Abstract

Lignin, an abundant and renewable biopolymer, holds significant potential for asphalt modification owing to its unique aromatic structure and reactive functional groups. This review summarizes the main lignin preparation routes and key physicochemical attributes and assesses its applicability for enhancing asphalt performance. The physical incorporation of lignin strengthens the asphalt matrix, improving its viscoelastic properties and resistance to oxidative degradation. These enhancements are mainly attributed to the cross-linking effect of lignin’s polymer chains and the antioxidant capacity of its phenolic hydroxyl groups, which act as free-radical scavengers. At the mixture level, lignin-modified asphalt (LMA) exhibits improved aggregate bonding, leading to enhanced dynamic stability, fatigue resistance, and moisture resilience. Nevertheless, excessive lignin content can have a negative impact on low-temperature ductility and fatigue resistance at intermediate temperatures. This necessitates careful dosage optimization or composite modification with softeners or flexible fibers. Mechanistically, lignin disperses within the asphalt, where its polar groups adsorb onto lighter components to boost high-temperature performance, while its strong interaction with asphaltenes alleviates water-induced damage. Furthermore, life cycle assessment (LCA) studies indicate that lignin integration can substantially reduce or even offset greenhouse gas emissions through bio-based carbon storage. However, the magnitude of the benefit is highly sensitive to lignin production routes, allocation rules, and recycling scenarios. Although the laboratory research results are encouraging, there is a lack of large-scale road tests on LMA. There is also a lack of systematic research on the specific mechanism of how it interacts with asphalt components and changes the asphalt structure at the molecular level. In the future, long-term service-road engineering tests can be designed and implemented to verify the comprehensive performance of LMA under different climates and traffic grades. By using molecular dynamics simulation technology, a complex molecular model containing the four major components of asphalt and lignin can be constructed to study their interaction mechanism at the microscopic level.

1. Introduction

Given the rising global energy requirements and the heightened focus on sustainability, the exploration and implementation of renewable resources are gaining increasing importance [1,2]. Biomass materials have emerged as a significant research and application focus in recent years, attributed to their extensive availability, cost-effectiveness, and renewability. They are increasingly being employed as substitutes for conventional petroleum-based industrial raw materials, aiming to decrease energy consumption and enhance ecological sustainability. Lignin, a natural polyphenolic polymer, has garnered considerable attention in the field of asphalt modification over the past few years [3]. As the most abundant biopolymer in the wood industry’s by-products, lignin accounts for roughly 20% to 25% of the dry weight of each plant. The overall quantity of lignin in the biosphere is over 300 billion tons and is growing at an approximate annual rate of 20 billion tons [4]. As a key structural element in plant cell walls, lignin is abundant in nature and biodegradable, making it a promising sustainable material option. Scientific exploration into its functional applicability within polymer composites spans over four decades, demonstrating progressive technological maturation. For a long time, polymer scientists have been highly attracted to it due to its extensive availability, aromatic structure, and the diverse modification potentials offered by its chemical properties [5].

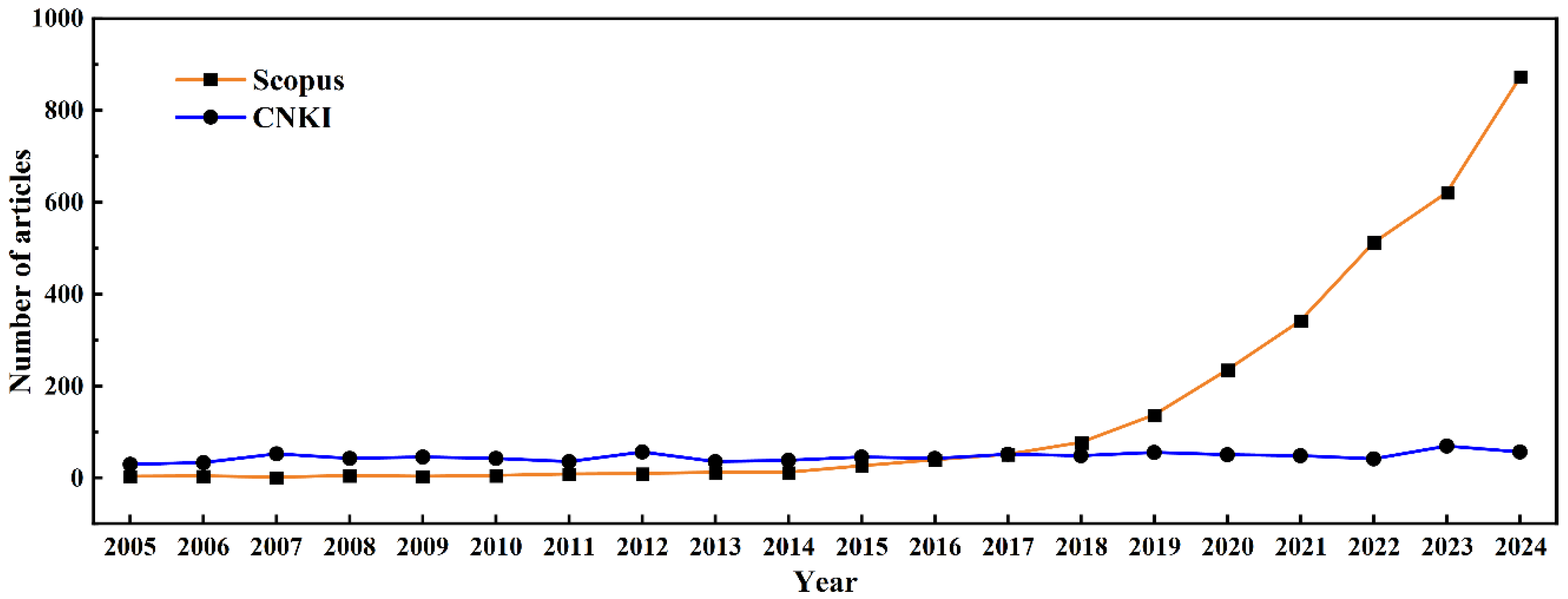

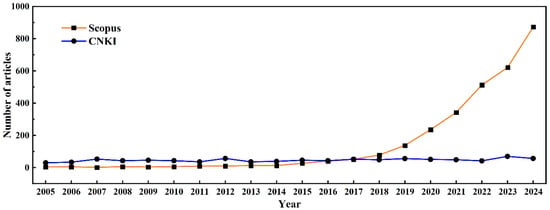

The quantity of published articles over time discloses the development tendency within a domain. Consequently, the annual number of articles regarding lignin-modified asphalt published in the CNKI and Scopus databases was collated, and a dot-line graph was plotted to analyze the trend in this field. As depicted in Figure 1, it represents the publication volume of articles related to lignin-modified asphalt in the CNKI and Scopus databases from 2005 to 2024. From 2005 to 2017, the quantity of publications in both databases was relatively low and remained stable, which suggests that research activity in this domain was level during that period. The number of CNKI publications was generally slightly higher than that of Scopus until 2017. Since 2018, the Scopus database has witnessed a significant growth in the volume of publications, indicating that the related field has been gaining increasing global attention. Although the number of CNKI publications also rose, the growth rate was relatively small, which might reflect that the research activities in this field in China were relatively stable or the research focus shifted. China possesses colossal market demand and development potential in infrastructure construction and material research and development. Research teams should intensify international cooperation, elevate the research level, and actively promote research outcomes to the international market to augment their international influence in this field.

Figure 1.

Number of published articles related to lignin-modified bitumen appearing in the CNKI and Scopus databases from 2005 to 2024.

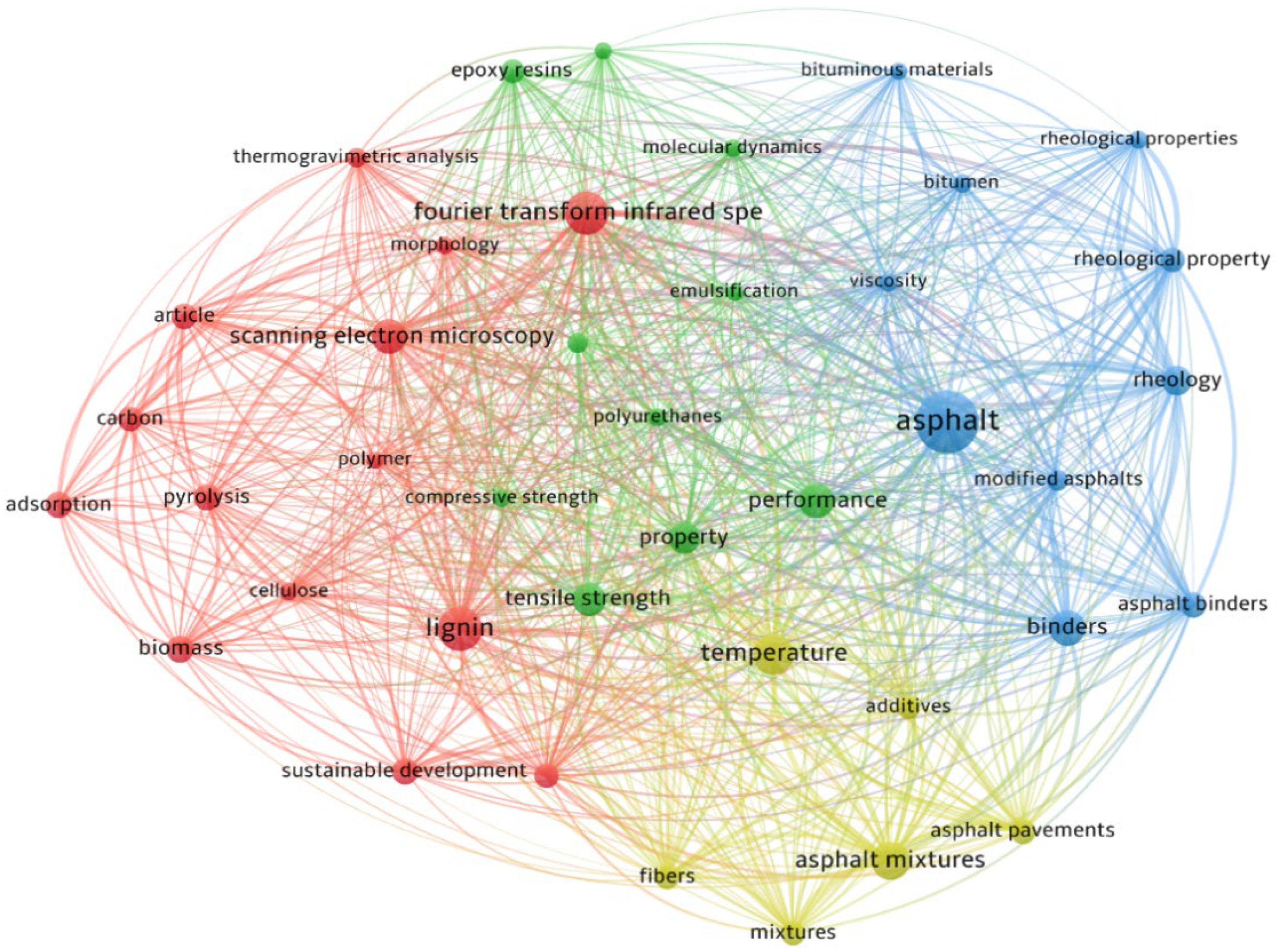

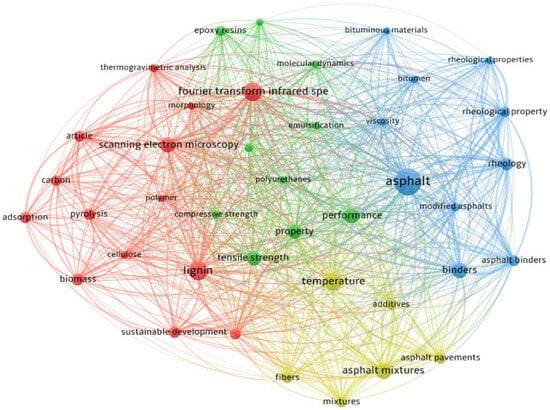

The VOSviewer_1.6.20 was employed to analyze the articles and authors concerning lignin-modified asphalt in the Scopus database from 2005 to 2024. Keywords that occurred more than 100 times were chosen, and the analysis outcomes are presented in Figure 2. In the figure, the nodes represent the keywords, and their magnitudes are correlated with the frequency of the keyword’s occurrence in the research literature. The connecting lines denote the relationships among these keywords. Different colored clusters indicate the distribution of research topics: the blue cluster focuses on the properties of asphalt materials and binder characteristics; the red cluster concentrates on the thermal analysis and microstructure of lignin; the green cluster involves material performance and characterization methods; and the yellow cluster is related to asphalt mixtures and additives. The dense connections among the keywords reflect the close correlations among various research orientations, suggesting that the research on lignin-modified asphalt encompasses multiple aspects ranging from molecular structure characterization to material performance evaluation, presenting a cross-disciplinary and multi-dimensional research framework. Overall, from 2005 to 2024, the research in this domain evolved toward more complex material combinations and performance appraisals, particularly those involving rheology and material performance.

Figure 2.

Network visualization of the articles on lignin-modified asphalt.

As rising traffic volumes and more stringent requirements for road performance come to the fore, the shortcomings of conventional asphalt materials have become increasingly apparent, especially when considering their behavior under elevated temperatures, their ability to resist cracking in low temperatures, and their resistance to aging [6,7]. For this reason, asphalt modification technology has become a key approach to enhancing pavement performance [8]. Currently, petroleum-based additives (such as rubber powder and PE) are the mainstream choices in the industry, but their raw materials rely on non-renewable fossil energy, and their manufacturing process demands significant energy usage and generates substantial carbon footprints [9,10]. Under the global “dual carbon” strategic backdrop, the advancement of eco-friendly and renewable bio-derived additives has become a key focus in the field of road construction materials. Among them, lignin, as a potential modifier, has garnered widespread attention [11,12]. The addition of lignin has a marked impact on improving the rheological properties of asphalt, which effectively elevates its resistance to high-temperature rutting and low-temperature cracking [13]. In lignin-modified asphalt research, multiple teams have employed diverse preparation and performance evaluation methodologies. Xu et al., 2021 [14] performed rheological, mechanical, and chemical analyses on lignin-modified asphalt, finding that incorporating lignin can substantially change asphalt’s rheological properties, rendering it more appropriate for different applications. Li et al., 2023 [15] added three types of fibers to asphalt—polypropylene, polyester, and lignin—to study the viscoelastic properties of the fiber-reinforced asphalt. Their research indicated that introducing lignin fibers significantly improves asphalt’s rutting resistance. Nahar et al., 2023 [3] explored the interaction and flow properties of asphalt enhanced with lignin as a partial substitute. Their research demonstrated that chemically processed lignin significantly boosts the thermal stability of asphalt while also enhancing its flexibility in colder conditions. Nugraha et al., 2022 [16] investigated how multi-layer plastic waste affects asphalt performance when lignin serves as a compatibilizer, discovering that lignin boosts asphalt’s compatibility and thermal stability.

The utilization of lignin in asphalt modification presents significant potential; yet, additional research and enhancements are necessary. This paper reviews the preparation techniques and physicochemical attributes of lignin, with a detailed discussion on the widely utilized kraft lignin. It analyzes the differences between dry and wet processes in producing lignin-modified asphalt and its mixtures, and explores how modified asphalt is improved in rheological behavior, temperature sensitivity, and aging resistance. Furthermore, through the evaluation of pavement performance in lignin-enhanced asphalt blends, the distinctive benefits of lignin as a sustainable, bio-derived additive are emphasized. The mechanism involves lignin mitigating asphalt aging through two primary ways: forming a physical filling network and scavenging free radicals. Finally, taking a whole life cycle view, the paper evaluates the environmental benefits of lignin-modified asphalt in reducing carbon emissions and enhancing waste resource utilization; this approach lays a theoretical groundwork for advancing eco-friendly road construction materials.

2. Preparation and Performance of Lignin

2.1. Preparation of Lignin

2.1.1. Approaches to Preparing Lignin

Lignin, a complex organic polymer naturally present in plant cell walls, is the second most plentiful biopolymer on Earth, following cellulose, and makes up around 30% of the biosphere’s organic carbon. Its main sources are wood and various agricultural by-products such as rice straw, corn stover, and sugarcane bagasse [17,18,19,20]. Typically, lignin existing in wood can be efficiently extracted using chemical or biological methods. Chemical methods encompass acid hydrolysis, alkaline hydrolysis, etc., whereas biological methods employ microorganisms or enzymes for degradation and separation [21].

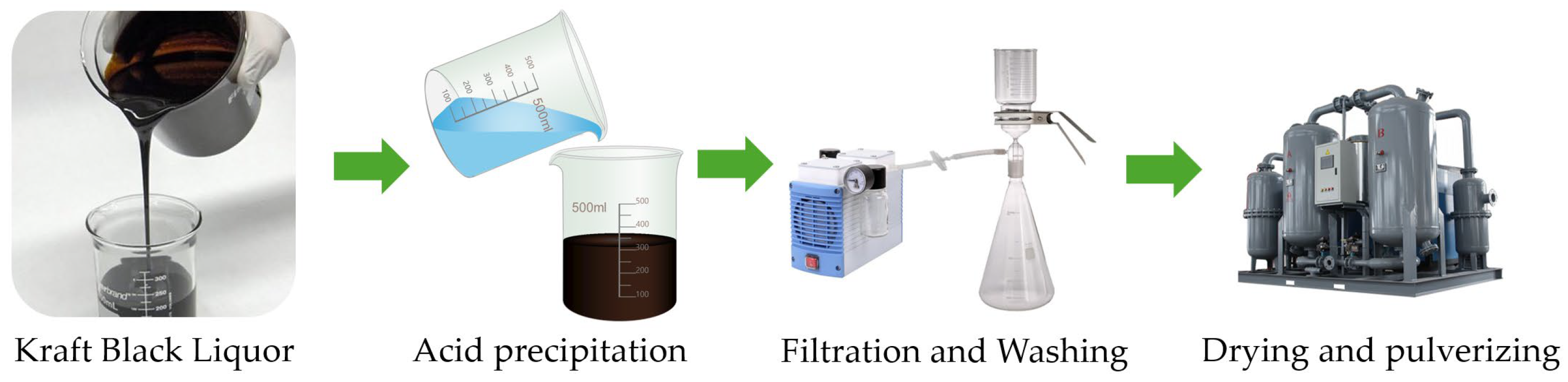

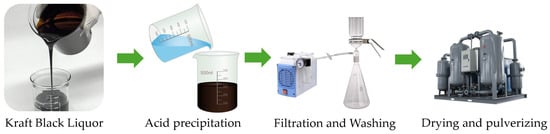

In road construction, lignin used in asphalt often comes from waste materials generated by the paper and pulp sector [22]. The alkaline pulping process (kraft method) is currently the most extensively employed approach for lignin preparation. Lignin can be released from plant fibers by disrupting the ester and ether bonds connecting it to hemicellulose. This method generally employs a sodium hydroxide and sodium sulfide alkaline solution, heated to temperatures between 150 and 170 degrees Celsius [23]. The black liquor generated by the sulfate method has its pH adjusted to precipitate lignin and is then subjected to drying treatment. This method features a mature process, is capable of large-scale production, and offers lignin of relatively high purity that retains the aromatic structure, facilitating asphalt modification [24]. The process flow is depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Process flow of lignin preparation by the kraft method.

- Black liquor collection: In the pulp and paper sector, the sulfate method generates significant quantities of black liquor, serving as the primary lignin source.

- Acid precipitation: Heat the black liquor to 50–70 °C and gradually incorporate dilute sulfuric acid or hydrochloric acid to adjust the pH to approximately 2. Under acidic conditions, lignin precipitates from the black liquor and forms sediment.

- Filtration and washing: Utilize a vacuum filtration apparatus to separate the precipitated lignin. Wash the lignin with water to eliminate residual inorganic salts and other impurities.

- Drying and pulverizing: Dry the lignin precipitate to a constant weight and employ mechanical grinding equipment to process it into granular or powdered products.

In addition to the kraft method, fast pyrolysis is also an effective method for extracting lignin. Through subjecting wood or agricultural residues to rapid pyrolysis at elevated temperatures, lignin and other by-products can be acquired [25,26]. Fast pyrolysis not only facilitates the extraction of lignin but also generates other valuable chemicals, offering potential for the diverse applications of lignin [27]. Organic solvent extraction, enzymatic extraction, and supercritical fluid extraction are also methods used for extracting lignin [28]. Horst et al., 2015 [29] studied lignin from various sources and its different extraction methods and found that the particle size of lignin is significantly affected by the extraction approach, which in turn has a more pronounced impact on its final performance. Arafat et al., 2019 [30] found that lignin extracted from rice husks via deep eutectic solvents can increase asphalt’s resistance to permanent deformation and cracking, preserve more non-polar components, and boost its viscoelastic balance. In modified asphalt applications, the choice of extraction method must align with specific requirements. Studies indicate that using formic acid or the supercritical water cracking method is preferable for improving resistance to high-temperature deformation and fatigue [29,31]. If emphasis is placed on cost control, traditional methods such as the sulfate process can be taken into consideration [12]. Table 1 delineates the preparation processes, principal characteristics, and key performance metrics of major lignin types in asphalt systems as documented in the current research, offering clear guidance for the targeted selection of lignin-based modifiers.

Table 1.

Preparation processes, characteristics, and performance in asphalt of different lignins.

2.1.2. Modification of Lignin

By chemically modifying lignin, its compatibility and dispersion with base asphalt can be improved, which upgrades the performance of modified asphalt. Commonly seen modification approaches involve hydroxylation modification, epoxidation modification, halogenated hydrocarbon modification, and so on. Xie et al., 2024 [36] indicated that through surface modification of lignin, such as acid–base treatment, the hydrophilic groups on its surface can be partially removed, enhancing its compatibility with asphalt, yet exerting a relatively small influence on low-temperature performance. Via chemical modification, the steric hindrance effect of benzene rings in lignin was decreased and the reactivity of functional groups within lignin was elevated, facilitating its interaction with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in asphalt [37]. During the ammonolysis reaction, Zheng et al., 2024 [38] employed alkaline-catalyzed hydrolysis to break down high-molecular-weight lignin into smaller fragments. This process not only decreased the average molecular weight from 45,605 g/mol to 45,358 g/mol but also reduced the content of high-molecular-weight components. Ma and Zhang, 2022 [39] discovered that after fractionation of the lignin from wheatgrass, the yield in the low-molecular-weight range (such as dimers and trimers) increased significantly, thereby influencing its hydrophobicity and surface charge. He et al., 2023 [40] utilized pine-derived lignin particles for conventional asphalt modification, processing the sustainable binder with 4500 rpm mechanical shearing under 165 °C thermal conditions. Tamrin et al., 2023 [41] incorporated 4,4′-diphenylmethane diisocyanate (MDI) into lignin and added asphalt prior to the hardening of the mixture to obtain modified asphalt. Optimized asphalt performance was observed across mechanical strength, material stability, and thermal behavior, concurrent with amino-grafted lignin demonstrating amplified catalytic activity and bitumen affinity [42]. Xu et al., 2011 [43] produced amine-modified enzymatic hydrolyzed lignin (EHLA) through a Mannich reaction between EHL, formaldehyde, and triethylenetetramine (TETA), forming a high-performance slow-setting cationic asphalt emulsifier. Ren et al., 2020 [44] prepared oxygen-propylated lignin (OL) using lignin and propylene oxide. Then, they synthesized esterified lignin (OEL) from OL and lauric acid under the catalysis of tetrabutyl titanate. The esterified lignin (OEL) was used for asphalt modification.

