Abstract

Family agriculture is a fundamental pillar in the construction of agroecological agri-food alternatives fostering processes of sustainable rural development where social equity represents a central aspect. Despite agroecology’s critical openness, this area has not yet incorporated an explicit gender approach allowing an appropriate problematization and analysis of the cultural inequalities of gender relations in agriculture, women’s empowerment processes and their nexus with sustainability. This work presents an organized proposal of indicators to approach and analyze the degree of peasant women’s equity and empowerment within a wide sustainability framework. After a thorough bibliographical review, 34 equity and empowerment indicators were identified and organized into six basic theoretical dimensions. Following the collection of empirical data (from 20 cacao-producing families), the indicators were analyzed and reorganized on the basis of hierarchical cluster analysis and explanatory interdependence into a new set of six empirical dimensions: (1) access to resources, education and social participation; (2) economic-personal autonomy and self-esteem; (3) gender gaps (labor rights, health, work and physical violence); (4) techno-productive decision-making and remunerated work; (5) land ownership and mobility; and (6) diversification of responsibilities and social and feminist awareness. Additionally, a case study is presented that analyzes equity and empowerment in the lives of two rural cacao-producing peasant women in Ecuador.

1. Introduction

Peasant family farming occupies a central place in agroecological theory and practice. In addition to representing 88 percent of agricultural farms and producing 56 percent of the world’s food supply [1], family agriculture is a fundamental pillar in the construction of agri-food alternatives and the fight against climate change [2]. Thus, besides being a techno-productive alternative for the design of agroecosystems under ecological criteria, agroecology aims at fostering processes of sustainable rural development where social equity represents a central aspect [3,4]. However, in spite of this critical perspective, agroecology has not yet incorporated an explicit gender approach allowing an appropriate problematization of social relations in patriarchal contexts and of their nexus with sustainability [5]. This neglect takes place despite the fact that women have less access to productive resources and social services, suffer higher unemployment levels and are less involved in political and social participation, while bearing the primary responsibility for family care [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. Therefore, androcentrism in agroecology has permitted the invisibility of “internal contradictions” within the peasant movement and family farming, as well as the undervaluation of the role of peasant women [8,9].

Gender analyses have a long tradition in various fields of study. Different forms of feminism (theory and practice) have identified and analyzed micro and macro symbolic, economic and social organization structures that crystalize male dominance in patriarchal cultures [8,10]. The concepts of “sex/gender system” and “patriarchy” are essential for this purpose. The sex/gender system makes reference to the socio-historical construction of biological sex identities [11], whereas patriarchy alludes to the institutionalized power structures that hierarchize genders and unequally distribute power, responsibilities (sexual division of labor) and opportunities to access the resources [12,13]. Within the field of development and agriculture, Boserup [14] was one of the first women authors to declare that women did not equally benefit from development programs due to discrimination in their “natural” ascription to the roles of mothers and wives. Following this author, studies on gender and development have gradually become more complex, in consonance with the different approaches and debates around gender inequalities [15,16].

The present work is based on two concepts that are essential for the construction of gender equality and that have been widely addressed from the fields of feminism and development: “equity” and “empowerment”. While equity seeks for justice in the treatment of men and women according to their specific needs [17], empowerment implies building critical awareness to transform the structures that produce gender inequalities [18,19]. In this sense, empowerment is a process of change towards greater equity, both individual and collective [20], where women actively work to regain control and autonomy over their own lives, bodies and territories in the material, social and symbolic spheres [21,22]. In the field of agroecology, those gender inequalities that have been reproduced within the food sovereignty movement itself are now starting to be explicitly analyzed [23]. The critical commitment and epistemological openness of agroecology [24] and food sovereignty [25] welcome a radical feminist analysis, given the approach to power relations embedded within these concepts. This is evidenced by the fact that Vía Campesina identifies work around gender inequity as one of its basic premises, thus acknowledging (peasant) women’s work and historical responsibility in relation to both feeding and household care [26]. Despite the progress made, the effective incorporation of the gender perspective to the evaluation of agroecological and food sovereignty projects is still, to a great extent, inexistent [27,28,29].

Among the pioneering works in this area, it is possible to highlight the contributions made from the field of ecofeminism [30,31], as well as those of some women authors from agroecology itself [32]. Empirical works, such as that of Carney [33], point towards understanding how gender inequity is associated with poverty, discrimination and lack of food sovereignty in Santa Barbara County. Bezner Kerr et al. analyze the relation between gender inequity and malnutrition in Malawi [34] and how the intersection between gender and class dynamics combined with state policies works to prevent food sovereignty processes among certain groups in the country [35]. McMahon [36] argues that small-scale women farmers are pivotal in the creation of alternative local agri-food networks in British Columbia. Recent publications as that by Schwendler and Thompson [37] explore the implications of combining agroecology and gender education within the Brazilian Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra (MST, Landless Rural Workers’ Movement). García Roces and Soler Montiel [5] show how agroecological projects open the door to women’s participation, visibility and appreciation, strengthening their self-esteem and their economic autonomy in the community of Moreno-Maia (Brazil), even without a prior change in the sexual division of labor [29]. Oliver [38] proves the relevance of technical assistance grounded in participatory feminist and agroecological perspectives in the process of reinforcing the production and commercialization systems of a cooperative founded by women in Uruguay. The author emphasizes the importance of prioritizing gender equity in sustainable agriculture initiatives, not only for reasons of social justice, but also to make visible and acknowledge women’s leadership and knowledge in agroecology.

