Abstract

Soil erosion undermines the sustainable development of land—a vital resource for human survival. Research into the spatiotemporal dynamics of soil erosion is therefore crucial for formulating effective soil and water conservation strategies and advancing ecological protection efforts. In the domain of soil erosion research, the Universal Soil Loss Equation and Revised Universal Soil Loss Equation (USLE/RUSLE) model represent the dominant approach for quantifying soil erosion volumes. While this methodology yields reliable outcomes, it fails to incorporate an assessment of the relative significance of the factors embedded within the model. This study selected the Henan section of the Yellow River Basin as the research area, using monthly remote sensing data from 2010 to 2025 as the main data source. Taking into account factors such as rainfall, slope, elevation, vegetation coverage, and hydrological conservation measures, the RUSLE model was used to calculate and combine Geographic Information System (GIS) geographic detectors for quantitative analysis of soil erosion factors. The results showed the following: (1) The average soil erosion modulus in the study area from 2010 to 2025 was mainly micro and mild erosion. (2) Soil erosion exhibits a certain periodicity, with a year of significant soil erosion occurring every 3–4 years. The overall trend of soil erosion is a decrease. (3) Geographic detector analysis shows that slope has the greatest impact on soil erosion, with larger slopes leading to more severe soil erosion. The influence of each factor ranges from large to small as slope > water conservation measures > rainfall > vegetation coverage > elevation. (4) The interaction between factors can enhance the influence on soil erosion, and the interaction between vegetation cover factors and other factors significantly increases the influence; after interacting with various factors, the slope factor will significantly increase the influence of soil erosion. The research results can provide technical support and decision-making basis for ecological protection in the Yellow River Basin, such as through soil and water conservation, returning farmland to forests, and slope greening; The dominant factors and obvious interaction factors in the research area can provide a scientific basis for subsequent scholars to optimize the parameters of regional models.

1. Introduction

Land resources, the fundamental material basis for human subsistence, inherently exhibit temporal and spatial sustainability. However, soil erosion poses a critical threat to the sustainable utilization of land resources. This biophysical process drives soil nutrient loss, amplifies surface runoff, and reduces plant-available water, triggering adverse environmental impacts and progressive soil degradation [1,2]. According to statistics, the global average annual soil erosion modulus is 12–15 t/(hm2·a), which means that there is an approximate soil loss of 0.9~0.95 mm on the surface every year. In the 1970s, scholars began to use soil erosion models for quantitative research on evaluating soil erosion. The earliest model, the Universal Soil Loss Equation (USLE) [3,4,5], is a well-known empirical model for estimating agricultural land surface erosion in the United States. In 1997, Renard and others [6] revised the Universal Soil Loss Equation (USLE) to develop the Revised Universal Soil Loss Equation (RUSLE), through the explicit integration of core soil erosion-driving factors: rainfall erosivity factor (R), soil erodibility factor (K), topographic factor (LS), land cover management factor (C), and support practice factor (P). In contrast to its USLE predecessor, the RUSLE exhibits enhanced predictive capacity for soil erosion across heterogeneous land use types [7]. Bai Yu et al. [8] optimized the algorithm for the support practice factor (P) within the Revised Universal Soil Loss Equation (RUSLE) framework, incorporating the quantifiable regulatory effects of diverse soil and water conservation (SWC) practices and distinct land use categories. By validating this revised P factor, they further confirmed the enhanced RUSLE model’s applicability for soil erosion estimation in the representative mountainous–hilly regions of central China [9]. By combining powerful “3S” technologies (GIS, Remote Sensing (RS), Global Positioning System (GPS)), with soil erosion assessment models, it can quickly evaluate and simulate soil erosion processes and their spatial distribution characteristics in large areas and different time periods under various scenarios [10,11]. Land use change has a regulating effect on the soil in the study area watershed by affecting factors such as vegetation cover, soil characteristics, and runoff velocity, leading to corresponding changes in soil structure, erosion intensity, and mechanisms. Moreover, changes in the spatial-heterogeneity characteristics of land also alter the spatial differentiation patterns of environmental factors such as precipitation, terrain, and soil. Based on the USLE/RUSLE model, ARCGIS is used to visualize the parameters in the model, generating data and intuitive image results for studying the degree of land use change and soil erosion.

In recent years, many scholars have focused on enhancing the applicability of the RUSLE in their research areas. Lynda and others [12] proposed calculating factor C from plant ecological data and applying the improved RUSLE model to the Saharan Atlas pilot area. It was concluded that the accuracy of the soil erosion modulus calculated by vegetation ecological data was better than that calculated by traditional methods. Pei Tian and others [13] improved the calculation method of P by considering the quantitative impact of various soil and water conservation (SWC) measures and land use types. The applicability of the improved RUSLE in estimating soil erosion in typical mountainous and hilly areas in central China was verified by modifying the P factor. Bai Yu and others [8] integrated rainfall distribution and normalized vegetation index, introducing new vegetation coverage and management factors. The results showed that the improved model obtained more effective simulation results. Kebede and others [14] used measured data to determine the synergistic effect of C and P factors, which improved the reliability of the RUSLE in soil erosion prediction.

Drawing on the optimization results of the soil erosion model parameters mentioned above, it is found that, compared to the absolute value of soil erosion loss, the spatiotemporal distribution of soil erosion intensity and the contribution weights of factors and their interactions have more guiding significance. However, the exploration of the coupling degree of multi-factor interactions is still an unsolved problem. Wang [15,16], drawing on spatial differentiation theory, concludes that the geographic detector model has proven effective in identifying drivers of spatial distribution patterns, with successful applications in landscape ecology and environmental pollution research. The Yellow River Basin is China’s most erosion-prone region, and Henan Province holds strategic significance: traversed by the Yellow River, which forms a vast alluvial plain here, it is a core grain production hub in the middle–lower reaches. Soil erosion in Henan directly threatens regional ecological security and national food security, underscoring the need for targeted research. FU [17], Guo Da [18], and other scholars have applied the RUSLE model to the Loess Plateau, confirming its applicability.

