Abstract

In Louisiana’s marsh creation projects designed to mitigate wetland loss, riverine sediments are hydraulically dredged and transported through pipelines. These dredged materials are extremely soft, with moisture contents well above 100%, resulting in significant consolidation settlements even under minimal self-weight loads. Conventional one-dimensional (1-D) oedometer consolidation tests are commonly used to assess consolidation behavior; however, they are limited to soils with much lower moisture contents. At higher moisture levels, the soft slurry tends to overflow due to the weight of the standard stainless-steel dial cap and porous stone, which together apply a seating pressure of 1.07 kPa (0.01 TSF). This study presents a modified oedometer setup utilizing 3D-printed dial caps made from lightweight materials such as polylactic acid (PLA) and acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS), reducing the seating pressure to 0.21 kPa (0.002 TSF). This modification enables the testing of dredged soils with moisture contents up to 100% without overflow. Settling column tests were also integrated with the modified oedometer tests, allowing for the development of void ratio–effective stress relationships spanning from 0.02 kPa (0.0002 TSF) to 107.25 kPa (1 TSF). The results demonstrate that combining settling column and modified oedometer tests provides an effective approach for evaluating the consolidation behavior of high-moisture slurry soils.

1. Introduction

Several ongoing and completed coastal protection and restoration projects in Louisiana involve creating marshes in open coastal areas by hydraulically dredging riverine sediments and transporting them through pipelines. The settlement behavior of fine-grained dredged soils is routinely monitored and predicted, and laboratory consolidation testing serves as an essential tool for characterizing the settlement of marsh soils. In this study, a standardized laboratory method is recommended to enable the full utilization of conventional oedometers and other laboratory equipment for consolidation testing. The proposed techniques incorporate procedures outlined in Terzaghi [1], EM 1110-2-19062 [2], Gibson et al. [3], Appendix D of EM 1110-2-5027 [4], Method B of ASTM D2435 [5], the Geotechnical Standards of the Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority [6], and the method proposed by Azimi [7]. This research aims to experimentally investigate dredged soil sediments from coastal wetlands through the application of 3D-printing technology in the development of a modified oedometer. Although various specialized devices have been developed to characterize the consolidation behavior of highly saturated dredged soils, many require complex, non-standard equipment or are not readily compatible with conventional oedometer systems commonly used in routine geotechnical laboratories. As a result, there remains a practical need for a simple and adaptable modification that extends the applicability of standard oedometer testing to high-moisture slurry soils.

Louisiana’s marsh creation projects, led primarily by the Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority (CPRA), play a critical role in mitigating rapid coastal wetland loss and enhancing long-term coastal sustainability. Between 1932 and 2010, Louisiana lost more than 1800 square miles of coastal land, with continued losses driven by subsidence, sea-level rise, hurricanes, altered sediment supply, and human activities. Marsh creation through the hydraulic dredging of riverine sediments has emerged as a cornerstone restoration strategy, enabling the rebuilding of marsh platforms, attenuation of storm surge, and preservation of critical ecological habitats. The long-term performance and sustainability of these projects depend strongly on the consolidation behavior of the placed dredged sediments, as excessive settlement can compromise marsh elevations, containment dike stability, and project effectiveness. Consequently, reliable laboratory methods for characterizing the consolidation behavior of high-moisture dredged soils at very low effective stresses are essential for accurate settlement prediction, informed geotechnical design, and the successful implementation of CPRA’s coastal restoration initiatives.

Dredged soils are soft and highly moisturized, and thus form a large strain deformation. In the conventional consolidation oedometer test, the seating load at the initial consolidation test stage is an essential factor for the consolidation test of dredged soils. The conventional oedometer comes up with a seating pressure of 1.07 kPa (0.01 TSF), including the weight of the stainless-steel dial cap and the porous stone, which could ensure the success of testing soil samples with a moisture content up to 70% for the dredged soils [8]. For this reason, we focused our research attention on how to modify the conventional 1-D consolidation test to allow for the handling of slurry samples with higher moisture contents. As the first modification, the small-scale settling column test is used to handle those slurry samples with high moisture contents (>=70%). For a dredged soil sample with a water content greater than 70%, after it was moved into the 1-D oedometer, as soon as the conventional stainless-steel dial cap was placed, which was equivalent to the initial (seating) pressure of 1.07 kPa (0.01 TSF), a portion of the soil specimen would be squeezed out of the consolidation ring [9]. Therefore, the conventional 1-D consolidation test could not proceed because the traditional initial seating pressure is too high for the highly moisturized dredged soil sample.

Geotechnical researchers have devoted considerable effort to developing appropriate settling column apparatuses for assessing the consolidation properties of very soft, slurry-like dredged soils. Pioneering this field, Monte and Krizek [10] introduced a settling column apparatus measuring 20 cm in diameter and 50 cm in height for one-dimensional consolidation testing, coupled with a hydraulic conductivity test, to investigate a kaolinite clay slurry with an initial water content of about 250% (approximately four to five times its liquid limit). Their study demonstrated an effective consolidation of the slurry under low effective stresses and provided valuable insights into the consolidation behavior of such materials. Carrier and Keshian [11] conducted a 30-day settlement test on a mud layer, deriving average void ratios and effective stresses to establish critical data points on a compressibility curve. Similarly, Katagiri and Imai [12] developed an apparatus consisting of a removable sedimentation pipe, a pre-consolidation pipe, and a piston to investigate the influence of initial water content on the compressibility, hydraulic conductivity, and settlement characteristics of highly saturated clays. They tested samples with varying water contents prepared from the same soil. Imai [13] also examined the settling behavior of slurries with different initial water contents, exploring correlations between water content, solid particle concentration, and settlement characteristics, yielding important findings. In addition, Sridharan and Prakash [14] investigated the compressibility behavior of both segregated and homogeneous fine-grained sediments consolidated under self-weight conditions. Using glass jars with a diameter of 6.1 cm, they carefully sampled the consolidated soils layer by layer with a horizontal-ended spatula to precisely determine moisture content, which was essential for calculating the void ratio.

Cuthbertson et al. [15] studied sand/clay sedimentation in estuaries and tidal inlets by performing settling column tests and taking electrical resistivity measurements to determine the consolidation behavior, which was validated by a hindered settling model. François and Corda [16] investigated the one-dimensional self-weight consolidation of dredged mud, proposing two original experiments to determine constitutive relations. At the end of their research, they recommended conducting self-weight consolidation tests in plexiglass columns. Been and Sills [17] conducted experimental research on the consolidation of soft soil in a settling column, with measurements of density (using an accurate, non-destructive X-ray technique), total stress, pore pressure and settlement, revealing their susceptibility to wall friction compared to those with individual particles or flakes. Furthermore, Gao et al. [18] extensively investigated the settling behavior of dredged materials, revealing the diminishing impact of column wall effects with an increasing column diameter, making them negligible for settling columns larger than 14.5 cm. This critical insight influenced the selection of the appropriate cylinder size for our research endeavors. Moreover, Gibson et al. [3,19] along with Cargill [20,21,22], authored technical reports and papers for the United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), introducing a practical approach based on finite strain consolidation principles. The USACE method, introduced in 1986, utilizes a specialized 15.2 cm (6 inches) plexiglass apparatus consisting of 18 internal rings, each measuring 1.3 cm (½ inch) thick. This method allows for moisture content analysis, establishing the void ratio–effective stress relationship, and it provides valuable insights into soil consolidation properties.

Recently, Shi et al. [23] developed a filtration device to test dredged slurries’ compressibility and permeability. A geotextile-type filter was employed in the device, and it consists of a cubic vacuum chamber, a Buchner funnel, a vacuum control system, and a monitoring setup. It allows for filtration and consolidation under different vacuum pressures, collecting and quantifying the filtrate for further analysis. Similarly, Lee et al. [24] conducted self-weight consolidation tests in a cylindrical acrylic chamber with added features like valves and piezometers for measuring pore water pressure. Khaleghi et al. [25] introduced a complex oedometer to assess the thermal, hydraulic, and mechanical behavior of geomaterials, featuring a loading system, thermal setup, linear vertical displacement transducer (LVDT), pore–water pressure measurement, pressure cells, and data logger. Its corrosion-resistant interior and airtight cylindrical chamber provides unique insights. However, its complexity presents challenges in laboratory implementation and development.

In this study, small-scale settling column tests and one-dimensional (1-D) consolidation tests using a modified oedometer were combined to evaluate slurry samples with water contents exceeding 100%. This approach enabled the characterization of consolidation behavior across a wide range of void ratios and effective stresses. 3D-printing technology was employed to fabricate the dial cap using polylactic acid (PLA) and acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) materials. The use of 3D printing enabled the precise control of component geometry and weight, allowing a significant reduction in seating pressure while providing a cost-effective, easily reproducible, and rapidly deployable alternative to conventional manufactured components. A successful outcome was achieved, as the newly developed setup reduced the seating pressure significantly to 0.21 kPa (0.002 TSF), including the weight of the porous stone. Consequently, with the 3D-printed dial cap, dredged soil samples with moisture contents up to 100% could be successfully tested for their consolidation properties using the modified oedometer test. Simplified acrylic settling columns were also utilized to perform self-weight consolidation tests. Combined with the results from the settling column tests, the void ratio–effective stress relationship could be extended to stresses below 0.21 kPa (0.002 TSF).

2. The Dredged Soil Properties and Slurry Sample Preparations

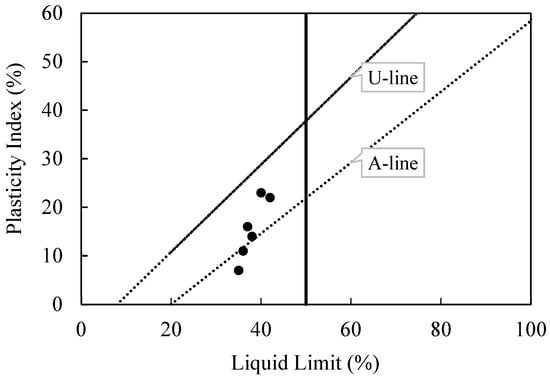

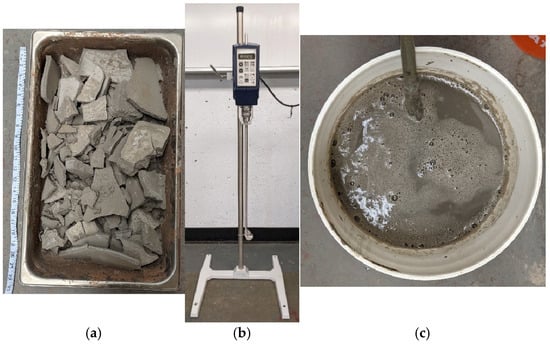

The slurry soil samples used in the studies were made using the soil mass excavated from the No-Name Bayou Swamp production site in coastal Louisiana. These samples represented the natural state of the dredged soils. Prior to the consolidation tests on the slurry soil samples, fundamental geotechnical lab tests were conducted. According to the Unified Soil Classification System (USCS), as detailed by Howard [26], the dredged soil samples were classified as clays with low plasticity (CL). The specific gravity (GS) was found to be 2.6 [9], in accordance with ASTM D854 [27]. Additionally, Atterberg limits, as per the ASTM D4318 [28] standard, were measured and shown in Figure 1 [9]. To prepare the slurry soil samples, the soil mass was initially dried in an oven for 24 h, as depicted in Figure 2a, and then ground into a finer consistency. The ground dry soil mass served as the initial material for creating the slurry samples. Water was added to the crushed dry soil to produce a uniform slurry with a targeted moisture content. This wet soil sample was then transferred to a mixing bucket for a thorough blending until it became homogeneous slurry, as illustrated in Figure 2b,c. The produced slurry samples had three different moisture contents: 210.1%, 180.3%, and 150.2%. In order to mimic the natural environment and reduce the initial moisture content prior to initiating oedometer tests, self-weight settling column tests were conducted.

Figure 1.

Atterberg limits of the soil samples from the No-Name Bayou Marsh Creation site in coastal Louisiana.

Figure 2.

(a) Oven-dried soil sample. (b) Mixing grinder. (c) Prepared slurry sample for settling column consolidation test.

3. The Simplified Self-Weight Consolidation Method

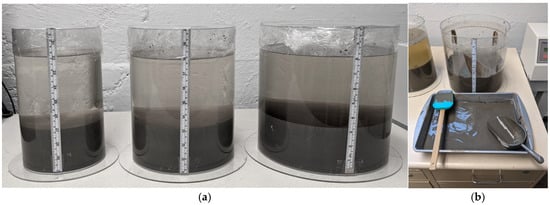

The self-weight settling column consolidation tests were conducted before the conventional 1-D oedometer tests started. Once a slurry sample was prepared with a pre-designed initial moisture content, it was moved in a settling cylinder for the self-weight consolidation test. In this research, three different diameters of acrylic plexiglass cylinders were utilized with the same height as 25.4 cm (10 inches). Those cylinders were 15.2, 20.3 and 25.4 cm (6, 8, and 10 inches) in inner diameters, respectively, as shown in Figure 3a. A measuring tape marked with a scale in millimeters was attached to the side of each settling cylinder to take the settlement readings (location of the interface of water/top surface of settled soils). The cylinders were initially filled with slurry approximately to a depth of 20.3 cm (8 inches).