Lopes and Jomalinis [39] affirm that agroecology may be an instrument for women’s empowerment. However, overcoming gender inequity in agriculture involves far-reaching changes that go much beyond analyzing equality in the access to resources and guaranteeing that women’s needs and priorities are satisfied [40]. Reinforcing the inclusion of the feminist perspective in agroecology requires implementing basic epistemological changes and developing methodological designs that allow making gender-built inequity visible. Taking this background into consideration, the main objective of this work is to propose, a set of qualitative/quantitative indicators (related to aspects that deserve special attention) to critically analyze and visualize from a holistic perspective: (a) the existing inequalities between men and women in agriculture; (b) the key aspects that reinforce women’s empowerment as a process of change; (c) women’s specific role in relation to sustainability, especially within the context of peasant family agriculture. After an intensive bibliographical review, 34 equity and empowerment indicators were identified and organized into six basic theoretical dimensions. Once calculated for the case of 20 peasant families, the indicators were reorganized according to hierarchical cluster analysis, and six new empirical dimensions were defined. Finally, with the purpose of proving the potentiality of the proposal, a case study is presented that analyzes equity and empowerment in the lives of two female cacao producers in Ecuador.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Building the Indicators Proposal

Gender indicators are an analytical tool that allows having a sense of the complexity of the analyzed systems and directing the decision-making process and the actions for change [41]. Different methodologies can be found in the literature to design sustainability indicator systems [42,43,44], as well as counting and multidimensional measurement proposals [45], especially in relation to fuzzy indicators [46,47]. The present proposal of gender indicators has been built along eight methodological steps: Step 1: bibliographical review on women’s equity and empowerment and on the methodologies for sustainability assessment; Step 2: definition of the basic analysis dimensions and gender indicators based on Step 1; Step 3: design of a questionnaire and semi-structured interview to gather the information required for the indicators; both methodological tools were integrated into a more complete questionnaire and a longer interview that permitted gathering techno-productive, socioeconomic and political-institutional information concerning the peasant units; the collection of empirical data took place during 2015; Step 4: fieldwork, during which 20 peasant family units were analyzed; additionally, six more interviews were conducted with several key informants in the area and, for ten months, participant research techniques [48] were implemented in the province of Guayas, Ecuador; Step 5: discussion and adjustment of the basic dimensions and indicators according to the information gathered through the questionnaires/interviews and a new bibliographical review; Step 6: fieldwork to complete the information; Step 7: synthesis and integration of the results; using the MESMIS (Marco para la Evaluación de sistemas de Manejo de Recursos Naturales mediante Indicadores de Sustentabilidad) recommendations [49], a minimum threshold (0 for the worst women’s equity and empowerment situations) and a maximum threshold (10 for the best situations) were established for every indicator; the reference values were taken from the literature, the questionnaires and the judgement of experts [50]; Step 8: statistical analysis and elaboration of the final proposal; in order to do so, a hierarchical cluster analysis using Ward’s linkage criterion was applied [51]. The data were analyzed using SPSS software, Version 21 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

2.2. System Boundaries

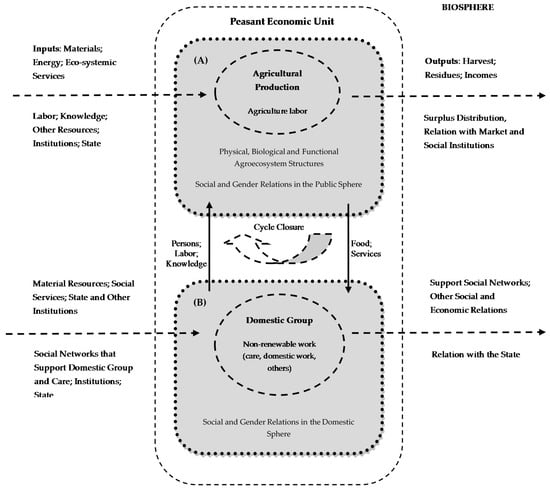

The indicators’ proposal has been designed for the analysis of the peasant economic unit (PEU) or domestic group as the basic system for understanding family agriculture. As shown in Figure 1, the PEU consists of two clearly interrelated spheres or spaces. Even though sustainability assessment methodologies usually focus on socioeconomic and environmental interrelations within the agricultural sphere (A), these must be understood in interdependence with the relations developed within the domestic sphere (B). Analyzing the socioeconomic relations of the domestic group is essential in order to determine the degree of sustainability of the PEU as a whole.

Figure 1.

System boundaries of gender indicators.

2.3. Cacao Women Producers in Ecuador

This work has analyzed two PEUs of the province of Guayas (Ecuador). The main agricultural activity of these farms is the production of cacao, a crop of great economic and territorial relevance in Ecuador that involves about 94,855 production units, 59 percent of which are small family farms [52]. Following Carrasco and Domínguez [53], two cases have been selected that are similar as regards domestic group typology and women’s age, but polarized in terms of equity and empowerment. The first case is that of “María”, a 52 year-old peasant woman who, together with her husband “Néstor”, works at a small conventional cacao farm. The second case is that of “Gloria”, a 49 year-old peasant woman who, like María, works with her husband “Carlos” at a small diversified organic cacao farm. Both women live with their respective husbands and have children over 18, who live in separate houses within the same farm. For a better understanding of the analysis, the results of the indicators of the two PEUs have been graphically represented through simple aggregation (weight = 1).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Dimensions of Women’s Equity and Empowerment

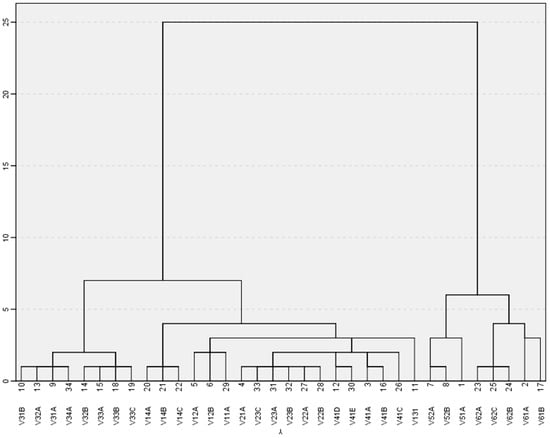

After a thorough bibliographical review, 34 equity and empowerment indicators were identified and organized into six basic theoretical dimensions and 14 subcategories. Those basic dimensions and subcategories were: (1) access to material resources (money, mobility and other material resources); (2) access to social services (labor rights, education and access to the health system); (3) total distribution of labor and use of time (total work distribution and availability of personal time); (4) social participation (social participation itself and social and feminist awareness); (5) personal autonomy (capacity for personal decision-making and belonging to social and personal-affective networks); and (6) emotional and physical health. After the collection of field data, the indicators were calculated and reorganized on the basis of hierarchical cluster analysis (see Figure 2) into six new dimensions and 16 analytical subcategories (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6): (1) access to resources, education and social participation; (2) economic-personal autonomy and self-esteem; (3) gender gaps (labor rights, health, work and physical violence); (4) techno-productive decision-making and remunerated work; (5) land ownership and mobility; and (6) diversification of responsibilities and social and feminist awareness. This new classification allowed understanding with empirical clarity the interdependence of the theoretical dimensions initially defined.

