Abstract

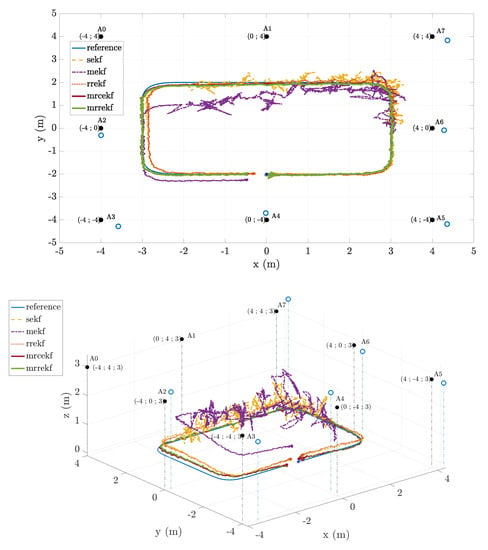

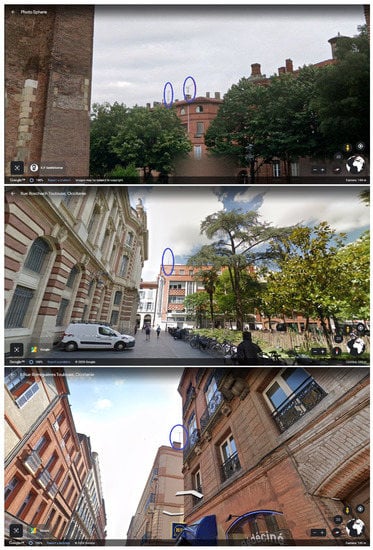

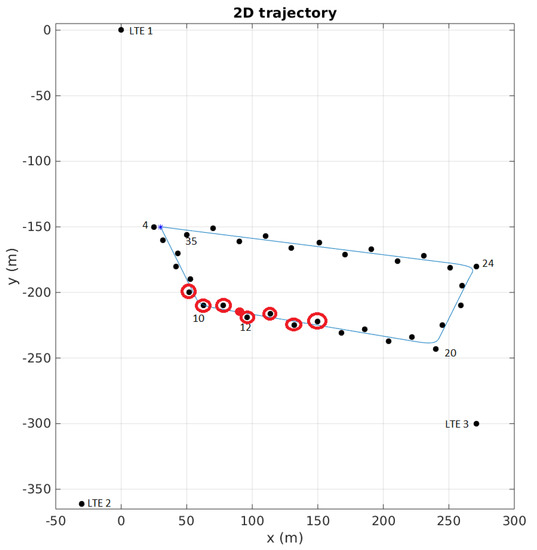

Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) is the technology of choice for outdoor positioning purposes but has many limitations when used in safety-critical applications such Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS) and Unmanned Autonomous Systems (UAS). Namely, its performance clearly degrades in harsh propagation conditions and is not reliable due to possible attacks or interference. Moreover, GNSS signals may not be available in the so-called GNSS-denied environments, such as deep urban canyons or indoors, and standard GNSS architectures do not provide the precision needed in ITS. Among the different alternatives, cellular signals (LTE/5G) may provide coverage in constrained urban environments and Ultra-Wideband (UWB) ranging is a promising solution to achieve high positioning accuracy. The key points impacting any time-of-arrival (TOA)-based navigation system are (i) the transmitters’ geometry, (ii) a perfectly known transmitters’ position, and (iii) the environment. In this contribution, we analyze the performance loss of alternative TOA-based navigation systems in real-life applications where we may have both transmitters’ position mismatch, harsh propagation environments, and GNSS-denied conditions. In addition, we propose new robust filtering methods able to cope with both effects up to a certain extent. Illustrative results in realistic scenarios are provided to support the discussion and show the performance improvement brought by the new methodologies with respect to the state-of-the-art.

