Figure 1.

The original image and labeled ground truth of Pavia University dataset.

Figure 1.

The original image and labeled ground truth of Pavia University dataset.

Figure 2.

The original image and labeled ground truth of Houston dataset.

Figure 2.

The original image and labeled ground truth of Houston dataset.

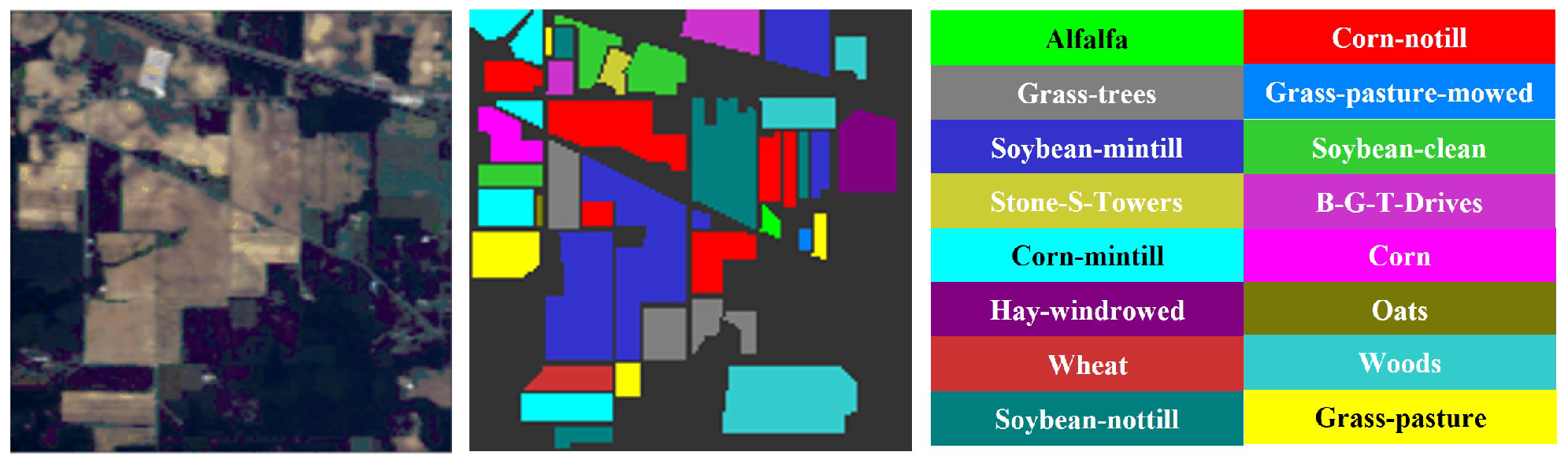

Figure 3.

The original image and labeled ground truth of Indian Pines dataset.

Figure 3.

The original image and labeled ground truth of Indian Pines dataset.

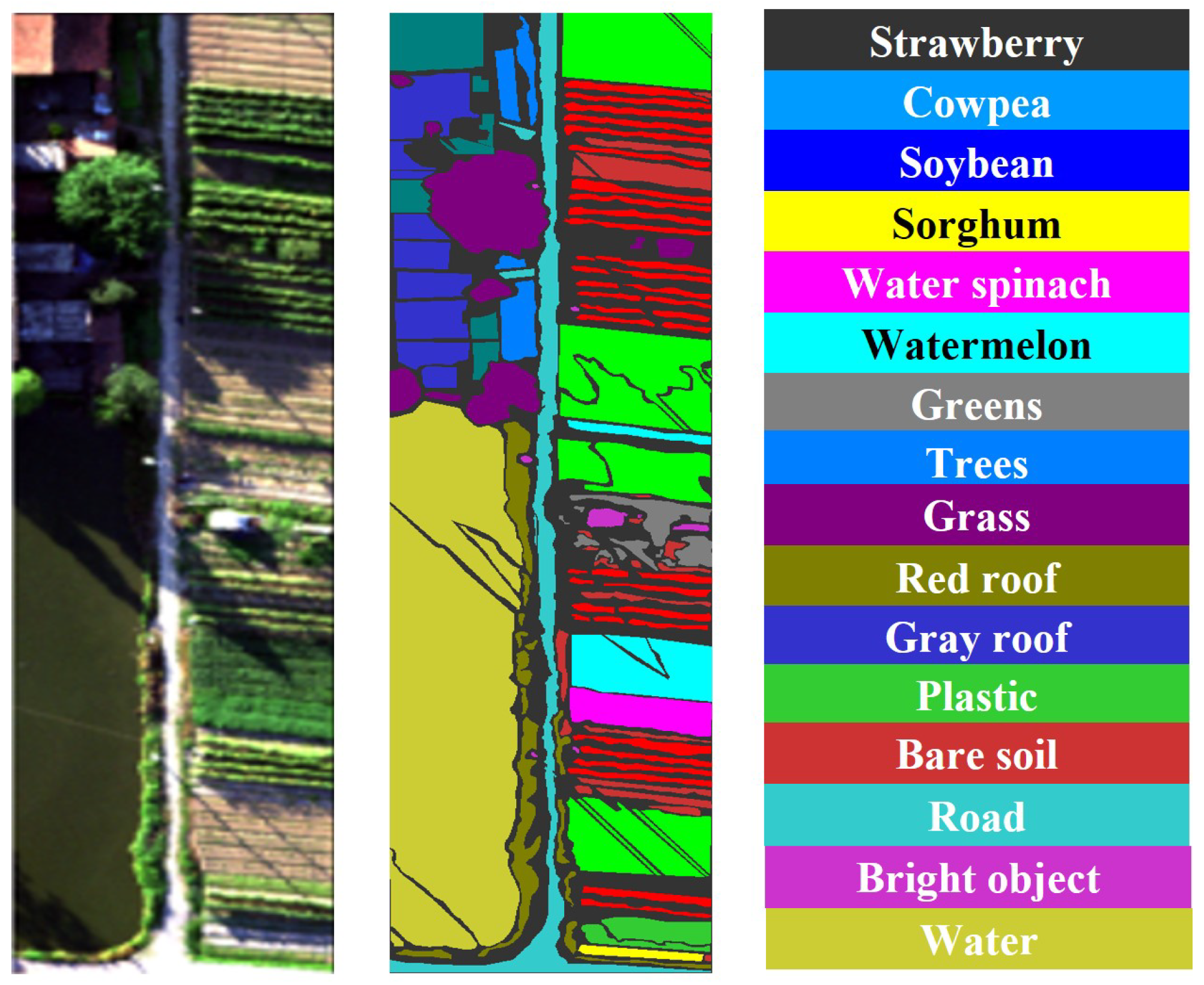

Figure 4.

The original image and labeled ground truth of WHU-Hi-HanChuan dataset.

Figure 4.

The original image and labeled ground truth of WHU-Hi-HanChuan dataset.

Figure 5.

The original image and labeled ground truth of WHU-Hi-LongKou dataset.

Figure 5.

The original image and labeled ground truth of WHU-Hi-LongKou dataset.

