Abstract

Grounded in the dynamic capabilities framework, this study examines how entrepreneurship and technological innovation jointly shape business performance and how sustainable management conditions these effects across its economic, social, and environmental dimensions. Using survey data from 300 firms across multiple industries, we find that entrepreneurship significantly enhances both non-financial and financial performance, and that technological innovation serves as a key mediating mechanism through which entrepreneurship translates into performance outcomes. The results reveal differentiated moderating effects of sustainable management. While the economic dimension of sustainable management shows a limited moderating influence, the social and environmental dimensions significantly amplify the returns to entrepreneurship and technological innovation. By disentangling sustainable management into distinct dimensions, this study moves beyond prior research and demonstrates that sustainability functions as a contextual capability that asymmetrically conditions the returns to entrepreneurship and innovation. The findings offer actionable insights for managers and policymakers seeking to align entrepreneurial initiatives and innovation strategies with social legitimacy and environmental stewardship to achieve sustained value creation.

1. Introduction

Sustainable development has emerged as a defining imperative for contemporary organizations as business environments are increasingly shaped by regulatory pressures, stakeholder scrutiny, and the rapid expansion of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG)–oriented investment frameworks. In alignment with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), firms are no longer evaluated solely on financial outcomes but are expected to generate long-term value while responsibly managing social and environmental impacts [1,2,3,4,5]. As a result, sustainability has moved from a peripheral concern to a central strategic consideration across industries.

Despite this shift, firms continue to face a fundamental strategic challenge: how can entrepreneurial initiatives and innovation activities be effectively translated into superior performance outcomes under ESG-intensive conditions? Prior research has consistently demonstrated that entrepreneurship and technological innovation are critical drivers of firm performance [6,7]. However, much of this literature treats sustainability either as an outcome variable or as a homogeneous contextual factor. Such approaches implicitly assume that sustainability uniformly enhances firm performance, thereby overlooking the possibility that different sustainability dimensions may condition entrepreneurial and innovative efforts in distinct ways.

There exist unmet needs in uncovering when and how sustainable management in differing dimensions influences the performance returns to entrepreneurship and technological innovation. Recent research increasingly suggests that sustainability practices are embedded within organizational routines, governance structures, and stakeholder relationships that may interact with firms’ strategic capabilities [8,9]. From this perspective, sustainability, operationalized here as sustainable management, is not merely an external constraint or reputational concern but a contextual force that shapes how firms deploy entrepreneurial and innovative capabilities. However, empirical evidence remains fragmented, particularly with respect to whether economic, social, and environmental sustainable management exerts symmetric or asymmetric effects on performance outcomes. Addressing this gap is critical for both theory development and managerial practice, especially in environments where ESG expectations are institutionalized.

To address these issues, this study adopts a dynamic capabilities perspective to examine the joint effects of entrepreneurship and technological innovation on business performance and the moderating role of sustainable management across its economic, social, and environmental dimensions. Dynamic capabilities theory provides a robust analytical framework for understanding how firms adapt, renew, and reconfigure resources in response to rapidly changing environments [10,11,12]. Defined as the firm’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competences, dynamic capabilities emphasize not only resource possession but also the effectiveness of capability deployment through sensing, seizing, and transforming routines [13,14,15,16].

Within this framework, entrepreneurship represents a firm’s sensing capability and the initiation of seizing behavior, enabling the identification of new opportunities under uncertainty. Technological innovation operationalizes the seizing and transforming functions by converting identified opportunities into new products, processes, and business models. Sustainable management, in turn, can be understood as a set of institutionalized organizational routines that shape the context in which these capabilities are deployed. By influencing legitimacy, stakeholder alignment, risk exposure, and resource efficiency, sustainable management practices may condition how effectively entrepreneurship and innovation translate into performance outcomes.

Building on the insight, the present study explicitly distinguishes between financial and non-financial performance outcomes. Prior research indicates that sustainability-oriented practices frequently exert differential effects across performance domains, particularly when social legitimacy and environmental efficiency precede financial appropriation [17,18,19]. Aggregating financial and non-financial indicators risks masking these dynamics and may lead to inconsistent or attenuated findings. By analyzing these outcomes separately, this study provides a more precise examination of how specific sustainable management dimensions condition the entrepreneurship–innovation–performance relationship.

Accordingly, this research addresses the following questions. First, how do entrepreneurship and technological innovation jointly influence financial and non-financial performance? Next, does technological innovation mediate the relationship between entrepreneurship and performance outcomes? Finally, how do economic, social, and environmental dimensions of sustainable management differentially moderate these relationships?

In addressing these questions, this study makes three primary contributions. First, it reconceptualizes entrepreneurship as a dynamic capability that not only directly enhances performance but also facilitates the transformation of sustainability challenges into strategic opportunities through technological innovation. Second, it advances sustainability research by empirically demonstrating that ESG dimensions are not functionally equivalent; rather, social and environmental sustainable management exert asymmetric conditioning effects on entrepreneurial and innovative returns, while economic sustainable management operates primarily as a baseline governance mechanism. Third, by modeling sustainable management as a contextual capability that moderates both direct and indirect performance pathways, this study extends dynamic capabilities theory into the ESG domain and clarifies how organizational routines shape capability deployment under sustainability-intensive conditions.

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. Dynamic Capabilities as a Theoretical Lens

Dynamic capabilities theory provides a well-established framework for explaining how firms achieve and sustain performance advantages under conditions of environmental uncertainty and change. Unlike the resource-based view, which emphasizes the possession of valuable and rare resources, the dynamic capabilities perspective focuses on how firms interpret environmental change and renew organizational capabilities over time in response to shifting technological, market, and institutional environments [13,14,15,16].

At the core of this perspective are the sensing, seizing, and transforming processes through which organizations identify opportunities, mobilize resources, and reconfigure operational routines [16,17,18,19]. A substantial body of research has applied this framework to examine how strategic orientations and innovation activities contribute to firm performance, particularly in volatile and innovation-intensive contexts. As such, dynamic capabilities have become a dominant lens for studying the entrepreneurship–innovation–performance nexus.

Within the literature, entrepreneurship and technological innovation are consistently identified as central organizational activities through which dynamic capabilities are expressed. Entrepreneurship captures firms’ proactive engagement in opportunity recognition and strategic initiation under uncertainty, while technological innovation represents the execution of opportunity exploitation through new products, processes, and business models [20,21,22,23]. Empirical studies grounded in the dynamic capabilities framework demonstrate that these activities are critical drivers of both financial and non-financial performance.

More recent studies further emphasize that the effectiveness of dynamic capabilities is context-dependent. Capabilities do not automatically translate into performance; rather, their value depends on organizational routines, governance structures, and institutional conditions that shape how entrepreneurial and innovative activities are enacted and evaluated [12,19]. In this regard, sustainable management practices—encompassing economic, social, and environmental dimensions—can be understood as institutionalized organizational activities that structure and condition capability deployment.

Despite growing interest in sustainability and ESG-oriented management, prior studies often treat sustainability either as a direct antecedent of performance or as a homogeneous construct. Such approaches may overlook the possibility that different sustainable management dimensions condition entrepreneurial and innovative activities in asymmetric ways. A dynamic capabilities lens is therefore particularly suitable for examining sustainability not as a performance outcome per se, but as a contextual mechanism that governs the translation of entrepreneurship and technological innovation into performance.

Building on this theoretical foundation, the following sections develop hypotheses regarding the direct effects of entrepreneurship and technological innovation on firm performance, the mediating role of technological innovation, and the differential moderating roles of economic, social, and environmental sustainable management dimensions.

2.2. Entrepreneurship and Business Performance

Building on the theoretical lens outlined above, entrepreneurship is conceptualized in this study as a strategic activity through which firms proactively identify opportunities and initiate adaptive responses under uncertainty. An entrepreneurial top management team (TMT) creates organizational conditions conducive to performance improvement. Commitment to innovation, persistence in the face of risk, open communication, and receptivity to external knowledge facilitate opportunity recognition, strategic alignment, and coordinated action [20,21]. Through these activities, entrepreneurship accelerates decision-making processes, enhances cross-functional collaboration, and strengthens firms’ responsiveness to environmental change.

