Abstract

The global energy transition to renewable energy sources requires a rigorous assessment of the environmental impacts of all system components, including power electronics converters (PECs), which play a critical role in adapting generated energy to grid and load requirements. This paper presents a comprehensive comparative assessment of conventional PECs used in renewable energy systems, with a focus on DC-AC, DC-DC, and AC-DC converters. The study combines life cycle assessment (LCA) with the Circular Energy Sustainability Index (CESI) to evaluate both environmental performance and material circularity. The LCA is conducted using a functional unit defined as a representative converter, within consistent system boundaries that encompass material extraction, manufacturing, and end-of-life stages. This approach enables comparability among converter topologies but introduces limitations related to the exclusion of application-specific design optimizations, such as maximum efficiency, spatial constraints, and thermal management. CESI is subsequently applied as a decision-support tool to rank converter technologies according to sustainability and circularity criteria. The results reveal substantial differences among converter types: the controlled rectifier exhibits the lowest environmental impact and the highest circularity score (95.3%), followed by the uncontrolled rectifier (69.3%), whereas the inverter shows the highest environmental burden and the lowest circularity performance (38.6%), primarily due to its higher structural complexity and the material and manufacturing intensity associated with its switching architecture.

1. Introduction

The incorporation of renewable energy sources (RES) forms the cornerstone of the global energy transition, driven by the urgent need to ensure a sustainable future and mitigate climate change [1]. Wind power, photovoltaics, and battery storage have become essential components of the modern energy mix [2].

However, power electronic devices are crucial for enabling the energy produced by RES to be optimally utilized by industrial and domestic loads or integrated into the electrical grid [3]. Power electronic converters (PECs), such as inverters, rectifiers, and DC-DC converters, serve as the critical interface between RES and the grid. They condition power quality, frequency, and voltage. Given their indispensable role in renewable energy systems, their overall environmental impact cannot be ignored [4].

Historically, scientific research on the environmental impacts of RES has focused primarily on core components like wind turbines and solar panels [5]. Yet, a comprehensive sustainability assessment requires analyzing auxiliary components as well. This is where a life cycle assessment of power converters becomes essential. LCA is a standardized method for quantifying the environmental impacts of a product or service “from cradle to grave”, that is, from raw material extraction and manufacturing through operation to end-of-life disposal [6]. Key reasons to apply LCA to power converters include the following [7]:

- Carbon footprint: Their production involves energy-intensive materials and processes, generating a significant carbon footprint. Although smaller than that of primary RES generators, this impact scales globally with the vast number of installations.

- Efficiency and losses: Switching losses in semiconductor devices lead to ongoing energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions over the system’s life cycle.

- Waste management and circular economy: Power converters contain valuable yet potentially hazardous materials. LCA reveals material compositions to inform recycling strategies and end-of-life management, advancing circular economy principles.

- Sustainable design choices: LCA enables comparison of converter architectures, identifying those with minimal environmental impact and guiding policymakers and engineers toward optimal RES designs.

The most relevant literature has focused intensively on estimating the environmental burdens generated by electricity generation technologies. Recent LCA studies have focused their efforts on investigating the environmental consequences of the extraction and processing of fundamental materials required for renewable energy technologies. This has been driven by concerns about sustainability in the supply chain [8,9]. This leads to research focusing on applying LCA exclusively to generation plants, neglecting converters. Examples include [10,11], which only apply LCA to wind turbines, photovoltaic panels, or other electricity generation plants, never considering the devices responsible for grid interconnection.

However, comparative LCA assessments of life cycle scenarios have recently been conducted to evaluate the incorporation of circular economy (CE) strategies in the energy sector. Examples include [12,13], which demonstrate that the recovery of critical materials significantly reduces the impact of certain categories. Also, Ref. [14] points out the importance of having standardized metrics to quantify circular benefits, as without them, the renewable energy transition is not sustainable.

This paper addresses the existing gap in the literature regarding the integrated environmental and circularity assessment of power electronics converters used in renewable energy systems. The main objective is to perform a comparative LCA of key converter technologies, and based on these results, to develop and apply the Circular Energy Sustainability Index (CESI), which explicitly focuses on material circularity and sustainability by weighing relevant criteria and sub-indices. The central research question guiding this study is: which power electronics converters offer the best environmental and circular performance, and to what extent are current technologies truly sustainable and environmentally friendly? The main contribution of this work lies in providing empirical LCA-based evidence and a novel decision-support index that enables the classification and selection of the most environmentally favorable converter technologies, thereby supporting more informed decisions aimed at improving the sustainability of the current energy mix.

2. Materials and Methods

This research combines the CESI and LCA, applied to the most used PECs for coupling RES, thereby reducing uncertainty in the results and assisting energy policymakers.

An LCA analyzes the environmental impact of technology throughout its entire life cycle, from resource extraction and materials processing to operation, maintenance, and decommissioning [15]. It thus provides data on the impact of PECs in specific categories. The CESI, for its part, facilitates the comparison and categorization of different technologies according to various criteria. Each criterion needs to be weighed, and then a percentage is obtained for each sub-index. These percentages are used to calculate a total CESI score, which indicates the potential for circularity and sustainability.

2.1. Power Electronics Converters

The electrical grid has evolved into a power electronics-driven system as conventional technologies are gradually replaced by renewable energy sources, such as wind and photovoltaic systems [16]. The intermittent and stochastic nature of these resources poses significant challenges for energy flow control, power quality, and stability. Consequently, power electronics converters have evolved from simple conversion components into crucial intelligent interfaces that enable the technical feasibility of distributed generation [17].

The primary functions of PECs extend beyond merely adapting frequency or voltage levels. They play a key role in managing the dynamics of interfacing generating sources with the grid or isolated loads. The specific characteristics of each renewable source determine the appropriate conversion architecture, which ensures optimal energy extraction and compliance with grid codes, including backup capabilities like low-voltage ride-through and reactive power injection during faults [18].

PECs are categorized topologically based on the required conversion stage: DC-DC converters, inverters, and rectifiers [19]. DC-DC converters are fundamental in energy storage and photovoltaic applications, where they regulate the DC bus and implement maximum power point tracking algorithms to enhance efficiency amid varying temperature and solar irradiance [20]. To minimize current ripples and semiconductor voltage stress, traditional topologies like Buck-Boost or Ćuk converters have evolved into resonant or interleaved structures [21].

Inverters form the second stage, serving as the final interface to the AC grid. They manage grid synchronization, power factor control, and total harmonic distortion [22]. The integration of wind power, particularly in variable-speed systems with permanent magnet synchronous generators or doubly fed induction generators, has further advanced AC-DC-AC converters [23].

