Abstract

Geomechanical assessment of rocks requires knowledge of phenomena that occur under the influence of internal and external factors at a macroscopic or microscopic scale, when rocks are submitted to different actions. To elucidate the quantitative and qualitative geomechanical behavior of rocks, knowing their geological and physical–mechanical characteristics becomes an imperative. Mineralogical, petrographical and chemical analyses provided an opportunity to identify 15 types of igneous rocks (gabbro, diabases, granites, diorites, rhyolites, andesites, and basalts), divided into plutonic and volcanic rocks. In turn, these have been grouped into acidic, neutral (intermediate) and basic magmatites. A new ranking method is proposed, based on considering the rock characteristics as indicators of quantitative assessment, and the grading system, by given points, allowing the rocks framing in admissibility classes. The paper is structured into two parts, experimental and interpretation of experimental data, showing the methodology to assess the quality of igneous rocks analyzed, and the results of theoretical and experimental research carried out on the analyzed rock types. The proposed method constitutes an appropriate instrument for assessment and verification of the requirements regarding the quality of rocks used for sustainable construction.

1. Introduction

Since the dawn of civilization, rocks have been used for construction purposes. In time, the use of rocks under a variety of forms became increasingly complex, as a reflection of cultural and historical trends of the human society [1,2].

On the Romanian territory, the natural occurrence of useful rocks is widely spread on the foreland zone and on the Carpathian structures. These rocks have multiple uses in constructions and various other civil/industrial sectors. Besides being used as raw material in buildings, roads and a variety of miscellaneous engineering works, depending on their petrographic type, these useful rocks are also used for ornamental/decorative purposes [2,3,4].

Given their wide spectrum of utilizations, the interest for mapping new reserves and prospective areas of useful rocks becomes crucial. This interest is enhanced by the rapid development of the construction industry, with special emphasis on terrestrial transportation infrastructures [5,6]. To acquire the desired construction quality of the terrestrial transportation infrastructures, a thorough understanding of the used materials and their behavior under heavy traffic and weathering factors is required.

The construction, rehabilitation and maintenance of road infrastructures involve the utilization of significant quantities of natural materials, where the natural aggregates play the most important role. Advanced construction technologies together with the quality of rocks, natural aggregates and other road construction materials, drive the achievement of well-built terrestrial transportation infrastructures. In the particular case of aggregates, the diversity of the raw material as a source, the various capabilities of manufacturing facilities, and the market demand present a wide diversity, with direct repercussion on the quality of the aggregates.

Accordingly, the rigorous characterization of the original aggregate quality becomes a paramount aspect in building reliable terrestrial transportation infrastructures. Additionally, based on the variation of raw material and manufacturing facilities, the aggregate characterization becomes a necessary periodic, reiterative step, aimed to bridge the construction needs and the available material. The adequate utilization of each type of aggregate is dictated by the chemical, mineralogical–petrographical and physical–mechanical properties of the source rock.

The periodic analysis of the source rocks and aggregates is managed through specific standards that stipulate threshold values of the physical and mechanical properties specific for each utilization field.

Given all the considerations above, the current paper represents a comprehensive geo-mechanical study of the magmatic rocks from the Southern Apuseni Mountains, rocks represented by a wide range of varieties, such as gabbro, diabase, granite, rhyolite, and basalt used in raw or manufactured form for civil engineering construction and ornamental/decorative works.

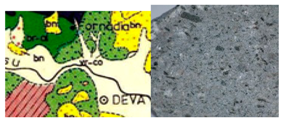

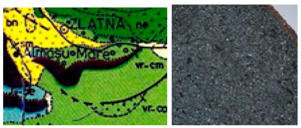

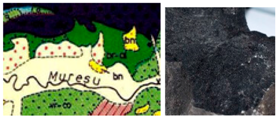

2. Geology of Southern Apuseni Mountains

The Apuseni Mountains are located between cross aisles of Mures and Somes, representing the largest and most complex subdivision of Occidental Carpathian [7,8,9]. They represent an internal arch in relation to Southern and Eastern Carpathian; they close westward the Transylvania Depression. Southern Apuseni represent central compartment of Occidental Carpathians, including a particularly complex area as tectonic and lithology. Morphologically, Southern Apuseni Mountains are delimited between Mures River and the alignment formed by the settlements Bârzava-Mădrizeşti–Hălmagiu-Câmpeni on the south and to the north of Roşia Montană-Sălciua-Ocoliş [10]. Southern Apuseni Mountains are also known as the Ore Mountains.