Extensive empirical research supports a positive relationship between entrepreneurship and business performance. Meta-analyses and longitudinal studies consistently show that entrepreneurship is associated with superior firm outcomes across industries and institutional contexts [22,23]. These effects are observed across both financial and non-financial performance dimensions. Entrepreneurial activities contribute not only to profitability and growth, but also to market share expansion, innovation output, customer satisfaction, and employee engagement—outcomes that often precede and enable long-term financial success [24,25,26].

From the dynamic capabilities standpoint, these findings suggest that entrepreneurship enhances performance by enabling firms to continuously align strategic intent with changing environmental conditions [27]. Given the multidimensional nature of performance—particularly in sustainability-intensive environments—it is theoretically appropriate to distinguish between financial and non-financial outcomes when examining the effects of entrepreneurial activity. Accordingly, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1a.

Entrepreneurship positively influences non-financial performance.

H1b.

Entrepreneurship positively influences financial performance.

2.3. Technological Innovation and Business Performance

Technological innovation refers to firms’ ability to develop and implement new or significantly improved products and processes. According to the Oslo Manual, technological innovation encompasses both product and process innovation that enhance efficiency, quality, and market competitiveness [28]. A substantial body of research has shown that such innovations play a central role in driving firm growth and long-term performance by enabling differentiation, productivity gains, and market expansion [29,30].

In the dynamic capabilities perspective, technological innovation represents a key performance-generating activity through which identified opportunities are translated into tangible outcomes [31]. While entrepreneurship initiates strategic intent and opportunity recognition, technological innovation operationalizes opportunity exploitation by converting ideas into commercially viable outputs. Through product innovation, firms introduce novel offerings and access new markets, while process innovation improves operational efficiency, cost structures, and quality consistency [32,33].

Innovation activities are inherently knowledge-intensive and rely on continuous learning, experimentation, and recombination of existing capabilities. Firms with strong technological innovation capabilities are better positioned to respond to environmental volatility and evolving customer demands [34,35]. Empirical evidence supports these arguments, demonstrating that new product advantages, launch proficiency, advanced manufacturing technologies, lead-time reduction, quality improvement, and cost efficiency are all positively associated with both financial and non-financial performance outcomes [36].

To summarize, these findings suggest that technological innovation constitutes a critical pathway through which firms realize performance gains. Accordingly, we propose the following hypotheses:

H2a.

Technological innovation positively influences non-financial performance.

H2b.

Technological innovation positively influences financial performance.

2.4. Mediating Role of Technological Innovation in the Entrepreneurship-Performance Link

While entrepreneurship enables firms to proactively identify opportunities and initiate strategic responses, entrepreneurial activity alone does not guarantee superior performance. Under the dynamic capabilities framework, opportunity recognition must be followed by effective implementation in order to generate value. Technological innovation provides the primary mechanism through which entrepreneurial intent is transformed into measurable performance outcomes [27].

Prior research reveals that entrepreneurship enhances firms’ innovation outcomes by fostering openness to new ideas, encouraging experimentation, and facilitating knowledge recombination [34]. These conditions strengthen firms’ ability to develop new products, improve processes, and reconfigure business models. In turn, innovation outcomes contribute to both financial performance—such as revenue growth and profitability—and non-financial performance, including market share, customer satisfaction, and innovation output.

Recent empirical studies further indicate that various forms of innovation, including product, process, and business-model innovation, mediate the relationship between entrepreneurship and firm performance [35,36]. These indirect effects are particularly pronounced under conditions of environmental dynamism and organizational collectivism, where coordinated implementation and learning are essential. This pattern aligns with the dynamic capabilities view, which emphasizes that performance gains arise not from strategic intent alone, but from routinized execution and capability renewal. At the same time, entrepreneurship may also influence performance through strategic coordination, leadership commitment, and decision speed that extend beyond innovation outcomes, suggesting the possibility of partial rather than full mediation.

Accordingly, technological innovation is expected to function as a mediating mechanism linking entrepreneurship to both dimensions of performance. We therefore propose:

H3a.

Technological innovation mediates the impact of entrepreneurship on non-financial performance.

H3b.

Technological innovation mediates the impact of entrepreneurship on financial performance.

2.5. Moderating Role of Sustainable Management

Sustainable management refers to a set of organizational practices addressing economic, social, and environmental responsibilities. These practices shape the organizational context in which entrepreneurship and technological innovation are enacted. Rather than directly generating performance outcomes, sustainable management functions as a boundary condition that influences how effectively entrepreneurial and innovative activities are translated into results. Unlike entrepreneurship and technological innovation, sustainable management does not directly generate new products or services. Instead, it structures the organizational environment in which these activities are evaluated, supported, and rewarded, making it conceptually more appropriate as a moderating rather than mediating mechanism.

Integrating sustainability into governance structures can reduce regulatory uncertainty, align stakeholder expectations, and enhance organizational legitimacy [2]. In addition, sustainability-oriented practices promote transparency, accountability, and resource efficiency, thereby lowering innovation-related risks and supporting continuous renewal. From this perspective, sustainable management conditions the effectiveness of entrepreneurship and technological innovation by structuring decision-making processes, coordination mechanisms, and performance evaluation criteria.

Prior research provides strong support for these arguments. Porter and Kramer [37] suggest that social responsibility and competitiveness can reinforce one another, while Hart and Milstein [38] argue that sustainability initiatives create innovation opportunities and new market spaces. Bansal and Roth [39] identify regulatory, market, and ethical pressures as drivers of sustainability adoption, showing that such practices mitigate legal risks and enhance competitiveness. Empirical studies further demonstrate positive associations between sustainability practices and financial performance [2,40], as well as non-financial outcomes such as employee commitment, reputation, and customer satisfaction [41,42].

Importantly, emerging research indicates that sustainable management is not a homogeneous construct. Economic, social, and environmental dimensions of sustainable management practices may condition entrepreneurial and innovative activities in different ways. Economic sustainable management emphasizes governance, transparency, and risk management; social sustainable management strengthens trust, commitment, and stakeholder cooperation; and environmental sustainable management builds efficiency-oriented and differentiation-based advantages. These dimensions may therefore exert asymmetric moderating effects on the entrepreneurship–performance and innovation–performance relationships.

Based on this logic, we propose the following hypotheses regarding the moderating roles of 3 dimensions in sustainable management.

The economic dimension emphasizes transparency, ethical compliance, risk management, and financial discipline. These elements formalize decision rights and stabilize operational processes. They reduce idiosyncratic risk and support aligned resource allocation. High-sustainability firms typically show stronger governance and incentive alignment for sustainability-related outcomes.

H4a.

Sustainable management (economic dimension) moderates the effect of technological innovation on non-financial performance.

H4b.

Sustainable management (economic dimension) moderates the effect of technological innovation on financial performance.

H5a.

Sustainable management (economic dimension) moderates the effect of entrepreneurship on non-financial performance.

H5b.

Sustainable management (economic dimension) moderates the effect of entrepreneurship on financial performance.

The social dimension is grounded in corporate social responsibility practices that enhance employee commitment and stakeholder trust. These practices facilitate cooperation, knowledge sharing, and market acceptance, which are critical for innovation commercialization and entrepreneurial scaling.

H6a.

Sustainable management (social dimension) moderates the effect of technological innovation on non-financial performance.

H6b.

Sustainable management (social dimension) moderates the effect of technological innovation on financial performance.

H7a.

Sustainable management (social dimension) moderates the effect of entrepreneurship on non-financial performance.

H7b.

Sustainable management (social dimension) moderates the effect of entrepreneurship on financial performance.

The environmental dimension involves proactive environmental management aimed at efficiency improvement and regulatory risk reduction. These practices can generate cost advantages and differentiation benefits that reinforce the performance impact of entrepreneurship and technological innovation.

H8a.

Sustainable management (environmental dimension) moderates the effect of technological innovation on non-financial performance.

H8b.

Sustainable management (environmental dimension) moderates the effect of technological innovation on financial performance.