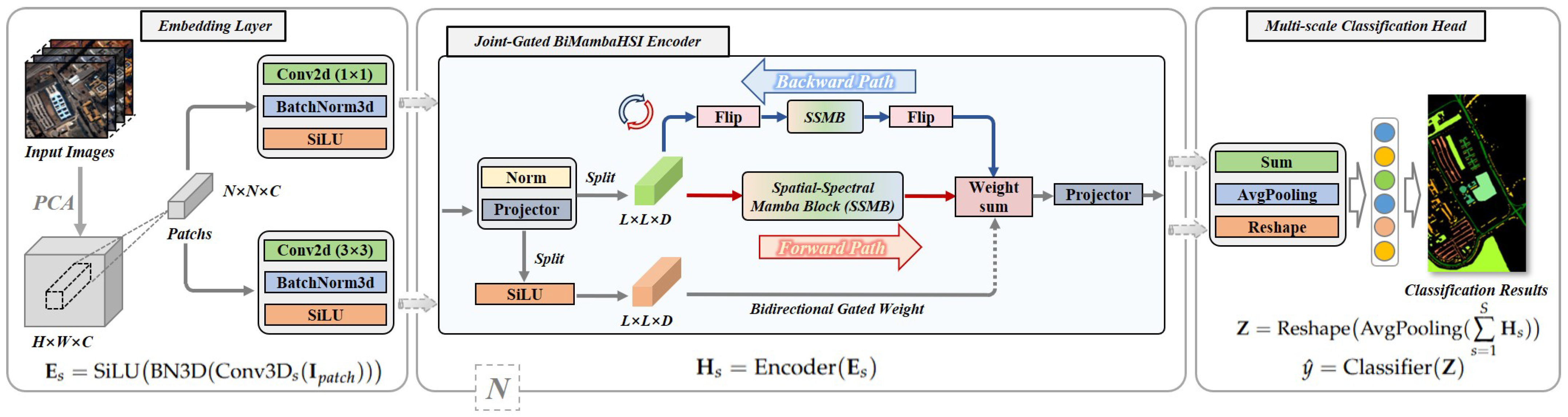

Figure 6.

Overview of the BiMambaHSI framework.

Figure 6.

Overview of the BiMambaHSI framework.

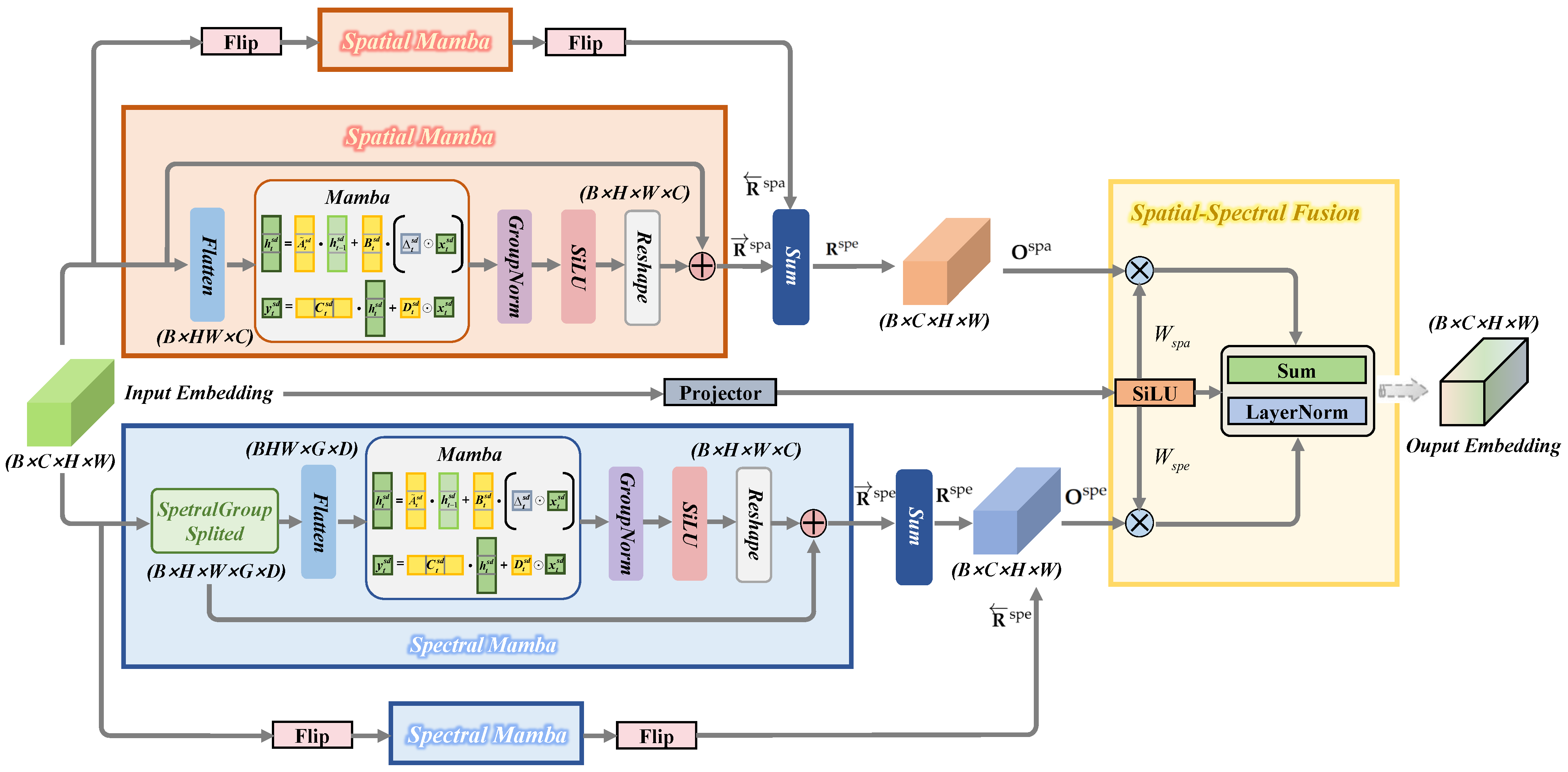

Figure 7.

Overview of the spatial—spectral Mamba block (SSMB).

Figure 7.

Overview of the spatial—spectral Mamba block (SSMB).

Figure 8.

The classification maps of all methods in the Pavia University dataset: (a) image, (b) ground Truth, (c) GSCNet, (d) HyperSIGMA, (e) Lite-HCNNet, (f) MSDAN, (g) SimpoolFormer, (h) SpectralFormer, (i) SSFTT, (j) MambaHSI, (k) HGMamba, and (l) BiMambaHSI.

Figure 8.

The classification maps of all methods in the Pavia University dataset: (a) image, (b) ground Truth, (c) GSCNet, (d) HyperSIGMA, (e) Lite-HCNNet, (f) MSDAN, (g) SimpoolFormer, (h) SpectralFormer, (i) SSFTT, (j) MambaHSI, (k) HGMamba, and (l) BiMambaHSI.

Figure 9.

The classification maps of all methods in the Houston dataset: (a) image, (b) ground truth, (c) GSCNet, (d) HyperSIGMA, (e) Lite-HCNNet, (f) MSDAN, (g) SimpoolFormer, (h) SpectralFormer, (i) SSFTT, (j) MambaHSI, (k) HGMamba, and (l) BiMambaHSI.

Figure 9.

The classification maps of all methods in the Houston dataset: (a) image, (b) ground truth, (c) GSCNet, (d) HyperSIGMA, (e) Lite-HCNNet, (f) MSDAN, (g) SimpoolFormer, (h) SpectralFormer, (i) SSFTT, (j) MambaHSI, (k) HGMamba, and (l) BiMambaHSI.

Figure 10.

The classification maps of all methods in the Indian Pines dataset: (a) image, (b) ground truth, (c) GSCNet, (d) HyperSIGMA, (e) Lite-HCNNet, (f) MSDAN, (g) SimpoolFormer, (h) SpectralFormer, (i) SSFTT, (j) MambaHSI, (k) HGMamba, and (l) BiMambaHSI.

Figure 10.

The classification maps of all methods in the Indian Pines dataset: (a) image, (b) ground truth, (c) GSCNet, (d) HyperSIGMA, (e) Lite-HCNNet, (f) MSDAN, (g) SimpoolFormer, (h) SpectralFormer, (i) SSFTT, (j) MambaHSI, (k) HGMamba, and (l) BiMambaHSI.

Figure 11.