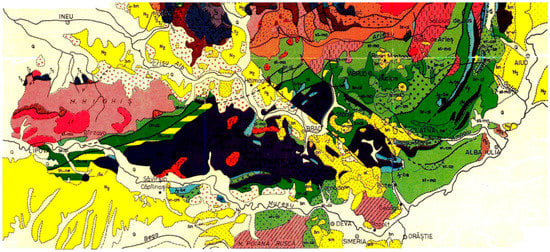

Although as a major structural geological unit, Apuseni Mountains have a particular position that deviates from the sinuous direction of the Alpino-Carpathian-Balkanides-Caucasian chain, they have resulted from the evolution of a rifting zone that occurred in the Transylvanian—Pannonian microplate. This was divided into two blocks—Pannonian block and Transylvanian block—by means of a breakage that occurred long before the Medium Jurassic. The geologic processes that led to the building of structural-genetic unit of the South Apuseni from Mountains Apuseni were influenced by behavior of edge of Pannonian block, which also resulted in the North Apuseni. The South Apuseni has evolved from a labile area of the Alpino-Carpathian geosyncline before Medium Jurassic (Dogger), in which there were many geological events. Due to these geological events, from stratigraphical point of view, in the structure of South Apuseni Mountains can be distinguished the following litho-structural-genetic units [11]: pre-alpine crystalline massifs (crystalline schist); ophiolitical magmatit; sedimentary pre-laramic; laramic magmatit; Neogene vulcanite; and post-laramic sedimentary from inter-mountain depressions (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Geological map of Apuseni Mountains (according to Mutihac, 1990).

Actual tectonic arrangement of the South Apuseni Mountains is closely linked to their geological evolution in the framework of central and southeast Europe Alpine area [12]. In this context, the South Apuseni Mountains represent the suture or the scar of a labile area, which in its development has known a phase of expansion accompanied and followed by particular geotectonic processes, which can include: magmatic basic activity, processes of shortening the crust, subduction, oceanic crust consumption, etc.

3. Characterization of Studied Magmatic Rocks from South Apuseni

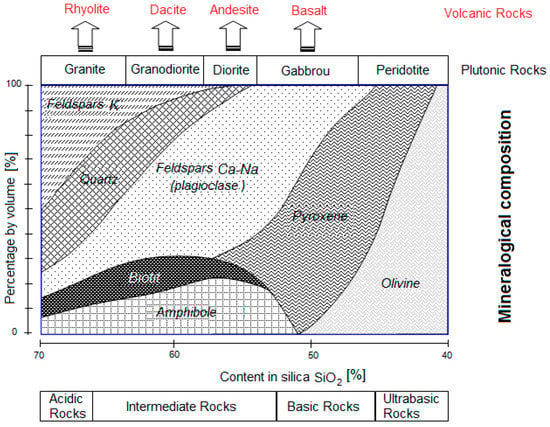

Magmatic rocks form one of the three major groups of rocks, resulting from cooling and solidification of magma inside the crust or near the surface; relative to the solidification time, these rocks are classified as follows: volcanic rocks stratified or eruptive, with fine grain (acidic rocks and basic rocks that includes mainly basalts) and plutonic massive characterized by the presence of crystals of larger size as compared to the first category (acidic rocks category that includes granite, and basic rocks as gabbro—a classification of igneous rocks was performed in 1966 by Mason and taken up by other researchers [13,14]), classification performed based on the mineral composition and relative to way of formation of these rocks (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Schematic position of main magmatic rocks depending on their mineralogical composition (according to Mason (1966) cited by Beauchamp).

