Abstract

In this work we present windlidar data for the research village Ny-Ålesund located on Svalbard in the European Arctic (N, E) from 2013 to 2021. The data have a resolution of 50 m and 10 min with an overlapping height of about 150 m. The maximum range depends on the meteorologic situation. Up to 1000 m altitude the data availability is better than . We found that the highest wind speeds occur in November and December, the lowest ones in June and July, up to 500 m altitude the wind is channelled strongly in ESE to NW direction parallel to the fjord axis and the synoptic conditions above 1000 m altitude already dominate. While the fraction of windy days () varies significantly from month to month, there is no overall trend of the wind visible in our data set. We define gusts and jets by the requirement of wind maxima above and below a wind maximum. In total, more than 24,000 of these events were identified (corresponding to of the time), of which 223 lasted for at least 100 min (“Long Jets”). All of these events are fairly equally distributed over the months relatively to the available data. Further, gusts and jets follow different distributions (in terms of altitude or depths) and occur more frequently for synoptic flow from roughly a southerly direction. Jets do not show a clear correlation between occurrence and synoptic flow. Gusts and jets are not related to cloud cover. We conclude that the atmosphere from 400 m to 1000 m above Ny-Ålesund is dominated by a turbulent wind shear zone, which connects the micrometeorology in the atmospheric boundary layer (ABL) with the synoptic flow.

1. Introduction

Monitoring and understanding the climate and its variability in the Arctic is a relevant topic. During the last century the warming in the Arctic was more than twice as fast as anywhere else on the globe. This self-intensifying phenomenon is called Arctic Amplification [1]. This warming of the Arctic is probably not an isolated regional effect; instead a warming Arctic may lead to a weaker polar vortex with more extreme weather events [2] and colder mid-latitude winters [3,4].

Ny-Ålesund, located on the west coast of Svalbard (N, E), is a multi-national super-site for environmental research in the European Arctic. The region from Svalbard to the Barents and Kara Sea currently faces an even more pronounced winter warming of more than +3K per decade [5], which has severe implications on the local permafrost [6] and glaciers [7]. The understanding of the atmospheric boundary layer (ABL) is very important, especially in the Arctic, because it is the interaction zone between the cryosphere, permafrost and the ocean and the atmosphere. Due to generally low solar irradiance, the ABL in polar regions is frequently stably stratified, shallow in depth and, hence, probably heterogeneous in nature influenced by surrounding mountains, fjords and wind fields. Hence, even small-scale changes in the wind pattern potentially alter ABL height and stability significantly on also short spacial and temporal scales. These complex interactions in the lowermost layer must be carefully parameterised in climate models, which is still an open topic. Recently Gryanik et al. [8] proposed an improved parameterisation for the stable polar ABL for climate models. However, a detailed understanding of the stable ABL is so far still missing. The orography around Ny-Ålesund varies a lot, glaciers are very close to the sea, the fjord is surrounded by mountains and permafrost covers the surface. One important quantity to describe possible turbulence in thermally-stable stratified conditions is the Bulk-Richardson number [9], which considers next to the profile of the potential temperature also wind speed and wind direction. Therefore, knowledge of the three-dimensional wind field with high temporal and vertical resolution is required to describe this atmospheric layer, for example for the distribution of short living pollutants [10].

There are already some studies on the wind field over Ny-Ålesund. However, the data basis mostly consists of wind measurements by sodar or tethered balloons in special campaigns for only a few weeks. These platforms pose some possible shortcomings: both cover only sporadic times and are, so far, limited in range. Beine et al. [11] and Argentini et al. [12] described the prevailing wind direction in the fjord, which is open from NW (north west) to ESE (east south east). Kilpeläinen et al. [13] used campaign-based data from tethered balloons from different fjords on Svalbard to test ABL parameterisations in WRF models (Weather Research and Forecasting Model). Finally, Esau and Repina [14] used long-term radiosonde data and high-resolution modelling of the surrounding Kongsfjord to describe the channelling of the wind due to orography in the lowermost 500 m of altitude. Furthermore, they all came to the conclusion that katabatic outflow from glaciers in the east of Ny-Ålesund are not the the main reason for the prevailing ESE or NW surface wind direction, because these winds cannot produce wind velocities . An available long-term data set that describes the wind well into the stratosphere, is recorded by radiosondes launched from Ny-Ålesund on a daily basis [15]. The meteorologic data from radiosondes have already been used to estimate an ABL altitude over the site by Schulz [16]. However, as normally only one radiosonde per day is available, short-living and micrometeorologic phenomena, which impact the ABL height and stability, cannot be resolved [17]. Further, to simulate cloud fields [18] or to understand the vertical aerosol distribution [19] a continuous monitoring of the wind field in the resolution of minutes is required.

In this work we describe and present windlidar data of a “Windcube 200” instrument (originally from Leosphere, now Vaisala) from 2013 to 2021 operated in Ny-Ålesund. The instrument and its data are described in Section 2. We present results on wind speed and direction in Section 3 and discuss occurrence and physical properties of arctic long jets (LJ) in Section 4.

2. Instrument Description, Data Availability and Measurement Site

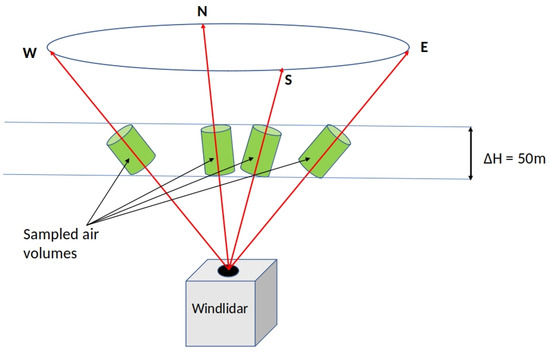

The windlidar “Windcube 200” by Leosphere was installed at the German-French research base AWIPEV in Ny-Ålesund in 2012 and is measuring continuously since 2013. As a representative of a lidar system, the windlidar emits a laser beam at a wavelength of 1.54 m. This laser light is backscattered by aerosols, which are considered to be tracers for the wind field, and captured by the instrument. Due to the Doppler Effect the returning light is slightly red- or blue-shifted. For the entire reconstruction of the wind vector the laser beam is also tilted by off the vertical axis and measures in all of the four cardinal directions. It has to be considered that only one three-dimensional wind vector is calculated from all four directions. With the off-axis measurement different parts of the atmosphere are scanned, in which the physical properties can already be slightly different as displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Measurement principle of the windlidar. Obviously not exact the same air mass is measured, when the instrument performs a scan.

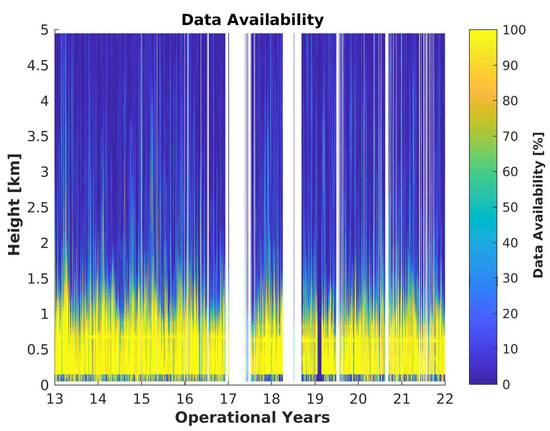

The instrument has a resolution of the wind parameters of 0.5 , and a height resolution of 50 m up to a maximal range of 5 km. However, measurement data show that this range value is very optimistic and only met in a few cases, because of the low concentration of aerosols in the Arctic. Therefore, we used a 10 min average of the data to reduce significantly the measured noise. The overlapping height is approximately 150 m. In the entire measurement period some months of data are missing due to technical issues. The availability of the over 10 min averaged data for every height step for the entire measurement season is shown in Figure 2. A general good coverage is achieved up to a height of 1 km ( availability). The 500 m level has already a coverage of . For the 800 m level the availability already drops to , for the 1000 m level it only reaches and at 1200 m . It can also be observed that, with increasing age of the instrument, more and more gaps in the data occur. Clouds do modify the useful range: low-level clouds or fog attenuate the laser beam and greatly reduce the achievable range. On the other hand, in a few cases high-level clouds will produce backscatter values high enough to obtain a detectable signal even if the subtle aerosol concentration below the cloud was not sufficient to calculate a wind vector. Hence a windlidar profile may contain valid values from the end of the overlap range up to the end of the visible aerosol as well as a few values from the cloud bottom, and not-a-number values elsewhere. At about 700 m altitude the data availability reaches a relative maximum over the years (Figure 2). This may be caused by a combination of a technical and a meteorologic phenomenon: at this altitude the overlap of the system is complete, yielding the best carrier-to-noise ratio (CNR). According to Burgemeister [20] the CNR of the windlidar is good in the range of 200 m to 1000 m. Secondly, Maturilli and Ebell [21] reported frequent cloud cover at this altitude and therefore a more frequent backscatter signal is expected. In the time from 2013 to 2021 on 2887 days measurements were performed, giving in total 397,041 individual wind profiles. A more detailed analysis of the real performance of the windlidar has been done by Burgemeister [20]. It was found by comparison with Vaisala in situ wind sensors attached at different altitudes on a tethered balloon in Ny-Ålesund that the windlidar measures wind speed reliably down to and shows no offset for wind direction.

Figure 2.