Although these configurations have achieved high operational efficiency, research on their environmental impacts remains scarce. Sustainability assessments of renewable energy systems often focus primarily on the energy source itself, overlooking the converters’ contributions. These devices incorporate complex materials, such as rare-earth magnets, electrolytic capacitors, doped semiconductors, and large quantities of copper and aluminum, that significantly affect metrics like human toxicity and resource depletion. Incorporating life cycle assessment is thus essential to quantify their material and energy flows. Combining the LCA of PECs with that of the generating source yields more accurate environmental profiles, avoiding underestimation of the carbon footprint. This holistic approach is vital to substantiate the environmental benefits of energy transition and inform the eco-design of future converters.

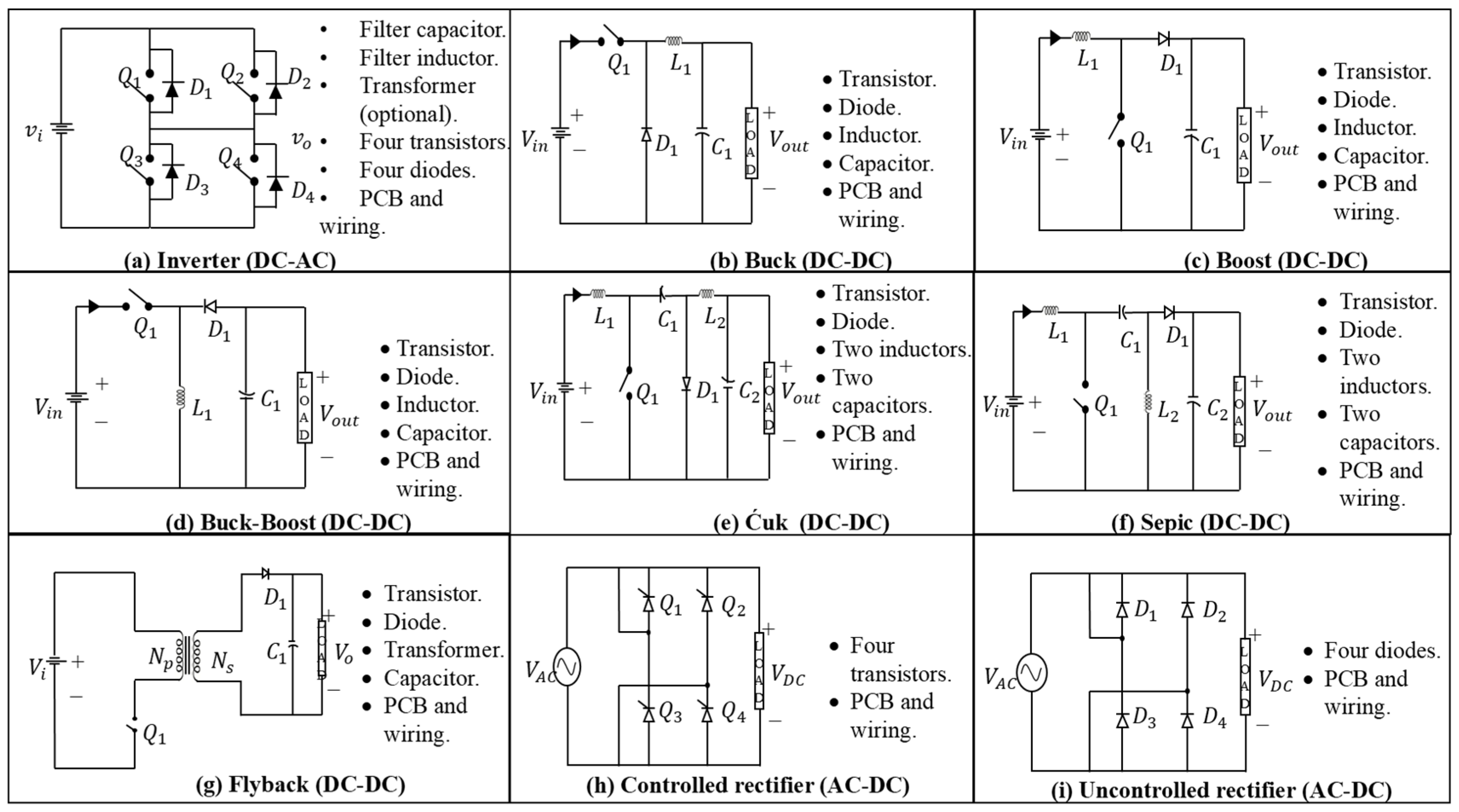

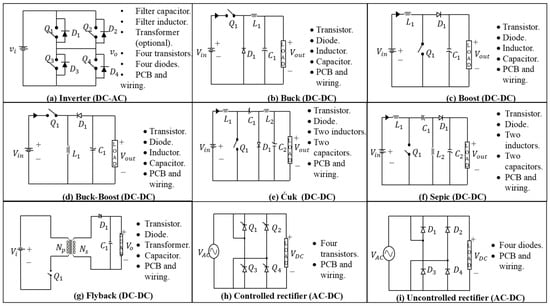

Figure 1 shows the types and topologies of converters used in this study. The topologies are based on those found in Refs. [24,25,26].

Figure 1.

Representative circuit topologies of the power electronic converters (PECs) evaluated in the sustainability and circularity study: (a) inverter, (b) buck, (c) boost, (d) buck-boost, (e) Ćuk, (f) Sepic, (g) flyback, (h) controlled rectifier, and (i) uncontrolled rectifier.