Quantitatively exploring the patterns of soil erosion changes in the Henan section of the Yellow River Basin, this research considers various influential elements, including rainfall intensity, terrain slope, altitude variations, vegetation density, and soil and water conservation practices. To achieve this objective, the research adopts geographic detectors as its primary analytical tool, performing a thorough bivariate, interactional quantitative analysis to determine the key natural and human-induced factors that influence soil erosion dynamics within the study area. To achieve this objective, the research incorporates examinations of erosion-inducing mechanisms, spatial–temporal variability patterns, the performance of current regional soil erosion evaluation systems, and soil and water conservation strategies. Such research aims to offer both practical evidence and theoretical foundations for refining region-specific soil erosion forecasting models. In addition, elevating rural residents’ understanding of the dangers posed by soil erosion and the importance of preserving soil and water resources represents a crucial grassroots approach. This serves as an essential and preliminary condition for elevating the efficiency of erosion control initiatives and strengthening the ability of local food security systems to withstand shocks.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Data

2.1.1. Overview of the Research Area

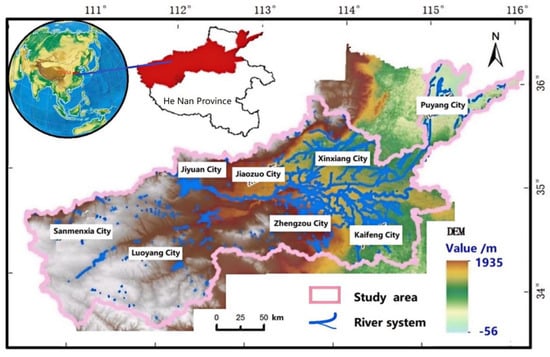

The Henan section of the Yellow River Basin in the research area is located between 34° 23′–36° 22′ north latitude and 111° 12′–116° 39′ east longitude, including 8 cities: Sanmenxia, Jiaozuo, Luoyang, Zhengzhou, Xinxiang, Kaifeng, Puyang, and Jiyuan. The total length of the main river channel in the province is 711 km, and it belongs to the warm-temperate subtropical zone and humid–semi-humid monsoon climate. Summer is hot and rainy, winter is cold and dry, and the monsoon is significant (Figure 1). The terrain in the research area is complex, with high terrain in the west and low terrain in the east. The southwestern region, mainly mountainous areas, is a key area for monitoring soil erosion and water and soil loss.

Figure 1.

Geographical location and terrain of the study area.

2.1.2. Data

The research work relies on multiple types of input data, encompassing categories like pedosphere, atmosphere, land utilization, topographic features, and greenery coverage, as presented in Table 1. Specifically, soil information was retrieved from the National Qinghai Tibet Plateau Science Data Center, utilizing the Chinese soil dataset based on the World Soil Database (HSWD) to compute the soil erodibility factor K [19]. Meanwhile, meteorological data was procured from the National Meteorological Center, which provides a grid-based dataset of monthly ground rainfall values across China covering the period 2010 to 2025. These datasets have been subject to cross-validation and error analysis, ensuring their quality meets acceptable standards. They are employed for computing the rainfall erosivity factor R. Meanwhile, the terrain data, a 30 m resolution ASTER-DEM sourced from the geographic spatial data cloud, serves the purpose of calculating the slope and steep-slope length factor LS. In terms of data sources, the land use information adopts the 300 m resolution land classification map from the European Space Agency, effectively addressing the issues of extended research time spans and subjective visual interpretation methods. For the China region, vegetation coverage information is based on MODIS 500 m monthly NDVI datasets available through geographic spatial data clouds.

Table 1.

Data Source.

Due to significant differences in data resolution, this article uniformly converts data to the WGS1984-Albers coordinate system with a resolution of 30 m when used.

2.2. Methods

RUSLE Model

Developed in 1992 by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research Service (USDA-ARS) as an updated version of the Universal Soil Loss Equation (USLE), the Revised Universal Soil Loss Equation (RUSLE) became available in 1997, offering broader application potential across diverse geographical regions. In the present research, the RUSLE empirical model was selected to assess the soil erosion modulus in the Yellow River section located in Henan Province. To achieve this objective, the mathematical model employed in the research is presented in Equation (1):

In the formula,

A represents the annual average soil erosion modulus (t/hm2·a), which needs to be multiplied by 100 to convert to (t/km2·a);

R represents the rainfall erosivity factor ((MJ·mm)/(km2·h·a));

K represents the soil erodibility factor ((t·km2·h)/(km2·MJ·mm));

LS represents the slope length factor, dimensionless;

C represents the surface vegetation coverage and management factor, dimensionless;

P represents the factor of soil and water conservation measures, dimensionless.

The final unified grid unit for each factor is 30 m × 30 m, and it is standardized to the same projection coordinate system, which was projected onto WGS_1984_ Albers [20].

- Calculation of rainfall erosion factor R

The computation of the rainfall erosion factor R is based on this standardized grid, which maintains a 30 m by 30 m spatial resolution and shares the consistent projection coordinate system aligned with WGS_1984_ Albers.

As a key environmental factor triggering soil erosion, rainfall primarily operates through two main processes: the detachment of soil particles by raindrop impact and the scouring action of overland flow [21]. In order to measure this critical parameter, the rainfall erosivity factor (R) in this research employed a monthly precipitation-based approach, initially developed by Wischmeier et al. [5], which establishes the connection between rainfall intensity and erosion potential using an exponential mathematical relationship. Annual rainfall erosivity was computed by aggregating monthly estimates derived from the i-th month’s precipitation data. The mathematical model, as presented in Equation (2), serves to calculate this annual rainfall erosivity.

In the formula,

pi represents monthly precipitation (mm);

p represents annual precipitation (mm);

i represents the month of erosive rainfall.

- 2.

- Calculation and Mapping of soil erodibility factor K

To assess the soil erodibility factor (K)—a fundamental metric reflecting the natural vulnerability of soil to erosion—this research utilized the Soil Erosion-Productivity Impact Calculator (EPIC) model [3]. As a mechanistic empirical tool commonly used in agricultural ecosystem studies, the EPIC calculates K values by considering two key soil attributes: the proportion of organic matter in the soil and the distribution of particle sizes, which significantly influence the soil’s ability to resist raindrop impact and runoff-induced detachment. To compute the soil erodibility factor (K)—a fundamental indicator reflecting the natural tendency of soil to be eroded—this research utilized the Soil Erosion-Productivity Impact Calculator (EPIC) model [3]. Regarded as a process-oriented empirical tool frequently used in agricultural ecosystem studies, the EPIC calculates K values by relying on two key soil attributes: soil organic matter concentration and grain size composition, both of which significantly influence soil’s ability to resist raindrop impact and runoff-induced detachment.