Figure 3.

(a) The self-weight consolidation/settling column tests using acrylic plexiglass cylinders with diameters 25.4 cm, 20.3 cm, and 15.2 cm (10″, 8″, and 6″) (right to left). (b) Soil sample removal after completion of a self-weight consolidation test.

In the USACE method [22] for self-weight settling column tests, the used plexiglass apparatus was complex and uncommon, leading to difficulties in replication and procurement due to its rarity. Potential leakage in the USACE equipment is a notable concern, as even minor leaks could affect the test results by creating additional drainage paths in the sample. In contrast, the proposed research suggests the use of readily available acrylic plexiglass cylinders from common stores, offering a smoother surface, reducing friction during the test, and providing a reliable containment system for slurry samples, ensuring more dependable and accurate results.

Upon placing the testing cylinder containing the prepared slurry sample, the self-weight settling column test commenced, with intermittent measurements focused on identifying the water/slurry interface. The readings were taken at specific time intervals of 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 15, 30, 60, 120, and 240 min, and then twice daily, following the methodology outlined by Azimi et al. [29]. Throughout the test, close attention was paid to the slurry’s consistency, clarity of the discharged water, and any indications of agglomeration within the slurry. If approximately no additional settlement was observed for one week, it would be considered that the self-weight settling column test is accomplished. In the lab experiments, no significant changes were observed in the settlement of the slurry sample after four weeks. Consequently, it was taken into consideration that the ideal period for the completion of a settling column test is four weeks.

Each test took nearly four weeks to complete the self-weight consolidation. Once the self-weight consolidation test was completed, the free water on the top of the cylinder, which was expelled out of the original slurry, was gradually poured out, and the amount of the free water was measured. Upon the completion of each settling column test, the settled soils were prepared for the modified oedometer consolidation tests. Firstly, a hand pump was utilized to remove the water from the top of the settling cylinder. Then, the settled soil was removed layer by layer and placed on a tray for moisture content measurements, as demonstrated in Figure 3b. Soil specimens were collected from various depths to perform oedometer consolidation tests. After the completion of the settling column tests, the average moisture content of the settled soils was around 150% on the top, and it decreased to about 60% at the bottom of the settling column cylinder [9], as shown in Figure 3a. To determine the moisture contents, multiple soil samples were taken at the same depth and tested following the procedures outlined in ASTM D2216 [30].

The settlement vs. time plot from the settling column tests were employed to specify the first part of the primary consolidation curve. In the research, the effect of the cylinder diameter, i.e., effect of the friction between the cylinder wall and slurry soils, was studied on the self-weight consolidation settlement. Three acrylic plexiglass cylinders, as shown in Figure 3a, with diameters of 25.4, 20.3, and 15.2 cm (10, 8, and 6 inches, respectively) were used to find out an acceptable minimum cylinder diameter.

In the research presented in this paper, we conducted settling column tests following the well-established methodology proposed by Azimi et al. [29], which aligns with the original USACE method described by Cargill [22]. To determine the location of the slurry/water interface, measurements were recorded prior to extracting the free water using a manual pump. Careful sampling was then conducted to collect test specimens in layers of an approximately equal thickness, around 2.54 cm (1 inch) each, using a precise rubber-padded spatula and trowel to ensure a minimal disturbance to the underlying layers. Figure 3b visually represents the sampling process with a test cylinder. The weight of each layer (w) was established by computing the mass per unit depth of the settled soil specimen using Equation (1). These meticulous procedures allowed us to compute the effective stresses and void ratios in each settling column test, contributing to a comprehensive understanding of the soil’s behavior under specific conditions.

The experimental procedure involved comprehensive measurements of the slurry’s properties. The total weight of the slurry-containing cylinder () was determined after eliminating all free-standing water, and the empty cylinder weight () was measured before conducting the test. After the completion of the test, we recorded the ultimate vertical depth of the slurry (). Sampling was conducted meticulously, with the one-inch-thick layer’s mass calculated using Equation (1). We acquired samples from the full depth of the tested specimen, and every extracted layer was weighed. ASTM D2216 [30] was followed for the moisture content determination, and the test was performed in a controlled oven at a constant temperature of 110 °C ± 5 °C. The test results were analyzed and are presented in the Results and Discussion section.

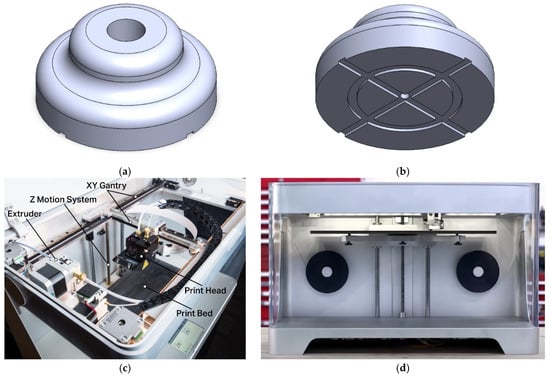

4. 3D Printing of the Dial Caps

In the process of creating the new dial caps for the modified oedometer test using SOLIDWORKS 2022 software, it is crucial to develop a meticulous 3D model that adheres to precise specifications and dimensions. This involves utilizing the software’s diverse array of tools and features to craft detailed sketches, extrusions, and cuts that will form the part. Once the model is completed, it must be exported in a compatible format for 3D printing. The sketch of the dial cap and the MARKFORGED 3D printer are shown in Figure 4 below.

Figure 4.

Sketch of the dial cap using SOLIDWORKS for 3D printing: (a) top isometric view, (b) bottom isometric view; MARKFORGED 3D printer: (c) different components [31], (d) printing dial cap. (Markforged, Watertown, MA, USA).

To bring the model to fruition, the 3D-printing process requires several critical steps. Firstly, the 3D model must be imported into the Markforged Eiger 3D printer software (Cloud-based version, Watertown, MA, USA). Subsequently, the model is sliced into numerous layers, and a tool path is generated for the printer to follow. The printer must then be configured with the appropriate materials, including PLA and ABS, for this particular application. The print settings are then fine-tuned, and the printer begins constructing the dial cap layer by layer, carefully building up the part using the designated material.

After print settings are optimized for speed, it could take approximately 3–4 h to print the part using PLA as the printing material. If ABS is used instead, the print time might increase to around 5–6 h due to the higher melting point of ABS and the need for a higher printing temperature. Upon completion of the printing process, the part is extracted from the printer, and any necessary support structures are removed. The resulting component is then ready to replace the original stainless-steel dial cap in the consolidation testing.

5. The 1-D Consolidation Tests Using the Modified Oedometer

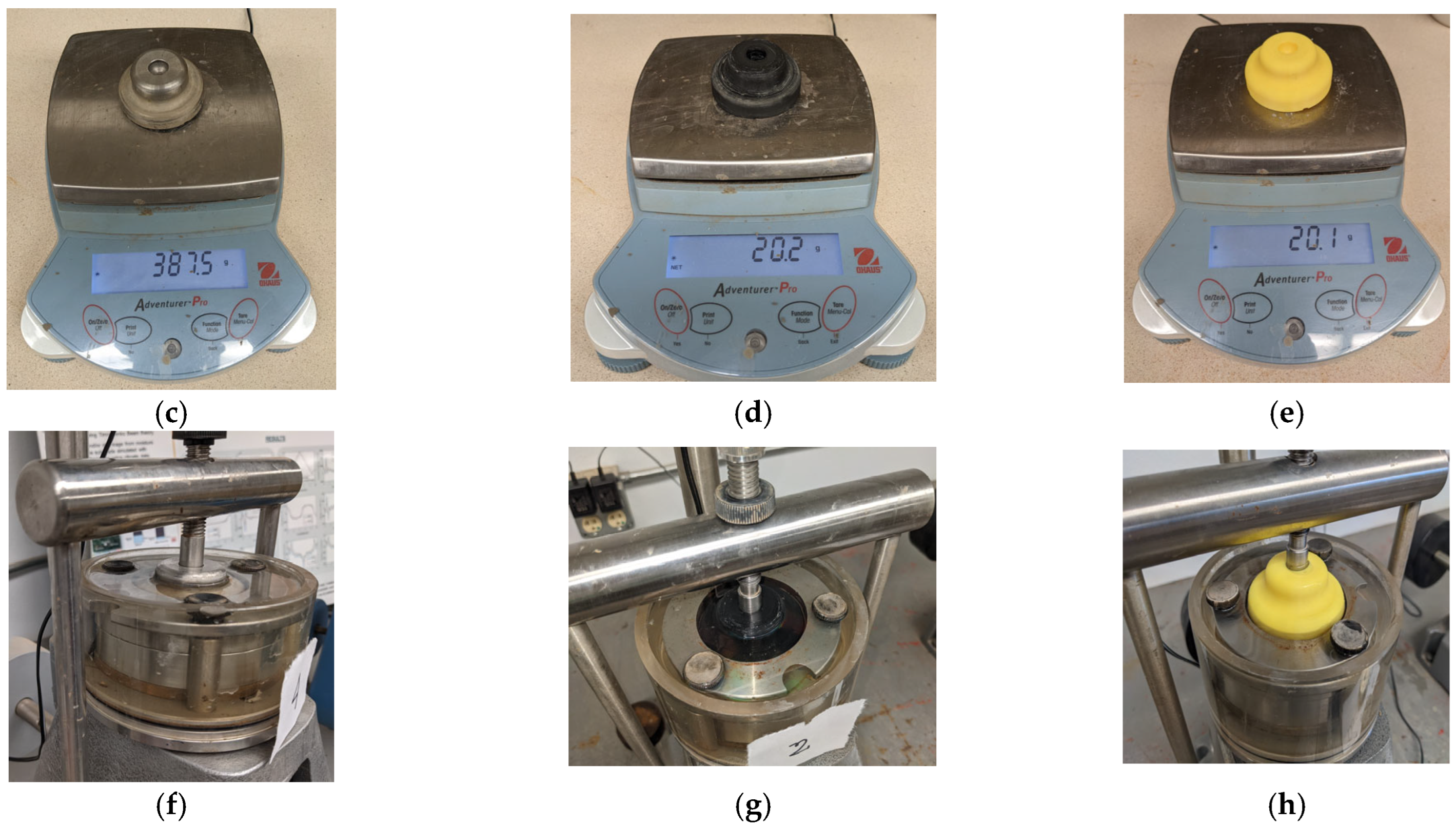

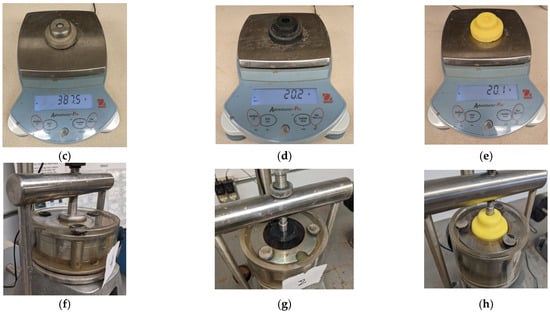

After completing the settling column tests, the consolidated slurry soils were sampled from different depths in the settling columns for the oedometer consolidation tests. Transferring soil samples from the settling column to the modified oedometer requires careful handling to minimize any disturbances. We used specialized rubber-padded spatulas and trowels to sample the consolidated soil from the settling column (Figure 3). The steel specimen ring of the oedometer, overlying the bottom piece of porous stone, was positioned within the apparatus, and the sampled soil was gently placed in the ring. Subsequently, the top porous stone and the modified dial cap were positioned to complete the setup. As presented in Figure 5, the 3D-printed dial cap weighs only 20.2 g (PLA) or 20.1 g (ABS), while the conventional stainless-steel dial cap weighs 387.5 g. As part of the justification work for the dial cap replacement, the deflections of the 3D-printed dial caps were studied on their own as well, in an effort to see how significant the deformations were. The results of finite element analyses using the software SolidWorks and the experimental test results of the deflection of the dial caps are compared in the Results and Discussion section.

Figure 5.

(a) Top views of stainless-steel, 3D-printed acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS), and polylactic acid (PLA) dial caps (left to right); (b) bottom views of stainless-steel, 3D-printed ABS, and PLA dial caps (left to right); (c) stainless-steel dial cap with a weight of 387.5 g; (d) PLA dial cap with a weight of 20.2 g; (e) ABS dial cap with a weight of 20.1 g; (f) consolidation tests in progress using stainless-steel dial cap; (g) consolidation test in progress using the PLA dial cap; (h) consolidation test in progress using the ABS dial cap.

The lightweight 3D-printed dial caps provided a significant outcome, with the newly achieved seating pressure was about 0.21 kPa (0.002 TSF), including the pressure that came up from the weight of the porous stone, as opposed to the traditional 1.07 kPa (0.01 TSF). From the preliminary results obtained, the maximum water content of the slurry soil sample was not able to go beyond 70% if the conventional stainless-steel dial cap was used. However, if the 3D-printed dial cap was used, the maximum water content of the slurry samples could go up to as high as 100%. After a slurry soil sample with a water content of 100% was tested successfully using this 3D-printed dial cap, it was observed that, at the end of the consolidation test, at a pressure of 107.25 kPa (1 TSF), the final settlement of the specimen was almost 50% of its initial height, which indicated that a large strain deformation occurred in the consolidation test. During the successful consolidation test, the following loading schedule was adopted: 0.21, 0.53, 1.07, 2.68, 5.36, 10.72, 26.81, 53.62, and 107.25 kPa (0.002, 0.005, 0.01, 0.025, 0.05, 0.10, 0.25, 0.50, and 1.00 TSF).

The 1-D consolidation tests were completed following the ASTM D-2435 [5] standard and Appendix D of EM 1110-2-5027 [4]. Consolidation settlement readings were taken at the times 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 4.0, 8.0, 15.0, and 30.0 min and at 1, 2, 4, 8, and 24 h. At the time of 24 h, the primary consolidation was completed for most of the applied load mentioned above. As the moisture content of the slurry soil specimen became significantly higher, the consolidation started immediately as soon as the soil specimen was placed in the oedometer. In every loading cycle, the settlement was much more significant in the first few hours and quickly decreased as time passed. No substantial settlement was observed in the last few hours of the 24 h loading cycle.

The modified oedometer consolidation test results were analyzed following Method B of ASTM D-2435 [5] and are presented in the Results and Discussion section. As described in the beginning of this paper, combined consolidation results were presented from both the settling column and the modified 1-D oedometer tests. Void ratio variations from the two tests were plotted against the effective stresses applied. The void ratio results at each effective stress were averaged from the three tests using different diameter settling columns, with slurry samples having the same initial moisture content. Then, those were combined with the test results obtained from the modified oedometer tests. The void ratio vs. the effective stress profile plotted covered a spectrum of consolidation pressures ranging from 0.02 kPa (0.0002 TSF) to 107.25 kPa (1 TSF).

6. Results and Discussion

6.1. The Self-Weight Consolidation Tests

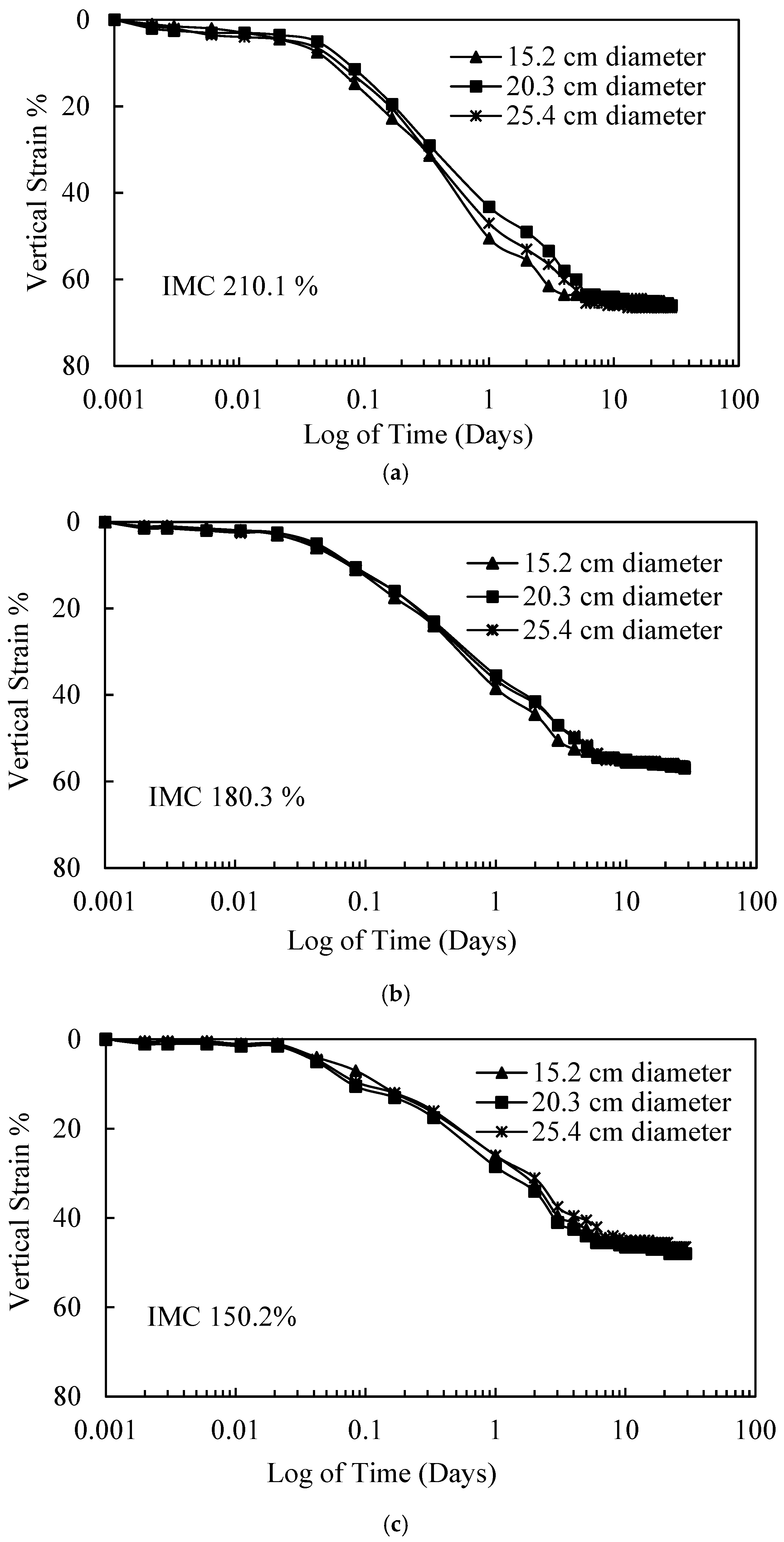

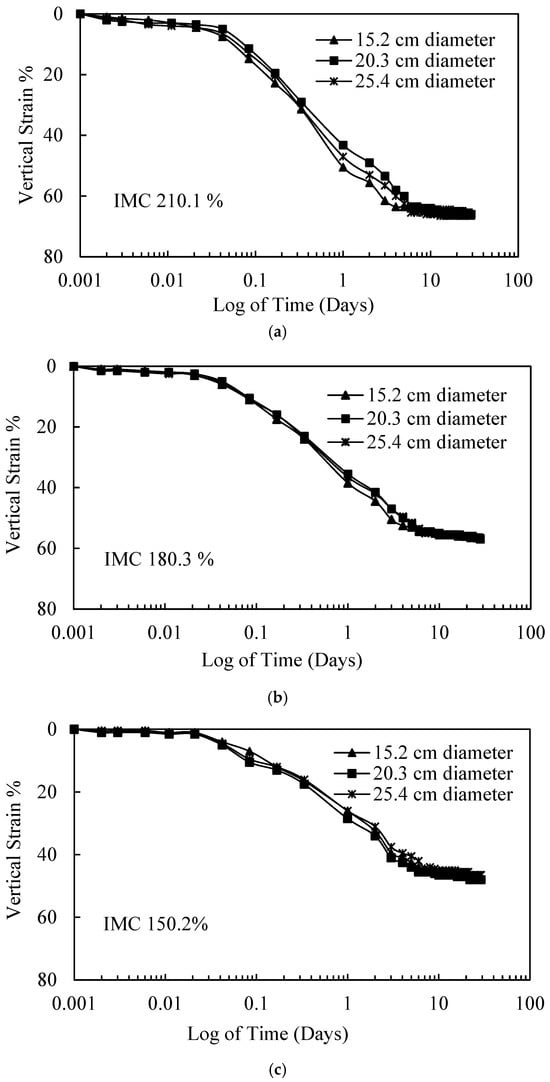

To determine the diameter effect of the settlement column, three acrylic cylinders with diameters of 15.2 cm (6 inch), 20.3 cm (8 inch), and 25.4 cm (10 inches), respectively, were used to conduct self-weight consolidation tests. The columns were constructed from new, smooth, and clean acrylic tubing [32], minimizing the friction between the slurry and the sidewall. Figure 6a–c represent the percent vertical strain against logarithmic time for the three sets of self-weight consolidation tests, in which the slurry samples had an initial moisture content of 210.1%, 180.3%, and 150.2%, respectively. On average, each test spent 28 days before ending up taking any slurry settlement readings. The settlement results from the three tests with different cylinder diameters showed that no significant differences were found among the three-diameter settling column tests. It could be concluded that any acrylic cylinders with a diameter equal to or greater than 15.2 cm (6 inch) would have a negligible frictional effect on the final consolidation settlement.

Figure 6.

(a–c) Logarithm of time vs. vertical strain of the settlement column tests with initial moisture contents of 210.1%, 180.3%, and 150.2%, respectively. IMC = initial moisture content of soil sample.

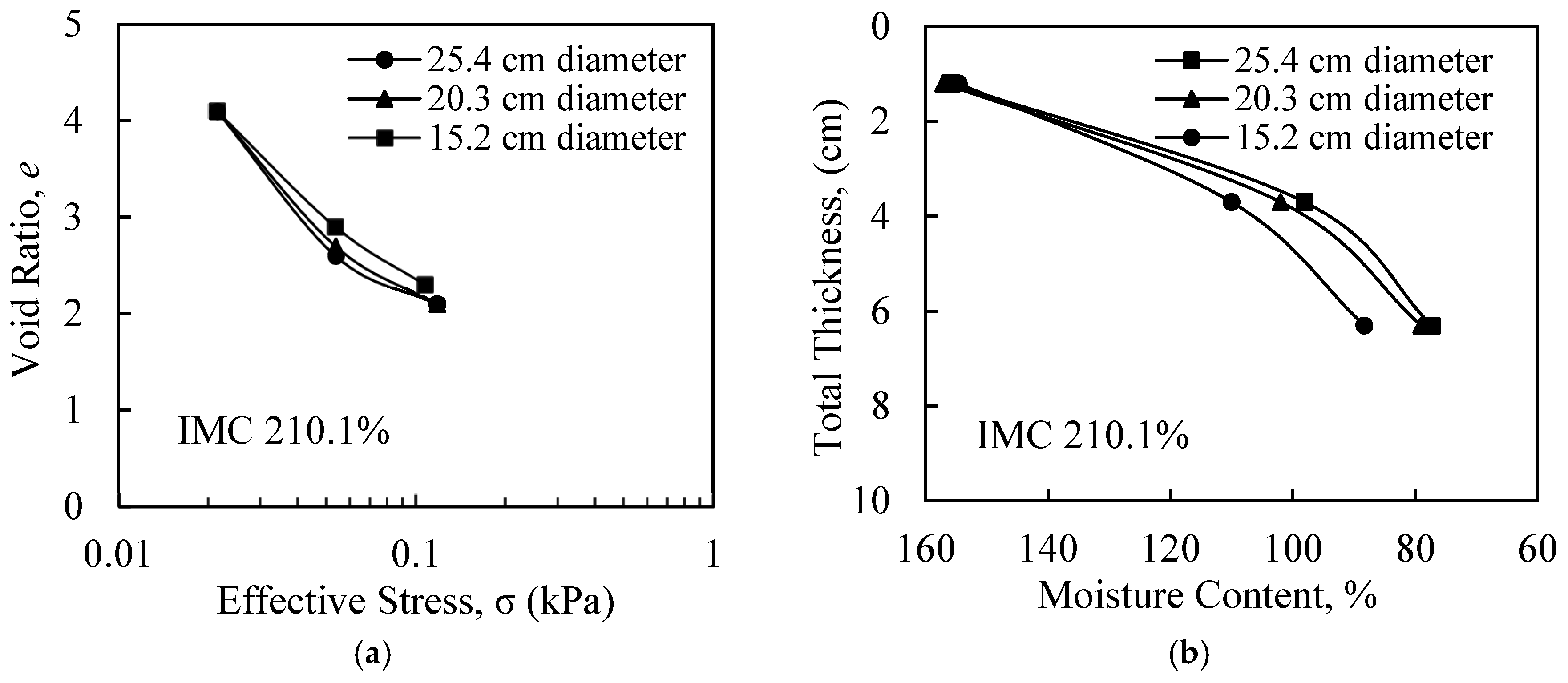

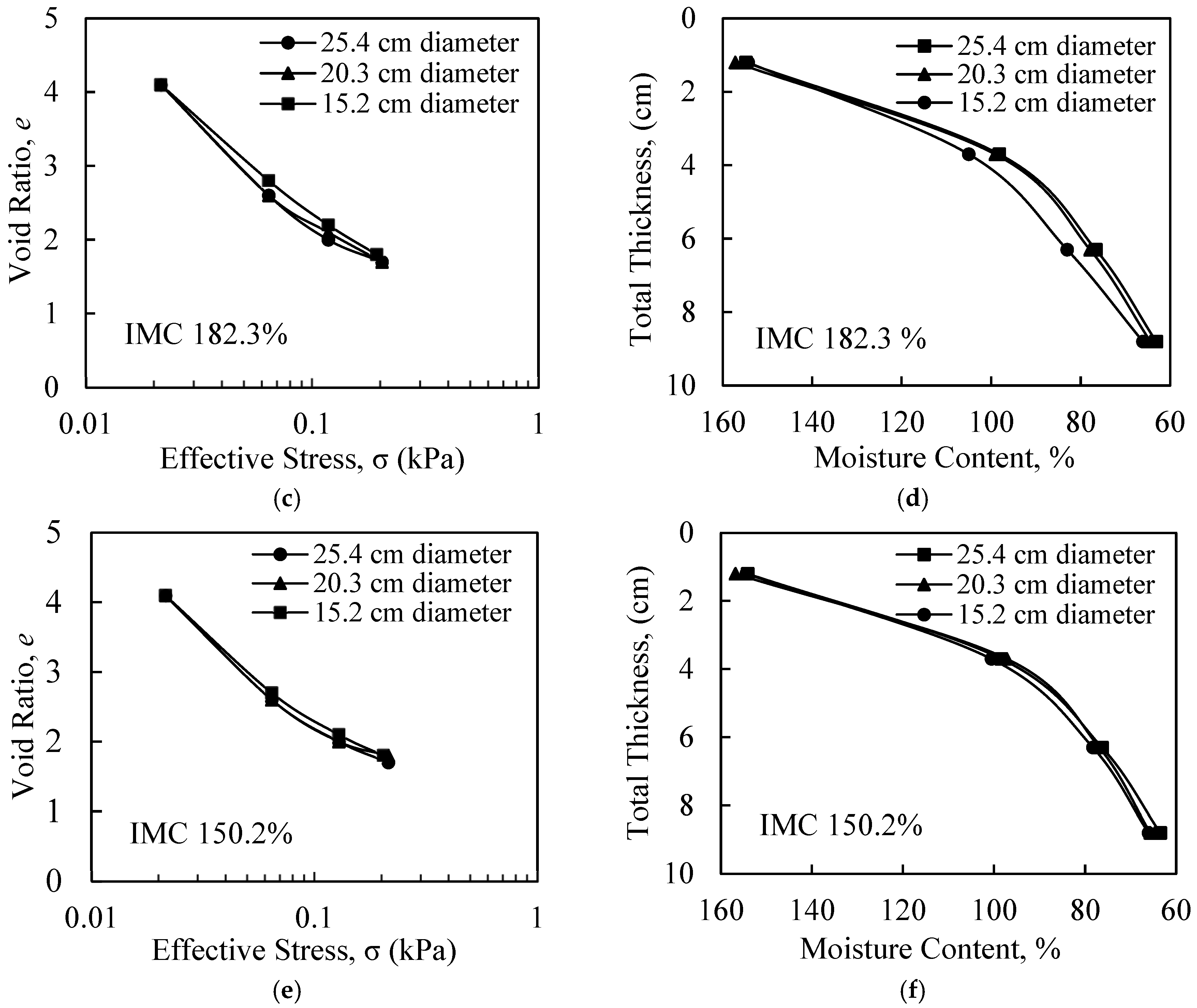

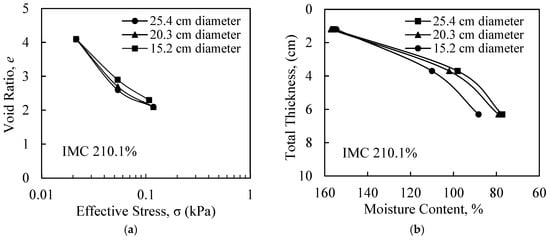

6.2. Consolidation Properties of the Slurries from the Self-Weight Tests

For the completed settling column/self-weight consolidation tests, the plots of the void ratio versus the effective stress on a semi-log scale were illustrated in Figure 7a,c,e for the slurry samples with moisture contents of 210.1%, 180.3%, and 150.2%, respectively. At each data point shown on a single plot, the results were derived from a one-inch-thick layer of the slurry specimen extracted at a particular depth within the test cylinder. Figure 7b,d,f represent the plots of the total thickness of the settled slurry soils versus the moisture content of each set of settling column test. In the settling columns, total thickness of the settled slurry was measured from the water/soil interface to the bottom, and the measured moisture content of each layer of the consolidated slurry was presented in Figure 7b,d,f. The effective stresses in each test were determined by considering the buoyancy weight of the soils within every layer. The void ratio vs. effective stress curves for dredged/marsh soils demonstrate a distinct behavior, attributed to the intricate nature of the soil composition and the dredging process. The curves show higher initial void ratios at lower effective stresses, followed by a quick decrease as the effective stress increases, indicating the gradual densification of the soil.

Figure 7.

(a,c,e) Effective stress vs. void ratio plots of the soil samples with initial water contents of 210.1%, 180.3% and 150.2%. (b,d,f) Moisture content vs. thickness of soil specimens with initial water contents of 210.1%, 180.3% and 150.2%. IMC = initial moisture content of soil sample.

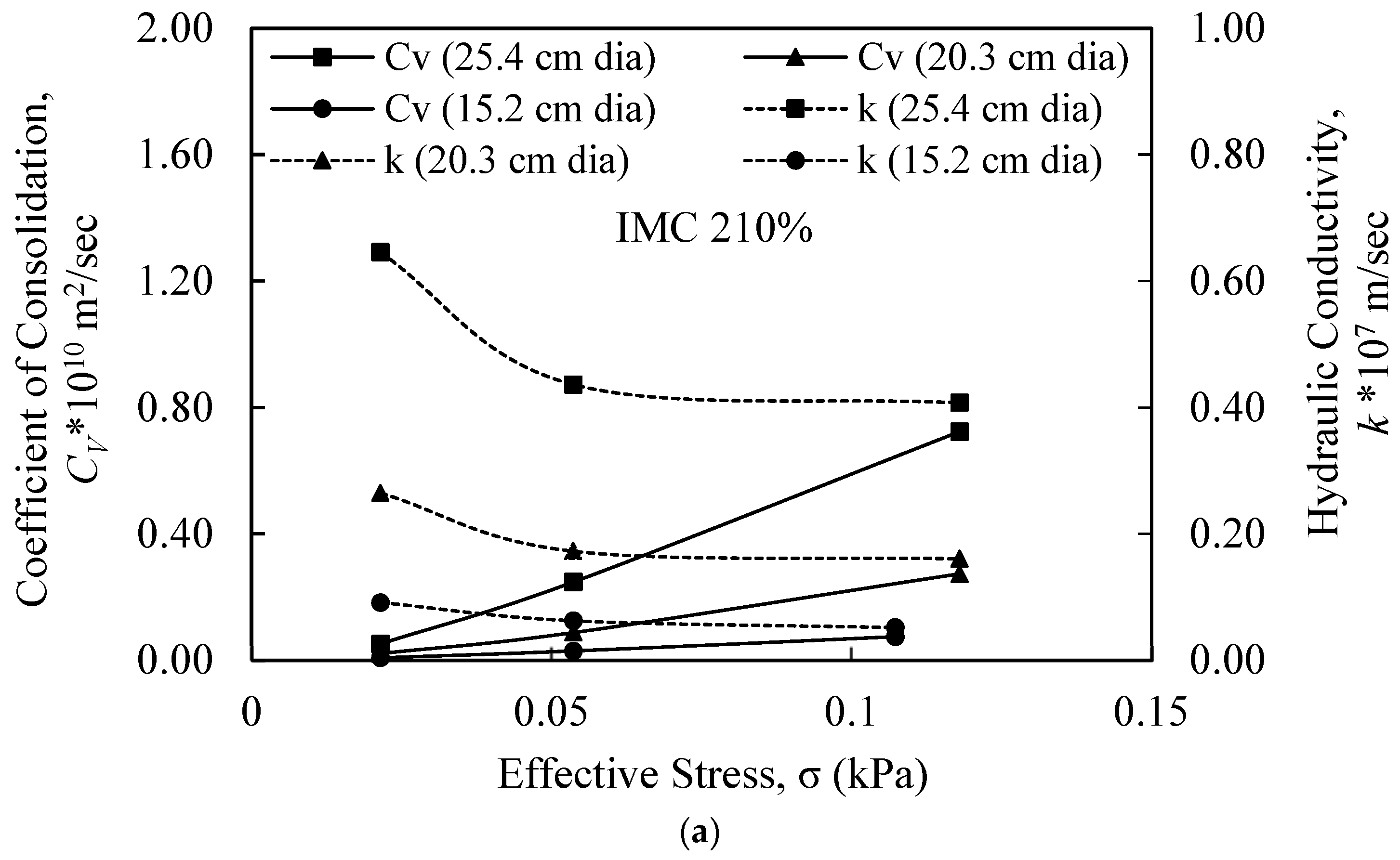

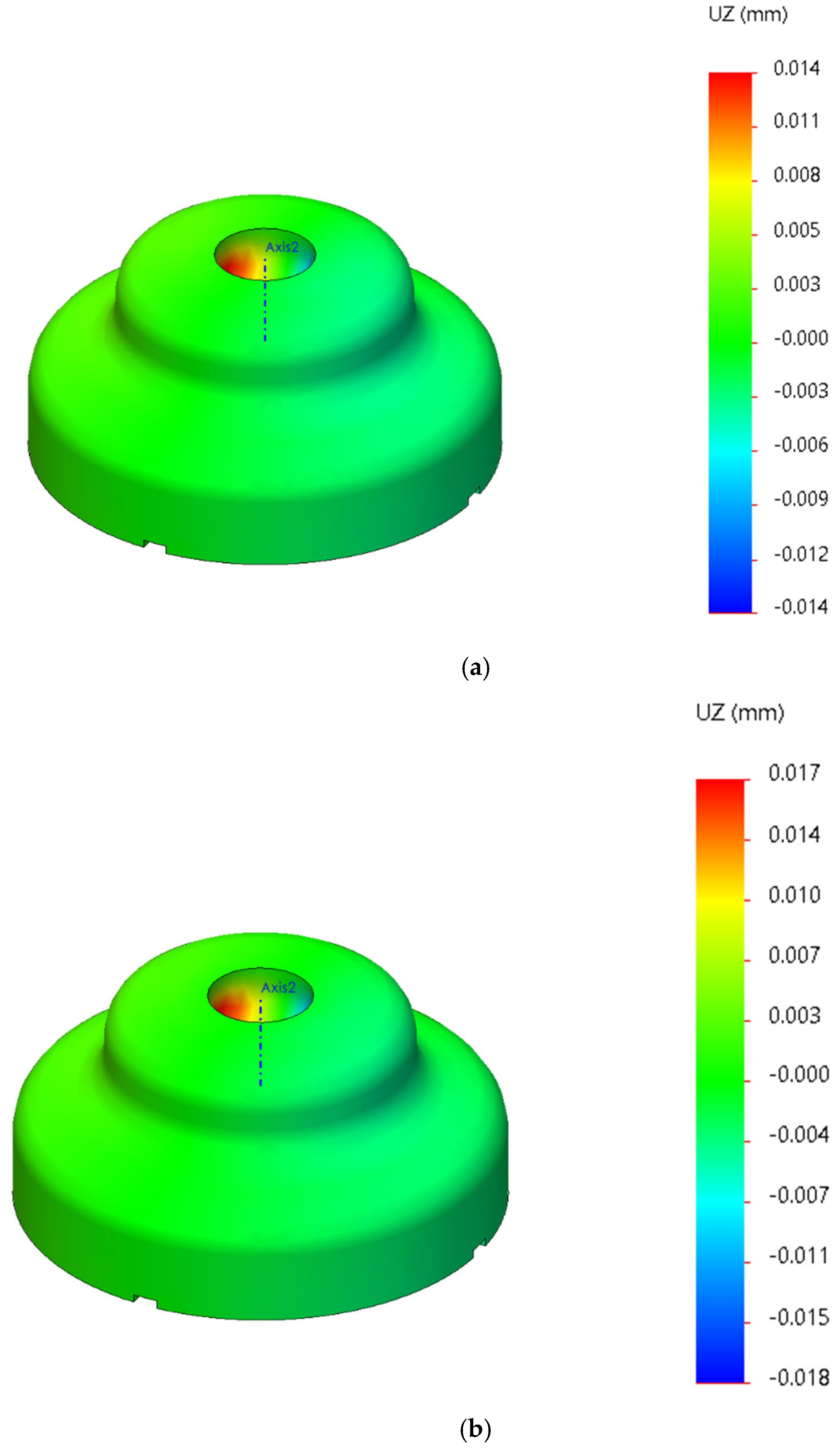

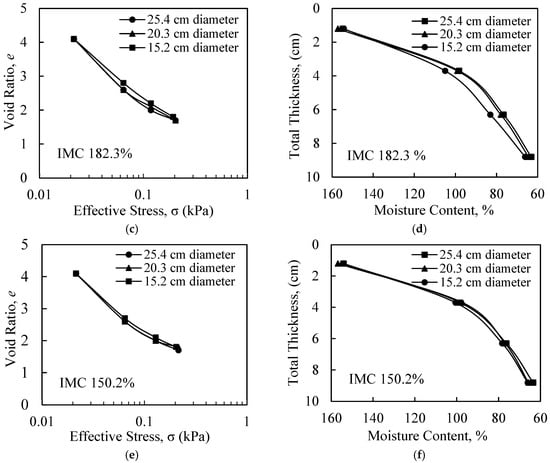

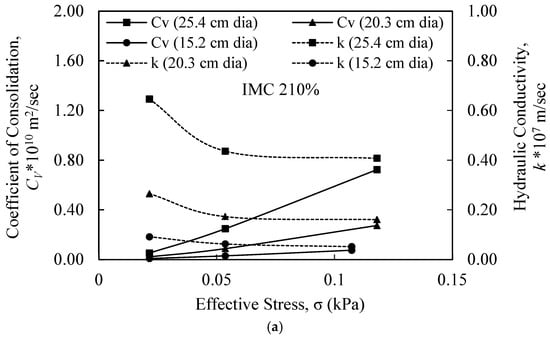

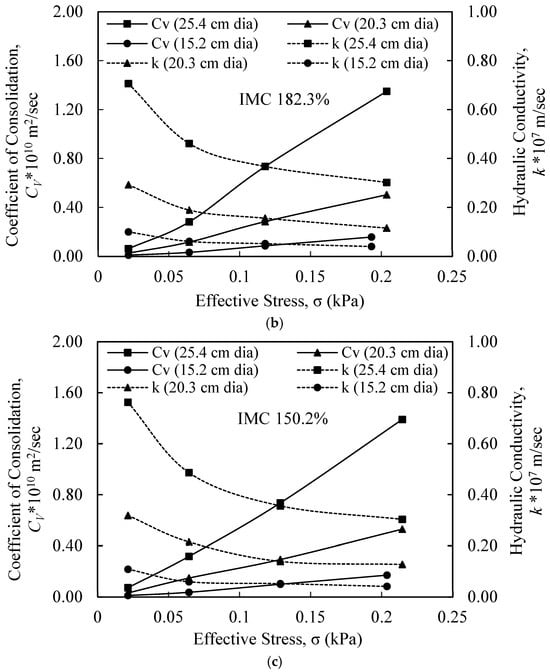

As shown in Figure 8, values of the measured coefficient of consolidation, , from the settling column tests of the dredged soils at the No-Name Bayou Marsh Creation site in coastal Louisiana ranged from 4 × 10−10 m2/s to 1.1 × 10−8 m2/s. Figure 8a–c presents the versus effective stress plots of the three sets of settling column tests. It is identified that increased with the increase in effective stress for all the specimens. Azimi [7] measured the of dredged material obtained from the Savannah River in North Carolina, and it ranged from 9.8 × 10−11 m2/s to 1.1 × 10−10 m2/s, similar to those values presented in this paper. The values for the bentonite-ZVI mixed.

Figure 8.

(a–c) Effective stress vs. coefficient of consolidation, , and hydraulic conductivity, k, of the soil samples for initial water contents of 210.1%, 180.3% and 150.2%, respectively. IMC = initial moisture content of a soil sample.

Slurry sand ranged from 1.9 × 10−6 m2/s to 5.0 × 10−5 m2/s, which were higher than those typically reported for pure clay samples and lower than those typical for pure sand specimens’ samples [33,34].

To determine the hydraulic conductivity (k) from the coefficient of consolidation (), we used the relation , where is the initial void ratio, is the coefficient of compressibility, and is the unit weight of water. The hydraulic conductivity values of the slurry samples from the settling column tests, k, ranged from 9.1 × 10−6 m/s to 1.1 × 10−5 m/s for the slurries made from the dredged soils from the No-Name Bayou Marsh Creation site in coastal Louisiana (Figure 8a–c). The test results showed that the hydraulic conductivities decreased due to the increase in effective stress. The hydraulic conductivity was higher for the test cylinder with larger diameters and gradually decreased with the decrease in cylinder diameter. This indicates that the pore water was decapitated more quickly from the soil matrix in the test cylinders with larger diameters. According to Pane et al. [35], the consolidation duration depends on the soil’s hydraulic conductivity. The higher the hydraulic conductivity, the lower the consolidation duration of time, and vice versa, for the case of lower hydraulic conductivity. Azimi [7] measured the k values of dredged material obtained from the Savannah River in North Carolina, and they ranged from 8.9 × 10−6 m/s to 1.0 × 10−5 m/s. Castelbaum and Shackelford [36] had k values of sand samples mixed with bentonite slurry, which ranged from 2.4 × 10−9 m/s to 6.8 × 10−6 m/s. The k values from Sample and Shackelford [33] for bentonite-ZVI slurry mixed sand specimens ranged from 3.4 × 10−9 m/s to 1.9 × 10−8 m/s. Therefore, the range of k values from the settling column tests presented in this study is similar to the measured values of Azimi [7], falls at the higher end of the range provided by Castelbaum and Shackelford [36], and is almost close to the measured values of Sample and Shackelford [33]. Though the previous studies were on different soil types, the estimated coefficients of consolidation and hydraulic conductivities in this study followed a similar trend.

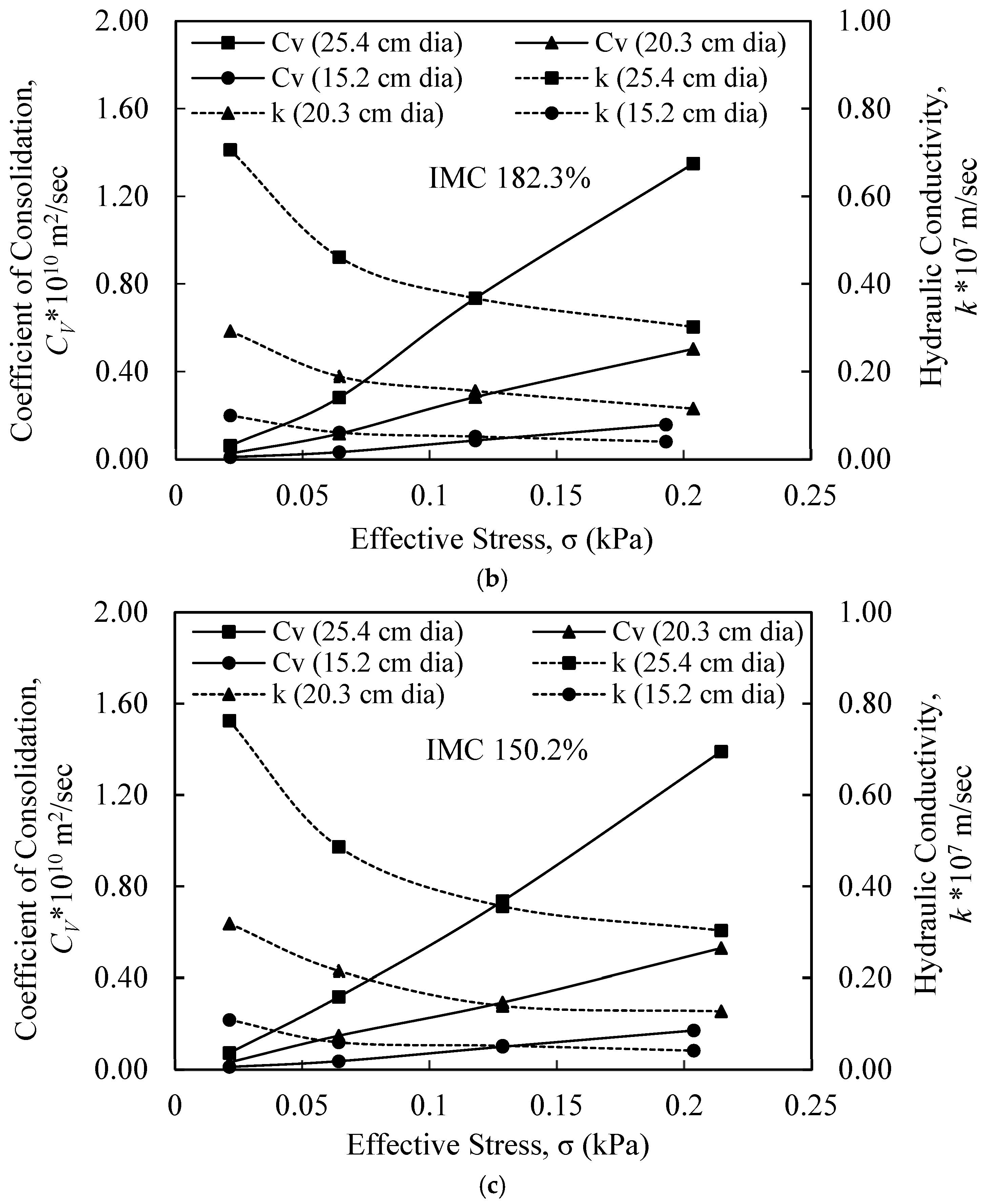

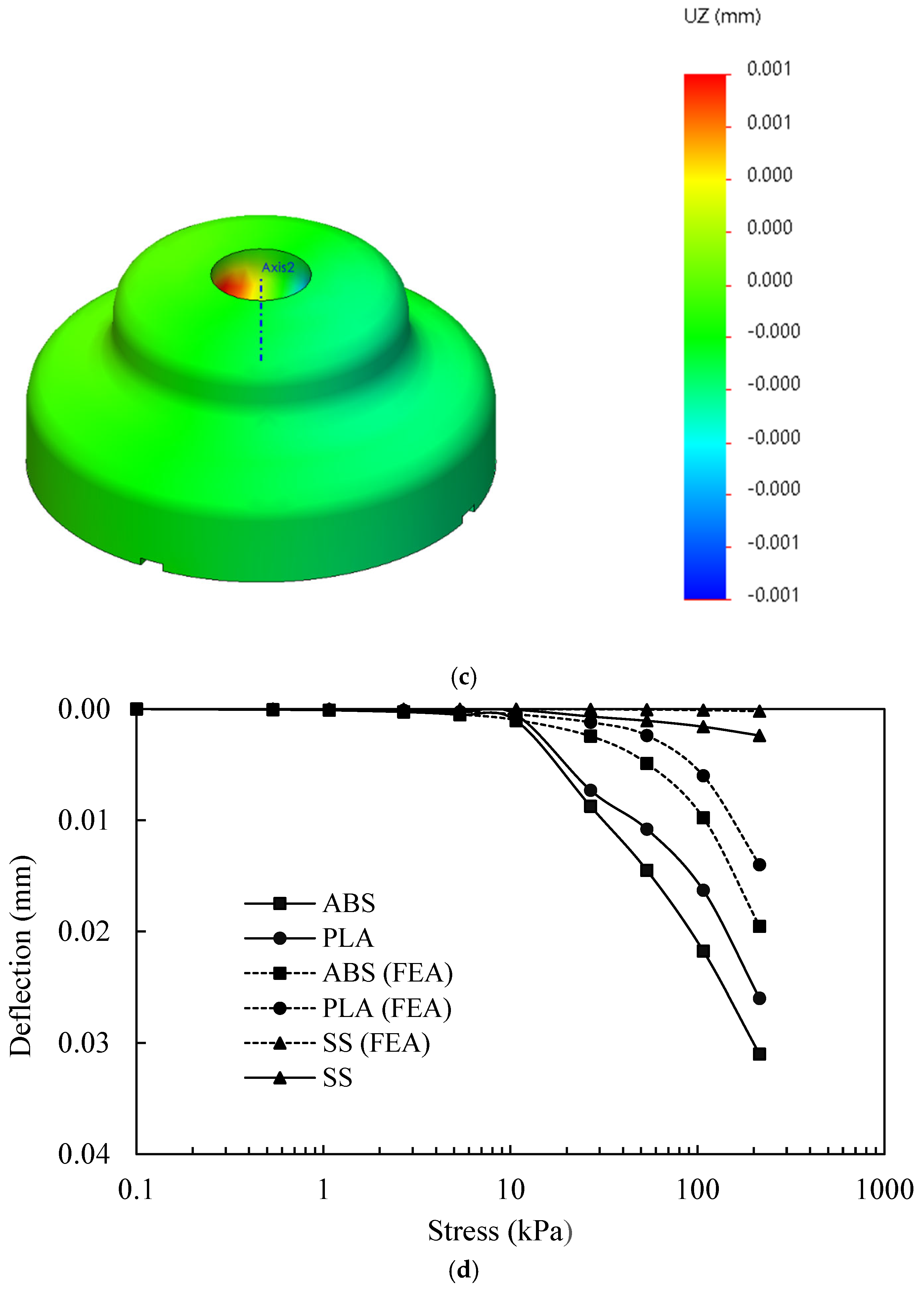

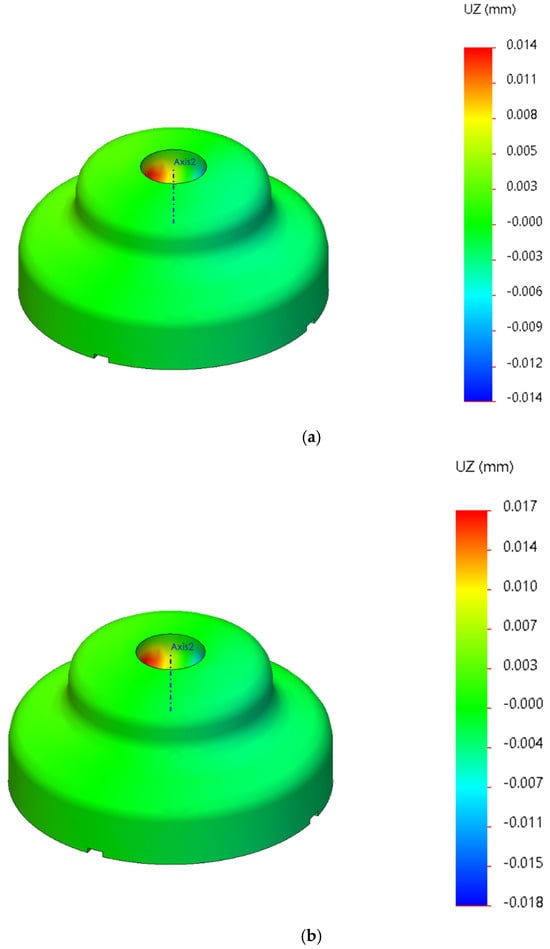

6.3. Deflections of the Dial Caps Themselves

The 3D-printed dial caps are significantly lighter than their stainless-steel counterparts. However, they must remain sufficiently rigid and stiff relative to the soil specimen. Before these 3D-printed caps can reliably replace the stainless-steel ones, their own deformation—particularly the vertical displacement under standard consolidation pressures—must be minimal compared to the consolidation settlement of a one-inch marsh soil sample. In this study, the vertical deformation of the 3D-printed dial caps was investigated both experimentally and numerically. In the experimental program, conventional consolidation pressures were applied to a dial cap using the same loading frame setup. However, the one-inch-thick consolidation soil sample below the dial cap was replaced by a same-size cylindric iron weight. Therefore, during any loading stage, the measured vertical displacements on the top of the dial cap could be reasonably considered the displacements of the dial cap itself. Numerical modeling was performed using the FEM-based commercial software package SolidWorks. The dial cap displacements from the above-mentioned studies were compared with the consolidation displacements measured in the consolidation process, and it was found that the vertical deformation of the 3D-printed dial cap was less than 1% of the consolidation settlements of the slurry sample subjected to a consolidation pressure of 214.50 kPa (2 TSF), measured at the end of a time period of 24 h.

For the 3D-printed dial caps, special alloys called polylactic acid (PLA) and acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) were employed. After applying a load of 214.50 kPa (2 TSF), the vertical displacements of the PLA, ABS and conventional stainless-steel dial caps were measured at 0.026, 0.031 and 0.002 mm, respectively. The numerical results with finite element analyses came up at 0.014 mm, 0.017 mm and 0.001 mm, respectively, using the SOLIDWORKS 2022 software, as shown in Figure 9a–c. The displacement distributions, shown with the same color for the PLA and ABS dial caps in Figure 9a,b, indicated that the 3D-printed dial caps behaved nearly as a rigid body, which was similar to the deformed body of the conventional steel dial cap when they were subjected to a load of 214.50 kPa (2 TSF). The comparisons between the experimental and numerical results of the deflections were presented in Figure 9d. For the slurry consolidation tests, a 24 h consolidation settlement could reach 50% of the original sample depth (25.4 mm) at 1 TSF [9], so the error was less than about 0.2% for each printed dial cap, which is surely acceptable. Based on the information gathered from the literature review, we selected specific mechanical properties for the materials we used in our finite element analyses. For the PLA material, we considered an elastic modulus of 3500 MPa, a yield strength of 70 MPa, and a Poisson’s ratio of 0.36, as reported by Lay et al. [37] and Torres et al. [38]. Similarly, for the ABS material, we adopted an elastic modulus of 1960 MPa, a yield strength of 30.3 MPa, and a Poisson’s ratio of 0.39, which were drawn from research by Cantrell et al. [39] and Saenz et al. [40]. Regarding the default mechanical properties for stainless steel in the SolidWorks software, we utilized an elastic modulus of 193 GPa, a yield strength of 415 MPa, and a Poisson’s ratio of 0.3. Furthermore, the inner diameter of the oedometer dial ring was 63.5 mm, and its height was measured at 25.4 mm.

Figure 9.

(a–c) Finite element analysis of dial caps ((a) PLA, (b) ABS, (c) stainless-steel) using SOLID WORKS software. (d) Stress vs. deflection plots of the dial caps of the oedometer consolidation tests. UZ = deflection in the vertical direction.

6.4. Analyses of Consolidation Data from the Modified Oedometer Tests Using the 3D-Printed Dial Caps

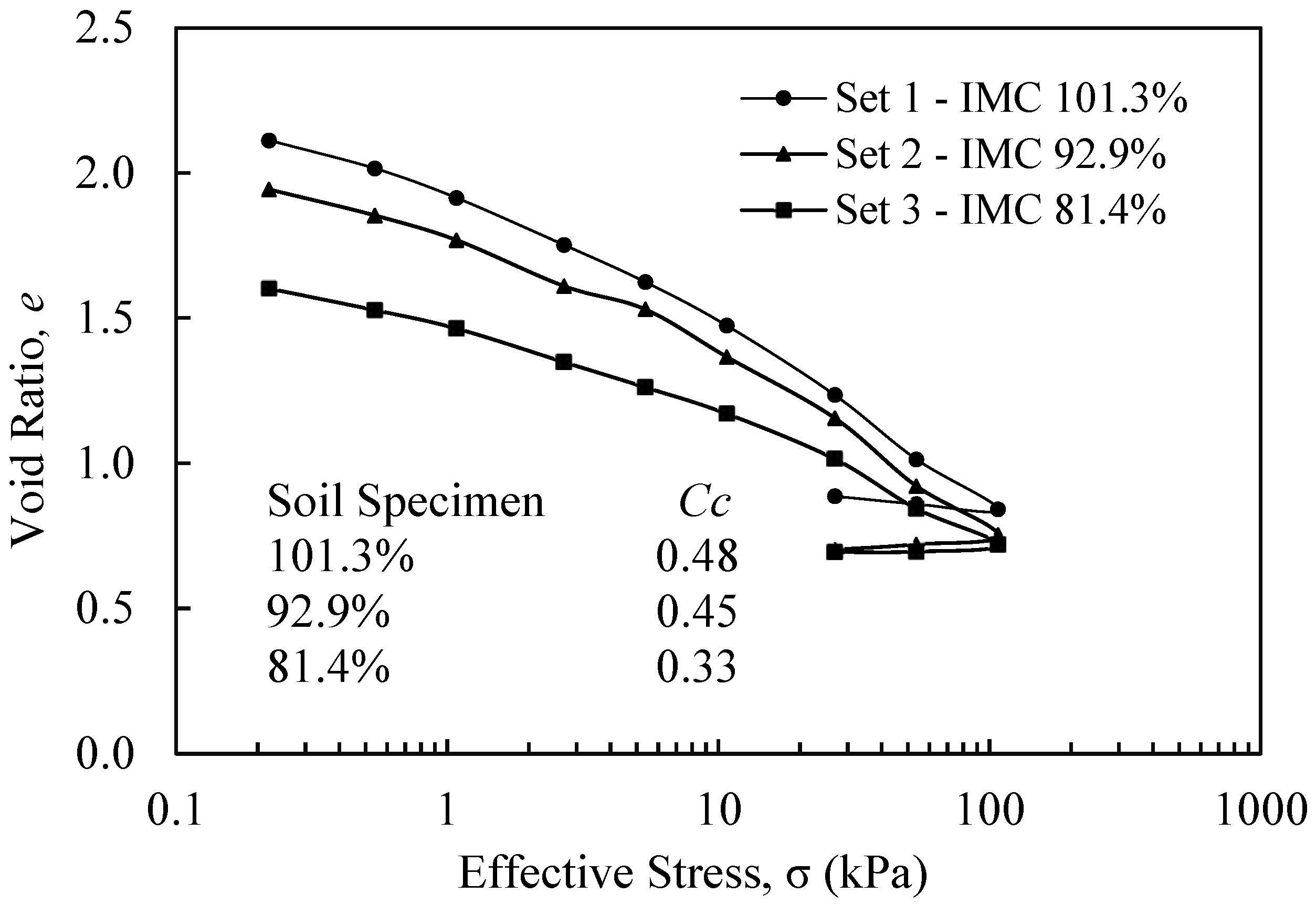

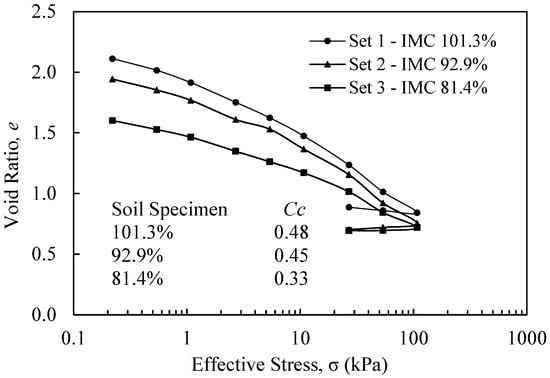

The consolidation properties were determined using Method B of the ASTM 2435 standard [5]. The 3D-printed dial caps, which came up with a seating load of 0.21 kPa (0.002 TSF), including the weight of the porous stone, were utilized successfully to test the soil specimen with a moisture content of 101.3% [9]. Similarly, two other soil specimens with moisture contents of 92.9% and 82.4% were also tested effectively. The resulting void ratio versus effective stress curves from the modified oedometer tests using these 3D-printed dial caps are illustrated in Figure 10 [9]. The curves exhibited similar patterns, and the ultimate void ratios of the three consolidated soil specimens were nearly identical, all falling below 1.0 after applying a load of 107.25 kPa (1 TSF). This load induced significant consolidation deformation, with all tested specimens experiencing vertical strains of approximately 50%, which indicated that a large consolidation deformation happened. According to Apu et al. [41], Sarker et al. [42], Apu & Wang [43], and Apu & Wang [9], the compression index () of Louisiana marsh soils along the coastal line typically ranged from 0.16 to 2.86. The lab experiments on the three soil specimens resulted in compression indices falling within the range from 0.33 to 0.48, as depicted in Figure 10. These values are reasonable and consistent with the established literature.

Figure 10.

Effective stress vs. void ratio curves of the soil samples with moisture contents of 101.30%, 92.90% or 81.40% using the modified oedometer. IMC = initial moisture content of a soil sample.