Table 1.

Access to resources, education and social participation.

Table 2.

Economic-personal autonomy and self-esteem.

Table 3.

Gender gaps (labor rights, health, work and physical violence).

Table 4.

Techno-productive decision-making and remunerated work.

Table 5.

Land ownership and mobility.

Table 6.

Diversification of responsibilities and social and feminist awareness.

3.2. Interrelations and Complexity of Women’s Equity and Empowerment

As shown in this paper, empowerment and equity analysis requires a multidimensional and complex perspective. Women’s access to material resources is the first key element in the debates on equity and empowerment. Access to land and other means of production (machinery, credit, water, etc.) are historical vindications of the peasant movement where women are found in clear disadvantage in relation to men (Indicator 5.1.a). Women’s formal access to productive resources represents great progress; however, it does not necessarily imply the effective control of such resources. On many occasions, despite women’s ownership of the resources, men are still the ones making decisions about them (4.1.a) [54,55]. Lesser real control over the productive resources and the decisions that concern them limits women’s access to one of the main forms of income in peasant units [56]. In the case of money, it is similarly necessary to discriminate between formal access and its effective availability (2.1.a and 1.2.a). In rigid patriarchal families, it is customary for women to be subject to their husbands’ criteria or to those of other male members of the family, whenever they need to use any economic resources, even their own [57].

Likewise, it is imperative to analyze women’s access to other types of material resources, not related to the economic unit’s main activity (1.2.b and 6.1.a). For instance, it is common among peasant women to have other sources of individual income, to manage resources related to animal raising and sale and the transformation of agricultural products or to rely on other productive areas (generally smaller and of lower quality) [54]. According to FAO [58], although these resources do not usually generate a great amount of income, they allow women a certain degree of personal (and familial) autonomy and, thereby, can be considered spaces of personal empowerment. Equal access to education (1.3.a and 4.1.d), Labor rights (3.1.a and 3.1.b) and the availability of appropriate health services (3.2.a and 3.2.b), as regards women’s specific needs, are two other important features of the existing gender gaps. Access to mobility cannot be forgotten (5.2.a and 5.2.b), given that transport in Ecuador is a key and differential element that can limit rural women’s autonomy in relation to the other dimensions (economic and personal autonomy, education and access to other resources) [59,60].

The sexual division of labor makes women responsible for domestic and care work [13], something that implies, in the majority of the institutional contexts where there is no formal recognition of such work, less access to social services derived from labor rights [61]. On the other hand, the sexual division of labor assigns to men the “duty” of home provisioning (material resources and money) and excludes them from household chores and care responsibilities (6.1.b) [62]. Nonetheless, as compared to men, women usually have a double presence: at home and in agricultural production tasks or at other income-providing work (what is known in the literature as “double burden” or “double workday”) (3.3.a and 4.1.b) [63]. As stated in previous studies, women have less time for themselves due to their having to comply with the gender mandate of being permanently available “for others” in their role of mothers or care providers [64]. Implementing the time accounting methodology [53,65,66], it is possible to analyze not only the sexual division of labor, but also women’s availability of time for personal care (3.3.b), free disposition and/or personal leisure (understood as the time during which no agricultural, care and domestic work, social participation or personal care activities are performed) (3.3.c), as a crucial aspect of their quality of life.

There is a broad consensus about how greater social participation (1.4.a), along with greater access to other resources [67,68,69], can contribute to women’s wellbeing and empowerment. Nevertheless, participation itself must also be analyzed from a critical perspective. As any relational space, participation is traversed by power relations where women generally occupy a disadvantageous position, due to less recognition and capacity for influence (1.4.b) [70]. Additionally, under equal opportunities with men, the double burden hinders women’s social participation due to lack of time (1.4.c). On the other hand, it is imperative to address the processes of feminist awareness and participation in women groups (6.2.b). As social and gender awareness increases, women are more predisposed to making personal and relational changes and to incrementing their political participation (6.2.a) and also their feminist activism (6.2.c). Becoming aware actively contributes to the problematization of inequalities in general and of gender inequalities in particular, reinforcing both individual and collective empowerment processes [18,19].

Institutionalized patriarchy reduces women’s capacity to act both in the private environment of the patriarchal family and in the public sphere, directly affecting their degree of autonomy [56]. Consequently, a lesser decision-making capacity in relation to farm productive issues (4.1.c) and/or household matters (2.2.a) is common among women. In strong male chauvinistic contexts, women frequently have to ask for permission to be able to carry out numerous personal or family decisions (2.2.b) [69,71]. Another basic element that helps understand the degree of women’s personal autonomy and empowerment is the analysis of women’s social network. Belonging to social networks (family and friends) is a component that strengthens women’s fallback position, providing them with personal-emotional and economic support. Improving women’s fallback position increases their capacity to act and their access to the resources required for subsistence and autonomy outside the home (1.1.a) [56]. The possibility to stay in their place of origin or uxorilocal residence (with the woman’s parents or close to them) is another social network factor that can reinforce women’s capacity to act (4.1.e).