The classification maps of all methods in the WHU-Hi-HanChuan dataset: (a) image, (b) ground truth, (c) GSCNet, (d) HyperSIGMA, (e) Lite-HCNNet, (f) MSDAN, (g) SimpoolFormer, (h) SpectralFormer, (i) SSFTT, (j) MambaHSI, (k) HGMamba, and (l) BiMambaHSI.

Figure 11.

The classification maps of all methods in the WHU-Hi-HanChuan dataset: (a) image, (b) ground truth, (c) GSCNet, (d) HyperSIGMA, (e) Lite-HCNNet, (f) MSDAN, (g) SimpoolFormer, (h) SpectralFormer, (i) SSFTT, (j) MambaHSI, (k) HGMamba, and (l) BiMambaHSI.

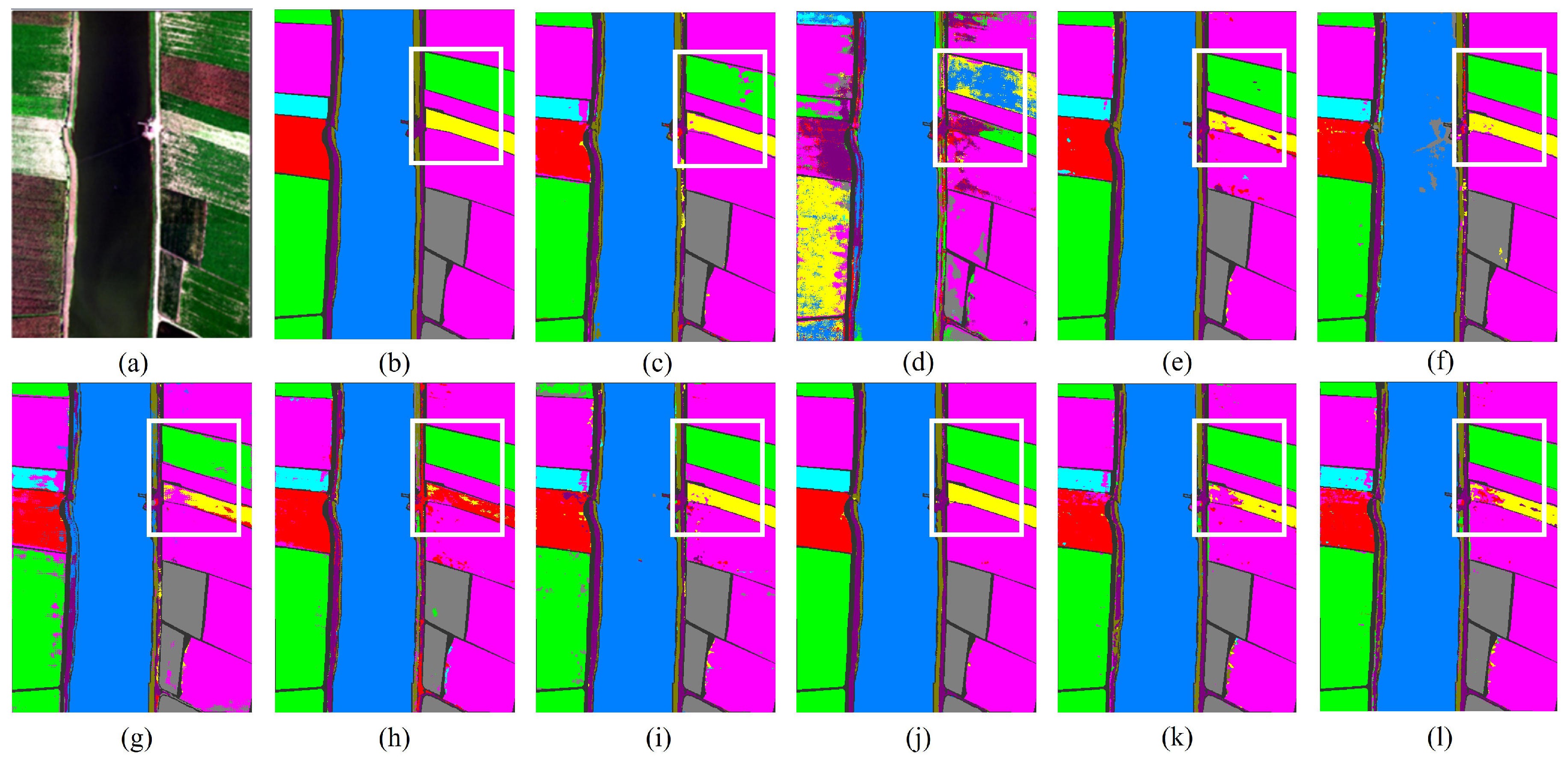

Figure 12.

The classification maps of all methods in the WHU-Hi-LongKou dataset: (a) image, (b) ground truth, (c) GSCNet, (d) HyperSIGMA, (e) Lite-HCNNet, (f) MSDAN, (g) SimpoolFormer, (h) SpectralFormer, (i) SSFTT, (j) MambaHSI, (k) HGMamba, and (l) BiMambaHSI.

Figure 12.

The classification maps of all methods in the WHU-Hi-LongKou dataset: (a) image, (b) ground truth, (c) GSCNet, (d) HyperSIGMA, (e) Lite-HCNNet, (f) MSDAN, (g) SimpoolFormer, (h) SpectralFormer, (i) SSFTT, (j) MambaHSI, (k) HGMamba, and (l) BiMambaHSI.