2.2. Life Cycle Assessment Methodology

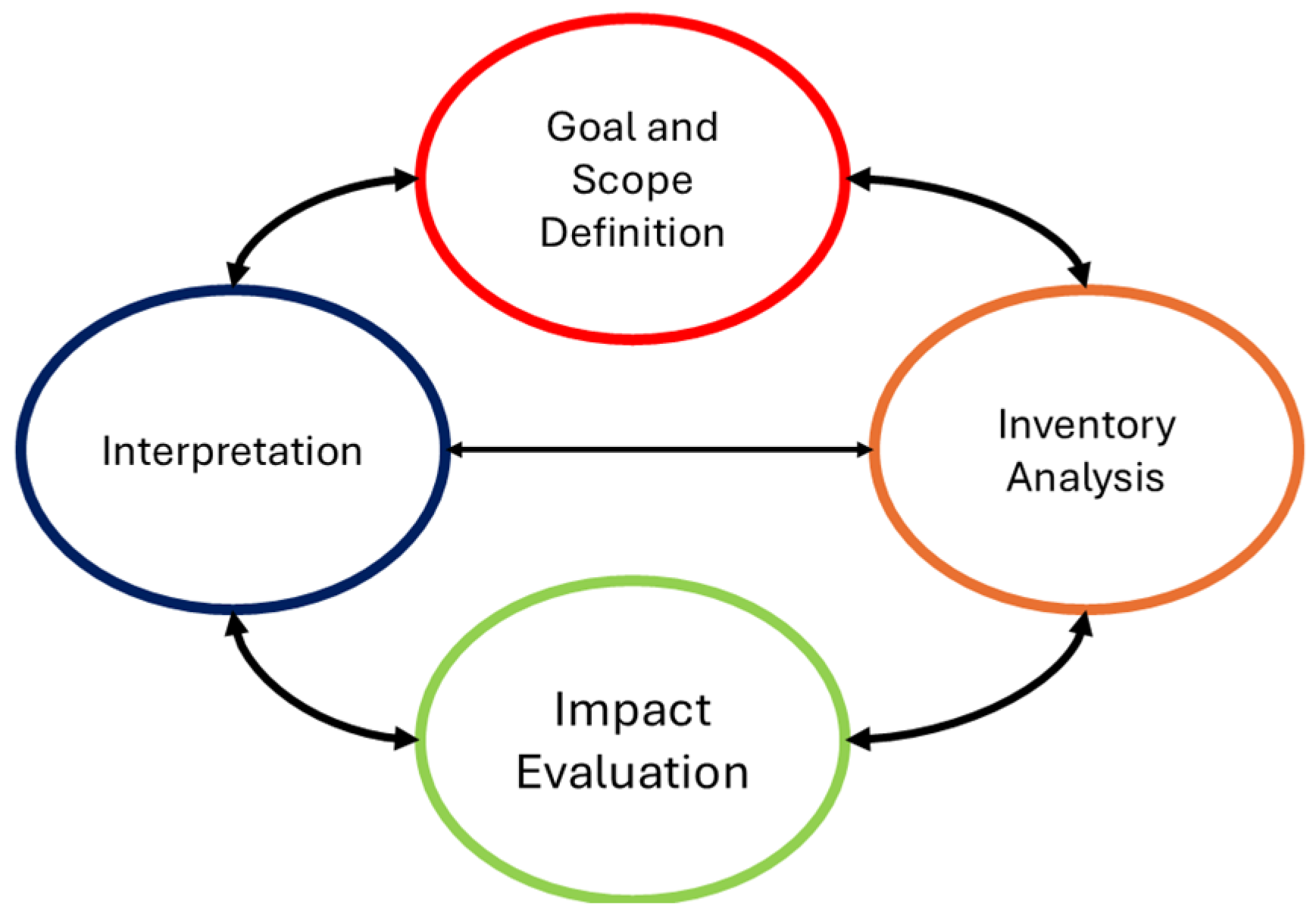

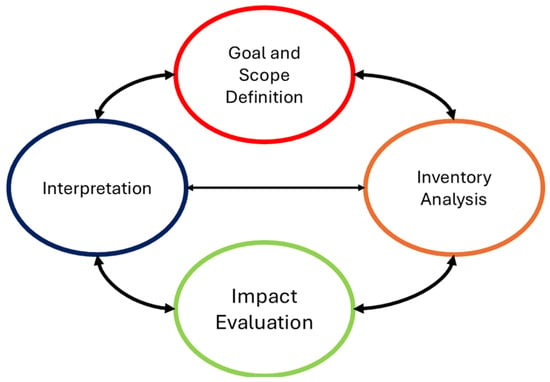

LCA was employed to assess the environmental impacts of PECs, as it provides a quantitative and comparative approach to identifying environmentally preferable products and designs. Its primary goals are to inform on product performance and guide improvements that minimize pollution across all life cycle stages [27]. Figure 2 illustrates the structure of the LCA methodology. This comprehensive methodology allows for a cradle-to-grave evaluation of a product’s environmental performance, identifying environmental hotspots within its supply chain for potential optimization. This structured approach, formalized by ISO 14040 [28], involves four distinct phases: goal and scope definition, inventory analysis, impact assessment, and interpretation [29]. Each phase plays a crucial role in systematically evaluating the environmental burdens associated with a product, process, or service throughout its entire life cycle.

Figure 2.

Structure of the LCA methodology.

2.2.1. Goal and Scope Definition

The goal and scope definition phase begins by establishing the study’s objective and the information to be obtained [27]. The goal of this LCA is to compare the environmental impacts of different power electronics converter topologies commonly used in RES. The functional unit is defined as one representative power electronics converter. This functional unit was selected to enable a consistent comparison among converter topologies with different structural characteristics and component compositions. Consequently, the environmental impacts are not normalized per unit of power (kW), operational lifetime, duty cycle, or efficiency.

The system boundaries include raw material extraction, component manufacturing, assembly, and end-of-life treatment of the converter. The use phase is excluded from the assessment to avoid introducing additional uncertainties associated with application-specific operating conditions, such as load profiles, efficiency variations, duty cycles, and lifetime assumptions. This approach ensures comparability across converter topologies but introduces limitations regarding the generalization of the results to specific operational scenarios or performance-optimized designs. Therefore, the results should be interpreted as a comparative assessment at the component level rather than as an absolute evaluation of operational performance.

2.2.2. Life Cycle Inventory Analysis (LCI)

The life cycle inventory phase compiles data on the raw materials required and the energy used to build and maintain power converters. The inventory was developed based on data presenting the potential inventory of one inverter, presented in [30]. Materials were then added or removed to adapt the inventory for the other converters. The LCI was developed using a material-based characterization approach rather than relying on specific commercial models of switches or active components (e.g., individual IGBT or MOSFET devices). For each converter topology, the inventory was constructed by disaggregating the main functional elements into their fundamental constituent materials, including representative average masses of silicon, copper, epoxy resins, and bonding metals.

This approach ensures that the resulting LCA reflects generic and representative power electronics technologies, minimizing potential biases related to manufacturer-specific production procedures, data availability, or proprietary bill-of-materials information. Auxiliary elements, such as housing, coatings, and terminals, were kept constant across all converter configurations, providing a common baseline. This consistent treatment enables a more robust comparative analysis, allowing sustainability performance to be primarily driven by differences in the power electronic elements that most strongly influence the environmental footprint. Background data related to material extraction and the energy mix were sourced from the Life Cycle Database (LCD) developed by GreenDelta [31]. This rigorous approach ensures a comprehensive accounting of inputs and outputs throughout the PECs’ life cycle, enabling a robust assessment of their environmental footprint. This systematic compilation of inputs and outputs across all life cycle stages is critical for the subsequent impact assessment, where these inventory flows are translated into quantifiable environmental impacts.

2.2.3. Life Cycle Impact Evaluation

This phase links the inventory analysis to the potential environmental impacts of the studied system, emphasizing the importance of quantifying the resulting damage [27]. The impact assessment was conducted using the ReCiPe 2016 Midpoint method [32]. Although several impact categories were evaluated, this analysis focuses on global warming potential, expressed in kg CO2 eq, due to the critical role of materials in power electronics, which often generate substantial greenhouse gas emissions. This focus aligns with current environmental concerns regarding climate change and highlights the significant contribution of power electronics manufacturing to overall carbon footprints.

