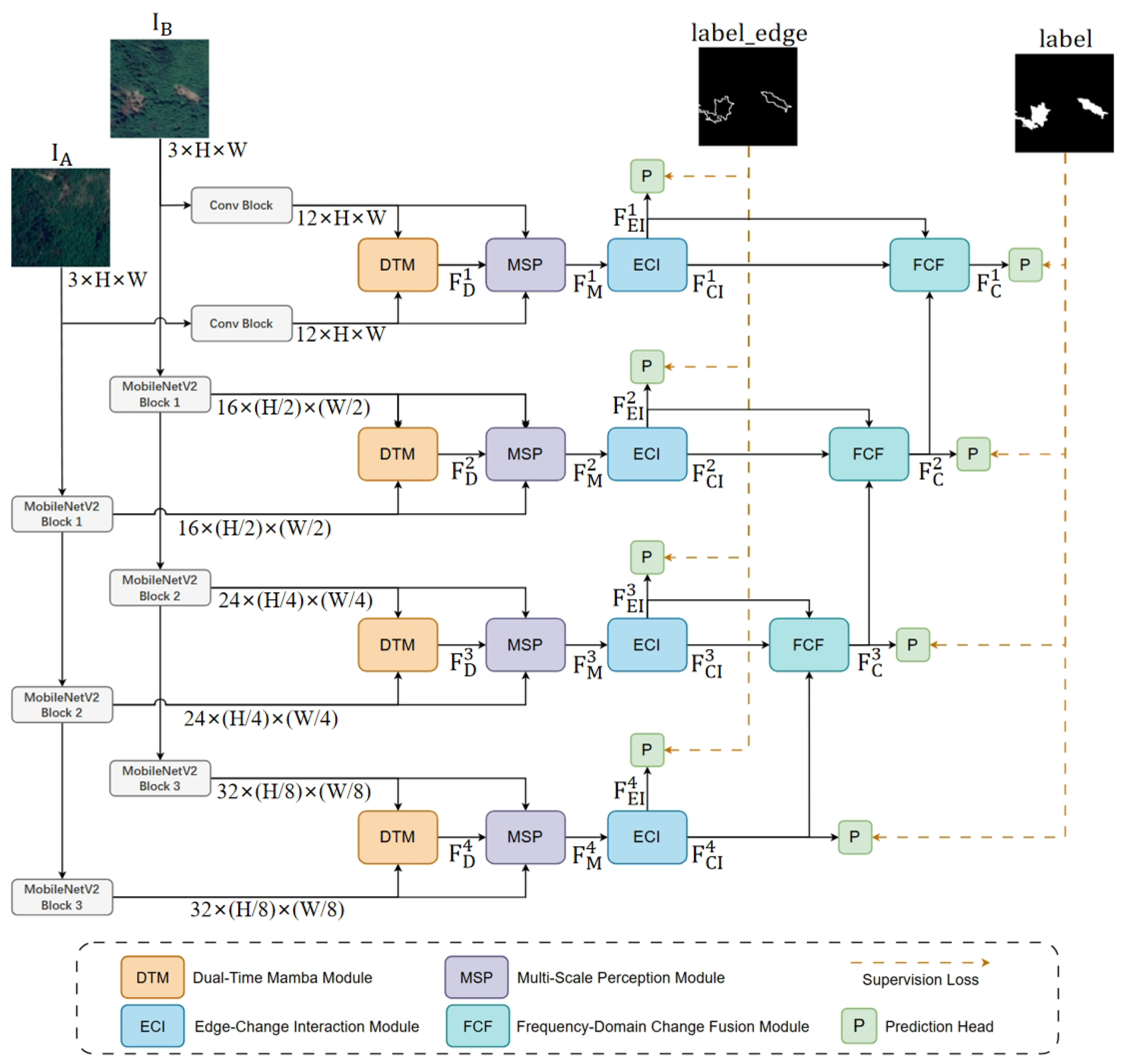

- A Mamba-based multi-stage change detection model, MSMCD, is proposed. The model constructs a global–local–edge–frequency collaborative processing framework, improving the robustness and accuracy of change detection in complex geological disaster scenarios.

- (2)

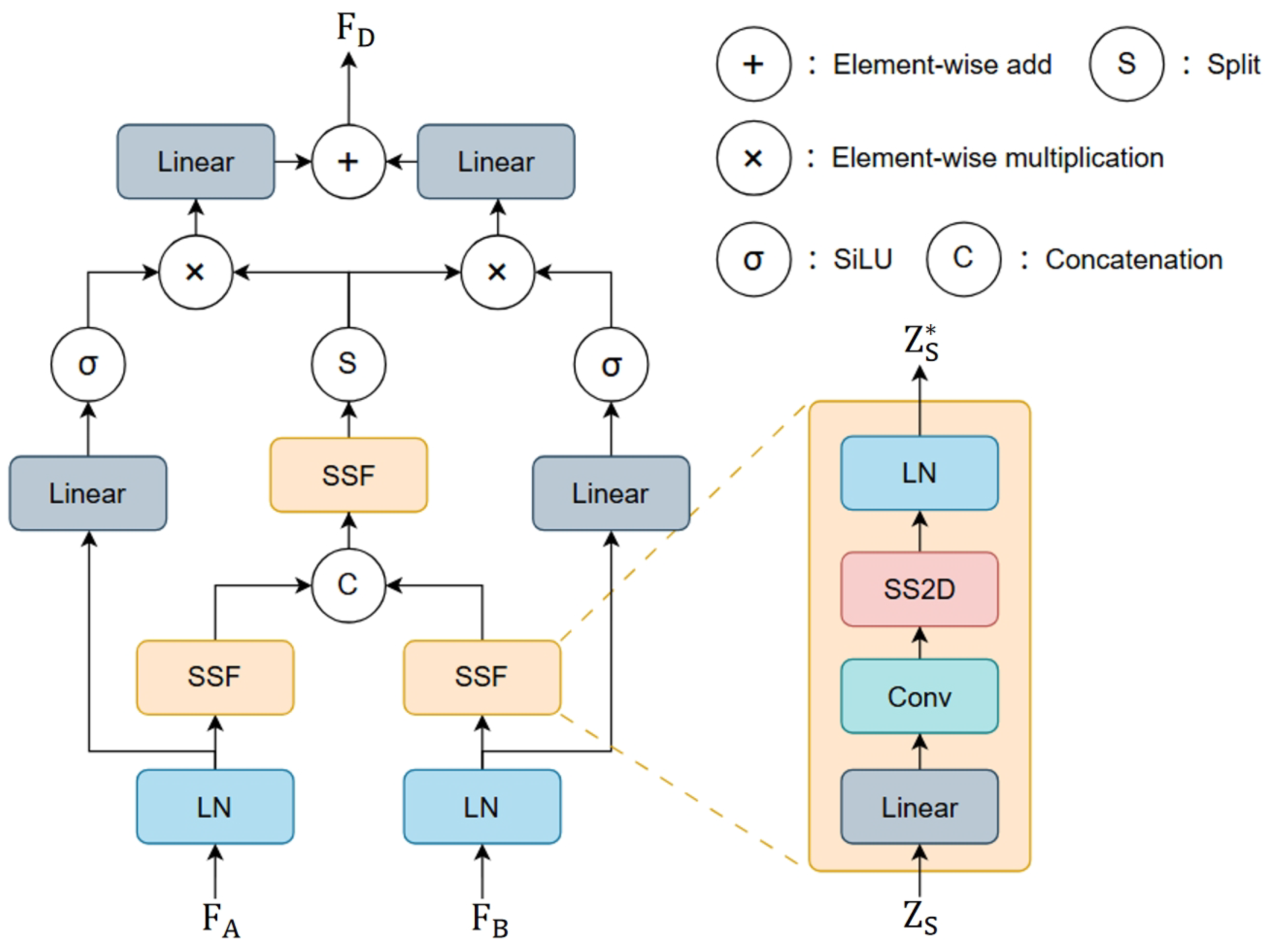

- A DualTimeMamba (DTM) module is designed. This module explicitly models long-range spatiotemporal dependencies between bi-temporal images through a two-dimensional selective scanning mechanism of the state space model, accurately capturing change regions via shared representations and temporal differences.

