Highlights

- What are the main findings?

- ISA in regions such as Asia and Africa has expanded faster than the global average. Developed countries had lower expansion rates. Hotspot areas were mainly distributed in Asia and eastern South America in the early stage of the study period and appeared in eastern Europe in the later stage. Edge expansion is the main pattern. Upper-middle-income countries have the largest area of ISA expansion, followed by high-income countries. Cities in developed countries have more infilling expansion; cities in developing countries have more edge expansion.

- At the continent and country level, social factors, especially GDP, have the greatest impact on ISA change. At the city level, natural factors play a more influential role.

- What is the implication of the main finding?

- The findings highlight a significant and accelerating disparity in ISA expansion patterns between different regions. This implies that different regions need to adopt different urban planning policies to promote sustainable and compact urban growth.

- The study conducted a comprehensive temporal and spatial analysis of the ISA changes, expansion patterns, and driving factors of ISA. By integrating natural and socio-economic factors, the study captured the key factors influencing ISA from multiple perspectives and spatial levels.

Abstract

The change in impervious surface area (ISA) is an important factor reflecting urban expansion. This study used the global ISA dataset to analyze the spatiotemporal changes in ISA from 2001 to 2020 worldwide, explored the hotspots and patterns of ISA expansion, and analyzed the natural and socio-economic factors affecting ISA changes at three different levels, namely the continent, country, and city levels, by using the RF-SHAP method. The results are as follows: (1) The ISA has grown by 0.94 million km2. (2) ISA in regions such as Asia and Africa has expanded faster than the global average. Developed countries had lower expansion rates. The hotspots of the ISA change rate were relatively concentrated in eastern Asia. Hotspot areas were mainly distributed in Asia and eastern South America in the early stage of the study period and appeared in eastern Europe in the later stage. (3) Edge expansion is the main pattern. Upper-middle-income countries have the largest area of ISA expansion, followed by high-income countries. Cities in developed countries have more infilling expansion; cities in developing countries have more edge expansion. (4) At the continent and country level, social factors, especially GDP, have the greatest impact on ISA change. At the city level, natural factors play a more influential role.

1. Introduction

1.1. Global Urbanization

Urbanization is one of the most significant features of modern human social development [1,2]. Urbanization is characterized by the evolution of urban form (e.g., rapid evolution of territorial landscapes, population agglomeration, etc.) and the evolution of urban functions (e.g., economic growth) [3,4]. According to the World Cities Report 2022, global urbanization is projected to increase from 56% in 2021 to 68% by 2050, with urban areas absorbing nearly all future population growth. The United Nations reports that the number of cities with at least 1.01 million inhabitants was 512 in 2022 and is expected to reach 662 by 2030 [5].

1.2. Urbanization and ISA

Urban expansion is the result of regional socio-economic and ecological conditions [6,7]. In the context of large-scale urban expansion, the urban structure has become complicated. Urbanization has brought great convenience to people’s lives and at the same time brought many unprecedented problems. Firstly, the increasing number of plots and places with complex structure and function poses a challenge for urban management [8]. It is more difficult to perceive the structural system of the urban area under the urban vision, and the cost of traveling for people has greatly increased [9]. Secondly, the high rate of urban population growth puts a huge burden on urban resources, and shortages and uneven distribution of production and living resources occur from time to time [10]. Thirdly, the development and utilization of urban construction land often takes up a large amount of arable land and ecological land, with urban space encroaching on agricultural and ecological space [11]. This may cause further deterioration of the urban environment and lead to problems such as air pollution [12], water pollution, and solid waste pollution [13,14]. At the same time, with the rapid expansion of urban areas, it is difficult to dissipate heat from cities, creating an urban heat island effect that affects the climate [15], hydrological processes, and ecosystem health of cities and neighboring areas [16,17]. Impervious surface area (ISA) refers to any material that prevents water from seeping down to the ground [18], such as roads, squares, roofs, and artificial greenhouses composed of concrete, asphalt, plastic, and metal [19]. An important feature of rapid urbanization is the replacement of the natural surface by a large number of impervious surface landscapes, which has a profound impact on the regional ecological environment and the quality of life of residents. With the rapid advancement of global urbanization, ISAs have replaced natural surfaces such as vegetation, cropland, and bare soil as the typical urban surface type. By blocking evapotranspiration from natural surfaces, impervious surfaces lead to higher surface temperatures in towns and cities, exacerbating the heat island effect, which directly or indirectly affects the ecosystem and causes ecological quality problems such as increased loss of cropland and reduced biodiversity [20,21,22]. Therefore, most existing studies on urban sprawl use impervious surface data [23]. Therefore, monitoring the dynamic changes in ISA on a large scale and over a long period of time, as well as accurately quantifying its multidimensional driving mechanisms, is of great significance for promoting the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and advancing the construction of smart cities and ecological civilization.

Currently, most scholars’ comparative analyses of ISA expansion characteristics are in both the temporal and spatial dimensions. In the temporal dimension, most studies have analyzed the changes in the expansion area and expansion patterns at different times. Early studies in the 1990s primarily focused on quantifying urban expansion using remote sensing data. For instance, Elvidge et al. utilized nighttime light data to map global urban expansion, highlighting the rapid growth of impervious surfaces in developing regions [24]. In the 2000s, advancements in satellite imagery, such as Landsat and MODIS, enabled more detailed analyses of ISA dynamics. Schneider et al. developed a global urban land use dataset, revealing a 58% increase in urban areas between 1970 and 2000 [25]. Recent studies have leveraged machine learning and big data analytics to model future urban expansion scenarios. Liu et al. projected that global ISA could increase by 1.2 million km2 by 2050, driven by population growth and economic development [26]. In the spatial dimension, features such as expansion patterns, spatial distribution, and spatial correlation of multiple cities or urban agglomerations were revealed [27]. Studies have highlighted regional disparities in ISA expansion. In developed countries, urban expansion has slowed due to land use regulations and declining population growth. For example, Seto et al. found that North America and Europe experienced modest urban growth compared to Asia and Africa [28]. In contrast, developing regions, particularly in Asia, have witnessed rapid ISA expansion. Zhang et al. analyzed urban growth in China, showing that ISA increased by 80% between 1990 and 2015, primarily due to economic reforms and infrastructure development [29].

The study of urban environmental drivers and the drivers of ISA change has become increasingly important. Machine learning (ML) methods, especially in recent years, have been increasingly used in urban research because of their robust prediction ability [30]. Compared with traditional methods such as geographically weighted regression and the geodetector method, ML has more advantages in dealing with complex nonlinear relationships [31], and through interpretation tools, it can clearly show the relationships of various variables. It also provides the significant advantage of a unified and quantitative global and local interpretation framework, which effectively overcomes the limitations of traditional models such as sensitivity to multiple collinearity and dependence on subjective parameter setting [32]. This provides a deeper insight into the research on ISA change. Among ML approaches, the Random Forest (RF) approach has been widely used in this field. Compared with other ML models, RF-SHAP has the advantages of a more robust model, being less prone to overfitting, being insensitive to hyperparameters, and having more credible interpretation results, especially when dealing with geographical data with noise and collinearity. It ensures the stability and reliability of driver factor interpretation [33]. For example, Liu et al. [34] used RF to analyze the driving factors of urban expansion in the Fujian Delta and found that the annual average rainfall and temperature are the most influential factors. The SHAP [35] method is mainly used to evaluate the importance of individual features based on the total effect. RF combined with SHAP has also been widely used in urban studies. For example, Deng et al. [36] utilized RF regression and SHAP to explore the driving factors of urban wetland park cooling effects. The results showed that the percentage of water bodies inside parks and park area were the most important driving factors. Hong et al. [37] used RF regression models and the SHAP method to quantitatively analyze nonlinear relationships and interaction effects of urban heat islands (UHIs). The results indicated that meteorological variables, particularly regional air temperature, significantly influenced UHI intensity during both daytime and nighttime. These studies demonstrate that RF and SHAP can effectively identify and quantify the importance of various driving factors, providing valuable insights for urban planning and environmental management.

1.3. Problems and Objectives

At present, many scholars have studied the impacts of urbanization or ISA changes, such as the impacts on the environment, climate, ecosystem, and other aspects. However, few scholars have studied what factors affect the change in ISA. Although some studies focused on the driving factors of ISA changes, most of them were carried out in relatively small areas, such as a specific city. This study, from a more comprehensive perspective, analyzed what influences the change in ISA from three different levels: continents, countries, and cities.

Using a global ISA dataset, the study first analyzed the temporal and spatial expansion of the global ISA from 2001 to 2020. Then we analyzed the global ISA expansion patterns over 20 years and every 5 years. In order to reveal the differences in ISA expansion patterns in regions with different economic levels, the study further classified ISA expansion patterns according to the national income levels given by the World Bank. Finally, combined with geodata and statistical data, the study explored the driving factors of ISA at the continent, country, and city levels by using the RF method and SHAP value, so as to compare their similarities and differences.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

Tsinghua University’s Global Artificial Impervious Area (GAIA) dataset was used to identify urban built-up areas. Gong et al. mapped annual GAIA from 1985 to 2020 using the full archive of 30 m resolution Landsat images [38]. With ancillary datasets, including the nighttime light data and the Sentinel-1 Synthetic Aperture Radar data, Gong et al. improved the performance of their previously developed algorithm in arid areas. The mean overall accuracy is higher than 90%, which matches our research needs.