H9a.

Sustainable management (environmental dimension) moderates the effect of entrepreneurship on non-financial performance.

H9b.

Sustainable management (environmental dimension) moderates the effect of entrepreneurship on financial performance.

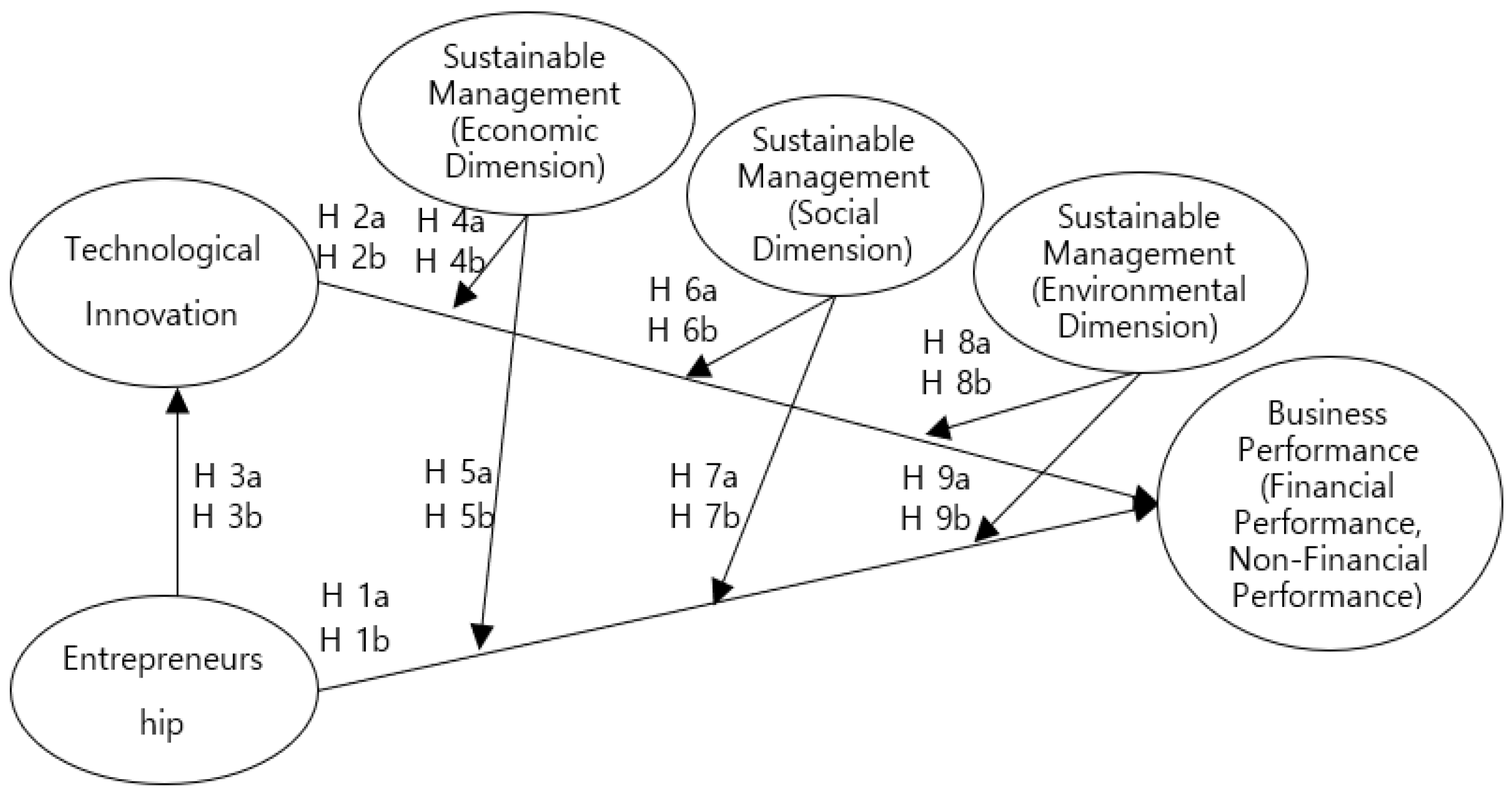

The research model is presented in Figure 1. We theorize the moderated mediation structure. Entrepreneurship influences performance both directly and indirectly through technological innovation. Sustainable management moderates the entrepreneurship–performance and innovation–performance relationships in distinct ways.

Figure 1.

A research model.

3. Methods

3.1. Variables and Measurement Instruments

This study examines how entrepreneurship and technological innovation influence business performance and how sustainable management conditions these relationships. All constructs were operationalized based on established scales in prior research. The survey items used to measure each construct are provided in Appendix A.

Entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurship was measured at the top management team (TMT) level. In line with the dynamic capabilities perspective, entrepreneurship is conceptualized as a strategic activity through which firms engage in opportunity recognition and initiate adaptive responses under uncertainty. Rather than representing a static orientation, entrepreneurship reflects how managerial actions enact sensing and initiate seizing processes within organizations.

Consistent with validated entrepreneurship scales, four items were used to capture executives’ commitment to innovation, perseverance under risk, openness in communication regarding innovation, and receptivity to external knowledge and technology [43,44,45]. These items reflect key entrepreneurial activities that facilitate strategic alignment, cross-functional coordination, and responsiveness to environmental change.

Example questions (5-point Likert scale) include such items as “Our top management shows a strong commitment to technological innovation”, “Our top management perseveres through risks and hardships associated with innovation”, “Communication among executives regarding innovation is open and frequent” and “Top management actively embraces new ideas and external technologies”.

Technological Innovation

Technological innovation was defined in accordance with the OECD/Eurostat Oslo Manual as the implementation of new or significantly improved products and processes [28]. Both product and process innovation were measured to capture the breadth of firms’ innovation activities.

Product innovation was assessed using four items reflecting the speed and number of new product developments, the breadth of the product portfolio, and the firm’s ability to develop new customers and markets. Process innovation was measured using five items capturing improvements in production processes, adoption of advanced manufacturing technologies, reductions in lead time, quality enhancement, and cost reduction [36].

This operationalization aligns with international standards and prior empirical research linking new product advantages, launch proficiency, and process excellence to organizational performance. All items were measured using a 5-point Likert scale.

For product innovation, 4 survey items include “Our firm’s rate of new product development is faster than competitors”, “Our firm has a higher number of new products compared to competitors”, etc. For process innovation, 5 survey items encompass “Our firm actively pursues improvements in production processes”, “We adopt cutting-edge production technologies”, “Production lead times are reduced compared to competitors”, etc.

Although some entrepreneurship items refer to commitment to innovation and openness to external technologies, these items capture managerial intent, orientation, and leadership behaviors rather than realized innovation outcomes. In contrast, technological innovation is operationalized as the actual implementation of product and process innovations. This distinction aligns with the dynamic capabilities perspective, which differentiates between sensing and initiating activities and subsequent seizing and transforming outcomes.

Sustainable Management

Sustainable management was conceptualized as a set of institutionalized organizational routines that structure how entrepreneurship and technological innovation are enacted and evaluated. Rather than directly generating performance outcomes, sustainable management functions as a contextual mechanism that conditions capability deployment [2,30,41,42,43,44,45].

Three dimensions of sustainable management were measured: economic, social, and environmental. All items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale.

The economic dimension reflects governance-oriented practices such as transparency, ethical compliance, risk management, and financial discipline. These practices support board oversight, incentive alignment, and long-term economic stability. Example items of 16 questions include “Our company strives to fulfill its tax obligations faithfully”, “Our company works to improve long-term economic performance”, “Our company strives to improve operating profit and investment returns”, etc.

The social dimension captures practices related to labor standards, human rights, consumer protection, and community engagement. These practices enhance employee commitment, stakeholder trust, and cooperation, thereby facilitating the execution of entrepreneurship and innovation. These practices facilitate the implementation of entrepreneurship and technological innovation. Example items of 16 questions include “Our company faithfully observes labor laws, contracts, and agreements”, “Our company strives to contribute to community development”, “Our company works to protect consumer information and privacy”, etc.