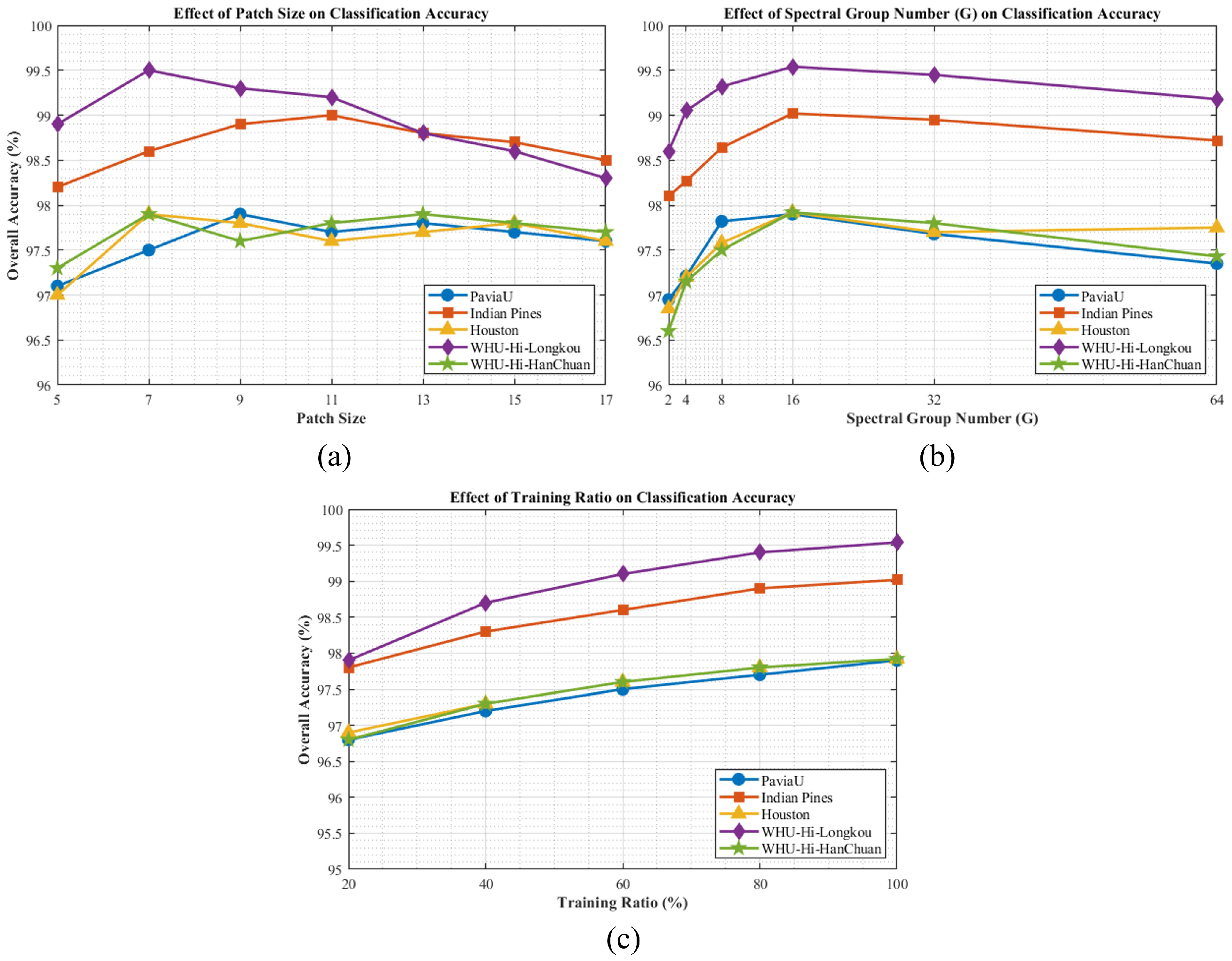

Figure 13.

Parameter sensitivity analysis of BiMambaHSI across five datasets: (a) patch size, (b) spectral group number (G), and (c) training sample ratio.

Figure 13.

Parameter sensitivity analysis of BiMambaHSI across five datasets: (a) patch size, (b) spectral group number (G), and (c) training sample ratio.

Table 1.

Number of training and testing samples for five datasets.

Table 1.

Number of training and testing samples for five datasets.

| Pavia University | Houston | WHU-Hi-HanChuan |

|---|

| Class | Number of Sample | Class | Number of Sample | Class | Number of Sample |

| No. | Name | Train | Test | No. | Name | Train | Test | No. | Name | Train | Test |

| 1 | Asphalt | 66 | 6565 | 1 | Grass healthy | 63 | 1188 | 1 | Paddy field | 2237 | 42,498 |

| 2 | Meadows | 186 | 18,463 | 2 | Grass stressed | 63 | 1191 | 2 | Irrigated field | 1138 | 21,615 |

| 3 | Gravel | 21 | 2078 | 3 | Grass synthetic | 35 | 662 | 3 | Dry cropland | 514 | 9773 |

| 4 | Trees | 31 | 3033 | 4 | Tree | 62 | 1182 | 4 | Garden plot | 268 | 5085 |

| 5 | Painted metal sheets | 13 | 1332 | 5 | Soil | 62 | 1180 | 5 | Arbor forest | 60 | 1140 |

| 6 | Bare Soil | 50 | 4979 | 6 | Water | 16 | 309 | 6 | Shrub land | 227 | 4306 |

| 7 | Bitumen | 13 | 1317 | 7 | Residential | 63 | 1205 | 7 | Natural meadow | 295 | 5608 |

| 8 | Self-Blocking Bricks | 37 | 3645 | 8 | Commercial | 62 | 1182 | 8 | Artificial meadow | 899 | 17,079 |

| 9 | Shadows | 9 | 938 | 9 | Road | 63 | 1189 | 9 | Industrial land | 473 | 8996 |

| Indian Pines | 10 | Highway | 61 | 1166 | 10 | Urban residential | 526 | 9990 |

| Class | Number of Sample | 11 | Railway | 62 | 1173 | 11 | Rural residential | 846 | 16,065 |

| No. | Name | Train | Test | 12 | Parking Lot 1 | 62 | 1171 | 12 | Traffic land | 184 | 3495 |

| 1 | Alfalfa | 5 | 41 | 13 | Parking Lot 2 | 23 | 446 | 13 | River | 456 | 8660 |

| 2 | Corn-notill | 143 | 1285 | 14 | Tennis Court | 21 | 407 | 14 | Lake | 928 | 17,632 |

| 3 | Corn-mintill | 83 | 747 | 15 | Running Track | 33 | 627 | 15 | Pond | 57 | 1079 |

| 4 | Corn | 24 | 213 | WHU-Hi-LongKou | 16 | Bare land | 3770 | 71,631 |

| 5 | Grass-pasture | 48 | 435 | Class | Number of Sample | | | | |

| 6 | Grass–trees | 73 | 657 | No. | Name | Train | Test | | | | |

| 7 | Grass–pasture–mowed | 3 | 25 | 1 | Corn | 34 | 34,477 | | | | |

| 8 | Hay-windrowed | 48 | 430 | 2 | Cotton | 8 | 8366 | | | | |

| 9 | Oats | 2 | 18 | 3 | Sesame | 3 | 3028 | | | | |

| 10 | Soybean-notill | 97 | 875 | 4 | Broad-leaf soybean | 63 | 63,149 | | | | |

| 11 | Soybean-mintill | 246 | 2209 | 5 | Narrow-leaf soybean | 4 | 4147 | | | | |

| 12 | Soybean-clean | 59 | 534 | 6 | Rice | 11 | 11,843 | | | | |

| 13 | Wheat | 21 | 184 | 7 | Water | 67 | 66,989 | | | | |

| 14 | Woods | 127 | 1138 | 8 | Roads and houses | 7 | 7117 | | | | |

| 15 | Buildings–Grass–Trees–Drives | 39 | 347 | 9 | Mixed weed | 5 | 5224 | | | | |

| 16 | Stone–Steel–Towers | 10 | 83 | | | | | | | | |

Table 2.

The ablation performance of different datasets.

Table 2.

The ablation performance of different datasets.

| Datasets | Base | JGM | SSMB | BiMambaHSI |

|---|

| Sum | Gate | Spatial | Spectral | Spatial + Spectral |

| Pavia University | 95.29 ± 0.71 | 95.36 ± 0.23 | 95.68 ± 0.68 | 95.87 ± 0.36 | 95.76 ± 0.24 | 96.14 ± 0.32 | 97.90 ± 0.11 |

| Houston | 96.75 ± 0.96 | 96.97 ± 0.57 | 97.08 ± 0.93 | 97.13 ± 0.26 | 97.30 ± 0.41 | 97.47 ± 1.04 | 97.92 ± 0.17 |

| Indian Pines | 97.83 ± 0.21 | 97.89 ± 0.62 | 98.01 ± 1.37 | 98.19 ± 0.86 | 98.17 ± 0.56 | 98.56 ± 1.10 | 99.02 ± 0.11 |

| WHU-Hi-HanChuan | 95.01 ± 0.32 | 95.37 ± 0.54 | 95.99 ± 0.21 | 96.02 ± 0.47 | 95.99 ± 0.70 | 96.52 ± 0.63 | 97.92 ± 0.27 |

| WHU-Hi-LongKou | 96.86 ± 0.45 | 96.96 ± 0.83 | 97.24 ± 1.08 | 97.76 ± 1.06 | 97.94 ± 0.79 | 98.27 ± 1.61 | 99.54 ± 0.03 |

Table 3.

The classification performance of different methods for the Pavia University dataset.

Table 3.