Patriarchy imposes strong restrictions on men and women, which are internalized by them and act as real self-limitations directly affecting their self-esteem, health and, thereby, their quality of life. Conditioned by the dominant ideals of femininity, women build themselves as subjects with the purpose of satisfying everyone else’s needs (children, husband, other women, etc.). Consequently, women’s self-esteem is usually developed by living life through “the others”. The interest of feminism in improving women’s self-esteem derives from the (individual/collective) awareness that every woman has her own resources and initiatives, as well as the subjective capacities to use them or carry them out, which belong to her and, at the same time, define her [64,72]. This is why having their own life projects and spaces (personal and economic autonomy) is so important (2.3.a, 2.3.b and 2.3.c); this autonomy, however, should not be considered from an individualist perspective, but rather, from a community perspective [73]. Finally, despite the complexity and the objective limitations of the proposal, physical (and psychological) violence is a crucial issue in relation to women’s wellbeing (3.4.a). As highlighted by Bezner Kerr, progress in food sovereignty must address gender inequity, including access to the land, but also domestic violence [74].

Again, empowerment and equity analysis requires a complex perspective as regards this dimension. For instance, different authors have shown the positive synergism that exists between strengthening women’s fallback position and capacity to act and decreasing domestic violence [18,75,76]. However, these relations are not necessarily direct, but complex. The same fact may have different meanings and consequences (non-linearity) depending on the context and other historical and cultural components. A better negotiation position for women may also be perceived by men as a threat to their privilege and, therefore, become a source of violent situations [22,54].

3.3. Making Visible the Equity and Empowerment of Cacao Women Producers (Guayas, Ecuador)

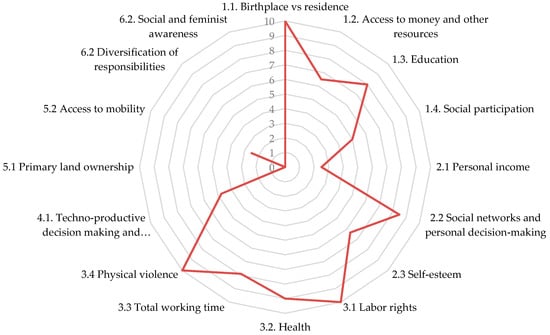

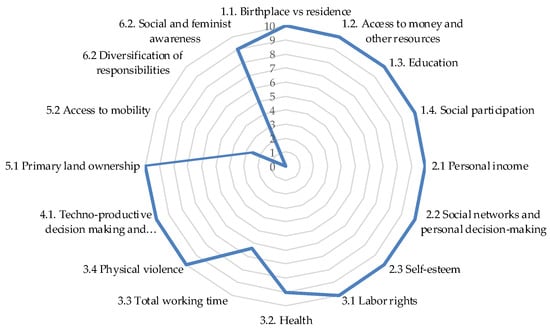

3.3.1. Exposing Gender Inequity

Applying this methodology to the case study and analyzing the results make it possible to understand how, despite significant differences in empowerment between the two cases, María and Gloria find themselves in a situation of inequality in relation to their husbands (see Figure 3 and Figure 4). Both women share the fact that they work more, have less access to time for themselves and, according to the sexual division of labor [13], are primarily responsible for domestic work and family care, whereas their respective husbands work exclusively in the cacao farm and rarely perform domestic activities, something that allows them to enjoy a greater amount of personal time. This way, women’s double workday takes them to work between 26 and 42 percent more time per week than their husbands. On average, women work in Ecuador approximately 30 percent more than men do [77]. On the other hand, male vehicle ownership, added to the fact of not having a driving license, makes Gloria and María less autonomous in relation to mobility and more dependent on their husbands or children. This limitation is especially important in rural contexts where public transportation is rare, as confirmed by the interviewees themselves.

Figure 3.

Equity and empowerment analysis for María (Case 1).

Figure 4.

Equity and empowerment analysis for Gloria (Case 2).

María finds herself in a situation of greater inequity, as compared to Gloria. She has less access to resources (income, land, etc.) and less economic and personal autonomy in decision-making than her husband. In addition, although to a lesser extent, she suffers also from unequal access to education and health assistance. Despite existing legal protection, only 25 percent of the land in Ecuador is owned by women, as a consequence of the traditional/patriarchal inheritance customs [78]. Néstor, María’s husband, owns the main lot of land and effectively makes use of all of the productive resources. María’s participation in agricultural tasks is reduced to only two of the seven main crop activities: harvest and post-harvest. According to her, she partakes as “help” to cover for the lack of external workers in the harvest season and is in charge of post-harvest activities, as they are more directly related to a “typically” feminine space: the home (cacao is “deveined” and dried in racks near the house). Furthermore, María does not participate in cacao sales, being excluded from the direct access to money, which is in turn controlled and provided mainly by her husband. Hence, progress towards equity would involve both women’s direct access to money and free disposition of it [40].

María has little autonomy in decision-making, both in the farm and at home, and usually asks her husband for permission whenever she needs to perform an activity that implies mobilization outside the farm. A low level of gender awareness, added to a traditional (Catholic) religious socialization, contributes to naturalizing these situations of gender inequality as something desirable and morally justified. Consequently, María criticizes the behavior of women who do not “ask for permission” and “do not obey their husbands”, reproducing the logic of cultural domination [79]. Limited social participation is also relevant, as is the lack of involvement in formal/non-formal education and activities that may facilitate making contact with other realities and other, more empowered, women. Bezner Kerr et al. [80] point out the importance of iterative dialogues, inquiries and reflection with the farmers when it comes to identifying the conflicts between the different generations, classes and genders. María commented how her family’s traditional education did not allow her access to knowledge associated with agricultural work, in contrast to her brothers, because she had to fulfill women’s specific tasks. The large gender gaps affecting María undoubtedly contribute to her self-perceived low self-esteem and to her feeling of being, in her own words, “sickly, already a little old woman”, due to having had to work so much both in the fields and at home all her life.