Driving factor data include geographic data and statistical data. The DEM data used in the driving factor exploration are from GEBCO (https://download.gebco.net/ (accessed on 7 March 2025)), with a spatial resolution of 15 arc-seconds (about 450 m). The slope is calculated from the DEM. The temperature and precipitation data are from Terraclimate [39] with a spatial resolution of 1/24° (about 4 km). The annual data are calculated by adding the monthly data. The global road network data are from OpenStreetMap (OSM). The global road density is obtained after processing.

Statistical data like GDP, population data, and employment rate data at the national level are all from the World Bank (https://data.worldbank.org (accessed on 21 April 2025)). The Human Development Index (HDI) comes from the HDI index of the United Nations human development report (https://hdr.undp.org/ (accessed on 26 May 2025)). The HDI consists of three parts: health, knowledge acquisition, and living standards. It is used to supplement the GDP measurement system to define the development level of a country. The data at the continent level are obtained after processing. GDP data at the city level are from local government websites. Population data are from the Population Stat website (https://populationstat.com/ (accessed on 23 May 2025)). A summary of the data information is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Data sources.

2.2. Methods

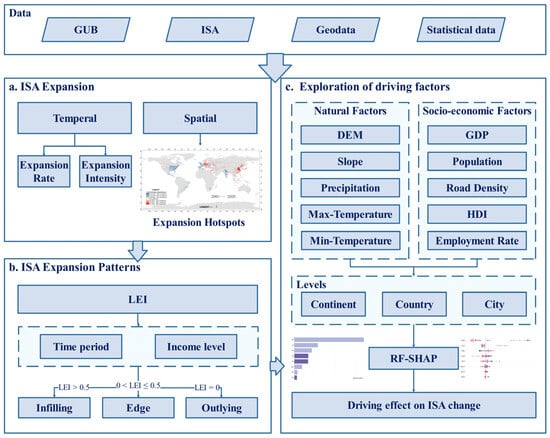

The specific process of the study was as follows: (1) For data preprocessing, the study resampled ISA data to 1 km resolution for spatial analysis and set all spatial data coordinate systems to WGS-1984. Then we extracted the annual changes in ISA from 2001 to 2020. (2) The study calculated the change rate and intensity of ISA in global and all continents from 2001 to 2020 to find the change rules of ISA. The entire region was divided into 10 km × 10 km grids in space. The change rate of ISA in each grid was calculated. Then we analyzed the cold spot and hotspot areas. The spatial distribution of cold spots and hotspots of ISA change rate in 2001–2020, 2001–2005, 2006–2010, 2011–2015, and 2016–2020 was obtained. (3) The Landscape Expansion Index (LEI) of each ISA area was calculated, and the ISA expansion patterns were divided into infilling expansion, edge expansion, and outlying expansion. The ISA expansion patterns were counted at a time interval of five years. In combination with the global national income level data, the study analyzed the expansion patterns of ISA in regions with different income levels from 2001 to 2020. The study also conducted statistical and mapping analysis on the expansion patterns of the 12 selected cities. (4) For the raster data, the spatial calculation was carried out at the continent, country, and city levels. We used the built-up area boundary data (GUB) to mask the driving factor data, in order to avoid interference from socio-economic and natural conditions outside of urban built-up areas in exploring ISA driving factors. Combined with the statistical data, the driving factors of ISA changes at all levels were analyzed by using the RF-SHAP method. Firstly, we used the grid search method to find the best parameters of the RF model when building the model. Then we used the parameters to calculate and rank the importance of each factor, and we combined these results with SHAP to explore whether the effect of each factor on ISA is positive or negative. The overall structure of the study is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research framework.

The study integrated multiple types of data, including raster, vector, and statistical data, to investigate and summarize the global trend of ISA changes over a 20-year time scale. Many existing studies may only analyze driving factors at a single scale, such as global or specific administrative regions, which may overlook the scale dependence of driving factors. We explore the driving factors of ISA changes at different spatial scales by constructing a complete global, continent, country, and city framework in order to capture the different manifestations of ISA change driving factors at different spatial scales.

2.2.1. Trends of ISA Expansion

Expansion rate is a quantity that characterizes the speed of ISA expansion and indicates the size of the ISA expansion area per unit of time.

The formula indicates the expansion rate. is the ISA at the end of the study, is the ISA at the beginning of the study, and T indicates the time interval of the study.

The expansion intensity index refers to the proportion of the ISA expansion in the unit time range and in a specific study space, characterizing the degree and strength of ISA expansion, with the following formula [40]:

The hotspot analysis [41] reflects the spatial clustering of new growth land. The Getis–Ord spatial correlation index was used to identify the distribution of high-value clusters (hotspot areas) and low-value clusters (cold spot areas) of the spatial growth of ISA. It is calculated as follows:

where n is the number of raster pixels in the study area; and are the ISA rate of change; is the mean value of the ISA rate of change; is the spatial weight matrix for recording the proximity of the analysis unit; when the distance or spatial proximity of the two elements is within the established range, the weight value in the matrix is set to 1, and the weight value beyond the range is set to 0. In the results of the hotspot analysis, if the Z value is negative and smaller, it indicates that the possibility of the point being a cold point is higher; if the Z value is positive and larger, it indicates that the possibility of the point being a hotspot is higher; and if the Z value tends to be 0, there is no obvious spatial clustering.

In contrast to directly calculating the rate of change, hotspot analysis reflects persistent changes in ISA [42], such as when the ISA continues to expand at a faster rate in a particular region. In this study, the land was divided into grids of 10 km × 10 km, and the rate of change in ISA in each grid was calculated to analyze cold spots and hotspots.

2.2.2. Patterns of ISA Expansion

The Landscape Expansion Index (LEI) is a widely used spatial metric for quantifying the patterns of urban or impervious surface expansion. It was developed to classify expansion types into three categories: infilling expansion, edge expansion, and outlying expansion, based on the spatial relationship between newly developed patches and existing urban areas [43]. The LEI is particularly useful for understanding the dynamics of urban expansion and its environmental impacts.

The LEI is calculated using the following formula:

where is the area of the newly developed patch that does not overlap with the existing ISA area. is the area of the newly developed patch that overlaps with the existing ISA area. LEI calculation results are between 0 and 1. The area with LEI = 0 is outlying expansion. The area with 0 < LEI ≤ 0.5 is edge expansion. The area with LEI > 0.5 is infilling expansion.

In order to explore the similarities and differences of ISA expansion area and patterns under different economic development levels, the study compared the ISA expansion patterns of countries and regions with different income levels by using the global national income level data.

2.2.3. Exploration of Driving Factors

In this study, 10 variables, including natural and socio-economic factors, were chosen as driving factors. Natural factors included DEM, slope, precipitation, maximum temperature, and minimum temperature; socio-economic factors included GDP, population, road density, HDI, and employment rate. The suite of driving factors is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Driving factors of ISA.

According to the availability of data, the driving factors at the country level exclude the employment rate, and the driving factors at the city level exclude the employment rate and HDI. In the exploration at the city level, according to the ranking of global cities by Oxford Economics [44], GDP, and population of cities, 12 cities, namely New York, Los Angeles, Tokyo, Paris, London, Shanghai, Beijing, Houston, Shenzhen, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Sydney, were selected as representative samples.

The Random Forest (RF) algorithm is a powerful ML method widely used for driving factor analysis in environmental and urban studies. It is an ensemble learning technique that constructs multiple decision trees during training and outputs the mode of the classes or the mean prediction of the individual trees [45]. RF is particularly effective for handling high-dimensional data, capturing nonlinear relationships, and evaluating the importance of driving factors.

The RF model is used to solve the issue of spatial linear correlation of driving factors, while quantifying factor weights and selecting dominant ones. RF is a natural nonlinear modeling tool that integrates numerous decision trees for intelligent combination prediction [46]. First, the influential factors were used as spatially independent variables, and the change in ISA was used as the spatially dependent variable. Next, classification and regression tree operations were carried out to generate the out-of-bag (OOB) data, based on which the RF model can calculate the importance of the input variables, which is represented by the mean decrease in accuracy (). The larger the value, the more significant the variable is [47]. is calculated using the following formula:

where represents the reduced value of the average accuracy of variable , is the number of decision trees, is the out-of-bag error of decision tree , and is the out-of-bag error of decision tree after the random disruption of sample data outside the bag.

However, RF is not very effective at assessing positive and negative correlations between independent variables and dependent variables [45]. SHAP compensates for the weakness of RF in factor interpretability [48,49]. SHAP effectively utilizes these differences to calculate the positive or negative effects of each feature by using the Shapley value [35]. In summary, the combination of RF and SHAP can explore the positive or negative effects of factors on ISA change. The Shapley value of each feature is calculated using the following formula:

where is the Shapley value of th feature, is the set of all features, is the subsets of except the th feature, is the output of the model including the th feature, and is the output of the model excluding the th feature.