- (3)

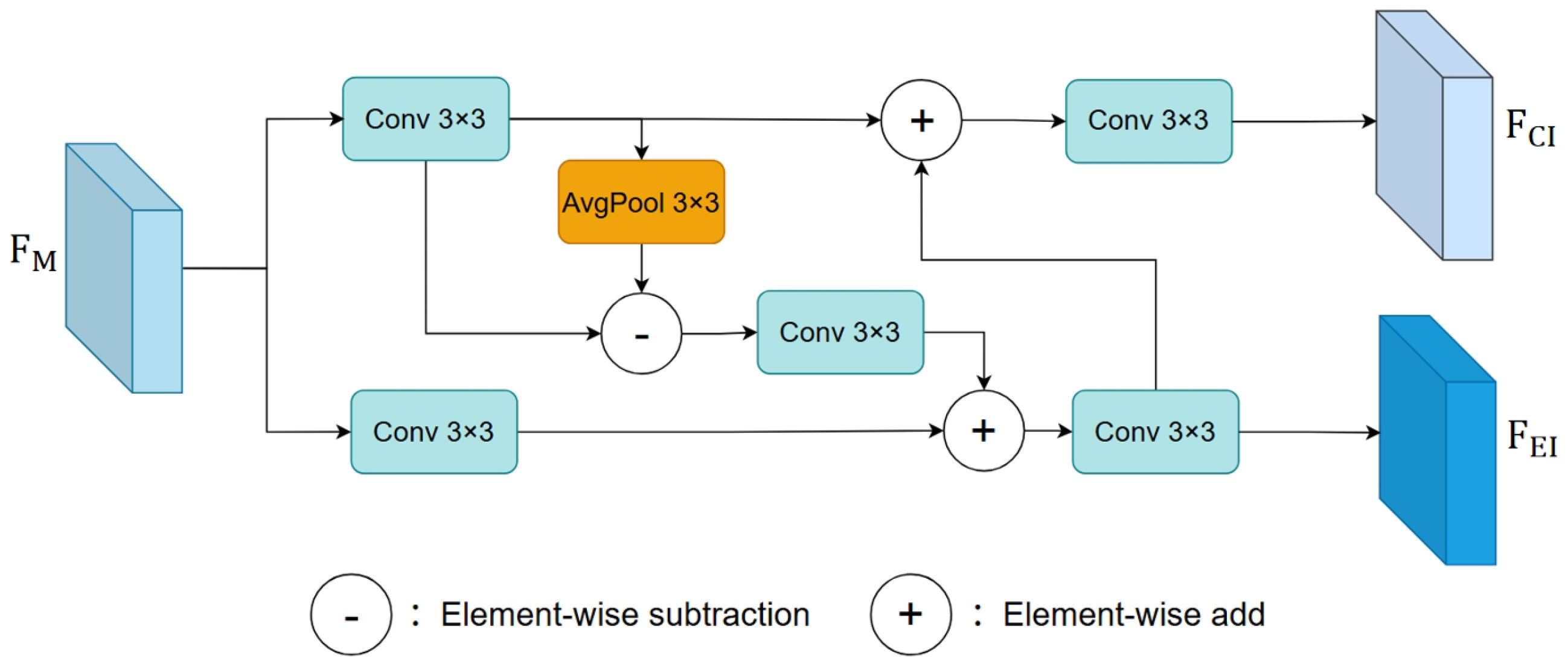

- An Edge–Change Interaction (ECI) module is proposed. By introducing edge supervision and establishing bidirectional information interaction between the change and edge branches, this module achieves joint optimization of change perception and edge extraction, improving boundary clarity.

- (4)

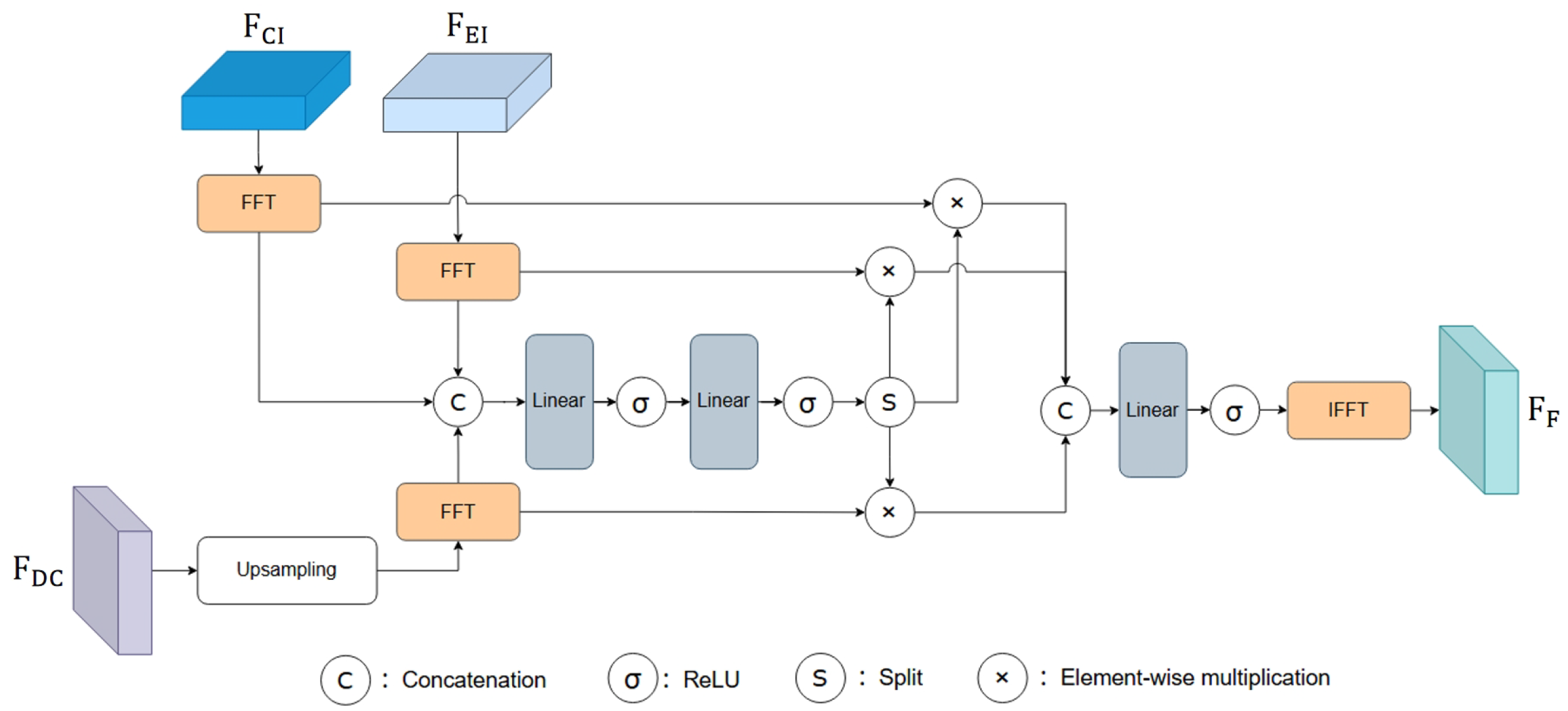

- A Frequency-domain Change Fusion (FCF) module is developed. By mapping adjacent features into the frequency domain and applying a learnable spectral modulation mechanism, this module adaptively balances low-frequency structural consistency and high-frequency detail representation.