2.2. Structural Characteristics of Lignin

2.2.1. Microcomposition of Lignin

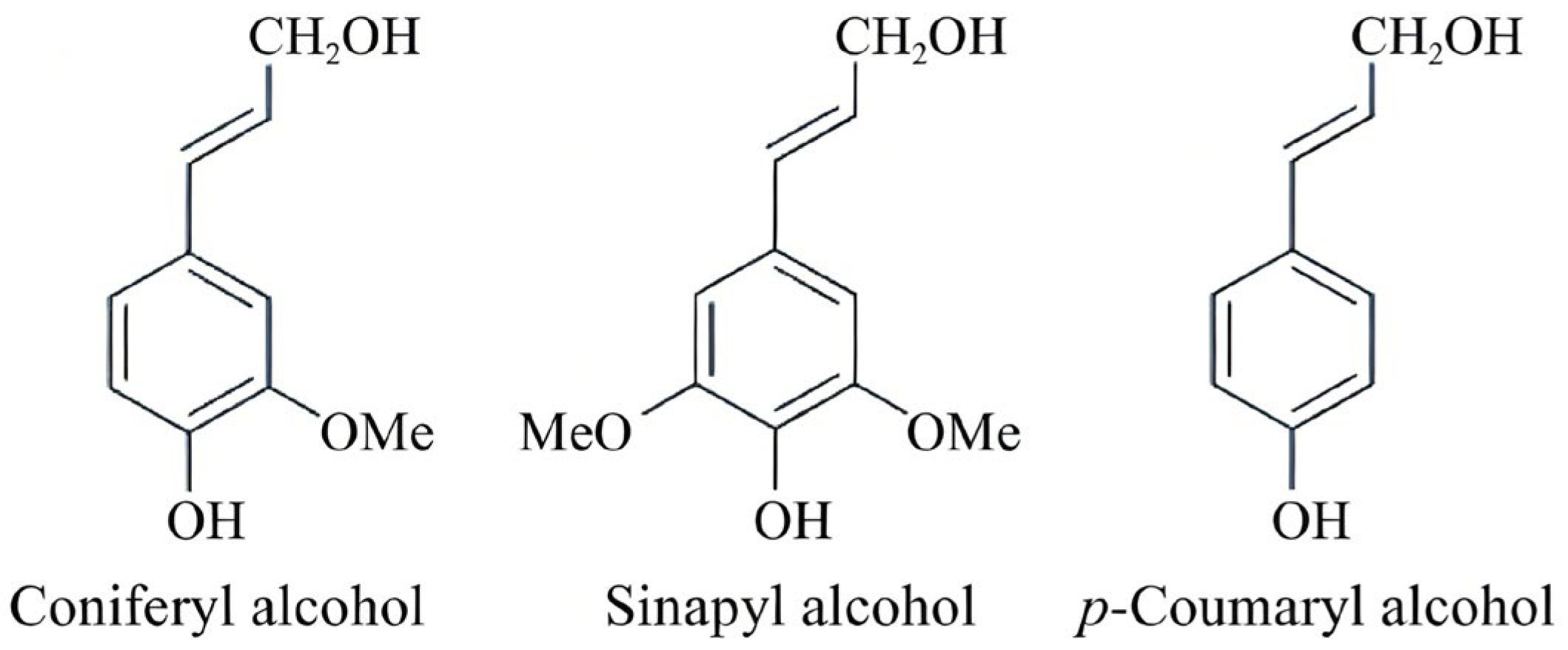

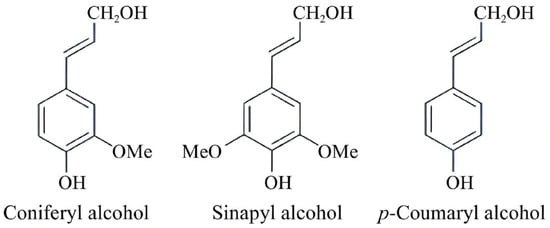

As a polyphenolic macromolecule, lignin’s architectural framework is constructed from three hydroxycinnamyl alcohol derivatives: p-coumaryl, coniferyl, and sinapyl alcohols, as depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The three main monomer structures of lignin.

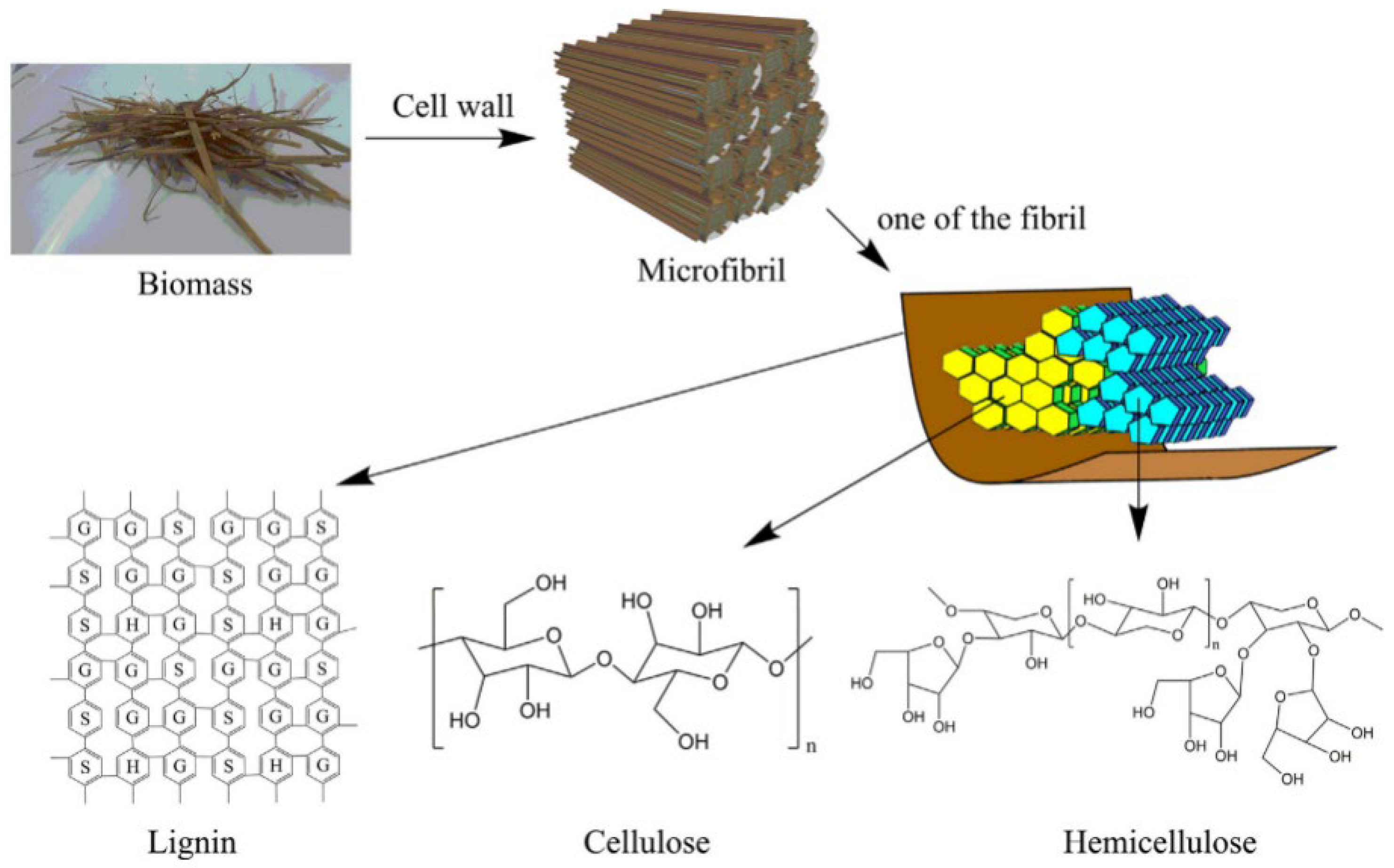

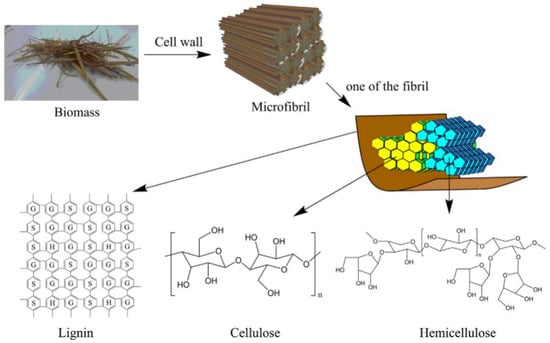

Higher plants can form highly crystalline cellulose microfibrillar structures. Each microfibril is constituted by 30–40 fully extended linear cellulose chains arranged in parallel, with a width of approximately 3 nanometers, being the second smallest-width structural unit next to a single cellulose chain. Plant cell walls are filled with these hemicellulose and lignocellulose microfibrils, forming natural nanocomposites [45,46]. In lignocellulose, lignin is interspersed in a three-dimensional reticular structure and closely cross-links cellulose and hemicellulose through ether and ester bonds, as depicted in Figure 5 [21].

Figure 5.

Lignocellulose in biomass and its composition [21].

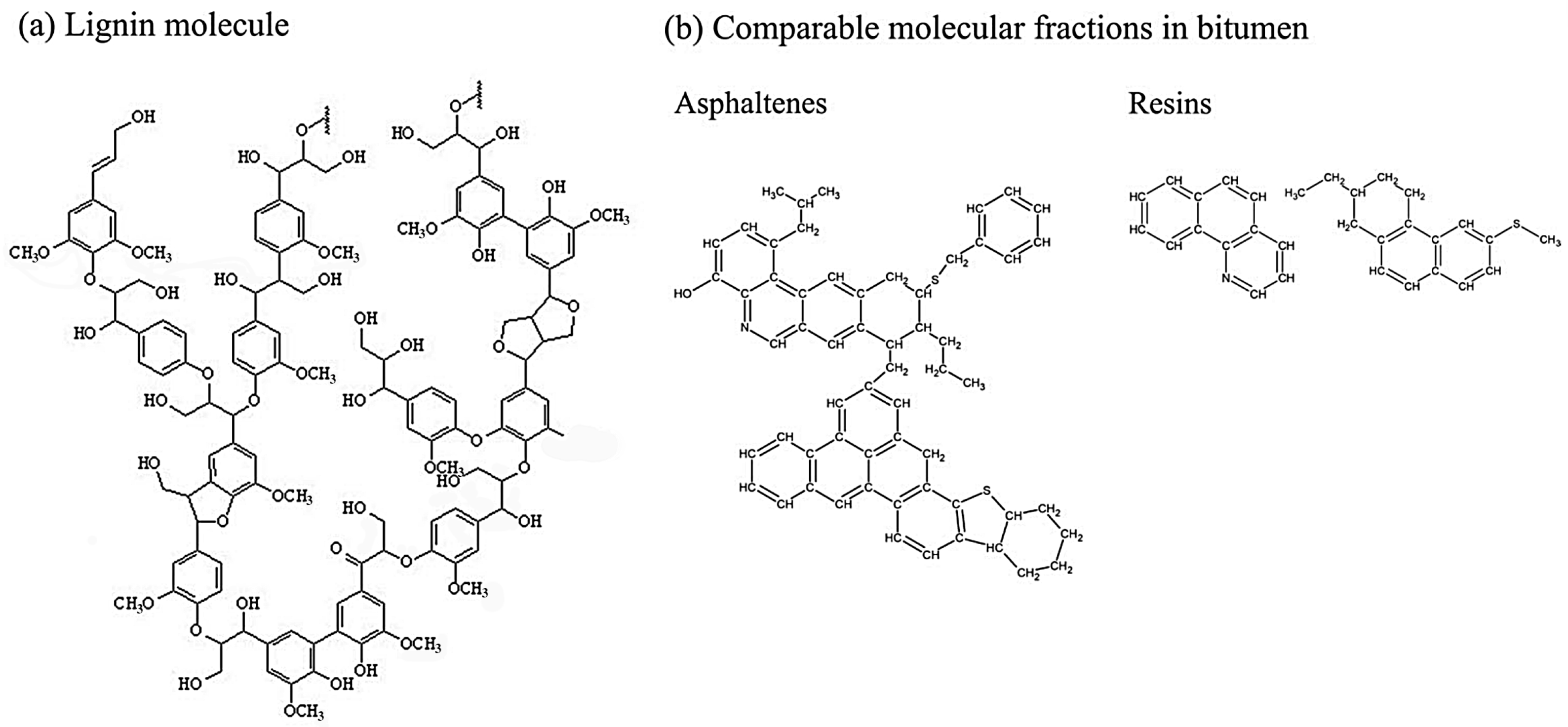

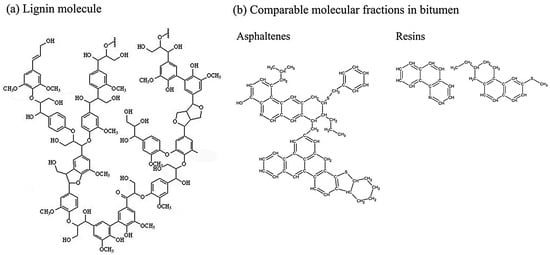

Lignin’s molecular architecture exhibits structural heterogeneity with multiple oxygen-containing moieties, notably alcoholic hydroxyls (-OH), methoxyl (-OCH3) substituents, ketonic carbonyls (C=O), and carboxylic acid (-COOH) functionalities. These functional groups endow lignin with distinctive chemical reactivity and physical characteristics [3]. The existence of hydroxyl and carboxyl groups renders lignin highly polar and hydrophilic, whereas the presence of methoxy groups enhances its hydrophobicity and thermal stability, which is beneficial for improving the durability and anti-aging capability of asphalt [20]. In asphalt modification, these structural features of lignin enable it to engage in multiple chemical and physical interactions with the components in asphalt, thereby improving asphalt properties [47,48]. Compared with similar molecular components in asphalt, as depicted in Figure 6, lignin is more abundant in hydroxyl groups, and it can undergo chemical modification to induce better compatibility with asphalt [3]. Using lignin as a compatibilizer can significantly improve the interfacial affinity of waste plastics with asphalt, which in turn improves the overall performance of the modified asphalt [16].

Figure 6.

Chemical characterization of lignin moieties and asphalt constituents: (a) lignin-based functional elements, (b) bitumen-derived components (asphaltenes/resins).

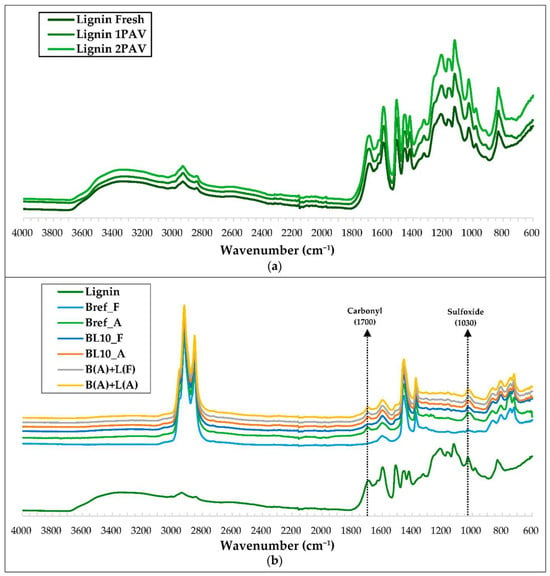

2.2.2. FTIR Analysis

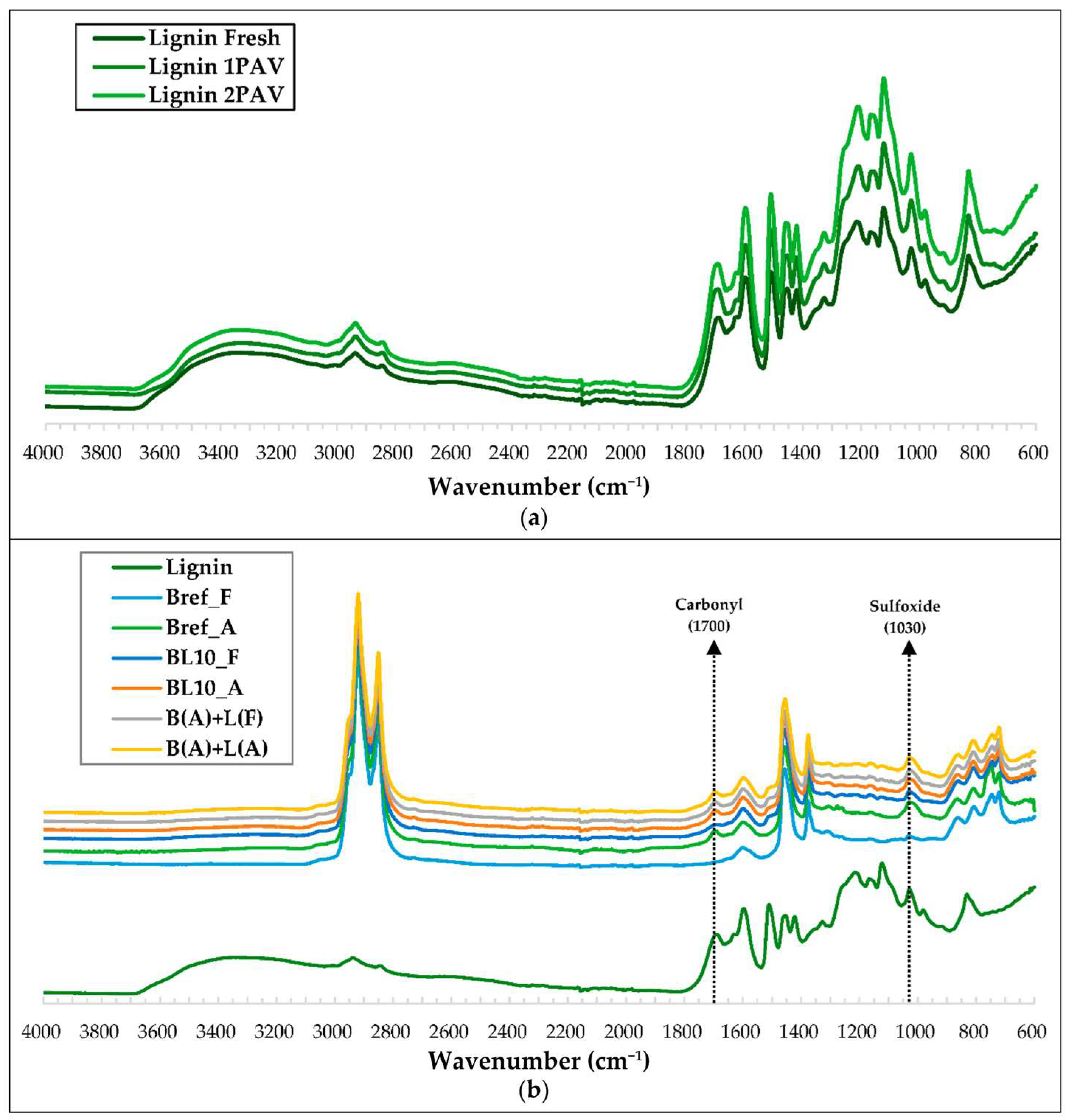

FTIR can identify the principal chemical functional groups in asphalt, such as components like aromatics, alkanes, and phenols, thereby facilitating the study of its chemical characteristics and structure. It is extensively applied in the detection and analysis of asphalt binders [49]. Figure 7 presents the spectral evolution of lignin under aging protocols compared with virgin samples, bitumen, and their composites. The hydroxyl band (3420 cm−1) attenuation in Figure 8a originates from combined moisture loss and hydroxide consumption during initial-stage degradation, contrasted by progressive carbonyl (1708 cm−1) intensification through oxidative mechanisms. Crucially, Figure 8b demonstrates spectral fidelity in lignin-bitumen blends without emergent absorption signatures [4].

Figure 7.

FTIR analysis of (a) lignocellulosic aging profiles across degradation stages and (b) compositional matrices: native lignin, neat bitumen, and lignin–bitumen composites [4].

Figure 8.