In the formula,

SAN represents the sand content (%);

SIL is the powder particle content (%);

CLA is the clay content (%);

C is the organic carbon content (%);

SN1 = 1 − SAN/100.

The soil erodibility factor K value is calculated based on the Chinese soil dataset from the Harmonized World Soil Database (HWSD)

- 3.

- Calculation of Slope Length Factor LS

To proceed, the slope length factor LS needs to be computed following a specific methodology. Topography, a basic element in geography, plays a crucial role in soil erosion processes. When determining slope length and gradient factors at the plot level, empirical measurements are typically relied upon, whereas for broader regional assessments, these factors must be derived from digital elevation model (DEM) datasets [21]. The classical empirical formula proposed by Wischmeier et al. [5] was utilized to determine the slope length factor (L). This mathematical model is presented in Equations (4) and (5):

In the formula,

θ and λ represent the slope value (°) and slope length (m) extracted from the DEM;

m represents the slope length index and varies according to the different changes in θ.

This process is calculated using ArcGIS 10.8 Euclidean distance. When constructing river networks, all pixels receiving inflow exceeding 100 units are incorporated into the river network system, while ridge lines undergo Euclidean distance analysis to derive an approximate measurement of slope length. Subsequently, the computed slope length is imported into ArcGIS to perform the calculation of the slope length factor L, followed by data standardization.

The slope factor S is determined by the slope factor calculation method put forward by Zhang Yan and colleagues [22], with the mathematical model presented in Equation (6):

In the formula, θ represents the slope extracted from the DEM and normalizes the calculated slope factor.

- 4.

- Calculation of Surface Vegetation Coverage Coefficient C

The calculation of the Surface Vegetation Coverage Coefficient C involves further processing based on the slope parameter θ, which is derived from the digital elevation model (DEM) and serves to normalize the computed slope factor. To assess the vegetation coverage factor (C), a fundamental indicator reflecting the suppression of soil particle detachment and sediment transport by canopy cover, litter layers, and root systems, this research employed the methodology proposed by Cai Chongfa [23] and Li Tianhong et al. [24]. The mathematical expressions outlining the calculation logic are detailed in Equations (7) and (8):

In the formula,

NDVI is the result of normalizing Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) satellite imagery data;

NDVImax and NDVImin represent the maximum and minimum values of vegetation cover, and c and d are taken as 2 and 1, respectively.

- 5.

- Soil and Water Conservation Measures Factor P

The factor P—representing the efficacy of soil and water conservation measures in mitigating erosion—operates within a 0–1 range that reflects the spectrum of conservation intervention effectiveness. At the lower bound (P = 0), this signifies scenarios where soil erosion is entirely prevented through protective measures. Conversely, a value of 1 indicates unmitigated erosion risk in areas devoid of any soil and water conservation practices.

2.3. Geographic Detector

Geographical detectors (GeoDetector) are specialized statistical tools developed to quantify the spatial variability of geographic elements and uncover the underlying driving factors behind these patterns. Within the theoretical structure of GeoDetector, spatial unevenness is characterized by a situation where the aggregate variance within divided spatial units is less than the total variance of the entire study region, and its intensity is evaluated through the q-index, a metric that ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating more pronounced spatial variation [24,25]. This analytical approach has been widely utilized to pinpoint factors influencing spatial distribution patterns and investigate their interrelated operational mechanisms [26]. A notable strength of GeoDetector lies in its inherent ability to work with categorical explanatory variables, which aligns well with the variable types typically encountered in soil erosion studies [27]. Contrary to conventional regression models, GeoDetector deduces potential causal links between driving forces and the observed phenomenon by analyzing the spatial co-occurrence consistency of multiple variables [28]. It encompasses four specific analytical components with different objectives: the factor component for measuring the explanatory power of individual factors, the risk component for identifying areas with high or low erosion risk, the ecological component for comparing the relative importance of factors, and the interaction component for analyzing the combined effects of multiple factors, whether synergistic or opposing.

Factor detectors are used to examine the impact of independent variables (elements) on the spatial distribution of the dependent variable, with the magnitude of their influence measured by the q-value. Geographic detector Q statistics help clarify spatial confusion, sample bias, and overfitting. The model is shown in Equations (9) and (10):

In the formula,

h = 1, 2, 3, …, L represents the classification or stratification of variable Y or X;

N and Nh are the number of units in the h layer and the entire region, respectively;

represents variances of the Y values in the h layer,

represents the variances of the Y values in the entire region;

SSW is the sum of intra-layer variances, and SST is the total variance of the region.

The q statistic, which ranges strictly from 0 to 1, serves as a measure of how variables contribute to explaining differences in spatial patterns. In this context, q denotes the level of explanatory capability that a specific variable holds for the spatial variations in soil erosion [9]. Within the framework of GeoDetector analysis, a higher q-statistic value implies a more pronounced influence of the relevant factor on the spatial variability of soil erosion within the research area. Therefore, factors that demonstrate statistically significant high q-values are identified as the primary biophysical or human-induced factors governing soil erosion processes within the research region.

Risk detectors are used to assess the risk of soil erosion for different categories by determining whether there is a significant difference in characteristic values between the two levels and calculating the average soil erosion values for each factor in different categories of areas. Ecological sensors introduce statistical differences between several influencing factors. If the factor (consecutive risk name) is significantly greater than Y(X1) in Y(X2), the correlation is represented by “Y”, with N representing the opposite meaning. The interaction sensor uses a quantitative calculation of the interaction between two factors to determine whether the interaction will increase or decrease the explanatory power of the dependent variable (risk of soil erosion). Geographic detectors, which analyze the impact factors of soil erosion through comparing single-factor q values, dual-factor q values, and the interactions among multiple factors, provide a method to assess such influences. This analytical approach demonstrates superior interpretive capability when contrasted with alternative statistical techniques.