Availability of windlidar data in percent for the entire measurement time. The shown data are already averaged over 10 min.

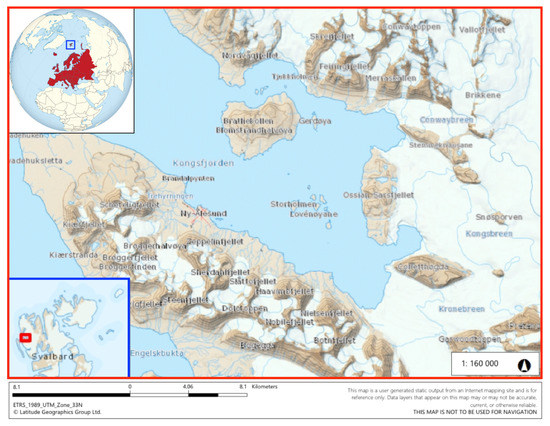

The observation site in Ny-Ålesund is located along the shore of Kongsfjord, which is orientated in a ESE to NW direction on the west coast of Svalbard (Figure 3). In addition to the fjord it is also surrounded by glaciers and mountains of about 700 m height. The fjord ends in the easterly direction at a large ice field. It is expected that the orography with channelling and shadowing effects is crucial on the pattern of the wind fields, at least at altitudes below 500 m [11,16,20].

Figure 3.

Map of the vicinity of Ny-Ålesund, Kongsfjord and its location in Europe. Sources: https://geokart.npolar.no/Html5Viewer/index.html?viewer=Svalbardkartet (accessed on 1 August 2022), courtesy of Norsk Polarinstitutt and https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Datei:Europe_on_the_globe_(red).svg (accessed on 1 August 2022).

3. Results on Wind Speed and Wind Direction

In the following section we will divide the atmosphere into three parts: the lowermost is highly influenced by the orography of the fjord and represented by an upper threshold of 500 m, the second layer is at 800 m being already slightly out of the shadow of the mountains, but still influenced by their presence and a third layer above the influence of the orography, represented by the altitude of 1000 m. This altitude does also match with a layer of humidity inversions and temperature inversions based on radiosonde data [5,15,22]. However, the lowermost layer is probably not the ABL, which is known to be much more shallow in polar night [16,23,24]. The consideration of a higher layer, for instance at 1.5 km height presented by Esau and Repina [14], was not able to be investigated with the available windlidar data due to the sparse data coverage (Figure 2).

3.1. Trends on the Monthly Wind Speed

An overview over the monthly median wind speeds are shown in Table 1 for all of the three selected heights. Wind roses for exactly these altitudes will be discussed in detail later on.

Table 1.

Median wind speeds for every month for the selected altitudes (2013–2021).

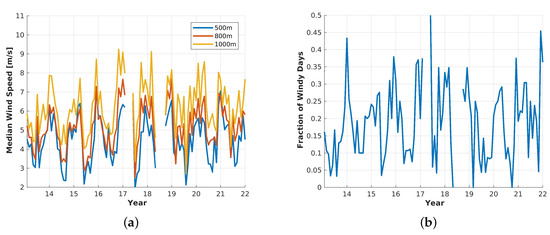

The median wind speeds are, at all heights, smaller in summer than in winter and increase in general with increasing altitude (Figure 4). The month with the highest wind speeds is December, and the one with the lowest on average is July. Furthermore, with increasing altitude the difference between December and July decreases from at 500 m height to at the 1000 m level. The directional dependency and the relative frequency of windy events are colour-coded in Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7. In the direct comparison of the three selected height levels in Table 1 with Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7 it can be seen that high wind speeds () are more often observed at the 500 m level than at higher altitudes and only occur for winds from ESE. On the other hand, the higher median wind speed is found due to generally higher wind speeds. The monthly median velocities are shown in Figure 4a for the three already-introduced heights.

Figure 4.

Monthly averaged wind speeds at three different altitudes, 500 m, 800 m and 1000 m, for the entire measurement period and the fraction of windy days () at least one of the three heights per month. (a) Monthly median wind speed, (b) Ratio of windy days () to measurement days per month.

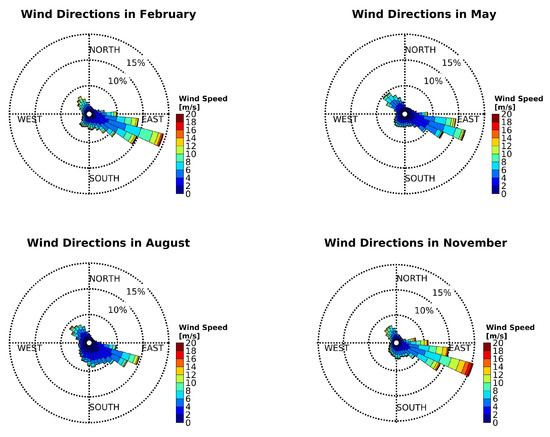

Figure 5.

Wind roses at 500 m altitude in February (top, left), May (top, right), August (bottom, left) and November (bottom, right) of the years 2013–2021.

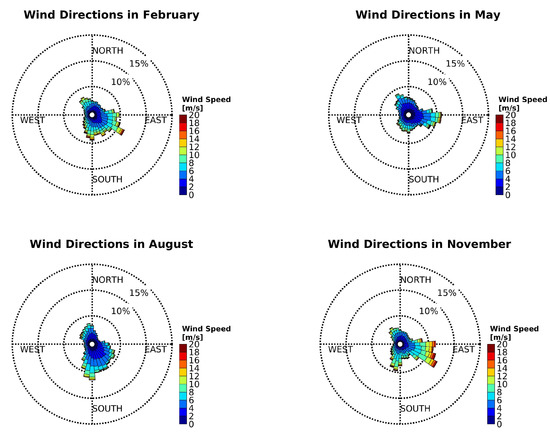

Figure 6.

Wind roses at 800 m altitude in February (top, left), May (top, right), August (bottom, left) and November (bottom, right) of the years 2013–2021.

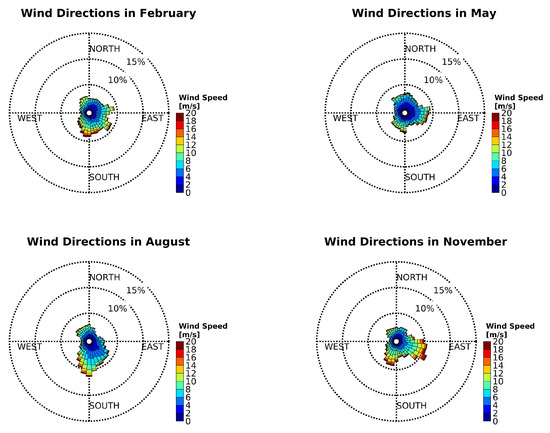

Figure 7.

Wind roses at 1000 m altitude in February (top, left), May (top, right), August (bottom, left) and November (bottom, right) of the years 2013–2021.

Except for the obvious annual cycle, there is no overall trend in the analysed period. Figure 4a agrees also with the results found in Table 1, where the wind speeds are generally lower in summer than in winter. The fraction in Figure 4b reveals whether in general more windy days () were observed by the windlidar from 2013–2021. It is not distinguished between the three heights, 500 m, 800 m and 1000 m and, if in just one of these, the wind speed reached the threshold, it was already considered as such an event. In this figure the previous result of more windy days in winter is confirmed, but also here no trend is observed in this data set.

3.2. Wind Patterns in Selected Altitudes

The wind roses in the Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7 show the wind patterns for the representative months of each season during the years of 2013–2021. The dashed circles represent the relative frequency of the wind direction at a , and level. As already Jocher et al. [25] observed in the data of the nearby eddy covariance station, three major wind directions in the ABL of Kongsfjord are found: the most dominant one in every season and over all these years is ESE (east south east), parallel to the orientation of the fjord and the interior of Svalbard with huge ice fields. The second one is pointing to the entrance of Kongsfjord in the north-westerly (NW) direction. The last one is pointing towards the south-west (SW) with a peak at about 220–230. Jocher et al. [25] connected this flow with katabatic outflows of the glacier Brøggerbreen and the comparable low mountains of the ridge on Brøggerhalvøya. The four months February, May, August and November were chosen in Figure 5 as representatives of each season because they are special in their own way. February is one of the coldest months of the year because it represents the end of the polar night. The sun will return at the beginning of March with some energy input. Already in May the period of snow melting is in progress [26,27]. It may already happen that tundra is free of snow and ice at that time. Furthermore, the polar day started about a month ago. August is characterised as a very warm month with snow-free tundra. November, on the other hand, has usually little or no snow cover. Polar night already started and the days become continuously darker and cooler.

The patterns of the years 2013–2021 of February and November look similar, while May and August show a comparable pattern. The two months within the polar night have the predominant direction of ESE; wind directions of NW and SW occur, but only with an ancillary frequency. The direction matches with the orientation of the fjord. At a height of 500 m a difference between polar day and night can be observed in regard to the wind speed. Wind speeds of are barely observed in the bright months (May and August), while these velocities are more often observed in polar night. Wind speeds of are also represented.

The situation looks completely different for the wind roses of the 800 m level, which marks the transition from orographic to synoptic influences. This height also corresponds with the altitude of the sudden change in the wind pattern of Figure 8. Figure 6 shows the same months and uses the same measurement period as Figure 5, but is now looking at the altitude of 800 m. It can also be observed that the data coverage of this altitude is worse than at 500 m (see also Figure 2). Furthermore, the distribution of the wind speed becomes broader, as the channelling of the orography decreases at this altitude. Therefore, the mark of is barely reached.

