Abstract

Water scarcity in arid/semi-arid regions restricts agricultural sustainability systems and hinders the achievement of regional sustainable development goals, especially in northwest China’s extremely arid areas, where acute water supply–demand conflicts and inefficient traditional practices intensify competition for water between agricultural and ecological sectors. This study aims to verify the effectiveness of an intelligent automatic irrigation system in mitigating water scarcity pressures and enhancing agricultural sustainability in the Shule River Basin of northwestern China, a region where traditional irrigation methods not only yield suboptimal crop outputs but also undermine long-term water resource sustainability. A smart irrigation module, integrating “sensing–decision–execution” processes, was embedded within a digital twin platform to enable precise, resource-efficient water management that aligns with sustainable development principles. Sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.), the most popular cash crop in the area, was used as the test crop, with three soil moisture-based irrigation levels compared against traditional farmer practices. Key indicators including leaf area index (LAI), dry biomass, grain yield, and irrigation water use efficiency (IWUE) were systematically evaluated. The results showed that (1) LAI increased from the seedling to flowering stage, with smart irrigation treatments significantly outperforming farmer practices in both crop growth and water-saving effects, laying a foundation for sustainable yield improvement; (2) total dry biomass at maturity was positively correlated with irrigation amount but smart irrigation optimized the allocation of water resources to avoid waste, balancing productivity and sustainability; (3) grain yield peaked within 70–89% field capacity (fc), with further increases leading to diminishing returns and unnecessary water consumption that impairs sustainable water use; (4) IWUE followed a parabolic trend, reaching its maximum under the same optimal irrigation range, indicating that smart irrigation can maximize water productivity while preserving water resources for ecological and future agricultural needs. The digital twin-driven smart irrigation system enhances both crop yield and water productivity in arid regions, providing a scalable model for precision water management in water-stressed agricultural zones. The results provide a key empirical basis and technical approach for sustainably using irrigation water, optimizing water–energy–food–ecology synergy, and advancing sustainable agriculture in arid regions of Northwest China, which is crucial for achieving regional sustainable development objectives amid worsening water scarcity.

1. Introduction

With the exacerbation of climate change and the expansion of cropland, irrigation water demand has surged in arid regions [1,2,3]. This trend has intensified water supply–demand imbalances, undermined agricultural production in northwestern China, and posed a severe threat to the region’s agricultural sustainability [4]. As a core component of sustainable agriculture, the rational utilization of water resources is pivotal for maintaining the ecological balance of arid areas and ensuring the long-term stability of agricultural production systems.

Currently, traditional irrigation models reliant on manual experience remain prevalent irrigation districts across arid region. Farmers mostly determine irrigation frequency and quota based on subjective perceptions accumulated through years of planting, lacking scientific guidance from crop physiological water demand rules, dynamic soil moisture conditions, and climatic factors. This leads to considerable randomness and arbitrariness in irrigation decision making. Such extensive irrigation models have given rise to dual ecological and production problems. First, the uncertainty of irrigation frequency tends to subject crops to periodic drought stress, disrupting key physiological processes such as photosynthesis and nutrient absorption [5,6], which not only reduces yield but also impairs the resilience of agricultural ecosystems. Second, farmers’ subjective inclination to avoid drought risks often leads to over-irrigation, with irrigation quotas far exceeding crops’ actual water requirements [7]. This not only causes severe deep percolation in the field but also poses potential risks of secondary soil salinization—a major ecological hazard that degrades soil quality and reduces land productivity over time, threatening the sustainability of cropland [8]. These unscientific irrigation practices exert systematic adverse impacts on crop growth rhythms, stress tolerance, and final yield, while keeping water use efficiency persistently low. This further exacerbates water scarcity in arid regions and creates a vicious cycle between agricultural production and ecological protection. Therefore, there is an urgent need to explore the optimal irrigation quota for crop growth in extremely arid areas, and to achieve the full-cycle scientific management of irrigation water resources—shifting from “extensive experience-based irrigation” to “precision irrigation”—to meet the demands of refined water resource management and lay a solid foundation for sustainable agriculture.

Intelligent automatic irrigation is a key approach to achieving crop precision irrigation, and it plays a crucial role in alleviating regional water scarcity and advancing sustainable agricultural development [9,10]. By integrating advanced technologies with agricultural production, intelligent irrigation systems can optimize water allocation, reduce resource waste, and balance production efficiency with ecological protection—core objectives of sustainable agriculture. Accordingly, precision irrigation decision-making systems based on intelligent regulation and digital twin platforms, adapted to various irrigation methods, have garnered widespread attention from international scholars, experts, and water resource management authorities.

In terms of system architecture, a low-cost constant-humidity automatic irrigation system based on dynamic irrigation interval adjustment has been proposed. By dynamically adjusting irrigation intervals to maintain stable soil moisture levels, this system satisfies crop growth requirements while minimizing equipment costs, thereby exhibiting significant potential for large-scale application in resource-constrained arid regions and contributing to inclusive sustainable agriculture [11]. To further boost crop yields, researchers have developed an Internet of Things (IoT)-based automatic irrigation system. By integrating multi-source environmental and crop growth data, this system enables precise regulation of irrigation volumes, providing technical support for high-yield, water-saving crop cultivation that aligns with the sustainable production goals of crop cultivation [12].

At the control strategy level, fuzzy logic controllers have been incorporated into the intelligent decision-making processes of irrigation systems. These controllers effectively address complex nonlinear relationships in the irrigation environment, significantly enhancing the response accuracy and adaptability of such systems, which is critical for adapting to the volatile climatic conditions in arid regions and improving the stability of sustainable agricultural systems [13]. Subsequent field trials involved deploying an intelligent irrigation system in paddy fields in Taiwan, validating its feasibility in real-world agricultural settings. This application optimized irrigation regimes for rice paddies, improving both water use efficiency and planting profitability, while reducing the ecological footprint of paddy cultivation [14]. This integration not only reduces water waste but also minimizes nutrient runoff—a major source of agricultural non-point source pollution—thus promoting ecological sustainability. Moreover, an integrated water-fertilizer irrigation system combining ZigBee communication technology and STM32 processors has been proposed, advancing the precision and full automation of water and fertilizer management [14].

More recently, an intelligent irrigation system integrating IoT and fuzzy control technologies has been introduced. This system uses fuzzy inference to precisely match irrigation schedules to crop water requirements, while leveraging an IoT platform for remote monitoring and control, thereby improving the scientific rigor and timeliness of irrigation decisions and facilitating the efficient use of water resources in sustainable agricultural frameworks [15]. These technologies have yielded remarkable outcomes across different countries. Nations such as Israel and Australia have leveraged them to implement precision farmland irrigation, achieving substantial economic benefits while preserving limited water resources and maintaining ecological balance [16,17]. In Chinese regions such as Ningxia and Inner Mongolia, intelligent regulation systems and digital twin platforms have been adopted to enable precision irrigation in drip irrigation systems, supporting the sustainable development of cash crop cultivation in arid and semi-arid areas [18,19].

However, these applications exhibit certain shortcomings in terms of systematic integration, dynamic feedback mechanisms, and full-cycle management that limit their contribution to comprehensive agricultural sustainability. Furthermore, their adaptability to extremely arid areas—where ecological fragility and resource scarcity are more pronounced—has not been scientifically validated. Meanwhile, irrigation based on such systems has been shown to save water, increase crop yields, and improve crop water use efficiency compared to traditional irrigation, thus achieving the goal of water conservation and efficiency gains. However, no systematic exploration of these impacts on the overall sustainability of agricultural ecosystems (e.g., soil health, biodiversity, and resource circulation) has been conducted to date. Therefore, there is a need to systematically investigate how different irrigation quotas affect crop growth and water use efficiency under intelligent automatic irrigation systems to refine sustainable irrigation strategies.

The Shule River Irrigation District (SRID) is located at the western end of the Hexi Corridor in northwestern China, featuring scarce precipitation, an arid climate, and high evaporation rates [20]. As a typical arid agricultural zone, the SRID’s agricultural development is highly dependent on irrigation, making it a key area for exploring sustainable water-saving irrigation models. Driven by climate change and the expansion of cultivated land within the district, the contradiction between water supply and demand has been steadily intensifying, threatening the sustainability of local agriculture and the stability of the downstream ecological environment. Additionally, most farmers in the irrigation district rely on their own experience for farmland irrigation, leading to extensive practices, low irrigation water use efficiency, and significant water waste—further exacerbating the region’s ecological and resource pressures.