By incorporating the biophysical and human-induced factors within the RUSLE framework, this research utilizes geographic detectors to methodically assess the explanatory capacity of variables contributing to soil erosion. The factors selected for analysis include topographic variables (such as slope and elevation, derived from the DEM), hydrometeorological parameters (rainfall erosivity factor, R), vegetation-related factors (vegetation cover factor, C), and human-induced elements (soil and water conservation measures factor, P). For the geographic detector to function effectively, it necessitates the use of data that has been divided into distinct categories; this means continuous variables like elevation and rainfall erosivity must undergo prior processing to be converted into grouped categorical or interval-based classes, which align with the model’s analytical requirements. To meet this need, the discretization of each factor in the dataset is performed using the discretization method put forward by researchers Wang Jinfeng et al. [25] and the prior knowledge proposed by Wang Huan et al. [27]. The slope factor is divided into 6 categories (0°~5°, 5°~8°, 8°~15°, 15°~25°, 25°~35°, >35°); the vegetation coverage factors are divided into 6 categories (<0.15, 0.15–0.21, 0.21–0.25, 0.25–0.35, 0.35–0.45, >0.45); based on the classification of rainfall and erosion level, the erosive factors of rainfall are divided into 6 categories (<12, 12–25, 25–50, 50–100, 100–200, >200), and the factors of water conservation measures are divided into 4 categories (0–0.15, 0.15–0.4, 0.4–0.7, 0.7–1); and DEM elevation is divided into 6 categories (<200, 200–450, 450–700, 700–1000, 1000–1200, >1200). Using the ArcGIS fishing nets function, multiple values were extracted to points, and outliers were removed. A total of 5487 sample points were chosen as the initial dataset for the analysis. In the context of geographic detectors, an analysis is conducted to explore how various elements affect the process of soil erosion.

3. Results

3.1. Calculation Results of Various Parameters

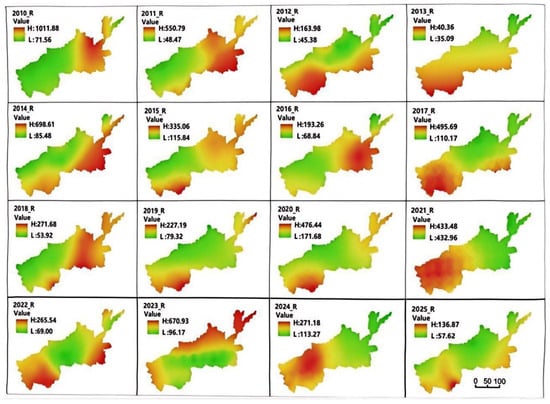

3.1.1. Calculation and Mapping of Erosion Factor Parameter R

The dataset utilized in this research comprises a 0.5° × 0.5° grid-based monthly ground precipitation product for China, which was employed to gather the necessary information. First, the collected data was processed into precise precipitation index data by means of the Python 3.8 programming language, and then the annual rainfall P and rainfall erosivity factor R for each meteorological station were computed. Subsequently, spatial interpolation was performed using ArcGIS 10.8 software to generate spatial data of rainfall erosivity R, and the data was standardized, resulting in a cloud map, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Spatial distribution of rainfall in 2010–2025.

As can be observed from Figure 2, the way rainfall has been distributed over time and space in the research region over the past sixteen years remains indistinct. However, within this overall unclear pattern, distinct regional variations can be observed: the eastern plain region experiences a higher frequency of years with abundant precipitation, whereas the southwestern mountainous area tends to have a lower occurrence of such wet years.

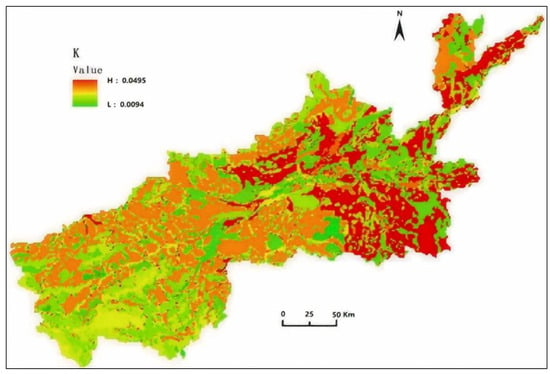

3.1.2. Calculation and Mapping of Soil Erodibility Factor K

Using the previously mentioned computational approach, the K values across the research region could be determined, and a spatial distribution chart of these values was generated based on the Chinese soil information provided by the Harmonized World Soil Database (HWSD). The results as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The spatial distribution map of the soil erodibility K value.

The spatial distribution of the soil erodibility K value indicates that the erodibility of soil is relatively high in the downstream portion of the Yellow River Basin, where there are numerous tributaries with developed river systems. The southeastern mountainous area of the research zone has fewer river tributaries, well-developed forest vegetation, and relatively low soil erosivity values.

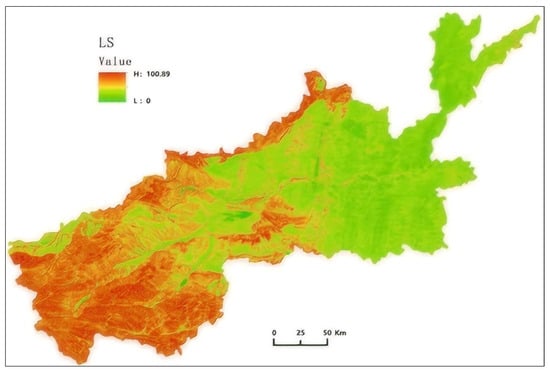

3.1.3. Calculation and Mapping of Slope Length Factor LS

The Slope Length Factor consists of two parameters (i.e., slope S and slope length L), both of which were extracted from various DEMs and then calculated and standardized, using ARCGIS 10.8 software to form the map of LS influencing factors, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Mapping of slope length factor LS.

As shown in Figure 4, the parameter values of LS are relatively high in the mountainous areas of the northern and southwestern parts of the study area, while the values are almost zero in the plain areas of the northeastern parts. Therefore, the sensitivity of this factor is mainly prominent in mountainous areas or areas with steep slopes.