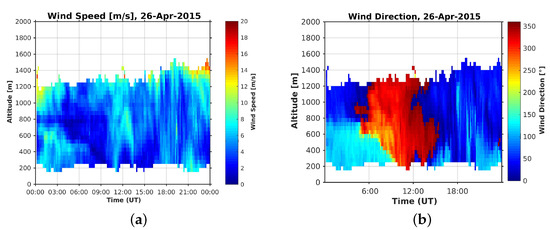

Figure 8.

Example of a sharp change in wind speed and direction. (a) Wind speed of 26 April 2015, (b) Wind direction of 26 April 2015.

In contrast to the previous wind roses, the ones at an altitude of 800 m (Figure 6) can be grouped by February and August as well as May and November. February and August show a predominant direction to the southwest (SW) and northwest (NW). This observation is more obvious in August than in February. May and November prefer directions to the ESE, SSW (south south west) and NW. Since the surrounding mountains have only a height of about 700 m, katabatic outflows of glaciers cannot occur anymore. In addition to the influence of the fjord and the mountains with their channelling effect on the wind, which is observed at the 500 m level, the free troposphere slowly becomes more important. The wind roses become more and more homogeneous compared to Figure 5. However, the pattern at this level is still related to the wind fields below.

At last Figure 7 presents the wind roses of the free troposphere at 1000 m altitude. Again all the four representatives of the different seasons have their own, unique pattern but become more similar. While February has small peaks in ENE, SE, NWN and S, the situation looks already different in May. In spring SW and the directions of E and N are preferred. August on the other hand has again its unique shape, in which wind is avoiding northeasterly and westerly directions. It only comes from the north and south. With the beginning of the polar night the pattern again changes, north and south lose their importance and the directions of ESE, SW and N become more important. This altitude can be assumed already as comparable with the synoptic flow, since the difference of wind direction between the 1000 m level and the 1200 m level is, on average for the entire measurement time, just . This result was also found by Burgemeister [20].

The different altitude levels show all their unique patterns for every of the four seasons. In general the distribution becomes more homogeneous and the orography loses its importance for the prioritised wind direction. A big difference is observed between the 500 m level and the one at 800 m. Rising from there to the 1000 m level does not change the pattern completely. It just becomes more homogeneous; the maximum of the frequency, with which the wind direction appears, becomes less dominant. Air from more directions are advected to Ny-Ålesund and the relative frequency of the predominant direction becomes drastically smaller. According to radiosonde profiles, the southerly branch of the wind roses of the 500 m level starts at about this height. The mountains in the south have about this height and the shielding of the mountains in this directions becomes weaker [16]. Moreover, inspection of Figure 6 and Figure 7 reveals that August deviates most from the other months. The impact of the fjord channelling is weakest (at 800 m altitude) and at 1000 m altitude in August most southern and least eastern flow was found. Nevertheless, the directions of ESE, NW and SW can still be found as maxima, first or second, in most of the months and altitudes. The observed patterns of the three different chosen heights in this study agree with the previous publications and the comparison between windlidar data and ECMWF re-analysis data of Burgemeister [20]. In that study only the two heights of 250 m and 1000 m were analysed. Nevertheless the Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7 can be easily compared with them and show a similar result. Furthermore, Schulz [16] found similar wind patterns when looking at the daily 11 UTC launches of radiosondes at AWIPEV in Ny-Ålesund.

3.3. Wind Shear Zones

In the simulation of Esau and Repina [14] typical wind shear zones were identified at 925 hPa (equivalent to about 700 m altitude) and 850 hPa (equivalent to about 1.5 km altitude). Additionally, in summer the median thickness of channelled wind becomes noticeably thinner than in winter times. In the measurement data of the windlidar the most probable altitude, in which the wind changes or relatively to the lowermost measurement point has been calculated. In general these heights appear at a median height of 600 m for and 650 m for . In summer (JAS) this altitude drops to 500 m and 600 m, respectively, while in winter (JFM) it rises to 600 m () and 650 m (). The yearly most probable height for the change of the wind direction is located. This height of wind shear also explains the significant change of the wind roses presented in this paper between the 500 m level (Figure 5) and the 800 m level (Figure 6), which agrees with the simulated wind fields of Esau and Repina [14].

An example of this sharp change of wind speed and direction is observed in an altitude range of 750 m is given in Figure 8 from midnight until 3 UTC of April 26th, 2015. Below and above this calm the wind speed is . Since the wind direction differs significantly no air masses are exchanged between the lower layer m height and the one above at m. This observation of rapid changing wind direction cannot be observed sufficiently enough by daily radiosonde launches.

3.4. Surface Wind and Synoptic Pattern

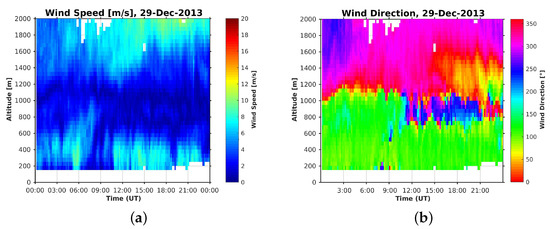

On 29 December 2013 a constant band of wind with about was observed in the lowermost hundreds of meters with a wind direction of about SE (Figure 9). This wind direction is expected according to Figure 5 and results by channelling effects of the fjord.

Figure 9.

Example for different rotations to connect a constant surface wind with the synoptic flow. (a) Wind speed of 29 December 2013. (b) Wind direction of 29 December 2013.

When comparing the wind speed with the direction of this example day, it can be seen that, throughout the entire day, the wind direction of the wind did not change significantly for the surface wind (SE) as well as for the wind in 2000 m, which can be already associated with the northwesterly wind of the synoptic flow [20]. In the first part of the day until about 10 UTC, the wind changes suddenly at a height of about 1100 m from SE to NW and has a small band at , while the wind speed in this transition phase decreases. In contrast to this, the second half of the day shows an about 300 m thick band of wind from SW, until the wind adjusts to the synoptic flow further up. As this example shows, knowing the surface wind direction and the synoptic flow is not sufficient to predict the rotation of the wind field in between.

4. Study on Wind Phenomena: Gusts, Intermediate Jets (IJ) and Long Jets (LJ)

The wind profiles also show a rare wind phenomenon over Ny-Ålesund: jets. Wexler [28] described low-level jets (LLJ) as anomalously strong winds in the lowest 2 km of the troposphere with a horizontal extent up to a few hundred kilometres and may reach wind speeds of twice as fast as several hundred meters below or above for the mid latitudes. These low-level jets occur when vertical, turbulent mixing of the lower tropospheric air takes place or an inertial oscillation starts which relies on the retardation to subgeostrophic speeds of the mixing air. When the layer closest to the surface undergoes radiative cooling, it becomes statically stable and decouples from the layer of air above. This layer then becomes nearly frictionless and turbulence free. It accelerates due to the synoptic pressure gradient. With Coriolis force acting on this accelerating and frictionless air stream an inertial oscillation with supergeostrophic speeds is reached after already several hours [29]. Other possibilities of creating a low-level jet are, amongst others, are by baroclinity [30] or katabatic winds [31]. Usually, low-level jets are found close to the top of a temperature inversion, within a temperature inversion layer or near the base of an elevated inversion [29,32] or by ice breeze in mesoscale circulations [33]. We found jets in the windlidar data, which look like low-level jets. In the following we name our jets Long Jets (LJ), since we cannot relate the observed jets to a specific physical mechanism.

There is not a uniform definition of low-level jets in meteorology: some authors require a minimum wind speed of [34] or just a significant maximum of wind speed below 1000 m above the ground [35]. Authors such as [36] classify low-level jets into three categories according to their wind speeds of at least , and . Others relate LLJ to the geostrophic wind [37]. Another definition of these jets are given by a decrease of wind speed with height [30]. The above-mentioned authors also do not agree with each other on the vertical size of low-level jets. While [35] requests additionally a certain temperature profile to a height limit of 1000 m, others such as [34] and Stull [38] set the limit to 1500 m or even to 2500 m [36]. On the other hand there are no restraints regarding the duration of low-level jets because usually radiosondes are used for observation, which can only provide an in situ measurement at one given point of time.

In this paper a stricter definition of [38] of LLJ for the observed long jets is used, even though it has weak criteria: the long jet has to be in the lowermost 2000 m of the troposphere, has a relative wind speed maximum of at least compared to the surrounding atmosphere and last for at least 100 min. Additional to this temporal constraint, an event is considered as continued if two as “event”-marked data points have a maximum of one unmarked point between them, which corresponds to a shift of 50 m in height or 10 min in time. A jet must also have at least of the data points marked as “event” to be considered as connected. Otherwise it is considered as a collection of shorter events or single gusts. A clear minimum has to be observed. The ground, at which the wind speed is assumed to be due to friction, was never the lowermost point in this study, because it cannot be distinguished if the wind maximum at very low altitudes was a real event or an ordinary wind. Events which are just recorded for 10 min are called “gusts” in the following. Events with a longer span than gusts, but not as long as long jets, are defined as “Intermediate Jets” (IJ). The difference in the wind speed between the event and the associated minimum speed is defined as its strength, the spacial/vertical extent is its depth.