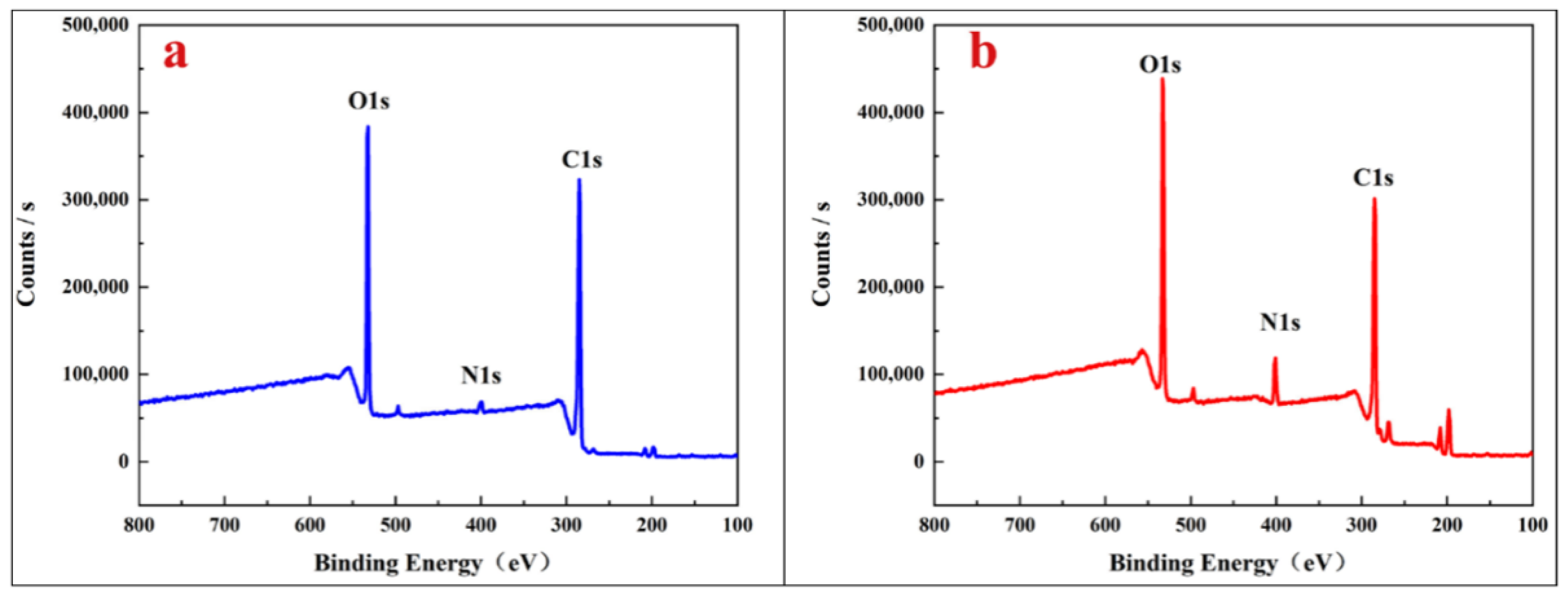

XPS broad-scan spectra of the untreated lignin (a) and amine-modified lignin (b) [38].

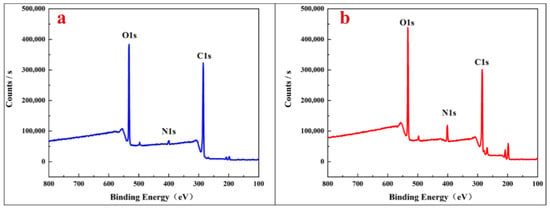

2.2.3. XPS Analysis

XPS is used to analyze the synergistic interaction between lignin and other components at the nanoscale level. Nevertheless, the treatment approaches of lignin in diverse studies may influence the detection outcomes of XPS. Zheng et al., 2024 [38] performed XPS analysis on the pristine lignin and aminated lignin. As depicted in Figure 8, both untreated lignin and its aminated counterpart exhibit substantial amounts of elements such as C and O. In contrast, the spectral signature associated with nitrogen atoms in the aminated lignin stands out markedly. Through comparing the C/N ratios of the two, it was discovered that the C/N ratio of the lignin raw material is 30.59, while that of the aminated lignin reduces to 9.19, suggesting that amino groups were successfully incorporated into the lignin, resulting in elevated nitrogen levels.

2.3. Performance of Lignin

2.3.1. Physical Properties

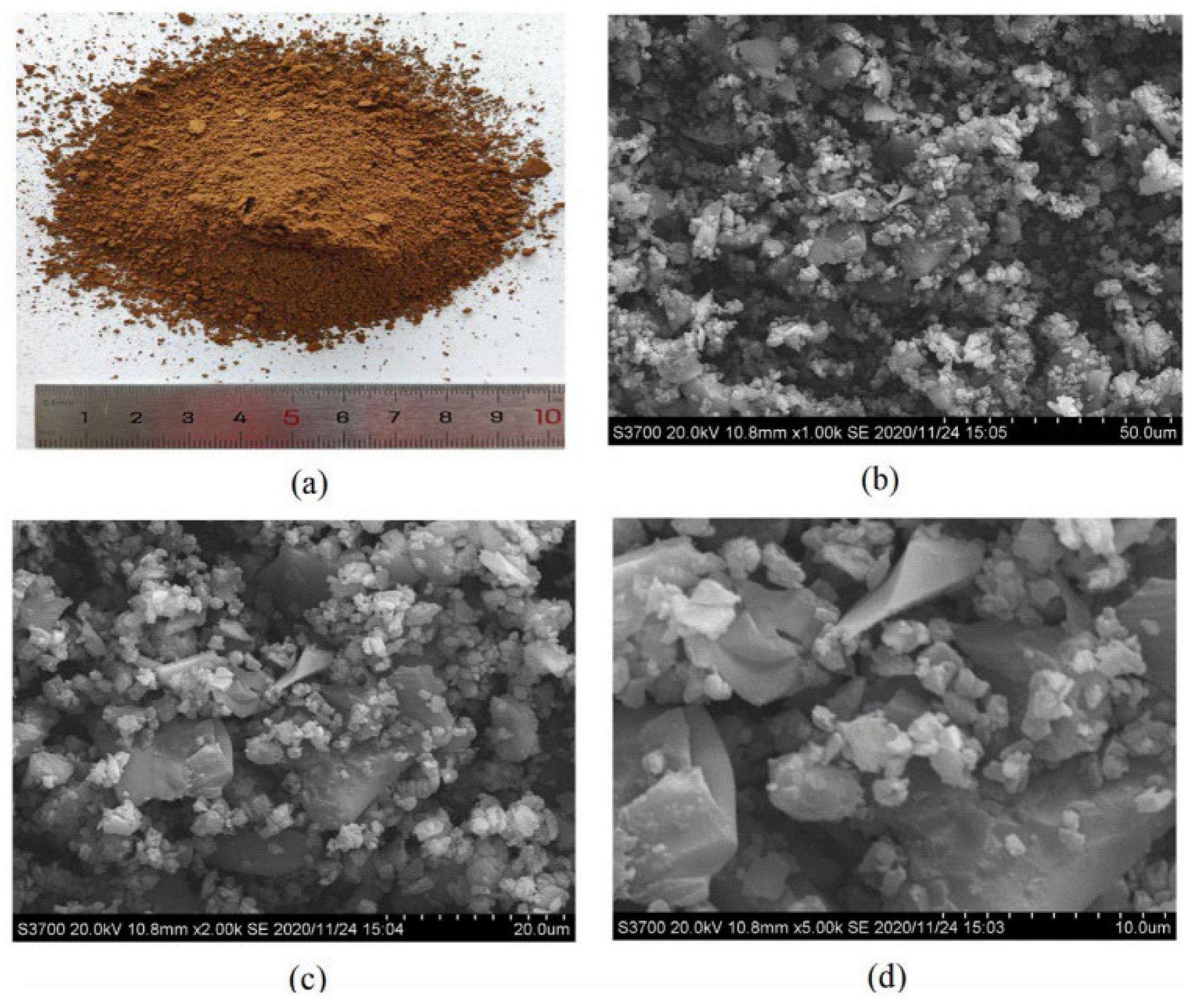

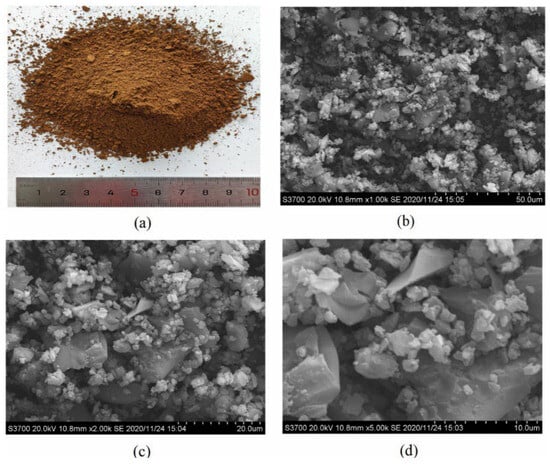

Table 2 presents the fundamental properties of kraft lignin utilized in asphalt modification. The structural features of lignin at both macro and micro scales, observed through SEM, are shown in Figure 9 [50]. SEM images show that the surface of lignin particles is usually rough and uneven, with concave and convex textures. This rough surface feature is conducive to forming mechanical interlocking in modified asphalt, increasing the adhesion and rutting resistance of the asphalt [13].

Table 2.

Fundamental properties of kraft lignin.

Figure 9.

Morphological analysis of lignin: (a) soda lignin (SL); (b) SL observed at 1000× magnification in SEM; (c) SL at 2000× magnification; (d) SL at 5000× magnification [50].

Lignin typically exhibits a brown or dark brown color, mainly because of the polyphenolic structure and conjugated system therein. Lignin cannot be dissolved in water but is partially soluble in alkaline solutions and some organic solvents (e.g., dimethyl sulfoxide, ethanolamine, and some ionic liquids). Lignin possesses high thermal stability and typically commences thermal decomposition within the range of 200 °C to 400 °C. This characteristic allows lignin to be utilized at elevated temperatures without facile degradation. Owing to its complex structure and cross-linking properties, lignin is relatively brittle in the pure state; however, it can offer additional strength and rigidity in composite materials [51]. Lignin exhibits a certain degree of hygroscopicity, but it is significantly lower than that of cellulose, thereby enabling it to withstand to a certain extent the impact of moisture [52].

Lipophilicity, to a certain extent, can represent the extent of combination with asphalt. This affects how well lignin can be mixed with and spread in the base asphalt, which determines how good the modification result will be. Lignin’s chemical structure, which has parts such as aromatic rings and hydrophobic groups, is like that of asphalt’s chemical framework. This resemblance allows lignin to serve as an effective additive for improving the viscoelasticity, anti-aging properties, and environmental performance of asphalt [53,54].

2.3.2. Chemical Properties

The chemical behavior of lignin is defined primarily by the reactivity of the benzene rings and the functional groups located within the side chains [55]. The oxidation of benzene rings constitutes an important pathway for lignin degradation. Research has shown that the oxidation of nitrobenzene can transform lignin into aromatic aldehyde products (such as vanillin); however, the by-products are complex and the recovery of oxidants proves challenging [56]. During oxidative degradation, Pt promotes β-O-4 bond cleavage while enhancing condensation reactions, elevating the yield of aromatic aldehydes from 3.4% to 7.7% [57]. The side-chain hydroxyl groups in lignin are susceptible to modification through alkylation or esterification. The γ-hydroxy benzoylation reaction can esterify the γ-hydroxyl groups of the side chains to form free phenolic derivatives. Such structures exist stably in palm lignin and are readily separable [58]. Under acidic conditions, the hydroxyl groups or the oxygen atoms of the ether bonds on the benzene ring might be protonated, forming positively charged intermediates. This results in decreased electron density surrounding the neighboring carbon atoms, making them more vulnerable to attack by nucleophilic oxidants. The methoxy groups are prone to hydrolysis under acidic conditions (such as H+-catalyzed demethylation), converting into free hydroxyl groups and providing precursors for subsequent ortho oxidation. For example, after the removal of the methoxy groups of G-type lignin, the ortho positions are more prone to further oxidation to generate catechol [59]. The lignin derived from nutshells is rich in phenolic hydroxyl groups and conjugated structures, exhibiting excellent antioxidant capacity and ultraviolet absorption characteristics, and can be employed in cosmetics and sunscreens [60]. Lignin demonstrates distinct acid–base properties under varying conditions. For example, kraft lignin typically exhibits basicity, whereas soda lignin, which is sulfur-free, is also basic; lignosulphonate and organosolv lignin are acidic, while hydrolysis and SE lignin are neutral or weakly acidic [61].

3. Preparation of Lignin-Modified Asphalt and Its Mixture

3.1. Preparation of Lignin-Modified Asphalt

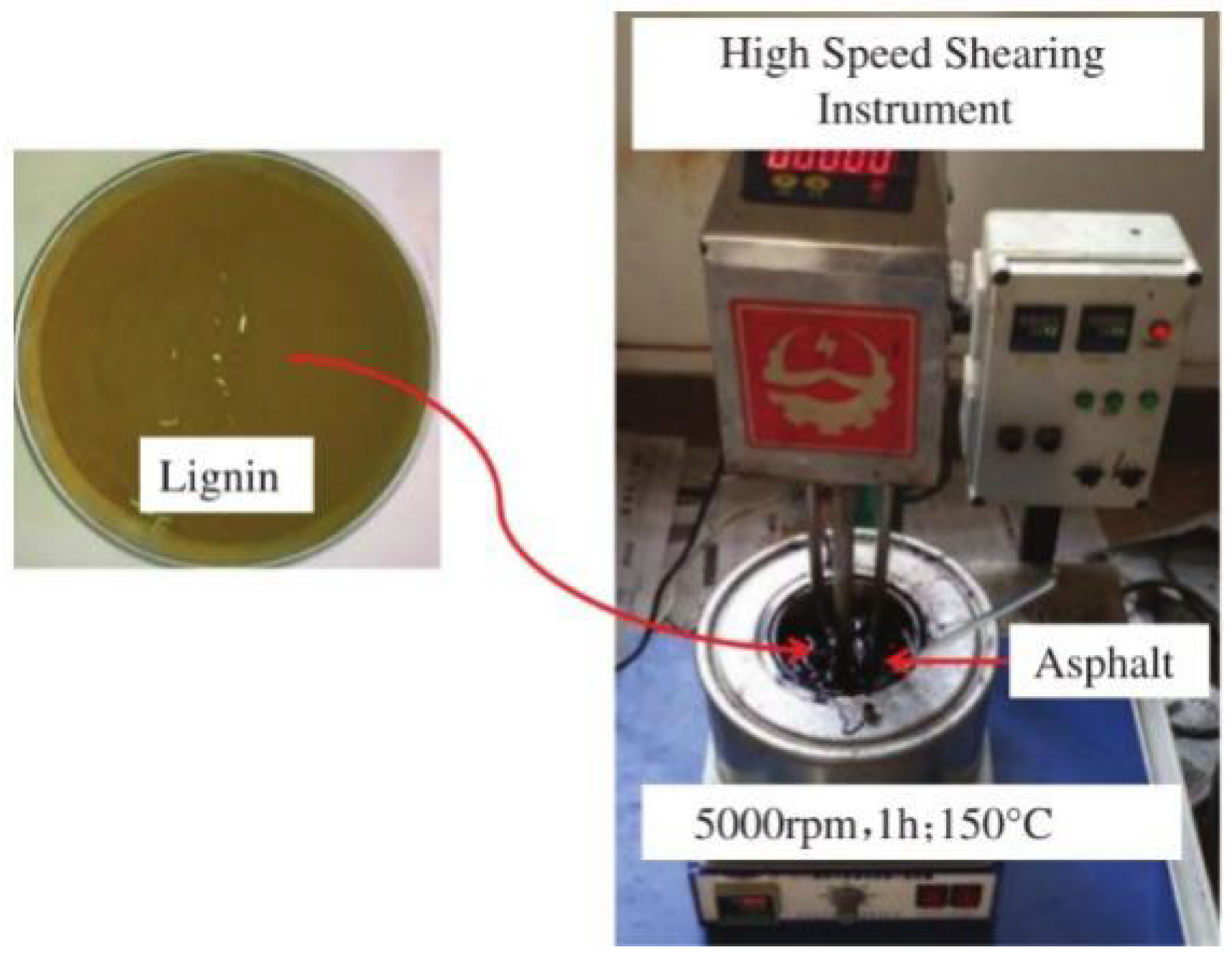

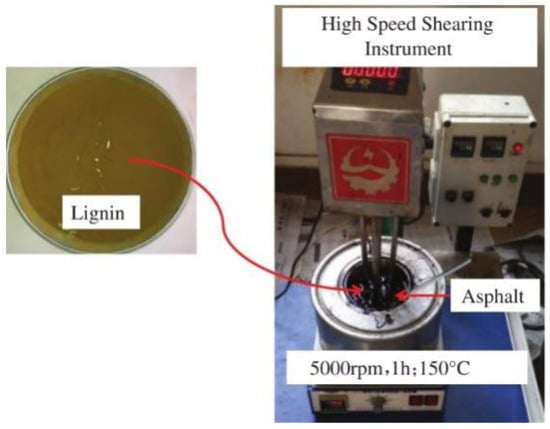

Lignin is typically directly mixed with asphalt. The shear rate and temperature are controlled to enable lignin to be fully immersed in the asphalt. Following temperature maintenance for a predetermined duration and cooling, modified asphalt is acquired, as evidenced in Figure 10 [62,63]. The modification of asphalt by lignin via the physical blending method is mainly accomplished by increasing the viscosity of asphalt. Within asphalt matrices, the high molecular weight characteristic of lignin promotes three-dimensional network development, consequently boosting viscosity and the elastic modulus [22]. This method is operationally facile and applicable for large-scale production. The dosage of lignin, the speed of shear-stirring, the mixing temperature, and the mixing duration exert considerable influence on the modification efficacy of asphalt. A retrieval of relevant literature indicates that, as presented in Table 3, there exist considerable discrepancies among different researchers regarding the mixing conditions of lignin and asphalt [13]. Rezazad Gohari et al., 2023 [63] investigated the effects of varying mixing parameters on the physicochemical characteristics of asphalt modified with lignin. Their research utilized two mechanical agitation apparatuses (mechanical stirrer and high-shear stirrer) to blend 5%, 10%, and 20% kraft lignin with PG 58S-28 asphalt at speeds of 1000 rpm and 5000 rpm, respectively. FTIR analysis failed to detect the emergence of new functional groups in the lignin, whereas ESEM and SEM analyses demonstrated that the lignin content and mixing conditions influenced the fibrous structure of the asphalt. Brasil et al., 2024 [64] subjected lignin to ultraviolet irradiation, which could induce free radical polymerization. Following this, hydrothermal carbonization was performed in an autoclave to promote aromatic ring condensation, resulting in lignin-derived nanocarbon production. The asphalt was modified with these lignin-based nanocarbons. The lignin vitrimer (ELV) was synthesized through a reaction between thermosetting epoxy resin derived from lignin (LER) and carboxylated lignin (EL-COOH), catalyzed by Zn2+ ions. Then, ELV was physically co-mixed with matrix asphalt to generate lignin-based epoxy asphalt (ELEA) [65]. He et al., 2022 [66] produced lignin-grafted layered double hydroxides (LG-g-LDHs) using layered double hydroxides. The developed materials were then utilized for asphalt modification, improving the resistance to UV-induced aging.

Figure 10.

Preparation of lignin-modified asphalt.

Table 3.

Literature review on the mixing conditions of bitumen with lignin.

3.2. Preparation of Lignin-Modified Asphalt Mixture

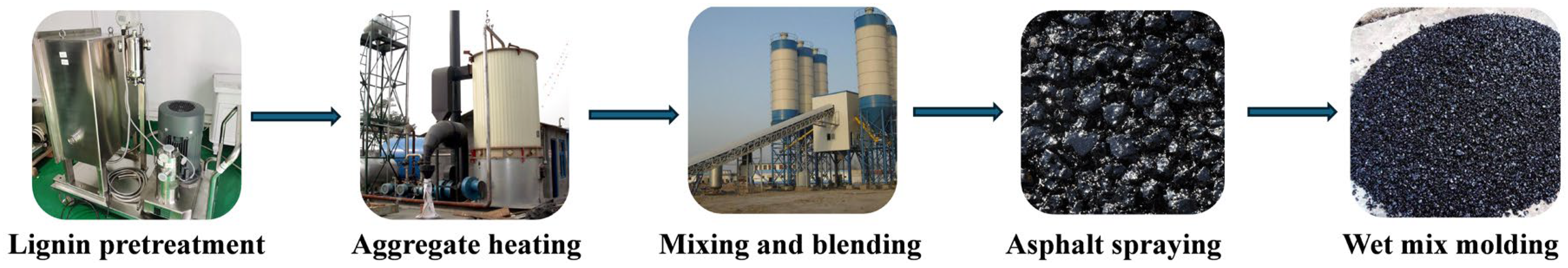

3.2.1. Dry Process

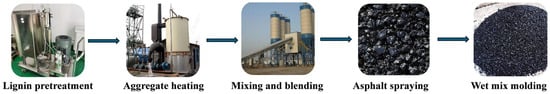

The dry process encompasses steps such as the pretreatment of lignin, heating of aggregates, dry blending and mixing, asphalt spraying, and wet mixing and shaping, as depicted in Figure 11. As part of the pretreatment, lignin is dried and ground, while the aggregates are heated to a temperature 10–15 °C above the conventional mixing temperature to offset the heat absorption of lignin [78]. After ensuring that the asphalt thoroughly moistens the aggregates, the lignin and aggregates are dry-blended, the asphalt sprayed, and finally the asphalt mixture wet-blended for shaping. The dry process involves no premixing and can be carried out directly in the mixer. It has lower equipment requirements and is suitable for adding multiple modifiers (such as rubber and plastic fibers), and is less sensitive to the content of lignin [79,80]. However, lignin tends to aggregate in dry-process operations, necessitating prolonged mixing durations or optimization of the fiber length-to-diameter ratio to enhance homogeneity [81,82]. The fatigue life of its mixture might decrease due to an overly high lignin content, and the void in the mineral aggregate (VIM) of the dry-mixed material is relatively high, which might require additional fillers for adjustment [79,83,84].

Figure 11.

Preparation of lignin-modified asphalt mixtures by the dry process.

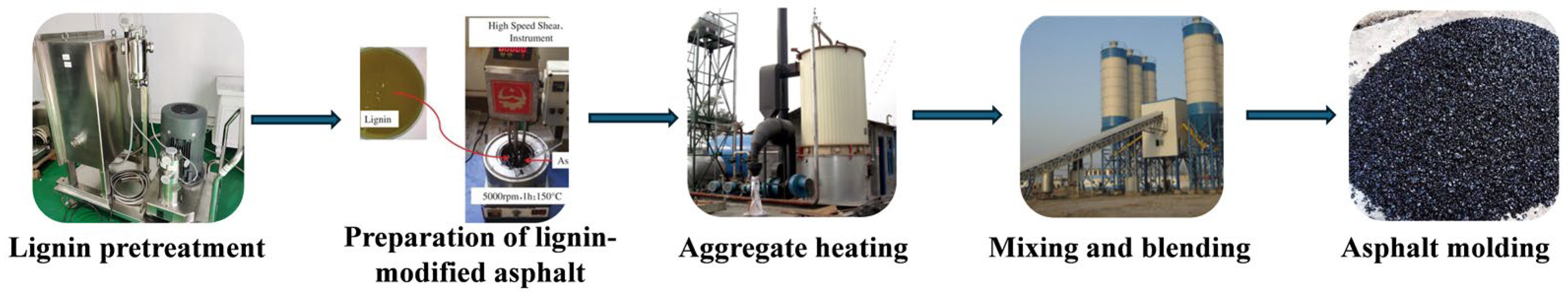

3.2.2. Wet Process

As depicted in Figure 12, in the wet process, lignin is crushed and dried at 105 °C for complete dehydration. Afterward, the preheated asphalt and lignin are blended in a high-shear mixer. The process takes place at a temperature of 160–180 °C, rotating at 4000–5000 rpm for 30–60 min to achieve thorough homogenization and dispersion. The aggregates are then heated to 145–155 °C, maintaining a temperature of 5–10 °C below that used in the dry process. Eventually, after a brief period of mixing, the asphalt mixture is finalized [14,62,82]. The wet process allows for a more even distribution of lignin within asphalt, making it suitable for incorporating higher amounts of lignin and exhibiting improved compatibility with asphalt. Nevertheless, the wet process necessitates the utilization of high-speed shear mixers and strict temperature control, thereby augmenting production costs. The pre-mixed binder requires special storage and transportation, restricting on-site applications [85].