2. Related Work

3. Methodology

3.1. Preliminaries

3.2. Overall Architecture

3.3. Dual-Time Mamba Module

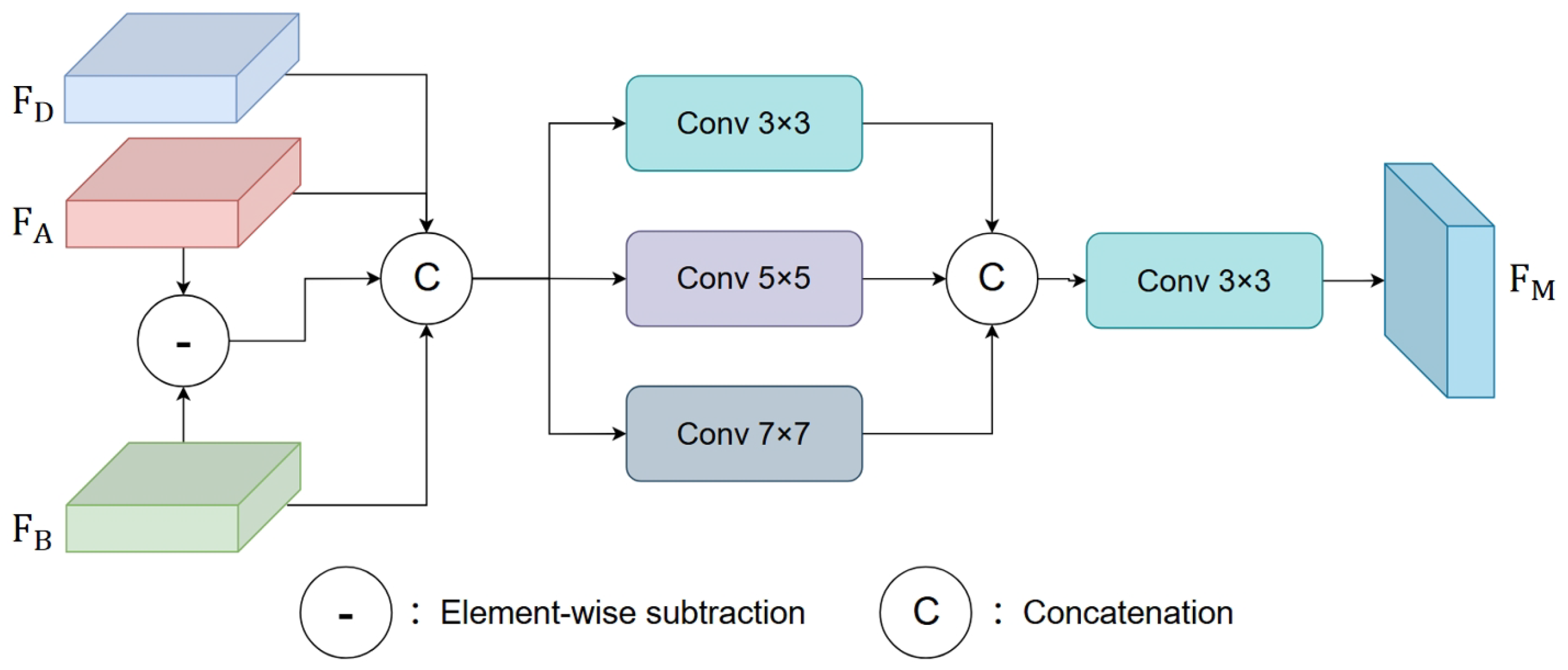

3.4. Multi-Scale Perception Module

3.5. Edge-Change Interaction Module

3.6. Frequency-Domain Change Fusion Module

4. Experiments

4.1. Datasets

4.1.1. GVLM-CD Dataset

4.1.2. WHU-CD Dataset

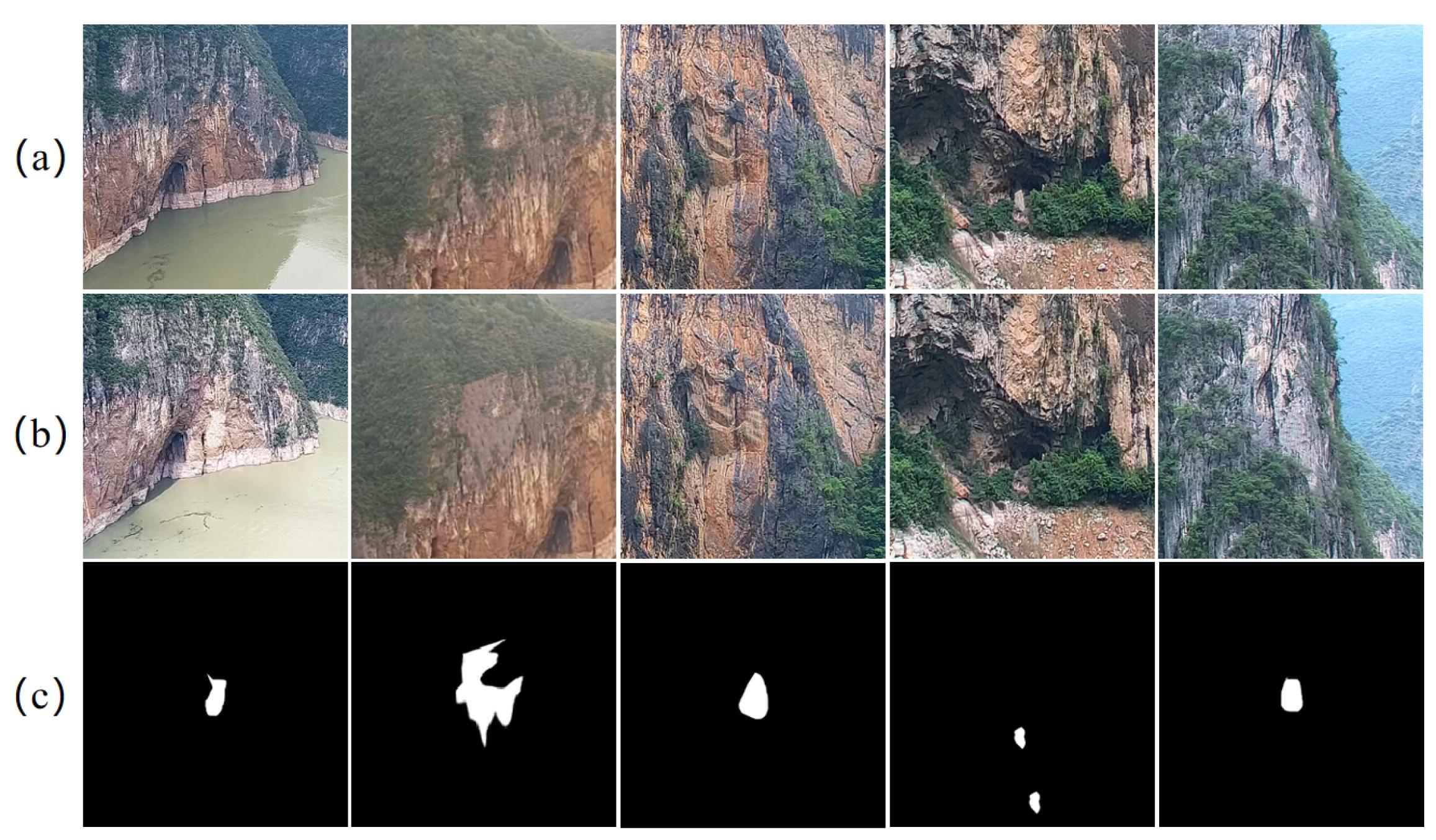

4.1.3. TGRM-CD Dataset

4.2. Experiment Setting and Evaluation Metrics

4.3. Comparison and Analysis

4.3.1. Quantitative Results

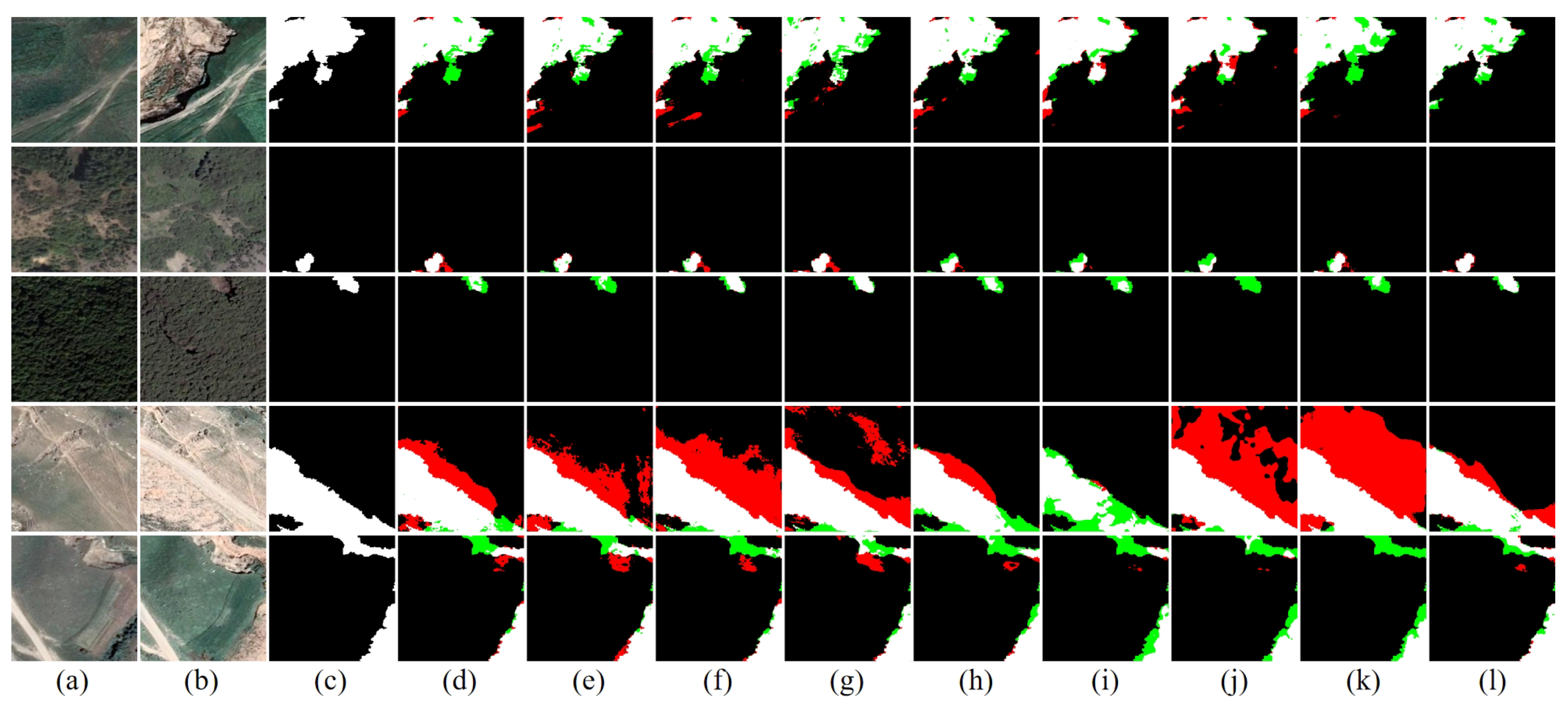

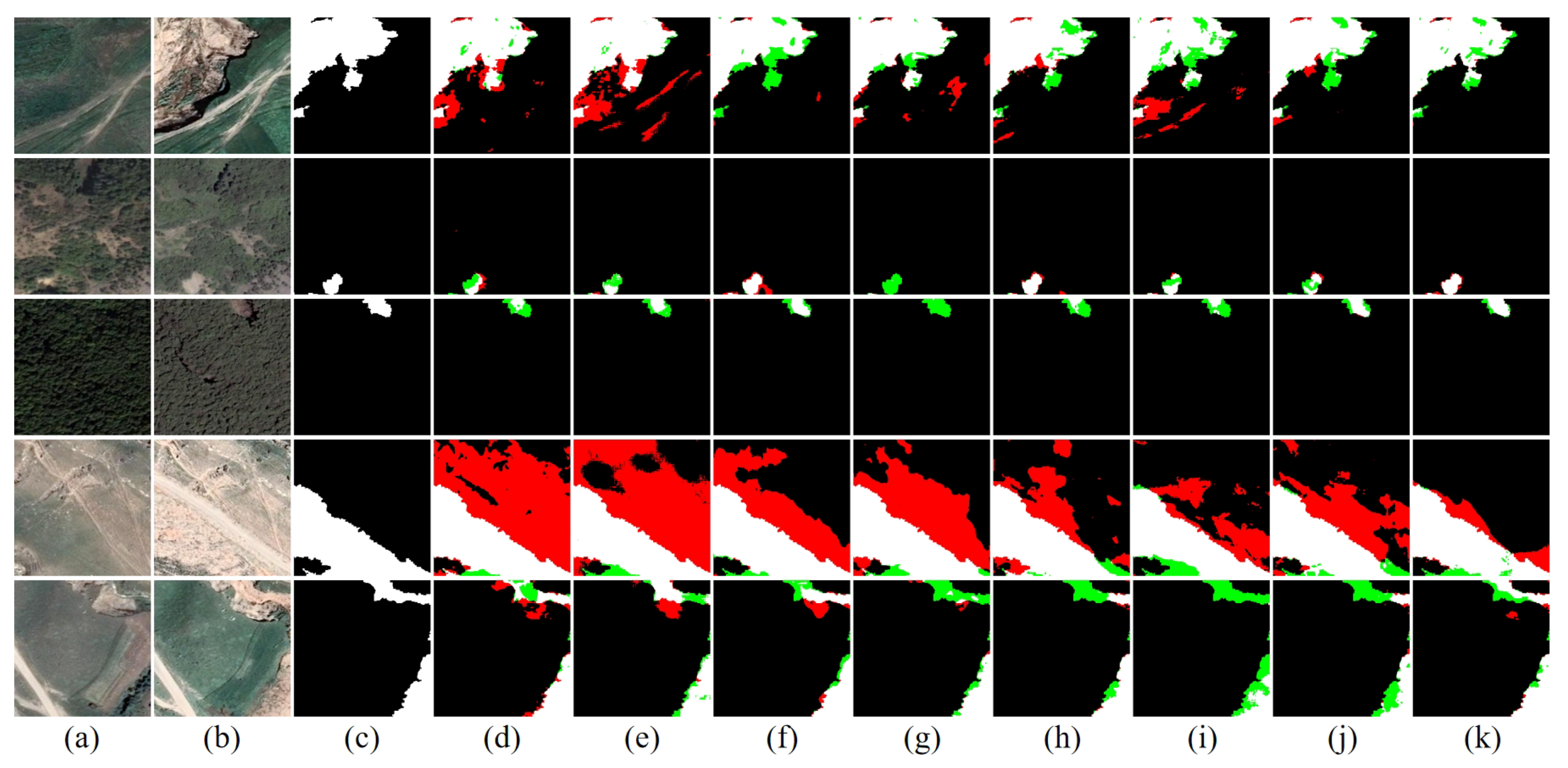

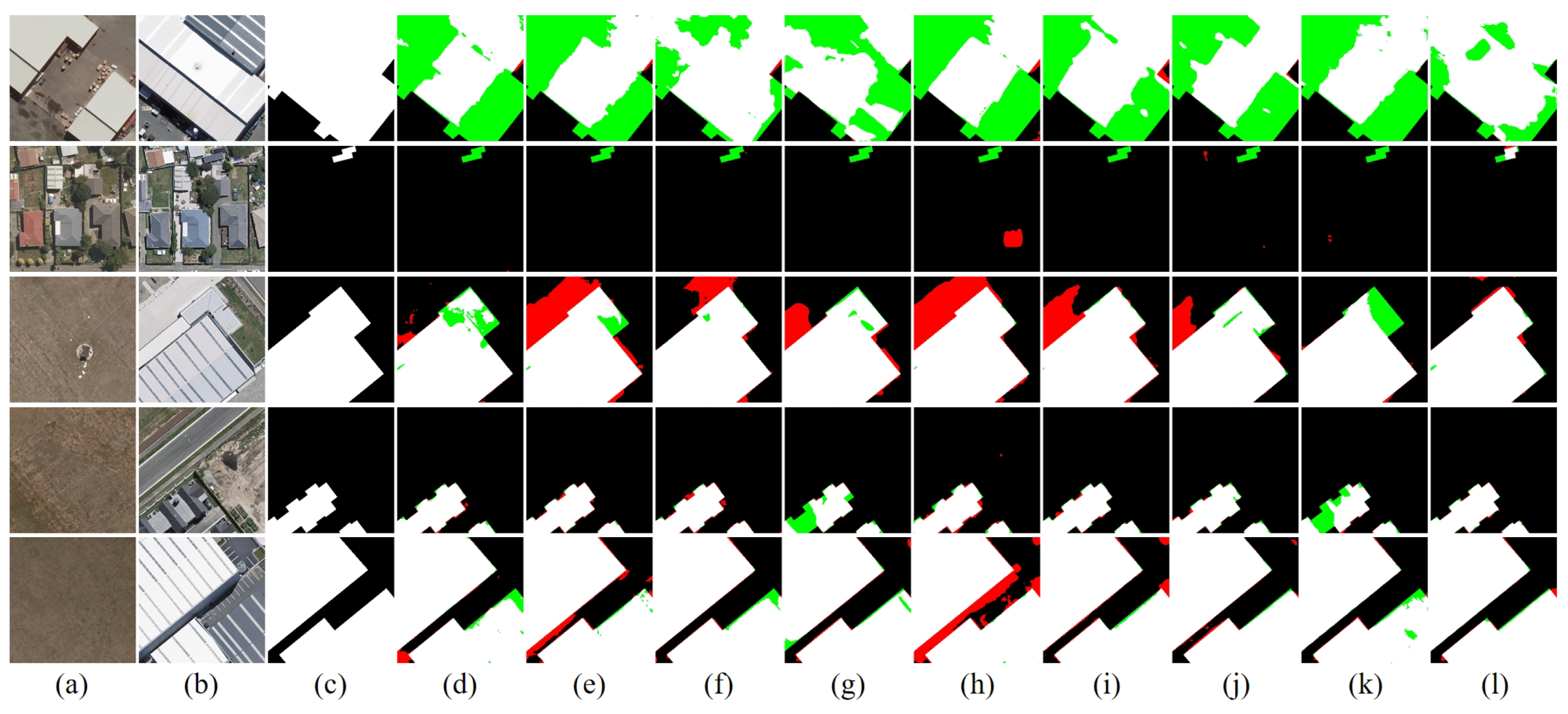

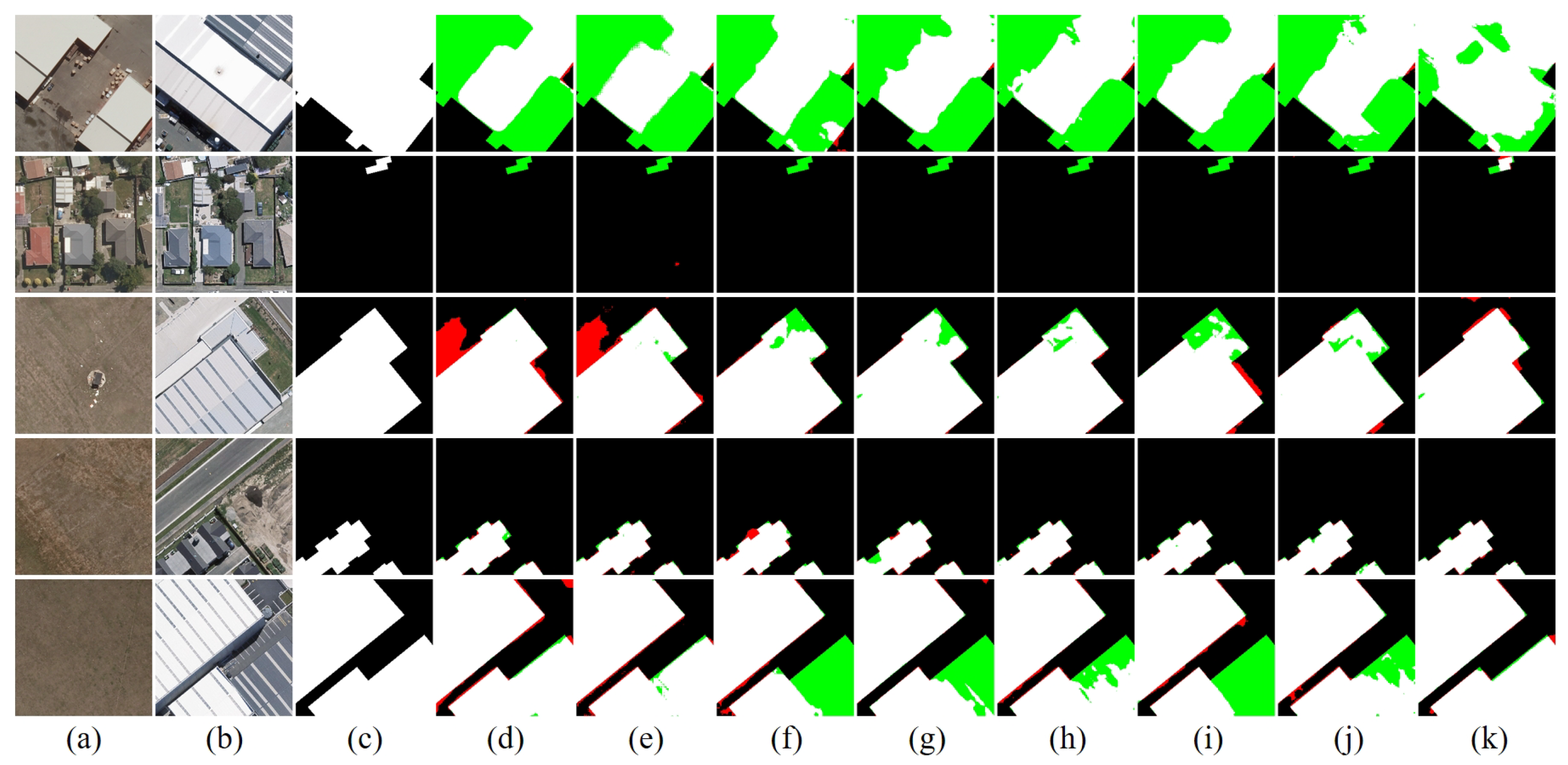

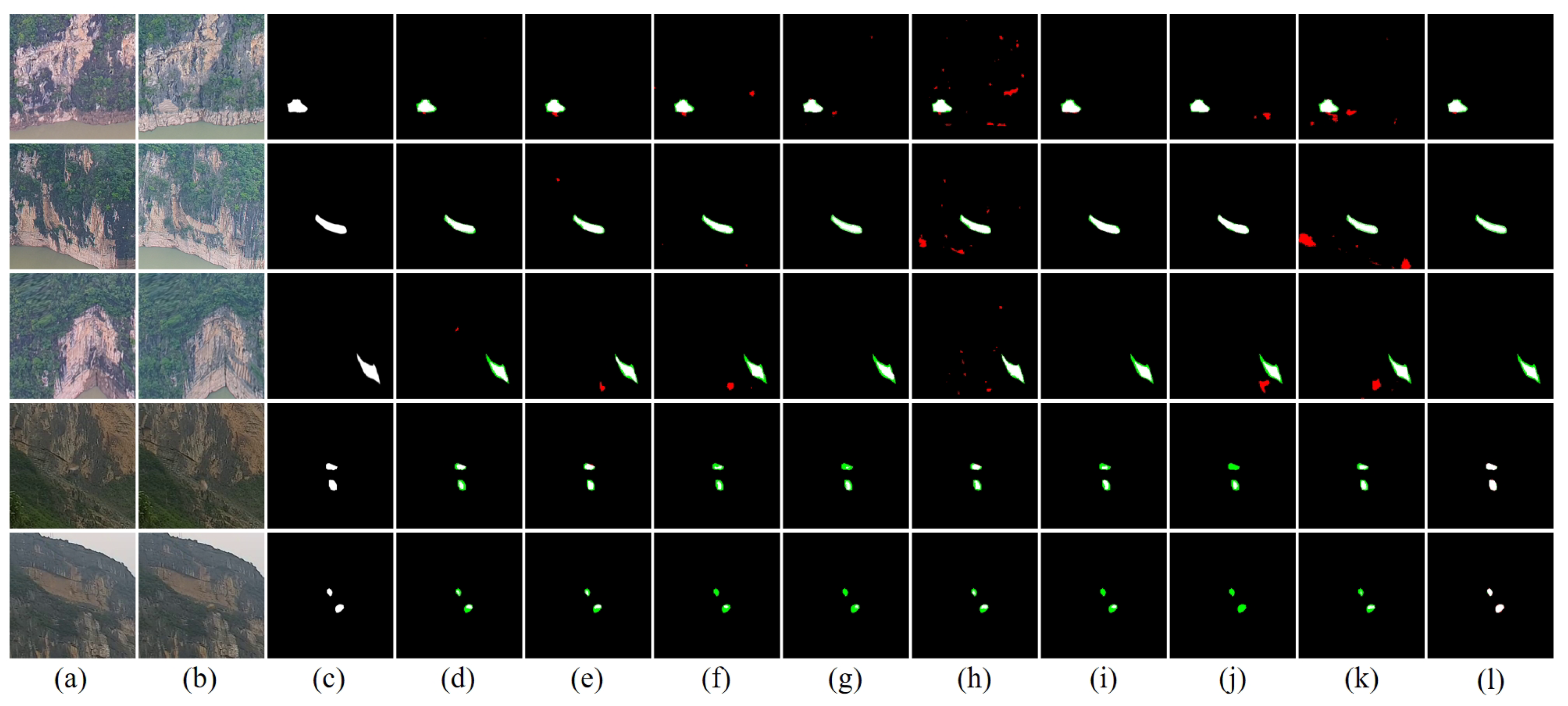

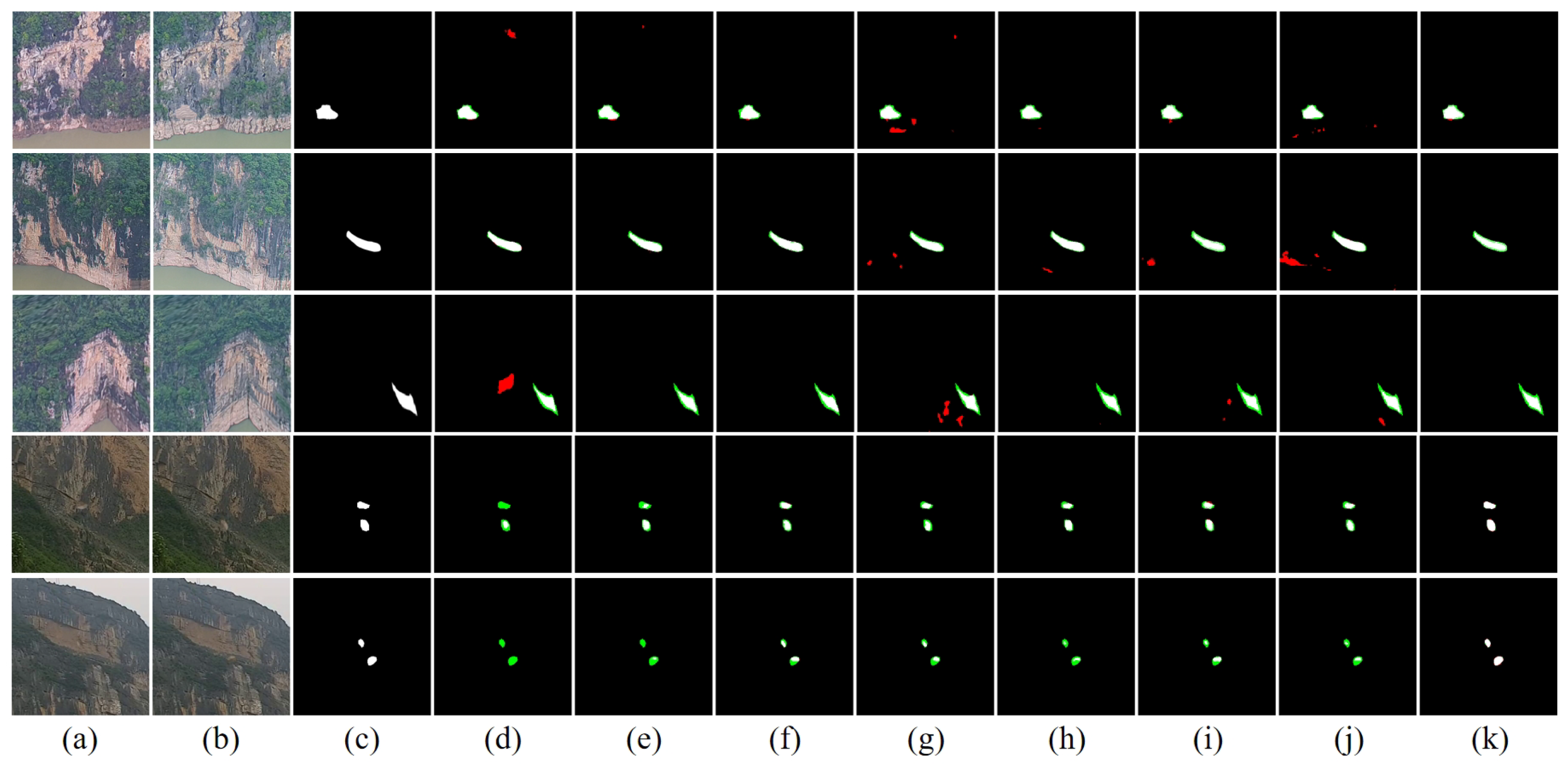

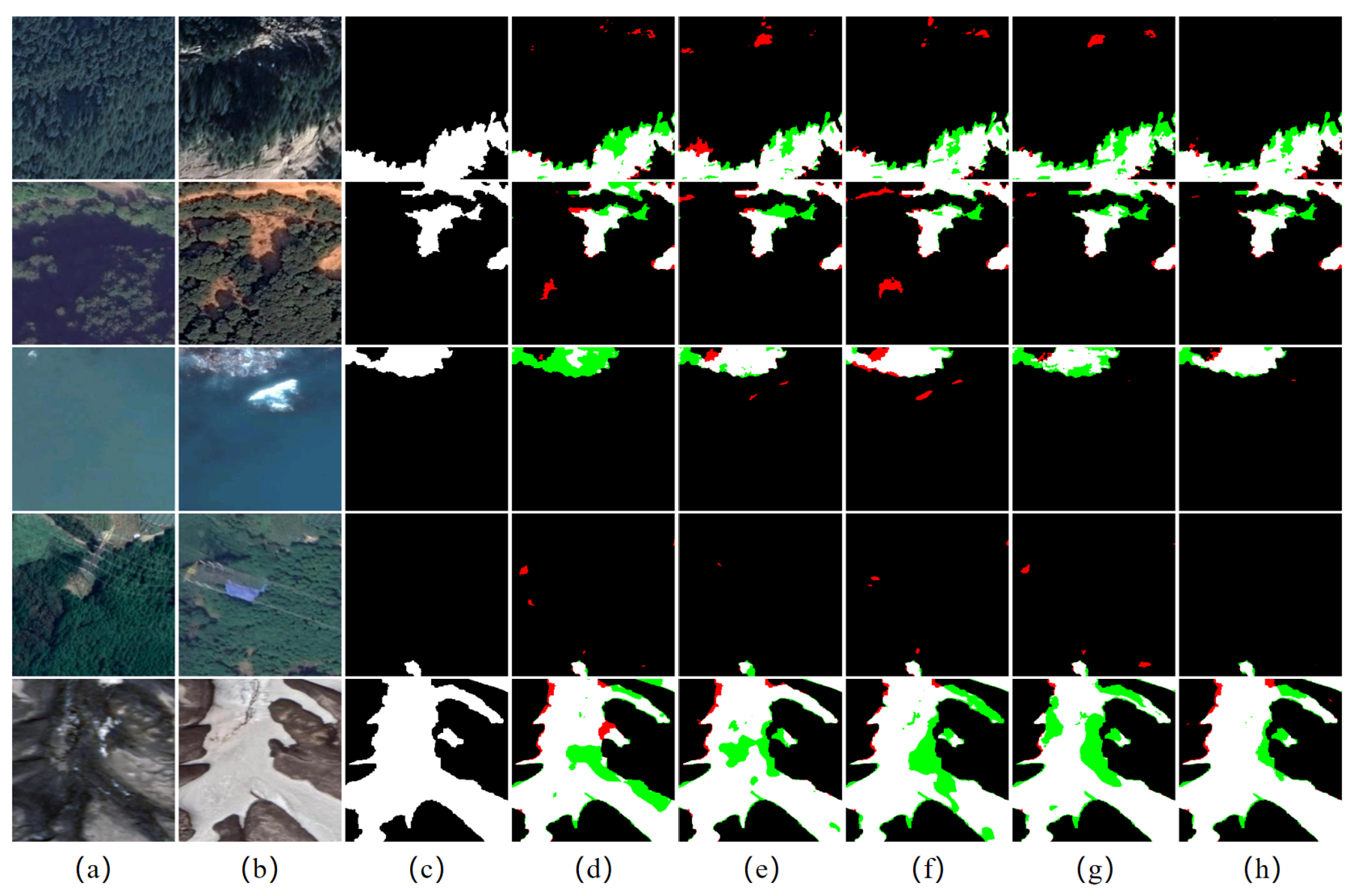

4.3.2. Qualitative Results

4.4. Ablation Studies

4.4.1. Ablation Study on Model Components

4.4.2. Ablation Study on Loss Function Coefficients

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lv, Z.; Zhang, M.; Sun, W.; Benediktsson, J.A.; Lei, T.; Falco, N. Spatial-contextual information utilization framework for land cover change detection with hyperspectral remote sensed images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 4411911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stilla, U.; Xu, Y. Change detection of urban objects using 3D point clouds: A review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2023, 197, 228–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Guo, X.; Li, Z.; Li, D. A review of multi-class change detection for satellite remote sensing imagery. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2024, 27, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strozzi, T.; Klimeš, J.; Frey, H.; Caduff, R.; Huggel, C.; Wegmüller, U.; Rapre, A.C. Satellite SAR Interferometry for the Improved Assessment of the State of Activity of Landslides: A Case Study from the Cordilleras of Peru. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 217, 111–125. [Google Scholar]

- Themistocleous, K.; Fotiou, K.; Tzouvaras, M. Monitoring natural and geo-hazards at cultural heritage sites using Earth observation: The case study of Choirokoitia, Cyprus. In Proceedings of the 25th EGU General Assembly, Vienna, Austria, 23–28 April 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, W.; Wang, F. Monitoring and analysis of coal mine surface based on unmanned aerial vehicle remote sensing. Coal Sci. Technol. 2021, 49, 268–273. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Jiang, H.; Pang, S.; Hu, X. Research status and prospects of change detection for multi-temporal remote sensing images. J. Geomatics 2022, 51, 1091–1107. [Google Scholar]