4.1. Occurrence of Wind Events

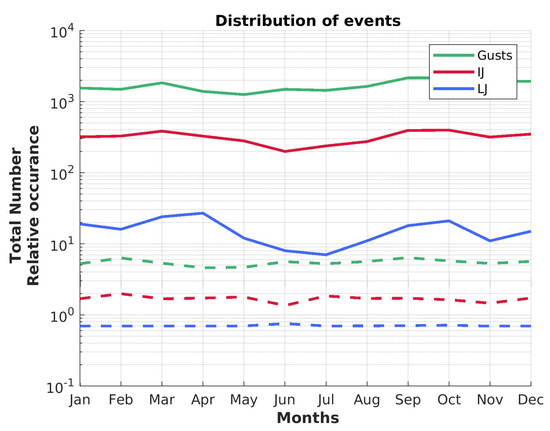

Wind events are recorded by the windlidar in its measurement time in total 24,301 times (about of the total wind profiles contain a wind event). Only 223 of these were classified as long jets (Table 2 and Figure 10). The maximum wind speeds of the events vary between for LJ and for gusts, but also in duration of several minutes up to 310 min. Figure 10 presents all observed events, long jets, intermediate jets and gusts, over Ny-Ålesund in the discussed time frame of about one decade sorted by month. The numbers which were used are given in Table 2. Within the entire measurement period 20,273 gusts, 3805 intermediate jets and 223 long jets were in total observed over Ny-Ålesund (Table 2 and Figure 10). Over the nine presented continuous measurement years gusts were found in about of all wind profiles, intermediate jets in and long jets in of all cases. It can clearly be seen with the relative numbers that these events, especially long jets, are not very common in Ny-Ålesund but still will be discussed in detail. A probable rising mechanism is sought later on.

Table 2.

Absolute number of LJ according to their season for the years 2013–2021. These numbers are plotted in Figure 10. The relative occurrence (rel. occ.) compared to the total amount of individual wind profiles of the three types is also given.

Figure 10.

Number of events for gusts, intermediate and long jets summed up over all years for every month (solid line). The dashed lines represent the relative occurrence of these three events in respect to the absolute number of measurement points per month.

The absolute numbers (solid lines) of gusts, intermediate jets and long jets are subject to clear changes within the course of the year with a minimum in the months May to July and a maximum in the coldest months around March to April and September. However, when looking at the fraction of events depending on the total number of available measurement points per month, the annual course is not present anymore. This observation can only be explained by a general lower amount of measurement points in summer months and higher data coverage in winter.

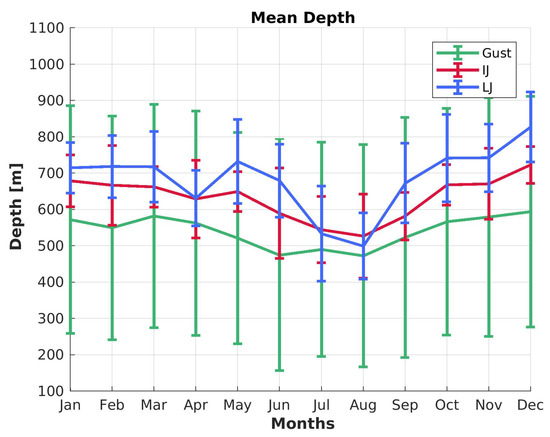

4.2. Depth of Wind Events

In the following the depth of an event is defined as the altitude difference between both of the wind minima around the maximum. Figure 11 shows the mean depth and the standard deviation of every months for each category of event. Surprisingly, all three categories follow the same seasonal trend with a larger depth in December and a smaller vertical extent in June to August. While gusts have a slightly smaller vertical extent, the standard deviation is largest compared to the two longer events. This might indicate the importance of the orography on the formation on these features. On average over all months and years, the depth of the windy layers is 577 m. However, all three types of events have the tendency to be geometrically thinner in the summer months June to August, while increasing their extension towards the end of the year. It is conspicuous that gusts have a slightly smaller depth than the longer events, and are also more homogeneously distributed in their mean vertical extent over the year. IJ have a clear annual cycle with a low spreading of their depths. Contrary to this, LJ show the biggest month-to-month variation but also the biggest difference between the thickest and thinnest mean vertical extent with 827 m (December) and 499 m (August), respectively.

Figure 11.

The mean depths of gusts, IJ and LJ are displayed with their standard deviations for every month.

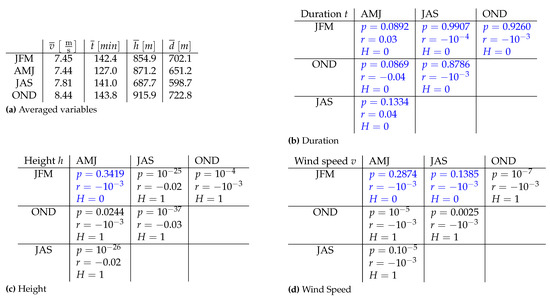

To test the independence of the three groups, gust, IJ and LJ, a two sided Mann–Whitney U test was performed with a significance level of for all combination possibilities. Moreover, the Pearson correlation coefficient , with z being the z value and N the number of pairs, was calculated. The z value indicates how many standard deviations a statistical value deviates from its mean. A Pearson correlation coefficient of or indicates a (strong) correlation, indicates no correlation.

A more detailed analysis of the statistical dependence by the Mann–Whitney U test can be done by looking at the different observed variables of only long jets, such as duration, depth, wind speed or height, and comparing observed variables of LJs of different seasons with each other (Figure 12). Averages per season are given in Figure 12a for the averaged properties of the long jets, such as wind speed , duration , height and depth . Intermediate jets and gusts are not considered in this part.

Figure 12.

Seasonal averages of the variables (a) as well as seasonal correlation of duration (b), height (c) and wind speed (d). p is the significance level of the Mann–Whitney U test, with the null hypothesis cannot be rejected (values are marked in blue), and the null hypothesis can be rejected. The Pearson correlation coefficient, r, is also given for all of the variables.

The mean wind speed of long jets is generally lower in the first half of the year and increases later on to up to (Figure 12a). The duration is very homogeneous at around 142 min for the entire year except for spring (AMJ) with 127.0 min. The depth on the other hand is very variable over the seasons and changes from 598.7 m (JAS, summer) to 722.8 m (OND, autumn). It can be seen that the null hypothesis of the Mann–Whitney U test can be rejected for only some combinations and the variables are statistically independent (, marked blue in Figure 12) considering each season and physical property of the jet individually. Combinations for which the null hypothesis cannot be rejected are marked blue in the Figure 12a–c. The situation is different when comparing an observed variable during the course of a year.

The Mann–Whitney U test reveals that the duration t has a similar behaviour over the course of the year. The distributions of every season are similar to each other, because the null hypothesis cannot be rejected (Figure 12b). On the other hand the height h and the core wind speed of the long jet v are in general not similar over the course of a year. Nevertheless, all the presented properties of the observed LJ are, according to the Pearson correlation coefficient, not statistically dependent with , since the maximum correlation of all properties shown in Figure 12 reaches just . Even though the null hypothesis cannot rejected for the cases of winter-spring for height as well as for the combinations of winter with spring or summer, the correlation coefficient is still at , so that the result is not statistically significant.

4.3. Wind Speed, Duration and Height Distribution

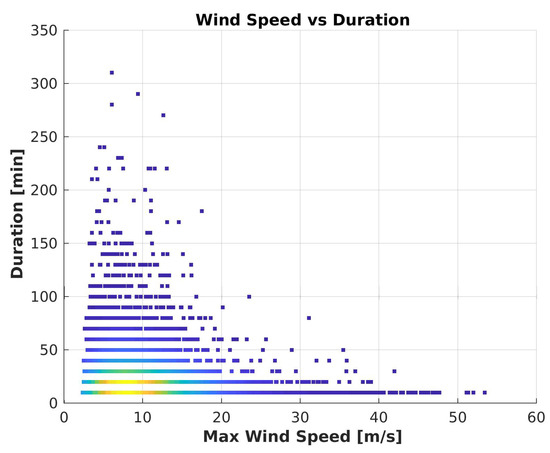

Figure 13 shows the relation between maximum wind speed and the duration of all detected wind events and also, colour-coded, their relative frequency. Blue represents single cases, while yellow shows highest probability of occurrence.

Figure 13.

Dependency between maximum wind speed and the duration of the events. The colour indicates the relative number of events (blue: least, yellow: max, in arbitrary units). All gusts are pictured here at min, LJ start at min. In between all intermediate jets are plotted.

It can be seen that, as expected from Figure 11, gusts at min have the broadest wind speed range from up to for single cases. Most of the events are recorded with a maximum speed of about . Intermediate jets only have a record high wind speed of at a duration of 30 min, the least jet wind speed was measured with . The trend of a drastic decrease of maximum wind speed with increasing duration length continues to about 100 min, which is also the threshold for the category of long jets. In the regime of the long jets the wind speed increases slightly with increasing duration and gather in about the same range, in which the highest frequency of gusts occur: .

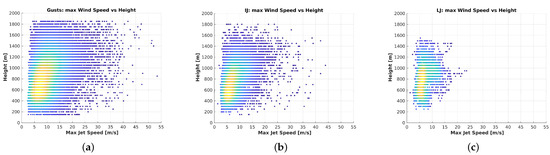

Figure 14 reveals the distribution of wind events dependent on the appearing height for all three cases. They do not contribute to the relative frequency shown here in the colours from blue (low) over green to yellow (high).