We used Stratified K-Fold Cross Validation with K = 5. We divided the entire dataset into 5 equally sized subsets (folds) randomly, keeping the distribution of each compromise target variable consistent with the original dataset. We performed 5 iterations. In each iteration, we used 4 subsets as the training set and the remaining 1 subset as the testing set. On each training set, we used grid search for hyperparameter tuning optimization. On each test fold, we calculated the SHAP value of the test sample using the best model trained on that fold.

Grid search exhaustively searches the defined parameter space, and it is comprehensive, simple, and easy to implement. But this method has certain limitations. The granularity of the grid determines the accuracy of the search. If the grid is too coarse, it may miss the optimal parameter combination; if the grid is too fine, the computational cost will be very high [50]. The data volume in this study is moderate, and the hyperparameter search space is relatively small. In this case, the computational cost of grid search is acceptable, and the efficiency advantage of Bayesian optimization is not significant.

3. Results

3.1. ISA Expansion

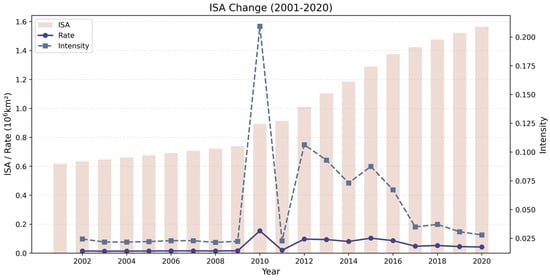

Global ISA continued to increase across the study period (2001–2020). The ISA has grown by 0.94 million km2. It was found that the rate of global ISA expansion did not increase consistently from 2001 to 2020. The rate of change in ISA was steady over the period 2001 to 2009 and reached a maximum in 2010. This may be related to the recovery of the global economy after the 2008 financial crisis, as the acceleration of urbanization and infrastructure construction may have led to the rapid growth of ISA. From 2010 to 2020, there were drastic fluctuations in the rate of ISA change; the average rate was higher than that in 2001–2009. Figure 2 shows the specific changes in ISA.

Figure 2.

Global ISA change (2001–2020).

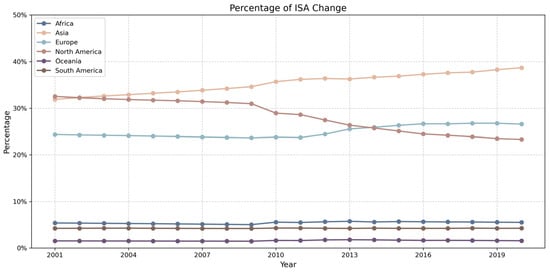

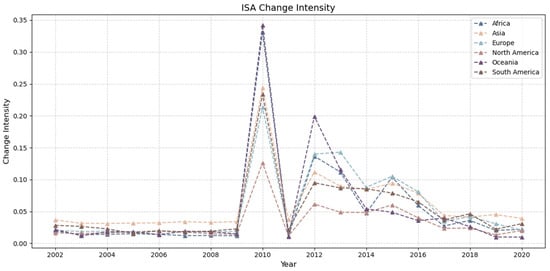

From 2001 to 2020, the percentage change in ISA of continents showed an increasing trend. Not surprisingly, Europe, North America, and Asia exhibited the largest percentage of ISA change (>20%) throughout the study period. Europe had a consistent rate of ISA change from 2001 to 2011. Europe’s rate of ISA change increased between 2011 and 2016 but leveled off from 2017 to 2020. The rate of ISA change in North America fell gradually between 2001 and 2009, after which it steadily declined. Asia had the fastest growth rate, accounting for 38.7% of the global ISA in 2020. This indicates that the urbanization process in Asia is rapid, and more land is being transformed into ISA. Before 2010, the intensity of ISA changes in Asia was the highest. After 2010, Africa, Oceania, and Europe gradually ranked higher. This may reflect the relatively mature level of urbanization and stable land use changes in North America. These data may be affected by land use policies and environmental protection measures in different regions. For example, some countries may have implemented stricter land use planning and urban expansion control measures, which may have affected the growth rate of ISA. The ISA change rate and intensity in different continents are shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Percentage of global ISA change in different continents.

Figure 4.

Global ISA change intensity in different continents.

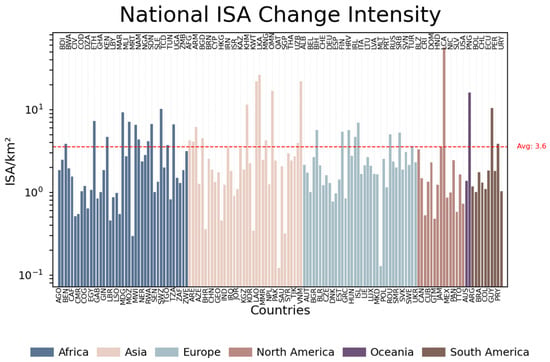

Figure 5 presents the global distribution of national ISA change intensity from 2001 to 2020. The overall mean intensity across all reporting nations is 3.6. The data reveal regional heterogeneity. The ISA change intensity is more balanced in African and European countries, while it is more variable in Asian and North American countries. Among the countries with the greatest ISA change intensity is Saint Lucia, located in North America. Asian countries such as Sri Lanka, Laos, and Vietnam also rank relatively high. Countries such as Papua New Guinea in Oceania; Guyana in South America; Oman and Cambodia in Asia; Eswatini, Madagascar, and Ethiopia in Africa; and Iceland in Europe also showed relatively high ISA change intensity. Overall, the ISA change intensity distribution across countries is likely influenced by variations in urbanization, infrastructure development, and economic activity. And it is also related to the ISA in each country at the beginning of the study.

Figure 5.

ISA change intensity in different countries (2001–2020).

The comprehensive and specific intensity values of the countries corresponding to the abbreviations can be [found in Appendix A, Table A1.

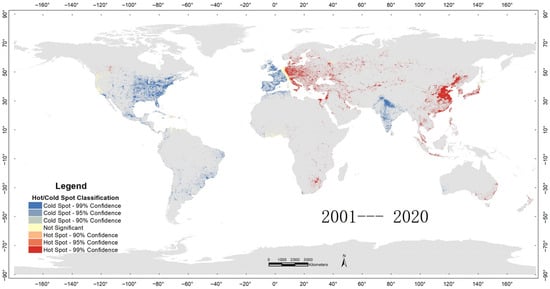

In terms of spatial distribution, ISA in regions such as Asia and Africa has expanded faster than the global average. In contrast, developed countries had lower expansion rates, but still showed an expansion trend (Figure 6). North America has long been dominated by cold spots, while the hotspots in eastern Asia, especially the east coast of China, and eastern Europe are relatively concentrated. The results of the spatial analysis showed that the hotspots of ISA change rate were relatively concentrated in eastern Asia and eastern Europe. In the early stage of the study period, hotspot areas were mainly distributed in Asia and eastern South America. In the later stage, the hotspots became scattered and appeared in eastern Europe.

Figure 6.

Hotspot analysis of ISA change intensity from 2001 to 2020.

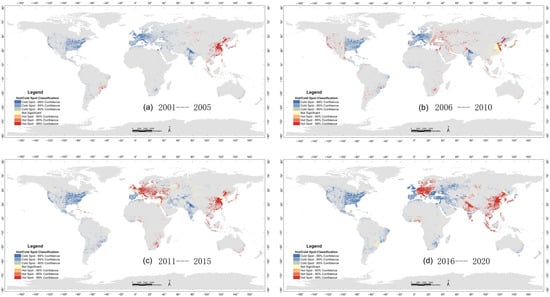

From 2001 to 2005, hotspots of ISA change were mainly concentrated in eastern China and eastern Brazil. From 2006 to 2010, hotspot areas appeared in northeastern China, the western United States, and the border region of Europe and Asia. From 2011 to 2015, there were more hotspot areas in eastern Europe, and hotspot areas appeared in southern Africa and Southeast Asia. From 2016 to 2020, hotspot areas appeared in northeastern India. The distribution of hot and cold spots at different time periods is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Hotspot analysis of ISA change intensity from (a) 2001 to 2005, (b) 2006 to 2010, (c) 2011 to 2015, and (d) 2016 to 2020.

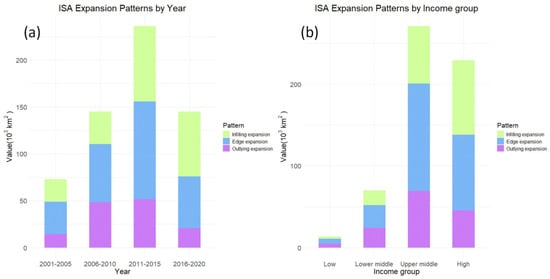

3.2. Patterns of ISA Expansion

Patterns of ISA expansion were divided into infilling expansion, edge expansion, and outlying expansion by calculating the LEI. Figure 8a indicates a shift in ISA expansion patterns over 20 years. The dominant pattern of global ISA expansion is edge expansion. From 2001 to 2020, global edge expansion accounted for 43.8% of total ISA expansion. Infilling expansion and outlying expansion accounted for 30.9% and 25.3% of total ISA expansion, respectively. The most significant growth in outlying expansion occurred between 2011 and 2015. Edge expansion also grew, but at a more moderate rate compared to outlying expansion. The increase in edge expansion between 2011 and 2015 indicates that cities are extending their urbanized areas along their peripheries during this period.