To improve water use efficiency, protect the ecological environment, and realize the transformation of irrigation management from “extensive experience-based practices” to “precision irrigation”, the SRID has developed a full-cycle intelligent automatic irrigation system, capitalizing on the opportunities presented by the modernization and digital twin irrigation district construction initiatives. However, the applicability of this system in the context of the SRID’s unique arid conditions, along with the variation characteristics of crop growth and ecological impacts under different irrigation quotas set by the system, has yet to be verified. Against this backdrop, this study selects sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.)—an important cash crop in the Shule River basin, valued for its drought and saline–alkaline tolerance and accounting for approximately 23% of the planted area—as the test crop. It explores the variation patterns of sunflower leaf area index (LAI), dry matter accumulation, yield, and irrigation water productivity under different irrigation quotas regulated by the full-cycle intelligent automatic irrigation system. On this basis, the optimal irrigation scheme for sunflowers is determined, which not only improves production efficiency but also minimizes ecological impacts. This research provides an applicable technical paradigm for efficient and sustainable sunflower irrigation in the arid regions of Northwest China, contributing to the broader goal of balancing agricultural development with ecological protection and resource conservation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Experimental Area

The sunflower irrigation experiment was conducted from April to August in 2024 and 2025 at the Nanganqu Demonstration Area of the SRID. Located at the western end of the Hexi Corridor, this region has a typical inland arid climate, with an average annual temperature of 8.8 °C, an annual precipitation of only 53.6 mm, and annual evaporation rates of up to 2653.2 mm [21]. The experimental field soil is predominantly sandy loam, with an average field capacity (fc) of 0.31 cm3·cm−3 and a pH value of 8.2. The planting pattern adopted was “one film with 4 rows and 2 drip tapes”, with a plant spacing of 30 cm × 40 cm. Under-film drip irrigation was employed, featuring a dripper flow rate of 2 L·h−1 and a dripper spacing of 30 cm. Each experimental plot measured 10 m in length, 1.8 m in width, and 18 m2 in area. Prior to sunflower sowing, 300 kg·hm−2 of compound fertilizer was applied. In the budding stage, 120 kg·hm−2 of urea (with a nitrogen content of 46%), 60 kg·hm−2 of monoammonium phosphate, and 30 kg·hm−2 of potassium nitrate were top dressed. In the flowering stage, additional topdressing was conducted with 135 kg·hm−2 of urea, 75 kg·hm−2 of potassium nitrate, and 120 kg·hm−2 of water-soluble fertilizer.

2.2. Full-Cycle Intelligent Automatic Irrigation System

Constructed on a digital twin platform, this intelligent irrigation system integrates two core components: a field automatic irrigation subsystem and a measurement-control sluice subsystem. The field subsystem encompasses four key functions: remote valve regulation, automatic fertilization, pump station operation management, and real-time microclimate monitoring. It triggers irrigation when soil moisture monitored via pre-embedded soil moisture sensors drops below the present threshold, where the system automatically triggers irrigation procedures and activates the pump station. The sluice subsystem dynamically adjusts gate apertures in response to water level fluctuations induced by downstream water intake. It increases water discharge to offset intake-related losses until the channel water level reaches a stable state. Channel water levels are tracked using pre-installed water level gauges, with both soil moisture and water level parameters sampled hourly for continuous system optimization.

2.3. Experimental Design

To validate the performance of the full-cycle intelligent automatic irrigation system, a field experiment was carried out using sunflower as the representative crop. The experiment design included 4 treatments with 3 replications per treatment: low-quota intelligent irrigation (T1), medium-quota intelligent irrigation (T2), high-quota intelligent irrigation (T3), and conventional farmer-managed irrigation (CK). For the intelligent irrigation treatments (T1–T3), the upper thresholds of soil moisture were set at 87%, 89%, and 91% of the field capacity (FC), respectively, with a unified lower threshold of 70% FC across all three groups. In contrast, the irrigation quota and scheduling of the CK treatment were determined based on the average irrigation practices locally within the study irrigation district. Detailed soil moisture control parameters for each treatment are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Soil moisture parameters under different irrigation treatments.

2.4. Data Observation

2.4.1. Leaf Area Index (LAI)

The LAI was determined via the length-width coefficient method [22]. For non-destructive sampling, 3 representative sunflower plants with consistent growth vigor were selected per experimental plot. Leaf length and width were measured for these plants, and the LAI was subsequently computed using the corresponding formula;

where LAI is the leaf area index (m2·m−2); ai is the leaf length (m); bi is the leaf width (m); Pd is the sunflower plant density (plants·m−2); K is the shape coefficient (0.75).

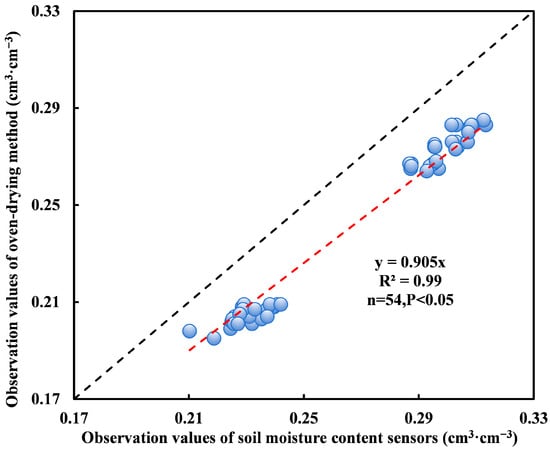

2.4.2. Soil Moisture Content

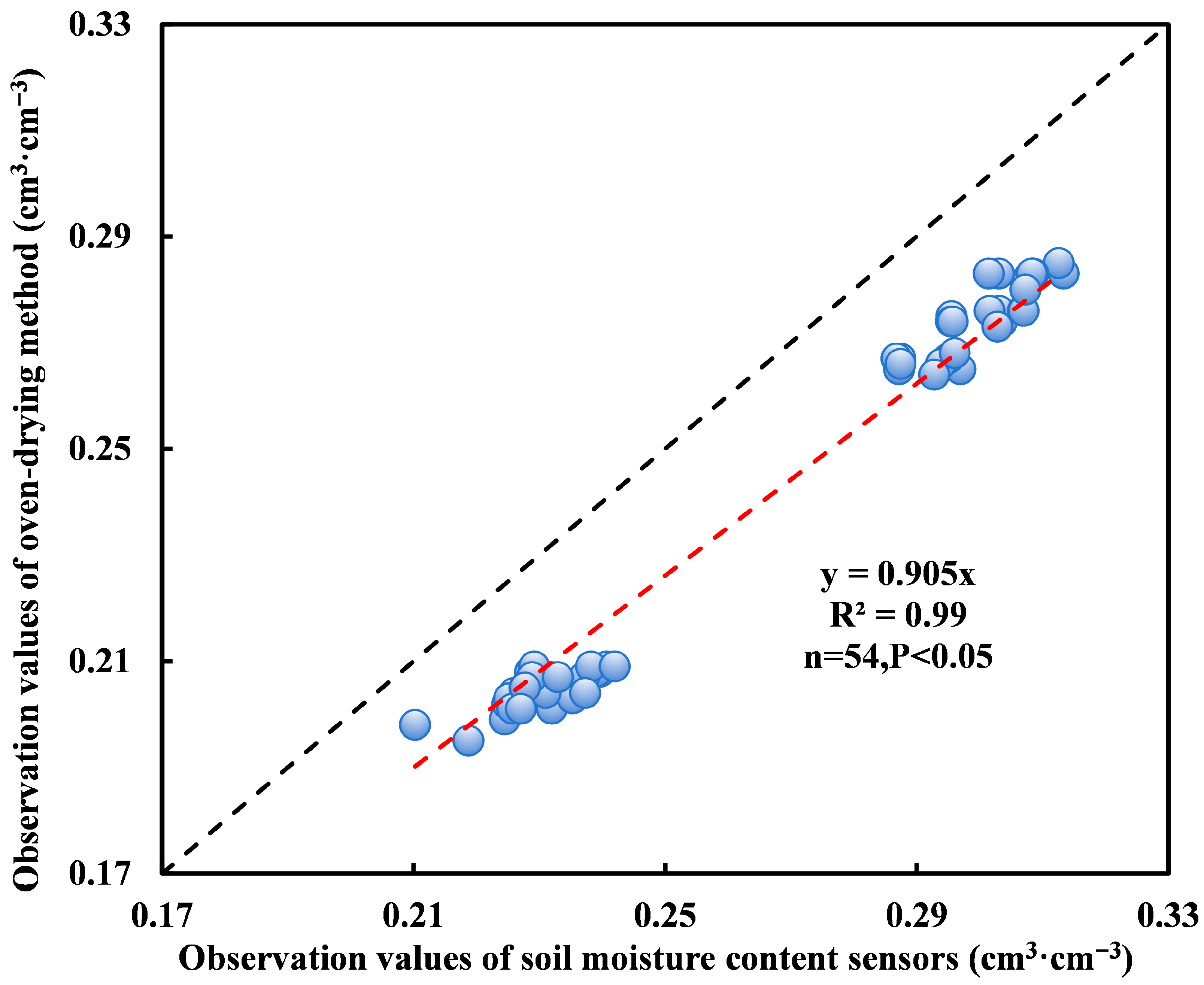

Soil moisture content was quantified using two complementary approaches, i.e., the oven-drying method or soil moisture sensor monitoring. The oven-drying method yields high-precision results but is inherently time-consuming and labor-intensive, making it unsuitable for high-frequency daily measurements. In contrast, sensor-based monitoring offers the advantages of efficiency and labor savings, albeit with potential minor accuracy deviations. In this study, soil moisture sensors were deployed for real-time continuous monitoring, while periodic soil samples were collected and analyzed via the oven-drying method to establish a calibration correlation between the two methods. Statistical analysis confirmed a significant linear relationship with sensor-derived and oven-drying measurements, with sensor-derived sensor readings averaging 9.5% lower results than the oven-drying measurements (Figure 1). The raw sensor data were then calibrated using the fitted linear equation to ensure data accuracy for subsequent analyses.

Figure 1.

The correlation between the soil moisture content observed through the drying method and that observed using sensors.

2.4.3. Dry Matter and Yield

For dry matter weight determination, 3 sunflower plants with moderate and uniform growth vigor were randomly selected from each experimental plot. The collected plant samples were first subjected to deactivation treatment at 120 °C for 1 h to halt enzymatic activity, then transferred to a constant-temperature drying oven set at 60 °C and dried to a constant weight. At the end of the growing season, 5 sunflower plants of moderate growth vigor were harvested from each plot to measure crop yield parameters.