Figure 14.

Dependence of the maximum wind speed in respect to the height of the different wind events. The colours blue (low) to yellow (high) in arbitrary units indicate the relative frequency of the corresponding events for 2013–2021. (a) Gusts, (b) Intermediate Jets, (c) Long Jets.

The Mann–Whitney U test is again used to estimate if the populations of the three different wind events are statistically dependent as described already in Section 4.2. The significance level of the combination LJ and IJ is with Pearson correlation coefficient , the combination gusts and LJ gives and a correlation coefficient of and for gusts with IJ a significance level of corresponding to . For all of these three combinations the null hypothesis of the Mann–Whitney U test must be rejected because the three data sets do not share the same parent population. This result corresponds also to the result of the Pearson correlation coefficient, since in all cases . Therefore, the annual cycle of the vertical extent really differs for gusts, IJ and LJ and the null hypothesis can be rejected.

Two maxima can be found in the relative frequency of gusts (Figure 14a). One peaks around 550 m altitude corresponding to a wind speed of , the other one at 750 m corresponding to of a similar relative occurrence. The broadest wind speed envelope at a certain height level increases up to about 1200 m. Contrary to the gusts, one maximum of relative frequency can be found for the intermediate jets (Figure 14b), where the maximum is at 550 m corresponding to . Still, a comparable high number of intermediate jets are also found in heights up to 900 m with wind speeds up to . The shape of the velocity-height distribution looks similar to the envelope of the one of the gusts with a maximum at about an altitude of 1200 m. The probability of a long jet formation also has two maxima (Figure 14c), one at 800 m altitude, the other one at 950 m height with about to . The envelope of the distribution of long jets is symmetrical with the maximum at 900 m. An eye catching phenomenon of the height-resolved distribution of long jets is that they show the smallest deviation with the lowest identified case at 250 m and the highest one at 1550 m. Contrary to this, intermediate jets and gusts have a broader distribution and reach beyond the limits of 150 m and 1850 m, respectively. In both cases of Figure 14 no correlation can be found between the long jets and the other two events. This correlates also with the result found in Section 4.3 and the statistical analysis with a Mann–Whitney U test of the three sample groups.

4.4. Wind Direction of Jets

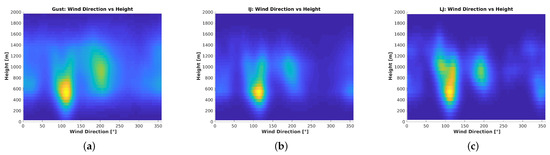

The wind roses in Section 3 show a clear pattern of the wind direction in Kongsfjord. In Figure 15 the distribution of direction and height for the three wind events (gusts, IJ, LJ) is presented as an overview of the relative distribution: high (low) occurrences are marked with yellow (blue). As already seen in Section 4.3 all wind events are statistically independent from each other with a clear preferred wind speed and core height (Figure 14).

Figure 15.

Distribution of wind direction and height of the three wind events. The colour blue (low) to yellow (high) in arbitrary units indicate the relative frequency of the corresponding events for 2013–2021. (a) Gusts, (b) Intermediate Jets, (c) Long Jets.

It can be seen from Figure 15 that there are preferred wind directions in which all types of wind events tend to appear. The most dominant direction is, as expected from Figure 5, around (ESE). The second most dominant is around (SW) and around also long jets accumulate. The preferred direction of ESE and the corresponding most likely appearance of wind events fills a very small gap in altitude and direction, which is parallel to the fjord axis and just beneath the mountain tops around it and has also the lowest altitude. They appear in 600 m to 1200 m and have for all three cases a sharp border towards the ground. The second one, of the SW, appears at the height of the nearby mountains and are probably caused by the orography. Last, but not least, some wind events occur from the north with a broad homogeneous altitude distribution from 400 m to 1600 m. The appearing height for jets and gusts in northerly or southeasterly directions is probably so low because the open water of the fjord is a very smooth surface compared to the rougher land, and is more undisturbed. Due to friction the appearing wind events occur at higher altitudes from the SW. These three most dominant wind directions agree perfectly with the previously presented wind roses of Section 3.2. While gusts can occur in any direction and altitude, their occurrence probability clearly peaks around to and 350 m to 1000 m altitude as well as around to and 600 m to 1200 m altitude (Figure 15a). Intermediate jets show the most concentrated probability distribution (between and and 350 m to 750 m altitude, Figure 15b).

Contrary to the results of the numerical study of Kilpeläinen et al. [13] the strongest long jets occur when the wind comes from the ESE or SW. Jets from the north are usually the slowest ones. No trend over the study time was found for the LJs.

4.5. Jets and Cloud Cover

Even if Esau and Repina [14] already stated that katabatic outflow cannot exceed wind speeds around Ny-Ålesund we analysed the hypothesis whether the found wind structures (gusts, IJ, LJ) are at least partially influenced or initiated by katabatic outflow of the surrounding glaciers or the ice field Holtedahlfonna (in the east of Ny-Ålesund) and amplified by channelling of Kongsfjord. These outflows develop under clear sky conditions when the near-surface air cools via IR radiation loss; the air becomes more dense and slides down the slope of the glaciers in the east (Holtedahlfonna) of our site. Hence, if this hypothesis were true, gusts, IJ and LJ must be noticeably more frequent under clear sky conditions. The ceilometer CL-51 by Vaisala at the BSRN field in Ny-Ålesund continuously measures cloud cover and cloud base height. Further information about the instrument and the data availability can be found in Maturilli and Ebell [21]. All three wind events are analysed regarding the cloudiness of their existing to reveal their origin.

Comparing the classified wind events and the ceilometer reveals that there is only clear sky in about (gusts), (IJ) and (LJ) of the cases. Usually for the cloudy situations the cloud base height is at 1547 m (gusts), 1664 m (IJ) and 1529 m (LJ). Comparing these results with the average cloud cover over our study period a general clear sky of and the cloud base height of 1430 m were found. Therefore, the existence of gusts and jets does not depend on cloudiness. Hence we can confirm that a katabatic origin of these wind phenomena is unlikely.

4.6. Jets and the Synoptic Flow

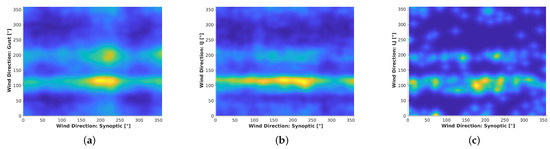

In this subsection the hypothesis is tested whether the occurrence of gusts and jets depends on orographically induced wind shear. The approach is based on the assumption that wind direction of the highest altitude measured by the windlidar already resembles the synoptic flow. Then, the direction of the synoptic flow is compared to the wind direction in which the gusts or jets occur. The result is presented in Figure 16. Again yellow (blue) colours mark high (low) occurrence probability.

Figure 16.

Correlation between the wind direction of a jet or gust and the highest measured wind direction above it. The relative frequency increases from blue over green and orange to yellow in arbitrary units. (a) Gusts, (b) Intermediate Jets, (c) Long Jets.

It can be seen from Figure 16a that the most frequent gusts at occur mostly when the synoptic flow comes from southerly direction ( to ). For the less frequent gusts around a wind shear is less apparent. A similar pattern can also be detected for the IJ (Figure 16b): mostly a synoptic wind from south to south-west coincides with IJ at around . Again, there are some cases for which a wind shear seems unlikely. For LJ the importance of wind shear is quite obvious (Figure 16c): whenever there is a long jet at around there is a minimum in probability that the synoptic flow is from to (and also for synoptic wind from NW). Similar to gusts and IJ, the long jets from the east occur with a corresponding synoptic flow from the south. All in all, wind from the sector between to seems to produce a higher probability for the occurrence of gusts and jets. Therefore the interaction between synoptic wind and orography seem to play an important role for the occurrence of these wind phenomena. WRF modelling of all of Svalbard should be able to prove this hypothesis.

5. Discussion

In a study with ERA-Interim reanalysis data by Champagne et al. [39], higher 2 m temperature anomalies occurred in winter over the entire study area of the European arctic (N to N, W to E) than in summer months, which are also associated with a change of the pressure systems. These anomalies contribute to a higher energy content of the atmospheric column, such as the vertical integrated transport of dry static energy and latent heat or reduction in the net heat loss of the arctic ocean by radiative and turbulent fluxes [40]. Additional to the study of Champagne et al. [39], the simulation of Wickström et al. [40] with ERA-Interim data from 1997–2016 detected an increased number of cyclones heading towards Svalbard in winter times [40,41,42]. This observation of a seasonal dependency of storms also contributes to the higher mean wind speed in winter, which was observed by the windlidar in Ny-Ålesund. However, a general increase of wind speed in winter was not observed in our data.