In Southern Apuseni are known associations of igneous rock formed in three distinct phases of the alpine cycle [15]: Jurassic–Cretaceous lower magmatic rocks, equivalent of ophiolite magmatic rocks; Paleocene–Upper Cretaceous magmatic, equivalent of laramic magmatic rocks; and Neogene–Quaternary magmatic rocks, equivalent of Neogene effusive rocks. In the characterization of Southern Apuseni, the ophiolite magmatic rocks represented by basalts, andesite, dacite and even rhyolites form a huge mass that extends over a length of 190 km between Aries Valley and town of Zăbalţ on Mureş Valley; these rocks can reach a maximum width of 40 km. In Southern Apuseni, laramic magmatism manifested by lava is represented by occurrences of basaltic andesites from Măgura Brănişca and Măgura Sârbi. In genetic point of view, Neogene–Quaternary volcanism from Southern Apuseni falls into two types, acidic and respectively intermediate calc-alkaline.

3.1. Mineralogical and Petrographical Characterization of Igneous Rocks Analyzed

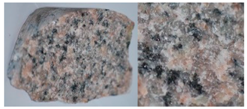

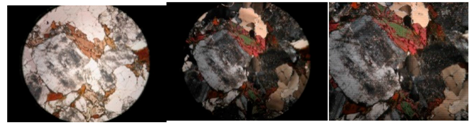

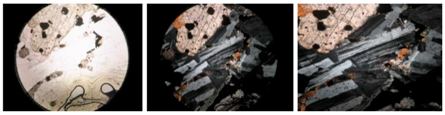

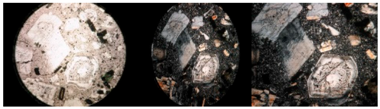

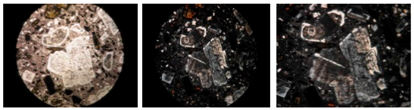

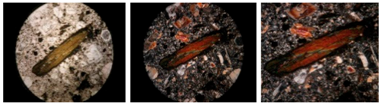

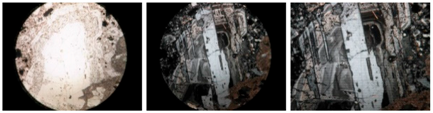

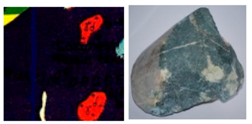

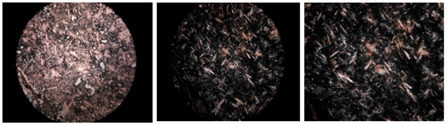

All the rocks presented in this study were analyzed at both macroscopic and microscopic level to determine the mineralogical and petrographical properties necessary for the further study of parameters defining the geo-mechanical behavior of the rock.

The mineralogical and petrographical study was achieved based on the analysis of thin sections examined with a polarizing microscope. Based on the macroscopic and microscopic analyses, a detailed description of these rocks is presented (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Macroscopic and microscopic characterization of magmatic rocks types analyzed.

3.2. Chemical Composition of Magmatic Rocks Analyzed

The chemical composition of rocks was determined based on analysis performed on 15 samples. The chemical analysis aimed to identify the main oxides, with emphasis on silica dioxide, as an indicator of the acid, basic or neutral type of the analyzed magmatites. The chemical analysis was performed in the Chemistry Laboratory at the University of Petrosani, using an XRF spectrometer (X-ray fluorescence). The alkali–ggregate reaction emphasizes the reactivity and partial harmfulness of aggregates containing one or more forms of the silica dioxide with lower crystallization (opal, chalcedony, tridymite, and cristobalite) and volcanic glass rich in silica dioxide. The need of testing the reaction alkali–ggregate is dictated by concrete, which comes in permanent or temporary contact with water or, generally, with a humid environment [2,3,16]. Testing of the alkali–ggregate reaction was performed in conformity with standard STAS 5440-70:

- To determine the reduction of sodium hydroxide solution Rc, Equation (1) was used:where Rc represents the reduction of the concentration of sodium hydroxide solution, in mmol/dm3; f is the factor of chlorhydric acid utilized during titration 0.05 n; V2 is the volume of chlorhydric acid 0.05 n utilized for titration of analyzed sample in cm3; V3 is the volume of chlorhydric acid 0.05 n utilized for titration of witness sample, in cm3; and V1 is the volume of diluted solution, in cm3 (20 cm3).