2.4.4. Irrigation Water Use Efficiency (IWUE)

IWUE was defined as the economic yield produced per unit volume of irrigation water applied [23], and its calculation followed the formula provided below.

where IWUE is the sunflower irrigation water use efficiency (kg·m−3); Y is the sunflower yield (kg·hm−2); and IR is the total irrigation water during the whole growth period of sunflowers (m3·hm−2).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

A two-stage statistical analysis was implemented to assess the significance of differences among treatment means. In the first stage, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted at a significance level of p < 0.05, with the objective of testing the null hypothesis that the means of all treatment groups are equal. When the ANOVA results indicated a statistically significant effect, the analysis advanced to the second stage. In the second stage, Fisher’s protected least significant difference (LSD) test was applied to pinpoint specific pairwise differences among the treatment means. The LSD value was computed using the following formula:

where tα(dfe) is the critical value from Student’s t-distribution at the chosen significance level (α = 0.05), with degrees of freedom associated with the error mean square (MSE), and n is the number of replicates per treatment. For each pair of treatments, the absolute difference between their means was compared against the LSD value. If the difference exceeded the LSD, the two treatments were considered significantly different at p < 0.05.

To visualize the results of pairwise comparisons, the treatment means were first ranked in descending order. The largest mean was assigned the letter “a” and then compared sequentially with each subsequent (smaller) mean. Any mean exhibiting no significant difference from the largest mean was also labeled “a”; the first mean that differed significantly was designated “b”. Next, the mean labeled “b” was compared upward against all larger means previously marked “a”. If a larger “a”-labeled mean showed no significant difference from this “b” mean, a secondary “b” was appended to its existing label. This upward comparison was repeated until a significant difference was detected. Subsequently, the largest mean currently bearing the letter “b” was selected as the new reference benchmark, and a downward comparison was performed against all remaining unlabeled means. Means with no significant difference from this reference were assigned “b”, while the first significantly different mean was labeled “c”. This alternating upward–downward comparison protocol was repeated iteratively until the smallest mean was assigned a label and all pairwise comparisons were completed.

3. Results

3.1. Changes in Sunflower Leaf Area Index Under Different Irrigation Conditions

The dynamics of sunflower LAI across distinction growth stages under varying irrigation quotas are shown in Table 2. For both 2024 and 2025, under the same irrigation quota regime, the LAI exhibited a consistent increasing trend from the seedling stage to flowering stage. Marked discrepancies in LAI were observed among irrigation treatments during the same growth period, with treatment-specific patterns varying by developmental stage. In the seedling stage in 2024 and 2025, the T2 treatment yielded the highest LAI values, followed by CK (conventional farmer-managed irrigation) and T3 treatments, while T1 treatment had the lowest LAI. Notably, no statistically significant difference in LAI was detected among all the treatments in this stage. In 2024, compared with the CK treatment, T2 treatment increased LAI by 22.2%, whereas T3 and T1 treatments reduced LAI by 14.8% and 22.2%, respectively. In 2025, T2 enhanced LAI by 14.8% compared with the CK treatment, while T3 and T1 treatments reduced LAI by 14.8% and 18.5%, respectively. During the budding stage, T1 treatment achieved the highest LAI, followed by T2 and T3 treatments, with CK treatment showing the lowest values. No significant differences in LAI were found among T1, T2, and T3, yet all three intelligent irrigation treatments produced significantly higher LAI than the CK treatment did. In 2024, LAI values for T1, T2, and T3 were 37.7%, 32.1%, and 15.1% higher than those for CK, respectively. In 2025, compared with CK, the LAI of T1, T2, and T3 increased by 37.7%, 32.1%, and 17.0%, respectively. In the flowering stage in 2024, T3 treatment had the highest LAI, followed by T1 and T2 treatments, with CK treatment again recording the lowest values. Similar to the budding stage, LAI did not differ significantly among T1–T3, but all three treatments had a significantly higher LAI than CK. Relative to CK treatment, T1, T2, and T3 elevated LAI by 14.4%, 14.4%, and 20.6%, respectively. In 2025, the flowering-stage LAI was highest for T1 treatment, followed by T3 and T2 treatments, with CK treatment remaining the lowest. No significant differences were observed among T1–T3, and all three treatments had a significantly higher LAI than CK. Specifically, T1, T2 and T3 treatments increased by 26.5%, 14.3%, and 19.4%, compared with CK, respectively. Interaction effect analysis revealed no significant interannual difference in sunflower LAI across all growth stages. Collectively, these results demonstrate that irrigation scheduling based on a full-cycle intelligent automatic irrigation platform with soil moisture content thresholds set as upper and lower control limits effectively promotes sunflower leaf area expansion, thereby potentially enhancing photosynthetic capacity and crop productivity.

Table 2.

Sunflower leaf area index across growth stages under different irrigation levels (m2·m−2).