The trends of the mean velocities over the course of the year are tightly connected to the general wind pattern of the Arctic and are then influenced by small-scale effects, such as orography, at lower altitudes. There is a dominant wind direction towards ESE for the lowermost discussed tropospheric layer, since the mountains and the axis of the fjord are so dominant and channel the wind. Only if the synoptic wind comes from the direction of 315–360, which is the direction of the end of the fjord towards the open sea, the wind direction changes to NW. Analysing our wind roses we assume that most of the wind shear from local to synoptic direction occurs below 1000 m altitude. The orography therefore has no influence at this altitude anymore on the preferred wind direction. Furthermore, the change of the rotational direction changes with the time of the year. This is due to the change of the synoptic flow over the course of the year as presented by the ERA-interim reanalysis by Maturilli and Kayser [15]. An example is given by the comparison of winter (DJF) and summer (JJA) by Maturilli and Kayser [15]. Wind from the north is more common in summer, while on the other hand the south is the preferred direction of the large-scale wind patterns. This agrees with the results which are discussed in Section 3. Even at an altitude of about 800 m, the orography dominates the wind pattern. Further up, the wind field follows more and more the synoptic pattern over Svalbard.

Applying the definition of low-level jets Stull [38], we identified jets and gusts in the windlidar data, but called them “long jets”. Their shorter companions are called intermediate jets and gusts. According to Wexler [28] low-level jets are caused by a heated-up surface and convection. Due to the presence of polar night and a high number of long jets, this effect does not play a major role at this observation site in the Arctic. The observed duration of LJ is also in the range of the duration known from low-level jets at lower latitudes. Carroll et al. [43], Hodges and Pu [44], Smith et al. [45] amongst others found LLJ in the Great Planes, USA, or in the Northern Sea [46], which also last for several hours. As Blackadar [35] mentioned, the Coriolis force as the working principle of low-level jets plays an important role in the existence of them. Since the force itself depends on latitude and is strongest at the equator, it is obvious why significant higher wind speeds of LLJs are observed in lower latitudes, such as the Great Planes, USA [43,44] or in Australia [34].

Previous numerical and observational studies [13,30] presented low-level jets in the Arctic. Both studies partially took place in Ny-Ålesund but used a slightly different definition of LLJs than in this work, where an “event” is not distinguished between gust, intermediate jet and long jet. Moreover, wind maxima with the surface as wind minimum are considered as events. Low-level jets were only found at altitudes of 200–300 m using a tethered balloon, with a maximum altitude of 600 m [30]. The simulated height of the model revealed only altitudes of 20–50 m [13], while the measurement campaign by Vihma et al. [30] with tethered balloons reveals long jets at a mean height of m, a mean velocity of and wind direction of SE, which were caused by katabatic flows from the nearby glacier Brøggerbreen [30]. In the ABL experiment NYTEFOX by Zeller et al. [47] a typical speed of katabatic winds was observed with up to in parallel with clear sky conditions and a weak synoptic wind. In these conditions small-scale effects dominate the local ABL. The mean wind speed of Vihma et al. [30] and Kilpeläinen et al. [13] is lower than in the data measured by the windlidar, where a seasonal mean speed of was found (Figure 12a). The mean wind direction corresponds with the wind roses of this study (Figure 15), but still does not completely agree with the results measured by Vihma et al. [30]. Since the tethered balloon drifts with the wind and its measurement height is limited to the attached rope, LLJs at higher altitudes were not considered by Vihma et al. [30] at all and, therefore, the average height of long jets is significantly lower than in the data of the windlidar, with which good coverage are available up to 1000 m altitude (Figure 2).

Additional to the numerical simulation of Kilpeläinen et al. [13], the study by Mayer et al. [48] shows that the parameterisation of the fjord and the orography is very difficult and has a very big impact on the measured parameters. This difficulty is also found in the comparison of windlidar data with radiosondes of Ny-Ålesund. The two data sets show a different result when just looking at jets. We did not find any comparable wind maxima in the radiosonde data, which were simultaneously launched to the windlidar. Probably the sonde was already advected by the wind and the long jets are spatially a very small feature, because the atmosphere over Ny-Ålesund seems to be very heterogeneous. The data sets for gusts, intermediate jets and long jets are statistically independent in our study. Therefore, the described groups of wind phenomena differ from each other as well as the atmospheric situation, in which they were observed. The number of wind events drops by one magnitude by changing the category of wind events. This indicates that the polar atmosphere is much more temporarily variable than expected.

As Kilpeläinen et al. [13] found out, LLJs were strongest under high pressure conditions and low cloud fraction, as well as cold and dry air at a temperature inversion top. Similarly, the modelled LLJ strength correlated negatively with the near-surface temperature and specific humidity, which was also found in our study by a drastic decrease of long jets in July as the warmest month in Ny-Ålesund with no snow cover. In addition, the modelled LLJ strength was strongly dependent on the modelled near-surface wind direction. In Kongsfjord, the strongest modelled LLJs occurred when the wind direction was from the north and the wind came across the fjord [13]. The data of the windlidar on the other hand suggest that LJs usually occur when the wind direction is about (ESE), (SW) or (N). North in this data set shows the slowest long jets, while LJs from the ESE are strongest. The observed jet core wind directions and heights suggest that the katabatic winds were the most dominating factor creating LLJs [13]. Katabatic jets in general evolve with clear sky on glaciers and ice fields. Under these conditions the surface emits infrared radiation into space, cooling down the surface more and more until the air is cold enough to be no longer able to remain over the ice and slides down the glacier. Since the majority of windlidar-observed LJs are above the mountain tops, it is expected that they are not caused by katabatic winds, even though the nearby glaciers and the wind direction matches. In the comparison with the meteorology data of the BSRN field (Baseline Surface Radiation Network) in Ny-Ålesund, no correlation between clear days and the appearance of long jets was found. In general about of the time the sky is not covered by clouds. For gusts, it was clear for , for intermediate jets and for LJ. Clouds in general have a bottom base height of 1430 m, while the base height appears for gusts at 1547 m, 1664 m for IJ and 1529 m for LJ. When LJ appear, the sky is slightly less cloudy, while clouds are higher for gusts and intermediate jets than on average. However, these deviations are very small. Therefore we conclude, that katabatic winds are not the driving mechanisms of these gusts and jets over Ny-Ålesund. Furthermore, mechanisms such as heating of the surface and convection as described by Wexler [28] do not apply to the Arctic with the presence of polar night and a presence of jets and gusts.

The properties of long jets statistically analysed reveal for most of the variables that they are statistically independent over the annual cycle. Hence, the rotation of the wind roses and the change of the dominating wind direction with increasing height (Section 3) do not influence the occurrence of long jets in general. The evolution progress of LJs in the Arctic does therefore not depend on the height. In future studies the meteorology of the BSRN field, the ceilometer or radiometers in Ny-Ålesund can be considered to identify the driving mechanism of these jets by taking temperature inversion layers into account, which were created for example by in the fjord trapped gravity waves and synoptic processes. For all of the three groups (LJ, IJ, gusts) the relative frequency of appearance is probably related to the wind shear zones [14], where a minimum of wind speed occurs. With these minima below and above it is more probable to find an event in this altitude range.

The two maxima in the frequency of gusts at around 550 m and 800 m altitude corresponds to the result of Section 3. These two levels were identified at the transitions between the lowermost layer, dominated by the orography, and the transition layer, as well as the transition layer and the free troposphere, dominated by large-scale synoptic wind fields. The decoupled atmospheric layer close to the surface of Kongsfjord was also observed by Maturilli and Kayser [15] based on 22 years of continuous radiosonde measurements launched daily form Ny-Ålesund. The overall increase of maximum wind speed of the gusts is (probably) caused by the absence of friction at the orography and small-scale turbulences due to obstacles.

On the other hand a clear correlation was found between the direction of the jet core and the height. The most probable direction of wind events is equivalent with the most dominant directions of the wind roses (Section 3.2). Moreover, the gusts and jets mainly occurred for synoptic wind from south. Two conclusions can be drawn from this fact. First, the local orography is an important driver for these wind peaks. Second, whenever the Svalbard region faces direct transport from Europe (synoptic flow from south) these gusts and jets are frequent and may lead to a wind-induced mixing in an otherwise thermally stably-stratified atmosphere via bulk Richardson number [9]. This will have implications for the vertical distribution and, hence, radiative forcing of pollutants. Dall’Osto et al. [49] amongst others show a clear variability in day-to-day aerosol concentration between Zeppelin station and the nearby aerosol in situ sampling site Gruvebadet. Hence, the question when the air column above Ny-Ålesund and at Zeppelin station is within the same air mass is important for the correct interpretation of the numerous high-quality data sets collected at this site [50]. During advection from south the local downward mixing of pollutants may be more effective.

With the results of Section 4 we conclude that the origin of the jets and gusts is not a phenomenon caused only by the ABL, but rather takes place in a turbulent transition layer between the surface layers and the free troposphere. As Figure 16 already shows, there is a very strong effect by channelling towards the fjord axis to produce jets and gusts. While the direction of the synoptic wind is not parallel towards the fjord, but hits the mountains of Brøggerhalvøya, some of the air masses are lifted over the mountain chain, causing a compression of the stream lines. The second and largest part of the air mass is pushed around the mountains, creating a constant wind from the ESE. In the merging height non-linear, turbulent mixing happens to vertices, stretched apart by the dominant wind from ESE parallel to the fjord axis. This mixing creates rotors in a turbulent mixing zone of about 400 m to 1000 m, which are maybe the origin of the gusts and jets. Sometimes the turbulent structure is stable enough to produce jets from the length of up to some hours. This would also explain the drastic change of numbers between gusts and jets (Table 2). This shear zone and the local variability of the wind field explain the disagreement between the results of Gruvebadet at an elevation of 33 m above sea level and Zeppelin station at 474 m above sea level [49], since the station in the mountain might already be in this turbulent zone. Serafin et al. [51] describes the different types of ABLs in mountainous terrain. The discussed turbulence is comparable with the results of the windlidar data and the wind field in Ny-Ålesund: with small energy input, the ABL is stable in respect of multi-scale interactions. Perpendicular to Kongsfjord the wind either flows downhill beneath the stable ABL, being trapped at the surface, and may lead to boundary-layer separation and related turbulence, or forms a wave structure in the layer of mountain tops with elevated turbulence. Since Kongsfjord is broad compared to the surrounding mountains, we expect a mixture of all of these phenomena on top of a channelling of the wind parallel to the fjord axis. However, the physical process and the mechanism causing gusts and jets cannot be determined by the analysed data set of the windlidar due to the time resolution of 50 m and 10 min. Therefore we conclude that all of these multi-scale effects result then in a very complex turbulent shear zone at approximately the height of the mountain tops.