- The quantity of silica dioxide from the filtered sodium hydroxide solution was determined with Equation (2):where: Sc is the concentration of dissolved silica dioxide in mmol/dm3; A1 is the concentration of silica dioxide in g, in 100 cm3 diluted solution; A2 is the concentration of silica dioxide in g, in 100 cm3 witness solution, diluted; and 60.06 is the molecular mass of silica dioxide, in g.

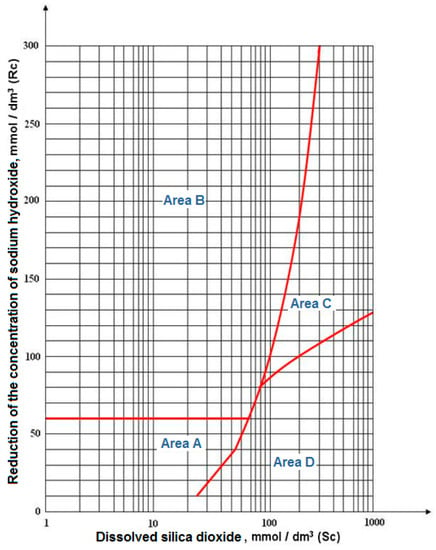

Based on the reaction alkali–ggregates, observations are drawn regarding the suitability of using aggregates with cements to attenuate or annihilate the reactivity. These observations are used in the particular case of the aggregates used to mix cements, which will face continuous contact with water or a moist environment [16]. The results following this analysis are given in Table 2, while the noxious character of the aggregates is determined based on the diagram in Figure 3 and classification in Table 3.

Table 2.

Average values for alkali–ggregates reaction.

Figure 3.

Verification of the reaction alkali–ggregates: aggregates from zone A are non-reactive and are recommended for utilization; aggregates from zone B are generally unreactive; aggregates from zone C are characterized by a potentially significant reactivity; and aggregates from zone D are considered harmful.

Table 3.

Rock and aggregate characterization relative to Sc.

3.3. Physical and Resistance Properties of Magmatic Rocks

The physical rock state enables a quantitative description as well as an estimate of resistance characteristics. This description and estimate was accomplished by determining physical characteristics, such as specific density, apparent density, apparent porosity, compaction, natural moisture, and water absorption [2,3,17]. The physical and resistance properties were determined according to valid standards, as per recommendation of the International Bureau of Rocks Mechanics and International Society of Rocks Mechanics. The measuring of physical and resistance properties has been made in accordance with specific protocols, recommendations of the International Bureau of Rock Mechanics and International Society of Rock Mechanics (see Table 4 and Table 5).

Table 4.

Average values of physical characteristics of magmatic rocks from Southern Apuseni Mountains.

Table 5.

Average values of resistance characteristics of magmatic rocks from Southern Apuseni Mountains.

3.4. Admissibility Condition of Rocks Based on Provenance

Rocks used for road construction should have homogeneity of their mineralogical and petrographic structure and composition, without any traces of physical or chemical alteration. Pyrite, limonite or soluble salts must not be present in the rock mass; the presence of microcrystalline or amorphous silica is also undesirable, as it can react with alkali from cements [18]. Additionally, it is not recommended to use aggregates from altered, soft, friable, porous and vacuolar rocks, with a granular content exceeding 10% in broken rocks or 5% in chippings. Based on the main physical–mechanical characteristics, the rocks employed for natural rock products are classified into five classes of admissibility, as described in Table 6.

Table 6.

Admissibility conditions of rocks for railroad and road construction.