3.3.2. Exposing Women’s Empowerment

Equity and empowerment are closely knit together. Thus, Gloria’s situation of greater equity is largely related to the individual and collective empowerment processes in which she is involved. Among the aspects that reinforce Gloria’s empowerment, it is important to highlight equal access to material resources and personal decision-making, a higher level of social participation and continuing education and a higher degree of gender awareness and personal self-esteem (Figure 4). Gloria not only owns the land, but also shares the productive resources and the money with her husband, Carlos. Gloria is the leader of two peasant organizations, of the first and second level, linked to the agroecological struggle in Ecuador. Furthermore, she actively participates as a volunteer in the town hall and the health centers of her county. As pointed out by Cramer et al. [81], it is very important to pay attention to the role played by women within organizations in the process of strengthening the bonds between agriculture, health, education and food security. Gloria’s social activism has a direct influence on the enhancement of her family’s social networks, in her social recognition and high (perceived and declared) self-esteem. According to her, one of the fundamental aspects in the process of change is related to the trainings she receives, which make both women and men start to realize that “women too have rights”.

As highlighted by Lopes and Jomalinis [39], this evidence shows the relevance of adopting a feminist perspective and questioning the different situations of subordination in which women are involved. Despite the higher degree of inequity suffered by María, it is also possible to identify spaces of empowerment and autonomy within her context. María owns a small farm for which she is fully responsible, since it is her personal inheritance. As she explains, “over there he has no power, because it isn’t his, and husbands have no control over inheritance; they don’t”. Even though that plot of land was only recently acquired and is yet to produce, it provides great personal satisfaction to María because she feels it is her own project. Moreover, María is in charge of raising small animals for self-supply and exchange with neighbors, friends and family, an activity that also provides her with a modest income. Similar to Gloria, she lives in an uxorilocal residence and has a wide affectionate family network, which reinforces her autonomy and self-esteem. María’s little social participation allows her more time for herself and to enjoy the environment, something that positively affects her quality of life, whereas the lack of time for herself due to her “double” workday (farm and home) and her high level of commitment and social engagement [67] are some of the aspects that burden Gloria the most. Finally, it is important to underline that, compared to their husbands, both Gloria and María have a high degree of empowerment and autonomy in relation to the work and aspects of life connected to social reproduction in the domestic and care contexts. In this sense, reproducing masculine mandates entails, for men, not only privileges, but also a price to pay and a loss of autonomy [82].

3.4. Social Sustainability: Beyond Production and the Public Sphere

Women’s empowerment and gender equity, in addition to being ethical imperatives, are intrinsically linked to socioeconomic and environmental sustainability. Different authors have shown the existing synergies between women’s empowerment/equity and improvements in productivity, access to food, the management of land, water, health and energy, etc.; see [83,84]. In spite of this, the relation between equity and sustainability cannot be automatically assumed, given that it is complex, multidimensional and often contradictory [29,84]. In this sense, the application of equity and empowerment indicators to the analysis of peasant units reveals women’s fundamental role in sustainability as a whole. In the two cases analyzed, both women actively contribute to the agricultural activity at the farm, even though María’s work is undervalued and socially considered as “help” [85]. Additionally, both women are responsible for their farms’ productive diversification, being as they are in charge of small animal raising and care (chicken, hens, pigs, etc.). Productive diversification not only improves the family’s economic income and food security, it also favors biodiversity and the resilience of the food system to cope with the impacts of climate change [86], reinforcing as well food sovereignty [2].

Other basic inputs to sustainability provided by Gloria and María are those related to the enhancement of social networks, particularly family and affective networks. In Gloria’s case, her intense social participation and her activism are essential for the farm’s performance, which, at the same time, is related to her continuous education (on agroecology and gender) and her effort to strengthen the political and organizational context in which she lives. The connection and ties to the community of populations scattered across the territory, the strengthening of family and social support networks, organizations and collective initiatives are fundamental pillars of social sustainability [87]. Finally, domestic and care work, mainly performed by women, is a vital aspect of social sustainability and, at the same time, a source of inequality. Care work is indispensable for the reproduction of life and the satisfaction of material, symbolic and affective needs, and this represents 30 percent of the total work performed in the two cases analyzed (in the case study, the data refer to two-person domestic groups; the percentage increases when other family members, such as children or elderly people, are also included). Nevertheless, domestic and care work are socially undervalued and/or overlooked. Valuing and socializing the responsibility for care work is a challenge that aims at increasing empowerment, equity and sustainability from non-androcentric perspectives [88].

4. Conclusions

The lack of a gender perspective in agroecology contributes to the invisibility of inequalities between men and women in peasant agriculture, and it also hinders the understanding of the system’s sustainability, as it does not incorporate the domestic and care aspects. The critical and transforming spirit of agroecology facilitates “knowledge dialogues” with different feminist approaches, from which power relations woven around sex/gender have been deconstructed and problematized. Women’s equity and empowerment are two of the fundamental aims of gender equality and social justice and, thereby, sustainability. Consequently, the present work has developed a proposal of gender indicators with the objective of visualizing and analyzing inequity/equity situations and empowerment processes affecting peasant women within the context of sustainability debates in agroecology. With this purpose, and following a thorough bibliographical review, six basic dimensions were defined. The empirical work and statistical analysis of the collected data allowed improving the initial proposal and reorganizing the indicators and dimensions according to their degree of correlation. A new empirical classification was thus produced, which included the following dimensions: (1) access to resources, education and social participation; (2) economic-personal autonomy and self-esteem; (3) gender gaps (labor rights, health, work and physical violence); (4) techno-productive decision-making and remunerated work; (5) land ownership and mobility; and (6) diversification of responsibilities and social and feminist awareness.