Figure 12.

Preparation of lignin-modified asphalt mixtures by the wet process.

4. Performance of Lignin-Modified Asphalt

4.1. Conventional Performance

The conventional properties of lignin-modified asphalt have been analyzed and evaluated through basic methods, such as the penetration, softening-point, ductility, and viscosity tests. This section reviews the modification conventional performance of lignin on asphalt that have been reported in recent years. The basic properties and rheology of lignin-modified asphalt are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Impact of lignin on physical properties and rheological properties.

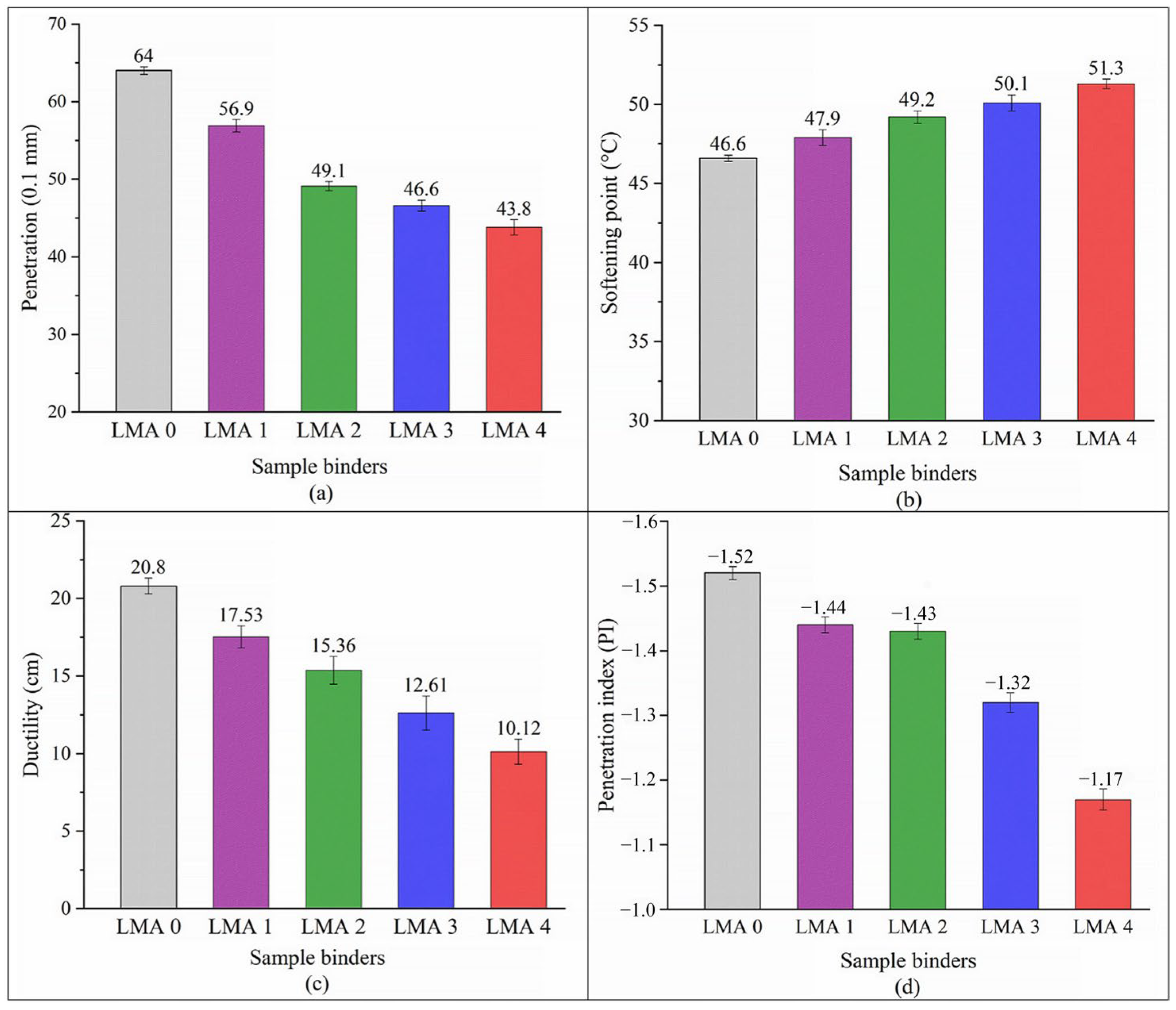

4.1.1. Cone Penetration

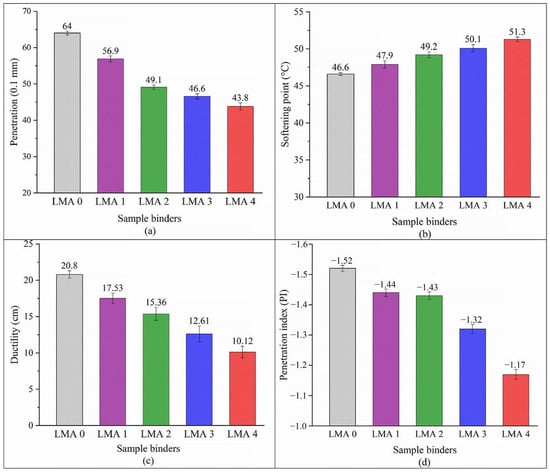

Cone penetration measurement chiefly serves to determine the hardness or softness of asphalt. A greater cone penetration value indicates that the asphalt is comparatively softer and exhibits better flowability, being appropriate for application in low-temperature climate or cold climate conditions. Conversely, a lower cone penetration value indicates harder asphalt, which is suitable for high-temperature or high-load conditions [95,96]. Lignin’s rigid aromatic configuration enhances asphalt’s hardness and viscosity. Typically, blending lignin into asphalt diminishes its penetration. Figure 13a shows that lignin addition causes a significant reduction in asphalt penetration (from 64 for LMA0 to 43.8 for LMA4, representing a 31.6% reduction). This suggests that lignin can boost the hardness and viscosity of asphalt, in addition to improving its rheological characteristics at high temperatures [50]. The penetration index (PI) reflects asphalt’s temperature susceptibility [97]. Figure 13d shows that adding lignin to asphalt raises the PI value. At a 20% lignin content in the mixture, the asphalt’s PI decreases from 1.52 to 1.17, representing a 23.02% reduction, which is 1.28 times higher than the base asphalt’s PI. This means lignin-modified asphalt (LMA) has lower temperature sensitivity, making it less affected by temperature changes than base asphalt [50]. In SBS-modified asphalt with lignin, the penetration drops from the base asphalt’s 69/0.1 mm to 53/0.1 mm [98]. This change ties to lignin’s polyphenolic hydroxyl groups and aromatic parts, which strengthen asphalt’s intermolecular forces, increasing its hardness and high-temperature stability [99]. Song et al., 2023 [65] developed lignin-based epoxy asphalt (ELEA) by mixing lignin-based vitrimer (ELV) with base asphalt. Their findings revealed that the penetration of ELEA was substantially lower than that of base asphalt and continued to decline as the ELV content increased.

Figure 13.

General characteristics of asphalts: (a) penetration; (b) softening point; (c) ductility; (d) PI [50].

4.1.2. Softening Point

The softening point indicates the susceptibility of asphalt to temperature variations [100,101,102]. As depicted in Figure 13b, with the increment of lignin addition, the softening-point outcomes exhibit an ascending tendency. Once the lignin content reaches 20%, the asphalt softening point climbs from 46.6 °C to 51.3 °C, which reveals enhanced high-temperature performance of the modified asphalt [50]. Research shows that adding lignin to base asphalt gives rise to a higher softening point. In cases where the base asphalt’s softening point is 50 °C, the addition of 5%, 10%, and 15% lignin can increase it by 1.4 °C, 3 °C, and 4 °C, respectively. Including 15% lignin can raise the softening point by 8% [13]. As shown in Table 5, the addition of lignin to asphalt formulations designed for cold-region applications and normal traffic conditions (PG 58S-28 and PG 52S-34) yielded the following outcomes: For PG 58S-28 asphalt, increasing lignin content from 0% to 30% made the average softening point rise from 41.3 °C to 46.4 °C. As for PG 52S-34 asphalt, the softening-point temperature increased by 6.4 °C, climbing from an initial 36.3 °C to 42.7 °C. The upper and lower section softening points had an absolute difference of less than 2.0 °C, which reflects the mixture’s great stability and the even dispersion of sulfate lignin in asphalt [86].

Table 5.

Results of the storage stability tests for unmodified and lignin-modified asphalts PG 58S-28 and PG 52S-34.

4.1.3. Ductility

When lignin is added in proper quantity, it can maintain the ductility of asphalt effectively. Here, lignin mainly works as an antioxidant, slowing asphalt oxidation through free-radical scavenging and thereby sustaining the asphalt’s ductility [103]. Still, over-addition of lignin is likely to diminish asphalt’s ductility. Elevated lignin concentrations can induce foaming and material crystallization, consequently limiting the permissible replacement ratio [22,104]. As shown in Figure 13c, when lignin is added to the asphalt, the ductility decreases from 20.8 cm to 10.12 cm, indicating a 51.3% decrease, corresponding to a value 2.05-fold greater than the base asphalt’s measurement. This implies that adding lignin may compromise the flexibility and deformation resistance of asphalt [50]. Even a small quantity of lignin can substantially reduce the ductility of asphalt. When the lignin content is relatively high, the impact on ductility becomes less sensitive. This can be explained by the fact that the added lignin polymerizes into larger masses within the asphalt, thereby disrupting its original properties and causing a loss of ductility [103]. Cai et al., 2023 [31] processed lignin with formic acid to obtain formic acid lignin and then modified the matrix asphalt with formic acid lignin. It was discovered that the formic acid lignin-modified asphalt exhibited superior ductility in low-temperature environments relative to the lignin-modified asphalt, which might be attributed to the enhanced flexibility of the molecular chains. Zhao et al., 2011 [89] incorporated enzymatic hydrolyzed lignin (EHL) into petroleum asphalt and tested the ductility at 15 °C. A comparison showed that unmodified asphalt had higher ductility than EHL-modified asphalt. Elevated EHL concentrations correlated with progressively diminished asphalt ductility. The cause was that after EHL was dispersed in the asphalt, some EHL contracted at low temperatures to form larger particles.

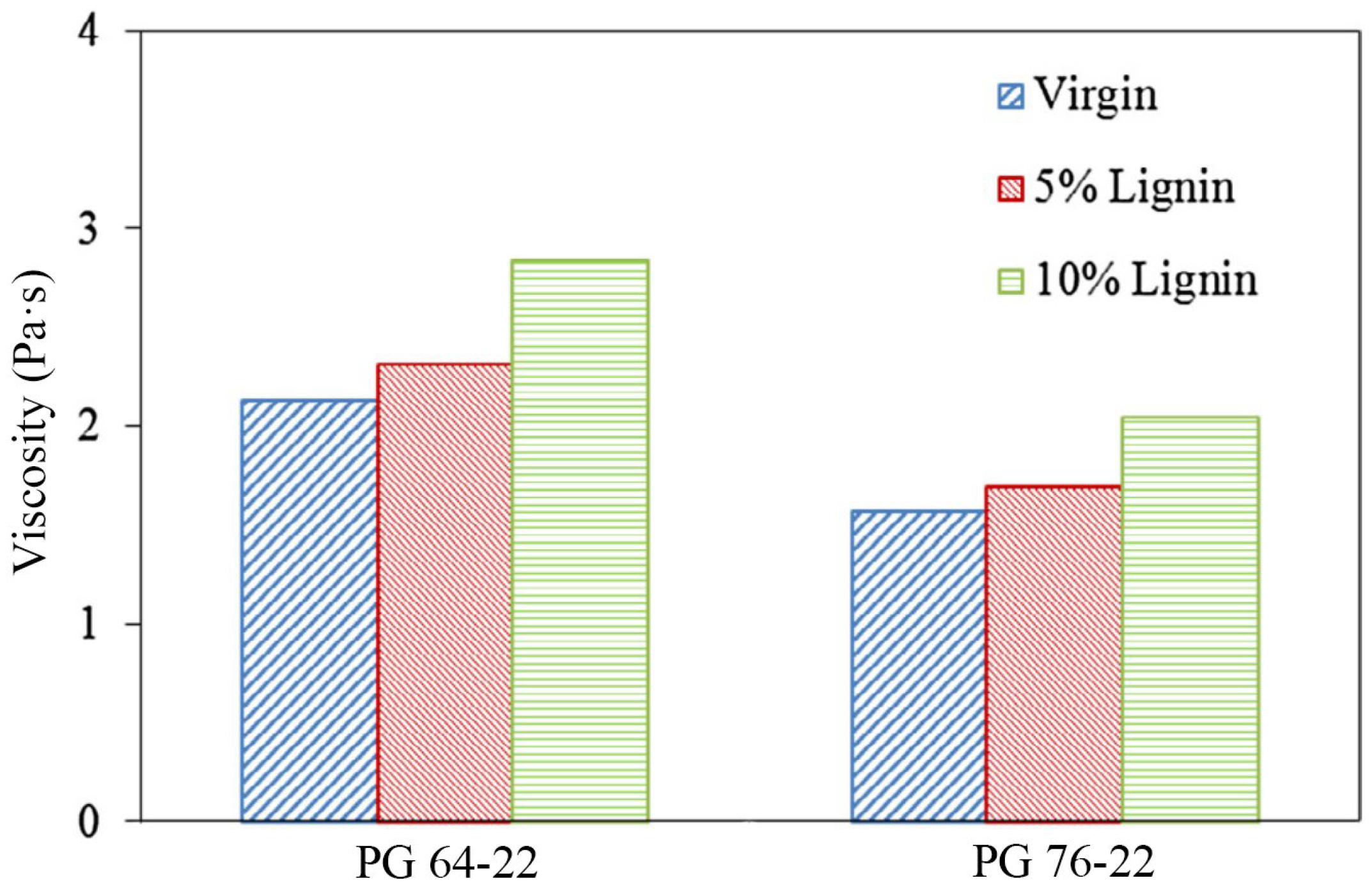

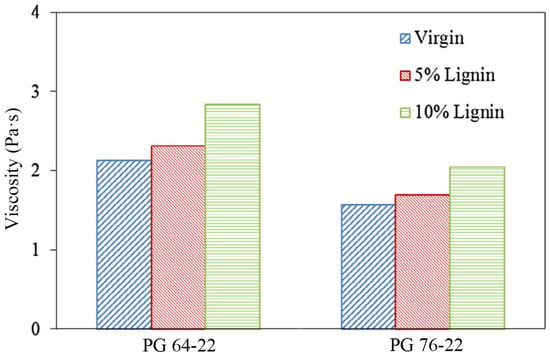

4.1.4. Viscosity

Viscosity serves as a critical performance indicator in asphalt mixture design and pavement construction. Viscosity directly influences the fluidity, workability, and ultimate performance of asphalt mixtures, and determines the optimal mixing temperature and the acceptable range of compaction temperatures [105]. Generally, lignin-modified asphalt has higher viscosity than unmodified asphalt. This is advantageous for improving the storage modulus of asphalt and only slightly affects the loss modulus [22]. Xu et al., 2017 [87] assessed the workability and mixability of asphalt binders using rotational viscosity measured at 135 °C. Figure 14 illustrates the viscosity characteristics of unaged PG 64–22 and PG 76–22 asphalt binders (unaged) containing 0%, 5%, and 10% lignin. The study indicates that adding lignin powder to base asphalt increases its viscosity. Although higher processing temperatures might be indicated, the measured viscosity values satisfy the Superpave specification requirements. Even with 10% lignin added, it retains adequate fluidity for engineering use. Adding lignin to asphalt results in asphalt with increased viscosity. This phenomenon results from the aromatic components in lignin molecules interacting with the analogous structures present in asphalt. The ether groups, phenolic groups, and polar groups in lignin also have strong interactions with the polar structure and heteroatoms in the asphalt. Acting as a connecting agent, lignin can create numerous cross-links within the asphalt structure, enhancing its overall coherence and strength. The specific structure of lignin facilitates the establishment of a three-dimensional network in asphalt, consequently improving its structural integrity [103].

Figure 14.

Effect of lignin on rotational viscosity at 135 °C [87].