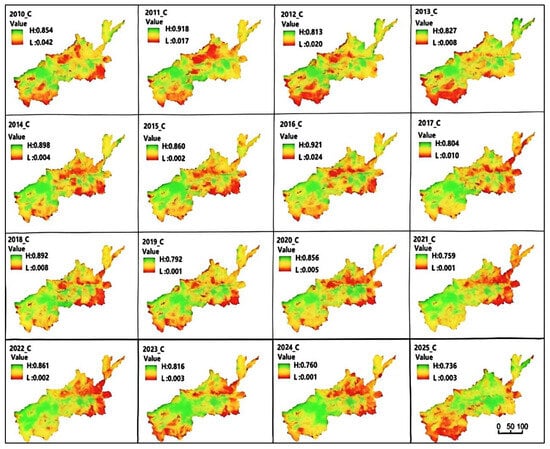

3.1.4. Calculation and Mapping of Surface Vegetation Coverage Coefficient C

The Surface Vegetation Coverage Coefficient (SVCC) typically denotes the ratio of the area covered by vegetation to the total area, and following normalization, its value spans from 0 to 1. This metric primarily serves to indicate how vegetation growth can influence the risk of soil erosion. In other words, the magnitude of this coefficient serves as an indicator of how resistant the soil is to erosion; a lower value implies a higher susceptibility to erosion, while a higher value suggests a greater ability to resist such processes. Based on Equations (4) and (5), after conducting calculations and standardizing the data, a surface index coverage coefficient map for each year was generated. The annual changes in the C parameter are illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Temporal and spatial variations in the SVCC_C over the years.

3.1.5. Geographical Detector Settings

The research utilized 16 annual classification images sourced from the European Space Agency spanning the period 2010 to 2025. These images were categorized into various land cover classes, and each class within the study region was assigned appropriate p-values to facilitate subsequent analytical processes. Referring to the experimental content of You Songcai [29] and Zha Liangsong [30], areas with herbaceous cover, broad-leaved trees, natural vegetation, trees, shrubs, inlaid herbs, and grasslands are generally considered not to have adopted water conservation measures, so they are assigned a value of 1; rivers and cities generally do not experience soil erosion and are assigned a value of 0; areas with farmland irrigation and vegetation coverage < 15% are assigned a value of 0.15; the assigned value for arid land is 0.4; the farmland vegetation is assigned a value of 0.7 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Common p-values for different land use types.

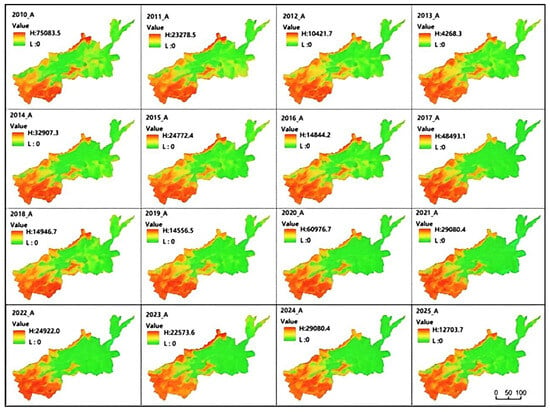

3.2. Characteristics of Spatiotemporal Distribution of Soil Erosion

We obtained the soil erosion modulus from 2010 to 2025 using the RUSLE model. Then, we calculated the annual average soil erosion modulus of the study area from 2010 to 2025. According to China’s Soil Erosion Classification and Grading Standards (SL190-2007 [31]) (Table 3), the soil erosion in the study area is mainly micro erosion and mild erosion.

Table 3.

Soil Erosion Grading Standards.

Analysis of the spatiotemporal distribution of soil erosion shows that during the 16-year period, as shown in Figure 6. Soil erosion in the study area was mainly concentrated in areas with high slopes and elevations. The soil erosion levels in Sanmenxia City, Luoyang City, and Zhengzhou City were significantly higher than those in Jiaozuo City, Jiyuan City, Xinxiang City, Kaifeng City, and Puyang City; the soil erosion levels in Puyang City, Xinxiang City, and Kaifeng City were significantly lower than those in Jiaozuo City, Jiyuan City, Sanmenxia City, Luoyang City, and Zhengzhou City. The southwestern mountainous area and northwestern part of the research area had the highest soil erosion level and the strongest erosion, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 6.

Spatial distribution map of soil erosion in research area for each year.

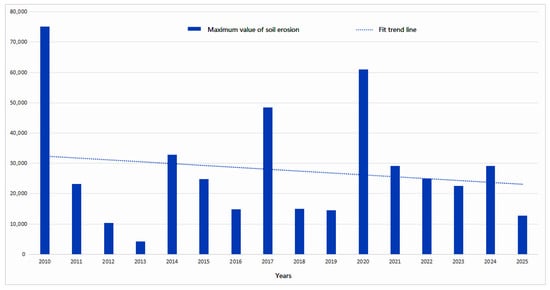

Figure 7.

Data-driven analysis of maximum values and trends of soil erosion.

According to the statistical chart analysis, the range of the soil erosion modulus in 2010 (the maximum value is 75,093.50 (t/(km2·a))) was significantly higher than in other years; the range of soil erosion modulus in 2013 (the maximum value is 4268.28 (t/(km2·a))), was significantly lower than other years. This result is strongly correlated with the rainfall erosion factors in 2010 and 2013. The maximum value of soil erosion shows a certain cycle, which is 3–4 years (for example, 2010–2013, 2014–2016, 1017–2019, 2020–2023, and 2022–2025). Every 3–4 years, there will be a significant increase in soil erosion. The overall trend of the maximum value of soil erosion is decreasing, which is directly related to China’s soil and water conservation policies and investment in this area.

4. Discussion

Soil erosion, a geomorphological process, is inherently governed by the interplay of various environmental factors, with their influences differing significantly across different spatial scales. Understanding how erosion-controlling factors differ regionally and identifying the key drivers influencing local erosion patterns are essential foundations for developing tailored soil and water conservation strategies, as this approach ensures solutions are based on site-specific biophysical characteristics rather than one-size-fits-all approaches. Factor detector analysis reveals that, across gradient tiers, each candidate erosion driver shows statistically significant variations in corresponding erosion intensity, with the explanatory power magnitude of soil erosion modulus—measured by q-statistics—differing significantly among various drivers. Aligning with the national standard Soil Erosion Classification and Gradation Standards, slope gradient thresholds delineate three erosion intensity classes: slight erosion occurs on slopes with inclinations <15°, mild erosion dominates slopes between 15° and 35°, and moderate erosion is prevalent on slopes exceeding 35° (Table 4). These findings may offer a scientific foundation for implementing slope protection strategies, including terraced fields and stone embankments.