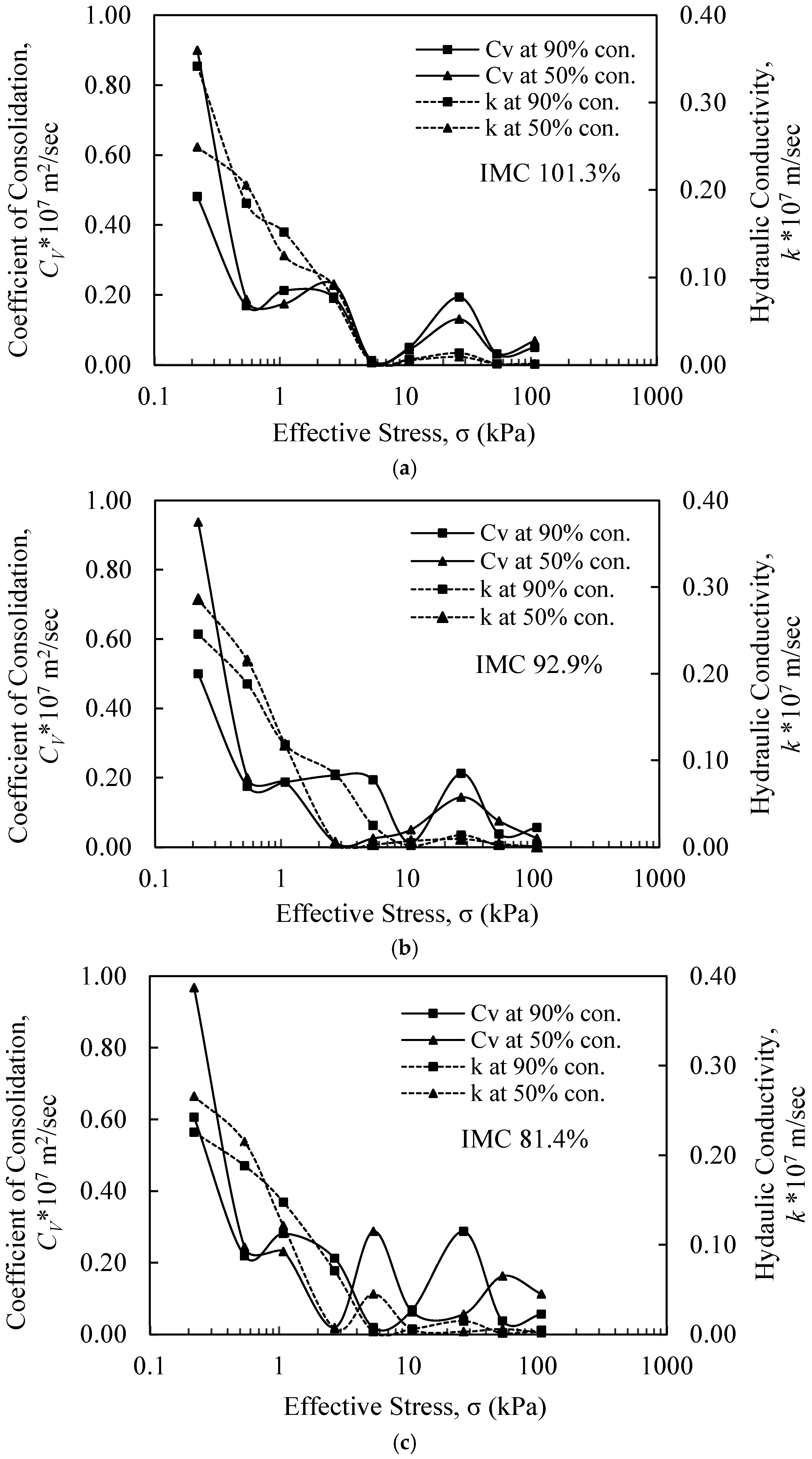

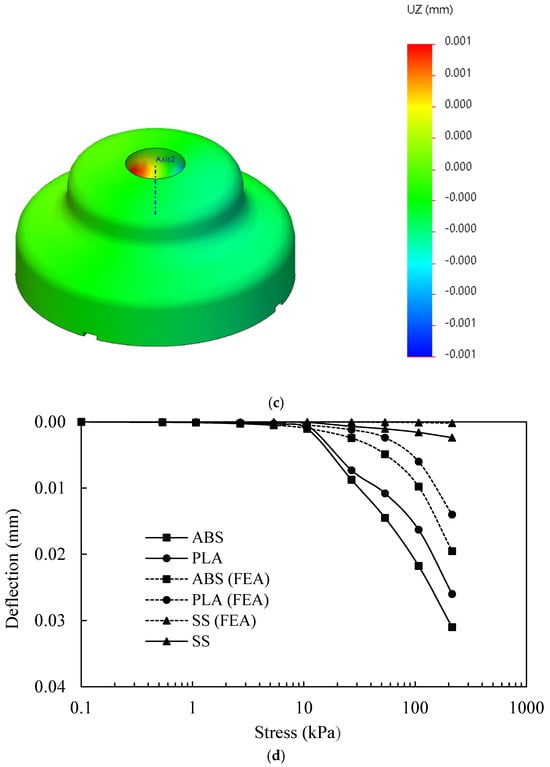

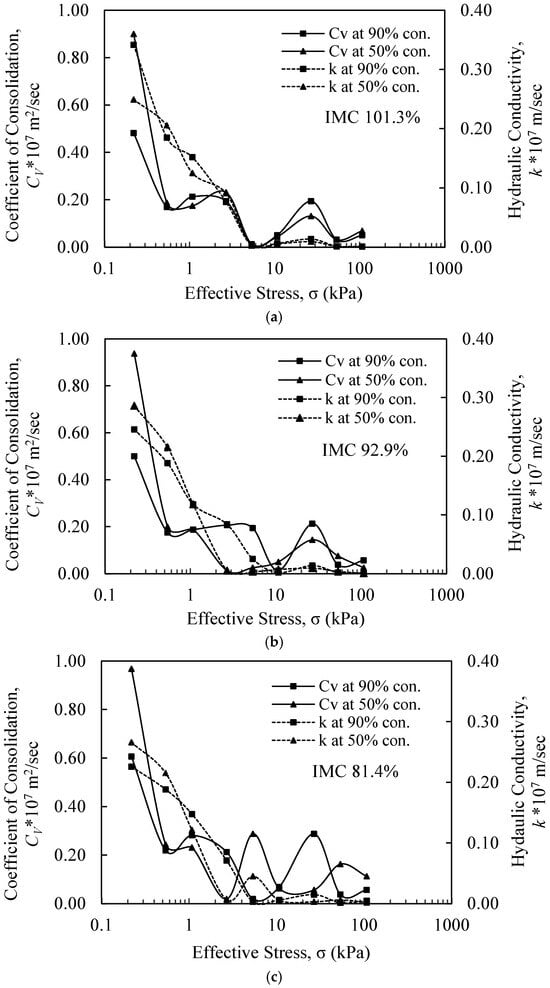

The coefficients of consolidation, , determined through the modified oedometer tests, were displayed in a range between 1.0 × 10−8 m2/s and 9.6 × 10−8 m2/s, as indicated in Figure 11a–c. It is noteworthy that there was an observed decrease in with the increasing effective stress. However, a significant drop in was noted after applying a load of 1.07 kPa (0.01 TSF) [9]. Holtz [44] reported that values of were scattered in the range from 4.0 × 10−9 m2/s to 7.0 × 10−9 m2/s for the clayey soils in Mexico City, which closely resembled the values observed in the dredged soils at the No-Name Bayou Marsh Creation site in coastal Louisiana. On the other hand, for Ottawa sand mixed with 15% silt, values ranged from 4.4 × 10−4 m2/s to 1.2 × 10−3 m2/s when subjected to consolidation in triaxial tests, and from 6.2 × 10−4 m2/s to 2.7 × 10−3 m2/s when consolidated in oedometer tests, as outlined by Carraro et al. [45]. Furthermore, for foundry sand mixed with 15% non-plastic silt, Thevanayagam et al. [46] reported that values spanned from 3.5 × 10−4 m2/s to 1.7 × 10−3 m2/s.

Figure 11.

(a–c) Effective stress vs. coefficient of consolidation and hydraulic conductivity k of the soil samples having moisture contents of 101.3%, 92.9% or 81.4% using the modified oedometer. IMC = initial moisture content of a soil sample.

ASTM D2435 [5] provided a procedure for calculating hydraulic conductivity () based on the results from an oedometer consolidation test. This method encompasses the determination of the void ratio and coefficient of consolidation, and the utilization of the time factor for the degree of consolidation, with the initial and final thicknesses of the soil specimen integrated in the analysis process. In the specific case of the modified oedometer tests conducted for the soil samples taken at the No-Name Bayou Marsh Creation site in coastal Louisiana, it was observed that the hydraulic conductivity of dredged soils decreased significantly after subjecting them to a load of 1.07 kPa (0.01 TSF). The hydraulic conductivity values recorded ranged from 1.1 × 10−9 m/s to 3.5 × 10−8 m/s in Figure 11a–c [9]. Comparatively, Li et al. [47] reported hydraulic conductivity values for highly lean clay in the range between 3.3 × 10−7 m/s and 1.2 × 10−6 m/s, while Moozhikkal et al. [48] found hydraulic conductivity values for Bombay marine clay ranging from 1.0 × 10−10 m/s to 1.9 × 10−8 m/s. These findings are consistent with the hydraulic conductivity values obtained in the present study.

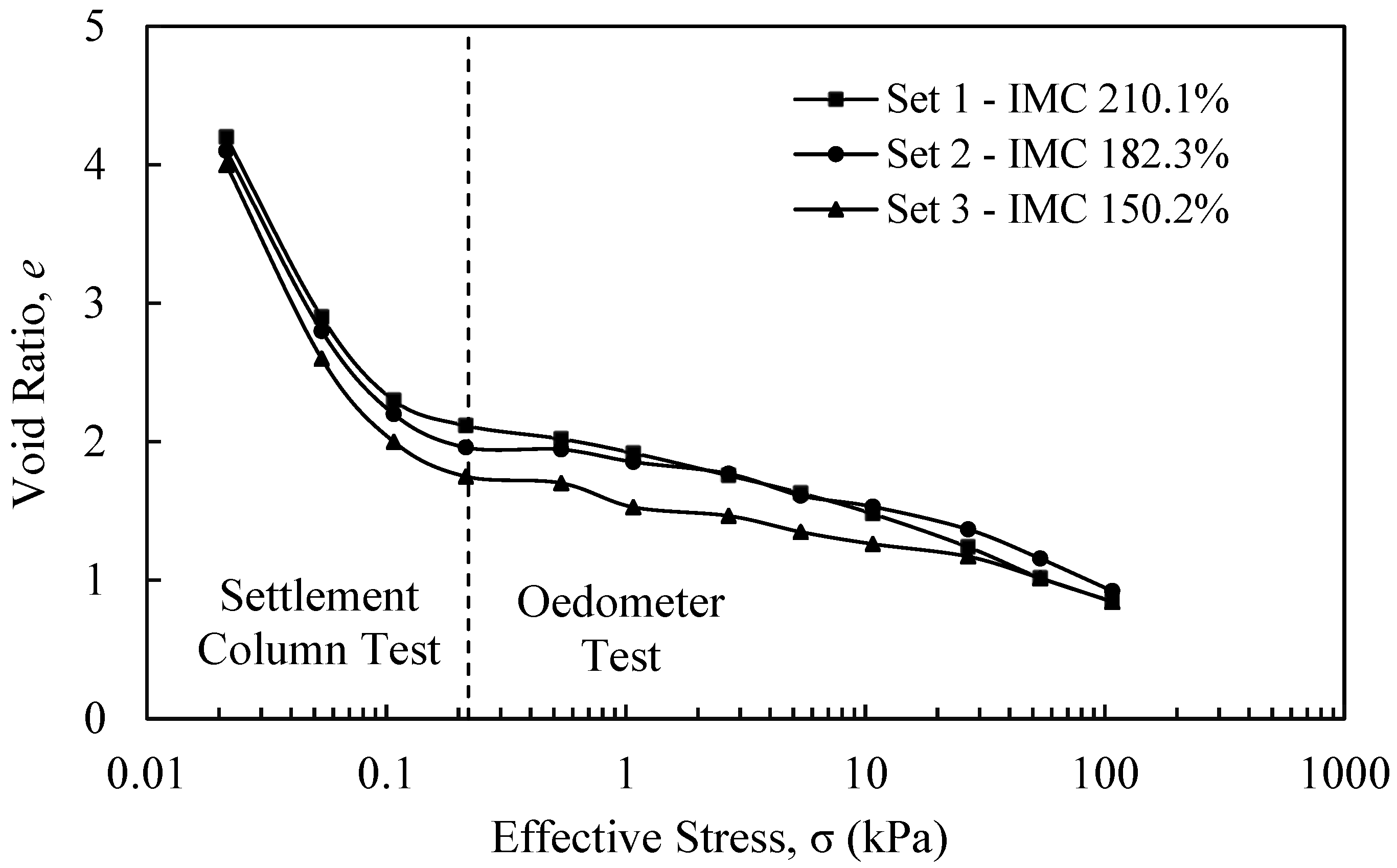

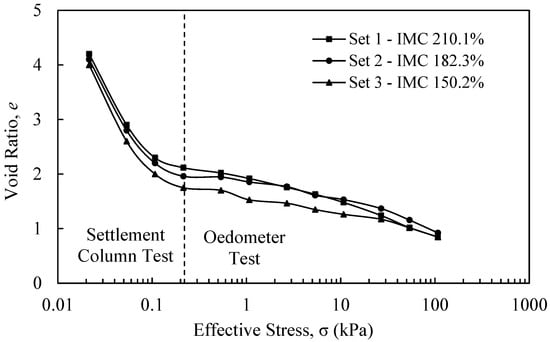

6.5. The Combined Profile of Void Ratio Verses Effective Stress

As mentioned earlier in this paper, the void ratio variations from the settling column tests and modified oedometer tests were combined and plotted against the effective stresses (Figure 12). The void ratios resulting from the three settling column tests at the same effective stresses and the same initial moisture contents were averaged and combined with the test results obtained from the modified oedometer tests. The plotted curves covered effective pressures ranging from 0.02 kPa (0.0002 TSF) to 107.25 kPa (1 TSF). In Figure 12, the three combined void ratio vs. effective stress curves were presented using the laboratory test data and marked as sets 1, 2, and 3. It is clear from the deflection analysis that the 3D-printed dial cap could take a load of 214.50 kPa (2 TSF) without generating a significant deflection. Based on the study, we may draw the conclusion that a 3D-printed dial cap instead of a stainless-steel dial cap could be utilized for the oedometer consolidation tests.

Figure 12.

Effective stress vs. void ratio of the combined settling column and modified oedometer tests. IMC = initial moisture content of a soil sample.

After reviewing the combined void ratio vs. effective stress curves, we observed that the void ratio decreases more quickly in the settling column test portion than in the modified oedometer test portion. This indicates that the consolidation process is highly nonlinear for the dredged soils with high water contents.

7. Concluding Remarks

The use of 3D-printed dial caps for conventional 1-D oedometer tests could significantly reduce the seating pressure from 1.07 kPa (0.01 TSF) to 0.21 kPa (0.002 TSF). And thus the much lighter dial cap could allow 1-D conventional oedometer tests to handle a slurry sample with a water content as high as around 100%. A small-scale settling column self-weight consolidation test and a modified 1-D oedometer test could be combined effectively to conduct consolidation tests for soil slurries with an extremely high moisture content. The procedures presented in this study may provide reliable and tangible consolidation test results for dredged soils from marsh creation projects in coastal Louisiana. The research outcome is very promising for the combination of the modified 1-D conventional oedometer test and small-scale settling column test. By reviewing the settling column test results, it may be recommended that an acrylic plexiglass cylinder with a diameter of six inches or greater could be used for the small-scale settling column test. The wall friction among the three diameter cylinders used in this study is negligible for final settlement. With regard to the hydraulic conductivity and consolidation coefficient in the settling column tests, a cylinder with a greater diameter might give more accurate results. More research needs to be performed before a quantitative recommendation is made. Future research should investigate the long-term durability of 3D-printed dial caps, including the effects of repeated loading, material creep, humidity, and temperature variations. Such studies would further support the long-term applicability of the proposed modified oedometer in routine geotechnical laboratory testing.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by O.S.A. and J.X.W. The first draft of the manuscript was written by the first author, and the second author reviewed, commented on and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research presented in this paper was supported by Louisiana Sea Grant (Grant number: 32-4116-40359).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to David Hall and Kelly Crittenden for their support and assistance in drawing and printing the dial cap. Support and assistance from Jacques Boudreaux and Russ Joffrion are gratefully acknowledged. We are thankful to Ardaman & Associates, Inc. Florida, USA for supplying the dredged soil samples from the No-Name Bayou Swamp production site.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Terzaghi, K. Die theorie der hydrodynamischen Spannungerscheinungen und ihr erdbautechnisches anwendungsgebiet. In Proceedings of the First International Congress for Applied Mechanics, Delft, 1924; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1924; pp. 1–288. [Google Scholar]

- United States Army Corps of Engineers. USACE Laboratory Soils Testing EM 1110-2–1906; United States Army Corps of Engineers: Washington, DC, USA, 1970; Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20231210040931/https://www.publications.usace.army.mil/portals/76/publications/engineermanuals/em_1110-2-1906.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Gibson, R.E.; Schiffman, R.L.; Cargill, K.W. The theory of one-dimensional consolidation of saturated clays. II. Finite nonlinear consolidation of thick homogeneous layers. Geotechnique 1981, 18, 280–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USACE. Confined Disposal of Dredged Material EM 1110-2-5027; Army Corps of Engineers: Washington, DC, USA, 1987; Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20231210041022/https://www.publications.usace.army.mil/Portals/76/Publications/EngineerManuals/EM_1110-2-5027.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- ASTM D2435-04; Standard Test Method for One-Dimensional Consolidation Properties of Soils. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1996. [CrossRef]

- CPRA. Geotechnical Standards Marsh Creation and Coastal Restoration Projects; CPRA: Baton Rouge, LA, USA, 2017; pp. 1–45. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20231210035716/https://coastal.la.gov/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Appendix-B-CPRA-Geotechnical-Standards_12.21.17.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Azimi, A. Laboratory Self-Weight Consolidation Testing of Dredged Material Analyzed Using a One-Dimensional Finite Strain Consolidation Method. Master’s Thesis, Kennesaw State University, Kennesaw, GA, USA, 2018. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20231210013312/https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1001&context=msce_etd (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Wang, J.X.; Omar Shahrear, A. An Interim Report of the Preliminary Consolidation Test Results on Slurry Type Dredged Soils Following the Modified One-Dimensional Oedometer Test; Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority: Baton Rouge, LA, USA, 2021; Available online: https://archive.org/details/interim-consolidation-test-report-jay-wang-la-tech (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- Apu, O.S.; Wang, J.X. A Study of Consolidation Tests on Dredged Soils with a Large Moisture Content in Coastal Louisiana Using a Modified Odometer. In Proceedings of the Geo-Congress 2023; ASCE: Reston, VA, USA, 2023; pp. 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monte, J.L.; Krizek, R.J. One-dimensional mathematical model for large-strain consolidation. Geotechnique 1976, 26, 495–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrier, W.D., III; Keshian, B., Jr. Measurement and prediction of consolidation of dredged material. In Proceedings of the Twelfth Annual Dredging Seminar; Texas A&M University: Houston, TX, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Katagiri, M.; Imai, G. A new in-laboratory method to make homogeneous clayey samples and their mechanical properties. Soils Found. 1994, 34, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, G. Settling behavior of clay suspension. Soils Found. 1980, 20, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridharan, A.; Prakash, K. Self weight consolidation: Compressibility behavior of segregated and homogeneous finegrained sediments. Mar. Georesources Geotechnol. 2003, 21, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuthbertson, A.J.S.; Ibikunle, O.; McCarter, W.J.; Starrs, G. Monitoring and characterisation of sand-mud sedimentation processes. Ocean Dyn. 2016, 66, 867–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- François, B.; Corda, G. Experimental characterization and numerical modeling of the self-weight consolidation of a dredged mud. Geomech. Energy Environ. 2022, 29, 100274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Been, K.; Sills, G.C. Self-weight consolidation of soft soils: An experimental and theoretical study. Geotechnique 1981, 31, 519–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.-F.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Li, D. Effects of column diameter on setting behavior of dredged slurry in sedimentation experiments. Mar. Georesources Geotechnol. 2016, 34, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, R.E.; England, G.L.; Hussey, M.J.L. The theory of one-dimensional consolidation of saturated clays: 1. finite non-linear consildation of thin homogeneous layers. Geotechnique 1967, 17, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cargill, K.W. Consolidation of Soft Layers by Finite Strain Analysis; Miscellaneous paper; Geotechnical Laboratory (US): Columbia, MD, USA; Engineer Research and Development Center (U.S.): Vicksburg, MS, USA; U.S. Army Engineer Waterways Experiment Station: Vicksburg, MS, USA, 1982; Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20231210015703/https://erdc-library.erdc.dren.mil/jspui/bitstream/11681/10139/1/MP-GL-82-3.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Cargill, K.W. Procedures for Prediction of Consolidation in Soft Fine-Grained Dredged Material; Army Engineer Waterways Experiment Station: Vicksburg, MS, USA, 1983; Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20231210020355/https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA125320.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Cargill, K.W. Large Strain, Controlled Rate of Strain (LSCRS) Device for Consolidation Testing of Soft Fine-Grained Soils; Army Engineer Waterways Experiment Station: Vicksburg, MS, USA; Geotechnical Laboratory: Columbia, MD, USA, 1986; Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20231210020659/https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA171591.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Shi, L.; Yin, X.; Sun, H.; Pan, X.; Yuan, Z.; Cai, Y. A new approach for determining compressibility and permeability characteristics of dredged slurries with high water content. Can. Geotech. J. 2022, 59, 965–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; An, Y.; Kwak, T.; Lee, H.; Choi, H. Nonlinear finite-strain self-weight consolidation of dredged material with radial drainage using Carrillo’s formula. J. Waterw. Port Coast. Ocean Eng. 2016, 142, 6016002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaleghi, M.; Karimpour-Fard, M.; Heshmati, A.A.; Machado, S.L. Thermo–Hydro–Mechanical Response of MSW in a Modified Large Oedometer Apparatus. Int. J. Geomech. 2023, 23, 4022310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, A.K. The revised ASTM standard on the unified classification system. Geotech. Test. J. 1984, 7, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D854-02; ASTM Standard Test Methods for Specific Gravity of Soil Solids by Water Pycnometer. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2016. [CrossRef]

- ASTM D4318-17e1; ASTM Standard Test Methods for Liquid Limit, Plastic Limit, and Plasticity Index of Soils. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Azimi, A.; Kaplan, A.; Rad, N.S. A Simplified Self-Weight Consolidation Test Apparatus to Investigate the Consolidation Behavior of Dredged Material at Low Effective Stresses. In Proceedings of the Geo-Congress 2020: Modeling, Geomaterials, and Site Characterization; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2020; pp. 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D2216-10; ASTM Standard Test Methods for Laboratory Determination of Water (Moisture) Content of Soil and Rock by Mass. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Markforged. 3D Printing Process; Markforged: Waltham, MA, USA, 2013; Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20231210035519/https://markforged.com/resources/learn/3d-printing-basics/how-do-3d-printers-work/3d-printing-process (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Gniel, J.; Bouazza, A. Numerical modeling of small-scale geogrid encased sand column tests. In Proceedings of the Second International Workshop on Geotechnics of Soft Soils, Scotland; CRC Press: London, UK, 2008; pp. 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sample, K.M.; Shackelford, C.D. Apparatus for constant rate-of-strain consolidation of slurry mixed soils. Geotech. Test. J. 2012, 35, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. Consolidation with constant rate of deformation. Geotechnique 1981, 31, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pane, V.; Croce, P.; Znidarcic, D.; Ko, H.-Y.; Olsen, H.W.; Schiffman, R. Lo Effects of consolidation on permeability measurements for soft clay. Geotechnique 1983, 33, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelbaum, D.; Shackelford, C.D. Hydraulic conductivity of bentonite slurry mixed sands. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2009, 135, 1941–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lay, M.; Thajudin, N.L.N.; Hamid, Z.A.A.; Rusli, A.; Abdullah, M.K.; Shuib, R.K. Comparison of physical and mechanical properties of PLA, ABS and nylon 6 fabricated using fused deposition modeling and injection molding. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 176, 107341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, J.; Cotelo, J.; Karl, J.; Gordon, A.P. Mechanical property optimization of FDM PLA in shear with multiple objectives. JOM 2015, 67, 1183–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantrell, J.T.; Rohde, S.; Damiani, D.; Gurnani, R.; DiSandro, L.; Anton, J.; Young, A.; Jerez, A.; Steinbach, D.; Kroese, C. Experimental characterization of the mechanical properties of 3D-printed ABS and polycarbonate parts. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2017, 23, 811–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saenz, F.; Otarola, C.; Valladares, K.; Rojas, J. Evolution of Large-Strain One-Dimensional Consolidation Test for Louisiana Marsh Soil. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 39, 101841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apu, O.S.; Wang, J.X.; Sarker, D. Evolution of Large-Strain One-Dimensional Consolidation Test for Louisiana Marsh Soil. In IFCEE 2021: Earth Retention, Ground Improvement, and Seepage Control; ASCE: Reston, VA, USA, 2021; pp. 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, D.; Shahrear Apu, O.; Kumar, N.; Wang, J.X.; Lynam, J.G. Application of sustainable lignin stabilized expansive soils in highway subgrade. In IFCEE 2021: Earth Retention, Ground Improvement, and Seepage Control; ASCE: Reston, VA, USA, 2021; pp. 336–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apu, O.S.; Wang, J.X. Assessment of Compression Index (cc) of Louisiana Marsh Soils by Considering the Sedimentation State. In Proceedings of the Geo-Congress 2022: Geophysical and Earthquake Engineering and Soil Dynamics; ASCE: Reston, VA, USA, 2022; pp. 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtz, R.D. Long-term loading tests at Ska-Edeby, Sweden. In Proceedings of the ASCE Specialty Conference on Earth and Earth Supported Structures; Purdue University: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 1972; pp. 435–464. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20231210034404/http://www.diva-portal.se/smash/get/diva2:1300042/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Carraro, J.A.H.; Bandini, P.; Salgado, R. Liquefaction resistance of clean and nonplastic silty sands based on cone penetration resistance. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2003, 129, 965–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thevanayagam, S.; Martin, G.R.; Shenthan, T.; Liang, J. Post-Liquefaction Pore Pressure Dissipation and Densification in Silty Soils; University of Missouri—Rolla: San Diego, CA, USA, 2001; Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20231210040735/https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1625&context=icrageesd (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Li, L.; Alvarez, I.C.; Aubertin, J.D. Self-weight consolidation of slurried deposition: Tests and interpretation. Int. J. Geotech. Eng. 2013, 7, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moozhikkal, R.; Sridhar, G.; Robinson, R.G. Constant rate of strain consolidation test using conventional fixed ring consolidation cell. Indian Geotech. J. 2019, 49, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.