3.2. Variation Law of Sunflower Dry Matter Weight Under Different Irrigation Conditions

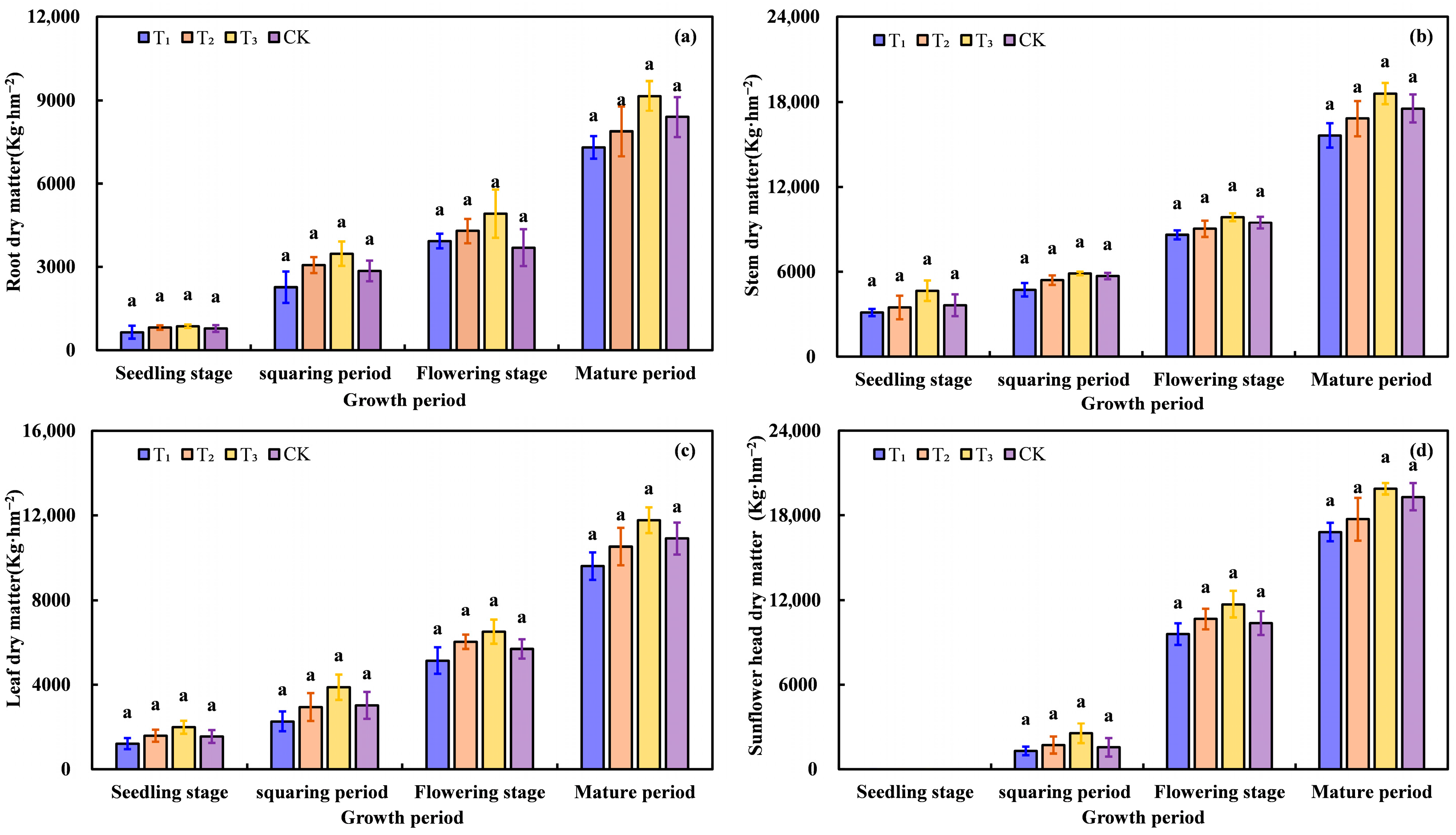

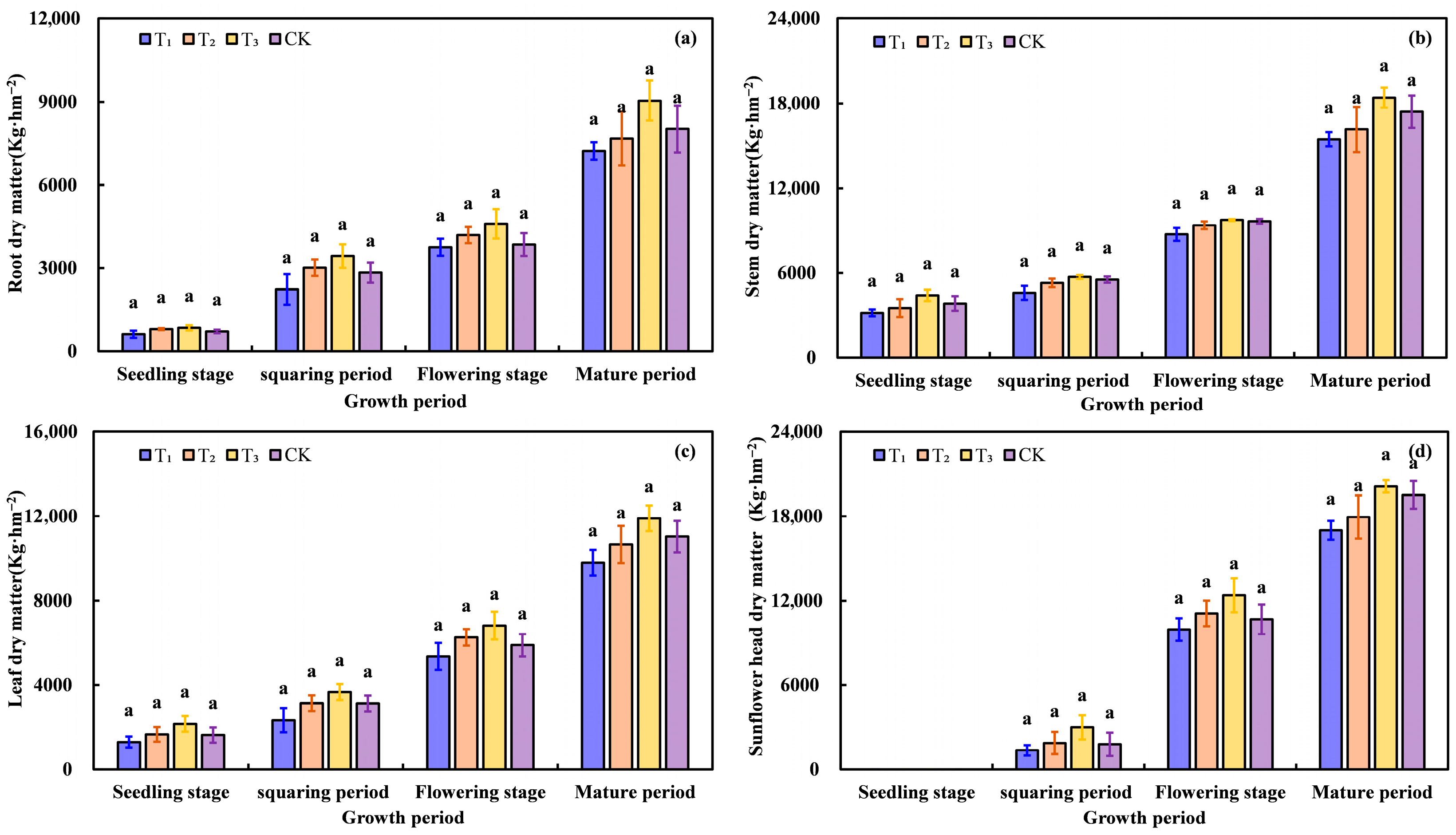

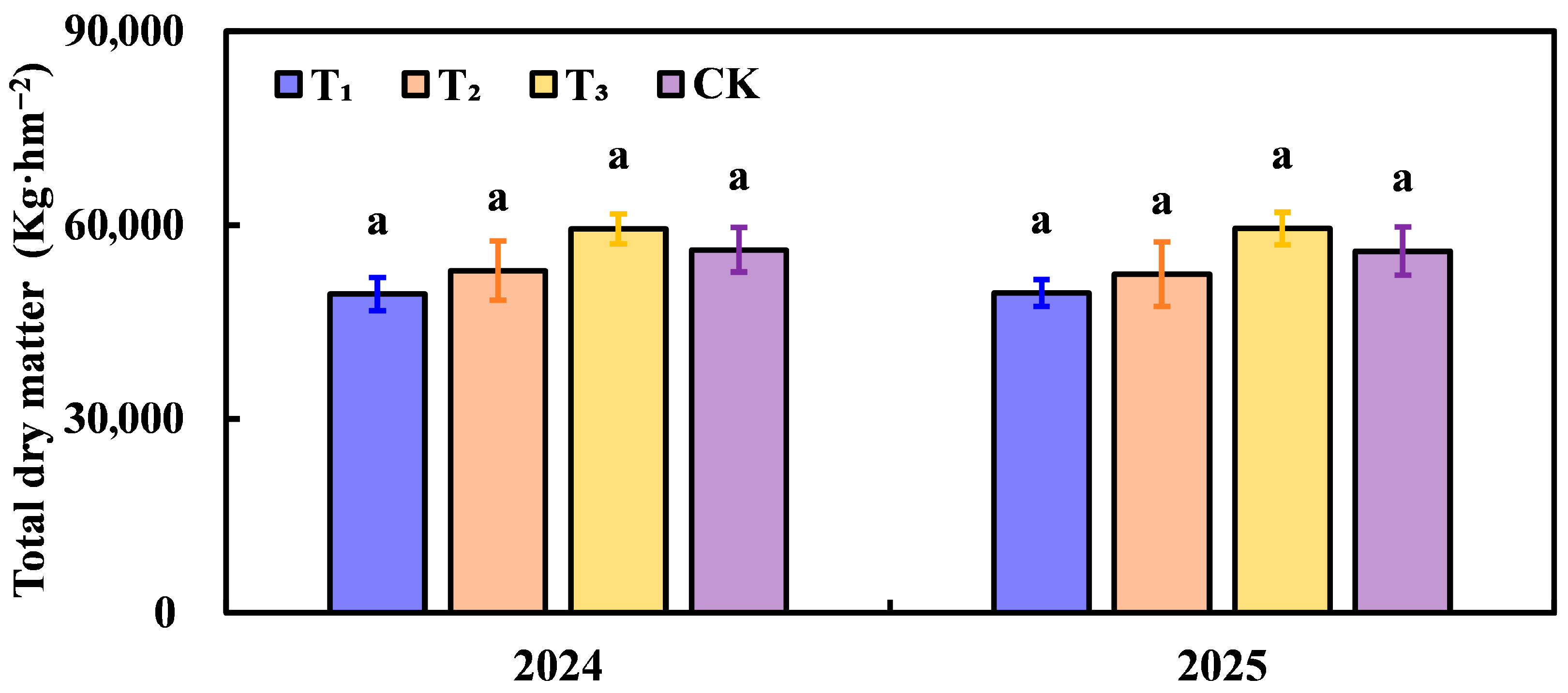

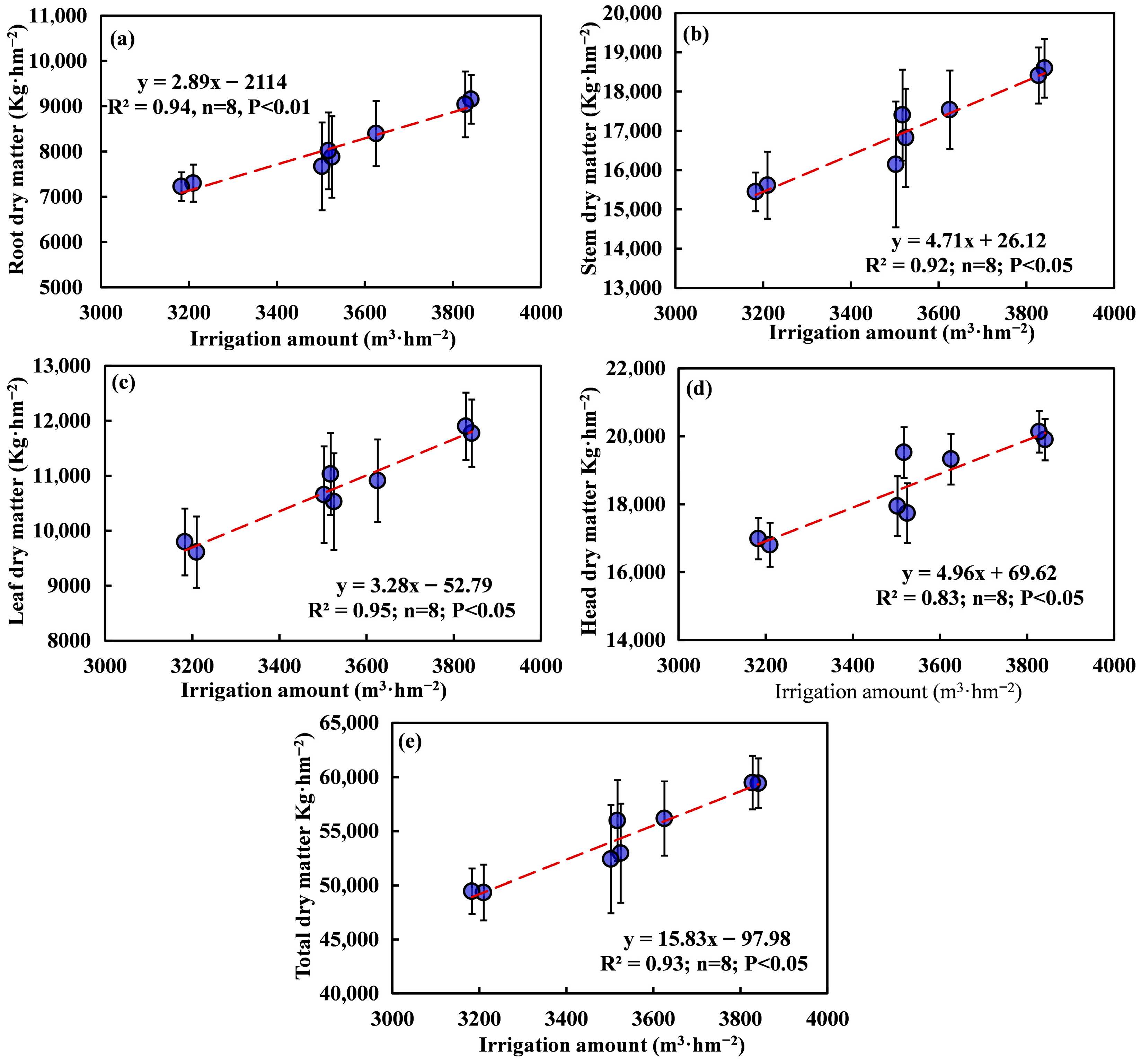

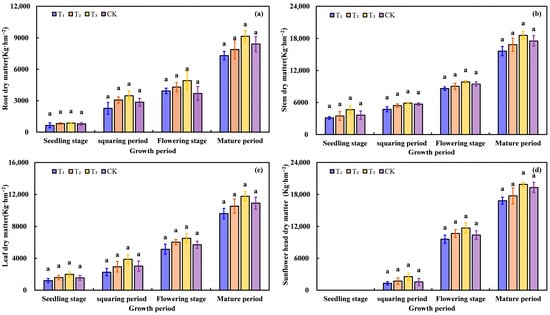

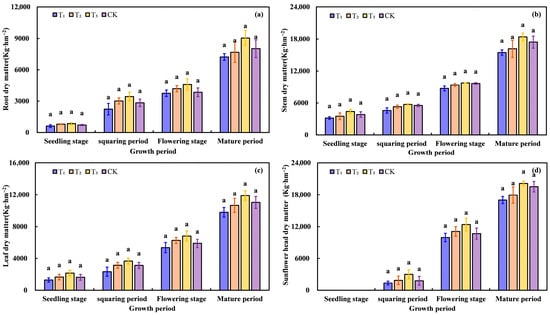

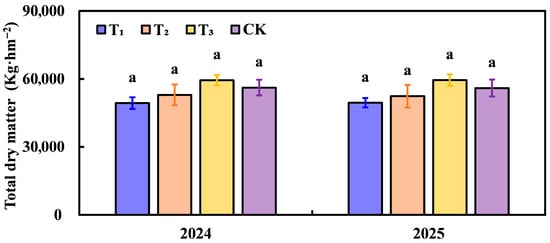

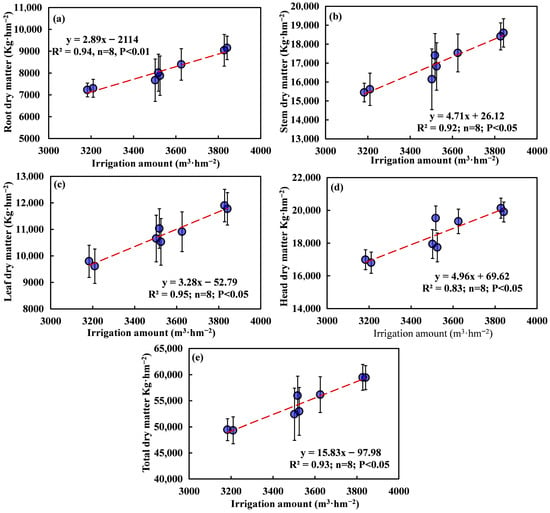

The temporal changes in dry matter weight (DMW) of various sunflower organs during the growth periods under distinct irrigation treatments are presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3. Across both 2024 and 2025 growing seasons, the DMW of all sunflower organs (roots, stems, leaves, and flower heads) exhibited a consistent increasing trend with the progression of growth stages, regardless of irrigation regime. No significant differences were observed for the DMW of all sunflower organs (roots, stems, leaves, and flower heads) among treatments at the same growth stage (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Numerically, during the seedling stage in both 2024 and 2025, the DMW of roots, stems, and leaves were maximized under the T3 treatment and minimized under the T1 treatment. Notably, the DMW of flower heads was negligible (zero) across all treatments in this developmental stage. In the budding stage and maturity stage over the two-year study period, the DMW of roots, stems, leaves, and flower heads consistently reached their peaks under the T3 treatment and their trough under the T1 treatment. A divergent pattern was observed in the flowering stage in 2024. While the DMW of stems, leaves, and flower heads were highest under the T3 treatment and lowest under the T1 treatment, the DMW of roots was maximized under the T3 treatment and minimized under the CK treatment. By contrast, in 2025, the DMWs of all four plant organs, i.e., root, stems, leaves, and flower heads, in the flowering stage were greatest under the T3 treatment and smallest under the T1 treatment. For the total DMW, no significant differences were observed among treatments. Numerically, the T3 treatment yielded the highest values in both 2024 and 2025, followed sequentially by the CK and T2 treatments, while the T1 treatment had the lowest values. Specifically, in 2024, the total DMW under the T1, T2, T3, and CK treatments were 49,330.5 kg·hm−2, 52,961.0 kg·hm−2, 59,418.9 kg·hm−2, and 56,164.1 kg·hm−2, respectively. The corresponding values in 2025 were 49,450.0 kg·hm−2, 52,410.6 kg·hm−2, 59,481.2 kg·hm−2, and 55,969.9 kg·hm−2, respectively (Figure 4). Statistical analysis indicated that across the entire growth period, the DMW of all sunflower organs exhibited a significant increasing trend with the rise in irrigation water volume (Figure 5).