Shattering caused by compression in dry state and abrasion by Los Angeles machine are determined on broken rock, sort 40–63. Rocks that do not fulfill the freezing–thawing resistance cannot be used for road construction [18].

4. Assessment Methodology of Rocks

For qualitative assessment of igneous rocks such as granites, rhyolites, diorites, andesites, gabbro, diabases and basalts for use in the form of aggregates, coarse stone or ornamental works, the developed and applied methodology in this case is based on the principle of assessing the conformity and the level of safety considering the requirements of the standards. The aim of conformity assessment was first to verify if the general and specific requirements of rocks used as building materials are in compliance. Conformity analysis is often used in the field of occupational health and safety [19,20,21]; the proposed method is practically based on definition of conformity encountered in the field of safety, so we established a mathematical model for rock assessment that considers their imposed requirements.

The proposed method consists in achieving a sheet or a set of individual sheets for each rock analyzed; the sheets include the properties according to the general and specific requirements that the rocks must satisfy to be used in construction. Every characteristic of rock was considered a quantitative assessment indicator and noted by granting certain points. The grading system used in this method, namely the assessment of each characteristic, was performed as follows: 5 points, if the requirement described by indicator is totally satisfied; 4 points, if the requirement described by indicator is partly satisfied, maximum 75%; 3 points if the requirement described by indicator is partly satisfied, percentage of 50–75%; 2 points if the requirement described by indicator is partly satisfied, percentage of 25–50%; 1 point if the requirement described by indicator is unsatisfied (less than 25%); and not applicable, if the requirement described by indicator is totally unsatisfied.

Each characteristic regarded as an indicator has an associated weighting coefficient with value of 1, 2, 3, 4 or 5 according to the requirement importance and the class in which the rocks were classified relative to the requirements or conditions of admissibility (Table 6). After assessment of all characteristics (indicators from sheets), the following were determined: conformity level (NC), safety level (NS) and unconformity degree (GC) according to the obtained points (PO) and maximum points (PM) (see Table 7).

Table 7.

Proposed methodology for assessing the conformity of rocks and the safety level.

The information obtained by this method refers to the non-conformities according to the conditions imposed by standards, which are not totally satisfied; and the conformity level according to the conditions that the rocks must satisfy and the safety level of rocks used in construction. Depending on NS and NC, the correspondence as against allowable criteria is presented in Table 8 and Table 9.

Table 8.

Correspondence between safety criterion NS and rocks’ admissibility in construction.

Table 9.

Classification of rocks according to NC.

5. Results and Discussion

For each type of rock considered in the study, the following have been analyzed: structure, mineralogical–petrographical composition, chemical composition and alkali–aggregates reaction. In addition, laboratory tests to establish the values of physical and mechanical characteristics of the 15 analyzed rock samples were carried out. The experimental data interpretation has lead to the following findings (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5):

- Gabbro is homogenous rock from the perspective of structure and mineralogical–petrographical composition, without visible traces of physical and chemical degradation; apparent density of 2.844 × 103 kg/m3; value of porosity (1.516%) leading to rock classification as “less porous”; a small difference between specific density and apparent density lead to significant compaction of the rock, with an average of 98.483%; water absorption is directly influenced by porosity an average of 0.427% leading to the classification of the rock as “least absorbent”; from the perspective of resistance to breakage due to monoaxial compression, the rock is classified as having “high resistance”.

- Diabase is homogenous rock from the perspective of structure and mineralogical–petrographical composition, without visible traces of alteration, despite a system of millimeter fissures colmated with carbonates; volumetric density of 2.7823–2.7876 g/cm3, with an average of 2.749 g/cm3, leading to rock classification as “heavy”; 1.267% porosity, leading to rock classification as “least porous”; compaction of 98.732%; water absorption of 0.69%, leading to the classification of the rock as “least absorbent”; from the perspective of resistance to breakage due to monoaxial compression, the rock is classified as being “resistant”.