The environmental dimension reflects proactive environmental management practices aimed at improving energy efficiency, reducing emissions, and promoting resource circularity. These practices build efficiency-oriented and differentiation-based advantages that can strengthen innovation outcomes. Example items of 13 questions include “Our company has a dedicated organization to improve energy efficiency and strives for environmental management”, “Our company analyzes international regulatory trends on environmental issues and strives to comply with international agreements”, “Our company has a system for efficient management of resource recycling, continuously manages and discloses performance”, etc.

Business Performance

Business performance was assessed using perceptual, relative performance indicators, which are widely used in entrepreneurship and innovation research. Prior studies demonstrate that perceptual performance measures correlate strongly with objective indicators while allowing consistent comparison across firms of different sizes and industries [46,47,48].

This study intentionally distinguishes between non-financial and financial performance to capture the multidimensional effects of entrepreneurship, innovation, and sustainable management. Aggregating these dimensions may obscure asymmetric effects, particularly when sustainable management practices influence social legitimacy or operational efficiency before financial outcomes are realized [49,50,51].

Non-financial performance was measured using four items capturing market share growth, customer satisfaction, innovation output, and employee satisfaction. Example items include “Our company’s market share has continued to increase over the past three years”, Our market share has expanded continuously over the past three years”, “Employee satisfaction has steadily improved over the past three years”, etc.

Financial performance includes 5 items on profitability, revenue growth, return on investment (ROI), and perceived net income growth. Example questions include “The rate of sales growth over the past three years has been higher than the industry average”, “The net income growth rate over the past three years has been higher than the industry average”, etc.

All performance items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale.

3.2. Data Collection Method

Data was collected through a professional research firm between April and May 2024. Prior to the main survey, a pilot survey involving 100 respondents was conducted to identify ambiguous items and improve the validity of the final questionnaire.

The survey was administered online to 2476 individuals. After excluding incomplete or invalid responses, 300 usable questionnaires were retained for analysis. Participation was voluntary, and all responses were anonymous. No personally identifiable information was collected. In accordance with institutional guidelines, formal institutional review board (IRB) approval was not required for this study.

To enhance representativeness, a stratified sampling approach was used to avoid bias toward specific firm sizes or industries. Firm size, industry classification, and job position were considered when constructing the sample frame.

3.3. Sample Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the demographic and organizational characteristics of the respondents. Of the 300 respondents, 56.7% were male and 43.3% were female. The majority were in their 30 s (51.0%), followed by respondents aged 50 or above (20.0%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of survey participants.

In terms of job position, managers and directors accounted for the largest group (39.3%), followed by deputy managers and assistant managers (27.7%). Respondents were drawn from a wide range of departments, including strategy/planning, marketing/sales, R&D, human resources, production, and finance.

Manufacturing (25.7%), ICT (25.0%), and services (21.7%) were the most represented industries. More than half of the respondents worked in small and medium-sized enterprises (52.7%), followed by medium-sized enterprises (24.3%) and large corporations (20.3%).

3.4. Data Analysis Strategy

To assess the suitability of the data for factor analysis, Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s tests were conducted. All KMO values exceeded 0.8, and Bartlett’s test statistics were significant (p < 0.001), indicating adequate sampling adequacy (Appendix B).

Exploratory factor analysis revealed that the total variance explained exceeded 68% for all constructs. Reliability analysis showed high internal consistency, with Cronbach’s α values of 0.889 for Entrepreneurship and above 0.90 for all other constructs.

Hypotheses were tested using Hayes’ PROCESS macro (Models 4 and 1). Mediation effects were examined using Model 4, and moderation effects were tested using Model 1 with mean-centered variables. A bootstrapping procedure with 5000 resamples was employed to estimate indirect and conditional effects. This approach provides robust statistical inference and is particularly suitable for examining moderated mediation structures involving multidimensional performance outcomes.

4. Results

This section reports the empirical results in three steps. First, descriptive statistics and correlations are presented. Second, the direct and mediating effects of entrepreneurship and technological innovation on firm performance are examined. Third, the moderating effects of sustainable management dimensions are tested separately for non-financial and financial performance to identify asymmetric conditioning patterns.

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation coefficients for the main variables. All variables exhibit acceptable levels of normality, with skewness values below 2 and kurtosis values below 4, indicating no serious violations of distributional assumptions (Table A7 in Appendix C).

Table 2.

Major correlation relationships.

Entrepreneurship is positively and significantly correlated with technological innovation (r = 0.546, p < 0.001), non-financial performance (r = 0.576, p < 0.001), and financial performance (r = 0.602, p < 0.001). Technological innovation also shows strong positive associations with both non-financial (r = 0.525, p < 0.001) and financial performance (r = 0.527, p < 0.001). The three dimensions of sustainable management—economic, social, and environmental—are highly interrelated and positively associated with both performance outcomes, with the environmental dimension exhibiting the strongest correlations.

Overall, the correlation results provide preliminary support for the hypothesized relationships and justify subsequent mediation and moderation analyses.

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

Hypotheses were tested using Hayes’ PROCESS macro. Mediation effects were examined with Model 4 based on 5000 bootstrap resamples, and moderation effects were examined with Model 1 using mean-centered variables [52].

4.2.1. Direct and Mediated Effects of Entrepreneurship on Performance

Table 3 presents the mediation results for non-financial performance. Entrepreneurship had a significant positive effect on technological innovation (β = 0.546, p < 0.001). Entrepreneurship also directly enhanced non-financial performance (β = 0.576, p < 0.001), supporting H1a.

Table 3.

Mediation results for non-financial performance.

When technological innovation was included in the model, it exhibited a significant positive effect on non-financial performance (β = 0.299, p < 0.001), supporting H2a. The direct effect of entrepreneurship remains significant but is reduced in magnitude (β = 0.412, p < 0.001), indicating partial mediation. Bootstrapping results confirm a significant indirect effect of entrepreneurship on non-financial performance via technological innovation (indirect effect = 0.161, 95% CI [0.059, 0.283]; Table A8 in Appendix C) [53]. Thus, H3a is supported.

Table 4 shows the mediation results for financial performance. Entrepreneurship significantly predicted financial performance (β = 0.602, p < 0.001), supporting H1b. Technological innovation had a significant positive effect on financial performance (β = 0.283, p < 0.001), supporting H2b.

Table 4.

Mediation results for financial performance.

After controlling technological innovation, the effect of entrepreneurship remains significant (β = 0.448, p < 0.001), indicating partial mediation. The bootstrapped indirect effect of entrepreneurship via technological innovation is significant (indirect effect = 0.165, 95% CI [0.059, 0.284]; Table A9 in Appendix C) [53]. Accordingly, H3b is supported.

4.2.2. Moderating Effects on Non-Financial Performance

The interaction effects between the economic dimension of sustainable management and entrepreneurship, as well as technological innovation, are not statistically significant (p > 0.05). The results indicate that governance- and control-oriented sustainable management practices do not condition the non-financial performance effects of entrepreneurship or technological innovation. Accordingly, H4a and H5a are not supported.

Similarly, the interaction terms involving the social dimension of sustainable management are not significant for non-financial performance (p > 0.05). Thus, H6a and H7a are not supported. This pattern suggests that social sustainable management practices do not directly enhance non-financial performance returns to entrepreneurship or innovation.

In contrast, the environmental dimension of sustainable management exhibited significant moderating effects on non-financial performance. As shown in Table 5, the interaction between entrepreneurship and environmental sustainable management is positive and significant (β = 0.062, p < 0.05). The verification analysis indicates that the effect of entrepreneurship on non-financial performance increased as environmental sustainable management intensified.

Table 5.

The moderating effect of sustainable management (environmental dimension) on non-financial performance.

Likewise, the interaction between technological innovation and environmental sustainable management was significant (β = 0.117, p < 0.001). The bootstrapping analysis confirmed that the impact of technological innovation on non-financial performance was stronger at higher levels of environmental sustainable management. Accordingly, H8a and H9a are supported.