The application of the proposed methodology to the case study has permitted the visualization and analysis of the differences and similitudes in equity and empowerment of two cacao-producing peasant women in the province of Guayas (Ecuador). Despite substantial differences between the two analyzed cases, both women find themselves under situations of inequity with respect to their husbands. The double workday imposes greater total workloads on both women and reduces the time they have for themselves. In one of the two cases, it is important to add economic dependence, low personal autonomy in decision-making, less access to education and social participation as some of the most important issues. On the other hand, applying the indicators has allowed the visualization of aspects that are essential for the empowerment processes of the two women analyzed. The strengthening of the woman’s fallback position, through greater access and control of the economic, social and emotional resources, gender awareness and capacitation, increments empowerment and autonomy in the second case analyzed. According to the sexual division of labor, both women hold the main responsibility over domestic and care work, which, in spite of being socially devalued, is imperative for social reproduction and, consequently, social sustainability. As a final consideration, it is important to remember that patriarchy is an institutionalized social order that manifests itself on different structural levels. It is therefore essential to further advance our knowledge of sustainable agroecological alternatives at the level of the peasant economic unit, as done in the present study, as well as at the remaining levels, spanning up to the overall agri-food system. The gender perspective is thus indispensable for the correct understanding of the relations between the economic, political, environmental and personal dimensions in the process of building sustainable and fair agri-food alternatives.

Acknowledgments

This work, developed during academic year 2014–2015, is framed within a research project supported by the Agrarian University of Ecuador and entitled “Elaboration of a system of analysis of gender relations from an agroecological perspective in the cacao production area of Guayas (Ecuador)”. This research project is part of a larger project entitled “Moving towards food sovereignty: socioeconomic and environmental analysis of the agrifood system of cacao production in the province of Guayas (Ecuador). An approach from a socio-environmental complexity perspective”, included in the Prometeo Project of the Office to the National Secretary for Higher Education, Science, Technology and Innovation of the Republic of Ecuador. The authors would like to thank the women farmers and the cacao cooperatives participating in it for their cooperation. They would also like to thank Ramón Álvarez Esteban (University of Leon) for his help in the statistical analyses.

Author Contributions

This paper presents a team work research result written by the co-authors, Olga de Marco Larrauri, David Pérez Neira and Marta Soler Montiel. Olga, David and Marta designed the study. Olga conducted the interviews. Olga, Marta and David analyzed the interviews and discussed the results.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization. Agricultores Familiares: Alimentar el Mundo, Cuidar el Planeta; Food and Agriculture Organization of Unites Nations: Roma, Italy, 2014. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Altieri, M.A.; Funes-Monzote, F.; Petersen, P. Agroecologically efficient agricultural systems for smallholder farmers: Contributions to food sovereignty. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 32, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevilla-Guzmán, E.; Woodgate, G. Sustainable rural development: From industrial agriculture to agroecology. In The International Handbook of Environmental Sociology; Redclift, M., Woodgate, G., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, PA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, P.; Van Dusen, D.; Lundy, J.; Gliessman, S. Integrating social, environmental and economic issues in sustainable agriculture. Am. J. Altern. Agric. 1991, 6, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, I.; Soler, M. Mujeres, agroecología y soberanía alimentaria en la comunidad Moreno Maia del Estado de Acre. Brasil. Investig. Fem. 2010, 1, 43–65. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization. El Estado Mundial de la Agricultura y la Alimentación 2010–2011. Las Mujeres en la Agricultura: Cerrar la Brecha de Género en Aras del Desarrollo; Food and Agriculture Organization of Unites Nations: Roma, Italy, 2011. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- CEPAL (Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe); Food and Agriculture Organization; ONU Mujeres; United Nations Development Programme; Oregon Institute of Technology. Trabajo Decente e Igualdad de Género. Políticas para Mejorar el Acceso y la Calidad del Empleo de las Mujeres en América Latina y el Caribe; CEPAL: Santiago de Chile, Chile; Food and Agriculture Organization: Roma, Italy; ONU Mujeres: New York, NY, USA; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA; Oregon Institute of Technology: Santiago, Chile, 2013. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Siliprandi, E. Mulheres e Agroecologia: A Construção de Novos Sujeitos Políticos na Agricultura Familiar. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade de Brasília, Centro de Desenvolvimento Sustentável, Brasilia, Brazil, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, D.; Soler, M. Agroecología y ecofeminismo para descolonizar y despatriarcalizar la alimentación globalizada. Int. J. Political Thouch 2013, 8, 95–113. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J. Gender as a useful category of historical analysis. Am. Hist. Rev. 1986, 91, 1053–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, G. The traffic in Woman: Notes on the “political economy” of sex. In Toward an Anthropology of Women; Rayna, R., Ed.; Monthly Review Press: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Segato, L. Las Estructuras Elementales de la Violencia; Universidad de Quilmes: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2003. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Benería, L. Reproduction, production and the sexual division of labour. Camb. J. Econ. 1979, 3, 203–225. [Google Scholar]

- Boserup, E. Woman’s Role in Economic Development; Allen and Unwin and St. Martin’s Press: London, UK, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Benería, L.; Sen, G. Desigualdades de clase y de género y el rol de la mujer en el desarrollo económico: Implicaciones teóricas y prácticas. Mientras Tanto 1983, 15, 91–113. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- León, M. Poder y Empoderamiento de las Mujeres; Tercer Mundo Editores, Fondo de Documentación Mujer y Género de la Universidad Nacional de Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 1997. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme. Igualdad: América Latina Genera. Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo, 2011. Available online: http://www.americalatinagenera.org/es/documentos/tematicas/tema_igualdad.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2015). (In Spanish)