Table 4.

Erosion modulus corresponding to slope.

Vegetation coverage can reduce soil exposure to natural forces and alleviate soil erosion. The impact of vegetation cover on soil erosion is not only reflected in providing a protective layer for plant residues and input of organic matter, but also in regulating and maintaining soil moisture. When vegetation coverage is less than 0.35, soil erosion reaches its peak. The vegetation coverage factor corresponds to soil erosion levels of micro erosion at each level (Table 5), so maintaining greenery can effectively reduce soil erosion.

Table 5.

Erosion modulus corresponding to vegetation coverage factors.

The intensity, duration, and spatial distribution of rainfall directly affect its erosive power. The erosive power of rainwater is also related to the natural and man-made environment. With a small slope, high vegetation coverage, and good soil and water conservation engineering, the erosion of soil by rainwater is minimal. The annual average soil erosion modulus increases continuously with the increase in precipitation factor level and elevation level. Rainfall levels 1–4 belong to minor erosion, while levels 5–6 belong to mild erosion. Overall, the erosion level is not high (Table 6).

Table 6.

Erosion modulus corresponding to rainfall factors.

Elevation is one of the key topographic factors that affect soil erosion, mainly indirectly driving erosion processes by controlling precipitation distribution, runoff processes, vegetation growth, and soil characteristics. When the elevation is greater than 450 m, the annual average soil erosion modulus increases rapidly, corresponding to micro erosion; when the elevation is greater than 1000 m, the annual average soil erosion modulus tends to flatten, corresponding to mild erosion (Table 7). Planting trees on slopes can enhance water retention and effectively reduce soil erosion.

Table 7.

Erosion modulus corresponding to elevation factors.

The change in land use type has a significant impact on soil erosion levels, and soil erosion basically does not occur when water and soil conservation measures are between 0 and 0.15; when the water conservation measures are between 0.7 and 1, the annual average soil erosion modulus reaches its maximum (Table 8). The results indicate that returning farmland to forests and protecting vegetation play an important role in soil erosion.

Table 8.

Corresponding erosion modulus of water conservation measures factor.

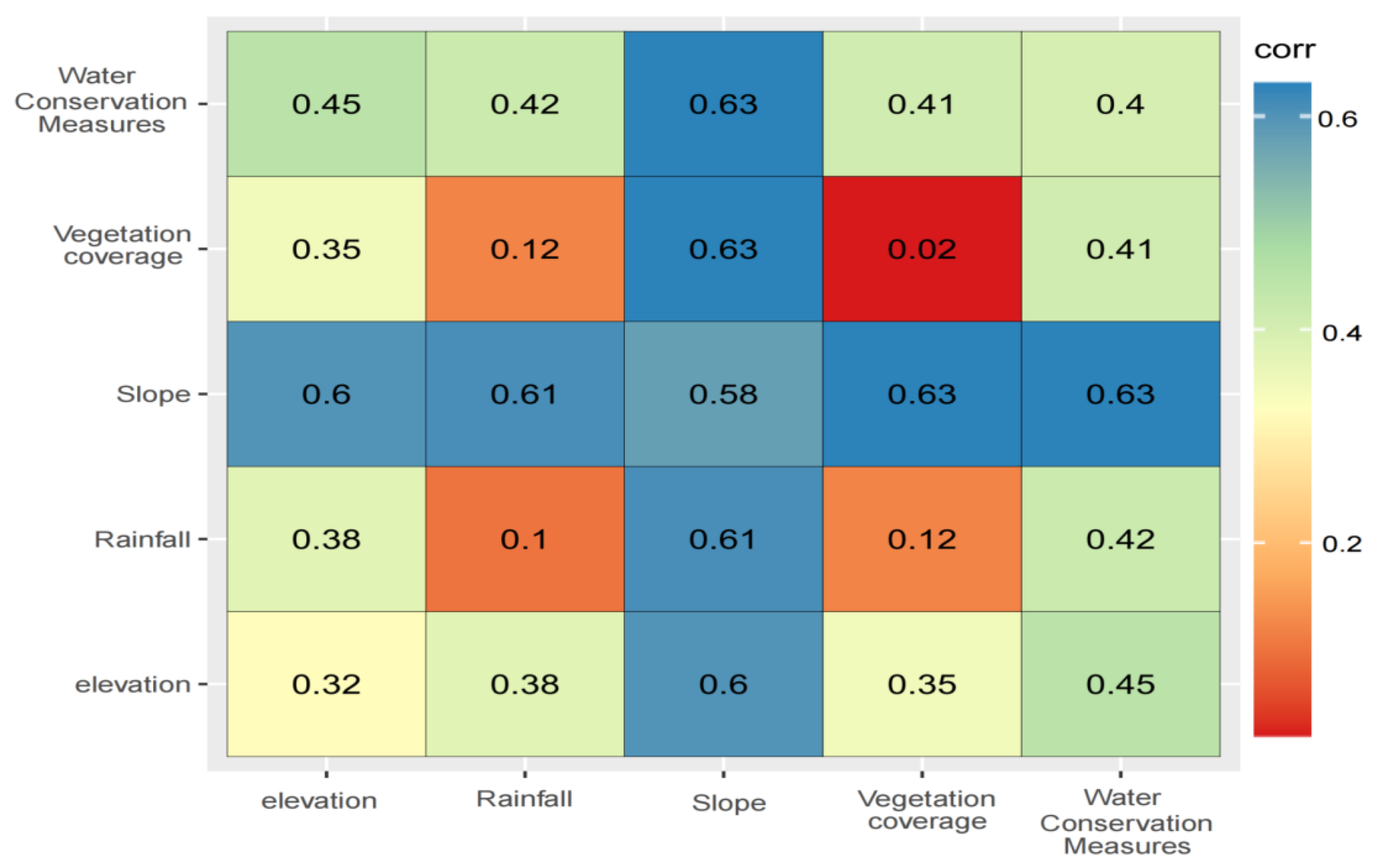

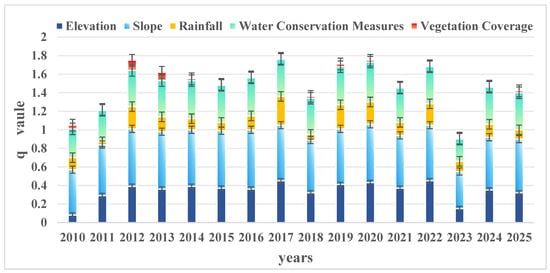

The operation results of the geographic detector indicate that different influencing factors have significant differences in the explanatory power of the soil erosion modulus. Overall, the influencing factors are slope > water conservation measures > rainfall > vegetation coverage > elevation. The elevation influence factor in 2010 was relatively small compared to other years; the precipitation influence factors in 2017 were significantly higher than those in other years; the slope had the highest q value between 2010 and 2025, indicating that slope is the dominant factor determining the spatial pattern of soil erosion in the study area (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Corresponding q values for different factors.

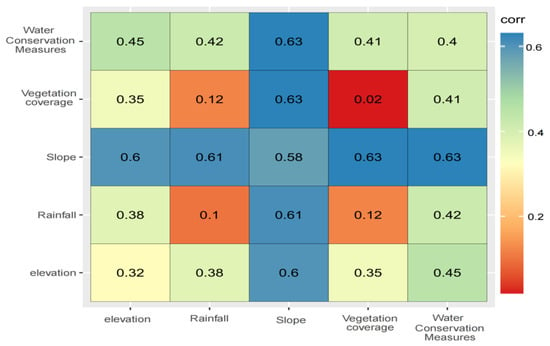

The interaction detector represents the explanatory power of the synergistic effect of two factors on soil erosion. Taking soil erosion in 2025 as an example, the interaction statistics show that the synergistic effect of any two factors will enhance the influence on soil erosion. Slope remains the dominant factor in soil erosion in the study area. Comparing the q values of the interaction between various factors and vegetation cover factors with the q values of a single vegetation cover factor, the q values showed a significant enhancement. The q value after interaction indicates that in areas with significant differences in vegetation coverage, soil erosion has significant differences. Therefore, measures such as maintaining greenery, planting trees on slopes, building stone embankments, and protecting terraced fields can effectively reduce soil erosion. Further research is needed to consider the impact of measured soil data on soil erosion and optimize vegetation management factors.

Interpretation of the geographic detector results depicted in Figure 9 indicates that the slope factor exhibits the highest q-statistic value (~0.6), representing the strongest explanatory power for soil erosion spatial heterogeneity in the study area, surpassing all other evaluated drivers. The soil and water conservation practices factor (P) ranks second in significance. Correspondingly, targeted soil erosion mitigation strategies should prioritize slope gradient optimization, implementation of evidence-based conservation measures, and deployment of slope stabilization engineering structures. Additionally, the elevation, rainfall erosivity (R), and vegetation cover (C) factors demonstrate comparable explanatory power, with q-statistic values ranging from 0.3 to 0.4.

Figure 9.

Statistical analysis of interactive q-values of soil erosion factors.

In summary, soil erosion is inevitable, and we should take active measures to reduce soil erosion and protect our land. For the natural factor of rainfall, we are unable to take effective measures for intervention. We can construct soil and water conservation projects such as terraced fields based on elevation and slope factors. To increase the vegetation coverage of poor-quality land with steep slopes, we can adopt methods such as returning farmland to forests and grasslands. We can increase the organic matter and moisture content of the soil through measures such as Yellow River irrigation and the application of farmyard manure.

5. Conclusions

In this study, the Revised Universal Soil Loss Equation (RUSLE) was employed to model the spatial distribution patterns of soil erosion across the study area. Complementarily, geographic detector analysis was conducted to quantify the individual explanatory power of soil erosion drivers and their interactive effects on erosion dynamics. The key findings are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- For the period 2010–2025, the mean soil erosion modulus across the study area was calculated as 852.82 t/(km2·a). Erosion intensity was dominated by the micro and mild classes, with severe erosion hotspots primarily concentrated in the northern and southwestern portions of the study domain. Spatially, soil erosion modulus values were significantly lower in Puyang, Kaifeng, Xinxiang, Jiaozuo, and Jiyuan compared to those observed in Zhengzhou, Luoyang, and Sanmenxia.

- (2)

- The slope factor consistently served as the dominant driver of soil erosion throughout the 2010–2025 period. Statistical analysis revealed that the soil erosion modulus peaked when the vegetation cover factor (C) fell below 0.35. Rainfall erosivity (R), elevation, and slope exhibited similar monotonic relationships with erosion: higher values of these factors corresponded to an increased soil erosion modulus. Regarding the soil and water conservation practices factor (P), erosion intensity reached its maximum when P = 1 (representing no conservation measures), while negligible erosion occurred when P was within the 0–0.14 range.

- (3)

- Soil erosion across the study area exhibited distinct periodic dynamics, with an overall decreasing trend over the study period. This temporal trend is closely linked to the implementation of national soil and water conservation policies and targeted investment in ecological restoration within the region.

- (4)

- Geographic detector interaction analysis revealed that the vegetation cover factor (C) exhibited significant synergistic effects with other drivers, amplifying their combined explanatory power for soil erosion. Similarly, the slope factor demonstrated enhanced erosion-driving capacity when interacting with other factors. These findings imply that ecological restoration measures such as converting cropland to forest and slope greening can effectively mitigate soil erosion by leveraging these synergistic interactions. The identified strong interactive effects among vegetation cover, slope, and other key drivers offer empirical support for model optimization efforts in future soil erosion research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.X. and G.L.; methodology, Z.X. and G.L.; software, Z.X. and G.L.; validation, Z.X. and G.L.; formal analysis, X.W.; investigation, X.W.; resources, J.L.; data curation, J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.X. and G.L.; writing—review and editing, Z.X., X.W., J.L., and G.L.; visualization, Z.X. and G.L.; supervision, Z.X. and G.L.; project administration, Z.X. and G.L.; funding acquisition, Z.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by funding from the Shaanxi Railway Institute Foundation: Design and Application of Online Monitoring System for Mine Spoil Dump (KY2019-07).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from online resources and this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HWSD | World Soil Database |