4.2.3. Moderating Effects on Financial Performance

No significant interaction effects are found between the economic dimension of sustainable management and either entrepreneurship or technological innovation in predicting financial performance (p > 0.05). Therefore, H4b and H5b are not supported.

As reported in Table 6, the social dimension significantly moderated the relationship between entrepreneurship (β = 0.108, p < 0.01) and technological innovation (β = 0.119, p < 0.001) on financial performance. Simple slope analyses indicated that entrepreneurship and technological innovation exerted stronger effects on financial performance at higher levels of social sustainable management, respectively. The results support H6b and H7b.

Table 6.

The moderating effect of sustainable management (social dimension) on financial performance.

Table 7 shows that the environmental dimension of sustainable management significantly moderates the effects of both entrepreneurship (β = 0.135, p < 0.001) and technological innovation (β = 0.134, p < 0.001) on financial performance. The bootstrapping results indicated that the positive effects of entrepreneurship and technological innovation on financial performance intensified with higher levels of environmental sustainable management. These findings indicate that environmental sustainable management consistently amplifies the financial performance benefits of entrepreneurial sensing and innovative seizing activities. Thus, H8b and H9b are supported.

Table 7.

The moderating effect of sustainable management (environmental dimension) on financial performance.

4.3. Summary of Results

Overall, the results suggest a differentiated pattern across sustainable management dimensions. The economic dimension did not moderate the effects of entrepreneurship or technological innovation on either performance outcome. The social dimension selectively strengthened financial performance effects, while the environmental dimension consistently amplified both financial and non-financial performance outcomes. These findings demonstrate that sustainable management does not uniformly enhance performance but instead conditions entrepreneurial and innovative returns in dimension-specific ways. Building on this differentiated pattern across sustainability dimensions, the discussion section interprets the findings through a dynamic capabilities lens and clarifies their theoretical and managerial implications.

5. Discussion

This study investigated how entrepreneurship and technological innovation jointly shape business performance under sustainability-intensive conditions, drawing on the dynamic capabilities perspective. This study responds to recent calls to move beyond linear ESG–performance relationships by explicitly modeling sustainable management as a contextual moderator, rather than as a direct antecedent or outcome [2,14,19]. Furthermore, we clarify that sustainability functions as a contextual capability that conditions the translation of entrepreneurship and technological innovation into performance outcomes. The findings provide strong empirical support for the proposed moderated mediation framework and yield several important theoretical and managerial insights.

First, consistent with prior research, entrepreneurship and technological innovation exert significant positive effects on both non-financial and financial performance. Entrepreneurship enhances non-financial (H1a) and financial performance (H1b), while technological innovation positively influences both outcome dimensions (H2a, H2b). These findings are well aligned with extensive empirical evidence, which confirms that entrepreneurship and innovation capability are central drivers of firm performance across industries and institutional contexts [26,27,32,33,34,35]. From a dynamic capabilities perspective, entrepreneurship reflects opportunity sensing and initial resource commitment, whereas technological innovation captures the conversion of such commitments into implementable outcomes [13,14,15,16,17,18,33].

Beyond these direct effects, the mediation analyses reveal that technological innovation partially mediates the relationship between entrepreneurship and both non-financial (H3a) and financial performance (H3b). This finding supports prior research suggesting that entrepreneurial intent must be translated into concrete innovation outputs to generate sustained performance advantages [22,34,35,36]. At the same time, the persistence of significant direct effects indicates partial rather than full mediation. This implies that entrepreneurship also affects performance through complementary mechanisms such as leadership commitment, strategic coordination, and accelerated decision-making that extend beyond formal innovation outcomes [25,28,33]. By clarifying innovation as a central—but not exclusive—pathway, this study refines entrepreneurship–innovation–performance models within the dynamic capabilities framework.

The results suggest that in ESG-institutionalized environments, economic sustainable management practices may function as baseline institutional conditions rather than strategic differentiators, limiting their ability to amplify marginal performance returns.

A central contribution of this study lies in demonstrating that sustainable management does not uniformly enhance firm performance. Instead, sustainable management functions as a dimension-specific contextual capability that asymmetrically conditions the effectiveness of entrepreneurship and technological innovation. Contrary to expectations, the economic dimension of sustainable management did not significantly moderate the effects of entrepreneurship or technological innovation on either non-financial or financial performance (H4a–H5b not supported). Notably, this non-significant result is theoretically meaningful rather than problematic. Governance-oriented practices such as transparency, ethical compliance, and financial discipline primarily stabilize organizational operations and reduce downside risk [2,40]. In ESG-institutionalized environments, these practices increasingly represent minimum legitimacy requirements rather than strategic differentiators, limiting their ability to amplify marginal returns to sensing or seizing activities. From a dynamic capabilities perspective, the economic dimension operates as a baseline governance infrastructure, enabling capability deployment without strengthening its performance impact [14,19].

In contrast, the social and environmental dimensions of sustainable management exhibited differentiated and theoretically consistent moderating effects. The social dimension strengthened the relationships between entrepreneurship and financial performance (H7b) and between technological innovation and financial performance (H6b), while showing no significant moderation for non-financial performance (H6a, H7a not supported). This pattern suggests that social sustainable management practices—such as labor standards, human rights management, and community engagement—primarily enhance reputational capital, stakeholder trust, and market legitimacy [38,42,43]. These legitimacy-based mechanisms are more directly reflected in financial outcomes such as revenue growth and profitability than in internal or operational indicators captured by non-financial performance measures. This finding aligns with stakeholder theory and CSR research emphasizing that social legitimacy facilitates value appropriation rather than immediate operational improvement [37,40,41,42].

The environmental dimension demonstrated the most consistent and robust moderating effects, amplifying the impact of entrepreneurship on both non-financial (H9a) and financial performance (H9b), as well as strengthening the effects of technological innovation on non-financial (H8a) and financial performance (H8b). This pattern suggests that proactive environmental management enhances firms’ transforming capabilities by improving eco-efficiency, process optimization, and long-term capability renewal [14,19,30,38]. While environmental initiatives often involve substantial upfront investment and delayed payoffs, the findings suggest that such practices ultimately reinforce both internal performance outcomes and long-term financial viability by deepening firms’ capability base and reducing regulatory and resource-related risks [38].

Taken together, these findings directly address the research questions posed in this study. Entrepreneurship and technological innovation jointly influence financial and non-financial performance through both direct and mediated pathways. Technological innovation serves as a key mechanism through which entrepreneurship is converted into performance outcomes. Most importantly, economic, social, and environmental sustainable management dimensions condition these relationships in asymmetric ways. While prior research has primarily examined how sustainability-oriented practices stimulate innovation [54], our findings advance a mechanism-based view by showing that sustainable management conditions how entrepreneurship and technological innovation translate into performance outcomes within a dynamic capabilities framework. By demonstrating that sustainable management alters the effectiveness, rather than the existence, of entrepreneurship–performance and innovation–performance relationships, this study moves beyond confirmatory testing and advances a context-sensitive understanding of capability deployment under ESG-intensive conditions [2,14,19].

Theoretical Implications

This study contributes to the dynamic capabilities literature by extending it into the sustainable management domain in three important ways. First, it reconceptualizes sustainable management as a contextual capability that governs how sensing, seizing, and transforming activities translate into performance outcomes. Whereas prior research often treats sustainability as a homogeneous construct or a direct performance driver, this study demonstrates that sustainable management reshapes the slope of entrepreneurship–performance and innovation–performance relationships rather than their baseline existence [13,14,15,16,19].

Second, by disaggregating sustainable management into economic, social, and environmental dimensions, this study explains why prior empirical findings on sustainability and performance have been inconsistent. The results show that different sustainable management dimensions condition different performance outcomes through distinct mechanisms, highlighting the importance of legitimacy, stakeholder alignment, and eco-efficiency routines in shaping capability deployment [2,30,38].

Third, the non-significant moderating role of economic sustainable management advances theory by distinguishing between foundational and amplifying capabilities. Governance-oriented sustainable management practices enable organizational stability and compliance but do not necessarily enhance marginal performance returns in institutionalized ESG environments. This layered view of capabilities enriches dynamic capabilities theory by clarifying how baseline infrastructures and strategic amplifiers interact in value creation processes [14,19,40].

