Abstract

Most deep-learning-based vision tasks rely heavily on crowd-labeled data, and a deep neural network (DNN) is usually impacted by the laborious and time-consuming labeling paradigm. Recently, foundation models (FMs) have been presented to learn richer features from multi-modal data. Moreover, a single foundation model enables zero-shot predictions on various vision tasks. The above advantages make foundation models better suited for remote sensing images, where image annotations are more sparse. However, the inherent differences between natural images and remote sensing images hinder the applications of the foundation model. In this context, this paper provides a comprehensive review of common foundation models and domain-specific foundation models for remote sensing, and it summarizes the latest advances in vision foundation models, textually prompted foundation models, visually prompted foundation models, and heterogeneous foundation models. Despite the great potential of foundation models for vision tasks, open challenges concerning data, model, and task impact the performance of remote sensing images and make foundation models far from practical applications. To address open challenges and reduce the performance gap between natural images and remote sensing images, this paper discusses open challenges and suggests potential directions for future advancements.

1. Introduction

We are currently in the era of remote sensing, big data, and artificial intelligence. With the continuous progress of imaging techniques and artificial intelligence advances, high-resolution remote sensing images have been widely used for various applications, such as resource exploration, environmental monitoring, precision agriculture, military reconnaissance, and so on [1,2]. Compared to traditional machine learning algorithms, DNNs have revolutionized the accuracy of remote sensing vision tasks with rich annotation data and powerful GPU computing power. However, DNNs are far from the remote sensing requirements. On one hand, DNNs are usually impacted by the laborious and time-consuming labeling requirement and single-task DNN limitation (e.g., a DNN is generally trained for each visual recognition task). On the other hand, remote sensing image annotations are more sparse.

Recently, foundation models (FMs) have been a hot and interesting topic in many fields, and they have demonstrated strong versatility in visual and language understanding tasks, e.g., ChatGPT [3], Gemini [4], and visual ChatGPT [5]. FMs have shown promising signs in remote sensing; however, the essential differences between remote sensing images and natural images make the direct application of FMs limited for remote sensing images [6]. Therefore, it is necessary to develop domain-specific FMs peculiar to remote sensing by carefully considering the common technique shared between different domains and the inherent characteristics of remote sensing images. In this context, this paper aims to comprehensively review common foundation models and domain-specific foundation models for remote sensing. Compared to related surveys [7,8,9], this paper covers the newest FMs and emerging advances (e.g., prompt-related FMs, Mamba vision FMs), which are very important for developing remote-sensing-specific FMs.

The paper is organized as follows. First, the basic principles of foundation models and common techniques are reviewed, and the specific methods of foundation models in remote sensing are then surveyed. The challenges are summarized and the follow-up research directions are explored.

2. Foundation Model for General Vision Tasks

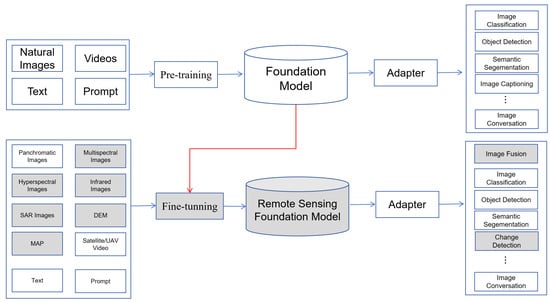

The flowchart of FMs for general vision tasks and remote sensing images is shown in Figure 1. A foundation model is essentially a backbone for feature learning, and fine-tuning or an adapter is usually used for different domains or downstream tasks. The following three characteristics make FMs very promising for vision tasks:

Figure 1.

Flowchart of FMs for vision tasks on natural images and remote sensing images.

- (1)

- Model size. The massive model size enables FMS to capture more complex patterns hidden in the data, generating more representative features.

- (2)

- Learning strategy. By taking advantage of related data (including text, images, audio, and video), FMs use self-supervised or semi-supervised learning without human supervision or with minimal human interaction, which alleviates the time-consuming and labor-consuming labeling work.

- (3)

- Adaptation. FMs are trained on broad data and could be easily adapted to various downstream tasks [10].

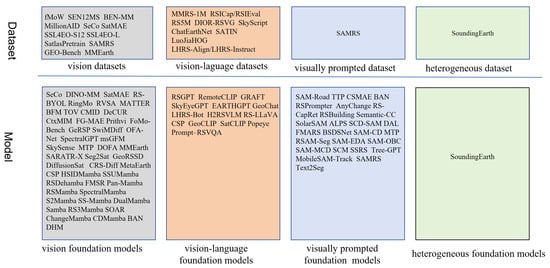

Besides traditional vision foundation models and vision–language foundation models, several research efforts are devoted to developing visually prompted foundation models, e.g., Segment Anything Model (SAM) [11]. To provide a systematic review of recent foundation models, this paper focuses on the following foundation models: vision FMs, textually prompted FMs (i.e., vision–language FMs), visually prompted FMs, and heterogeneous FMs. Figure 2 lists state-of-the-art foundation models of different types. Below, we review the above foundation models from the perspective of pre-training and fine-tuning.

Figure 2.

State-of-the-art foundation models. Milestone models are marked in red.

2.1. Foundation Model Pre-Training

2.1.1. Vision Foundation Model

Vision foundation models aim to encode visual features, and they can be categorized into ViT-based, CNN-based, and Mamba-based types. By taking advantage of the attention mechanism, ViT defines a new paradigm for vision tasks. To enhance ViT, many variants (e.g., Swin Transformer [12], PyramidViT [13], LeViT [14], LocalViT [15], and MIM [16]) are proposed. It is worth noting that InternImage [17] is a large-scale CNN-based foundation model, which learns stronger and more robust patterns like ViT by reducing the inductive bias of CNNs. Vision Mamba models such as ViM [18] and VMamba [19] mitigate the modeling constraints of CNNs and offer Transformer-like modeling strengths by global receptive fields and dynamic weighting. Mamba-type foundation models perform excellently on long-sequence modeling tasks. Compared with other foundation models, vision foundation models are limited due to the uncertainty of images and the lack of powerful semantic representation taken by the language model.

2.1.2. Vision–Language Foundation Model

A vision–language foundation model is the combination of a vision model and a natural language model. The vision model captures visual features from the images, while the language model encodes information from the text. For instance, the newest GPT-4V [20] integrates image inputs into large language models (LLMs), transforming FMs from language-only systems to multi-modal powerhouses. Vision–language foundation models aimed at jointly understanding visual and textual modalities. To better connect vision models and language models, vision–language models are usually pre-trained by the following three objectives [21]: contrastive objective, generative objective, and alignment objective.

- (1)

- Contrastive objectiveThe rationale of the contrastive objective is to learn discriminative image–text representations by pulling the embeddings of paired images and texts close while pushing others away. The milestone of the contrastive objective is CLIP [22]. CLIP jointly trained an image encoder and text encoder, and the contrastive loss aimed to maximize the cosine similarity between the paired image and text embeddings. To address the limitation of CLIP in computationally expensive pre-processing and cleaning, ALIGN [23] trained a dual encoder-based model on one billion noisy image–caption datasets, where cosine similarity was optimized via normalized softmax loss. To handle representations from space–time–modality space, Florence [24] expanded the images and textual representations from coarse to fine, from static to dynamic, and from RGB to multiple modalities. Finer-level information between modalities is hard to represent by CLIP-like methods, and FILIP [25] aimed to capture fine-grained semantic alignment by the token-wise cross-modal interaction. Motivated by the masked auto-encoder, FLIP [26] enhances CLIP by masking 50–75% of input pixels, and the computation complexities are reduced by 2–4 times. In contrast, MaskCLIP [27] learns local semantic features by the random masking of the input image and teacher-based self-distillation; EVA-CLIP [28] masks visual inputs to address the instability and optimization efficiency.