Figure 2.

Sunflower organ dry matter mass in 2024. (a) Root; (b) stem; (c) leaf; (d) flower head. The letters denote the significance of differences among treatments at the p = 0.05 probability level.

Figure 3.

Sunflower organ dry matter mass in 2025. (a) Root; (b) stem; (c) leaf; (d) flower head. The letters denote the significance of the differences among treatments at the p = 0.05 probability level.

Figure 4.

Sunflower total dry matter mass in 2024 and 2025. The letters denote the significance of the differences among treatments at the p = 0.05 probability level.

Figure 5.

Scatter of irrigation amount and dry matter mass of sunflower. (a) Root dry matter mass; (b) stem dry matter mass; (c) leaf dry matter mass; (d) head dry matter mass; (e) total dry matter mass.

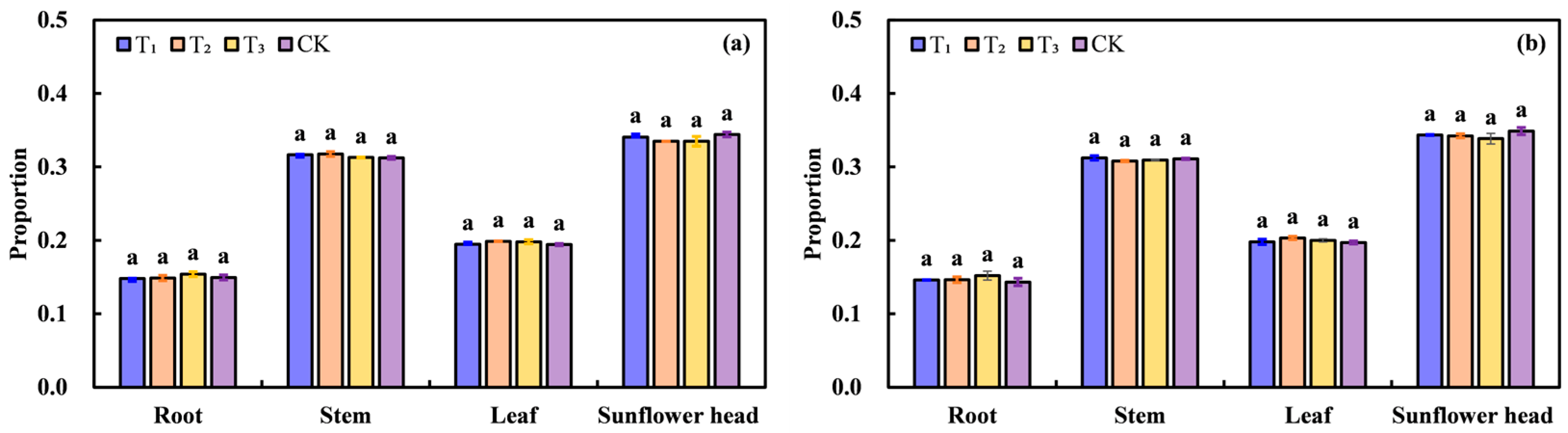

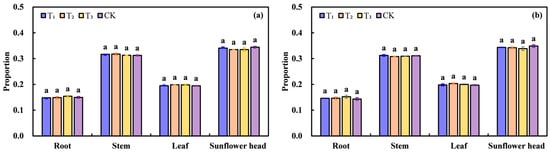

The proportion distribution of the DMW across sunflower organs relative to the total DMW under different irrigation regimes is shown in Figure 6. No significant differences were observed among treatments (Figure 6). For the root DMW, a consistent value of 0.15 was recorded across all T1, T2, T3, and CK treatments in 2024. In 2025, this proportion remained at 0.15 for T1, T2, and T3 treatments, but slightly decreased to 0.14 for the CK treatment. The stem DMW proportion, for both T1 and T2 treatments, shared an identical value of 0.32 in 2024, whereas both T3 and CK treatments reached 0.31 in the same year. By contrast, all four treatments converged to a uniform proportion of 0.31 in 2025. For the leaf DMW proportion, both T1 and CK treatments exhibited a proportion of 0.19 in 2024, while both T2 and T3 treatments showed a marginally higher value of 0.20. In 2025, the proportion value stabilized at 0.20 across all treatments. As for the proportion of flower head DMW, both T1 and CK treatments had a proportion of 0.34 in 2024, compared with 0.33 for T2 and T3 treatments. In 2025, the proportion was 0.34 for T1, T2 and T3 treatments, whereas the CK treatment showed a slightly elevated value of 0.35. Across the two-year experimental period, the average DMW proportions were consistent across all treatments: 0.15 for roots, 0.32 for stems, 0.20 for leaves, and 0.34 for flower heads.