- Kabeer, N. Resources, Agency, Achievements: Reflections on the measurement of Women’s Empowerment. Dev. Chang. 1999, 30, 435–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, K. Planning Development with Women: Making a World of Difference; Macmillan Press: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Longwe, S.; Clarke, R. Women’s Equality and Empowerment Framework; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Wieringa, S. Women’s interests and empowerment: Gender planning reconsidered. Dev. Chang. 1994, 25, 829–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casique, I. Factores de empoderamiento y protección de las mujeres contra la violencia. Rev. Mex. Sociol. 2010, 72, 37–71. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Patel, R.C. Food Sovereignty: Power, Gender, and the Right to Food. PLoS Med. 2012, 9, e1001223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez, L.; Polanco, D.; Ríos, L. Reflexiones Acerca de Los Aspectos Epistemológicos de la Agroecología. Cuad. Desarro. Rural 2014, 11, 55–74. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Torres, M.E.; Roset, P.M. La Vía Campesina: The Birth and Evolution of a Transnational Social Movement. J. Peasant Stud. 2010, 37, 149–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmarais, A.A. The Vía Campesina: Peasant Women on the Frontiers of Food Sovereignty. Can. Woman Stud. 2013, 23, 140–145. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M.; Bellows, A. Introduction to symposium on food sovereignty: Expanding the analysis and application. Agric. Hum. Values 2012, 29, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencuela, H. Agroecology: A global paradigm to challenge mainstream industrial agriculture. Horticulturae 2016, 2, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Roces, I.; Soler Montiel, M.; Sabuco i Cantó, A. Perspectiva ecofeminista de la Soberanía Alimentaria: La Red de Agroecología en la Comunidad Moreno Maia en la Amazonía brasileña. Rev. Relac. Intern. 2015, 27, 75–96. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Mies, M.; Shiva, V. Ecofeminism; Zed Books: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Mellor, M. Feminism and Ecology; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Siliprandi, E.; Zuluaga, P. Género, Agroecología y Soberanía Alimentaria; Perspectivas Ecofeministas; Icaria: Barcelona, Spain, 2014. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Carney, M. Compounding crises of economic recession and food insecurity: A comparative study of three low-income communities in Santa Barbara County. Agric. Hum. Values 2012, 29, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezner Ker, R.; Lupafya, E.; Shumba, L. Food Sovereignty, Gender and Nutrition: Perspectives from Malawi. Food Sovereignty: A Critical Dialogue. In Proceedings of the International Conference Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA, 14–15 September 2013.

- Bezner Kerr, R. Seed Struggles and Food Sovereignty in northern Malawi. J. Peasant Stud. 2013, 40, 867–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, M. Standard fare or fairer standards: Feminist reflections on agri-food governance. Agric. Hum. Values 2011, 28, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwendler, S.F.; Thompson, L.A. An education in gender and agroecology in Brazil’s Landless Rural Workers’ Movement. Gend. Educ. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, B. The Earth Gives Us So Much: Agroecology and Rural Women’s Leadership in Uruguay. Cult. Agric. Food Environ. 2016, 38, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.P.; Jomalinis, E. Agroecology: Exploring Opportunities for Women’s Empowerment Based on Experiences from Brazil. Action Aid Brazil. Available online: http://legacy.landportal.info/sites/landportal.info/files/fpttec_agroecology_eng1.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2016).

- Huyer, S. Closing the Gender Gap in Agriculture. Gend. Technol. Dev. 2016, 20, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotondo, E.; Vela, G. Indicadores de Género: Lineamientos Conceptuales y Metodológicos para su Formulación y Utilización por los Proyectos FIDA de América Latina y el Caribe; Preval: Lima, Perú, 2014. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Bell, S.; Morse, S. Sustainability Indicators, Measuring the Immensurable; Earthscan: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Boulanger, P.M. Political uses of social indicators: Overview and application to sustainable development indicators. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2007, 10, 14–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Cerdá, M.; Rivera-Ferré, M. Indicadores internacionales de Soberanía Alimentaria. Nuevas herramientas para una nueva agricultura. REDIBEC 2010, 14, 53–77. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Alkire, S.; Foster, J. Counting and multidimensional poverty measurement. J. Public Econ. 2011, 95, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betti, G.; D’Agostino, A.; Neri, L. Educational Mismatch of Graduates: A Multidimensional and Fuzzy Indicator. Soc. Indic Res. 2011, 103, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betti, G.; Verma, V. Fuzzy measures of the incidence of relative poverty and deprivation: A multi-dimensional perspective. Stat. Methods Appl. 2008, 17, 225–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, P.A.; Adler, P. Observational techniques. In Handbook of Qualitative Research; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- López-Ridaura, S.; Masera, O.; Astier, M. Evaluating the sustainability of complex socio-environmental systems. The MESMIS framework. Ecol. Indic 2002, 2, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peano, C.; Tecco, N.; Dansero, E.; Girgenti, V.; Sottile, F. Evaluating the Sustainability in Complex Agri-Food Systems: The SAEMETH Framework. Sustainability 2015, 7, 6721–6741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtagh, F.; Legendre, P. Ward’s Hierarchical Agglomerative Clustering Method: Which Algorithms Implement Ward’s Criterion? J. Classif. 2014, 31, 274–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ProEcuador. Análisis Sectorial de Cacao y Elaborados. Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores Comercio e Integración Dirección de Inteligencia Comercial e Inversiones. Available online: http://www.proecuador.gob.ec/pubs/analisis-sector-cacao-2013/ (accessed on 15 December 2014). (In Spanish)

- Carrasco, C.; Domínguez, M. Género y usos del tiempo: Nuevos enfoques metodológicos. Rev. Econ. Crít. 2010, 1, 129–152. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Deere, C.; León, M. Género, Propiedad y Empoderamiento: Tierra, Estado y Mercado en América Latina; Tercer Mundo Editores: Bogotá, Colombia, 2000. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Deere, C.; Twyman, J. Asset Ownership and Egalitarian Decision-making in Dual-headed Households in Ecuador. Rev. Radic. Political Econ. 2012, 44, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, B. A Field of One’s Own. In Gender and Land Rights in South Asia; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Coria, C. El Sexo Oculto del Dinero; Grupo Editor Latinoamericano; Colección Controversia: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1986. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization. Mirando Hacia Beijing 95. Mujeres Rurales en América Latina y el Caribe. Situación, Perspectivas, Propuestas. Available online: http://www.fao.org/docrep/x0248s/x0248s00.HTM (accessed on 15 April 2015). (In Spanish)