- Granite is homogenous rock from the perspective of structure and mineralogical–petrographical composition, without visible traces of alteration; volumetric density of the three granite types are 2.619–2.625 g/cm3, leading to rock classification as “heavy”; porosity of 0.58–0.82% leading to rock classification as “less porous”; water absorption from 0.29% to 0.31%, leading to the classification of the rock as “less absorbent”; compaction from 99.17% to 99.41% is regarded as high; mechanical resistance is considered very high.

- Diorite is homogenous rock from the point of view of structure and mineralogical–petrographical composition, without visible traces of alteration; volumetric density of 2.95 g/cm3, leading to rock classification as “heavy”; porosity of 0.45% leading to rock classification as “less porous”; rock resistance is considered high.

- Rhyolite has various alteration states; following alteration, the volumetric density is relatively low, however the rock is still classified as “heavy”; porosity is high, as a result of the differences between the values of volumetric density and apparent density; water absorption leading to the rock classification as “less absorbent”; porosity influences the compaction, which is 96.89%; mechanical resistance is considered low.

- There are six types of andesites, with the following properties: various alteration states, from incipient to advanced; based on the alteration states, the volumetric density varies accordingly between 2.45–2.67 g/cm3; alteration affects porosity, which presents different values; under the influence of alteration phenomenon, compaction presents values of 95.62–99.26%; rock moisture varies between 0.64–2.76%; monoaxial compressive strength is 110.19–143.53 MPa.

- There are two types of basalts characterized as follows: no alteration visible, leading to a homogenous structure; volumetric density of 2.69–2.70 g/cm3; relatively low porosity, 0.89–0.93%; reduced absorption, at 1.23–1.33%; water saturation is 0.62–0.67 leading to rock classification as “moist”; based on their mechanical resistance, these are considered “very hard rocks”; based on deformation property, the rock presents an elastic behavior. For each of the 15 types of rocks analyzed, applying the methodology proposed the conformity level, safety level and unconformity degree were determined. The results are given in Table 10.

Table 10. Summary of results obtained concerning the assessment of analyzed rocks.

Table 10. Summary of results obtained concerning the assessment of analyzed rocks.

The conditions of admissibility of origin rocks and the values obtained for each type of rock are given in Table 11. Determining the shattering resistance was achieved by compression in dry state, and the abrasion by Los Angeles machine, on broken rock, size class 40–63.

Table 11.

Comparison between admissibility conditions and results obtained.

6. Conclusions

The observations made on rocks collected from South Westerners Apuseni Mountains, Romania (for use in construction) and literature review performed allowed their classification as magmatic rocks associated to the Alpine orogeny. Generally, plutonic rocks presented reduced natural moisture content and low porosity. On prolonged contact with water, until saturation state, they have not lost cohesion.

The proposed method has been designed to facilitate the assessment and verification of the criteria to which the rocks should comply to be used as building materials, given the admissibility conditions imposed by standards.

Applying this evaluation system allows determining the specific parameters of the rock quality requirements, namely the conformity and unconformity degrees, and more specifically the safety level that these rocks can provide if they are used in the construction field, either as aggregates or as construction materials. The proposed method represents an appropriate tool for assessment and verification of the requirements regarding the quality of rocks used in construction. Concerning the proposed classification relating to the correlation between safety criterion and the risk of rock use and their admissibility in construction, the obtained results show that, from the analyzed types of rocks, more than 80% of them fall into the class of rocks with high and very high safety level, which means that the risk of use is very low to low, and, in some cases, even nil, which means high and very high conformity level.

Relative to the imposed conditions of admissibility, provenience rocks were classified into four classes, ranging from A to D, as follows: granite, diorite, basalt and a part of andesite rocks type fall in class A, as high safety degree rocks being very good for constructions; diabases and large part of andesites are included in class B, with a high level of safety and conformity; andesites from Deva–Certej area are included in class C, with a medium level of safety and conformity; and Săcărâmb andesite and Roşia Montană rhyolite have been identified in class D from the viewpoint of conformity and safety level.