2.2.4. Interpretation

The final LCA phase involves making recommendations for system modifications or improvements to reduce environmental impacts. These may include qualitative and quantitative changes, such as adjustments to systems, processes, raw materials, or waste management practices. In this case, the results are used to evaluate the circularity of these converters based on a circularity index. This index offers a holistic perspective on resource efficiency and ecological burden reductions throughout the PEC lifespan.

2.3. Circular Energy Sustainability Index

Several specific and flexible indices have been developed to assess circularity and sustainability. For example, the Material Circularity Indicator (MCI) evaluates circularity and environmental sustainability at the product level. Extensions of the MCI have enabled the assessment of circular performance in the life cycle management of components, such as wind turbine blades, by quantifying material efficiency gains derived from recycling processes [33,34].

In addition, qualitative indices have been proposed to support decision-making in the energy sector by providing guidelines and standards aligned with circular economy (CE) principles, aiming to reduce the ecological footprint of industrial activities [35,36].

As can be observed, many existing circular economy indices focus on specific aspects, such as carbon emissions, material flows, or economic costs. However, only a limited number offer a comprehensive perspective that integrates circularity with life cycle environmental impacts.

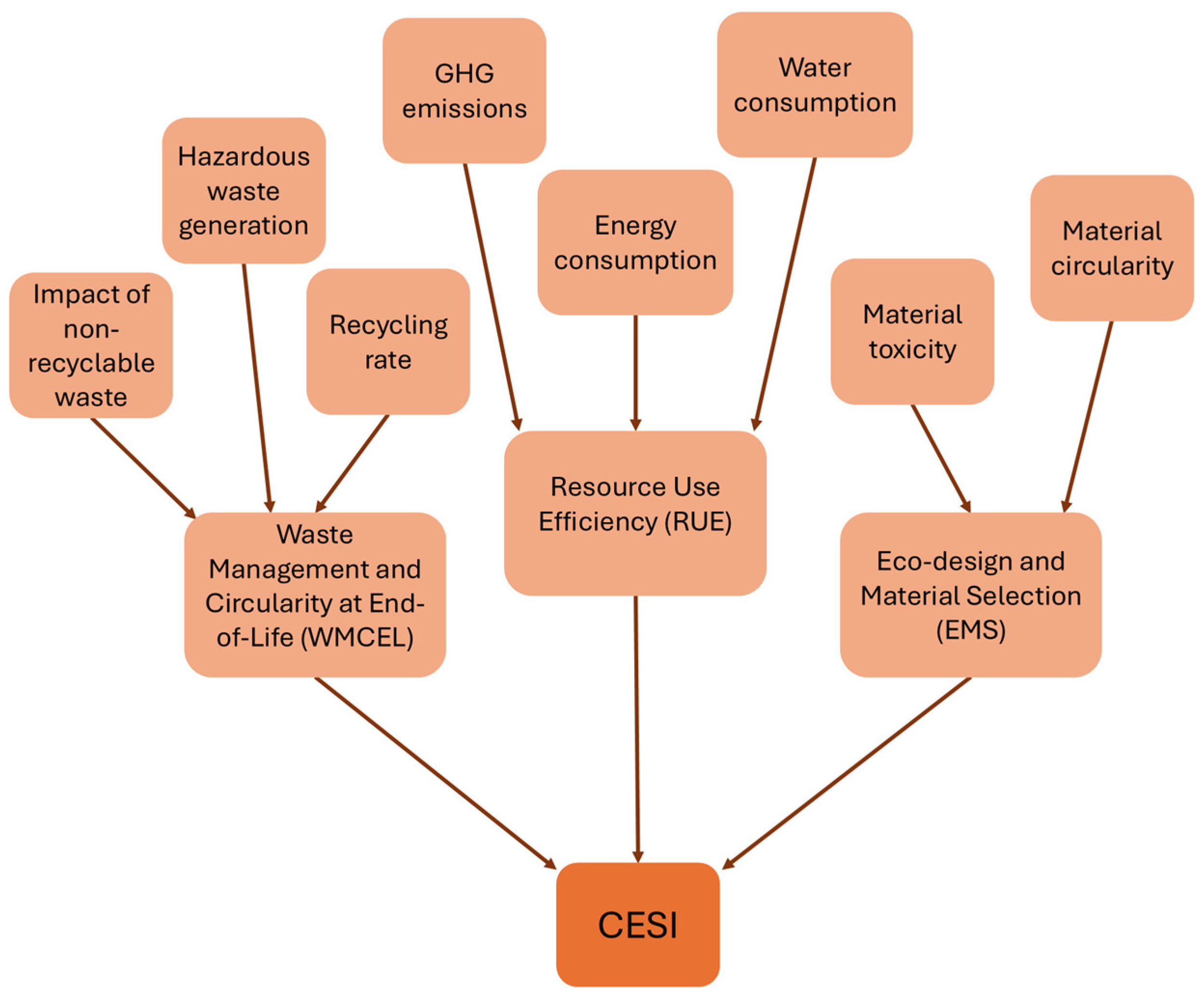

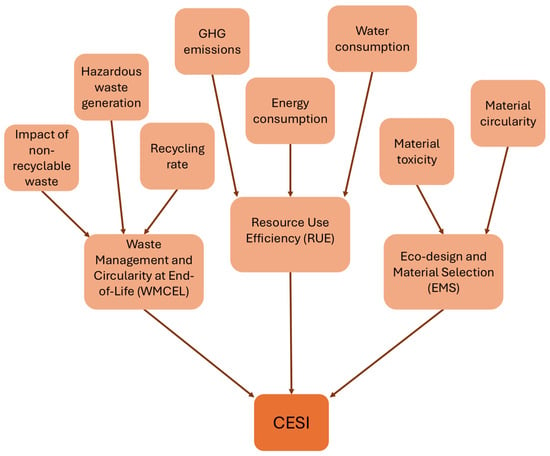

To address this gap, this study utilizes the CESI [27] because traditional measures fail to account for circularity and sustainability, while pure cycle assessment studies often overlook circular dynamics. The CESI integrates operational energy efficiency with life cycle environmental impacts and the circularity of both materials and power electronics converters through a set of criteria and sub-indices, as illustrated in Figure 3. This structure enables the classification of converter topologies that may exhibit high efficiency but require excessive material inputs or rely on scarce or highly toxic components [37]. The CESI is used because conventional LCA does not adequately account for the recoverability of essential materials or the complexity of the electronic manufacturing process. The CESI functions as a circular performance indicator that complements environmental impact assessments, providing a more useful measure for developing sustainable engineering policies. Equation (1) defines the CESI as a weighted combination of normalized sub-indices representing operational energy efficiency, life cycle environmental performance, and material circularity. This linear aggregation ensures transparency, interpretability, and robustness, while enabling direct comparison among power electronic converter topologies. By integrating these dimensions within a unified metric, CESI complements conventional LCA, which alone does not fully capture circular dynamics, material recoverability, or the complexity of electronic manufacturing processes.