Figure 8.

ISA expansion patterns counted by year (a) and income group (b).

Patterns of ISA expansion by national income level are shown in Figure 8b. The results show that ISA increased most in upper-middle-income countries during the study period, followed by high-income countries. The expansion of ISA in lower-middle-income and low-income countries is smaller. Edge expansion is the main pattern of ISA expansion in upper-middle-income countries, while the proportion of infilling expansion in high-income countries is higher than that in upper-middle-income countries.

Table 3 shows the ISA expansion intensity of the 12 selected cities from 2001 to 2020. The total expansion areas of ISA in Beijing, Shanghai, and Sydney rank among the top three.

Table 3.

ISA expansion intensity of the 12 selected cities (2001–2020).

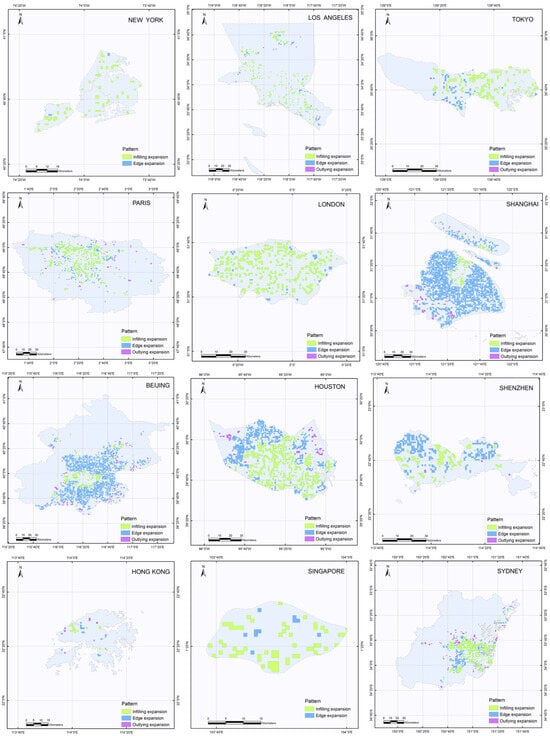

Figure 9 shows the ISA expansion patterns of 12 cities. It can be seen that Beijing, Shanghai, and Houston have extensive expansion areas. Among the three cities in the United States, the ISA expansion in Houston is more significant, with infilling expansion mainly in the central area and edge expansion in the periphery. Los Angeles and New York exhibited far less ISA expansion, indicating a steady rate of development. ISA expansion in Tokyo is mainly in the east. London’s expansion areas are more spread out across the city, with infilling expansion as the main type. The ISA expansion in Paris is mainly in the north-central region. The ISA expansion in Sydney is mainly along the eastern coast, with infilling expansion as the main type, followed by edge expansion. The patterns of Beijing and Shanghai are relatively similar: the central areas are mainly infilling expansion, surrounded by large areas of edge expansion, with many fewer outlying expansion areas scattered in the periphery. In Shenzhen, the edge expansion area is mainly in the northwest and northeast, while the infilling expansion area is mainly in the center, with a small portion in the southwest. The expansion of ISA in Hong Kong is mainly distributed in the north, with a small amount in the central region. The ISA expansion in Singapore is also sparse, with more infilling expansion than edge expansion.

Figure 9.

ISA expansion patterns of the 12 selected cities (2001–2020).

3.3. Exploration of Driving Factors

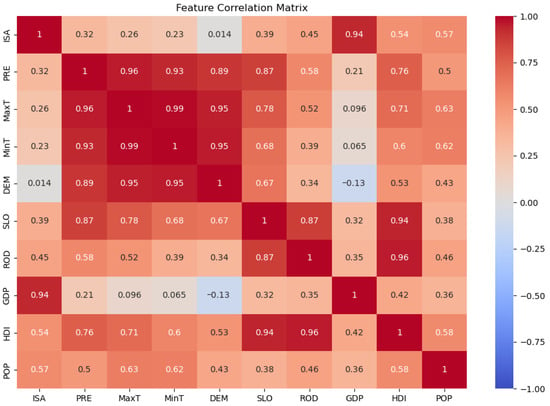

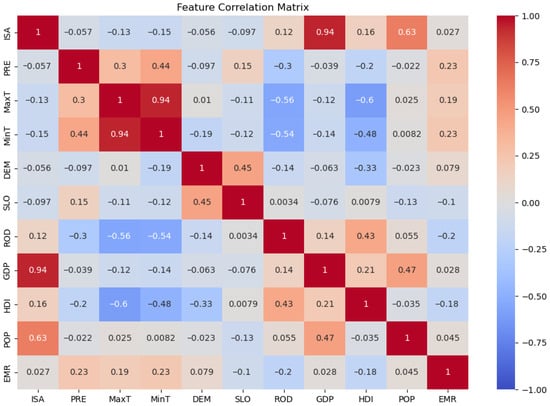

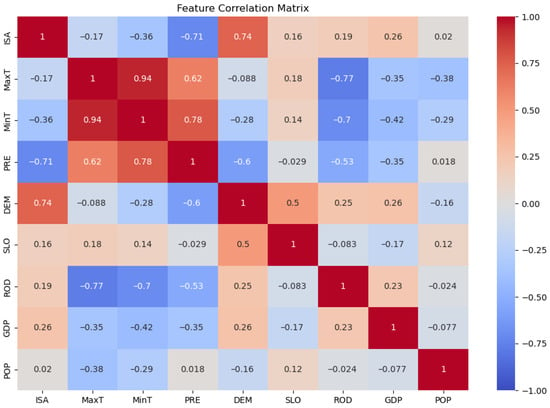

As shown in Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12, the correlations between driving factors and ISA were analyzed at the continent, country, and city levels. The Pearson correlation coefficients focus on linear relationships, while the RF-SHAP results reveal the overall contribution of the features in the model, including both linear and nonlinear relationships. Combining Pearson correlation coefficients and RF-SHAP results provides a more comprehensive understanding of the impact of features on model predictions, thus improving model interpretability [51]. It can be seen that the correlation of the same factor with ISA may be different at different levels. For example, precipitation and temperature factors show a positive correlation with ISA at the continent level but a negative correlation at the country and city levels.

Figure 10.

The heatmap of correlations between ISA and driving factors (continent level).

Figure 11.

The heatmap of correlations between ISA and driving factors (country level).

Figure 12.

The heatmap of correlations between ISA and driving factors (city level).

At the continent level, ISA was strongly (i.e., Pearson correlation coefficient > 0.5) correlated with three driving factors (GDP, 0.94; POP, 0.57; HDI, 0.54). At the country level, ISA was strongly correlated with two driving factors (GDP, 0.94; POP, 0.63). At the city level, ISA was strongly correlated with only one driving factor—DEM (0.74)

To avoid multicollinearity affecting the results, we calculated the variance inflation factor (VIF) values of each factor (Table 4).

Table 4.

Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values of factors.

When VIF > 10, it can be considered that the factor has obvious collinearity. It can be seen that all factors except MaxT and MinT have no obvious collinearity. MaxT and MinT have certain collinearity, but since temperature is an important natural factor, we chose to retain the factors.

The nonlinear effects of the factors on ISA were further explored using the RF-SHAP method. The grid search method was used to find the optimal parameters of the model (Table 5). For this purpose, the train set accounted for 15%, the test set accounted for 70%, and the validation set accounted for 15%.

Table 5.

The optimal parameters of the model.

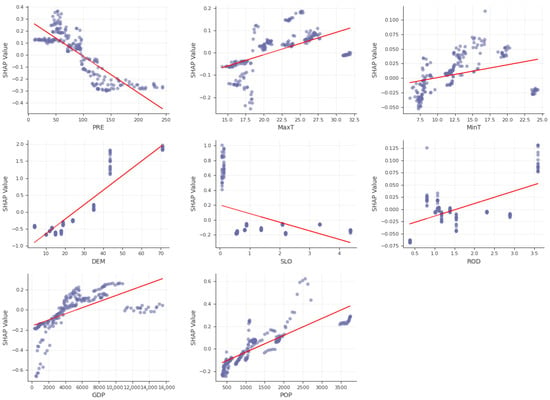

The study observed the importance ranking of each factor through bar charts and determined the impact of each individual factor on ISA through SHAP values. If low feature values cluster on the left side and the high values cluster on the right side in the SHAP swarm figure, it indicates that the factor has a positive effect on ISA changes. SHAP values > 0 in the partial dependency plots (PDPs) indicate that the sample point has a positive effect on ISA when taking this value. If the SHAP value of the sample increases with the increase in the horizontal axis, it indicates that the probability of ISA expansion also increases as the independent variable increases.

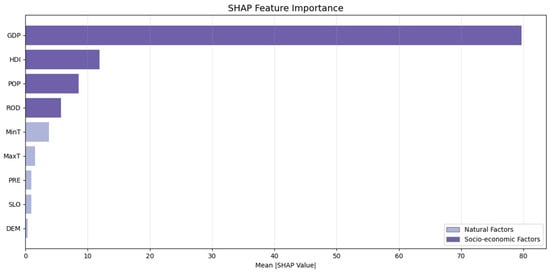

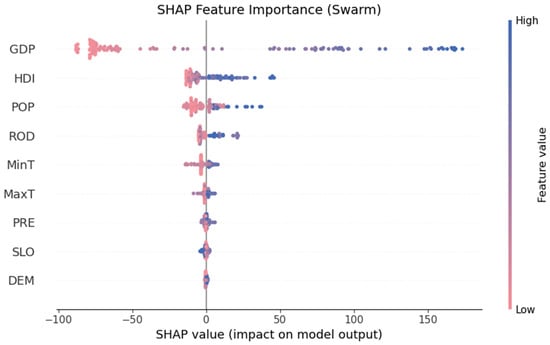

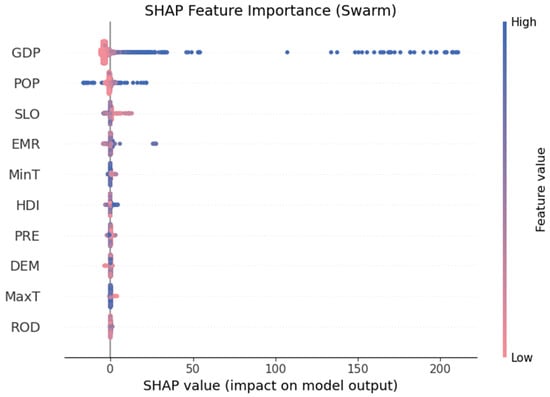

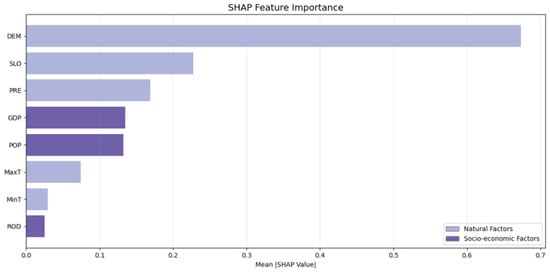

3.3.1. Exploration at the Continent Level

Figure 13 shows the importance ranking of driving factors at the continent level. It can be seen that GDP is the most influential factor, followed by the other socio-economic factors such as HDI, population, and road density. However, natural factors such as temperature, precipitation, slope, and DEM have little effect on the change in ISA at the continental level. Figure 14 shows whether these factors play a positive or negative role in the change in ISA. The figure shows that GDP, HDI, and population have a significant positive impact on ISA. Combined with PDP in Figure 15, other factors such as the maximum temperature, the minimum temperature, precipitation, and DEM also showed a positive correlation trend. Slope, on the other hand, was negatively correlated with ISA.

Figure 13.

The importance ranking of driving factors at the continent level.

Figure 14.

SHAP swarm figure at the continent level.

Figure 15.

The partial dependence plots at the continent level (red lines represent the trend of scatter distribution).

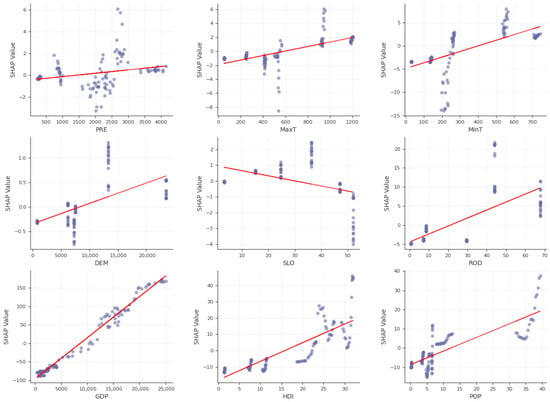

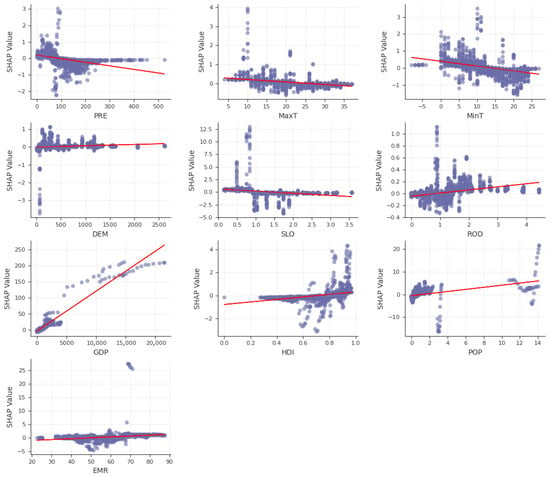

3.3.2. Exploration at the Country Level

As shown in Figure 16, the impact of GDP on ISA change is still dominant at the country level. Population ranks as the second most important driving factor at the country level. Different from the continental level, socio-economic factors are no longer the only factors affecting the ranking of ISA changes, but natural factors have emerged. For example, the effect of slope ranked third, and the lowest temperature ranked fifth. Among the socio-economic factors, the employment rate and HDI rank fourth and sixth, respectively. It can be seen from Figure 17 and Figure 18 that GDP still has a significant positive impact on ISA. Population and road density have a weak positive impact on ISA. The temperature and precipitation factors have a negative effect on ISA.

Figure 16.

The importance ranking of driving factors at the country level.

Figure 17.

SHAP swarm figure at the country level.

Figure 18.

The partial dependence plots at the country level (red lines represent the trend of scatter distribution).

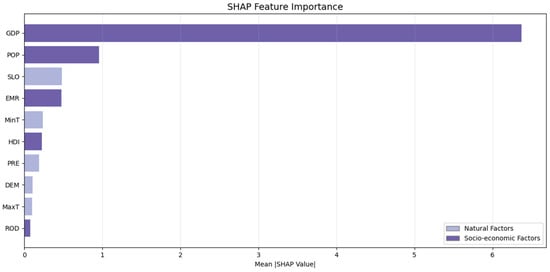

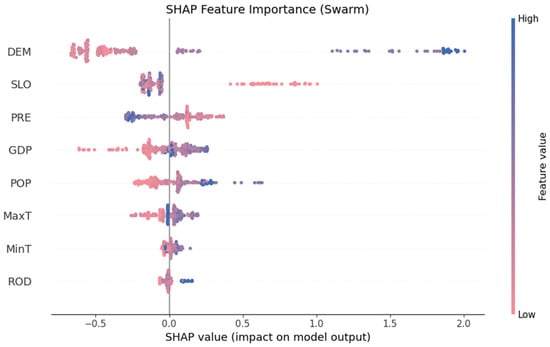

3.3.3. Exploration at the City Level

At the city level (Figure 19), socio-economic factors no longer occupy the most important position. DEM and slope ranked first and second. It can be inferred that in the study of small areas, the influence of topographic factors is more important. Precipitation ranked third. GDP and population ranked fourth and fifth, while road density ranked last. As can be seen from Figure 20 and Figure 21, DEM, GDP, population, maximum temperature, minimum temperature, and road density have a positive impact on ISA change, while slope and precipitation have a negative impact on ISA change at the city level.

Figure 19.

The importance ranking of driving factors at the city level.

Figure 20.

SHAP swarm figure at the city level.

Figure 21.

The partial dependence plots at the city level (red lines represent the trend of scatter distribution).

As shown in Figure 21, a fraction of the scatter points have low SHAP values for GDP > 10,000, suggesting that for samples with higher GDP, the probability of ISA expansion occurring is reduced. This situation can also be seen in the POP and MinT factors. The effect of these factors on ISA is not consistently positive. After reaching a certain value, the trend of ISA expansion with GDP, population, or temperature increases slows down.

4. Discussion

By observing global ISA changes, this study documented that there are differences in trends of ISA expansion in different regions. The intensity and rate of ISA expansion are higher in developing countries than in developed countries, and are higher in upper-middle-income countries than in countries with other income levels. It can be seen that the ISA expansion has a certain relationship with the development stage and economic level of a country. Countries and regions with rapid economic development are often accompanied by rapid urban development. This conclusion has been confirmed in many scholars’ studies. For example, Seto et al. [28] predict that nearly half of the increase in high-probability urban expansion globally is forecasted to occur in Asia, with China and India accounting for 55% of the regional total. Yue et al. [52] found that the ISA expansion and the resulting terrestrial carbon emissions of the world, developed countries, and developing countries from 1992 to 2018 can be attributed to socio-economic factors such as total population and urbanization rate, and they also found that the ISA expansion in China, Brazil, India, and Indonesia was mainly driven by urban population growth.