Figure 6.

Proportion of dry matter mass of each organ of sunflower to the total dry matter mass in 2024 (a) and 2025 (b). The letters denote the significance of the differences among treatments at the p = 0.05 probability level.

3.3. Sunflower Yield, Harvest Index, and Irrigation Water Productivity Under Different Irrigation Treatments

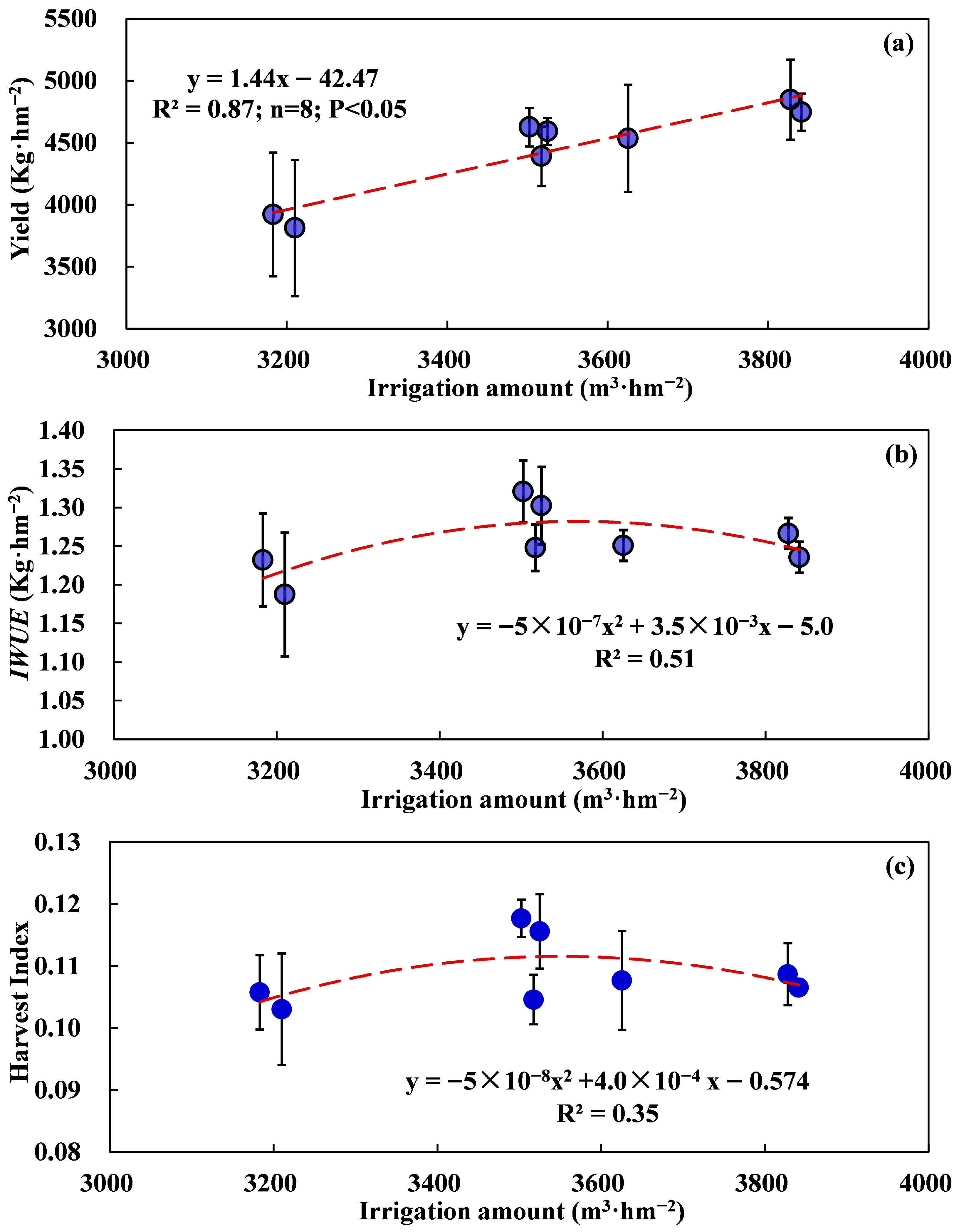

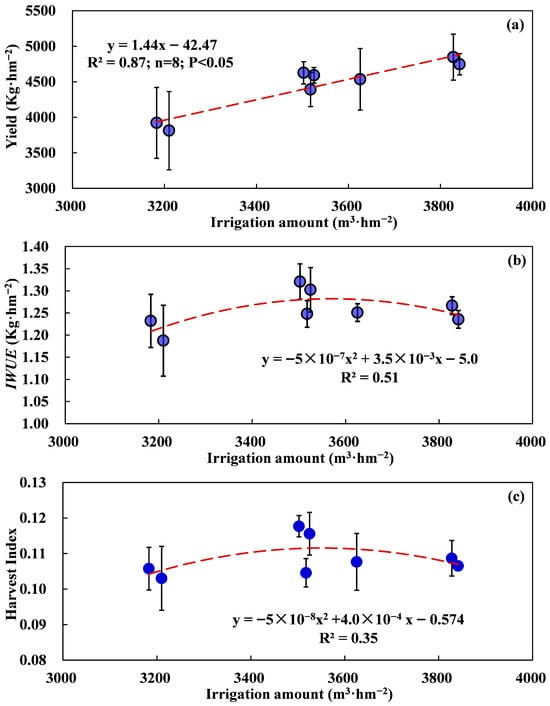

The sunflower yield, harvest index (HI), and irrigation water use efficiency (IWUE) under different irrigation treatments are summarized in Table 3, with the magnitude of treatment effects varying across these three parameters. For sunflower yield, the T3 treatment consistently produced the highest values in both 2024 and 2025, followed in descending order by T2 and CK treatments, while T1 treatment yielded the lowest values across the two-year study period. Compared to the CK treatment in 2024, T2 and T3 treatments increased the yield by 1.2% and 4.7%, respectively, whereas T1 treatment induced a 15.9% yield reduction. In 2025, yield was enhanced by 5.4% and 10.4% under T2 and T3 compared to CK, while T1 treatment led to a 10.7% yield decline. Regarding the harvest index (HI), the treatment effects exhibited distinct inter-annual variation. In 2024, the HI was maximized under T2, followed by CK and T3, with T1 recording the lowest value. Relative to CK, HI decreased by 4.6% and 0.9% under T1 and T3, respectively, but elevated by 7.4% under T2. In contrast, the 2025 HI ranking was led by T2, followed by T3 and T1, with CK showing the lowest value. Compared with CK, the HI increased by 1.0%, 12.4%, and 3.8% under T1, T2, and T3 treatments, respectively. For irrigation water use efficiency (IWUE), treatment-specific patterns exhibited distinct inter-annual variability. In 2024, the IWUE was maximized under T2, followed sequentially by CK and T3, with T1 yielding the lowest values. Compared to the CK treatment, T1 and T3 reduced IWUE by 4.8% and 0.8%, respectively, whereas T2 enhanced IWUE by 4.0%. In 2025, the highest IWUE was still recorded under T2, but the subsequent ranking shifted to T3 and then CK, with T1 remaining the lowest. Compared with CK, T2 and T3 increased the IWUE by 5.6% and 1.6%, respectively, while T1 caused a marginal 1.6% reduction in IWUE. Statistical analysis indicated that sunflower yield exhibited a positive linear response to increasing irrigation water application. In contrast, both IWUE and HI followed a unimodal trend, rising initially and declining after reaching a distinct optimal threshold (Figure 7). A comprehensive comparative analysis of yield, HI, and IWUE under the T1, T2, T3, and CK treatments identified T2—characterized by an irrigation lower limit of 70% field capacity and an upper limit of 89% field capacity—as the optimal irrigation regime. This regime effectively balances the dual goals of water conservation and production efficiency, thereby achieving dual objectives of resource savings and yield improvement.

Table 3.

Effects of irrigation levels on sunflower yield, harvest index, and water productivity.

Figure 7.

Relationship between irrigation water and sunflower yield, water productivity, and harvest index. (a) Yield; (b) water productivity; (c) harvest index.

4. Discussion

4.1. Response Characteristics of Sunflower Growth and Water Use Under Intelligent Irrigation

Sunflower is a major economic crop in China, and its robust drought and salt tolerance, deep root system, and high water use efficiency render it well-suited for widespread cultivation in the arid northwest regions [24,25]. As the primary photosynthetic organs of sunflower, leaves play a pivotal role in dry matter accumulation and yield formation, with leaf area and leaf area index (LAI) being core metrics governing these physiological processes. Liu et al. [26] reported that sunflower LAI exhibited a progressive upward trend from the seedling stage to the flowering stage, while Khaleghi et al. [27] documented a similar LAI increase from the sowing to the middle-growth stage. The findings of the present study were consistent with these prior observations. However, this study identified no significant differences in LAI among the three full-cycle intelligent irrigation treatments during the seedling-to-flowering period, a pattern presumably attributable to their shared irrigation upper limit thresholds. In the seedling stage, no significant LAI discrepancies were detected between the intelligent irrigation regimes and conventional farmer-managed irrigation practices. This can be explained by the uniform soil moisture conditions established across all treatments via pre-sowing irrigation for salt leaching and adequate post-emergence establishment watering. In contrast, during the budding and flowering stages—critical periods for vegetative and reproductive growth—the LAI values under the three intelligent irrigation treatments were significantly higher than those under farmer practice. This divergence arose because the intelligent irrigation system facilitated real-time, accurate soil moisture monitoring and precision irrigation scheduling, whereas the longer irrigation intervals inherent to conventional farmer practices induced mild drought stress during these critical stages. In T1, soil moisture was maintained at 19.5–26.5%; in T2, at 20.1–27.6%; and in T3, at 19.9–28.5%. In CK, due to irrigation frequency, the lower limit varied from 12.57% to 20.0%, while the upper limit remained constant at 31%.