Figure 3.

Structure of the CESI methodology.

The CESI comprises three weighted sub-indices:

- EMS, the “Eco-Design and Material Selection” sub-index (maximum 10 points; 30% of total CESI score), which includes material circularity and material toxicity.

- RUE, the “Resource Use Efficiency” sub-index (35% of total CESI score, equivalent to 15 points), which includes water consumption, energy consumption, and greenhouse gas emissions.

- WMCEL, the “Waste Management and Circularity at End-of-Life” sub-index (35% of total CESI score, equivalent to 15 points), which includes recycling rate, hazardous waste generation, and environmental impact of non-recyclable waste.

In Equation (1), the point-based scoring system is used to evaluate the relative performance of each criterion within a sub-index, while the percentage values represent the weighting factors that define the contribution of each sub-index to the overall CESI score. A higher relative importance (35% each) is assigned to RUE and WMCEL compared to EMS (30%) based on a life cycle priority approach. This distribution emphasizes the operational efficiency and material recovery potential over the initial manufacturing burden. This is consistent with the long service life of PECs in renewable energy applications, where cumulative energy savings and circular end-of-life strategies yield the most significant long-term environmental benefits.

The criteria that make up the index, as shown in Figure 3, are evaluated using the scoring scale in Table 1, informed by the researcher’s judgment, LCA results, and a sensitivity analysis.

Table 1.

Scoring scale for the criteria.

Determining the CESI enables topologies to be classified not only by their greenhouse gas emissions but also by their ecological return on investment, thereby providing a holistic decision-making tool for designing sustainable future microgrids. This approach offers a nuanced perspective beyond conventional efficiency metrics by integrating circular economy principles and material sustainability, which are often neglected in standard life cycle assessments.

3. Results

Bills of materials were compiled for each power electronic converter topology. These data were implemented in openLCA 2.0, 2023 using the database Life Cycle Database (LCD) developed by GreenDelta [31]. A life cycle assessment was then performed for each PEC, allowing the systematic quantification and classification of their environmental impacts across multiple impact categories, as summarized in Table 2. This approach allows for a comprehensive evaluation of the PECs’ contributions to environmental burdens, expressed in terms of equivalent kilograms of CO2 emissions (kg of CO2 eq). By normalizing the LCA results, the data in Table 2 facilitate a clear comparison of the environmental footprint of each converter, highlighting which stages or components contribute most significantly to greenhouse gas emissions.

Table 2.

Environmental impact results for the nine power electronic converter topologies.

This detailed classification supports identifying critical areas for improvement in the design, manufacturing, or operational phases of the converters to reduce their overall environmental impact. Moreover, presenting the results in CO2 equivalent units aligns with widely accepted standards for assessing climate change impacts, enabling stakeholders to make informed decisions regarding sustainability and regulatory compliance. Such insights are essential for optimizing the converters’ life cycles toward minimizing carbon footprints and promoting environmentally responsible technology development.

As shown in Table 2, the PECs are classified by color and section. This is because PECs with the same color have the same electronic components but different topologies, which means that the components are arranged differently. This also affects the environmental impact, as converters with the same components generate the same amount of pollution. Now, after performing LCA, the CESI can be determined. To do this, data from Table 2 were selected, and the CESI criteria were weighed, considering Table 1 and the researcher’s criteria. Table 3 combines selected environmental indicators derived from Table 2 with circularity-related parameters, such as material circularity and circularity rate. These parameters constitute the input variables used to evaluate each PEC and to compute the CESI percentage.

Table 3.

Detailed CESI assessment indicators for each converter.

The negative values observed in indicators such as water consumption and resource scarcity result from the substitution of primary material production by secondary material flows generated within the PEC life cycle, as shown in Table 3. These avoided impacts reflect the displacement of resource- and water-intensive upstream processes. For example, the recovery and reintegration of conductive metals into the production cycle reduces the demand for virgin material extraction, which is typically associated with high water consumption. In such cases, the environmental credits from avoided primary production exceed the impacts generated during end-of-life processing, leading to a net negative balance that represents an environmental benefit.

Using the data presented in Table 3 alongside the weight factors detailed in Table 1, the CESI can be systematically computed. This calculation integrates the individual contributions of various environmental indicators, each adjusted according to its assigned weights, to produce a comprehensive metric that reflects overall sustainability performance. The subsequent Table 4 illustrates the specific weightings applied and the percentage contributions of each sub-index that collectively form the CESI, thereby offering a detailed breakdown of how each environmental dimension influences the final index value. Table 4 presents the results obtained by processing the data reported in Table 3 through Equation (1), applying the weighting factors defined in Table 1. This table provides a multidimensional evaluation by reporting the individual sub-index scores (EMS, RUE, and WMCEL), as well as the final CESI percentage for each converter topology.

Table 4.

CESI scores and sub-index breakdown (EMS, RUE, and WMCEL) for the comparative assessment of converter sustainability.

This table serves to clarify the relative importance of different sub-indices within the CESI framework, highlighting the proportional impact of each component on the composite measure. By presenting both the weightings and the resulting percentages, they facilitate a transparent understanding of the index’s composition, enabling stakeholders to identify key areas of strength and concern within the environmental sustainability assessment. This structured approach ensures that the CESI is not only a holistic indicator but also a tool that can guide targeted policy and decision-making efforts based on the weighted significance of its constituent sub-indices.

The procedure for obtaining sub-index percentages involves applying the simple direct rule of three, where an increase in one quantity results in a proportional increase in another. If the values A, B, and X are known, and Y is unknown, the rule is expressed as follows:

An example of how the percentages are obtained is as follows: for the first sub-index, the maximum score is 10 points, equivalent to 30%. Inverter is weighted as “very low” in both subindex criteria, which adds up to a score of 2 points, according to Table 1. Applying (2), we obtain

This method is consistently applied across all sub-indices.