1. Introduction

Reliable and precise position, navigation, and timing (PNT) information is fundamental in safety-critical applications such as Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS), automated aircraft landing, or Unmanned Autonomous Systems (UAS), i.e., unmanned autonomous ground/air vehicles (robots/drones). In addition, in the context of ITS, this is not only of capital importance for the autonomously navigating system, but also for vulnerable road users, such as cyclists and pedestrians, and systems collaterally using this information, i.e., in traffic control and for emergency services. Even if the main source of positioning information are still Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS), they lack of reliability and accuracy in constrained environments such as highly populated areas, which limit their adoption as standalone PNT systems. For instance, GNSS may be affected by attacks such as jamming and spoofing [1], or be severely affected in harsh propagation conditions [2]. Moreover, standard GNSS may not provide the precision needed in the ITS context, i.e., submeter lane-level precision. Several GNSS carrier phase-based precise PNT solutions exist to improve the latter, for instance, Real-Time Kinematics (RTK) ([3] Chapter 26) or Precise Point Positioning (PPP) techniques ([3] Chapter 25), but they need either a reference station or precise corrections which do not allow real-time processing, and are even more affected by harsh propagation conditions than standard GNSS code-based techniques. In addition, these systems may not be available at all in the so-called GNSS-denied environments, such as deep urban canyons or indoors, and therefore robust alternatives must be accounted for.

Several alternatives to GNSS exist: (i) exploitation of cellular signals (LTE/5G) [4] or other signals-of-opportunity (SoO) [5]; (ii) the combination with local inertial navigation systems (INS) [6]; (iii) the use of vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) or vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I) communications, such as Dedicated Short-Range Communications (DSRC), which use the IEEE802.11p protocols to obtain peer-to-peer measurements [7,8]; or (iv) more complicated approaches using cameras, LIDARs; and/or radars [9] or in unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) cooperation scenarios [10,11]. Among these alternatives, extensive research explored the use of cellular signals for positioning (i.e., see [4,12,13,14,15] and references therein) and its use as a promising complement to GNSS and other navigation systems [16,17]. However, as pointed out in [17], the combination of both map matching, cellular signals, INS, and GNSS in urban environments, leads to standard deviations approximately equal to 3 m (i.e., error around 10 m). Therefore, cellular, GNSS, and standard multisensor data fusion strategies do not provide a precise enough navigation solution for ITS and safety-critical applications such as autonomous driving and UAS. This is even more critical under harsh propagation conditions found in urban environments, which further degrade the performance of all these navigation systems.

In contrast to the use of SoO, such as cellular signals, a different approach is to consider dedicated infrastructure specifically designed to provide precise ranging measurements. This is the case of impulse-radio Ultra-Wideband (UWB) technologies, which are typically based on time-of-arrival (TOA) two-way ranging measurements and can achieve a sub-decimeter level ranging accuracy in line-of-sight (LOS) nominal conditions [5,18], being two orders of magnitude lower than GNSS and LTE ranging measurements. UWB-based positioning has been mainly explored as an alternative for indoor positioning where GNSS is not available [19,20,21,22,23]. With respect to other ranging technologies, UWB has the additional advantage to be more robust to interference.

In general, TOA-based navigation (i.e., UWB or LTE) has the fundamental drawback that transmitters’ position is assumed to be perfectly known, which may not be the case in real-life applications. Given the sub-decimeter nominal accuracy of UWB-based systems, this may have a strong impact on the final performance as it has been recently shown in [24]. This is also a critical point if UWB ranging measurements are used in multisensor data fusion platforms, for instance, in combination with GNSS, which require a common navigation coordinate frame [25]. Therefore, in real-life applications, a mismatch on the transmitters’ position is a key point to be carefully analyzed for reliable TOA-based navigation. In addition, harsh propagation conditions such as multi-path, fading, and non-line-of-sight (NLOS) conditions may also have a non-negligible impact on the final performance. Then, both model mismatch and harsh environments must be taken into account.

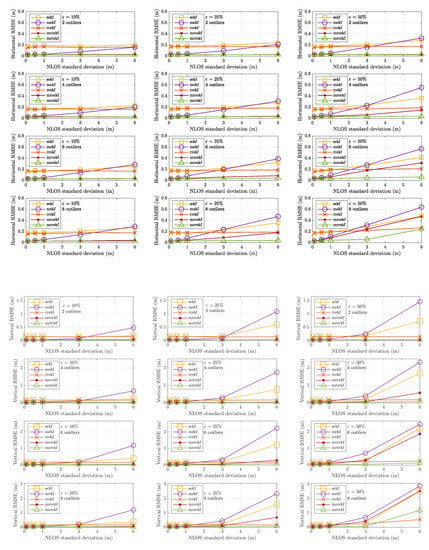

In this contribution, based on the preliminary results in [24], where we proposed an augmented state extended Kalman filter (EKF) to cope with possible UWB anchor position mismatch under nominal Gaussian conditions, we further explore robust TOA-based navigation in realistic scenarios with model mismatch and affected by harsh propagation conditions. We consider that several transmitter to receiver links may be affected by multi-path or NLOS conditions, then we assume the typical contamination model arising in robust statistics [26] for a subset of (corrupted) ranging measurements. Without model mismatch, a possible solution is to consider a robust regression-based EKF [26], but this methodology does not apply when both outliers and model mismatch are present, mainly because the filter cannot distinguish between true measurement outliers and measurements which deviate from the nominal due to the mismatch. Therefore, we propose new robust filtering strategies able to cope with both effects. Illustrative realistic simulation results are provided to support the discussion and show the performance improvement brought by these new robust TOA-based navigation methodologies.

The article is organized as follows. The TOA-based state estimation problem under model mismatch and non-nominal conditions is described in Section 2. State-of-the-art EKF-based solutions are given in Section 3. The derivation of new robust filtering techniques under model mismatch is detailed in Section 4. The performance of such methods, compared to state-of-the-art solutions, is shown and discussed in Section 5 and Section 6. Finally, conclusions and remarks are drawn in Section 7.

3. State-of-the-Art EKF-Based Solutions

3.1. Standard Extended KF Solution

Considering the SSM in (2) and (3), it is easy to design an EKF [29], which needs a linearized (approximated) measurement equation, given by the following Jacobian matrix (evaluated at a given point and with ),

The standard TOA-based navigation solution is obtained by applying the EKF to the assumed models (2) and (3):

with . Notice that, for , the linear KF recursion is only valid if and (mean and covariance of the initial state) [30], which in practice are unknown. An appropriate way to initialize the filter is thus needed.

A practical solution is to use as initial estimate the linear minimum variance distortionless response (LMVDR) estimator, which coincides with the weighted least squares estimator (WLSE) of , and is given by

In this case, due to the nonlinearity of the measurement equation, the WLSE must be replaced by an iterative WLSE.

In case of model mismatch, the standard EKF-based solution is blind because it directly uses the assumed (mismatched) measurements . This solution can always be used and may provide acceptable results (depending on the application requirements) if .

3.2. Augmented-State EKF Solution

An alternative to the previous standard EKF, which does not take into account the possible model mismatch, was recently proposed in [24]. The idea is to consider an augmented state, , that is, to include the (partially) unknown into the state to be estimated. The process equation in this case is given by

and the measurement equation as in (2). The corresponding Jacobian matrix (dimension ) is

with being the i-th LOS unit vector. It has been shown in [24] that this provides better results w.r.t. the standard EKF if not all the Tx positions are partially unknown (i.e., ). In order to take into account the Tx position uncertainty, the measurement noise covariance is modified w.r.t. , where the variance of the possibly mismatched measurements is set to

A possible choice of is to consider a maximum bias, for instance, a uniformly distributed random position bias , with . If the bias is equal on every coordinate, , then .

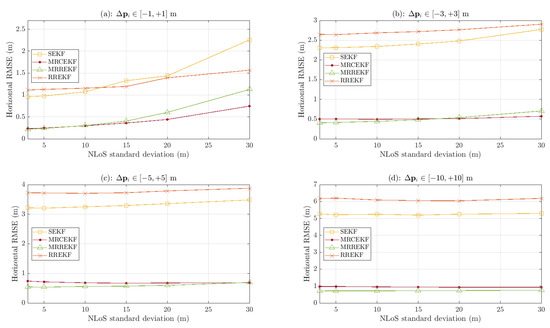

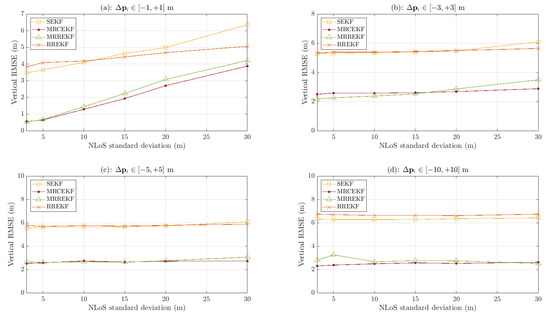

However, this solution only tackles the Tx mismatch problem and is not designed, as for the standard EKF, to cope with possible harsh propagation conditions, i.e., non-nominal perturbations on the noise . Therefore, as it will be shown in Section 5 and Section 6, it is not a robust solution and new methodologies must be designed for real-life applicability.

4. Robust Filtering under Model Mismatch

How to deal with measurements under the contamination model in (7) has been studied for several decades in the field of robust statistics. A recent publication provides an excellent introduction with several applications to practical signal processing problems [26]. In the sequel, we first give a brief introduction on the idea behind the most basic robust methods, and then explain how these concepts can be exploited to design robust filtering methods under model mismatch.

4.1. The Idea behind Robust Estimation

We consider as an example the linear regression problem, , where we want to estimate and the noise components are i.i.d. If we define the residuals the solution is given by the least squares (LS) estimator,

where we introduced the normalization of the residuals. Notice that a single outlier can destroy our estimate; thus, it is not a robust solution. Instead of using a quadratic function of the residuals, we can consider a general loss function (and its derivative for the minimization, ) as

and, for instance, and correspond to the LS and estimators. The most common is the so-called Huber function:

where the value a is chosen to obtain a given efficiency (deviation from the optimal under nominal conditions), for instance, for a 95% efficiency. The idea is that residuals with large errors are downweighted. To solve the problem in (15) we need the residuals standard deviation , or a robust estimate of it, for instance the normalized median absolute deviation (MAD), , defined as

where is the median and a normalizing constant (typically ). Considering the weight function in (16c) it is easy to see that (15) can be rewritten as

which can be solved by an iterative reweighted LS and is the so-called regression M-estimator. Notice that other cost functions can be considered, and more evolved estimators such as the MM-estimator exist [26]. As discussed in [2], for TOA-based navigation problems an important point is the measurement redundancy, that is, having enough observations to be able to find the solution.

4.2. Standard Robust Regression EKF

The robust regression M-estimator introduced in Section 4.1 can be used within the EKF framework in order to obtain a robust EKF [26]. Notice that the problem of interest is the one where we may have outliers in the observations and the residuals are related to the innovation sequence . A first approach is to use a robust score function in order to directly downweight the innovation vector, then not modifying the EKF recursion. Another more general approach is to reformulate the EKF as a regression problem and then use at every t a robust regression M-estimate of , being the so-called robust regression EKF (RREKF) ([26] Chapter 7). Notice that both approaches were not developed to cope with a possible model mismatch and they are not directly suited for the navigation problem in this contribution (i.e., as it will be shown in Section 6). Obviously, one can combine the original RREKF with the augmented state in Section 3.2, but the underlying problem to apply these techniques to the mismatched SSM is that the filter is not able to distinguish between true measurement outliers and measurements which deviate from the nominal due to the mismatch. Therefore, new robust solutions under mismatch must be sought.

4.3. Robust Regression EKF for Mismatched Models

Carefully analyzing the robust M-estimator downweighting process, that is, , we see that the normalizing term is a key parameter for the filter. Indeed, if is larger than the nominal variance, large outliers will not be downweighted and degrade the solution. In contrast, if this term is lower than the nominal then meaningful information will be disregarded by the filter. Recall that the problem is to deal with possibly corrupted measurements where the noise is distributed according to the contamination model in (7). In addition, some of the measurements may be biased due to the model mismatch. Then, in practice, we can modify (7) to include the effect of the mismatch as

With the nominal distribution being , the main problem of the RREKF is that it is not able to correctly distinguish among and . Moreover, within the augmented state EKF framework, measurements arising from should not be understood as faulty measurements, because these observations are the ones that allow the filter (which includes in the state) to converge to the true Tx positions, and recursively correct the mismatch.

Then, a possible robust EKF solution which is able to cope with model mismatch (named MRREKF), and thus avoid to downweight measurement errors induced by model mismatch is

- (i)

- first, consider the augmented-state formulation in Section 3.2 to cope with the Tx mismatch;

- (ii)

- second, consider a RREKF-based solution; and

- (iii)

- within the M-estimator, instead of the MAD, use a mismatched three sigma rule to normalize the residuals, that is,

This may be seen as a compromise between the 3-rejection or score function type robust EKF ([26] 7.3.1) and the robust regression KF ([26] 7.3.5), in order to control the filter behavior under model mismatch. Surprisingly, to the best of our knowledge, this simple solution has not been explored in the literature. As it will be shown in Section 6, this method behaves extremely well for the problem under study. The price to be paid w.r.t. the standard and augmented state EKFs, is that this solution includes an iterative procedure to find the robust estimate at every Kalman iteration. The iteration procedure terminates either after a fixed number of iterations or when the normalized difference between the actual and previous state estimate is smaller than a fixed threshold. Thus, the computational time will mainly depend on these two parameters. This may be critical in very low cost platforms and real-time applications. This is the reason why we propose an low cost alternative in the sequel.

4.4. Computationally Efficient Solution: Robust Weighting Uncertainty Indicator for Robust EKF

One of the limitations of the previous RREKF and MRREKF is their computational complexity, that is, within every EKF time step there is an iterative reweighted LS algorithm to solve the regression M-estimation problem, which, depending on the application at hand, may be a limiting factor. Therefore, we consider another computationally light alternative to the RREKF, which relies on the use of a robust weighting function in order to update the statistical characteristic of the measurement noise variance. Indeed, the performance of the EKF is highly affected by the measurement covariance matrix, ; therefore, one or more contaminated measurements will have a significant impact on the filter performance.

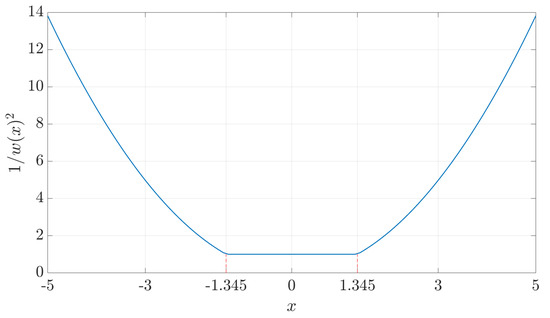

The proposed method is based on the values taken by the normalized residuals (i.e., innovations) as introduced in Section 4.1. In order to reduce the impact of the contaminated measurements on the estimator, the idea is to increase the variance of each contaminated measurement depending on the value of . To do so, we propose in this study to use the square inverse of Huber’s weighting function, as shown in Figure 1, to adjust the measurement noise variances. Thus, in the case of large residuals, i.e., , and in the framework of Tx position mismatch, the variance can be formulated as

Figure 1.

Square inverse of Huber’s weighting function.

Replacing by (16c), the latter can be rewritten as

where we can see that the variance associated with a contaminated measurement is proportional to the square of the normalized residual. In other words, the larger the outlier is, the larger is the associated variance, which in turn implies a direct downweight within the EKF through the Kalman gain. Therefore, with a minor EKF modification, the filter is able to use the robust weight as an outlier uncertainty indicator, which at the end does not impact the augmented-state EKF behavior to correctly deal with model mismatch. This new robust covariance weighting method is subsequently denoted MRCEKF.

7. Conclusions and Outlook

In this contribution, we derived two new robust filtering techniques able to deal with both model mismatch (i.e., transmitters’ position uncertainty) and harsh propagation conditions (i.e., measurements corrupted by outliers). Such methodologies rely on an augmented state, which includes the uncertain anchors’ position, and tools arising from robust statistics. It was also shown that standard techniques suffer from a non-negligible performance loss if mismatch and outliers are not properly taken into consideration; therefore, the new methodologies are promising solutions for real-life safety-critical applications. The first methodology is based on the standard robust regression M-estimation EKF, with the penalty of needing an iterative procedure within every KF step, which may not be a good option for very low cost platforms. The second methodology focused on the latter, to reduce the computational complexity, by leveraging a robust weighting function to adapt the measurement noise statistics. Overall, both methods provide a significant performance improvement under several configurations with respect to the state-of-the-art.

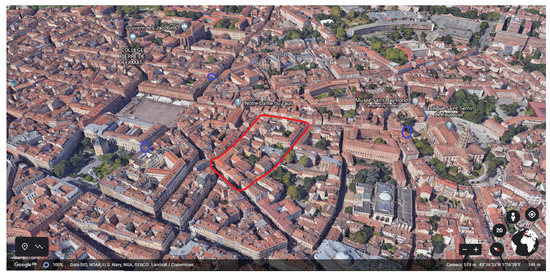

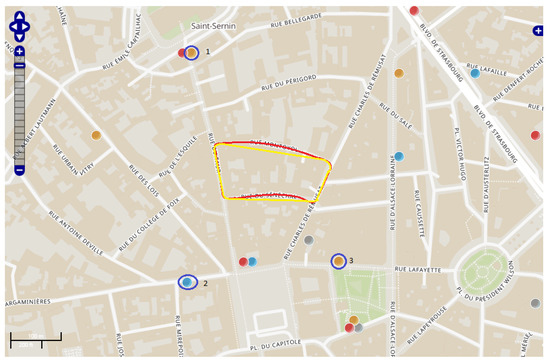

Note that the vehicle model used in this contribution is a low-speed ground vehicle, which could correspond to a car moving through small and narrow streets in a city center. Notice that the algorithms operate in a 3D state-space, so they are also valid for low-speed aerial vehicles such as drones. High-speed vehicles are out of the scope of the contribution, and indeed, even if the KFs can also be used in this case in such environments, they are not likely to have strong outliers (open-sky environments or rural areas). Therefore, even if the new filtering approaches are valid for any type of vehicle, dynamics, and propagation conditions, their clear benefit is in situations where GNSS is not available and the propagation conditions are severe. Notice that the focus of this contribution was on GNSS-denied harsh environments such as indoors and deep urban canyons, but the new methodologies proposed in the article can also be applied in the context of GNSS and multisensor data fusion (where other types of mismatch may arise), setting the basis for a robust multisensor navigation framework to be further explored.

Another issue worth mentioning is time synchronization. First, notice that the standard way to exploit UWB for positioning is through a two-way ranging protocol within the UWB network. This avoids the need to synchronize the UWB Tx/Rx. In addition, there are several ways to synchronize or time-stamp LTE measurements together with UWB measurements, for instance, using the NTP networking protocol for clock synchronization. One could also imagine that a GNSS receiver is also available but not used for positioning due to its very degraded performance. Notice that even in very harsh propagation conditions, a GNSS receiver provides a clock synchronization in the order of 100 ns, which is more than enough to avoid worrying about the LTE data synchronization. Therefore, the proposed approach without taking into account the LTE clock errors is valid to statistically characterize the new filtering methods, which are intended to deal with model mismatch and outliers.