6. Conclusions

We have presented wind patterns and special wind phenomenons over Ny-Ålesund, Svalbard, in windlidar data from 2013–2021. A predominant wind direction towards ESE in all seasons was found at an altitude of 500 m. Further up the wind rotates towards the synoptic direction. At a height of 800 m the data availability reaches a maximum, which correlates to the dominant altitude of the cloud base height according to studies of Maturilli and Ebell [21]. The comparison of windlidar data with daily launched radiosondes reveals that the general pattern of the wind structure is found in both data sets (Schulz [16], Burgemeister [20] and Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7). More than 24,000 wind events were found and classified as gusts, intermediate jets (IJ) or long jets (LJ) in the windlidar data of the nine year long presented measurement time. These usually short lasting events are not resolved by the daily launched radiosondes at AWIPEV in Ny-Ålesund which are drifting with the wind and provide, hence, a different kind of data set. Therefore, a synergy of different instruments and measurement techniques will reveal different aspects of the Arctic atmosphere and its phenomenona in the future. Our main results can be summarised as follows:

- The data coverage within the lowermost 1 km altitude is . At the 500 m level the availability reaches . However, above 2 km altitude the aerosol load is not sufficient to produce a valid wind measurement in the Arctic environment.

- The orography of Kongsfjord plays a major role in the wind pattern of the lowermost 500 m layer. The wind directions of ESE dominate; sometimes wind from NW and SW occurs. Neither a trend nor a seasonal dependence has been found.

- Above the surrounding mountains at around 800 m height, the wind direction rotates towards the synoptic flow and the orography loses its dominant impact on the wind direction.

- Abrupt changes in wind speed and direction can occur. Therefore, wind profiling via a few radio soundings per day is not sufficient to monitor the wind situation over the course of a day. Especially wind driven turbulence and temporal variation of ABL height might be clearly underestimated if only radiosonde data were considered for the analysis.

- The mean wind speed is in winter usually higher than in summer months for three discussed heights. Moreover, the number of days with high wind speeds () is larger in winter than in summer.

- In this study we define intermediate jets, between gusts and long jets in terms of duration. All these three events have a similar geometrical depth of 500 m to 700 m, with a slightly thinner depth during summer. The trend during the course of a year is similar for all three categories. Gusts show in general the largest standard deviation in their monthly depth but on the other hand the smallest trend on a annual scale.

- We found wind gusts and jets in of the data equally distributed over the course of the year.

- Jets and gusts mainly occur between 400 m to 1100 m altitude with a maximum wind speed of to .

- The properties of long jets, such as maximum wind speed, life-time, height and geometrical depth, are generally independent from season to season. During summer LJ occur lower and geometrically thinner, while in the first six months of the year the long jets have slightly lower maximal velocities.

- Jets and gusts appear in distinct directions and at well defined altitudes, which corresponds with the wind roses of Section 3.2 as well as with the orography of Kongsfjord (mostly gusts and jets were found at , some around wind direction). No trend was found in a change of wind speed or wind direction for the jets.

- The occurrence of gusts and jets does not depend on cloud cover. Hence, a katabatic origin is unlikely. Instead, they occur more frequently with a synoptic flow from south. Therefore, at least a fraction of the observed gusts and jets are caused by the interaction between synoptic flow and orography.

- The observed long jets do not look like low-level jets, which were defined by Wexler [28] and Stull [38] amongst others, since it is more probable that they are caused by a complex interaction between lifting and channelling mechanism of the wind in Kongsfjord and the mountain chain of Brøggerhalvøya. However, for a clear classification comparisons with high-resolution, continuous temperature measurements or glider experiments within the turbulent shear zone are needed.

- There are clear indications that a turbulent wind shear zone is present at every time of the year at a height of about 400 m to 1000 m. These turbulence are caused by a channelling by Kongsfjord and lifting mechanisms over the surrounding mountains.

- Since we conclude gusts and jets originate from turbulence, it is expected that their life time is very short in general and longer living jets are rare.

Since the ABL is difficult to parameterise and features change on temporarily and spatially small scales [13,16,24,48], the presented nine years of windlidar data can be used to improve the understanding of the ABL dynamics in the vicinity of Ny-Ålesund or to validate or constrain high resolution climate models such as WRF or LES. Additionally, a motivation of investigating these very local and temporal short lasting jets further would be to improve flight safety for the small planes, UAVs or helicopters operating in the valley of Kongsfjord. Moreover, it could be worthwhile to compare this data set on the wind above Ny-Ålesund to the wind field at Zeppelin station and the meteorologic climate change tower (CCT) for a complete characterisation of the ABL height and stability. Glider and drone experiments within the turbulent shear zone would also help to understand the wind field along the fjord axis for in-situ as well as small-scale measurements of this turbulent wind shear zone. This would greatly improve the interpretation of the numerous aerosol and trace gas measurements in Ny-Ålesund, such as Graßl and Ritter [52], and at Zeppelin station, for example Tunved et al. [53] amongst many others, connect the ABL with the free troposphere and, hence, reduce the according uncertainties in climate models for the polar region.

Author Contributions

This work was basically performed by S.G., C.R., as PI of the instruments, acted as the supervisor and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. The routines for windlidar evaluation were developed by S.G. and based on existing scripts by C.R. and A.S. The work was advised and brought into the relationship with the boundary layer meteorology by A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The entire used data set from 2013–2021 is available as a data collection on the PANGAEA data repository [54]: https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.939662 (accessed on 1 August 2022).

Acknowledgments

The windlidar was serviced at AWIPEV, Ny-Ålesund, by several Observatory Engineers. We thank Amelie Driemel for assisting with the PANGAEA data repository. Thanks also to Ludwig Wagner from GWU Umweltphysik for quick and helpful technical support and spare part supply over the whole period. We also thank Roland Neuber and Marion Maturilli as scientific coordinators of AWIPEV, who supported the project over all the years.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Serreze, M.C.; Barry, R.G. Processes and impacts of Arctic amplification: A research synthesis. Glob. Planet. Chang. 2011, 77, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overland, J.E.; Wang, M. Resolving Future Arctic/Midlatitude Weather Connections. Earth’S Future 2018, 6, 1146–1152. Available online: https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1029/2018EF000901 (accessed on 1 August 2022). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cohen, X.J.; Zhang, J.F. Divergent consensuses on Arctic amplification influence on midlatitude severe winter weather. Nat. Clim. Change 2020, 10, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R.J.; Hanna, E.; Chen, L. Winter Arctic Amplification at the synoptic timescale, 1979–2018, its regional variation and response to tropical and extratropical variability. Clim. Dyn. 2021, 56, 457–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlke, S.; Maturilli, M. Contribution of atmospheric advection to the amplified winter warming in the Arctic North Atlantic region. Adv. Meteorol. 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boike, J.; Juszak, I.; Lange, S.; Chadburn, S.; Burke, E.; Overduin, P.P.; Roth, K.; Ippisch, O.; Bornemann, N.; Stern, L.; et al. A 20-year record (1998–2017) of permafrost, active layer and meteorological conditions at a high Arctic permafrost research site (Bayelva, Spitsbergen). Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2018, 10, 355–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karner, F.; Obleitner, F.; Krismer, T.; Kohler, J.; Greuell, W. A decade of energy and mass balance investigations on the glacier Kongsvegen, Svalbard. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2013, 118, 3986–4000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gryanik, V.M.; Lüpkes, C.; Grachev, A.; Sidorenko, D. New Modified and Extended Stability Functions for the Stable Boundary Layer based on SHEBA and Parametrizations of Bulk Transfer Coefficients for Climate Models. J. Atmos. Sci. 2020, 77, 2687–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, H.; Basu, S.; Holtslag, A.A.M. Improving Stable Boundary-Layer Height Estimation Using a Stability-Dependent Critical Bulk Richardson Number. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 2013, 148, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Liu, L.; Hu, F.; Fan, G.; Huo, J. Nocturnal Boundary Layer Evolution and Its Impacts on the Vertical Distributions of Pollutant Particulate Matter. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beine, H.; Argentini, S.; Maurizi, A.; Mastrantonio, G.; Viola, A. The local wind field at Ny-Å lesund and the Zeppelin mountain at Svalbard. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 2001, 78, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argentini, S.; Viola, A.P.; Mastrantonio, G.; Maurizi, A.; Georgiadis, T.; Nardino, M. Characteristics of the boundary layer at Ny-Ålesund in the Arctic during the ARTIST field experiment. Ann. Geophys. 2003, 46, 3414. [Google Scholar]