Roots, stems, and leaves represent the primary vegetative organs of sunflower, whereas the capitulum serves as its key reproductive organ. Variations in irrigation levels exert a distinct influence on dry matter accumulation across these organs. Prior studies have demonstrated that dry matter accumulation in roots, stems, leaves, and the capitula generally increases with rising irrigation volumes [28,29]. Similar trends were reported by Khaleghi, Hassanpour, Karandish, and Shahnazari [27] and Jing et al. [30]. Consistent with these findings, our statistical analysis showed that by the end of the growth period, the dry matter of all organs exhibited a positive correlation with increasing irrigation amount (Figure 4). Among the intelligent irrigation treatments, dry matter accumulation in all organs exhibited a consistent upward trend with higher irrigation amounts in every growth stage. In contrast, dry matter accumulation patterns under conventional farmer-managed irrigation practices were less stable relative to the intelligent treatments. This inconsistency is presumably attributable to the lack of precision in irrigation timing and dosage inherent to traditional farming operations.

Irrigation is a fundamental practice for sustaining high and stable crop yields, as it primarily modulates soil moisture regimes—a key determinant of crop productivity [31,32]. Timely, precision irrigation is therefore crucial for simultaneously boosting both crop yields and improving irrigation water productivity (IWUE). Numerous studies conducted in the arid northwestern regions of China have demonstrated that crop yields generally exhibit a positive response to increased irrigation inputs, whereas IWUE follows a unimodal trend of an initial increase followed by a decline once a threshold irrigation level is exceeded [33,34,35]. Our statistical analyses yielded consistent findings: sunflower yields rose progressively with increasing irrigation amounts, while IWUE increased initially and then decreased after peaking at an optimum irrigation level. This pattern confirms that excessive irrigation application leads to a reduction in the IWUE [26].

4.2. Application Potential and Scaling Challenge

The sensing-decision-execution framework integrated into the digital twin platform demonstrates substantial transformative potential for advancing water management practices in arid irrigation districts, extending well beyond the Shule River Basin. As a core technological paradigm, this system is highly replicable and adaptable to other regions plagued by water scarcity and constrained by inefficient conventional irrigation practices. Its proven efficacy in reconciling water conservation goals with yield stability offers a scientifically validated blueprint for deployment in newly upgraded irrigation districts across northwest China, as well as analogous arid regions globally. That said, scaling this technology from successful pilot demonstrations to large-scale adoption entails addressing multiple interconnected challenges. On the technological front, ensuring seamless interoperability among heterogeneous equipment from diverse manufacturers and maintaining resilient communication networks in remote rural settings are crucial prerequisites for reliable system operation. Agronomically, the establishment of comprehensive irrigation threshold databases tailored to diverse crops species and soil types is indispensable to broaden the framework’s applicability across varied production contexts. Institutionally, transitioning from farmer-centric, experience-based irrigation practices to centralized, automated systems demands fundamental reforms in water governance mechanisms and stakeholder engagement strategies. Equally vital is the provision of systematic training and ongoing technical support for end users, which is key to fostering trust in the technology and enhancing on-site operational capacity. Accordingly, future research endeavors should prioritize exploring synergistic interactions between intelligent irrigation and complementary agronomic practices—including integrated water-fertilizer management and conservation agriculture—with the aim of developing holistic cropping system management packages that simultaneously maximize resource use efficiency and farm-level profitability.

The core value proposition of intelligent irrigation systems resides in delivering the triple benefits of water conservation, yield improvement, and cost reduction via precision management and automated control [36]. Such systems can markedly elevate agricultural resource use, generally achieving water savings of 20–30% and crop yield increases of 5–15% [37]. The associated capital investment can be recouped within a few years via savings in water, fertilizer, and labor expenditures, directly boosting farmers’ net incomes [38]. As technological advancements and innovative service models continue to emerge, the scalability and adoption feasibility of these systems have improved significantly. Modular hardware designs and customizable solutions can be tailored to match diverse farm size and budget constraints, thereby lowering initial deployment costs [39]. Concurrently, cooperative-led infrastructure construction and enterprise-provided “technology trusteeship” services effectively mitigate end-users’ concerns regarding technical complexity and post-implementation maintenance. That said, widespread adoption still confronts notable hurdles, including high upfront costs, inadequate network and power infrastructure in remote rural areas, and the time required for farmers to comprehend and embrace this novel technology. These barriers are not insurmountable. However, targeted policy subsidies and preferential financing schemes can alleviate the financial burden on farmers; ongoing rural infrastructure upgrades provide essential support for system deployment; and on-site demonstration projects coupled with customized technical training can enhance farmers’ awareness and confidence in the technology. In summary, the promotion of intelligent irrigation systems necessitates coordinated advances in technological innovation, economic incentives, and social support systems. The outlook for their application remains promising, as these systems are increasingly serving as a pivotal driver of agricultural modernization, a catalyst for farmer income growth, and a cornerstone for advancing sustainable agricultural development in water-scarce regions.

While the proposed intelligent irrigation system demonstrates considerable potential for application in arid regions, this study is subject to several limitations that warrant acknowledgment. First, the experimental validation was carried out over merely two growing seasons, with trials restricted to a single soil type and crop species. Variations in soil texture and depths are known to alter field water capacities [40], which in turn dictates optimal irrigation quotas for crops. Given that suitable irrigation upper and lower limits vary substantially across different crop species [41]. Further verification is necessary to extrapolate the identified optimal soil moisture thresholds (70–89% FC) to other soil textures or crops with divergent water sensitivity profiles. Second, system performance is inherently contingent on the accuracy and spatial representativeness of the deployed soil moisture sensor network. The number of sensors embedded in the soil profile and their proximity to the crop root zone exert a significant influence on the precise quantification of soil moisture content within the crop root layer [42]. In fields characterized by high spatial heterogeneity, a limited sensor density may fail to capture the full spectrum of soil moisture variability, potentially resulting in under- or over-irrigation in unsampled areas. Moreover, the current iteration of the system relies exclusively on soil moisture data as the input parameter for irrigation decision making. It does not yet integrate real-time crop evapotranspiration demands, short-term precipitation forecasts, or plant-based water stress indicators, all variables that could further optimize irrigation-triggering conditions and enhance the system’s adaptive precision.

5. Conclusions

To assess the applicability of an intelligent automated irrigation system in the Shule River Irrigation District—an area characterized by scarce water resources and high dependence on irrigation for agricultural production—and to explore its potential in advancing sustainable agricultural development, this study conducted field irrigation experiments using sunflower as a representative crop. Systematic investigations were carried out to characterize the variations in leaf area index (LAI), dry matter accumulation (DMW), yield, harvest index (HI), and irrigation water productivity (IWUE) across gradient irrigation quotas, with a focus on balancing production efficiency and water resource sustainability. The main conclusions are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- Across all irrigation quota treatments, sunflower LAI exhibited a progressive increasing trend from the seedling stage to the flowering stage, which is closely linked to the crop’s photosynthetic capacity and subsequent dry matter accumulation—key determinants of both yield formation and resource utilization efficiency. Marked discrepancies in LAI were observed among irrigation treatments during the same growth period, with treatment-specific patterns varying by developmental stage. These differences highlight the significant impact of irrigation regime optimization on crop physiological growth, laying a foundation for formulating water-saving and high-yield cultivation strategies that align with the region’s sustainable water use goals.

- (2)

- Concurrently, the DMW in all plant organs showed a consistent upward trajectory as the growth period advanced with elevated irrigation. There is a positive statistical relationship between the amount of water and DMW, but there is no statistical difference for DMW among treatments. This pattern not only enhances yield potential but also improves resource use efficiency, reducing unnecessary water consumption for vegetative growth and contributing to the sustainability of the irrigation system.

- (3)

- Sunflower yield exhibited a positive response to increasing irrigation water amounts within a reasonable range, whereas both IWUE and HI followed a unimodal pattern of an initial increase followed by a decline after reaching optimal thresholds. This finding emphasizes the inherent trade-off between yield and water use efficiency, underscoring the importance of avoiding over-irrigation—which wastes scarce water resources and may exacerbate soil salinization, a major threat to long-term agricultural sustainability in arid irrigation districts. The optimal irrigation regime was determined as maintaining soil moisture between a lower limit of 70% field capacity (FC) and an upper limit of 89% FC, which achieves a balance between high yield, efficient water use, and ecological stability.