Further, our study explored the specific expansion patterns of ISA. Edge expansion dominated the ISA expansion pattern globally. The expansion patterns varied from city to city, which may be related to the policies of different countries or regions [53], the natural environment, and other factors [54]. United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 11 (SDG 11) focused on making cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable. This goal addressed the challenges arising from rapid urbanization while ensuring that urban development promotes economic growth. Our study indicates that countries undergoing rapid urbanization should establish scientific territorial spatial planning systems early—a critical step toward achieving SDG 11. For developed regions, policy priorities may shift to optimizing existing urban spaces and redeveloping underutilized areas. The expansion patterns and spatial distribution of cities across different regions are shaped by the combined effects of policy, natural environment, and socio-economic factors. For cities in China such as Beijing and Shanghai, urban development has been driven by market and policy. In the process of urban development, new industries and population are introduced, resulting in the continuous expansion of urban areas from the center [55]. The regional cooperation in the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area has provided synergy for the development of Shenzhen and Hong Kong. But Shenzhen’s urban expansion is more concentrated, while in Hong Kong, urban expansion is more fragmented [56,57]. Singapore has continued the spatial structure of a circular development around the central catchment and a south coast strip since 1971 [58], dominated by infilling expansion. In addition, the island geography of Singapore limits the horizontal expansion of the city in some ways, resulting in a three-dimensional urban structure. This should also be considered in future urban studies. The ISA in the Tokyo Metropolis expanded westward, guided by transportation. Residential and road land in the Tokyo metropolitan area accounts for a high proportion of the construction land [59]. Houston was experiencing rapid growth with significant ISA expansion. New York, on the other hand, has entered a stage of smoother development, and its ISA expansion was mainly infilling expansion, which was not significant. Los Angeles’s ISA expansion presented a multi-center, low-density situation [60], while the surrounding mountainous terrain constrained large-scale expansion in the periphery. London and Paris, as representatives of European cities, have limited outward urban expansion through their greenbelt policies [61]. As a result, ISA expansion in these two cities was dominated by infilling expansion within the city center. ISA expansion in Sydney was affected both by the topography of the harbor and population movements. For example, rising housing pressures due to population increase have prompted more population movement to the suburbs [62,63], generating edge expansion of ISA. ISA expansion more reflects the expansion of cities in the horizontal direction. Cities that have already gone through a phase of rapid development have more changes in the vertical direction [64]. This is also a situation worth considering in future studies. In conclusion, a city is a complex structure, and its expansion pattern is the result of a combination of multiple factors.

It is worth noting that at the continent level, ISA changes are positively correlated with precipitation; at the country and city levels, changes in ISA are negatively correlated with precipitation, especially at the city level. The reasons leading to this situation may be that at continent and country level, the relationship between ISA and precipitation is likely to be influenced by the distribution of climate and the high proportion of natural surfaces other than ISA in the continents, whereas at the city level, the proportion of ISA is greater, which inhibits evapotranspiration and hinders the formation of rainfall over the cities [65,66].

Some scholars believe that the economy and population are key factors affecting urban expansion. Based on the annual land use data of 286 cities in China from 2000 to 2015, Wu et al. [67] found that the driving factors of urban land expansion vary over time and space. In the early stages, policy support and initial land development were the main drivers, while economic and population factors became more significant over time. He et al. [68] found that the driving factors of urban expansion vary significantly under different urban morphologies, with economic and population factors playing different roles depending on the type of city morphology. Mahtta et al. [69] studied 287 cities around the world and found that across different geographic regions and levels of economic development, urban land expansion is driven more by population than economic growth. Many existing studies have analyzed the drivers of urban expansion, but the results vary somewhat due to the different methodologies, research levels, and scopes. For example, Liu et al. [34] explored the factors influencing ISA expansion in the Min Delta region and found that two natural climatic factors, rainfall and temperature, have the greatest influence on ISA expansion in the Min Delta, followed by transport conditions and location factors. The GDP, urbanization rate, and population density factors ranked low in influence because the units of these factors are too large for fine-grained modeling. It can be surmised that natural factors gradually overtake socio-economic factors in the importance of factors influencing urban expansion or ISA expansion as the sample scale of the study becomes smaller. These studies confirmed the validity of the conclusions in our study.

Summarizing the results, it can be concluded that ISA expansion is closely related to the economic development stage, while natural factors such as topography and precipitation limit the speed and maximum extent of expansion. For example, there are many hotspots in the Central Plains Region and Shandong Peninsula in China, while there are fewer hotspots in the regions south of the Yangtze River. This may be because (1) cities in southern China are more developed than those in the north, and (2) the terrain and precipitation in the south have limited the expansion speed of ISA.

There are still some limitations in the study. First, it is hard to explore the driving factors of ISA changes under different ISA expansion patterns, due to the difficulty in obtaining data. Second, at the city level, only a small number of representative cities among the top 20 in the world were selected as samples, and more cities can be explored in greater depth in the future. In addition, the specific relationship between each driving factor and ISA has yet to be quantified. The synergistic effect of multiple factors may also be an important factor affecting ISA changes. Moreover, scale effects are crucial in remote sensing research. The applicability of data varies across different pixel scales, which is a key issue in remote sensing science [70]. Since the study mainly focused on a global perspective, we processed the ISA data to a resolution of 1 km. This may result in a larger pixel scale for smaller cities like Hong Kong and Singapore. But overall, the study can reflect the trends and patterns of ISA changes. We also hope to have a more detailed consideration of spatial scale issues in future studies. Currently, the emergence of high-spatiotemporal-resolution RS data products provides support for research spanning from large to fine scales. Furthermore, with the continuous advancement of machine learning technologies, future efforts should focus on developing more interpretable deep learning architectures and improved ensemble learning methods to better capture complex nonlinear interactions between factors.

5. Conclusions

The conclusions of this study include the following: (1) ISA has grown by 0.94 million km2 from 2001 to 2020. The study found that the change rate of ISA reached its maximum in 2010, and the average rate from 2011 to 2020 is higher than that from 2001 to 2010. The ISA growth in Asia is larger than that in other regions. In terms of spatial distribution, ISA in regions such as Asia and Africa has expanded faster than the global average. In contrast, developed countries had lower expansion rates. The results of the spatial analysis showed that the hotspots of ISA change rate were concentrated in eastern Asia. In the early stage of the study period, hotspot areas were mainly distributed in Asia and eastern South America. In the later stage, hotspots became scattered and appeared in eastern Europe. (2) Based on calculated LEI scores, it was found that ISA expansion is dominated by the edge expansion type. According to the global income level of countries, upper-middle-income countries had the largest area of ISA expansion, followed by high-income countries. (3) Using the RF-SHAP method, at the continent level, the order of importance of driving factors is GDP > HDI > POP > ROD > MinT > MaxT > PRE > SLO > DEM; at the country level, the order of importance is GDP > POP > SLO > EMR > MinT > HDI > PRE > DEM > MaxT > ROD; and at the city level, the order of importance is DEM > SLO > PRE > GDP > POP > MaxT > MinT > ROD.

The study conducted a comprehensive temporal and spatial analysis of ISA changes, expansion patterns, and driving factors. By integrating natural and socio-economic factors, the study captured the key factors affecting ISA from multiple perspectives and spatial levels. In summary, the study provides a new perspective on the study of global urbanization. Changes in ISA are influenced by multiple factors and have different manifestations at different spatial scales. These reflect the trend of urban development. We hope that this study will provide policy references for urban development and contribute to city building and sustainable development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.X. and Y.G.; methodology, Y.X.; formal analysis, Y.X. and J.Q.; resources, W.Y., R.D., Z.W. and J.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.X.; writing—review and editing, Y.X., Y.G., T.Y. and C.Z.; visualization, Y.X. and Y.G.; supervision, Y.G. and S.G.; project administration, Y.G. and S.G.; funding acquisition, Y.G. and S.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Beijing Central Axis Protection Foundation, grant number 2023DYKT005.

Data Availability Statement

The data source has been declared in the article.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Beijing Central Axis Protection Foundation (2023DYKT005). The authors appreciate the valuable comments from the editor and reviewers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Full names and ISA change intensities of different countries.

Table A1.