Managerial Implications

The findings offer clear, dimension-specific managerial implications. Economic sustainable management practices should be treated as essential governance foundations that ensure compliance, transparency, and risk control but are unlikely to generate incremental performance gains on their own [2,40]. Managers should therefore avoid over-allocating strategic resources to compliance-oriented ESG activities in isolation and instead integrate them with entrepreneurial and innovation initiatives.

Social sustainable management emerges as a strategic lever for enhancing the financial returns to entrepreneurship and technological innovation. Practices related to employee welfare, human rights, and community engagement strengthen stakeholder trust and reputational capital, thereby facilitating market acceptance and commercialization of innovation outcomes [37,41,46]. Managers should align social sustainable management initiatives with branding, marketing, and customer-facing innovation strategies rather than treating them as peripheral CSR programs.

Environmental sustainable management should be approached as a long-term capability-building investment. The consistent moderating effects observed suggest that eco-efficiency, process optimization, and regulatory anticipation reinforce innovation outcomes and entrepreneurial effectiveness over time [30,38]. Managers should strategically integrate environmental initiatives with R&D, process innovation, and digital transformation efforts to unlock synergies that improve internal efficiency while opening access to emerging green markets. Collectively, these findings caution against one-size-fits-all ESG strategies and underscore the need for selective, strategically aligned sustainability investments.

6. Concluding Remarks

This study demonstrates that sustainable management does not uniformly enhance firm performance but instead governs how entrepreneurship and technological innovation are translated into value. Drawing on the dynamic capabilities perspective, the findings show that entrepreneurship improves both non-financial and financial performance directly and indirectly through technological innovation. Furthermore, the strength of these effects depends on the specific dimension of sustainable management. By disaggregating sustainable management into economic, social, and environmental dimensions, this study explains why similar entrepreneurial and innovative efforts yield divergent performance outcomes under ESG-intensive conditions and advances a context-sensitive understanding of capability deployment [2,14,19].

Several limitations suggest avenues for future research. The reliance on perceptual survey data may introduce common method bias, and future studies could incorporate objective indicators such as financial statements, patent counts, or environmental performance metrics [49,50,51]. The cross-sectional design limits insight into temporal dynamics, particularly for sustainability investments with delayed payoffs. Longitudinal and cross-national studies would further enhance understanding of how entrepreneurship, innovation, and sustainable management interact over time and across institutional contexts. Despite these limitations, this study offers a theoretically grounded and empirically supported framework for understanding when and how sustainable management amplifies entrepreneurial and innovative value creation under ESG-intensive conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.-J.S. and Y.K.; methodology; W.-J.S., J.J. and Y.K.; investigation, W.-J.S. and W.L.; writing—original draft preparation, W.-J.S., W.L. and J.J.; writing—review and editing, J.J. and Y.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study according to Korea University Research Ethics Regulations, Chapter 5: Protection of Human Participants), prior IRB approval and written informed consent are required for interventional or clinical research involving identifiable human participants, physical intervention, or direct interaction.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Each statement is evaluated on a Likert-type scale: 1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Agree, 5 = Strongly Agree

Entrepreneurship

- Our top management shows a strong commitment to technological innovation.

- Our top management perseveres through risks and hardships associated with innovation.

- Communication among executives regarding innovation is open and frequent.

- Top management actively embraces new ideas and external technologies.

Technological Innovation

[Product Innovation]

- Our rate of new product development is faster than competitors.

- We have a larger number of new products compared to competitors.

- We actively diversify our product range.

- We actively develop new customer markets through product innovation.

[Process Innovation]

- We actively seek to improve production processes.

- We adopt advanced manufacturing technologies.

- Our production lead times are shorter than competitors’.

- We invest in improving product quality.

- We make efforts to reduce production costs.

Sustainable Management—Economic Dimension

[Transparency/Ethical Management]

- Our company strives to fulfill its tax obligations faithfully.

- Our company endeavors to enhance transparency in accounting.

- Our company works to prevent bribery and corruption.

- Our company makes ethical decisions.

- Our company has introduced and is constantly striving to practice a code of ethics and ethical management guidelines.

- Our company discloses management information and strives to ensure corporate transparency.

[Crisis Management]

- Our company continuously strives to improve the quality of products and services.

- Our company works to improve long-term economic performance.

- Our company actively and proactively responds to competitive environments.

- Our company seeks to undertake joint technology and R&D efforts with business partners.

- Our company analyzes risk factors and endeavors to respond proactively.

[Financial Management]

- Our company strives to improve operating profit and investment returns.

- Our company strives to enhance productivity and create added value.

- Our company strives to improve managerial efficiency.

- Our company strives to improve product quality and service.

- Our company strives to increase profitability.

Sustainable Management—Social Dimension

[Human Rights Management]

- Our company strives to prevent discrimination in employment by race, gender, or educational background.

- Our company faithfully observes labor laws, contracts, and agreements.

- Our company provides opportunities for employees for training and self-development.

- Our company works to prevent discrimination in employee compensation and promotion.

- Our company has systems in place for employee health and safety and makes efforts to offer sufficient support and assistance.

- Our company operates programs to support women’s health, childbirth, and childcare.

[Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)]

- Our company actively generates jobs through vibrant hiring activities.

- Our company strives to contribute to community development.

- Our company endeavors to successfully carry out public-interest projects such as supporting education, culture, and the arts.

- Our company has a CSR organization and strives for comprehensive management at the corporate level.

- Our company endeavors to participate in donation activities.

[Consumer Safety]

- Our company sincerely fulfills after-sales service for its products and services.

- Our company regularly surveys customer satisfaction and opinions, and reflects the results.

- Our company operates a dedicated organization for consumer protection and product responsibility and strives accordingly.

- Our company endeavors to conduct consumer-centered business activities.

- Our company works to protect consumer information and privacy.

Sustainable Management—Environmental Dimension

[Energy Efficiency]

- Our company has a dedicated organization to improve energy efficiency and strives for environmental management.

- Our company makes efforts to improve energy efficiency and openly discloses those results externally.

- Our company actively operates systems to save direct/indirect energy and resources and makes efforts to promote externally.

- Our company endeavors to develop and use renewable energy.

- Our company strives for environmental management policies aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

[Environmental Pollution]

- Our company regularly measures and strives to reduce waste emissions and greenhouse gas emissions.

- Our company analyzes environmental risk factors and endeavors to respond accordingly.

- Our company strives to improve environmental impact caused by pollution.

- Our company analyzes international regulatory trends on environmental issues and strives to comply with international agreements.

[Resource Recycling]

- Our company has a system for efficient management of resource recycling, continuously manages and discloses performance.

- Our company has formalized policies and systems for resource recycling and strives to understand environmental impacts.

- Our company makes efforts to use renewable and environmentally friendly raw materials.

- Our company has a dedicated department and programs for resource recycling and strives for their implementation.

Business Performance

[Non-Financial]

- Our company’s market share has continued to increase over the past three years.

- Customer satisfaction has consistently improved over the past three years.

- Business process efficiency has continuously improved over the past three years.

- The number of patents/intellectual property rights has increased over the past three years.

- Employee satisfaction has steadily improved over the past three years.

[Financial]

- 6.

- The rate of sales growth over the past three years has been higher than the industry average.

- 7.

- The operating profit margin over the past three years has been higher than the industry average.

- 8.

- The return on investment (ROI) over the past three years has been higher than the industry average.

- 9.

- The net income growth rate over the past three years has been higher than the industry average.

Appendix B

Table A1.

Appropriateness and Reliability of Entrepreneurship Factors.

Table A1.

Appropriateness and Reliability of Entrepreneurship Factors.

| Classification | 1 Factor (Entrepreneurship) | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurship 4 | 0.870 | 0.889 |

| Entrepreneurship 1 | 0.869 | |

| Entrepreneurship 3 | 0.868 | |

| Entrepreneurship 2 | 0.856 | |

| Eigenvalue | 3.000 | |

| Explained Variance (%) | 74.991 | |

| Cumulative Variance (%) | 74.991 | |

| KMO = 0.840 Bartlett’s sphericity assumption [X2 = 655.287, df = 6, p < 0.001] | ||

Table A2.