| EPIC | Erosion-Productivity Impact Calculator, |

| SWC | Soil and Water Conservation |

| USLE | Universal Soil Loss Equation |

| RUSLE | Revised Universal Soil Loss Equation |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| RS | Remote Sensing |

| 3S | GPS, RS, GIS |

| SVCC | Surface Vegetation Coverage Coefficient |

References

- Ganasri, B.; Ramesh, H. Assessment of soil erosion by RUSLE model using remote sensing and GIS-A case study of Nethravathi Basin. Geosci. Front. 2016, 7, 953–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaee, S.; Ghorbani-Dashtaki, S.; Mohammadi, J. Spatial variability of soil organic matter using remote sensing data. Catena 2016, 145, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanyaş, H.; Kolat, Ç.; Süzen, M.L. A new approach to estimate cover-management factor of RUSLE and validation of RUSLE model in the watershed of Kartalkaya Dam. J. Hydrol. 2015, 528, 584–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.C.; Zhao, S.M.; Wang, R.B. Soil erosion risk study in Shanxi Province based on GIS and CSLE. Soil. Water Conserv. Res. 2016, 23, 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Wischmeyer, W.; Smith, D.D. Predicting Rainfall Erosion Losses—A Guide to Conservation Planning; USDA Agriculture Handbook; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Djillo, S.C.; Wolka, K.; Tofu, D.A. Assessing soil erosion and farmers’ decision of reducing erosion for sustainable soil and water conservation in Burji woreda, southern Ethisopia. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merritt, W.S.; Letcher, R.A.; Jakeman, A.J. A review of erosion and sediment transport models. Environ. Model. Softw. 2003, 18, 761–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Cui, H. An improved vegetation cover and management factor for RUSLE model in prediction of soil erosion. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 21132–21144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, E.; Xiao, Y.; Ouyang, Z. National assessment of soil erosion and its spatial patterns in China. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2015, 1, 11878987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullan, D. Soil erosion under the impacts of future climate change: Assessing the statistical significance of future changes and the potential on-site off-site problems. Catena 2013, 109, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, H.S.; Jiang, C. Soil erosion patterns and quantitative attribution in southwest China based on RULSE and geodetector models. J. Appl. Basic. Eng. Sci. 2021, 144, 109496. [Google Scholar]

- Lynda, B.-O.; Sylvain, O.; Aziz, H. Contribution of phytoecological data to spatialize soil erosion: Application of the RUSLE model in the Algerian atlas. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2021, 9, 502–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, P.; Zhu, Z.; Yue, Q. Soil erosion assessment by RUSLE with improved P factor and its validation: Case study on mountainous and hilly areas of Hubei Province, China. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2021, 9, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, B.; Tsunekawa, A.; Haregeweyn, N. Determining C-and P-factors of RUSLE for different land uses and management practices across agro-ecologies: Case studies from the Upper Blue Nile basin, Ethiopia. Phys. Geogr. 2021, 42, 160–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.F.; Li, X.-H.; Christakos, G. Geographical detectors-based health risk assessment and its application in the neural tube defects study of the Heshun Region, China. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2010, 24, 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Water Resources Website. Ministry of Water Resources issues National Soil and Water Erosion Dynamic Monitoring Plan (2018–2022) and National Soil and Water Conservation Supervision Plan (2018–2020). Gansu Water Conservancy and Hydropower Technology. February 2018. Available online: http://www.swcc.org.cn/uploads/soft/181220/1-1Q220150113.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2026).

- Fu, B.; Zhao, W.; Chen, L. Assessment of soil erosion at large watershed scale using RUSLE and GIS: A case study in the Loess Plateau of China. Land Degrad. Dev. 2005, 16, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Song, X.N.; Dong, X. A study on the evaluation of soil erosion on the Loess Plateau based on RUSLE and GIS—Taking the Zhongwei area of Ningxia as an example. Sediment Res. 2020, 45, 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Oak Ridge National Laboratory DAAC (ORNL DAAC). Regridded Harmonized World Soil Database v1.2. Data Set. 2020. Available online: https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/data/catalog/ornl-cloud-hwsd-1247-1 (accessed on 25 May 2020).

- Yi, K.; Wang, S.Y.; Wang, X. Spatial and temporal variation of soil erosion based on RUSLE model: The case of Chaoyang City, Liaoning Province. Geoscience 2015, 35, 365–372. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.X.; Yang, X.H.; Xiao, L.L. Study on soil erosion in southern hilly mountains based on RUSLE model. Resour. Sci. 2014, 36, 1288–1297. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, X.; Li, Q.; Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; Wu, F. A New Method to Estimate the Cover Management Factor on the Loess Plateau in China. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2025, 39, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.F.; Ding, S.W. Application of USLE model and GIS IDRISI for predicting soil erosion in small watersheds. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2000, 14, 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.H.; Zheng, L.N. Soil erosion dynamics in the Yanhe River Basin from 2001 to 2010 based on RUSLE model. J. Nat. Resour. 2012, 27, 1164–1175. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.F.; Xu, C.D. Geodetectors: Principles and Perspectives. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2017, 72, 116–134. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.M.; Lu, D.D.; Xu, C.D. The spatial heterogeneity of the population on both sides of the Hu Huanyong Line and its variations. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2017, 72, 148–160. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Nan, J.B.; Hou, W.J. Quantitative attribution of soil erosion in different geomorphological types of karst based on geographic probes. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2018, 73, 1674–1686. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.X.; Jiang, Y.J.; Zhang, Y.Z. Spatial distribution and drivers of stone desertification in karst troughs and valleys by GIS and geodetectors. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2019, 74, 1025–1039. [Google Scholar]

- You, S.C.; Li, W.Q. Soil erosion estimation with GIS support: An example from Gouxi Township, Taihe County, Jiangxi Province. J. Nat. Resour. 1999, 1, 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Cha, L.S.; Deng, G.H.; Gu, J.C. Soil erosion dynamics in the Chaohu Lake basin from 1992 to 2013. J. Geogr. 2015, 70, 45–57. [Google Scholar]

- SL190-2007; Soil Erosion Classification and Grading Standard. Ministry of Water Resources of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2008. Available online: https://slgcfy.ylvtc.cn/__local/D/6F/D7/6C04DCAF303494B02D6DBB6E965_8A1D4E97_BC696.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2026).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.