4.2. Rheological Performance

4.2.1. High-Temperature Performance

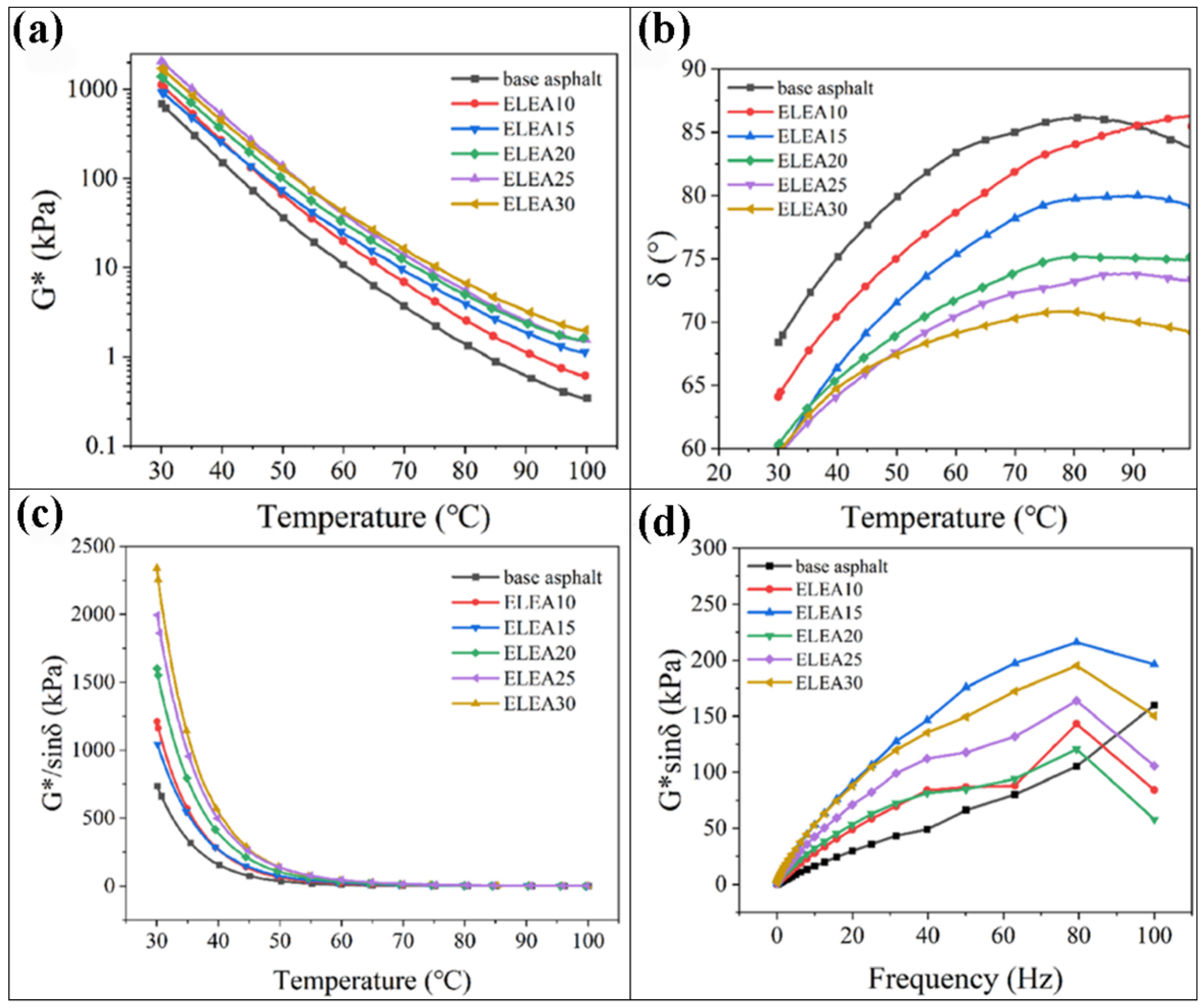

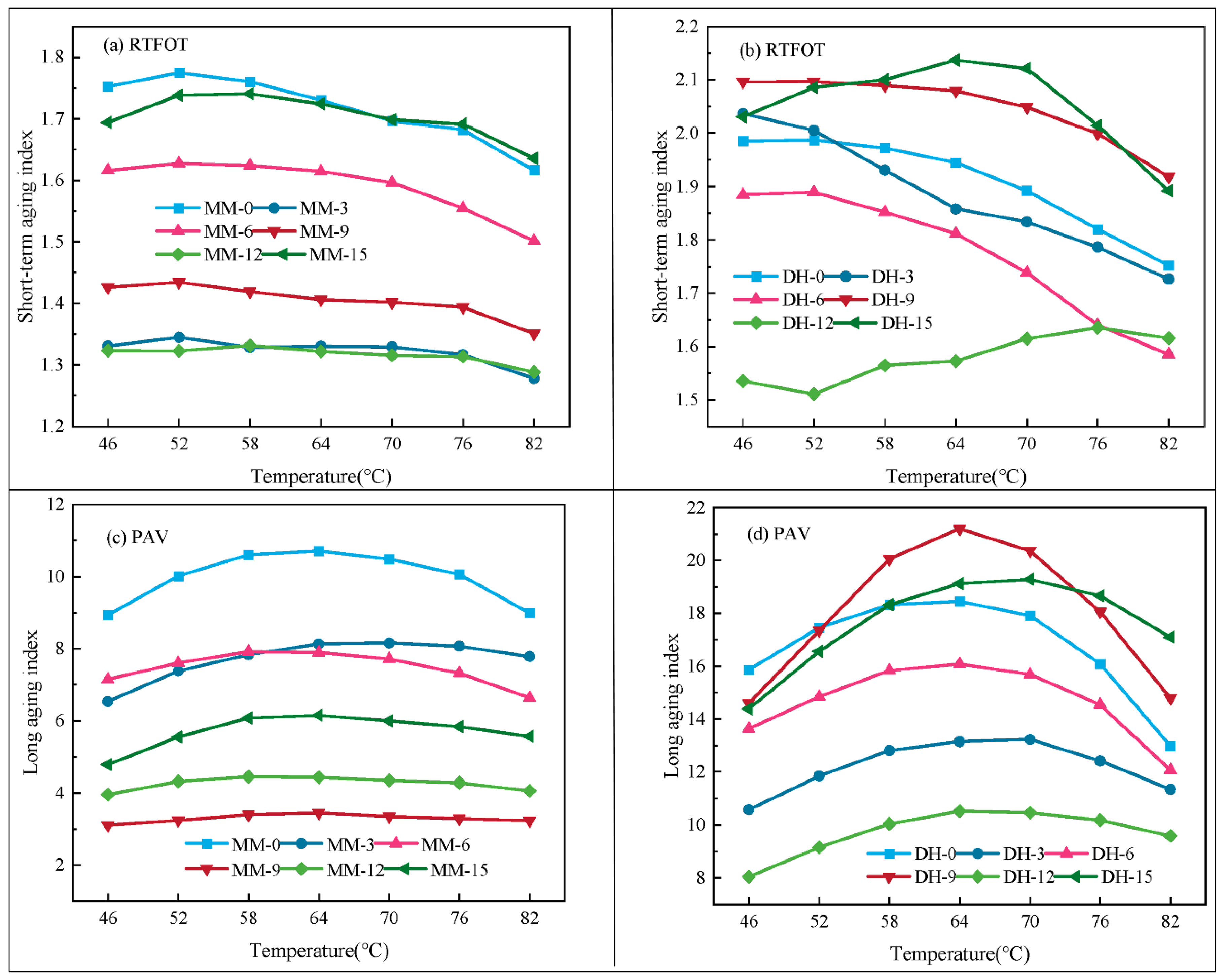

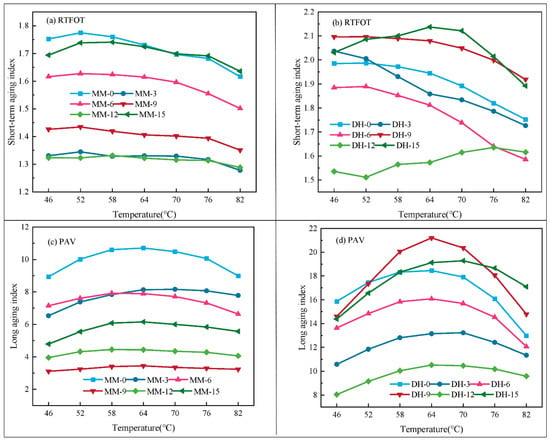

Rheological performance is typically detected by the dynamic shear rheometer (DSR). The high-temperature performance of asphalt is characterized using the complex modulus (G*), phase angle (δ), and rutting factor (G*/sinδ) [106,107]. Research indicates that incorporating lignin enhances the thermal resistance of asphalt at elevated temperatures, decreases its temperature sensitivity, heightens hardness, lessens ductility, reduces cracking in cold conditions, while also boosting the base asphalt’s viscosity [22,108]. Cheng et al., 2020 [22] performed DSR experiments on various modified asphalt samples at 58 °C, 64 °C, and 70 °C. The study revealed that elevating lignin concentration led to a rise in the modified asphalt’s complex modulus (G*), accompanied by a reduction in phase angle (δ). This indicates the material became more elasticity-dominated and its high-temperature stability was improved. Cai et al., 2022 [108] examined the rutting factor (G*/sinδ) of 70# and 90# asphalts with varying lignin contents. Higher G*/sinδ values indicate better high-temperature performance and resistance to permanent deformation in asphalt binders. As lignin content rises, the G*/sinδ of aged and unaged asphalt increases. The 15% lignin-containing modified MM asphalt sample had the best rutting resistance after aging, yet its PG high-temperature grade did not change. However, DH asphalt containing 15% lignin demonstrated optimal rutting resistance at high temperatures, regardless of aging. Its PG grade improved by one level, highlighting strong practical applicability.

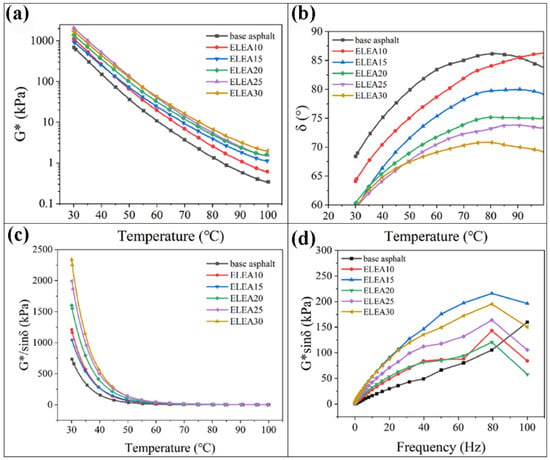

Song et al. (2023) [65] added lignin-based vitrimer (ELV) to asphalt to prepare epoxy asphalt based on lignin (ELEA). With the increasing proportion of ELV, the G* of ELEA increased significantly (Figure 15a), indicating improved stiffness, adhesion, and anti-deformation ability. As demonstrated in Figure 15b, the δ values of ELEA were consistently reduced relative to base asphalt and showed a decreasing trend with increasing ELV proportion. This indicates that ELV imparted greater elasticity to the asphalt. Figure 15c shows that ELV significantly increased the G*/sinδ values of ELEA compared to the base asphalt, and the values rose with higher ELV content, indicating enhanced rutting resistance. The lower the fatigue loss modulus (G*sinδ), the better the fatigue resistance. Multiple studies have indicated that a moderate amount of lignin (≤10–15%) typically enhances G*sinδ at low frequencies, suggesting a potential reduction in fatigue resistance under severe loading. However, this effect weakens or even becomes beneficial at high frequencies or with low strain amplitudes. For instance, as shown in Figure 15d, ELEA with 20% lignin-based vitrimer exhibited G*sinδ values comparable to or lower than those of the base asphalt in the high-frequency range, indicating an improvement in resistance to short-term repetitive loading. These results suggest that the fatigue performance of lignin-modified binders is highly dependent on the amount of lignin and the loading conditions.

Figure 15.

Dynamic shear rheometer tests, including temperature and frequency scans, were conducted for both base asphalt and ELEA. The results are presented as follows: (a) complex shear modulus G*; (b) phase angle δ; (c) rutting resistance factor G*/sinδ; (d) fatigue factor G*sinδ [87].

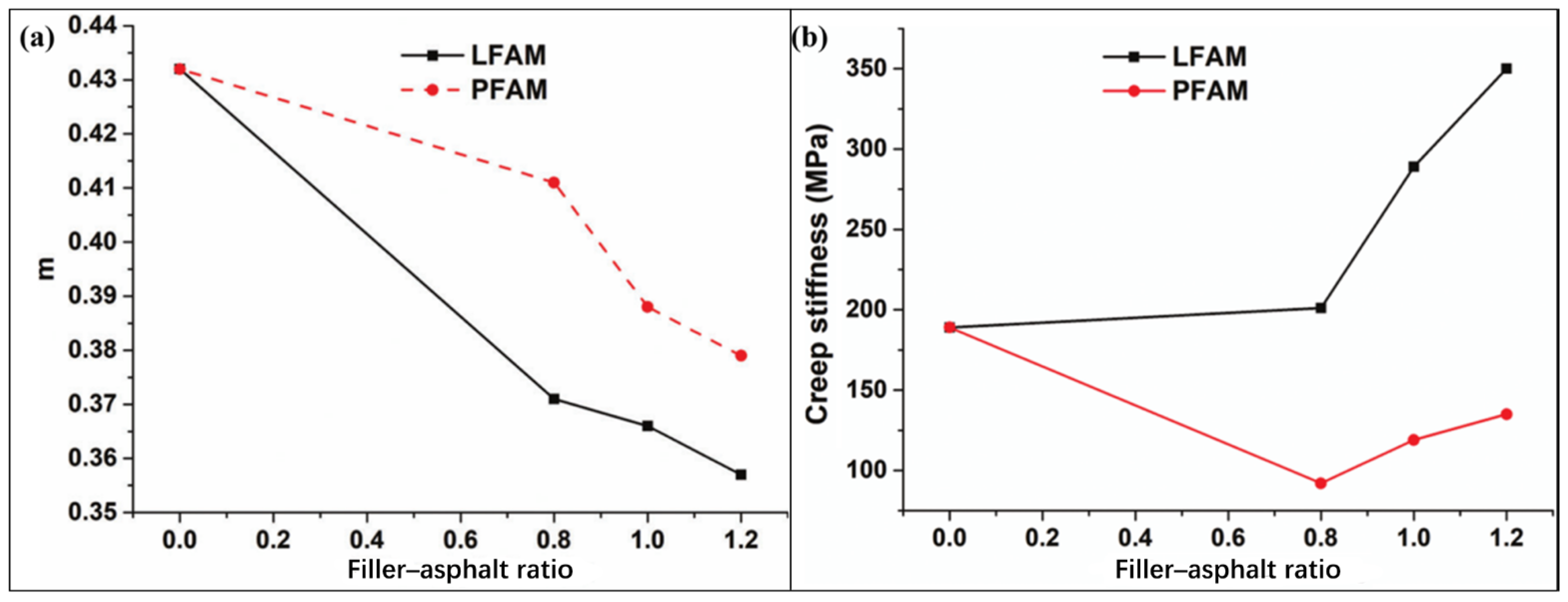

4.2.2. Low-Temperature Performance

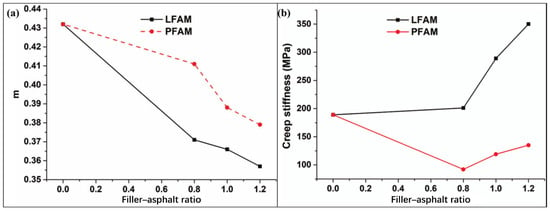

Low-temperature performance is a crucial indicator for assessing the duration of service and reliability of asphalt in low-temperature environments. The capacity of asphalt to resist low-temperature cracking can be characterized by creep stiffness (S) and creep rate (m) [109,110,111]. At low temperatures, lignin fibers predominantly act as fillers, and their crack resistance is less favorable than that of polyester fibers. Polyester fiber-modified asphalt exhibits a lower S value and a higher m value, and the m/S ratio is more favorable. As shown in Figure 16, at a filler-to-asphalt ratio of 0.8, lignin fiber-reinforced PSAM (LFAM) and polyester fiber-reinforced PSAM (PFAM) exhibit the lowest creep stiffness values, suggesting the optimal low-temperature crack resistance. When compared to the creep stiffness of SMPU/SBS composite-modified asphalt (PSA), LFAM’s creep stiffness remains above that of PSA. With the increase in the ratio of filler to asphalt, the creep stiffness of PFAM decreases. Under the same ratio of filler to asphalt, its creep stiffness is lower than that of LFAM and even lower than that of PSA [112]. Research findings reveal that the glass transition temperature (Tg) of lignin-based epoxy asphalt (ELEA) is relatively low, indicating that ELEA has an excellent deformation capability at low temperatures [65]. Comprehensive performance enhancement of asphalt is difficult to achieve with a single additive. Diatomite demonstrates outstanding performance in enhancing high-temperature rutting resistance, yet its contribution to low-temperature properties is somewhat limited. In contrast, lignin fiber significantly improves low-temperature crack resistance, but its influence on high-temperature performance is relatively modest [113]. Hence, the utilization of composite additives can be contemplated to simultaneously improve asphalt’s high- and low-temperature performance. A typical approach is to combine lignin fibers with rigid mineral fillers such as diatomite [114]. Diatomite predominantly improves high-temperature rutting resistance by increasing the elastic modulus and reducing viscous flow, whereas lignin fibers contribute to crack-bridging and energy dissipation at low temperatures. Similarly, combining lignin with waste engine oil can partially offset lignin-induced hardening, restoring ductility while maintaining improved high-temperature stiffness [115]. These results suggest that lignin is particularly suitable for composite modification systems, where its stiffening and antioxidant functions are complemented by softeners or flexible fibers.

Figure 16.

The test results for LFAM and PFAM with different filler-asphalt ratios: (a) creep stiffness results; (b) m-value test results [112].

4.3. Aging Resistance

Asphalt encompasses such aging processes as thermal aging, photodegradation, and oxidative aging, etc. [116]. Cai et al., 2022 [108] carried out RTFO and PAV aging experiments on different asphalts with varying contents of lignin at different temperatures, computed the aging index of the G*AI complex shear modulus for asphalt, as depicted in Figure 17, and indicated that the Maoming asphalt sample with 9% lignin had the best aging resistance effect, and the Donghai asphalt sample with 12% lignin also showed good aging resistance performance. The introduction of enzymatic lignin epoxy resin significantly strengthened the high-temperature stability and anti-aging attributes of modified asphalt. Through tests like penetration, softening point, and the thin-film oven test (TFOT), Xie et al., 2011 [117] found that adding 2–9 wt% of enzymatic lignin epoxy resin could significantly enhance the softening point and anti-aging performance of asphalt. He et al., 2022 [66] synthesized lignin-grafted layered double hydroxides (LG-g-LDHs), which can significantly enhance asphalt’s ultraviolet aging resistance. Compared to LDHs-modified asphalt (LMB) and base asphalt (PB), LG-g-LDHs-modified asphalt (LG-g-LMB) shows slighter performance degradation after ultraviolet aging and has better colloidal stability. Brasil et al., 2024 [64] found that adding lignin-based nanocarbon (LNC) to asphalt binders improves the anti-aging performance of both pure asphalt and SBS-modified asphalt, resulting in a lower aging index.

Figure 17.

The G*AI results under various aging conditions: (a,b) show the aging index of different asphalts after short-term aging, while (c,d) illustrate the aging index of different asphalts after long-term aging [108].

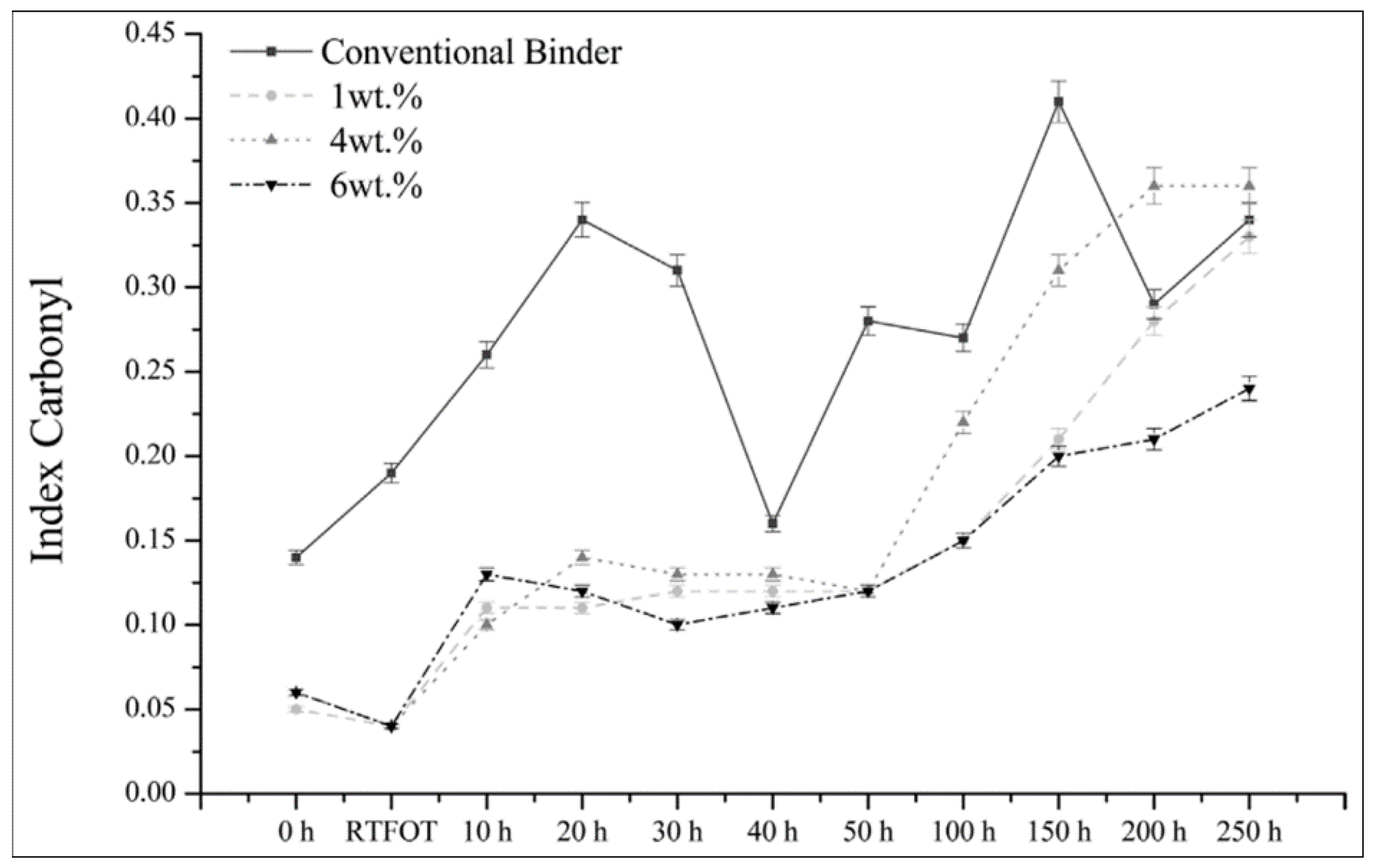

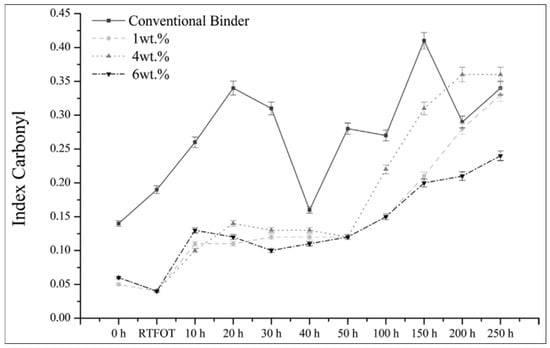

Depicted in Figure 18 are the carbonyl index values at each stage. All lignin-modified specimens exhibited progressively increasing carbonyl content throughout the aging process [4,68]. Photodegradation can trigger chain scission and oxidation, thus raising the concentration of C=O groups. With the progression of photo-oxidative degradation, carbonyl group formation intensifies; it signifies that the oxidation extent in modified asphalt samples heightens, stiffness climbs, and it becomes more vulnerable to cracking [118,119]. Oxidative aging is typically evaluated by conducting accelerated aging tests in high-temperature and high-oxygen environments. Rukmananda et al., 2018 [120] investigated and discovered that the 3% and 6% lignin mixtures exhibited higher penetration in the penetration test and achieved 62 °C in the softening point test, suggesting that they possess superior stability and antioxidant performance at high temperatures.

Figure 18.

Carbonyl index of conventional and lignin-modified asphalt binders following RTFOT and after undergoing the weathering test for up to 250 h [66].

4.4. Summary and Discussion

Taken together, the binder-level studies reviewed in Section 4 consistently indicate that lignin tends to increase high-temperature stiffness and rutting resistance and to improve short-term aging resistance, whereas its influence on low-temperature cracking and fatigue-related indices is more sensitive to lignin type, dosage, and the presence of co-modifiers. The general trend toward higher complex modulus and softening point but lower penetration can be rationalized by lignin’s stiff, aromatic structure and its interaction with asphaltene aggregates. Additionally, the same stiffening effect can reduce chain mobility at low temperatures, which explains why some studies report reduced ductility or increased low-temperature stiffness when lignin is used at high dosages or without softer components.

However, the comparability of the reported numerical values is limited by substantial differences in lignin origin and pretreatment, base asphalt grade, aging protocols, and rheological test conditions. Contradictory trends in fatigue parameters (e.g., G*/sinδ, LAS-based damage indices) can often be traced back to differences in loading mode, failure criteria, or aging level. Therefore, the conclusions drawn here should primarily be understood as qualitative trends rather than universal quantitative thresholds. To move beyond case-specific observations, future research should adopt more harmonized experimental protocols and systematically investigate the combined effects of lignin type, dosage, and co-modifiers on binder rheology and durability.

5. Performance of Lignin-Modified Asphalt Mixtures

The performance evaluation results of lignin-modified asphalt mixtures are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Influence of different lignin fibers on the performance of asphalt mixtures.

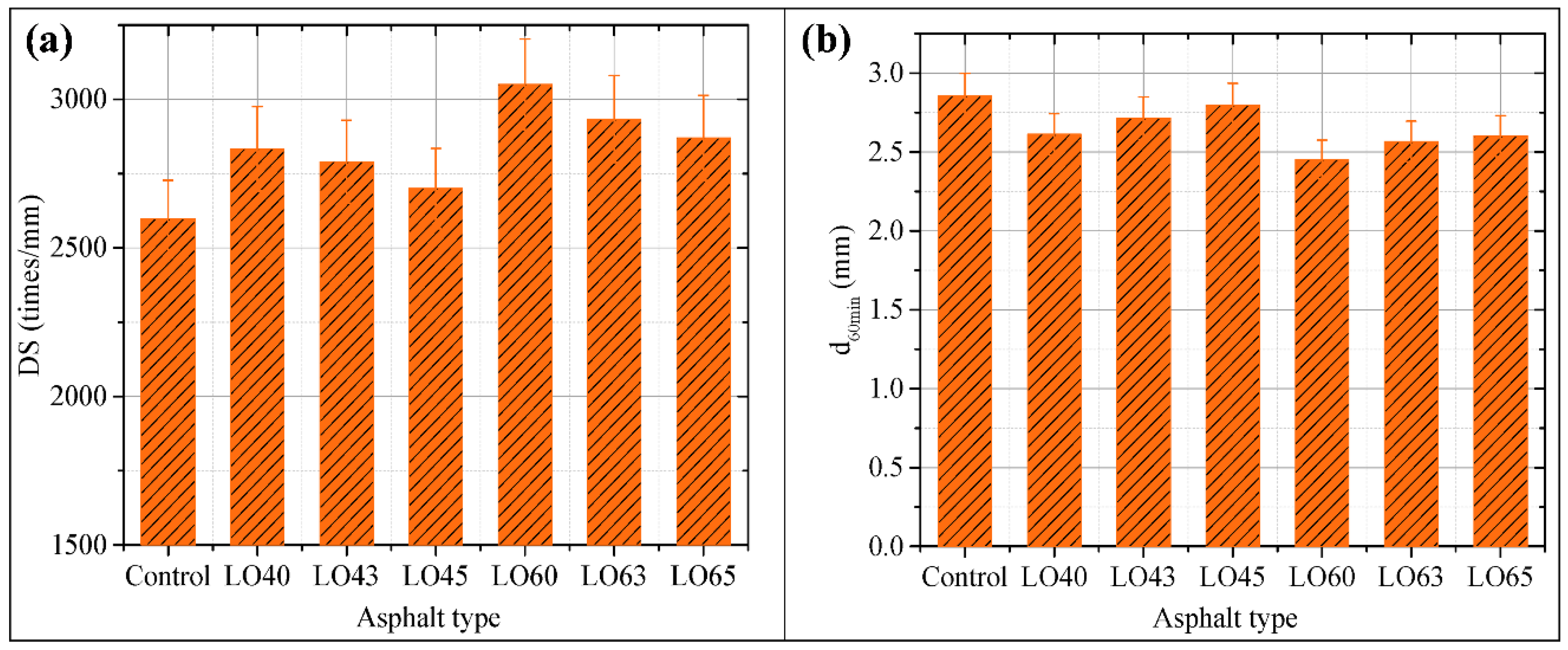

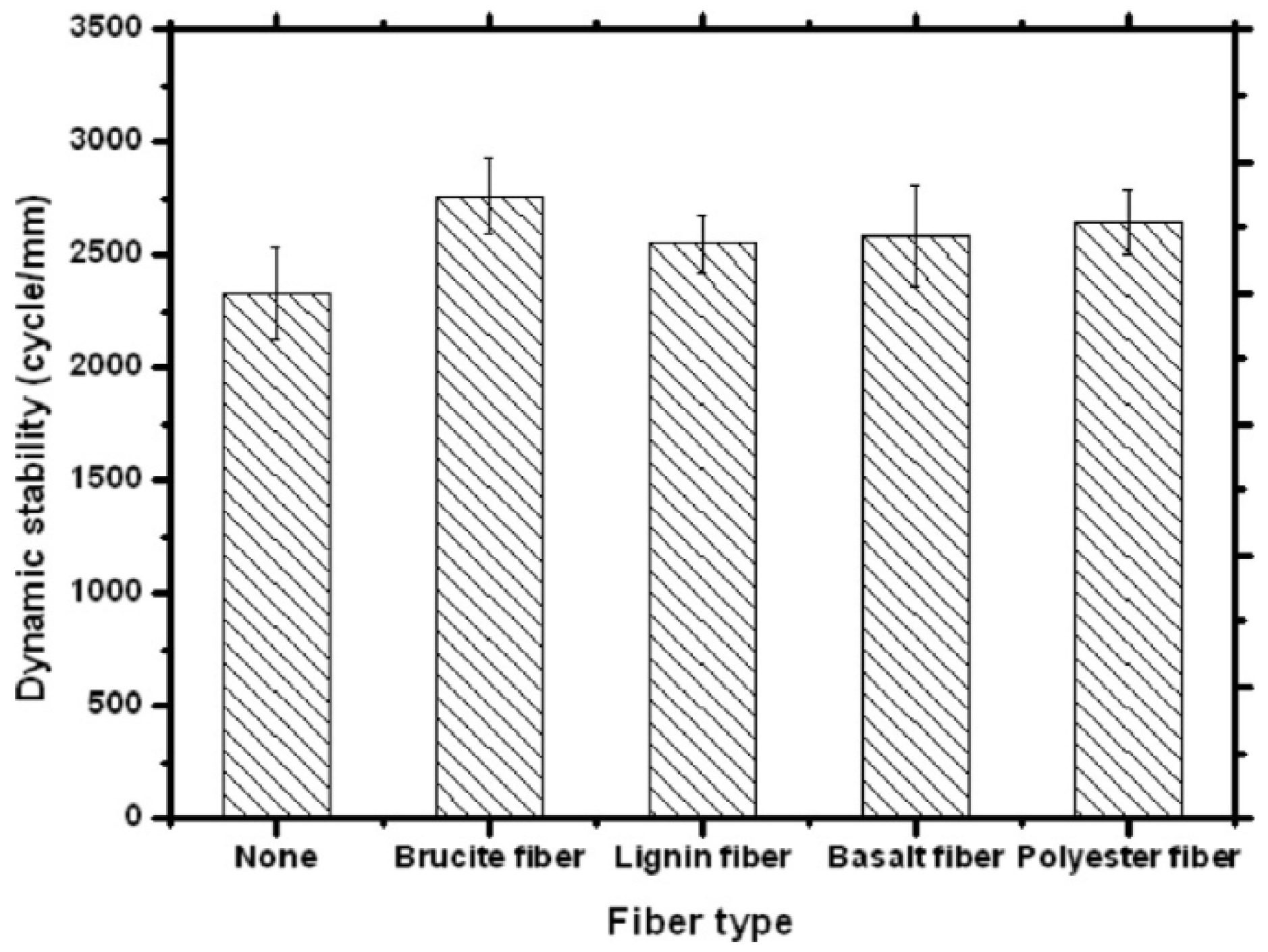

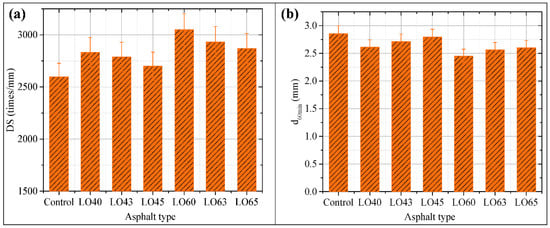

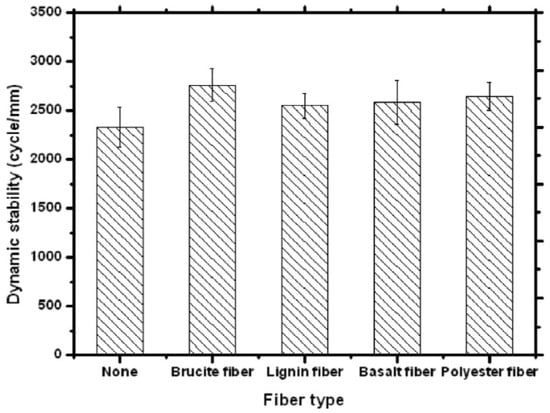

5.1. High-Temperature Performance of Asphalt Mixtures

For asphalt mixtures, high-temperature performance is often assessed using the rutting test. Dynamic stability (DS), which indicates the number of wheel passes required to produce a 1 mm rut depth in the slab specimen, serves as the evaluation indicator. A greater DS value represents superior rutting performance [96]. As depicted in Figure 19, the dynamic stabilities of the lignin-modified asphalt mixtures LO40 (with a lignin addition of 4% and a waste engine oil addition of 0%) and LO60 (with a lignin addition of 6% and a waste engine oil addition of 0%) are 2833.56 times/mm and 3050.69 times/mm respectively, representing an increase of 9.05% and 17.41% compared to the base asphalt mixture (2598.32 times/mm). Once waste engine oil was added, a decrease in dynamic stability was observed; however, the dynamic stability of LO45 (with a lignin addition of 4% and a waste engine oil addition of 5%) (2699.98 times/mm) shows superior performance to the standard asphalt mixture, suggesting that lignin can partially counteract the negative influence of waste engine oil on the performance of asphalt mixtures [93]. Zhang et al., 2020 [73] conducted a study comparing the rutting performance of lignin powder-modified and lignin fiber-modified asphalt mixtures. The study revealed that both have a marked effect on reducing the rut depth in asphalt mixtures. The dynamic stability of SMA-LF (lignin powder-modified asphalt mixture) ranked the highest, followed by SMA-LP (lignin fiber-modified asphalt mixture), demonstrating the best anti-rutting performance. Fibers are homogeneously distributed within the asphalt mixture, giving rise to a three-dimensional cross-linked network. This network effectively constrains the flow of the asphalt phase, thereby substantially enhancing the material’s shear-deformation resistance under high-temperature conditions [130,131]. In comparison with the basalt-fiber–asphalt mixture, the dynamic stability of the lignin-fiber–asphalt mixture is lower. The DS for the lignin-fiber–asphalt mixture is 3600 times/mm, whereas the basalt-fiber–asphalt mixture has a DS of 4200 times/mm. Nevertheless, the cost of lignin fiber is merely one-third of that of basalt fiber [132]. Xiong et al., 2015 [133] performed a comparative analysis on the dynamic stability of asphalt modified with brucite fiber, lignin fiber, basalt fiber, and polyester fiber. From Figure 20, the dynamic stability of asphalt mixtures improved when any of these fibers were added, compared to the mixture without fiber addition. The dynamic stability of the brucite fiber-reinforced asphalt mixture was higher than that of the lignin fiber-modified mixture yet lower than that of the basalt and polyester fiber-modified mixtures.

Figure 19.

The dynamic stability and rutting depth at 60 min: (a) dynamic stability (DS); (b) d60min [93].

Figure 20.

Results of the wheel rutting tests [93].

5.2. Low-Temperature Performance of Asphalt Mixtures

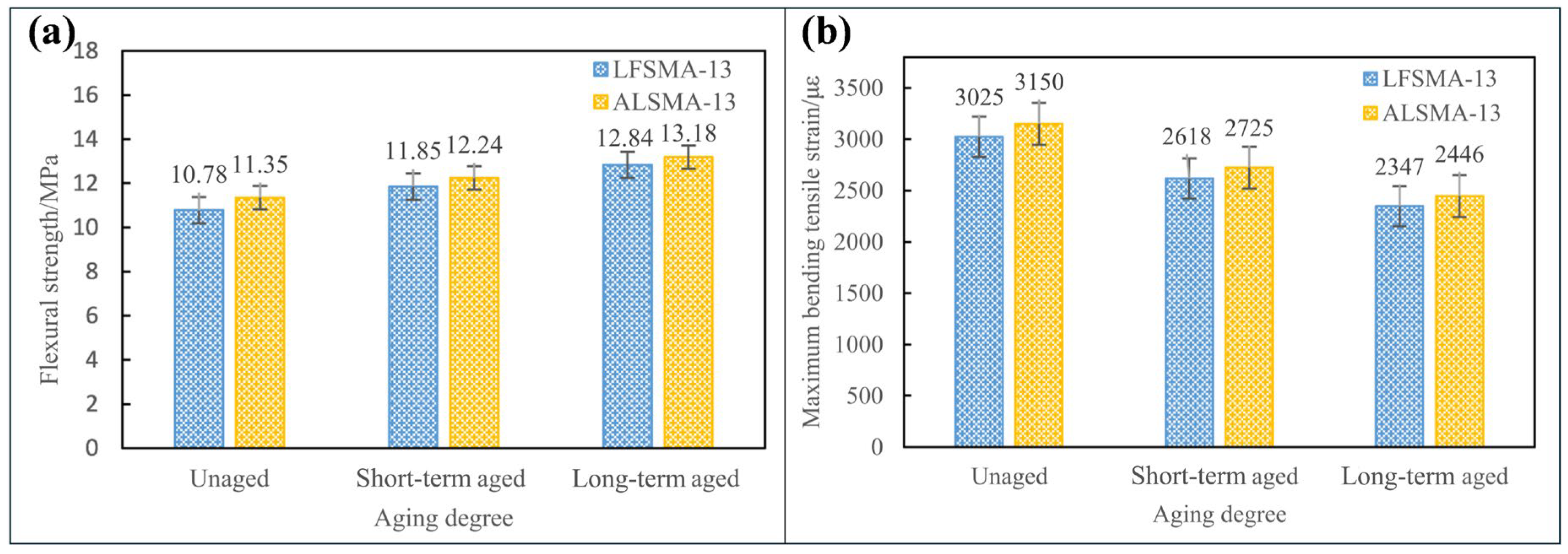

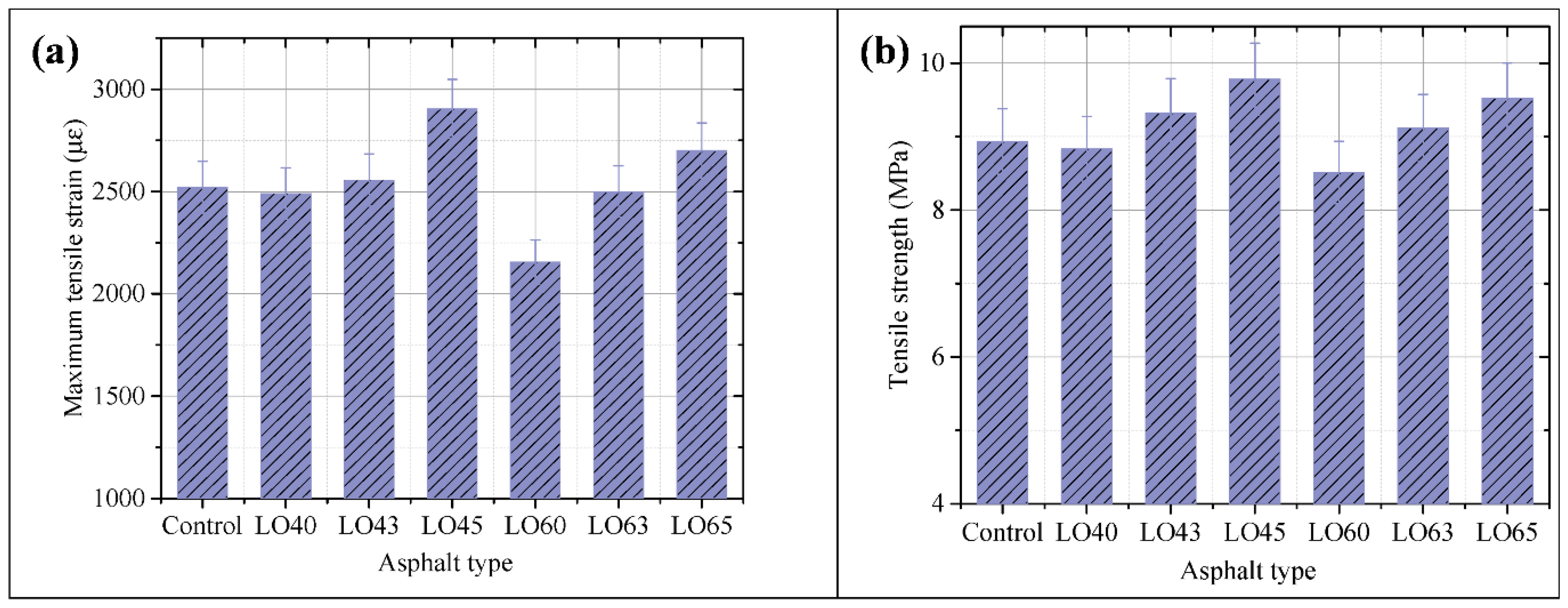

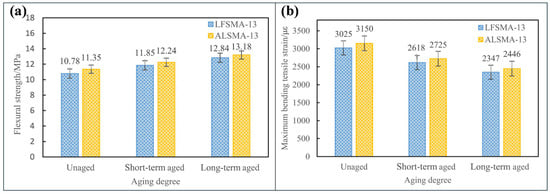

Currently, low-temperature bending tests, creep tests, and indirect tensile tests, among others, are typically employed to represent the crack resistance performance of asphalt mixtures [134]. The addition of an anti-rutting agent to the lignin-reinforced petroleum asphalt mixture (LFSMA-13) yields the anti-rutting, agent-modified lignin fiber-reinforced asphalt mixture (ALSMA-13), as depicted in Figure 21. After aging, the flexural strength of both LFSMA-13 and ALSMA-13 is enhanced, yet the ductility is significantly reduced. ALSMA-13 exhibits superior performance, but its advantage gradually diminishes with aging. The disparity in low-temperature performance between the two is not conspicuous [135]. Such phenomena can be largely attributed to the aging process, which leads to the hardening of the asphalt binder’s structure, an enhancement in its low-temperature stress-bearing capacity, and a decrease in its low-temperature strain-bearing capacity. As depicted in Figure 22, Xue et al., 2022 [93] discovered that the incorporation of lignin diminished the low-temperature crack resistance of asphalt mixtures. Lignin, being a rigid biopolymer, possesses a three-dimensional network structure and aromatic ring groups. These features can augment the elastic components of asphalt and its high-temperature deformation resistance. Nevertheless, the sole addition of lignin elevates the low-temperature stiffness and deteriorates the low-temperature performance. Waste engine oil, which contains light components, can decrease the viscosity of asphalt, augment the viscous components (increase the phase angle), and concurrently enhance the low-temperature ductility (reduce stiffness and increase the m value). Subsequent to the addition of waste engine oil, the maximum tensile strains of LO45 (4% lignin and 5% waste engine oil) and LO65 (6% lignin and 5% waste engine oil) were 2903.5 and 2700.62 με, respectively. These values were 16.39% and 25.28% higher than those of LO40 (4% lignin and 0% waste engine oil) and LO60 (6% lignin and 0% waste engine oil), suggesting that waste engine oil can improve the maximum tensile strain and tensile strength of asphalt mixtures. The rigidity of lignin and the flexibility of waste engine oil are complementary. By adjusting their proportions, the high- and low-temperature performance of asphalt can be balanced. For example, when 6% lignin (LO60) was solely employed for modification, the low-temperature stiffness exceeded the standard. However, after adding 5% waste engine oil (LO65), the outcome was optimal. The low-temperature performance met the standard, and the high-temperature dynamic stability remained higher than that of the control group, rendering it suitable for areas prone to cracking in cold seasons [93]. Wu et al., 2018 [136] found that asphalt mixtures modified with basalt fiber show outstanding low-temperature crack resistance. Polyester fibers also enhance the low-temperature performance of asphalt mixtures. Nevertheless, the low-temperature crack resistance of asphalt mixtures containing lignin fibers is very unstable. Hence, considering the low-temperature performance, it is not advisable to incorporate lignin fibers into asphalt mixtures.

Figure 21.

Results of road performance tests: (a) flexural strength; (b) maximum bending tensile strain [135].

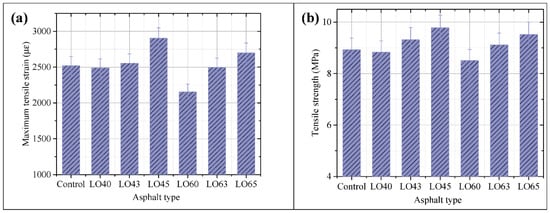

Figure 22.

The maximum tensile strain and tensile strength are presented as follows: (a) maximum tensile strain; (b) tensile strength [93].