- Kilpeläinen, T.; Vihma, T.; Manninen, M.; Sjöblom, A.; Jakobson, E.; Palo, T.; Maturilli, M. Modelling the vertical structure of the atmospheric boundary layer over Arctic fjords in Svalbard. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2012, 138, 1867–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Esau, I.; Repina, I. Wind Climate in Kongsfjorden, Svalbard, and Attribution of Leading Wind Driving Mechanisms through Turbulence-Resolving Simulations. Adv. Meteorol. 2012, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maturilli, M.; Kayser, M. Arctic warming, moisture increase and circulation changes observed in the Ny-Ålesund homogenized radiosonde record. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2017, 130, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schulz, A. Die Arktische Grenzschichthöhe Auf Der Basis Von Sondierungen Am Atmosphärenobservatorium in Ny-Ålesund Und Im ECMWF-Modell. Diploma Thesis, University of Potsdam, Potsdam, Germany, 2012. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10013/epic.40738.d001 (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Schulz, A. Untersuchung Der Wechselwirkung Synoptisch-Skaliger Mit Orographisch Bedingten Prozessen in Der Arktischen Grenzschicht über Spitzbergen. Ph.D Thesis, University of Potsdam, Potsdam, Germany, 2017. Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:kobv:517-opus4-400058 (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Ori, D.; Schemann, V.; Karrer, M.; Dias Neto, J.; von Terzi, L.; Seifert, A.; Kneifel, S. Evaluation of ice particle growth in ICON using statistics of multi-frequency Doppler cloud radar observations. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2020, 146, 3830–3849. Available online: https://rmets.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/qj.3875 (accessed on 1 August 2022). [CrossRef]

- Moroni, B.; Becagli, S.; Bolzacchini, E.; Busetto, M.; Cappelletti, D.; Crocchianti, S.; Ferrero, L.; Frosini, D.; Lanconelli, C.; Lupi, A.; et al. Vertical profiles and chemical properties of aerosol particles upon Ny-Ålesund (Svalbard Islands). Adv. Meteorol. 2015, 2015, 292081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgemeister, S. Windstruktur Einer Arktischen Grenzschicht Am Beispiel Ny-Ålesund. Ph.D Thesis, Universität Potsdam, Potsdam, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Maturilli, M.; Ebell, K. Twenty-five years of cloud base height measurements by ceilometer in Ny-Ålesund, Svalbard. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2018, 10, 1451–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Treffeisen, R.; Krejci, R.; Ström, J.; Engvall, A.C.; Herber, A.; Thomason, L. Humidity observations in the Arctic troposphere over Ny-Ålesund, Svalbard based on 15 years of radiosonde data. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2007, 7, 2721–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sodemann, H.; Foken, T. Special characteristics of the temperature structure near the surface. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2005, 80, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kral, S.T.; Reuder, J.; Vihma, T.; Suomi, I.; Haualand, K.F.; Urbancic, G.H.; Greene, B.R.; Steeneveld, G.J.; Lorenz, T.; Maronga, B.; et al. The innovative strategies for observations in the Arctic Atmospheric Boundary Layer Project (ISOBAR): Unique finescale observations under stable and very stable conditions. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2021, 102, E218–E243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jocher, G.; Schulz, A.; Ritter, C.; Neuber, R.; Dethloff, K.; Foken, T. The sensible heat flux in the course of the year at Ny-Ålesund, svalbard: Characteristics of eddy covariance data and corresponding model results. ADvances Meteorol. 2015, 2015, 852108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westermann, S.; Lüers, J.; Langer, M.; Piel, K.; Boike, J. The annual surface energy budget of a high-arctic permafrost site on Svalbard, Norway. Cryosphere 2009, 3, 245–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maturilli, M.; Herber, A.; König-Langlo, G. Surface radiation climatology for Ny-Ålesund, Svalbard (78.9 N), basic observations for trend detection. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2015, 120, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wexler, H. A boundary layer interpretation of the low-level jet. Tellus 1961, 13, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andreas, E.L.; Claffy, K.J.; Makshtas, A.P. Low-level atmospheric jets and inversions over the western Weddell Sea. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 2000, 97, 459–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vihma, T.; Kilpeläinen, T.; Manninen, M.; Sjöblom, A.; Jakobson, E.; Palo, T.; Jaagus, J.; Maturilli, M. Characteristics of temperature and humidity inversions and low-level jets over Svalbard fjords in spring. Adv. Meteorol. 2011, 2011, 486807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renfrew, I.A.; Anderson, P.S. Profiles of katabatic flow in summer and winter over Coats Land, Antarctica. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. J. Atmos. Sci. Appl. Meteorol. Phys. Oceanogr. 2006, 132, 779–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brümmer, B.; Kirchgäßner, A.; Müller, G. The atmospheric boundary layer over Baltic Sea ice. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 2005, 117, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langland, R.H.; Tag, P.M.; Fett, R.W. An ice breeze mechanism for boundary-layer jets. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 1989, 48, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.C. Australian Low Level Jet Climatology; Bureau of Meteorology: Melbourne, Australia, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Blackadar, A.K. Boundary layer wind maxima and their significance for the growth of nocturnal inversions. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1957, 38, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bonner, W.D. Climatology of the low level jet. Mon. Weather Rev. 1968, 96, 833–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Malcher, J.; Kraus, H. Low-level jet phenomena described by an integrated dynamical PBL model. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 1983, 27, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stull, R.B. An Introduction to Boundary Layer Meteorology; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands; Boston, MA, USA; London, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Champagne, O.; Pohl, B.; McKenzie, S.; Buoncristiani, J.F.; Bernard, E.; Joly, D.; Tolle, F. Atmospheric circulation modulates the spatial variability of temperature in the Atlantic–Arctic region. Int. J. Climatol. 2019, 39, 3619–3638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickström, S.; Jonassen, M.; Vihma, T.; Uotila, P. Trends in cyclones in the high-latitude North Atlantic during 1979–2016. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2020, 146, 762–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tamarin-Brodsky, T.; Kaspi, Y. Enhanced poleward propagation of storms under climate change. Nat. Geosci. 2017, 10, 908–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielec-Bąkowska, Z.; Widawski, A. Strong anticyclones and deep cyclones over Svalbard in the years 1971–2015. Boreal Environ. Res. 2018, 23, 283–297. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, B.J.; Demoz, B.B.; Delgado, R. An overview of low-level jet winds and corresponding mixed layer depths during PECAN. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2019, 124, 9141–9160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, D.; Pu, Z. Characteristics and variations of low-level jets and environmental factors associated with summer precipitation extremes over the Great Plains. J. Clim. 2019, 32, 5123–5144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.N.; Gebauer, J.G.; Klein, P.M.; Fedorovich, E.; Gibbs, J.A. The Great Plains low-level jet during PECAN: Observed and simulated characteristics. Mon. Weather Rev. 2019, 147, 1845–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wagner, D.; Steinfeld, G.; Witha, B.; Wurps, H.; Reuder, J. Low Level Jets over the Southern North Sea. Meteorol. Z. 2019, 28, 389–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeller, M.L.; Huss, J.M.; Pfister, L.; Lapo, K.E.; Littmann, D.; Schneider, J.; Schulz, A.; Thomas, C.K. The NY-Ålesund TurbulencE Fiber Optic eXperiment (NYTEFOX): Investigating the Arctic boundary layer, Svalbard. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 3439–3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, S.; Jonassen, M.O.; Sandvik, A.; Reuder, J. Profiling the Arctic stable boundary layer in Advent Valley, Svalbard: Measurements and simulations. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 2012, 143, 507–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dall’Osto, M.; Beddows, D.; Tunved, P.; Harrison, R.M.; Lupi, A.; Vitale, V.; Becagli, S.; Traversi, R.; Park, K.T.; Yoon, Y.J.; et al. Simultaneous measurements of aerosol size distributions at three sites in the European high Arctic. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2019, 19, 7377–7395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Platt, S.M.; Hov, Ø.; Berg, T.; Breivik, K.; Eckhardt, S.; Eleftheriadis, K.; Evangeliou, N.; Fiebig, M.; Fisher, R.; Hansen, G.; et al. Atmospheric composition in the European Arctic and 30 years of the Zeppelin Observatory, Ny-Ålesund. Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss. 2022, 22, 3321–3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafin, S.; Adler, B.; Cuxart, J.; De Wekker, S.F.; Gohm, A.; Grisogono, B.; Kalthoff, N.; Kirshbaum, D.J.; Rotach, M.W.; Schmidli, J.; et al. Exchange processes in the atmospheric boundary layer over mountainous terrain. Atmosphere 2018, 9, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Graßl, S.; Ritter, C. Properties of Arctic Aerosol Based on Sun Photometer Long-Term Measurements in Ny-Ålesund, Svalbard. Remote. Sens. 2019, 11, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tunved, P.; Ström, J.; Krejci, R. Arctic aerosol life cycle: Linking aerosol size distributions observed between 2000 and 2010 with air mass transport and precipitation at Zeppelin station, Ny-Ålesund, Svalbard. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2013, 13, 3643–3660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Graßl, S.; Ritter, C. Windlidar data from Ny-Ålesund, Svalbard (AWIPEV). 2021. Available online: https://doi.pangaea.de/10.1594/PANGAEA.939662 (accessed on 1 August 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |