Abstract

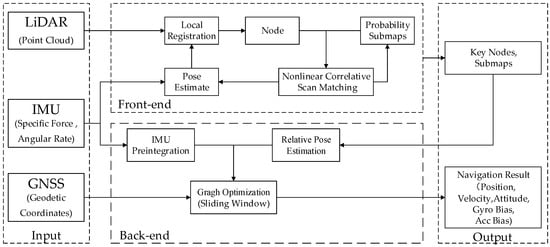

A Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS)/Inertial Navigation System (INS)/Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR)-Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) integrated navigation system based on graph optimization is proposed and implemented in this paper. The navigation results are obtained by the information fusion of the GNSS position, Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) preintegration result and the relative pose from the 3D probability map matching with graph optimizing. The sliding window method was adopted to ensure that the computational load of the graph optimization does not increase with time. Land vehicle tests were conducted, and the results show that the proposed GNSS/INS/LiDAR-SLAM integrated navigation system can effectively improve the navigation positioning accuracy compared to GNSS/INS and other current GNSS/INS/LiDAR methods. During the simulation of one-minute periods of GNSS outages, compared to the GNSS/INS integrated navigation system, the root mean square (RMS) of the position errors in the North and East directions of the proposed navigation system are reduced by approximately 82.2% and 79.6%, respectively, and the position error in the vertical direction and attitude errors are equivalent. Compared to the benchmark method of GNSS/INS/LiDAR-Google Cartographer, the RMS of the position errors in the North, East and vertical directions decrease by approximately 66.2%, 63.1% and 75.1%, respectively, and the RMS of the roll, pitch and yaw errors are reduced by approximately 89.5%, 92.9% and 88.5%, respectively. Furthermore, the relative position error during the GNSS outage periods is reduced to 0.26% of the travel distance for the proposed method. Therefore, the GNSS/INS/LiDAR-SLAM integrated navigation system proposed in this paper can effectively fuse the information of GNSS, IMU and LiDAR and can significantly mitigate the navigation error, especially for cases of GNSS signal attenuation or interruption.

1. Introduction

With the rapid development of autonomous driving and intelligent robots, the demand for navigation information with high data rates, high precision and all-weather features continues to increase, especially in complex urban environments. Thus, a single navigation technique can hardly meet the requirements for practical applications, and the synthesis of multiple navigation techniques has become the development trend in navigation. Among the various synthesized navigation techniques, the Global Navigation Satellite System/Inertial Navigation System (GNSS/INS) integrated navigation system, which is dominated by the INS and supplemented by the GNSS, is the most popular. The characteristics of the GNSS and the INS are distinctively complementary: (1) generally, information from GNSS and INS are effectively integrated via Kalman filtering [1]; and (2) INS largely compensates for the shortcoming of GNSS, which is vulnerable to interference, while GNSS provides the periodic correction information for INS; hence, the synergy of the two techniques improves the navigation performance. However, in areas where the GNSS signal is not available, the GNSS/INS integrated navigation system relies on the performance of INS alone and experiences drifting errors. In addition, for the low-cost MEMS (Micro-Electro-Mechanical System)-Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU), the navigation errors will accumulate and increase rapidly over time. In the context of low-cost integrated systems, image-based methodologies have also been explored, aiming at investigating the impact of drifts and errors experienced with such techniques, like in [2,3]. In the field of computer vision and robotics, Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) technology is widely used for navigation in unfamiliar environments. The SLAM system locates itself mainly according to position estimation and a map during movement and builds up incremental maps based on the self-localization to achieve independent positioning and navigation [4]. In recent years many excellent SLAM systems based on a single sensor have been developed, such as LG-SLAM [5], IMLS-SLAM [6], SUMA [7] and LOAM [8]. VINS [9] uses a tightly coupled, nonlinear optimization-based method to obtain highly accurate visual-inertial odometry by fusing preintegrated IMU measurements and feature observations. vLOAM [10] presents a general framework for combining camera and Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR). However, the errors of these SLAM systems, which are reduced mainly by the closed-loop correction method, will also increase with the moving distance. In large-scale outdoor motion, SLAM is less likely to form a closed-loop. Additionally, SLAM cannot provide absolute navigation information. Therefore, the combination of the GNSS/INS integrated navigation system and SLAM will effectively mitigate the navigation drift when the GNSS signal is not available, reduce the dependence of SLAM on closed-loop correction and provide absolute navigation information to fulfill the complementary advantages of the three techniques.

Generally, cameras and LiDAR are the two most common sensors for SLAM, and each of the two types of sensors has strengths and weaknesses. Compared to the camera, LiDAR, despite a higher cost and lower resolution, can directly obtain the structure information of environments and is hardly influenced by light or weather. Therefore, in this paper, mechanical rotating LiDAR is adopted.

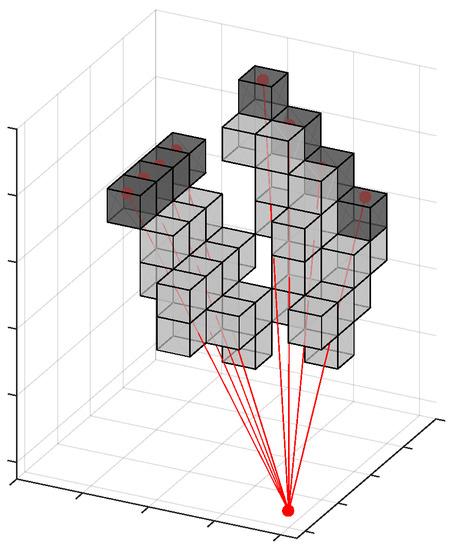

In order to estimate pose change from LiDAR measurements, there are about three different categories of scan matching method: feature-based scan matching, point-based scan matching and mathematical property-based scan matching [11]. The feature-based scan matching is matching with some key elements which can be geometric primitives such as points, lines, and polygons, or a combination thereof in the LiDAR data. The point-based scan matching directly searches and matches the corresponding points in the LiDAR data. The Iterative Closest Point (ICP) algorithm and its variants [12,13] are the most popular methods to solve the point-based scan matching problem. The mathematical property-based scan matching can use various mathematical properties, such as the Normal Distribution Transform (NDT) [14] or the probability grid [15] to depict scan data changes. The feature-based scan matching method is efficient and accurate. But, it relies on features extracted from the environment. It may fail to work properly in outdoor or indoor unconstructed environments. The point-based scan matching method is accurate and independent of environment features. But, it takes a long time because of the inevitable iteration [16]. Thereby in this paper, the probability grid scan matching is used for the point cloud matching in the outdoor environment.

For data fusion in SLAM, there are mainly two methods: filtering and graph optimization. The former is better than the latter in terms of calculation speed but inferior in accuracy [17]. Qian [18] and Gao [16] used the EKF (extended Kalman filter) to perform a combination of GNSS, INS and LiDAR-SLAM. Shamsudin [19] used particle filtering to combine GNSS with LiDAR-SLAM. There has been increasing research on graph optimization in recent years. Kukko [20] used the graph optimization method to combine the results of the GNSS/INS with a single-line LiDAR. Hess [15] implemented 2D-LiDAR navigation based on graph optimization. Pierzchała [21] used graph optimized 3D LiDAR-SLAM for woods construction. Cartographer [22] completed a fusion of GNSS, 3D-LiDAR and IMU based on graph optimization. However, it was assumed that the vehicle was moving at a low speed and moved smoothly. Therefore, gravity is used to solve the horizontal attitude (i.e., roll and pitch), and error modelling for the IMU bias was ignored; the estimation of the vehicle’s velocity was also ignored.

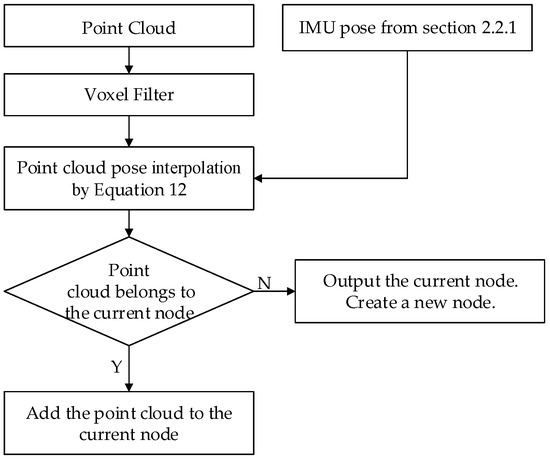

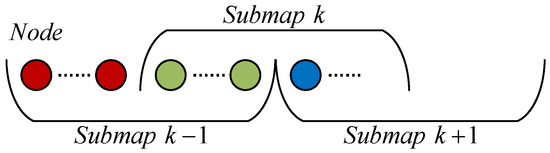

Considering the limitations of Cartographer and based on the Cartographer codes, a GNSS/INS/LiDAR-SLAM integrated navigation system is implemented in this paper based on graph optimization. First, the MEMS-IMU mechanization is applied to predict the motion of the vehicle and provide the searching initial value for probability map scan matching with LiDAR in the front-end. In the back-end, the GNSS position provides the absolute position constraint, while the IMU preintegration [9,23] is applied to increase the motion constraints, and the LiDAR-SLAM scan matching provides the relative pose constraints. Then, three information sources are combined by graph optimization to obtain the final navigation positioning results. In addition, to keep the parameters of the graph optimization invariant with time, a sliding window is applied to ensure the relative stability of the graph optimization parameter number.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, the mathematical model of the GNSS/INS/LiDAR-SLAM integrated navigation system is described. In Section 3, the land vehicle tests are introduced. The experimental results are discussed in Section 4. Finally, in Section 5, conclusions and future prospects are presented.

3. Experiment

To verify the performance of the proposed GNSS/INS/LiDAR-SLAM integrated navigation system, land vehicle tests were conducted in Wuhan on September 7, 2018. In addition to VLP16 and the tested system (NV-POS1100), the vehicle was equipped with a higher precision inertial integrated navigation system (LD-A15) as the reference system in the tests, as shown in Figure 5. Table 1 gives the technical parameters of the two systems. The sampling rate of GNSS was 1 Hz, the sampling rate of LiDAR was 600 RPM, and the sampling rate of IMU was 200 Hz. All the test data has been shared on OneDrive (https://whueducn-my.sharepoint.com/:f:/g/personal/changlesgg_whu_edu_cn/EsN45ma2spBMmC37pafR3Q0BdeMuD_hb1uBc3gsQERu-uw?e=KOwhwe).

Figure 5.

Experimental platform.

Table 1.

Technical Parameters of LD-A15 and NV-POS1100.

In the case of continuous GNSS position correction, the GNSS/INS integrated navigation system carries out observational updates with the GNSS position. The navigation accuracy, especially the position accuracy, is mainly determined by the GNSS positioning accuracy. Therefore, the accuracy assessment of the GNSS/INS integrated navigation system is achieved by investigating the navigation error during GNSS signal interruption. In this paper, the accuracy of the GNSS, IMU, and LiDAR-SLAM integrated navigation system was evaluated in the same way.

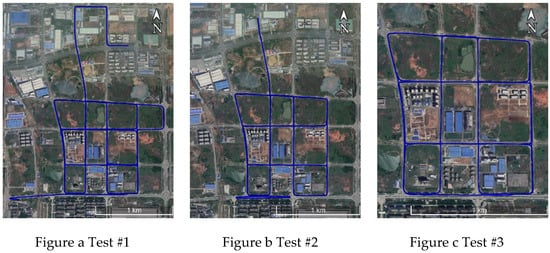

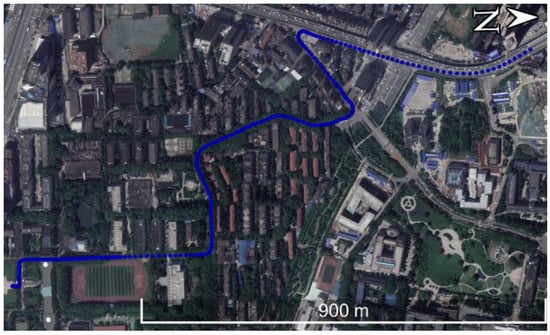

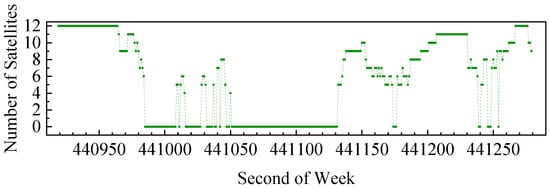

Three tests (approximately one hour for each test) were carried out in an open-sky environment, and one test was conducted in urban areas. The test trajectories are shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7. The reference system (LD-A15) data were processed with the PPK (Post Processed Kinematic)/INS smoothing integration method. The results were converted to the center of the tested system (NV-POS1100) as the reference value of its position and attitude. Then, one minute of GNSS outage every six minutes was intentionally introduced into the PPK results of the reference system to simulate the GNSS signal interruption (all satellites’ signals were lost and recovered at the same time). Thereafter, the GNSS/INS/LiDAR-SLAM integrated method described above was performed with the PPK result involving GNSS outages, the tested system data and the VLP16 data. For the purpose of comparison, the GNSS/INS integration method and the Cartographer’s GNSS/LiDAR/IMU integrated navigation method were also conducted. Then, the navigation errors of the three methods during the GNSS outage were compared. Finally, the same comparative analysis was carried out with the data collected in urban areas, where signal attenuation and outage occur frequently, as shown in Figure 8. The performances of the three methods can be compared by checking the positioning drifts in the real GNSS signal outages and attenuations.

Figure 6.

Test trajectory in the open-sky environment.

Figure 7.

Test trajectory in the urban area.

Figure 8.

Number of satellites in the urban area.

4. Results and Discussion

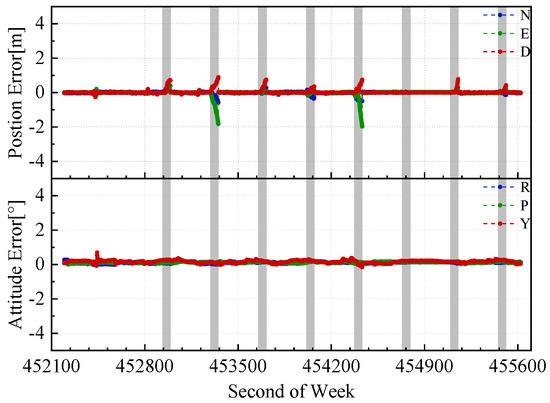

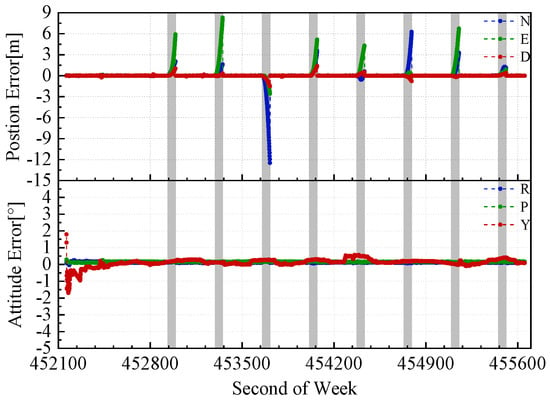

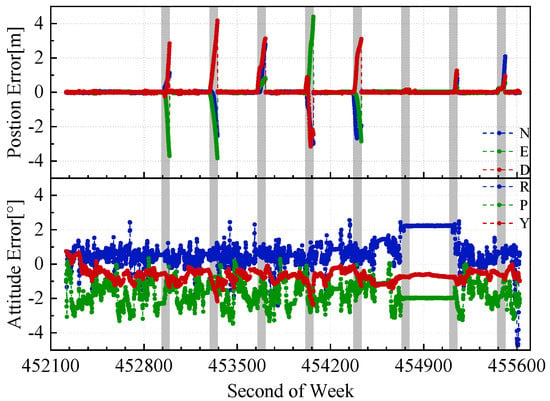

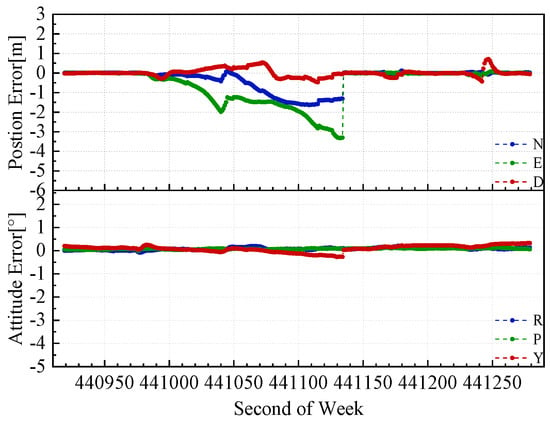

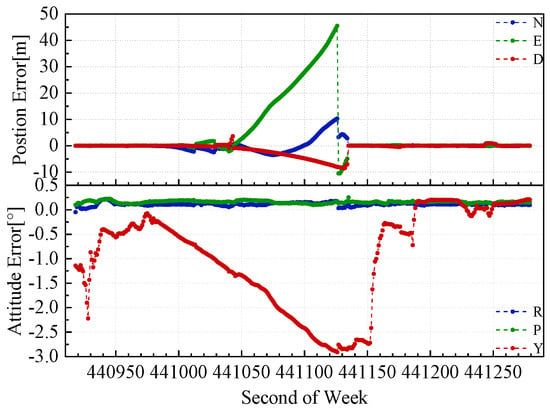

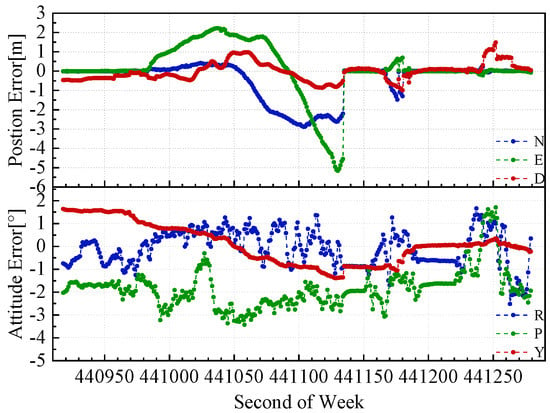

The position and attitude errors of the three methods with the one minute’s GNSS outage simulation test #2 are shown in Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11. The grey span in the figures marks the periods of simulating the GNSS outages. Based on the position and attitude errors in the GNSS outages, the following can be observed:

Figure 9.

Position and attitude errors of the GNSS/INS/LiDAR-SLAM integrated navigation system in the GNSS outage simulation test #2.

Figure 10.

Position and attitude errors of the GNSS/INS integrated navigation system in the GNSS outage simulation test #2.

Figure 11.

Position and attitude errors of Cartographer in the GNSS outage simulation test #2.

- (1).

- For the horizontal position error (i.e., in the North and East directions), the proposed GNSS/INS/LiDAR-SLAM integrated navigation system was the smallest, and the GNSS/INS integrated navigation system was the largest. The vertical position error of the proposed GNSS/INS/LiDAR-SLAM integrated navigation system was similar to the GNSS/INS integrated navigation system, and Cartographer had the largest vertical position error. In the sixth outage when the vehicle was at rest, the Cartographer and GNSS/INS/LiDAR-SLAM integrated navigation system significantly reduced the horizontal positioning drift with the aid of the LiDAR-SLAM compared to the GNSS/INS integrated navigation system.

- (2).

- Cartographer had the largest attitude error, especially in the roll and pitch, which is because Cartographer assumes low dynamic motion of the vehicle and uses gravity to solve the horizontal attitude (similar to the inclinometer principle). The attitude error of the proposed GNSS/INS/LiDAR-SLAM integrated navigation system was equivalent to that of the GNSS/INS integrated navigation system.

In the three open-sky tests, a total of 26 GNSS outages were simulated. Based on the error statistics in Table 2, the following information can be obtained by comparison with the GNSS/INS integrated navigation system:

Table 2.

Errors statistics for the GNSS outage simulation tests.

- (a)

- The position error RMS in the North, East and vertical directions of the proposed GNSS/INS/LiDAR-SLAM navigation system was reduced by 82.2%, 79.6%, and 17.2%, respectively. The Cartographer’s North and East position error RMS was reduced by 47.4% and 44.8%, respectively, but the vertical position error RMS is degraded by 2.3 times.

- (b)

- The aid of the LiDAR-SLAM did not significantly improve the attitude accuracy in the GNSS/INS/LiDAR-SLAM integrated navigation system. The RMS values of the Cartographer’s roll, pitch and yaw errors were increased by 9.5, 13.7, and 7.2 times, respectively, because of the dedicated algorithm design for low speed and smooth motion, which does not fit the test cases in this paper.

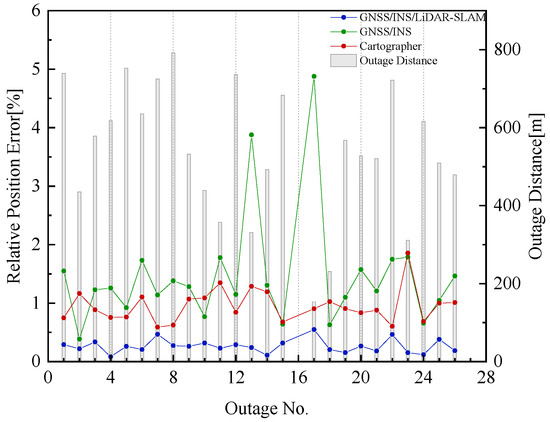

The relative position errors (i.e., percentage of position error over travel distance) in the GNSS outages are shown in Figure 12. The left y axis corresponding to the dotted lines in the figure is the relative position error of the three methods, and the right y axis corresponding to the strip is the travel distance in the GNSS outage. In the 16th outage (that is, the sixth outage in test #2, as shown in Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11), the vehicle was at rest, and the relative position error was not calculated. The average relative position errors of the GNSS/INS/LiDAR-SLAM integrated navigation system, GNSS/INS integrated navigation system and Cartographer were 0.26%, 1.46%, and 0.92% of the travel distance, respectively. The aid of LiDAR-SLAM effectively reduces the relative position error in the GNSS outages.

Figure 12.

Relative position errors in the GNSS outage simulation tests.

Based on the GNSS outage simulation tests, the aid of LiDAR-SLAM can effectively reduce the position accuracy when the GNSS is unavailable. The horizontal position accuracy of the GNSS/INS/LiDAR-SLAM integrated navigation system and Cartographer was better than that of the GNSS/INS integrated navigation system. However, the Cartographer’s height and attitude error was greater than that of the GNSS/INS integrated navigation system. The reason is that Cartographer assumes that the vehicle moves at a low speed with a small acceleration; therefore, gravity is used to estimate the horizontal attitude, and the modelling for the bias of the IMU is ignored. Thus, during the tests in this paper, the horizontal attitude error and the vertical position error of Cartographer were relatively large.

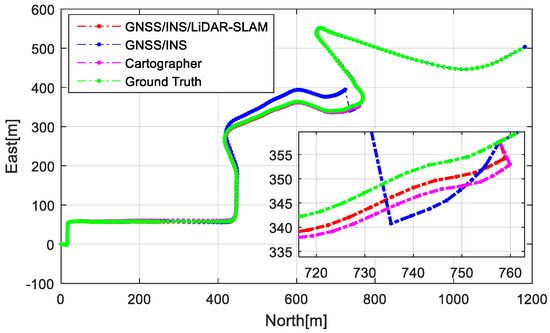

In addition to the open-sky tests with simulated GNSS outage results, the trajectories of the three methods and the reference truth in the urban area test are shown in Figure 13. According to Figure 8, there were approximately 150 s of poor satellite signals in the test, and the GNSS positioning quality is generally unstable. The position and attitude errors are shown in Figure 14, Figure 15 and Figure 16, and the statistics for these errors are shown in Table 3. Similar to the three GNSS outage simulation tests, the GNSS/INS/LiDAR-SLAM integrated navigation system had the best positional accuracy. Because of the poor quality of GNSS positioning for a long time, the GNSS/INS integrated navigation system had a large yaw drift error in addition to the large position error compared to the GNSS/INS/LiDAR-SLAM integrated navigation system and Cartographer. Therefore, the aid of LiDAR-SLAM can also improve the yaw accuracy for very tough scenarios.

Figure 13.

Trajectories in the urban area test.

Figure 14.

Position and attitude errors of the GNSS/INS/LiDAR-SLAM integrated navigation system in the urban area test.

Figure 15.

Position and attitude errors of the GNSS/INS integrated navigation system in the urban area test.

Figure 16.

Position and attitude errors of Cartographer in the urban area test.

Table 3.

Error statistics for the urban area test.

A solution of GNSS/LiDAR/INS navigation is demonstrated in this paper and verified by the real-world tests. There are not too much complicated theoretical conclusions, such as the observability, which should be validated by controllable simulation data have been proposed in this paper. And because in the simple and controllable simulated environment, error models and parameters are clear, the algorithms always get a good result than in real scenarios and it’s not persuasive. Consequently, to indicate the performance of this solution, the data collected in real-world scenarios is convincing and this is the only data source in this paper. In addition, the system in this paper requires the raw LiDRA data, which is not easy to simulate.

The results of the four vehicle tests (three open-sky and one urban street) have shown that the position and attitude accuracy of the proposed GNSS/INS/LiDAR-SLAM integrated navigation system is the best, especially in a weak or blocked GNSS signal environment. Cartographer has the largest roll, pitch and elevation errors because the motion model of the algorithm is only suitable for low-speed motion. Due to the lack of aiding information, the GNSS/INS integrated navigation system gradually degrades the position and attitude when GNSS is not available, and LiDAR-SLAM assistance can play a significant role in maintaining navigation accuracy.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, a GNSS/INS/LiDAR-SLAM integrated navigation system is proposed. The MEMS-IMU mechanization is applied for pose estimation. Through graph optimization, the GNSS position, IMU preintegration results and the relative pose obtained from LiDAR scan matching are fused. In addition, the use of a sliding window ensures that the computational load of the graph optimization does not increase with time. The vehicle tests show that the GNSS/INS/LiDAR-SLAM integrated navigation system can effectively reduce the position errors in the horizontal directions during the GNSS outage periods compared with the GNSS/INS integrated navigation system. For the position error in the vertical direction and the attitude error, the two systems perform similarly. In addition, compared with the benchmark method of GNSS/INS/LiDAR-Google Cartographer, the use of the IMU information in the proposed algorithm is more reasonable and sufficient, thus improving both the position and attitude accuracies. Finally, the relative position error of the proposed GNSS/INS/LiDAR-SLAM method during the GNSS outage was reduced from 1.46% (GNSS/INS) to 0.92% (Cartographer) to 0.26% of the travel distance.

For future works, the GNSS/INS/LiDAR integrated navigation system in this paper cannot yet eliminate the dynamic objects from the environment. Therefore, it is necessary to add the recognition and elimination mechanism of dynamic objects in the environment. Furthermore, a procreated background map may be added to improve the robustness and navigation positioning accuracy of the integrated navigation system, such as for applications for autodrive and mobile robots.

Author Contributions

L.C. and X.N. conceived and designed the experiments, wrote the paper, and performed the experiments; T.L. performed the land vehicle tests and provided the LiDAR, IMU, and GNSS raw data; and J.T. and C.Q. reviewed the paper and gave constructive advice.

Funding

This research was funded by the “National Key Research and Development Program” (No. 2016YFB0501803 and No. 2016YFB0502202) and the “Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities” (No. 2042018KF0242).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Shin, E.-H. Estimation Techniques for Low-Cost Inertial Navigation; The University of Calgary: Calgary, Canada, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pagliaria, D.; Pinto, L.; Reguzzoni, M.; Rossi, L. Integration of kinect and low-cost gnss for outdoor navigation. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2016, XLI-B5, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, L.; De Gaetani, C.; Pagliari, D.; Realini, E.; Reguzzoni, M.; Pinto, L. Comparison between rgb and rgb-d cameras for supporting low-cost gnss urban navigation. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2018, 42, 991–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadena, C.; Carlone, L.; Carrillo, H.; Latif, Y.; Scaramuzza, D.; Neira, J.; Reid, I.; Leonard, J.J. Past, Present, and Future of Simultaneous Localization and Mapping: Toward the Robust-Perception Age. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2016, 32, 1309–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, M.R.; Eustice, R.M.; Leonard, J.J. Exactly Sparse Extended Information Filters for Feature-based SLAM. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2007, 26, 335–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschaud, J.-E. IMLS-SLAM: Scan-to-model matching based on 3D data. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA2018), Brisbane, QL, Australia, 21–25 May 2018; pp. 2480–2485. [Google Scholar]

- Behley, J.; Stachniss, C. Efficient Surfel-based Slam Using 3d Laser Range Data in Urban Environments. Available online: http://roboticsproceedings.org/rss14/p16.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2019).

- Zhang, J.; Singh, S. LOAM: Lidar Odometry and Mapping in Real-time. In Proceedings of the Robotics: Science and Systems, Berkeley, CA, USA, 14–16 July 2014; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, T.; Li, P.; Shen, S. VINS-Mono: A Robust and Versatile Monocular Visual-Inertial State Estimator. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2018, 34, 1004–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Singh, S. Visual-lidar odometry and mapping: Low-drift, robust, and fast. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA2015), Seattle, WA, USA, 26–30 May 2015; pp. 2174–2181. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, J.L.; González, J.; Morales, J.; Mandow, A.; García-Cerezo, A.J. Mobile robot motion estimation by 2D scan matching with genetic and iterative closest point algorithms. J. Field Robot. 2006, 23, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Censi, A. An ICP variant using a point-to-line metric. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Pasadena, CA, USA, 19–23 May 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Aleksandr, S.; Haehnel, D.; Thrun, S. Generalized-ICP. In Proceedings of the Robotics: Science and Systems, Seattle, WA, USA, 28 June–1 July 2009; p. 435. [Google Scholar]

- Burguera, A.; González, Y.; Oliver, G. On the use of likelihood fields to perform sonar scan matching localization. Auton. Robot. 2009, 26, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, W.; Kohler, D.; Rapp, H.; Andor, D. Real-time loop closure in 2D LIDAR SLAM. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Stockholm, Sweden, 16–21 May 2016; pp. 1271–1278. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Liu, S.; Atia, M.M.; Noureldin, A. INS/GPS/LiDAR Integrated Navigation System for Urban and Indoor Environments Using Hybrid Scan Matching Algorithm. Sensors 2015, 15, 23286–23302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durrant-Whyte, H.; Bailey, T. Simultaneous localization and mapping: Part I. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2006, 13, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, C.; Liu, H.; Tang, J.; Chen, Y.; Kaartinen, H.; Kukko, A.; Zhu, L.; Liang, X.; Chen, L.; Hyyppä, J. An integrated GNSS/INS/LiDAR-SLAM positioning method for highly accurate forest stem mapping. Remote Sens. 2016, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsudin, A.U.; Ohno, K.; Hamada, R.; Kojima, S.; Westfechtel, T.; Suzuki, T.; Okada, Y.; Tadokoro, S.; Fujita, J.; Amano, H. Consistent map building in petrochemical complexes for firefighter robots using SLAM based on GPS and LIDAR. Robomech. J. 2018, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukko, A.; Kaijaluoto, R.; Kaartinen, H.; Lehtola, V.V.; Jaakkola, A.; Hyyppä, J. Graph SLAM correction for single scanner MLS forest data under boreal forest canopy. Isprs J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2017, 132, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierzchała, M.; Giguère, P.; Astrup, R. Mapping forests using an unmanned ground vehicle with 3D LiDAR and graph-SLAM. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 145, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartographer. Latest. Available online: https://google-cartographer.readthedocs.io/en/latest/ (accessed on 9 July 2018).

- Forster, C.; Carlone, L.; Dellaert, F.; Scaramuzza, D. On-Manifold Preintegration for Real-Time Visual--Inertial Odometry. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2015, 33, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahao, C. Algorithm Implementation of Pseudorange Differential BDS/INS Tightly-Coupled Integration and GNSS Data Quality Control Analysis; Wuhan University: Wuhan, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jun, W.; Gongmin, Y. Strapdown Inertial Navigation Algorithm and Integrated Navigation Principles; Northwestern Polytechnical University Press Co. Ltd.: Xi’an, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dehai, Z. Point Cloud Library PCL Learning Tutorial; Beihang University Press: Beijing, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Slerp. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slerp (accessed on 2 October 2018).

- Olson, E.B. Real-time correlative scan matching. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Kobe, Japan, 12–17 May 2009; pp. 1233–1239. [Google Scholar]

- Ceres Solver, 1.14. Available online: http://ceres-solver.org (accessed on 23 March 2018).

- Lekien, F.; Marsden, J.E. Tricubic Interpolation in Three Dimensions. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 2010, 63, 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausen, J. Branch and Bound Algorithms—Principles and Examples. Parallel Process. Lett. 1999, 22, 658–663. [Google Scholar]

- Xiangyuan, K.; Jiming, G.; Zongquan, L. Foundation of Geodesy, 2nd ed.; Wuhan University Press: Wuhan, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sola, J. Quaternion kinematics for the error-state Kalman filter. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.02508. [Google Scholar]

- Yongyuan, Q. Kalman Filter and Integrated Navigation Principle; Northwestern Polytechnical University Press Co. Ltd.: Xi’an, China, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sibley, G.; Matthies, L.; Sukhatme, G. Sliding window filter with application to planetary landing. J. Field Robot. 2010, 27, 587–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F. The Schur Complement and Its Applications; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Eckenhoff, K.; Paull, L.; Huang, G. Decoupled, consistent node removal and edge sparsification for graph-based SLAM. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Daejeon, Korea, 9–14 October 2016; pp. 3275–3282. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).