5.3. Fatigue Performance of Asphalt Mixtures

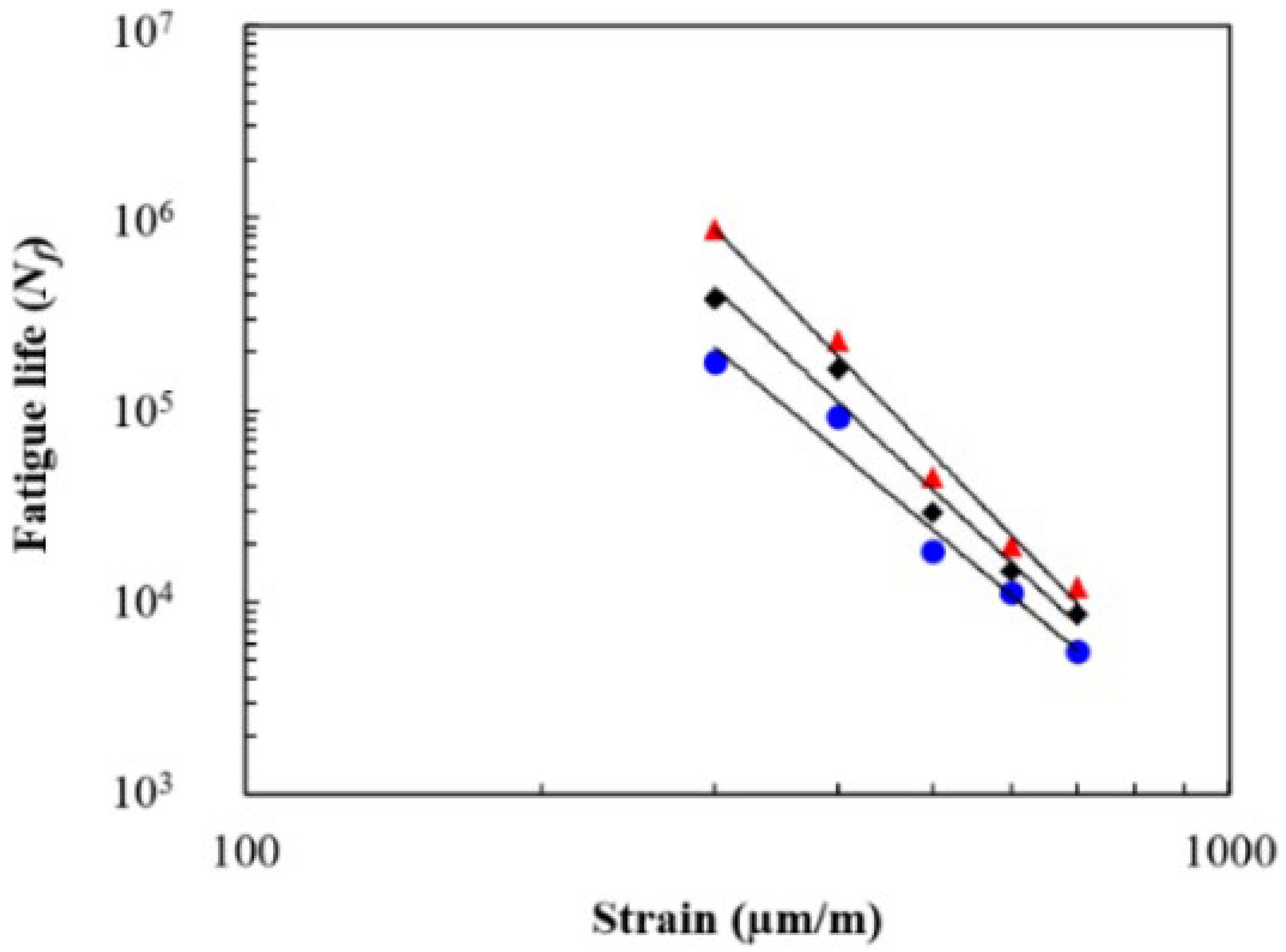

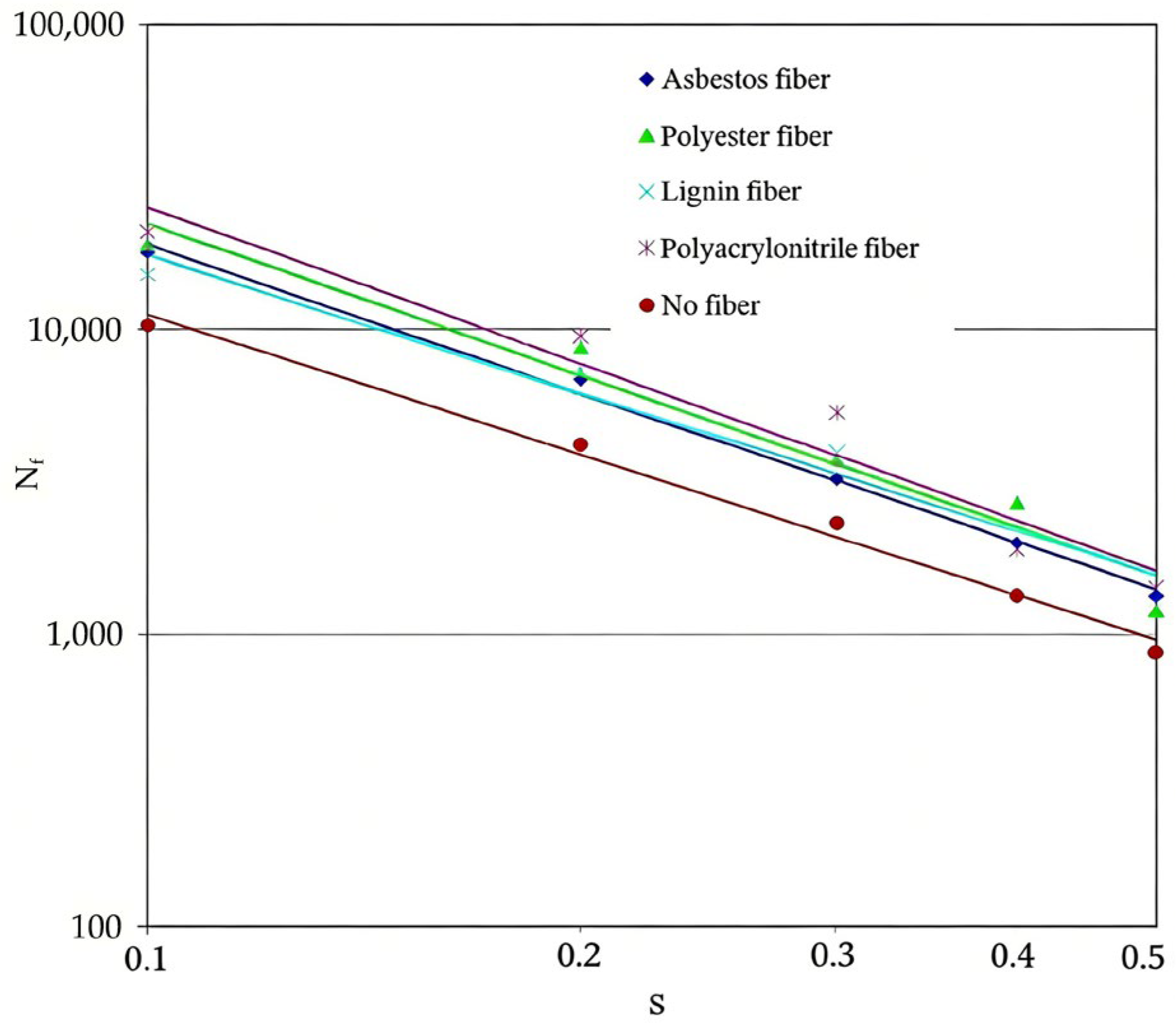

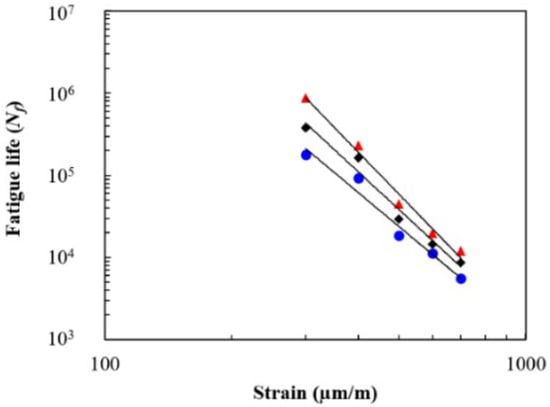

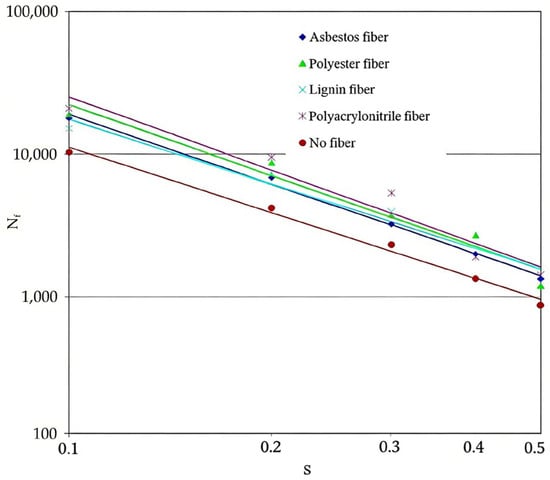

To investigate the fatigue resistance of asphalt mixtures, the four-point or three-point bending beam test and the indirect tensile fatigue test are frequently employed. These approaches evaluate the endurance of asphalt mixtures by simulating the cumulative deformation and fracture behavior under actual loading circumstances [137,138,139]. Figure 23 presents the fatigue-life values of three distinct asphalt mixtures under five strain levels. At the same strain intensity, the fatigue life of the lignin fiber-reinforced asphalt mixture (SMA-LP) is markedly longer than that of the control asphalt mixture (SMA-C). Nevertheless, the fatigue life of the lignin powder-modified asphalt mixture (SMA-LF) is found to be shorter than that of SMA-C. Commonly, fiber-reinforced asphalt mixtures possess higher crack resistance due to the bridging action of fibers between cracks, capable of retarding crack propagation. Nevertheless, the incorporation of lignin fibers did not exhibit such an effect, which might be associated with the inferior compatibility of lignin fibers with asphalt, influencing the adhesion among aggregates. The lignin powder-modified asphalt binder shows better fatigue resistance, probably because of the increased adhesion between aggregates and asphalt, which slows the progression of fatigue cracks [73,140]. Fibers can prominently increase the fatigue durability of asphalt concrete (AC). As depicted in Figure 24, when the stress ratio is 0.5, polyester fibers, polyacrylonitrile fibers, asbestos fibers, and lignin fibers raise the fatigue life by 57.66%, 66.78%, 40.88%, and 22.52%, respectively. Evidently, polyacrylonitrile fibers exhibit the most superior improvement effect, while lignin fibers perform the poorest [141]. Afif et al., 2021 [142] integrated low-density polyethylene (LDPE) plastic waste along with lignin, acting as a coupling agent, into the asphalt concrete binder course (AC-BC), creating a blend of polymer-modified asphalt (PMB) and lignin. The study revealed that the inclusion of lignin improved the compatibility between asphalt and plastic, increased the softening point of PMB, made AC-BC more pliable, and enhanced the pavement’s resistance to the washboard issue.

Figure 23.

Fatigue life of asphalt mixtures as a function of applied strain [73].

Figure 24.

Fatigue life vs. stress ratio of AC mixture (logarithmic scaled) [141].

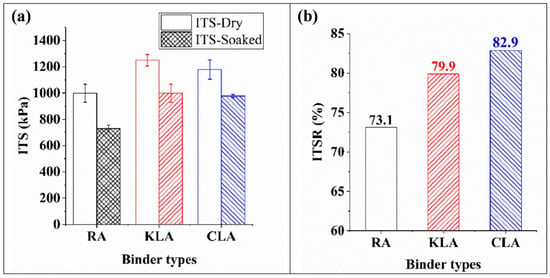

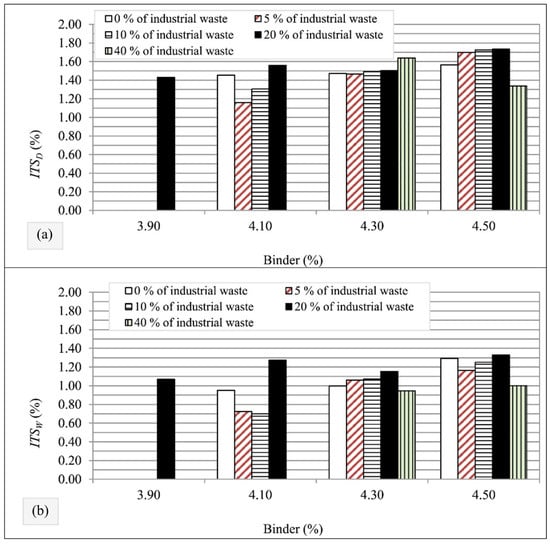

5.4. Moisture Susceptibility

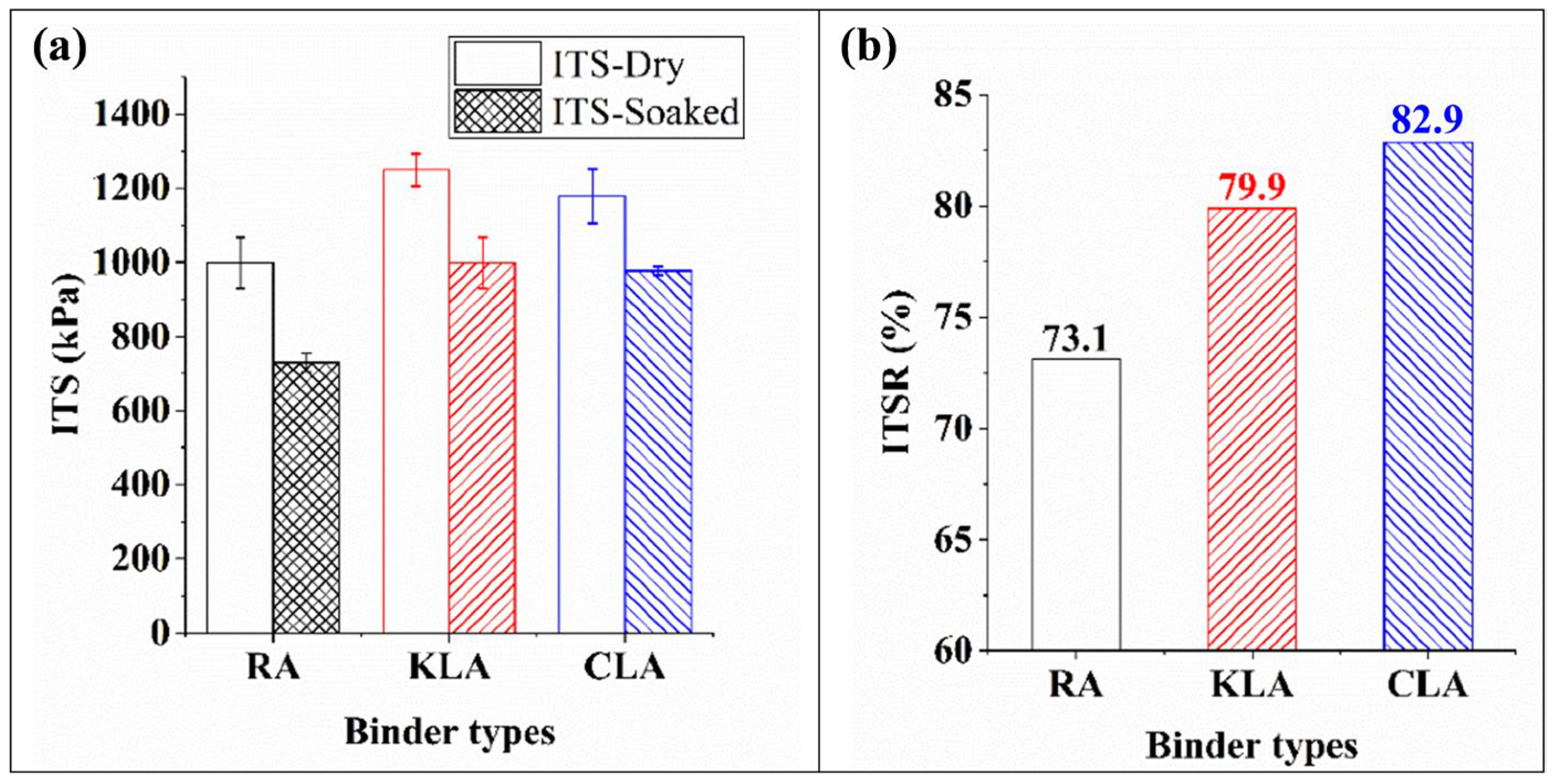

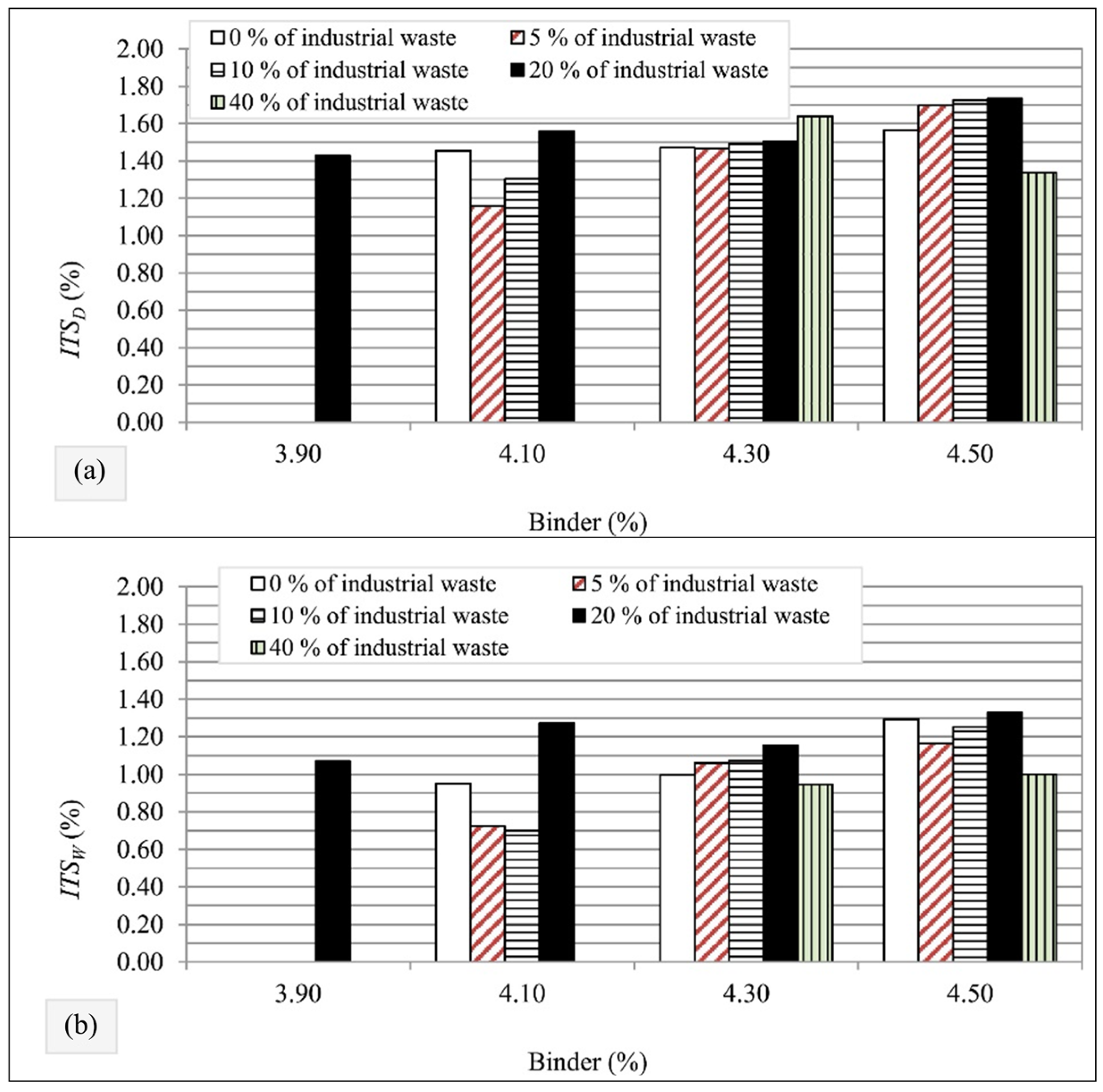

Moisture can cause adhesion failure (peeling) at the asphalt–aggregate interface and cohesion failure in the asphalt binder. Khadim and Ahmad, 2024 [115] carried out moisture susceptibility tests on pure asphalt (VB), asphalt mixtures modified with 5% lignin, and those with 10% lignin. The moisture susceptibilities for the 0%, 5%, and 10% lignin-modified asphalt mixtures were 82.3%, 90.8%, and 86.5%, respectively. All the results surpassed the performance threshold of 70%, and the addition of lignin mitigated the coating loss, indicating an enhancement in moisture susceptibility. Xu et al., 2021 [14] employed the indirect tensile strength ratio (ITSR) method to assess the water-damage resistance of asphalt mixtures in hot conditions and cold-water circumstances. As depicted in Figure 25, the ITSR value of the lignin-modified asphalt mixture (LMA) was 9–13% higher than that of the Pen60/70 mixture, suggesting that it exhibited superior water-damage resistance under cold conditions. The CLA mixture demonstrated the optimum water-damage resistance. The incorporation of lignin extracted from poplar sawdust (KL) and corn stalk residue (CL) significantly enhanced the water-damage resistance of asphalt mixtures in freeze–thaw conditions, and the impacts of the two lignin modifiers on the freeze–thaw damage resistance performance of asphalt mixtures were essentially similar. Rez et al., 2019 [143] undertook research on the moisture susceptibility of asphalt mixtures with varying proportions of industrial waste containing lignin-based biopolymers. As shown in Figure 26, the study found that at an optimal asphalt content of 4.1%, the mixture with 20% industrial waste had a higher dry-state indirect tensile strength than the control mixture at its optimal asphalt content of 4.5%. The wet-state indirect tensile strength was slightly lower but still very close, indicating that incorporating 20% industrial waste at the optimal asphalt content does not reduce the indirect tensile strength. Moreover, the mixture with 20% industrial waste demonstrated better resistance to moisture damage than the control mixture. The mixture containing 20% industrial waste demonstrated superior moisture resistance compared to the control, attributable to (1) lignin’s adhesion-enhancing effect at the asphalt–aggregate interface and (2) foaming phenomena during waste–asphalt blending that promoted superior aggregate coating, thereby improving moisture stability.

Figure 25.

Analysis of ITS test results: (a) ITS values before and after a freeze–thaw cycle and (b) ITSR values [14].

Figure 26.

Indirect tensile strength as a function of binder content for mixtures containing 0%, 5%, 10%, 20%, and 40% industrial waste: (a) ”dry set” condition and (b) ”wet set” condition [121].

5.5. Summary and Discussion

At the mixture level, the studies reviewed in Section 5 generally suggest that lignin can improve rutting resistance and moisture resistance when introduced in appropriate dosages and mixture designs, whereas its effects on low-temperature cracking and fatigue life are more complex and sometimes even contradictory. Improvements in high-temperature performance are often associated with increased binder stiffness and enhanced aggregate–binder adhesion, while moisture resistance benefits from the polar functional groups of lignin that strengthen the asphalt–aggregate interface. In contrast, low-temperature and fatigue performance are strongly influenced by how lignin is incorporated (binder replacement, filler replacement or additive), the form of lignin (powder, fiber, modified lignin) and the resulting changes in mixture air voids and stiffness.

A major limitation of the existing literature is the large variability in mixture gradations, binder grades, compaction methods, test temperatures, and loading modes, which makes it difficult to quantitatively compare absolute performance levels or to define a single “optimum” lignin content. Some of the inconsistent or opposite conclusions reported for fatigue and cracking resistance can be explained by these methodological differences and by the lack of multi-scale characterization linking binder behavior to mixture response. Consequently, the trends summarized in this section should be interpreted with caution, and future experimental programs should place greater emphasis on harmonized mixture designs, clearly defined reference materials, and systematic variation in lignin type, dosage, and incorporation method.