- Coppin, P.; Jonckheere, I.; Nackaerts, K.; Muys, B.; Lambin, E. Digital change detection methods in ecosystem monitoring: A review. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2004, 25, 1565–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howarth, P.J.; Wickware, G.M. Procedures for change detection using Landsat digital data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1981, 2, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Khorram, S. Quantification of the impact of misregistration on the accuracy of remotely sensed change detection. In Proceedings of the IGARSS’97: 1997 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium—Remote Sensing: A Scientific Vision for Sustainable Development, Singapore, 3–8 August 1997; pp. 1763–1765. [Google Scholar]

- Celik, T. Unsupervised change detection in satellite images using principal component analysis and k-means clustering. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2009, 6, 772–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.; Wulder, M.A.; White, J.C.; Coops, N.C.; Alvarez, M.; Butson, C. An efficient protocol to process Landsat images for change detection with tasselled cap transformation. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2007, 4, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, T.; Inglada, J.; Mercier, G.; Chanussot, J. Support vector reduction in SVM algorithm for abrupt change detection in remote sensing. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2009, 6, 606–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, K.; Sowmya, A.; Trinder, J. Building change detection from remotely sensed images based on spatial domain analysis and Markov random field. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 2019, 13, 024514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, T.; Wang, J.; Ning, H.; Wang, X.; Xue, D.; Wang, Q.; Nandi, A.K. Difference enhancement and spatial–spectral nonlocal network for change detection in VHR remote sensing images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 60, 5607713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zou, Q.; Li, G.; Yu, W.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, H. OFNet: Integrating deep optical flow and bi-domain attention for enhanced change detection. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadomanolaki, M.; Vakalopoulou, M.; Karantzalos, K. A deep multitask learning framework coupling semantic segmentation and fully convolutional LSTM networks for urban change detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 59, 7651–7668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Hang, R.; Wang, S.; Liu, Q. DiFormer: A difference transformer network for remote sensing change detection. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 6003905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xue, L.; Wang, X.; Li, G. ConvTransNet: A CNN–Transformer network for change detection with multiscale global–local representations. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5610315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Shi, Q.; Chai, Z.; Li, J. PA-Former: Learning prior-aware transformer for remote sensing building change detection. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 19, 6515305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhang, X.; Pun, M.-O. RS3Mamba: Visual state space model for remote sensing image semantic segmentation. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 6011405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Chen, B.; Liu, C.; Li, W.; Zou, Z.; Shi, Z. RSMamba: Remote sensing image classification with state space model. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 8002605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Z.; Du, B. MambaHSI: Spatial–spectral Mamba for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5538817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Yang, H.; Fu, J. Learning position-aware implicit neural network for real-world face inpainting. Pattern Recognit. 2025, 165, 111598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Zhao, X.; Xu, S.; Ren, Y.; Zheng, Y. Learning discriminative representations by a Canonical Correlation Analysis-based Siamese Network for offline signature verification. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 139, 109640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Zhu, F.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Liu, C.-L. ProtoGCD: Unified and unbiased prototype learning for generalized category discovery. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2025, 47, 6022–6038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daudt, R.C.; Le Saux, B.; Boulch, A. Fully convolutional Siamese networks for change detection. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), Valencia, Spain, 22–27 July 2018; pp. 3223–3227. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Yue, P.; Tapete, D.; Jiang, L.; Shangguan, B.; Huang, L.; Liu, G. A deeply supervised image fusion network for change detection in high-resolution bi-temporal remote sensing images. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 166, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Liu, M.; Li, S.; Liu, X.; Wang, F.; Zhang, L. A deeply supervised attention metric-based network and an open aerial image dataset for remote sensing change detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 60, 5604816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Hu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xin, Y. WRICNet: A weighted rich-scale inception coder network for remote sensing image change detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 4705313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H. CGA-Net: A CNN-GAT aggregation network based on metric for change detection in remote sensing. IEEE J. Sel. Topics Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 8360–8376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, R.; Xu, S.; Yuan, P.; Liu, Q. AANet: An ambiguity-aware network for remote-sensing image change detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5612911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Bao, L.; Zhang, Z. A spatial–temporal difference aggregation network for Gaofen-2 multitemporal image in cropland change area. IEEE J. Sel. Topics Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 3160–3172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Qi, Z.; Shi, Z. Remote sensing image change detection with transformers. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 60, 5607514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin Transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 10012–10022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, L.; Cheng, S.; Li, Y. SwinSUNet: Pure transformer network for remote sensing image change detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 60, 5224713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Chen, Y.; Dong, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H. Multi-scale fusion CNN–Transformer network for high-resolution remote sensing image change detection. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 5280–5293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Chai, Z.; Deng, H.; Liu, R. A CNN–Transformer network with multiscale context aggregation for fine-grained cropland change detection. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 4297–4306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Feng, L.; Sun, W.; Wang, L.; Yang, G.; Chen, B. A lightweight CNN-transformer network for pixel-based crop mapping using time-series Sentinel-2 imagery. Comput. Electron. Agricult. 2024, 226, 109370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Ye, T.; Yang, Y.; Liu, G.; Zhu, L. SegMamba: Long-range sequential modeling Mamba for 3D medical image segmentation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.13560. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, J.; Xiang, S. VM-UNet: Vision Mamba U-Net for medical image segmentation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.02491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, H.; Xie, L.; Wang, Y.; Ye, Q.; Liu, Y. VMamba: Visual state space model. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.10166. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, T.; Wang, S.; Wang, W.; Li, J. RS-Mamba: A state space model for remote sensing image classification. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 18, 14324–14337. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Song, J.; Han, C.; Xia, J.; Yokoya, N. ChangeMamba: Remote sensing change detection with spatiotemporal state space model. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 4409720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Ji, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Peng, J.; Li, X. Difference Enhancement and Interscale Interactive Fusion Mamba for Remote Sensing Image Change Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5651315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Jiang, K.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Lin, C.-W. Frequency-assisted Mamba for remote sensing image super-resolution. IEEE Trans. Multimedia 2025, 27, 1783–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.T. Linear System Theory and Design; Saunders College Publishing: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Hespanha, J.P. Linear Systems Theory; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, A.; Goel, K.; Re, C. Efficiently modeling long sequences with structured state spaces. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Virtual Event, 25–29 April 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, A.; Dao, T. Mamba: Linear-time sequence modeling with selective state spaces. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.00752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guibas, J.; Mardani, M.; Li, Z.; Tao, A.; Anandkumar, A.; Catanzaro, B. Adaptive Fourier neural operators: Efficient token mixers for transformers. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.13587. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Yu, W.; Pun, M.-O.; Shi, W. Cross-domain landslide mapping from large-scale remote sensing images using prototype-guided domain-aware progressive representation learning. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2023, 197, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Li, K.; Shao, J.; Li, Z. SNUNet-CD: A densely connected Siamese network for change detection of VHR images. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2021, 19, 8007805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Xia, M.; Weng, L.; Lin, H.; Huang, J.; Hu, K. Interactive and supervised dual-mode attention network for remote sensing image change detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5612818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandara, W.G.C.; Patel, V.M. A transformer-based Siamese network for change detection. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2022—IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 17–22 July 2022; pp. 207–210. [Google Scholar]

- Song, L.; Xia, M.; Weng, L.; Lin, H.; Qian, M.; Chen, B. Axial cross attention meets CNN: Bi-branch fusion network for change detection. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 16, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, K.; Liu, C.; Chen, H.; Zou, Z.; Shi, Z. CDMamba: Incorporating local clues into Mamba for remote sensing image binary change detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 4405016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Fan, X.; Wang, X.; Qin, Y.; Xia, J. A novel remote sensing image change detection approach based on multilevel state space model. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 4417014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | GVLM-CD | WHU-CD | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IoU | F1 | Pre. | Rec. | IoU | F1 | Pre. | Rec. | |

| FC-EF | 76.47 | 86.65 | 87.44 | 85.90 | 78.70 | 88.08 | 88.31 | 87.85 |

| FC-Siam-Diff | 78.09 | 87.69 | 88.13 | 87.26 | 74.75 | 85.55 | 82.59 | 88.73 |

| FC-Siam-Conc | 77.82 | 87.53 | 86.17 | 88.93 | 74.37 | 85.29 | 83.41 | 87.28 |

| IFNet | 78.30 | 87.83 | 87.53 | 88.12 | 78.59 | 88.01 | 93.73 | 82.95 |

| SNUNet | 77.68 | 87.44 | 88.42 | 86.48 | 77.61 | 87.39 | 88.37 | 86.45 |

| ISDANet | 78.28 | 87.78 | 89.64 | 86.06 | 83.74 | 91.16 | 91.11 | 91.20 |

| BIT | 78.41 | 87.90 | 89.55 | 86.31 | 81.29 | 89.72 | 91.87 | 87.59 |

| ChangeFormer | 77.96 | 87.60 | 87.26 | 87.98 | 79.18 | 88.39 | 89.30 | 87.48 |

| MSCANet | 78.30 | 87.83 | 87.97 | 87.69 | 80.57 | 89.24 | 92.81 | 85.94 |

| Paformer | 78.22 | 87.78 | 88.08 | 87.48 | 82.87 | 90.63 | 93.06 | 88.33 |

| ACABFNet | 78.41 | 87.90 | 88.00 | 87.80 | 78.92 | 88.22 | 91.62 | 85.06 |

| RS-Mamba | 79.22 | 88.41 | 89.60 | 87.25 | 81.31 | 89.69 | 93.55 | 86.14 |

| ChangeMamba | 78.80 | 88.16 | 89.23 | 87.08 | 83.65 | 91.09 | 94.52 | 87.91 |

| CDMamba | 78.46 | 87.94 | 90.15 | 85.82 | 84.11 | 91.36 | 94.06 | 88.82 |

| MF-VMamba | 79.08 | 88.32 | 89.79 | 86.89 | 83.30 | 90.89 | 93.27 | 88.62 |

| MSMCD (Ours) | 80.23 | 89.03 | 89.02 | 89.03 | 85.50 | 92.18 | 94.47 | 90.01 |

| Method | TGRM-CD | Complexity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IoU | F1 | Pre. | Rec. |

Params (M) |

FLOPs (G) | |

| FC-EF | 70.60 | 82.77 | 80.68 | 85.03 | 1.3 | 3.6 |

| FC-Siam-Diff | 72.80 | 84.26 | 81.43 | 87.28 | 1.3 | 4.7 |

| FC-Siam-Conc | 71.54 | 83.42 | 80.40 | 86.66 | 1.5 | 5.3 |

| IFNet | 73.33 | 84.60 | 83.12 | 86.15 | 35.7 | 82.3 |

| SNUNet | 73.24 | 84.53 | 83.23 | 85.92 | 12.0 | 54.8 |

| ISDANet | 75.24 | 85.86 | 85.33 | 86.42 | 6.9 | 3.5 |

| BIT | 74.27 | 85.15 | 83.4 | 87.14 | 3.5 | 8.8 |

| ChangeFormer | 73.97 | 85.05 | 84.97 | 85.11 | 41.0 | 202.8 |

| MSCANet | 74.85 | 85.54 | 84.15 | 87.12 | 16.4 | 14.8 |

| Paformer | 72.16 | 83.82 | 83.19 | 84.46 | 16.1 | 10.9 |

| ACABFNet | 73.79 | 84.99 | 86.69 | 83.22 | 102.3 | 28.3 |

| RS-Mamba | 74.82 | 85.58 | 84.49 | 86.72 | 27.9 | 15.7 |

| ChangeMamba | 75.30 | 85.71 | 84.87 | 86.98 | 49.9 | 25.8 |

| CDMamba | 75.66 | 85.99 | 85.76 | 86.52 | 11.9 | 49.6 |

| MF-VMamba | 75.21 | 85.34 | 86.16 | 85.31 | 57.8 | 25.5 |

| MSMCD (Ours) | 77.33 | 87.22 | 86.36 | 88.09 | 6.1 | 9.7 |

| Component | IoU | F1 | Pre. | Rec. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| w/o DTM | 79.23 | 88.41 | 90.15 | 86.74 |

| w/o MSP | 79.48 | 88.57 | 88.81 | 88.32 |

| w/o ECI | 79.93 | 88.85 | 88.30 | 89.41 |

| w/o FCF | 79.64 | 88.67 | 88.72 | 88.61 |

| Full (Ours) | 80.22 | 89.03 | 89.02 | 89.03 |

| IoU | F1 | Pre. | Rec. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.0 | 0.0 | 79.75 | 88.73 | 89.11 | 88.35 |

| 0.0 | 1.0 | 79.49 | 88.58 | 88.32 | 88.83 |

| 0.5 | 0.5 | 80.22 | 89.03 | 89.02 | 89.03 |

| 1.0 | 0.5 | 79.53 | 88.63 | 89.32 | 87.94 |

| 0.5 | 1.0 | 79.88 | 88.84 | 88.46 | 89.22 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Qin, L.; Zou, Q.; Li, G.; Yu, W.; Wang, L.; Chen, L.; Zhang, H. MSMCD: A Multi-Stage Mamba Network for Geohazard Change Detection. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010108

Qin L, Zou Q, Li G, Yu W, Wang L, Chen L, Zhang H. MSMCD: A Multi-Stage Mamba Network for Geohazard Change Detection. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(1):108. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010108

Chicago/Turabian StyleQin, Liwei, Quan Zou, Guoqing Li, Wenyang Yu, Lei Wang, Lichuan Chen, and Heng Zhang. 2026. "MSMCD: A Multi-Stage Mamba Network for Geohazard Change Detection" Remote Sensing 18, no. 1: 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010108

APA StyleQin, L., Zou, Q., Li, G., Yu, W., Wang, L., Chen, L., & Zhang, H. (2026). MSMCD: A Multi-Stage Mamba Network for Geohazard Change Detection. Remote Sensing, 18(1), 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010108