The classification performance of different methods for the Pavia University dataset.

| No. | GSCNet [14] | Hyper-Sigma [12] | Lite-HCNnet [11] | MSDAN [9] | Simpool-Former [30] | Spetral-Former [13] | SSFTT [31] | Mamba-HSI [20] | HG-Mamba [21] | Ours |

|---|

| 1 | 97.65 ± 0.65 | 97.08 ± 1.08 | 98.26 ± 0.77 | 95.01 ± 1.56 | 91.41 ± 2.53 | 94.25 ± 1.17 | 96.00 ± 1.25 | 96.37 ± 1.08 | 94.71 ± 0.81 | 99.07 ± 0.44 |

| 2 | 99.73 ± 0.24 | 99.39 ± 0.32 | 99.79 ± 0.13 | 99.38 ± 0.31 | 98.66 ± 0.46 | 99.27 ± 0.25 | 98.88 ± 0.68 | 99.43 ± 0.73 | 99.79 ± 0.54 | 99.85 ± 0.09 |

| 3 | 90.11 ± 9.80 | 75.44 ± 5.63 | 88.79 ± 1.99 | 87.07 ± 2.25 | 77.26 ± 5.61 | 79.00 ± 3.36 | 81.75 ± 3.56 | 85.23 ± 2.09 | 76.80 ± 2.03 | 83.92 ± 1.73 |

| 4 | 95.26 ± 1.64 | 89.49 ± 2.19 | 93.12 ± 1.64 | 90.85 ± 2.03 | 82.02 ± 3.62 | 87.02 ± 2.90 | 93.12 ± 2.25 | 91.30 ± 1.67 | 86.88 ± 1.99 | 93.72 ± 0.96 |

| 5 | 97.78 ± 2.16 | 99.70 ± 0.23 | 99.35 ± 0.27 | 98.32 ± 1.29 | 99.25 ± 1.02 | 99.43 ± 0.72 | 99.98 ± 0.04 | 97.90 ± 0.33 | 99.17 ± 0.17 | 99.85 ± 0.26 |

| 6 | 91.70 ± 6.52 | 93.08 ± 4.78 | 98.58 ± 0.81 | 98.15 ± 1.75 | 87.99 ± 1.19 | 97.25 ± 0.51 | 92.90 ± 2.83 | 94.98 ± 1.54 | 94.32 ± 1.06 | 99.76 ± 0.17 |

| 7 | 84.59 ± 3.19 | 75.28 ± 13.38 | 97.71 ± 2.00 | 98.40 ± 0.82 | 88.75 ± 3.68 | 83.75 ± 4.66 | 89.84 ± 4.23 | 96.13 ± 2.69 | 88.08 ± 3.18 | 95.78 ± 1.50 |

| 8 | 95.24 ± 3.75 | 77.88 ± 6.17 | 91.88 ± 1.56 | 89.75 ± 4.61 | 78.17 ± 6.88 | 86.61 ± 4.17 | 88.55 ± 3.84 | 86.36 ± 2.56 | 90.04 ± 1.84 | 96.32 ± 1.61 |

| 9 | 97.78 ± 1.20 | 93.32 ± 4.15 | 99.89 ± 0.11 | 89.01 ± 5.22 | 89.37 ± 7.86 | 97.29 ± 1.64 | 99.34 ± 0.83 | 95.84 ± 3.96 | 97.23 ± 4.11 | 92.27 ± 4.23 |

| OA(%) | 96.7 ± 0.79 | 93.66 ± 0.78 | 97.64 ± 0.29 | 96.22 ± 0.61 | 91.78 ± 0.47 | 94.77 ± 0.30 | 95.35 ± 0.55 | 95.8 ± 0.20 | 95.03 ± 0.17 | 97.90 ± 0.11 |

| AA(%) | 94.42 ± 1.30 | 88.85 ± 1.51 | 96.38 ± 0.45 | 93.9 ± 1.29 | 88.1 ± 0.57 | 91.54 ± 0.60 | 93.37 ± 0.52 | 93.73 ± 0.22 | 91.89 ± 0.20 | 95.62 ± 0.41 |

| Kappa | 95.61 ± 1.07 | 91.54 ± 1.04 | 96.86 ± 0.38 | 94.99 ± 0.82 | 89.01 ± 0.62 | 93.05 ± 0.40 | 93.82 ± 0.73 | 94.41 ± 0.46 | 93.36 ± 0.62 | 97.22 ± 0.15 |

Table 4.

The classification performance of different methods for the Houston dataset.

Table 4.

The classification performance of different methods for the Houston dataset.

| No. | GSCNet [14] | Hyper-Sigma [12] | Lite-HCNnet [11] | MSDAN [9] | Simpool-Former [30] | Spetral-Former [13] | SSFTT [31] | Mamba-HSI [20] | HG-Mamba [21] | Ours |

|---|

| 1 | 89.56 ± 6.50 | 95.32 ± 1.91 | 91.65 ± 2.33 | 96.94 ± 0.75 | 95.77 ± 1.49 | 97.84 ± 0.37 | 98.10 ± 1.28 | 87.54 ± 1.84 | 95.29 ± 1.79 | 98.62 ± 1.01 |

| 2 | 94.98 ± 4.73 | 96.47 ± 1.30 | 98.55 ± 0.34 | 98.66 ± 0.80 | 98.54 ± 1.18 | 98.20 ± 0.33 | 99.13 ± 0.15 | 99.92 ± 0.31 | 99.24 ± 0.29 | 99.06 ± 0.20 |

| 3 | 99.76 ± 0.46 | 99.79 ± 0.13 | 99.86 ± 0.32 | 99.94 ± 0.08 | 100.0 ± 0.00 | 100.0 ± 0.00 | 99.94 ± 0.13 | 99.70 ± 0.61 | 99.70 ± 0.37 | 100.00 ± 0.00 |

| 4 | 90.59 ± 7.37 | 97.59 ± 1.36 | 98.83 ± 1.10 | 98.65 ± 0.62 | 98.21 ± 1.86 | 99.85 ± 0.20 | 99.81 ± 0.17 | 99.32 ± 1.03 | 97.12 ± 0.76 | 98.97 ± 1.36 |

| 5 | 99.36 ± 0.7 | 99.87 ± 0.21 | 98.65 ± 0.94 | 99.97 ± 0.08 | 99.85 ± 0.11 | 99.98 ± 0.04 | 99.83 ± 0.22 | 100.00 ± 0.00 | 100.00 ± 0.00 | 100.0 ± 0.00 |

| 6 | 88.48 ± 9.43 | 89.53 ± 5.04 | 84.66 ± 3.70 | 99.35 ± 0.91 | 94.04 ± 5.12 | 90.74 ± 0.88 | 96.31 ± 3.09 | 98.06 ± 2.19 | 100.00 ± 0.00 | 97.80 ± 2.72 |

| 7 | 91.55 ± 1.74 | 92.42 ± 1.80 | 91.75 ± 1.60 | 95.42 ± 1.61 | 91.60 ± 3.73 | 92.51 ± 3.17 | 94.84 ± 1.94 | 93.03 ± 1.09 | 93.28 ± 1.41 | 93.14 ± 0.71 |

| 8 | 84.35 ± 2.78 | 86.5 ± 1.76 | 73.69 ± 5.50 | 96.19 ± 0.98 | 92.78 ± 2.17 | 94.35 ± 1.21 | 93.00 ± 1.19 | 97.97 ± 1.22 | 95.94 ± 1.05 | 95.84 ± 0.81 |

| 9 | 87.67 ± 4.29 | 79.74 ± 1.75 | 81.07 ± 5.66 | 94.84 ± 1.72 | 90.60 ± 4.00 | 96.81 ± 1.88 | 95.11 ± 0.69 | 96.38 ± 2.43 | 96.97 ± 2.90 | 97.34 ± 0.50 |

| 10 | 92.13 ± 4.79 | 91.1 ± 1.38 | 94.01 ± 1.54 | 97.22 ± 1.04 | 98.08 ± 0.94 | 99.33 ± 0.52 | 95.75 ± 1.09 | 99.40 ± 1.17 | 95.54 ± 1.75 | 99.21 ± 0.76 |

| 11 | 88.53 ± 2.53 | 97.67 ± 1.22 | 89.30 ± 4.25 | 98.88 ± 0.92 | 94.10 ± 6.38 | 98.13 ± 0.87 | 97.87 ± 1.17 | 91.30 ± 3.02 | 88.32 ± 2.54 | 98.71 ± 0.70 |

| 12 | 89.5 ± 4.07 | 94.44 ± 3.34 | 83.75 ± 5.71 | 96.09 ± 0.82 | 95.30 ± 2.94 | 98.23 ± 0.72 | 98.36 ± 0.90 | 97.10 ± 0.09 | 97.27 ± 0.19 | 98.91 ± 0.48 |

| 13 | 81.03 ± 10.11 | 87.00 ± 4.73 | 86.29 ± 5.87 | 94.8 ± 4.31 | 52.42 ± 13.64 | 73.32 ± 4.35 | 93.41 ± 2.92 | 95.74 ± 2.77 | 91.26 ± 3.04 | 89.28 ± 2.32 |

| 14 | 97.79 ± 2.78 | 100.0 ± 0.00 | 98.54 ± 1.07 | 99.75 ± 0.17 | 99.80 ± 0.44 | 99.51 ± 0.46 | 99.31 ± 0.27 | 100.00 ± 0.00 | 100.00 ± 0.00 | 99.70 ± 0.20 |

| 15 | 98.95 ± 1.15 | 99.97 ± 0.07 | 99.54 ± 0.47 | 100.0 ± 0.00 | 99.23 ± 0.61 | 99.84 ± 0.28 | 99.42 ± 0.63 | 100.00 ± 0.00 | 100.00 ± 0.00 | 99.81 ± 0.26 |

| OA(%) | 91.44 ± 0.24 | 93.64 ± 0.22 | 90.99 ± 0.67 | 97.56 ± 0.22 | 94.59 ± 0.51 | 96.88 ± 0.49 | 97.33 ± 0.39 | 96.65 ± 0.27 | 96.32 ± 0.53 | 97.92 ± 0.17 |

| AA(%) | 91.62 ± 0.72 | 93.83 ± 0.24 | 91.34 ± 0.74 | 97.78 ± 0.31 | 93.35 ± 0.79 | 95.91 ± 0.49 | 97.35 ± 0.56 | 97.03 ± 0.21 | 96.66 ± 0.49 | 97.76 ± 0.30 |

| Kappa | 90.74 ± 0.26 | 93.13 ± 0.24 | 90.26 ± 0.72 | 97.36 ± 0.24 | 94.15 ± 0.55 | 96.63 ± 0.53 | 97.11 ± 0.42 | 96.38 ± 0.50 | 96.02 ± 0.37 | 97.75 ± 0.19 |

Table 5.

The classification performance of different methods for the Indian Pines dataset.

Table 5.

The classification performance of different methods for the Indian Pines dataset.

| No. | GSCNet [14] | Hyper-Sigma [12] | Lite-HCNnet [11] | MSDAN [9] | Simpool-Former [30] | Spetral-Former [13] | SSFTT [31] | Mamba-HSI [20] | HG-Mamba [21] | Ours |

|---|

| 1 | 99.46 ± 1.01 | 95.61 ± 4.36 | 99.46 ± 1.21 | 98.38 ± 2.42 | 90.81 ± 10.22 | 98.38 ± 1.48 | 89.52 ± 7.64 | 90.91 ± 2.37 | 97.73 ± 2.40 | 98.92 ± 1.48 |

| 2 | 94.98 ± 0.78 | 90.46 ± 1.58 | 96.49 ± 1.27 | 97.52 ± 0.76 | 92.81 ± 0.69 | 93.21 ± 1.19 | 97.48 ± 0.38 | 95.65 ± 0.91 | 95.50 ± 0.79 | 97.88 ± 0.87 |

| 3 | 97.59 ± 2.08 | 95.82 ± 1.86 | 99.49 ± 0.38 | 98.55 ± 0.57 | 95.24 ± 1.25 | 97.74 ± 0.74 | 97.09 ± 0.91 | 98.99 ± 0.26 | 97.97 ± 0.73 | 98.28 ± 0.46 |

| 4 | 98.32 ± 1.26 | 93.71 ± 1.87 | 98.42 ± 3.53 | 99.68 ± 0.47 | 86.84 ± 3.63 | 91.89 ± 1.60 | 97.16 ± 2.04 | 93.78 ± 2.15 | 95.56 ± 2.09 | 100.00 ± 0.00 |

| 5 | 96.79 ± 1.84 | 93.93 ± 1.18 | 98.91 ± 0.64 | 97.82 ± 1.09 | 96.79 ± 1.03 | 94.71 ± 2.20 | 95.23 ± 0.74 | 100.00 ± 0.00 | 100.00 ± 0.00 | 99.58 ± 0.51 |

| 6 | 98.77 ± 0.99 | 99.03 ± 0.32 | 99.35 ± 0.59 | 98.94 ± 0.52 | 99.21 ± 0.58 | 99.83 ± 0.17 | 97.05 ± 0.78 | 98.70 ± 0.36 | 97.26 ± 0.52 | 99.32 ± 0.40 |

| 7 | 100.00 ± 0.00 | 80.0 ± 18.55 | 94.54 ± 3.80 | 99.93 ± 0.15 | 81.82 ± 14.37 | 98.18 ± 2.49 | 88.46 ± 6.08 | 92.59 ± 3.10 | 70.37 ± 3.47 | 100.00 ± 0.00 |

| 8 | 99.27 ± 1.36 | 100.00 ± 0.00 | 99.69 ± 0.47 | 99.69 ± 0.7 | 99.63 ± 0.54 | 100.00 ± 0.00 | 99.91 ± 0.20 | 100.00 ± 0.00 | 100.00 ± 0.00 | 100.00 ± 0.00 |

| 9 | 78.75 ± 19.06 | 45.56 ± 9.13 | 87.5 ± 17.68 | 87.50 ± 4.42 | 86.25 ± 6.85 | 97.5 ± 3.42 | 90.00 ± 7.24 | 73.68 ± 4.92 | 36.84 ± 8.78 | 100.00 ± 0.00 |

| 10 | 96.38 ± 1.34 | 91.98 ± 2.42 | 98.15 ± 1.91 | 98.79 ± 1.2 | 93.22 ± 1.11 | 95.55 ± 1.16 | 93.89 ± 1.43 | 97.62 ± 0.58 | 98.70 ± 0.31 | 98.79 ± 0.68 |

| 11 | 98.61 ± 0.38 | 97.31 ± 0.92 | 99.09 ± 0.27 | 98.83 ± 0.66 | 98.56 ± 0.48 | 98.68 ± 0.17 | 97.77 ± 0.46 | 98.28 ± 0.40 | 97.51 ± 0.23 | 99.85 ± 0.12 |

| 12 | 97.31 ± 1.54 | 89.17 ± 1.94 | 97.26 ± 1.31 | 95.92 ± 1.43 | 92.55 ± 3.12 | 95.11 ± 1.44 | 96.01 ± 2.25 | 92.90 ± 2.79 | 90.59 ± 2.47 | 95.96 ± 1.68 |

| 13 | 98.78 ± 2.73 | 99.14 ± 0.3 | 99.51 ± 0.67 | 100.00 ± 0.0 | 99.63 ± 0.33 | 100.0 ± 0.00 | 98.09 ± 1.57 | 97.44 ± 1.09 | 96.92 ± 1.38 | 100.00 ± 0.00 |

| 14 | 99.76 ± 0.20 | 99.86 ± 0.12 | 99.92 ± 0.13 | 99.84 ± 0.11 | 99.23 ± 0.36 | 99.21 ± 0.34 | 99.26 ± 0.27 | 99.00 ± 0.03 | 98.50 ± 0.07 | 99.98 ± 0.04 |

| 15 | 97.86 ± 0.96 | 97.46 ± 1.25 | 99.16 ± 0.85 | 99.48 ± 0.59 | 96.83 ± 1.92 | 97.35 ± 1.69 | 90.48 ± 2.07 | 93.19 ± 2.84 | 94.01 ± 2.57 | 99.68 ± 0.23 |

| 16 | 98.92 ± 1.13 | 79.29 ± 10.47 | 98.11 ± 1.54 | 96.49 ± 3.39 | 97.30 ± 1.91 | 94.86 ± 4.21 | 80.23 ± 2.10 | 64.77 ± 2.90 | 85.23 ± 4.03 | 91.62 ± 3.50 |

| OA(%) | 97.77 ± 0.19 | 95.3 ± 0.79 | 98.66 ± 0.44 | 98.62 ± 0.24 | 96.30 ± 0.41 | 97.14 ± 0.27 | 96.80 ± 0.21 | 97.17 ± 0.27 | 96.84 ± 0.44 | 99.02 ± 0.11 |

| AA(%) | 96.97 ± 1.36 | 90.52 ± 1.98 | 97.82 ± 0.94 | 97.92 ± 0.45 | 94.17 ± 1.59 | 97.01 ± 0.32 | 94.23 ± 1.28 | 92.97 ± 0.74 | 90.79 ± 0.98 | 98.74 ± 0.32 |

| Kappa | 97.46 ± 0.22 | 94.64 ± 0.9 | 98.47 ± 0.51 | 98.42 ± 0.28 | 95.78 ± 0.46 | 96.74 ± 0.31 | 96.35 ± 0.23 | 96.76 ± 0.42 | 96.38 ± 0.37 | 98.88 ± 0.13 |

Table 6.

The classification performance of different methods for the WHU-Hi-HanChuan dataset.

Table 6.

The classification performance of different methods for the WHU-Hi-HanChuan dataset.

| No. | GSCNet [14] | Hyper-Sigma [12] | Lite-HCNnet [11] | MSDAN [9] | Simpool-Former [30] | Spetral-Former [13] | SSFTT [31] | Mamba-HSI [20] | HG-Mamba [21] | Ours |

|---|

| 1 | 97.13 ± 1.53 | 97.62 ± 0.49 | 97.62 ± 0.48 | 97.93 ± 0.23 | 98.85 ± 1.23 | 98.32 ± 0.52 | 97.21 ± 1.05 | 97.64 ± 0.94 | 97.74 ± 1.03 | 99.22 ± 0.26 |

| 2 | 92.02 ± 2.91 | 95.27 ± 4.44 | 93.56 ± 1.16 | 94.96 ± 1.31 | 95.47 ± 3.95 | 94.95 ± 0.95 | 93.21 ± 1.55 | 90.90 ± 2.87 | 92.14 ± 1.33 | 96.97 ± 0.80 |

| 3 | 93.91 ± 4.79 | 95.58 ± 2.02 | 94.30 ± 3.36 | 95.78 ± 1.38 | 96.01 ± 3.30 | 97.00 ± 1.09 | 91.96 ± 2.30 | 95.83 ± 1.89 | 96.07 ± 1.02 | 97.91 ± 0.68 |

| 4 | 97.24 ± 1.38 | 99.33 ± 0.36 | 97.81 ± 0.43 | 98.79 ± 0.62 | 99.48 ± 1.45 | 98.31 ± 0.49 | 98.12 ± 0.74 | 98.84 ± 0.95 | 98.00 ± 1.22 | 99.24 ± 0.63 |

| 5 | 67.58 ± 14.66 | 66.75 ± 4.76 | 85.74 ± 5.67 | 76.0 ± 14.93 | 85.75 ± 9.58 | 90.28 ± 3.53 | 75.19 ± 8.21 | 91.14 ± 2.37 | 68.21 ± 4.98 | 91.74 ± 3.45 |

| 6 | 65.97 ± 5.30 | 67.91 ± 2.49 | 63.76 ± 7.02 | 73.56 ± 4.11 | 78.36 ± 10.43 | 68.04 ± 3.94 | 68.24 ± 6.49 | 72.16 ± 2.01 | 70.96 ± 2.09 | 88.33 ± 1.34 |

| 7 | 81.67 ± 12.06 | 89.16 ± 0.73 | 86.91 ± 7.36 | 87.75 ± 7.64 | 92.48 ± 3.60 | 92.66 ± 3.35 | 88.51 ± 1.33 | 91.69 ± 1.42 | 92.49 ± 1.08 | 96.56 ± 1.11 |

| 8 | 82.09 ± 4.25 | 90.43 ± 1.57 | 88.67 ± 3.02 | 89.93 ± 1.02 | 91.93 ± 4.50 | 89.74 ± 1.69 | 90.38 ± 2.80 | 89.73 ± 3.97 | 86.00 ± 2.01 | 96.16 ± 1.05 |

| 9 | 87.47 ± 2.96 | 89.12 ± 1.09 | 88.63 ± 3.58 | 88.86 ± 3.46 | 92.76 ± 3.26 | 90.71 ± 1.60 | 87.00 ± 2.04 | 89.34 ± 3.46 | 90.65 ± 2.70 | 96.51 ± 1.16 |

| 10 | 96.74 ± 2.68 | 87.64 ± 2.54 | 97.01 ± 1.77 | 98.12 ± 1.05 | 99.25 ± 1.42 | 98.64 ± 0.57 | 97.7 ± 0.55 | 98.49 ± 0.81 | 98.29 ± 0.49 | 99.15 ± 0.55 |

| 11 | 94.36 ± 2.99 | 97.09 ± 0.55 | 96.03 ± 1.50 | 96.17 ± 1.98 | 97.73 ± 1.90 | 95.35 ± 1.52 | 95.79 ± 2.56 | 98.07 ± 0.88 | 95.36 ± 3.07 | 98.92 ± 0.26 |

| 12 | 71.34 ± 19.12 | 94.31 ± 2.54 | 76.79 ± 8.41 | 82.59 ± 8.90 | 86.42 ± 6.44 | 89.98 ± 3.74 | 80.29 ± 5.77 | 88.96 ± 3.02 | 80.02 ± 4.91 | 93.19 ± 2.46 |

| 13 | 79.78 ± 10.53 | 88.41 ± 2.30 | 75.75 ± 6.65 | 77.44 ± 5.76 | 80.86 ± 6.76 | 78.47 ± 3.59 | 77.84 ± 0.79 | 83.72 ± 2.10 | 79.95 ± 2.38 | 89.74 ± 2.40 |

| 14 | 89.42 ± 4.53 | 97.59 ± 0.30 | 90.96 ± 1.50 | 90.80 ± 3.01 | 96.40 ± 2.98 | 94.28 ± 0.84 | 91.39 ± 0.76 | 96.74 ± 0.98 | 93.06 ± 1.23 | 96.65 ± 0.77 |

| 15 | 81.91 ± 7.29 | 96.07 ± 1.40 | 72.60 ± 10.81 | 84.06 ± 9.00 | 71.66 ± 22.84 | 68.12 ± 5.94 | 82.48 ± 4.21 | 84.06 ± 3.02 | 80.94 ± 3.10 | 95.54 ± 1.01 |

| 16 | 99.49 ± 0.53 | 99.59 ± 0.12 | 99.49 ± 0.15 | 99.53 ± 0.10 | 99.63 ± 0.08 | 99.72 ± 0.13 | 99.37 ± 0.22 | 99.48 ± 0.03 | 99.52 ± 0.04 | 99.88 ± 0.06 |

| OA(%) | 93.00 ± 0.64 | 97.78 ± 0.10 | 94.04 ± 0.24 | 94.78 ± 0.15 | 96.53 ± 0.64 | 95.37 ± 0.12 | 94.15 ± 0.17 | 95.39 ± 0.16 | 94.47 ± 0.19 | 97.92 ± 0.27 |

| AA(%) | 86.14 ± 2.20 | 95.66 ± 0.47 | 87.85 ± 0.83 | 89.52 ± 0.75 | 91.50 ± 0.71 | 90.29 ± 0.55 | 88.42 ± 0.86 | 91.67 ± 0.66 | 88.71 ± 0.65 | 95.98 ± 0.49 |

| Kappa | 91.80 ± 0.75 | 97.40 ± 0.12 | 93.02 ± 0.28 | 93.89 ± 0.18 | 95.76 ± 0.75 | 94.58 ± 0.14 | 93.15 ± 0.21 | 94.60 ± 0.41 | 93.52 ± 0.94 | 97.56 ± 0.32 |

Table 7.

The classification performance of different methods for the WHU-Hi-LongKou dataset.

Table 7.

The classification performance of different methods for the WHU-Hi-LongKou dataset.

| No. | GSCNet [14] | Hyper-Sigma [12] | Lite-HCNnet [11] | MSDAN [9] | Simpool-Former [30] | Spetral-Former [13] | SSFTT [31] | Mamba-HSI [20] | HG-Mamba [21] | Ours |

|---|

| 1 | 99.86 ± 0.08 | 99.84 ± 0.04 | 99.97 ± 0.02 | 98.64 ± 0.57 | 99.66 ± 0.26 | 99.67 ± 0.13 | 99.76 ± 0.09 | 99.74 ± 0.10 | 99.42 ± 0.08 | 99.90 ± 0.11 |

| 2 | 99.08 ± 0.83 | 93.83 ± 4.44 | 96.68 ± 0.77 | 95.46 ± 1.87 | 83.04 ± 5.52 | 91.31 ± 4.96 | 97.90 ± 1.11 | 93.29 ± 1.43 | 91.67 ± 2.37 | 99.63 ± 0.12 |

| 3 | 95.86 ± 2.35 | 84.55 ± 7.00 | 95.66 ± 1.52 | 93.33 ± 5.06 | 91.51 ± 4.97 | 92.58 ± 1.87 | 94.38 ± 2.87 | 91.34 ± 2.09 | 87.27 ± 2.41 | 99.19 ± 0.68 |

| 4 | 99.39 ± 0.21 | 99.27 ± 0.36 | 99.40 ± 0.18 | 99.23 ± 0.24 | 97.84 ± 0.64 | 98.68 ± 0.32 | 99.20 ± 0.18 | 98.26 ± 0.21 | 98.67 ± 0.14 | 99.63 ± 0.12 |

| 5 | 88.90 ± 5.28 | 66.47 ± 4.76 | 81.28 ± 7.96 | 63.55 ± 8.08 | 72.61 ± 9.66 | 62.06 ± 8.81 | 70.08 ± 4.86 | 68.96 ± 4.07 | 69.37 ± 4.89 | 96.85 ± 0.85 |

| 6 | 99.57 ± 0.39 | 99.50 ± 0.38 | 99.33 ± 0.51 | 97.06 ± 2.28 | 98.77 ± 0.86 | 98.03 ± 1.10 | 99.71 ± 0.19 | 99.40 ± 0.04 | 99.06 ± 0.18 | 99.86 ± 0.11 |

| 7 | 99.75 ± 0.15 | 99.92 ± 0.05 | 99.74 ± 0.21 | 99.49 ± 0.42 | 99.74 ± 0.18 | 99.92 ± 0.03 | 99.60 ± 0.21 | 99.87 ± 0.06 | 99.67 ± 0.10 | 99.92 ± 0.03 |

| 8 | 87.19 ± 1.93 | 84.98 ± 7.18 | 91.06 ± 2.46 | 83.55 ± 7.01 | 78.64 ± 3.05 | 88.49 ± 2.68 | 91.85 ± 2.31 | 78.17 ± 1.36 | 80.06 ± 2.15 | 97.08 ± 0.70 |

| 9 | 90.34 ± 2.75 | 87.33 ± 1.61 | 86.60 ± 5.97 | 85.8 ± 3.70 | 77.68 ± 9.01 | 74.46 ± 1.31 | 90.14 ± 1.63 | 85.09 ± 2.38 | 83.17 ± 1.77 | 96.14 ± 0.79 |

| OA(%) | 98.66 ± 0.07 | 97.69 ± 0.30 | 98.45 ± 0.18 | 97.24 ± 0.22 | 96.43 ± 0.37 | 97.02 ± 0.24 | 98.25 ± 0.12 | 97.17 ± 0.09 | 97.05 ± 0.17 | 99.54 ± 0.03 |

| AA(%) | 95.55 ± 0.74 | 90.63 ± 1.67 | 94.41 ± 0.93 | 90.68 ± 0.45 | 88.83 ± 1.09 | 89.22 ± 0.76 | 93.62 ± 0.55 | 90.46 ± 1.01 | 89.82 ± 0.87 | 98.69 ± 0.23 |

| Kappa | 98.24 ± 0.09 | 96.95 ± 0.40 | 97.96 ± 0.23 | 96.36 ± 0.29 | 95.30 ± 0.48 | 96.07 ± 0.32 | 97.70 ± 0.15 | 96.27 ± 0.22 | 96.11 ± 0.28 | 99.40 ± 0.04 |

Table 8.

Complexity and efficiency comparison of different methods for five datasets.

Table 8.

Complexity and efficiency comparison of different methods for five datasets.

| Methods | GSCNet [14] | Hyper-SIGMA [12] | MSDAN [9] | Spectral-Former [13] | SSFTT [31] | MambaHSI [20] | HGMamba [21] | Ours |

|---|

| PaviaU | Params (M) | 0.63 | 182.76 | 3.26 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.42 |

| FPS (sample/s) | 5647.49 | 240.46 | 517.49 | 1332.14 | 692.36 | 775.89 | 569.49 | 1125.27 |

| Training time (s) | 0.12 | 1.78 | 0.83 | 0.32 | 0.62 | 0.55 | 0.75 | 0.38 |

| Houston | Params (M) | 1.16 | 182.81 | 3.34 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.42 |

| FPS (sample/s) | 1307.44 | 256.32 | 530.21 | 1811.49 | 1308.43 | 1196.3 | 896.07 | 1645.43 |

| Indian Pines | Training time (s) | 0.79 | 2.93 | 1.42 | 0.41 | 0.57 | 0.63 | 0.84 | 0.46 |

| Params (M) | 2.33 | 182.89 | 3.34 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.42 |

| FPS (sample/s) | 957.87 | 226.41 | 139.38 | 1947.28 | 1596.33 | 1080.45 | 820.63 | 1306.04 |

| Training time (s) | 1.04 | 4.52 | 7.35 | 0.53 | 0.64 | 0.95 | 1.25 | 0.78 |

| WHU-Hi-HanChuan | Params (M) | 0.13 | 182.77 | 3.34 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.43 |

| FPS (sample/s) | 207.99 | 176.1 | 287.58 | 1093.11 | 619.49 | 560.53 | 429.07 | 1163.31 |

| Training time (s) | 1.24 | 1.16 | 0.89 | 0.24 | 0.41 | 0.46 | 0.6 | 0.21 |

| WHU-Hi-LongKou | Params (M) | 0.13 | 182.8 | 3.34 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.43 |

| FPS (sample/s) | 374.33 | 190.7 | 369.66 | 767.57 | 527.05 | 479.59 | 368.13 | 862.37 |

| Training time (s) | 0.54 | 1.35 | 0.55 | 0.27 | 0.49 | 0.43 | 0.55 | 0.37 |