- (2)

- Generative objectiveThe generative objective aims to learn semantic features and generate images or texts via masked modeling techniques. Masked image modeling is used to mask certain patches in an image, and the encoder is trained to learn image context information and reconstruct images conditioned on unmasked patches. For instance, a large portion of patches (i.e., 75%) were masked out in training KELIP [29] and SegCLIP [30]. Masked language modeling masks a fraction of tokens in each input text and predicts the masked tokens. In contrast, masked cross-modal modeling works by jointly masking and reconstructing text tokens and image patches. For instance, for FLAVA [31], the masked portions of image patches and text tokens are 40% and 15%, respectively. For an image, image-to-text generation aims to generate descriptive texts and capture fine-grained vision–language correlation. For example, COCA [32] produces intermediate embeddings by encoding an input image, and embeddings are then decoded into descriptive texts.

- (3)

- Alignment objectiveThe alignment objective aligns the image–text pair in an embedding space via global matching between image and text or local matching between region and word. For instance, GLIP [33] and DetCLIP [34] model local fine-grained vision–language correlation by replacing object classification logits with region–word alignment scores.

2.1.3. Visually Prompted Foundation Model

A visually prompted foundation model can be prompted by various prompts, e.g., text, points, and bounding boxes. SAM [11] is a milestone of visually prompted models, and it is trained on 11 million images and 1.1 billion masks. The rationale of SAM involves encoding image and prompt embeddings, respectively, and predicting segmentation masks using a lightweight mask decoder. Two best-known training-free approaches based on SAM are Per-SAM [35] and its variant, PerSAM-F. For an image and a reference mask, PerSAM localizes the target concept before estimating the object’s position, while PerSAM-F reduces mask ambiguity by one-shot fine-tuning. SEED [36] takes more prompt types and exhibits strong generalization capabilities.

It is worth noting that the combination of SAM and vision–language foundation models is more powerful. For instance, Grounded-Segment-Anything [37] aims to detect and segment anything with text inputs, where bounding boxes are obtained by Grounded-DINO [38] and text prompts, and target segmentations are achieved by SAM and bounding boxes. Caption-AnyThing [39] leverages SAM and large language models for zero-shot image captioning.

Other visually prompted models for image segmentation include CLIPSeg [40], SegGPT [41], and SEEM [42]. CLIPSeg achieved capabilities for zero-shot and one-shot segmentation, and the Transformer-based decoder is conditioned on text–visual CLIP embeddings. SegGPT aims to train a foundation model applicable to diverse segmentation tasks in an in-context learning paradigm.

2.2. Foundation Model Fine-Tuning

Fine-tuning is essential for foundation models adapting to specific domains or downstream tasks. Full fine-tuning needs training the entire model on a remote sensing dataset, allowing for complete adaptation to the specific domain. However, it requires significant computational resources and can lead to overfitting. In contrast, parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) updates only a small subset of parameters, such as the last few layers or specific attention heads [43]. PEFT methods like adapter, prompt tuning, and low-rank adaptation are commonly used to reduce computational costs and improve efficiency. An adapter is a small neural network inserted into the pre-trained model, facilitating task-specific adaptation without modifying the original model’s parameters. CLIP-Adapter [44] learns new features by adding a bottleneck layer and performs residual-style feature blending with the pre-trained features. SAM-Adapter [45] adapts SAM to downstream tasks by injecting customized information into the network. MaskCLIP [27] adapts CLIP and masked self-distillation to learn local and global semantics. To further improve the segmentation performance, MaskCLIP+ [46] combines pseudo-labeling and self-training. Prompt tuning involves injecting task-specific information into the model’s input and aims to guide the model to focus on relevant features. Low-rank adaptation reduces the parameter size by factorizing the model’s weight matrices into low-rank matrices. In contrast, prompt-tuning methods involve finding the optimal prompts without fine-tuning the entire VLM. For example, CoOp [47] keeps the pre-trained models fixed and utilizes learnable vectors to model a prompt’s context words. Visual prompt tuning enables pixel-level adaptation to downstream tasks. For example, DenseCLIP [48] adapts CLIP for dense prediction by converting the image–text matching problem in CLIP to a pixel–text matching problem.

By taking advantage of pre-trained models and the above fine-tuning techniques, FMs define many new tasks. For instance, CLIP defines concepts such as visual grounding, open-vocabulary object detection, referring image segmentation, and phrase grounding. Specifically, RegionCLIP [49] established a new SOTA for zero-shot and open-vocabulary object detection. CLIP-Driven CRIS [50] extended CLIP for the referring image segmentation task by introducing a visual–language decoder and a text-to-pixel contrastive loss. GLIP [33] reformulated the object detection task to phrase grounding, where all class names are combined in one sentence. Grounding–DINO [38] is an open-set object detector that combines the strengths of DINO with grounded pre-training, and it can detect arbitrary objects using human-provided text descriptions.

To tailor pre-trained foundation models to remote sensing tasks, fine-tuning and adapter techniques are usually employed. Specifically, fine-tuning aims to extend pre-trained backbones on natural images for the remote sensing domain by refining model parameters based on remote sensing images, and adapters are usually used for downstream tasks by adding additional layers to the refined backbone. For instance, SPT [51] is a novel fine-tuning technique for SAR images, which uses scattering information as a prompt and integrates learnable parameters into the pre-trained model. MANet [52] adapts SAM for semantic segmentation and fuses information from different modalities to enhance the segmentation performance. Training-Efficient Adapting (TEA) [53] combines parameter-efficient fine-tuning with a top-down guidance mechanism to improve the efficiency and performance of foundation models in remote sensing. PETL [54] explores parameter-efficient techniques for adapting vision–language pre-trained models to remote sensing image–text retrieval tasks.

3. Remote Sensing Foundation Models

To systematically review recent advances in remote sensing foundation models, Figure 3 elaborated important efforts on datasets and foundation models.

Figure 3.

Overview of remote sensing datasets and foundation models.

3.1. Dataset

Some large-scale datasets are constructed for foundation model pre-training. Vision datasets are mainly for traditional tasks such as scene classification, semantic segmentation, and object detection. For instance, fMoW [55] contains 1 million images from 200 countries, and it aims to predict the functional purpose of buildings and land use. SEN12MS [56] consists of 180,662 triplets of dual-polarization SAR image patches, multi-spectral Sentinel-2 image patches and MODIS land cover maps. MillionAID [57] contains a million instances for scene classification. SatlasPretrain [58] consists of 302 M labels under 137 categories and seven label types: points, polygons, polylines, properties, segmentation labels, regression labels, and classification labels. Vision–language datasets have richer semantic information, and they are mainly constructed for downstream tasks such as image captioning and VQA. Table 1 lists some representative vision–language datasets. MMRS-1M [59] is the largest multi-modal multi-sensor instruction-following dataset, consisting of over 1M image–text pairs about optical, SAR, and infrared images. RSICap [60] contains rich and high-quality scene information (e.g., residential area, airport, or farmland) and object information (e.g., color, shape, quantity, absolute position, etc). These datasets help us pre-train or fine-tune a vision–language foundation model; however, differences between various datasets concerning captions and object information may hinder us from training a unified vision–language foundation model. Other types of datasets are rare. SAMRS [61] is a large-scale segmentation dataset that leverages SAM and existing object detection datasets. SoundingEarth [62] consists of about 50k pairs of overhead images and crowd-sourced audio samples, and it aims to train ResNet models and understand the key properties of a scene by mapping visual and auditory modalities into a common embedding space.

Table 1.

Vision–language datasets.

3.2. Foundation Models

By effectively employing fine-tuning and adapter techniques [71], researchers can leverage the power of foundation models to tackle a wide range of remote sensing challenges, from object detection and segmentation to scene classification and change detection. Below, we review typical foundation models for remote sensing in depth.

3.2.1. Vision Foundation Models

Due to the complexity of remote sensing images, the foremost important extension of vision foundation models is to learn domain-specific representation and add domain-specific knowledge. For instance, DINO-MM [72] aimed to learn joint representation and the invariant representation of optical images and SAR images. Seg2Sat [73], map-sat [74], DiffusionSat [75], CRS-Diff [76], and MetaEarth [77] aimed at generating realistic or higher-resolution images by diffusion-based generative foundation models. CROMA [78] learns rich unimodal and multi-modal representations by combining contrastive and reconstruction objectives. MATTER [79] leverages multi-temporal satellite images to learn features that are robust to changes in illumination and viewing angle. Considering the differences between natural images and remote sensing images, GeoKR [80] and GASSL [81] enhance the foundation model through geographical knowledge and geography awareness. SAR-JEPA [82] learns multi-scale SAR target representations by knowledge-guided predictive architecture. RSBuilding [83] unifies building extraction and building change detection tasks by a task-prompted cross-attention decoder. CSPT [84] gradually bridged the domain gap and transferred large-scale data knowledge to the remote sensing domain. GFM [85] investigated the potential of continual pre-training from the large-scale ImageNet-22k model to the geospatial foundation model. To handle objects of arbitrary orientations in remote sensing images, RVSA [86] utilized a new rotated varied-size window attention to learn better object representation and handle objects of arbitrary orientations. EarthPT [87] accurately predicts pixel-level surface reflectance across the 400–2300 nm range. Prithvi [88] is a Transformer-based foundation model, and it could be fine-tuned for various tasks such as multi-temporal crop segmentation and flood mapping. To reduce the model size, SiamIntCD [89] adapts a CNN-based vision foundation model, InternImage [17], for change detection. It is the first CNN-based change detection vision foundation model and combines the advantages of Siamese architecture and InternImage.

By taking advantage of state-space models (SSMs) with selection mechanisms and hardware-aware architectures, Mamba is powerful in long-sequence modeling. Due to the quadratic complexity of the self-attention mechanism, the Mamba foundation model has recently been adapted for computer vision. tasks, i.e., Vision Mamba (ViM). ViM’s efficiency in processing large-size images makes it well-suited for high-resolution remote sensing data, and the bidirectional SSM captures detailed spatial information, enabling accurate feature extraction from complex remote sensing scenes. Mamba vision foundation models have been widely used for various tasks, e.g., denoising(HSIDMamba [90], SSUMamba [91]), dehazing (RSDehamba [92]), super-resolution (FMSR [93]), pan-sharpening (e.g., Pan-Mamba [94]), image classification (RSMamba [95], SpectralMamba [96], Mamba [97], SS-Mamba [98], DualMamba [99]), semantic segmentation (Samba [100], RS3Mamba [101]), object detection (SOAR [102]), change detection (ChangeMamba [103], CDMamba [104], BAN [105]), and compressive imaging (DHM [106]). HSIDMamba [90] outperforms the latest Transformer architectures by 30% efficiency by incorporating bi-directional continuous scanning, which strengthens spatial–spectral interactions from eight directions. RSDehamba [92] is an extremely lightweight Mamba-based model with only 1.80 M and outperforms baseline methods by more than 0.72 dB. Pan-Mamba [94] utilizes channel-swapping Mamba to initiate cross-modal interaction between partial panchromatic and multi-spectral channels and cross-modal Mamba to exploit cross-modal relationships for improving the information representation capability. Mamba [97] utilizes bi-directional spectral scanning to explore semantic information from continuous spectral bands and the spatial–spectral mixture gate to adaptively incorporate representations from different dimensions. Samba [100] is the first Mamba method for the semantic segmentation of remote sensing images, where Samba blocks serve as the encoder and UperNet as the decoder. ChangeMamba [103] is the first Mamba method for change detection tasks and it adopts ViM as the encoder to learn global spatial contextual information. From the above analysis, it could be inferred that the common innovations of the above methods are learning the representative spatial, temporal, and spectral context and reducing computation complexity. While ViM foundation models have shown promising performances in remote sensing images, the inherent 1D nature of selective scanning technique presents challenges for 2D or higher-dimensional visual data, and critical spatial information may be lost. This problem requires further investigation in the future.

Details of state-of-the-arts vision foundation models can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Vision foundation models.

3.2.2. Textually Prompted Foundation Models

Compared to pure vision-based models, textually prompted foundation models define new vision tasks. Specifically, traditional label-featured image classification, object detection and semantic segmentation tasks are transformed to open-vocabulary image classification, open-vocabulary object detection, and open-vocabulary semantic segmentation, e.g., GRAFT [124] and YOLO-World [125].

The other advantage taken by textually prompted foundation models is the utilization of language model for image captioning and VQA, e.g., RSGPT [60] and RS-LLaVA [126]. RSGPT [60] created vision–language chat agents for remote sensing images. Interestingly, the addition of a language model makes the vision–language foundation model easily adapted for image captioning and visual grounding (e.g., SkyEyeGPT [127], EARTHGPT [59]) and image–text retrieval and object counting(RemoteCLIP [128]), where visual grounding aims to locate relevant objects or regions based on a natural language query. Moreover, GeoChat [129] offers multitask conversational capabilities, i.e., image-level queries, region-specific dialogue, visually grounded objects, etc. Table 3 lists details of state-of-the-arts vision–language foundation models.

Table 3.

Remote sensing vision–language foundation models.

3.2.3. Visually Prompted Foundation Models

Recently, the remote sensing community has shown strong interest in adapting SAM for segmentation-related applications, especially the combination of SAM and CLIP [133,134]. The fact that SAM provides accurate region segmentation and CLIP provides reliable semantics makes foundation models attractive for practical applications. Figure 4 shows two strategies of combining SAM and CLIP, i.e., pre-SAM and post-SAM. Specifically, for the pre-SAM strategy, a text prompt is used as input for Grounding DINO or CLIP Surgery, which generates bounding boxes or point prompts for SAM to produce a semantic segmentation map. In contrast, post-SAM employs SAM to generate all available segmentation masks and then utilizes CLIP to identify masks of interest by comparing semantic similarities with the text prompt. Awesome applications vary from different data (optical images [135,136], multi-view remote sensing image [137], SAR images [138], aerial images [139], point cloud [140], LiDAR data [141]), different tasks (semantic segmentation [83,142], instance segmentation [143], shadow detection [144], change detection [145], image understanding [146]), domain adaptation [147], and zero-shot and one-shot learning [134].

Figure 4.

Two strategies of combining SAM and CLIP. The figure is from [148].

SAM relies on manual guidance due to its interactive nature, and it is limited for automated remote sensing image segmentation. RSPrompter [143] learns to produce task-specific prompts, which help SAM generate semantically discernible segmentation results. AnyChange [149] is a zero-shot change detection approach, which adopts SAM to reveal intra-image and inter-image semantic similarities in the latent space. With zero-shot change detection capability. SAM-Road [142] adapts SAM for efficiently and accurately predicting road segments and intersections from satellite images. RingMo-SAM [136] can segment anything and identify object categories in optical and SAR images, and it improves the multi-object segmentation performances of complicated scenes by multi-box prompts. SAMCD [150] adapts FastSAM for change detection, where FastSAM focuses on some specific ground objects and models the semantic latent in bitemporal images. Some typical applications are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Visually prompted foundation models for remote sensing.

Despite the novelties of SAM, the following limitations hinder the application and need to be addressed in the future [157]: the requirement of strong prior knowledge, less effectiveness in low-contrast applications, a limited understanding of the professional data, and smaller and irregular object segmentation. Ren [158] found that SAM is sensitive to image resolution, and it produces poor performances on some object classes such as roads.

3.2.4. Other Foundation Models

Heterogeneous foundation models for remote sensing are rare. SoundingEarth [62] exploits the correspondence between co-located images and audio recordings, and it understands a scene by visual and auditory properties.

It is worth noting that the model size is an important factor in balancing the model performance and computation efficiency. On the one hand, a larger model will help the foundation model learn complex and representative features. On the other hand, a larger model will need more computational resources for training and inference. Generally, the size of foundation models for remote sensing images varies significantly depending on the architecture, training data, and specific tasks. Specifically, small-scale models contain around 20–30 million parameters (e.g., ResNet50-based models), medium-scale models about 80–100 million parameters (e.g., ViT-Base), and large-scale models over 1 billion parameters (e.g., ViT-Huge, Swin-Large). For instance, Prithvi [88] is based on ViT-Base architecture and contains around 100 million parameters; EarthPT [87] is based on ViT-Huge architecture and contains approximately 700 million parameters; RingMo 3.0 [159] is one of the largest remote sensing foundation models, and it contains over 10 billion parameters.

4. Discussion

4.1. Open Challenges

Theoretically, foundation models for natural images could be directly applied to remote sensing images due to their powerful capability of zero-shot or few-shot learning. However, due to the significant differences between natural images and remote sensing images [6], foundation models for remote sensing images face several open challenges, and there exists a considerable performance gap between remote sensing images and natural images. Specifically, open challenges lie in the following three aspects:

- (1)

- Data challenges

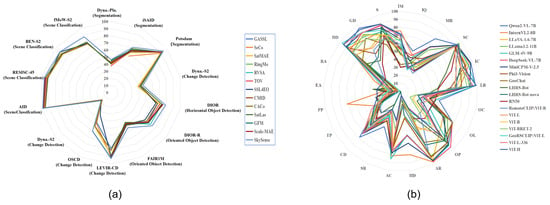

Data heterogeneity: Due to differences in imaging factors (e.g., imaging platform, imaging mechanism, and imaging condition), remote sensing data has high variations concerning modality (i.e., optical images, infrared images, hyperspectral images, and SAR images), spatial resolution, viewpoint, and so on. The variations hinder the direct application of foundation models to remote sensing images. For instance, as illustrated by Figure 5a, kySense performs differently on LEVIR-CD and OS-CD, i.e., 92.58% vs. 60.06%. The performances are significantly different on homogeneous optical images, let alone heterogeneous images between optical images and SAR images or hyperspectral images.

Figure 5.

A performance comparison of state-of-the-art foundation models on various datasets and tasks. (a): Vision foundation models performance comparison; Data from [114]. (b): Vision–language foundation models performance comparison; Data from [160]. Image-level comprehension contains five leaf tasks: scene classiffcation (SC), map recognition (MR), image caption (IC), image quality (IQ), and image modality (IM). Single-instance Identiffcation comprises seven tasks: landmark recognition (LR), object presence (OP), object localization (OL), object counting (OC), attribute recognition (AR), visual grounding (VG) and hallucination detection (HD). Cross-instance discernment (CID) consists of three leaf tasks: attribute comparison (AC), spatial relationship (SR) and change detection (CD). Attribute reasoning (AttR) includes two key aspects: time property (TP) and physical property (PP). Assessment reasoning (AssR) contains resource assessment (RA) and environmental assessment (EA). Common sense reasoning (CSR) consists of three leaf tasks: disaster discrimination (DD), geospatial determination (GD) and situation inference (SI).

Annotation data scarcity: Multiple data modalities (e.g., images, text, and geographic information) are required to train foundation models. For instance, the availability of large-scale image–text pairs is crucial for developing a vision–language foundation model. However, datasets published in the remote sensing domain are less than natural images and far from practical applications, and obtaining sufficient amounts of high-quality multi-modal data is challenging due to the complex differences between multi-modal data and reliable alignment in terms of spatial–temporal dimension and semantical dimension.

Dataset evaluation complexity: To train powerful foundation models, high-quantity and high-quality requirements are simultaneously important for constructing datasets. However, it is challenging to evaluate and compare the qualities of different datasets, and captions about deep understanding and spatial reasoning are more difficult to assess. Dataset quality is impacted by complex factors, e.g., image quality, imaging condition, task definition, annotation tool, and annotation experience. The lack of dataset quality evaluation makes reliable model benchmarks difficult.

- (2)

- Model challenges

Model architecture: Due to the significant difference between natural images and remote sensing images, naive model architectures for natural images are limited for remote sensing images. In detail, the desired model architecture for remote sensing requires considering the imaging mechanism, data heterogeneity, physical constraints, and domain-specific knowledge. Despite the great efforts in developing domain-specific model architecture, existing foundation models are far from the above expectations, which could be illustrated by the significant performance gap between natural images and remote sensing images.

Model performance: Foundation models achieved remarkable zero-shot prediction performances on natural images and image-level comprehension tasks. However, the performances on remote sensing images and semantic reasoning tasks are far from practical applications. As illustrated by Figure 5b, foundation models face challenges in addressing the attribute and assessment reasoning task. Specifically, all models scored below the random guess level, 50%, and many state-of-the-art models performed below 20%.

Model complexity: Larger model size helps foundation models generate more representative features and capture more complex patterns hidden in the data. However, prohibitive model size requires significant computational resources for training and inference, and it hinders foundation models for emergent applications (e.g., disaster monitoring, emergency search and rescue) and resource-limited tasks (e.g., onboard object detection). In addition, prohibitive model size may be prone to concealing the interpretability of the model.

Model evaluation: Evaluating different foundation models on a fair and uniform benchmark is very important. However, a fair evaluation is difficult. On the one hand, the evaluation is usually impacted by many other factors. For instance, by following the image resizing and normalization trick in pre-training, significant performance improvements (e.g., 32.28% on the So2Sat random split dataset and 11.16% on the EuroSAT dataset) could be achieved on downstream tasks [161]. In this context, reliable cross-domain evaluation is difficult to perform. On the other hand, a particular image can have several ground-truth descriptions, but the common evaluation strategies only compare a candidate sentence with reference sentences. Fair evaluation becomes difficult when consensus is low for reliable predictions.

- (3)

- Application-specific challenges

Task difficulty: In contrast to object detection on natural images where objects are well postured, domain-specific task difficulties disturbed remote sensing, such as large object-size variation (e.g., airplane vs. airport), significant appearance differences caused by view-angle variation, and the sensor-related features (e.g., radiation feature, scattering feature, spectral feature, temperature feature). Foundation models will perform poorly if the above task difficulty is not carefully considered.

Task isolation: In the literature, most foundation models are performed on individual tasks independently, without considering their potential interactions and dependencies. In the remote sensing domain, it may lead to suboptimal performance and limited insights into the model’s capabilities.

Application imbalance: Application imbalance refers to the uneven distribution of training data and evaluation metrics between different remote sensing applications. For instance, foundation models mainly focus on certain image types (e.g., optical images), certain object types (e.g., buildings, roads, airplanes), and other image types (e.g., SAR images, infrared images, hyperspectral images) and certain object types (e.g., fine-grained crop and forest classification [59,146,162,163,164]) are usually ignored. In fact, fine-grained crop and forest classification face inherent challenges of feature learning (e.g., low interclass discrimination and high intraclass difference), and it is worth more in-depth research.

4.2. Future Directions

To address the above challenges, the following directions should be emphasized in the future.

- (1)

- Multi-modal annotation augmentation

To solve data challenges about annotation quantity, annotation quality, modal consistency and application balance, the multi-modal annotation should be augmented. Considering the scarcity of high-quality image–text data and the prohibitive cost of manual captioning, AI-assisted annotations may be interesting. For instance, AIGC helps us generate variant images from the given captions, and Geochat helps generate captions from images. Of course, careful validation and correction are mandatory to improve the training data quality. Considering the semantic consistency between multi-sensor remote sensing images, annotations can be facilitated by utilizing annotations on optical images and image registration techniques. In this context, training data construction is essentially the fast annotation propagation over unchanged regions. In addition, we can take advantage of other auxiliary data to reduce the annotation labor. For example, land cover products, geographical location and OpenStreetMap tags could be used for geographical knowledge to provide supervision or annotation. For reasoning annotation, it is necessary to invite cognitive scientists and psychologists to reduce the semantic bias.

- (2)

- Domain-specific model architecture

Different from nature images, remote sensing images implicitly hide some geographical priors, physical constraints and domain knowledge, and it is difficult for the naive foundation model to capture the latent information. In consequence, it is mandatory to develop foundation models specific to remote sensing domains. In our opinion, physics-constrained foundation models may be a potential solution. A physics-constrained foundation model is essentially a neural network architecture that incorporates physical laws (e.g., atmospheric scattering, radiative transfer, or surface reflectance models) and imaging principles into the backbone, the loss function, and the training process. This integration allows the foundation model to learn more accurate and reliable representations of the real world, where physical processes govern remote sensing data generation. For instance, although end-to-end networks are powerful in learning complex mapping, however, it is not easy for them to learn physics-related features from multispectral images, e.g., the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), the normalized difference water index (NDWI), the normalized difference soil index (NDSI), and non-homogeneous feature difference (NHFD). In other words, adding a remote-sensing-specific imaging model or prior knowledge to the foundation model will help improve the feature discrimination and model interpretation.

- (3)

- Cognition-informed model enhancement

Cognition-informed foundation models for remote sensing involve a multi-faceted approach, combining foundation models with principles of human cognition (e.g., hierarchical learning, attention mechanisms, contextual understanding) and symbolic reasoning (e.g., knowledge graphs, causal inference). One important future task is to enhance the vision encoder, since the poor performance of foundation models mainly stems from visual incapability [165]. i.e., the gap between CLIP-based visual embeddings and vision-only self-supervised learning. In fact, the vision encoder is more challenging when considering the complexities of remote sensing data, and a cognition-driven vision encoder is expected to address the above limitations.

- (4)

- Domain adaptation

Domain adaptation aims to improve the model’s versatility by adapting foundation models to different remote sensing domains, such as multi-sensor, multi-resolution, and multi-temporal images. This involves transferring knowledge from a source domain (e.g., low-resolution satellite images) to a target domain (e.g., high-resolution UAV images). However, the following factors make domain adaptation challenging, the significant domain gap between different modalities, the scarcity of labeled data in many domains, and the expensive computational cost for large-scale datasets. To address these challenges, future research directions include unsupervised domain adaptation (i.e., developing techniques that can adapt models without requiring labeled target domain data), self-supervised learning (leveraging self-supervised learning to learn domain-invariant representations), meta-learning (training models that can quickly adapt to new domains with limited data), hybrid approaches (combining multiple domain adaptation techniques to achieve optimal performance), and continual learning (enabling models to learn continuously from data streams without forgetting previously acquired knowledge).

- (5)

- Multi-task cooperative learning

Multi-task cooperative learning is a machine learning paradigm where multiple tasks are trained simultaneously, sharing information and improving each other’s performance. For foundation models and remote sensing, multi-task cooperative learning can significantly enhance the model’s ability to generalize to different tasks and data distributions. However, it is difficult to identify the appropriate relationships between different tasks, potentially resulting in bias in the model’s learning process caused by data imbalance and expensive computational cost for training large-scale foundation models on multiple tasks. In the future, more efforts should be made to solve the above challenges by shared representation learning (shared encoder and task-specific decoders) and hierarchical multi-task learning (hierarchical task structure or progressive learning).

- (6)

- Adaptive prompt learning

Adaptive prompt learning involves dynamically adjusting prompts to guide the behavior of foundation models. In remote sensing, it is particularly useful for tailoring the model’s output to specific tasks and data characteristics. For instance, adaptive prompt learning can be improved by data-driven adaptation (i.e., adjusting the prompt based on the characteristics of the input data, such as image resolution, spectral bands, and noise levels.), task-driven adaptation (tailoring the prompt to the specific task, such as classification, segmentation, or object detection), and user-driven adaptation (i.e., allowing users to provide feedback to the model, which can be used to refine the prompt).

- (7)

- Model evaluation

Evaluating the performance of foundation models on remote sensing images presents unique challenges due to the complex nature of the data and the diverse range of tasks involved. These challenges can be solved by constructing robust benchmark datasets that cover various remote sensing scenarios and developing advanced evaluation techniques. For instance, human-in-the-loop evaluation is expected to assess the quality and relevance of model predictions by incorporating human judgment.

- (8)

- Model compression and optimization

Several methods have been proposed to reduce the size of foundation models, e.g., model architecture optimization (model pruning, model quantization, knowledge distillation) [166,167], hardware-optimized implementations by GPUs and TPUs [168], model compression techniques (e.g., parameter sharing, low-rank decomposition, sparse neural networks) [169]. However, for some emergent applications such as onboard object detection, storage resources and computation resources are extremely limited, and lightweight foundation models must be studied, e.g., CNN-based foundation models [89], binary foundation models [170].

In short, researchers from different domains should enhance collaborations to solve the above challenges in the AI domain, the remote sensing domain, and the cognitive psychology domain.

5. Conclusions

Foundation models have become a hot topic in the remote sensing field, and they have initially shown promising signs in various remote sensing tasks. However, the essential differences between remote sensing images and natural images make the general foundation model limited for remote sensing images. This paper starts with a review of the common techniques of foundation models, and then a systematic review of remote sensing foundation models is conducted. The limitations of current techniques, as well as future directions, are discussed for future developments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.H. and K.C.; methodology, C.H. and S.Z.; investigation, C.H., Z.W. (Zeyu Wang), Z.W. (Zihan Wang), H.Y., J.S., Y.H. and G.Q.; visualization, J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, C.H., K.C., S.Z., H.F., Z.W. (Zeyu Wang) and Z.W. (Zihan Wang); data curation, J.S. and C.H.; writing—review and editing, C.H. and K.C.; supervision, C.H. and K.C.; funding acquisition, C.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported partially by National Natural Science Foundations of China (Grants No. 62071466).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, L. Artificial intelligence for remote sensing data analysis: A review of challenges and opportunities. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2022, 10, 270–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Sandoval, L.; Crystal-Ornelas, R.; Mousavi, S.M.; Wang, J.; Lin, C.; Cristea, N.C.; Tong, D.Q.; Carande, W.H.; Ma, X.; et al. A review of earth artificial intelligence. Comput. Geosci. 2022, 159, 105034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Li, Q.; Li, C.; Yu, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhang, K.; Ji, C.; Yan, Q.; He, L.; et al. A comprehensive survey on pretrained foundation models: A history from BERT to ChatGPT. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.09419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, G.; Anil, R.; Borgeaud, S.; Alayrac, J.B.; Yu, J.; Soricut, R.; Schalkwyk, J.; Dai, A.M.; Hauth, A.; Millican, K.; et al. Gemini: A family of highly capable multimodal models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.11805. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.; Yin, S.; Qi, W.; Wang, X.; Tang, Z.; Duan, N. Visual ChatGPT: Talking, drawing and editing with visual foundation models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.04671. [Google Scholar]

- Rolf, E.; Klemmer, K.; Robinson, C.; Kerner, H. Mission critical—Satellite data is a distinct modality in machine learning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.01444. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, L.; Huang, Z.; Lu, X.; Liu, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, J.; Hou, B.; Yang, S.; Liu, F.; et al. Brain-inspired remote sensing foundation models and open problems: A comprehensive survey. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2023, 16, 10084–10120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wen, C.; Hu, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Zhu, X.X. Vision-Language models in remote sensing: Current progress and future trends. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.05726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Feng, L.; Ke, Y.; Jiang, X.; Yan, J.; Yang, X.; Zhang, W. Towards Vision-Language Geo-Foundation Model: A Survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.09385. [Google Scholar]

- Bommasani, R.; Hudson, D.A.; Adeli, E.; Altman, R.; Arora, S.; von Arx, S.; Bernstein, M.S.; Bohg, J.; Bosselut, A.; Brunskill, E.; et al. On the opportunities and risks of foundation models. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2108.07258. [Google Scholar]

- Kirillov, A.; Mintun, E.; Ravi, N.; Mao, H.; Roll, C.; Gustafson, L.; Xiao, T.; Whitehead, S.; Berg, A.C.; Lo, W.Y.; et al. Segment anything. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.02643. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin Transformer: Hierarchical vision Transformer using shifted windows. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.14030. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Xie, E.; Li, X.; Fan, D.P.; Song, K.; Liang, D.; Lu, T.; Luo, P.; Shao, L. Pyramid Vision Transformer: A versatile backbone for dense prediction without convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, B.; El-Nouby, A.; Touvron, H.; Stock, P.; Joulin, A.; Jégou, H.; Douze, M. LeViT: A vision Transformer in Convnet’s clothing for faster inference. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, K.; Cao, J.; Timofte, R.; Van Gool, L. LocalViT: Bringing locality to vision Transformers. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.05707. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zeng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, H. Toward building general foundation models for language, vision, and vision-language understanding tasks. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.05065. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Dai, J.; Chen, Z.; Huang, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhu, X.; Hu, X.; Lu, T.; Lu, L.; Li, H.; et al. InternImage: Exploring large-scale vision foundation models with deformable convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.; Liao, B.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Wang, X. Vision Mamba: Efficient visual representation learning with bidirectional state space model. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.09417. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, L. Vision Mamba: A comprehensive survey and taxonomy. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.04404. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://platform.openai.com/docs/guides (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Awais, M.; Naseer, M.; Khan, S.; Anwer, R.M.; Cholakkal, H.; Shah, M.; Yang, M.; Khan, F.S. Foundational models defining a new era in vision: A survey and outlook. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.13721. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual, 18–24 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, C.; Yang, Y.; Xia, Y.; Chen, Y.; Parekh, Z.; Pham, H.; Le, Q.V.; Sung, Y.; Li, Z.; Duerig, T.; et al. Scaling up visual and vision-language representation learning with noisy text supervision. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual, 18–24 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, L.; Chen, D.; Chen, Y.-L.; Codella, N.C.; Dai, X.; Gao, J.; Hu, H.; Huang, X.; Li, B.; Li, C.; et al. Florence: A new foundation model for computer vision. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.11432. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, L.; Huang, R.; Hou, L.; Lu, G.; Niu, M.; Xu, H.; Liang, X.; Li, Z.; Jiang, X.; Xu, C.; et al. FILIP: Fine-grained interactive language-image pre-training. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.07783. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Fan, H.; Hu, R.; Feichtenhofer, C.; He, K. Scaling language-image pre-training via masking. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 7–24 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, X.; Zheng, Y.; Bao, J.; Zhang, T.; Chen, D.; Yang, H.; Zeng, M.; Zhang, W.; Yuan, L.; Chen, D.; et al. MaskCLIP: Masked self-distillation advances contrastive language-image pretraining. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Q.; Fang, Y.; Wu, L.; Wang, X.; Cao, Y. EVA-CLIP: Improved training techniques for CLIP at scale. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.15389. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, B.; Gu, G. Large-scale bilingual language-image contrastive learning. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.14463. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, H.; Bao, J.; Wu, Y.; He, X.; Li, T. SegCLIP: Patch aggregation with learnable centers for open-vocabulary semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.; Hu, R.; Goswami, V.; Couairon, G.; Galuba, W.; Rohrbach, M.; Kiela, D. FLAVA: A foundational language and vision alignment model. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Wang, Z.; Vasudevan, V.; Yeung, L.; Seyedhosseini, M.; Wu, Y. CoCa: Contrastive captioners are image-text foundation models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2205.01917. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.H.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, H.; Yang, J.; Li, C.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, L.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, L.; Hwang, J. Grounded language-image pre-training. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, L.; Han, J.; Wen, Y.; Liang, X.; Xu, D.; Zhang, W.; Li, Z.; Xu, C.; Xu, H. DetCLIP: Dictionary-enriched visual-concept paralleled pre-training for open-world detection. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2209.09407. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Jiang, Z.; Guo, Z.; Yan, S.; Pan, J.; Dong, H.; Gao, P.; Li, H. Personalize segment anything model with one shot. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.03048. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Y.; Ge, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, X.; Shan, Y. Planting a SEED of vision in large language model. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.08041. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, T.; Liu, S.; Zeng, A. Grounded SAM: Assembling open-world models for diverse visual tasks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.14159. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Zeng, Z.; Ren, T.; Li, F.; Zhang, H.; Yang, J.; Li, C.; Yang, J.; Su, H.; Zhu, J.; et al. Grounding DINO: Marrying dino with grounded pre-training for open-set object detection. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.05499. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Zhang, J.; Fei, J.; Ge, Y.; Zheng, H.; Tang, Y.; Li, Z.; Gao, M.; Zhao, S.; Shan, Y.; et al. Caption anything: Interactive image description with diverse multimodal controls. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.02677. [Google Scholar]

- Lüddecke, T.; Ecker, A. Image segmentation using text and image prompts. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Cao, Y.; Wang, W.; Shen, C.; Huang, T. SegGPT: Segmenting everything in context. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.03284. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, X.; Yang, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, L.; Gao, J.; Lee, Y.J. Segment everything everywhere all at once. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.06718. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Z.; Gao, C.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, S.Q. Parameter-efficient fine-tuning for large models: A comprehensive survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.14608. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, P.; Geng, S.; Zhang, R.; Ma, T.; Fang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Qiao, Y.J. Clip-adapter: Better vision-language models with feature adapters. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2024, 132, 581–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Zhu, L.; Ding, C.; Cao, R.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Sun, L.; Mao, P.; Zang, Y. SAM fails to segment anything? SAM-adapter: Adapting SAM in underperformed scenes: Camouflage, shadow, and more. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.09148. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Loy, C.C.; Dai, B. Extract free dense labels from CLIP. In European Conference on Computer Vision; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, K.; Yang, J.; Loy, C.C.; Liu, Z. Learning to prompt for vision-language models. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2022, 130, 2337–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.; Zhao, W.; Chen, G.; Tang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Huang, G.; Zhou, J.; Lu, J. DenseCLIP: Language-guided dense prediction with context-aware prompting. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhang, P. RegionCLIP: Region-based language-image pre-training. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Li, Q.; Tao, X.; Guo, Y.; Gong, M.; Liu, T. CRIS: CLIP-driven referring image segmentation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.15174. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, W.; Li, S.; Yang, J. Scattering prompt tuning: A fine-tuned foundation model for SAR object recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Seattle, WA, USA, 17–18 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Zhang, X.; Pun, M.; Huang, B. MANet: Fine-Tuning Segment Anything Model for Multimodal Remote Sensing Semantic Segmentation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.11160. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Lu, W.; Yu, H.; Yin, D.; Sun, X.; Fu, K. TEA: A training-efficient adapting framework for tuning foundation models in remote sensing. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5648118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Zhan, Y.; Xiong, Z. Parameter-efficient transfer learning for remote sensing image–text retrieval. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, G.A.; Fendley, N.; Wilson, J.; Mukherjee, R. Functional map of the world. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, M.; Hughes, L.H.; Qiu, C.; Zhu, X. SEN12MS—A curated dataset of georeferenced multi-spectral Sentinel-1/2 imagery for deep learning and data fusion. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.07789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Xia, G.; Li, S.; Yang, W.; Yang, M.Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, L.; Li, D. On creating benchmark dataset for aerial image interpretation: Reviews, guidances, and million-aid. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 4205–4230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastani, F.; Wolters, P.; Gupta, R.; Ferdinando, J.; Kembhavi, A. SatlasPretrain: A large-scale dataset for remote sensing image understanding. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 2–6 October 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Cai, M.; Zhang, T.; Zhuang, Y.; Mao, X. EarthGPT: A universal multi-modal large language model for multi-sensor image comprehension in remote sensing domain. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.16822. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Yuan, J.; Wen, C.; Lu, X.; Li, X. RSGPT: A remote sensing vision language model and benchmark. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.15266. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, J.; Du, B.; Tao, D.; Zhang, L. Scaling-up remote sensing segmentation dataset with segment anything model. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.02034. [Google Scholar]

- Heidler, K.; Mou, L.; Hu, D.; Jin, P.; Li, G.; Gan, C.; Wen, J.; Zhu, X.X. Self-supervised audiovisual representation learning for remote sensing data. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 116, 103130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhao, T.; Guo, Y.; Yin, J. RS5M and GeoRSCLIP: A large scale vision-language dataset and a large vision-language model for remote sensing. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.11300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Xiong, Z.; Yuan, Y. RSVG: Exploring data and models for visual grounding on remote sensing data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5604513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Prabha, R.; Huang, T.; Wu, J.; Rajagopal, R. SkyScript: A large and semantically diverse vision-language dataset for remote sensing. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 20–27 February 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Z.; Xiong, Z.; Mou, L.; Zhu, X.X. ChatEarthNet: A global-scale image-text dataset empowering vision-language geo-foundation models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.11325. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, J.; Han, K.; Albanie, S. SATIN: A multi-task metadataset for classifying satellite imagery using vision-language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.11619. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Kang, J.; Gong, J. LuoJiaHOG: A hierarchy oriented geo-aware image caption dataset for remote sensing image-text retrieval. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.10887. [Google Scholar]

- Muhtar, D.; Li, Z.; Gu, F.; Zhang, X.; Xiao, P. LHRS-Bot: Empowering remote sensing with VGI-enhanced large multimodal language model. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.02544. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.; Pang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, T.; Wang, L.; Dang, B.; Lao, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, J.; Tan, Y.; et al. SkySenseGPT: A fine-grained instruction tuning dataset and model for remote sensing vision-language understanding. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.10100. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Sun, L.; Chen, X.; Gu, X.; Wang, Y. A survey of efficient fine-tuning methods for vision-language models-prompt and adapter. Comput. Graph. 2024, 119, 103885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Albrecht, C.M.; Zhu, X.X. Self-supervised vision transformers for joint sar-optical representation learning. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2022-2022 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium IGARSS, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 17–22 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://github.com/RubenGres/Seg2Sat (accessed on 12 October 2023).

- Espinosa, M.; Crowley, E.J. Generate your own Scotland: Satellite image generation conditioned on maps. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.16648. [Google Scholar]

- Khanna, S.; Liu, P.; Zhou, L.; Meng, C.; Rombach, R.; Burke, M.; Lobell, D.B.; Ermon, S. DiffusionSat: A generative foundation model for satellite imagery. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.03606. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, D.; Cao, X.; Hou, X.; Jiang, Z.; Liu, J.; Meng, D. CRS-Diff: Controllable generative remote sensing foundation model. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.11614. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.; Liu, C.; Liu, L.; Shi, Z.X.; Zou, Z. MetaEarth: A generative foundation model for global-scale remote sensing image generation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.13570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, A.; Millard, K.; Green, J.R. CROMA: Remote sensing representations with contrastive radar-optical masked autoencoders. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.00566. [Google Scholar]

- Akiva, P.; Purri, M.; Leotta, M. Self-supervised material and texture representation learning for remote sensing tasks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Chen, K.; Chen, H.; Shi, Z. Geographical knowledge-driven representation learning for remote sensing images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5405516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayush, K.; Uzkent, B.; Meng, C.; Tanmay, K.; Burke, M.; Lobell, D.; Ermon, S. Geography-aware self-supervised learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Wei, Y.; Liu, T.; Hou, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Liu, L. Predicting gradient is better: Exploring self-supervised learning for SAR ATR with a joint-embedding predictive architecture. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.15153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Chen, K.; Su, L.; Yan, C.; Xu, S.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, P.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, B. RSBuilding: Towards general remote sensing image building extraction and change detection with foundation model. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.07564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Gao, P.; Dong, H.; Yin, Z.; Wang, G.; Zhang, W.; Chen, H. Consecutive pre-training: A knowledge transfer learning strategy with relevant unlabeled data for remote sensing domain. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendieta, M.; Han, B.; Shi, X.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, C.; Li, M. Towards geospatial foundation models via continual pre-training. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 2–6 October 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Du, B.; Tao, D.; Zhang, L. Advancing plain vision Transformer toward remote sensing foundation model. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5612822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.J.; Fleming, L.; Geach, J.E. EarthPT: A time series foundation model for earth observation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.07207. [Google Scholar]

- Jakubik, J.; Roy, S.; Phillips, C.; Fraccaro, P.; Godwin, D.; Zadrozny, B.; Szwarcman, D.; Gomes, C.; Nyirjesy, G.; Edwards, B.; et al. Foundation models for generalist geospatial artificial intelligence. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.18660. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.; Huo, C.; Xiang, S. Siamese InternImage for Change Detection. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xiao, J.; Guo, Y.; Jiang, P.; Yang, H.; Wang, F. HSIDMamba: Exploring bidirectional state-space models for hyperspectral denoising. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.09697. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, G.; Xiong, F.; Lu, J.; Zhou, J. SSUMamba: Spatial-spectral selective state space model for hyperspectral image denoising. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.01726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Wu, X.; Chen, H.; Chen, X.; He, X. RSDehamba: Lightweight vision mamba for remote sensing satellite image dehazing. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.10030. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Jiang, K.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Lin, C. Frequency-assisted Mamba for remote sensing image super-resolution. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.04964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Cao, K.; Yan, K.; Li, R.; Xie, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, M. Pan-Mamba: Effective pan-sharpening with state space model. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.12192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Chen, B.; Liu, C.; Li, W.; Zou, Z.; Shi, Z.X. RSMamba: Remote sensing image classification with state space model. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 8002605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Hong, D.; Li, C.; Chanussot, J. SpectralMamba: Efficient mamba for hyperspectral image classification. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.08489. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Zhang, X.; Peng, Z.; Zhang, T.; Jia, X.; Jiao, L. S2Mamba: A spatial-spectral state space model for hyperspectral image classification. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.18213. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Chen, Y.; He, X. Spectral-spatial Mamba for hyperspectral image classification. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.18401. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, J.; Zhou, J.; Wang, J.; Ye, P.; Fan, J. DualMamba: A lightweight spectral-spatial Mamba-convolution network for hyperspectral image classification. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.07050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Cai, Y.; Fang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Chen, C.; Fan, L.; Nguyen, A. Samba: Semantic segmentation of remotely sensed images with state space model. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.01705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhang, X.; Pun, M.O. RS3Mamba: Visual state space model for remote sensing image semantic segmentation. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 6011405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, T.; Singh, J.; Bhartari, Y.; Jarwal, R.; Singh, S.; Singh, S. SOAR: Advancements in small body object detection for aerial imagery using state space models and programmable gradients. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.01699. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Song, J.; Han, C.; Xia, J.; Yokoya, N. ChangeMamba: Remote sensing change detection with spatio-temporal state space model. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.03425. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, K.; Liu, C.; Chen, H.; Zou, Z.; Shi, Z.X. CDMamba: Remote sensing image change detection with Mamba. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.04207. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Cao, X.; Meng, D. A new learning paradigm for foundation model-based remote-sensing change detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 62, 5610112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Yin, H.; Li, H.; Li, W.; Zhang, Y.; Khan, S.; Khan, F.S. Dual hyperspectral Mamba for efficient spectral compressive imaging. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.00449. [Google Scholar]