As a short-term perspective, these techniques must be assessed with real-data experiments, which is currently under study because other problems related to the hardware and the specific platform appear. In the long-term, such techniques could be embedded in a complete GNSS/UWB/LTE/IMU/Lidar/Vision platform to deal with a full set of heterogeneous measurements and model mismatches.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.P. and J.V.-V.; methodology, G.P. and J.V.-V.; software, J.M. and G.P.; validation, J.M., G.P., and J.V.-V.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M., G.P., and J.V.-V.; writing—review and editing, J.M., G.P., and J.V.-V.; funding acquisition, G.P. and J.V.-V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the DGA/AID (French Secretary Of Defense) projects (2019.65.0068.00.470.75.01, 2018.60.0072.00.470.75.01).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Amin, M.G.; Closas, P.; Broumandan, A.; Volakis, J.L. Vulnerabilities, threats, and authentication in satellite-based navigation systems [scanning the issue]. Proc. IEEE 2016, 104, 1169–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, D.; Li, H.; Vilà-Valls, J.; Closas, P. Robust Statistics for GNSS Positioning under Harsh Conditions: A Useful Tool? Sensors 2019, 19, 5402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teunissen, P.J.G.; Montenbruck, O. (Eds.) Handbook of Global Navigation Satellite Systems; Springer: Basel, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Del Peral-Rosado, J.A.; Raulefs, R.; Lopez-Salcedo, J.A.; Seco-Granados, G. Survey of Cellular Mobile Radio Localization Methods: From 1G to 5G. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2018, 20, 1124–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dardari, D.; Closas, P.; Djuric, P. Indoor tracking: Theory, Methods, and Technologies. IEEE Trans. Veh. Tech. 2015, 64, 1263–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, P.D. Principles of GNSS, Inertial, and Multisensor Integrated Navigation Systems, 2nd ed.; Artech House: Norwood, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Cai, B.G.; Wang, J. Cooperative Localization of Connected Vehicles: Integrating GNSS with DSRC Using a Robust Cubature Kalman Filter. IEEE Trans. Intel. Transp. Syst. 2017, 18, 2111–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Gao, J.; Zhang, H.; Qiu, T.Z. RSE-assisted lane-level positioning method for a connected vehicle environment. IEEE Trans. Intel. Transp. Syst. 2019, 20, 2644–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Kato, N. Networking and communications in autonomous driving: A survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2019, 21, 1243–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetrella, A.R.; Opromolla, R.; Fasano, G.; Accardo, D.; Grassi, M. Autonomous Flight in GPS-Challenging Environments Exploiting Multi-UAV Cooperation and Vision-aided Navigation. In Proceedings of the AIAA Information Systems-AIAA Infotech @ Aerospace, Grapevine, TX, USA, 9–13 January 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, M.; Steffens, M.; Mavris, D.N. Evaluating the Performance Impact of Cooperative Navigation for Unmanned Aerial Systems in GPS-Denied Environments. In Proceedings of the 2018 Modeling and Simulation Technologies Conference, Atlanta, Georgia, 8–12 January 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kassas, Z.; Khalife, J.; Shamaei, K.; Morales, J. I hear, therefore I know where I am: Compensating for GNSS limitations with cellular signals. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2017, 34, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamaei, K.; Khalife, J.; Kassas, Z. Exploiting LTE signals for navigation: Theory to implementation. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2018, 17, 2173–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Peral-Rosado, J.A.; Lopez-Salcedo, J.A.; Zanier, F.; Seco-Granados, G. Position Accuracy of Joint Time-Delay and Channel Estimators in LTE Networks. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 25185–25199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Peral-Rosado, J.A.; Seco-Granados, G.; Kim, S.; Lopez-Salcedo, J.A. Network Design for Accurate Vehicle Localization. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2019, 68, 4316–4327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maaref, M.; Khalife, J.; Kassas, Z. Lane-level Localization and Mapping in GNSS-challenged Environments by Fusing Lidar Data and Cellular Pseudoranges. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2019, 4, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassas, Z.; Maaref, M.; Morales, J.; Khalife, J.; Shamaei, K. Robust vehicular navigation and map-matching in urban environments with IMU, GNSS, and cellular signals. IEEE Intell. Transp. Syst. Mag. 2020, 12, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dardari, D.; Conti, A.; Ferner, U.; Giorgetti, A.; Win, M.Z. Ranging with ultrawide bandwidth signals in multipath environments. Proc. IEEE 2009, 97, 404–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, A.R.; Seco, F. Comparing Decawave and Bespoon UWB Location Systems: Indoor/Outdoor Performance Analysis. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Indoor Positioning and Indoor Navigation (IPIN), Sapporo, Japan, 18–21 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tiemann, J.; Schweikowski, F.; Wietfeld, C. Design of an UWB Indoor-Positioning System for UAV Navigation in GNSS-Denied Environments. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Indoor Positioning and Indoor Navigation (IPIN), Banff, AB, Canada, 7 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tiemann, J.; Pillmann, J.; Boecker, S.; Wietfeld, C. Ultra-Wideband Aided Precision Parking for Wireless Power Transfer to Electric Vehicles in Real Life Scenarios. In Proceedings of the IEEE Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC-Fall), Montréal, QB, Canada, 18–21 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzyk, M.M.; Grun, T.V.D. Experimental Validation of a TOA UWB Ranging Platform with the Energy Detection Receiver. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Indoor Positioning and Indoor Navigation (IPIN), Zurich, Switzerland, 15–17 September 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cetin, O. An Experimental Study of High Precision TOA based UWB Positioning Systems. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Ultra-Wideband (ICUWB), Syracuse, NY, USA, 17–20 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pagès, G.; Vilà-Valls, J. UWB-based Indoor Navigation with Uncertain Anchor Nodes Positioning. In Proceedings of the ION GNSS+, Miami, FL, USA, 16–20 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cebrian, A.; Bellés, A.; Martin, C.; Salas, A.; Fernández, J.; Arribas, J.; Vilà-Valls, J.; Navarro, M. Low-Cost Hybrid GNSS/UWB/INS Integration for Seamless Indoor/Outdoor UAV Navigation. In Proceedings of the ION GNSS+, Miami, FL, USA, 16–20 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zoubir, A.M.; Koivunen, V.; Ollila, E.; Muma, M. Robust Statistics for Signal Processing; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vilà-Valls, J.; Closas, P. NLOS Mitigation in Indoor Localization by Marginalized Monte Carlo Gaussian Smoothing. EURASIP J. Adv. Signal Process. 2017, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilà-Valls, J.; Vincent, F.; Closas, P. Decentralized Information Filtering under Skew-Laplace Noise. In Proceedings of the 2019 53rd Asilomar Conference on Signals, Systems, and Computers, Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 29 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, B.; Moore, J.B. Optimal Filtering; Prentice–Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Chaumette, E. Minimum Variance Distortionless Response Estimators For Linear Discrete State-Space Models. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2017, 64, 2048–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).