Full names and ISA change intensities of different countries.

| Country Code | Country Name | Intensity | Country Code | Country Name | Intensity | Country Code | Country Name | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGO | Angola | 1.8515 | KOR | South Korea | 2.2589 | ISL | Iceland | 6.9444 |

| BDI | Burundi | 2.4865 | OMN | Oman | 16.8375 | ITA | Italy | 1.6639 |

| BEN | Benin | 3.8452 | UZB | Uzbekistan | 3.9634 | LIE | Liechtenstein | 2.1250 |

| BWA | Botswana | 1.9603 | KAZ | Kazakhstan | 3.4293 | LTU | Lithuania | 2.6608 |

| CAF | Central African Republic | 1.5588 | TJK | Tajikistan | 2.7135 | LUX | Luxembourg | 2.0959 |

| CIV | Ivory Coast | 0.5144 | MNG | Mongolia | 4.2568 | LVA | Latvia | 1.6767 |

| CMR | Cameroon | 0.5485 | VNM | Vietnam | 22.0455 | MKD | Republic of Macedonia | 1.6456 |

| COD | Democratic Republic of the Congo | 1.0321 | KHM | Cambodia | 11.5538 | MLT | Malta | 0.1279 |

| COG | Republic of the Congo | 1.1940 | ARE | United Arab Emirates | 4.1098 | POL | Poland | 2.5332 |

| DZA | Algeria | 0.6362 | GEO | Georgia | 1.7491 | PRT | Portugal | 1.1502 |

| EGY | Egypt | 1.0659 | AZE | Azerbaijan | 1.2626 | ROU | Romania | 5.0448 |

| ETH | Ethiopia | 7.3158 | LAO | Laos | 22.0455 | RUS | Russia | 2.3671 |

| GAB | Gabon | 0.8442 | KGZ | Kyrgyzstan | 1.8807 | SMR | San Marino | 2.0000 |

| GHA | Ghana | 1.0075 | ARM | Armenia | 6.1538 | SRB | Serbia | 5.2655 |

| GIN | Guinea | 1.8527 | IRQ | Iraq | 1.8210 | SVK | Slovakia | 1.8710 |

| KEN | Kenya | 4.6908 | IRN | Iran | 3.4639 | SVN | Slovenia | 3.0823 |

| LBR | Liberia | 0.4565 | QAT | Qatar | 0.1216 | SWE | Sweden | 2.1560 |

| LBY | Libya | 0.8704 | SAU | Saudi Arabia | 2.0781 | TUR | Turkey | 3.6302 |

| LSO | Lesotho | 0.9804 | THA | Thailand | 2.4294 | UKR | Ukraine | 2.3025 |

| MAR | Morocco | 0.5461 | KWT | Kuwait | 0.3426 | BLZ | Belize | 3.3000 |

| MDG | Madagascar | 9.2235 | BRN | Brunei | 2.5385 | CAN | Canada | 1.4718 |

| MLI | Mali | 2.7431 | MMR | Myanmar | 2.4937 | CRI | Costa Rica | 0.5267 |

| MOZ | Mozambique | 7.0951 | BGD | Bangladesh | 4.5137 | CUB | Cuba | 1.3382 |

| MRT | Mauritania | 0.2958 | AFG | Afghanistan | 4.2701 | DOM | Dominican Republic | 2.3112 |

| MWI | Malawi | 6.5455 | JOR | Jordan | 1.0912 | GTM | Guatemala | 0.4769 |

| NAM | Namibia | 4.3433 | NPL | Nepal | 1.2535 | HND | Honduras | 1.2341 |

| NER | Niger | 2.3514 | HKG | Hong Kong | 0.4554 | JAM | Jamaica | 3.5153 |

| NGA | Nigeria | 2.8313 | LKA | Sri Lanka | 26.4191 | LCA | Saint Lucia | 57.0000 |

| RWA | Rwanda | 4.1628 | SGP | Singapore | 0.3194 | MEX | Mexico | 0.8641 |

| SDN | Djibouti | 6.7500 | BHR | Bahrain | 0.3596 | NIC | Nicaragua | 0.9908 |

| SEN | Senegal | 1.0090 | ALB | Albania | 2.1437 | PAN | Panama | 2.4528 |

| SLE | Sierra Leone | 1.3393 | AUT | Austria | 1.7329 | SLV | El Salvador | 0.5818 |

| SWZ | Eswatini | 10.1515 | BEL | Belgium | 1.0122 | TTO | Trinidad and Tobago | 1.6404 |

| TCD | Chad | 2.0000 | BGR | Bulgaria | 2.6605 | USA | United States of America | 0.7298 |

| TGO | Togo | 3.7360 | BIH | Bosnia and Herzegovina | 5.6667 | AUS | Australia | 1.3787 |

| TUN | Tunisia | 0.8252 | BLR | Belarus | 2.1229 | PNG | Papua New Guinea | 16.0278 |

| TZA | Tanzania | 6.6667 | CHE | Switzerland | 1.2203 | ARG | Argentina | 1.1852 |

| UGA | Uganda | 1.4901 | CZE | Czech Republic | 1.6061 | BOL | Bolivia | 1.0106 |

| ZAF | South Africa | 1.3034 | DEU | Germany | 1.3002 | BRA | Brazil | 1.7414 |

| ZMB | Zambia | 1.8596 | DNK | Denmark | 0.7719 | CHL | Chile | 1.3109 |

| ZWE | Zimbabwe | 3.1638 | ESP | Spain | 0.9750 | COL | Colombia | 1.0929 |

| CYP | Cyprus | 1.3300 | EST | Estonia | 1.4362 | ECU | Ecuador | 1.8432 |

| IND | India | 1.2335 | FIN | Finland | 5.3944 | GUY | Guyana | 10.4000 |

| CHN | People’s Republic of China | 1.8881 | GRC | Greece | 0.8395 | PER | Peru | 1.8139 |