Appropriateness and Reliability of Technological Innovation Factors.

Table A2.

Appropriateness and Reliability of Technological Innovation Factors.

| Classification | 1 Factor (Process Innovation/ Technological Innovation) | 2 Factors (Product Innovation/ Technological Innovation) | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|

| Process Innovation/ Technological Innovation 4 | 0.813 | 0.338 | 0.913 |

| Process Innovation/ Technological Innovation 5 | 0.789 | 0.338 | |

| Process Innovation/ Technological Innovation 1 | 0.773 | 0.379 | |

| Process Innovation/ Technological Innovation 3 | 0.763 | 0.422 | |

| Process Innovation/ Technological Innovation 2 | 0.704 | 0.462 | |

| Product Innovation/ Technological Innovation 2 | 0.341 | 0.802 | 0.890 |

| Product Innovation/ Technological Innovation 1 | 0.386 | 0.800 | |

| Product Innovation/ Technological Innovation 4 | 0.402 | 0.766 | |

| Product Innovation/ Technological Innovation 3 | 0.383 | 0.752 | |

| High Value | 3.532 | 3.198 | 0.938 |

| Explained Variance (%) | 39.240 | 35.528 | |

| Cumulative Variance (%) | 39.240 | 74.769 | |

| KMO = 0.948 Bartlett’s sphericity assumption [X2 = 1930.673, df = 36, p < 0.001] | |||

Table A3.

Appropriateness and Reliability of Sustainable Management (Economic Dimension) Factors.

Table A3.

Appropriateness and Reliability of Sustainable Management (Economic Dimension) Factors.

| Classification | Factor 1 (Transparent Management) | Factor 2 (Crisis Management) | Factor 3 (Financial Performance) | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transparent Management 6 | 0.793 | 0.291 | 0.219 | 0.916 |

| Transparent Management 5 | 0.768 | 0.111 | 0.367 | |

| Transparent Management 3 | 0.731 | 0.334 | 0.295 | |

| Transparent Management 2 | 0.708 | 0.324 | 0.302 | |

| Transparent Management 4 | 0.696 | 0.403 | 0.257 | |

| Transparent Management 1 | 0.688 | 0.418 | 0.170 | |

| Crisis Management 5 | 0.315 | 0.771 | 0.272 | 0.892 |

| Crisis Management 4 | 0.207 | 0.739 | 0.330 | |

| Crisis Management 3 | 0.362 | 0.684 | 0.306 | |

| Crisis Management 2 | 0.364 | 0.656 | 0.287 | |

| Crisis Management 1 | 0.395 | 0.634 | 0.336 | |

| Financial Performance 5 | 0.310 | 0.166 | 0.793 | 0.899 |

| Financial Performance 2 | 0.231 | 0.342 | 0.767 | |

| Financial Performance 1 | 0.246 | 0.343 | 0.759 | |

| Financial Performance 3 | 0.303 | 0.459 | 0.637 | |

| Financial Performance 4 | 0.382 | 0.384 | 0.600 | |

| Eigenvalue | 4.221 | 3.713 | 3.487 | 0.953 |

| Explained Variance (%) | 26.380 | 23.206 | 21.793 | |

| Cumulative Variance (%) | 26.380 | 49.586 | 71.379 | |

| KMO = 0.962 Bartlett’s sphericity assumption [X2 = 3456.382, df = 120, p < 0.001] | ||||

Table A4.

Appropriateness and Reliability of Sustainable Management (Social Dimension) Factors.

Table A4.

Appropriateness and Reliability of Sustainable Management (Social Dimension) Factors.

| Classification | Factor 1 (Human Rights Management) | Factor 2 (Consumer Safety) | Factor 3 (Corporate Social Responsibility) | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Rights Management 2 | 0.767 | 0.221 | 0.205 | 0.900 |

| Human Rights Management 4 | 0.746 | 0.215 | 0.288 | |

| Human Rights Management 6 | 0.741 | 0.212 | 0.251 | |

| Human Rights Management 1 | 0.735 | 0.216 | 0.250 | |

| Human Rights Management 3 | 0.729 | 0.311 | 0.246 | |

| Human Rights Management 5 | 0.698 | 0.289 | 0.307 | |

| Consumer Safety 1 | 0.308 | 0.789 | 0.133 | 0.895 |

| Consumer Safety 4 | 0.233 | 0.769 | 0.284 | |

| Consumer Safety 5 | 0.259 | 0.762 | 0.251 | |

| Consumer Safety 3 | 0.225 | 0.743 | 0.333 | |

| Consumer Safety 2 | 0.260 | 0.696 | 0.352 | |

| Corporate Social Responsibility 5 | 0.231 | 0.234 | 0.752 | 0.886 |

| Corporate Social Responsibility 4 | 0.312 | 0.274 | 0.746 | |

| Corporate Social Responsibility 3 | 0.243 | 0.276 | 0.742 | |

| Corporate Social Responsibility 1 | 0.314 | 0.219 | 0.718 | |

| Corporate Social Responsibility 2 | 0.293 | 0.291 | 0.715 | |

| Eigenvalue | 3.980 | 3.536 | 3.503 | 0.941 |

| Explained Variance (%) | 24.873 | 22.098 | 21.892 | |

| Cumulative Variance (%) | 24.873 | 46.971 | 68.863 | |

| KMO = 0.950 Bartlett’s sphericity assumption [X2 = 3022.361, df = 120, p < 0.001] | ||||

Table A5.

Appropriateness and Reliability of Sustainable Management (Environmental Dimension) Factors.

Table A5.

Appropriateness and Reliability of Sustainable Management (Environmental Dimension) Factors.

| Classification | 1st Factor (Energy Efficiency) | 2nd Factor (Resource Recycling) | 3rd Factor (Environmental Pollution) | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Efficiency 3 | 0.846 | 0.290 | 0.291 | 0.925 |

| Energy Efficiency 4 | 0.755 | 0.279 | 0.373 | |

| Energy Efficiency 1 | 0.676 | 0.367 | 0.389 | |

| Energy Efficiency 2 | 0.654 | 0.445 | 0.354 | |

| Energy Efficiency 5 | 0.631 | 0.497 | 0.324 | |

| Resource Recycling 4 | 0.258 | 0.806 | 0.341 | 0.907 |

| Resource Recycling 1 | 0.340 | 0.765 | 0.277 | |

| Resource Recycling 2 | 0.323 | 0.752 | 0.349 | |

| Resource Recycling 3 | 0.447 | 0.673 | 0.289 | |

| Environmental Pollution 3 | 0.294 | 0.329 | 0.814 | 0.916 |

| Environmental Pollution 2 | 0.417 | 0.279 | 0.740 | |

| Environmental Pollution 1 | 0.391 | 0.309 | 0.738 | |

| Environmental Pollution 4 | 0.296 | 0.488 | 0.687 | |

| Eigenvalue | 3.556 | 3.513 | 3.228 | 0.961 |

| Explained Variance (%) | 27.354 | 27.025 | 24.834 | |

| Cumulative Variance (%) | 27.354 | 54.379 | 79.213 | |

| KMO = 0.959 Bartlett’s sphericity assumption [X2 = 3500.058, df = 78, p < 0.001] | ||||

Table A6.

Appropriateness and Reliability of Business Performance Factors.

Table A6.

Appropriateness and Reliability of Business Performance Factors.

| Division | 1 Factor (with Financial Performance) | 2 Factors (with Financial Performance) | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Financial Performance 5 | 0.813 | 0.303 | 0.899 |

| Non-Financial Performance 2 | 0.798 | 0.304 | |

| Non-Financial Performance 1 | 0.773 | 0.348 | |

| Non-Financial Performance 3 | 0.772 | 0.326 | |

| Non-Financial Performance 4 | 0.755 | 0.302 | |

| Financial Performance 4 | 0.263 | 0.842 | 0.903 |

| Financial Performance 2 | 0.350 | 0.835 | |

| Financial Performance 1 | 0.326 | 0.812 | |

| Financial Performance 3 | 0.423 | 0.756 | |

| Eigenvalue | 3.538 | 3.137 | 0.927 |

| Explained Variance (%) | 39.315 | 34.857 | |

| Cumulative Variance (%) | 39.315 | 74.171 | |

| KMO = 0.927 Bartlett’s sphericity assumption [X2 = 1822.209, df = 36, p < 0.001] | |||

Appendix C

Table A7.