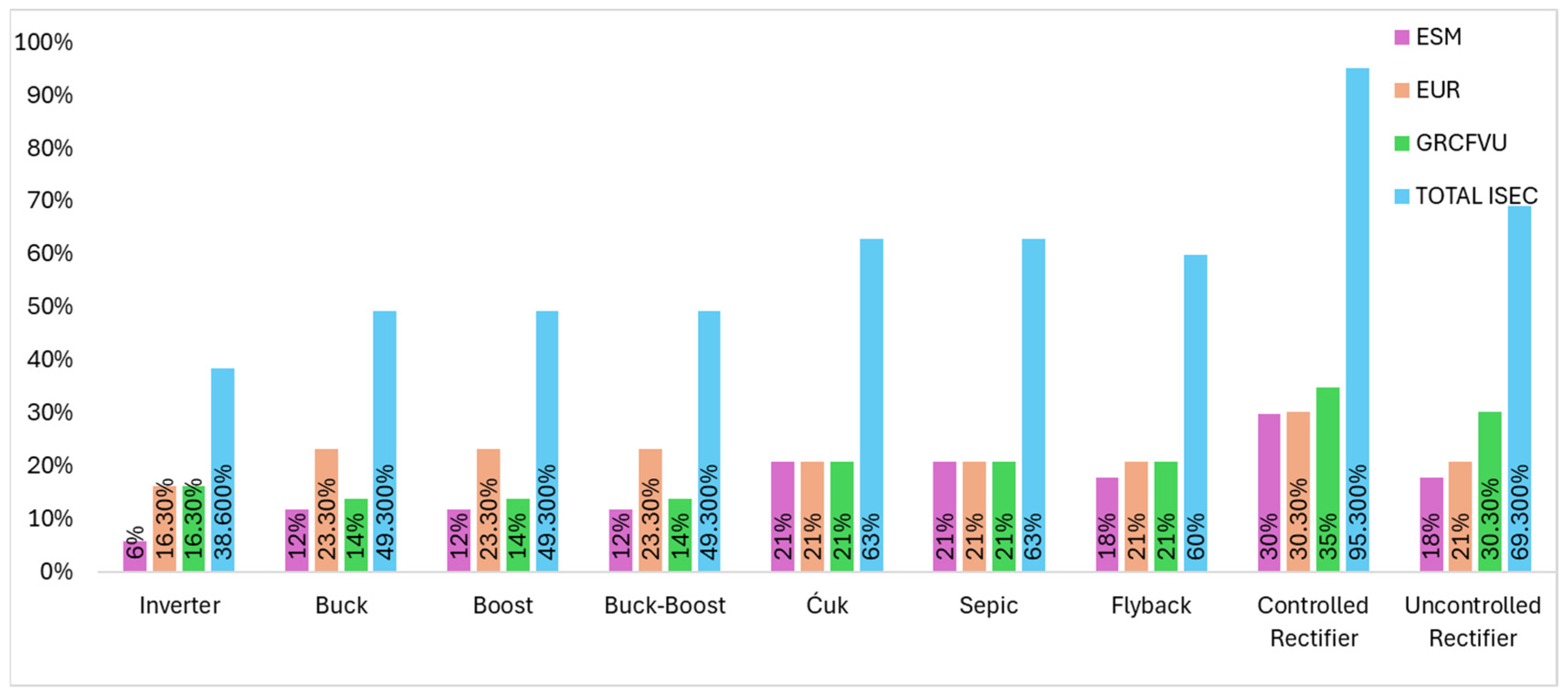

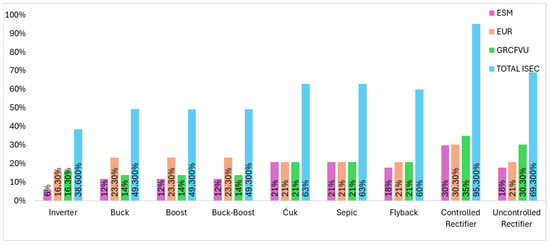

After obtaining the scores for each sub-index, the overall CESI value for every PEC was calculated. Using Equation (1), the final CESI values for each power converter type are obtained. To facilitate the interpretation of these results, a visual comparison is provided. Figure 4 presents a bar chart illustrating the individual sub-index percentages and the resulting total CESI score for each converter. This figure provides a comparative visual representation of the nine converter topologies, allowing the identification of the life cycle stage (manufacturing, use, or end-of-life) that dominates or penalizes the sustainability performance of each converter.

Figure 4.

Percentages of the CESI framework: variation in the sustainability scores across each sub-index per converter.

These results reveal notable differences among converter technologies. The highest CESI value corresponds to the controlled rectifier (95.3%), indicating a substantially higher combined sustainability performance across all three dimensions. Conversely, the inverter presents the lowest CESI score (38%), primarily due to its comparatively low environmental and technical sub-index values. Intermediate technologies, such as the buck, boost, and buck-boost converters, cluster around 49%, whereas converters with more balanced environmental and functional characteristics, such as Ćuk, Sepic, and flyback topologies, achieve CESI values between 60% and 63%.

A sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the robustness of the CESI framework and to evaluate the influence of weighting assumptions on the final sustainability rankings. This analysis involved systematically modifying the weights of the sub-indices under three representative scenarios, each emphasizing a different life cycle stage:

- Scenario A (Manufacturing-focused): 100% increase in the weight of the EMS (materials) sub-index.

- Scenario B (Use-phase efficiency-focused): 100% increase in the weight of the RUE (efficiency) sub-index.

- Scenario C (End-of-life-focused): 100% increase in the weight of the WMCEL (recycling) sub-index.

The results demonstrate that, despite substantial variations in the weighting scheme, the relative sustainability ranking of the PECs remains largely unchanged. In particular, the inverter consistently appears as the least sustainable option due to its high active material requirements, while the controlled rectifier remains the most sustainable alternative across all scenarios, with variations below 7%. These findings confirm that the CESI methodology is robust with respect to reasonable changes in weighting assumptions and that the overall conclusions are not unduly influenced by researcher judgment.

4. Discussion

The integration of LCA with the CESI framework provides a ranking that delivers valuable insights for experts and energy sector managers. These results can assist national decision-makers in proposing improvements or adjustments to the energy mix, as the combined methodology offers a more comprehensive perspective through its holistic evaluation. Moreover, this analysis can complement LCAs of entire power generation plants by incorporating the environmental performance of all components involved in the deployment and integration of renewable energy systems into the electrical grid.

An examination of the sub-index scores (see Table 4) reveals several noteworthy findings. In the EMS sub-index, the controlled rectifier exhibits the highest material circularity and the lowest toxicity, achieving the top score of 30%. In contrast, the inverter obtains the lowest score (6%), largely due to its limited compatibility with circular economy principles and the high toxicity of some of its constituent materials. Additionally, converters that share similar power electronic components tend to obtain identical or nearly identical EMS scores, reflecting the similarity of their material compositions.

For the RUE sub-index, the second component of CESI, the controlled rectifier once again ranks highest with 30.3%, while the inverter records the lowest value at 16.3%. This sub-index reflects water and energy consumption during operation as well as potential greenhouse gas emissions, thus serving as an indicator of the resource use efficiency of each converter.