- Cong, Y.; Khanna, S.; Meng, C.; Liu, P.; Rozi, E.; He, Y.; Burke, M.; Lobell, D.; Ermon, S. Satmae: Pre-training transformers for temporal and multi-spectral satellite imagery. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 197–211. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Wang, P.; Lu, W.; Zhu, Z.; Lu, X.; He, Q.; Li, J.; Rong, X.; Yang, Z.; Chang, H.; et al. RingMo: A remote sensing foundation model with masked image modeling. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5612822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, K.; Seo, J.; Lee, T. A billion-scale foundation model for remote sensing images. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.05215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhtar, D.; Zhang, X.; Xiao, P.; Li, Z.; Gu, F. CMID: A unified self-supervised learning framework for remote sensing image understanding. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5607817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L, W.; Yang, W.; Hou, Y.; Liu, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, X. SARATR-X: A foundation model for synthetic aperture radar images target recognition. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.09365. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, J.; Xu, M.; Liu, L.; Wang, D.; Gao, E.; Han, C.; Guo, H.; Du, B.; Tao, D.; et al. MTP: Advancing remote sensing foundation model via multi-task pre-training. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 11632–11654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Stewart, A.J.; Hanna, J.; Borth, D.; Papoutsis, I.; Saux, B.L.; Camps-Valls, G.; Zhu, X.X. Neural plasticity-inspired multimodal foundation model for earth observation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.15356. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.; Lao, J.; Dang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, L.; Ru, L.; Zhong, L.; Huang, Z.; Wu, K.; Hu, D.; et al. Skysense: A multi-modal remote sensing foundation model towards universal interpretation for earth observation imagery. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–18 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Han, B.; Zhang, S.; Shi, X.; Reichstein, M. Bridging remote sensors with multisensor geospatial foundation models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–18 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, D.; Zhang, B.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Li, C.; Yao, J.; Yokoya, N.; Li, H.; Ghamisi, P.; Jia, X.; et al. SpectralGPT: Spectral remote sensing foundation model. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.07113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Z.; Gu, Y.; Liu, T. Generative ConvNet foundation model with sparse modeling and low-frequency reconstruction for remote sensing image interpretation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5603816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Lei, J.; Zhang, J.; Xie, W.; Li, Y. SwiMDiff: Scene-wide matching contrastive learning with diffusion constraint for remote sensing image. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5613213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Gong, Y.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Y. Generic knowledge boosted pre-training for remote sensing images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5605913. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Hern’andez, H.H.; Albrecht, C.M.; Zhu, X.X. Feature guided masked autoencoder for self-supervised learning in remote sensing. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.18653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Y. CtxMIM: Context-enhanced masked image modeling for remote sensing image understanding. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.00022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Albrecht, C.M.; Braham, N.A.A.; Liu, C.; Xiong, Z.; Zhu, X.X. DeCUR: Decoupling common and unique representations for multimodal self-supervision. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.05300. [Google Scholar]

- Nayak, N.V.; Yu, P.; Bach, S.H. Learning to compose soft prompts for compositional zero-shot learning. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.03574. [Google Scholar]

- Mall, U.; Phoo, C.P.; Liu, M.K.; Vondrick, C.; Hariharan, B.; Bala, K. Remote sensing vision-language foundation models without annotations via ground remote alignment. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.06960. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, T.; Song, L.; Ge, Y.; Liu, W.; Wang, X.; Shan, Y. YOLO-World: Real-time open-vocabulary object detection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.17270. [Google Scholar]

- Bazi, Y.; Bashmal, L.; Al Rahhal, M.M.; Ricci, R.; Melgani, F. RS-LLAVA: A large vision-language model for joint captioning and question answering in remote sensing imagery. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Xiong, Z.; Yuan, Y. SkyEyeGPT: Unifying remote sensing vision-language tasks via instruction tuning with large language model. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.09712. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Chen, D.; Guan, Z.; Zhou, X.; Zhu, J.; Zhou, J. RemoteCLIP: A vision language foundation model for remote sensing. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5622216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckreja, K.; Danish, M.S.; Naseer, M.; Das, A.; Khan, S.H.; Khan, F.S. GeoChat: Grounded large vision-language model for remote sensing. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Seattle, WA, USA, 17–18 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, C.; Wu, J.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Sun, J.; Li, W.; Wang, S.; Feng, L.; Xia, G.-S.; et al. H2RSVLM: Towards helpful and honest remote sensing large vision language model. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.20213. [Google Scholar]

- Vivanco Cepeda, V.; Nayak, G.K.; Shah, M. GeoCLIP: CLIP-inspired alignment between locations and images for effective worldwide geo-localization. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.16020. [Google Scholar]

- Klemmer, K.; Rolf, E.; Robinson, C.; Mackey, L.; Rußwurm, M. SatCLIP: Global, general-purpose location embeddings with satellite imagery. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.17179. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Mai, G.; Mu, L.; Hu, M.; Li, S. Text2Seg: Remote sensing image semantic segmentation via text-guided visual foundation models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.10597. [Google Scholar]

- Osco, L.P.; Wu, Q.; Lemos, E.L.; Gonçalves, W.N.; Ramos, A.P.; Li, J.; Junior, J.M. The segment anything model (SAM) for remote sensing applications: From zero to one shot. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.16623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liang, F.; Chen, L.; Liu, H.; Song, Q.; Vivone, G.; Chanussot, J. MeSAM: Multiscale enhanced segment anything model for optical remote sensing images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5623515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Zhou, R.; Zhang, W.; Feng, Y.; Diao, W.; Fu, K.; Sun, X. RingMo-SAM: A foundation model for segment anything in multimodal remote-sensing images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5625716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Liu, C.; Liu, Z.; Chen, H.; Wu, Y.; Zou, Z.; Sh, Z. Multi-view remote sensing image segmentation with SAM priors. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.14171. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Chen, W.; Chen, C. BSDSNet: Dual-stream feature extraction network based on segment anything model for synthetic aperture radar land cover classification. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, B.; Cheng, H.; Yang, Q.; Wang, Y.; He, X. Adapting segment anything model to aerial land cover classification with low-rank adaptation. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 2502605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Chen, N.; Li, M.; Mao, S.; Zhang, H.; Fan, Y.; Liu, H. A point cloud segmentation method for dim and cluttered underground tunnel scenes based on the segment anything model. Remote Sens. 2023, 16, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Wu, W.; Wan, G.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, W.; Yin, H.; Tian, Z.; Liu, S. Segment anything model-based building footprint extraction for residential complex spatial assessment using LiDAR data and very high-resolution imagery. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetang, C.; Xue, H.; Le, C.; Yue, T.; Wang, W.; He, Y. Segment anything model for road network graph extraction. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.16051. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.; Liu, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, H.; Li, W.; Zou, Z.; Shi, Z.X. RSPrompter: Learning to prompt for remote sensing instance segmentation based on visual foundation model. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 62, 4701117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wu, W.; Yang, W.; Qin, H.; Wu, X.; Mao, X. Make segment anything model perfect on shadow detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 4410713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Song, H.; Zhang, K.; Dong, G.; Liang, L.; Zhao, Y. Segment anything model guided semantic knowledge learning for remote sensing change detection. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2024-2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 14–19 April 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Du, S.; Tang, S.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Guo, R. Tree-GPT: Modular large language model expert system for forest remote sensing image understanding and interactive analysis. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.04698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Yu, Y.; Li, L.; Li, L. Exploring semantic prompts in the segment anything model for domain adaptation. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://github.com/Douglas2Code/Text2Seg (accessed on 7 June 2023).

- Zheng, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Zhang, L.; Ermon, S. Segment any change. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.01188. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, L.; Zhu, K.; Peng, D.; Tang, H.; Yang, K.; Bruzzone, L. Adapting segment anything model for change detection in VHR remote sensing images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5611711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Liu, C.; Li, W.; Liu, Z.; Chen, H.; Zhang, H.; Zou, Z.; Shi, Z.X. Time travelling pixels: Bitemporal features integration with foundation model for remote sensing image change detection. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.16202. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, L.; Chen, K.; Liu, C.; Zhou, F.; Shi, Z.X. Semantic-CC: Boosting remote sensing image change captioning via foundational knowledge and semantic guidance. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.14032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, Q.; Liu, J.; Xiong, H. ALPS: An auto-labeling and pre-training scheme for remote sensing segmentation with segment anything model. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.10855. [Google Scholar]

- Mei, L.; Ye, Z.; Xu, C.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Lei, C.; Yang, W.; Li, Y. SCD-SAM: Adapting segment anything model for semantic change detection in remote sensing imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5626713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]