- (4)

- Using soil moisture content as the core control parameter, the full-cycle intelligent automated irrigation system realized precision irrigation management throughout the entire sunflower growth cycle, delivering water only when and where the crop needs it. Compared with conventional farmer-managed irrigation practices which are characterized by subjective judgment and excessive water application, this system not only improves irrigation effectiveness but also significantly reduces water wastage, thereby mitigating the pressure on the Shule River’s limited water resources. By achieving the dual goals of water conservation and production efficiency improvement, the system provides a feasible technical solution for transitioning to sustainable, water-saving agriculture in arid and semi-arid irrigation districts, supporting the region’s long-term ecological security and agricultural resilience.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, Q.W. and H.W.; field observation and data, Q.W., P.Z. and J.W.; writing—review and editing, P.Z., X.W., Y.P. and J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Scientific research project of the Water Resources Utilization Center of the Shule River Basin in Gansu Province (SLH/KYXM-2025-01), the Project of Water Resources Science Experiment Research and Technology Promotion in Gansu Province (25GSLK077), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42330512).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the farmers for the planting and management of the crop, the editors, and the anonymous reviewers for their crucial comments, which improved the quality of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interest or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Tian, X.; Dong, J.; Jin, S.; He, H.; Yin, H.; Chen, X. Climate change impacts on regional agricultural irrigation water use in semi-arid environments. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 281, 108239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, L. Adapting agriculture to climate change via sustainable irrigation: Biophysical potentials and feedbacks. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 063008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Srivastava, A.; Khadke, L.; Chatterjee, U.; Elbeltagi, A. Global-scale water security and desertification management amidst climate change. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 58720–58744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkenmark, M. Growing water scarcity in agriculture: Future challenge to global water security. Philos. Trans. Ser. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2013, 371, 20120410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seleiman, M.; Al-Suhaibani, N.; Ali, N.; Akmal, M.; Alotaibi, M.; Refay, Y.; Dindaroglu, T.; Abdul-Wajid, H.; Battaglia, M. Drought Stress Impacts on Plants and Different Approaches to Alleviate Its Adverse Effects. Plants 2021, 10, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadirnezhad Shiade, S.R.; Fathi, A.; Ghasemkheili, F.; Amiri, E.; Pessarakli, M. Plants’ responses under drought stress conditions: Effects of strategic management approaches—A review. J. Plant Nutr. 2022, 46, 2198–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunita, S.; Harry, D. Emerging Science for Sustainable Water Resources Management: A Guide for Water Professionals and Practitioners in India; UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology: Lancaster, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Wu, J.; Qian, H. Regulation of secondary soil salinization in semi-arid regions: A simulation research in the Nanshantaizi area along the Silk Road, northwest China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Hussain, T.; Zahid, A. Smart Irrigation Technologies and Prospects for Enhancing Water Use Efficiency for Sustainable Agriculture. AgriEngineering 2025, 7, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhiar, I.A.; Yan, H.; Zhang, C.; Wang, G.; He, B.; Hao, B.; Han, Y.; Wang, B.; Bao, R.; Syed, T.N.; et al. A Review of Precision Irrigation Water-Saving Technology under Changing Climate for Enhancing Water Use Efficiency, Crop Yield, and Environmental Footprints. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.-C.; Lin, Y.-Z. A Low-Cost Constant-Moisture Automatic Irrigation System Using Dynamic Irrigation Interval Adjustment. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakhare, P.B.; Neduncheliyan, S.; Sonawane, G.S. Automatic Irrigation System Based on Internet of Things for Crop Yield Prediction. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Emerging Smart Computing and Informatics (ESCI), Pune, India, 12–14 March 2020; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 129–132. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.K.; Tariq, T.; Ahmer, M.F.; Sharma, G.; Bokoro, P.N.; Shongwe, T. Intelligent Control of Irrigation Systems Using Fuzzy Logic Controller. Energies 2022, 15, 7199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.-F.; Chen, C.-T.; Lin, G.-F. Practical application of an intelligent irrigation system to rice paddies in Taiwan. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 280, 108216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, Z.; Rezaeipanah, A. Intelligent and automatic irrigation system based on internet of things using fuzzy control technology. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Z.; Han, S.; Liu, J. Application Progress of Agricultural Internet of Things in Major Countries. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1087, 032013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F. Agriculture 4.0 as a way forward to sustainable agriculture in Australia. JSFA Rep. 2025, 5, 337–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, X.; Chen, R. Research on optimizing water resource management and improving crop yield using big data and artificial intelligence. Adv. Resour. Res. 2025, 5, 1025–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Xie, H. The evolution of data-driven precision irrigation technology: Frontier advances, core challenges, and intelligent development pathways. Geogr. Res. Bull. 2025, 4, 367–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Geng, Y.; Ma, J.; Zhao, H.; He, J.; Chen, J. Separating Climatic and Anthropogenic Drivers of Groundwater Change in an Arid Inland Basin: Insights from the Shule River Basin, Northwest China. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Luo, Q.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, C. Research on Optimal Operation of Reservoirs in Shule River Irrigation District Based on Dynamic Programming with Successive Approximation Method. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 693, 012004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.-h.; Yang, Y.-l.; Shao, X.-y.; Shi, T.-y.; Meng, T.-y.; Lu, Y.; Tao, Y.; Li, X.-y.; Ding, E.-h.; Chen, Y.-l.; et al. Higher leaf area through leaf width and lower leaf angle were the primary morphological traits for yield advantage of japonica/indica hybrids. J. Integr. Agric. 2020, 19, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Wahed, M.H.; Ali, E.A. Effect of irrigation systems, amounts of irrigation water and mulching on corn yield, water use efficiency and net profit. Agric. Water Manag. 2013, 120, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wu, Y.; Fan, Y.; Qi, P.; He, J.; Hou, Z.; Huang, Q.; Huang, G. How do integrated agronomic practices enhance sunflower productivity and stability in saline-alkali soils of arid regions? Evidence from China. Field Crops Res. 2025, 326, 109841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Tong, C.; Wang, J.; Zheng, H. Comparison of Water Utilization Patterns of Sunflowers and Maize at Different Fertility Stages along the Yellow River. Water 2024, 16, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Sun, L.; Zhu, X.; Deng, H.; Fan, Y.; Huang, Q.; Huang, G. Effects of different annual irrigation strategies on soil water, salt, nitrogen leaching, and sunflower growth in saline soils of arid regions. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 318, 109692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaleghi, M.; Hassanpour, F.; Karandish, F.; Shahnazari, A. Integrating partial root-zone drying and saline water irrigation to sustain sunflower production in freshwater-scarce regions. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 234, 106094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tianyu, W.; Zhenhua, W.; Qiang, W.; Jinzhu, Z.; Lishuang, Q.; Bihang, F.; Li, G. Coupling effects of water and nitrogen on photosynthetic characteristics, nitrogen uptake, and yield of sunflower under drip irrigation in an oasis. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2021, 14, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balazadeh, M.; Zamanian, M.; Golzardi, F.; Torkashvand, A. Effects of Limited Irrigation on Forage Yield, Nutritive Value and Water Use Efficiency of Persian Clover (Trifolium resupinatum) Compared to Berseem Clover (Trifolium alexandrinum). Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2021, 52, 1927–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, B.; Shah, F.; Xiao, E.; Coulter, J.A.; Wu, W. Sprinkler irrigation increases grain yield of sunflower without enhancing the risk of root lodging in a dry semi-humid region. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 239, 106270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Wu, L.; Cheng, M.; Fan, J.; Li, S.; Wang, H.; Qian, L. Review on Drip Irrigation: Impact on Crop Yield, Quality, and Water Productivity in China. Water 2023, 15, 1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Schütze, N. Assessing crop yield and water balance in crop rotation irrigation systems: Exploring sensitivity to soil hydraulic characteristics and initial moisture conditions in the North China Plain. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 300, 108897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Zhou, Y. An Evaluation of Food Security and Grain Production Trends in the Arid Region of Northwest China (2000–2035). Agriculture 2025, 15, 1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Deng, M.; Han, Y.; Huang, H.; Yang, T. Spatiotemporal variation of irrigation water requirements for grain crops under climate change in Northwest China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 45711–45724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Su, D. Alfalfa Water Use and Yield under Different Sprinkler Irrigation Regimes in North Arid Regions of China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvam, D.C.; Devarajan, Y. Investigation of Emerging Technologies in Agriculture: An In-depth Look at Smart Farming, Nano-agriculture, AI, and Big Data. J. Biosyst. Eng. 2025, 50, 170–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askaraliev, B.; Musabaeva, K.; Koshmatov, B.; Omurzakov, K.; Dzhakshylykova, Z. Development of modern irrigation systems for improving efficiency, reducing water consumption and increasing yields. Mach. Energetics 2024, 15, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molden, D.; Oweis, T.Y.; Steduto, P. Pathways for increasing agricultural water productivity. In Water for Food Water for Life; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Matar, M.A.I.; Radi, M.; Alzebda, S.A. Advancements in smart modular farming systems for sustainable agriculture. In AI in Business: Opportunities and Limitations; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; Volume 516, pp. 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Evett, S.R.; Stone, K.C.; Schwartz, R.C.; O’Shaughnessy, S.A.; Colaizzi, P.D.; Anderson, S.K.; Anderson, D.J. Resolving discrepancies between laboratory-determined field capacity values and field water content observations: Implications for irrigation management. Irrig. Sci. 2019, 37, 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Ma, J.; Hao, X.; Li, Q. Limitations of Water Resources to Crop Water Requirement in the Irrigation Districts along the Lower Reach of the Yellow River in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbesi, W.E.K.; Sam-Amoah, L.K.; Darko, R.O.; Kumi, F.; Boafo, G. Numerical Models for Predicting Water Flow Characteristics and Optimising a Subsurface Self-Regulating, Low-Energy, Clay-Based Irrigation (SLECI) System in Sandy Loam Soil. Water 2025, 17, 2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.