In the WMCEL sub-index, the final CESI component, the controlled rectifier, maintains the highest score (35%), followed by the uncontrolled rectifier (30.3%). Conversely, the buck, boost, and buck-boost converters obtain the lowest value (14%), with the inverter slightly higher at 16.3%. These percentages capture the potential end-of-life impacts of the devices, including the proportion of non-recyclable materials, the generation of hazardous waste, and the expected recycling rate of the components.

Considering all sub-index values, the total CESI scores reveal a clear hierarchy. The controlled rectifier achieves the highest overall score (95.3%), followed by the uncontrolled rectifier (69.3%). The Ćuk and Sepic converters rank third with 63%, the flyback converter follows with 60%, and the buck, boost, and buck-boost converters share a score of 49.3%. The inverter ranks last at 38.6%. These results suggest that controlled and uncontrolled rectifiers exhibit the greatest potential for implementing circular economy principles, making them the most sustainable options among the analyzed converters. In contrast, the inverter would require significant improvements in material selection and circularity strategies to enhance its sustainability performance. The fact that converters with identical electronic components consistently receive identical scores further reinforces the material-based nature of the CESI evaluation.

Recent system-level studies, such as [38], underline the importance of strategic planning in renewable energy infrastructure to achieve net-zero emission targets. However, the sustainability of these large-scale systems is intrinsically linked to the environmental and circular performance of their power electronic interfaces. While system-oriented analyses primarily report operational carbon footprint reductions, the present study extends this perspective by integrating the CESI framework, which combines operational efficiency, life cycle environmental impacts, and material circularity. This approach ensures that gains achieved at the infrastructure level are not compromised by low circularity, high material toxicity, or resource-intensive manufacturing processes associated with energy conversion stages.

The results indicate that the sustainability performance of power electronics converters strongly depends on their application and structural characteristics. From a practical perspective, the findings can be interpreted as follows:

- Converter design: Converter topologies with higher CESI scores, such as Ćuk and SEPIC converters, exhibit inherent advantages in harmonic mitigation and filtering requirements. To further reduce the environmental footprint of manufacturing, designers should prioritize the simplification of the bill of materials and component count.

- Policymaking: CESI values may be used as quantitative benchmarks to support regulatory and economic instruments, such as tax incentives or certification schemes, for equipment exceeding defined electronic circularity thresholds, thereby fostering circular economy practices within the power electronics industry.

- Eco-design strategies: Converter architecture that allows the decoupling of control and filtering stages from the power stage facilitates modular upgrades, extends product lifetimes, and improves overall circularity.

Despite the methodological rigor of the proposed framework, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the life cycle inventory data were primarily obtained from standard databases, which, while reliable, may not fully capture specific manufacturing practices or recent technological improvements. Second, the system boundaries were defined to ensure comparability among converter topologies, but they do not account for design optimizations related to maximum efficiency, spatial constraints, or thermal management. Finally, the results should be interpreted with caution regarding their generalizability, as the analysis is based on representative converter designs rather than application-specific industrial implementations.

5. Conclusions

This study evaluated the current environmental performance of power electronic converters used in renewable energy systems. To achieve this, LCA was employed to quantify the environmental impacts of these devices, while the CESI was used to assess their circularity potential at end-of-life and their overall sustainability. Ranking calculations were then performed to identify the most sustainable converter technologies.

The environmental effects of nine converter categories were analyzed, grouping them according to their constituent components. Subsequently, the LCA results were integrated into the CESI framework to weigh each device according to the criteria and sub-indices defined in the methodology. The scope of the study covered the complete life cycle of the converters. The overall sustainability ranking indicates that controlled and uncontrolled rectifiers, along with the Ćuk and Sepic converters, exhibit the lowest environmental burdens and therefore represent the most environmentally favorable options.

These results suggest that increasing the use of rectifiers, as well as Ćuk and Sepic topologies, in renewable energy integration strategies could contribute positively to the sustainability of the energy mix. This study indicates that they have a high potential for circularity and sustainability, with 95% and 69% for rectifiers, and 63% for Ćuk and Sepic converters, respectively; this, in turn, indicates that they have low pollution levels. Therefore, combining LCA data with circular economy tools such as CESI is essential to generate comprehensive and practical information that supports the prioritization of sustainable energy development in the energy sector.

Future research could build upon these findings by examining how grid modernization efforts may influence the life cycle environmental performance of the electricity generation portfolio, for example, by assessing the integration of energy storage systems or advanced power-conditioning technologies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: D.L.O.-F. and R.P.-G., Methodology: D.L.O.-F. and R.P.-G.; Software: D.L.O.-F.; Validation: D.L.O.-F. and R.P.-G.; Formal analysis: D.L.O.-F. and R.P.-G.; Investigation: D.L.O.-F. and R.P.-G.; Resources: R.P.-G.; Data curation: D.L.O.-F.; Writing—original draft preparation: D.L.O.-F. and R.P.-G.; Writing—review and editing: D.L.O.-F. and R.P.-G.; Visualization: D.L.O.-F.; Supervision: R.P.-G.; Project administration: R.P.-G.; Funding acquisition: R.P.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the first author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Universidad Autónoma de San Luis Potosí for providing the necessary facilities for this research. Diana L. Ovalle Flores is thankful to SECIHTI for providing financial support for her Ph.D. studies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| PECs | Power Electronics Converters |