Descriptive Statistics of the Major Variables.

Table A7.

Descriptive Statistics of the Major Variables.

| Division | Average | Standard Deviation | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurship | 3.42 | 0.90 | −0.50 | −0.06 | |

| Technological Innovation | 3.29 | 0.89 | −0.78 | 0.71 | |

| Sustainable Management (Economic Dimension) | 3.45 | 0.78 | −0.76 | 0.91 | |

| Sustainable Management (Social Dimension) | 3.38 | 0.76 | −0.65 | 0.77 | |

| Sustainable Management (Environmental Dimension) | 3.39 | 0.90 | −0.59 | 0.00 | |

| Business Performance | Non-Financial Performance | 3.28 | 0.89 | −0.62 | 0.02 |

| Financial Performance | 3.13 | 0.96 | −0.46 | −0.25 | |

| Overall | 3.21 | 0.85 | −0.54 | 0.10 | |

(N = 300).

Table A8.

Bootstrapped Indirect Effects of Technological Innovation on the Relationship Between Entrepreneurship and Non-Financial Performance.

Table A8.

Bootstrapped Indirect Effects of Technological Innovation on the Relationship Between Entrepreneurship and Non-Financial Performance.

| Effect | SE | 95% Confidence Interval | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Value | Upper Value | |||

| Total Effect | 0.567 | 0.047 | 0.475 | 0.659 |

| Direct Effect | 0.406 | 0.053 | 0.301 | 0.510 |

| Indirect Effect | 0.161 | 0.058 | 0.059 | 0.283 |

Table A9.

Bootstrapped Indirect Effects of Technological Innovation on the Relationship Between Entrepreneurship and Financial Performance.

Table A9.

Bootstrapped Indirect Effects of Technological Innovation on the Relationship Between Entrepreneurship and Financial Performance.

| Effect | SE | 95% Confidence Interval | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||

| Total Effect | 0.641 | 0.049 | 0.544 | 0.738 |

| Direct Effect | 0.477 | 0.056 | 0.366 | 0.587 |

| Indirect Effect | 0.165 | 0.058 | 0.059 | 0.284 |

References

- BlackRock. Larry Fink’s 2022 CEO Letter to CEOs: The Power of Capitalism. BlackRock, New York, NY, USA. 2022. Available online: https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/investor-relations/larry-fink-ceo-letter (accessed on 29 January 2026).

- Eccles, R.G.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. The Impact of Corporate Sustainability on Organizational Processes and Performance. Manag. Sci. 2014, 60, 2835–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Partnerships from cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st-century business. Environ. Qual. Manag. 1998, 8, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelb, J.; McCarthy, R.; Rehm, W.; Voronin, A. Investors Want to Hear from Companies About the Value of Sustainability; McKinsey & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/investors-want-to-hear-from-companies-about-the-value-of-sustainability (accessed on 20 January 2026).

- United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2025; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2025; Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2025/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2025.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2026).

- Wang, T.; Bansal, P. Social responsibility in new ventures: Profiting from a long-term orientation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 1135–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, D.; O’Dochartaigh, A.; Prothero, A.; Reynolds, O. Are you ready for the sustainable, biocircular economy? Bus. Horiz. 2023, 66, 805–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engert, S.; Rauter, R.; Baumgartner, R.J. Corporate sustainability strategy—Bridging the gap between formulation and implementation. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 113, 822–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.L.; Kanbach, D.K. Toward a view of integrating corporate sustainability into strategy: A systematic literature review. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 962–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; Harrison, J.S.; Wicks, A.C. Managing for Stakeholders: Survival, Reputation, and Success; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, R.; Jeanrenaud, S.; Bessant, J.; Denyer, D.; Overy, P. Sustainability-oriented Innovation: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2016, 18, 180–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D.R. Post-innovation CSR Performance and Firm Value. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 285–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3088148 (accessed on 20 January 2026). [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Martin, J.A. Dynamic capabilities: What are they? In The SMS Blackwell Handbook of Organizational Capabilities; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating Dynamic Capabilities: The Nature and Microfoundations of (Sustainable) Enterprise Performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20141992 (accessed on 20 January 2026). [CrossRef]

- Bornay Barrachina, M.; López Cabrales, Á.; Salas Vallina, A. Sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring dynamic capabilities in innovative firms: Why does strategic leadership make a difference? Bus. Res. Q. 2023, 26, 399–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L.; Ahmed, P.K. Dynamic capabilities: A review and research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2007, 9, 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosini, V.; Bowman, C. What are dynamic capabilities and are they a useful construct in strategic management? Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2009, 11, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, R.J. Managing Corporate Sustainability and CSR: A Conceptual Framework Combining Values, Strategies and Instruments Contributing to Sustainable Development. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2014, 21, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Y.; Simsek, Z.; Lubatkin, M.H.; Veiga, J.F. Transformational Leadership’s Role in Promoting Corporate Entrepreneurship: Examining the CEO-TMT Interface. Acad. Manag. J. 2008, 51, 557–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Covin, J.G. Contextual influences on the corporate entrepreneurship–performance relationship: A longitudinal analysis. J. Bus. Ventur. 1995, 10, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, J.; Shepherd, D. Entrepreneurial orientation and small business performance: A configurational approach. J. Bus. Ventur. 2005, 20, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, A.; Wiklund, J.; Lumpkin, G.T.; Frese, M. Entrepreneurial Orientation and Business Performance: An Assessment of past Research and Suggestions for the Future. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 761–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-H.; Huang, J.-W.; Tsai, M.-T. Entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance: The role of knowledge creation process. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2009, 38, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-K.; Chung, H.-C. The Relationship Between Entrepreneurial Orientation and Firm Performance From the perspective of MASEM: The Mediation Effect of Market Orientation and the Moderated Mediation Effect of Environmental Dynamism. SAGE Open 2023, 13, 21582440231218804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gameti, D.; Morrish, S. Entrepreneurial orientation and SME growth: The mediating effect of product, process, and business model innovations. J. Res. Mark. Entrep. 2025, 27, 232–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Sapienza, H.J.; Davidsson, P. Entrepreneurship and Dynamic Capabilities: A Review, Model and Research Agenda. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 917–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD/Eurostat. Oslo Manual: Guidelines for Collecting and Interpreting Innovation Data, 3rd ed.; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2005; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2005/11/oslo-manual_g1gh5dba/9789264013100-en.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2026).

- Jansen, J.J.P.; Vera, D.; Crossan, M. Strategic leadership for exploration and exploitation: The moderating role of environmental dynamism. Leadersh. Q. 2009, 20, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gamero, M.D.; Molina-Azorín, J.F.; Claver-Cortés, E. The whole relationship between environmental variables and firm performance: Competitive advantage and firm resources as mediator variables. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 3110–3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, B.; Samson, D. Developing innovation capability in organisations: A Dynamic Capabilities Approach. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2001, 5, 377–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossan, M.M.; Apaydin, M. A multi-dimensional framework of organizational innovation: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Manag. Stud. 2010, 47, 1154–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.I. Organization, trust and control: A realist analysis. Organ. Stud. 2001, 22, 201–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, W.M.; Levinthal, D.A. Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Adm. Sci. Q. 1990, 35, 128–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berson, Y.; Shamir, B.; Avolio, B.J.; Popper, M. The relationship between vision strength, leadership style, and context. Leadersh. Q. 2001, 12, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langerak, F.; Hultink, E.J.; Robben, H.S.J. Market orientation and new product performance. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2004, 21, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Strategy and society. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, S.L.; Milstein, M.B. Creating sustainable value. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2003, 17, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]