- Starkey, P.; Ellis, S.; Hine, J.; Ternell, A. Improving Rural Mobility: Options for Developing Motorized and Non-Motorized Transport in Rural Areas; Technical Paper 525; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ragasa, C.; Sengupta, D.; Osorio, M.; Ourabah Haddad, N.; Mathieson, K. Gender-Specific Approaches and Rural Institutions for Improving Access to and Adoption of Technological Innovation; FAO: Roma, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Camps, V. El siglo de Las Mujeres; Cátedra: Madrid, Spain, 1998. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Gasson, R. Changing gender roles. A workshop report. Soc. Rural. 1988, 28, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbo, L. La doppia presenza. Inchiesta 1978, 32, 3–11. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Lagarde, M. Claves Feministas Para la Autoestima de Las Mujeres; Cuadernos Inacabados, 39; Horas y Horas: Madrid, Spain, 2000. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Szalai, A. The Use of Time: Daily Activities of Urban and Suburban Populations in Twelve Countries; Mouton: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Benería, L. Accounting for women’s work: The progress of two decades. World Dev. 1992, 20, 1547–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, C. Gender planning in the Third World: Meeting practical and strategic gender needs. World Dev. 1989, 17, 1799–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, E. Relación entre la autoestima personal, la autoestima colectiva y la participación en la comunidad. An. Psicol. 1999, 15, 251–260. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Zaldaña, C. La Unión Hace el Poder. Procesos de Participación y Empoderamiento; Unión Mundial para la Naturaleza, Fundación Arias para la Paz y el Progreso Humano: San José, Costa Rica, 1999. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Cárcamo, T.; Jazíbi, N.; Vázquez, V.; Zapata, E.; Beutelspacher, N. Género, trabajo y organización. Mujeres cafetaleras de la Unión de Productores Orgánicos San Isidro Siltepec, Chiapas. Estud. Soc. 2010, 36, 156–176. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Zapata, E.; Vázquez, V.; Alberti, P.; Pérez, E.; López, J.; Flores, A.; Hidalgo, N.; Garza, L. Microfinanciamiento y Empoderamiento de Mujeres Rurales. Las Cajas de Ahorro y Crédito en México; Plaza y Valdés: Colonia San Rafael, México, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Development as Freedom; Anchor: New York, NY, USA, 1999. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Paredes, J. Hilando Fino Desde el Feminism Comunitario; Mujeres Creando Comunidad CEDEC: La Paz, Bolivia, 2013. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Bezner Kerr, R.; Snapp, S.S.; Chirwa, M.; Shumba, L.; Msachi, R. Participatory Research on Legume Diversification with Malawian Smallholder Farmers for Improved Human Nutrition and Soil Fertility. Exp. Agric. 2007, 43, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Oduro, D.; Deere, C.; Catanzarite, Z. Women’s Wealth and Intimate Partner Violence: Insights from Ecuador and Ghana. Fem. Econ. 2015, 21, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler, S.; Hashemi, S.; Riley, A.; Akhter, S. Credit Programs, Patriarchy, and Men’s Violence against Women in Rural Bangladesh. Soc. Sci. Med. 1996, 43, 1729–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INEC. Relevancia de la Encuesta de uso de Tiempo. Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Censos de la República de Ecuador, 2012. Available online: http://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/documentos/web-inec/Uso_Tiempo/Presentacion_%20Principales_Resultados.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2016). (In Spanish)

- USAID (United States Agency for International Development). Property Rights and Resource Governance. Ecuador. Unit Estate Agency International Development (UDAID). Available online: http://www.usaidlandtenure.net/sites/default/files/country-profiles/full-reports/USAID_Land_Tenure_Ecuador_Profile.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2016).

- Bourdieu, P. Masculine Domination; Stanford University Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bezner Kerr, R.; Nyantakyi-Frimpong, H.; Lupafya, E.; Dakishoni, L.; SFHC Organization. Food Sovereignty, Agroecology and Resilience: Competing or Complementary Frames. International Colloquium: Global Governance/Politics, Climate Justice & Agrarian/Social Justice: Linkages and Challenges; International Institute of Social Studies (ISS): The Hague, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cramer, L.; Förch, W.; Mutie, I.; Thornton, F.K. Connecting women, connecting men: How communities and organizations interact to strengthen adaptive capacity and food security in the face of climate change. Gend. Technol. Dev. 2016, 20, 169–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, R.W.; Messerschmidt, J.W. Hegemonic Masculinity. Rethinking the Concept. Gend. Soc. 2005, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Powerful Synergies. Gender Equality, Economic Development and Evironmmental Sustainability. United Nations Development Programme, 2012. Available online: http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/librarypage/womens-empowerment/powerful-synergies.html (accessed on 1 November 2016).

- United Nations. World Survey on the Role of Women in Development 2014. Gender Equality and Sustainable Development. 2014. Available online: http://www.unwomen.org/~/media/headquarters/attachments/sections/library/publications/2014/unwomen_surveyreport_advance_16oct.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2016).

- Pontón, J. El trabajo femenino es sólo ayuda: Relaciones de género en el ciclo productivo de cacao. In Descorriendo Velos en las Ciencias Sociales: Estudios sobres mujeres y ambiente en el Ecuador; María Cuvi, M., Poats, S., Calderón, M., Eds.; Ecociencia, Abyayala: Quito, Ecuador, 2006. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Ian Fitzpatrick. From the Roots up. How Agroecology Can Feed Africa. Global Justice Now, 2015. Available online: http://www.globaljustice.org.uk/sites/default/files/files/resources/agroecology-report-from-the-roots-up-web-version.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2016).

- Camarero, L. La Población Rural en España, de Los Desequilibrios a la Sostenibilidad Social; Fundación “La Caixa”: Barcelona, Spain, 2009. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco, C. La Sostenibilidad de la Vida Humana: ¿un Asunto de Mujeres? Mientras Tanto 2001, 82, 43–70. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).