Author Contributions

Mihaela Toderaº conducted the systematic sampling and measurement campaign and wrote the paper. Roland Iosif Moraru supported the conception of the review, analyzed the data, revised the review results, supported the interpretation of the results. Ciprian Danciu developed and applied the methodology for assessing the conformity of rocks and the safety level, Grigore Buia performed the mineralogical and petrographical characterization of analyzed igneous rocks and Lucian—Ionel Cioca supported the conception of the review and revised the review results and drawn conclusions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Funding sponsors had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Renard, M.; Lagabrielle, Y.; Martin, E.; Rafelis, M. Eléments de Géologie, 15th ed.; Edition du POMEROL; Dunod Publishing House: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Toderaş, M. Tests on Materials; Focus Publishing House: Petroşani, Romania, 2008; p. 440. ISBN 978-973-677-141-5. (In Romanian) [Google Scholar]

- Danciu, C. Geomechanics of Magmatites from South Apuseni; Universitas Publishing House: Petroşani, Romania, 2010. (In Romanian) [Google Scholar]

- Tiess, G.; Chalkiopoulou, F. Sustainable Management of Aggregates Resources and Sustainable Procurement Combined at Regional/National and Transnational Level; Technical University of Crete: Chania, Greece, 2011. (In Romanian) [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp, J. Les Roches Propriétés et Utilisation; Université de Picardie Jules Verne: Amiens, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ivascu, L.; Cioca, L.I. Opportunity Risk: Integrated Approach to Risk Management for Creating Enterprise Opportunities. Adv. Educ. Res. 2014, 49, 77–80. [Google Scholar]

- Ielenicz, M.; Patru, I.; Ghincea, M. Romania’s Sub-Carpathians; Universitară Publishing House: Bucureşti, Romania, 2003. (In Romanian) [Google Scholar]

- Irimuş, I.A. Physical Geography of Romania I; Casa Cărţii de Ştiinţă Publishing House: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2003. (In Romanian) [Google Scholar]

- Velcea, V.; Savu, A. Geografia Carpaţilor şi a Subcarpaţilor Româneşti; Didactică şi Pedagogică Publishing House: Bucureşti, Romania, 1982. (In Romanian) [Google Scholar]

- Mutihac, V. Geologic Structure of Romanian Territory; Tehnică Publishing House: Bucureşti, Romania, 1990. (In Romanian) [Google Scholar]

- Cioca, L.-I.; Moraru, R.I.; Babut, G.B. A Framework for Organisational Characteristic Assessment and Their Influences on Safety and Health at Work; Book Series: Knowledge Based Organization International Conference; Land Forces Academy: Sibiu, Romania, 2009; Volume 2, pp. 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Săndulescu, M. Geotectonics of Romania; Tehnică Publishing House: Bucureşti, Romania, 1984. (In Romanian) [Google Scholar]

- Boillot, G.; Huchon, P.; Lagabrielle, Y. Introduction à La Géologie: La Dynamique de la Lithosphere, 4th ed.; Editura Dunod: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pomerol, C.; Renard, M.; Lagabrielle, Y. Eléments de Géologie; Dunod Publishing House: Paris, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Har, N. Alpine Basaltic Andesites in Apuseni Mountains; Casa Cărţii de Ştiinţă Publishing House: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2001. (In Romanian) [Google Scholar]

- STAS 5440-70. In Testing the Alcalii–Aggregate Reaction; Romanian Standard: Bucharest, Romania, 1970. (In Romanian)

- Brooks, R.H.; Corey, C.T. Hydraulics Properties of Porous Media; Colorado State University: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- SR 667/2001. In Admissibility Conditions; Romanian Standard: Bucharest, Romania, 2001. (In Romanian)

- Băbuţ, G.B.; Moraru, R.I. Occupational Health and Safety Auditing: Practical Application and Projects Guide; Universitas Publishing House: Petroşani, Romania, 2014. (In Romanian) [Google Scholar]

- Cioca, L.-I.; Ivascu, L. Risk Indicators and Road Accident Analysis for the Period 2012–2016. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionica, A.; Leba, M. Human action quality evaluation based on fuzzy logic with application in underground coal mining. Work 2015, 51, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).