| CESI | Circular Energy Sustainability Index |

| RES | Renewable Energy Sources |

| EMS | Eco-Design and Material Selection |

| RUE | Resource Use Efficiency |

| WMCEL | Waste Management and Circularity at End of Life |

References

- Gielen, D.; Boshel, F.; Saygin, D.; Bazilin, M.; Wagner, N.; Gorini, R. The role of renewable energy in the global energy transformation. Energy Strategy Rev. 2019, 24, 38–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.J.; Lewis, N.S.; Shaner, M.; Aggarwal, S.; Arent, D.; Azevedo, I.L.; Benson, S.M.; Bradley, T.; Brouwer, J.; Chiang, Y.M.; et al. Net-zero emissions energy systems. Science 2018, 360, eaas9793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, B.K. Global Energy Scenario and Impact of Power Electronics in 21st Century. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2013, 60, 2638–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorente-Igleasias, R.; Lacal-Arantegui, R.; Aguado-Alonso, M. Power electronics evolution in wind turbines—A market-based analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 4982–4993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoyo-Castelazo, R.; Azapagic, A. Sustainability assessment of energy systems: Integrating environmental, economic and social aspects. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 80, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.; Evans, D. Use of Life Cycle Assessment in Environmental Management. Environ. Manag. 2002, 29, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebitzer, G.; Ekvall, T.; Frischknecht, R.; Hunkeler, D.; Norris, G.; Rydberg, T.; Schmidt, W.-P.; Suh, S.; Weidema, B.P.; Pennington, D.W. Life cycle assessment: Part 1: Framework, goal and scope definition, inventory analysis, and applications. Environ. Int. 2004, 30, 701–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, A.; Marx, J.; Zapp, P. Life Cycle Assessment studies of rare earths production—Findings from a systematic review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 791, 148257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelli, A.; Barbini, F.; Paoli, R.; Marzeddu, S.; Romagnoli, F. Critical Raw Materials in Life Cycle Assessment: Innovative Approach for Abiotic Resource Depletion and Supply Risk in the Energy Transition. Energies 2025, 18, 6103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhm, J.; Michael-Holzheid, F.; Schäfer, M.; Krexner, T. Life cycle assessment of electricity from wind, photovoltaic and biogas from maize in combination with area-specific energy yields—A case study for Germany. Environ. Res. Commun. 2024, 6, 105022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Hassan, M.; Rasul, M.; Emami, K.; Ahmen-Chowdhury, A. Life cycle environmental assessment of hybrid renewable energy system, 2024 9th International Conference on Sustainable and Renewable Energy Engineering. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 545, 01001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sica, D.; Malandrino, O.; Supino, S.; Testa, M.; Lucchetti, M.C. Management of end-of-life photovoltaic panels as a step towards a circular economy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 2934–2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Kang, X. Recycling wind turbine blades: A comprehensive review of challenges, solutions, and future directions. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 114, 114489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisellini, P.; Passaro, R.; Ulgiati, S. Assessing the environmental sustainability and justice dimensions of nuclear electricity under circular economy and energy transition frameworks. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 491, 144818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannan, S. Lees’ Loss Prevention in the Process Industries, 4th ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 2507–2521. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, J.; Madureira, A.; Matos, M.; Bessa, R.; Monteiro, V.; Afonso, J.; Santos, S.; Catalao, J.; Antunes, C.; Magalhães, P. The Future of Power Systems: Challenges, Trends and Upcoming Paradigms. WIREs Energy Environ. 2019, 9, e368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giudice, D.; Brambilla, A.; Grillo, S.; Bizzarri, F. Effects of inertia, load damping and dead-bands on frequency histograms and frequency control of power systems. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 129, 106842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joddumahanthi, V.; Knypinski, L.; Gopal, Y.; Kasprzak, K. Review of Power Electronics Technologies in the Integration of Renewable Energy Systems. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, B.K. Power Electronics, Smart Grid, and Renewable Energy Systems. Proc. IEEE 2017, 105, 2011–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, F.; Yahaya, Z.; Tanzim-Meraj, S.; Singh, B.; Kannan, R.; Ibrahim, O. Review on non-isolated DC-DC converters and their control techniques for renewable energy applications. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2021, 12, 3747–3763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, L.; Torre, G.; Sanchez, J.; Maiz, A.; Sanchez-Ruiz, A.; Jugo, J.; Ortega, E. DC-DC Boost converter with maximum power point tracking for photovoltaic arrays. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 53rd Photovoltaic Specialists Conference (PVSC), Montreal, QC, Canada, 8–13 June 2025; pp. 0175–0179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critchley, L. How Do Inverters Contribute to Grid Resilience? EE Power. 2024. Available online: https://eepower.com/tech-insights/how-do-inverters-contribute-to-grid-resilience/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Blaabjerg, F.; Chen, M.; Huang, L. Power electronics in wind generation systems. Nat. Rev. Electr. Eng. 2024, 1, 234–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjaer, S.B.; Pedersen, J.K.; Blaabjerg, F. A review of single-phase grid-connected inverters for photovoltaic modules. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2005, 41, 1292–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutikno, T.; Saudi-Samosir, A.; Aprilianto, R.; Satrian-Purnama, H.; Arsadiando, W.; Padmanaban, S. Advanced DC-DC converter topologies for solar energy harvesting applications: A review. Clean Energy 2023, 7, 555–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Singh, B.N.; Chandra, A.; Al-Haddad, K.; Pandey, A.; Kothari, D.P. A review of single-phase improved power quality AC-DC converters. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2003, 50, 962–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovalle-Flores, D.; Peña-Gallardo, R.; Palacios-Hernández, E.; Soubervielle-Montalvo, C.; Ospino-Castro, A. Holistic Analysis of the Impact of Power Generation Plants in Mexico during Their Life Cycle. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14040:2006; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Coban, K.; Ekici, S.; Karakoc, T.H. Life Cycle Assessment: A Brief Definition and Overview. In Life Cycle Assessment in Aviation; Sustainable Aviation; Karakoc, T.H., Ekici, S., Dalkiran, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geoffrey-Jalo, K.; Bennati, S.; Zanchetta, P.; Anglani, N. Investigating the Capability of a Power Converter in Delivering Net Carbon Reduction: Presentation of the First LCA Approach. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Environment and Electrical Engineering and 2023 IEEE Industrial and Commercial Power Systems Europe (EEEIC/I&CPS Europe), Madrid, Spain, 6–9 June 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission, Joint Research Centre. Global LCA Data Access (GLAD)—European Platform on Life Cycle Assessment (EPLCA). 2024. Available online: https://eplca.jrc.ec.europa.eu/globalLCA.html (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Huijbregts, M.A.; Steinmann, Z.J.; Elshout, P.M.; Stam, G.; Verones, F.; Vieira, M.; Zijp, M.; Hollander, A.; Van Zelm, R. ReCiPe2016: A harmonised life cycle impact assessment method at midpoint and endpoint level. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2017, 22, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abokersh, M.; Norouzi, M.; Boer, D.; Cabeza, L.; Casa, G.; Prieto, C.; Jimenez, L.; Valles, M. A framework for sustainable evaluation of thermal energy storage in circular economy. Renew. Energy 2021, 175, 686–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez-Cañamero, B.; Mendoza, J.M. Circular economy performance and carbon footprint of wind turbine blade waste management alternatives. Waste Manag. 2023, 164, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deviatkin, I.; Rousu, S.; Ghoreishi, M.; Nassajfar, M.; Horttanainen, M.; Leminem, V. Implementation of Circular Economy Strategies within the Electronics Sector: Insights from Finnish Companies. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagman, L.; Feiz, R. Advancing the Circular Economy Through Organic By-Product Valorization: A Multi-criteria Assessment of a Wheat-Based Biorefinery. Waste Biomass Valorization 2021, 12, 6205–6217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovalle-Flores, D.L.; Peña-Gallardo, R.; Palacios-Hernández, E.R. A Novel Circular Index for Assessing Photovoltaic and Wind Power Generation. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Autumn Meeting on Power, Electronics and Computing (ROPEC), Ixtapa, Mexico, 5–7 November 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zadeh, S.B.I.; Soltani, H.R.; Ghoneim, N.I. Revamping Seaport Operations with Renewable Energy: A Sustainable Approach to Reducing Carbon Footprint. GMSARN Int. J. 2024, 18, 315–324. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.