| ISR | Israel | 0.9084 | HRV | Croatia | 5.6667 | PRY | Paraguay | 3.8652 |

| PAK | Pakistan | 2.4158 | HUN | Hungary | 2.7515 | URY | Uruguay | 1.0315 |

| SYR | Syria | 2.9568 | IRL | Ireland | 4.7013 |

References

- Seto, K.C.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, R.; Fragkias, M. The New Geography of Contemporary Urbanization and the Environment. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2010, 35, 167–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; O’Neill, B.C. Mapping global urban land for the 21st century with data-driven simulations and Shared Socioeconomic Pathways. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Li, X.; Yang, J.; Ni, H.; Sang, X. How land use functions evolve in the process of rapid urbanization: Evidence from Jiangsu Province, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 380, 134877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wei, Y.D.; Ning, Y. Spatial and Temporal Evolution of Urban Systems in China during Rapid Urbanization. Sustainability 2016, 8, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-HABITAT. World Cities Report 2022: Envisaging the Future of Cities; UN-HABITAT: Nairobi, Kenia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Y.; Zhang, H.; Pan, W.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X. Urban expansion and its influencing factors in Natural Wetland Distribution Area in Fuzhou City, China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2012, 22, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, B.; Coops, N.C.; Lokman, K. Time series monitoring of impervious surfaces and runoff impacts in Metro Vancouver. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 760, 143873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creutzig, F.; Becker, S.; Berrill, P.; Bongs, C.; Bussler, A.; Cave, B.; Constantino, S.M.; Grant, M.; Heeren, N.; Heinen, E.; et al. Towards a public policy of cities and human settlements in the 21st century. NPJ Urban Sustain. 2024, 4, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersoy, A.; Bueren, E.V. Challenges of Urban Living Labs towards the Future of Local Innovation. Urban Plan. 2020, 5, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muoria, E.W.; Moturi, W.N.; Eshiamwata, G.W. Effects of Population Growth on Urban Extent and Supply of Water and Sanitation: Case of Nakuru Municipality, Kenya. Environ. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 8, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bren d’Amour, C.; Reitsma, F.; Baiocchi, G.; Barthel, S.; Güneralp, B.; Erb, K.; Haberl, H.; Creutzig, F.; Seto, K.C. Future urban land expansion and implications for global croplands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 114, 8939–8944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, T.; Fan, P.; Messina, J.P.; Mujahid, N.; Aldrian, E.; Chen, J. Impact of Urban built-up volume on Urban environment: A Case of Jakarta. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 105, 105346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, G.; He, B.-J.; Liu, Y.; Li, R. How does rapid urban construction land expansion affect the spatial inequalities of ecosystem health in China? Evidence from the country, economic regions and urban agglomerations. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 106, 107533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Yang, Z.; Galindo Torres, S.A.; Wang, Z.; Han, H.; Wada, Y.; Wanger, T.C.; Li, L. Statistical Distribution of Urban Area Reveals a Converging Trend of Global Urban Land Expansion. Earth’s Future 2025, 13, e2024EF005130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Li, X.; Dang, A.; Weng, Y.; Qiu, S. Adapting to heatwaves: Optimizing urban green spaces in Beijing to reduce heat health risks. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 130, 106600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, P.; Weng, Q. A time series analysis of urbanization induced land use and land cover change and its impact on land surface temperature with Landsat imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 175, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Song, C.; Gao, L.; Zhu, F.; Meng, X.; Wu, J. Impacts of landscape structure on surface urban heat islands: A case study of Shanghai, China. Remote Sens. Environ. Interdiscip. J. 2011, 115, 3249–3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, C.L.; Gibbons, C.J. Impervious surface coverage: The emergence of a key environmental indicator. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1996, 62, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schueler, T. The Importance of Imperviousness. Watershed Prot. Tech. 1994, 3, 100–101. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, J.; Yu, W.; Ren, J.; Xiao, X.; Xia, J.C. Relationship between urban spatial form and seasonal land surface temperature under different grid scales. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 89, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, A.; Resasco, J. The impact of impervious surface and neighborhood wealth on arthropod biodiversity and ecosystem services in community gardens. Urban Ecosyst. 2024, 27, 1863–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Bauer, M.E. Comparison of impervious surface area and normalized difference vegetation index as indicators of surface urban heat island effects in Landsat imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 2007, 106, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.; Guo, H.; Swan, I.; Gao, P.; Yao, Q.; Li, H. Evaluating trends, profits, and risks of global cities in recent urban expansion for advancing sustainable development. Habitat Int. 2023, 138, 102869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, E.; Benjamin, T.; Paul, S.; Kimberly, B.; Ara, H.; Cristina, M.; Budhendra, B.; Ramakrishna, N. Global Distribution and Density of Constructed Impervious Surfaces. Sensors 2007, 7, 1962–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, A.; Friedl, M.A.; Potere, D. Mapping global urban areas using MODIS 500-m data: New methods and datasets based on ‘urban ecoregions’. Remote Sens. Environ. 2010, 114, 1733–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Huang, Y.; Xu, X.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Ciais, P.; Lin, P.; Gong, K.; Ziegler, A.D.; Chen, A.; et al. High-spatiotemporal-resolution mapping of global urban change from 1985 to 2015. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 564–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Feng, Y.; Tong, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhai, S. Impacts of spatial scale on the delineation of spatiotemporal urban expansion. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 129, 107896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seto, K.C.; Güneralp, B.; Hutyra, L.R. Global forecasts of urban expansion to 2030 and direct impacts on biodiversity and carbon pools. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 16083–16088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zengxiang, Z.; Fang, L.; Xiaoli, Z.; Xiao, W.; Lifeng, S.; Jinyong, X.U.; Sisi, Y.U.; Qingke, W.; Lijun, Z.; Ling, Y.I. Urban Expansion in China Based on Remote Sensing Technology: A Review. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2018, 28, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Yan, Y.; Zhao, B.; Wang, H. Assessing the impact of adjacent urban morphology on street temperature: A multisource analysis using random forest and SHAP. Build. Environ. 2025, 267, 112326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Q.; Li, Z.; Zhu, J.; Yuan, C. Revealing multiscale and nonlinear effects of urban green spaces on heat islands in high-density cities: Insights from MSPA and machine learning. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 120, 106173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, D.; Tiefelsdorf, M. Multicollinearity and correlation among local regression coefficients in geographically weighted regression. J. Geogr. Syst. 2005, 7, 161–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Erion, G.; Chen, H.; DeGrave, A.; Prutkin, J.M.; Nair, B.; Katz, R.; Himmelfarb, J.; Bansal, N.; Lee, S.-I. From local explanations to global understanding with explainable AI for trees. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2020, 2, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Niu, Q. Spatiotemporal patterns, driving mechanism, and multi-scenario simulation of urban expansion in Min Delta Region, China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing System, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Y.; Jiang, W.; Ling, Z.; Liu, L.; Sun, S. Revealing the driving factors of urban wetland park cooling effects using Random Forest regression and SHAP algorithm. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 120, 106151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.; Yim, S.H.L.; Heo, Y. Interpreting complex relationships between urban and meteorological factors and street-level urban heat islands: Application of random forest and SHAP method. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 126, 106353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, P.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Bai, Y.; Zhou, Y. Annual maps of global artificial impervious area (GAIA) between 1985 and 2018. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 236, 111510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abatzoglou, J.T.; Dobrowski, S.Z.; Parks, S.A.; Hegewisch, K.C. TerraClimate, a high-resolution global dataset of monthly climate and climatic water balance from 1958–2015. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 170191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.X.; Meng, Q.Y.; Sun, Z.H.; Liu, S.F.; Zhang, L.L. Temporal and spatial correlation between impervious surface and surface runoff: A case study of the main urban area of Hangzhou city. J. Remote Sens. 2020, 24, 182–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getis, A.; Ord, J.K. The Analysis of Spatial Association by Use of Distance Statistics. Geogr. Anal. 2010, 24, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, B.; Bhardwaj, A.; Sam, L. Revealing the evolution of spatiotemporal patterns of urban expansion using mathematical modelling and emerging hotspot analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 364, 121477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Qin, Y.; Li, S.; Chen, M. Landscape Expansion Index and Its Applications to Quantitative Analysis of Urban Expansion. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2009, 64, 1430–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxford Economics. Global Cities Index. Available online: https://www.oxfordeconomics.com/global-cities-index/ (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafizadeh-Moghadam, H.; Minaei, M.; Pontius, R.G.; Asghari, A.; Dadashpoor, H. Integrating a Forward Feature Selection algorithm, Random Forest, and Cellular Automata to extrapolate urban growth in the Tehran-Karaj Region of Iran. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2021, 87, 101595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Wang, Y.; Liang, X.; Yao, Y.; Ma, T.; Guan, Q. Simulating urban expansion by incorporating an integrated gravitational field model into a demand-driven random forest-cellular automata model. Cities 2021, 109, 103044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonini, A.S.; Tanzola, J.; Asiain, L.; Ferracutti, G.R.; Castro, S.M.; Bjerg, E.A.; Ganuza, M.L. Machine Learning model interpretability using SHAP values: Application to Igneous Rock Classification task. Appl. Comput. Geosci. 2024, 23, 100178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Xiao, R.; Fei, X.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, Z.; Wan, Y.; Tan, W.; Jiang, X.; Cao, W.; Guo, Y. Analyzing “economy-society-environment” sustainability from the perspective of urban spatial structure: A case study of the Yangtze River delta urban agglomeration. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 96, 104691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstra, J.; Bengio, Y. Random search for hyper-parameter optimization. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2012, 13, 281–305. [Google Scholar]

- Song, R.; Liu, X.-M.; Wang, H.-B.; Lü, H.; Song, X.-Y. Hardness prediction of WC-Co cemented carbide based on machine learning model. Acta Phys. Sin. 2024, 73, 126201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; He, J.; Yue, C.; Ciais, P.; Zheng, C. Substantial terrestrial carbon emissions from global expansion of impervious surface area. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, G.; He, B.-J.; Sun, P.; Liu, Y.; Li, R.; Ouyang, X.; Luo, K.; Li, S. Evolutionary trends of urban expansion and its sustainable development: Evidence from 80 representative cities in the belt and road initiative region. Cities 2023, 138, 104353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Zhang, H.; van Vliet, J.; Ren, Q.; Wang, R.Y.; Du, S.; Liu, Z.; He, C. Patterns and Distributions of Urban Expansion in Global Watersheds. Earth’s Future 2021, 9, e2021EF002062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Feng, C.; Chen, H. International research and China’s exploration of urban shrinking. Urban Plan. Int. 2017, 32, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Y.; Yue, W.; Tang, C. Does regional cooperation constrain urban sprawl? Evidence from the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 235, 104742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Han, M.; Yung, E.H.K.; Chan, E.H.W.; Chen, Y. Spatial Heterogeneity Impacts of Urbanisation on Open Space Fragmentation in Hong Kong’s Built-Up Area. Land 2024, 13, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ye, R. Research on the Distribution Characteristics and Influencing Factors of FAR in Singapore. Urban Plan. Int. 2024, 39, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Nath, N.; Murayama, A.; Manabe, R. Transit-oriented development with urban sprawl? Four phases of urban growth and policy intervention in Tokyo. Land Use Policy 2022, 112, 105854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Jiao, L.; Guo, Y.; Xu, Z. Recognizing urban shrinkage and growth patterns from a global perspective. Appl. Geogr. 2024, 166, 103247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourtaherian, P.; Jaeger, J.A.G. How effective are greenbelts at mitigating urban sprawl? A comparative study of 60 European cities. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 227, 104532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Luo, F. Why do people move: An area-based exploration of intra-urban migration in Sydney and its relationship with built environment factors. Cities 2025, 165, 106176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos-Ocampo, J.P.; Gary, M.S. Urban growth strategy in Greater Sydney leads to unintended social and environmental challenges. Nat. Cities 2025, 2, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frolking, S.; Mahtta, R.; Milliman, T.; Esch, T.; Seto, K.C. Global urban structural growth shows a profound shift from spreading out to building up. Nat. Cities 2024, 1, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Yang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Yang, J.; Zheng, G.; Smith, J.; Niyogi, D. Urban development pattern’s influence on extreme rainfall occurrences. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castán Broto, V.; Bulkeley, H. A survey of urban climate change experiments in 100 cities. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, R.; Li, Z.; Wang, S. The varying driving forces of urban land expansion in China: Insights from a spatial-temporal analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 766, 142591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Zhou, Y. Urban spatial growth and driving mechanisms under different urban morphologies: An empirical analysis of 287 Chinese cities. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2024, 248, 105096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahtta, R.; Fragkias, M.; Güneralp, B.; Mahendra, A.; Reba, M.; Wentz, E.A.; Seto, K.C. Urban land expansion: The role of population and economic growth for 300+ cities. npj Urban Sustain. 2022, 2, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaowen, L.; Yiting, W. Prospects on future developments of quantitative remote sensing. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2013, 68, 1163–1169. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).