6. Distribution and Action Mechanism of Lignin in Asphalt

6.1. Distribution of Lignin in Asphalt

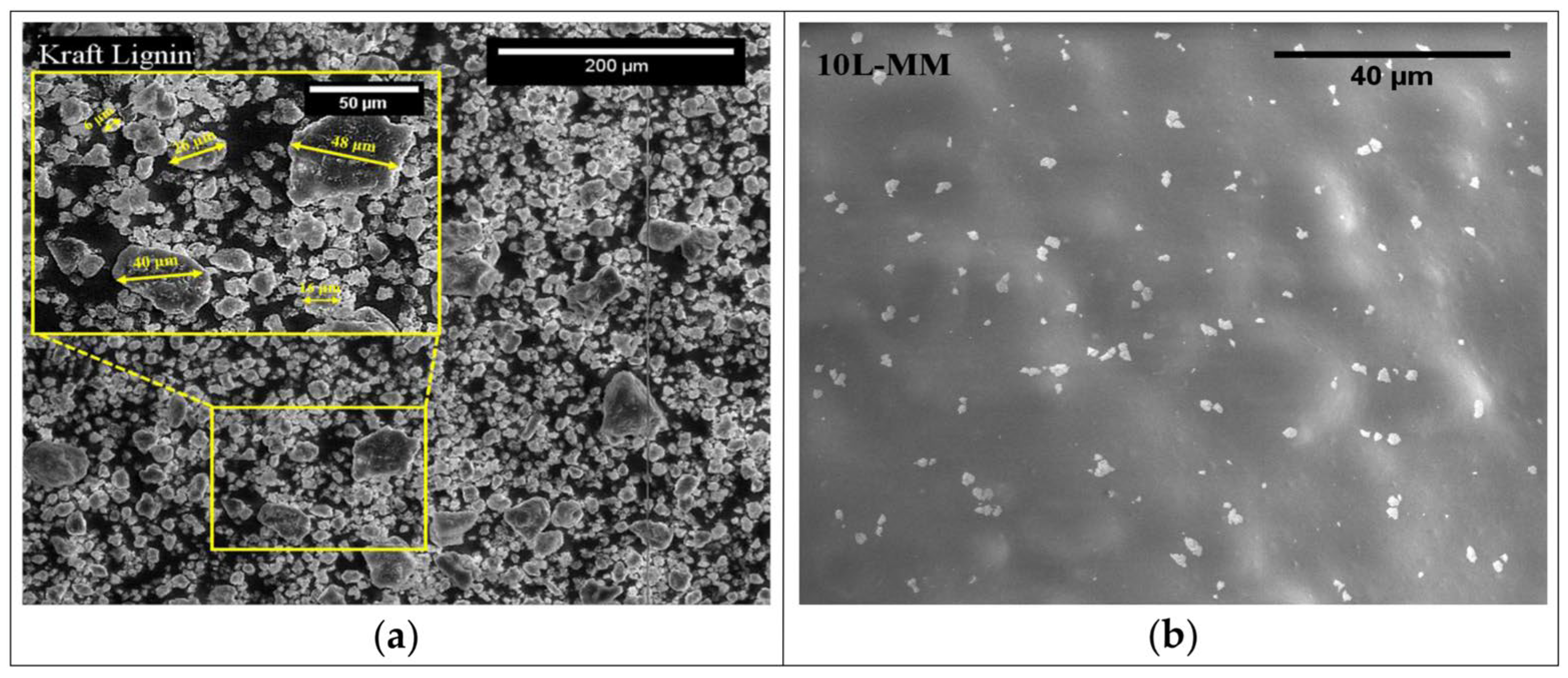

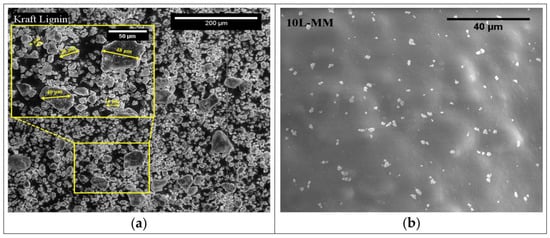

Lignin is typically blended with asphalt via mechanical shearing or high-speed stirring to form a heterogeneous dispersion system. The observation made using environmental scanning electron microscopy (ESEM) in Figure 27 reveals that lignin is distributed in granular or fibrous forms within the asphalt. It was discovered that the particle size typically ranges within 2 ± 1 µm. In the asphalt with a 10% volume fraction of lignin, only 2.5% of the particles are visible, while the remainder might be absorbed or dissolved by the asphalt. The morphology is highly dependent on blending conditions, with high-shear mixing (HSM) achieving significantly better dispersion than mechanical mixing due to enhanced shear forces breaking down lignin agglomerates [4,63]. The study discovered that the lignin-based vitrimer (ELV) was well distributed in the matrix asphalt, yet phase separation existed. When the ELV content was relatively low, it displayed an irregular distribution in the form of dots or blocks; once the proportion surpassed 20%, it would aggregate into larger particles with an uneven distribution, thereby affecting the mechanical properties of the lignin-based epoxy asphalt (ELEA) [65].

Figure 27.

ESEM image of (a) kraft lignin and (b) 10L-MM sample (mechanical mixing of 10% lignin with asphalt) (magnification of ×1000) [63].

FTIR spectroscopy consistently shows that lignin–bitumen blends lack new characteristic peaks, indicating the absence of covalent bond formation. This confirms a physical blending mechanism governed by intermolecular forces. However, compatibility is highly dependent on lignin type; organosolv and kraft lignins demonstrate better miscibility than native lignins due to differences in molecular weight and functional group density [143]. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations demonstrate that lignin forms both intramolecular and intermolecular hydrogen bonds with bitumen components, particularly with 1,7-dimethylnaphthalene (a model aromatic compound) [144]. Additionally, lignin occupies free volume within the bitumen matrix and absorbs light saturates/aromatics, restricting molecular mobility of the saturate fraction—a phenomenon confirmed by mean space displacement (MSD) analysis. This “molecular confinement” effect strengthens lignin–bitumen interactions without altering chemical structures.

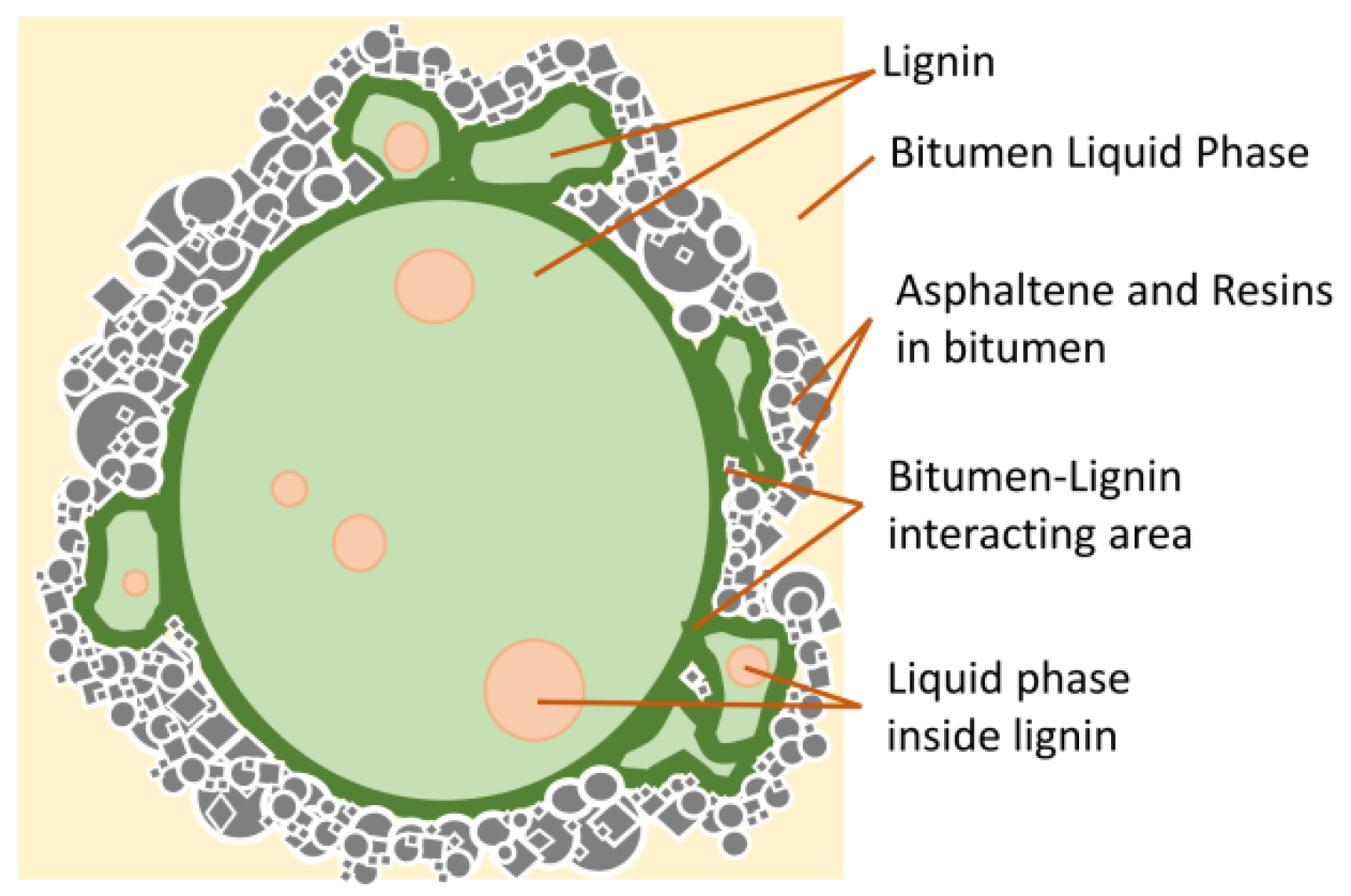

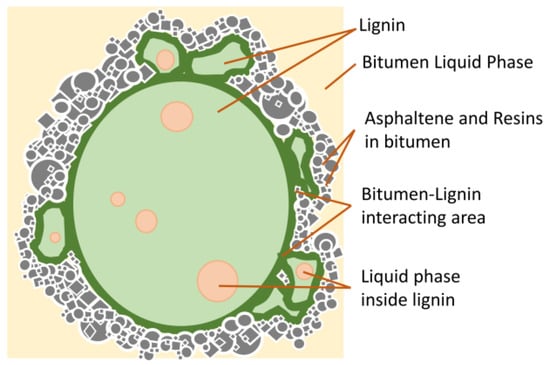

6.2. Action Mechanism of Lignin in Modified Asphalt

Lignin is a rigid biopolymer whose particles can be evenly spread in asphalt to form a physical filling network, which boosts the asphalt’s mechanical strength. It creates a 3D network inside the asphalt. Here, the polar groups in lignin (e.g., hydroxyl and methoxy groups) interact with the light components of asphalt (like aromatics and resins) via physical adsorption. This process raises viscosity and enhances the asphalt’s high-temperature performance [145]. Both kraft lignin and organosolv lignin exhibit properties similar to polymer-modified bitumen (PMB), significantly enhancing the high-temperature rutting resistance of asphalt, albeit at the expense of fatigue life. In contrast, soda lignin not only improves high-temperature stability but also uniquely enhances fatigue performance while reducing temperature susceptibility [146]. This behavior is primarily attributed to soda lignin’s higher phenolic hydroxyl content and lower glass transition temperature, which facilitate lower processing temperatures and stronger interactions with asphalt components [147]. Organosolv lignin, owing to its high purity and low molecular weight, retains structural characteristics closer to those of native lignin, although its industrial application is limited by the costs associated with solvent recovery [148].

Figure 28 shows that incorporating lignin as a modifier permits the liquid phase of asphalt to merge into the asphalt–lignin interaction zone during mixing. This process forms an asphalt–lignin working system, which modifies the viscoelastic properties of the asphalt binder [14]. FTIR examination of lignin-modified asphalt samples displayed only the inherent peaks of lignin and asphalt, with no novel absorption peaks appearing. This implies that lignin’s modification of asphalt is via physical mixing rather than chemical reactions [22,149]. Similarly, Li and Lv, 2023 [150] employed lignin to synthesize phenolic resin (LPF) and utilized it for asphalt modification. Spectroscopic characterization demonstrated that the introduction of phenolic resin (PF), LPF, and lignocellulosic components exclusively modulated pre-existing spectral profiles in the asphalt matrix, showing complete absence of de novo peak formation or covalent group evolution. As a result, the modification process involved non-chemical alterations.

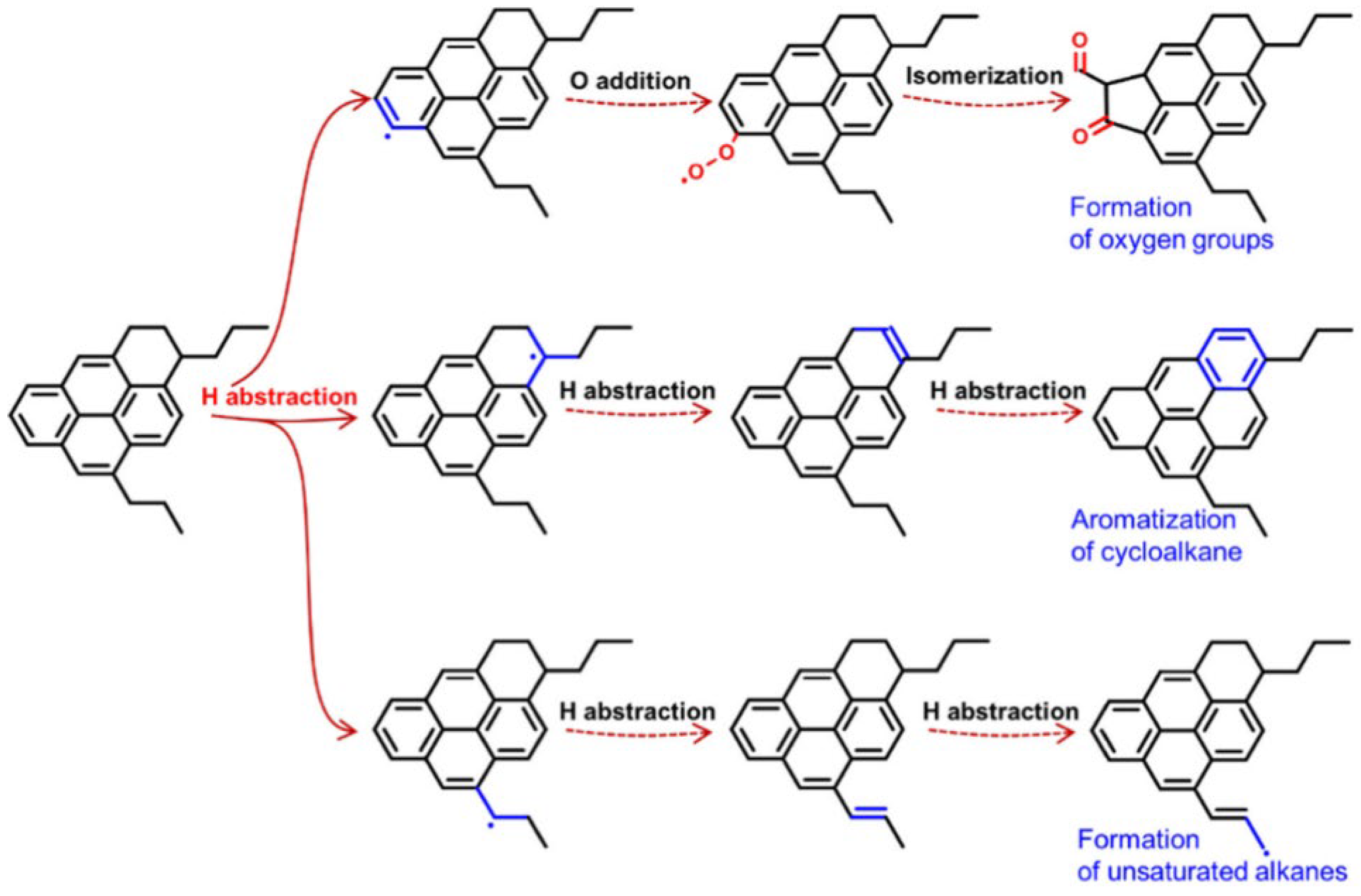

Figure 28.

Diagram illustrating the mechanism of the bitumen–lignin working system [14].

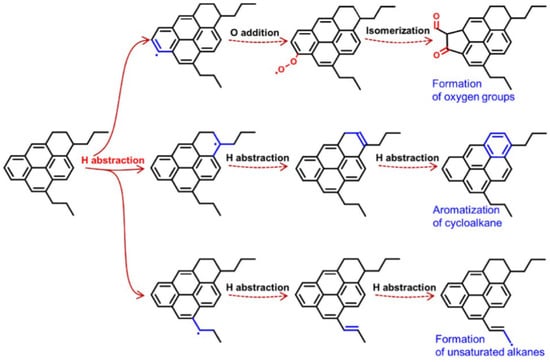

Lignin’s rigid aromatic backbone and high glass transition temperature (Tg ≈ 90–150 °C) act as physical cross-linking points, restricting bitumen molecular chain mobility. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) confirms increased Tg with lignin content, leading to a 8–15 °C rise in the ring and ball softening point at 8–12% dosage [144]. This stiffening effect linearly correlates with lignin concentration, as lignin particles reinforce the bitumen matrix through mechanical interlocking. The hardness increment stems from two mechanisms: (1) lignin’s intrinsic rigidity increases bulk viscosity, and (2) dispersed particles provide mechanical resistance against needle penetration. Studies employing atomic force microscopy (AFM) and molecular modeling have indicated that an opposing force acts between lignin and water molecules. This force inhibits water molecules from interacting with colloidal molecules in asphalt, thus boosting the moisture damage resistance of asphalt. Lignin molecules have a strong binding affinity for asphaltenes and certain saturated components. This reduces the honeycomb structure size in lignin-modified asphalt and prevents the nanostructure of asphalt from changing after water damage [151]. Li et al., 2025 [152] employed a water/ethanol stepwise solvent fractionation approach to purify sodium lignosulfonate (FL). The fractions F4 and F5 of lignin, when incorporated into asphalt for modification, exhibited excellent anti-aging properties. Having lower molecular weights, F4 and F5 probably contain a greater number of phenolic hydroxyl groups in their chemical structures, which can capture the free radicals (such as ·OH, ROO·) that accelerate asphalt aging, interrupt the oxidative chain reaction of asphalt, and thereby retard aging. During asphalt aging, as Figure 29 shows, the hydrogen abstraction reaction on the C–H bond is usually the initial and rate-determining step [153]. Through experiments and computations, it was discovered that the hydrogen abstraction reaction exerts a crucial role in the aging process of O2 and free radical asphalt and initiates other reactions. Additionally, the phenolic hydroxyl groups on lignin possess a strong hydrogen atom transfer capability and exhibit a positive local electrostatic potential, which have the effect of attracting oxidants and preventing them from extracting hydrogen atoms from asphalt, thereby retarding the aging of asphalt [154].

Figure 29.

H abstraction reactions take place at the earliest stage of asphaltene aging, serving as prerequisites for other subsequent subreactions [154].

7. Environmental Benefit Analysis of Lignin-Modified Asphalt Mixture

Life cycle assessment (LCA) evaluates environmental impacts by following a product or process through its life cycle. The two primary approaches are cradle-to-gate, which assesses impacts from raw material extraction up to the point the product leaves the factory, and cradle-to-grave, which extends the assessment to include transportation, use, and final disposal. LCA can quantify the carbon footprint in the manufacturing, usage, and recycling stages, and assist in optimizing the environmental performance of clean energy technologies [155]. Numerous researchers have employed the LCA evaluation approach to conduct an examination of the environmental benefits associated with lignin-modified asphalt mixtures. The research has revealed that employing lignin to substitute for more than 50% of petroleum asphalt can result in a decrease of roughly 27% in greenhouse gas emissions [156]. Tokede et al., 2020 [157] assessed the life cycle of lignin as an asphalt binder for road pavements in Australia and discovered that the addition of 25% lignin could decrease greenhouse gas emissions by 5.72% during the asphalt production process. Yue et al., 2022 [158] examined the environmental effects of incorporating lignin fibers and/or diatomite powder into asphalt mixtures. A comparison of these effects between the modified asphalt mixtures and the control mixture was also conducted. The results indicated that the lignin fiber-modified asphalt mixture (LFMAM) demonstrated the most pronounced negative environmental impacts in all categories. In contrast, the diatomite-modified asphalt mixture (DMAM) exhibited the lowest negative environmental impact and could be considered an environmentally advantageous option among all types of modified asphalt mixtures. Wang et al., 2025 [159] conducted a probabilistic assessment of climate impacts on conventional and four lignin-modified asphalt pavements using Monte Carlo simulations to account for parameter uncertainties. They further explored different scenarios influenced by elements like tree rotation cycles and pavement lifespans. The research discovered that the pavement climatic impact of lignin-modified asphalt mixtures was relatively low; however, the related emissions during lignin production would counteract its benefits. If recycled lignin-based asphalt is adopted, it could reduce approximately 200 million tons of greenhouse gas emissions globally.

The indicators that affect the life cycle assessment (LCA) of lignin-modified asphalt mixtures mainly pertain to environmental and performance categories. Global warming potential (GWP) is employed to measure greenhouse gas emissions. Acidification potential (AP) is associated with the emissions of acidic gases such as sulfur oxides and nitrogen oxides. Eutrophication potential (EP) is induced by the emissions of nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus. Lignin-modified asphalt, owing to its bio-based properties, can reduce the utilization of fossil raw materials. Nevertheless, its production and transportation processes might increase energy consumption, and during the extraction and transportation of lignin, nitrogen oxides and sulfur oxides will be emitted, resulting in controversies over the GWP, AP, and EP indicators [160,161]. The environmental benefits are greatest if lignin is sourced from waste black liquor or extracted through green chemical methods; however, if energy-intensive chemical extraction processes are employed, the environmental burden will increase significantly [162]. Lignin-modified asphalt may have a relatively high load during the production stage, and during the construction stage, it may require additional mixing time or specific construction temperatures, which may result in additional carbon emissions during material transportation and construction [160]. However, if it can significantly enhance the crack resistance or water-damage resistance of the pavement and extend the pavement’s lifespan, the early load can be offset during the usage stage, especially by reducing maintenance and repaving [163]. There exists a direct correlation between the durability of asphalt mixtures and their environmental impacts. Higher durability will the lower the environmental impact. Sensitivity analysis reveals that the transportation process has the most significant influence on photochemical oxidation potential (POCP) and global warming potential (LAC), while the impact on eutrophication (EP) mainly stems from the raw material supply stage [164]. The material circularity index (MCI), developed by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, is utilized to evaluate the extent of material circularity in products or systems, with a value range spanning from 0 (a purely linear economy) to 1 (a fully circular economy) [165]. The MCI value of lignin-based roads is marginally superior to that of asphalt-based roads (approximately 1% better). Lignin, as a bio-based material, reduces linear resource consumption through regeneration and biodegradation. Nevertheless, its proportion in the total asphalt mass is small (for instance, merely 4% in SMA), thereby the increase in MCI is limited. The analysis of the circularity index (BCS) demonstrates that lignin-modified asphalt exhibits better performance in long-term circularity due to its carbon sequestration potential [161].

8. Conclusions

Lignin, as a natural polymeric material, has witnessed remarkable research advancements in its application for asphalt modification. This article undertakes a review on lignin-modified asphalt. It investigates the application differences between dry and wet processes in its preparation, elucidates the performance enhancement mechanism of modified asphalt, compares the pavement performance of mixtures, and highlights the advantages of lignin as a modifier. Simultaneously, it elucidates the way lignin retards asphalt aging from the aspect of the action mechanism and assesses its environmental benefits from a full life cycle perspective, offering theoretical and technical support for the development of sustainable road materials. This article is summarized as follows:

- Lignin, as an abundant biomass resource, is mainly extracted from papermaking black liquor or agricultural and forestry residues through multiple processes such as the kraft process and pyrolysis. Chemical modification can optimize the compatibility of lignin with asphalt. For example, oxidation, ammoniation or fractionation treatments can regulate the molecular weight distribution and surface properties, thereby improving the performance of modified asphalt. These processes offer technical support for the high-value utilization of lignin in road engineering.

- Lignin-modified asphalt is mainly fabricated through the physical blending method. For lignin-modified asphalt mixtures, there exist two techniques, namely the dry process and the wet process. The dry process is operationally straightforward but has relatively poor dispersion. The wet process offers uniform dispersion yet comes with a higher cost. Both processes have their distinct features in terms of lignin content, equipment requirements, and road performance.